This systematic review and meta-analysis assesses the lasting psychological morbidity among children, adolescents, and young adults with cancer.

Key Points

Question

What is the lifetime psychological morbidity of children, adolescent, and young adult patients with cancer (CYACs) and survivors?

Findings

This systematic review and meta-analysis including 52 studies found CYACs to experience an increased risk of depression, anxiety, and psychotic disorders after cancer remission compared with siblings and noncancer-matched controls. Depressive and anxiety disorders were particularly higher in cohorts older than 30 and 25 years, respectively; although CYACs overall were not at significantly increased risk of suicide mortality, certain subpopulations such as older adolescents were found to be at increased risk.

Meaning

Findings suggest that CYACs may experience an increased lifetime burden of depression, anxiety, and psychotic disorders.

Abstract

Importance

A cancer diagnosis and treatment may result in highly traumatic periods with lasting psychological consequences for children, adolescent, and young adult patients with cancer (CYACs). Early identification and management may prevent long-term psychological morbidity and suicide.

Objective

To analyze risk, severity, and risk factors for depression, anxiety, psychotic disorders, and suicide in CYACs and noncancer comparators.

Data Sources

Literature search of PubMed, MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and PubMed Central from January 1, 2000, to November 18, 2022.

Study Selection

Full-length articles in peer-reviewed journals that measured and reported risk and/or severity of depression, anxiety, psychotic disorders, and suicide mortality in CYACs and a noncancer comparator group.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines were followed with prospective PROSPERO registration.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Risk ratios (RRs) were used for dichotomous outcomes, and standardized mean differences (SMDs) were used for continuous outcomes. SMDs were defined as follows: 0.2, small; 0.5, medium; and 0.8, large. Sources of heterogeneity and risk factors were investigated using sensitivity, subgroup, and meta-regression analyses.

Results

From 7319 records, 52 studies were included. Meta-analyses revealed that CYACs were at increased lifetime risk of severe symptoms or a disorder of depression (RR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.29-1.92), anxiety (RR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.14-1.47), and psychotic disorders (RR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.36-1.80) relative to both matched controls and their siblings. Overall suicide mortality was not significantly elevated (RR, 1.63; 95% CI, 0.78-3.40). The mean severity of depression was found to be elevated in CYACs receiving treatment (SMD, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.13-0.74) and long-term survivors (SMD, 0.18; 95% CI, 0.02-0.33). The mean severity of anxiety was found to be elevated only during treatment (SMD, 0.16; 95% CI, 0.03-0.20).

Conclusions and Relevance

Findings of this systematic review and meta-analysis suggest that CYACs may experience lasting psychological burden long into survivorship. Timely identification, preventive efforts, and psycho-oncological intervention for psychological comorbidity are recommended.

Introduction

The incidence and global burden of cancer have steadily increased in the 21st century, and cancer remains one of the top causes of mortality. There are estimated to be over 300 000 cancer cases per year, with the most common cancers being leukemias, brain cancers, and lymphomas.1,2 With advancements in antineoplastic treatment, survival rates for pediatric cancers have risen over the years. This improved long-term prognosis has placed the spotlight on the management of complications in survivorship, such as growth delays, endocrinopathies, and neuropsychological impairment.3,4

It is well established that a diagnosis of cancer and subsequent treatment may be highly traumatizing for all age groups, especially for children in their formative years.5 This may stem from various dimensions, including the fear of death and pain from disease and treatment. Separate studies have suggested that childhood cancer survivors may be at an increased risk of not only physical complications related to cancer and its treatment6,7,8,9 but also psychological disorders.10

Various studies highlighted varying trajectories of psychological issues in childhood, adolescent, and young adults with cancer (CYACs), including both actively treated patients and survivors in remission, with findings ranging from inconclusive to significantly reduced or increased risks compared with age-matched comparators. To our knowledge, no systematic reviews to date have also analyzed the risk and severity of psychological disorders and symptoms over survivors’ lifetimes. Detecting those CYACs at a higher risk for prolonged distress by studying the risk and risk factors is crucial to facilitate appropriate and timely psychological interventions.

Methods

Protocol and Guidance

The study protocol was registered prospectively on PROSPERO. This systematic review is reported according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines.11

Data Sources and Search Strategy

A literature search was performed in PubMed, MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and PubMed Central on November 18, 2022. As cancer treatments and cancer survivorship care have progressed over the years, we only included studies published in the year 2000 or later so that findings may be more contextualized to modern care for CYACs. The search strategy combined search terms for pediatrics, childhood and young adults, cancer, depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, suicide, posttraumatic stress symptoms and disorder, and psychology. The search strategy was translated between each database. Examples of the search strategies for PubMed and Embase are available in eTable 1 in Supplement 1.

Study Selection: Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Two of 3 reviewers (A.R.Y.B.L., C.E.L., and C.E.Y.) independently screened the titles and abstracts, followed by full texts, of all studies for eligibility according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Discrepancies were resolved by adjudication by a third independent reviewer (C.S.H.H.). In our review, we considered 2 distinct groups of CYACs with a diagnosis of any solid or hematologic cancer. First, CYACs who are current patients with cancer who planned to receive or were currently receiving any form of antineoplastic therapy with curative intent no older than 25 years. Second, CYACs who are cancer survivors, who had a prior diagnosis of cancer when they were no older than 25 years and were in remission at the time of study. We performed preplanned analyses according to this dichotomy. The methods of reporting race and ethnicity were heterogenous across studies. Moreover, the majority of studies did not report detailed information of the breakdown of race and ethnicity of participants; therefore, these data were not included in this analysis.

We considered the outcomes of depression, anxiety, psychotic disorders (including schizophrenia), and suicide mortality. We included all psychotic disorders including schizophrenia defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition) and the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10). The diagnostic criteria or instrument used to assess each outcome was extracted. Only studies comparing outcomes in CYACs against controls without cancer were included. Controls without cancer could include those with a personal relation to the CYACs, such as their siblings, or those with no relation, such as matched controls. Subsequent subgroup analysis would be performed accounting for these differences. Studies were either observational or interventional. Interventional studies would be included if there were cohorts without intervention, such as in the control, and had psychological outcomes of interest in both patients with cancer and patients without cancer reported. Overall, no interventional studies meeting these criteria were identified in our search.

All data was extracted by 1 reviewer (A.R.Y.B.L.) with all extraction cross-checked by a second reviewer (C.E.L., C.E.Y., or J.L.). We planned to contact the corresponding authors of studies who may have been excluded due to missing or unreported data. No full-text studies were judged to be excluded on this basis.

Risk of Bias Assessment

To assess methodological quality and the risk of bias of included studies, the Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal checklist,12 which includes appraisal of the criteria for inclusion, measurement of condition, reporting of baseline characteristics, reporting of outcomes, and appropriateness of the statistical analysis (if any), was used.13 This appraisal was performed by 2 reviewers (A.R.Y.B.L. and C.E.L.) independently, with discrepancies resolved by the independent verdict of a senior reviewer (C.S.H.H.).

