Abstract

Caregivers of older adults with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) are requiring more support now that novel, nonintensive therapies, such as hypomethylating agents and venetoclax, are shifting the burden of care to the outpatient setting. Early findings from a larger study describe supportive care needs from the perspective of bereaved caregivers that align with existing research, informing the development of best practices for oncology nurses who support caregivers of older adults with AML.

Keywords: acute myeloid leukemia (AML), palliative care, bereavement, caregivers, end of life

Introduction

A diagnosis of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is often unexpected, life-threatening, and associated with high levels of distress, confusion, and upheaval in the lives of patients and caregivers (Leak-Bryant et al, 2015; Albrecht and Bryant, 2019; Rodin et al, 2018). Older adults with AML are living longer because of more effective novel regimens using hypomethylating agents and venetoclax, but these survival benefits may extend and escalate patient and caregiver needs for palliative care at home and in other outpatient settings (Jonas and Pollyea, 2019; Kent et al., 2016). Caregiving spouses of older adults may be additionally challenged by their own health concerns or other age-related limitations (Kehoe et al., 2019). During survivorship, caregivers struggling to balance their own needs with their many responsibilities may benefit from access to supportive care through the survivor’s health care team. However, these supports may no longer be available to caregivers in bereavement because of the natural end of contact with the cancer care team after the patient’s death (Holtslander et al., 2017). These factors can correlate to a complicated adjustment for caregivers after death (Holtslander et al., 2017) and can lead to “complicated grief,” defined as a prolonged period of profound difficulty accepting and adjusting to loss (Tofthagen et al., 2017).

The caregiving experience in AML is not well-documented, particularly from the perspective of bereavement (Grover et al., 2019). This article will describe findings from an oncology nurse-led qualitative interview study exploring the experience of bereaved caregivers of older adults with AML and identify clinical implications for oncology nurses who support these caregivers in survivorship and bereavement.

Methods

This study was part of the control arm of a nurse-led palliative and supportive care intervention study for patients with AML aged 60 years or older receiving hypomethylating agents and venetoclax treatment and their caregivers. Since the study began in September 2020 and ended in September 2021, a total of 20 patients and 14 caregivers were enrolled. Three patients who received hypomethylating agents and venetoclax therapy died during study follow-up, all were survived by their caregivers. Of these three caregivers, two (one wife and one daughter) consented to be interviewed three to six months into their bereavement. Both caregivers were in their 60s, female, and white or non-Hispanic with college degrees. An oncology nurse conducted the one-on-one, semi-structured telephone interviews, which were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Interviews focused on caregiving needs, challenges, and priorities, from diagnosis through end-of-life, and how they viewed their caregiving experiences in bereavement. This study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Findings

