Abstract

[18F]3-fluoro-4-aminopyridine ([18F]3F4AP) is a positron emission tomography (PET) tracer for imaging demyelination based on the multiple sclerosis drug 4-aminopyridine (4AP, dalfampridine). This radiotracer was found to be stable in rodents and nonhuman primates imaged under isoflurane anesthesia. However, recent findings indicate that its stability is greatly decreased in awake humans and mice. Since both 4AP and isoflurane are metabolized primarily by cytochrome P450 enzymes, particularly cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily E member 1 (CYP2E1), we postulated that this enzyme may be responsible for the metabolism of 3F4AP. Here, we investigated the metabolism of [18F]3F4AP by CYP2E1 and identified its metabolites. We also investigated whether deuteration, a common approach to increase the stability of drugs, could improve its stability. Our results demonstrate that CYP2E1 readily metabolizes 3F4AP and its deuterated analogs and that the primary metabolites are 5-hydroxy-3F4AP and 3F4AP N-oxide. Although deuteration did not decrease the rate of the CYP2E1-mediated oxidation, our findings explain the diminished in vivo stability of 3F4AP compared with 4AP and further our understanding of when deuteration may improve the metabolic stability of drugs and PET ligands.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT

The demyelination tracer [18F]3F4AP was found to undergo rapid metabolism in humans, which could compromise its utility. Understanding the enzymes and metabolic products involved may offer strategies to reduce metabolism. Using a combination of in vitro assays and chemical syntheses, this report shows that cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP2E1 is likely responsible for [18F]3F4AP metabolism, that 4-amino-5-fluoroprydin-3-ol (5-hydroxy-3F4AP, 5OH3F4AP) and 4-amino-3-fluoropyridine 1-oxide (3F4AP N-oxide) are the main metabolites, and that deuteration is unlikely to improve the stability of the tracer in vivo.

Introduction

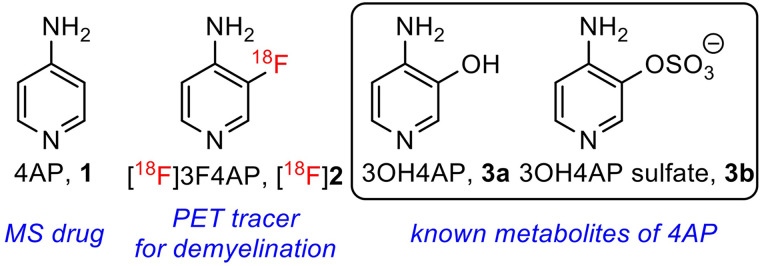

[18F]3-fluoro-4-aminopyridine ([18F]3F4AP, [18F]2) is a positron emission tomography (PET) radiotracer for imaging demyelination based on the multiple sclerosis drug 4-aminopyridine (4AP, dalfampridine, 1) (Brugarolas et al., 2018) (Fig. 1). Previous PET imaging studies with [18F]3F4AP in rodents and nonhuman primates have shown that this tracer is highly sensitive to demyelinated lesions in the brain (Brugarolas et al., 2018; Guehl et al., 2021), which has led to the recent translation to human studies (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04699747). In monkeys scanned under isoflurane anesthesia, the tracer was found to have minimal protein binding (plasma free fraction = 0.92 ± 0.3) and to be very stable (>90% parent fraction remaining 2 hours postinjection) (Guehl et al., 2021). However, recent findings in humans scanned without anesthesia show that less than 50% parent remains in circulation 1 hour after intravenous administration (Brugarolas et al., 2023), and a study in mice that received [18F]3F4AP awake or under isoflurane showed that nonanesthetized mice readily metabolized the tracer whereas anesthetized animals did not (72% ± 4% vs. 20% ± 5% parent remaining in plasma after 35 minutes) (Ramos-Torres et al., 2022). The observed differences in stability between awake and anesthetized subjects strongly suggest that the high stability in anesthetized animals is mediated by isoflurane.

Fig. 1.

Structures of [18F]3F4AP, 4AP, and known metabolites of 4AP.

A likely enzyme responsible for metabolizing [18F]3F4AP is the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP2E1. CYP2E1 is the most abundant P450 enzyme in the human liver (Drozdzik et al., 2018) and is a key player in the breakdown of many small molecule drugs, including 4AP and isoflurane (Kharasch et al., 1999; Chen et al., 2019). The metabolism of 4AP has been investigated in rats, dogs, and humans (Caggiano and Blight, 2013; Caggiano et al., 2013). These studies showed slow metabolism of 4AP, with unmetabolized 4AP amounting to at least 85% of the administered dose in humans 24 hours after either oral or intravenous administration (Evenhuism et al., 1981; Uges et al., 1982). These studies also identified the primary metabolites as 3-hydroxy-4-aminopyridine (3OH4AP, 3a) and the conjugated 3-hydroxy-4AP sulfate (3b) (Fig. 1) (Caggiano et al., 2013). The apparent ability of isoflurane to competitively inhibit the metabolism of [18F]3F4AP in rodents and primates further supports the role of CYP2E1 in 3F4AP metabolism.

Deuteration, a proven strategy in medicinal chemistry for increasing metabolic stability of bioactive compounds, could pose as a potential approach to inhibit the metabolism of 3F4AP. The difference in atomic mass of deuterium makes carbon-deuterium (C-D) bonds harder to break than corresponding carbon-hydrogen (C-H) bonds, thus decreasing the reaction kinetic rate for deuterated compounds compared with their nondeuterated counterparts. (Wiberg, 1955; Kaur and Gupta 2017; Pirali et al., 2019). This outcome can be quantitively expressed as the deuterium kinetic isotope effect [KIE (i.e., kH/kD)]. Most reported examples of reactions catalyzed by cytochrome P450s show KIE values greater than 5 (Nelson and Trager, 2003; Guengerich, 2017). Although most of the examples of KIE pertain to the deuteration of aliphatic carbons, there is at least one reported example in which the deuteration of an aromatic compound (chlorobenzenes) resulted in a reduced reaction rate by P450 (Korzekwa et al., 1989).

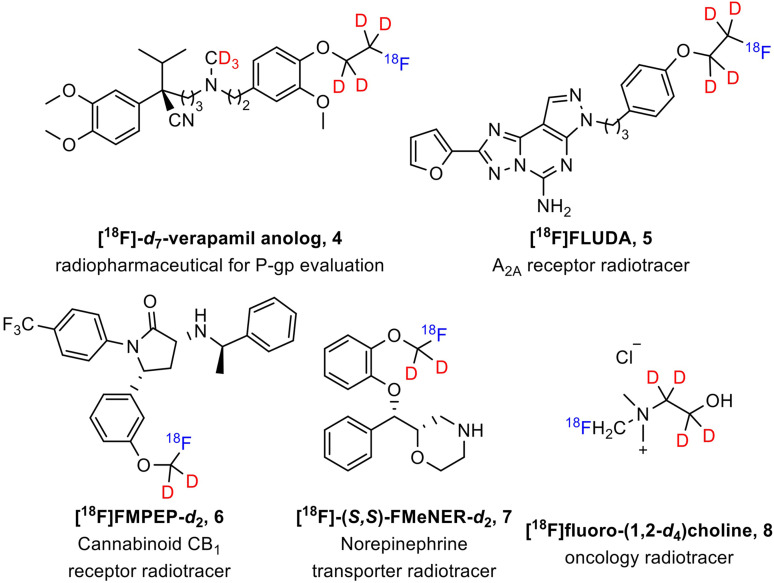

This approach has also been used in PET to reduce the presence of radiometabolites, which can result in off-target signals (Fowler et al., 1995; Schou et al., 2004; Giron et al., 2008; Terry et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2011; Kuchar and Mamat, 2015; Raaphorst et al., 2018; Ghosh et al., 2020; Lai et al., 2021; Xiao et al., 2021). In several cases, deuteration has successfully reduced defluorination and the accumulation of PET signals in bone (Schou et al., 2004; Terry et al., 2010; Raaphorst et al., 2018; Lai et al., 2021) (Fig. 2, tracers 4–7). Additionally, this deuteration strategy has contributed to the elimination of high background signal introduced by the oxidized radiometabolites of nondeuterated PET tracer 8 (Smith et al., 2011) (Fig. 2, tracer 8). Given these findings, we hypothesized that deuterated 3F4AP may be more stable than nondeuterated 3F4AP.

