Abstract

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease is the most common inherited cause of end stage kidney disease worldwide. Most cases result from mutation of either of two genes, PKD1 and PKD2, which encode proteins that form a probable receptor/channel complex. Studies suggest that a loss of function of the complex below an indeterminate threshold triggers cyst initiation, which ultimately results in dysregulation of multiple metabolic processes and downstream pathways and subsequent cyst growth. Non-cell autonomous factors may also promote cyst growth. In this report, we focus primarily on the process of early cyst formation and factors that contribute to its variability with brief consideration of how new studies suggest this process may be reversible.

Clinical Summary

Most cases of ADPKD result from germline mutations that either reduce or inactivate PKD1 or PKD2 gene function.

The PKD1- and PKD2-encoded proteins, PC1 and PC2, form a probable receptor-channel complex that may serve as a sensor of tubule size/morphology and sit atop a signaling hub that controls coordination of myriad downstream pathways.

Cystic disease is the result of two distinct processes: an initiating event in which the function of either PKD1 or PKD2 falls below a critical threshold, which then triggers a switch that initiates a cascade of signaling events that result in cellular proliferation, fluid secretion and fibrosis.

PC1 and PC2 are found in primary cilia, and the C-terminus of PC1 also traffics to mitochondria where it regulates mitochondrial function.

ADPKD may be partially reversible if PC1/PC2 activity is replaced early enough in cystic disease.

Introduction

Renal cysts are common, particularly in people as they age. In most cases, they are thought to be acquired, simple cysts that have little functional significance. Clinicians and radiologists have defined properties and thresholds for what constitutes a simple cyst, a pre-malignant or malignant lesion, or a manifestation of a genetic condition1 2. There are numerous genetic causes, which often differ with respect to their pattern of inheritance, age of onset, distribution, and number of cysts. In this review, we discuss the mechanisms of cyst development in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), which is by far the most common monogenetic cause of end stage kidney disease.

When thinking about the mechanisms responsible for cystic disease, it is useful to distinguish between the processes that initiate cyst formation and those that promote cyst growth as they have implications for how one might approach therapy. In the former case, preventing cyst formation could be curative, preventing all morbidity, whereas treatment directed at drivers of cyst growth slow progression with a goal of delaying or preventing end stage kidney disease. This review will primarily focus on cyst initiation since a later chapter will review disease pathways as possible therapeutic targets.

PKD1 and PKD2

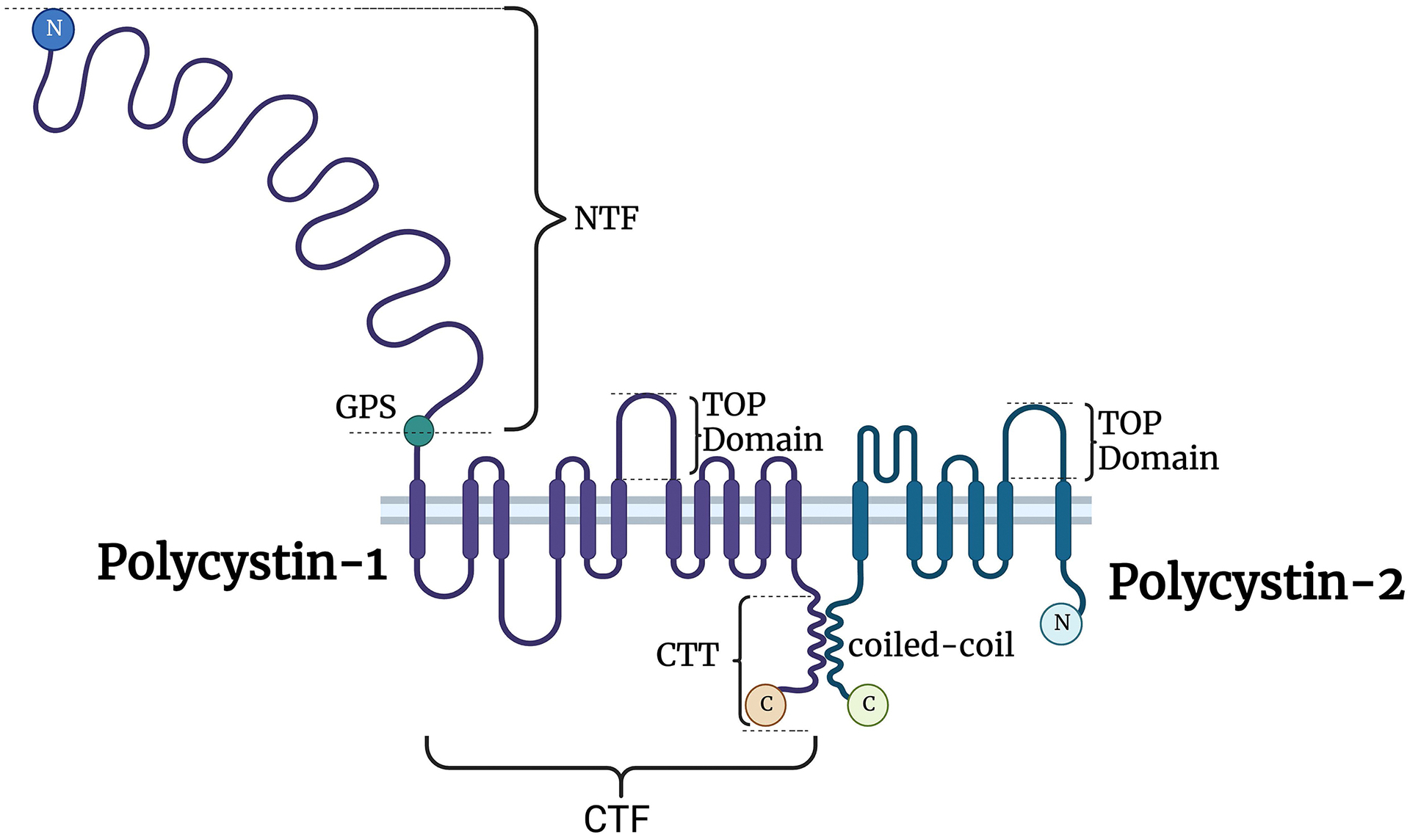

Mutations in either PKD1 or PKD2 account for >90% of all cases of ADPKD3. PKD1 encodes a transcript of approximately 14kb, which is translated into a 4302 amino acid (aa) membrane protein, polycystin-1 (PC1)4. PC1 undergoes auto-cleavage at a G-protein Proteolytic Site (GPS) to produce an N-terminal fragment (NTF) of 3048aa which remains tethered to the rest of the protein, called the C-terminal fragment (CTF)5 (Figure 1). The CTF has 11 transmembrane (TM) segments and ends with a 200aa cytoplasmic terminal “tail” (CTT)4. The GPS site is located just N-terminal to the first TM5. The protein’s localization is incompletely determined as it is present in very low abundance in most tissues and inconsistently reported6. It has been localized to the primary cilium, to apical and basolateral membranes, to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and Mitochondria-Associated Membranes (MAMs), which are mitochondria-ER contact sites7–10. Cleavage at the GPS is required for ciliary trafficking11. The CTF also undergoes cleavage at or near the last TM, possibly mediated by γ secretase, releasing the CTT which traffics to the nucleus and/or the mitochondria12–14. Based on its predicted structure and functional domains, PC1 is thought to be a receptor15, 16.

Figure 1.

Structure of PC1 and PC2. PC1 and PC2 interact through their transmembrane domains and a coiled-coil domain. PC1 is cleaved at the GPS (G-protein Proteolytic Site), producing two fragments that remain tethered: the NTF (N-terminal fragment) and CTF (C-terminal fragment). The CTF is further cleaved, generating the CTT (cytoplasmic terminal “tail”) that is thought to traffic to the nucleus and/or mitochondria. TOP, tetragonal opening for polycystins domain, is conserved in polycystins and is thought to regulate PC2 activity. Created with BioRender.com.

