Abstract

The effect of nanoemulsions on the stability and bioavailability of sulforaphene (SFEN) in radish seed extract (RSE) was investigated. Four types of oil were used as lipid ingredients of the nanoemulsions: soybean, high oleic acid sunflower, coconut, and hydrogenated palm oils. SFEN in RSE nanoemulsions showed greater stability to temperature, acid, and alkaline conditions than SFEN in RSE suspended in water (RSE-S). Particularly under alkaline conditions, the half-life of SFEN in the nanoemulsion with high oleic sunflower oil (RSE-HOSO) was 8 times longer than that of RSE-S. Furthermore, in the pharmacokinetics study, it was observed that AUC0–8 increased and oral clearance (CL/F) decreased significantly in rats orally administered RSE-HOSO compared with RSE-S (p < 0.05). This study indicates that the type of oil used in nanoemulsions affects the stability and bioavailability of SFEN in RSE. These results may provide a guideline for the development of functional foods containing RSE.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10068-023-01304-2.

Keywords: Radish seeds, Nanoemulsion, Vegetable oils, Storage stability, Pharmacokinetics

Introduction

Isothiocyanates (ITCs) are sulfur-containing compounds found in various species of Brassicaceae family plants. ITCs commonly include a functional group as R-N = C = S. The representative isothiocyanates are allyl isothiocyanate, benzyl isothiocyanate, erucin, iberin, phenethyl isothiocyanate, sulforaphane, and sulforaphene (SFEN). Previous studies have shown that ITCs have beneficial effects against bacteria, cancer, and insulin resistance (Ahn et al., 2014; Dufour et al., 2012). SFEN, the representative ITCs in the seeds of radish (Raphanus sativus L.), is known for its efficacy to inhibit adipocyte differentiation (Yang et al., 2020). In Korea, radish seeds have long been called “Nabokja” and are used for traditional prescriptions for indigestion, diarrhea, and intestinal inflammation (Sham et al., 2013). Previous studies have shown that 4-methylthio-butanyl derivatives and phenylpropanoid sucrosides from radish seeds have anti-inflammatory and anti-tumor effects (Kim et al., 2015). In addition, hot water extracts of radish seeds have been reported to show effects on the intestinal inflammation of ulcerative colitis (Choi et al., 2016) and alcoholic fatty liver disease (Park et al., 2021).

Even though studies have reported the beneficial effects of SFEN, the low stability of SFEN is considered to be the biggest obstacle when applying Brassicaceae plants in the pharmaceutical and food industries. The functional group (R-N = C = S) of SFEN has strong electrophilic properties like other ITCs. Therefore, SFEN is highly reactive with nucleophilic compounds such as thiol, hydroxyl, and amino groups, and changed to low bioactive derivatives. In particular, it is known that the decomposition of SFEN is accelerated under protic solvent (Tian et al., 2016a; Tian et al., 2016b), high temperature, and alkali conditions (Song et al., 2013). In addition, ITCs, including SFEN, are rapidly metabolized through the mercapturic acid pathway in liver, which is combining them with the -SH group of a cysteine residue of glutathione (GSH) to form S-(N-alkyl/arylthiocarbamoyl) glutathione (ITC-GSH), and are excreted into urine through kidney. For these reasons, specific conditions is required for storing and delivering SFEN or SFEN-containing materials. Fahey et al. showed that the stability of SFEN in α-cyclodextrin dissolved solution was improved compared to pure water (Fahey et al., 2017). Tian et al. reported that the stability of SFEN was improved after microencapsulation with maltodextrin and hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (Tian et al., 2015).

Nanoemulsion is a dispersion of nanoscale lipid droplets in an emulsion phase. It has unique physicochemical properties to heat, hydrolysis, and light that affect the stability of bioactive substances. Previous studies have reported that nanoemulsion enhanced the stability of quercetin (Dario et al., 2016), and resveratrol (Sessa et al., 2011). In addition, nanoemulsion technology has been broadly used to enhance the bioavailability of low-soluble bioactive components such as β-carotene (Qian et al., 2012), and curcumin (Yucel et al., 2015). However, all of these studies were focused on single active components, but not on dietary supplements like herbal extracts. Separating and purifying SFEN when developing radish seeds as food materials can cause a problem of cost increase. Therefore, in this study, radish seed extract (RSE) containing SFEN was formulated as O/W nanoemulsions, and the stability of SFEN was tested. Since the type of oil and structure of fatty acids in oil can have a significant effect on the stability and properties of nanoemulsion, four different types of commercial edible oils were compared, which are soybean oil, high oleic acid sunflower oil, coconut oil, and hydrogenated palm oil. Furthermore, the pharmacokinetic parameters of RSE-contained nanoemulsions were determined using a rat model.

Materials and methods

Chemical and reagents

High purity SFEN standard (> 98%) was purchased from LKT Laboratories, Inc. (MN, USA). Tween 80 (CAS#: 9005-65-6) and benzene-1,2-dithiol (CAS#: 17534-15-5) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (MO, USA). High-purity ethanol was purchased from Merck (Germany). Commercial soybean oil (CJ Cheiljedang Co., Republic of Korea), high oleic acid sunflower oil (Daesang Co., Republic of Korea), coconut oil (Daesang Co., Republic of Korea), and fully hydrogenated palm oil (Lotte Foods, Republic of Korea) were obtained from online market. All of the other chemicals were analytical grade.

