Abstract

Aims

The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders prior to total hip (THA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and to assess their impact on the rates of any infection, revision, or reoperation.

Methods

Between January 2000 and March 2019, 21,469 primary and revision arthroplasties (10,011 THAs; 11,458 TKAs), which were undertaken in 15,504 patients at a single academic medical centre, were identified from a 27-county linked electronic medical record (EMR) system. Depressive and anxiety disorders were identified by diagnoses in the EMR or by using a natural language processing program with subsequent validation from review of the medical records. Patients with mental health diagnoses other than anxiety or depression were excluded.

Results

Depressive and/or anxiety disorders were common before THA and TKA, with a prevalence of 30% in those who underwent primary THA, 33% in those who underwent revision THA, 32% in those who underwent primary TKA, and 35% in those who underwent revision TKA. The presence of depressive or anxiety disorders was associated with a significantly increased risk of any infection (primary THA, hazard ratio (HR) 1.5; revision THA, HR 1.9; primary TKA, HR 1.6; revision TKA, HR 1.8), revision (THA, HR 1.7; TKA, HR 1.6), re-revision (THA, HR 2.0; TKA, HR 1.6), and reoperation (primary THA, HR 1.6; revision THA, HR 2.2; primary TKA, HR 1.4; revision TKA, HR 1.9; p < 0.03 for all). Patients with preoperative depressive and/or anxiety disorders were significantly less likely to report “much better” joint function after primary THA (78% vs 87%) and primary TKA (86% vs 90%) compared with those without these disorders at two years postoperatively (p < 0.001 for all).

Conclusion

The presence of depressive or anxiety disorders prior to primary or revision THA and TKA is common, and associated with a significantly higher risk of infection, revision, reoperation, and dissatisfaction. This topic deserves further study, and surgeons may consider mental health optimization to be of similar importance to preoperative variables such as diabetic control, prior to arthroplasty.

Introduction

Mental health conditions, including depression and anxiety, are common and increasingly linked with worse outcomes in healthcare. An awareness of the influence of these conditions on pain and physical wellbeing has increased among providers in recent years.1–3 Mental and social health factors have been identified as potential contributors to persistent pain, dissatisfaction, and complication rates following total hip arthroplasty (THA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA).4– 8 Previous investigations have suggested that up to 20% of patients are dissatisfied following primary TKA.9 Depressive and anxiety disorders may also adversely affect satisfaction after THA and TKA.5,10

Previous studies have been limited by relatively small sample sizes and a reliance on diagnostic codes alone, or on the isolated perioperative use of medication.6,7,11–14 Depression has been identified as a risk factor for revision, the mechanical failure of components, periprosthetic fracture, cellulitis, and periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) after primary THA and TKA.12,14,15 However, there has been little investigation into the impact of depression or anxiety on the outcome after revision THA and TKA.16

Thus, the aim of this study was to define the prevalence of preoperative depressive and anxiety disorders, and assess the impact of these disorders on the rates of infection, revision, reoperation, nonoperative complications, and satisfaction after primary and revision THA and TKA.

Methods

After obtaining institutional review board approval, we retrospectively identified patients who underwent primary or revision THA or TKA at the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minnesota, USA) between January 2000 to March 2019, with a minimum of two years’ potential follow-up. Patients aged > 18 years who had provided research authorization were identified from our institutional total joint registry (TJR), and subsequently restricted to regional patients within the Expansion of the Rochester Epidemiology Project (E- REP) at the time of surgery.17,18 In brief, the E- REP records-linkage system provides access to medical records for all residents of 27 counties in southern Minnesota and western Wisconsin, irrespective of which facility delivered care. This population-based data infrastructure allows access to the longitudinal medical histories of patients in a geographically defined community. Importantly, it also allows the medical records to be reviewed for the validation of diagnoses and outcomes.

