Abstract

Introduction

Neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD) is the world’s leading cause of blindness in elderly people. While anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) treatments are used as the first option for patients with nAMD, they are generally expensive and need repeated injections. This study aimed to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of anti-VEGF therapies, focusing on the newly launched ranibizumab biosimilar (RBZ BS) in patients with nAMD from a Japanese societal perspective.

Methods

A Markov model was developed to simulate the lifetime transitions of a cohort of treatment-naïve patients with nAMD through health states that were based on the involvement of nAMD (single eye vs. both eyes), the treatment status of the patients, and decimal best-corrected visual acuity. The model compared RBZ BS with branded RBZ, aflibercept (AFL), and AFL as loading dose switched to RBZ BS in maintenance in the treat-and-extend (TAE) regimen (RBZ TAE, AFL TAE, and AFL to RBZ BS TAE, respectively), and with branded RBZ in the pro re nata (PRN) regimen, as well as best supportive care (BSC). All processes were validated by five clinical experts.

Results

When TAE regimens were compared, RBZ BS was dominant (higher quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and lower total cost) to AFL TAE and AFL to RBZ BS TAE. The result was robust regardless of whether the clinical data were taken from the direct head-to-head clinical trial or from indirect treatment comparison. RBZ BS TAE was cost-saving compared to RBZ TAE. RBZ BS TAE was estimated to be dominant to BSC owing to a lower societal cost. Like TAE regimens, RBZ BS was cost-saving compared to RBZ PRN and was dominant to BSC in PRN regimens.

Conclusion

This study suggests that RBZ BS is dominant to other anti-VEGF treatments in patients with nAMD in both TAE and PRN regimens and BSC from a Japanese societal perspective.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40123-023-00715-y.

Keywords: Cost-effectiveness, Costs and cost analysis, Dosing regimens, Japan, Markov model, Neovascular age-related macular degeneration, Ranibizumab biosimilar, Societal perspective

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Ranibizumab biosimilar (RBZ BS, Senju Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.) was the first BS of an ophthalmic vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitor RBZ in Japan, which demonstrated comparable quality, efficacy, and safety for the treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD). |

| The cost-effectiveness of the various anti-VEGF therapies is still unknown in Japan. |

| This study aimed to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of anti-VEGF therapy with a focus on RBZ BS in the treat-and-extend (TAE) and pro re nata (PRN) regimens in patients with nAMD from a Japanese societal perspective. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| The model demonstrated RBZ BS TAE being dominant to aflibercept (AFL) TAE owing to slightly higher QALYs at a lower total cost. RBZ BS TAE was cost-saving compared to RBZ TAE. RBZ BS TAE was estimated to be dominant to best supportive care (BSC) owing to a lower societal cost. Similar to TAE regimens, RBZ BS was cost-saving compared to RBZ PRN and was dominant to BSC in PRN regimens. |

| This study suggests that RBZ BS is a dominant alternative over other widely used anti-VEGF treatments by both TAE and PRN regimens in patients with nAMD in Japan. In addition, when considering the productivity loss of caregivers, RBZ BS is dominant to BSC in both TAE and PRN regimens. |

Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD), a leading cause of blindness in developed countries, is a progressive condition that leads to severe visual impairment with increasing age [1, 2]. A systematic literature review of studies conducted before 2013 estimated that approximately 170 million individuals aged 45–85 years were affected by AMD globally, with a prevalence of 8.7% [3]. The number of people with AMD is projected to reach 288 million by the year 2040 [3]. Japan has one of the most aged populations in the world and hence the number of patients with AMD is projected to grow as the population continues to age [4].

In clinical practice, AMD is classified into early and late stages, in which late-stage AMD includes geographic atrophy (GA) or neovascular AMD (nAMD) subtypes [5]. GA is characterized by atrophy of the central macula and destruction of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and photoreceptors [5]. nAMD, a more common condition than GA among patients with late-stage AMD in Asian countries [6], is characterized by the exudation of fluid and blood from new blood vessels into the macula (macular neovascularization, MNV), causing subretinal scarring [5].

Common treatments available for nAMD are anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) agents and photodynamic therapy (PDT) [7]. However, PDT is less commonly used since the advent of anti-VEGF therapy, with the use of PDT limited to a special subtype of nAMD, polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy (PCV). As of 2020, the global anti-VEGF market for retinal diseases has exceeded $7.0 billion and the treatments are used as the first-choice treatment type for patients with nAMD [8–10]. There are two major anti-VEGF agents widely used for nAMD in Japan: ranibizumab (Lucentis®; Genentech, USA) and aflibercept (Eylea®; Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, USA). Despite their clinical benefits, these anti-VEGF agents are expensive and repeated injections are needed to maintain visual acuity. Therefore, the advent of biosimilars was long awaited and they are expected to improve the treatment of nAMD from a health economic perspective.

A ranibizumab biosimilar by Senju Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Ranibizumab BS; Senju Pharmaceuticals, Japan) was approved in September 2021 and entered the Japanese marketplace. This product is the first biosimilar of an ophthalmic VEGF inhibitor in Japan. Owing to its lower price compared to the original ranibizumab, ranibizumab BS is expected to reduce not only the economic burden on patients with nAMD but also the burden on society at large.

Although there are studies that have evaluated the cost-effectiveness of anti-VEGF agents in Japan and other countries [11–20], there is no health economic analysis of a BS of intraocular anti-VEGF agents. Moreover, previous cost-effectiveness analyses relied on limited data on the treatment outcomes from fixed or pro re nata (PRN) regimens. Although the PRN regimen is still commonly used in Japan [21], the proportion of anti-VEGF regimen administrations is changing, with the treat-and-extend (TAE) dosing regimen being prescribed over PRN regimens, and the corresponding accumulating clinical evidence. Therefore, to account for these changes, there is a need to update the cost-effectiveness analysis of anti-VEGF treatments for nAMD. In an effort to address this gap in knowledge, this study assessed the cost-effectiveness of anti-VEGF therapy, focusing on ranibizumab BS in TAE and PRN regimens in patients with nAMD from a Japanese societal perspective.

Methods

Model Structure

Experts in retinal diseases (YY, KT, TI, FG, and TS) had face-to-face and online meetings to form the key parameters of the model structure.

A de novo Markov state-transition cohort model was built in Microsoft Excel for Microsoft 365 (Redmond, WA, USA). The model was based on a previous study [11] and used to simulate the lifetime transitions of a cohort of treatment-naïve patients with nAMD through health states based on the involvement of nAMD (single-eye vs. both-eye involvement), the treatment status of the patient (i.e., on or off treatment), and decimal best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA).

