Background:

This study aimed to analyze the differences in the epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in children hospitalized in 2021, when the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 variants B.1.1.7 (alpha) and B.1.617.2 (delta) dominated, compared with 2020.

Methods:

In this multicenter study based on the pediatric part of the national SARSTer register (SARSTer-PED), we included 2771 children (0–18 years) with COVID-19 diagnosed between March 1, 2020, and December 31, 2021, from 14 Polish inpatient centers. An electronic questionnaire, which addressed epidemiologic and clinical data, was used.

Results:

Children hospitalized in 2021 were younger compared with those reported in 2020 (mean 4.1 vs. 6.8 years, P = 0.01). Underlying comorbidities were reported in 22% of the patients. The clinical course was usually mild (70%). A significant difference in the clinical course assessment between 2020 and 2021 was found, with more asymptomatic patients in 2020 and more severely ill children in 2021. In total, 5% of patients were severely or critically ill, including <3% of the participants in 2020 and 7% in 2021. The calculated mortality rate was 0.1% in general and 0.2% in 2021.

Conclusion:

Infections with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 variants alpha and delta lead to a more severe course of COVID-19 with more pronounced clinical presentation and higher fatality rates than infection with an original strain. Most of the children requiring hospitalization due to COVID-19 do not have underlying comorbidities.

Keywords: children, complications, coronavirus disease 2019, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, variants of concern

According to the available data, until the end of 2021, there have been over 4.1 million coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases reported in Poland, with almost 100,000 deaths.1 The exact proportion of pediatric cases remains unknown. In the US, it is estimated that children account for 19% of all cases of COVID-19, with a total rate of 17,000 per 100,000.2 Observations available from the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic showed that compared with adult patients, and in contrast to other respiratory viruses, children infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) have a milder clinical course of the disease.3–8 Approximately one-third of pediatric COVID-19 cases were asymptomatic.9,10 According to UNICEF data, children and adolescents account for 0.4% of deaths related to COVID-19.11 Among them, 42% were children 0–9 years of age, and 58% were teenagers (10–19 years). Bundle et al.,9 who analyzed risks of severe outcomes in over 820,000 symptomatic children with COVID-19 from 10 European Union (EU) countries between August 2020 and October 2021, showed that severe outcomes were rare, with 1.2% of patients requiring hospitalization, 0.08% treated in the intensive care unit and 84 (0.01%) who died. According to this study, since January 2021, pediatric patients have represented an increasing proportion of reported cases and hospital admissions due to COVID-19.9 Despite the fact that the number of pediatric cases increased with the emergence of more transmissible SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern (VOCs), including alpha, delta and omicron, children and young adolescents suffering from COVID-19 have still received much less attention.12 Thus, several questions, for example, which children are more vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2 infection, whether any factors may predict a more severe clinical course and whether the disease had changed or if it had a similar clinical picture during subsequent waves of the pandemic related to infections with VOCs, remain unanswered. In particular, the role of different SARS-CoV-2 variants on the clinical severity of COVID-19 in children and adolescents is not fully investigated. Thus, in this study, we aimed to analyze the differences in clinical and epidemiologic characteristics of COVID-19 in children hospitalized in 2021, when the emergence of VOCs alpha and delta was reported compared with 2020, when nonvariant SARS-CoV-2 was dominant (III–IV vs. I–II waves of the pandemic, respectively).

MATERIAL AND METHODS

In this multicenter study based on the pediatric part of the national SARSTer register (SARSTer-PED), we included children and adolescents (0–18 years) hospitalized with COVID-19, diagnosed between March 1, 2020, and December 31, 2021. Epidemiologic and clinical data were collected from 14 Polish inpatient centers dedicated to pediatric patients with COVID-19, which reported their consecutive cases using an electronic questionnaire. Diagnosis of COVID-19 was based on a positive real-time polymerase chain reaction or second-generation antigen testing on a nasopharyngeal swab performed in certified diagnostics laboratories. Epidemiologic data included known exposure to a person with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection (in the household or otherwise), the duration of symptoms before presentation, history of immunization against COVID-19 and any comorbidity (with obesity defined as body mass index ≥ the 95th percentile for age/sex). All symptoms at the time of admission and during hospitalization were recorded. For this study, we divided the analyzed period into two parts: March 1, 2020–December 31, 2020 (corresponding to the first and the second waves of the pandemic, when nonvariant, wild SARS-CoV-2 dominated) and January 1, 2021–December 31, 2021 (corresponding to the third and fourth waves, with a dominance of B.1.1.7 – alpha, and B.1.617.2 – delta variants).