Clinical characteristics, demographics, and outcome data were obtained from our TJR and the electronic medical record (EMR). Patients were followed by in-person or mail communication including at three months, one, two, and five years, and at five-year intervals thereafter. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) were assessed using the Harris Hip Score (HHS)19 and Knee Society Score (KSS).20 Revisions were defined as any exchange of components, and reoperations were defined as subsequent surgery related to the arthroplasty separate from of exchange of components. Nonoperative complications included wound complications, nonoperatively treated periprosthetic fractures, dislocations of the hip, thromboembolic events, patellar complications, and neurological injuries. Infections were identified by review of documentation by orthopaedic surgeons and infectious disease physicians. Infections were classified as deep or superficial based on laboratory and aspiration results. The presence of depression and/or anxiety was determined from either International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis codes, or by the preoperative use of medications targeted at anxiety or depression within the two years preceding arthroplasty.21 Patients with mental health diagnoses other than depression or anxiety such as bipolar conditions and schizophrenia were excluded based on diagnosis codes.

The use of medication preoperatively was determined using an open-source natural language processing program called Medtagger that identified medications in the EMR categorized by the Rxnorm Unified Medical Language System as antidepressants.22,23 All appearances of these medications were paired with the originating section and sentence from the EMR and tabulated for rapid manual review. This facilitated exclusion of antidepressant prescriptions for other purposes such as chronic pain. Ultimately, patients who were either prescribed this medication and/or had a relevant ICD-10 diagnosis code were categorized as having depression or anxiety preoperatively.

Given that depression and anxiety are frequently comorbid with similar treatment algorithms, they were not categorized separately based on the identification of associated medication.24 The preoperative presence of depression or anxiety was determined separately for each arthoplasty for patients undergoing several arthroplasties during the study period. The cutoff for determining preoperative versus postoperative depression or anxiety was 14 days postoperatively, in order to limit induction time bias given the criteria for major depressive disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM- 5).25 Medications included amitriptyline, amoxapine, bupropion, citalopram, clomipramine, desipramine, desvenlafaxine, doxepin, duloxetine, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, imipramine, milnacipran, mirtazapine, nortriptyline, paroxetine, phenelzine, protriptyline, sertraline, tranylcypromine, trazodone, venlafaxine, vilazodone, and vortioxetine.

The study included 10,011 THAs (8,701 primary procedures, 1,310 revisions) in 8,402 patients, and 11,458 TKAs (10,466 primary procedures, 992 revisions) (Table I) in 8,511 patients. The mean age of the patients at the time of surgery was 68 years (18 to 106), their mean BMI was 31 kg/m2 (11 to 70), 1,024 patients (4.8%) actively smoked, and 12,209 (57%) were female. The mean follow-up was five years (0 to 20).

Table I.

The characteristics of the patients at the time of arthroplasty in the study.

| Characteristic | Total | No prior depression or anxiety | Prior depression or anxiety | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arthroplasties, n | 21,469 | 14,708 | 6,761 | |

| Mean age, yrs (SD) | 68 (12) | 69 (12) | 67 (13) | < 0.001 |

| Female, n (%) | 12,209 (57) | 7,495 (51) | 4,714 (70) | < 0.001 |

| Mean BMI, kg/m2 (SD) | 31 (7) | 31 (7) | 32 (7) | < 0.001 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| Active | 1,024 (4.8) | 575 (3.9) | 449 (6.6) | |

| Never/former | 13,077 (61) | 8,452 (58) | 4,625 (68) | |

| Unknown | 7,368 (34) | 5,681 (39) | 1,687 (25) | |

| Operation, n (%) | 0.001 | |||

| THA | 10,011 (47) | 6,968 (47) | 3,043 (45) | |

| TKA | 11,458 (53) | 7,740 (53) | 3,718 (55) | |

| Mean year of surgery (SD) | 2010 (5) | 2009 (5) | 2011 (5) | < 0.001 |

SD, standard deviation; THA, total hip arthroplasty; TKA, total knee arthroplasty.