Primary Health States

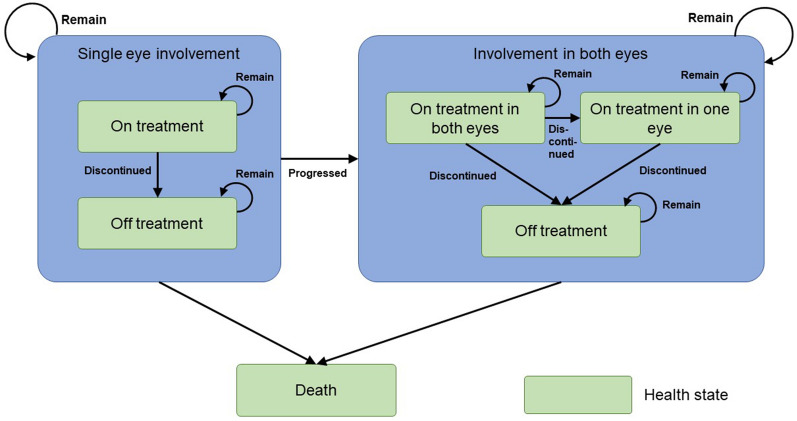

The model consisted of three mutually exclusive primary health states: single-eye involvement, both-eye involvement, and death. For single-eye involvement, the health state can be changed from being on treatment to off treatment, while for both-eye involvement, the health state can be changed from being on treatment in both eyes to off treatment (Fig. 1). The overall structure of the treatment pathway was similar to a previous study [11]. All patients entering the model were assumed to have required treatment for at least one eye affected by nAMD (treated eye). Several patients who had nAMD in the second (fellow) eye at the time of entry into the model were assumed to have initiated bilateral treatment. The remaining patients, whose fellow eye was unaffected by nAMD, initiated unilateral treatment. Data regarding the proportion of patients affected by nAMD in both eyes at model entry were obtained from previous literature on Japanese patients [22]. Patients who initiated unilateral treatment were assumed to be at risk of developing nAMD in the fellow eye and receive treatment during the model time horizon based on the annual risk of involvement of both eyes. In those patients, treatment was initiated at the time of fellow-eye involvement and therefore later as compared with treatment initiation in the first affected eye. Involvement of nAMD, treatment status, and BCVA were updated every 3 months in a recurring fixed interval (model cycle).

Fig. 1.

Overview of the model structure

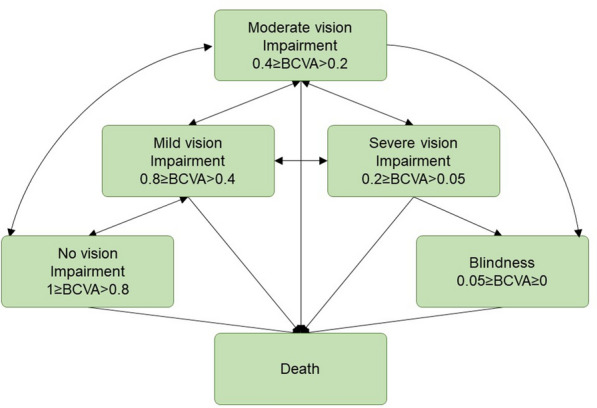

Sub-Health States

In line with a previous health economic modelling study related to nAMD [12], Markov sub-health states based on BCVA were incorporated into the model. In the previous study [12], the substates described the extent of visual impairment and ranged from no visual impairment to blindness and were defined as: (1) no visual impairment (BCVA 0.8–1.0); (2) mild visual impairment (BCVA 0.4–0.8); (3) moderate visual impairment (BCVA 0.2–0.4); (4) severe visual impairment (BCVA 0.05–0.2); and (5) blindness (BCVA ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Schematic for sub-health states. BCVA best-corrected visual acuity

Each eye was modelled independently of the other. After the involvement of both eyes, the fellow eye was assumed to receive the same treatment as the first affected eye as soon as the disease developed and experienced the same benefits from treatment. Patients entered the model with the distribution of respective BCVA for treated and fellow eyes according to the distributions estimated in a previous study [23].

Health Transitions Within Sub-Health States

After entering the model, all patients were assigned to any of the considered treatments in this study and underwent three treatment phases: induction, maintenance, and off treatment. During each treatment phase, the health state (a) remained at the current level of BCVA; (b) improved one or two health states (defined by 15 and 30 letters in the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study, ETDRS); or (c) worsened one or two health states. The assigned treatment could be discontinued in any treatment phase, according to the predefined discontinuation rates dependent on the treatment phase. In the active treatment arms, patients were assumed to be treated with anti-VEGF for a maximum of 5 years. After treatment discontinuation, the health state did not improve, but rather remained stable or worsened, as suggested by previous epidemiological studies [24, 25]. The health state was also assumed to remain unchanged when a patient reached the blindness state. BCVA in the eye unaffected by nAMD was assumed to remain stable.

General Settings

The cycle length of the model was 3 months, and a 20-year time horizon was considered to cover the patients’ lifetime [26] based on the mean age of the patient population (74 years [27]) in Japan. The analysis was done from a societal perspective in Japan. An increase in mortality among patients with nAMD was not considered. Background Japanese mortality was used throughout the model, based on the Japanese life table for 2021 [26]. Health outcomes and costs were discounted at a rate of 2% per year, based on local guidelines [28].

Treatments

Interventions and Comparators

The cost-effectiveness model compared long-term healthcare costs and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) of patients treated with RBZ BS versus other active anti-VEGF treatments and best supportive care (BSC). The cost-effectiveness analysis was conducted separately for each dosing regimen, i.e., TAE and PRN. In TAE regimens, RBZ BS TAE was compared with RBZ (i.e., Lucentis®) TAE (RBZ TAE), aflibercept (i.e., Eylea®) TAE (AFL TAE), aflibercept as the loading dose (i.e., induction phase) switched to RBZ BS in the maintenance phase (AFL TAE to RBZ BS), and BSC (regular follow-up with ophthalmological examinations only). In PRN regimens, RBZ BS PRN was compared with RBZ PRN and BSC. It is worth noting that RBZ BS was not compared with AFL with PRN regimen since AFL was commonly treated with TAE regimen in Japan. In this study, different transition probabilities between health states and treatment frequencies were assigned to each dosing regimen. The efficacy parameters of RBZ BS were assumed to be comparable with those of its brand drug, Lucentis®.

Dosing Schedule

After entry, all patients were assigned to any of the above treatments and administered three initial monthly injections if they were assigned to an active treatment (induction phase). After the induction phase, the modelled patients received treatments according to the dosing regimens (TAE or PRN), which were defined for each anti-VEGF agent regimen and the time from the initial treatment (i.e., years 1, 2, and 3–5) (maintenance phase).