PKD2 encodes a transcript of ~5kb, which is translated into a 110-kDa membrane protein, polycystin-2 (PC2)17. PC2 is a member of the Transient Receptor Potential Protein (TRP) family, with six TMs, a novel polycystin-specific ‘tetragonal opening for polycystins’ (TOP) domain, a pore-forming loop, and intracellular N- and C-termini18. The TOP domain may regulate its activity. PC2 has moderately high homology with the C-terminal half of PC1’s CTF, and it is thought to be a non-selective cation channel protein, though there are inconsistent reports about its relative selectivity19, 20. It forms both homotetrameric complexes made of four PC2 subunits and heteromeric complexes composed of three PC2 and one PC1 (or PC1-like) subunits21, 22. PC2 is much more abundant than PC1 and has been unambiguously localized to the ER and primary cilium9, 23, 24. It is required for PC1 to traffic to the primary cilium, and it may also co-localize with PC1 at other locations10, 11.

Mechanism of Disease

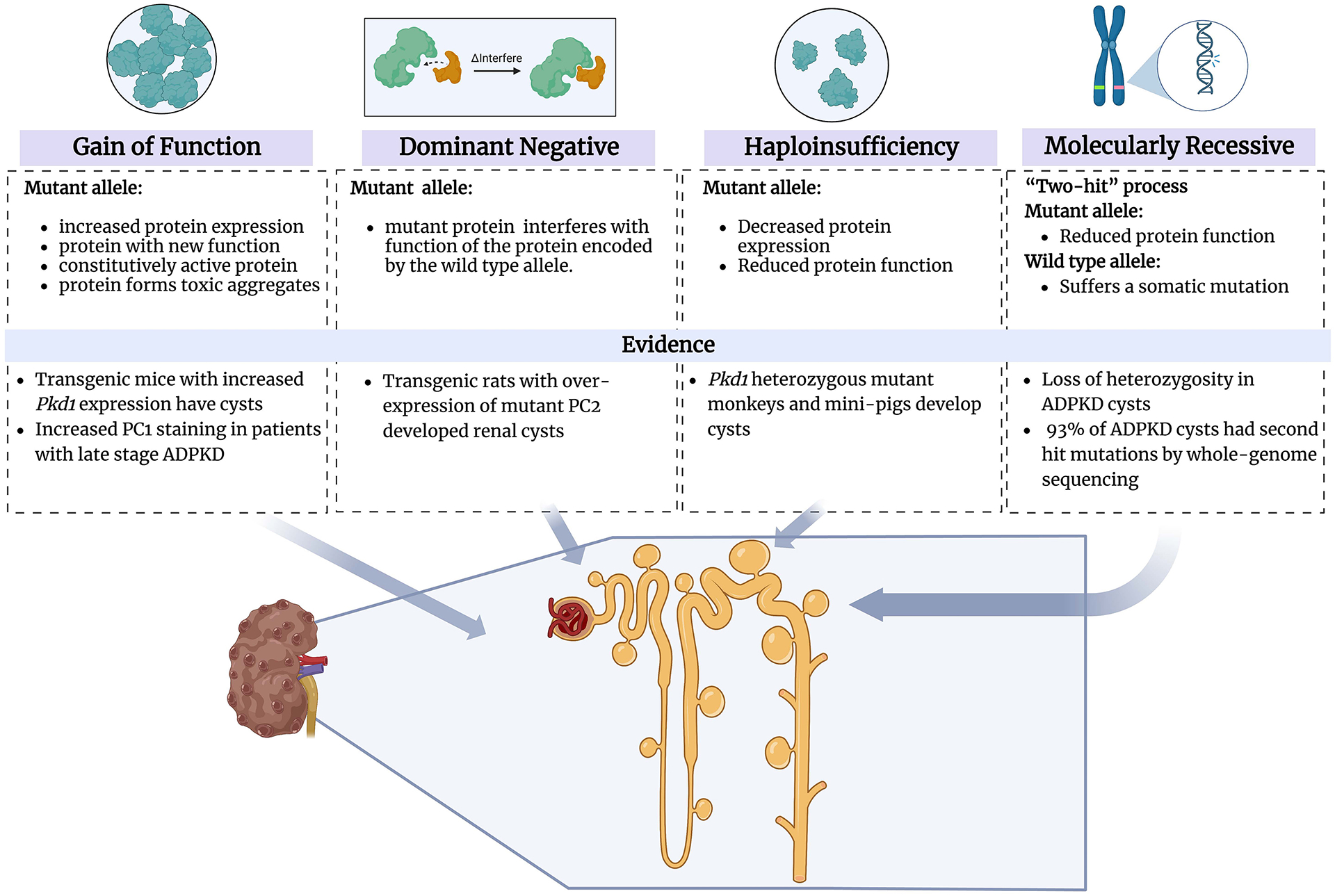

As the name implies, ADPKD is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner so one must explain how a germline mutation in only one copy of PKD1 or PKD2 is sufficient to trigger cyst initiation. Likewise, it is important to understand why cysts form in only a small fraction of tubules even though every cell in ADPKD patients shares the same germline mutation. Classical genetic theory describes four different ways this can occur25. Distinguishing between them is important for guiding therapeutic strategies:

Gain of function (GOF): The mutation results in expression of either too much protein, or a mutant protein that has a gain in function that makes it constitutively active, shifts its substrate or binding target specificity, or that forms toxic protein aggregates. The therapeutic strategy for GOF mutations is to reduce the gene’s activity.

Dominant negative (DN): The mutation results in a protein that can interfere with the function of the protein encoded by the normal allele. Genes that encode proteins which form homomeric structures may cause disease in this manner. In DN conditions, therapy is directed at blocking activity of the mutant gene by either suppressing its expression or inhibiting the activity of the mutant protein.

Haploinsufficiency (HI): The mutant gene is unable to produce any protein at all (a “null mutation”) or it encodes a protein with greatly reduced function (a “hypomorph”). In this setting, the total level of activity produced by the normal and mutant alleles is insufficient. Mutations in transcription factors often cause disease by such a mechanism. Therapeutic strategies for HI are focused on gene replacement or boosting activity of the normal copy.

Molecular recessive: Like in the haploinsufficient model, the inherited mutant gene either lacks or has greatly reduced function but the normal copy of the gene has sufficient function to maintain health. Disease usually results when a cell acquires a mutation in the previously normal allele. This “two-hit” process is a common cause of disease in hereditary cancer syndromes. Treatment strategies are directed at replacing the mutant gene’s activity.

In ADPKD, there is evidence that more than one of these mechanisms may contribute to cystogenesis (Figure 2). Some studies in cystic kidneys of ADPKD patients reported increased PC1 staining, suggesting a GOF mechanism26. To test this, mouse models expressing 2 to 15 times the normal amount of PC1 were made. In these mice, cystic tubules, often with hyperplastic lesions, were observed, with severity correlated with the increase in PC127. These studies suggested that a GOF mechanism can produce a cystic phenotype. Examples of dominant negative mutations in ADPKD are harder to prove. In one animal model, overexpression of truncated PC2 resulted in kidney cysts, and one possible explanation is that this mutant protein interfered with PC2 channel activity28.

Figure 2.

The mechanisms which contribute to cystogenesis in ADPKD:

a) Gain of function (GOF): The mutation results in the expression of either too much protein or a mutant protein that has a gain in the function that makes it constitutively active, shifts its substrate or binding target specificity, or that forms toxic protein aggregates. b) Dominant negative (DN): The mutation results in a protein that can interfere with the function of the protein encoded by the normal allele. Genes that encode proteins that form homomeric structures may cause disease in this manner. c) Haploinsufficiency (HI): The mutant gene is unable to produce any protein at all, or it encodes a protein with significantly reduced function. In this setting, the total activity level produced by the regular and mutant alleles is insufficient. d) Molecular recessive: Like in the haploinsufficient model, the inherited mutant gene either lacks or has dramatically reduced function but the usual copy of the gene has a sufficient function to maintain health. The disease usually results when a cell acquires a mutation in the previously normal allele. Created with BioRender.com.

The consequences of haploinsufficiency are still unresolved. In a few models, such as cynomolgus monkeys29 and mini-pigs30, infrequent cysts have been described in Pkd1 heterozygous mutants. While it seems unlikely that the heterozygous state significantly contributes to disease, it has been argued that presence of one germline mutant allele has functional consequences that might predispose to disease, one example being increased proliferation rates reported in mice heterozygous for a Pkd2 mutation31. The overwhelming majority of the data, however, points to a “two-hit” process affecting PKD1 or PKD2 as the underlying mechanism initiating kidney and liver cysts in most cases. Molecular analyses of individual cysts have shown them to be clonal with acquired mutations that disrupt the function of the previously normal allele32–34. These results have recently been replicated in whole genome/exome sequencing in cysts of ADPKD patients with PKD1 and PKD2 mutations, where a second-hit was detected in up to 93% of the cysts35, 36.

