Abstract

Using computer vision through artificial intelligence (AI) is one of the main technological advances in dentistry. However, the existing literature on the practical application of AI for detecting cephalometric landmarks of orthodontic interest in digital images is heterogeneous, and there is no consensus regarding accuracy and precision. Thus, this review evaluated the use of artificial intelligence for detecting cephalometric landmarks in digital imaging examinations and compared it to manual annotation of landmarks. An electronic search was performed in nine databases to find studies that analyzed the detection of cephalometric landmarks in digital imaging examinations with AI and manual landmarking. Two reviewers selected the studies, extracted the data, and assessed the risk of bias using QUADAS-2. Random-effects meta-analyses determined the agreement and precision of AI compared to manual detection at a 95% confidence interval. The electronic search located 7410 studies, of which 40 were included. Only three studies presented a low risk of bias for all domains evaluated. The meta-analysis showed AI agreement rates of 79% (95% CI: 76–82%, I2 = 99%) and 90% (95% CI: 87–92%, I2 = 99%) for the thresholds of 2 and 3 mm, respectively, with a mean divergence of 2.05 (95% CI: 1.41–2.69, I2 = 10%) compared to manual landmarking. The menton cephalometric landmark showed the lowest divergence between both methods (SMD, 1.17; 95% CI, 0.82; 1.53; I2 = 0%). Based on very low certainty of evidence, the application of AI was promising for automatically detecting cephalometric landmarks, but further studies should focus on testing its strength and validity in different samples.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10278-022-00766-w.

Keywords: Artificial intelligence, Cephalometric landmarks, Dentistry, Deep Learning, Computer vision

Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) is an innovative technology that allows digital systems to learn from experience, adapt to it, and perform tasks often performed by humans [1]. The advent of AI positively impacted data and medical sciences, allowing efficient analysis of large data banks [2]. The clinical application of AI has been growing and showing promising results in diagnosis [3, 4], monitoring [5, 6], and treatment of diseases [6, 7].

The application of AI in dentistry is recent and based predominantly on computer vision techniques [1], which use automatic segmentation and analysis to manage large medical image banks for a precise and efficient diagnosis [8]. Recent studies have focused on the application of AI for studying diagnoses of caries [9], oral cancer [10], gingivitis [11], radiolucent lesions of the mandible [12], root fractures [13], and orthodontic treatment [14]. The results of these studies have suggested that AI has space for growth, with the potential to improve dental care at lower costs and for the benefit of patients [1].

Technology has been extensively recommended for orthodontic clinical practice, with digital imaging examinations, 3D scanners, and intraoral cameras, which facilitate the scanning, sharing, and storing of the data collected [14]. However, analyzing these data is still slow and time-consuming [15]. For instance, the manual cephalometric analysis performed by orthodontists requires time and professional experience. In this scenario, AI has stood out for identifying cephalometric landmarks of orthodontic interest, making this task faster and less susceptible to human error [16]. Previous studies have shown a high accuracy of AI for detecting several cephalometric landmarks, with up to 98% agreement towards manual annotation [17] and at shorter times [18, 19].

However, the existing literature on the practical application of AI for detecting cephalometric landmarks of orthodontic interest in digital images (two- or three-dimensional) is heterogeneous, with different software and programming for this purpose, and without consensus regarding accuracy and precision. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis [20] found a 79% agreement, considering a margin of error of up to 2 mm for manual detection. However, this review included one specific AI system, excluding other critical automatic detection systems.

Therefore, this systematic review of the literature evaluated studies that assessed the level of agreement between AI, regardless of system, with the human registration for annotating cephalometric landmarks in digital imaging examinations (two- or three-dimensional).

Materials and Methods

Protocol Registration

The protocol of this systematic review was produced according to the PRISMA-P (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols) guidelines [21] and registered in the PROSPERO database (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO) (CRD42021246253). The review was reported according to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) [22] guidelines and performed according to the JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis [23].

Research Question and Eligibility Criteria

The eligibility criteria of this review were based on the following research question, created according to the PIRD framework (Population, Index test, Reference test, and Diagnosis): Is artificial intelligence (I) accurate to confirm cephalometric landmarks (D) manually detected (R) in digital imaging examinations of the general population (P)?

Inclusion Criteria

Population: Two- or three-dimensional digital imaging examinations (teleradiography and computed tomography, respectively) applied to the general population, without restrictions of age and sex

Index test: Automatic detection with artificial intelligence (different available approaches such as handcrafted, deep learning, or hybrid methods) with sufficient information on software calibration and databases

Reference test: Manual/conventional detection by expert professionals

Diagnosis: Detection of any cephalometric landmark of orthodontic significance, as long as explained in the study

Study design: Diagnostic accuracy studies

There were no restrictions on language or year of publication.

Exclusion Criteria

Literature reviews, letters to the editor/editorials, personal opinions, books/book chapters, case reports/case series, pilot studies, preprint studies not yet submitted for peer-reviewing, congress abstracts, and patents

Studies with non-digital imaging examinations (conventional cephalograms)

Studies that did not compare automatic and manual landmarking

Studies with imaging examinations of post-mortem skulls and individuals with syndromes and cleft lip.

Sources of Information and Search

The electronic searches were performed until November 2021 in the Embase, IEEE Xplore, LILACS, MedLine (via PubMed), SciELO, Scopus, and Web of Science databases. OpenGrey and ProQuest were used to partially capture the “gray literature” to reduce the selection bias. The MeSH (Medical Subject Headings), DeCS (Health Sciences Descriptors), and Emtree (Embase Subject Headings) resources were used to select the search descriptors. Moreover, synonyms and free words composed the search. The Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” were used to improve the research strategy with several combinations. The search strategies in each database were made according to their respective syntax rules (Table 1). The results obtained in the primary databases were initially exported to the EndNote Web™ software (Thomson Reuters, Toronto, Canada) for cataloguing and removing duplicates. The “gray literature” results were exported to Microsoft Word (Microsoft™, Ltd, Washington, USA) for manually removing duplicates.

Table 1.

Database search strategies

| Databases | Search strategy (November 2021) |

|---|---|

| Main databases | |

|

Embase |

#1 “cephalometry”/exp OR “cephalometry” |

| #2 “artificial intelligence”/exp OR “artificial intelligence” OR “image processing”/exp OR “image processing” OR “machine learning”/exp OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning”/exp OR “deep learning” OR “artificial neural network”/exp OR “artificial neural network” OR “knowledge base”/exp OR “knowledge base” | |

| #1 AND #2 | |

|

LILACS |

#1 (MH:cephalometry OR “cephalometric landmark*” OR “cephalometric analysis” OR “cephalometric measurements”) |

| #2 (MH: “artificial intelligence” OR MH:”image processing, computer-assisted” OR MH:”machine learning” OR MH:”deep learning” OR MH:”neural networks, computer” OR “convolutional neural network” OR “neural network model” OR “connectionist model” OR MH: “knowledge bases” OR “automated localization” OR “automated detection” OR “automatic localization” OR “automatic detection”) | |

| #1 AND #2 | |

|

PubMed |

#1 Cephalometry[Mesh] OR “Cephalometric Landmark*”[tw] OR “Cephalometric Analysis”[tw] OR “Cephalometric Measurements”[tw] |

| #2 “Artificial Intelligence”[Mesh] OR “Image Processing, Computer-Assisted”[Mesh] OR “Machine Learning”[Mesh] OR “Deep Learning”[Mesh] OR “Neural Networks, Computer”[Mesh] OR “Convolutional Neural Network”[tw] OR “Neural Network Model”[tw] OR “Connectionist Model”[tw] OR “Knowledge Bases”[Mesh] OR “Automated Localization”[tw] OR “Automated Detection”[tw] OR “Automatic Localization”[tw] OR “Automatic Detection”[tw] | |

| #1 AND #2 | |

|

SciELO |

(“Artificial Intelligence” OR “Image Processing, Computer-Assisted” OR “Machine Learning” OR “Deep Learning” OR “Neural Networks, Computer” OR “Convolutional Neural Network” OR “Neural Network Model” OR “Connectionist Model” OR “Knowledge Bases” OR “Automated Localization” OR “Automated Detection” OR “Automatic Localization” OR “Automatic Detection”) |

|

Scopus |

#1 TITLE-ABS-KEY cephalometry OR “cephalometric landmark*” OR “cephalometric analysis” OR “cephalometric measurements” |

| #2 TITLE-ABS-KEY “artificial intelligence” OR “image processing, computer-assisted” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR “neural networks, computer” OR “convolutional neural network” OR “neural network model” OR “connectionist model” OR “knowledge bases” OR “automated localization” OR “automated detection” OR “automatic localization” OR “automatic detection” | |

| #1 AND #2 | |

|

Web of Science |

#1 TS = (cephalometry OR “cephalometric landmarks” OR “cephalometric landmarking” OR “cephalometric measurements”) |

| #2 TS = (“artificial intelligence” OR “image processing, computer-assited” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR “neural networks, computer” OR “convolutional neural network” OR “neural network model” OR “knowledge bases” OR “automated localization” OR “automated detection” OR “automatic localization” OR “automatic detection”) | |

| #1 AND #2 | |

|

IEEE Xplore |

#1 “ALL METADATA”: cephalometry OR “cephalometric landmarks” OR “cephalometric landmarking” OR “cephalometric analysis” OR “cephalometric measurements” |

| #2 "ALL METADATA": “artificial intelligence” OR “image processing, computer-assisted” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR “neural networks, computer” OR “convolutional neural network” OR “neural network model” OR “connectionist model” OR “knowledge bases” OR “automated localization” OR “automated detection” OR “automatic localization” OR “automatic detection” | |

| #1 AND #2 | |

| Gray literature | |

|

OpenGrey |

(cephalometry OR “cephalometric landmarks”) AND (“artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR “neural network” OR “automatic localization” OR “automatic detection”) |

|

ProQuest |

(cephalometry OR “cephalometric landmarks”) AND (“artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR “neural network” OR “automatic localization” OR “automatic detection”) |

