BACKGROUND

U.S. hospitals have made great strides in reducing the incidence of central line-associated blood stream infections (CLABSIs). Between 2008 and 2015 there was a 50% reduction in the national CLABSI rate,1 which can be linked to CMS (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) reimbursement penalties that spurred routine hospital-wide surveillance and standardized clinical processes.2 Despite this success, the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) has noted that there is a need for further improvement, and they have set a goal to reduce the national CLABSI rate another 50% by 2020.1

The CMS penalties that have driven CLABSI reductions are calculated based on the standardized infection ratio (SIR), defined as the number of observed infections for the hospital divided by the number of predicted infections and adjusted for both the number of central line device days a hospital reports and the hospital’s structural characteristics (e.g., bed size, number of ICU beds, status as a teaching hospital).3 However, using central line days to risk adjust the SIR can mask success for hospitals that are able to reduce both the use of central lines as well as the number of CLABSIs.4,5 Based on current SIR calculation methods, a hospital that reports a higher number of central line device days and CLABSIs can have the same SIR as a hospital reporting fewer device days and infections,4-6 but this relationship has yet to be empirically studied using a national dataset. The goal of this study was to describe the relationship between the SIR and the variation in device days and CLABSI rates among U.S. hospitals with similar characteristics; specifically, a subgroup of hospitals that treat highly complex patients while serving as a safety net in their community.7,8

METHODS

Data, Variables, and Study Sample

This study used the CMS Hospital Compare 2016 infection data at U.S. hospitals, including CLABSI SIRs, predicted and actual numbers of CLABSIs, and the number of central line device days. Using Medicare identification numbers, this primary data set was merged with the FY2016 CMS Impact File and the FY2015 CMS Healthcare Cost Report Information System File in order to obtain hospital characteristics; this dataset consisted of 2,001 U.S. hospitals.

In order to identify our analytic sample, we operationalized a variable for hospitals that treat high-complexity patients (i.e., high-complexity hospitals) as those with both hospital patient case-mix index (CMI) and percent share of Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments in the top quartile of U.S. hospitals.8

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the analytic sample. Next, we generated scatter plots to visualize the distribution of hospitals across the central line use and infection rate variables. Additionally, we verified that the hospitals in the analytic sample were similar in regard to the characteristics included in the SIR predictive model.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the infection rate and line day variables for the 215 high-complexity hospitals. The number of CLABSIs ranged from 0 to 138 and the number of line days from 1,770 to 122,679. The number of ICU beds ranged from 6 to 323 with a median of 57.

Table 1:

Descriptive statistics of the infection and line day variables for the 215 high-complexity hospitals

| Central Line Days |

CLABSI predicted |

CLABSI observed |

SIR | # of ICU Beds |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | 21485 | 23 | 21 | 1 | 72 |

| median | 16986 | 18 | 15 | 1 | 57 |

| std. deviation | 17021 | 20 | 21 | 1 | 50 |

| minimum | 1770 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| maximum | 122679 | 137 | 138 | 4 | 323 |

A few scenarios from our analytic sample illustrate the variation in line days and CLABSI rates for hospitals with similar SIR scores. Hospitals A and B have 199 and 190 ICU beds, respectively, and both have a SIR of 0.5. Hospital A reported 27 CLABSIs from 42,520 lines days while Hospital B reported 47 CLABSIs from 72,532 lines days. Both of these hospitals have low SIR scores and were financially rewarded by CMS; however, Hospital B reported almost double the number of CLABSIs. indicating a much higher infection burden in that hospital.

Notably, this variation is also present among hospitals with higher SIRs. For instance, both Hospitals C and D had about 100 ICU beds (100 and 104, respectively) and SIRs of 1.7 – indicating a higher infection rate than predicted for a hospital with similar characteristics. While Hospital C reported 52 CLABSIs from 23,102 lines day, Hospital D reported 105 CLABSIs from 52,109 lines days, again indicating a much higher infection burden for the same SIR score.

