Abstract

Patients with hypercapnic COPD appear to represent a phenotype driven by specific physiology including air trapping and mechanical disadvantage, sleep hypoventilation, and sleep apnea. Such individuals appear to be at high risk for adverse health outcomes. Home noninvasive ventilation (NIV) has been shown to have the potential to help compensate for physiological issues underlying hypercapnia. In contrast to older literature, contemporary clinical trials of home NIV have been shown to improve patient-oriented outcomes including quality of life, hospitalizations, and mortality. Advancements in the use of NIV, including the use of higher inspiratory pressures, may account for recent success. Successful practical application of home NIV thus requires an adequate understanding of patient selection, devices and modes, and strategies for titration. The emergence of telemonitoring holds promise for further improvements in patient care by facilitating titration, promoting adherence, troubleshooting issues, and possibly predicting exacerbations. Given the complexity of home NIV, clinicians and health systems might consider establishment of dedicated home ventilation programs to provide such care. In addition, incorporation of respiratory therapist expertise is likely to improve success. Traditional fee-for-service structures have been a challenge for financing such programs, but ongoing changes toward value-based care are likely to make home NIV programs more feasible.

Keywords: noninvasive ventilation, COPD, sleep, lung

Introduction

Home noninvasive ventilation (NIV) for COPD has greatly evolved over the last few decades, driven by renewed attention toward chronic care management, advancements in technology, and findings from rigorous clinical trials. Herein, an overview is provided regarding current understanding of the pathogenesis of hypercapnia and respiratory failure in COPD, along with physiological and practical aspects of NIV. Relevant clinical trials regarding home NIV are reviewed along with recent professional society clinical practice guidelines. The emerging area of telemonitoring for NIV is introduced with emphasis on future directions in optimizing treatment and detecting impending respiratory decompensation. Lastly, models of care for providing home NIV in the United States are discussed including the structure of an example clinical program.

Pathogenesis of Hypercapnia in COPD

Hypercapnia (defined as an awake PaCO2 > 45 mm Hg) has long been recognized to be present in some, but not all, patients with severe COPD. The concept that hypercapnic COPD is a distinct phenotype, and not a simple or inevitable consequence of late-stage COPD, has been illustrated in the concept of the blue bloater versus pink puffer.1 A blue bloater is conceptualized to have blunted respiratory drive leading to more hypercapnia, hypoxemia, and resulting cor pulmonale. The phenotype is often associated with obesity and sleep-disordered breathing. A pink puffer, on the other hand, is characterized as those individuals with high respiratory drive, guarding against hypercapnia but with a high work of breathing and often cachexia.

Whereas COPD is likely best characterized as a spectrum of disease attributes, available data support the concept of a hypercapnic phenotype. Analysis of participants in the National Emphysema Treatment Trial found that whereas hypercapnia was associated with worsened obstruction and hyperinflation it was also associated with higher diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide and less emphysema.2 Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) appears to interact with COPD in the development of hypercapnia. When compared to patients with either OSA alone or COPD alone, patients with COPD+OSA have higher PaCO2.3 The mechanisms for this are not clear but may be mediated by effects of COPD on OSA pathogenesis.4 Other factors that might drive toward hypercapnia include weak or ineffective respiratory muscles, increased dead space, and ventilation-perfusion issues.

Physiological changes during sleep predispose to hypercapnia, and the effects are often more pronounced in those with COPD.5 Factors driving hypercapnia during sleep include decrease in respiratory drive, skeletal muscle atonia in rapid eye movement sleep, increase in upper-airway resistance, decrease in lung volumes, and increases in auto-PEEP. Importantly, this accumulation of CO2 overnight appears to drive up daytime CO2 levels.6

Patients with COPD with chronic hypercapnia have an increased risk of severe exacerbations, reduced quality of life (QOL), and increased risk of mortality relative to those who are normocapnic.7-12 Although mechanisms of harm remain unclear, potential explanations include loss of CO2 homeostasis predisposing to decompensated hypercapnia, chronic respiratory muscle fatigue, pulmonary hypertension, myocardial depression, neurological toxicities, or immune effects of hypercapnia.13

Home Noninvasive Ventilation Basics

NIV refers to a ventilatory support strategy whereby bi-level positive airway pressure is delivered through a mask interface. In the context of acute hypercapnic respiratory failure due to COPD, NIV is considered first-line therapy as it reduces risk of intubation and mortality.14

In the context of chronic hypercapnic respiratory failure, NIV has been increasingly used over the past several decades. There are several potentially beneficial effects that address the aforementioned physiology of hypercapnic COPD, including a decrease in work of breathing, increase in tidal volume, decrease in upper-airway resistance, and a decrease in threshold loads from auto-PEEP.15,16 Whereas nocturnal NIV does not appear to improve lung function as measured by FEV1, studies have suggested that NIV might reduce hyperinflation17,18 and improve ventilation-perfusion matching.19,20 Importantly, use of NIV during sleep can improve not only sleep hypoventilation but also diurnal hypercapnia. An improved ability to characterize individual-level factors that drive a patient’s hypercapnia might help to personalize the titration of NIV.