Statistical analysis.

Descriptive statistics were calculated for continuous and categorical variables. Baseline characteristics were compared between those with and without preoperative depressive or anxiety disorders using the Kruskal-Wallis rank-sum test and chi-squared tests. Complications were analyzed as time-to-event outcomes using survivorship methodology, with rates estimated using Kaplan-Meier methods and compared with Cox proportional hazards with robust variance estimates. Patients were censored at the time of the event of interest or the last clinical follow-up if no event occurred. Potential confounders including age, sex, smoking, year of surgery, operating time, and BMI were examined univariately with the outcomes. The impact of these factors was then assessed using multivariable regression analysis. Changes in PROMs were compared between those with and those without preoperative depressive or anxiety disorders using paired t-tests with equal variance. Patient-assessed joint function was compared using a trend test for ordinal variables. Hazard ratios (HRs) are reported with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) and a significance level of < 0.05 was used. Analyses were conducting using R v. 4.1.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Austria) and SAS v. 9.4 (SAS Institute, USA).

Results

There were preoperative depressive and anxiety disorders in 2,609 patients (30%) who underwent primary THA and 434 patients (33.1%) who underwent revision THA. There were preoperative depressive and anxiety disorders in 3,374 patients (32.2%) who underwent primary TKA and 344 (34.7%) of those who underwent revision TKA.

Among the total of 6,761 patients who underwent arthroplasty with preoperative depressive or anxiety disorders, 5,499 (81.3%) were taking appropriate medications. A total of 1,262 (19%) were identified by diagnosis code alone, 2,187 (32%) by medication use alone, and 3,312 (49%) by both diagnosis code and medication use.

Among patients who underwent primary THA, those with depressive and/or anxiety disorders had a significantly increased risk of developing any infection (p = 0.019) (Table II; Supplementary Table 1). A similar significantly increased risk was seen in those who underwent revision THA (p = 0.017), primary TKA (p = 0.001), and revision TKA (p = 0.015). When separated between superficial infection and PJI, there was a significantly increased risk of PJI among those who underwent revision TKA (p = 0.004). However, there was no significant increase in PJI in those who underwent primary THA, revision THA, or primary TKA. The presence of preoperative depressive and anxiety disorders was associated with a significantly increased risk of superficial infection among those who underwent primary THA (p = 0.028), revision THA (p = 0.035), and primary TKA (p < 0.001), but not among those who underwent revision TKA (p = 0.234, all Cox proportional hazards with robust variance estimates).

Table II.

Summary of hazard ratios for the increased risk of complications associated with preoperative depressive or anxiety disorders (univariable analysis).

| Outcome | HR (95% Cl) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Primary THA | Revision THA | Primary TKA | Revision TKA | |

| Superficial infection | 1.8 (1.1 to 2.8) | 2.7 (1.1 to 6.8) | 2.1 (1.4 to 3.2) | 0.5 (0.1 to 2.1) |

| Periprosthetic joint infection | 1.3 (0.9 to 1.9) | 1.6 (0.9 to 2.8) | 1.4 (1.0 to 2.0) | 2.1 (1.3 to 3.4) |

| Any infection | 1.5 (1.1 to 2.0) | 1.9 (1.2 to 2.9) | 1.6 (1.2 to 2.0) | 1.8 (1.2 to 2.9) |

| Revision or re-revision | 1.7 (1.3 to 2.1) | 2.0 (1.4 to 2.8) | 1.6 (1.3 to 2.0) | 1.6 (1.1 to 2.4) |

| Reoperation | 1.6 (1.3 to 1.9) | 2.2 (1.7 to 2.9) | 1.4 (1.2 to 1.6) | 1.9 (1.4 to 2.6) |

| Nonoperative complication | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.5) | 0.8 (0.7 to 1.1) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.3) |

Cl, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; THA, total hip arthroplasty; TKA, total knee arthroplasty.