Model Inputs and Data Sources

Baseline Characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the cohort were based on previous epidemiological studies on Japanese patients with nAMD when available. The percentage of patients with nAMD in both eyes was 19% [22], and the initial cohort distributions by BCVA of the first and fellow eyes were based on another randomized control study [23].

Clinical Inputs

Transition probabilities and treatment frequencies for each treatment and regimen were inferred from previous clinical trials (Supplementary Material Tables S1–S3). In TAE regimens, a head-to-head comparison study (RIVAL study [29]) was used to compare the efficacy between RBZ TAE and AFL TAE for 2 years from entry, while equivalent efficacies regarding BCVA and treatment frequencies were assumed in years 3 and later [30]. According to opinion from Ohji et al. [31], the robustness of the model was estimated in a scenario analysis using model inputs based on the indirect treatment comparison, where the comparison of the BCVA change and the treatment frequency for 2 years between RBZ TAE and AFL TAE was estimated through network meta-analysis and matching-adjusted indirect comparison. For PRN regimens, transition probabilities and treatment frequencies were obtained from the Comparison of Age-related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials (CATT) study [32–34].

Annual incidence of fellow-eye involvement was estimated by Ueta et al. [35] (Supplementary Material Table S4). Treatment discontinuation was defined by annual discontinuation rates for each treatment phase and treatment arm (except for BSC). Annual discontinuation rates were determined on the basis of expert opinion (Supplementary Material Table S4). As a result of a lack of clinical data, discontinuation rates were assumed to depend only on the treatment period since the initial anti-VEGF treatment and remained the same among all treatment arms.

Adverse events (AEs) considered in this study were based on the serious AEs reported in the RIVAL study [29]. The annual rates of AEs were derived from clinical trials and expert opinion, and the disutility related to each AE was based on Brown et al. [15, 17] (Supplementary Material Table S5). AEs were assumed to occur as one-off events based on the incidence rates defined for each treatment. The associated costs and reductions in utility were considered for each AE.

Utility Inputs

Health state utility values were independent of the treatment arm and assigned to each health state of the affected eye, i.e., a worse-seeing eye for single-eye involvement and a better-seeing eye for both-eye involvement. In this study, utility data were inferred from a previous study [12] (Supplementary Material Table S6). For patients with single-eye involvement, the utility at each severity was defined on the basis of a range of 0.1. For patients with both-eye involvement, the observed utility values followed the better-seeing eye. The maximum range of utilities between no visual impairment and blindness for single-eye involvement follows the discussion in the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence technology (NICE) appraisal guidance for RBZ and pegaptanib for the treatment of AMD [36].

Cost Inputs

The direct medical costs included drug administration (drug acquisition and intravitreal injection), regular monitoring (follow-up visits, regular laboratory tests), and AEs. Indirect costs included productivity loss among informal caregivers accompanying a patient to the physician’s office or providing care during daily life. All costs were reported in Japanese yen (JPY) in 2022 and were obtained from the Japanese medical service fee schedule, revised in April 2022 [37]. Drug prices were retrieved from the National Health Insurance drug price list from April 2022 [38].

Drug administration cost was calculated for each treatment phase (induction, maintenance [years 1, 2, and 3–5], and off treatment) by considering drug acquisition prices, the frequency of administrations, and medical service fees for intravitreal injection (Supplementary Material Table S7).

The resource utilization for each AE was calculated primarily as described in a previous study [12] as well as from expert opinion. Costs were calculated on the basis of the corresponding medical service fees [37] (Supplementary Material Table S7).

Costs related to monitoring and management of the disease were obtained from a previous Japanese study [12] (Supplementary Material Table S8). Annual resource consumption for each treatment arm was estimated on the basis of the same study [12]. It is worth noting that no additional monitoring costs were assumed between the patients with single-eye and both-eye involvement, although the monitoring costs for the fellow eye were incurred if the patient discontinued the treatment in the first eye. Monitoring and management costs assumed for RBZ BS were the same as for Lucentis®.

In this study, two types of societal costs for informal caring were considered: (a) societal costs related to accompanying a patient to the physician’s office, and (b) societal costs related to daily care (Supplementary Material Table S9). Both types of societal costs were derived on the basis of expert opinion. The societal costs related to accompanying a patient to the physician’s office were derived on the basis of whether accompaniment was necessary or not for each level of visual impairment. The corresponding costs were estimated by the frequency of physician visits, the average daily wage of Japanese laborers, and average transportation costs. The average daily wage of Japanese laborers was JPY 15,218.2, based on the Basic Survey on Wage Structure in 2021 by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) [39]. The average transportation cost was estimated at JPY 4547 (JPY 4714 after being inflated to 2022 rates) [40]. Societal costs regarding daily care were derived on the basis of the productivity loss of caregivers supporting the patient for daily care (i.e., work-loss days per month). Annual societal costs were derived on the basis of work-loss days and the average daily wage (JPY 15,218.2).

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study is based on data from previously conducted studies and does not contain any novel data from human participants. Therefore, this study complies with ethical guidelines and did not require an ethics review.

Analysis

The main analytic framework was a cost-effectiveness analysis, estimating costs and health outcomes of each intervention and comparator. The expected cost per patient for each treatment strategy was calculated by summing up the costs associated with each health state, multiplied by the probability of a patient being in that health state for each point in time (i.e., each model cycle). A 3-month cycle length with half cycle correction was applied.

The cost-effectiveness of each treatment was determined by dividing the total average cost per patient by the health benefits it brings, resulting in a cost per QALY gained. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was determined by calculating the differences in costs and utilities between competing alternatives (i.e., the cost of the extra benefit received from the target intervention over the benefits received from the comparators). A willingness-to-pay threshold (WTP) of JPY 5,000,000 per QALY gained was used for this cost-effectiveness analysis [41].

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to account for uncertainties around the model parameters and determine the robustness of model conclusions. One-way deterministic sensitivity analysis (DSA) was performed on all relevant model parameters except for the fixed drug prices and model framework such as time horizon and cycle length. Discount rates were varied between 0 and 4% based on the Japanese guidelines [28]. The deterministic sensitivity analysis was conducted by increasing and decreasing each model parameter by 20%. The probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) was conducted through Monte Carlo simulation with 10,000 iterations and the distributions used are presented in Supplementary Material Table S10.