Determination of fatty acids composition

The fatty acid methyl ester (FAME) profile was analyzed by Garcés et al. (Garcés and Mancha, 1993). For transesterification of fat to FAMEs, four types of commercial fat, which are soybean oil (SO), high oleic acid sunflower oil (HOSO), coconut oil (CO), and hydrogenated palm oil (HPO), were reacted with 2 mL methylation mixture (Methanol:Benzene:2,2-dimethoxypropane:H2SO4, 39:20:5:2) and 1 mL of heptane for 2 h at 80 °C. Pentadecanoic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) was used as an internal standard. After cooling down at room temperature, the organic layer was separated and transferred to gas chromatography (7890 A GC, Agilent technology, CA, USA) equipped with flame ionization detector and DB-23 column (1200 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm, Agilent Technology, CA, USA). The injection volume of the sample was 2 µL (split ratio, 1:10). Injector temperature and detector temperature were set to 250 and 280 °C, respectively. The initial oven temperature was set to 80 °C and gradually increased to 250 °C for 59.5 min. The temperature was maintained at 250 °C for 5 min.

Preparation of radish seed extract

The RSE was prepared by the following procedure. The radish seeds were purchased from Anhui Natural Source Impex Co., Ltd. (Anhui, China). They were pulverized into micron-sized particles (volume mean diameter ≈ 11.31 μm) with an industrial milling machine by Westmicro Co., Ltd. (Hwaseong, Republic of Korea). Then the grinded powder was extracted with 20% ethanol and concentrated to remove ethanol. The concentrated solution was freeze-dried in order to obtain RSE powder. The final product was kept at − 20 °C until the fabrication of O/W emulsion. SFEN, one of the main bioactive compounds of RSE, was observed as 49.8 mg/g RSE via HPLC analysis.

Fabrication of RSE-contained nanoemulsion

The RSE-contained oil-in-water emulsion was fabricated with a previously reported method by Ban et al. with slight modifications (Ban et al., 2020). The oil-in-water emulsion comprised 5 wt% of the lipid phase and 95 wt% of the aqueous phase (Table S1). Four different lipid phases of emulsions were prepared by dissolving RSE in ethanol (50 mg/mL) and mixing it respectively with four types of oils (SO, HOSO, CO, and HPO) at 85 °C until ethanol was fully evaporated. This lipid solution was adjusted for RSE to account for 10 wt% of the lipid phases. Then, the aqueous phase was prepared with double deionized water (ddH2O) with tween 80 (2 wt% of total). After preparation of the lipid and aqueous phase, respectively, the lipid phase (5 wt% of total) and aqueous phase (95 wt% of total) was heated at 85 °C and blended with a high-speed blender (HZ1, Labtron, Republic of Korea) at 8000 rpm for 1 min and serially 11,000 rpm for 1 min. The coarse emulsion was further processed with sonication (Q125 Sonicator, Qsonica LLC., CT, USA) for 4 min at 60% amplitude, with a duty cycle of 1 s. Finally, the emulsion was cooled down to 25 °C in a double-jacketed beaker and sonicated for 6 min. The emulsion was stored at 4 °C before the evaluation of emulsion characteristics and storage stability. Blank emulsion was prepared in the same manner as RSE-contained emulsion, but lipid was used instead of RSE.

Characterization of RSE-contained nanoemulsion

The nanoemulsion was diluted with 10-fold ddH2O and filtered through a glass microfiber filter (GF/B, Whatman Ltd.). The filter was dried in an oven at 50 °C, and the weight of the aggregated emulsion was observed by measuring the difference in weight before and after filtration. Particle size (Z-average), Zeta-potential, and PDI of nanoemulsion were measured using Zetasizer with 173° angle helium-neon laser (λ = 633 nm) (Malvern Instruments, UK). Zeta-potential was obtained at 25 °C and electric field strength of 20 V/cm using Smoluchowski equation.

Storage stability of RSE-contained nanoemulsion

The stability of SFEN in RSE-contained nanoemulsion at different temperatures and pH was evaluated. The RSE-contained nanoemulsions stored in three temperature conditions (4, 25, and 50 °C) were collected at regular periods. In addition, RSE-contained nanoemulsions adjusted to acidic (pH 2) and alkaline (pH 9) conditions were stored at 25 °C and collected at the same period. Hydrochloric acid or sodium hydroxide was added to the nanoemulsion (pH 5.24) until it reached the targeted pH. Likewise, RSE dispersed in ddH2O was evaluated under the same temperature and pH conditions as a control. The model equation was estimated with the least square method for the first-order kinetics on residual SFEN-time. The equation of first-order kinetics and half-life (T1/2) was as follows:

where C is SFEN content of the sample at a specific time, C0 is the initial SFEN content of the sample, Y0 is the Y-intercept of the first-order kinetics model, and k is the degrading constant of SFEN.

Determination of sulforaphene contents

SFEN content in RSE-contained nanoemulsion was measured using a cyclocondensation assay (Zhang et al., 1992). The cyclocondensation assay was based on a derivatizing method of SFEN with 1,2-benzenedithiol (BDT). Before the cyclocondensation assay, SFEN was extracted from RSE-contained nanoemulsions, which were collected at regular periods. The nanoemulsions were centrifuged (18,400×g, 15 min, 25 °C) to separate the aqueous and lipid phases. And then, 100 µL of the aqueous phase was liquid-liquid extracted with 1 mL of dichloromethane. The dichloromethane layer was separated and evaporated under vacuum conditions. The dried powder was kept at − 20 °C until cyclocondensation assay. Cyclocondesation reagent was composed of 50% (v/v) of 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 8.5) and 50% (v/v) of 8 mM BDT dissolved in acetonitrile. The SFEN extracted from RSE-contained nanoemulsion was suspended with 100 µL of ddH2O and reacted with 400 µL of cyclocondensation reagent for 1 h at 65 °C. The reaction was stopped by centrifugation (18,400×g, 10 min, 4 °C), and then the supernatant was moved to a 96-well microplate. The absorbance was measured at 365 nm with Epoch Microplate Spectrophotometer (BioTek, VT, USA). The levels of total isothiocyanate in radish seeds were quantified with SFEN using an external standard curve (R2 > 0.99).