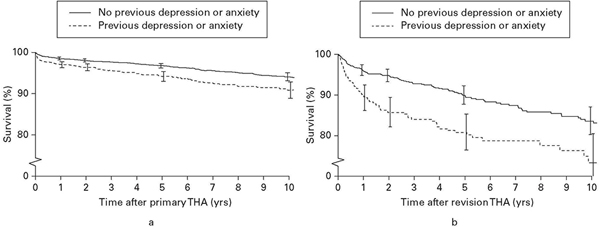

Patients with depressive or anxiety disorders had a significantly higher risk of requiring revision after primary THA compared with those without these conditions (p < 0.001; Figure 1a). There was a similar significant association with re-revision after revision THA (p = 0.001; Figure 1b). At five years postoperatively, the overall cumulative revision rate after primary THA was 4% (95% CI 3.5% to 4.5%) and after revision THA was 12.9% (95% CI 10.8% to 15.0%). After primary TKA, patients with depressive or anxiety disorders had a significantly increased risk of revision (p < 0.001; Figure 2a). There was a similar significant association after revision TKA (p = 0.026, all Cox proportional hazards with robust variance estimates; Figure 2b). At five years postoperatively, the overall cumulative revision rate after primary TKA was 3.3% (95% CI 2.9% to 3.7%) and 12.4% (95% CI 10.0% to 14.8%) after revision TKA.

Fig. 1.

a) Survivorship free of revision after primary total hip arthroplasty (THA). b) Survivorship free of re-revision after revision THA.

Fig. 2.

a) Survivorship free of revision after primary total knee arthroplasty (TKA). b) Survivorship free of re-revision after revision TKA.

There was a significantly increased risk of any reoperation among those with depressive or anxiety disorders, compared with those without, after primary THA, revision THA, primary TKA and revision TKA (all p < 0.001, Cox proportional hazards with robust variance estimates). At five years postoperatively, the overall cumulative reoperation rate after primary THA was 5.9% (95% CI 5.3% to 6.5%), 17.2% (95% CI 14.8% to 19.5%) after revision THA, 8.4% (95% CI 7.8% to 9.0%) after primary TKA, and 18.6% (95% CI 15.7% to 21.4%) after revision TKA.

Those with depressive or anxiety disorders had a significantly increased risk of nonoperative complications after primary THA (p < 0.001). There was no significantly increased risk of nonoperative complications after revision THA (p = 0.169), primary TKA (p = 0.659), and revision TKA (p = 0.789, all Cox proportional hazards with robust variance estimates). At five years postoperatively, the overall cumulative nonoperative complication rate was 15.6% (95% CI 14.7% to 16.4%) after primary THA, 22.9% (95% CI 20.4% to 25.3%) after revision THA, 14.4% (95% CI 13.7% to 15.1%) after primary TKA, and 21.1% (95% CI 18.1% to 23.9%) after revision TKA.

Potential confounding factors including age, sex, smoking status, year of surgery, operating time, and BMI were assessed for associations with each outcome in each subgroup. Multi-variable analysis accounting for these factors produced adjusted HRs comparable to those reported with univariable analysis (Table III).

Table III.

Adjusted hazard ratios for the increased risk of complications associated with preoperative depressive or anxiety disorders (multivariable analysis).

| Outcome | HR (95% Cl) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Primary THA | Revision THA | Primary TKA | Revision TKA | |

| Superficial infection | 1.5 (0.94 to 2.5) | 2.6 (0.96 to 7.1) | 2.1 (1.4 to 3.1) | 0.13 (0.02 to 0.8) |

| Periprosthetic joint infection | 1.3 (0.9 to 1.9) | 2.0 (1.1 to 3.5) | 1.3 (0.95 to 1.9) | 2.0 (1.2 to 3.3) |

| Any Infection | 1.4 (1.01 to 1.9) | 2.1 (1.3 to 3.5) | 1.5 (1.2 to 2.0) | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.5) |

| Revision or re-revision | 1.7 (1.3 to 2.1) | 1.9 (1.4 to 2.7) | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.7) | 1.5 (0.98 to 2.2) |

| Reoperation | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.9) | 2.1 (1.6 to 2.8) | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.5) | 1.7 (1.2 to 2.3) |

| Nonoperative complication | 1.3 (1.2 to 1.5) | 0.98 (0.8 to 1.3) | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.4) | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.5) |