Breaths are generally delivered as pressure-supported although fixed inspiratory times can be used. Pressure-supported breaths may be delivered only by patient spontaneous effort (ie, bi-level S, where S stands for spontaneous) or may include mandatory breaths at a backup rate if no spontaneous effort is detected (ie, bi-level S/T, where S/T stands for spontaneous/timed). Volume-assured pressure support (VAPS) is a mode where pressure-supported breaths are delivered, but the pressure is determined by the device (within limits) to achieve a set tidal volume or minute ventilation. Other modes that are used less frequently include fixed inspiratory time modes (ie, pressure or volume control) and proportional assist ventilation. To date, there are no definitive data to recommend one mode over another, although European guidelines recommend fixed pressure modes.21 The importance of a backup rate toward improvement in hypercapnia has been questioned,22 but it should be noted that more recent clinical trials have generally utilized a backup rate.23,24

There are 2 broad classes of devices that can deliver NIV: bedside bi-level machines (termed respiratory assist devices or RADs by Medicare) and noninvasive ventilators. Of note, the terminology BiPAP is often used for such devices, but is a brand name, and is often conflated with a mode of ventilation, so the term RAD might be appropriate here. RAD machines are smaller, easier to use, and less expensive, while being able to provide bi-level S/T or VAPS support. Ventilators include batteries, alarms, additional modes of ventilation including auto-titrating expiratory pressure, and ability to program several modes. However, these are more expensive and can be intimidating for patients. Unfortunately, outdated payer qualification criteria are a strong determinant of device availability, with ventilators being easier to obtain in many circumstances (Table 1). Ongoing advocacy work is attempting to align better patient needs with device capabilities.25

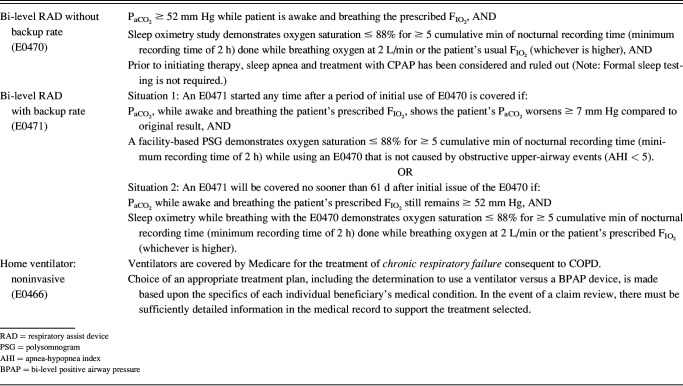

Table 1.

Medicare Qualifying Criteria for Bi-Level Respiratory Assist Devices and Home Noninvasive Ventilators as of December 2022

Mask interfaces used in home NIV have traditionally included nasal or oronasal masks, although in recent years there has been a proliferation of options. These include nasal pillows, under the nose, hybrid (oral with nasal pillows or under the nose), and total face masks. Available data suggest similar efficacy of nasal and oronasal masks, including that selecting mask based on personal preference is a reasonable approach.26,27

Clinical Trials of NIV for Chronic Respiratory Failure

Clinical trials regarding the potential role for NIV as chronic therapy for COPD started in the 1990s. Whereas these early smaller trials suggested improvements in symptoms and QOL, they were largely negative toward outcomes such as reductions in hospitalizations or mortality.28-30 More recent studies included the AVCAL study examining stable hypercapnia31 and the RESCUE study examining continued NIV following acute hypercapnic respiratory failure.32 Both of these studies were negative toward patient-oriented outcomes.

Subsequently, 2 landmark clinical trials have shown positive effects of NIV on major end points in hypercapnic COPD (both using a cutoff of an awake PaCO2 of >52 mm Hg). Kohnlein et al24 studied patients with chronic stable hypercapnia and found a reduction in one-year mortality from 33% in control group to 12% in the intervention group. Murphy et al (in the Home Oxygen Therapy - home mechanical ventilation [HOT-HMV] trial) studied patients with persistent hypercapnia 2–4 weeks after an episode of acute respiratory failure and found a reduction in composite outcome of 12-month rehospitalization and mortality (63% in the NIV group as compared with 80% in the control group). These studies are distinguished from earlier negative studies by 2 related factors: (1) the use of high-intensity NIV, including high inspiratory pressures along with relatively high backup rates; and (2) a focus on reducing persistently elevated PaCO2.

Recent clinical practice guidelines from the American Thoracic Society33 and European Respiratory Society21 based on systematic literature review support the use of home NIV in hypercapnic COPD. Similarly, the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease guidelines now include recommendation for use of home NIV. Nonetheless, uptake appears to be modest based on an analysis of Medicare data in which only ∼1% of patients with COPD and a diagnosis of chronic respiratory failure had been prescribed an NIV device.34 The reasons for apparently low use of home NIV are not well established but likely include persistent impressions prior negative studies, unawareness regarding potential benefits, and lack of routine testing for hypercapnia. Another challenge is that home NIV sits between the domains of sleep medicine and pulmonology, with variable levels of training in each specialty.