Results

Base-Case Analysis

When the RBZ BS TAE regimen was compared with other TAE regimens and BSC, a patient on RBZ BS TAE accumulated 8.081 QALYs compared to 8.067, 8.072, and 7.772 QALYs on AFL TAE, AFL to RBZ BS TAE, and BSC, respectively (Table 1). The incremental difference in QALYs was 0.015, 0.009, and 0.310 QALYs, with RBZ BS TAE relative to AFL TAE, AFL to RBZ BS TAE, and BSC, respectively. The total treatment costs over a lifetime for RBZ BS TAE was JPY 23,991,569, while the costs for RBZ TAE, AFL TAE, AFL to RBZ BS TAE, and BSC were JPY 25,207,027, JPY 26,066,752, JPY 24,283,390, and JPY 27,530,971, respectively (Table 1). RBZ BS TAE was associated with a lower total cost of JPY 1,215,458 relative to its brand drug, Lucentis® (RBZ TAE). The difference in total cost for RBZ BS TAE compared to other active comparators and BSC was JPY − 2,075,183, JPY − 291,822, and JPY − 3,539,402 for AFL TAE, AFL to RBZ BS TAE, and BSC, respectively (Table 1). Therefore, treatment with RBZ BS TAE (intervention) was dominant over other anti-VEGF treatments as well as BSC by slightly higher or equal incremental QALYs at a lower total cost.

Table 1.

Base-case cost-effectiveness results (RBZ BS TAE vs. comparators)

| Outcome | Intervention | Comparators | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBZ BS TAE | RBZ TAE | AFL TAE | AFL to RBZ BS TAE | BSC | |

| Total QALYs | 8.081 | 8.081 | 8.067 | 8.072 | 7.772 |

| Total costs (JPY) | 23,991,569 | 25,207,027 | 26,066,752 | 24,283,390 | 27,530,971 |

| Difference in QALYs | – | 0.000 | 0.015 | 0.009 | 0.310 |

| Difference in costs (JPY) | – | − 1,215,458 | − 2,075,183 | − 291,822 | − 3,539,402 |

| ICER (JPY/QALY) | – | Comparable effectiveness with lower cost | Dominant | Dominant | Dominant |

AFL aflibercept, BS biosimilar, BSC best supportive care, ICER incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, JPY Japanese yen, QALYs quality-adjusted life-years, RBZ ranibizumab, TAE treat-and-extend

The reduced total cost in RBZ BS TAE mainly resulted from a lower drug acquisition cost in comparison with AFL TAE (JPY − 1,948,929) and AFL to RBZ BS TAE (JPY − 111,691) regimens. When RBZ BS TAE was compared with BSC, although BSC did not incur drug and administration costs, the higher societal costs due to daily care for BSC resulted in a lower total cost for RBZ BS TAE (Table 2).

Table 2.

Total and breakdown of average costs (base case): TAE regimens

| RBZ BS TAE | RBZ TAE | AFL TAE | AFL to RBZ BS TAE | BSC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Costs by category (JPY) | |||||

| Drugs and administration | 3,012,571 | 4,228,029 | 4,961,499 | 3,124,261 | 0 |

| Monitoring | 107,460 | 107,460 | 107,252 | 106,990 | 59,334 |

| Adverse events | 2958 | 2958 | 16,420 | 2943 | 0 |

| Societal cost—daily care | 20,645,101 | 20,645,101 | 20,756,712 | 20,824,152 | 27,333,398 |

| Societal cost—physician visit | 223,479 | 223,479 | 224,868 | 225,044 | 138,238 |

| Total | 23,991,569 | 25,207,027 | 26,066,752 | 24,283,390 | 27,530,971 |

| Difference in costs by category (JPY) | |||||

| Drugs and administration | – | − 1,215,458 | − 1,948,929 | − 111,691 | 3,012,571 |

| Monitoring | – | 0 | 207 | 470 | 48,126 |

| Adverse events | – | 0 | − 13,462 | 15 | 2958 |

| Societal cost—daily care | – | 0 | − 111,611 | − 179,051 | − 6,688,297 |

| Societal cost—physician visit | – | 0 | − 1389 | − 1565 | 86,241 |

| Total | – | − 1,215,458 | − 2,075,183 | − 291,822 | − 3,539,402 |

AFL aflibercept, BS biosimilar, BSC best supportive care, JPY Japanese yen, PRN pro re nata, RBZ ranibizumab, TAE treat-and-extend

Regarding the comparison among PRN regimens, both RBZ BS PRN and RBZ PRN yielded 8.078 QALYs at a total cost of JPY 23,268,866 and JPY 24,085,662, respectively (Table 3). As a result, RBZ BS PRN was associated with a lower total cost of JPY 816,795 compared to its brand drug, Lucentis® (RBZ PRN). RBZ BS PRN gained 0.306 more QALYs compared with BSC while it incurred JPY 4,262,104 less total cost, resulting in a dominant ICER (Table 3).

Table 3.

Base-case cost-effectiveness results (RBZ BS PRN vs. comparators) and breakdown of average costs (base case) for PRN regimens

| Intervention | Comparators | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| RBZ BS PRN | RBZ PRN | BSC | |

| Outcome | |||

| Total QALYs | 8.078 | 8.078 | 7.772 |

| Total costs (JPY) | 23,268,866 | 24,085,662 | 27,530,971 |

| Difference in QALYs | – | 0.000 | 0.306 |

| Difference in costs (JPY) | – | − 816,795 | − 4,262,104 |

| ICER (JPY/QALY) | – | Comparable effectiveness with lower cost | Dominant |

| Costs by category (JPY) | |||

| Drugs and administration | 2,024,466 | 2,841,261 | 0 |

| Monitoring | 153,240 | 153,240 | 59,334 |

| Adverse events | 273 | 273 | 0 |

| Societal cost—daily care | 20,755,274 | 20,755,274 | 27,333,398 |

| Societal cost—physician visit | 335,614 | 335,614 | 138,238 |

| Total | 23,268,866 | 24,085,662 | 27,530,971 |

| Difference in costs by category (JPY) | |||

| Drugs and administration | – | − 816,795 | 2,024,466 |

| Monitoring | – | 0 | 93,906 |

| Adverse events | – | 0 | 273 |

| Societal cost—daily care | – | 0 | − 6,578,124 |

| Societal cost—physician visit | – | 0 | 197,376 |

| Total | – | − 816,795 | − 4,262,104 |

BS biosimilar, BSC best supportive care, ICER incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, JPY Japanese yen, PRN pro re nata, RBZ ranibizumab