Cl, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; THA, total hip arthroplasty; TKA, total knee arthroplasty.

The HHS increased by a mean of 36 points (standard deviation (SD) 16) from preoperatively to two years postoperatively following primary THA and 19.7 points (SD 22.5) following revision THA. The KSS increased by a mean of 38.4 points (SD 19.7) from preoperatively to two years postoperatively following primary TKA and 30 points (SD 23.2) following revision TKA. There was no statistically significant difference in this increase from preoperatively to two years postoperatively between those with and without preoperative depressive or anxiety disorders in each subgroup.

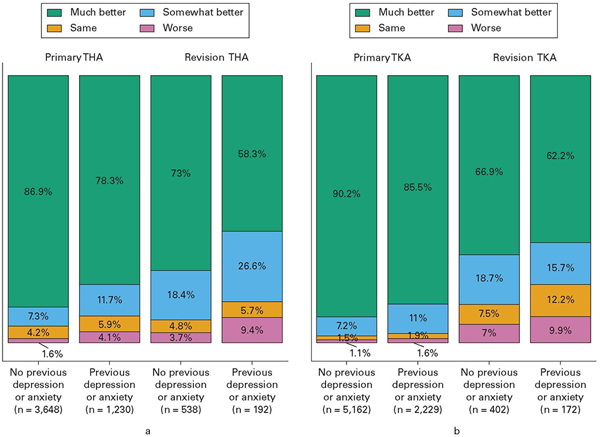

However, at two years postoperatively, patients were asked, “Compared with before your surgery, how would you rate your hip (or knee) function?” After primary THA, 3,169 patients (86.9%) without previous depressive or anxiety disorders rated their hip as “much better” compared with 963 (78.3%) among those with these conditions (p < 0.001; Figure 3a). After revision THA, 393 patients (73%) without previous depressive or anxiety disorders rated their hip as “much better” compared with 112 (58.3%) of those with these disorders (p < 0.001, both trend test for ordinal variables).

Fig. 3.

a) Satisfaction at two years after primary and revision total hip arthroplasty (THA) on a four-point scale. b) Satisfaction at two years after primary and revision total knee arthroplasty (TKA) on a four-point scale.

A total of 4,657 patients (90.2%) after primary TKA without previous depressive or anxiety disorders rated their knee as “much better” compared 1,906 (85.5%) of those with these disorders (p < 0.001; Figure 3b). A total of 269 patients (66.9%) after revision TKA without previous depressive or anxiety disorders rated their knee as “much better” compared with 107 (62.2%) of those with these disorders (p = 0.076, both trend test for ordinal variables).

Discussion

Depressive and anxiety disorders are common and have been linked with poor outcomes following THA and TKA including persistent pain, dissatisfaction, prolonged hospital stay, anaemia, and increased rates of infection.4–8,10,26 We used a population-based dataset coupled with a natural language processing algorithm to increase detection of preoperative depression or anxiety. We identified preoperative depressive and anxiety disorders in approximately one-third of patients who underwent THA and TKA. These patients had a 1.5- to two-fold increased risk of infection, revision, reoperation, and decreased satisfaction compared with those without these disorders.

