Abstract

Acute epiglottitis (AE) is a life-threatening condition and needs to be recognized timely. Diagnosis of AE with a lateral neck radiograph yields poor reliability and sensitivity. Convolutional neural networks (CNN) are powerful tools to assist the analysis of medical images. This study aimed to develop an artificial intelligence model using CNN-based transfer learning to identify AE in lateral neck radiographs. All cases in this study are from two hospitals, a medical center, and a local teaching hospital in Taiwan. In this retrospective study, we collected 251 lateral neck radiographs of patients with AE and 936 individuals without AE. Neck radiographs obtained from patients without and with AE were used as the input for model transfer learning in a pre-trained CNN including Inception V3, Densenet201, Resnet101, VGG19, and Inception V2 to select the optimal model. We used five-fold cross-validation to estimate the performance of the selected model. The confusion matrix of the final model was analyzed. We found that Inception V3 yielded the best results as the optimal model among all pre-train models. Based on the average value of the fivefold cross-validation, the confusion metrics were obtained: accuracy = 0.92, precision = 0.94, recall = 0.90, and area under the curve (AUC) = 0.96. Using the Inception V3-based model can provide an excellent performance to identify AE based on radiographic images. We suggest using the CNN-based model which can offer a non-invasive, accurate, and fast diagnostic method for AE in the future.

Keywords: Artificial intelligence, Emergency medicine, Convolutional neural networks, Transfer learning, Lateral neck radiographs, X-ray, Acute epiglottitis, Medical errors

Introduction

AE is characterized by acute inflammation and swelling of the epiglottis and adjacent tissues [1]. The bacterial invasion causes rapid swelling of the epiglottis, resulting in obstruction of the upper airway [2, 3]. Acute epiglottitis is a life-threatening disease [3] with a significant mortality rate of 7% among adults [4]. Once a patient is suspected of having AE, clinicians should provide intensive care to monitor the patency of the respiratory tract [4]. Delayed diagnosis may result in a severe outcome or even death [4, 5]. AE shares similar symptoms with many other upper respiratory tract diseases (e.g., croup). Therefore, diagnosing AE is difficult initially based on presenting symptoms in the emergency room [5].

Two diagnostic tools, including lateral neck radiography and fiberoptic laryngoscopy, have been commonly used to assist in diagnosing AE in addition to clinical symptoms. Fiberoptic laryngoscopy is a widely used invasive examination tool by otolaryngologists. The physician can use fiberoptic laryngoscopy to observe the abnormal swelling, ulcers, and suppuration near the epiglottis. Such an approach enables the physician to diagnose AE. Lateral neck X-ray is the most used non-invasive diagnostic imaging method to determine whether there is swelling in the tissues near the epiglottis. Radiographic imaging has certain advantages, including being non-invasive, fast, convenient, and inexpensive. However, the major drawback of neck radiography is poorer sensitivity and specificity than direct visualization using endoscopes [4]. However, emergency fiberoptic laryngoscopy is not always accessible in the emergency room in many hospitals. Additionally, an otolaryngologist may not be available for timely diagnosis at any arbitrary time. In many studies, AE has been described as a clinically under-recognized or delayed diagnosed disease [4].

Without specific geographic parameters, the reported diagnosis accuracy for AE based on X-ray images is relatively low, approximately 67% (range 50–90%) [6]. Studies have described radiological patterns on neck X-rays to diagnose AE, such as the thumb sign [7, 8] and vallecula sign [9]. However, these studies were conducted long ago and often included an insufficient sample size. Justification on the appearance of specific patterns on X-ray is subjective. Recent review articles question the sensitivity and specificity of the diagnostic value. More evidence regarding neck radiographic images in diagnosing AE is still required [10].

The development in AI-based healthcare has been booming in the recent decade [11]. For example, the AI analysis of chest radiographic images can provide consistent diagnostic performance as an expert when dealing with specific diseases [12]. Machine learning and neural network algorithms have enabled rapid and accurate diagnosis of many different conditions in diagnostic imaging [13]. Applying AI technology in healthcare will be a crucial aspect in the future [14]. Convolutional neural network (CNN) has been widely used in image classification, object detection, feature extraction, and other AI-based image processing applications. Several studies have demonstrated the successful application of transfer learning with pre-trained convolutional neural networks (CNN) in medical image analysis [12, 15].