Pharmacokinetics study

The pharmacokinetics study was performed under a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Seoul National University (IACUC), Seoul, Republic of Korea (Registration Number SNU-220407-7). Male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 250–300 g were purchased from Central Lab. Animal Inc. (Seoul, Republic of Korea). During the entire experimental period, rats were raised in Seoul National University animal facilities with controlled temperature and humidity. Rats were divided into three groups (n = 3) and orally administered with RSE dissolved in three types of solution (Group 1: water; Group 2: nanoemulsion containing HOSO; Group 3: nanoemulsion containing HPO). Blood (0.5 mL) was collected from the caudal vein at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 h after administration using the heparin-coated tube. The collections were centrifuged (14,000×g, 10 min, 4 °C), and plasma was stored at − 80 °C until chromatographic analysis. The Pharmacokinetic parameters were determined from the plasma concentration of SFEN. The plasma concentration at a specific time was plotted, and the connecting line was drawn between adjacent dots. The maximal plasma concentration of SFEN (Cmax) and time to reach Cmax (Tmax) were obtained from the plasma concentration versus time profile. The area under the curve from 0 to 8 h (AUC0–8h) was calculated according to the linear trapezoidal rule. The elimination rate constant (ke) was estimated by least square linear regression of log-transformed plasma concentration versus time profile. The half-life (T1/2) and area under the curve from 0 to infinity (AUC0–∞) were determined as:

where ke is the elimination rate constant, AUC0–8h is the area under curve from 0 to 8 h, and Clast was the plasma concentration of SFEN at the last time point. The relative bioavailability was expressed as a ratio based on AUC0–∞ of group 1. The oral clearance (CL/F) and volume of distribution (Vd) were determined as follows:

where Dose is the amount of orally administered SFEN per rat weight, AUC0–∞ is the area under curve from 0 to infinity, and ke is the elimination rate constant.

Plasma sulforaphene analysis via LC-MS/MS

The method to evaluate SFEN content from rat blood was slightly adjusted from that of the previous study (Li et al., 2013). First, blood collection from rat with anticoagulants-coated capillary tubes were centrifuged (14,000×g, 10 min, 4 °C) to obtain plasma. 50 µL of plasma was mixed with 400 µL of 0.5% (v/v) formic acid in methanol for 4 min. After then, 400 µL of supernatant was separated by centrifugation (10,000×g, 5 min, 4 °C) and dried under vacuum conditions. The dried sample was suspended with 50% (v/v) acetonitrile of 300 µL. The supernatant was obtained by centrifugation (14,000×g, 10 min, 4 °C) and used for LC-MS/MS analysis. The chromatographic analysis was carried out with a Waters Cortecs C18 column (2.1 × 50 mm, 1.6 μm) maintained at 45 °C using a Thermo Vanquish (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). 1 ul sample was injected into HPLC system, and the flow rate of the mobile phase was 0.4 mL/min. The mobile phase was 0.1% formic acid in 10 mM ammonium formate (solvent A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (solvent B). The following gradient was used: 0–0.5 min, B 5%; 0.5–3 min, B 5–100%; 3–3.25 min, B 100%; 3.25–3.5 min, B 100–5%. The mass analysis was carried out with triple quadrupole, Thermo TSQ Altis (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). Single reaction monitoring was used to track SFEN in positive mode. The precursor ion was monitored at m/z 175.962, and product ions were monitored at m/z 78.000, 87.125, and 112.125. The nebulizer was in the following conditions: Positive ion, 3500 V; Sheath gas flow rate, 50 Arb; Auxiliary gas flow rate, 10 Arb; Sweep gas flow rate, 1 Arb; Ion transfer tube temperature, 325 °C; Vaporizer temperature, 350 °C.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the means ± standard deviations. The significance of differences among groups was assessed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey HSD (p < 0.1, p < 0.05, or p < 0.01). Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS version 23.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., IL, USA).

Results and discussion

Characteristics of RSE-contained nanoemulsions

Nanoemulsions used for the experiments were prepared as described in Materials and methods. It is known that the type and concentration of emulsifier can affect the stability of nanoemulsions. Since the recent consumer preference is to use minimal food additives, the amount of tween 80 was fixed to 2 wt% of total.

The fatty acid compositions of each oil are summarized in Table 1. The degree of unsaturated fatty acids in each oil was in the following order: HOSO (90.7%) > SO (82.4%) > CO (7.8%) > > HPO (0.1%). Oleic acid (C18:1 n-9), which is a kind of mono-unsaturated fatty acid (MUFA), accounted for 82.8% (w/w) of the total fatty acid of HOSO. Linoleic acid (C18:2 n-6), which is a kind of polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA), accounted for 54.6% (w/w) of the total fatty acids of SO. HPO and CO showed a similar composition of fatty acids, but the degree of saturation was higher in HPO (> 99.9%, w/w) compared with CO. Meanwhile, the ratio of long chain fatty acid (LCFA), which have 14 or higher fatty acid, was in the following orders: HOSO (100%) = SO (100%) > HPO (40.9%) ≈ CO (39.8%). HOSO and SO were considered long chain triglycerides (LCT), but HPO and CO comprised more than half of medium chain triglycerides (MCT).

Table 1.

Fatty acid composition of four types of commercial oils

| Name | Abbreviation | Oil composition, mg/g (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SO | HOSO | CO | HPO | ||

