Abstract

African pygmy hedgehogs (Atelerix albiventris) are widely farmed in southern China and Japan for medicinal materials and as pets. However, little is known about the prevalence, zoonotic potential, and environmental burden of Cryptosporidium spp., Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Giardia duodenalis in these animals. In this study, 380 fecal samples were collected from farmed and pet African pygmy hedgehogs in Guangdong of China, and analyzed for these pathogens by PCR and DNA sequencing. Overall, the detection rates of Cryptosporidium spp., E. bieneusi and G. duodenalis were 35.5%, 70.0% and 0, respectively. By living condition, the highest detection rates of Cryptosporidium spp. (61.5%) and E. bieneusi (100.0%) were both obtained from animals kept in the cave, which could be due to the overcrowding and poor hygiene conditions. Two Cryptosporidium species were identified, including C. erinacei (n = 22) and Cryptosporidium horse genotype (n = 113). The C. erinacei isolates belonged to a new subtype family (XIIIb), which has been identified in a patient with cryptosporidiosis recently. The horse genotype isolates are of a known subtype VIbA13, which was previously identified in a pet store employee in care of hedgehogs with diarrhea. Eleven genotypes of the zoonotic Group 1 were identified in E. bieneusi, with the known genotype SCR05 previously detected in pet rabbits being dominant (235/266, 88.3%). In longitudinal monitoring of Cryptosporidium infection in 11 naturally infected African pygmy hedgehogs, the oocyst shedding intensity decreased gradually from the mean oocysts per gram of feces of ∼6 logs to ∼2 logs over 42 days. The high intensity and long duration of oocyst shedding could lead to heavy environmental contamination and increase the potential for zoonotic transmission of the pathogens. Results of the study suggest that zoonotic Cryptosporidium spp. and E. bieneusi are common in farmed and pet African pygmy hedgehogs. Hygiene and One Health measures should be implemented by pet owners and farmers to prevent zoonotic transmission and environmental contamination of Cryptosporidium spp. and E. bieneusi.

Keywords: Cryptosporidium, Enterocytozoon bieneusi, African pygmy hedgehogs, Zoonosis, One health

Highlights

-

•

Cryptosporidium spp. and Enterocytozoon bieneusi are common in farmed and pet hedgehogs.

-

•

The two Cryptosporidium species identified are known human pathogens.

-

•

The 11 E. bieneusi genotypes detected have potential for cross-species transmission.

-

•

Cryptosporidium oocysts excreted from hedgehogs could contaminate environment heavily.

-

•

One Health measures should be developed to control the transmission of zoonotic pathogens from hedgehogs.

1. Introduction

Cryptosporidium spp., Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Giardia duodenalis are common enteric pathogens in humans and animals. They usually cause diarrhea and other gastrointestinal symptoms, especially in immunocompromised person [[1], [2], [3]]. Susceptible hosts acquire infections of these pathogens through direct contact with infected individuals and consumption of contaminated water and food [[4], [5], [6]]. The Cryptosporidium oocysts, E. bieneusi spores and Giardia cysts excreted from the hosts can survive in soil and water for a long period, posing a major threat to public health.

To date, 45 Cryptosporidium species and >120 genotypes have been reported [7,8]. Most of Cryptosporidium species are host-specific, except a few zoonotic ones [9]. These species can be further subtyped based on nucleotide sequence polymorphism of the 60 kDa glycoprotein (gp60) gene, and isolates frequently differ in host range and virulence at the subtype family level [10]. Similarly, E. bieneusi contains >500 ITS genotypes belonging to 11 phylogenetic groups (1–11) with different levels of host specificity. Among them, Group 1 is the largest group and contains most of the zoonotic genotypes, while the other groups are mostly host-adapted [11]. Giardia duodenalis also consists of several well-established genotypes known as assemblages, including the zoonotic assemblages A and B in humans and a broad range of animals and other host-adapted assemblages in specific groups of mammals [12].

Hedgehogs are natural hosts of these three enteric pathogens. Cryptosporidium parvum, C. hominis and C. erinacei were identified in wild European hedgehogs (Erinaceus europaeus) in several studies conducted in Germany, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and Czech Republic [[13], [14], [15], [16]]. The former two Cryptosporidium species are major human pathogens. In contrast, C. erinacei is hedgehog-adapted, but has been occasionally found in horses and humans [[17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22]]. In China and Japan, a few hedgehogs examined were infected with C. ubiquitum and Cryptosporidium horse genotype [[23], [24], [25]]. The only report on E. bieneusi in hedgehogs showed that 9.8% (4/41) of wild hedgehogs (Erinaceus amurensis) were positive for E. bieneusi in Hubei, China. The genotypes of E. bieneusi identified were EA1-EA4 of the zoonotic Group 1 [26]. The two studies on G. duodenalis in hedgehogs were both conducted in wild hedgehogs in European; in one study, 10/90 wild hedgehogs were positive for the zoonotic assemblage A [13,27].

Hedgehogs are now widely farmed in China, Japan and some other countries for the supply of medicinal materials and as pets. The close contact between hedgehogs and farmers/pet owners could facilitate zoonotic transmission of pathogens. In this study, we examined the prevalence and genetic identity of Cryptosporidium spp., E. bieneusi and G. duodenalis in farmed and pet African pygmy hedgehogs (Atelerix albiventris) in Guangdong, China. In addition, we examined the oocyst shedding pattern of natural Cryptosporidium infection in these animals. The data generated should be useful in assessing the zoonotic potential and environmental contamination of the three pathogens in the context of One Health.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Ethics statement

The research protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the South China Agricultural University. Animal samples were collected following the guidelines of the Chinese Laboratory Animal Administration established in 2017. Fecal pellets were collected from cages with minimum handling of the sampled animals. Permissions were obtained from the animal owners before the fecal sample collection.