A fast with an acceptable accurate method in the emergency room is critical to diagnose AE. The present study proposes an AI-based diagnostic model with transfer learning of pre-trained CNN to identify AE with neck radiographic images. The AI model can improve the accuracy compared to the manual interpretation of X-rays. The model of the present study will not only enable the rapid diagnosis of AE but also provide a reliable tool for physicians.

Materials and Methods

Subjects and Data

We collected the 1189 cases and radiographic images in this study from two hospitals in northern Taiwan. One of them is a medical center with an average of 10,000 emergency visits per month. The other one is a local teaching hospital with an average of 3000 emergency visits per month. IRB approved the present study (No.19MMHIS328e, MacKay Children’s Hospital; N202011046, Taipei Medical University Hospital). We included 251 patients fulfilling the following conditions in the AE group: (1) visited the hospitals between January 1, 2009, and January 1, 2020, (2) aged above 18 years, (3) received emergency admission and were diagnosed with AE (ICD9/ICD10) during discharge, and (4) the diagnosed of AE was confirmed by using fiberoptic laryngoscopy during the visit. We excluded patients from the experimental group based on the following criteria: (1) hospitalized for other comorbidities, (2) had a medical record of head and neck tumor (some patients might have received radiotherapy or surgery), (3) had trauma, (4) radiographs revealed foreign objects or implants, and (5) with significant cervical spine abnormalities as depicted on the radiographs.

Lateral neck radiographic images of patients fulfilling the following conditions were included in the control group: (1) visited the hospitals between January 1, 2009, and January 1, 2020; (2) aged above 18 years; (3) and with no records of respiratory symptoms, fever, or symptoms similar to AE. We selected 938 neck radiographic images from the outpatient clinic data matching the distribution of age and sex in the experimental group as the control group. The exclusion criteria were patients: (1) with a medical record of head and neck tumor (some might have received radiotherapy or surgery), (2) who had trauma, (3) with foreign objects or implants as observed using the neck radiographic image, and (4) with severe cervical spine abnormalities as depicted using the radiographs. The flowchart of data collection and process is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of data collection and procedure of data augmentation/model training

Image Preprocessing and Algorithm

We performed data augmentation of the AE images collected in the experimental group to convert the training data into balance data (to expand the size of the training set to 4 times the original set; 201 to 804). The data augmentation was operated by rotating the radiographic images clockwise and counterclockwise by 3° and clockwise by 5°. In the present study, we used image enhancement and normalization to minimize the acquisition variation caused by the small sample size. Appropriate image contrast normalization and enhancement can help interpret medical images [16]. Histogram equalization (HE) is one of the pixel brightness transformations techniques, and it has been widely used in medical imaging processing because of its high efficiency. HE will compute the histogram of pixel values of the input image and calculate the cumulative distribution function and then scale the input image using the cumulative distribution function to produce the output image. After pre-processing images by HE, an improvement of the image data suppresses undesired distortions or enhances some appearance features relevant for further processing and analysis [17, 18]. The region of interest (ROI) algorithm localized a specific area from an image. ROI can extract valuable information for diagnosis in the original image and maintain good image quality during the image decompression process of CNN, which can avoid interfering with results and speed up calculations. We used the aggregate channel feature (ACF) detector to detect the ROI focus on epiglottis and the adjacent regions [19]. First, 200 images were randomly selected from all the image data, and an emergency doctor manually cropped the structure near the epiglottis. Then we used the ACF object detector to train a model that automatically detects the ROI of the epiglottis. When automatically detecting neck X-rays, the ROI model will give three sets of ideal box boundaries. Take the intersection of these three boundaries as ROI, including the epiglottis and nearby structures (such as the trachea, cervical spine), and exclude other irrelevant areas (skull bone, ribs, and soft tissue of chest wall).