Statistical Analysis

We conducted all analyses on R, version 4.1.0 (R Project for Statistical Computing) using the meta and metafor packages. We considered a 2-sided P value <.05 as statistically significant. For continuous outcomes, in studies without SDs, CIs were converted to SDs. Studies were pooled for meta-analysis using standardized mean difference (SMD), using the escalc function in the metafor package, which automatically corrects the positive bias in the SMD (ie, in a Cohen d value) within the function, yielding a Hedges g value. We followed the guidelines by Cohen14 for the interpretation of the magnitude of the SMD in the social sciences with an SMD of 0.2 to 0.5 being small, 0.5 to 0.8 being medium, and greater than 0.8 being large. Sensitivity analysis was conducted using the random-effects, common-effects, and leave-one-out analyses, and identification and exclusion of potential outliers. For dichotomous outcomes, we performed meta-analyses for the relative risk of psychological disorders or symptoms (measured with risk ratios [RRs] in comparison to controls without cancer) and the absolute risk of psychological disorders or symptoms (measured as a proportion from 0%-100%). Between-study heterogeneity was represented by I2 and τ2 statistics. An I2 value of less than 30% indicated low heterogeneity between studies, 30% to 60% showed moderate heterogeneity, and greater than 60% indicated substantial heterogeneity.15

We anticipated, and observed, notable heterogeneity in the definitions and assessment of factors such as education, income, and family functioning, which may have limited statistical pooling. Thus, we extracted and used each study’s definition and analysis of the associations, such as of lower or higher education level and income, before using the synthesis without meta-analysis approach.16

We performed subgroup analyses and meta-regression to determine if key categorical and hierarchical variables influenced the results. We assessed for publication bias both qualitatively, via visual inspection for funnel plot asymmetry, and quantitatively, using the Egger test, with sensitivity analysis using the trim-and-fill method (R0 estimator, fixed random-effects models) to reestimate the pooled effect size after imputing potentially missing studies.17,18

Results

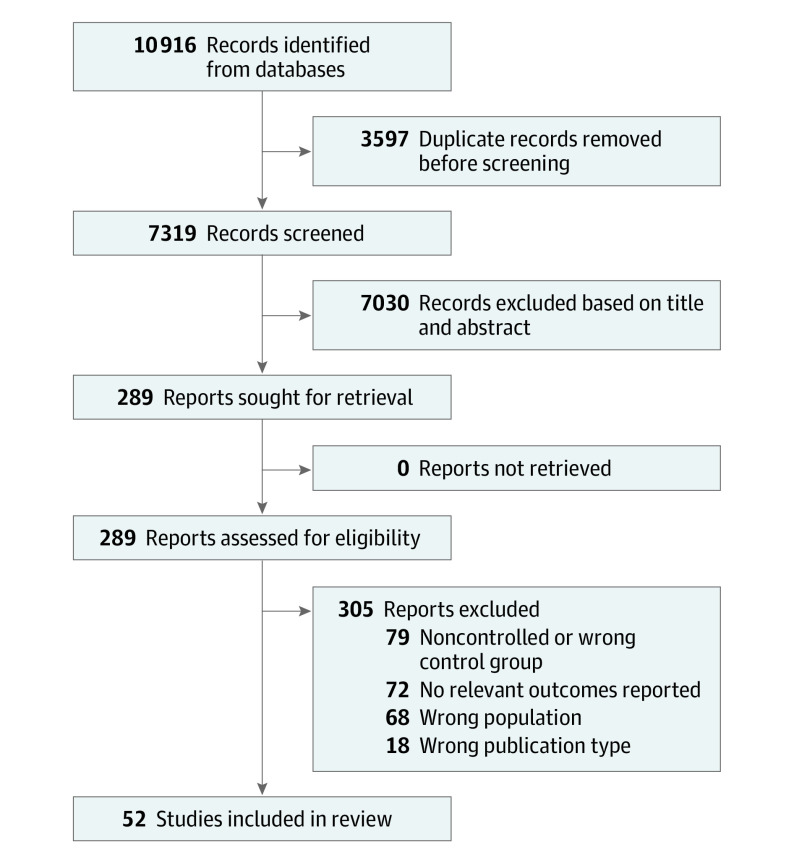

From 7319 results (Figure 1), we included a total of 52 studies reporting psychiatric disorders and psychological symptoms of depression, anxiety, psychotic disorders (including schizophrenia), and suicide mortality in CYACs compared with controls without cancer (eTable 2 in Supplement 1).5,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69 Most studies recruited healthy, age-matched comparators as a control group, whereas 13 studies23,25,26,27,29,30,31,50,53,54,55,69 recruited siblings and 3 studies21,46,47 recruited parents or caregivers of patients with cancer.

Figure 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) Flowchart.

Prevalence and Risk of Depressive Disorders and Severe Depression Symptoms

Meta-analyses were performed to evaluate the risk of developing severe depression or a depressive disorder and the mean severity of depressive symptoms in CYACs.5,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61 The specific scales used to measure depressive symptomatology are presented in eTable 3 in Supplement 1.

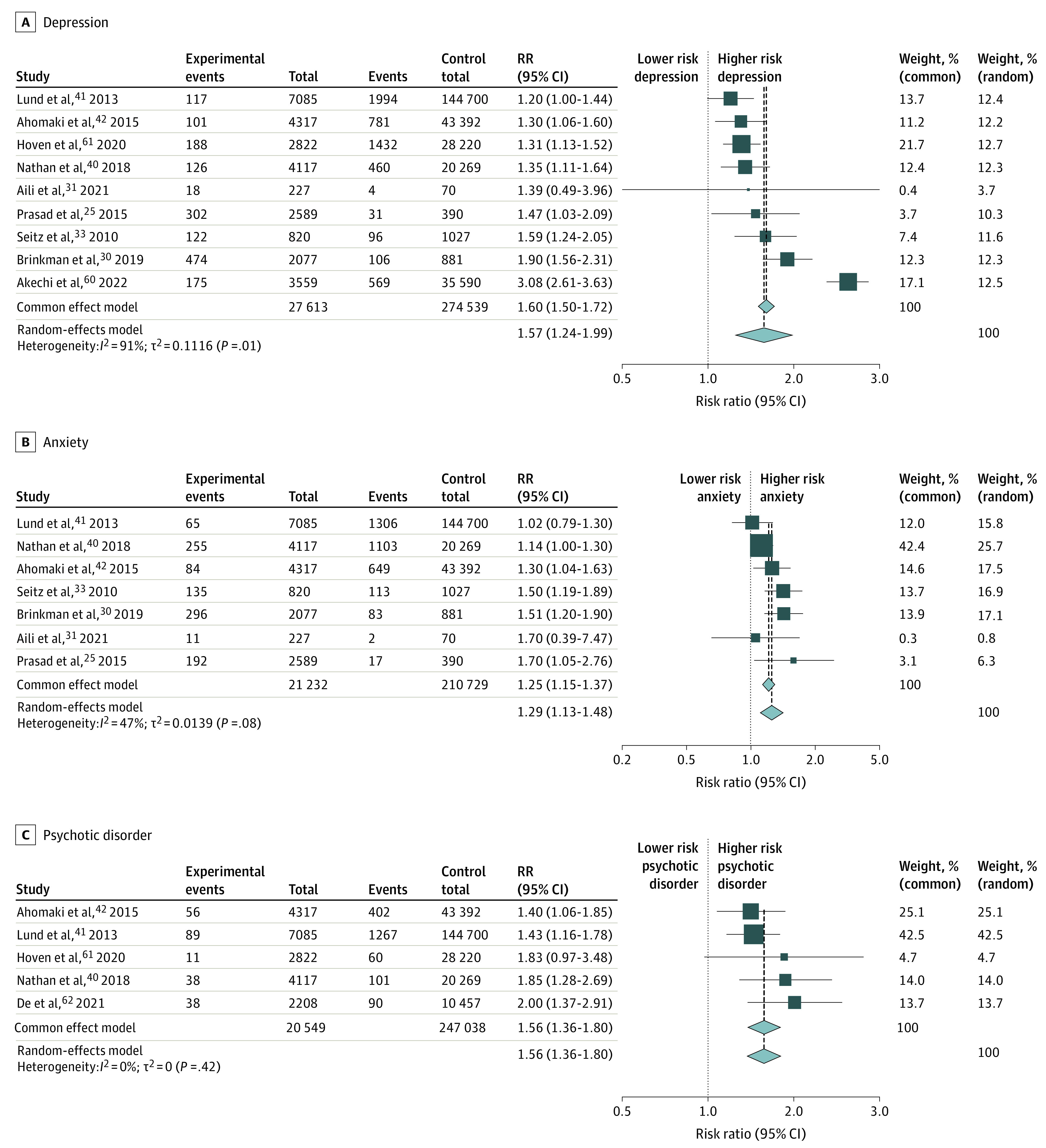

Meta-analysis of 27 613 CYACs compared with 274 539 controls without cancer showed the risk of severe depression or diagnosis of a depressive disorder was significantly raised in CYACs (RR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.29-1.92; I2 = 91%) (Figure 2A). Individually, all studies except one31 found this risk significantly increased in CYACs. The risk was elevated regardless of age at cancer diagnosis and compared with the siblings of CYACs and controls without cancer matched to CYACs (eTables 4 and 5 in Supplement 1). Severe depression tended to develop later in life older than 30 years of age, but interpretation is limited due to a few studies not reporting the duration elapsed since last treatment.