The prevalence of depression and/or anxiety among patients undergoing primary THA or TKA has been reported to be between 7% and 35%, compared with between 32% and 35% in the present study.6,7,11–13 There is significant underestimation of the prevalence of depression with the use of administrative data such as diagnosis codes alone, with reported sensitivities of between 29% and 61%.27,28 Our methodology combined diagnosis codes with the use of antidepressant medication preoperatively in a large cohort of patients to maximize categorical sensitivity. Since the diagnosis codes and data about the use of medication were obtained from two years before surgery, it is possible that some patients were no longer being treated for depression or anxiety at the time of arthroplasty. Manual validation of the pharmaceutical data was important to limit overestimation related to these factors.

We found a significantly increased risk of superficial infection after primary THA, revision THA, and primary TKA in addition to an increased risk of PJI after revision TKA among patients with depressive or anxiety disorders preoperatively. Previous authors have suggested that depression and stress can alter the function of the immune system, including decreasing neutrophil proliferation and chemotaxis, and altering catecholamine and corticoid production.29,30 Immunomodulation related to depressive and anxiety disorders may explain the increased risk of infection in this cohort.31–33 It is also possible that comorbidities commonly associated with depression and anxiety may have contributed to the increased rate of infection.

We identified a substantially increased risk of all-cause revisions and reoperations among patients with depressive or anxiety disorders preoperatively. This was true for patients who underwent primary and revision THA and TKA with similar effect sizes. Yao et al14 reported a similar finding in a large mixed cohort of patients who underwent primary and revision THA and TKA, with depression increasing the risk for all-cause revision by a factor of 1.7. It is not clear why these psychological factors appear to increase the risks of requiring revision and reoperation so significantly. Preoperative depression has been associated with an increased use of opioid medication postoperatively, which may increase the risk of complications.34,35 Patients with these disorders may also have an amplified response to pain with persistent symptoms that lead surgeons to overinterpret or misinterpret their findings on examination or imaging data, leading to an increased rate of reoperation.

We found significantly worse patient-reported postoperative joint function among patients with preoperative depressive or anxiety disorders in all arthroplasty subgroups. This specific question is much more informative than the HHS or KSS, which are composite metrics of joint function. Ali et al5 reported a six-fold increased risk of dissatisfaction among patients with preoperative depression or anxiety who underwent TKA compared with those without these disorders. Our findings also support this association after revision THA and TKA. Recent authors have reported improved satisfaction and decreased narcotic usage in patients who have received psychological treatment before primary THA and TKA.15,36 Further study is needed to determine the impact of psychological intervention on objective postoperative complications.

Our findings suggest that preoperative depressive and anxiety disorders have detrimental effects on the outcome of hip and knee arthroplasty with large effect sizes. The HRs were comparable to those seen with comorbidities commonly screened for and managed, such as diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease.37,38 Thus, the identification and management of depression and anxiety preoperatively may represent a major untapped and underappreciated opportunity for orthopaedic surgeons to improve both the surgical outcomes and the overall health of up to one-third of their patients.

The study had limitations. It was a retrospective study from a tertiary care hospital and the findings may not apply to patients treated in other settings. The increased risk of complications seen in patients with preoperative depressive and anxiety disorders may be related to comorbid conditions which were not accounted for, rather than to the mental health disorder itself. While the overall cohort was large, the absolute number of infections was relatively small, which limited the power of the study to detect significant differences in these outcomes. Furthermore, we limited the cohort only to patients within the E-REP network of EMRs. This provided access to reliable longitudinal medication and diagnostic information but precluded the inclusion of many arthroplasties, and limited the power of the study.

In summary, depressive and anxiety disorders are present in approximately one-third of patients before THA and TKA, and are associated with 1.5- to two-fold increased rates of infection, revision, and reoperation, and decreased rates of satisfaction compared with patients without these disorders. These associations were remarkably similar across all subgroups of arthroplasty which we examined. The magnitude of these findings is substantial and represents an opportunity for surgeons to improve their outcomes and the overall health of their patients by the preoperative identification and management of depression and anxiety. Further study could be directed towards screening for anxiety and depression and appropriate strategies for pre- and postoperative management.