Fig. 2.

Examples of deuterated PET radiotracers.

Herein, we investigate CYP2E1’s role in the metabolism of [18F]3F4AP, the stability of deuterated derivatives, and the identity of its metabolites to better understand the tracer’s metabolic stability and potentially develop strategies to improve upon it.

Materials and Methods

General

All chemicals were ordered from commercial suppliers and used without further purification. 4-Aminopyridine-d6 (98% deuterium incorporation) was purchased from CDN Isotopes. The protium/deuterium exchange reaction was conducted with Biotage Initiator+ microwave synthesizer. The 1H, 19F, and 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were collected on a 300-MHz Bruker spectrometer at 300 MHz, 282 MHz, and 75 MHz, respectively. Copies of the spectra can be found in the supporting information. All 1H-NMR data are reported in δ units, parts per million (ppm), and were calibrated relative to the signals for residual chloroform (7.26 ppm) in deuterochloroform (CDCl3). All 13C-NMR data are reported in ppm relative to CDCl3 (77.16 ppm) and were obtained with 1H decoupling unless otherwise stated. The following abbreviations or combinations thereof were used to explain the multiplicities: s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, br = broad, m = multiplet. High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were recorded on a Thermo Scientific Dionex Ultimate 3000 UHPLC coupled to a Thermo Q Exactive Plus mass spectrometer system using electrospray ionization (ESI) as the ionization approach. Other analytical and preparative high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis was conducted on a Thermo Scientific Dionex Ultimate 3000 UHPLC equipped with the following columns: Waters XBridge BEH HILIC analytical column (3.5 μm, 4.6 × 150 mm); Waters XBridge BEH C18 analytical column (130 Å, 3.5 μm, 4.6 × 150 mm); and SiliaChrom HILIC semipreparative column (100 Å, 5μm, 10 × 150 mm).

Chemical Syntheses

Synthesis of 3-Fluoro-4-Aminopyridine-5-d1 via Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange in the Presence of Deuterium Chloride

A solution of 3-fluoro-4-aminopyridine (2) (56 mg, 0.5 mmol) in deuterium oxide (D2O) (1.0 ml) in the presence of deuterium chloride (DCl) (37% in D2O, 1.0 ml) was irradiated in a sealed Biotage microwave tube at 170°C for 12 hours (hold time) using Biotage microwave synthesizer (maximum pressure 12 bar) by moderation of the initial microwave power (400 W). The mixture was cooled in a stream of compressed air and neutralized with aqueous NaOH solution (5 M, 2.5 ml). The solvent (water) was evaporated under reduced pressure, and the residue was redissolved with CH2Cl2 (3 × 2 ml). The combined organic solution was dried over magnesium sulfate, filtered, and evaporated under reduced pressure to give deuterated isotopologue 3-fluoro-4-aminopyridine-5-d1 (5-d1-3F4AP, 2-d1) in 77% yield. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.15 (s, 0.95 H), 7.99 (s, 0.97 H), 6.62 (dd, J = 7.0, 5.7 Hz, 0.05 H), 4.07 (br, 2 H) ppm (Supplemental Fig. 1). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 149.21 (d, JC-F = 246.2 Hz), 146.14, 146.04 (d, JC-F = 4.8 Hz), 141.44 (d, JC-F = 10.6 Hz), 136.60 (d, JC-F = 20.1 Hz), 110.90 (d, JC-F = 2.0 Hz), 110.63 (td, JC-D = 24.7 Hz, JC-F = 1.9 Hz) ppm (Supplemental Fig. 2). 19F NMR (282 MHz, CDCl3): δ -152.3 ppm (Supplemental Fig. 3). ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M+H]+ calculated for C5H5D1FN2+: 114.0572; found: 114.0573 with 94.5%; C5H6FN2+: 113.0510; found: 113.0510 with 5.5%.

Synthesis of 3-Fluoro-4-Aminopyridine-2,6-d2 and 3-Fluoro-4-Aminopyridine-2-d1 via Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange under Neutral Condition

A solution of 3-fluoro-4-aminopyridine (2) (56 mg, 0.5 mmol) in D2O (2.0 ml) was irradiated in a sealed Biotage microwave tube at 170°C for 12 hours (hold time) using Biotage microwave synthesizer (maximum pressure 12 bar) by moderation of the initial microwave power (400 W). The mixture was cooled in a stream of compressed air, then acidified with 1.0 ml HCl (1 M in aqueous) and neutralized with aqueous NaOH solution (1 M, 1.0 ml). The solvent (water) was evaporated under reduced pressure and the residue was redissolved with CH2Cl2 (3 × 2 ml). The combined organic solution was dried over magnesium sulfate, filtered, and evaporated under reduced pressure to give deuterated isotopologues 3-fluoro-4-aminopyridine-2,6-d2 (2,6-d2-3F4AP, 2-d2) and 3-fluoro-4-aminopyridine-2-d1 (2-d1-3F4AP, 2-d1’) mixture in 84%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.13 (s, 0.02 H), 7.97 (d, J = 4.81 Hz, 0.52 H), 6.61 (m, 0.94 H), 4.59 (br, 2 H) ppm (Supplemental Fig. 4). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 149.04 (d, JC-F = 246.1 Hz), 145.99 (td, JC-D = 3.1, JC-F = 1.3 Hz), 145.66 (tm, JC-D = 27.3), 141.63 (d, JC-F = 10.5 Hz), 136.17 (td, JC-D = 27.4 Hz, JC-F = 20.2 Hz), 110.87 (d, JC-F = 2.0 Hz), 110.74 (br) ppm (Supplemental Fig. 5). 19F NMR (282 MHz, CDCl3): δ -152.41, -152.44 ppm (Supplemental Fig. 6). ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M+H]+ calculated for C5H4D2FN2+: 115.0635, found: 115.0635, 46.8%; C5H5DFN2+: 114.0572, found: 114.0573, 52.0%; C5H6FN2+: 113.0510, found: 113.0511, 1.2%.