2.2. Sample collection

From January to September 2021, 380 fresh fecal samples were collected from farmed and pet African pygmy hedgehogs in Guangdong, China (Table 1). The animals were bred in different conditions, including a cave, a farm, and four pet shops. In the cave, about 100 animals over 5 months old were kept free ranging in a limited area, and the hygiene and ventilation conditions were poor. Thirteen fecal samples were collected from separated sites in the cave. On the farm, 2–4 animals of the same age were kept in 100 × 50 × 50 cm uncovered plastic cages under good sanitation and ventilation conditions. The animals were unable to contact others in neighboring cages. Only one fecal sample was collected from each cage. Altogether, 329 fecal samples were collected from animals of 0–2 (n = 115), 3–4 (n = 95) and ≥ 5 months (n = 119) on the farm. In pet shop 1, there were two 100 × 50 × 50 cm plastic cages without cover for housing hedgehogs. About 15–20 animals of 0–2 months were kept in each cage, and 22 fresh fecal samples were randomly collected from the two cages. In pet shops 2–4, there was only one 50 × 25 × 25 cm uncovered glass cage housing 4–10 animals of 0–2 months, and 3, 6 and 7 fresh fecal samples were collected from shops 2, 3 and 4, respectively. The ventilation and hygiene conditions in pet shops were better than those in the cave but not as good as those on the farm.

Table 1.

Distribution of Cryptosporidium spp. and Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes in farmed and pet African pygmy hedgehogs in Guangdong by living condition.

| Living condition | Age (months) | Sample size | No. positive for Cryptosporidium (%) | Cryptosporidium spp. (n) | No. positive for E. bieneusi (%) |

E. bieneusi genotypes (n) | No. of co-infection (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pet shops | 0–2 | 38 | 18 (47.4) | Horse genotype (18) | 37 (97.4) | SCR05 (36) | 18 (47.4) |

| Farm | 0–2 | 115 | 66 (57.4) | Horse genotype (55), C. erinacei (11) |

85 (73.9) | SCR05 (77), GDH01 (4), GDH02 (1) | 48 (41.7) |

| 3–4 | 95 | 23 (24.2) | Horse genotype (19), C. erinacei (4) |

64 (67.4) | SCR05 (53), GDH01 (2), GDH02 (2), GDH03 (1), GDH04 (1), GDH05 (1), GDH06 (1), GDH10 (1), Mixed infection (2) |

18 (18.9) | |

| ≥5 | 119 | 20 (16.8) | Horse genotype (18), C. erinacei (2) |

67 (56.3) | SCR05 (57), GDH01 (2), GDH07 (1), GDH08 (1), GDH09 (1), Mixed infection (4) | 12 (10.1) | |

| Subtotal | 329 | 109 (33.1) | Horse genotype (92), C. erinacei (17) |

216 (65.7) | SCR05 (187), GDH01 (8), GDH02 (3), GDH03 (1), GDH04 (1), GDH05 (1), GDH06 (1), GDH07 (1), GDH08 (1), GDH09 (1), GDH10 (1), Mixed infection (6) |

78 (23.7) | |

| Cave | ≥5 | 13 | 8 (61.5) |

C. erinacei (5), Horse genotype (3) |

13 (100.0) | SCR05 (12), GDH01 (1) | 8 (61.5) |

| Total | 380 | 135 (35.5) | Horse genotype (113), C. erinacei (22) | 266 (70.0) | SCR05 (235), GDH01 (9), GDH02 (3), GDH03 (1), GDH04 (1), GDH05 (1), GDH06 (1), GDH07 (1), GDH08 (1), GDH09 (1), GDH10 (1), Mixed infection (6) |

104 (27.4) |

The fecal samples collected were preserved in 2.5% potassium dichromate and stored at 4 °C until DNA extraction within one month.

2.3. DNA extraction and PCR analysis

Fecal samples were washed twice with distilled water by centrifugation at 2000 ×g for 10 min to remove potassium dichromate. Genomic DNA was extracted from approximately 200 mg of washed fecal material from each sample using the Fast DNA Spin Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA).

Cryptosporidium spp. were detected and genotyped using nested PCR and sequence analysis of the small subunit (SSU) rRNA gene [28]. The PCR-positive samples were further subtyped using sequence analysis of the gp60 gene [29]. Enterocytozoon bieneusi was detected and genotyped using nested PCR and sequence analysis of a 392-bp fragment of the rRNA gene containing the entire ITS sequence [30]. Giardia duodenalis was detected using nested PCR and sequence analysis of partial β-giardin (bg) gene [31]. Each sample was analyzed by PCR at each genetic locus with two technical replicates. The secondary PCR products generated from the samples were examined by electrophoresis in 1.5% agarose gels.

2.4. Sequence and phylogenetic analyses

Positive secondary PCR products were sequenced bi-directionally on an ABI 3730 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) at Sangon Biotech Corp. (Shanghai, China). The nucleotide sequences generated were assembled using ChromasPro 2.1.6 (Technelysium Pty Ltd., Brisbane, Australia, http://technelysium.com.au/ChromasPro.html), edited using BioEdit 7.1.3 (Bioedit Ltd., Manchester, UK, http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/BioEdit/bioedit.html), and aligned with reference sequences downloaded from GenBank using ClustalX 1.81 (http://www.clustal.org/). To assess the phylogenetic relationships among species, genotypes and subtypes of the pathogens, maximum likelihood (ML) trees were constructed using MEGA 7.0.14 (http://www.megasoftware.net/) based on substitution rates calculated using the General Time Reversible model. The robustness of cluster formations was assessed with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Representative nucleotide sequences generated in the study were submitted to GenBank under accession numbers OP564152, OP564153, OP574239–OP574249, and OP574348–OP574352.

2.5. Measurement of oocyst shedding intensity

The intensity of oocyst shedding in Cryptosporidium-positive fecal samples was measured using 18S-LC2 qPCR [32]. The Cq (quantitation cycle) values generated were used to estimate the number of oocysts per gram of feces (OPG) against a standard curve generated from Cryptosporidium-negative fecal samples spiked with 102, 103, 104, 105 and 106 oocysts of C. parvum IOWA isolate (Waterborne, Inc., New Orleans, USA).