We defined the clinical course of COVID-19 as follows: grade 0 – asymptomatic, when no complaints or symptoms were present, and no abnormalities were found on physical examination; grade 1 – mild, when signs of upper respiratory tract infection were present, with or without fever and other complaints, but without pneumonia; grade 2 – moderate, when pneumonia without hypoxemia was present; grade 3 – severe, when pneumonia manifesting with dyspnea and oxygen saturation <94% was present; and grade 4 – critical, when acute respiratory distress syndrome, shock or any organ failure occurred. The same classification was used previously.6

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using MedCalc Statistical Software version 20.116 (MedCalc, Ostend, Belgium, https://www.medcalc.org). Categorical variables were presented as numbers with percentages and were compared using the χ2 test. Continuous variables were presented as the medians with interquartile ranges and were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. To identify predictors of subsequent clinical symptoms of COVID-19 in the study group, regression analyses were conducted. Multiple regression was performed with the following variables (candidate predictors) entered into the model irrespective of the results of the univariate analysis: sex, age, year (2021 vs. 2020) and presence of any comorbidity. Separate models were constructed for different symptoms of COVID-19. After entering all the variables into the model, those variables that showed the least significant associations were subsequently excluded until all variables remained significant (P < 0.05). The results were presented as odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. Results with CI not including 1.0 were considered statistically significant.

Ethical Statement

This study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards presented in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. It was approved by the local ethics committee of the Regional Medical Chamber in Warsaw (No KB/1270/20; date of approval: 3 April 2020).

RESULTS

Study Group

We included 2771 patients with COVID-19: 1025 hospitalized in 2020, and 1746 hospitalized in 2021. The numbers of patients diagnosed in the subsequent months of the observation period are presented in Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/INF/E997. The baseline demographic and epidemiologic characteristics of the study group are shown in Table 1. Children hospitalized in 2021 were younger than those reported in 2020 (mean 4.1 vs. 6.8 years, P = 0.01), and the proportion of infants was also higher (37% vs. 28%, P < 0.0001). No differences in children’s sex were observed in 2020, whereas in 2021 there was a significant predominance of males (56% vs. 44%). Among patients with confirmed previous contact with a person infected with SARS-CoV-2, household contact was most commonly reported (in 40% and 52% of patients in 2021 and 2020, respectively). Only 11 (0.5%) of the participants in 2021 were previously vaccinated against COVID-19, including 10 who received 2 doses, and 1 after 1 dose. In total 611 (22%) patients were suffering from comorbidities (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/INF/E998). Both duration of symptoms before admission and the duration of hospitalization were longer in 2021 compared with 2020 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Demographic and Epidemiologic Characteristics of the Study Group

| Characteristics | Whole Study Group | Children Hospitalized in 2020 | Children Hospitalized in 2021 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 2771 | 1025 | 1746 | ||

| Age (years) | Mean ± SD Median (IQR) |

5.6 ± 4.8 4.0 (2–8) |

6.8 ± 6.0 5.0 (0–12) |

4.1 ± 5.3 4 (3–6) |

0.01 |

| Infants | 921 (33) | 289 (28) | 651 (37) | <0.0001 | |

| Sex | Male/female | 1486 (54)/1285 (46) | 516 (50)/509 (50) | 970 (56)/776 (44) | 0.008 |

| Contact with an infected person | Confirmed | 1382 (50) | 572 (56) | 810 (46) | <0.0001 |