Synthesis of 3-Fluoro-4-Aminopyridine-2,5,6-d3 via Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange under Neutral Condition

A solution of 3-fluoro-4-aminopyridine-5-d1 (5-d1-3F4AP, 2-d1) (18 mg, 0.2 mmol) in D2O (1.0 ml) was irradiated in a sealed Biotage microwave tube at 190°C for 8 hours (hold time) using Biotage microwave synthesizer (maximum pressure 12 bar) by moderation of the initial microwave power (400 W). The mixture was cooled in a stream of compressed air, then acidified with 1.0 ml HCl (1 M in aqueous) and neutralized with aqueous NaOH solution (1 M, 1.0 ml). The solvent (water) was evaporated under reduced pressure, and the residue was redissolved with CH2Cl2 (3 × 2 ml). The combined organic solution was dried over magnesium sulfate, filtered, and evaporated under reduced pressure to give deuterated isotopologue 3-fluoro-4-aminopyridine-2,5,6-d3 (2,5,6-d3-3F4AP, 2-d3) in 76% yield. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.12 (s, 0.02 H), 7.97 (s, 0.07 H), 6.61 (d, J = 7.6, 0.03 H), 4.59 (br, 2 H) ppm (Supplemental Fig. 7). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 149.04 (d, JC-F = 246.1 Hz), 145.94, 145.62 (tm, JC-D = 27.0 Hz), 141.60 (d, JC-F = 10.6 Hz), 136.15 (td, JC-D = 27.0 Hz, JC-F = 20.0 Hz), 110.46 (t, JC-D = 24.7 Hz) ppm (Supplemental Fig. 8). 19F NMR (282 MHz, CDCl3): δ -152.5 ppm (Supplemental Fig. 9). ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M+H]+ calculated for C5H3D3FN2+: 116.0698, found: 116.0696, 87.1%; C5H4D2FN2+: 115.0635, found: 115.0634, 13.1%.

Synthesis of 3-Fluoro-4-Aminopyridine 1-Oxide

A suspension of 3-fluoro-4-nitropyridine 1-oxide (10) (50 mg, 0.32 mmol) and palladium on carbon (10%, 5.0 mg) in ethanol (2.0 ml) was bubbled with argon gas for 10 minutes. The reaction mixture was cooled down to 0°C. A hydrogen balloon was loaded and bubbled for another 5 minutes before removing the pressure balance needle. The reaction mixture was kept under stirring and allowed to warm up to room temperature slowly. The reaction was monitored by TLC and analytical HPLC with a C18 analytical column (mobile phase A: 10 mM NH4HCO3 aqueous solution pH 8.0; mobile phase B: acetonitrile; gradient method: 0–5 minute: 3% B, 5–8 minutes: 3% to 90% B, 8–11 minutes: 90% B, 11 to 12 minutes: 90% to 3% B, 12–15 minutes: 3% B; tR of 10 is 8.0 minutes). Pd/C was filtered out after 10 was consumed completely. The filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure, and the residue was purified with prep-HPLC (HILIC semipreparative column, 10 mM NH4HCO3 aqueous solution pH 8.0/acetonitrile = 10/90) to afford 3-fluoro-4-aminopyridine 1-oxide (3F4AP N-oxide, 9a) as an off-white solid in an 84% yield. 1H NMR [300 MHz, methanol-d4 (MeOD)] δ 8.27 − 8.05 (m, 1H), 7.84 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 6.82 (t, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H) ppm (Supplemental Fig. 10). 13C NMR (75 MHz, MeOD) δ 148.54 (d, J = 245.4 Hz), 142.29 (d, J = 12.0 Hz), 137.30, 129.28 (d, J = 33.0 Hz), 111.40 (d, J = 6.5 Hz) ppm (Supplemental Fig. 11). 19F NMR (282 MHz, MeOD) δ -146.00 (dd, J = 9.9, 6.3 Hz) ppm (Supplemental Fig. 12). ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M+H]+ calculated for C5H5FN2O+: 129.0459, found: 129.0457.

Synthesis of 4-Amino-5-Fluoropyrin-3-Ol

4-Amino-5-fluoropyrin-3-ol (5OH3F4AP, 9b) was synthesized by a third-party company (Chemspace). The identification and purity were confirmed by NMR and HRMS. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.14 (s, 1H), 7.85 (s, 1H), 7.69 (s, 1H), 5.88 (s, 2H) ppm (Supplemental Fig. 13). 19F NMR (282 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ -150.68 ppm (Supplemental Fig. 14). ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M+H]+ calculated for C5H5FN2O+: 129.0459, found: 129.0464.

Radiochemical Synthesis of [18F]3F4AP for Vivid CYP2E1 Catalyzed Reaction

[18F]3F4AP was prepared using a GE Fx2N synthesizer according to the reported procedure (Basuli et al., 2018). [18F]3F4AP was purified via semipreparative HPLC using a Waters C18 preparative column (XBridge BEH C18 OBD Prep Column 130 Å, 5 μm, 10 mm × 250 mm). The obtained [18F]3F4AP fraction (radiopurity >99%, molar activity = 3.8 ± 0.5 Ci/μmol, n = 2 in 95% 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 8.0, 5% EtOH solution) was concentrated at 10% of volume to reduce EtOH amount as much as possible. The resulted solution was used directly for further reaction.

In Vitro Experimental Procedures

Evaluation of CYP2E1 Inhibition by Study Compounds

The examination of the relative metabolic rates in the presence of the study compounds was carried out with Life Technologies Vivid CYP2E1 screening kit. This kit relies on the detection of fluorescence emitted by 3-cyano-7-hydroxy-coumarin, the product from the O-dealkylation reaction of a specific CYP2E1 substrate [2H-1-benzopyran-3-carbonitrile,7-(ethoxy-methoxy)-2-oxo-(9Cl)] in the absence and presence of substrate competitors (Marks et al., 2002). Based on this kit’s principle, the blank experiments (without any competitors) result in the highest fluorescence values whereas increasing amounts of competitors decrease the fluorogenic emission.

In a falcon black/clear 384-well plate, 40 μl of 2.5X (final concentration 15μM) test compounds (4AP, 4AP-d6, 3F4AP, 3F4AP-dx, tranylcypromine) solution in 1X Vivid CYP2E1 reaction buffer was added to desired wells in three replicates. Afterward, 50 μl master premix (2X (40 nM) CYP2E1 BACULOSOMES and 2X (0.6 Units/ml) Vivid regeneration system in 1X reaction buffer) was added to each well. The plate was incubated for 10 minutes at room temperature to allow the compounds to interact with the CYP2E1 in the absence of enzyme turnover. Next, the reaction was initiated by adding 10μl per well of 10X (100 μM) Vivid substrate and 10X (300 μM) Vivid NADP+ mixture. Immediately (under 2 minutes), the plate was transferred into the fluorescent plate reader and fluorescence was monitored over 60 minutes (reads in 1-minute intervals) at 415 nm as excitation wavelength and 460 nm as emission wavelength. The obtained reads were plotted using GraphPad Prism 9.