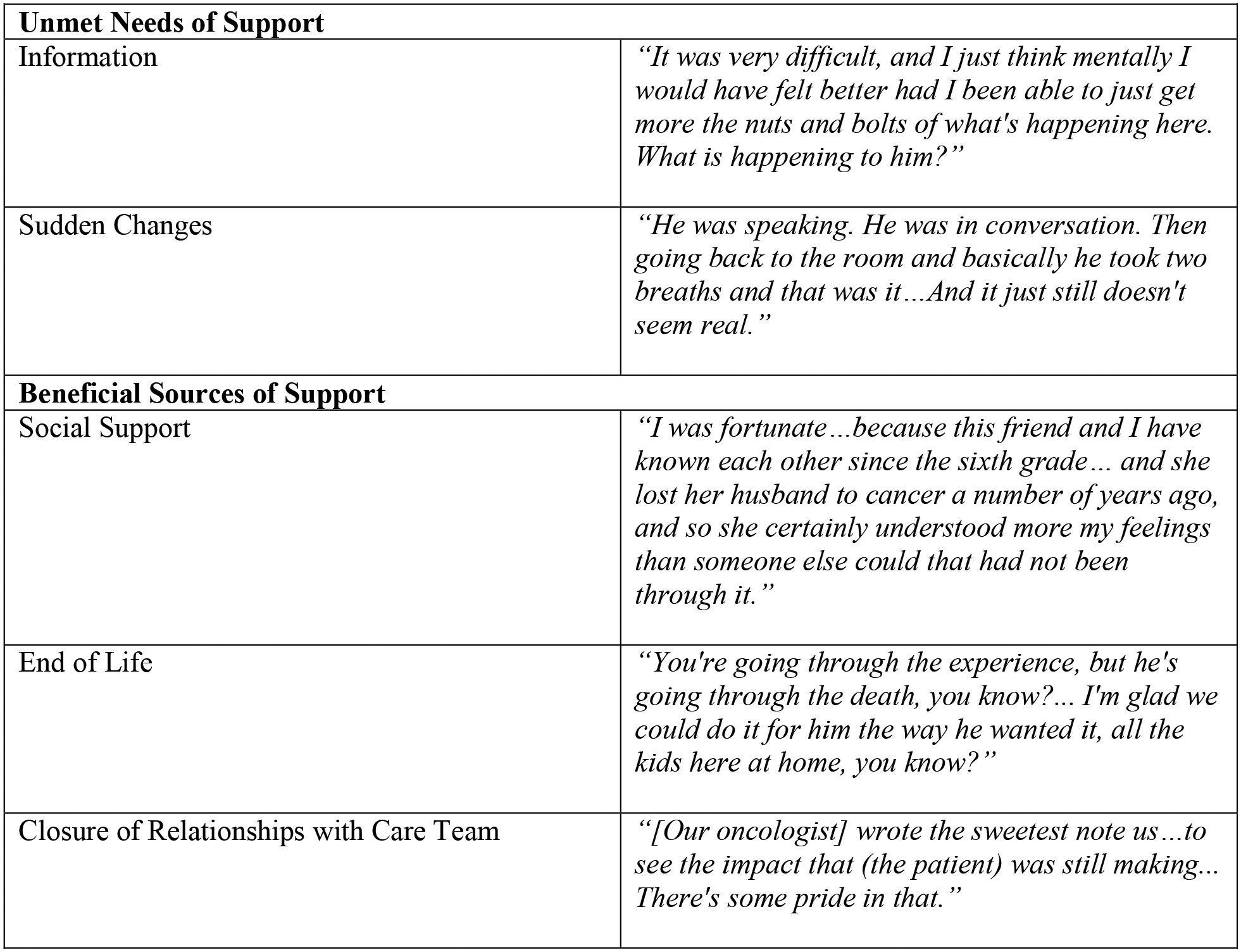

During the interviews, the caregivers described unmet supportive care needs, as well as beneficial sources of support. Figure 1 summarizes the participants’ statements.

Figure 1.

Themes and quotations from caregivers about unmet needs and sources of bereavement support

Unmet needs for support

Information

One caregiver reflected on the difficulty in gaining an understanding of the pathophysiologic processes involved with the disease and treatment for AML. She described providers’ information as either too basic or too complex.

Both bereaved caregivers expressed they had different information needs than the patient at the time of diagnosis and during treatment. One caregiver recalled she wanted to ask more questions during the office visits but refrained because her loved one was not interested in receiving that same level of information.

Sudden Changes

One caregiver described feeling disoriented while their loved one’s condition acutely deteriorated in the days prior to his sudden and unanticipated death. Both caregivers expressed feeling unprepared for the dramatic changes in their loved ones’ presentations near end-of-life. They recalled being in a state of disbelief, shock, and confusion toward the diagnosis of AML, noting their loved ones had been in their standard state of health prior to the discovery of their disease.

Beneficial sources of support

Social Support

Both caregivers acknowledged that supportive friends, extended family, neighbors, and church members helped to shoulder the burdens they faced. Although they appreciated help with simple tasks, such as collecting mail, the caregivers described deeper value in more nuanced support, such as connecting with a close friend who had experienced a similar loss.

End of Life

Goals of care discussions were characterized as selfless experiences for both caregivers, as supporting their loved ones’ wishes took precedence over their own needs. Both caregivers reflected on the individual end-of-life care plan, and how it was the right decision for their respective decedent, and expressed pride in ensuring their loved ones’ preferences were honored.

Closure with care team

Both caregivers reflected on the importance of relationships developed between their loved one and the healthcare team. Personalized, genuine expressions of condolences from their healthcare team via telephone calls and handwritten cards were particularly meaningful.

Discussion

These two interviews offer insights into caregiving from the perspective of bereavement. Although recollection does not provide the same level of accuracy as information given in real time, the qualitative findings represent what mattered most to caregivers in retrospect. Oncology nurses may value these firsthand accounts of unmet needs as well as supportive factors that comforted caregivers in their grief and helped them find meaning in their caregiving experiences.