Pre-trained CNN Model and Model Training

This study investigated five widely used pre-trained CNN models: Inception V3 [20], Inception-Resnet-v2 [21], VGG19 [22], DenseNet201 [23], and Resnet101 [24]. Many diagnostic imaging studies used specific CNN architecture to perform transfer learning [12, 25–27] . After image preprocessing and detecting the ROI, the images were then resized for different models (299 × 299 pixels for Inception V3 and Inception-Resnet-v2; 224 × 224 pixels for VGG19, DenseNet201, and Resnet101) and used as the input to train the pre-trained CNN. This study used MATLAB (MATLAB 2019a, MathWorks, MA, USA) to perform image preprocessing, model training, and statistical analysis. The hyperparameters used in model training are as follows: optimization algorithm, stochastic gradient descent with momentum; mini-batch size, 20; max epochs, 6; initial learning rate, 0.0001

Statistical Analysis

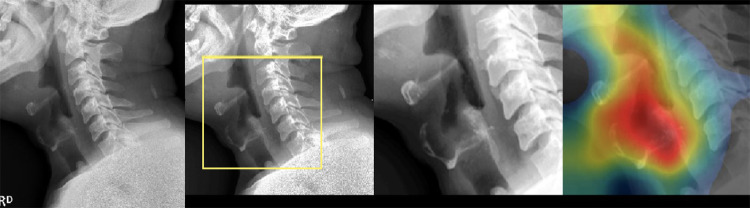

We compared and evaluated the performance of five pre-trained CNN models (Inception V3, Inception-Resnet-v2, VGG19, DenseNet20, and Resnet101) with a confusion matrix. We then selected the Inception V3 for its best performance for further analysis. We used 5-fold cross-validation to evaluate the performance of the Inception V3 model on the test dataset. These performance metrics, including AUROC, confusion matrix, and F-score, were computed to assess the model’s performance. Finally, we used class activation mapping (CAM) to visualize regions on which the neural networks mainly focus. The visualization results also were used to validate whether the prediction results obtained from the model were accurate and consistent with the clinical diagnosis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Procedures involved in the analysis of neck X-ray images: from left to right: raw image, region of interest (ROI) detection, resize and normalization, and class activation mapping (CAM) visualization

Results

Demographic Data

The AE group comprised lateral neck radiographic images of 251 patients with AE (62.2%, male; 37.8%, female). The average age of all the patients included in the experimental group was 46.2±14.4 years. The control group comprised neck radiographic images of 938 patients, of whom 63.0% were male and 37.0% were female. The average age of the patients included in the control group was 46.0±15.2 years (Table 1). The most prevalent age of AE patients was 41 to 51 years old (25.1%).

Table 1.

Demographic distribution of patients

| Acute epiglottitis group | Controls | |

|---|---|---|

| Cases | 251 | 938 |

| Sex M/F (%) | 156 (62.2)/95 (37.8) | 591 (63.0)/347 (37.0) |

| Age (%) | ||

| < 20 | 7 (2.8) | 30 (3.2) |

| 21–30 | 33 (13.1) | 118 (12.6) |

| 31–40 | 52 (20.7) | 194 (20.7) |

| 41–50 | 63 (25.1) | 234 (24.9) |

| 51–60 | 56 (22.3) | 210 (22.4) |

| 61–70 | 26 (10.4) | 90 (9.6) |

| 71–80 | 12 (4.8) | 54 (5.8) |

| > 80 | 2 (0.8) | 8 (0.9) |

| Mean age (years) | 46.2 ± 14.4 | 46.0 ± 15.2 |

Among all the data in the AE group (251 patients), 20% (50 patients) were randomly selected and used as the test set, while the remaining 80% (201 patients) were used as the training set. Fifty patients were randomly selected from all the datasets in the group without AE (938 patients) and used as the test set, while the remaining patients (888 patients) were used as the training set. The image data in the training set of the patient with the AE group were augmented to 804 cases. We used these images and the 888 cases from the control group to train the Inception V3 model.