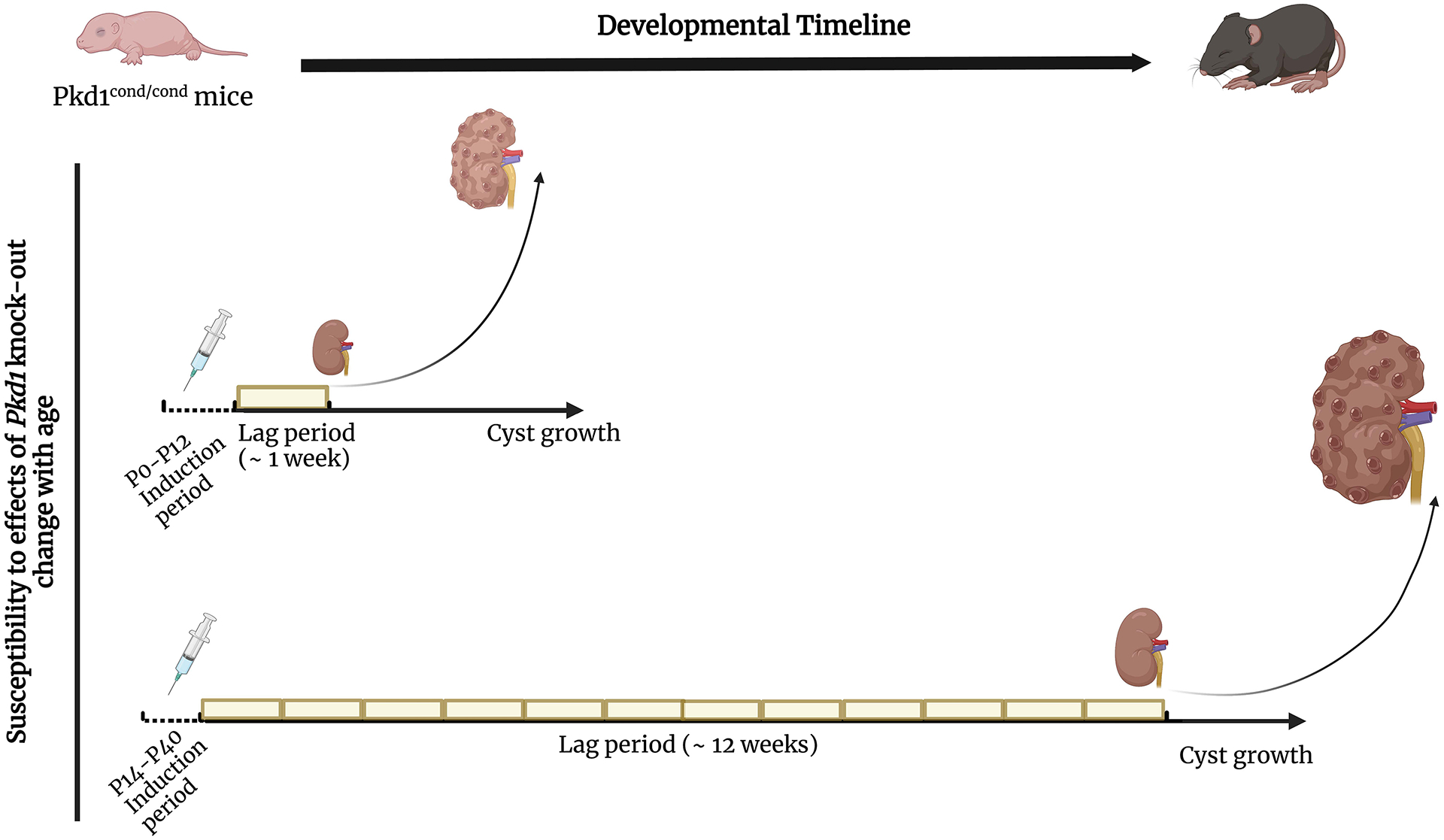

Studies done in Pkd1 and Pkd2 mouse models also strongly support the two-hit model. Mice with heterozygous germline null mutations in either Pkd1 or Pkd2 are healthy and develop few if any cysts as they age while homozygous mutants die in utero or perinatally with diffuse renal cystic disease37–39. This phenomenon likely explains why homozygosity for null mutations is not observed in humans. Using mice engineered so that acquired inactivation of Pkd1 or Pkd2 can be spatially and/or temporally regulated, it has been shown that cysts can form from all nephron segments and at all stages of life, and cysts that arise in very young mice grow faster than those that arise later40, 41 (Figure 3). These studies also have shown that the severity of cystic disease is determined by the rate of somatic inactivation42. This means that PKD1 and PKD2 likely remain susceptible targets for acquired inactivation over the course of an individual’s lifetime, with each “second hit” potentially initiating a new cyst to form. Pkd1 or Pkd2 mutant mice, with a much smaller number of cells and much shorter lifespan, have a much lower risk of acquiring a “second hit” and thus far less likely to develop more than a few cysts as they age.

Figure 3.

The figure represents the different susceptibility to Pkd1 loss in mice in which Pkd1 is inactivated before P12 (upper graph) or after P14 (lower graph). In mice induced before P12, cysts start to grow within ~1 week of gene inactivation. In the lower panel, mice induced at P14 or after have a lag time of several weeks (~12 weeks) before cysts start to form. Created with BioRender.com.