2.6. Statistical analysis

The Chi-square test in the software SPSS V.20.0 (IBM Corp., New York, NY, USA) was used to assess the significance of differences in prevalence of pathogens among living conditions and age groups. The Student's t-test was used to compare the intensity of oocyst shedding among Cryptosporidium species. Differences were considered significant at P ≤ 0.05.

2.7. Longitudinal monitoring of natural Cryptosporidium infection

To evaluate the oocyst shedding pattern of Cryptosporidium spp. in naturally infected African pygmy hedgehogs, 11 hedgehogs of 0–2 months were purchased from pet shop 1 and housed individually in plastic cages. In the first three days, fecal samples of the animals were collected every day and examined for Cryptosporidium spp. by PCR analysis of the SSU rRNA gene [28]. The positive samples were further subtyped by PCR and sequence analysis of the gp60 gene. Afterwards, the animals were sampled every three days for measurements of oocyst shedding intensity using 18S-LC2 qPCR [32].

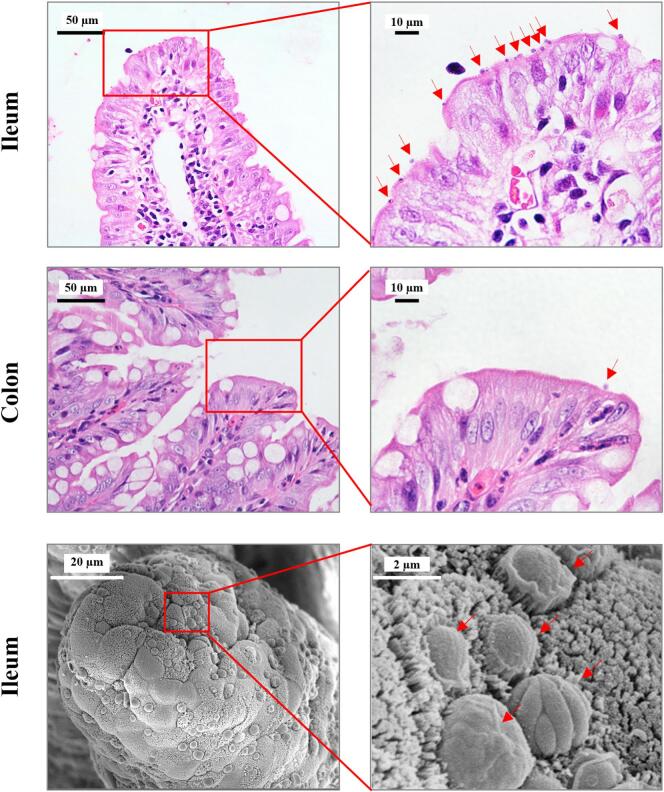

Two animals (#5 and #9) positive for Cryptosporidium horse genotype were euthanized on Day 5 for histopathological examination. The ileum and colon tissues harvested were sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin staining (HE) for histological examination on a BX53 microscope (Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan). In addition, the ileum tissues were prefixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide (OsO4), and examined for the infection intensity using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) on an EVO MA 15/LS 15 (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany).

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp., E. bieneusi and G. duodenalis in African pygmy hedgehogs

Of the 380 fecal samples analyzed, 135 (35.5%) were positive for Cryptosporidium spp. The detection rate varied among the living conditions. The highest detection rate was obtained from animals in the cave (61.5%, 8/13), followed by those in pet shops (47.4%, 18/38) and on the farm (33.1%, 109/329) (Table 1). The difference in detection rates between the cave and farm was significant (χ2 = 4.48, P = 0.034). By age, the detection rate of Cryptosporidium spp. in animals of 0–2 months (54.9%, 84/153) was significantly higher than those of 3–4 months (24.2%, 23/95; χ2 = 22.51, P < 0.001) and ≥ 5 months (21.2%, 28/132; χ2 = 33.72, P < 0.001) (Table 2). A similar situation was observed on the farm, with the detection rate in animals of 0–2 months (57.4%, 66/115) being significantly higher than those in animals of 3–4 months (24.2%, 23/95; χ2 = 22.51, P < 0.001) and ≥ 5 months (16.8%, 20/119; χ2 = 33.72, P < 0.001) (Table 1).

Table 2.

Distribution of Cryptosporidium spp. and Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes in farmed and pet African pygmy hedgehogs in Guangdong by age.

| Age (months) | Sample size | No. positive for Cryptosporidium (%) |

Cryptosporidium spp. (n) |

No. positive for E. bieneusi (%) |

E. bieneusi genotypes (n) | No. of co-infection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–2 | 153 | 84 (54.9) | Horse genotype (73), C. erinacei (11) |

122 (79.7) | SCR05 (113), GDH01 (4), GDH02 (1) | 66 (43.1) |

| 3–4 | 95 | 23 (24.2) | Horse genotype (19), C. erinacei (4) |

64 (67.4) | SCR05 (53), GDH01 (2), GDH02 (2), GDH03 (1), GDH04 (1), GDH05 (1), GDH06 (1), GDH10 (1), Mixed infection (2) | 18 (18.9) |

| ≥5 | 132 | 28 (21.2) | Horse genotype (21), C. erinacei (7) | 80 (60.6) | SCR05 (69), GDH01 (3), GDH07 (1), GDH08 (1), GDH09 (1), Mixed infection (4) | 20 (15.2) |

| Total | 380 | 135 (35.5) | Horse genotype (113), C. erinacei (22) | 266 (70.0) | SCR05 (235), GDH01 (9), GDH02 (3), GDH03 (1), GDH04 (1), GDH05 (1), GDH06 (1), GDH07 (1), GDH08 (1), GDH09 (1), GDH10 (1), Mixed infection (6) |

104 (27.4) |

Enterocytozoon bieneusi was detected in 266 of the 380 (70.0%) fecal samples. The detection rates of E. bieneusi in animals in the cave (100.00%, 13/13; χ2 = 6.67, P = 0.010) and pet shops (97.4%, 37/38; χ2 = 16.00, P < 0.001) were both significantly higher than that on the farm (65.7%, 216/329) (Table 1). By age, the detection rate of E. bieneusi in animals of 0–2 months (79.7%, 122/153) was significantly higher than those of 3–4 months (67.4%, 64/95; χ2 = 4.78, P = 0.029) and ≥ 5 months (60.6%, 80/132; χ2 = 1.08, P < 0.001) (Table 2). On the farm, the detection of E. bieneusi in animals also varied among age groups. The highest detection rate was obtained in animals of 0–2 months (73.9%, 85/115), followed by those of 3–4 months (67.4%, 64/95) and ≥ 5 months (56.3%, 67/119) (Table 1). However, only the difference between animals of 0–2 months and ≥ 5 months was significant (χ2 = 7.97, P = 0.005).