Comparison of Different Pre-trained CNN Models

In the first part of this study, we randomly divided the neck radiographic images into two datasets (80% for training, 20% for testing). Following this approach, we compared the performance of five different pre-trained CNN models that were commonly used in diagnostic imaging. As shown by the results of this study, we found that the Inception V3 model had the best analysis performance among all models (precision of 0.89, recall of 0.86, and AUC of 0.91. F-score=0.88). We summarized the corresponding results in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of five commonly used pre-trained CNN models

| Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | Precision | Recall | AUC | F score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inception V3 | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.9 | 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.91 | 0.88 |

| Densenet201 | 0.78 | 0.55 | 1 | 1 | 0.55 | 0.92 | 0.82 |

| Resnet101 | 0.85 | 0.72 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.72 | 0.96 | 0.82 |

| VGG19 | 0.57 | 0.28 | 0.86 | 0.67 | 0.28 | 0.57 | 0.71 |

| InceptionResNet-v2 | 0.74 | 0.55 | 0.93 | 0.89 | 0.55 | 0.88 | 0.68 |

AUC area under curve

Five-Fold Cross-Validation of Inception V3 as the Final Model

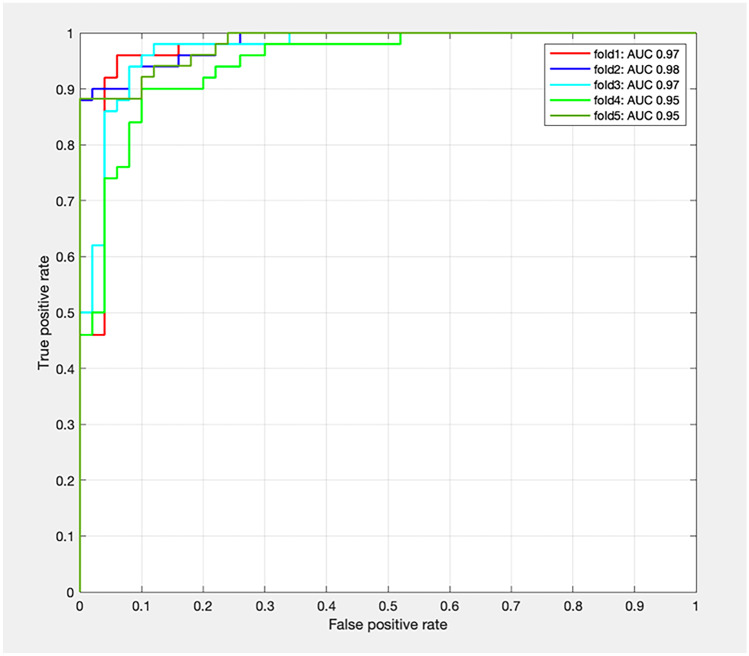

The performance of the trained model was then validated using the test set by five-fold cross-validation. The performance metrics were obtained by taking the average value of these results (Table 3), which yielded the following results: accuracy = 0.92, precision = 0.94, recall = 0.90, and AUC = 0.96. We plotted the receiver operating characteristic curve of each dataset as Fig. 3.

Table 3.

Results of five-fold cross-validation using Inception V3 as the pertained model

| Fold | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | Precision | Recall | F score | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.97 |

| 2 | 0.93 | 0.9 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.9 | 0.93 | 0.98 |

| 3 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.97 |

| 4 | 0.87 | 0.84 | 0.9 | 0.89 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.95 |

| 5 | 0.92 | 0.84 | 1 | 1 | 0.84 | 0.91 | 0.95 |

| Mean | 0.92 | 0.9 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.9 | 0.91 | 0.96 |

AUC area under curve

Fig. 3.

The area under the curve (AUC) of the cross-validation results

Discussion

We proposed the first CNN-based model to identify AE in the lateral neck X-ray images to our best knowledge. We used Inception V3 as the pre-trained transfer learning model on the lateral neck radiographic images, providing an excellent capability to identify AE. Apart from a high level of sensitivity and specificity, this model features a high AUC of 0.96, a precision (positive predictive value) of 0.94, a recall (negative predictive value) of 0.90, and an F-score of 0.91. Medical errors led to significant mortality and morbidity. For example, approximately 250,000 deaths occurred in the USA in 2016. It was found that 10–15% of these deaths were associated with diagnostic errors [28]. It is worth noting that diagnostic errors occur most frequently in the emergency room, consisting of 43.5% of medical errors [29]. In the emergency room, the prolonged working hours, patient crowd, and insufficient human labor cause the clinical physician to underperform during diagnosis, resulting in more significant medical errors. In addition, many conditions in the emergency room need to be diagnosed and managed timely. AI can serve as a complementary way to help physicians achieve safer care in this scenario.