The Threshold Model

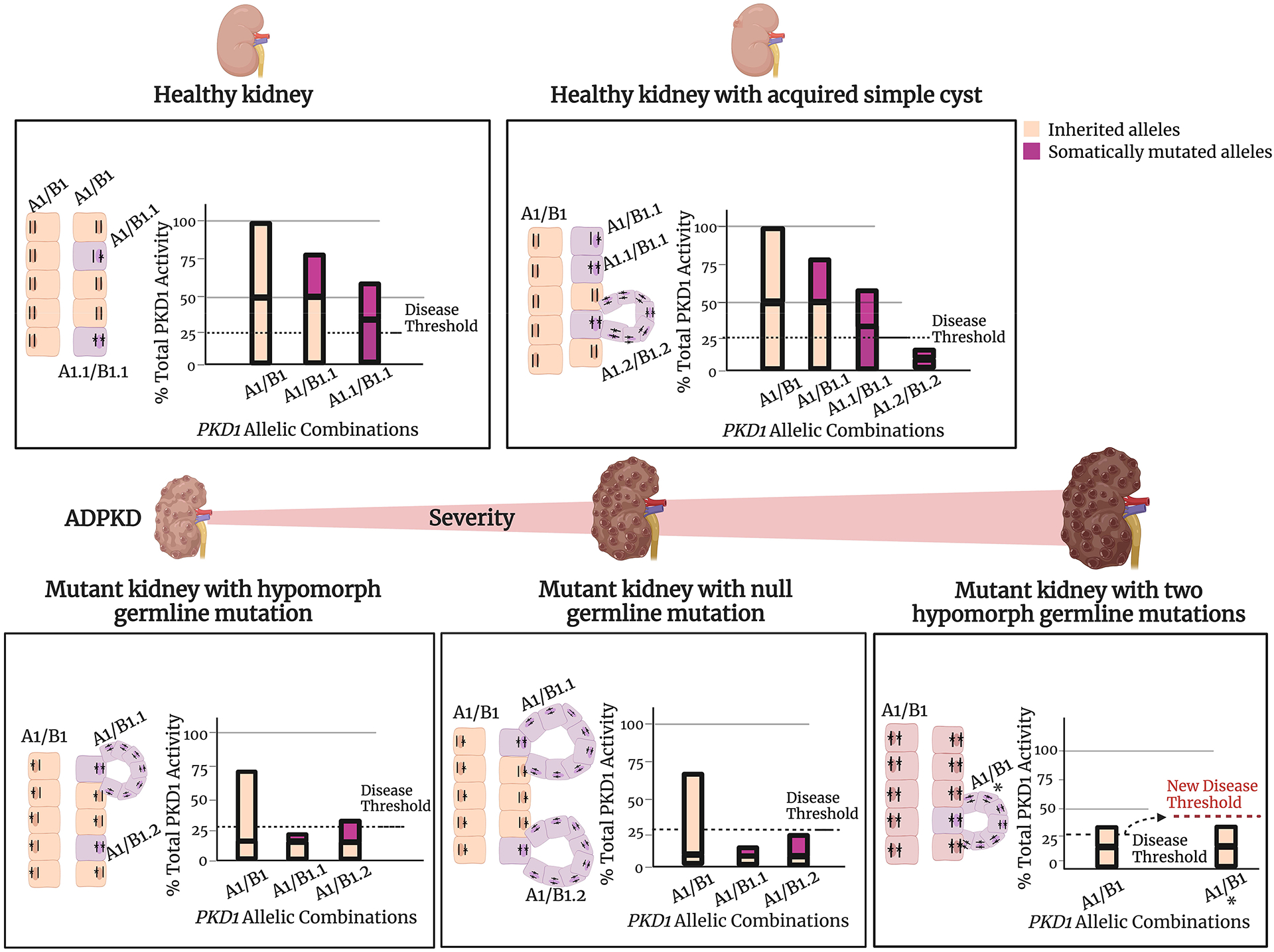

The “two-hit” model indicates that cyst initiation results from loss of PKD1 or PKD2 function. Studies of rare families with unusual presentations suggest that acquired mutations may not be necessary in all cases, leading some to suggest that a “threshold model” of activity better explains the mechanism of disease. These families have missense changes that alter the function of both copies of PKD1. Homozygotes present with diffuse disease while heterozygotes have few cysts43. Modeling this in mice, investigators showed that heterozygous mice were normal while homozygotes developed slowly progressive disease affecting only some tubules44. They also showed that missense changes affected PC1 processing within the cell, with the majority of PC1 failing to traffic properly44.

Another particularly dramatic example of a cell-dependent threshold for PC1 function is provided by a Pkd1 mouse mutant engineered to have a missense mutation that disrupts the GPS site45. The mutant protein is produced but fails to cleave and traffic to primary cilia. Homozygous mutants lack many of the vascular phenotypes seen in Pkd1 null mutants and are born with minimal cystic disease, indicating that the mutant protein retained sufficient activity to suppress some disease manifestations. However, the mutant mice subsequently develop progressively severe cystic disease exclusively in distal tubule segments. This result suggests that some mutations may have nephron-specific effects. Collectively, these data suggest that there is a threshold of activity required to maintain tubule integrity, and that the threshold may differ between cell populations based on cell type, age, and local cellular demands.

Looking at the data in toto, the “two-hit” and “threshold” models are in fact completely concordant. The overarching conclusion is that ADPKD results from a decrease in PKD gene activity below some threshold which is otherwise necessary to suppress cyst growth. In most cases of severe disease, this likely is the result of a “two-hit” genetic process, but presumably any process that compromises PKD1 and PKD2 activity or alters the threshold could trigger cyst formation. This model has important therapeutic implications because it suggests that strategies directed at replacing or enhancing PKD gene function could significantly lessen disease severity or even be curative.

One intervention currently being tested (NCT04536688) theoretically could work through this mechanism. A recent study found that both PKD1 and PKD2 contain binding motifs to a microRNA (miR-17) and that miR-17 binding to these motifs induces the degradation of the transcript and reduced the PC1/PC2 levels46. Investigators found that deleting these motifs in Pkd1 or Pkd2 or using an oligonucleotide inhibitor of miR-17 resulted in increased PC1 and PC2 protein expression and reduced severity of cystic disease46. It is unlikely, however, that this process contributes to cyst initiation because miR-17 activity is upregulated by c-Myc, whose activity increase parallels cyst growth47, 48. In fact, miR-17 expression is not increased in non-cystic tubules regardless of whether they have heterozygous or homozygous Pkd1 mutations48. It also should be noted that miR-17 has multiple non-PKD gene targets so any benefits of its inhibition may be due through other targets, as will be further discussed in a later section of this report.

Explaining Clinical Variability

With this model in hand, one can now readily explain much of the observed clinical variability. PKD1-associated disease is 5–6X more common than that associated with PKD2 because the coding sequence of PKD1 is much larger than that of PKD2. The PKD1 gene sequence also has several properties that make it more mutable; it is highly GC-rich; approximately 70% of its sequence is duplicated six times on chromosome 16p within six pseudogenes (PKD1P1 to PKD1P6), which share a 97.7% sequence identity with the genuine gene and thus serve as a reservoir for potential mutations by gene conversion49, 50; and it is bisected by two lengthy polypyrimidine tracts that can enhance the local mutation rate. These features may also explain why most families have unique or very rarely recurrent mutations despite the high incidence of the disease.

This model also likely explains why the number of cysts increases in most ADPKD individuals over time, and why disease associated with PKD1 mutations is generally more severe than with PKD2. PKD1’s high mutability makes it more likely to acquire somatic mutations at a higher rate than in PKD2-linked disease. We can also use this model to explain how the type of germline mutation can determine disease severity. On a population level, individuals with completely inactivating germline mutations of PKD1 have the most severe disease while those with PKD2 mutations have the least severe, and the group with missense PKD1 mutations fall in between with an intermediate phenotype51.

Figure 4 illustrates the process. Individuals with germline truncating or null mutations of PKD1 have the most severe disease because the haploinsufficient state is just above the threshold. It is therefore much more sensitive to any mutation that compromises the full function of the other PKD1 copy. Missense germline mutations, however, often produce proteins with some residual function. Under this scenario, the effect of the second hit on the previously normal allele must be sufficiently great to breach the threshold. A smaller number of acquired mutations will have this effect. The model also can explain those rare families with missense mutations that affect both copies of PKD1 or PKD2. Assuming the mutations are sufficiently functional to avoid pre-natal lethality, the total functional level of the two alleles might hover near the threshold, and depending on circumstances (age, cell type, other intracellular signaling pathways including acquired mutations in other “cystogenes”), cysts will form when total activity is below the threshold. Finally, the model also can explain simple, acquired cysts, which are present in most people and increase in number as they age. Given the intrinsic mutability of PKD1, it is likely that most individuals acquire PKD1 mutations as they age, but a mutation that disrupts a single copy is usually not sufficient to initiate a cyst. However, given the number of cells in the kidney, it is reasonably likely a rare cell will acquire two hits, and this then initiates cyst formation.

Figure 4.

Threshold model of cyst formation. This model is based on the hypothesis that a critical level of PKD1 and PKD2 functional activity is required to form and maintain tubule structure. In this model, a cyst forms when the combined activity of 2 alleles falls below the specific threshold for an individual cell. The requisite threshold may vary based on a combination of factors such as genetic variants at modifier loci, environmental effects, the developmental stage of the kidney, or physiologic demands. The actual level of activity achieved is determined by the specific combination of allelic variants in PKD1 or PKD2. The bars represent the functional activity of the protein encoded by the alleles. Inherited alleles are colored orange and somatically mutated alleles are purple. Inherited PKD1 alleles are identified as either “A” or “B” and alleles that have acquired a somatic mutation are indicated as “A.1” (B.1, etc). The height of the bar represents corresponding protein function. A wild type allele contributes 50% of the normal total PKD protein function in this model; hypomorph alleles have smaller percent contribution and a severe (truncating, etc) mutation that abolishes function contributes 0%. The dotted line represents the required function of PC1/PC2; if the activity falls below this threshold, cysts form. This figure illustrates the principle for PKD1 but the same likely applies for PKD2. Created with BioRender.com.

What happens after the cystic threshold is breached?

When PC1/PC2 function drops below threshold in an epithelial cell along the nephron, the mutant cell will eventually start proliferating. This clonal expansion, instead of forming a solid ball of cells, will start as an outpouch from the tubule, lined by a single layer of mutant cells, that will in time detach to form a cyst. Expansion of the cyst is thought to be due to two main factors: cell proliferation of the epithelial cells that line it and fluid secretion into its lumen. What happens between gene inactivation/mutation and cyst formation is still not completely understood. A set of studies in a Pkd1 mouse model showed that homozygous inactivation of Pkd1 in mice 12 days of age (P12) and younger resulted in rapid cyst formation, with large, cystic kidneys detected within days. If inactivation occurred in mice only 2 days older (P14 or older), the kidney would appear normal for months, but eventually grow into a massively cystic organ40 (Figure 3). This finding was puzzling. The kidneys of P12 and P14 mice are still growing with comparable cell proliferation rates so there is no apparent reason for an abrupt change in the kinetics of cyst formation during that time interval. If a change in proliferation rates was the principal explanation for the abrupt change, one would have expected the switch at P16 or later after proliferation rates had dropped. The data suggest that something else is influencing how cells respond to the lack of PC1.