These findings align with evidence that caregivers for patients with hematologic malignancies have individualized information needs, such as expected disease trajectories, how to be effective information brokers, managing the uncertainty of AML, and their own self-care (Booth et al., 2019; Crotty et al., 2020). This specific information can help caregivers cope and perform their roles well (Creedle et al., 2012). A study by Sklenarova et al (2015) identified that a need for helpful information is one of the major concerns of caregivers for cancer survivors, with providers challenged to provide the right amount of information without overwhelming or impairing the patient or caregiver’s ability to make informed decisions.

Another shortcoming described in interviews was lack of preparation for distressing events, such as patient condition declines resulting in intensive care or transition to comfort care. This finding aligns with research that characterize caregivers’ heightened distress in response to diagnosis and the unpredictable rapid declines, remissions, and relapses common in AML as disorienting or surreal (Button et al., 2016; Holtslander et al., 2017; LeBlanc et al., 2017). Even when death is expected, these emotional responses can occur when a caregiver learns that death is imminent or happening sooner than expected, which can inhibit their ability to absorb new information (Holtslander et al., 2017; LeBlanc et al., 2017). AML is unpredictable, so it is often difficult for providers to anticipate sudden changes to prepare caregivers or complete a timely referral to palliative care (Button et al., 2016). Navigating the tumultuous events becomes the burden of the caregiver, highlighting the importance of provider awareness of and response to distress with effective communication and compassion.