Scenario Analysis for Aflibercept TAE Regimen

In the scenario analysis for RBZ BS TAE versus AFL TAE, the robustness of the model was estimated using clinical data from the indirect treatment comparison in which the average number of injections in the RBZ TAE group was higher by 6.12 injections (in maintenance phase) for 2 years compared to AFL TAE according to Ohji et al. [31]. RBZ BS TAE was dominant and was associated with lower total costs compared with AFL TAE (JPY 683,286) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Cost-effectiveness results of scenario using data from the indirect treatment comparison

| Outcome | Intervention | Comparators |

|---|---|---|

| RBZ BS TAE | AFL TAE | |

| Total QALYs | 8.081 | 8.071 |

| Total costs (JPY) | 23,991,569 | 24,674,855 |

| Difference in QALYs | – | 0.010 |

| Difference in costs (JPY) | – | − 683,286 |

| ICER (JPY/QALY) | – | Dominant |

AFL aflibercept, BS biosimilar, BSC best supportive care, ICER incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, JPY Japanese yen, QALYs quality-adjusted life-years, RBZ ranibizumab, TAE treat-and-extend

The lower total cost in RBZ BS TAE was mainly derived from a lower drug and administration cost (JPY − 639,084) compared to AFL TAE (Table 5). Compared to the base case using a head-to-head study [29], however, in a scenario from a separate study [31], the differences were smaller because of the lower treatment frequencies for AFL TAE and a slightly smaller difference in BCVA for 2 years between RBZ TAE and AFL TAE.

Table 5.

Total and breakdown of average costs per patient (scenario using the indirect treatment comparison)

| RBZ BS TAE | AFL TAE | |

|---|---|---|

| Costs by category (JPY) | ||

| Drugs and administration | 3,012,571 | 3,651,654 |

| Monitoring | 107,460 | 107,370 |

| Adverse events | 2958 | 16,440 |

| Societal cost—daily care | 20,645,101 | 20,675,770 |

| Societal cost—physician visit | 223,479 | 223,621 |

| Total | 23,991,569 | 24,674,855 |

| Difference in costs by category (JPY) | ||

| Drugs and administration | – | − 639,084 |

| Monitoring | – | 90 |

| Adverse events | – | − 13,493 |

| Societal cost—daily care | – | − 30,669 |

| Societal cost—physician visit | – | − 142 |

| Total | – | − 683,286 |

AFL aflibercept, BS biosimilar, BSC best supportive care, JPY Japanese yen, RBZ ranibizumab, TAE treat-and-extend

Deterministic Sensitivity Analysis

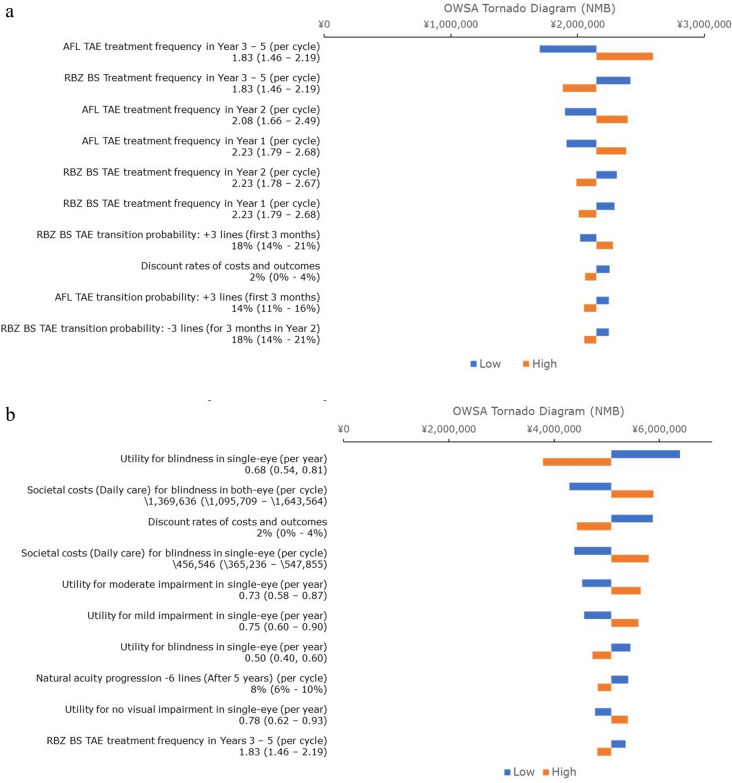

A one-way DSA was performed, and the ten most important drivers of the model were plotted in a tornado diagram (Fig. 3a). The top three influential parameters for RBZ BS TAE versus AFL TAE were (1) treatment frequency of AFL TAE in years 3–5 (higher to favorable for RBZ BS TAE); (2) treatment frequency of RBZ BS TAE in years 3–5 (lower to favorable for RBZ BS TAE); and (3) treatment frequency of AFL TAE in year 2 (higher to favorable for RBZ BS TAE).

Fig. 3.

Tornado diagrams. a RBZ BS TAE versus AFL TAE. b RBZ BS TAE versus BSC. AFL aflibercept, BS biosimilar, BSC best supportive care, NMB net monetary benefit, OWSA one-way sensitivity analysis, RBZ ranibizumab, TAE treat-and-extend

In the analysis of RBZ BS TAE versus BSC, the top three parameters with the greatest impact on the model results were (1) utility of blindness in single eye (lower to favorable for RBZ BS TAE); (2) societal costs regarding daily care for a patient with blindness (higher to favorable for RBZ BS TAE); and (3) discount rates of costs and outcomes (lower to favorable for RBZ BS TAE) (Fig. 3b).

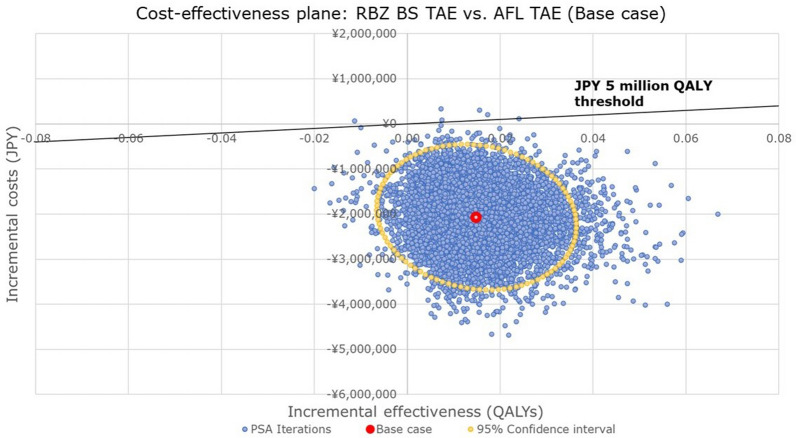

Probabilistic Sensitivity Analysis

A cost-effectiveness plane was generated to show the result of PSA comparing RBZ BS TAE to AFL TAE (Fig. 4). The results showed that 98.0% of the iterations were estimated in the southeast (SE) quadrant, implying that RBZ BS TAE was highly likely to be dominant over AFL TAE with the possible ranges of input parameters (± 20% of point estimates). Moreover, only 0.05% of iterations were estimated to be higher than the WTP threshold of JPY 5,000,000 per QALY gained (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Cost-effectiveness plane comparing incremental cost and effectiveness for RBZ BS TAE with AFL TAE (base case). AFL aflibercept, BS biosimilar, JPY Japanese yen, PSA probabilistic sensitivity analysis, QALYs quality-adjusted life-years, RBZ ranibizumab, TAE treat-and-extend