Three somewhat interdependent models could explain this phenomenon: a) PC1 is a stable protein and there is a lag time between deletion of the gene and functional effects of lack of PC1; b) PC1’s functional requirements and/or threshold change during kidney development/growth/maturation; c) the response to lack of PC1 can be modified by the cell’s physiological state. While PC1 is notoriously difficult to visualize and detect, its levels in mice fall sharply between days 1 and 10, becoming barely detectable at the older age6. These observations suggest that high stability and high levels of PC1 are unlikely to explain the phenotypic differences of mice inactivated before or after P13. The same fact, however, is consistent with PC1 being “more necessary” at early stages of kidney development. This would imply that the physiological state of cells in P12 and P14 animals are different and that the consequences of loss of PC1/PC2 activity depend on that state.

This model could potentially explain other findings. Some investigators have suggested that PKD is in fact a “three-hit” disease52–54. The long lag time between acquired loss of Pkd1 and the onset of cysts in adult mice is consistent with such a model, and it has been reported that this process can be hastened by adding a putative “third hit” through renal injury. Using an inducible model of Pkd1 loss, they showed that mice with unilateral renal injury developed severe cystic disease within weeks while the contralateral kidney did not53. It should be noted, however, that the model used a Cre recombinase that was activated by interferon, which goes up after injury. This is an important confounder since renal injury may have enhanced Cre activity in the injured organ, resulting in much higher levels of Pkd1 inactivation. This observation may also explain why bilateral injury in the same model resulted in bilateral cystic disease whereas injury of a heterozygous Pkd1 mouse kidney did not. Despite the complexity posed by use of the interferon-inducible Cre recombinase, however, cysts are detectable in this model faster than otherwise expected suggesting that changes in the physiologic state of a cell might enhance or slow the rate of cyst formation when PC1 activity is severely reduced or compromised.

Taken together, the data suggest that the physiologic status of a cell likely determines its response to loss of PC1 or PC2. Understanding the pathways that determine the susceptibility to loss of PC1/PC2 function could be harnessed to slow disease progression.

Is PKD a metabolic disease?

A series of studies over the last decade focused on elucidating some of these pathways. Initial transcriptomic analyses of Pkd1 conditional mice in which Pkd1 was inactivated either before or after P12 gave an initial clue to what might be happening55. In control mice, the window between P12 and P14 is characterized by transcriptional changes that are enriched in metabolic pathways. Studying the same window in mutant mice, it was apparent that mutant kidneys undergo similar transcriptional changes, suggesting that lack of PC1 was not preventing kidney maturation. This finding was in contrast to prior studies which had suggested that PKD kidneys had arrested development. The transcriptional studies instead implied that Pkd1 mutants had re-wiring of their metabolic pathways, leading to the suggestion that the metabolic status of cells could modulate disease progression. It also suggests that dysregulated cellular metabolism could be an early step in driving cellular proliferation and cyst formation.

Around the same time, studies in the Boletta group identified intrinsic metabolic changes in Pkd1 mutant cells56. According to these studies, mutant cells displayed evidence of Warburg phenomenon, shifting to a predominantly glycolytic profile. Other studies identified fatty acid oxidation impairment57 and global metabolic reprogramming58. These findings paved the way to a series of studies trying to elucidate how PC1 might be involved in metabolic functions. Surprisingly, these finding converged to paint a picture of PC1 having a direct role in mitochondrial function: a) mitochondria have functional (less oxidative phosphorylation) and morphological (more fragmented) changes in Pkd1 mutants14; b) a PC1 fragment (PC1-CTT) was detected in mitochondria10, 14; c) PC1 was detected in mitochondria-ER contact sites10; d) PC1 was found to interact with nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase (NNT), a mitochondrial protein that reduces NADP+ into NADPH6, 59; e) PC1-CTT was reported to rescue the cystic phenotype in mice expressing Nnt, but not in Nnt-mutant mice59.

Despite this progress, it is still unclear how cyst formation/growth are linked to cellular metabolism (reviewed in60). One possibility is that altered cellular metabolism, with its effects on cell energetics and biosynthetic pathways, is in fact a principal driver of cyst growth as occurs in cancer. Loss of Pkd1 or Pkd2 results in activation of c-Myc, a master regulator of cancer metabolism61, and one of its downstream targets is miR-1747, 48.The evidence that these pathways are relevant comes from studies showing that blocking glycolysis with the glucose analogue 2-DG, enhancing fatty acid oxidation using peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPAR-α) -agonists, and blocking miR-17 improved disease62, 63. An alternative view, which would also be consistent with the above evidence, is that the metabolic dysfunction may alter downstream signaling, perhaps through epigenetic mechanisms64, 65 and these pathways, rather than metabolic changes, drive disease.

Other pathways – why so many?

Regardless of whether metabolic changes turn out to be the major link between Pkd1 deletion and cystogenesis, it is clear that other pathways are involved (Figure 5). Some of those that have been implicated include AMP-activated kinase66, mTOR67, Hippo68, MAPK/ERK69, JAK-STAT39 Wnt15, cAMP70, Calcium71 and multiple growth factors (EGF72, TGF-beta73, IGF74) with many of the pathways interconnected. cAMP, in particular, had been long implicated in promoting cyst growth in both in vitro and in vivo models of cystic disease75, which led to the hypothesis that blocking sources of cAMP production in the kidney might slow down cyst progression. This was tested by inhibiting arginine vasopressin type 2 receptors (V2Rs), a major source of cAMP production in collecting ducts, in mouse models76 and, finally, clinical studies in ADPKD patients77, leading to tolvaptan being the only currently FDA-approved therapy for PKD.