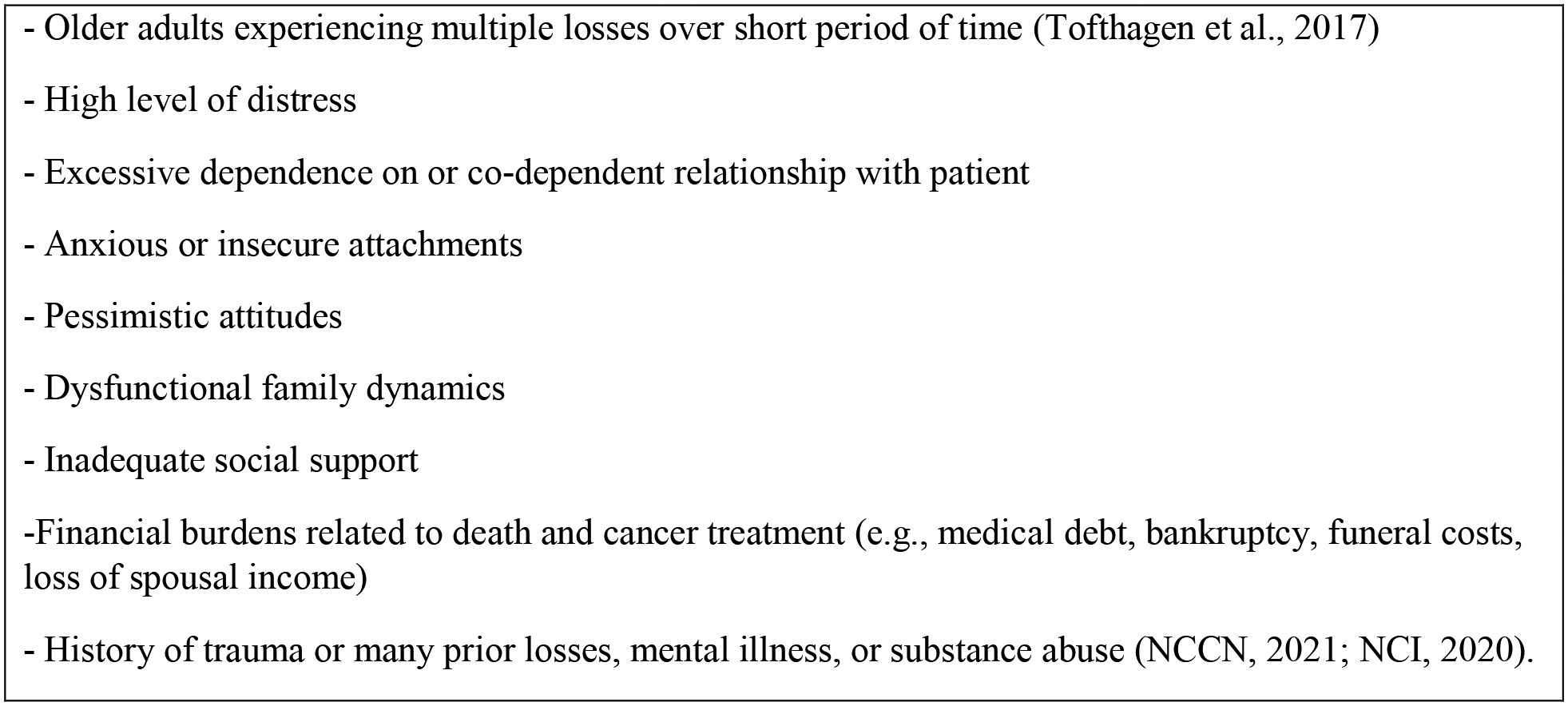

The study’s findings also align with research identifying social connection with friends or family members who are experiencing or have experienced similar caregiving situations, disease processes, or loss. These connections can serve as a protective factors against complicated grief in cancer caregiving (Boucher et al., 2018; Holtslander et al., 2017) (see Figure 2). In the interviews, caregivers described a sense of pride in their caretaking abilities and in supporting their loved one’s goals of care at the end of life. This is consistent with qualitative findings from bereaved caregivers of those with hematological malignancies (McCaughan et al., 2019).

Figure 2:

Risk factors for complicated grieving

Note. Based on information from Holtslander, 2008; National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2021a; Tofthagen et al., 2017.

At the conclusion of both interviews, the bereaved caregivers expressed that talking about their experiences helped them develop new appreciation for the challenges they overcame and the strengths they developed throughout their caregiving journey. Although the intent of the interview was to gain caregiver perspectives, caregivers may have gained a therapeutic benefit from sharing their narratives with an empathic, oncology-trained nurse. Petursdottir et al. (2020) provided evidence that a postdeath 60- to 90-minute therapeutic conversation between a caregiver and an advanced practice palliative nurse was beneficial in decreasing distress associated with grief. It is important to note that the interviewer in the current study was not part of either study participant’s care team; therefore, these findings do not shed light on potential benefits of provider continuity in bereavement care. However, the value of continuity in postdeath supportive care could be explored in future studies because research suggests that strong bonds among oncology care teams, patients and caregivers may correlate to better caregiver bereavement outcomes (An et al. 2020; Trevino et al. 2015).

Both caregivers expressed that participating in the interview provided a sense of purpose in their grief because their insights may help improve future caregivers’ experiences. Haase et al. (2021) highlighted how caregivers appreciate opportunities to provide their perspectives in low-commitment research activities that aim to optimize care.