Study Selection

After removing duplicates, the results were exported to the Rayyan QCRI software (Qatar Computing Research Institute, Doha, Qatar) to begin selecting the studies. Two reviewers (GQTB and MTCV) read the titles of the studies (first phase) and excluded those unrelated to the topic. In the second phase, the abstracts of the studies were assessed with the initial application of the eligibility criteria. The titles that met the objectives of the study but did not have abstracts available were fully analyzed in the next phase. In the third phase, the potentially eligible studies were fully read to apply the eligibility criteria. If the full texts were not found, a bibliographic request was performed to the library database (COMUT) and an e-mail was sent to the corresponding authors to obtain the texts. Full-text studies published in languages other than English or Portuguese were translated. Two reviewers independently performed all phases, and in case of doubt or disagreement, a third reviewer (LRP) was consulted to make a final decision.

Data Collection

The full texts of the eligible studies were analyzed, and the data were extracted for the following information: study identification (author, year, country, study location, and the application of ethical criteria), sample characteristics (the number of imaging examinations used for training and testing and type of imaging examination), collection and processing characteristics (software used for automatic detection, the number and name of cephalometric landmarks analyzed, the number of professionals participating in manual detection, and the number of times manual detection was performed), and main results (intra- and inter-examiner results, mean differences in millimeters between manual/conventional and automatic landmarking, and the level of agreement of AI with the human registration of landmarks). In the case of incomplete or insufficient information, the corresponding author was contacted via e-mail.

An author (GQTB) extracted all the aforementioned data, and a second reviewer (MTCV) performed a cross-examination to confirm the agreement among the data extracted. Any disagreement between the reviewers was solved with discussions with a third reviewer (LRP).

Risk of Bias Assessment

Two authors (GQTB and WAV) independently assessed the risk of individual bias in the eligible studies with QUADAS-2 [24]. This tool includes four domains: patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow and timing. Each domain is evaluated for the risk of bias, and the first three domains are also evaluated for applicability concerns. Each domain can be classified as a “high risk,” “uncertain risk,” and “low risk.” The evaluators solved their divergences with a discussion, and when there was no consensus, a third author (LRP) was consulted to make a final decision.

Data Synthesis

The meta-analysis was performed with the R software, version 4.2.0, for Windows (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), aided by the meta and metafor packages. For inclusion in the meta-analysis, the studies should present one of the following outcomes: (1) the proportion of cephalometric landmarks correctly identified with AI within the thresholds of 2 or 3 mm (agreement) and (2) the mean divergence between cephalometric landmarking with AI and manual landmarking, in millimeters.

For the first outcome, individual studies were combined in the meta-analysis with the random-effects model by Dersimonian-Laird, logit transformation, and the inverse variance method, and the results were described in percentage (%) of agreement. For the second outcome, considering that the studies used different methods and formulas to determine the mean divergence between AI and manual landmarking, the present review used the standardized mean difference (SMD) as an effect measure, with a respective 95% confidence interval, using the inverse variance method. For this outcome, the closer to 0 the SMD, the more precise the automatic identification of the cephalometric landmark. Whenever possible, the individual results of each dataset were considered for studies using more than one dataset in their samples. The weights of each study in the meta-analytical analyses were calculated considering the total number of imaging examinations and cephalometric landmarks analyzed in each study. The heterogeneity among studies was assessed with tau-squared statistic (t^2) and I2 and classified as low (I2 < 50%), moderate (I2 = 50% to 75%), and high (I2 > 75%).

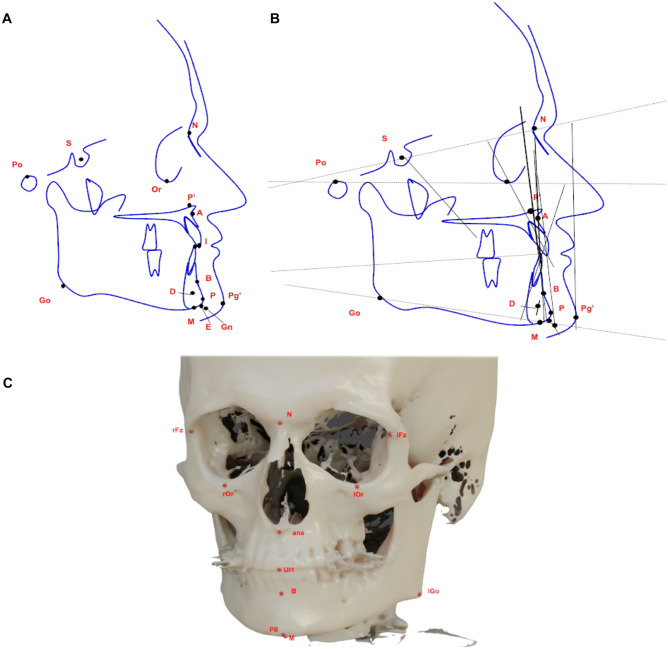

The mean divergence between AI and manual detection of cephalometric landmarks was also individually investigated. For this analysis, the cephalometric landmarks were selected based on those used in the IEEE 2015 ISBI Grand Challenge #1: Automated Detection and Analysis for Diagnosis in Cephalometric X-ray Image [25]. Figure 1 shows an example of landmarks placement in 2D cephalometric schematic representation (Fig. 1A), how it serves as a reference for many angular and linear analyses for diagnosis purposes (Fig. 1B), and those landmarks in a 3D analysis (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representations of 2D and 3D cephalometric analysis. A Examples of landmark placement; B linear and angular measurements based on the most common landmarks; C representation of 3D landmark placement

The subgroups were analyzed considering the image (2D vs. 3D) and AI system (handcrafted vs. deep learning) used in the assessment. The publication bias was evaluated with a visual inspection of funnel plot asymmetry and the Egger test.

Assessment of the Certainty of Evidence

The certainty of evidence was assessed with the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) tool. The GRADEpro GDT software (http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org) summarized the results. The assessment was based on study design, risk of bias, inconsistency, indirect evidence, imprecision, and publication bias. The certainty of evidence can be classified as high, moderate, low, or very low [26].

Results

Study Selection

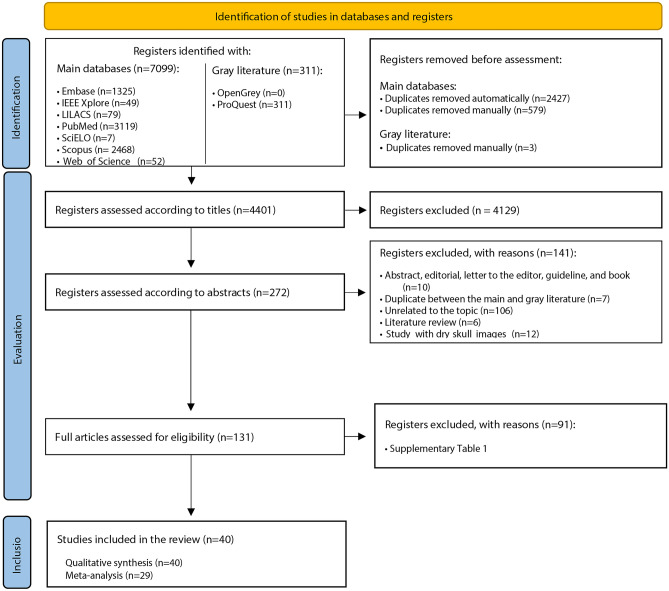

In the first phase of study selection, 7410 results were found distributed in nine electronic databases, including the “gray literature.” After removing duplicates, 4401 results remained for analysis. A careful reading of the titles excluded 4129 results. Two hundred seventy-two studies remained for the reading of abstracts. Of these, 141 studies were excluded after applying the eligibility criteria. The 131 remaining results were fully read, of which 91 were excluded (Supplementary Table 1). Forty studies [17–19, 27–63] were included in the qualitative analysis. Figure 2 presents the details of the search, identification, inclusion, and exclusion of studies.

Fig. 2.