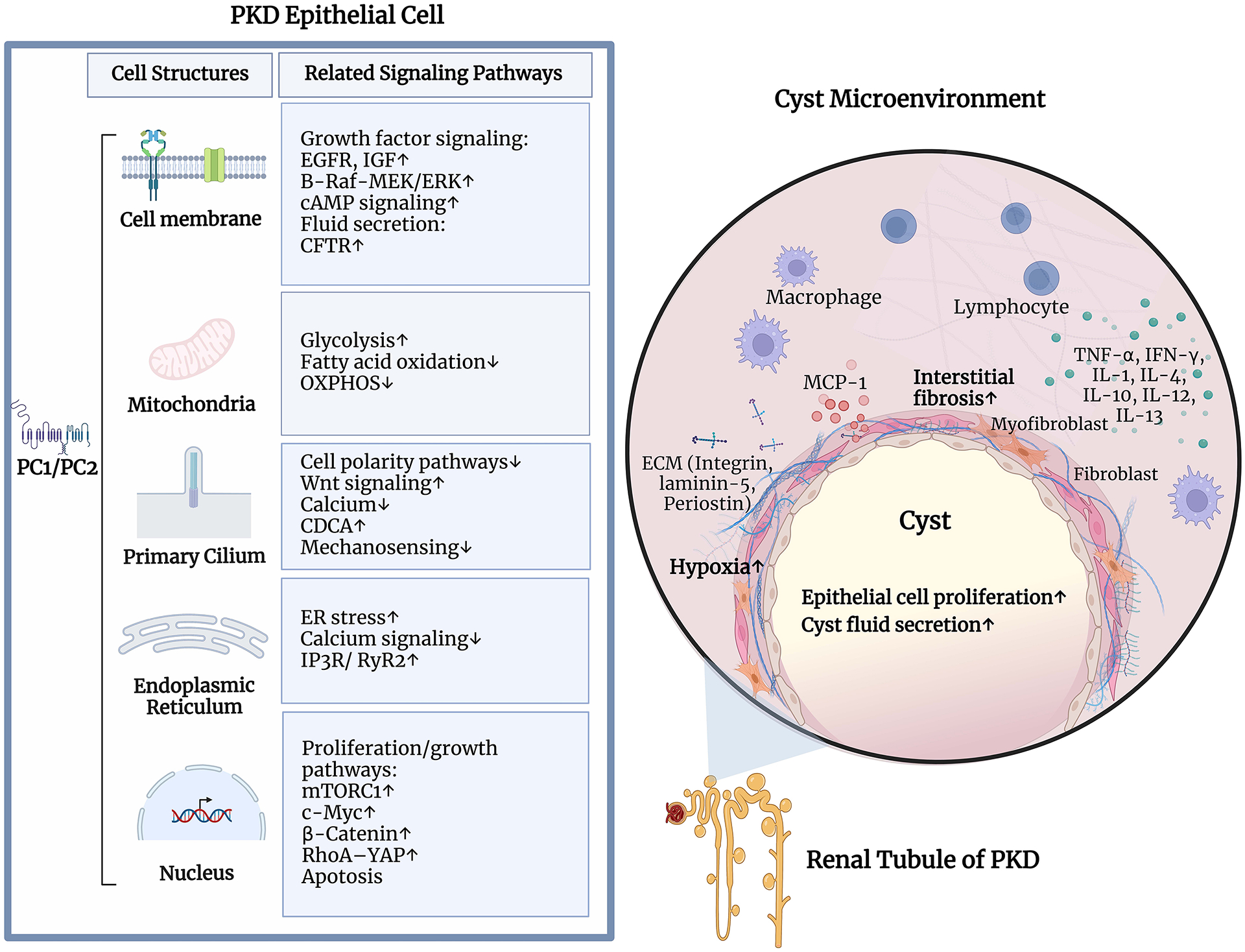

Figure 5.

Overview of the cystic pathways. The panel on the left shows some of the pathways reported to be altered in PKD and the main cellular location of the activity. The panel on the right shows the cyst microenvironment and some pathways reported to the immune response and disease progression. B-Raf, serine/threonine-protein kinase B-raf; cAMP, Cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate; CDCA, cilia-dependent cyst activation; CFTR, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; c-Myc, myc proto-oncogene protein; ECM: extracellular matrix; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; IGF, Insulin-like growth factor 1; IFN-γ, Interferon-γ; IP3R, IP3 receptor; MCP-1, Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; MEK, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase; mTORC1, mammalian target of rapamycin complex1; OXPHOS, oxidative phosphorylation; PC1: polycystin-1; PC2: polycystin-2; RyR2, ryanodine receptor 2; RhoA, ras homolog family member A; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor α; YAP, yes-Associated Protein. Created with BioRender.com.

Why would so many pathways be involved in PKD? Multiple explanations have been proposed. One interesting observation is that transcriptional studies suggest that at early stages after inactivation, before kidney morphology becomes visibly altered, only few genes are differentially expressed, in contrast to the multitude of differentially expressed genes and implicated pathways found at later stages55 57. There are different models for how this could happen. In one scenario, the PC1/PC2 complex itself modulates the activity of multiple pathways in subtle ways. These changes might be too small to confidently be distinguished from noise, but over a variable timespan they accumulate incrementally and inexorably, almost like aging, where day-to-day differences go unnoticed, but accumulate.

A second scenario is that PC1/PC2 control the activity of an important signaling hub. Tubules are 3-dimensional structures that require coordinated regulation of multiple complex pathways to maintain proper morphology and size. Given the likely function of PC1/PC2 as a receptor-channel complex18, it is possible that they serve as a sensor of tubule size/morphology and sit atop a signaling hub that controls coordination of these myriad downstream pathways. The role of the mitochondrion serving as an important signaling hub has been hinted at above and also recently reviewed60.

Another likely “hub organelle” is the primary cilium. As the name suggests, the cilium is a hair-like structure with a microtubular scaffold surrounded by cellular membrane and projecting extracellularly from the apical membrane78. Disruption of this organelle has been linked to a variety of signaling pathway abnormalities and results in multiple human diseases, collectively referred to as “ciliopathies”79. PC1 and PC2, among many other proteins involved in cystic kidney diseases, have been detected in the primary cilium, and modulating cilia function can cause or alter cyst formation and growth, suggesting that it is likely to be a major player in PKD pathogenesis80. A final possibility is that myriad pathways dysregulated in PKD could be secondary both to cell autonomous changes and to the ongoing changes of the neighboring tissue, such as fibrosis, cystic compression and ischemia.

Role of interactions with the tissue environment

Finally, another set of studies suggests that in addition to intrinsic properties of the mutant epithelial cells, the surrounding immune cells can significantly alter cystic disease progression81. In PKD, changes in the innate immune response could precede kidney injury82 and eventually result in a robust innate and adaptive immune responses83. Mitochondrial damage with release of mitochondrial DNA could be a potent activator of the innate immune response84. Studies also suggest that monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1), a proinflammatory chemokine, is a regulator of PKD-related interstitial inflammation and renal dysfunction85, and that accumulation of activated macrophages around cysts can increase their growth rate81. Consistent with this hypothesis, deletion of Ccl2, the MCP-1 encoding gene, in Pkd1 mutants reduced macrophage infiltration, tubular damage and cyst growth, resulting in improved renal function86.

Is PKD reversible?

As noted in an earlier section, studies comparing the transcriptional patterns of normal and Pkd1 mutant mice at P12 and P14 found that they followed a similar developmental program with the network structure of wild type and mutant kidneys similar55. These data suggested that the early stages of cyst formation might be reversible87. Recent studies in mice strongly support this perspective. Investigators engineered a mouse model where they could sequentially turn off and then turn back on Pkd1 expression in the kidney. They found that re-expression of Pkd1 could quickly reverse cystic disease, suggesting amazing plasticity in at least the early stages of disease88. Even well-advanced disease could be partially rescued, though with some residual fibrosis and decreased function. These results suggest that strategies aimed at boosting or replacing PC1/PC2 function might not only prevent new cyst formation, they might even reverse cyst growth, resulting in partial normalization of tubule function.