Initially, 176 of the 380 fecal samples were examined for G. duodenalis using bg PCR, including those collected from the farm (n = 132), pet shops (n = 38) and the cave (n = 6). They were from animals of all three age groups, including 0–2 months (n = 87), 3–4 months (n = 61) and ≥ 5 months (n = 28). However, none of the samples were positive for G. duodenalis. Therefore, the remaining 204 samples were not examined for this pathogen.

3.2. Distribution of Cryptosporidium species and subtypes

All 135 Cryptosporidium-positive samples were genotyped successfully by sequence analysis of the SSU rRNA PCR products. Two species were identified, including C. erinacei (n = 22) and Cryptosporidium horse genotype (n = 113). The SSU rRNA sequences of C. erinacei isolates identified were identical, and had a G to A single nucleotide substitution (SNP) compared with the reference sequence KF612324 from wild hedgehogs in Czech Republic [17]. The SSU rRNA sequences of Cryptosporidium horse genotype isolates obtained were identical to the reference sequences MK775041 from horses in China and FJ435962 from a pet store employee in the United States [33,34]. These two species were both present in the cave and on the farm. However, the dominant species in the cave and on the farm was C. erinacei (62.5%, 5/8) and Cryptosporidium horse genotype (84.4%, 92/109), respectively (Table 1). In contrast, Cryptosporidium horse genotype was the only species identified in the four pet shops examined. In addition, Cryptosporidium horse genotype was dominant in each of the three age groups (Table 2).

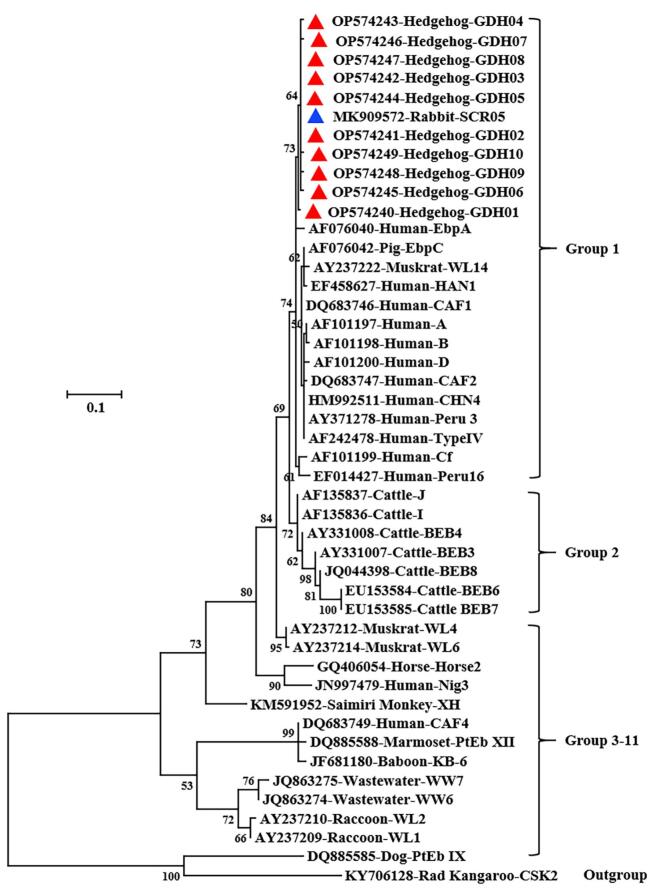

Of the 22 C. erinacei isolates, 16 were subtyped successfully at the gp60 locus, which generated identical gp60 sequences. However, the gp60 sequences obtained were significantly different from those of the known C. erinacei XIIIa subtype family (GenBank No. KU852737, GQ259140 and GQ214081), thus was named as a new subtype family XIIIb. The subtype identified was XIIIbA18G1R5. In phylogenetic analysis, the new gp60 subtype of C. erinacei identified in the study nevertheless formed a cluster with the XIIIa subtype family (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic relationship among some Cryptosporidium subtypes based on the maximum likelihood analysis of the nucleotide sequences of the 60 kDa glycoprotein gene. Bootstrap values >50% from 1000 replicates are shown on the branches. Known and novel subtypes identified in this study are indicated with blue and red triangles, respectively. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Of the 113 Cryptosporidium horse genotype isolates, 81 were subtyped successfully at the gp60 locus. They had 0–4 SNPs compared with the sequence of a subtype VIbA13 (GenBank No. FJ435961) obtained from a pet store employee before [34].

3.3. Differences in oocyst shedding intensity between C. erinacei and Cryptosporidium horse genotype

The intensity of oocyst shedding in Cryptosporidium-positive samples was measured using 18S-LC2 qPCR. The average OPG of C. erinacei-positive samples was 818,052 (n = 22), which was higher than that of Cryptosporidium horse genotype-positive samples (216,918, n = 113) (P = 0.058).