Implications for Practice

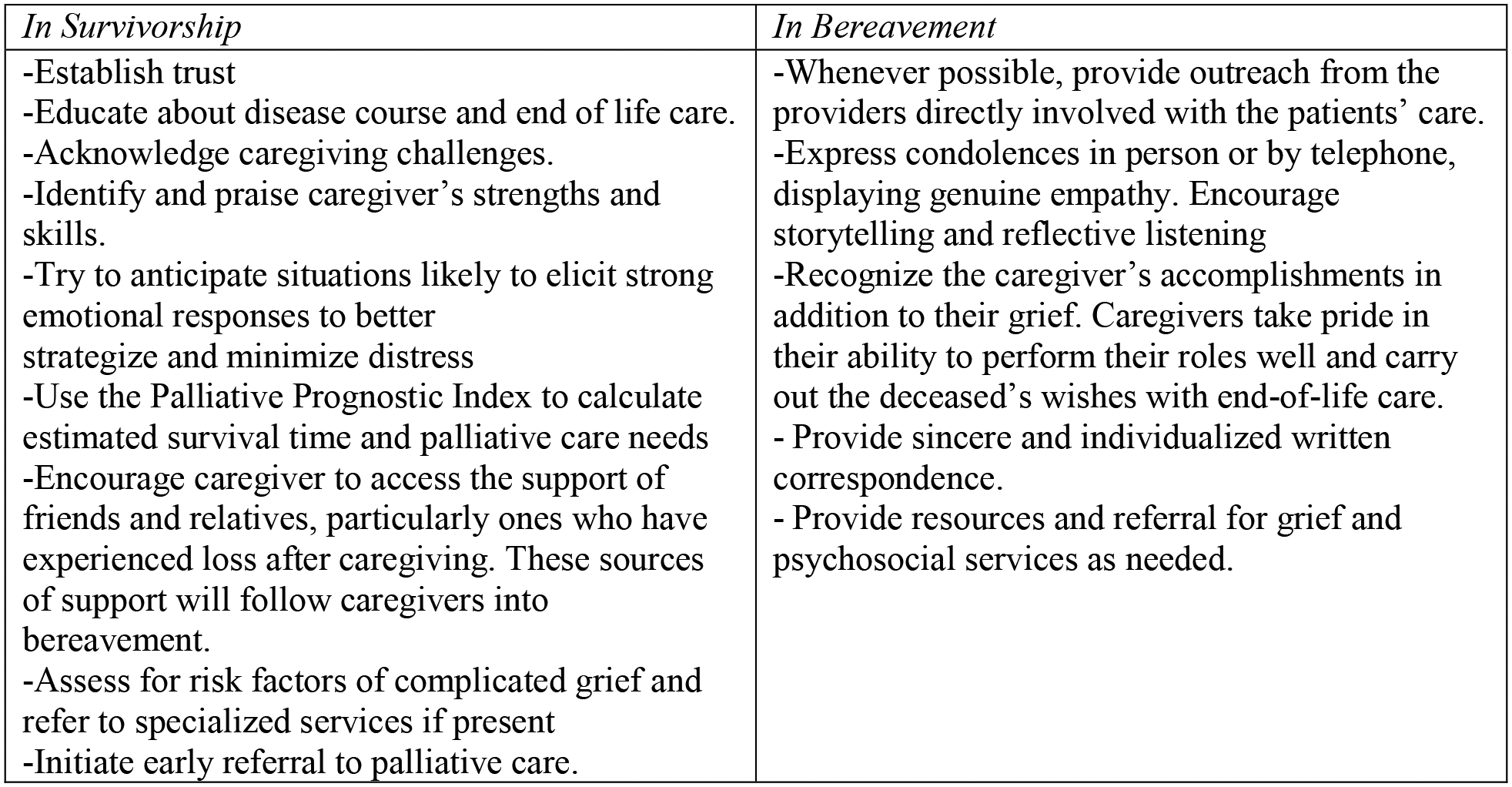

Oncology RNs and nurse practitioners are well positioned to implement and enhance programs and practices that support caregivers. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2021a; 2021b) guidelines for palliative care and distress management recommend some interventions to support caregivers, yet dedicated guidelines for bereavement care are lacking. It is important to acknowledge barriers to expanding support to caregivers. Healthcare delivery systems rarely offer incentives for the clinical provision of caregiver support or bereavement care (Holtslander and McMillan, 2011; Kent et al., 2016; Tofthagen et al., 2017). Logistical barriers also include inadequate time, staffing, or funding through insurance billing or other sources. However, insights gained from conversations with bereaved caregivers may help improve the quality of oncology care, enhance training initiatives, and inform the development of evidence-based interventions (Donnelly et al., 2018). Although interventions for oncology and palliative care are targeted before loss, the current the current study’s findings indicate that nursing involvement in bereavement care before and after loss is particularly important for caregivers coping with AML (see Figure 3).

Figure 3:

Interventions to support caregivers of older adults with cancer

Note. Based on information from An et al., 2020; Button et al., 2016; Donnelly et al., 2018; Holtslander, 2008; Holtslander et al., 2017; Mah et al., 2021; National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2021b; Rodenbach et al., 2019; Tofthagen et al., 2017; Trevino et al., 2015.

Conclusion

Bereavement care services in the United States have traditionally been the domain of pastoral and congregational care, grief counselors, and specialized palliative care providers. However, oncology nurses and nurse practitioners are uniquely qualified to plan and implement primary palliative care interventions aimed at mitigating complications of grief and providing compassionate bereavement support. This is particularly true in the care of older adults with AML, where oncology nurses develop ongoing relationships with caregivers through frequent contact, fewer patients receive the benefit of extended palliative bereavement services, and mortality is high relative to other cancers (Storey et al., 2017; Webb et al., 2019). Oncology nurses begin planning for survivorship at diagnosis, and the findings of this study support an equal need for bereavement care planning for caregivers of older adults with AML.

Implications for Practice:

Caregivers of older adults with AML experience significant distress, unique challenges, and heavy care burden compounded by lower utilization of palliative care services.

Oncology nurses play a pivotal role in addressing caregivers’ individualized needs for information and coping during treatment for AML.