| Household Other |

1245 (45) 137 (5) |

534 (52) 38 (4) |

711 (40) 99 (6) |

<0.0001 0.02 |

|

| Vaccination against COVID-19 | Yes | 11 (0.3) | 0 | 11 (0.5) | 0.01 |

| Comorbidity | Yes | 611 (22) | 231 (23) | 380 (22) | 0.63 |

| Duration of symptoms before admission | Days, median (IQR) | 3 (1–5) | 2 (1–4) | 3 (1–5) | <0.0001 |

| Duration of hospitalization | Days, median (IQR) Days, range >7 days |

4 (2–6) 1–88 468 (17) |

3 (1–6) 1–88 176 (17) |

4 (3–6) 1–41 292 (17) |

<0.0001 |

Data are presented as numbers (%) or medians (IQR), respectively.

IQR indicates interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

Clinical Presentation

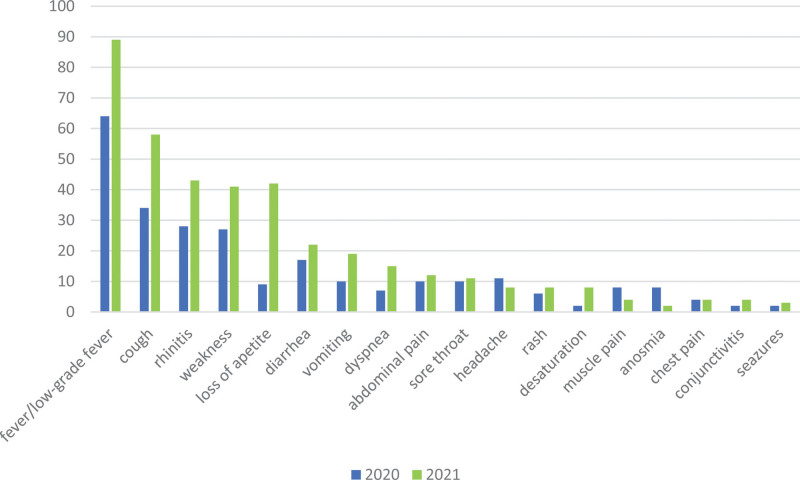

The clinical presentation of COVID-19 in the analyzed period is shown in Table, Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/INF/E999. Fever (>38°C) was the most frequently observed symptom during the whole studied period. However, in 2021 it was more often reported compared with 2020 (67% vs. 50%, P < 0.0001). A similar observation was made for other symptoms, including cough, rhinitis, weakness, loss of appetite, diarrhea, vomiting, dyspnea and desaturation (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/INF/E999 and Fig. 1). By contrast, headache, muscle pain and anosmia were among the less frequently reported symptoms during the third and fourth waves of the pandemic. Multiple regression analysis confirmed that the prevalence of most COVID-19 symptoms was associated with the patient’s age and the wave of the pandemic (Table 2). Any symptom from the respiratory tract was observed in 1688/2771 (61%) of patients, including 475/1025 (46%) in 2020, and 1213/1746 (69%) in 2021 (P < 0.0001). Among all 2771 patients, 1332 (48%) demonstrated gastrointestinal symptoms, 314 (31%) in 2020 and 1018 (58%) in 2021 (P < 0.0001). COVID-related pneumonia was diagnosed in 539 (19%) patients, 154 (15%) in 2020 and 385 (22%) in 2021 (P < 0.0001). Chest radiographs revealed COVID-associated radiologic lesions (bilateral patchy consolidations and ground-glass opacities with a peripheral and lower lung predominance, often bilateral) in 502 (18%) participants, including 140 (14%) during 2020 and 362 (21%) in 2021 (P < 0.0001).

FIGURE 1.

Comparison of the clinical presentation of COVID-19 in children hospitalized in 2020/2021. Data are presented as proportions (%) of children presenting with subsequent symptoms.

TABLE 2.