Figure 2. Incidence and Risk Ratios (RRs) in Children, Adolescent, and Young Adult Patients With Cancer (CYACs) Compared With Controls Without Cancer .

Incidence and RRs in CYACs and controls without cancer for severe depression or depressive disorder25,30,31,33,40,41,42,60,61 (A), severe anxiety or anxiety disorder25,30,31,33,40,41,42 (B), and psychotic disorders40,41,42,61,62 (C).

Mean Severity of Depressive Symptoms

The mean severity of depression was found to be elevated in both CYACs receiving active treatment (SMD, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.13-0.74; I2 = 76%) and long-term survivors (SMD, 0.18; 95% CI, 0.02-0.33; I2 = 93%) (Table 1 and eFigure 1, eTable 6, and eTable 7 in Supplement 1). Antineoplastic treatment was not found to be associated with severity of depression. Meta-regression and subgroup analysis demonstrated significant associations of older age at data collection with increased depressive symptoms. Review of the studies examining the course of depressive symptoms in CYACs after diagnosis consistently found elevations within the first 12 months of diagnosis with a proportion experiencing persistent elevations.19,20,21,34,36,46 Subgroup analysis considering the use of various instruments (eFigure 2 in Supplement 1) showed significantly higher severity of depressive symptoms in CYACs studies using the most common instrument, Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS), but not the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI). Each other instrument was only used by 1 or 2 studies.

Table 1. Meta-analyses of Depression Symptom Severity Stratified by Categorical Study-Level Characteristics.

| Variable | No. | SMD (95% CI) | I 2 | Test of interaction (P value) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohorts | Cancer | Control | ||||

| Overall | 21 | 6717 | 22 607 | 0.23 (0.09 to 0.37) | 92% | NA |

| Survivors, in remission | 16 | 6491 | 21 367 | 0.18 (0.02 to 0.33) | 93% | .13 |

| Undergoing or recent treatment | 5 | 226 | 1240 | 0.44 (0.13 to 0.74) | 76% | |

| Age at diagnosis <5 y | 2 | 510 | 2899 | −0.20 (−0.56 to 0.17) | 0 | .04 |

| Age at diagnosis between 5 and 12 y | 5 | 332 | 794 | 0.14 (−0.12 to 0.41) | 74% | |

| Age at diagnosis between 12 and 18 y | 1 | 56 | 391 | 0.61 (0.33 to 0.90) | NA | |

| Age at data collection between 5 and 12 y | 1 | 58 | 64 | 0.15 (0.75 to 0.46) | NA | .75 |

| Age at data collection between 12 and 18 y | 3 | 767 | 1075 | 0.23 (0.09 to 0.55) | 91% | |

| Age at data collection between 18 and 25 y | 7 | 1381 | 2163 | 0.12 (0.11 to 0.34) | 63% | |

| Age at data collection >25 y | 5 | 4385 | 9432 | 0.10 (0.15 to 0.34) | 92% | |

| Continent of study: Europe | 9 | 1102 | 2918 | 0.30 (0.06 to 0.53) | 93% | .87 |

| Continent of study: North America | 8 | 5362 | 17 757 | 0.41 (0.16 to 0.65) | 87% | |

| Continent of study: Asia | 3 | 235 | 1914 | 0.25 (−0.15 to 0.65) | 74% | |

| Compared with matched controls | 17 | 1702 | 13 349 | 0.12 (0.10 to 0.43) | 89% | .41 |

| Compared with siblings | 4 | 5015 | 9258 | 0.26 (0.17 to 0.42) | 94% | |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; SMD, standardized mean difference.

Prevalence and Risk of Anxiety Disorders and Severe Anxiety Symptoms

Meta-analyses were performed using studies assessing anxiety in CYACs.19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50 The specific scales used to measure anxiety symptomatology are presented in eTable 8 in Supplement 1.

Meta-analysis of 21 232 CYACs compared with 210 729 controls without cancer showed the risk of severe anxiety or diagnosis of an anxiety disorder was significantly raised (RR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.14-1.47; I2 = 47%) (Figure 2B). All studies found a significantly increased risk of severe anxiety, except Lund et al41 and Aili et al,31 which found an increased risk that was statistically insignificant. The risk was significantly elevated compared with both siblings of CYACs and noncancer-matched controls with the highest risk in those older than 25 years (eTables 9 and 10 in Supplement 1), but interpretation is again limited due to lack of information in each study regarding the duration elapsed since last treatment.

Mean Severity of Anxiety Symptoms

Meta-analysis was performed of 5110 CYACs and 19 410 controls without cancer. The mean severity of anxiety was found to be elevated in CYACs receiving active treatment (SMD, 0.16; 95% CI, 0.03-0.29; I2 = 0) but not in long-term survivors (SMD, 0.07; 95% CI, −0.07 to 0.22; I2 = 84%) (Table 2 and eFigure 3, eTable 11, and eTable 12 in Supplement 1). Age at cancer diagnosis was not found to be predictive of more severe anxiety later in life nor was type of treatment. Studies that followed up CYACs after diagnosis and over the course of treatment generally found anxiety symptoms significantly elevated but were down trending over the following 12 to 18 months.19,20,21,34,36,46 Meta-regression demonstrated a significant association of older age at data collection with decreased anxiety symptoms, supporting this (eTable 12 in Supplement 1). Subgroup analysis considering the use of various instruments (eFigure 4 in Supplement 1) showed significantly higher severity of anxiety symptoms in CYACs compared with controls without cancer when both HADS and BSI were used. Each other instrument was only used by 1 or 2 studies.

Table 2. Meta-analyses of Anxiety Symptom Severity Stratified by Categorical Study-Level Characteristics.

| Variable | No. | SMD (95% CI) | I 2 | Test of interaction (P value) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohorts | Cancer | Control | ||||

| Overall | 16 | 5110 | 19 410 | 0.09 (−0.01 to 0.20) | 77% | NA |

| Survivors, in remission | 11 | 4906 | 18 194 | 0.07 (−0.07 to 0.22) | 84% | .31 |

| Undergoing or recent treatment | 5 | 204 | 1216 | 0.16 (0.03 to 0.29) | 0 | |

| Age at diagnosis between 0 and 5 y | 2 | 510 | 2899 | 0.08 (−4.62 to 4.77) | 93% | .74 |

| Age at diagnosis between 5 and 12 y | 4 | 238 | 742 | 0.21 (−0.17 to 0.58) | 30% | NA |

| Age at data collection between 5 and 12 y | 2 | 76 | 90 | 0.27 (−0.30 to 0.85) | 0 | <.001 |

| Age at data collection between 18 and 25 y | 6 | 487 | 1232 | 0.09 (0.14 to 0.33) | 63% | NA |

| Age at data collection over 25 y | 5 | 3350 | 14 801 | 0 (−0.22 to 0.21) | 90% | NA |

| Continent of study: Asia | 2 | 76 | 90 | 0.27 (−0.06 to 0.61) | 0 | .26 |

| Continent of study: North America | 6 | 4639 | 16 978 | 0.02 (−0.12 to 0.09) | 88% | |

| Continent of study: Europe | 6 | 226 | 1675 | 0.13 (−0.05 to 0.30) | 1% | |

| Continent of study: Australia | 1 | 18 | 18 | 0 (−0.76 to 0.76) | NA | |

| Compared with caregivers | 1 | 36 | 40 | 0.32 (0.17 to 0.81) | NA | .11 |

| Compared with matched controls | 9 | 478 | 10 064 | 0.12 (0 to 0.21) | 0 | |

| Compared with siblings | 3 | 4349 | 8562 | 0.03 (0.15 to 0.08) | 95% | |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; SMD, standardized mean difference.