Oncology nurses are well-positioned to provide continuous support to caregivers during survivorship that promotes meaning, condolence, and closure in bereavement.

Financial Disclosures:

This research was supported by National Institutes of Nursing Research R34NR019131-01A1 GRANT # (Bryant), National Cancer Institute T32CA116339 (Tan), University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Samuel B. Kellett Future Nursing Faculty Scholarship 2021–2022 (Iadonisi), American Cancer Society Doctoral Degree Scholarship in Cancer Nursing, and University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Nursing Elizabeth Scott Carrington Nursing Scholarship 2021–2022 (Chan), the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Nursing M.L. Reynolds Gray Endowed Nursing Scholarship 2021–2022, and Gayle Collier Robbins Cancer Fund Nursing Scholarship 2021–2022 (Poor).

Contributor Information

Elissa Poor, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Chan Ya-Ning, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Katie Iadonisi, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Kelly Rebecca Tan, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Ashley Leak Bryant, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center.

References

- Albrecht TA, and Bryant AL (2019). Psychological and financial distress management in adults with acute leukemia. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 35(6), 150952. 10.1016/j.soncn.2019.150952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An AW, Ladwig S, Epstein RM, Prigerson HG, and Duberstein PR (2020). The impact of the caregiver-oncologist relationship on caregiver experiences of end-of-life care and bereavement outcomes. Supportive Care in Cancer, 28(9), 4219–4225. 10.1007/s00520-019-05185-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth A, Bell T, Halhol S, Pan S, Welch V, Merinopoulou E, … Cox A (2019). Using social media to uncover treatment experiences and decisions in patients with acute myeloid leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome who are ineligible for intensive chemotherapy: Patient-centric qualitative data analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(11), e14285. 10.2196/14285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher NA, Johnson KS, and LeBlanc TW (2018). Acute leukemia patients’ needs: qualitative findings and opportunities for early palliative care. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 55(2), 433–439. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Button E, Chan R, Chambers S, Butler J, and Yates P (2016). Signs, symptoms, and characteristics associated with end of life in people with a hematologic malignancy: A review of the literature. Oncology Nursing Forum, 43(5), E178–87. 10.1188/16.ONF.E178-E187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creedle C, Leak A, Deal AM, Walton AM, Talbert G, Riff B, and Hornback A (2012). The impact of education on caregiver burden on two inpatient oncology units. Journal of Cancer Education, 27(2), 250–256. 10.1007/s13187-011-0302-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crotty BH, Asan O, Holt J, Tyszka J, Erickson J, Stolley M, … Nattinger AB (2020). Qualitative assessment of unmet information management needs of informal cancer caregivers: Four themes to inform oncology practice. JCO clinical cancer informatics, 4, 521–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly S, Prizeman G, Coimín DÓ, Korn B, and Hynes G (2018). Voices that matter: end-of-life care in two acute hospitals from the perspective of bereaved relatives. BMC Palliative Care, 17(1), 117. 10.1186/s12904-018-0365-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover S, Rina K, Malhotra P, and Khadwal A (2019). Caregiver burden in the patients of acute myeloblastic leukemia. Indian Journal of Hematology & Blood Transfusion : An Official Journal of Indian Society of Hematology and Blood Transfusion, 35(3), 437–445. 10.1007/s12288-018-1048-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase KR, Tompson MA, Hall S, Sattar S, and Ahmed S (2021). Engaging older adults with cancer and their caregivers to set research priorities through cancer and aging research discussion sessions. Oncology Nursing Forum, 48(6), 613–622. 10.1188/21.ONF.613-622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtslander L, Baxter S, Mills K, Bocking S, Dadgostari T, Duggleby W, Duncan V, Hudson P, Ogunkorode A, and Peacock S (2017). Honoring the voices of bereaved caregivers: a Metasummary of qualitative research. BMC Palliative Care, 16(1), 48. 10.1186/s12904-017-0231-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtslander LF, and McMillan SC (2011). Depressive symptoms, grief, and complicated grief among family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer three months into bereavement. Oncology Nursing Forum, 38(1), 60–65. 10.1188/11.ONF.60-65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtslander LF (2008). Caring for bereaved family caregivers: analyzing the context of care. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 12(3), 501–506. 10.1188/08.CJON.501-506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas BA, and Pollyea DA (2019). How we use venetoclax with hypomethylating agents for the treatment of newly diagnosed patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia, 33(12), 2795–2804. 10.1038/s41375-019-0612-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehoe LA, Xu H, Duberstein P, Loh KP, Culakova E, Canin B, … Mohile SG (2019). Quality of life of caregivers of older patients with advanced cancer. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 67(5), 969–977. 10.1111/jgs.15862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent EE, Rowland JH, Northouse L, Litzelman K, Chou W-YS, Shelburne N, Timura C, O’Mara A, and Huss K (2016). Caring for caregivers and patients: Research and clinical priorities for informal cancer caregiving. Cancer, 122(13), 1987–1995. 10.1002/cncr.29939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leak Bryant A, Lee Walton A, Shaw-Kokot J, Mayer DK, and Reeve BB (2015). Patient-reported symptoms and quality of life in adults with acute leukemia: a systematic review. Oncology Nursing Forum, 42(2), E91–E101. 10.1188/15.ONF.E91-E101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc TW, Fish LJ, Bloom CT, El-Jawahri A, Davis DM, Locke SC, Steinhauser KE, and Pollak KI (2017). Patient experiences of acute myeloid leukemia: A qualitative study about diagnosis, illness understanding, and treatment decision-making. Psycho-Oncology, 26(12), 2063–2068. 10.1002/pon.4309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mah K, Swami N, Pope A, Earle CC, Krzyzanowska MK, Nissim R, Hales S, Rodin G, Hannon B, and Zimmermann C (2021). Caregiver bereavement outcomes in advanced cancer: associations with quality of death and patient age. Supportive Care in Cancer. 10.1007/s00520-021-06536-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaughan D, Roman E, Smith AG, Garry AC, Johnson MJ, Patmore RD, Howard MR, and Howell DA (2019). Perspectives of bereaved relatives of patients with haematological malignancies concerning preferred place of care and death: A qualitative study. Palliative Medicine, 33(5), 518–530. 10.1177/0269216318824525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. (2021a). NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®): Distress management [v. 2.2022]. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/distress.pdf