Determination of the IC50 and Inhibition Constant of 4AP and 3F4AP

A similar Vivid CYP2E1 assay was conducted as described above. Instead of testing a single concentration of the test compounds (final concentration 15μM), a series of concentrations of 4AP (120mM, 40 mM, 12 mM, 4.0 mM, 1.2 mM, 400 μM, 120 μM, 40 μM, 12 μM, 4.0 μM), 3F4AP (400 μM, 120 μM, 40 μM, 12 μM, 4.0 μM, 1.2 μM, 0.4 μM) and tranylcypromine (40 μM, 12 μM, 4.0 μM, 1.2 μM, 0.4 μM, 0.12 μM, 0.04 μM) was tested with three replicates for each concentration. The plate fluorescence was monitored over 60 minutes (reads in 1-minute intervals) at 415 nm as excitation wavelength and 460 nm as emission wavelength. The reads at 60 minutes (recalculated by the linear trend line equation) of each concentration were used and fitted with GraphPad Prism9 dose-response-inhibition (concentration is log) curve fitting to calculate the IC50 values. The corresponding inhibition constant (Ki) values were calculated by Ki = IC50/(1+[S]/Km (Km = 22 (Marks et al., 2002), the Vivid EOMCC substrate concentration [S] is 10 μM).

Identification of In Vitro Metabolites Produced by Human Recombinant CYP2E1 Using High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry

The reactions were conducted using a modified Vivid CYP2E1 kit protocol. Briefly, the reactions were performed in an Eppendorf vial using a higher concentration of the deuterated substrates (3F4AP-dx, 125 μM) and excluding the fluorescent reporter. After addition of all the components, the vial was placed in a 37°C shaker and allowed to react for 20 hours. Reaction mixture was then diluted to 5 folds with ultrapure water and submitted to Harvard Center for Mass Spectrometry for high-resolution mass spectrometry.

Confirmation of In Vitro Metabolites Produced by Human Recombinant CYP2E1 by Coelution on HPLC

The reactions were conducted with Vivid CYP2E1 enzyme, NADP+, and NADPH regeneration system. In a 1.5-ml Eppendorf vial, 10 μl of [18F]3F4AP solution above was diluted with 30 μl of 1X Vivid CYP2E1 reaction buffer. After 50 μl master premix (2X, 200 nM CYP2E1 BACULOSOMES and 2X Vivid regeneration system 3 Units/ml in 1X reaction buffer) was added, the reaction mixture was incubated for 10 minutes at 37°C to allow [18F]3F4AP to interact with the CYP2E1 in the absence of enzyme turnover. Reaction was initiated by adding 10μl of 10X Vivid NADP+ mixture (1.5 mM). Immediately, reaction vial was transferred into a 37°C shaker and allowed to react for 2 hours. The reaction mixture was then filtrated with Amicon Ultra-0.5 centrifugal filter (pore size = 10 kDa NMWCO). The filtrate was analyzed with HPLC using a HILIC analytical column (mobile phase: 10 mM NH4HCO3 aqueous solution pH 8.0/acetonitrile 10/90). The identification of the formation of [18F]9a (tR ∼ 6.0 minutes in radio chromatogram) was confirmed by coinjection with 9a (tR ∼ 5.9 minutes in UV chromatogram), whereas [18F]9b (tR ∼ 3.7 minutes in radio chromatogram) was confirmed with 9b (tR ∼ 3.6 minutes in UV chromatogram).

Partition Coefficient Determination

The octanol-water partition coefficient (logD) at pH 7.4 was determined using a modified version of the shake flask method (Rodriguez-Rangel et al., 2020). Briefly, PBS (900 μl), 1-octanol (900 μl), and a 10-mg/ml aqueous solution of each compound (2 μl) were added to a 2-ml HPLC vial. The compounds were partitioned between the layers via vortexing and centrifuged at 1000 g for 1 minute to allow for phase separation. A portion (10 μl) was taken from each layer (autoinjector was set up to draw volume at two different heights) and analyzed by HPLC. The relative concentration in each phase was determined by integrating the area under each peak and comparing the ratio of the areas from the octanol and aqueous layers. A calibration curve was performed to ensure that the concentrations detected were within the linear range of the detector (Supplemental Fig. 16). This procedure was repeated four times for each compound.

In Vitro Assessment of Permeability to an Artificial Brain Membrane

The brain permeability of 3F4AP and its metabolites was estimated using a parallel artificial membrane permeability assay for the blood brain barrier (PAMPA-BBB) kit from Bioassay Systems. Three hundred microliters of phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) was added to wells in the acceptor plate. With the donor plate still in its tray, 5 μl of BBB lipid solution in dodecane was added directly to the well membranes of the donor plate. Then 200 μl of 500 μM solution of each test compound (3F4AP, 5OH-3F4AP, 3F4AP N-oxide) and permeability controls (promazine hydrochloride as high control and diclofenac as low control, supplied along with the kit) were added in duplicate to wells of the donor plate. Then the donor plate was placed into the acceptor plate wells and allowed to incubate at room temperature for 18 hours. After 18 hours, the concentration of the donor and acceptor solutions in each well was analyzed using a spectrophotometer (5OH3F4AP OD300nm, 3F4AP N-oxide OD295nm, diclofenac OD300nm, promazine hydrochloride OD310nm) and/or HPLC (3F4AP tR 4.5 minutes at 254 nm, 5OH3F4AP tR 2.3 minutes at 310 nm, both using C18 analytic column with mobile phase as 95:5 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH = 8): EtOH). A calibration curve for each test compound and permeability control was performed to ensure that the concentrations detected were within the linear range of the detector (Supplemental Figs. 16 and 17). The measured absorbance (OD) and area under the curve (AUC) with those of 200-μM equilibrium standards for each test compound and permeability control were used to determine the permeability rate (Pe) with Pe = C × −ln(1-ODA/ODE) or Pe = C × −ln(1-AUCA/AUCE) cm/s, where ODA and AUCA are values of acceptor solution, ODE and AUCE are values of the equilibrium standard, and C is correlate to incubation duration (for 18 hours; C = 7.72 × 10−6).

Results

Cytochrome P450 CYP2E1 Metabolizes 3F4AP

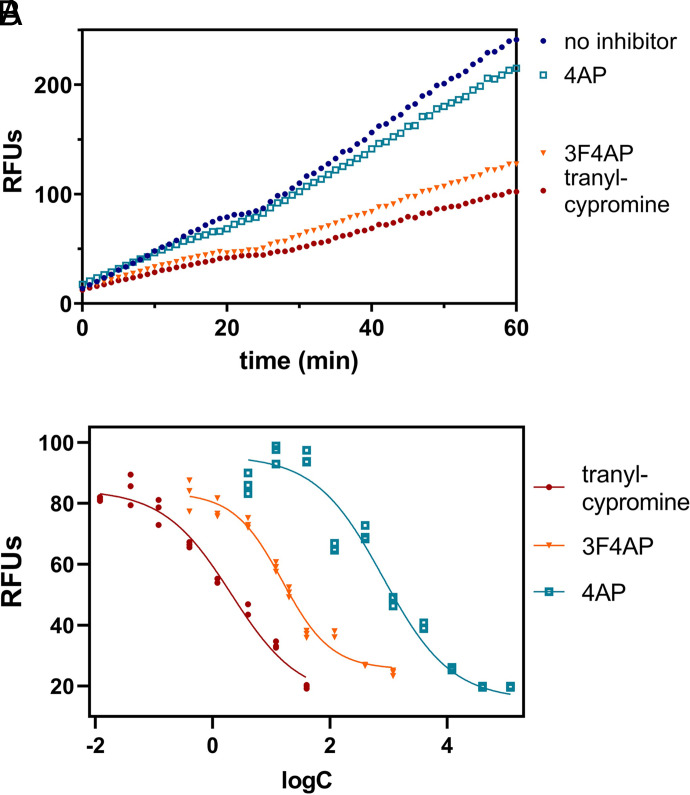

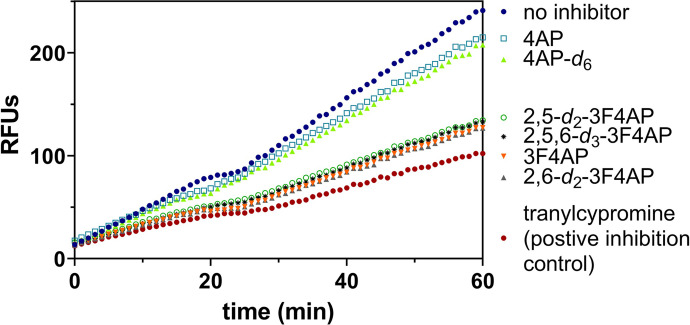

To examine the role of CYP2E1 in 3F4AP’s metabolism, we compared the reaction rate of 4AP, 3F4AP, and tranylcypromine (positive control) in a competitive inhibition assay for CYP2E1.