Psychotic Disorders

Five studies40,41,42,61,62 examining the risk of psychotic disorders including schizophrenia found this to be significantly increased in 20 549 CYACs compared with 247 038 controls without cancer with minimal heterogeneity (RR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.36-1.80; I2 = 0) (Figure 2C). One study42 used the siblings of CYACs as comparators, and 4 studies40,41,61,62 used a matched comparator cohort. All used the ICD-10 classification, with variation according to the prevailing edition at the time (eTable 13 in Supplement 1), and included all psychotic disorders. Ahomaki et al42 found that schizophrenia and psychotic disorders were highest in those with non-Hodgkin lymphoma and central nervous system cancers and were elevated in female patients compared with male patients. However, Lund et al41 and Hoven et al61 found the risk to be similar in male and female patients.

Suicide Mortality per 100 000 Person-Years

Three studies40,63,64 were included in a meta-analysis of suicide mortality per 100 000 person-years for CYACs. The overall risk was found to be increased at an RR of 1.63, not reaching statistical significance (95% CI, 0.78-3.40) (eFigure 5 in Supplement 1).40,41,42,61,62,63,64

Korhonen et al63 studied 29 285 CYACs totaling 358 000 person-years and compared with 146 282 age-, sex- and country-matched controls totaling 2 735 600 person-years. Risk was found to be significantly elevated in CYACs with central nervous system tumors (RR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.08-2.05) and highest for CYACs diagnosed between the ages of 15 and 19 years (RR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.09-2.39). Nathan et al40 similarly found higher suicide mortality among those diagnosed between 15 and 17.9 years vs those diagnosed when younger than 4 years (RR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.17-2.80; P = .008). Sex yielded inconsistent results with Nathan et al40 finding an increased risk in female individuals whereas Barnes et al64 found a higher risk in male individuals.

Education

Eleven studies24,26,27,48,59,64,65,66,67,69 investigated the association between level of educational attainment and risk of mental health conditions, including depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, and/or suicide (eTable 14 in Supplement 1). Eight of these studies24,26,27,48,59,67,69 found a significant association between lower educational levels and increased risk of mental health conditions or suicide, whereas 3 studies64,65,66 found an insignificant association. Specifically, lower educational attainment was associated with an increased risk of depression,48,55 anxiety,59,67 and combined risk of either depression, somatization, or anxiety (ie, using the BSI-18).24,26,69 For example, Yen et al48 found that those with lower than college education had an increased OR for depression (OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1-2.0) and anxiety (OR, 1.3; 95% CI, 1.0-1.7). Zebrack et al55 also found lower education attainment (less than high school graduate vs college graduate) was associated with increased risk of depression in leukemia survivors (RR, 2.27; 95% CI, 1.24- 4.15; P = .008), Hodgkin disease survivors (RR, 2.56; 95% CI, 1.20-5.43; P = .02) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivors (RR, 5.15; 95% CI, 1.67-15.90; P = .004). van der Geest59 found a similar trend with high education achievement being significantly associated with a lower HADS score (β = −1.28; P < .01) compared with CYACs with medium educational achievement, as did Langeveld et al.67

Income Level

Fourteen studies19,20,25,26,27,40,54,55,62,64,66,67,68,69 investigated associations between income level and the risk of mental health conditions (eTable 15 in Supplement 1). Nine of these studies25,26,27,54,55,62,65,66,67,68,69 found a significant association between patients with lower income compared with patients with higher income and risk of depression. Specifically, being from a lower-income family increased the risk of depression,26,55 anxiety,26 and both combined.27,54,68,69 Notably, Zebrack et al found that lower income (<$20 000 vs >$20 000) was associated with higher raw mean BSI scores for depression (P = .01) and anxiety (P < .001) in survivors of brain cancers.26 Mean scores for depression were also higher in leukemia survivors (RR, 2.67; 95% CI, 1.85-3.85; P < .001) and Hodgkin disease survivors (RR, 2.49; 95% CI, 1.52-4.06; P < .001). Non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivors were the only exception, with no significant increased risk found (RR, 1.23; 95% CI, 0.57-2.69; P = .60).55 Being unemployed was found to be associated with depression (OR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.43-2.63) but not anxiety (OR, 1.0) by Prasad et al.25 Furthermore, Langeveld et al67 found employment status was associated with worse Medical Outcome Study Scale (MOS-24) and Worry questionnaire scores (P < .05). Five studies,19,20,40,64,66 however, found no association between income level and mental health conditions.

Social Environment and Degree of Social Support

Eleven studies19,20,24,25,26,28,48,65,66,67,69 investigated various social supportive factors (marital or partnership status, family functioning, and social integration) and the risk of mental health conditions (eTable 16 in Supplement 1). Eight of these studies20,24,25,26,28,48,66,67 described an association between supportive social factors and risk of mental health conditions. Specifically, partnership status had a lower associated risk for depression24,26,28,48 and anxiety.28,48 Two studies19,20 also elucidated the mediating effect of the health of family functioning. Myers et al20 measured the degree of family functioning using the General Functioning Scale of the Family Assessment Device (FAD-GF) and found a significant association with anxiety (OR, 3.01; 95% CI, 1.76-5.15; P < .001) and depression (OR, 2.37; 95% CI, 1.45-3.85; P = .001) among those with unhealthy family functioning. Kunin-Batson et al,19 who used the FAD-GF as well, found a significant association with depression (OR, 2.62; 95% CI, 1.61-5.92; P = .02) but not anxiety (OR, 1.98; 95% CI, 0.61-6.43; P = .23).

Risk of Bias

Results of risk of bias assessment using the Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal tools (eTable 17 in Supplement 1) showed that although studies overall were not at significant risk of bias, a proportion used normative population data rather than matched controls.19,20,28,36,39,59,64,66,70,71 Publication bias, outlier assessment, and leave-one-out analysis was also performed (eFigures 6-25 in Supplement 1).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this systematic review and meta-analysis was the first to comprehensively analyze the risk, risk factors, and lifetime burden of psychological comorbidity after a cancer diagnosis and treatment in CYACs. Long into survivorship, CYACs may be at increased risk of developing depression, anxiety, psychotic disorders, and schizophrenia after remission of cancer compared with their siblings and controls without cancer. Individual studies found certain subpopulations of CYACs to be at a significantly increased risk of mortality by suicide, even if CYACs as a whole were not. Most notably, these were who CYACs were diagnosed between the older adolescent ages of 15 and 19 years.40,63

This review identified the associations between better mental health of CYACs and a positive social environment, strong social support, and higher levels of education and income, which was consistent with literature of older patients with cancer.72,73 Crucial risk factors pertaining to specific populations particularly vulnerable to developing psychiatric comorbidity were identified. These findings may guide active and passive surveillance strategies for vulnerable subgroups of cancer survivors.74 It is additionally crucial to be cognizant of when mental health issues may develop. Included studies suggested that depression and anxiety symptoms may manifest during treatment or as soon as within 1 year into survivorship. However, reviews of the provision of supportive survivorship care have reported that care may sometimes be provided only 2 years or later into survivorship and may risk not being timely enough.75,76,77 Psycho-oncological interventions may be tailored toward capitalizing on modifiable protective and vulnerability factors,78 such as cognitive behavioral therapy to address the perception of the experience with cancer,78 or involving the family unit to enhance support for the individual.79

We observed that incidence of severe depression and anxiety was higher in long-term cancer survivors compared with controls without cancer. In-depth studies of other forms of psychoemotional trauma in early life similarly found potential associations with psychopathology in later life.80,81 It has been hypothesized that neurodevelopment and biological changes may be part of the causal pathway, with centers of the brain responsible for emotional regulation being especially malleable in early life. Thus, these studies hypothesize that traumatic experiences or buildup of traumatic events over time may result in increased vulnerability to psychopathology.80,81,82,83

CYACs also exhibited significantly increased risk of psychotic disorders including schizophrenia.84 Comprehensive reviews found that biological and psychological trauma increase one’s vulnerability, giving credence as to why a history of cancer and treatment may be a predisposing factor.85 Despite schizophrenia and psychotic disorders having a known strong correlation with family history,86 the study by Ahomaki et al,42 which compared CYACs with their siblings, found that CYACs had 1.4 times more risk of developing schizophrenia and psychotic disorders.