Flowchart of the search, identification, and selection of eligible studies

Characteristics of Eligible Studies

The studies were published between 2005 and 2021 and performed in 12 different countries, with 26 studies in Asia [17–19, 30–35, 39, 43–49, 51, 52, 54, 55, 57, 59, 60, 62, 63], nine in Europe [27–29, 36, 40, 50, 56, 58, 61], and five in America [37, 38, 41, 42, 53]. The total sample included 12,601 imaging examinations, with 11,029 digital teleradiographs and 1572 cone beam computed tomographs (CBCTs).

The studies used different methods for automatically detecting cephalometric landmarks, highlighting those related to the big groups of AI: handcrafted and deep learning. The imaging examinations of the included studies detected several landmarks, ranging from 10 [28, 29] to 93 [59] cephalometric landmarks per study. The following landmarks were the most used for detection: nasion (90.7% of studies), gonion (88.4%), pogonion (86.0%), menton (83.7%), orbitale (81.4%), sella (76.7%), anterior nasal spine (72.1%), gnathion (72.1%), porion (69.8%), posterior nasal spine (67.4%), upper incisal incision (53.5%), articulare (48.8%), lower incisal incision (46.5%), supramentale (46.5%), upper lip (46.5%), lower lip (46.5%), subspinale (44.2%), soft tissue pogonion (39.5%), and subnasale (39.5%). Table 2 details the main information of each eligible study.

Table 2.

Main characteristics of the eligible studies

| Authors, year (country) | Imaging examination | Mean age ± SD (age group) | Number of training/testing radiographs | Source of radiographs | Cephalometric landmarks detected | Number of experts involved in manual landmarking | Intra- and inter-examiner test | Specific artificial intelligence method used | General classification of the artificial intelligence used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Giordano et al., 2005 (Italy) |

Cephalograms | nr | 97/26 | nr | 8 | 2 (orthodontists) | nr | Cellular neural networks | Handcrafted |

|

Leonardi et al., 2009 (Italy) |

Cephalograms |

14.8 ± nr (10–17) |

nr/41 | Orthodontic Department of Policlinico, University Hospital of Catania, Italy | 10 | 5 (orthodontists) | Intra and inter | Cellular neural networks | Handcrafted |

|

Vucinic et al., 2010 (Serbia) |

Cephalograms |

14.7 ± nr (7.2–25.6) |

Modified leave-one-out/60 | Orthodontic Department of the Dental Clinic, University of Novi Sad, Serbia | 17 | 1 | Intra | Active appearance models | Handcrafted |

|

Tam and Lee, 2012 (Japan) |

Cephalograms | nr | 1/20 | Dental clinic | 20 | 2 | nr | Two-stage rectified point translation transform | Handcrafted |

|

Shahidi et al., 2013 (Iran) |

Cephalograms | nr | nr/40 | Private oral and craniofacial radiology center | 16 | 3 (orthodontists) | Intra and inter | Template-matching method or edge detection technique | Handcrafted |

|

Shahidi et al., 2014 (Iran) |

Cone Beam Computed tomography |

nr (10–43) |

8/20 | Oral and maxillofacial radiology center in Shiraz | 14 | 3 (2 orthodontists and 1 radiologist) | Intra and inter | Combined approach: feature-based and voxel similarity-based | Handcrafted |

|

Gupta et al., 2015 (India) |

Cone Beam Computed tomography | nr | nr/30 | Postgraduate Orthodontic Clinic of All India Institute of Medical Sciences | 20 | 3 (orthodontists) | Intra and inter | Knowledge-based algorithm with extraction through a VOI | Handcrafted |

|

Tam and Lee, 2015 (Japan) |

Cephalograms | nr | 0/80 | nr | 20 | 2 | nr | Two-stage rectified point transform | Handcrafted |

|

Vasamsetti et al., 2015 (India) |

Cephalograms | nr | 9/37 | Center for Dental Education and Research of All India Institute of Medical Sciences, India | 24 | 3 (orthodontists) | nr | Optimized template matching algorithm | Handcrafted |

|

Codari et al., 2016 (Italy) |

Cone Beam Computed tomography |

nr (37–74) |

nr/18 | SST Dentofacial Clinic, Italy | 21 | 3 (radiologists) | Intra and inter | Adaptive cluster-based segmentation followed by an intensity-based registration | Handcrafted |

|

Lindner et al., 2016 (Japan) |

Cephalograms |

27 ± nr (7–76) |

150/400 | nr | 19 | 2 (orthodontists) | Intra and inter | Fully automatic landmarking annotation system | Handcrafted |

|

Zhang et al., 2016 (United States) |

Cone Beam Computed tomography | nr | 30/41 | nr | 15 | nr | Intra and inter | Segmentation-guided partially-joint regression forest model | Handcrafted |

|

Arik et al., 2017 (United States) |

Cephalograms | nr | 450/750 | IEEE ISBI 2014 and 2015 dataset | 19 | 2 (orthodontists) | Intra and inter | Convolutional neural networks | Deep learning |

|

Lee et al., 2017 (South Korea) |

Cephalograms | nr | 150/150 | IEEE ISBI 2015 dataset | 19 | 2 (orthodontists) | nr | End-to-end deep learning system based on convolutional neural networks | Deep learning |

|

De Jong et al., 2018 (Netherlands) |

Cone Beam Computed tomography |

nr (16–54) |

Leave-one-out/39 | Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Department at Erasmus, Netherlands | 33 | 3 | Intra and inter | 2D Gabor wavelets and ensemble learning | Handcrafted |

|

Montufar et al., 2018a (Mexico) |

Cone Beam Computed tomography | nr | Leave-one-out/24 | Public dataset of virtual skeleton database from the Swiss Institute | 18 | 2 | Intra | Active shape models | Handcrafted |

|

Montufar et al., 2018b (Mexico) |

Cone Beam Computed tomography | nr | Leave-one-out/24 | Public dataset of virtual skeleton database from the Swiss Institute | 18 | 2 | Intra | Hybrid approach with active shape models | Handcrafted |

|

Neelapu et al., 2018 (India) |

Cone Beam Computed tomography | nr | nr/30 | Postgraduate orthodontic clinic database | 20 | 3 (orthodontists) | Intra and inter | Algorithm based on boundary definition of the human anatomy | Handcrafted |

|

Wang et al., 2018 (China) |

Cephalograms |

nr (6–60) |

150/315 | IEEE ISBI 2015 Challenge dataset and database of Peking University | 19 or 45 | 2 (orthodontists) | Intra and inter | Multiresolution decision tree regression voting | Handcrafted |

|

Chen et al., 2019 (China) |

Cephalograms | nr | 150/250 | IEEE ISBI 2015 dataset | 19 | 2 (orthodontists) | nr | Attentive feature pyramid fusion and regression-voting | Handcrafted |

|

Dai et al., 2019 (China) |

Cephalograms | nr | 100/200 | Dataset of the Automatic Cephalometric X-Ray Landmark Detection Challenge | 19 | 2 | nr | Adversarial encoder-decoder networks | Deep learning |

|

Kang et al., 2019 (South Korea) |

Cone Beam Computed tomography | 24.22 ± 2.91 | 18/9 | Data from a previous study | 12 | 2 (radiologists) | Intra and inter | Three-dimensional convolutional neural networks | Deep learning |

|

Lee et al., 2019 (South Korea) |

Cone Beam Computed tomography | 24.22 ± 2.91 | 20/7 | Data from a previous study | 7 | 2 (radiologists) | nr | Deep learning | Deep learning |

|

Nishimoto et al., 2019 (Japan) |

Cephalograms | nr | 153/66 | Gathered via the Internet with Image Spider | 10 | nr | nr | Convolutional neural network with convolutional and dense layers | Deep learning |

|

Payer et al., 2019 (Austria) |

Cephalograms | nr | 150/250 | IEEE ISBI 2015 dataset | 19 | 2 (orthodontists) | nr | Convolutional neural network based on spatial configuration-net | Deep learning |

|

Kim et al., 2020 (South Korea) |

Cephalograms | nr | 1675/400 | Own dataset of two medical institutes | 19 or 23 | 2 (orthodontists) | nr | Stacked hourglass deep learning model | Deep learning |

|

Lee et al., 2020 (South Korea) |

Cephalograms | nr | 150/250 | IEEE ISBI 2015 dataset | 19 | 2 (orthodontists) | Intra and inter | Bayesian convolutional neural networks | Deep learning |

|

Li et al., 2020 (United States) |

Cephalograms | nr | 150/250 | IEEE ISBI 2015 dataset | 19 | 2 (orthodontists) | nr | Global-to-local cascaded graph convolutional networks based on deep adaptive graph | Deep learning |

|

Ma et al., 2020 (Japan) |

Cone Beam Computed tomography | nr | 58/8 |

Database of the University of Tokyo Hospital |

13 | 1 (orthodontist) | nr | Patch-based deep neural networks with a three-layer convolutional neural network | Deep learning |