As can be seen in Fig. 3A, tranylcypromine was very effective at slowing down the formation of the fluorescent product, indicating that it is an excellent inhibitor of the CYP2E1 (maroon vs. blue lines). In comparison, 4AP showed a moderate reduction in the reaction rate (cyan vs. blue lines), indicating that it is a poorer substrate. 3F4AP, on the other hand, showed a very robust reduction in the reaction rate (orange line), indicating that it is also a very good substrate of the enzyme.

Fig. 3.

Evaluation of CYP2E1 enzyme-catalyzed oxidation of 3F4AP. (A) Relative fluorescence-time curves based on the 60-minute kinetic measurement of 4AP, 3F4AP, and tranylcypromine as positive control for inhibition. (B) IC50 fit curves of 4AP, 3F4AP, and tranylcypromine.

To quantify these differences, we measured the reaction rate in the presence of different concentrations of 4AP, 3F4AP, and tranylcypromine. Plotting the relative fluorescence units at 60 minutes (RFUs) against the logarithm of the concentrations resulted in the sigmoidal curves, which could be fitted to calculate the IC50 and Ki (Fig. 3B). As shown in Table 1, the calculated IC50 and Ki of tranylcypromine were largely consistent with previously published values (Marks et al., 2002). In comparison, 4AP showed a ∼ 400-fold higher IC50 and Ki, confirming that it is a weaker substrate. 3F4AP, on the other hand, showed an IC50 and Ki around 8-fold higher than tranylcypromine, which confirms that 3F4AP is an excellent substrate of CYP2E1. For reference, acetaminophen, a known substrate of CYP2E1, has much higher IC50 and Ki values than 4AP, confirming that both 4AP and 3F4AP are suitable CYP2E1 substrates, although 3F4AP is a much better one. This explains why in humans 85% of unmetabolized 4AP is recovered 24 hours after a single oral or intravenous administration (Evenhuism et al., 1981; Uges et al., 1982), whereas less than 50% of unmetabolized [18F]3F4AP remains in circulation 1 hour after intravenous administration.

TABLE 1.

IC50 and Ki values for CYP2E1 substrates

| Compounds | Measured Values | Published Values | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 (μM) | Ki (μM) | IC50 (μM) | Ki (μM) | |

| Tranylcypromine | 2.06 | 1.6 | 0.96 | 0.6 |

| 4-Aminopyridine | 810 | 550 | NA | NA |

| 3-Fluoro-4-Aminopyridine | 15.4 | 10.6 | NA | NA |

| Acetaminophen | NA | NA | 1700 | 1100 |

NA, not available.

Synthesis of Deuterated 3F4AP Isotopologues and Their Metabolic Stability

Given that 3F4AP is an excellent substrate of CYP2E1, we sought to test the hypothesis that deuterated forms of 3F4AP would be more stable against CYP2E1 oxidation. Thus, we prepared the deuterated 3F4AP isotopologues and tested their relative metabolic stability using the Vivid CYP2E1 assay.

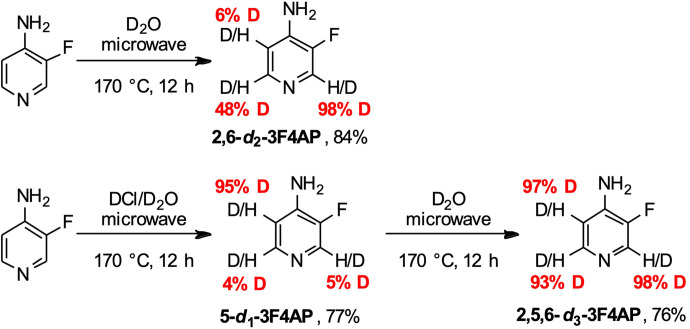

Attempts to fluorinate 4AP-d6 with reactive electrophilic fluorination reagent Selectfluor in water or a combined water/chloroform solvent system at 80°C did not generate deuterated 3F4AP in useful yields (<5% conversion), prompting us to explore the direct protium/deuterium exchange of 3F4AP. We decided to test hydrogen-deuterium (H/D) exchange under microwave irradiation, as it requires lower temperature and shorter reaction time compared with other methods (Werstiuk and Ju, 1989; Esaki et al., 2006; Bagley et al., 2016). As shown in Fig. 4, reaction of 3F4AP in D2O under microwave irradiation at 170°C gave 2,6-d2-3F4AP, with D incorporation of 98% at C-2 and 48% at C-6 after 12 hours. On the other hand, the reaction in the presence of DCl at 170°C produced 5-d1-3F4AP with D incorporation of 94% at C-5. The regioselectivity of this acid-mediated deuteration, preferably at β-position, can be explained by an aromatic electrophilic substitution mechanism. To synthesize a fully deuterated 3F4AP, a sequential reaction with both conditions was conducted, resulting in 2,5,6-d3-3F4AP with D incorporation of 97%, 98%, and 93% at C-5, C-2, and C-6, respectively. Moreover, these straightforward protium/deuterium exchange reactions gave a 76%–84% yield range.

Fig. 4.

Deuteration of 3F4AP under microwave irradiation.

Then, we evaluated the kinetic isotope effect of the prepared deuterated 3F4AP isotopologues as well as the commercially available 4AP-d6 using the Vivid CYP2E1 assay. As shown in Fig. 5, the fluorescence response curves of deuterated isotopologues are almost equivalent to their corresponding nondeuterated compounds, indicating no deuterium kinetic isotope effect (KIEs <1.1 for all of the deuterated isotopologues).

Fig. 5.

Evaluation of kinetic isotope effect in the Vivid CYP2E1 enzyme-catalyzed oxidation. Relative fluorescence-time curves based on the 60-minute kinetic measurement of 4AP, 4AP-d6, 3F4AP, and three deuterated 3F4AP-dx; tranylcypromine is known as a good CYP2E1 inhibitor.