| Caproic acid | C6:0 | – | – | 4.89 (1) | 4.33 (1) |

| Caprylic acid | C8:0 | – | – | 58.77 (7) | 54.72 (7) |

| Capric acid | C10:0 | – | – | 47.36 (6) | 43.95 (5) |

| Lauric acid | C12:0 | – | – | 378.85 (47) | 373.40 (46) |

| Myristic acid | C14:0 | – | – | 153.11 (19) | 158.03 (20) |

| Palmitic acid | C16:0 | 97.07 (12) | 37.67 (4) | 79.43 (10) | 79.73 (10) |

| Palmitoleic acid | C16:1 | – | 1.02 (0) | – | – |

| Stearic acid | C18:0 | 36.92 (5) | 29.64 (3) | 27.42 (3) | 89.22 (11) |

| Oleic acid | C18:1 n-9 | 181.04 (23) | 728.15 (83) | 53.56 (7) | 0.99 (0) |

| Linoleic acid | C18:2 n-6 | 435.42 (55) | 66.01 (8) | 9.86(1) | – |

| Alpha-linolenic acid | C18:3 n-3 | 38.90 (5) | – | – | – |

| Arachidic acid | C20:0 | 3.11 (0) | 2.80 (0) | 0.73 (0) | 1.05 (0) |

| Eicosenoic acid | C20:1 | 1.87 (0) | 2.31 (0) | – | – |

| Behenic acid | C22:0 | 3.13 (0) | 8.59 (1) | – | – |

| Lignoceric acid | C24:0 | – | 2.92 (0) | – | – |

| ∑ SFA | 140.23 (18) | 81.62 (9) | 750.56 (92) | 804.42 (100) | |

| ∑ MUFA | 182.90 (23) | 731.49 (83) | 53.56 (7) | 0.99 (0) | |

| ∑ PUFA | 474.32 (59) | 66.01 (8) | 9.86 (1) | – | |

| ∑ LCFA | 797.46 (100) | 879.12 (100) | 324.11 (40) | 329.01 (41) | |

| ∑ MCFA | – | – | 489.87 (60) | 476.39 (59) | |

SO Soybean oil, HOSO High oleic acid sunflower oil, CO Coconut oil, HPO Hydrogenated palm oil, SFA Saturated fatty acids, MUFA Mono-unsaturated fatty acids, PUFA Poly-unsaturated fatty acids, LCFA Long chain fatty acids (chain length ≥ 14), MCFA Medium chain fatty acids (chain length < 14)

The particle size, polydispersity index (PDI), and ζ-potential of nanoemulsions are presented in Table 2. All nanoemulsions had a considerably homogenous particle size distribution (PDI < 0.35). There were no significant differences in the particle size between RSE-contained and blank nanoemulsions. Blank-HOSO and RSE-HOSO showed larger particle sizes (346.6 nm and 342.9 nm) than other oil types. The particle size can be determined by the interfacial tension between oil and water when nanoemulsions are produced by the same method. An increase in interfacial tension between water and oil would result in a more significant force to minimize the surface area. Gmach et al. revealed that the particle size of nanoemulsions fabricated by colloid mill is proportional to the interfacial tension of oil and water (Gmach et al., 2019). In their study, it was observed that the interfacial tension increased in the order of corn oil, peanut oil, sunflower oil, and rapeseed oil, but the particle size of nanoemulsions also increased in the same order. As shown in Table 1, oleic acid, a kind of MUFAs, was the representative fatty acid in HOSO compared to the other oils, and this difference might have affected the interfacial tension of HOSO and the particle size. However, fatty acid composition may not be the only factor determining interfacial tension. Commercial oils may contain minor components, such as flavonoids and polyphenols, which originate from raw materials, which might act as surface active components and lower interfacial tension. In a study by Cong et al., the interfacial tension of 15 vegetable oils was investigated, and it was found that lower interfacial tension was observed in oils manufactured by physical purification processes, such as extra virgin olive oil (Cong et al., 2019). Although most of the minor components can be easily removed through chemical purification, oil contains relatively large amounts of minor components, including phytochemicals, when physical purification is applied. Therefore, the particle size is a complicated result of the interaction between the lipid and aqueous phases in nanoemulsion systems.

Table 2.

Particle size, PDI, and Zeta potential of blank emulsion and RSE-contained emulsion

| Nanoemulsions | Particle size (nm) | PDI | ζ-potential (mV) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SO | ||||||

| Blank-SO | 276.7 ± 8.0c | 0.31 ± 0.13a | − 23.1 ± 0.6e | |||

| RSE-SO | 293.1 ± 12.6bc | 0.30 ± 0.04a | − 10.4 ± 0.2a | |||

| HOSO | ||||||

| Blank-HOSO | 346.6 ± 18.3a | 0.19 ± 0.13a | − 24.7 ± 0.6f | |||

| RSE-HOSO | 342.9 ± 11.7a | 0.21 ± 0.13a | − 10.5 ± 0.3ab | |||

| CCO | ||||||

| Blank-CCO | 324.4 ± 13.7ab | 0.22 ± 0.19a | − 28.4 ± 0.5 g | |||

| RSE-CO | 299.2 ± 11.4bc | 0.25 ± 0.06a | − 13.0 ± 0.4c | |||

| HPO | ||||||

| Blank-HPO | 290.5 ± 13.0bc | 0.24 ± 0.08a | − 21.6 ± 0.4d | |||

| RSE-HPO | 296.4 ± 5.9bc | 0.23 ± 0.07a | − 11.7 ± 0.6bc | |||

Statistical differences were determined by Tukey’s HSD post hoc

Different letters in each column mean a difference at the significant p < 0.05

PDI Polydispersity index

ζ-potential refers to the charge on the surface of nanoemulsions, and the type of surfactants is one of the primary factors in determining it. Although the non-ionic surfactant Tween 80 is generally expected to have a neutral charge, many studies have observed that nanoemulsions containing Tween 80 had negative charges, as was also observed in this study. Cho et al. reported that the negative charge of nanoemulsions with non-ionic surfactants was due to anionic impurities or free fatty acids in the surfactants and oil (Cho et al., 2014). All RSE-contained nanoemulsions had higher ζ-potentials (− 10 to − 13 mV) than their blank nanoemulsions (− 21 to − 28 mV). This result might be due to the partial neutralization of negative charge by the cationic components in RSE.