Factors Influencing Clinical Course of COVID-19 (Multivariate Analysis)

| Predictors Symptom | Sex (for Male Sex) | Age (Years) | Year (2021 vs. 2020) | Comorbidities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fever | 1.21 (1.03–1.42) | 0.94 (0.93–0.95) | 1.73 (1.47–2.05) | 0.77 (0.63–0.93) |

| Cough | – | – | 2.64 (2.25–3.11) | – |

| Rhinitis | – | 0.95 (0.94–0.96) | 1.68 (1.42–2.00) | – |

| Weakness | – | 1.05 (1.04–1.07) | 2.30 (1.92–2.75) | – |

| Loss of appetite | – | 0.93 (0.92–0.95) | 5.8 (4.55–7.39) | – |

| Diarrhea | – | 0.95 (0.93–0.96) | – | – |

| Vomiting | – | – | 1.89 (1.49–2.39) | – |

| Dyspnea | – | 1.06 (1.04–1.08) | 2.51 (1.89–3.34) | 1.64 (1.27–2.11) |

| Abdominal pain | – | 1.06 (1.04–1.08) | 1.43 (1.11–1.85) | – |

| Sore throat | – | 1.12 (1.10–1.14) | 1.40 (1.07–1.84) | – |

| Headache | 0.57 (0.42–0.77) | 1.26 (1.23–1.30) | 1.42 (1.05–1.93) | 0.53 (0.38–0.75) |

| Rash | – | 0.95 (0.93–0.98) | – | – |

| Muscle pain | – | 1.24 (1.20–1.29) | – | – |

| Anosmia | 0.54 (0.35–0.83) | 1.35 (1.28–1.42) | 0.44 (0.28–0.68) | 0.43 (0.26–0.71) |

| Conjunctivitis | 1.64 (1.12–2.41) | – | – | – |

| Seizures | – | – | – | 3.04 (1.92–4.79) |

The results were presented as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). Results with CI not including 1.0 were considered statistically significant.

Multiple regression was performed with the following variables (candidate predictors) entered into the model irrespective of the results of the univariate analysis: sex, age, year (2021 vs. 2020), and presence of any comorbidity. Separate models were constructed for different symptoms of COVID-19. After entering all the variables into the model, those variables that showed the least significant associations were subsequently excluded until all variables remained significant (P < 0.05).

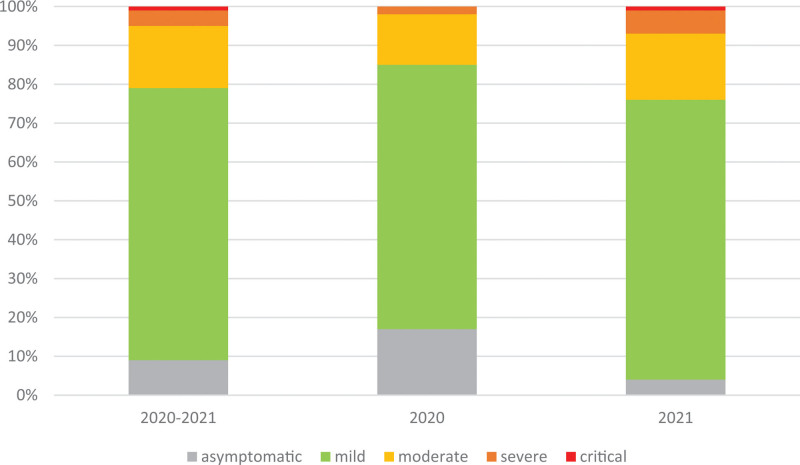

Clinical Course of COVID-19

The clinical course of COVID-19 in our cohort was most frequently described as mild (70%). There was a significant difference in the clinical course assessment between 2020 and 2021, with more asymptomatic patients in 2020 (admitted mainly during the first weeks of the pandemic for epidemiologic reasons) and more severely ill children in 2021 (Table 3, Fig. 2). In total, 5% of patients were reported as severely or critically ill (grades 3–4), including less than 3% of the participants hospitalized in 2020 and 7% in 2021. Three patients, all hospitalized in 2021, died due to COVID-19 (they all had severe underlying comorbidities, including genetic anomalies, pulmonary hypertension, congenital heart defect, pulmonary disease and childhood cerebral palsy). Thus, the calculated mortality rate was 0.1% in general and 0.2% in 2021.