Similarly, there remain important unanswered questions needed to maximize the benefits of NIV, including therapeutic targets (eg, PaCO2 reduction or others), titration strategies, adherence goals, and management in the setting of comorbidities such as obesity and heart failure. In addition, high-intensity NIV might not be necessary for every patient. Populations outside those in high-intensity NIV studies (eg, including those with milder hypercapnia, those with concurrent OSA or severe obesity) might, nonetheless, benefit from low-intensity NIV or other ventilatory assistance such as home heated high flow.35

Telemonitoring of NIV

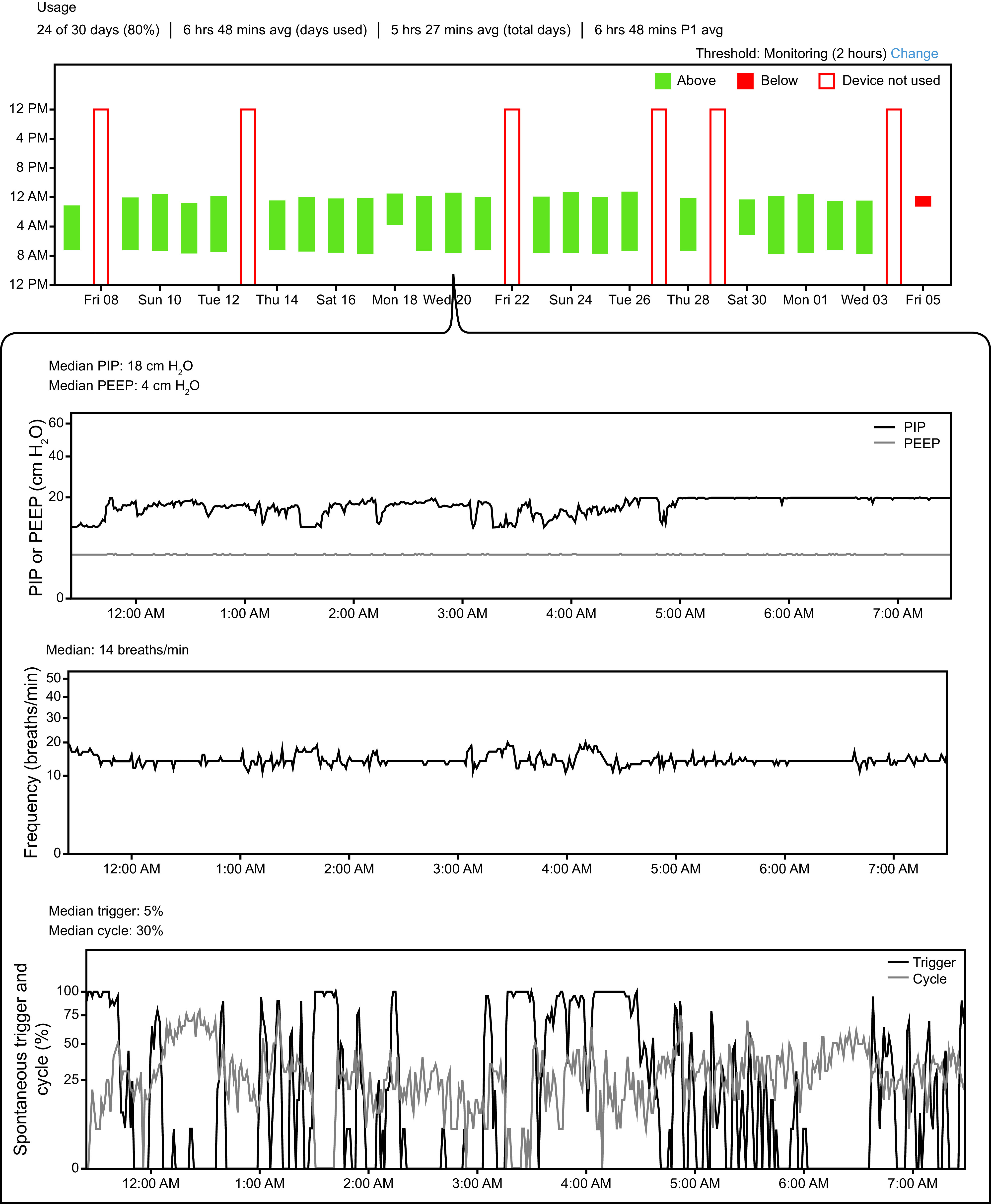

The ability for newer ventilators and RAD machines to monitor, store, and remotely transmit data is ushering in a new era for home NIV. Clinicians are able to use web-based platforms to view adherence, leak, breathing frequencies, tidal volumes, and many other parameters (Fig. 1). For many RADs, these web interfaces also allow remote adjustment of device setting.

Fig. 1.

Example telemonitoring data from patient with severe hypercapnic COPD using volume-assured pressure support noninvasive ventilation. Top panel shows daily/nightly use over a 30-d window. Inset shows data from a single night’s use, including observed pressures, breathing frequency, and percent spontaneously triggered and cycled breaths. Other available data not shown include tidal volume, apnea and hypopnea counts, unintentional leak, inspiratory and expiratory times, and peak inspiratory flow. PIP = peak inspiratory pressure.

Clinical trials support the utility of telemonitoring for the initiation and titration of NIV in patients with COPD. Duiverman et al36 compared in-hospital titration of NIV versus home titrating using telemonitoring tools in 67 subjects with stable hypercapnic COPD over 6 months. Improvements in blood gasses and QOL were not different between groups, and home titration was substantially less expensive. A smaller study examining 14 subjects with hypercapnic COPD with comorbid OSA supported similar outcomes with polysomnogram-based titration compared to more limited respiratory monitoring.37 Since ventilatory needs may change over time, telemonitoring is particularly suited not just for initiation but also for long term care, whereas routine hospitalizations or polysomnography (PSG) for titration is not likely to be tenable.