3.4. Distribution of E. bieneusi genotypes

Eleven genotypes were identified among the 266 E. bieneusi-positive samples, including a known genotype SCR05 and 10 novel genotypes named as GDH01–GDH10. Compared with the reference sequence MK909572, GDH05 had two nucleotide deletions, while the other nine novel genotypes had one SNP at different positions. In phylogenetic analysis of ITS sequences, all novel genotypes clustered together with SCR05 and belonged to zoonotic Group 1 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic relationship among some Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes based on the maximum-likelihood analysis of nucleotide sequences of the internal transcribed spacer of the rRNA gene. Bootstrap values >50% from 1000 replicates are shown on the branches. Known and novel genotypes identified in this study are indicated with blue and red triangles, respectively. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Of the 11 genotypes, SCR05 was dominant (235/266, 88.3%), followed by GDH01 (9/266, 3.4%), GDH02 (3/266, 0.8%) and GDH03-GDH10 (1/266 for each genotype, 0.4%) (Table 1). Mixed infection indicated by unreadable ITS sequence was found in six samples. The genetic diversity of E. bieneusi varied among living conditions and age groups. Higher genetic diversity was observed in E. bieneusi isolates from animals on the farm and of 3–4 months, with 11 and 8 genotypes detected, respectively (Table 1, Table 2). In contrast, limited genotypes were identified in E. bieneusi isolates from animals in pet shops (one genotype) and of 0–2 months (three genotypes) (Table 1, Table 2).

3.5. Co-infection of Cryptosporidium spp. and E. bieneusi

Co-infection with Cryptosporidium spp. and E. bieneusi was detected in 104 samples. The co-infection rate in animals on the farm (23.7%, 78/329) was significantly lower than those in cave (61.5%, 8/13; χ2 = 9.51, P = 0.002) and pet shops (47.4%, 18/38; χ2 = 9.87, P = 0.002). In addition, co-infection was significantly more often in animals of 0–2 months (43.1%, 66/153) than in those of 3–4 months (18.9%, 18/95; χ2 = 15.31, P < 0.001) and ≥ 5 months (15.2%, 20/132; χ2 = 26.34, P < 0.001).

3.6. Oocyst shedding pattern in naturally infected hedgehogs

The analysis of fecal samples revealed that the 11 African pygmy hedgehogs followed longitudinally were all positive for Cryptosporidium horse genotype, with three animals (#3, #7 and #8) having co-infections with C. erinacei. Cryptosporidium horse genotype and C. erinacei identified belonged to subtypes VIbA13 and XIIIbA18G1R5, respectively. Over 42 days of observations, the oocyst shedding intensity in the animals decreased gradually from the initial mean OPG values of nearly 6 logs to around 2 logs (Fig. 3). On Day 42, two of the animals were still positive for Cryptosporidium in nested PCR analysis. Diarrhea was observed in three animals (#2, #6 and #7) on Day 25 and one animal (#7) on Day 31.

Fig. 3.

Oocyst shedding pattern in African pygmy hedgehogs (n = 11) naturally infected with Cryptosporidium spp. On Day 5, two hedgehogs were euthanized for histological examinations.

Histological examination of two Cryptosporidium horse genotype-infected hedgehogs revealed the presence of parasites in the ileum and colon, with a much higher parasite burden in the former (Fig. 4). However, no obvious histopathological changes were observed in the ileum, and the villi remained intact. Under SEM, abundant parasites of various developmental stages were observed on the surface of the ileum. The microvilli around the parasites were sparser and longer than those on uninfected cells (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Pathology of the terminal ileum and colon of African pygmy hedgehogs infected with Cryptosporidium horse genotype. The upper and middle panels are the hematoxylin and eosin microscopy images of the ileum and colon, respectively. The lower panel shows the ileum under scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Parasites on the brush border are indicated with arrows. In the SEM images, microvilli around parasites are sparser and more elongated compared with those on uninfected cells, and diverse parasite stages of different sizes and morphology are seen.

4. Discussion

Results of the study indicate that Cryptosporidium spp. and E. bieneusi are common in farmed and pet African pygmy hedgehogs in Guangdong, China. The detection rate of Cryptosporidium spp. (35.5%, 135/380) in the present study is much higher than those reported in wild European hedgehogs in the Netherlands (8.9%, 8/90) and the United Kingdom (8.1%, 90/111) [13,15]. Similarly, the detection rate of E. bieneusi (70.0%, 266/380) here is also much higher than that reported in wild Amur hedgehogs (9.8%, 4/41) in Hubei, China [26]. The common occurrence of these two pathogens in farmed and pet African pygmy hedgehogs could be due to the high intensity of animal farming, which was observed in some other farmed exotic animals such as fur animals, bamboo rats, and macaque monkeys [35]. In addition, the poor hygiene is probably a major factor contributing to the high prevalence of the pathogens. In general, the detection rates of Cryptosporidium spp. (54.9%) and E. bieneusi (79.7%) in animals of 0–2 months were significantly higher than 3–4 months (24.2% and 67.4%) and ≥ 5 months (21.2% and 60.6%), indicating that young animals are more susceptible to these two pathogens. This is similar to the observations of Cryptosporidium infections in wild hedgehogs and other farmed exotic animals [14,16,35]. However, the animals in the cave were over 5 months in age, the detection rates of Cryptosporidium spp. and E. bieneusi (61.5% and 100%) were higher than those in pet shops (47.4% and 97.4%) and on the farm (33.1 and 65.7%). This is probably due to poor hygiene condition and overcrowding of animals in the cave, which would greatly facilitate the transmission of enteric pathogens among animals.

The distribution of Cryptosporidium species/subtypes in farmed and pet African pygmy hedgehogs is different from that in wild hedgehogs. As reported previously, C. parvum was the most common Cryptosporidium species in wild hedgehogs, followed by C. erinacei; C. hominis was occasionally seen [13,15,16]. However, the two Cryptosporidium species identified in the present study were C. erinacei and Cryptosporidium horse genotype, with the latter being dominant. The C. erinacei isolates belonged to a new subtype XIIIbA18G1R5, which is different from those of the subtype family XIIIa obtained from wild hedgehogs and humans [17,21]. Recently, another new subtype XIIIbA23G1R4 was identified in a Denmark male who suffered from gastroenteritis that lasted several weeks [36]. Cryptosporidium horse genotype is common in equine animals, and has never been found in wild hedgehogs before [33,37,38]. Reasons for the difference in the transmission of Cryptosporidium spp. between farmed and wild hedgehogs are currently unknown. The hosts involved could be one contributing factor, as studies in Europe were exclusively done with wild European hedgehogs (Erinaceus europaeus), while those in China and Japan were done with pet African pygmy hedgehogs (Atelerix albiventris). In addition, the intensive animal farming of African pygmy hedgehogs could have also facilitated the dispersal of Cryptosporidium horse genotype.