Supplementary Material

Take home message.

Depressive and anxiety disorders are present in approximately one-third of patients prior to total hip or knee arthroplasty and are associated with 1.5- to two-fold increased rates of infection, revisions, and reoperations and decreased satisfaction rates compared to patients without these disorders.

These mental health disorders represent a potential opportunity for surgeons to improve surgical outcomes and overall patient health through preoperative identification and management.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to acknowledge the Andrew A. and Mary S. Sugg Professorship in Orthopedic Research for its philanthropic support that made such research possible. The authors wish to thank members of the Mayo Clinic Total Joint Registry for collection, maintenance, and procurement of data for this study.

Funding statement:

The authors disclose receipt of the following financial or material support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was in part supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01AR73147 and P30AR76312. The study used the resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) medical records- linkage system, which is supported by the National Institute on Aging (AG 058738), by the Mayo Clinic Research Committee, and by fees paid annually by REP users. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the NIH or the Mayo Clinic.

Footnotes

ICMJE COI statement:

M. P. Abdel reports royalties from Stryker, OsteoRemedies, and Springer, all unrelated to this study. M. P. Abdel is also on the Board of Directors for AAHKS, IOEN, and Mid-A merica.

Ethical review statement:

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board under study number 17– 010548.

Supplementary material

A supplementary table is available outlining the number of each outcome measure used to calcuate the hazard ratios presented in Table II.