AE can be diagnosed by simply tracking the geographic features of the neck radiographic image, such as the thumb sign and vallecula sign. However, recent reviews have shown that several clinicians often interpret the diagnostic results (e.g., medical students, radiologists, otolaryngologists, and emergency physicians), leading to inter-rater differences [12]. Prospective studies in recent years have found that the diagnostic capability of the thumb and vallecula sign is not as good as that reported in the original literature [30]. When diagnosing AE, physicians may not interpret the neck radiographic image correctly if they do not have sufficient clinical experience in analyzing these images [10].

Previous research have demonstrated that specific parameters in a neck x-ray, such as the width of the epiglottis base, can enhance the accuracy of diagnosis. However, this method still requires accurate marking and measurements of the corresponding structure by users. In reality, significant errors in measurements conducted by different individuals often exist, particularly for people without adequate training. Therefore, such a method may not be a robust diagnostic approach. Physicians were required to measure specific parameters to diagnose patients with AE manually. Such an approach is time-consuming. Even using a parameter-based neck radiographic image, diagnosing AE is still challenging for emergency physicians.

Clinicians usually first pay attention to the location of the potential lesion in the image when they analyze a medical image with a specific impression. However, when the image is analyzed using CNN, the non-relevant area containing minimal diagnosis information may “distract” the model. Using the whole image consequently demands higher computational resources during AI recognition. ROI algorithm can extract useful information from the original image for diagnosis and maintain a high image quality during the image decompression process [31]. Therefore, we extracted the anatomical structures of interest and improved model performance using the ROI algorithm in the present study. This approach can prevent interference from other areas in the image and accelerate the computational speed [32].

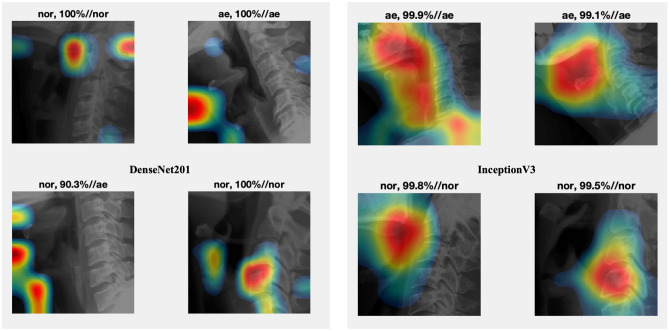

CNN comprises various network layers, which can handle non-linear data with high freedom (such as images). However, the results obtained from CNN lack interpretability, and establishing the relationship between the input and the output from the model itself is challenging [33]. Due to the poor explainability of CNN compared to other machine learning algorithms, researchers often need to convince themselves that CNN has a decent performance before applying such a method. Alternatively, researchers require greater confidence when employing the CNN algorithm. CAM is a valuable tool that can visualize the characteristics extracted by CNN effectively [34]. When researchers need to adjust the training parameters of different algorithms during the study, CAM can help them evaluate which model performs better and is reasonable. For example, we found that the Inception V3 model better recognized the structure near the epiglottis than DenseNet201 under the same condition (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of different feature regions in the convolutional neural network (CNN) model by class activation mapping (CAM)

This study evaluated five widely used pre-trained CNN models, including Inception V3, Inception-Resnet-v2, VGG19, DenseNet201, and Resnet101, to develop the transfer learning model for analyzing the neck radiographic image. We found that Inception V3 was the best model among all tested models in both sensitivity and specificity in identifying AE. It is worth noting that the CNN model with a greater number of layers or a more complex structure did not necessarily perform better. The characteristics of the data may affect the performance of models as well. When analyzing medical images using a pre-trained model developed for recognizing natural images, those models with fewer layers and simpler architecture may provide a better interpretation result [35]. The model selection is task-sensitive.