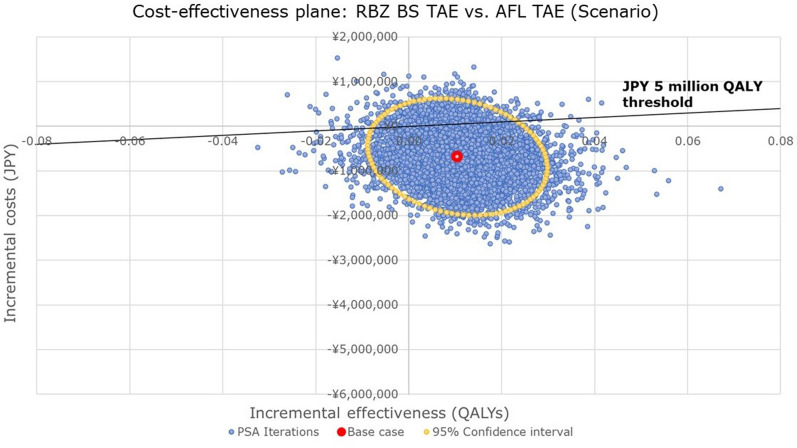

The PSA results of RBZ BS TAE versus AFL TAE with the clinical data from an indirect comparison by a different study scenario [31] were also presented (Fig. 5). In this analysis, 84.1% of the iterations were recognized as dominant, indicating that RBZ BS TAE was still likely to be dominant over AFL TAE. The probability of exceeding the WTP threshold of JPY 5,000,000 per QALY gained was estimated at 8.7% (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Cost-effectiveness plane comparing incremental cost and effectiveness for RBZ BS TAE with AFL TAE (scenario using the indirect treatment comparison). AFL aflibercept, BS biosimilar, JPY Japanese yen, PSA probabilistic sensitivity analysis, QALYs quality-adjusted life-years, RBZ ranibizumab, TAE treat-and-extend

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study comparing the cost-effectiveness of RBZ BS with existing anti-VEGF agents among treatment-naïve patients with nAMD. Despite several assumptions and uncertainties regarding the long-term efficacy data, the present model provides the most realistic representation of the current Japanese clinical practice for nAMD; the model closely follows the current nAMD disease pathway for anti-VEGF agents in patients with nAMD by incorporating the risk of fellow-eye involvement and a combination of different levels of visual impairment and health state utilities in both eyes. Notably, the model allows for the simulation of lifetime transitions of a cohort of patients with nAMD through health states based on involvement of nAMD (single eye vs. both-eye involvement), patients’ treatment status (i.e., on or off treatment), and severity of visual impairment defined by decimal BCVA, as proposed in Hernandez et al. [11] and Yanagi et al. [12].

Among TAE regimens, RBZ BS TAE was estimated to be a dominant approach over AFL TAE even when using a conservative estimate, i.e., an indirect treatment comparison used by Ohji et al. [31]. This suggests that RBZ BS is highly likely a cost-saving option compared to the AFL TAE regimen with lower cost and comparable or slightly better benefits. It is worth noting that the magnitude of difference in 2-year treatment frequencies (number of injections) between RBZ (or RBZ BS) TAE and AFL TAE in the indirect comparison study [31] was 5.9 times higher, which appears to be larger than the estimated outcome from real-world practice, as suggested by retrospective observational studies conducted in Japan and other foreign settings [42–45]. This is particularly important since the findings of our DSA suggested that the treatment frequencies of RBZ and AFL are the key drivers of ICERs. The PSA also validated the results from the base-case cost-effectiveness analysis and estimated RBZ BS to be a dominant approach in 97.9% of iterations with the possible ranges of input parameters (± 20% of point estimates).

Moreover, RBZ BS TAE was estimated to be dominant to BSC considering the societal costs depending on the severity of visual impairment. Therefore, it can be inferred that visual impairment in the elderly population can pose a huge economic burden on society in terms of productivity losses among caregivers. Although utility data related to the visual acuity of the worst-seeing eye in the single-eye involvement is limited, the model in this study compensates for this by assuming that the difference of utilities between no visual impairment and blindness is 0.1, which is considered as conservative according to the opinion of Appraisal Committee from NICE [36] (“the difference in utility difference was substantially smaller than that between very good and very poor vision in the better-seeing eye”). It is notable that RBZ BS PRN is also dominant to BSC for the same reason.

The inputs used in the model were derived from patients treated in a randomized clinical study setting [29], which may not always reflect the real-world clinical setting in Japan. However, the baseline characteristics and outcomes reported from patients in the clinical study that provided the model inputs were similar to those reported from patients in actual practice in Japan and have been validated by Japanese clinical experts. Moreover, the trial comparators were largely aligned with the standard management practices of nAMD observed in real-world clinical practice in Japan. For the reasons above, the results from this study provide insights into the importance of the treatment of nAMD and the cost-effective treatment option for treatment-naïve patients with nAMD after the advent of ranibizumab BS.

The results of our study must be interpreted with caution, considering a few limitations pertaining to the modelling approach. First, the transition probabilities and treatment frequencies after the third year were assumed to be comparable between RBZ and AFL TAE. This was due to the long-term changes in visual acuity and treatment frequency for these regimens, which were not well documented in the literature. Second, the discontinuation rates for all treatments and treatment regimens were assumed to be the same because these values were not available, especially in the Japanese clinical setting. This might be a strong assumption, as discontinuation rates could vary according to patients’ economic status and treatment types—as suggested by previous studies in foreign settings [46–48]. Nevertheless, this assumption is likely to yield a conservative estimate for RBZ BS, since less costly BS should result in a smaller financial burden on patients compared to brand drugs. Third, since the utility for the visual acuity of the worst-seeing eye in the single-eye involvement was lacking, we assumed a reduction of 0.1 utility value for blindness compared to no visual impairment, which is in line with the NICE HTA appraisal [36] and was considered a conservative estimate. Fourth, since the productivity loss of caregivers with daily care related to the severity of visual impairment was not available in existing studies and relied on expert opinions, the societal costs may be subject to their individual clinical experiences. Fifth, although bevacizumab is currently available in Japan for certain cancers, the off-label use for nAMD is prohibited by Japan and it therefore was not considered for this study.