|

Moon et al., 2020 (South Korea) |

Cephalograms | nr | 2200/200 |

PACS server at Seoul National University Dental Hospital |

19, 40, or 80 | 1 (orthodontist) | Intra and inter | Deep learning system: modified you-only look-once | Deep learning |

|

Noothout et al., 2020 (Netherlands) |

Cephalograms | nr | 150/250 | IEEE ISBI 2015 dataset | 19 | 2 (orthodontists) | Intra and inter | Fully convolutional neural network | Deep learning |

|

Oh et al., 2020 (South Korea) |

Cephalograms | nr | 150/250 | IEEE ISBI 2015 dataset | 19 | 2 | Inter | Local feature perturbator with anatomical configuration loss | Deep learning |

|

Qian et al., 2020 (China) |

Cephalograms | nr | 150/250 | IEEE ISBI 2015 dataset | 19 | 2 (orthodontists) | Intra and inter | Multi-Head Attention Neural Network with multi-head and attention part | Handcrafted |

|

Song et al., 2020 (Japan) |

Cephalograms | nr | 150/350 | IEEE ISBI 2015 dataset and own dataset | 19 | 2 (orthodontists) | nr | Convolutional Neural Network based on extracted ROI patches | Deep learning |

|

Wirtz et al., 2020 (Germany) |

Cephalograms | nr | 150/250 | IEEE ISBI 2015 dataset | 19 | 2 (orthodontists) | nr | Coupled Shape Model refined with a Hough Forest | Handcrafted |

|

Yun et al., 2020 (South Korea) |

Cone Beam Computed tomography | 24.22 ± 2.91 | 230/25 | Data from a previous study | 93 | 1 | nr |

Convolutional Neural Network with Variational Autoencoder |

Deep learning |

|

Zeng et al., 2020 (China) |

Cephalograms | nr | 150/250 | IEEE ISBI 2015 dataset | 19 | 2 (orthodontists) | nr | Cascaded Convolutional Neural Network | Deep learning |

|

Huang et al., 2021 (Germany) |

Cephalograms | nr | 150/250 | IEEE ISBI 2015 dataset | 19 | nr | nr | Fully automated deep learning method combining LeNet-5 and ResNet50 | Deep learning |

|

Kim et al., 2021 (South Korea) |

Cone Beam Computed tomography | nr | 345/85 | PACS database at Kyung Hee University Dental Hospital | 15 | 1 (orthodontist) | Intra | Multistage Convolutional Neural Network | Deep learning |

|

Kwon et al., 2021 (South Korea) |

Cephalograms | nr | 150/100 | IEEE ISBI 2015 dataset | 19 | 2 (orthodontists) | nr | Multistage Convolutional Neural Network with Probabilistic Approach | Deep learning |

SD standard deviation (years), nr not reported in the study

Risk of Individual Bias in the Studies

Table 3 presents detailed information on the risk of bias in the eligible studies. Only three studies [31, 32, 40] presented a low risk of bias for all domains evaluated with QUADAS-2. Most studies presented a high risk of bias for the domains of patient selection (80%—32/40) and reference test (65%—26/40). Regarding the applicability assessment, the results were similar to those of the risk of bias assessment.

Table 3.

Risk of bias assessed with QUADAS-2

| Author, year | Risk of bias | Applicability | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient selection | Index test | Reference test | Flow and timing | Patient selection | Index test | Reference test | |

| Giordano et al., 2005 | H | L | H | H | H | L | H |

| Leonardi et al., 2009 | U | L | U | L | L | L | U |

| Vucinic et al., 2010 | U | L | U | L | U | L | U |

| Tam and Lee, 2012 | H | U | H | L | H | U | H |

| Shahidi et al., 2013 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Shahidi et al., 2014 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Gupta et al., 2015 | H | L | L | L | H | L | L |

| Tam and Lee, 2015 | H | U | H | L | H | L | H |

| Vasamsetti et al., 2015 | H | L | U | L | H | L | U |

| Codari et al., 2016 | H | L | U | L | H | L | U |

| Lindner et al., 2016 | H | L | H | L | H | L | H |

| Zhang et al., 2016 | H | L | H | L | H | L | H |

| Arik et al., 2017 | H | L | H | L | H | L | H |

| Lee et al., 2017 | H | L | H | L | H | L | H |

| De Jong et al., 2018 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Montufar et al., 2018a | H | L | L | L | H | L | L |

| Montufar et al., 2018b | H | L | L | L | H | L | L |

| Neelapu et al., 2018 | H | L | L | L | H | L | L |

| Wang et al., 2018 | H | L | H | L | L | L | L |

| Chen et al., 2019 | H | L | H | L | H | L | H |

| Dai et al., 2019 | H | L | H | L | H | L | H |

| Kang et al., 2019 | L | L | U | L | L | L | U |

| Nishimoto et al., 2019 | H | L | H | L | H | L | H |

| Payer et al., 2019 | H | L | H | L | H | L | H |

| Lee et al., 2019 | H | H | H | L | H | H | H |

| Kim et al., 2020 | H | L | U | L | H | L | U |

| Lee et al., 2020 | H | L | H | L | H | L | H |

| Li et al., 2020 | H | L | H | L | H | L | H |

| Ma et al., 2020 | H | H | H | L | H | H | H |

| Moon et al., 2020 | U | L | U | L | U | L | U |

| Noothout et al., 2020 | H | L | H | L | H | L | H |

| Oh et al., 2020 | H | L | H | L | H | L | H |

| Qian et al., 2020 | H | L | H | L | H | L | H |

| Song et al., 2020 | H | L | H | L | H | L | H |

| Wirtz et al., 2020 | H | L | H | L | H | L | H |

| Yun et al., 2020 | H | H | H | L | H | H | H |

| Zeng et al., 2020 | H | L | H | L | H | L | H |

| Huang et al., 2021 | H | H | H | H | H | H | H |

| Kim et al., 2021 | U | L | H | L | U | L | H |

| Kwon et al., 2021 | H | L | H | L | H | L | H |

H high risk, U unclear risk, L low risk

Specific Results of the Eligible Studies

The overall mean distance (mean error) between automatic detection and manual landmarking ranged between 1.03 ± 1.29 [62] and 2.59 ± 3.45 mm [31] in two-dimensional imaging examinations (teleradiographs) and between 1.88 ± 1.10 mm [43] and 7.61 ± 3.61 mm [47] in three-dimensional imaging examinations (computed tomographs). The lower the mean error, the better the precision of the method used for automatic detection.

The overall agreement rate of the automatic detection for a margin of error up to 2 mm (clinically acceptable) ranged between 43.75 [31] and 88.49% [53] for two-dimensional imaging examinations. For three-dimensional imaging examinations, the variation was between 64.16% [43] and 87.13% [62]. The higher the agreement rate within the margin of error up to 2 mm, the better the performance of the method used for automatic detection. Supplementary Table 2 presents the quantitative results and the main outcomes of the eligible studies.