Conclusion

The evidence to date suggests that PKD is a complex disease, involving both cell autonomous pathways driving cyst initiation, and an interplay with the tissue metabolic and immune milieu that modulate cystic growth. Understanding the relative role of each in causing disease will allow more precise ways of preventing, delaying, or slowing PKD. It will be particularly important to determine if there is a principal signaling hub that controls the multitude of downstream pathways that are dysregulated in cystic cells, and if that hub can be safely modulated. The large number of downstream pathways theoretically offers numerous avenues to intercede, but it also suggests that few may be able to do more than modestly slow progression. Recent studies showing reversibility of cystic disease offers promise that strategies directed at boosting or replacing PC1/PC2 function could be curative, both by preventing cyst initiation and reversing early cystic change.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the NIH, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Intramural Research Program, grant 1ZIADK075042.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Israel GM, Bosniak MA. An update of the Bosniak renal cyst classification system. Urology. Sep 2005;66(3):484–8. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bisceglia M, Galliani CA, Senger C, Stallone C, Sessa A. Renal cystic diseases: a review. Adv Anat Pathol. Jan 2006;13(1):26–56. doi: 10.1097/01.pap.0000201831.77472.d3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grantham JJ. Clinical practice. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. Oct 2 2008;359(14):1477–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0804458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nims N, Vassmer D, Maser RL. Transmembrane domain analysis of polycystin-1, the product of the polycystic kidney disease-1 (PKD1) gene: evidence for 11 membrane-spanning domains. Biochemistry. Nov 11 2003;42(44):13035–48. doi: 10.1021/bi035074c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qian F, Boletta A, Bhunia AK, et al. Cleavage of polycystin-1 requires the receptor for egg jelly domain and is disrupted by human autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease 1-associated mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Dec 24 2002;99(26):16981–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252484899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin C-C, Menezes LF, Pearson E, et al. Use of a novel knock-in allele of Pkd1 identifies nicotinamide nucleotide dehydrogenase as a mitochondrial binding partner of polycystin-1. bioRxiv. 2022:2022.04.08.487705. doi: 10.1101/2022.04.08.487705 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Streets AJ, Wagner BE, Harris PC, Ward CJ, Ong AC. Homophilic and heterophilic polycystin 1 interactions regulate E-cadherin recruitment and junction assembly in MDCK cells. J Cell Sci. May 1 2009;122(Pt 9):1410–7. doi: 10.1242/jcs.045021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya O, Dackowski WR, Foggensteiner L, et al. Polycystin: in vitro synthesis, in vivo tissue expression, and subcellular localization identifies a large membrane-associated protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Jun 10 1997;94(12):6397–402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoder BK, Hou X, Guay-Woodford LM. The polycystic kidney disease proteins, polycystin-1, polycystin-2, polaris, and cystin, are co-localized in renal cilia. J Am Soc Nephrol. Oct 2002;13(10):2508–16. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000029587.47950.25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Padovano V, Kuo IY, Stavola LK, et al. The polycystins are modulated by cellular oxygen-sensing pathways and regulate mitochondrial function. Mol Biol Cell. Jan 15 2017;28(2):261–269. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E16-08-0597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim H, Xu H, Yao Q, et al. Ciliary membrane proteins traffic through the Golgi via a Rabep1/GGA1/Arl3-dependent mechanism. Nat Commun. Nov 18 2014;5:5482. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chauvet V, Tian X, Husson H, et al. Mechanical stimuli induce cleavage and nuclear translocation of the polycystin-1 C terminus. J Clin Invest. Nov 2004;114(10):1433–43. doi: 10.1172/JCI21753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Low SH, Vasanth S, Larson CH, et al. Polycystin-1, STAT6, and P100 function in a pathway that transduces ciliary mechanosensation and is activated in polycystic kidney disease. Dev Cell. Jan 2006;10(1):57–69. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin CC, Kurashige M, Liu Y, et al. A cleavage product of Polycystin-1 is a mitochondrial matrix protein that affects mitochondria morphology and function when heterologously expressed. Sci Rep. Feb 9 2018;8(1):2743. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20856-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim S, Nie H, Nesin V, et al. The polycystin complex mediates Wnt/Ca(2+) signalling. Nat Cell Biol. Jul 2016;18(7):752–764. doi: 10.1038/ncb3363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parnell SC, Magenheimer BS, Maser RL, et al. The polycystic kidney disease-1 protein, polycystin-1, binds and activates heterotrimeric G-proteins in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. Oct 20 1998;251(2):625–31. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mochizuki T, Wu G, Hayashi T, et al. PKD2, a gene for polycystic kidney disease that encodes an integral membrane protein. Science. May 31 1996;272(5266):1339–42. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5266.1339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Esarte Palomero O, Larmore M, DeCaen PG. Polycystin Channel Complexes. Annu Rev Physiol. Feb 10 2023;85:425–448. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-031522-084334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu X, Vien T, Duan J, Sheu SH, DeCaen PG, Clapham DE. Polycystin-2 is an essential ion channel subunit in the primary cilium of the renal collecting duct epithelium. Elife. Feb 14 2018;7doi: 10.7554/eLife.33183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanaoka K, Qian F, Boletta A, et al. Co-assembly of polycystin-1 and -2 produces unique cation-permeable currents. Nature. Dec 21–28 2000;408(6815):990–4. doi: 10.1038/35050128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen PS, Yang X, DeCaen PG, et al. The Structure of the Polycystic Kidney Disease Channel PKD2 in Lipid Nanodiscs. Cell. Oct 20 2016;167(3):763–773 e11. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Su Q, Hu F, Ge X, et al. Structure of the human PKD1-PKD2 complex. Science. Sep 7 2018;361(6406)doi: 10.1126/science.aat9819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foggensteiner L, Bevan AP, Thomas R, et al. Cellular and subcellular distribution of polycystin-2, the protein product of the PKD2 gene. J Am Soc Nephrol. May 2000;11(5):814–827. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V115814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newby LJ, Streets AJ, Zhao Y, Harris PC, Ward CJ, Ong AC. Identification, characterization, and localization of a novel kidney polycystin-1-polycystin-2 complex. J Biol Chem. Jun 7 2002;277(23):20763–73. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107788200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Veitia RA, Caburet S, Birchler JA. Mechanisms of Mendelian dominance. Clin Genet. Mar 2018;93(3):419–428. doi: 10.1111/cge.13107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ward CJ, Turley H, Ong AC, et al. Polycystin, the polycystic kidney disease 1 protein, is expressed by epithelial cells in fetal, adult, and polycystic kidney. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Feb 20 1996;93(4):1524–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurbegovic A, Cote O, Couillard M, Ward CJ, Harris PC, Trudel M. Pkd1 transgenic mice: adult model of polycystic kidney disease with extrarenal and renal phenotypes. Hum Mol Genet. Apr 1 2010;19(7):1174–89. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gallagher AR, Hoffmann S, Brown N, et al. A truncated polycystin-2 protein causes polycystic kidney disease and retinal degeneration in transgenic rats. J Am Soc Nephrol. Oct 2006;17(10):2719–30. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005090979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsukiyama T, Kobayashi K, Nakaya M, et al. Monkeys mutant for PKD1 recapitulate human autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nat Commun. Dec 11 2019;10(1):5517. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13398-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.He J, Li Q, Fang S, et al. PKD1 mono-allelic knockout is sufficient to trigger renal cystogenesis in a mini-pig model. Int J Biol Sci. 2015;11(4):361–9. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.10858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chang MY, Parker E, Ibrahim S, et al. Haploinsufficiency of Pkd2 is associated with increased tubular cell proliferation and interstitial fibrosis in two murine Pkd2 models. Nephrol Dial Transplant. Aug 2006;21(8):2078–84. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qian F, Watnick TJ, Onuchic LF, Germino GG. The molecular basis of focal cyst formation in human autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease type I. Cell. Dec 13 1996;87(6):979–87. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81793-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watnick TJ, Torres VE, Gandolph MA, et al. Somatic mutation in individual liver cysts supports a two-hit model of cystogenesis in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Mol Cell. Aug 1998;2(2):247–51. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80135-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koptides M, Hadjimichael C, Koupepidou P, Pierides A, Constantinou Deltas C. Germinal and somatic mutations in the PKD2 gene of renal cysts in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Hum Mol Genet. Mar 1999;8(3):509–13. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.3.509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Z, Bai H, Blumenfeld J, et al. Detection of PKD1 and PKD2 Somatic Variants in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Cyst Epithelial Cells by Whole-Genome Sequencing. J Am Soc Nephrol. Dec 1 2021;32(12):3114–3129. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2021050690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan AY, Zhang T, Michaeel A, et al. Somatic Mutations in Renal Cyst Epithelium in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. Aug 2018;29(8):2139–2156. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2017080878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu G, Markowitz GS, Li L, et al. Cardiac defects and renal failure in mice with targeted mutations in Pkd2. Nat Genet. Jan 2000;24(1):75–8. doi: 10.1038/71724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu W, Shen X, Pavlova A, et al. Comparison of Pkd1-targeted mutants reveals that loss of polycystin-1 causes cystogenesis and bone defects. Hum Mol Genet. Oct 1 2001;10(21):2385–96. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.21.2385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhunia AK, Piontek K, Boletta A, et al. PKD1 induces p21(waf1) and regulation of the cell cycle via direct activation of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway in a process requiring PKD2. Cell. Apr 19 2002;109(2):157–68. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00716-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Piontek K, Menezes LF, Garcia-Gonzalez MA, Huso DL, Germino GG. A critical developmental switch defines the kinetics of kidney cyst formation after loss of Pkd1. Nat Med. Dec 2007;13(12):1490–5. doi: 10.1038/nm1675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Piontek KB, Huso DL, Grinberg A, et al. A functional floxed allele of Pkd1 that can be conditionally inactivated in vivo. J Am Soc Nephrol. Dec 2004;15(12):3035–43. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000144204.01352.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu G, D’Agati V, Cai Y, et al. Somatic inactivation of Pkd2 results in polycystic kidney disease. Cell. Apr 17 1998;93(2):177–88. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81570-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rossetti S, Kubly VJ, Consugar MB, et al. Incompletely penetrant PKD1 alleles suggest a role for gene dosage in cyst initiation in polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. Apr 2009;75(8):848–55. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hopp K, Ward CJ, Hommerding CJ, et al. Functional polycystin-1 dosage governs autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease severity. J Clin Invest. Nov 2012;122(11):4257–73. doi: 10.1172/JCI64313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu S, Hackmann K, Gao J, et al. Essential role of cleavage of Polycystin-1 at G protein-coupled receptor proteolytic site for kidney tubular structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Nov 20 2007;104(47):18688–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708217104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lakhia R, Ramalingam H, Chang CM, et al. PKD1 and PKD2 mRNA cis-inhibition drives polycystic kidney disease progression. Nat Commun. Aug 15 2022;13(1):4765. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-32543-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parrot C, Kurbegovic A, Yao G, Couillard M, Cote O, Trudel M. c-Myc is a regulator of the PKD1 gene and PC1-induced pathogenesis. Hum Mol Genet. Mar 1 2019;28(5):751–763. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hajarnis S, Lakhia R, Yheskel M, et al. microRNA-17 family promotes polycystic kidney disease progression through modulation of mitochondrial metabolism. Nat Commun. Feb 16 2017;8:14395. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bogdanova N, Markoff A, Gerke V, McCluskey M, Horst J, Dworniczak B. Homologues to the first gene for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease are pseudogenes. Genomics. Jun 15 2001;74(3):333–41. doi: 10.1006/geno.2001.6568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rossetti S, Hopp K, Sikkink RA, et al. Identification of gene mutations in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease through targeted resequencing. J Am Soc Nephrol. May 2012;23(5):915–33. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011101032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cornec-Le Gall E, Torres VE, Harris PC. Genetic Complexity of Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney and Liver Diseases. J Am Soc Nephrol. Jan 2018;29(1):13–23. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2017050483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weimbs T Third-hit signaling in renal cyst formation. J Am Soc Nephrol. May 2011;22(5):793–5. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011030284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takakura A, Contrino L, Zhou X, et al. Renal injury is a third hit promoting rapid development of adult polycystic kidney disease. Hum Mol Genet. Jul 15 2009;18(14):2523–31. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Torres JA, Rezaei M, Broderick C, et al. Crystal deposition triggers tubule dilation that accelerates cystogenesis in polycystic kidney disease. J Clin Invest. Jul 30 2019;129(10):4506–4522. doi: 10.1172/JCI128503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Menezes LF, Zhou F, Patterson AD, et al. Network analysis of a Pkd1-mouse model of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease identifies HNF4alpha as a disease modifier. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(11):e1003053. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rowe I, Chiaravalli M, Mannella V, et al. Defective glucose metabolism in polycystic kidney disease identifies a new therapeutic strategy. Nat Med. Apr 2013;19(4):488–93. doi: 10.1038/nm.3092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Menezes LF, Lin CC, Zhou F, Germino GG. Fatty Acid Oxidation is Impaired in An Orthologous Mouse Model of Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. EBioMedicine. Mar 2016;5:183–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.01.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Podrini C, Rowe I, Pagliarini R, et al. Dissection of metabolic reprogramming in polycystic kidney disease reveals coordinated rewiring of bioenergetic pathways. Commun Biol. 2018;1:194. doi: 10.1038/s42003-018-0200-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Onuchic L, Padovano V, Schena G, et al. The C-terminal tail of polycystin-1 suppresses cystic disease in a mitochondrial enzyme-dependent fashion. bioRxiv. 2021:2021.12.21.473680. doi: 10.1101/2021.12.21.473680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Menezes LF, Germino GG. The pathobiology of polycystic kidney disease from a metabolic viewpoint. Nat Rev Nephrol. Dec 2019;15(12):735–749. doi: 10.1038/s41581-019-0183-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miller DM, Thomas SD, Islam A, Muench D, Sedoris K. c-Myc and cancer metabolism. Clin Cancer Res. Oct 15 2012;18(20):5546–53. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chiaravalli M, Rowe I, Mannella V, et al. 2-Deoxy-d-Glucose Ameliorates PKD Progression. J Am Soc Nephrol. Jul 2016;27(7):1958–69. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015030231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lakhia R, Yheskel M, Flaten A, Quittner-Strom EB, Holland WL, Patel V. PPARalpha agonist fenofibrate enhances fatty acid beta-oxidation and attenuates polycystic kidney and liver disease in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. Jan 1 2018;314(1):F122–F131. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00352.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bowden SA, Rodger EJ, Chatterjee A, Eccles MR, Stayner C. Recent Discoveries in Epigenetic Modifications of Polycystic Kidney Disease. Int J Mol Sci. Dec 11 2021;22(24)doi: 10.3390/ijms222413327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lakhia R, Mishra A, Biggers L, et al. Enhancer and super-enhancer landscape in polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. Jan 2023;103(1):87–99. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2022.08.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Takiar V, Nishio S, Seo-Mayer P, et al. Activating AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) slows renal cystogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Feb 8 2011;108(6):2462–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011498108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shillingford JM, Murcia NS, Larson CH, et al. The mTOR pathway is regulated by polycystin-1, and its inhibition reverses renal cystogenesis in polycystic kidney disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Apr 4 2006;103(14):5466–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509694103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cai J, Song X, Wang W, et al. A RhoA-YAP-c-Myc signaling axis promotes the development of polycystic kidney disease. Genes Dev. Jun 1 2018;32(11–12):781–793. doi: 10.1101/gad.315127.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sweeney WE Jr., von Vigier RO, Frost P, Avner ED. Src inhibition ameliorates polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. Jul 2008;19(7):1331–41. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007060665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yamaguchi T, Nagao S, Kasahara M, Takahashi H, Grantham JJ. Renal accumulation and excretion of cyclic adenosine monophosphate in a murine model of slowly progressive polycystic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. Nov 1997;30(5):703–9. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90496-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yamaguchi T, Wallace DP, Magenheimer BS, Hempson SJ, Grantham JJ, Calvet JP. Calcium restriction allows cAMP activation of the B-Raf/ERK pathway, switching cells to a cAMP-dependent growth-stimulated phenotype. J Biol Chem. Sep 24 2004;279(39):40419–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405079200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sweeney WE, Frost P, Avner ED. Tesevatinib ameliorates progression of polycystic kidney disease in rodent models of autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. World J Nephrol. Jul 6 2017;6(4):188–200. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v6.i4.188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Leonhard WN, Kunnen SJ, Plugge AJ, et al. Inhibition of Activin Signaling Slows Progression of Polycystic Kidney Disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. Dec 2016;27(12):3589–3599. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015030287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kashyap S, Hein KZ, Chini CC, et al. Metalloproteinase PAPP-A regulation of IGF-1 contributes to polycystic kidney disease pathogenesis. JCI Insight. Feb 27 2020;5(4)doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.135700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Scholz JK, Kraus A, Luder D, et al. Loss of Polycystin-1 causes cAMP-dependent switch from tubule to cyst formation. iScience. Jun 17 2022;25(6):104359. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2022.104359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Torres VE, Wang X, Qian Q, Somlo S, Harris PC, Gattone VH 2nd. Effective treatment of an orthologous model of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nat Med. Apr 2004;10(4):363–4. doi: 10.1038/nm1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Torres VE, Chapman AB, Devuyst O, et al. Tolvaptan in Later-Stage Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. N Engl J Med. Nov 16 2017;377(20):1930–1942. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1710030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gerdes JM, Davis EE, Katsanis N. The vertebrate primary cilium in development, homeostasis, and disease. Cell. Apr 3 2009;137(1):32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hildebrandt F, Benzing T, Katsanis N. Ciliopathies. N Engl J Med. Apr 21 2011;364(16):1533–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1010172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ma M, Gallagher AR, Somlo S. Ciliary Mechanisms of Cyst Formation in Polycystic Kidney Disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. Nov 1 2017;9(11)doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a028209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Karihaloo A, Koraishy F, Huen SC, et al. Macrophages promote cyst growth in polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. Oct 2011;22(10):1809–14. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011010084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mrug M, Zhou J, Woo Y, et al. Overexpression of innate immune response genes in a model of recessive polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. Jan 2008;73(1):63–76. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zimmerman KA, Hopp K, Mrug M. Role of chemokines, innate and adaptive immunity. Cell Signal. Sep 2020;73:109647. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2020.109647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Banoth B, Cassel SL. Mitochondria in innate immune signaling. Transl Res. Dec 2018;202:52–68. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2018.07.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cowley BD Jr., Ricardo SD, Nagao S, Diamond JR. Increased renal expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and osteopontin in ADPKD in rats. Kidney Int. Dec 2001;60(6):2087–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00065.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cassini MF, Kakade VR, Kurtz E, et al. Mcp1 Promotes Macrophage-Dependent Cyst Expansion in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. Oct 2018;29(10):2471–2481. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2018050518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Menezes LF, Germino GG. Systems biology of polycystic kidney disease: a critical review. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. Jan-Feb 2015;7(1):39–52. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.1289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dong K, Zhang C, Tian X, et al. Renal plasticity revealed through reversal of polycystic kidney disease in mice. Nat Genet. Dec 2021;53(12):1649–1663. doi: 10.1038/s41588-021-00946-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]