Despite the existence of several assumptions and uncertainties, especially in long-term efficacy data, the present model provides the most realistic representation of the current Japanese clinical practice for nAMD, which closely follows the current nAMD disease pathway for anti-VEGF agents in patients with nAMD by incorporating the risk of fellow-eye involvement. The model also includes a combination of different levels of visual impairment and health state utilities in both eyes. Notably, the model allows for the simulation of lifetime transitions of a cohort of patients with nAMD through health states, based on the involvement of nAMD (single-eye vs. both-eye involvement), patients’ treatment status (i.e., on or off treatment), and the severity of visual impairment defined by decimal BCVA, as previously proposed in the cost-effectiveness analyses [11, 12]. Additionally, our analysis focused on the two most commonly used anti-VEGF agents, RBZ and AFL. However, the other recently approved anti-VEGF agents for nAMD in Japan (brolucizumab (Beovu®) and faricimab (Vabysmo®)) were not considered because of the limited efficacy evidence. Future studies using these agents as potential comparators would be helpful in analyzing the cost-effectiveness of RBZ BS.

Conclusion

Based on the currently available evidence, our analyses show with a high degree of certainty that RBZ BS can be the most cost-saving treatment option compared with the existing anti-VEGF agents by both TAE and PRN regimens in patients with nAMD from a Japanese societal perspective. Moreover, RBZ BS is dominant over BSC in both TAE and PRN regimens, for which there are significant productivity losses for the caregivers. These findings provide valuable insights into the treatment of nAMD and the cost-effective treatment option in treatment-naïve patients with nAMD following the advent of RBZ BS.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study and its publication, including the journal’s Rapid Service Fee, was funded by Senju Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

Medical writing support was provided by Anshika Singhal and Saurabh Trikha of IQVIA, India.

Author Contributions

Yasuo Yanagi, Kanji Takahashi, Tomohiro Iida, Fumi Gomi, Eriko Kunikane and Taiji Sakamoto were involved in the conception and design, interpretation of the data and critical revision for intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be published.Junko Morii was involved in the conception and design, interpretation of the data, drafting of the paper, and final approval for publication.All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosures

Yasuo Yanagi, Kanji Takahashi, Tomohiro Iida, Fumi Gomi and Taiji Sakamoto report honorarium from Senju during the conduct of the study.Yasuo Yanagi reports financial support from – Alcon Japan, Sanbio; consultant – Roche, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer; lecturer – Chugai, Novartis, Bayer, Santen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Senju.Kanji Takahashi reports consultant for - Novartis, Bayer, Kyowa Kirin, Santen, Allergan; lecture fees – Novartis, Bayer, Santen, Senju.Tomohiro Iida reports consultant for – Bayer, Novartis, Chugai, Boehringer Ingelheim; lecture fees and grant support – AMO, Alcon, Bayer, Canon, HOYA, Nikon, Nidek, Novartis, Otsuka, Pfizer, Santen, Senju, and Topcon outside the submitted work.Fumi Gomi reports honorarium from – Bayer, Novartis, Santen, Senju; support for attending meetings and/ or travel – Bayer, Novartis, Santen, Senju.Taiji Sakamoto reports appointment as a consultant & advisory board – Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Chugai, Senju, Santen.Junko Morii is an employee of IQVIA, which was contracted by Senju to perform the analyses.Eriko Kunikane is an employee of Senju.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study is based on data from previously conducted studies and does not contain any novel data from human participants. Therefore, this study complies with ethical guidelines and did not require an ethics review.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article/as supplementary information files.

Footnotes

The original online version of this article was revised to correct few statements in the text.

Change history

8/11/2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s40123-023-00788-9

References

- 1.Yanagi Y, Aihara Y, Fukuda T, Hashimoto H. Cost-effectiveness of ranibizumab, photodynamic therapy and pegaptanib sodium in the treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration in Japan. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi (J Jpn Ophthalmol Soc) 2011;115:825–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bressler NM. Age-related macular degeneration is the leading cause of blindness. JAMA. 2004;291(15):1900–1901. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.15.1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong WL, Su X, Li X, et al. Global prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(2):e106–e116. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70145-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yasuda M. Observational study (cohort study): the Hisayama study. J Eye. 2009;26(1):25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathenge W. Age-related macular degeneration. Community Eye Health. 2014;27(87):49–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rim TH, Kawasaki R, Tham Y-C, et al. Prevalence and pattern of geographic atrophy in Asia: the Asian Eye Epidemiology Consortium. Ophthalmology. 2020;127(10):1371–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Solomon SD, Lindsley K, Vedula SS, Krzystolik MG, Hawkins BS. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;3(3):Cd00139. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005139.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takahashi K, Oshima Y, Ohnaka M, Koizumi H, Maruko I, Yasukawa T. Clinical evidence and real clinical practice of wet age-related macular degeneration therapy. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi (J Jpn Ophthalmol Soc) 2020;124:902–924. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chappelow AV, Kaiser PK. Neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Drugs. 2008;68(8):1029–1036. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200868080-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van de Wiele VL, Hammer M, Parikh R, Feldman WB, Sarpatwari A, Kesselheim AS. Competition law and pricing among biologic drugs: the case of VEGF therapy for retinal diseases. J Law Biosci. 2022;9(1):lsac001. doi: 10.1093/jlb/lsac001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hernandez L, Lanitis T, Cele C, Toro-Diaz H, Gibson A, Kuznik A. Intravitreal aflibercept versus ranibizumab for wet age-related macular degeneration: a cost-effectiveness analysis. J Manag Spec Pharmacy. 2018;24(7):608–616. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2018.24.7.608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yanagi Y, Fukuda A, Barzey V, Adachi K. Cost-effectiveness of intravitreal aflibercept versus other treatments for wet age-related macular degeneration in Japan. J Med Econ. 2017;20(2):204–212. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2016.1245196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patel JJ, Mendes MA, Bounthavong M, Christopher ML, Boggie D, Morreale AP. Cost-utility analysis of bevacizumab versus ranibizumab in neovascular age-related macular degeneration using a Markov model. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18(2):247–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neubauer AS, Holz FG, Sauer S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of ranibizumab for the treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration in Germany: model analysis from the perspective of Germany's statutory health insurance system. Clin Ther. 2010;32(7):1343–1356. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown MM, Brown GC, Brown HC, Peet J. A value-based medicine analysis of ranibizumab for the treatment of subfoveal neovascular macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(6):1039–45.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fletcher EC, Lade RJ, Adewoyin T, Chong NV. Computerized model of cost-utility analysis for treatment of age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(12):2192–2198. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown GC, Brown MM, Brown HC, Kindermann S, Sharma S. A value-based medicine comparison of interventions for subfoveal neovascular macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(6):1170–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bansback N, Davis S, Brazier J. Using contrast sensitivity to estimate the cost-effectiveness of verteporfin in patients with predominantly classic age-related macular degeneration. Eye (Lond) 2007;21(12):1455–1463. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown GC, Brown MM, Sharma S, et al. The burden of age-related macular degeneration: a value-based medicine analysis. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2005;103:173–184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma S, Brown GC, Brown MM, Hollands H, Shah GK. The cost-effectiveness of photodynamic therapy for fellow eyes with subfoveal choroidal neovascularization secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2001;108(11):2051–2059. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(01)00764-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takahashi K, Oshima Y, Koizumi H, et al. Current situation of management for wet age-related macular degeneration in Japanese clinical practice: questionnaire survey in expert doctors. Ophthalmology. 2020;62(5):491–502. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maruko I, Iida T, Saito M, Nagayama D, Saito K. Clinical characteristics of exudative age-related macular degeneration in Japanese patients. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144(1):15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolf S, Bandello F, Loewenstein A, et al. Baseline characteristics of the fellow eye in patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration: post hoc analysis of the VIEW studies. Ophthalmologica. 2016;236(2):95–99. doi: 10.1159/000447725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong TY, Chakravarthy U, Klein R, et al. The natural history and prognosis of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(1):116–126. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elshout M, Webers CA, van der Reis MI, de Jong-Hesse Y, Schouten JS. Tracing the natural course of visual acuity and quality of life in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review and quality of life study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2017;17(1):120. doi: 10.1186/s12886-017-0514-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (MHLW). Abridged life table for Japan. 2021. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/life/life21/index.html. Accesssed 6 Feb 2023.