In a subset of our studies, the noncancer control group consisted of siblings or parents of CYACs. Siblings or parents of CYACs can experience psychological stress after an event. This burden may stem from worry for the CYAC or the socioeconomic consequences of the diagnosis and treatment.87 An important mediating factor of the degree of burden experienced by CYACs in relation to their family unit identified in literature is the level of understanding that the CYAC has of their condition.88,89 Although individual studies had varying findings whether CYACs had greater, similar, or lesser psychological symptoms and burden than members of their family unit, this nonetheless highlights how care for the family unit as a whole should not be neglected when considering the lasting psychological burden of a cancer diagnosis.

Limitations

Our review faced several limitations. First, the paucity of longitudinal follow-up data presents a significant limitation. With a large proportion of studies only determining their outcome assessment at one or few time points in the cancer survivors’ later life, we were unable to elucidate when the psychological outcomes truly presented and how they may have progressed. Second, as we anticipated heterogeneity in methods of assessing certain factors such as socioeconomic status, social setup, and education, we planned to adopt the synthesis without meta-analysis approach. Third, there was heterogeneity in the instruments assessing psychological symptoms and disorders. A majority of included studies assessing depression and anxiety used the same 2 instruments, the BSI and HADS, with a minority using other instruments. Fourth, we did not obtain individual patient data for our meta-analysis. Nonetheless, we still managed to performed subgroup analyses and meta-regression according to most key characteristics we planned for, including treatment status with chemotherapy, surgery and radiotherapy, age at cancer diagnosis, and age at the time of study.

Conclusion

Findings of this systematic review and meta-analysis suggest that a diagnosis of cancer and its treatment was not only associated with a significant physical symptom burden but also a lasting psychological impact on the patient, family, and social unit. CYACs may also be at an increased lifetime risk of deleterious psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, and psychotic disorders. However, longitudinal studies are needed to examine the trajectory and prognosis of psychological disorders and symptoms, particularly as issues may arise and progress over time. It is imperative for policy makers and health care professionals to be cognizant of vulnerable subgroups who may develop severe psychiatric and psychological comorbidity. Timely identification, preventive efforts, and psycho-oncological intervention in vulnerable groups especially at risk are recommended.

eTable 1. Search Strategy

eTable 2. Characteristics of Included Studies of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancer Patients

eTable 3. Methods and Scales for Assessing Depression

eTable 4. Meta-analyses of Risk of Severe Depression Stratified by Categorical Study-Level Characteristics Using the Random-Effects Model

eTable 5. Meta-analyses of Risk of Severe Depression Stratified by Categorical Study-Level Characteristics Using the Common Effect Model

eTable 6. Meta-analyses of Depression Symptom Severity Stratified by Categorical Study-Level Characteristics Using the Common Effect Model

eTable 7. Mixed Effects Meta-regression of Standardized Mean Differences Against Potential Effect Moderators (Continuous and Categorical Study-Level Characteristics) for the Longitudinal Association of Depression Symptom Severity in Pediatric Cancer

eTable 8. Methods and Scales for Assessing Anxiety

eTable 9. Meta-analyses of Risk of Severe Anxiety Stratified by Categorical Study-Level Characteristics Using the Random Effects Model

eTable 10. Meta-analyses of Risk of Severe Anxiety Stratified by Categorical Study-Level Characteristics Using the Common Effect Model

eTable 11. Meta-analyses of Anxiety Symptom Severity Stratified by Categorical Study-Level Characteristics Using the Common Effect Model

eTable 12. Mixed Effects Meta-regression of Standardized Mean Differences Against Potential Effect Moderators (Continuous and Categorical Study-Level Characteristics) for the Longitudinal Association of Anxiety Symptom Severity in Pediatric Cancer

eTable 13. Psychotic Disorders Assessed and Method of Diagnosis

eTable 14. Evaluation of the Mediating or Confounding Effect of Education Level of Participants on Psychological Outcomes

eTable 15. Evaluation of the Mediating or Confounding Effect of Income and Socioeconomic Status of Participants on Psychological Outcomes

eTable 16. Evaluation of the Mediating or Confounding Effect of Social Environment and Degree of Social Support of Participants on Psychological Outcomes

eTable 17. Quality Assessment of Included Cohort Studies Using the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tool

eFigure 1. Depressive Symptom Score in CYACs, Compared to Noncancer Controls, Using the Random-Effects Model (Primary Analysis) and Common Effect Model (Sensitivity Analysis)

eFigure 2. Subgroup Analyses of Depression Symptom Severity Stratified by Scales Using the Random-Effects Model

eFigure 3. Anxiety Symptom Score in CYACs, Compared With Noncancer Controls, Using the Random-Effects Model (Primary Analysis) and Common Effect Model (Sensitivity Analysis)

eFigure 4. Subgroup Analyses of Anxiety Symptom Severity Stratified by Scales Using the Random-Effects Model

eFigure 5. Suicide Mortality per 100 000 Person-Years in Children, Adolescent, and Young Adult Patients With Cancer (CYACs) Compared With Controls Without Cancer

eFigure 6. Funnel Plot for Visual Inspection of Publication Bias in Studies Assessing Risk of Severe Depression

eFigure 7. Trim-and-Fill Plot for Publication Bias in Studies Assessing Risk of Severe Depression

eFigure 8. Quantitative Assessment Publication Bias in Studies Assessing Risk of Severe Depression

eFigure 9. Outlier Assessment of Studies Assessing the Risk of Severe Depression of CYACs, Compared With Noncancer Controls, Using the Random-Effects Model (Primary Analysis) and Common Effect Model (Sensitivity Analysis)

eFigure 10. Leave-One-Out Analysis of Studies Assessing the Risk of Severe Depression, Compared With Noncancer Controls, Using the Random-Effects Model (Primary Analysis) and Common Effect Model (Sensitivity Analysis)

eFigure 11. Funnel Plot for Visual Inspection of Publication Bias in Studies Assessing Depressive Symptom Score

eFigure 12. Trim-and-Fill Plot for Publication Bias in Studies Assessing Depressive Symptom Score

eFigure 13. Quantitative Assessment Publication Bias in Studies Assessing Depressive Symptom Score

eFigure 14. Outlier Assessment of Studies Assessing the Depressive Symptom Score of CYACs, Compared With Noncancer Controls, Using the Random-Effects Model (Primary Analysis) and Common Effect Model (Sensitivity Analysis)

eFigure 15. Leave-One-Out Analysis of Studies Assessing the Depressive Symptom Score, Compared With Noncancer Controls, Using the Random-Effects Model (Primary Analysis) and Common Effect Model (Sensitivity Analysis)

eFigure 16. Funnel Plot for Visual Inspection of Publication Bias in Studies Assessing Risk of Severe Anxiety