There is growing interest in using telemonitoring data as an early detection tool for impending adverse health events including COPD exacerbations. One study found that increasing breathing frequency determined from remote NIV monitoring strongly predicted COPD exacerbations.38 Questions remain as to how to implement such remote monitoring programs and the potential adverse effects of false-positive and false-negative alarms.

Establishing Home NIV Programs

Traditional fee-for-service insurance has focused on discreet interactions with the health care system, such as hospitalizations, office visits, and intermittent diagnostic testing. As such, it has been challenging to deliver complex and ongoing home-based therapies such as NIV. More recently, the concept of value-based care and incentives or penalties based on quality metrics has spurned health systems to allocate separate resources toward population health, such as internal programs aimed at reducing COPD readmissions. Furthermore, Medicare has implemented reimbursement for services such as telemedicine, chronic care coordination services, and remote patient monitoring. These care model innovations are likely to help make programs in home NIV much more feasible.

Nonetheless, a major unmet need is that there is no payer provision for out-patient respiratory care services. Durable medical equipment (DME) company reimbursement is tied solely to providing and maintaining equipment. Respiratory care may be furnished as part of home health care if the patient qualifies on the basis of being homebound with other needs such as skilled nursing care or physical therapy.

To illustrate a potential structure for a home NIV program, we describe the UC San Diego Pulmonary Neuromuscular and Assisted Ventilation Program. The program was started in 2015, mainly based on an increasing need to care for patients with restrictive lung disease and chronic respiratory failure complicating neuromuscular disease. Based on aforementioned studies indicating that home NIV can improve outcomes in COPD, the program began seeing patients with hypercapnic COPD.

Consultations are provided by 2 faculty physicians with a specific interest in home mechanical ventilation and chronic respiratory failure. Other key program staff include 2 respiratory therapists (RTs) who work exclusively in home mechanical ventilation, along with medical assistants and registered nurses shared with other physicians in the clinic. Financial support for the RT is shared between the health system, Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, and the Department of Neurology. RTs in particular play a vital role based on their ability to perform a focused assessment, provide patient education, and assist with devices/equipment.

NIV is generally initiated on an out-patient basis, with empiric settings following device manufacturer recommendations. Equipment is provided via the DME company contracted with the patient’s insurance. Remote monitoring services are specifically requested for all patients, and these data are heavily used for titration and troubleshooting. A sleep laboratory is available onsite. Diagnostic PSG is only utilized when additional information is needed to make treatment decisions (eg, when hypercapnia does not appear to be explained by severity of COPD or suspicion for concurrent sleep disorder). PSG with titration is utilized when issues remain despite troubleshooting with remote monitoring data. In this circumstance, the major utility appears to be in diagnosing issues such as patient-device asynchrony or underappreciated difficulties with mask leaks rather than in making major setting adjustments.

The program incorporates several of the aforementioned care model innovations. Telemedicine visits are often utilized for patients with mobility or transportation issues and for acute issues on days where faculty are not onsite at the clinic. RTs will also perform telemedicine visits with patients who are newly starting NIV, those having equipment issues, or needing education. For these visits, the RT will document the encounter and contact the physicians with updates or to review and sign off on any potential changes.

Summary

Patients with hypercapnic COPD represent a physiological phenotype who are at high risk for adverse health outcomes. Over the last several years, home NIV has been shown to improve patient-oriented outcomes including QOL, hospitalizations, and mortality. However, the practical application of home NIV requires an adequate understanding of patient selection, devices and modes, and strategies for titration. The emergence of telemonitoring holds promise for further improvements in patient care. Clinicians and health systems might consider establishment of dedicated home ventilation programs to provide such care, which are likely to benefit from RT expertise. A move toward value-based care and other systems innovations may help to provide adequate resources for such programs.

Discussion

MacIntyre: Thank you Jeremy. Nice review. First an editorial comment, respiratory assist devices have no definition. The FDA does not recognize it as a separate category, but respiratory assist devices and ventilators are treated by the FDA as ventilators, period. In thinking about it, it’s really hard for me to figure out what defines a respiratory assist device and what defines a ventilator. Low-income countries use BPAP devices as full-fledged ICU vents, and it’s an ill-defined area that I think adds to the confusion of trying to establish criteria. Let me ask you a physiology question that still confuses me. In the ICU when you have a patient in acute hypercapnic respiratory failure, as I touched on yesterday, one of the approaches to reduce air trapping is to reduce minute ventilation, reduce breathing frequency, and reduce the VT to allow better emptying of the lung. Yet in the home, somehow the reverse philosophy occurs. The Germans say you need these really high pressures and really high volumes and claim that that reduces hyperinflation. I don’t get it, and I’ve asked the Europeans, and they’ve given me the answer that says, “well the acutely injured patient will respond to reduced minute ventilation and reduced air trapping, whereas the chronic patient sometimes needs high pressures to get rid of air trapping,” which really isn’t an answer. Maybe you can help me understand why the physiology is reversed in the home.