TABLE 3.

Clinical Course of COVID-19

| Grade | Whole Group (2771) | Children Hospitalized in 2020 (1025) | Children Hospitalized in 2021 (1746) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 252 (9) | 175 (17) | 77 (4) | <0.0001 |

| 1 | 1940 (70) | 694 (68) | 1246 (72) | |

| 2 | 434 (16) | 134 (13) | 300 (17) | |

| 3 | 116 (4) | 19 (2) | 97 (6) | |

| 4 | 29 (1) | 3 (<1) | 26 (1) |

Grade 0, asymptomatic; Grade 1, mild (without pneumonia); Grade 2, moderate (pneumonia without desaturation); Grade 3, severe (pneumonia with desaturation); Grade 4, critical (acute respiratory distress syndrome - ARDS, shock, organ failure).

Data are presented as numbers (%).

FIGURE 2.

Proportion of children with different clinical grading of COVID-19 in 2020 and 2021.

Treatment

Most patients were treated symptomatically. Only a small proportion of children was receiving the anti-SARS-CoV-2 treatment, including remdesivir, tocilizumab and baricitinib (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/INF/E1000). A significant number of patients (25% in 2020 and 45% in 2021) received empirical antibiotics due to accompanying bacterial infections. In 2021, there was a significant increase in the proportion of children requiring oxygen therapy (including high-flow nasal oxygen), mechanical ventilation, as well as treatment in the intensive care unit (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/INF/E1000).

DISCUSSION

It was shown that the clinical picture of COVID-19 may vary depending on the circulating strain of SARS-CoV-2.13–16 The new emerging variants are easier transmittable and may lead to higher rates of hospitalization.16 According to the available data, in 2020, SARS-CoV-2 nonvariant (wild) strains were dominant in Poland. In contrast, in 2021, VOCs appeared, with alpha variant (B.1.1.7) dominating in the first half of 2021, and delta (B.1.617.2) in the second part of 2021.17 In this study, we present significant differences in epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of COVID-19 in 2771 patients from 14 pediatric inpatient settings in Poland during both periods.

Patients hospitalized in 2021 were younger than those in 2020, and the proportion of infants increased significantly from 26% in 2020 to 37% in 2021. This observation was similar to the study on the Ukrainian cohort, in which the share of infants and children 1–5 years of age significantly increased during subsequent waves of the pandemic from June 2020 to February 2022.13 In their study, no significant differences were reported in the gender structure, whereas in our group, a significant predominance of male patients (56% vs. 44%) was noticed in 2021. Only 11 patients in our cohort had been vaccinated against COVID-19 before admission. This may reflect the fact that by the end of 2021, only 15.2% (range: 1.0–29.9%) of children younger than 18 years in the EU and European Economic Area had been fully vaccinated against COVID-19.18 In addition, we included only hospitalized children, and vaccination should have protected patients against severe disease and, thus against hospitalization.

Half of our cohort reported confirmed contact with a person infected with SARS-CoV-2 before admission. In the vast majority of cases, these children were infected by a family member, and only 5% of participants reported other than household contact with the infection, mainly at a nursery, preschool or school. This observation was similar to the Ukrainian cohort, where contact with an infected family member was considered as a source of infection for 62.5–70.9% of patients according to the wave of the pandemic.13 In addition, the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission to and from a child in schools and nurseries appears to be low.12 Data analysis of 783 US schools performed at the time of delta strain predominance showed that the risk of within-school COVID-19 transmission was lower than that observed in the community.19

Twenty-two percent of our patients suffered from comorbidities, with obesity as the most common, particularly among children hospitalized in 2021. Still, the overall proportion of hospitalized children with comorbidities did not differ between 2020 and 2021. Quintero et al.16 demonstrated that the presence of underlying conditions, especially obesity, but not the infecting variant, were associated with worse clinical outcomes of COVID-19. In the study by Bundle et al.,9 analyzing data from 10 EU Countries, with data on comorbidities in 210,008 pediatric cases, it was demonstrated that the adjusted odds for hospitalization, intensive care unit (ICU) admission and death were 7, 9 and 27 times higher, respectively, among children with comorbidities compared with cases with no underlying disease.9 Analogous observations were made in the previous reports from our register.20 However, the authors highlighted that over 83% of children hospitalized with COVID-19 did not have any comorbidity. A similar observation was made in our cohort, which in 78% constituted of previously healthy children.