Synthesis of Results and Meta-analysis

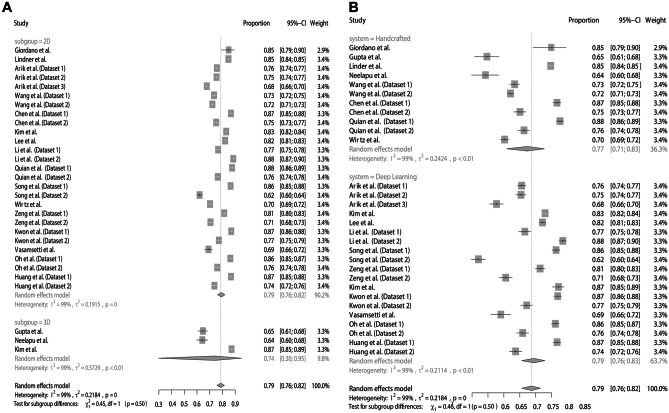

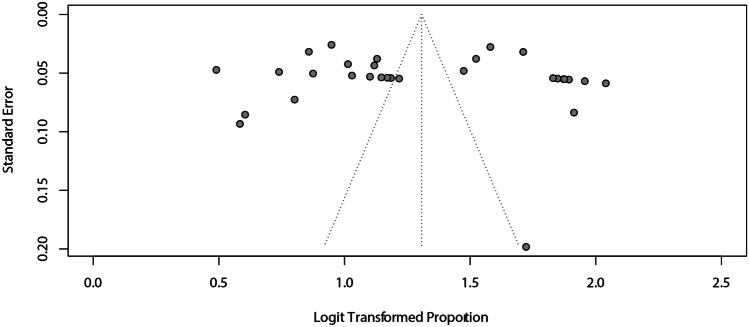

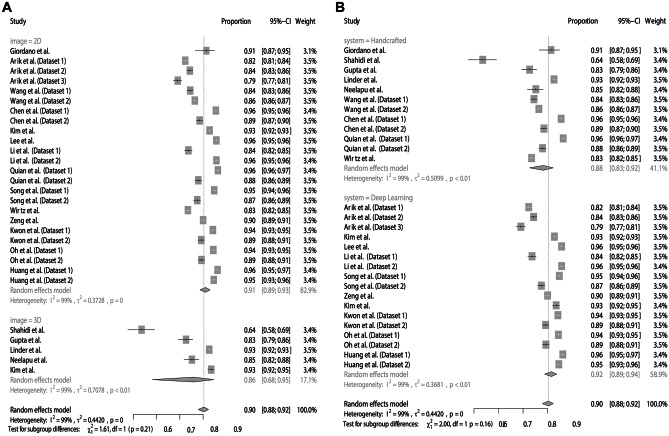

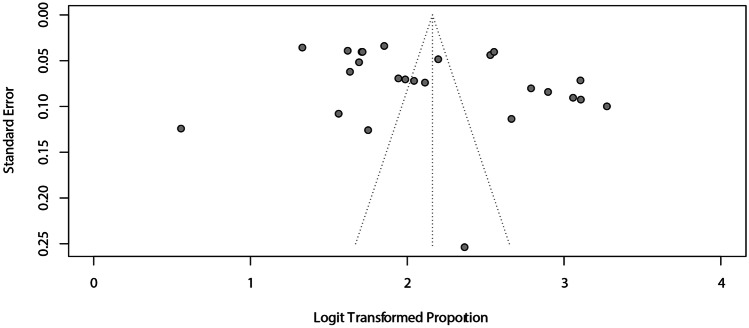

For assessing the agreement between AI and manual detection considering a margin of error of 2 mm, the meta-analysis obtained a summarized effect of 79% (95% CI: 76–82%) with high heterogeneity (I2 = 99%). The subgroup analyses showed similar proportions between the digital images (2D = 79%; 95% CI 76–82% vs. 3D = 74%; 95% CI 30–95%) (Fig. 3A) and AI systems (handcrafted = 77%; 95% CI 71–83% vs. deep learning = 79%; 95% CI 76–83%) (Fig. 3B). There was no asymmetry in the funnel plot (Fig. 4), which was confirmed with the Egger test (p = 0.6187).

Fig. 3.

Agreement of AI and manual landmarking considering a margin of error of 2 mm. A Subgroup analysis according to images. B Subgroup analysis according to AI

Fig. 4.

Assessment of the risk of publication bias for the agreement of AI and manual landmarking, considering a margin of error of 2 mm

Considering a margin of error of 3 mm, agreement was 90% (95% CI: 88–92%) with high heterogeneity (I2 = 99%). The subgroup analyses for this outcome also showed similar accuracy between the images (Fig. 5A) and AI systems (Fig. 5B). The analysis of funnel plot asymmetry (Fig. 6) and the Egger test (p = 0.0718) did not detect a publication bias.

Fig. 5.

Agreement of AI and manual landmarking considering a margin of error of 3 mm. A Subgroup analysis according to images. B Subgroup analysis according to AI

Fig. 6.

Assessment of the risk of publication bias for the agreement of AI and manual landmarking, considering a margin of error of 3 mm

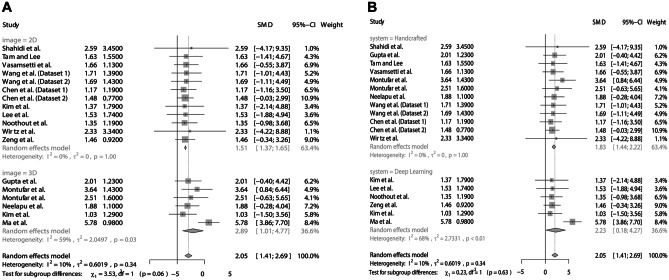

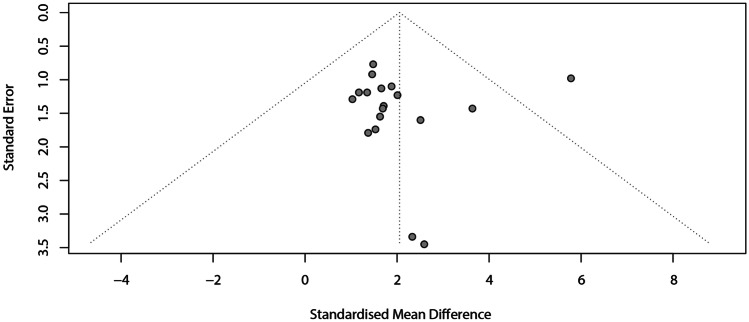

The meta-analysis to verify the divergence of the position between cephalometric landmarking with AI and manual landmarking showed an SMD of 2.05 (95% CI: 1.41–2.69) with low heterogeneity (I2 = 10%). The subgroup analyses showed similar divergences between the digital images (2D = 1.51; 95% CI 1.37–1.65 vs. 3D = 2.89; 95% CI 1.01–4.77) (Fig. 7A) and AI systems (handcrafted = 1.83; 95% CI 1.44–2.22 vs. deep learning = 2.23; 95% CI 0.18–4.27) (Fig. 7B). The analysis of funnel plot asymmetry (Fig. 8) and the Egger test (p = 0.8883) did not detect a publication bias.

Fig. 7.

Divergence of the position between cephalometric landmarking with AI and manual landmarking. (A) Subgroup analysis according to images. (B) Subgroup analysis according to AI

Fig. 8.

Assessment of the risk of publication bias for the divergence analysis between AI and manual landmarking

This study also investigated the divergence between cephalometric landmarking with AI and manual landmarking for each cephalometric landmark. Hence, the landmarks with the lowest divergences were menton (SMD, 1.17; 95% CI, 0.82; 1.53), subnasale (SMD, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.69; 1.46), and gnathion (SMD, 1.27; 95% CI, 0.95; 1.58). The subgroup analyses showed that 2D images were more precise in identifying the sella, supramentale, gnathion, lower incisal incision, and posterior nasal spine landmarks. Considering the AI systems, deep learning was more precise in identifying nine of the 19 landmarks analyzed (Table 4).

Table 4.

Meta-analysis results of the individual precision of cephalometric landmarks, based on the ISBI 2015 challenge

| Cephalometric landmark | # of studies | Overall summary mean (95% CI) | Overall I2 test | Subgroup summary mean (95% CI)—type of image | I2 subgroups | Subgroup difference test | Subgroup summary mean (95% CI)—type of AI | I2 subgroups | Subgroup difference test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sella | 11 | 1.55 (1.02; 2.08) | 0% | 2D, 1.13 (0.93; 1.32) | 0% | p < 0.01 | Handcrafted: 1.92 (1.26; 2.57) | 0% | p < 0.01 |

| 3D, 2.69 (1.48; 3.90) | 0% | Deep learning: 0.92 (0.72; 1.12) | 0% | ||||||

| Nasion | 17 | 1.44 (1.10; 1.79) | 0% | 2D, 1.43 (1.08; 1.78) | 0% | p = 0.94 | Handcrafted: 1.56 (1.12; 1.99) | 0% | p = 0.22 |

| 3D, 1.45 (0.80; 2.10) | 0% | Deep learning: 1.14 (0.36; 1.91) | 0% | ||||||

| Orbitale | 14 | 2.12 (1.61; 2.62) | 0% | 2D, 1.94 (1.43; 2.45) | 0% | p = 0.32 | Handcrafted: 2.63 (2.04; 3.22) | 0% | p = 0.03 |

| 3D, 2.44 (1.37; 3.51) | 0% | Deep learning: 1.63 (0.49; 2.77) | 0% | ||||||

| Porion | 13 | 1.76 (1.01; 2.50) | 20% | 2D, 1.22 (0.64; 1.80) | 0% | p = 0.04 | Handcrafted: 1.94 (0.36; 3.53) | 33% | p = 0.99 |

| 3D, 2.98 (1.08; 4.88) | 42% | Deep learning: 1.95 (0.93; 2.97) | 4% | ||||||

| Subspinale | 12 | 1.96 (1.55; 2.37) | 0% | 2D, 1.66 (1.31; 2.00) | 0% | p = 0.10 | Handcrafted: 2.25 (1.73; 2.76) | 0% | p < 0.01 |

| 3D, 2.32 (1.15; 3.50) | 0% | Deep learning: 1.45 (1.00; 1.89) | 0% | ||||||

| Supramentale | 14 | 2.11 (1.69; 2.53) | 0% | 2D, 1.63 (1.18; 2.08) | 0% | p = 0.03 | Handcrafted: 2.28 (1.79; 2.77) | 0% | p = 0.08 |

| 3D, 2.38 (1.66; 3.10) | 97% | Deep learning: 1.57 (0.45; 2.68) | 0% | ||||||

| Pogonion | 11 | 1.47 (0.98; 1.96) | 0% | 2D, 1.26 (1.10; 1.43) | 0% | p = 0.21 | Handcrafted: 1.93 (1.34; 2.53) | 0% | p < 0.01 |

| 3D, 1.87 (0.56; 3.18) | 0% | Deep learning: 0.91 (0.34; 1.48) | 0% | ||||||

| Menton | 13 | 1.17 (0.82; 1.53) | 0% | 2D, 0.95 (0.82; 1.09) | 0% | p = 0.17 | Handcrafted: 1.31 (0.88; 1.73) | 0% | p = 0.23 |