References

- 1.Fehring TK, Odum SM, Curtin BM, Mason JB, Fehring KA, Springer BD. Should depression be treated before lower extremity arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(10):3143–3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang F, Rao S, Baranova A. Shared genetic liability between major depressive disorder and osteoarthritis. Bone Joint Res. 2022;11(1):12–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strahl A, Kazim MA, Kattwinkel N, et al. Mid- term improvement of cognitive performance after total hip arthroplasty in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip : a prospective cohort study. Bone Joint J. 2022;104-B(3):331–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kazarian GS, Anthony CA, Lawrie CM, Barrack RL. The impact of psychological factors and their treatment on the results of total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2021;103- A(18):1744–1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ali A, Lindstrand A, Sundberg M, Flivik G. Preoperative anxiety and depression correlate with dissatisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: a prospective longitudinal cohort study of 186 patients, with 4-y ear follow- up. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(3):767–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oh C, Gold H, Slover J. Diagnosis of depression and other patient factors impacts length of stay after total knee arthroplasty. Arthroplast Today. 2020;6(1):77–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vakharia RM, Ehiorobo JO, Sodhi N, Swiggett SJ, Mont MA, Roche MW. Effects of depressive disorders on patients undergoing primary total knee arthroplasty: a matched-control analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(5):1247–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knapp P, Layson JT, Mohammad W, Pizzimenti N, Markel DC. The effects of depression and anxiety on 90- day readmission rates after total hip and knee arthroplasty. Arthroplast Today. 2021;10:175–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bourne RB, Chesworth BM, Davis AM, Mahomed NN, Charron KDJ. Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: who is satisfied and who is not? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(1):57–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duivenvoorden T, Vissers MM, Verhaar JAN, et al. Anxiety and depressive symptoms before and after total hip and knee arthroplasty: a prospective multicentre study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21(12):1834–1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellis HB, Howard KJ, Khaleel MA, Bucholz R. Effect of psychopathology on patient- perceived outcomes of total knee arthroplasty within an indigent population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94- A(12):e84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gold PA, Garbarino LJ, Anis HK, et al. The cumulative effect of substance abuse disorders and depression on postoperative complications after primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(6S):S151–S157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pan X, Wang J, Lin Z, Dai W, Shi Z. Depression and anxiety are risk factors for postoperative pain- related symptoms and complications in patients undergoing primary total knee arthroplasty in the United States. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34(10):2337–2346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yao JJ, Maradit Kremers H, Kremers WK, Lewallen DG, Berry DJ. Perioperative inpatient use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors is associated with a reduced risk of THA and TKA revision. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2018;476(6):1191–1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwartz AM, Wilson JM, Farley KX, Roberson JR, Guild GN 3rd, Bradbury TL Jr. Modifiability of depression’s impact on early revision, narcotic usage, and outcomes after total hip arthroplasty: the impact of psychotherapy. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(10):2904–2910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh JA, Lewallen DG. Depression in primary TKA and higher medical comorbidities in revision TKA are associated with suboptimal subjective improvement in knee function. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rocca WA, Yawn BP, St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Melton LJ 3rd. History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project: half a century of medical records linkage in a US population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(12):1202–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rocca WA, Grossardt BR, Brue SM, et al. Data Resource Profile: Expansion of the Rochester Epidemiology Project medical records-linkage system (E- REP). Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(2):368–368j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris WH. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51-A(4):737–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Insall JN, Dorr LD, Scott RD, Scott WN. Rationale of the Knee Society clinical rating system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;248(248):13–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization. ICD-10: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems: tenth revision. 2nd edition. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22.No authors listed. Medtagger. GitHub. 2021. https://github.com/medtagger/MedTagger (date last accessed 29 March 2023). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pathak J, Murphy SP, Willaert BN, et al. Using RxNorm and NDF-RT to classify medication data extracted from electronic health records: experiences from the Rochester Epidemiology Project. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2011;2011:1089–1098. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gorman JM. Comorbid depression and anxiety spectrum disorders. Depress Anxiety. 1996;4(4):160–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th edition. Arlington, Virginia, USA: American Psychiatric Publishing, a division of the American Psychiatric Association, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khatib Y, Madan A, Naylor JM, Harris IA. Do psychological factors predict poor outcome in patients undergoing TKA? A systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(8):2630–2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fiest KM, Jette N, Quan H, et al. Systematic review and assessment of validated case definitions for depression in administrative data. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(1):289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doktorchik C, Patten S, Eastwood C, et al. Validation of a case definition for depression in administrative data against primary chart data as a reference standard. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cañas-González B, Fernández-Nistal A, Ramírez JM, Martínez-Fernández V. Influence of stress and depression on the immune system in patients evaluated in an anti- aging unit. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leonard BE. The concept of depression as a dysfunction of the immune system. Curr Immunol Rev. 2010;6(3):205–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghoneim MM, O’Hara MW. Depression and postoperative complications: an overview. BMC Surg. 2016;16:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raison CL, Miller AH. Pathogen-host defense in the evolution of depression: insights into epidemiology, genetics, bioregional differences and female preponderance. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42(1):5–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith DJ, Court H, McLean G, et al. Depression and multimorbidity: a cross-sectional study of 1,751,841 patients in primary care. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(11):1202–1208; . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Etcheson JI, Gwam CU, George NE, Virani S, Mont MA, Delanois RE. Patients with major depressive disorder experience increased perception of pain and opioid consumption following total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(4):997–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Torres-Claramunt R, Hinarejos P, Amestoy J, et al. Depressed patients feel more pain in the short term after total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25(11):3411–3416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Geng X, Wang X, Zhou G, et al. A Randomized controlled trial of psychological intervention to improve satisfaction for patients with depression undergoing TKA: a 2- year follow- up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2021;103- A(7):567–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Na A, Middleton A, Haas A, Graham JE, Ottenbacher KJ. Impact of diabetes on 90-d ay episodes of care after elective total joint arthroplasty among Medicare beneficiaries. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020;102- A(24):2157–2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bozic KJ, Lau E, Kurtz S, Ong K, Berry DJ. Patient- related risk factors for postoperative mortality and periprosthetic joint infection in medicare patients undergoing TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(1):130–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.