Identification of the Oxidation Metabolites of 3F4AP

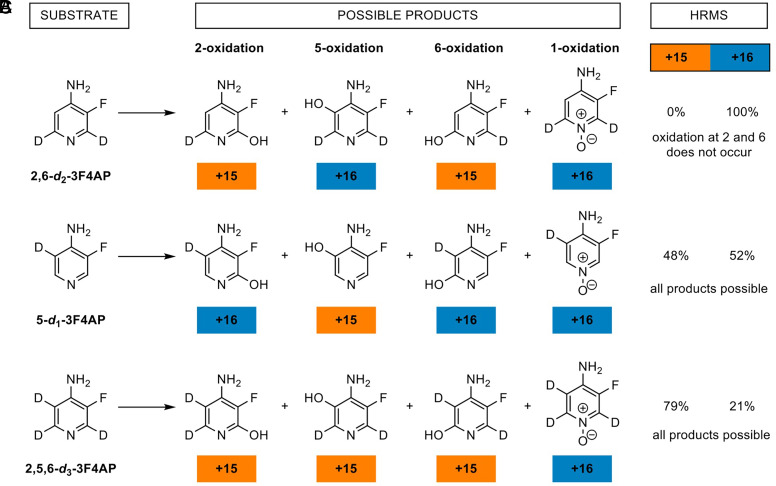

Having prepared the deuterated isotopologues, we can exploit the difference in mass associated with the loss of a deuterium or hydrogen upon reaction with CYP2E1 to identify the substrate reaction site.

A series of reactions using recombinant CYP2E1 enzyme and the different deuterated 3F4AP substrates (i.e., 2,5,6-d3-3F4AP, 5-d1-3F4AP, and 2,6-d2-3F4AP) was performed and analyzed by high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS). Figure 6 shows the different reactants and all of the possible products with the mass change listed underneath. Oxidation at a hydrogen position results in a mass gain of 16 Da (−1 Da from the loss of one H plus 17 Da from addition of one OH) whereas oxidation at a deuterium position results in a mass gain of 15 Da (−2 Da from the loss of one D plus 17 Da from addition of one OH). Oxidation at the pyridine nitrogen to form the N-oxide product also results in a gain of 16 Da from addition of one oxygen. Since the reaction is performed in aqueous buffer, we assumed that the addition of -OD (plus 17 Da) does not proceed. In reaction A, only the +16 Da was detected, indicating that oxidation at C-2 and C-6 position does not occur. In reactions B and C, we detected both the +15 Da and +16 Da products, suggesting that oxidation occurs both at the C-5 and N-1 position.

Fig. 6.

Identification of oxidation metabolites of 3F4AP via HRMS. Vivid CYP2E1 enzyme-catalyzed oxidation reactions with various deuterated 3F4AP substrates were performed to identify the resulting metabolites via HRMS detection of oxidation at a hydrogen (+16), a deuterium (+15), or the pyridine nitrogen position (+16). See reaction conditions in the methods.

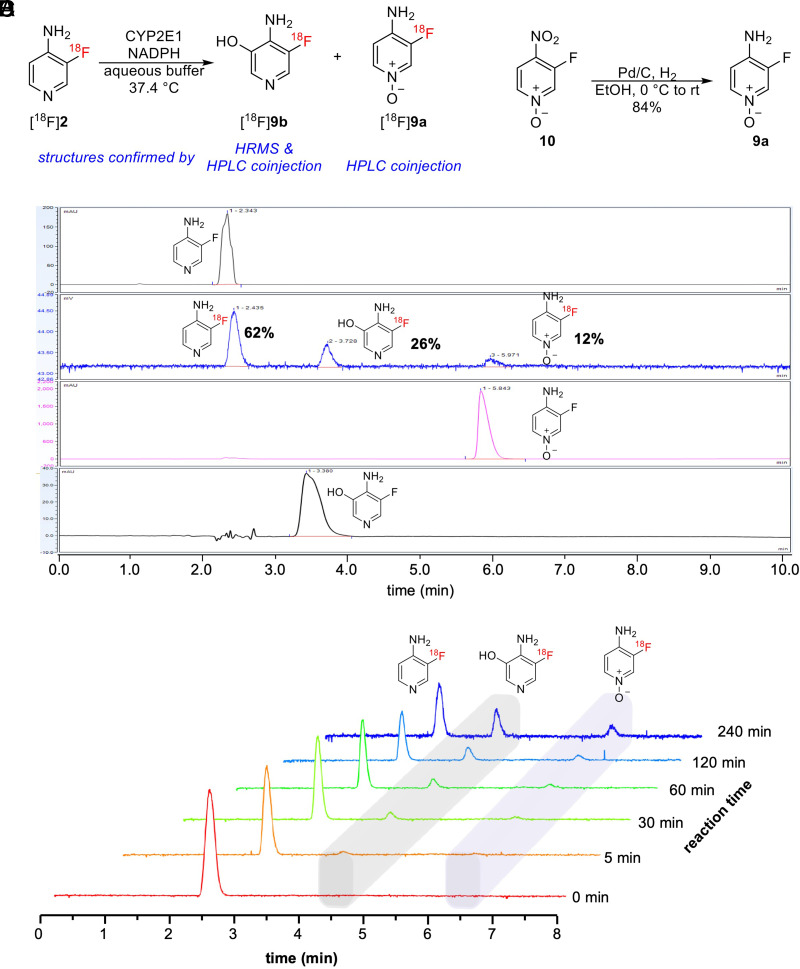

To identify the metabolites produced, we performed the CYP2E1 reaction using radioactive [18F]3F4AP and looked for the presence of [18F]3F4AP N-oxide and 5-hydroxy-[18F]3F4AP by coelution with reference standards on HPLC (Fig. 7A). The 3F4AP N-oxide (9a) reference standard was prepared via Pd/C catalyzed partial reduction of 3-fluoro-4-nitropyridine N-oxide 10 in ethanol under 1 atm of H2 (Fig. 7B), 5-hydroxy-3F4AP was synthesized by a third party, and [18F]3F4AP was prepared according to the previously reported procedure (Basuli et al., 2018). With these compounds in hand, we performed the CYP2E1 enzymatic reaction on [18F]3F4AP and confirmed the formation of 5-hydroxy-[18F]3F4AP (9b) and [18F]3F4AP N-oxide (9a) (Fig. 7D; tR = 3.7 and 6.0 minutes, respectively) by coinjection with the prepared standard. The yields of individual metabolites were determined by the area under the curve (AUC) of the corresponding peak. Tracking the reaction at 5, 30, 60, 120, and 240 minutes showed that 5-hydroxy-3F4AP ([18F]9b) is about twice as abundant as [18F]3F4AP N-oxide [18F]9a (Fig. 7E), confirming that the oxidation at the 5 position is more favorable.

Fig. 7.

Identification of [18F]3F4AP metabolites in vitro. (A) Reaction scheme of Vivid CYP2E1 enzyme-catalyzed oxidation with [18F]3F4AP as substrate. (B) Reaction scheme of 3F4AP N-oxide preparation. (C) Analytical HPLC chromatograms of Vivid CYP2E1 enzyme-catalyzed oxidation reaction crude (radioactive traces, at 240 minutes) plus 3F4AP, 3F4AP N-oxide, and 5-hydroxy-3F4AP reference standard (UV 254 nm). (E) Time course of the CYP2E1 enzyme-catalyzed oxidation reaction showing the formation of metabolites at 0, 5, 30, 60, 120, and 240 minutes.