| 3D, 1.43 (0.59; 2.28) | 23% | Deep learning: 0.86 (-0.04; 1.76) | 0% | ||||||

| Gnathion | 11 | 1.27 (0.95; 1.58) | 0% | 2D, 0.98 (0.80; 1.15) | 0% | p < 0.01 | Handcrafted: 1.43 (1.03; 1.82) | 0% | p < 0.01 |

| 3D, 1.85 (1.32; 2.39) | 0% | Deep learning: 0.92 (0.62; 1.22) | 0% | ||||||

| Gonion | 13 | 2.42 (2.04; 2.79) | 0% | 2D, 2.12 (1.44; 2.79) | 0% | p = 0.17 | Handcrafted: 2.63 (2.20; 3.07) | 0% | p < 0.01 |

| 3D, 2.60 (2.11; 3.10) | 0% | Deep learning: 1.82 (1.43; 2.22) | 0% | ||||||

| Lower incisal incision | 10 | 1.92 (1.23; 2.60) | 20% | 2D, 1.20 (0.94; 1.46) | 0% | p < 0.01 | Handcrafted: 2.50 (1.68; 3.32) | 0% | p < 0.01 |

| 3D, 2.66 (1.22; 4.11) | 34% | Deep learning: 0.99 (0.62; 1.36) | 0% | ||||||

| Upper incisal incision | 13 | 1.32 (0.94; 1.71) | 0% | 2D, 1.01 (0.80; 1.23) | 0% | p = 0.11 | Handcrafted: 1.76 (1.26; 2.25) | 0% | p < 0.01 |

| 3D, 1.79 (0.84; 2.74) | 0% | Deep learning: 0.90 (0.69; 1.12) | 0% | ||||||

| Upper Lip | 6 | 1.69 (1.00; 2.37) | 0% | N/A | N/A | N/A | Handcrafted: 1.23 (0.62; 1.84) | 0% | p = 0.14 |

| Deep learning: 1.99 (-0.10; 4.09) | 10% | ||||||||

| Lower Lip | 6 | 1.47 (0.95; 1.99) | 0% | N/A | N/A | N/A | Handcrafted: 1.24 (0.47; 2.00) | 0% | p = 0.34 |

| Deep learning: 1.66 (0.08; 3.24) | 0% | ||||||||

| Subnasale | 5 | 1.07 (0.69; 1.46) | 0% | N/A | N/A | N/A | Handcrafted: 1.51 (-0.15; 3.18) | 0% | p = 0.16 |

| Deep learning: 0.96 (0.71; 1.22) | 0% | ||||||||

| Soft tissue pogonion | 5 | 2.07 (1.05; 3.10) | 100% | N/A | N/A | N/A | Handcrafted: 1.81 (1.22; 2.40) | 0% | p = 0.39 |

| Deep learning: 2.60 (-1.30; 6.51) | 22% | ||||||||

| Posterior nasal spine | 11 | 1.44 (0.99; 1.89) | 0% | 2D, 1.10 (0.85; 1.36) | 0% | p < 0.01 | Handcrafted: 1.91 (1.35; 2.47) | 0% | p < 0.01 |

| 3D, 2.32 (1.45; 3.19) | 0% | Deep learning: 0.98 (0.58; 1.39) | 0% | ||||||

| Anterior nasal spine | 11 | 1.53 (1.01; 2.05) | 0% | 2D, 1.62 (1.05; 2.20) | 0% | p = 0.86 | Handcrafted: 1.82 (1.00; 2.63) | 0% | p = 0.10 |

| 3D, 1.54 (0.27; 2.81) | 33% | Deep learning: 1.16 (0.54; 2.05) | 0% | ||||||

| Articulare | 5 | 1.51 (1.11; 1.90) | 0% | N/A | N/A | N/A | Handcrafted: 1.48 (-0.02; 2.97) | 0% | p = 0.90 |

| Deep learning: 1.52 (0.92; 2.13) | 0% |

Certainty of Evidence

The certainty of evidence of the three outcomes (accuracy for the margin of error of 2 and 3 mm and divergence of the position between cephalometric landmarking with AI and manual landmarking) was classified as very low (Table 5).

Table 5.

Summary of finding (SoF) for the proportion of cephalometric landmarks correctly identified with AI, and the mean divergence from manual landmarking

| Certainty assessment | Certainty | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirect Evidence | Imprecision | Other considerations | Relative effect (95% CI) | ||

| Agreement between cephalometric landmarking with AI and manual landmarking (Threshold 2 mm) | |||||||||

| 19 | Diagnostic accuracy studies | Very seriousa | Seriousb | Not serious | Not serious | Publication bias not detected | Proportion: 0.79 (0.76;0.82) |

⨁◯◯◯ Very Low |

|

| Agreement between cephalometric landmarking with AI and manual landmarking (Threshold 3 mm) | |||||||||

| 19 | Diagnostic accuracy studies | Very seriousa | Seriousb | Not serious | Not serious | Publication bias not detected | Proportion: 0.90 (0.88;0.92) |

⨁◯◯◯ Very Low |

|

| Divergence between cephalometric landmarking with AI and manual landmarking | |||||||||

| 15 | Diagnostic accuracy studies | Very seriousa | Not serious | Not serious | Seriousc | Publication bias not detected | SMD: 2.05 (1.41;2.69) |

⨁◯◯◯ Very Low |

|

Evidence levels of the GRADE workgroup

High certainty: strongly confident the true effect is close to the effect estimate

Moderate certainty: moderately confident in the effect estimate. The true effect might be close to the effect estimate, but it might be substantially different

Low certainty: limited confidence in the effect estimate. The true effect might substantially differ from the effect estimate

Very low certainty: little confidence in the effect estimate. The true effect will probably substantially differ from the effect estimate

CI confidence interval, SMD standardized mean difference

aHigh risk of bias in majority of the included studies—downgraded by two levels

bHigh and unexplained heterogeneity (I2 > 75%)—downgraded by one level

cLarge confidence interval—downgraded by one level

Discussion

This systematic review with meta-analysis aimed to evaluate the use of artificial intelligence (AI) for detecting cephalometric landmarks in digital imaging examinations and compare it to manual landmarking. The results showed that the agreement between AI and manual detection ranged from 79 to 90% according to the margin of error, and the mean divergence was 2.05 compared to manual landmarking.

Using AI to identify cephalometric landmarks is a great innovation in clinical practice. The development of reliable and automated tools to detect and perform cephalometric analysis have great repercussion for the clinician as it speeds, standardizes, and enhance the process. The studies included in this systematic review showed that AI can perform an automatic identification in under one minute, which would make this step more practical for dentists and allow faster orthodontic planning. Another advantage of AI reported in the eligible studies is that because it is an automated tool, the identification of cephalometric landmarks would not be susceptible to human error. Those findings may influence the decision to transition from traditional methods to upcoming technologies, such as the ones reported.

The meta-analysis results showed that the agreement rates between AI and manual detection in identifying cephalometric landmarks were 79% and 90%, considering the margins of error of 2 and 3 mm, respectively, with a mean divergence of 2.05. These data may be promising, as some studies affirm that even when two experts perform manual landmarking, there may be divergences over 1 mm [18, 64, 65]. The data of the present review are similar to those of another previous meta-analysis, which found 80% agreement and a divergence of 0.05 for a margin of error of 2 mm. Different from the review by Schwendicke et al., this new review included all types of AI presented in the literature, aiming to extend the evidence. Moreover, only studies using digital imaging examinations were included because these images have extensive clinical use. Even with the differences indicated, the application of AI shows good accuracy for cephalometric landmarking. However, when considering a margin of error of 2 mm clinically acceptable [52, 58], AI has space for improvement because the higher the margin of error, the better the results.

The individual analysis of cephalometric landmarks showed a high variety of mean divergences between AI and manual detection of each landmark. For instance, the results of the meta-analysis showed that the subnasale landmark had a lower divergence, while the gonion landmark had a divergence higher than 2 mm. This result may be justified by the inherent challenge of cephalometric landmarking either with AI or manually [65, 66]. Previous studies showed potentially significant variations among experienced examiners when identifying some landmarks [18, 67]. These results are explained by the difficult visualization of these landmarks due to their anatomical position, which may depend on the head position at the time of examination, changes due to the radiography device, and quality and overlap of structures in imaging examinations [52]. Moreover, landmarks located in bone margins may represent a challenge for AI identification [18]. In this context, considering that the evaluation of cephalometric landmarks does not have a definite gold standard and depends on manual assessments, these errors and difficulties may be transferred to the interpretations of results presented by AI. This may be characterized as one of the significant limitations of the current evidence on the accuracy of AI in identifying cephalometric landmarks [18].