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. (2021b). NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®): Palliative care [v.2.2021]. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/palliative.pdf

- Petursdottir AB, Sigurdardottir V, Rayens MK, and Svavarsdottir EK (2020). The Impact of Receiving a Family-Oriented Therapeutic Conversation Intervention Before and During Bereavement Among Family Cancer Caregivers: A Nonrandomized Trial. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing : JHPN : The Official Journal of the Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association, 22(5), 383–391. 10.1097/NJH.0000000000000679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodenbach RA, Norton SA, Wittink MN, Mohile S, Prigerson HG, Duberstein PR, & Epstein RM (2019). When chemotherapy fails: Emotionally charged experiences faced by family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer. Patient Education and Counseling, 102(5), 909–915. 10.1016/j.pec.2018.12.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodin G, Deckert A, Tong E, Le LW, Rydall A, Schimmer A, Marmar CR, Lo C, and Zimmermann C (2018). Traumatic stress in patients with acute leukemia: A prospective cohort study. Psycho-Oncology, 27(2), 515–523. 10.1002/pon.4488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sklenarova H, Krümpelmann A, Haun MW, Friederich H-C, Huber J, Thomas M, Winkler EC, Herzog W, and Hartmann M (2015). When do we need to care about the caregiver? Supportive care needs, anxiety, and depression among informal caregivers of patients with cancer and cancer survivors. Cancer, 121(9), 1513–1519. 10.1002/cncr.29223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey S, Gray TF, and Bryant AL (2017). Comorbidity, Physical Function, and Quality of Life in Older Adults with Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Current Geriatrics Reports, 6(4), 247–254. 10.1007/s13670-017-0227-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofthagen CS, Kip K, Witt A, and McMillan SC (2017). Complicated grief: risk factors, interventions, and resources for oncology nurses. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 21(3), 331–337. 10.1188/17.CJON.331-337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevino KM, Maciejewski PK, Epstein AS, and Prigerson HG (2015). The lasting impact of the therapeutic alliance: Patient-oncologist alliance as a predictor of caregiver bereavement adjustment. Cancer, 121(19), 3534–3542. 10.1002/cncr.29505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb JA, LeBlanc TW, & El-Jawahri AR (2019). Integration of palliative care into acute myeloid leukemia care. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 35(6), 150959. 10.1016/j.soncn.2019.150959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]