Storage stability of SFEN in RSE-contained nanoemulsions

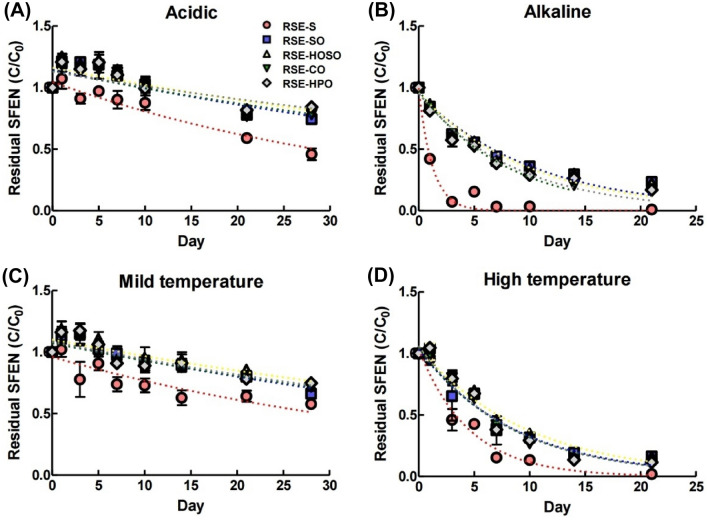

Figure 1 shows the results of storage stability of SFEN in nanoemulsion under acid (pH2) and alkali (pH9) conditions, and mild (25 °C) and high (50 °C) temperature. The dotted line on the graph shows the first-order kinetic model equation for the residual SFEN and time. Table 3 summarizes the rate constant (k) and half-life (T1/2) from each nanoemulsion’s first-order kinetic model equation.

Fig. 1.

The first-order kinetic model of residual SFEN in RSE-contained nanoemulsions and suspension in four different conditions. The four different conditions: acidic condition (pH 2) (A), alkaline condition (pH 9) (B), mild temperature (25 °C) (C), and high temperature (50 °C) (D). RSE contained nanoemulsions composed of four types of oil: soybean oil (RSE-SO), high oleic acid sunflower oil (RSE-HOSO), coconut oil (RSE-CO), and hydrogenated palm oil (RSE-HPO). RSE suspended in water (RSE-S) as a control group

Table 3.

Degradation kinetics parameters of residual SFEN of RSE-contained suspension and emulsion stored in different pH and temperature conditions

| Group | Acidic (pH 2) | Alkaline (pH 9) | Mild temperature (25 °C) | High temperature (50 °C) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k (day−1) | T1/2 (day) | k (day−1) | T1/2 (day) | k (day−1) | T1/2 (day) | k (day−1) | T1/2 (day) | |

| RSE-S | 0.03 ± 0.00a | 25.82 ± 1.40c | 0.81 ± 0.03a | 0.86 ± 0.04d | 0.02 ± 0.00a | 32.08 ± 1.78c | 0.23 ± 0.02a | 3.08 ± 0.25b |

| RSE-SO | 0.02 ± 0.00b | 42.13 ± 1.39b | 0.09 ± 0.00b | 7.59 ± 0.27a | 0.02 ± 0.00b | 41.22 ± 1.64b | 0.12 ± 0.01b | 5.84 ± 0.63a |

| RSE-HOSO | 0.01 ± 0.00bc | 46.68 ± 5.17ab | 0.10 ± 0.00b | 7.15 ± 0.22a | 0.01 ± 0.00c | 47.44 ± 1.04a | 0.11 ± 0.00b | 6.47 ± 0.19a |

| RSE-CO | 0.02 ± 0.00bc | 45.75 ± 0.96b | 0.13 ± 0.01b | 5.38 ± 0.30c | 0.02 ± 0.00bc | 44.77 ± 0.34ab | 0.12 ± 0.01b | 5.64 ± 0.30a |

| RSE-HPO | 0.01 ± 0.00c | 54.75 ± 4.36a | 0.11 ± 0.00b | 6.22 ± 0.21b | 0.02 ± 0.00bc | 44.81 ± 2.79ab | 0.12 ± 0.01b | 5.57 ± 0.25a |

Statistical differences were determined by Tukey’s HSD post hoc

Different letters in each column mean a difference at the significant p < 0.05

k rate constant, T1/2: half-life

The characteristics of SFEN in terms of storage stability could be observed in the result of RSE-S. The ITCs, including SFEN, have strong characteristics to react with nucleophilic compounds containing thiol, hydroxyl, or amine groups. The decomposition reaction of ITCs was known to accelerate under protic solvent (Tian et al., 2016a; Tian et al., 2016b), high temperature, and alkali conditions (Song et al., 2013). According to a study by Song et al., nucleophiles H2S and SFEN react to produce 6-[(methylsulfinyl)methyl]-1,3-thiazinan-2-thione, a decomposition product, especially in alkali rather than acidic conditions (Song et al., 2013). As in the previous study, SFEN in RSE-S were found to be more vulnerable under alkaline conditions. The half-life of SFEN was found to have 25.8 days under acidic conditions and 20.6 h (0.86 days) under alkaline conditions.

Statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) in rate constants and half-lives were observed between nanoemulsions and suspensions under acidic and alkaline conditions, as well as at mild and high temperatures. Regardless of the type of oil, the rate constant of SFEN in nanoemulsions decreased and the half-life increased compared to RSE-S. These results are interpreted as protection of SFEN against hazardous factors, which accelerate the decomposition. The protection of SFEN has been further maximized in harsh environmental conditions such as alkaline conditions or high temperature. Particularly in the case of alkaline conditions, the rate constant of SFEN in nanoemulsions decreased to 1/8 and the half-life increased 6.3 to 8.8 times compared to those of RSE-S. As shown in Table 2, since the surface charge of nanoemulsions is negative, the access of nucleophiles to SFEN would be blocked due to repulsive forces. Furthermore, the ionization of the surface charge is enhanced at high pH, which also increases the protection of SFEN against nucleophiles.