Cephalometry is the reference examination in orthodontics, mostly used to diagnose facial skeletal morphology, predict growth, and plan and assess orthodontic treatment results [68]. However, this assessment uses two-dimensional images of a three-dimensional structure, causing errors in the projection and identification of structures [68]. To overcome these limitations, studies have proposed the transition from cephalometric analysis in 2D images to 3D images, using cone-beam computed tomography [53]. The advantages of using 3D images for this task include the precise identification of anatomical structures, prevention of geometric distortion of the image, and the ability to evaluate complex facial structures [69]. Considering these practical differences, this meta-analysis performed subgroup analyses to assess the influence of the type of image on the accuracy of AI. The results showed that using 2D images resulted in a lower divergence between AI and manual identifications for specific landmarks (sella, supramentale, gnathion, lower incisal incision, and posterior nasal spine). However, the overall assessment of the results showed similar accuracy levels of AI landmark placement in 2D or 3D images. However, these results may be justified by the fact that 3D images were used in in a reduced number of samples, making the results for this subgroup imprecise. It is also important to highlight that these subgroup analyses are only exploratory, and their results should be interpreted with caution.

Another subgroup analysis performed in this meta-analysis was the comparison between the types of AI used in the studies. Among the algorithms used in computer vision techniques, handcrafted systems use specific techniques to extract different characteristics from the images, such as texture, color, and object margins, to later compose the feature vector, which is used by different machine-learning algorithms. In turn, deep learning systems are considered the most recent AI technology and use an artificial neural network with several layers of depth that learn characteristics directly from observing input images, using a pyramid approach [70]. The present study did not find differences in both subgroups for overall accuracy or mean divergence between AI and manual detections, but deep learning provided lower divergences in nine of the 19 landmarks analyzed. Deep-learning algorithms are more accurate for specific landmarks, probably because the positions of the landmarks are easier to identify, facilitating learning by the artificial neural network, which justifies the previous results. However, these results must be interpreted very cautiously because this is only a subgroup analysis.

The results of the meta-analysis in this review should be interpreted critically and cautiously because only three [31, 32, 40] of the 40 studies included had a low risk of bias. This finding shows that, although extensive, the existing literature is limited by studies that may present some distortion in their results. According to the risk of bias analysis, patient selection was the domain in which most studies showed deficiencies, considering that few studies described in detail the sample selected and were not representative of the population. Another important source of bias was the description of the reference test. Considering it was a manual and examiner-dependent analysis, the studies should detail the form of manual identification of cephalometric landmarks and describe the type of calibration of evaluators, the number of assessments performed, and intra- and inter-examiner reliability. In this context, further studies should follow guidelines such as the CONSORT-AI and SPIRIT-AI [71] to perform and report AI analyses.

Among the limitations of this review, the low certainty of evidence stands out because of the high risk of bias in the eligible studies. Another limitation is the heterogeneity of analyses, especially for accuracy, probably because of the different methodologies and programming for AI identification and the heterogeneity of the datasets used. However, this is the most comprehensive systematic review with meta-analysis on using AI to identify cephalometric landmarks of orthodontic interest and the first to perform individual analyses for each cephalometric landmark.

Conclusion

AI shows good agreement for landmark placement on both 2D and 3D images and may assist in the final manual identification or confirmation of the positions for cephalometric landmarks, making this task faster and more precise. Further studies should be performed to expand the datasets used to include a more representative population, with study models of lower risks of biases, and aiming to overcome the limitations of the lack of a gold standard to identify cephalometric landmarks.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful for the support of Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico—Brazil (CNPq) and of Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais – Brazil (FAPEMIG).

Author Contribution

GQTBM: Conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript, final approval. WAV: Acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript, final approval. MTCV: Acquisition of data, drafting the manuscript, final approval. BANT: Drafting the manuscript, final approval. TLB: Drafting the manuscript, final approval. RSN: Drafting the manuscript, final approval. LRP: Drafting the manuscript, final approval. RBBJ: Conception and design, drafting the manuscript, final approval.

Funding

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brazil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Schwendicke F, Samek W, Krois J. Artificial Intelligence in Dentistry: Chances and Challenges. J Dent Res. 2020;99:769–774. doi: 10.1177/0022034520915714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naylor CD. On the prospects for a (deep) learning health care system. JAMA. 2018;320:1099–1100. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.11103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seyed Tabib NS, Madgwick M, Sudhakar P, et al. Big data in IBD: big progress for clinical practice. Gut. 2020;69:1520–1532. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-320065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeng T, Yu X, Chen Z. Applying artificial intelligence in the microbiome for gastrointestinal diseases: A review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36:832–840. doi: 10.1111/jgh.15503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muscogiuri G, Chiesa M, Trotta M, et al. Performance of a deep learning algorithm for the evaluation of CAD-RADS classification with CCTA. Atherosclerosis. 2020;294:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2019.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shimizu H, Nakayama KI. Artificial intelligence in oncology. Cancer Sci. 2020;111:1452–1460. doi: 10.1111/cas.14377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liang G, Fan W, Luo H, et al. The emerging roles of artificial intelligence in cancer drug development and precision therapy. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;128:110255. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olveres J, González G, Torres F, et al. What is new in computer vision and artificial intelligence in medical image analysis applications. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2021;11:3830–3853. doi: 10.21037/qims-20-1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kühnisch J, Meyer O, Hesenius M, et al. Caries Detection on Intraoral Images Using Artificial Intelligence. J Dent Res. 2022;101:158–165. doi: 10.1177/00220345211032524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baniulyte G, Ali K. Artificial intelligence - can it be used to outsmart oral cancer? Evid Based Dent. 2022;23:12–13. doi: 10.1038/s41432-022-0238-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Revilla-León M, Gómez-Polo M, Barmak AB, et al: Artificial intelligence models for diagnosing gingivitis and periodontal disease: A systematic review. J Prosthet Dent. 2022:S0022-3913(22)00075-0, 2022. 10.1016/j.prosdent.2022.01.026 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Silva VKS, Vieira WA, Bernardino ÍM, et al. Accuracy of computer-assisted image analysis in the diagnosis of maxillofacial radiolucent lesions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2020;49:20190204. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.20190204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fukuda M, Inamoto K, Shibata N, et al. Evaluation of an artificial intelligence system for detecting vertical root fracture on panoramic radiography. Oral Radiol. 2020;36:337–343. doi: 10.1007/s11282-019-00409-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Francisco I, Ribeiro MP, Marques F, et al: Application of Three-Dimensional Digital Technology in Orthodontics: The State of the Art. Biomimetics (Basel) 7:23, 2022. 10.3390/biomimetics7010023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Bichu YM, Hansa I, Bichu AY, et al. Applications of artificial intelligence and machine learning in orthodontics: a scoping review. Prog Orthod. 2021;22:18. doi: 10.1186/s40510-021-00361-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monill-González A, Rovira-Calatayud L, d'Oliveira NG, Ustrell-Torrent JM. Artificial intelligence in orthodontics: Where are we now? A scoping review. Orthod Craniofac Res Suppl. 2021;2:6–15. doi: 10.1111/ocr.12517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qian J, Luo W, Cheng M, Tao Y, Lin J, Lin H. Cepha NN: A Multi-Head Attention Network for Cephalometric Landmark Detection. IEEE Access. 2020;8: 112633-112641. 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3002939

- 18.Lindner C, Wang CW, Huang CT, et al. Fully Automatic System for Accurate Localisation and Analysis of Cephalometric Landmarks in Lateral Cephalograms. Sci Rep. 2016;6:33581. doi: 10.1038/srep33581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma Q, Kobayashi E, Fan B, et al. Automatic 3D landmarking model using patch-based deep neural networks for CT image of oral and maxillofacial surgery. Int J Med Robot. 2020;16:e2093. doi: 10.1002/rcs.2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwendicke F, Chaurasia A, Arsiwala L, et al. Deep learning for cephalometric landmark detection: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Investig. 2021;25:4299–4309. doi: 10.1007/s00784-021-03990-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;350:g7647. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aromataris E, Munn Z (Editors). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI, 2020. Available from https://synthesismanual.jbi.global. 10.46658/JBIMES-20-01

- 24.Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:529–536. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang CW, Huang CT, et al. Evaluation and Comparison of Anatomical Landmark Detection Methods for Cephalometric X-Ray Images: A Grand Challenge. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2015;34:1890–1900. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2015.2412951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol 64:383-394, 2011. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Giordano D, Leonardi R, Maiorana F, Cristaldi G, Distefano ML: Automatic Landmarking of Cephalograms by Cellular Neural Networks. In: Miksch S, Hunter J, Keravnou ET. (eds) Artificial Intelligence in Medicine. AIME 2005. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 2005;3581. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. 10.1007/11527770_46

- 28.Leonardi R, Giordano D, Maiorana F. An evaluation of cellular neural networks for the automatic identification of cephalometric landmarks on digital images. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2009;2009:717102. doi: 10.1155/2009/717102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vucinić P, Trpovski Z, Sćepan I. Automatic landmarking of cephalograms using active appearance models. Eur J Orthod. 2010;32:233–241. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjp099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tam WK, Lee HJ: Improving point registration in dental cephalograms by two-stage rectified point translation transform. Med Imag 2012: Image Processing. 2012;83141U. 10.1117/12.910935