eFigure 17. Trim-and-Fill Plot for Publication Bias in Studies Assessing Risk of Severe Anxiety

eFigure 18. Quantitative Assessment Publication Bias in Studies Assessing Risk of Severe Anxiety

eFigure 19. Outlier Assessment of Studies Assessing the Risk of Severe Anxiety of CYACs, Compared With Noncancer Controls, Using the Random-Effects Model (Primary Analysis) and Common Effect Model (Sensitivity Analysis)

eFigure 20. Leave-One-Out Analysis of Studies Assessing the Risk of Severe Anxiety, Compared With Noncancer Controls, Using the Random-Effects Model (Primary Analysis) and Common Effect Model (Sensitivity Analysis)

eFigure 21. Funnel Plot for Visual Inspection of Publication Bias in Studies Assessing Anxiety Symptom Score

eFigure 22. Trim-and-Fill Plot for Publication Bias in Studies Assessing Anxiety Symptom Score

eFigure 23. Quantitative Assessment Publication Bias in Studies Assessing Anxiety Symptom Score

eFigure 24. Outlier Assessment of Studies Assessing the Anxiety Symptom Score of CYACs, Compared With Noncancer Controls, Using the Random-Effects Model (Primary Analysis) and Common Effect Model (Sensitivity Analysis)

eFigure 25. Leave-One-Out Analysis of Studies Assessing the Anxiety Symptom Score, Compared With Noncancer Controls, Using the Random-Effects Model (Primary Analysis) and Common Effect Model (Sensitivity Analysis)

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Johnston WT, Erdmann F, Newton R, Steliarova-Foucher E, Schüz J, Roman E. Childhood cancer: estimating regional and global incidence. Cancer Epidemiol. 2021;71(pt B):101662. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2019.101662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaatsch P. Epidemiology of childhood cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36(4):277-285. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2010.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gurney JG, Kadan-Lottick NS, Packer RJ, et al. Endocrine and cardiovascular late effects among adult survivors of childhood brain tumors: Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer. 2003;97(3):663-673. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Packer RJ, Gurney JG, Punyko JA, et al. Long-term neurologic and neurosensory sequelae in adult survivors of a childhood brain tumor: Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(17):3255-3261. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li HC, Chung OK, Chiu SY. The impact of cancer on children’s physical, emotional, and psychosocial well-being. Cancer Nurs. 2010;33(1):47-54. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181aaf0fa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1572-1582. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa060185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee A, Yau CE, Low CE, et al. Natural progression of left ventricular function following anthracyclines without cardioprotective therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(2). doi: 10.3390/cancers15020512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li J, Lee ARYB, Chen CK, Koo C-Y, Lee MX, Sia C-H. Primary prevention of cardiotoxicity in paediatric cancer patients receiving anthracyclines: systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy and safety profiles. Authorea. 2023.doi: 10.22541/au.167767924.48783917/v1 [DOI]