The spectrum of clinical manifestations of COVID-19 in the pediatric population is broad and ranges from asymptomatic to severe disease. Although the effects of SARS-CoV-2 infections are more pronounced in adults, severe outcomes in children are also possible.16,21 The results of this study confirm the previous observations on the generally mild clinical course of COVID-19 in pediatric populations with fever, cough and rhinitis as the most commonly occurring symptoms.9,22 However, significant differences in the clinical presentation and severity of the disease were revealed when we compared patients admitted in 2021 to 2020. The prevalence of all of the clinical symptoms of COVID-19, except for headache, muscle pain and anosmia, was higher in 2021, comparable with the results presented by other authors.13 The severe and critical course of the disease was reported in 7% of patients hospitalized in 2021 vs. <3% in 2020, indicating that SARS-CoV-2 variants B.1.1.7 (alpha) and B.1.617.2 (delta) are associated with more severe course of COVID-19 in children. This observation confirms previous reports of other authors that VOCs, in particular variant delta, were associated with more severe disease, with a significant proportion of pediatric patients with severe manifestations infected with this variant.13,16 The duration of hospitalization in our cohort was significantly longer for patients hospitalized in 2021 compared with 2020, which is comparable with the results obtained by Quintero et al.16 In their cohort, 27% of patients required treatment in ICU, which is significantly higher compared with our study, in which only 1% of children were treated in ICU, mostly in 2021. The case fatality rate in our cohort was 0.1%: 0 In 2020 and 0.2% in 2021, which confirms the influence of infections with VOCs on the more severe course of the disease. These results are similar to the observations of other authors, who reported mortality cases in children with COVID-19 infected in periods when alpha and delta strains dominated.9,16 The fatality rate in our cohort is, however, higher than 0.01% documented by Bundle et al.,9 who analyzed COVID-19 outcomes in over 820,000 children between August 2020 and October 2021.9

Significantly more children hospitalized in 2021 presented with dyspnea and desaturation compared with 2020, which resulted in an increased proportion of patients requiring oxygen therapy (8% vs. 2%), high-flow nasal oxygen (1% vs. <1%) and mechanical ventilation (1% vs. 0). These numbers are, however, much lower compared with presented by Quintero et al.,16 who documented the need for oxygen supplementation in almost 47% of their patients. The proportion of children treated with antiviral agents, mainly remdesivir, was low but increased from <1% in 2020 to 3% in 2021 (P < 0.0001). This may result from the generally mild course of the disease in the studied group, as well as the fact, that remdesivir has not been licensed yet in Europe for children younger than 12 years, and weighing less than 40 kg.23 Data on the use of remdesivir in pediatric patients are limited, but their results are encouraging.24

Our study is limited by the fact that it had been conducted in hospital settings, and the spectrum of pediatric COVID-19 may have been affected by the patient population, representing more severely ill patients. In addition, the indications for hospitalization differed between 2020 and 2021, as in the first months of the pandemic, testing for SARS-CoV-2 infection was available in Poland, mainly in hospital settings; thus, children with suspected SARS-CoV-2 infection were referred to the hospital for confirmation of the infection. Later, children with SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed in primary care, were referred to the hospital for clinical indications, which may also explain the higher proportion of asymptomatic patients in 2020 compared with 2021. In addition, a major influence was the approach of the doctors. The initial panic of the early days of the pandemic was replaced by tameness. Many patients were referred to COVID-19 wards because they required hospitalization for other reasons and had tested positive for COVID-19. Second, we did not verify the virus strain by molecular diagnostics methods, as this testing is not available for clinical purposes. However, we based our results on the available objective epidemiologic datasets. In addition, to the best of our knowledge, we present one of the most prominent pediatric national European cohorts documenting the differences in COVID-19 clinical presentation in the subsequent waves of the pandemic.