Cryptosporidium horse genotype apparently has a host range broader than believed. The species is very common in equine animals [33,37,38]. Recently, it has been identified in a few pet hedgehogs, wild squirrels and humans [20,24,25,34,39]. In this study, 29.7% (113/380) of African pygmy hedgehogs were positive for Cryptosporidium horse genotype. The high average OPG (216,918) and long oocyst shedding duration (>42 days) further confirm that African pygmy hedgehog is a natural host of Cryptosporidium horse genotype.

Cryptosporidium horse genotype is probably pathogenic in African pygmy hedgehogs. In the longitudinal follow-up of oocysts shedding in 11 hedgehogs naturally infected with the parasite in this study, three showed diarrheas on some days. Although no obvious pathological damages were observed in the ileum and colon of infected animals in routine histological examinations, changes in microvilli (becoming sparser and longer) around the parasites were detected at SEM examination of the brush border. In addition, a pet hedgehogs died of diarrhea-related dehydration was reportedly transmitted Cryptosporidium horse genotype to a care-giver [34]. Therefore, Cryptosporidium horse genotype could potentially affect nutrient absorption, contributing to the occurrence of diarrhea in infected animals.

The Cryptosporidium species identified in farmed and pet African pygmy hedgehogs are known human pathogens. The dominant Cryptosporidium species identified in the study, Cryptosporidium horse genotype, has been detected in a few human cases of clinical cryptosporidiosis, including a pet shop employee who had contact with diarrheal hedgehogs and a patient with cryptosporidiosis [20,34,40]. In addition, the gp60 subtype of Cryptosporidium horse genotype identified in this study has only 0–4 SNPs compared with that identified in the pet store employee. Similarly, C. erinacei has been reported in some human cryptosporidiosis cases in France, Sweden, Greece, Czech Republic, and New Zealand [[19], [20], [21], [22],36]. Moreover, a recent human infection was caused by C. erinacei subtype family XIIIb, which was identified in the present study. Therefore, Cryptosporidium horse genotype and C. erinacei identified in African pygmy hedgehogs are probably zoonotic. Similarly, E. bieneusi in farmed and pet African pygmy hedgehogs have the potential for cross-species transmission. The 11 E. bieneusi ITS genotypes detected all belong to Group 1, which contains genotypes responsible for most zoonotic or cross-species transmission of E. bieneusi. The dominant E. bieneusi genotype, SCR05, has been detected in pet rabbits in Sichuan, China [41]. The remaining 10 new genotypes have only 1–2 SNPs compared with SCR05. Therefore, these genotypes could have the capability to infect humans and other farm animals.

Cryptosporidium oocysts shed by farmed and pet African pygmy hedgehogs can possibly result in heavy environmental contamination. As indicated by the study, in contrast to wild hedgehogs, human-pathogenic Cryptosporidium species are very common in farmed and pet African pygmy hedgehogs. The average intensity of oocyst shedding in infected animals is over 106 OPG. In addition, the oocyst shedding in the naturally infected hedgehogs can last as long as 42 days. Thus, infected hedgehogs could excrete a large number of oocysts into the environment, and the farm waste and water near the farms could be heavily contaminated. The extremely high detection rate of Cryptosporidium spp. in hedgehogs overcrowded in the cave further supports the role of environmental contamination in the transmission of Cryptosporidium spp. Because of the remarkable resistance to diverse environmental factors, the long survival of a large number of Cryptosporidium oocysts in the environment would greatly increase the transmission of the pathogens and threaten the public health [42].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, Cryptosporidium spp. and E. bieneusi are common in farmed and pet African pygmy hedgehogs in Guangdong, China. The two Cryptosporidium species detected in the study, C. erinacei and Cryptosporidium horse genotype, are well-known human pathogens, indicating these animals may be potential reservoirs of zoonotic Cryptosporidium spp. The 11 E. bieneusi genotypes detected belong to zoonotic Group 1, and the dominant genotype SCR05 was observed in pet rabbits before. Thus, the E. bieneusi genotypes also have the potential for cross-species transmission. In addition, the large number of Cryptosporidium oocysts excreted from infected hedgehogs could lead to heavy environmental contamination and increase the potential for zoonotic transmission of the pathogens. Therefore, farmers should be educated about the zoonotic potential of pathogens in hedgehogs. To better understand the transmission of Cryptosporidium horse genotype and C. erinacei and formulate One Health approaches for their prevention and control, future molecular epidemiological studies should involve the sampling and characterization of pathogens in farmers, pet keepers as well as pet animals living in the same habitat.

Funding

This research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. U21A20258 and No. 31972697), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (No. 2019A1515011979), Natural Science Foundation of Guangzhou City (No. 202201010140), Laboratory for Lingnan Modern Agriculture Project (No. NT2021007), 111 Project (No. D20008), and Innovation Team Project of Guangdong University (No. 2019KCXTD001). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, preparation of the manuscript, or decision to submit the article for publication.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Xinan Meng: Data curation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Wenlun Chu: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Yongping Tang: Resources, Investigation, Validation. Weijian Wang: Formal analysis, Validation. Yuxin Chen: Resources, Investigation. Na Li: Formal analysis, Methodology. Yaoyu Feng: Methodology, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Lihua Xiao: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Yaqiong Guo: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no conflicting interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

We thank the owners and staff of the shops, cave and farm for their assistance in sample collection during this study.