- 9.Barnes N, Chemaitilly W. Endocrinopathies in survivors of childhood neoplasia. Front Pediatr. 2014;2:101. doi: 10.3389/fped.2014.00101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gurney JG, Krull KR, Kadan-Lottick N, et al. Social outcomes in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(14):2390-2395. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372(71). doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munn Z, Moola S, Riitano D, Lisy K. The development of a critical appraisal tool for use in systematic reviews addressing questions of prevalence. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2014;3(3):123-128. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Munn Z, Barker TH, Moola S, et al. Methodological quality of case series studies: an introduction to the JBI critical appraisal tool. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18(10):2127-2133. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Routledge; 1988. doi: 10.4324/9780203771587. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539-1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campbell M, McKenzie JE, Sowden A, et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. BMJ. 2020;368:l6890. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l6890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455-463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peters JL, Sutton AJ, Jones DR, Abrams KR, Rushton L. Performance of the trim and fill method in the presence of publication bias and between-study heterogeneity. Stat Med. 2007;26(25):4544-4562. doi: 10.1002/sim.2889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kunin-Batson AS, Lu X, Balsamo L, et al. Prevalence and predictors of anxiety and depression after completion of chemotherapy for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A prospective longitudinal study. Cancer. 2016;122(10):1608-1617. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Myers RM, Balsamo L, Lu X, et al. A prospective study of anxiety, depression, and behavioral changes in the first year after a diagnosis of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer. 2014;120(9):1417-1425. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yardeni M, Abebe Campino G, Hasson-Ohayon I, et al. Trajectories and risk factors for anxiety and depression in children and adolescents with cancer: a 1-year follow-up. Cancer Med. 2021;10(16):5653-5660. doi: 10.1002/cam4.4100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kazak AE, Derosa BW, Schwartz LA, et al. Psychological outcomes and health beliefs in adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood cancer and controls. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(12):2002-2007. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ford JS, Chou JF, Sklar CA, et al. Psychosocial outcomes in adult survivors of retinoblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(31):3608-3614. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.5733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shin H, Dudley WN, Bhakta N, et al. Associations of symptom clusters and health outcomes in adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the St Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(3):497-507. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.00361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prasad PK, Hardy KK, Zhang N, et al. Psychosocial and neurocognitive outcomes in adult survivors of adolescent and early young adult cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(23):2545-2552. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.7528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zebrack BJ, Gurney JG, Oeffinger K, et al. Psychological outcomes in long-term survivors of childhood brain cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(6):999-1006. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zebrack BJ, Zevon MA, Turk N, et al. Psychological distress in long-term survivors of solid tumors diagnosed in childhood: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49(1):47-51. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Laage A, Allodji R, Dauchy S, et al. Screening for psychological distress in very long-term adult survivors of childhood cancer. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2016;33(5):295-313. doi: 10.1080/08880018.2016.1204400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krull KR, Annett RD, Pan Z, et al. Neurocognitive functioning and health-related behaviours in adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(9):1380-1388. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brinkman TM, Lown EA, Li C, et al. Alcohol consumption behaviors and neurocognitive dysfunction and emotional distress in adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Addiction. 2019;114(2):226-235. doi: 10.1111/add.14439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aili K, Arvidsson S, Nygren JM. Health related quality of life and buffering factors in adult survivors of acute pediatric lymphoblastic leukemia and their siblings. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2021;19(1):55. doi: 10.1186/s12955-021-01700-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu W, Cheung YT, Brinkman TM, et al. Behavioral symptoms and psychiatric disorders in child and adolescent long-term survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated with chemotherapy only. Psychooncology. 2018;27(6):1597-1607. doi: 10.1002/pon.4699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seitz DC, Besier T, Debatin KM, et al. Posttraumatic stress, depression and anxiety among adult long-term survivors of cancer in adolescence. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(9):1596-1606. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Larsson G, Mattsson E, von Essen L. Aspects of quality of life, anxiety, and depression among persons diagnosed with cancer during adolescence: a long-term follow-up study. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(6):1062-1068. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Monteiro S, Torres A, Morgadinho R, Pereira A. Psychosocial outcomes in young adults with cancer: emotional distress, quality of life, and personal growth. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2013;27(6):299-305. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2013.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jorngarden A, Mattsson E, von Essen L. Health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression among adolescents and young adults with cancer: a prospective longitudinal study. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(13):1952-1958. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.05.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kremer AL, Schieber K, Metzler M, Schuster S, Erim Y. Long-term positive and negative psychosocial outcomes in young childhood cancer survivors, type 1 diabetics, and their healthy peers. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2016;29(6). doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2016-0027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanellopoulos A, Hamre HM, Dahl AA, Fossa SD, Ruud E. Factors associated with poor quality of life in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia and lymphoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(5):849-855. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Erp LME, Maurice-Stam H, Kremer LCM, et al. A vulnerable age group: the impact of cancer on the psychosocial well-being of young adult childhood cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(8):4751-4761. doi: 10.1007/s00520-021-06009-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nathan PC, Nachman A, Sutradhar R, et al. Adverse mental health outcomes in a population-based cohort of survivors of childhood cancer. Cancer. 2018;124(9):2045-2057. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lund LW, Winther JF, Dalton SO, et al. Hospital contact for mental disorders in survivors of childhood cancer and their siblings in Denmark: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(10):971-980. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70351-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ahomaki R, Gunn ME, Madanat-Harjuoja LM, Matomaki J, Malila N, Lahteenmaki PM. Late psychiatric morbidity in survivors of cancer at a young age: a nationwide registry-based study. Int J Cancer. 2015;137(1):183-192. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.D’Souza AM, Devine KA, Reiter-Purtill J, Gerhardt CA, Vannatta K, Noll RB. Internalizing symptoms in AYA survivors of childhood cancer and matched comparisons. Psychooncology. 2019;28(10):2009-2016. doi: 10.1002/pon.5183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barone R, Gulisano M, Cannata E, et al. Self- and parent-reported psychological symptoms in young cancer survivors and control peers: results from a clinical center. J Clin Med. 2020;9(11). doi: 10.3390/jcm9113444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pedreira CC, Stargatt R, Maroulis H, et al. Health related quality of life and psychological outcome in patients treated for craniopharyngioma in childhood. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2006;19(1):15-24. doi: 10.1515/JPEM.2006.19.1.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sargin Yildirim N, Demirkaya M, Sevinir BB, et al. A prospective follow-up of quality of life, depression, and anxiety in children with lymphoma and solid tumors. Turk J Med Sci. 2017;47(4):1078-1088. doi: 10.3906/sag-1510-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yaffe Ornstein M, Friedlander E, Katz S, Elhasid R. Prospective assessment of anxiety among pediatric oncology patients and their caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic a cohort study. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2023;41(2)182-195. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2022.2086092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yen HJ, Eissa HM, Bhatt NS, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in survivors of childhood hematologic malignancies with hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Blood. 2020;135(21):1847-1858. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019003858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cantrell MA, Posner MA. Psychological distress between young adult female survivors of childhood cancer and matched female cohorts surveyed in the adolescent health study. Cancer Nurs. 2014;37(4):271-277. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang IC, Brinkman TM, Armstrong GT, Leisenring W, Robison LL, Krull KR. Emotional distress impacts quality of life evaluation: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11(3):309-319. doi: 10.1007/s11764-016-0589-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ljungman L, Remes T, Westin E, et al. Health-related quality of life in long-term survivors of childhood brain tumors: a population-based cohort study. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(6):5157-5166. doi: 10.1007/s00520-022-06905-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Harila MJ, Niinivirta TI, Winqvist S, Harila-Saari AH. Low depressive symptom and mental distress scores in adult long-term survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33(3):194-198. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181ff0e2e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zheng DJ, Krull KR, Chen Y, et al. Long-term psychological and educational outcomes for survivors of neuroblastoma: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer. 2018;124(15):3220-3230. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Foster RH, Hayashi RJ, Wang M, et al. Psychological, educational, and social late effects in adolescent survivors of Wilms tumor: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Psychooncology. 2021;30(3):349-360. doi: 10.1002/pon.5584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zebrack BJ, Zeltzer LK, Whitton J, et al. Psychological outcomes in long-term survivors of childhood leukemia, Hodgkin disease, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatrics. 2002;110(1 Pt 1):42-52. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.1.42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arabiat DH, Elliott B, Draper P. The prevalence of depression in pediatric oncology patients undergoing chemotherapy treatment in Jordan. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2012;29(5):283-288. doi: 10.1177/1043454212451524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schwartz L, Drotar D. Posttraumatic stress and related impairment in survivors of childhood cancer in early adulthood compared to healthy peers. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;31(4):356-366. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gupta V, Singh A, Singh TB, Upadhyay S. Psychological morbidity in children undergoing chemotherapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Indian J Pediatr. 2014;81(7):699-701. doi: 10.1007/s12098-013-1211-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van der Geest IM, van Dorp W, Hop WC, et al. Emotional distress in 652 Dutch very long-term survivors of childhood cancer, using the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS). J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2013;35(7):525-529. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31829f2799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Akechi T, Mishiro I, Fujimoto S. Risk of major depressive disorder in adolescent and young adult cancer patients in Japan. Psychooncology. 2022;31(6):929-937. doi: 10.1002/pon.5881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hoven E, Ljung R, Ljungman G, et al. Increased risk of mental health problems after cancer during adolescence: a register-based cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2020;147(12):3349-3360. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.De R, Sutradhar R, Kurdyak P, et al. Incidence and predictors of mental health outcomes among survivors of adolescent and young adult cancer: a population-based study using the IMPACT cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(9):1010-1019. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.02019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Korhonen LM, Taskinen M, Rantanen M, et al. Suicides and deaths linked to risky health behavior in childhood cancer patients: a Nordic population-based register study. Cancer. 2019;125(20):3631-3638. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barnes JM, Johnson KJ, Grove JL, Srivastava AJ, Osazuwa-Peters N, Perkins SM. Risk of suicide among individuals with a history of childhood cancer. Cancer. 2022;128(3):624-632. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hamre H, Zeller B, Kanellopoulos A, et al. High prevalence of chronic fatigue in adult long-term survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia and lymphoma during childhood and adolescence. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2013;2(1):2-9. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2012.0015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Michel G, Rebholz CE, von der Weid NX, Bergstraesser E, Kuehni CE. Psychological distress in adult survivors of childhood cancer: the Swiss Childhood Cancer Survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(10):1740-1748. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.4534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Langeveld NE, Grootenhuis MA, Voute PA, de Haan RJ, van den Bos C. Quality of life, self-esteem and worries in young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psychooncology. 2004;13(12):867-881. doi: 10.1002/pon.800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schultz KAP, Ness KK, Whitton J, et al. Behavioral and social outcomes in adolescent survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(24):3649-3656. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hudson MM, Mertens AC, Yasui Y, et al. Health status of adult long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA. 2003;290(12):1583-1592. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.12.1583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang P, Zhang L, Hou X. Incidence of suicide among adolescent and young adult cancer patients: a population-based study. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21(1):540. doi: 10.1186/s12935-021-02225-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ross L, Johansen C, Dalton SO, et al. Psychiatric hospitalizations among survivors of cancer in childhood or adolescence. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(7):650-657. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wen S, Xiao H, Yang Y. The risk factors for depression in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(1):57-67. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4466-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lee ARYB, Leong I, Lau G, et al. Depression and anxiety in older adults with cancer: systematic review and meta-summary of risk, protective and exacerbating factors. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2023;81:32-42. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2023.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Marchak JG, Christen S, Mulder RL, et al. Recommendations for the surveillance of mental health problems in childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer survivors: a report from the International Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Guideline Harmonization Group. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(4):e184-e196. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00750-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tonorezos ES, Barnea D, Cohn RJ, et al. Models of care for survivors of childhood cancer from across the globe: advancing survivorship care in the next decade. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(21):2223-2230. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.5180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Effinger KE, Haardörfer R, Marchak JG, et al. Current pediatric cancer survivorship practices: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J Cancer Surviv. Published online January 31, 2022. doi: 10.1007/s11764-021-01157-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Song A, Fish JD. Caring for survivors of childhood cancer: it takes a village. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2018;30(6):864-873. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Coughtrey A, Millington A, Bennett S, et al. The effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for psychological outcomes in pediatric oncology: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55(3):1004-1017. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Koumarianou A, Symeonidi AE, Kattamis A, Linardatou K, Chrousos GP, Darviri C. A review of psychosocial interventions targeting families of children with cancer. Palliat Support Care. 2021;19(1):103-118. doi: 10.1017/S1478951520000449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lähdepuro A, Savolainen K, Lahti-Pulkkinen M, et al. The impact of early life stress on anxiety symptoms in late adulthood. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):4395. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-40698-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Maschi T, Baer J, Morrissey MB, Moreno C. The aftermath of childhood trauma on late life mental and physical health: a review of the literature. Traumatology. 2013;19(1):49-64. doi: 10.1177/1534765612437377 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.De Bellis MD, Zisk A. The biological effects of childhood trauma. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2014;23(2):185-222, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2014.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.van der Kolk BA. The neurobiology of childhood trauma and abuse. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2003;12(2):293-317, ix. doi: 10.1016/S1056-4993(03)00003-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.van Winkel R, van Nierop M, Myin-Germeys I, van Os J. Childhood trauma as a cause of psychosis: linking genes, psychology, and biology. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58(1):44-51. doi: 10.1177/070674371305800109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Radua J, Ramella-Cravaro V, Ioannidis JPA, et al. What causes psychosis—an umbrella review of risk and protective factors. World Psychiatry. 2018;17(1):49-66. doi: 10.1002/wps.20490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mortensen PB, Pedersen MG, Pedersen CB. Psychiatric family history and schizophrenia risk in Denmark: which mental disorders are relevant? Psychol Med. 2010;40(2):201-210. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kessler RC. The effects of stressful life events on depression. Annu Rev Psychol. 1997;48:191-214. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Knighting K, Rowa-Dewar N, Malcolm C, Kearney N, Gibson F. Children’s understanding of cancer and views on health-related behaviour: a ‘draw and write’ study. Child Care Health Dev. 2011;37(2):289-299. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01138.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bluebond-Langner M, Perkel D, Goertzel T, Nelson K, McGeary J. Children’s knowledge of cancer and its treatment: impact of an oncology camp experience. J Pediatr. 1990;116(2):207-213. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(05)82876-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Search Strategy