Orr: Well, I think in the ICU you have the ability to intubate and sedate somebody. I tell my fellows that we can all talk about these ventilator modes, but we’re missing half of the equation, which is the patient’s brain stem and perhaps stuff that’s going on above the brain stem. Do you reduce minute ventilation with NIV in the hospital acutely? I don’t think you do, but you do reduce work of breathing (WOB). Do you reduce air trapping in the acute setting with NIV? I don’t know that anybody has ever looked at that; you may just be waiting for the meds to kick in to reduce the air trapping. But from the physiologic standpoint, we know that the pattern of breathing matters when it comes to air trapping in terms inspiratory time and flow. So one thing that NIV helps to do when the patient has a fatigued diaphragm is get them larger VT in a shorter period of time. I don’t think we’ve looked at this pattern of breathing enough. That may be the mechanism by which it helps in home NIV as well is the pattern of breathing driving larger VT. And in total it’s augmenting ventilation, but it’s also making big changes to the pattern of breathing. It’s not well reported. I would say these patients already have pretty low breathing frequencies; they’re not rapid shallow breathing. Again, I think we need much more physiologic information. It probably depends on the patients and how much air trapping do they have and how much of this hypoventilation that they have at home is driven by upper-airway obstruction and how much is driven by diaphragm weakness and things like that. It’s probably a pretty heterogenous group.

MacIntyre: The follow-up to that is, do you believe we have to blow the PaCO2 down to get a benefit from NIV in these patients or simply, if you’ll pardon the expression, resting the diaphragm or unloading the diaphragm? Even though the PaCO2 doesn’t change, the work to generate that level of alveolar ventilation is less; and theoretically by resting the diaphragm, it will function better during the day even though the PaCO2 hasn’t changed.

Orr: That’s a great question, and I will try to answer it. First of all, I would say that the trials that have been positive have been the ones that reduce the PaCO2. Now, is that a direct effect of PaCO2 reduction, or is it just a marker of effective therapy in terms of reducing WOB? I don’t know, and it is difficult to disentangle. There was at least one observational study a year or so ago that found that the reduction of PaCO2 was not predictive of a mortality benefit. On the other hand, CO2 is probably underappreciated in terms of its biologic effects. Physicians often say a little bit of hypercapnia when you put someone on O2 isn’t a problem. They’re not in acute respiratory failure, and you put them on O2, and their PaCO2 rose 5 mm Hg, so no problem. Is that really true? Of course, just because a patient looks fine doesn’t mean that they are. CO2 is a very potent signaling molecule. There have been a number of studies looking at neuronal function and glutamate signaling with hypercapnia, studies looking at immune function, and studies looking at pulmonary hypertension and the interaction between hypoxemia and hypercapnia. So I think it’s biologically plausible that you need to reduce PaCO2 to see the benefit. Do you need to reduce PaCO2 to get at least some reduction in WOB? Probably not. You can probably set the NIV such that you maintain their spontaneous eupneic ventilation, whereby almost all the work is being done by the device. If you wanted to reduce the PaCO2, you would need to increase further the NIV settings, but the WOB was already quite low. So it might be possible to just reduce WOB without changing PaCO2 much. But you need to measure the WOB and then titrate the NIV, and the settings required still might be fairly high. One thing I will point out is that you can’t just say that it looks like they aren’t working that hard to breathe. I don’t think that’s as good of a measure as people think it might be.

*Dean Hess: The CPG that you, Rich, and I helped to write addressed that as one of our PICO questions.1 We suggested to target normalization of PaCO2 when starting these patients on NIV. To change the subject, I hope that in your paper you will describe the program that you put together in your hospital. I’m very impressed by that. I think that many hospitals struggle with how to do this, and you could help a lot of folks by describing how you put that together, how it works, the interaction with the durable medical equipment (DME) companies. I agree 100% that if you turn everything over to the DME that’s not the right solution. And I think you’ve found the solution, which is to have your hospital-based RTs dealing directly face-to-face with the DME companies while they’re there in the home, and we now have the technology to do it; we can do it quite simply with FaceTime or Zoom. I hope you will describe your program in detail because it will help a lot of people.

Orr: I’ll say again that I didn’t start out with the vision of what we were going to do. It came after that fact that we realized the resources that we were lacking. I think that is not the way to do things, and I can tell you now what I think one needs to run a home mechanical ventilation program. The major outstanding question is really where the money is going to come from, and we still haven’t answered that. I’ve cobbled together support for respiratory care in the clinic. I worry every year that the admins are going to decide to pull our support or get in a battle regarding who is financially responsible. I will say that our RTs do a lot of work in terms of transitioning patients out of the hospital, so it is reasonable to look at this as a service to the health system. These are the patients who are hypercapnic, and we’re worried about readmissions. I would say that you want to think about all the broader services a COPD patient might need and try to really integrate with that, including readmission reduction programs. Andy Ries suggested that to me that maybe we should integrate under pulmonary rehab and maybe that could be its home, and that’s something we haven’t yet explored. A lot of these patients do benefit from pulmonary rehab, and there’s at least one trial showing that the combination of the two can be quite potent. We’ve accomplished a decent amount. I’m not sure we have the optimal solution, but it’s a viable initial solution.

MacIntyre: Going back to Dean’s comment about lowering PaCO2, the Germans advocate that to do that you have to titrate these patients in the hospital with frequent blood gas monitoring. Is that what you’re proposing?

*Dean Hess: No, and what they do is, I think, unworkable in the United States because they admit these patients to the hospital for up to 5 d to initiate this therapy before they go back home. And correct me if I’m wrong, Jeremy and Rich, but I believe in our CPG we said something to the effect that it does not have to be high-intensive therapy. The goal should be reduced arterial PCO2, but we do not have to follow the German model. I believe we have language to that effect.

MacIntyre: So how do you monitor CO2 if they’re in the home?

*Dean Hess: That’s a good question. One approach that has been used is PtcCO2. Capnography is not the solution for physiologic reasons because these patients have high VD/VT and so forth. And it might require intermittent clinic visits for blood draws.