In Vitro Evaluation of Brain Permeability of 3F4AP and Its Metabolites

After confirming the structure of the metabolites, we conducted further tests to determine their lipophilicity and brain permeability (Table 2). Our findings show that 5-hydroxy-3F4AP and 3F4AP N-oxide have octanol/water partition coefficient values at pH 7.4 of −0.465 and −1.204, respectively, whereas the value for 3F4AP is 0.414 (Rodriguez-Rangel et al., 2020). This indicates that these metabolites preferentially partition in the aqueous layer and may have limited penetration of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) by passive diffusion, which was confirmed by their measured permeability rates using a PAMPA assay (Table 2). Specifically, 3F4AP exhibited a similar permeability rate to diclofenac (see Supplemental Fig. 15), whereas 5-hydroxy-3F4AP had a permeability rate 10 times slower and 3F4AP N-oxide had a permeability rate more than 100 times slower.

TABLE 2.

logD values and permeability rate (at pH = 7.4) of 3F4AP and its metabolites

| Compounds | logD | Permeability Rate (× 10−6 cm/s) |

|---|---|---|

| 3F4AP | 0.414 ± 0.002 | 1.893 ± 0.020 |

| 5-Hydroxy-3F4AP | −0.465 ± 0.007 | 0.204 ± 0.009 |

| 3F4AP N-Oxide | −1.204 ± 0.009 | 0.0153 ± 0.013 |

Discussion

Understanding the metabolic stability of PET tracers is paramount to its application in humans. Tracers that are metabolized too quickly (in seconds or minutes) may not reach a sufficient concentration in the target, whereas tracers in which the metabolites are present in the target organ may contribute background signal. Furthermore, to accurately model the kinetics of a tracer, it is necessary to know the fraction of radioactivity corresponding to the parent tracer in circulation. Since metabolism may vary across human subjects, understanding the nature of the metabolites and the enzymes responsible for their occurrence can be useful to design strategies to minimize metabolism, develop methods to measure metabolism, and understand whether metabolites are present in a target organ such as the brain.

Motivated by recent findings that [18F]3F4AP is less stable in awake humans than in anesthetized monkeys and rodents, we investigated the in vitro metabolism of 3F4AP and demonstrated that 3F4AP is an excellent substrate of CYP2E1 (Fig. 3), pointing toward the likely responsibility of this enzyme for the metabolism of 3F4AP in vivo. This conclusion is also supported by prior reports indicating that 4AP is primarily metabolized by CYP2E1 and by our experiments with isoflurane-anesthetized and awake mice indicating that isoflurane (a substrate of CYP2E1) can inhibit the metabolism of [18F]3F4AP in vivo (Ramos-Torres et al., 2022). Nevertheless, since the tracer metabolism in vivo is more complex and may involve other enzymes and pathways, further efforts to investigate the 3F4AP metabolism in vivo appear warranted.

In addition, we generated three deuterated 3F4AP isotopologues of 3F4AP by direct protium/deuterium exchange under microwave irradiation with high deuteration incorporation and good yields (Fig. 4). These deuterated isotopologues allowed us to probe their stability and identify the metabolites of 3F4AP. In terms of stability, the deuterated isotopologues were not more stable toward oxidation than 3F4AP (Fig. 5). In hindsight, this is reasonable given that the deuterium isotope effect is known to occur in aliphatic protons where the C-H bond breaking is the rate-limiting step, whereas in aromatic protons this is not usually the rate limiting step. This finding further establishes the understanding of when deuteration can be a useful strategy to decrease metabolism.

The deuterated 3F4AP isotopologues were instrumental in identifying the metabolites of 3F4AP as the 5- and 1-oxidation products. Using HRMS, we were able to confirm the formation of 5-hydroxy-3F4AP and 3F4AP N-oxide and exclude the formation of 2- and 6-hydroxy-3F4AP (Fig. 6). Additional radio-HPLC experiments using [18F]3F4AP confirmed that 5-hydroxy-3F4AP and 3F4AP N-oxide are formed, with the former being more abundant (Fig. 7). Notably, the corresponding N-oxide metabolite was not detected among 4AP metabolites (Caggiano and Blight, 2013; Caggiano et al., 2013). In addition, our finding that 3F4AP is a much better substrate of CYP2E1 than 4AP likely explains why the metabolism of 3F4AP in vivo appears much faster than that of 4AP [30% 3F4AP parent remaining 60 minutes after intravenous injection (Brugarolas et al., 2023) vs. 70% parent 4AP 24 hours after oral administration (Blight and Henney, 2009; Caggiano and Blight., 2013)]. Another novelty from this work is that our approach to characterize the metabolites of 3F4AP by using deuterated isotopologues takes advantage of the mass differences during the reaction at different sites, reducing the need of synthesizing multiple reference standards.

The identification of the metabolites is valuable information, as it allows assessment of whether the radiometabolites of [18F]3F4AP may get into the brain. Based on the measured logD of the identified 3F4AP metabolites (5-hydroxy-3F4AP: −0.465; 3F4AP N-oxide: −1.204) and the limited diffusion through an artificial BBB membrane (Table 2), these are not likely brain penetrant, which may facilitate the quantification and interpretation of the PET imaging results with this tracer. Furthermore, the identification of the metabolic enzyme and metabolic products may be useful in designing second-generation PET tracers with higher metabolic stability.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank David F. Lee, Jr., John A. Correia, and Hamid Sabet for providing the fluorine-18 for the radiotracer synthesis. The authors thank Jennifer X. Wang for the high-resolution mass spectra measurement and data analysis. The authors also thank Marc D. Normandin and Nicolas J. Guehl for valuable discussion.

Abbreviations

- 4AP

4-aminopyridine

- AUC

area under curve

- BBB

blood-brain barrier

- CYP2E1

cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily E member 1

- DCl

deuterium chloride

- D2O

deuterium oxide

- ESI

electrospray ionization

- 3F4AP

3-fluoro-4-aminopyridine

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- HRMS

high-resolution mass spectrometry

- Ki

inhibition constant

- KIE

kinetic isotope effect

- MeOD

methanol-d4

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- OD

measured absorbance

- PET

positron emission tomography

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Sun, Ramos-Torres, Brugarolas.

Conducted experiments: Sun, Ramos-Torres.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Sun.

Performed data analysis: Sun.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Sun, Ramos-Torres, Brugarolas.

Footnotes

This study was partially supported by National Institutes of Health National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke [Grant R01-NS114066] (to P.B.).

P.B. has a financial interest in Fuzionaire Diagnostics and the University of Chicago. P.B. is the inventor of [18F]3F4AP, a PET imaging agent owned by the University of Chicago and licensed to Fuzionaire Diagnostics. Dr. Brugarolas’ interests were reviewed and are managed by Massachusetts General Hospital and Mass General Brigham in accordance with their conflict of interest policies. The other authors declare no conflict of interests.

A preprint of this article was deposited in bioRxiv [https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.27.509607].