eTable 2. Characteristics of Included Studies of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancer Patients

eTable 3. Methods and Scales for Assessing Depression

eTable 4. Meta-analyses of Risk of Severe Depression Stratified by Categorical Study-Level Characteristics Using the Random-Effects Model

eTable 5. Meta-analyses of Risk of Severe Depression Stratified by Categorical Study-Level Characteristics Using the Common Effect Model

eTable 6. Meta-analyses of Depression Symptom Severity Stratified by Categorical Study-Level Characteristics Using the Common Effect Model

eTable 7. Mixed Effects Meta-regression of Standardized Mean Differences Against Potential Effect Moderators (Continuous and Categorical Study-Level Characteristics) for the Longitudinal Association of Depression Symptom Severity in Pediatric Cancer

eTable 8. Methods and Scales for Assessing Anxiety

eTable 9. Meta-analyses of Risk of Severe Anxiety Stratified by Categorical Study-Level Characteristics Using the Random Effects Model

eTable 10. Meta-analyses of Risk of Severe Anxiety Stratified by Categorical Study-Level Characteristics Using the Common Effect Model

eTable 11. Meta-analyses of Anxiety Symptom Severity Stratified by Categorical Study-Level Characteristics Using the Common Effect Model

eTable 12. Mixed Effects Meta-regression of Standardized Mean Differences Against Potential Effect Moderators (Continuous and Categorical Study-Level Characteristics) for the Longitudinal Association of Anxiety Symptom Severity in Pediatric Cancer

eTable 13. Psychotic Disorders Assessed and Method of Diagnosis

eTable 14. Evaluation of the Mediating or Confounding Effect of Education Level of Participants on Psychological Outcomes

eTable 15. Evaluation of the Mediating or Confounding Effect of Income and Socioeconomic Status of Participants on Psychological Outcomes

eTable 16. Evaluation of the Mediating or Confounding Effect of Social Environment and Degree of Social Support of Participants on Psychological Outcomes

eTable 17. Quality Assessment of Included Cohort Studies Using the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tool

eFigure 1. Depressive Symptom Score in CYACs, Compared to Noncancer Controls, Using the Random-Effects Model (Primary Analysis) and Common Effect Model (Sensitivity Analysis)

eFigure 2. Subgroup Analyses of Depression Symptom Severity Stratified by Scales Using the Random-Effects Model

eFigure 3. Anxiety Symptom Score in CYACs, Compared With Noncancer Controls, Using the Random-Effects Model (Primary Analysis) and Common Effect Model (Sensitivity Analysis)

eFigure 4. Subgroup Analyses of Anxiety Symptom Severity Stratified by Scales Using the Random-Effects Model

eFigure 5. Suicide Mortality per 100 000 Person-Years in Children, Adolescent, and Young Adult Patients With Cancer (CYACs) Compared With Controls Without Cancer

eFigure 6. Funnel Plot for Visual Inspection of Publication Bias in Studies Assessing Risk of Severe Depression

eFigure 7. Trim-and-Fill Plot for Publication Bias in Studies Assessing Risk of Severe Depression

eFigure 8. Quantitative Assessment Publication Bias in Studies Assessing Risk of Severe Depression

eFigure 9. Outlier Assessment of Studies Assessing the Risk of Severe Depression of CYACs, Compared With Noncancer Controls, Using the Random-Effects Model (Primary Analysis) and Common Effect Model (Sensitivity Analysis)

eFigure 10. Leave-One-Out Analysis of Studies Assessing the Risk of Severe Depression, Compared With Noncancer Controls, Using the Random-Effects Model (Primary Analysis) and Common Effect Model (Sensitivity Analysis)

eFigure 11. Funnel Plot for Visual Inspection of Publication Bias in Studies Assessing Depressive Symptom Score

eFigure 12. Trim-and-Fill Plot for Publication Bias in Studies Assessing Depressive Symptom Score

eFigure 13. Quantitative Assessment Publication Bias in Studies Assessing Depressive Symptom Score

eFigure 14. Outlier Assessment of Studies Assessing the Depressive Symptom Score of CYACs, Compared With Noncancer Controls, Using the Random-Effects Model (Primary Analysis) and Common Effect Model (Sensitivity Analysis)

eFigure 15. Leave-One-Out Analysis of Studies Assessing the Depressive Symptom Score, Compared With Noncancer Controls, Using the Random-Effects Model (Primary Analysis) and Common Effect Model (Sensitivity Analysis)

eFigure 16. Funnel Plot for Visual Inspection of Publication Bias in Studies Assessing Risk of Severe Anxiety

eFigure 17. Trim-and-Fill Plot for Publication Bias in Studies Assessing Risk of Severe Anxiety

eFigure 18. Quantitative Assessment Publication Bias in Studies Assessing Risk of Severe Anxiety

eFigure 19. Outlier Assessment of Studies Assessing the Risk of Severe Anxiety of CYACs, Compared With Noncancer Controls, Using the Random-Effects Model (Primary Analysis) and Common Effect Model (Sensitivity Analysis)

eFigure 20. Leave-One-Out Analysis of Studies Assessing the Risk of Severe Anxiety, Compared With Noncancer Controls, Using the Random-Effects Model (Primary Analysis) and Common Effect Model (Sensitivity Analysis)

eFigure 21. Funnel Plot for Visual Inspection of Publication Bias in Studies Assessing Anxiety Symptom Score

eFigure 22. Trim-and-Fill Plot for Publication Bias in Studies Assessing Anxiety Symptom Score

eFigure 23. Quantitative Assessment Publication Bias in Studies Assessing Anxiety Symptom Score

eFigure 24. Outlier Assessment of Studies Assessing the Anxiety Symptom Score of CYACs, Compared With Noncancer Controls, Using the Random-Effects Model (Primary Analysis) and Common Effect Model (Sensitivity Analysis)

eFigure 25. Leave-One-Out Analysis of Studies Assessing the Anxiety Symptom Score, Compared With Noncancer Controls, Using the Random-Effects Model (Primary Analysis) and Common Effect Model (Sensitivity Analysis)

Data Sharing Statement