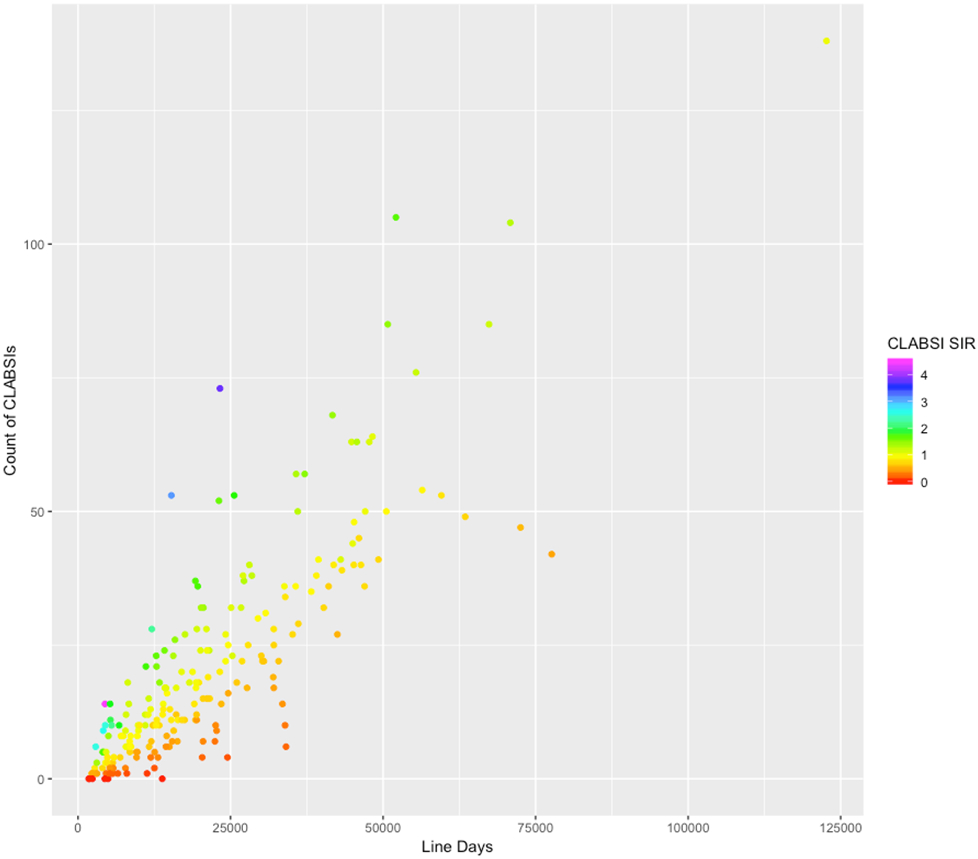

Figure 1 presents a scatter plot of the findings from Table 1. The distribution of the number of reported CLABSIs and line days across the SIRs shows a wide distribution in rates of line use and infections for a given SIR. In the scatter plot, each SIR score is denoted by a different dot color.

Figure 1:

Visual presentation of the distribution in the number of CLABSIs and line days among the group of high-complexity hospitals; each SIR score is denoted by a different dot color.

DISCUSSION

Our analyses demonstrate that similar hospitals can have the same SIR but very different numbers of line days and CLABSI rates. This variation in infection burden may translate to non-trivial differences in patient safety experiences. Our findings have important policy implications because the CMS value-based purchasing program incentives should, ideally, reward both absolute reduction of line use and relative incidence of infection.

Current Federal infection prevention policies, however, are focused on infection rates. The same 2016 CDC report that set new CLABSI goals for 2020 also reported that the national central line device utilization rate had stayed constant for the past six years. The report further noted that there is a net benefit to patients in focusing on both line safety and reducing line use; however, this type of success, while noted by the CDC as integral to a CLABSI-prevention strategy, is not currently rewarded by the SIR calculation.

An alternative publicly available metric that controls for these issues is the hospital- and unit-level standardized utilization ratio (SUR). This CDC metric is a risk-adjusted rate that compares the actual device days reported to what would be predicted for a hospital with similar characteristics. While CMS’s 2019 value-based purchasing methodology will still rely on the SIR, our results suggest that incorporating the SUR into the methodology for calculating financial penalties may more appropriately measure infection prevention than a SIR that is adjusted for each hospital’s rate of central line use.

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Grant R01HS024958.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have no competing interests to disclose

References

- 1.CDC. Healthcare-associated Infections in the United States, 2006-2016: A Story of Progress. 2017. [updated January 5, 2018; cited 2018 July 1]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hai/surveillance/data-reports/data-summary-assessing-progress.html.

- 2.Krein SL, Fowler KE, Ratz D, Meddings J, Saint S. Preventing device-associated infections in US hospitals: national surveys from 2005 to 2013. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015. Jun;24(6):385–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC. THE NHSN STANDARDIZED INFECTION RATIO (SIR): A Guide to the SIR. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018. [updated March 2018; cited 2018 July]. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright MO, Kharasch M, Beaumont JL, Peterson LR, Robicsek A. Reporting catheter-associated urinary tract infections: denominator matters. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011. Jul;32(7):635–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abrantes-Figueiredo JI, Ross JW, Banach DB. Device Utilization Ratios in Infection Prevention: Process or Outcome Measure? Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2018. Mar 23;20(5):8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fakih MG, Gould CV, Trautner BW, Meddings J, Olmsted RN, Krein SL, et al. Beyond Infection: Device Utilization Ratio as a Performance Measure for Urinary Catheter Harm. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016. Mar;37(3):327–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rajaram R, Chung JW, Kinnier CV, Barnard C, Mohanty S, Pavey ES, et al. Hospital Characteristics Associated With Penalties in the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program. JAMA. 2015. Jul 28;314(4):375–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bazzoli GJ, Thompson MP, Waters TM. Medicare Payment Penalties and Safety Net Hospital Profitability: Minimal Impact on These Vulnerable Hospitals. Health Serv Res. 2018. Feb 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]