The stability of bioactive compounds can be affected by particle size and the production of radicals in emulsions (Mao et al., 2009). Among the nanoemulsions, RSE-HOSO exhibited higher stability of SFEN under mild temperature (k = 0.01 day−1; T1/2 = 47.44 day) and high temperature (k = 0.11 day−1; T1/2 = 6.47 day) conditions compared to the other emulsions. Table 2 shows that RSE-HOSO has a larger particle size than the other emulsions, meaning that the interfacial area between water and oil is smaller. SFEN is known to be vulnerable to polar protic solvents such as water (Tian et al., 2016b). Therefore, RSE-HOSO, with its relatively larger particle size, is more stable than the other emulsions. This result is consistent with a study by Tan et al., which investigated the stability of β-carotene containing nanoemulsions. It reported that the stability of β-carotene decreases as the particle size of the nanoemulsion becomes smaller (Tan and Nakajima, 2005).

As shown in Table 2, SO is composed of many unsaturated fatty acids, especially PUFAs, and is therefore exposed to the risk of forming radicals. For this reason, SO might have low stability under mild temperatures. However, CO and HPO, composed of saturated fat over 90%, are estimated to be at a relatively lower risk from radical formation. Even HOSO, which has more unsaturated fatty acids, showed higher stability because MUFAs account for most of the fatty acid composition of HOSO. Similarly, Park et al. reported that retinol stability was higher in MCTs oil, composed mainly of saturated fatty acids, than in soybean oil, which has a lot of unsaturated fatty acids (Park et al., 2019). However, no significant differences in half-life and rate constant were observed between RSE-SO, -CO, and -HPO -HOSO under high temperature conditions. The degree of saturation in oils did not have a significant meaning in severe environments such as high temperatures.

Even though the particle size of RSE-HPO was smaller than RSE-HOSO, it showed the highest stability under acidic conditions. This result might have come from the degree of saturation in oil and the formation of radicals rather than the particle size and interfacial area. Mancuso et al. observed that the fatty acid oxidation of oil in water emulsions and oxidative products were produced more under acidic conditions (pH3) than in neutral (pH7). This tendency was particularly pronounced in emulsions with non-ionic surfactants (Mancuso et al., 1999). Therefore, it seems that HPO, mainly composed of saturated fatty acids, has a longer half-life and lower rate constant under acidic conditions than SO, which is composed of polyunsaturated fatty acids (p < 0.05).

Taking these results together, RSE-HOSO showed high stability in mild and high temperature, and alkaline environments due to small interfacial areas of oil and water. Moreover, RSE-HPO, composed of fully saturated fatty acid, have advantageous against decomposition by radicals. Therefore, RSE-HOSO and RSE-HPO have been considered the best options for formulating RSE-contained nanoemulsions. These emulsions, RSE-HOSO and RSE-HPO, were chosen for further research to evaluate the relationship between oil types and the bioavailability of SFEN.

Pharmacokinetics of SFEN in RSE-contained nanoemulsions

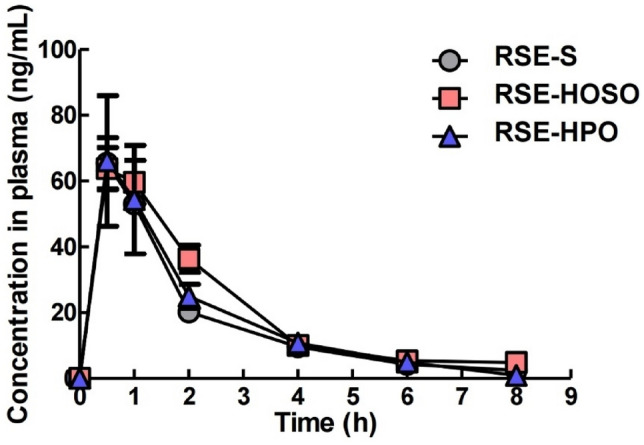

The result of pharmacokinetics are shown in Fig. 2 and its parameters are summarized in Table 4. Cmax showed no significant differences between RSE-HOSO, RSE-HPO, and RSE-S. All Tmax was observed between 0.5 and 1 h. Manjili et al. also reported that Tmax were 0.5 h after oral administration of sulforaphane solution to rats (Kheiri Manjili et al., 2017). AUC0–8h of RSE-HOSO was observed to be 167.1 h·ng/mL, showing a significant difference compared with 133.2 h·ng/mL of RSE-S (p < 0.05). Relative bioavailability was also observed to be 36% higher for RSE-HOSO compared to RSE-S. On the other hand, AUC0–8h of RSE-HPO did not show a significant difference with RSE-S.

Fig. 2.

Plasma SFEN concentration after oral administration of RSE-contained nanoemulsions and suspension to rats. RSE-S, RSE suspended in water; RSE-HOSO, RSE-contained nanoemulsion with high oleic acid sunflower oil; RSE-HPO, RSE-contained nanoemulsion with hydrogenated palm oil

Table 4.

Pharmacokinetic profile of RSE-contained suspension and emulsion

| Group | Suspension | Nanoemulsions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RSE-S | RSE-HOSO | RSE-HPO | |

| Dose (mg/kg) | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 66.3 ± 12.1 | 69.5 ± 9.1 | 72.9 ± 25.8 |

| Tmax (h) | 0.5–1 | 0.5–1 | 0.5–1 |

| AUC0–8h (h·ng/mL) | 133.2 ± 7.2 | 167.1 ± 14.4** | 143.7 ± 42.4 |

| AUC0–∞ (h·ng/mL) | 146.4 ± 10.8 | 199.1 ± 37.3* | 148.3 ± 38.6 |

| ke (1/h) | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 0.24 ± 0.07 |

| T1/2 (h) | 3.8 ± 0.2 | 4.2 ± 0.8 | 3 ± 0.8 |

| CL/F (l/h/kg) | 13.7 ± 1 | 10.3 ± 1.8** | 14.1 ± 3.7 |

| Vd (l/kg) | 74.2 ± 6.3 | 60.5 ± 8* | 63.7 ± 32.9 |

| Relative bioavailability | 1 | 1.36 | 1.01 |

Statistical differences were determined by Student’s t-test

Cmax peak concentration, Tmax time to reach Cmax, AUC0–8h Area under the curve from 0 to 8 h, AUC0–∞ are under the curve from 0 h to ∞, ke elimination rate, T1/2 half-life, CL/F oral clearance, Vd Volume of distribution