- 27.Ohji M, Takahashi K, Okada AA, Kobayashi M, Matsuda Y, Terano Y. Efficacy and safety of intravitreal aflibercept treat-and-extend regimens in exudative age-related macular degeneration: 52- and 96-week findings from ALTAIR: a randomized controlled trial. Adv Ther. 2020;37(3):1173–1187. doi: 10.1007/s12325-020-01236-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Center for Outcomes Research and Economic Evaluation for Health-National Institute of Public Health (C2H Japan). Guideline for preparing cost-effectiveness evaluation to the central social insurance medical council. Version 3. 2022. http://c2h.niph.go.jp/tools/guideline/guideline_ja.pdf. Accesssed 6 Feb 2023.

- 29.Gillies MC, Hunyor AP, Arnold JJ, et al. Macular atrophy in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: a randomized clinical trial comparing ranibizumab and aflibercept (RIVAL study) Ophthalmology. 2020;127(2):198–210. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kertes PJ, Sheidow T, Williams G, Greve M, Galic IJ, Baker J. Long-term efficacy of a treat-and-extend regimen with ranibizumab in patients with neovascular age-related macular disease: an open-label 12-month extension to the CANTREAT study. Ophthalmologica. 2021;25:230–238. doi: 10.1159/000521517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ohji M, Lanzetta P, Korobelnik JF, et al. Efficacy and treatment burden of intravitreal aflibercept versus intravitreal ranibizumab treat-and-extend regimens at 2 years: network meta-analysis incorporating individual patient data meta-regression and matching-adjusted indirect comparison. Adv Ther. 2020;37(5):2184–2198. doi: 10.1007/s12325-020-01298-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin DF, Maguire MG, Ying GS, Grunwald JE, Fine SL, Jaffe GJ. Ranibizumab and bevacizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(20):1897–1908. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin DF, Maguire MG, Fine SL, et al. Ranibizumab and bevacizumab for treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: two-year results. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(7):1388–1398. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maguire MG, Martin DF, Ying GS, et al. Five-year outcomes with anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: the comparison of age-related macular degeneration treatments trials. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(8):1751–1761. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ueta T, Iriyama A, Francis J, et al. Development of typical age-related macular degeneration and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy in fellow eyes of Japanese patients with exudative age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146(1):96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Ranibizumab and pegaptanib for the treatment of age-related macular degeneration. 2008. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta155. Accesssed 11 Dec 2022.

- 37.Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (MHLW). [Regarding the revision of physician fee schedule in fiscal year 2022 (Reiwa-4 Nendo)]. 2022. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/0000188411_00037.html. (in Japanese). Accesssed 11 Feb 2023.

- 38.Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (MHLW). [Regarding the information on National Health Insurance Drug Price List and generic drugs]. 2022. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/topics/2022/04/tp20220401-01.html. (in Japanese). Accesssed 11 Feb 2023.

- 39.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. Basic survey on wage structure. 2021. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db-l/wage-structure.html. Accesssed 11 Feb 2023.

- 40.Hanemoto T, Hikichi Y, Kikuchi N, Kozawa T. The impact of different anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment regimens on reducing burden for caregivers and patients with wet age-related macular degeneration in a single-center real-world Japanese setting. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(12):e0189035-e. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hasegawa M, Komoto S, Shiroiwa T, Fukuda T. Formal implementation of cost-effectiveness evaluations in Japan: a unique health technology assessment system. Value Health. 2020;23(1):43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2019.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gillies MC, Walton R, Liong J, et al. Efficient capture of high-quality data on outcomes of treatment for macular diseases: the fight retinal blindness! Project Retina. 2014;34(1):188–195. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318296b271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lotery A, Griner R, Ferreira A, Milnes F, Dugel P. Real-world visual acuity outcomes between ranibizumab and aflibercept in treatment of neovascular AMD in a large US data set. Eye. 2017;31(12):1697–1706. doi: 10.1038/eye.2017.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoshino J, Matsumoto H, Morimoto M, Mukai R, Nakamura K, Akiyama H. Comparison of aflibercept and ranibizumab therapies using treat-and-extend regimen for retinal angiomatous proliferation. J Jpn Ophthalmol Soc. 2020;124(8):628–636. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoshino J, Matsumoto H, Kikuchi Y, et al. Comparison of 2-year outcomes of intravitreal aflibercept and ranibizumab therapy using treat-and-extend regimen for typical age-related macular degeneration with classic choroidal neovascularization. J Jpn Ophthalmol Soc. 2021;125(7):672–681. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Obeid A, Gao X, Ali FS, et al. Loss to follow-up among patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration who received intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor injections. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136(11):1251–1259. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.3578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gao X, Obeid A, Aderman CM, et al. Loss to follow-up after intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor injections in patients with diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmol Retina. 2019;3(3):230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bakri SJ, Karcher H, Andersen S, Souied EH. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment discontinuation and interval in neovascular age-related macular degeneration in the United States. Am J Ophthalmol. 2022;242:189–196. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2022.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article/as supplementary information files.