Orr: Yes, the ERS had a guideline2 on home NIV that came out less than a year before ours came out.6 And ERS must not limit them in terms of the number of PICO questions because they had a lot, maybe 15 or so. One of them was, where should NIV be initiated? There is disagreement between the ATS and ERS guidelines on that. The ERS guidelines state that during an exacerbation of COPD with acute hypercapnic respiratory failure that NIV should be initiated in the hospital. The idea is you get through the ICU, you’re out of acute respiratory failure, and you’re weaning them off but transitioning them to the mode of nocturnal therapy and titrating. Again, our guideline based on the Murphy study said some of those patients don’t need NIV. I’ll say that there are plenty of patients who come in who you are very sure that they don’t have transient hypercapnia because you see their bicarbonate level has been 37 for years. And their PaCO2 is 100 or 85 when they came in the hospital, and there’s no way they’re normalizing that. So I think there are patients who in theory you don’t need to wait to titrate, but there’s still a question as to what’s the best setting. I have to say that even though our in-patient RTs are very good with acute NIV, their familiarity with home NIV is less as far as targets of therapy and things like that. There are different mask interfaces; you probably have 2 interfaces in your hospital, a nasal mask or an oronasal mask. On the out-patient side, we have 30 different options; and we use them, including nasal pillows and things like that. Different equipment. I don’t know what you have in your hospital, but there’s a good chance that you don’t have the same devices that might be used at home. You may not have a VAPS device, for example, or even a bi-level S/T device. Then there’s the question of is it worth prolonging their hospitalization for several days while you titrate? There are other potential downsides, like slapping a mask on someone who just went through a very traumatic experience of acute respiratory failure and then saying, “Now you get to use this for the rest of your life.” Maybe we should let things cool off for a few weeks and revisit this on the out-patient side. We really try to avoid doing hospital titration. The data from the Duiverman study3 in Denmark showed that home titration with remote patient monitoring was effective in CO2 reduction. So I think that’s reasonable to do and in many settings is preferable, but you can’t lose track of them. That’s the big key, there is a lot of these patients they get discharged and when is their next visit? It has to be part of this pathway of taking care of COPD patients through the whole spectrum.

*Dean Hess: If we’re targeting a reduction in PaCO2, as you pointed out in your presentation, we have to use higher settings than we have typically used in the past. We’re not going to get there with 8/4 or 10/5. The other thing is thinking about this as a long-term treatment. In the hospital we start NIV, and we draw a blood gas in an hour. That’s not what we’re doing with these patients. I think we should be looking at reducing PaCO2 over time. This is weeks or months of time, so how we measure the PaCO2 is not like we do in the hospital where we’re looking for that immediate reduction.

Orr: We will start therapy and titrate even over the course of several months and will check PaCO2.

*Dean Hess : So you might get a blood gas in the clinic after a few months.

Orr: Right. I’m not going to take a blood gas if they’re not using the device or they’re not on effective settings. It’s going to maybe take some time to get there. With respect to titration, it is slower on the out-patient side. In fact, the data from that Duiverman study3 show that as well, that CO2 reduction may be a bit slower. And that may be fine. There’s a downside of trying to get things titrated too quickly with that high-intensity strategy. One of the risks if you provide people with a high pressure early on a lot of times they don’t tolerate it, and in fact, it can start to cause problems with patient-ventilator asynchrony. You do have to follow these patients pretty closely. The issue I tend to see with the sleep lab is that the goals of titration are not clear or maybe a little misplaced. A lot of times in the sleep lab they’ve read one of these papers and they realize high intensity is what you have to do, and then the technician is told to get the pressure up to 20 cm the first night, and it never works. You have to be careful with the sleep lab-based titrations, and I really try to avoid them because they can cause more problems than they solve. That’s not an insult to the sleep lab folks, but they typically have a different area of focus. There are some nice reviews that highlight these topics and the art of titrating home NIV.

Mike Hess: Could it be feasible to integrate end-tidal monitoring as a remote monitoring parameter?

Orr: The issue with end-tidal is 2-fold. One is in COPD because of increased dead space it may not reflect what you think it does. But perhaps it could be something you could follow over time as a trend. But the other major issue with end-tidal CO2 is that all BPAP devices and most circuit configurations with home NIV are passive vented circuits. And all out-patient masks are vented. So you end up blowing CO2 out the mask, so that’s not terribly effective.

Mike Hess: It seems like there might be some kind of spot where it could work.

Orr: Most interfaces are vented right in the mask. It used to be the case that you’d use a whisper swivel in the tubing to provide venting, but not anymore. However, I do think we probably should have non-vented masks on the out-patient side; there are certain neuromuscular patients who certainly need that. We have neuromuscular patients who will glue the holes of the vents on their mask so we can provide non-vented configuration on the out-patient side with the mask that they like. That’s something we’d have to get the manufacturers on board with, and there are safety considerations obviously.

Carlin: In looking at your clinic venue, have you thought about partnering with other entities such as long-term acute care centers or critical illness recovery hospitals? I don’t know what exists in the San Diego area, but partnering with them might be an option to help given the availability of the nursing, respiratory therapy, and physical therapy staffs at those facilities.