Superscript *, ** means difference at the significant level of p < 0.10 and p < 0.05 compared to S

The bioavailability of bioactive substances is determined by bioaccessibility, absorption, and transformation (McClements et al., 2015). All three factors are important for the transport of bioactive substances to the circulation system, but after absorption, the transformation of bioactive substances becomes the dominant factor in determining bioavailability (McClements et al., 2015). The bioavailability of RSE-HOSO and RSE-S was attributed to differences in oral clearance (CL/F). In pharmacokinetics, oral clearance represents a value that indicates the extent to which a substance is metabolized or excreted from the body. The oral clearance of RSE-HOSO and RSE-S were 10.3 and 13.7 l/h/kg, respectively (p < 0.05). In other words, the oral clearance of RSE-HOSO was three fourth of RSE-S. On the other hand, RSE-HPO oral clearance did not show a significant difference with RSE-S.

The reason why RSE-HOSO showed lower oral clearance could be found in the fatty acid composition of HOSO. One of the well-studied ITCs is sulforaphane, which has a similar structure to SFEN, and is known to be metabolized via the mercapturic pathway (Janczewski, 2022). The mercapturic acid pathway is a subsequent transformation of ITCs that are conjugated with glutathione (ITC-GSH) by glutathione S-transferase (GST) and are serially converted to cysteine (ITC-CYS) and N-acetyl-l-cysteine (ITC-NAC). This mainly occurs in the liver due to abundant GSH and high GST activity (Kim, Lee et al., 2015). Therefore, it is essential to bypass the liver for retarding the metabolism of SFEN. As shown in Table 1, the ratio of LCFA was analyzed to be 40.9% in HPO and 100% in HOSO. Therefore, HOSO is considered LCTs, and HPO is mainly composed of MCTs. It has been known that MCTs are degraded from the intestine to medium chain fatty acids and absorbed into the liver via portal veins. In contrast, LCTs are absorbed into lymphatic vessels and undergo peripheral circulation (Porter et al., 2007). Because LCT’s absorption mechanism bypasses the liver, research has attempted to design the composition of carrier oils to sustain active components in the circulation system. Caliph et al. conducted a pharmacokinetics study about the malaria drug halofantrine (Caliph et al., 2000). In addition to affecting the absorption and metabolism of active substances, fatty acid chain length is known to affect bioaccessibility. Ozturk et al. published a study showing that vitamin D3 bioaccessibility in nanoemulsions using LCTs such as fish oil and corn oil was higher than MCTs (Ozturk et al., 2015). In a similar study, Qian et al. revealed that LCT was superior to MCT in terms of β-carotene bioaccessibility (Qian et al., 2012).

A study on cannabinoids-contained SNEDDS (self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system) reported by Izgelov et al. showed that AUCinf of cannabinoids in LCT-SNEDDS increased by approximately 30% compared with MCT-SNEDDS. This study used sesame oil and cocoa butter as LCTs, but significant results were observed only in cocoa butter. Cocoa butter has a relatively high proportion of saturated fatty acids compared to sesame oil. Saturated fatty acids are known to form chylomicrons better in enterocytes, and these differences are thought to have influenced uptake to lymphocyte uptake (Izgelov et al., 2020). In the present study as well, it seems possible to conduct a comparative study according to the degree of saturation of LCT in further studies.

In this study, RSE-contained nanoemulsions were prepared with four commercial oils to evaluate the storage stability and bioavailability of SFEN in RSE. Two factors, the particle size of nanoemulsions and the fatty acid composition of oil, influenced the stability and bioavailability of SFEN. The particle size of emulsions is directly related to interfacial area between water and oil, and unsaturated fatty acids are easily exposed to the formation of radicals. RSE-HOSO, of which the lipid phase is composed of HOSO, had a relatively larger particle size and showed superior storage stability compared with the other nanoemulsions under mild and high temperature, and alkaline conditions. Meanwhile, RSE-HPO, mainly composed of saturated fatty acids in the lipid phase, exhibited higher stability than HOSO under acidic conditions. The SFEN bioavailability of RSE-HOSO and RSE-HPO were compared in a pharmacokinetics study of orally administered rats. In this study, it was found that RSE-HOSO exhibited higher bioavailability and lower oral clearance, which might be attributed to LCFA of HOSO, mainly absorbed through the lymphatic pathway rather than the portal vein. Consequently, RSE-contained nanoemulsions composed of HOSO exhibited enhanced storage stability and bioavailability of SFEN due to the larger particle size and adequate composition of fatty acid composition. This study could provide guidelines for developing RSE as functional foods and pharmaceuticals designed for efficiently storing and delivering bioactive components, SFEN.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT, Ministry of Science and ICT) (No. 2021R1F1A1062871 and 2018R1C1B6008236).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Tae Kyung Lee and Gihyun Hur have equally contributed to this work as co-first authors.

Contributor Information

Tae Kyung Lee, Email: vluetk@snu.ac.kr.

Gihyun Hur, Email: ginnyhur@hanmail.net.

Jeongyoon Choi, Email: c08290910@gmail.com.

Choongjin Ban, Email: pahncj@uos.ac.kr.

Jong-Yea Kim, Email: jongkim@kangwon.ac.kr.

Hee Yang, Email: yhee6106@kookmin.ac.kr.

Jung Han Yoon Park, Email: jyoon@hallym.ac.kr.

Ki Won Lee, Email: kiwon@snu.ac.kr.

Jong Hun Kim, Email: JongHunKIM@sungshin.ac.kr.