AI is an objective tool minimizing the errors caused by inter-rater evaluation. Its performance will be affected by neither the working environment nor the prolonged working hours. AI technology has shown the potential to improve the medical service in the emergency system [36]. We suggest introducing the CNN model into the imaging diagnosis process and potentially changing current practices. The AI model developed in this study can provide a diagnostic result within seconds. Combing with the automatic alert system can be implemented in the clinical workflow to facilitate timely management of AE in the future.

We addressed several insufficiencies in the present study. First, the datasets used in the present study are from the Han Chinese population. Even no ethnic difference in the clinical characteristics of AE is reported currently, validation of our model in different ethnic groups is advised. Second, we used a relatively small dataset to construct CNN models because AE is an uncommon disease. Verifying our model with a larger population is suggested. Third, we have included the datasets from different hospitals to improve the representativity of AE. The clinical characteristics of the patients in the present study group were compatible with previous observations [37, 38], including (1) male patients were predominant; (2) the majority of the patients were aged between 31 and 60 years (68%). External validation with the data from more hospitals is still necessary. Fourth, we used convenient sampling from other clinical settings as the control X-ray images of the neck. This approach may introduce some variation and bias in the datasets. Fifth, when initially collecting cases, we considered the differences in anatomical structures between adults and children and the possible differences in growth patterns at different ages in children. As a result, this study initially excluded pediatric patients (under 18 years old) and focused on adults with acute epiglottitis, using relatively standardized adult imaging to build a CNN model. However, after this study, it was determined that the CNN model had certain performance, so collecting more cases of children in the future to train the next CNN model to interpret the imaging of acute epiglottitis in children is the future challenge and goal. Finally, due to the limitations on patient conditions in the design of this research, we need to carefully screen patients who meet the inclusion criteria of this study and then accurately interpret them using the AI model. In the future, our research direction will also involve collecting more cases in different populations for model training to reduce inclusion criteria restrictions and make more patients can benefit from this model, in order to increase the practical application of this model in the medical world. In addition, prospective research must also be conducted to verify the diagnostic performance of this model when applied in a medical setting.

Conclusions

We demonstrate that using Inception V3-based model can provide excellent performance in identifying AE on lateral neck radiographic images. We suggest using the CNN-based model on neck radiographic images which can offer a non-invasive, accurate, and fast diagnostic method for AE in the future. Further study is advised to confirm the external validation of our models in the real world.

Abbreviations

- AE

Acute epiglottitis

- CNN

Convolutional neural networks

- AI

Artificial intelligence

- HE

Histogram equalization

- ROI

Region of interest (ROI)

- ACF

Aggregate channel feature

- CAM

Class activation mapping

Author Contribution

Yang-Tse Lin, MD: conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data.

Ben-Chang Shia, Ph.D.: development of the theoretical formulation

Chia-Jung Chang, MD: conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data

Yueh Wu, MD: conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data

Jheng-Dao Yang, MD: concept and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data

Jiunn-Horng Kang, MD Ph.D.: development of the theoretical formulation, performed the analytic calculations and performed the numerical simulations, contributed to the final version of the manuscript

All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis, and manuscript.

Data Availability

Due to privacy and ethical concerns, neither the data nor the source of the data can be made available.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rafei K, Lichenstein R. Airway infectious disease emergencies. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2006;53(2):215–242. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sato S, Kuratomi Y, Inokuchi A. Pathological characteristics of the epiglottis relevant to acute epiglottitis. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2012;39(5):507–511. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li CJ, Aronowitz P. Sore throat, odynophagia, hoarseness, and a muffled, high-pitched voice. Cleve Clin J Med. 2013;80(3):144–145. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.80a.12056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.B. Westerhuis, M.G. Bietz, J. Lindemann, Acute epiglottitis in adults: an under-recognized and life-threatening condition, S D Med 66(8) (2013) 309–11, 313. [PubMed]