Contributor Information

Xinan Meng, Email: mengxn@stu.scau.edu.cn.

Wenlun Chu, Email: wenlun_chu@163.com.

Yongping Tang, Email: yongpingtang202210@163.com.

Weijian Wang, Email: wjwang@stu.scau.edu.cn.

Yuxin Chen, Email: cyx_tn6@163.com.

Na Li, Email: nli@scau.edu.cn.

Yaoyu Feng, Email: yyfeng@scau.edu.cn.

Lihua Xiao, Email: lxiao1961@gmail.com.

Yaqiong Guo, Email: guoyq@scau.edu.cn.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Han B., Pan G., Weiss L.M. Microsporidiosis in humans. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2021;34(4) doi: 10.1128/CMR.00010-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Checkley W., White A.C., Jaganath D., Arrowood M.J., Chalmers R.M., Chen X., Fayer R., Griffiths J.K., Guerrant R.L., Hedstrom L., Huston C.D., Kotloff K.L., Kang G., Mead J.R., Miller M., Petri W.A., Priest J.W., Roos D.S., Striepen B., Thompson R.C.A., Ward H.D., Van Voorhis W.A., Xiao L., Zhu G., Houpt E.R. A review of the global burden, novel diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccine targets for Cryptosporidium. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2015;15(1):85–94. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70772-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodney D.A. Giardia duodenalis: biology and pathogenesis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2021;34(4) doi: 10.1128/CMR.00024-19. e00024–00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryan U., Hijjawi N., Feng Y., Xiao L. Giardia: an under-reported foodborne parasite. Int. J. Parasitol. 2019;49(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2018.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li W., Feng Y., Xiao L. Enterocytozoon bieneusi. Trends Parasitol. 2022;38(1):95–96. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2021.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zahedi A., Ryan U. Cryptosporidium - an update with an emphasis on foodborne and waterborne transmission. Res. Vet. Sci. 2020;132:500–512. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2020.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryan U.M., Feng Y., Fayer R., Xiao L. Taxonomy and molecular epidemiology of Cryptosporidium and Giardia – a 50 year perspective (1971–2021) Int. J. Parasitol. 2021;51(13):1099–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2021.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prediger J., Ježková J., Holubová N., Sak B., Konečný R., Rost M., McEvoy J., Rajský D., Kváč M. Cryptosporidium sciurinum n. sp. (Apicomplexa: Cryptosporidiidae) in Eurasian Red Squirrels (Sciurus vulgaris) Microorganisms. 2021;9(10):2050. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9102050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng Y., Ryan U.M., Xiao L. Genetic diversity and population structure of Cryptosporidium. Trends Parasitol. 2018;34(11):997–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2018.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feng Y., Xiao L. Molecular epidemiology of cryptosporidiosis in China. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:1701. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li W., Feng Y., Santin M. Host specificity of Enterocytozoon bieneusi and public health implications. Trends Parasitol. 2019;35(6):436–451. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2019.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai W., Ryan U., Xiao L., Feng Y. Zoonotic giardiasis: an update. Parasitol. Res. 2021;120(12):4199–4218. doi: 10.1007/s00436-021-07325-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krawczyk A.I., van Leeuwen A.D., Jacobs-Reitsma W., Wijnands L.M., Bouw E., Jahfari S., van Hoek A.H., van der Giessen J.W., Roelfsema J.H., Kroes M., Kleve J., Dullemont Y., Sprong H., de Bruin A. Presence of zoonotic agents in engorged ticks and hedgehog faeces from Erinaceus europaeus in (sub) urban areas. Parasit. Vectors. 2015;8:210. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-0814-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dyachenko V., Kuhnert Y., Schmaeschke R., Etzold M., Pantchev N., Daugschies A. Occurrence and molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. genotypes in European hedgehogs (Erinaceus europaeus L.) in Germany. Parasitology. 2010;137(2):205–216. doi: 10.1017/S0031182009991089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sangster L., Blake D.P., Robinson G., Hopkins T.C., Sa R.C., Cunningham A.A., Chalmers R.M., Lawson B. Detection and molecular characterisation of Cryptosporidium parvum in British European hedgehogs (Erinaceus europaeus) Vet. Parasitol. 2016;217:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofmannová L., Hauptman K., Huclová K., Květoňová D., Sak B., Kváč M. Cryptosporidium erinacei and C. parvum in a group of overwintering hedgehogs. Eur. J. Protistol. 2016;56:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ejop.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kváč M., Hofmannová L., Hlásková L., Květoňová D., Vítovec J., McEvoy J., Sak B. Cryptosporidium erinacei n. sp. (Apicomplexa: Cryptosporidiidae) in hedgehogs. Vet. Parasitol. 2014;201(1–2):9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2014.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laatamna A.E., Wagnerová P., Sak B., Květoňová D., Aissi M., Rost M., Kváč M. Equine cryptosporidial infection associated with Cryptosporidium hedgehog genotype in Algeria. Vet. Parasitol. 2013;197(1–2):350–353. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2013.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia R.J., Pita A.B., Velathanthiri N., French N.P., Hayman D.T.S. Species and genotypes causing human cryptosporidiosis in New Zealand. Parasitol. Res. 2020;119(7):2317–2326. doi: 10.1007/s00436-020-06729-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lebbad M., Winiecka-Krusnell J., Stensvold C.R., Beser J. High diversity of Cryptosporidium species and subtypes identified in cryptosporidiosis acquired in Sweden and abroad. Pathogens. 2021;10(5):523. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10050523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kváč M., Saková K., Kvĕtoňová D., Kicia M., Wesolowska M., McEvoy J., Sak B. Gastroenteritis caused by the Cryptosporidium hedgehog genotype in an immunocompetent man. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014;52(1):347–349. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02456-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Costa D., Razakandrainibe R., Valot S., Vannier M., Sautour M., Basmaciyan L., Gargala G., Viller V., Lemeteil D., Ballet J.J., C. French National Network on Surveillance of Human, Dalle F., Favennec L. Epidemiology of cryptosporidiosis in France from 2017 to 2019. Microorganisms. 