This article has supplemental material available at jpet.aspetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at jpet.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Bagley M, Alnomsy A, Sharhan H (2016) Rapid protium-deuterium exchange of 4-aminopyridines in neutral D2O under microwave irradiation. Synlett 27:2467–2472 DOI: 10.1055/s-0035-1562479. [Google Scholar]

- Basuli F, Zhang X, Brugarolas P, Reich DS, Swenson RE (2018) An efficient new method for the synthesis of 3-[18 F]fluoro-4-aminopyridine via Yamada-Curtius rearrangement. J Labelled Comp Radiopharm 61:112–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blight AR, Henney HR 3rd (2009) Pharmacokinetics of 14C-radioactivity after oral intake of a single dose of 14C-labeled fampridine (4-aminopyridine) in healthy volunteers. Clin Ther 31:328–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugarolas PSánchez-Rodríguez JETsai HMBasuli FCheng SHZhang XCaprariello AVLacroix JJFreifelder RMurali D, et al. (2018) Development of a PET radioligand for potassium channels to image CNS demyelination. Sci Rep 8:607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugarolas PWilks MQNoel JKaiser J-AVesper DRRamos-Torres KMGuehl NJMacdonald-Soccorso MTSun YRice PA, et al. (2023) Human biodistribution and radiation dosimetry of the demyelination tracer [18F]3F4AP. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 50:344–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caggiano A, Blight A (2013) Identification of metabolites of dalfampridine (4-aminopyridine) in human subjects and reaction phenotyping of relevant cytochrome P450 pathways. J Drug Assess 2:117–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caggiano A, Blight A, Parry TJ (2013) Identification of metabolites of dalfampridine (4-aminopyridine) in dog and rat. J Drug Assess 2:72–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Jiang S, Wang J, Renukuntla J, Sirimulla S, Chen J (2019) A comprehensive review of cytochrome P450 2E1 for xenobiotic metabolism. Drug Metab Rev 51:178–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drozdzik M, Busch D, Lapczuk J, Müller J, Ostrowski M, Kurzawski M, Oswald S (2018) Protein abundance of clinically relevant drug-metabolizing enzymes in the human liver and intestine: a comparative analysis in paired tissue specimens. Clin Pharmacol Ther 104:515–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esaki H, Ito N, Sakai S, Maegawa T, Monguchi Y, Sajiki H (2006) General method of obtaining deuterium-labeled heterocyclic compounds using neutral D2O with heterogeneous Pd/C. Tetrahedron 62:10954–10961 DOI: 10.1016/j.tet.2006.08.088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evenhuism J, Agostonm S, Salt PJ, De Lange AR, Wouthuyzen W, Erdmannm W (1981) Pharmacokinetics of 4-aminopyridine in human volunteer: a preliminary study using a new GLC method for its estimation. Br J Anaesth 53:567–570 DOI: 10.1093/bja/53.6.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler JSWang GJLogan JXie SVolkow NDMacGregor RRSchlyer DJPappas NAlexoff DLPatlak C, et al. (1995) Selective reduction of radiotracer trapping by deuterium substitution: comparison of carbon-11-L-deprenyl and carbon-11-deprenyl-D2 for MAO B mapping. J Nucl Med 36:1255–1262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh KK, Padmanabhan P, Yang CT, Mishra S, Halldin C, Gulyás B (2020) Dealing with PET radiometabolites. EJNMMI Res 10:109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giron MC, Portolan S, Bin A, Mazzi U, Cutler CS (2008) Cytochrome P450 and radiopharmaceutical metabolism. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 52:254–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guehl NJRamos-Torres KMLinnman CMoon SHDhaynaut MWilks MQHan PKMa CNeelamegam RZhou YP, et al. (2021) Evaluation of the potassium channel tracer [18F]3F4AP in rhesus macaques. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 41:1721–1733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guengerich FP (2017) Kinetic deuterium isotope effects in cytochrome P450 reactions. Methods Enzymol 596:217–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur S, Gupta M (2017) Deuteration as a tool for optimization of metabolic stability and toxicity of drugs. Glob J Pharmaceu Sci 1:555566. DOI: 10.19080/GJPPS.2017.01.555566. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kharasch ED, Hankins DC, Cox K (1999) Clinical isoflurane metabolism by cytochrome P450 2E1. Anesthesiology 90:766–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korzekwa KR, Swinney DC, Trager WF (1989) Isotopically labeled chlorobenzenes as probes for the mechanism of cytochrome P-450 catalyzed aromatic hydroxylation. Biochemistry 28:9019–9027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchar M, Mamat C (2015) Methods to increase the metabolic stability of (18)F-radiotracers. Molecules 20:16186–16220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai THToussaint MTeodoro RDukić-Stefanović SGündel DLudwig F-AWenzel BSchröder SSattler BMoldovan R-P, et al. (2021) Improved in vivo PET imaging of the adenosine A2A receptor in the brain using [18F]FLUDA, a deuterated radiotracer with high metabolic stability. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 48:2727–2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks BD, Smith RW, Braun HA, Goossens TA, Christenson M, Ozers MS, Lebakken CS, Trubetskoy OV (2002) A high throughput screening assay to screen for CYP2E1 metabolism and inhibition using a fluorogenic vivid p450 substrate. Assay Drug Dev Technol 1:73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson SD, Trager WF (2003) The use of deuterium isotope effects to probe the active site properties, mechanism of cytochrome P450-catalyzed reactions, and mechanisms of metabolically dependent toxicity. Drug Metab Dispos 31:1481–1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirali T, Serafini M, Cargnin S, Genazzani AA (2019) Applications of deuterium in medicinal chemistry. J Med Chem 62:5276–5297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raaphorst RM, Luurtsema G, Schokker CJ, Attia KA, Schuit RC, Elsinga PH, Lammertsma AA, Windhorst AD (2018) Improving metabolic stability of fluorine-18 labeled verapamil analogs. Nucl Med Biol 64-65:47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Torres K, Sun Y, Takahashi K, Zhou Y-P, Brugarolas P (2022) Evaluation of anesthesia effects on the brain uptake and metabolism of demyelination tracer [18F]3F4AP. J Nucl Med 63 (Suppl 2):2956. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Rangel S, Bravin AD, Ramos-Torres KM, Brugarolas P, Sánchez-Rodríguez JE (2020) Structure-activity relationship studies of four novel 4-aminopyridine K+ channel blockers. Sci Rep 10:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schou MHalldin CSóvágó JPike VWHall HGulyás BMozley PDDobson DShchukin EInnis RB, et al. (2004) PET evaluation of novel radiofluorinated reboxetine analogs as norepinephrine transporter probes in the monkey brain. Synapse 53:57–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GZhao YLeyton JShan BNguyen Q-DPerumal MTurton DÅrstad ELuthra SKRobins EG, et al. (2011) Radiosynthesis and pre-clinical evaluation of [18F]fluoro-[1,2-2H4]choline. Nucl Med Biol 38:39–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry GEHirvonen JLiow J-SZoghbi SSGladding RTauscher JTSchaus JMPhebus LFelder CCMorse CL, et al. (2010) Imaging and quantitation of cannabinoid CB1 receptors in human and monkey brains using (18)F-labeled inverse agonist radioligands. J Nucl Med 51:112–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uges DR, Sohn YJ, Greijdanus B, Scaf AH, Agoston S (1982) 4-Aminopyridine kinetics. Clin Pharmacol Ther 31:587–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werstiuk NH, Ju C (1989) Protium–deuterium exchange of substituted pyridines in neutral D2O at elevated temperatures. Can J Chem 67:5–10 DOI: 10.1139/v89-002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiberg KB (1955) The deuterium isotope effect. Chem Rev 55:713–743. DOI: 10.1021/cr50004a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H, Choi SR, Zhao R, Ploessl K, Alexoff D, Zhu L, Zha Z, Kung HF (2021) A new highly deuterated [18F]AV-45, [18F]D15FSP, for imaging β-amyloid plaques in the brain. ACS Med Chem Lett 12:1086–1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]