- 5.Lee DR, Lee CH, Won YK, Suh DI, Roh EJ, Lee MH, Chung EH. Clinical characteristics of children and adolescents with croup and epiglottitis who visited 146 Emergency Departments in Korea. Korean J Pediatr. 2015;58(10):380–385. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2015.58.10.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.K.H. Kim, Y.H. Kim, J.H. Lee, D.W. Lee, Y.G. Song, S.Y. Cha, S.Y. Hwang, Accuracy of objective parameters in acute epiglottitis diagnosis: A case-control study, Medicine (Baltimore) 97(37) (2018) e12256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Podgore JK, Bass JW. Letter: The "thumb sign" and "little finger sign" in acute epiglottitis. J Pediatr. 1976;88(1):154–155. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(76)80754-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.C. Grover, Images in clinical medicine. "Thumb sign" of epiglottitis, N Engl J Med 365(5) (2011) 447. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Ducic Y, Hebert PC, MacLachlan L, Neufeld K, Lamothe A. Description and evaluation of the vallecula sign: a new radiologic sign in the diagnosis of adult epiglottitis. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;30(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(97)70102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujiwara T, Miyata T, Tokumasu H, Gemba H, Fukuoka T. Diagnostic accuracy of radiographs for detecting supraglottitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acute Med Surg. 2017;4(2):190–197. doi: 10.1002/ams2.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pesapane F, Codari M, Sardanelli F. Artificial intelligence in medical imaging: threat or opportunity? Radiologists again at the forefront of innovation in medicine. European Radiology Experimental. 2018;2(1):35. doi: 10.1186/s41747-018-0061-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.P. Rajpurkar, J.A. Irvin, K. Zhu, B. Yang, H. Mehta, T. Duan, D.Y. Ding, A. Bagul, C. Langlotz, K.S. Shpanskaya, M.P. Lungren, A. Ng, CheXNet: Radiologist-Level Pneumonia Detection on Chest X-Rays with Deep Learning, ArXiv abs/1711.05225 (2017).

- 13.W. Sarle (1994). ”Neural Networks and Statistical Models”, Proceedings of the Nineteenth Annual SAS Users Group International Conference, Cary, NC: SAS Institute, USA, pp. 1538-1550.

- 14.Topol EJ. High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat Med. 2019;25(1):44–56. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0300-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qin C, Yao D, Shi Y, Song Z. Computer-aided detection in chest radiography based on artificial intelligence: a survey. Biomed Eng Online. 2018;17(1):113. doi: 10.1186/s12938-018-0544-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.R. Kushol, M.N. Raihan, M.S. Salekin, A.B.M.A. Rahman, Contrast Enhancement of Medical X-Ray Image Using Morphological Operators with Optimal Structuring Element, ArXiv abs/1905.08545 (2019). 10.48550/arXiv.1905.08545, May 19, 2019.

- 17.S.H. Lim, N.A.M. Isa, C.H. Ooi, K.K.V. Toh, A new histogram equalization method for digital image enhancement and brightness preservation, Signal Image Video P 9(3) (2015) 675–689.

- 18.Yoon H-S, Han Y, Hahn H-S. Image Contrast Enhancement based Sub-histogram Equalization Technique without Over-equalization Noise, World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology, International Journal of Electrical, Computer, Energetic, Electronic and Communication. Engineering. 2009;3:189–195. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dollar P, Appel R, Belongie S, Perona P. Fast Feature Pyramids for Object Detection. Ieee T Pattern Anal. 2014;36(8):1532–1545. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2014.2300479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.C. Szegedy, V. Vanhoucke, S. Ioffe, J. Shlens, Z. Wojna, Rethinking the Inception Architecture for Computer Vision, 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) (2016) 2818–2826.

- 21.C. Szegedy, S. Ioffe, V. Vanhoucke, A.A. Alemi, Inception-v4, Inception-ResNet and the Impact of Residual Connections on Learning, AAAI, 2017. https://arxiv.org/abs/1905.08545, February 12, 2017.

- 22.K. Simonyan, A. Zisserman, Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition, CoRR abs/1409.1556 (2015). 10.48550/arXiv.1409.1556, April 10, 2015.