2020;8(9) doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8091358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Q., Li L., Tao W., Jiang Y., Wan Q., Lin Y., Li W. Molecular investigation of Cryptosporidium in small caged pets in Northeast China: host specificity and zoonotic implications. Parasitol. Res. 2016;115(7):2905–2911. doi: 10.1007/s00436-016-5076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takaki Y., Takami Y., Watanabe T., Nakaya T., Murakoshi F. Molecular identification of Cryptosporidium isolates from ill exotic pet animals in Japan including a new subtype in Cryptosporidium fayeri. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Reports. 2020;21 doi: 10.1016/j.vprsr.2020.100430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abe N., Matsubara K. Molecular identification of Cryptosporidium isolates from exotic pet animals in Japan. Vet. Parasitol. 2015;209(3–4):254–257. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gong X., Xiao X., Gu X., Han H., Yu X. Detection of intestinal parasites and genetic characterization of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in hedgehogs from China. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2021;21(1):63–66. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2020.2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rasmussen S.L., Hallig J., van Wijk R.E., Petersen H.H. An investigation of endoparasites and the determinants of parasite infection in European hedgehogs (Erinaceus europaeus) from Denmark. Int. J. Parasitol.-Parasit. Wildl. 2021;16:217–227. doi: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2021.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xiao L., Escalante L., Yang C., Sulaiman I., Escalante A.A., Montali R.J., Fayer R., Lal A.A. Phylogenetic analysis of Cryptosporidium parasites based on the small-subunit rRNA gene locus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999;65(4):1578–1583. doi: 10.1128/AEM.65.4.1578-1583.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alves M., Xiao L., Sulaiman I., Lal A.A., Matos O., Antunes F. Subgenotype analysis of Cryptosporidium isolates from humans, cattle, and zoo ruminants in Portugal. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003;41(6):2744–2747. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.6.2744-2747.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sulaiman I.M., Fayer R., Lal A.A., Trout J.M., Schaefer F.W., Xiao L. Molecular characterization of microsporidia indicates that wild mammals harbor host-adapted Enterocytozoon spp. as well as human-pathogenic Enterocytozoon bieneusi. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003;69(8):4495–4501. doi: 10.1128/Aem.69.8.4495-4501.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caccio S.M., Beck R., Lalle M., Marinculic A., Pozio E. Multilocus genotyping of Giardia duodenalis reveals striking differences between assemblages A and B. Int. J. Parasitol. 2008;38(13):1523–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li N., Neumann N.F., Ruecker N., Alderisio K.A., Sturbaum G.D., Villegas E.N., Chalmers R., Monis P., Feng Y., Xiao L. Development and evaluation of three real-time PCR assays for genotyping and source tracking Cryptosporidium spp. in water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015;81(17):5845–5854. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01699-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li F., Su J., Chahan B., Guo Q., Wang T., Yu Z., Guo Y., Li N., Feng Y., Xiao L. Different distribution of Cryptosporidium species between horses and donkeys. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2019;75 doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2019.103954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiao L., Hlavsa M.C., Yoder J., Ewers C., Dearen T., Yang W., Nett R., Harris S., Brend S.M., Harris M., Onischuk L., Valderrama A.L., Cosgrove S., Xavier K., Hall N., Romero S., Young S., Johnston S.P., Arrowood M., Roy S., Beach M.J. Subtype analysis of Cryptosporidium specimens from sporadic cases in Colorado, Idaho, New Mexico, and Iowa in 2007: widespread occurrence of one Cryptosporidium hominis subtype and case history of an infection with the Cryptosporidium horse genotype. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009;47(9):3017–3020. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00226-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guo Y., Li N., Feng Y., Xiao L. Zoonotic parasites in farmed exotic animals in China: implications to public health. Int. J. Parasitol.-Parasit. Wildl. 2021;14:241–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2021.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larsen T.G., Kähler J., Lebbad M., Aftab H., Müller L., Ethelberg S., Xiao L., Stensvold C.R. First human infection with Cryptosporidium erinacei XIIIb – a case report from Denmark. Travel Med. Infect. Di. 2023;52 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2023.102552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang W., Zhang Z., Zhang Y., Zhao A., Jing B., Zhang L., Liu P., Qi M., Zhao W. Prevalence and genotypic identification of Cryptosporidium in free-ranging and farm-raised donkeys (Equus asinus asinus) in Xinjiang, China. Parasite. 2020;27:45. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2020042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Galuppi R., Piva S., Castagnetti C., Iacono E., Tanel S., Pallaver F., Fioravanti M.L., Zanoni R.G., Tampieri M.P., Caffara M. Epidemiological survey on Cryptosporidium in an equine perinatology unit. Vet. Parasitol. 2015;210(1–2):10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu J., Liu H., Jiang Y., Jing H., Cao J., Yin J., Li T., Sun Y., Shen Y., Wang X. Genotyping and subtyping of Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia duodenalis isolates from two wild rodent species in Gansu Province, China. Sci. Rep. 2022;12(1):12178. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-16196-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zajączkowska Ż., Brutovská A.B., Akutko K., McEvoy J., Sak B., Hendrich A.B., Łukianowski B., Kváč M., Kicia M. Horse-specific Cryptosporidium genotype in human with Crohn's disease and arthritis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022;28(6):1289–1291. doi: 10.3201/eid2806.220064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deng L., Chai Y., Xiang L., Wang W., Zhou Z., Liu H., Zhong Z., Fu H., Peng G. First identification and genotyping of Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Encephalitozoon spp. in pet rabbits in China. BMC Vet. Res. 2020;16(1):212. doi: 10.1186/s12917-020-02434-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Silva K.J.S., Sabogal-Paz L.P. Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia spp. (oo)cysts as target-organisms in sanitation and environmental monitoring: A review in microscopy-based viability assays. Water Res. 2021;189:116590. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.116590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.