In conclusion, based on our experience, infections with SARS-CoV-2 variants alpha and delta lead to a more severe course of COVID-19 with more pronounced clinical presentation and higher fatality rates compared with infection with an original strain. Most of the children requiring hospitalization due to COVID-19 do not have underlying comorbidities. Thus, further studies are needed to find predictors of severe COVID-19 in pediatric patients.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This study was funded by the Medical Research Agency, grant number 2020/ABM/COVID-19/PTEILCHZ and the Polish Association of Epidemiologists and Infectiologists.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (www.pidj.com).

Contributor Information

Ewa Talarek, Email: emajda@lodz.home.pl.

Małgorzata Pawłowska, Email: m.pilarczyk@wsoz.pl.

Anna Mania, Email: agorczyca@szpitaljp2.krakow.pl.

Barbara Hasiec, Email: g.b.szczepanski@onet.eu.

Elżbieta Żwirek-Pytka, Email: ezwirek@wp.pl.

Magdalena Stankiewicz, Email: magdalena.marczynska@wum.edu.pl.

Martyna Stani, Email: martyna.stani@vp.pl.

Paulina Frańczak-Chmura, Email: franczak_paulina@wp.pl.

Leszek Szenborn, Email: leszek.szenborn@umed.wroc.pl.

Izabela Zaleska, Email: iza.orlinska@gmail.com.

Joanna Chruszcz, Email: zadrozna@spwsz.szczecin.pl.

Ewa Majda-Stanisławska, Email: emajda@lodz.home.pl.

Urszula Dryja, Email: urszuladryja@gmail.com.

Kamila Gąsiorowska, Email: kamila.gasiorowska2@gmail.com.

Magdalena Figlerowicz, Email: magdalena.marczynska@wum.edu.pl.

Katarzyna Mazur-Melewska, Email: domanskakatarzyna@gmail.com.

Kamil Faltin, Email: FaltinKamil@interia.pl.

Przemysław Ciechanowski, Email: przciechanowski@spwsz.szczecin.pl.

Joanna Łasecka-Zadrożna, Email: zadrozna@spwsz.szczecin.pl.

Józef Rudnicki, Email: rudnicki@spwsz.szczecin.pl.

Barbara Szczepańska, Email: g.b.szczepanski@onet.eu.

Ilona Pałyga-Bysiecka, Email: bysiecka@gmail.com.

Ewelina Rogowska, Email: erogowska1@gmail.com.

Dagmara Hudobska-Nawrot, Email: dagmarah1989@gmail.com.

Katarzyna Domańska-Granek, Email: domanskakatarzyna@gmail.com.

Adam Sybilski, Email: adam.sybilski@cskmswia.pl.

Izabela Kucharek, Email: iza.orlinska@gmail.com.

Justyna Franczak, Email: korzybska.justyna@gmail.com.

Małgorzata Sobolewska-Pilarczyk, Email: m.pilarczyk@wsoz.pl.

Ernest Kuchar, Email: ernest.kuchar@wum.edu.pl.

Michał Wronowski, Email: wronowski.m@gmail.com.

Maria Paryż, Email: mwegrzynek@wim.mil.pl.

Bolesław Kalicki, Email: kalicki@wim.mil.pl.

Kacper Toczyłowski, Email: kacper.toczylowski@umb.edu.pl.

Artur Sulik, Email: artur.sulik@umb.edu.pl.

Sławomira Niedźwiecka, Email: sniedzwiecka@szpitalepomorskie.eu.

Anna Gorczyca, Email: agorczyca@szpitaljp2.krakow.pl.

Magdalena Marczyńska, Email: magdalena.marczynska@wum.edu.pl.