- 23.Rubin J, Parvaneh S, Rahman A, Conroy B, Babaeizadeh S. Densely connected convolutional networks for detection of atrial fibrillation from short single-lead ECG recordings. J Electrocardiol. 2018;51(6S):S18–S21. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2018.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.K. He, X. Zhang, S. Ren, J. Sun, Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition, 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) (2016) 770–778. 10.1109/CVPR.2016.90, December 12, 2016.

- 25.X. Wang, Y. Peng, L. Lu, Z. Lu, M. Bagheri, R.M. Summers, ChestX-Ray8: Hospital-Scale Chest X-Ray Database and Benchmarks on Weakly-Supervised Classification and Localization of Common Thorax Diseases, 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) (2017) 3462–3471. 10.1109/CVPR.2017.369, November 09, 2017.

- 26.Abràmoff MD, Lou Y, Erginay A, Clarida W, Amelon RE, Folk JC, Niemeijer M. Improved Automated Detection of Diabetic Retinopathy on a Publicly Available Dataset Through Integration of Deep Learning. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2016;57(13):5200–5206. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-19964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gulshan V, Peng L, Coram M, Stumpe MC, Wu D, Narayanaswamy A, Venugopalan S, Widner K, Madams T, Cuadros J, Kim R, Raman R, Nelson PC, Mega JL, Webster DR. Development and Validation of a Deep Learning Algorithm for Detection of Diabetic Retinopathy in Retinal Fundus Photographs. JAMA. 2016;316(22):2402–2410. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.17216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maurette P, Sfa CAMR. To err is human: building a safer health system. Ann Fr Anesth. 2002;21(6):453–454. doi: 10.1016/S0750-7658(02)00670-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.P. Asadi, E. Modirian, N. Dadashpour, Medical Errors in Emergency Department; a Letter to Editor, Emergency (Tehran, Iran) 6(1) (2018) e33. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Fujiwara T, Okamoto H, Ohnishi Y, Fukuoka T, Ichimaru K. Diagnostic accuracy of lateral neck radiography in ruling out supraglottitis: a prospective observational study. Emerg Med J. 2015;32(5):348–352. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2013-203340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D. Yee, S. Soltaninejad, D. Hazarika, G. Mbuyi, R. Barnwal, A. Basu, Medical image compression based on region of interest using better portable graphics (BPG), 2017 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC) (2017) 216–221. 10.1109/SMC.2017.8122605, November 30, 2017.

- 32.Q. Zhang, H. Xiao, Extracting Regions of Interest in Biomedical Images, 2008 International Seminar on Future BioMedical Information Engineering (2008) 3–6. 10.1109/FBIE.2008.8, December 18, 2008.

- 33.J. Aneja, A. Deshpande, A.G. Schwing, Convolutional Image Captioning, 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (2018) 5561–5570. 10.48550/arXiv.1805.09019, May 23, 2018.

- 34.B. Zhou, A. Khosla, À. Lapedriza, A. Oliva, A. Torralba, Learning Deep Features for Discriminative Localization, 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) (2016) 2921–2929. 10.48550/arXiv.1512.04150, December 14, 2015.

- 35.M. Raghu, C. Zhang, J.M. Kleinberg, S. Bengio, Transfusion: Understanding Transfer Learning with Applications to Medical Imaging, ArXiv abs/1902.07208 (2019). 10.48550/arXiv.1902.07208, October 29, 2019.

- 36.K.L. Grant, A. Mcparland, Applications of artificial intelligence in emergency medicine, University of Toronto Medical Journal 96(1) (2019). Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332566835_Applications_of_artificial_intelligence_in_emergency_medicine, January 17, 2023.

- 37.Hanna J, Brauer PR, Berson E, Mehra S. Adult epiglottitis: Trends and predictors of mortality in over 30 thousand cases from 2007 to 2014. Laryngoscope. 2019;129(5):1107–1112. doi: 10.1002/lary.27741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shah RK, Stocks C. Epiglottitis in the United States: national trends, variances, prognosis, and management. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(6):1256–1262. doi: 10.1002/lary.20921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Due to privacy and ethical concerns, neither the data nor the source of the data can be made available.