Orr: Yes, I think depending on what resources you have available you might choose to place this program in different settings. We do have two long-term acute care centers in San Diego. I am not on staff there, but I’ve talked with them, and they’ve had some interest. But again, it takes education; this is not something that most RTs are familiar with; there’s a lot to understand in terms of the goals of therapy in terms of the equipment. I do think there should be a local center of excellence that can be a resource. I am concerned that without that, provision of NIV care not going to be very effective. I’d love to look at this, but my sense is that when NIV gets prescribed without the necessary resources and expertise what ends up happening is that the patient is on ineffective settings or not really using it.

Footnotes

Dean R Hess PhD RRT FAARC is Managing Editor of RESPIRATORY CARE.

Dr Orr discloses a relationship with ResMed (Advisory Board).

Dr Orr is supported by National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute K23-151880.

Dr Orr presented a version of this paper at the 59th Respiratory Care Journal Conference, COPD: Current Evidence and Implications for Practice, held June 21–22, 2022, in St Petersburg, Florida.

REFERENCES

- 1.Flenley DC. Sleep in chronic obstructive lung disease. Clin Chest Med 1985;6(4):651-661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathews AM, Wysham NG, Xie J, Qin X, Giovacchini CX, Ekström M, et al. Hypercapnia in advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a secondary analysis of the National Emphysema Treatment Trial. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis 2020;7(4):336-345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Resta O, Foschino Barbaro MP, Brindicci C, Nocerino MC, Caratozzolo G, Carbonara M. Hypercapnia in overlap syndrome: possible determinant factors. Sleep Breath 2002;06(1):11-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orr JE, Schmickl CN, Edwards BA, DeYoung PN, Brena R, Sun XS, et al. Pathogenesis of obstructive sleep apnea in individuals with the COPD + OSA overlap syndrome versus OSA alone. Physiol Rep 2020;8(3):e14371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Donoghue FJ, Catcheside PG, Ellis EE, Grunstein RR, Pierce RJ, Rowland LS, et al. ; Australian trial of Noninvasive Ventilation in Chronic Airflow Limitation investigators. Sleep hypoventilation in hypercapnic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence and associated factors. Eur Respir J 2003;21(6):977-984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norman RG, Goldring RM, Clain JM, Oppenheimer BW, Charney AN, Rapoport DM, et al. Transition from acute to chronic hypercapnia in patients with periodic breathing: predictions from a computer model. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2006;100(5):1733-1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang H, Xiang P, Zhang E, Guo W, Shi Y, Zhang S, et al. Is hypercapnia associated with poor prognosis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? A long-term follow-up cohort study. BMJ Open 2015;5(12):e008909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Budweiser S, Hitzl AP, Jorres RA, Schmidbauer K, Heinemann F, Pfeifer M. Health-related quality of life and long-term prognosis in chronic hypercapnic respiratory failure: a prospective survival analysis. Respir Res 2007;8(1):92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aida A, Miyamoto K, Nishimura M, Aiba M, Kira S, Kawakami Y. Prognostic value of hypercapnia in patients with chronic respiratory failure during long-term oxygen therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;158(1):188-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foucher P, Baudouin N, Merati M, Pitard A, Bonniaud P, Reybet-Degat O, et al. Relative survival analysis of 252 patients with COPD receiving long-term oxygen therapy. Chest 1998;113(6):1580-1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Almagro P, Barreiro B, Ochoa de Echagüen A, Quintana S, Rodríguez Carballeira M, Heredia JL, et al. Risk factors for hospital readmission in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiration 2006;73(3):311-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costello R, Deegan P, Fitzpatrick M, McNicholas WT. Reversible hypercapnia in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a distinct pattern of respiratory failure with a favorable prognosis. Am J Med 1997;102(3):239-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdo WF, Heunks LMA. Oxygen-induced hypercapnia in COPD: myths and facts. Crit Care 2012;16(5):323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rochwerg B, Brochard L, Elliott MW, Hess D, Hill NS, Nava S, et al. Official ERS/ATS clinical practice guidelines: noninvasive ventilation for acute respiratory failure. Eur Respir J 2017;50(2):1602426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nickol AH, Hart N, Hopkinson NS, Moxham J, Simonds A, Polkey MI. Mechanisms of improvement of respiratory failure in patients with restrictive thoracic disease treated with noninvasive ventilation. Thorax 2005;60(9):754-760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nava S, Ambrosino N, Rubini F, Fracchia C, Rampulla C, Torri G, et al. Effect of nasal pressure support ventilation and external PEEP on diaphragmatic activity in patients with severe stable COPD. Chest 1993;103(1):143-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Budweiser S, Heinemann F, Fischer W, Dobroschke J, Pfeifer M. Long-term reduction of hyperinflation in stable COPD by noninvasive nocturnal home ventilation. Respir Med 2005;99(8):976-984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diaz O, Begin P, Torrealba B, Jover E, Lisboa C. Effects of noninvasive ventilation on lung hyperinflation in stable hypercapnic COPD. Eur Respir J 2002;20(6):1490-1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Backer L, Vos W, Dieriks B, Daems D, Verhulst S, Vinchurkar S, et al. The effects of long-term noninvasive ventilation in hypercapnic COPD patients: a randomized controlled pilot study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2011;6:615-624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hajian B, De Backer J, Sneyers C, Ferreira F, Barboza KC, Leemans G, et al. Pathophysiological mechanism of long-term noninvasive ventilation in stable hypercapnic patients with COPD using functional respiratory imaging. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2017;12:2197-2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ergan B, Oczkowski S, Rochwerg B, Carlucci A, Chatwin M, Clini E, et al. European Respiratory Society guidelines on long-term home noninvasive ventilation for management of COPD. Eur Respir J 2019;54(3):1901003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murphy PB, Brignall K, Moxham J, Polkey MI, Davidson AC, Hart N. High-pressure versus high-intensity noninvasive ventilation in stable hypercapnic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized crossover trial. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2012;7:811-818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murphy PB, Rehal S, Arbane G, Bourke S, Calverley PMA, Crook AM, et al. Effect of home noninvasive ventilation with oxygen therapy vs oxygen therapy alone on hospital readmission or death after an acute COPD exacerbation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017;317(21):2177-2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohnlein T, Windisch W, Kohler D, Drabik A, Geiseler J, Hartl S, et al. Noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation for the treatment of severe stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a prospective, multi-center, randomized, controlled clinical trial. Lancet Respir Med 2014;2(9):698-705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hill NS, Criner GJ, Branson RD, Celli BR, MacIntyre NR, Sergew A, et al. Optimal NIV Medicare access promotion: patients with COPD: a technical expert panel report from the American College of Chest Physicians, the American Association for Respiratory Care, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, and the American Thoracic Society. Chest 2021;160(5):e389-e397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Majorski DS, Callegari JC, Schwarz SB, Magnet FS, Majorski R, Storre JH, et al. Oronasal versus nasal masks for noninvasive ventilation in COPD: a randomized crossover trial. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2021;16:771-781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lebret M, Léotard A, Pépin JL, Windisch W, Ekkernkamp E, Pallero M, et al. Nasal versus oronasal masks for home noninvasive ventilation in patients with chronic hypercapnia: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Thorax 2021;76(11):1108-1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clini E, Sturani C, Rossi A, Viaggi S, Corrado A, Donner CF, et al. ; Rehabilitation and Chronic Care Study Group, Italian Association of Hospital Pulmonologists (AIPO). The Italian multi-center study on noninvasive ventilation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Eur Respir J 2002;20(3):529-538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsolaki V, Pastaka C, Karetsi E, Zygoulis P, Koutsokera A, Gourgoulianis KI, et al. One-year noninvasive ventilation in chronic hypercapnic COPD: effect on quality of life. Respir Med 2008;102(6):904-911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Casanova C, Celli BR, Tost L, Soriano E, Abreu J, Velasco V, et al. Long-term controlled trial of nocturnal nasal positive-pressure ventilation in patients with severe COPD. Chest 2000;118(6):1582-1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McEvoy RD, Pierce RJ, Hillman D, Esterman A, Ellis EE, Catcheside PG, et al. ; Australian trial of noninvasive Ventilation in Chronic Airflow Limitation (AVCAL) Study Group. Nocturnal noninvasive nasal ventilation in stable hypercapnic COPD: a randomized controlled trial. Thorax 2009;64(7):561-566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Struik FM, Sprooten RT, Kerstjens HA, Bladder G, Zijnen M, Asin J, et al. Nocturnal noninvasive ventilation in COPD patients with prolonged hypercapnia after ventilatory support for acute respiratory failure: a randomized controlled, parallel-group study. Thorax 2014;69(9):826-834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Macrea M, Oczkowski S, Rochwerg B, Branson RD, Celli B, Coleman JM, 3rd, et al. Long-term noninvasive ventilation in chronic stable hypercapnic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020;202(4):e74-e87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frazier WD, Murphy R, van Eijndhoven E. Noninvasive ventilation at home improves survival and decreases health care utilization in Medicare beneficiaries with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with chronic respiratory failure. Respir Med 2020;177:106291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagata K, Horie T, Chohnabayashi N, Jinta T, Tsugitomi R, Shiraki A, et al. Home high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy for stable hypercapnic COPD: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2022;206(11):1326-1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duiverman ML, Vonk JM, Bladder G, van Melle JP, Nieuwenhuis J, Hazenberg A, et al. Home initiation of chronic noninvasive ventilation in COPD patients with chronic hypercapnic respiratory failure: a randomized controlled trial. Thorax 2020;75(3):244-252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patout M, Arbane G, Cuvelier A, Muir JF, Hart N, Murphy PB. Polysomnography versus limited respiratory monitoring and nurse-led titration to optimize noninvasive ventilation set-up: a pilot randomized clinical trial. Thorax 2019;74(1):83-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borel JC, Pelletier J, Taleux N, Briault A, Arnol N, Pison C, et al. Parameters recorded by software of noninvasive ventilators predict COPD exacerbation: a proof-of-concept study. Thorax 2015;70(3):284-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

REFERENCES

- 1.Macrea M, Oczkowski S, Rochwerg B, Branson RD, Celli B, Coleman JM, et al. Long-term noninvasive ventilation in chronic stable hypercapnic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020;202(4):e74-e87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ergan B, Oczkowski S, Rochwerg B, Carlucci A, Chatwin M, Clini E, et al. European Respiratory Society guidelines on long-term home noninvasive ventilation for management of COPD. Eur Respir J 2019;54(3):1901003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duiverman ML, Vonk JM, Bladder G, van Melle JP, Nieuwenhuis J, Hazenberg A, et al. Home initiation of chronic noninvasive ventilation in COPD patients with chronic hypercapnic respiratory failure: a randomized controlled trial. Thorax 2020;75(3):244- 252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]