REFERENCES

- 1.Worldometers COVID-19 Data. Available at: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/poland/. Accessed November 5, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Academy of Pediatrics. Children and COVID-19: State-Level Data Report. 2022. Available at: https://www.aap.org/. Accessed November 5, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu X, Zhang L, Du H, et al. ; Chinese Pediatric Novel Coronavirus Study Team. SARS-CoV-2 infection in children. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1663–1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Team CC-R. Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Children - United States, February 12-April 2, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:422–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parri N, Lenge M, Buonsenso D; Coronavirus Infection in Pediatric Emergency Departments (CONFIDENCE) Research Group. Children with Covid-19 in pediatric emergency departments in Italy. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:187–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pokorska-Spiewak M, Talarek E, Popielska J, et al. Comparison of clinical severity and epidemiological spectrum between coronavirus disease 2019 and influenza in children. Sci Rep. 2021;11:5760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zimmermann P, Curtis N. Why does the severity of COVID-19 differ with age?: understanding the mechanisms underlying the age gradient in outcome following SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2022;41:e36–e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Group ICC. COVID-19 symptoms at hospital admission vary with age and sex: results from the ISARIC prospective multinational observational study. Infection. 2021;49:889–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bundle N, Dave N, Pharris A, et al. ; Study group members. COVID-19 trends and severity among symptomatic children aged 0-17 years in 10 European Union countries, 3 August 2020 to 3 October 2021. Euro Surveill. 2021;26:2101098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qi K, Zeng W, Ye M, et al. Clinical, laboratory, and imaging features of pediatric COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltim). 2021;100:e25230e25230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.UNICEF data: Monitoring the situation of children and women. Available at: https://data.unicef.org/covid-19-and-children/. Accessed November 5, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Götzinger F, Strenger V. The role of children and young people in the transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2022;41:e172–e174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seriakova I, Yevtushenko V, Kramarov S, et al. Clinical course of COVID-19 in hospitalized children of Ukraine in different pandemic periods. Eur Clin Respir J. 2022;9:2139890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyer M, Holfter A, Ruebsteck E, et al. The alpha variant (B.1.1.7) of SARS-CoV-2 in children: first experience from 3544 nucleic acid amplification tests in a cohort of children in Germany. Viruses. 2021;13:1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sheng JF, Shao L, Wang YL. Clinical features of children with coronavirus disease 2019 caused by Delta variant infection. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. 2021;23:1267–1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quintero AM, Eisner M, Sayegh R, et al. Differences in SARS-CoV-2 clinical manifestations and disease severity in children and adolescents by infecting variant. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022;28:2270–2280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.GISAID Database. Available at: https://nextstrain.org/groups/neherlab/ncov/poland. Accessed November 5, 2022.

- 18.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). COVID-19 vaccine tracker. Stockholm: ECDC. Available at: https://vaccinetracker.ecdc.europa.eu/public/extensions/COVID-19/vaccine-tracker.html#age-group-tab. Accessed November 5, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boutzoukas AE, Zimmerman KO, Benjamin DK, et al. School safety, masking, and the delta variant. Pediatrics. 2021;149:e2021054396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mania A, Pokorska-Śpiewak M, Figlerowicz M, et al. Pneumonia, gastrointestinal symptoms, comorbidities, and coinfections as factors related to a lengthier hospital stay in children with COVID-19-analysis of a paediatric part of Polish register SARSTer. Infect Dis (Lond). 2022;54:196–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mania A, Faltin K, Mazur-Melewska K, et al. Clinical picture and risk factors of severe respiratory symptoms in COVID-19 in children. Viruses. 2021;13:2366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pokorska-Śpiewak M, Talarek E, Mania A, et al. Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of 1283 pediatric patients with coronavirus disease 2019 during the first and second waves of the pandemic-results of the pediatric part of a multicenter polish register SARSTer. J Clin Med. 2021;10:5098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.European Medicines Agency. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/veklury. Accessed November 5, 2022.

- 24.Goldman DL, Aldrich ML, Hagmann SHF, et al. Compassionate Use of remdesivir in children with severe COVID-19. Pediatrics. 2021;147:e2020047803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.