- 31.Shahidi Sh, Oshagh M, Gozin F, Salehi P, Danaei SM. Accuracy of computerized automatic identification of cephalometric landmarks by a designed software. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2013;42:20110187. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.20110187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shahidi S, Bahrampour E, Soltanimehr E, et al. The accuracy of a designed software for automated localization of craniofacial landmarks on CBCT images. BMC Med Imaging. 2014;14:32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2342-14-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gupta A, Kharbanda OP, Sardana V, Balachandran R, Sardana HK. A knowledge-based algorithm for automatic detection of cephalometric landmarks on CBCT images. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2015;10:1737–1752. doi: 10.1007/s11548-015-1173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tam WK, Lee HJ. Improving point correspondence in cephalograms by using a two-stage rectified point transform. Comput Biol Med. 2015;65:114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2015.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vasamsetti S, Sardana V, Kumar P, Kharbanda OP, Sardana HK. Automatic Landmark Identification in Lateral Cephalometric Images Using Optimized Template Matching. J Med Imag Health Inform. 2015;15:458–470. doi: 10.1166/jmihi.2015.1426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Codari M, Caffini M, Tartaglia GM, Sforza C, Baselli G. Computer-aided cephalometric landmark annotation for CBCT data. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2017;12:113–121. doi: 10.1007/s11548-016-1453-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang J, Gao Y, Wang L, et al. Automatic Craniomaxillofacial Landmark Digitization via Segmentation-Guided Partially-Joint Regression Forest Model and Multiscale Statistical Features. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2016;63:1820–1829. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2015.2503421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arik SO, Ibragimov B, Xing L. Fully automated quantitative cephalometry using convolutional neural networks. J Med Imag. 2017;4:014501. doi: 10.1117/1.JMI.4.1.014501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee H, Park M, Kim J: Cephalometric landmark detection in dental x-ray images using convolutional neural networks. Medical Imaging 2017: Computer-Aided Diagnosis. 2017;101341W. 10.1117/12.2255870

- 40.de Jong MA, Gül A, de Gijt JP, et al. Automated human skull landmarking with 2D Gabor wavelets. Phys Med Biol. 2018;63:105011. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/aabfa0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Montúfar J, Romero M, Scougall-Vilchis RJ. Automatic 3-dimensional cephalometric landmarking based on active shape models in related projections. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2018;153:449–458. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2017.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Montúfar J, Romero M, Scougall-Vilchis RJ. Hybrid approach for automatic cephalometric landmark annotation on cone-beam computed tomography volumes. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2018;154:140–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2017.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Neelapu BC, Kharbanda OP, Sardana V, et al. Automatic localization of three-dimensional cephalometric landmarks on CBCT images by extracting symmetry features of the skull. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2018;47:20170054. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.20170054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang S, Li H, Li J, Zhang Y, Zou B. Automatic Analysis of Lateral Cephalograms Based on Multiresolution Decision Tree Regression Voting. J Healthc Eng. 2018;2018:1797502. doi: 10.1155/2018/1797502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen R, Ma Y, Chen N, Lee D, Wang W: Cephalometric Landmark Detection by Attentive Feature Pyramid Fusion and Regression-Voting. Comput Vis Pattern Recog. 2019.

- 46.Dai X, Zhao H, Liu T, Cao D, Xie L: Locating Anatomical Landmarks on 2D Lateral Cephalograms Through Adversarial Encoder-Decoder Networks. IEEE Access. 2019;99. 10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2940623

- 47.Kang SH, Jeon K, Kim HJ, Seo JK, Lee SH. Automatic three-dimensional cephalometric annotation system using three-dimensional convolutional neural networks: a developmental trial. Computer Methods in Biomechanics and Biomedical Engineering: Imaging & Visualization. 2019;8:210–218. doi: 10.1080/21681163.2019.1674696. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee SM, Kim HP, Jeon K, Lee SH, Seo JK. Automatic 3D cephalometric annotation system using shadowed 2D image-based machine learning. Phys Med Biol. 2019;64:055002. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/ab00c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nishimoto S, Sotsuka Y, Kawai K, Ishise H, Kakibuchi M. Personal Computer-Based Cephalometric Landmark Detection With Deep Learning, Using Cephalograms on the Internet. J Craniofac Surg. 2019;30:91–95. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000004901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Payer C, Stern D, Bischof H, Urschler M. Integrating spatial configuration into heatmap regression based CNNs for landmark localization. Med Imag Analys. 2019;54:207–219. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2019.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim H, Shim E, Park J, et al. Web-based fully automated cephalometric analysis by deep learning. Comput Meth Program Biomed. 2020;194:105513. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2020.105513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee JH, Yu HJ, Kim MJ, Kim JW, Choi J. Automated cephalometric landmark detection with confidence regions using Bayesian convolutional neural networks. BMC Oral Health. 2020;20:270. doi: 10.1186/s12903-020-01256-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li W, Lu Y, Zheng K, et al: Structured Landmark Detection via Topology-Adapting Deep Graph Learning. Comput Vis Pattern Recog 6, 2020. 10.1007/978-3-030-58545-7_16

- 54.Moon JH, Hwang HW, Yu Y, et al. How much deep learning is enough for automatic identification to be reliable? Angle Orthod. 2020;90:823–830. doi: 10.2319/021920-116.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Oh K, Oh IS, Le VNT, Lee DW. Deep Anatomical Context Feature Learning for Cephalometric Landmark Detection. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2020;25:806–817. doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2020.3002582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Noothout JMH, De Vos BD, Wolterink JM, et al. Deep Learning-Based Regression and Classification for Automatic Landmark Localization in Medical Images. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2020;39:4011–4022. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2020.3009002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Song Y, Qiao X, Iwamoto Y, Chen YW. Automatic Cephalometric Landmark Detection on X-ray Images Using a Deep-Learning Method. Appl Sci. 2020;10:2547. doi: 10.3390/app10072547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wirtz A, Lam J, Wesarg S. Automated Cephalometric Landmark Localization using a Coupled Shape Model. Curr Dir Biomed Eng. 2020;6:20203015. doi: 10.1515/cdbme-2020-3015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yun HS, Jang TJ, Lee SM, Lee SH, Seo JK. Learning-based local-to-global landmark annotation for automatic 3D cephalometry. Phys Med Biol. 2020;65:085018. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/ab7a71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zeng M, Yan Z, Liu S, Zhou Y, Qiu L. Cascaded convolutional networks for automatic cephalometric landmark detection. Med Image Anal. 2021;68:101904. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2020.101904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Huang Y, Fan F, Syben C, et al. Cephalogram Synthesis and Landmark Detection in Dental Cone-Beam CT Systems. Med Imag Analys. 2021;70:102028. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2021.102028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim MJ, Liu Y, Oh SH, et al: Automatic Cephalometric Landmark Identification System Based on the Multi-Stage Convolutional Neural Networks with CBCT Combination Images. Sensors (Basel) 21:505, 2021. 10.3390/s21020505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Kwon HJ, Koo H, Park J, Cho NI: Multistage Probabilistic Approach for the Localization of Cephalometric Landmarks. IEEE Access. 2021;9. 10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3052460

- 64.Lagravère MO, Low C, Flores-Mir C, et al. Intraexaminer and interexaminer reliabilities of landmark identification on digitized lateral cephalograms and formatted 3-dimensional cone-beam computerized tomography images. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;137:598–604. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kim JH, An S, Hwang DM. Reliability of cephalometric landmark identification on three-dimensional computed tomographic images. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2022;60:320–325. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2021.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Durão AP, Morosolli A, Pittayapat P, et al. Cephalometric landmark variability among orthodontists and dentomaxillofacial radiologists: a comparative study. Imaging Sci Dent. 2015;45:213–220. doi: 10.5624/isd.2015.45.4.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Míguez-Contreras M, Jiménez-Trujillo I, Romero-Maroto M, López-de-Andrés A, Lagravère MO. Cephalometric landmark identification consistency between undergraduate dental students and orthodontic residents in 3-dimensional rendered cone-beam computed tomography images: A preliminary study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2017;151:157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2016.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nalçaci R, Oztürk F, Sökücü O. A comparison of two-dimensional radiography and three-dimensional computed tomography in angular cephalometric measurements. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2010;39:100–106. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/82724776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sam A, Currie K, Oh H, Flores-Mir C, Lagravére-Vich M. Reliability of different three-dimensional cephalometric landmarks in cone-beam computed tomography: A systematic review. Angle Orthod. 2019;89:317–332. doi: 10.2319/042018-302.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nanni L, Ghidoni S, Brahnam S: Handcrafted vs. non-handcrafted features for computer vision classification. Pattern Recog 71:158–72, 2017. 10.1016/j.patcog.2017.05.025

- 71.Schwendicke F, Krois J. Better Reporting of Studies on Artificial Intelligence: CONSORT-AI and Beyond. J Dent Res. 2021;100:677–680. doi: 10.1177/0022034521998337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.