References

- Ahn J, Lee H, Im SW, Jung CH, Ha TY. Allyl isothiocyanate ameliorates insulin resistance through the regulation of mitochondrial function. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 2014;25:1026–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ban C, Jo M, Park YH, Kim JH, Han JY, Lee KW, Kweon DH, Choi YJ. Enhancing the oral bioavailability of curcumin using solid lipid nanoparticles. Food Chemistry. 2020;302:125328. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caliph SM, Charman WN, Porter CJH. Effect of short-, medium-, and long-chain fatty acid-based vehicles on the absolute oral bioavailability and intestinal lymphatic transport of halofantrine and assessment of mass balance in lymph-cannulated and non-cannulated rats. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2000;89:1073–1084. doi: 10.1002/1520-6017(200008)89:8<1073::AID-JPS12>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho HT, Salvia-Trujillo L, Kim J, Park Y, Xiao H, McClements DJ. Droplet size and composition of nutraceutical nanoemulsions influences bioavailability of long chain fatty acids and coenzyme q10. Food Chemistry. 2014;156:117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.01.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K-C, Cho S-W, Kook S-H, Chun S-R, Bhattarai G, Poudel SB, Kim M-K, Lee K-Y, Lee J-C. Intestinal anti-inflammatory activity of the seeds of raphanus sativus l. In experimental ulcerative colitis models. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2016;179:55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong Y, Zhang W, Liu C, Huang F. Composition and oil-water interfacial tension studies in different vegetable oils. Food Biophysics. 2019;15:229–239. doi: 10.1007/s11483-019-09617-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dario MF, Oliveira CA, Cordeiro LRG, Rosado C, Mariz IdFA, Maçôas E, Santos MSCS, Minas da Piedade ME, Baby AR, Velasco MVR. Stability and safety of quercetin-loaded cationic nanoemulsion: In vitro and in vivo assessments. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects. 2016;506:591–599. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2016.07.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dufour V, Alazzam B, Ermel G, Thepaut M, Rossero A, Tresse O, Baysse C. Antimicrobial activities of isothiocyanates against campylobacter jejuni isolates. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2012;2:53. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahey JW, Wade KL, Wehage SL, Holtzclaw WD, Liu H, Talalay P, Fuchs E, Stephenson KK. Stabilized sulforaphane for clinical use: Phytochemical delivery efficiency. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 2017;61:1600766. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201600766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcés R, Mancha M. One-step lipid extraction and fatty acid methyl esters preparation from fresh plant tissues. Analytical Biochemistry. 1993;211:139–143. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gmach O, Bertsch A, Bilke-Krause C, Kulozik U. Impact of oil type and ph value on oil-in-water emulsions stabilized by egg yolk granules. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects. 2019;581:123788. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2019.123788. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Izgelov D, Shmoeli E, Domb AJ, Hoffman A. The effect of medium chain and long chain triglycerides incorporated in self-nano emulsifying drug delivery systems on oral absorption of cannabinoids in rats. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2020;580:119201. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janczewski Ł. Sulforaphane and its bifunctional analogs: Synthesis and biological activity. Molecules. 2022;27:1750. doi: 10.3390/molecules27051750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kheiri Manjili H, Sharafi A, Attari E, Danafar H. Pharmacokinetics and in vitro and in vivo delivery of sulforaphane by pcl-peg-pcl copolymeric-based micelles. Artificial Cells, Nanomedicine, and Biotechnology. 2017;45:1728–1739. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2017.1282501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KH, Kim CS, Park YJ, Moon E, Choi SU, Lee JH, Kim SY, Lee KR. Anti-inflammatory and antitumor phenylpropanoid sucrosides from the seeds of raphanus sativus. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2015;25:96–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YJ, Lee DH, Ahn J, Chung WJ, Jang YJ, Seong KS, Moon JH, Ha TY, Jung CH. Pharmacokinetics, tissue distribution, and anti-lipogenic/adipogenic effects of allyl-isothiocyanate metabolites. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0132151. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Zhang T, Li X, Zou P, Schwartz SJ, Sun D. Kinetics of sulforaphane in mice after consumption of sulforaphane-enriched broccoli sprout preparation. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 2013;57:2128–2136. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201300210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso JR, McClements DJ, Decker EA. The effects of surfactant type, ph, and chelators on the oxidation of salmon oil-in-water emulsions. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 1999;47:4112–4116. doi: 10.1021/jf990203a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao L, Xu D, Yang J, Yuan F, Gao Y, Zhao J. Effects of small and large molecule emulsifiers on the characteristics of β-carotene nanoemulsions prepared by high pressure homogenization. Food Technology and Biotechnology. 2009;47:336–342. [Google Scholar]

- McClements DJ, Zou L, Zhang R, Salvia-Trujillo L, Kumosani T, Xiao H. Enhancing nutraceutical performance using excipient foods: Designing food structures and compositions to increase bioavailability. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 2015;14:824–847. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ozturk B, Argin S, Ozilgen M, McClements DJ. Nanoemulsion delivery systems for oil-soluble vitamins: Influence of carrier oil type on lipid digestion and vitamin d3 bioaccessibility. Food Chemistry. 2015;187:499–506. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.04.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H, Mun S, Kim YR. Uv and storage stability of retinol contained in oil-in-water nanoemulsions. Food Chemistry. 2019;272:404–410. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.08.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park WY, Song G, Noh JH, Kim T, Kim JJ, Hong S, Park J, Um J-Y. Raphani semen (Raphanus sativus L.) ameliorates alcoholic fatty liver disease by regulating de novo lipogenesis. Nutrients. 2021;13:4448. doi: 10.3390/nu13124448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter CJ, Trevaskis NL, Charman WN. Lipids and lipid-based formulations: Optimizing the oral delivery of lipophilic drugs. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2007;6:231–248. doi: 10.1038/nrd2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian C, Decker EA, Xiao H, McClements DJ. Nanoemulsion delivery systems: Influence of carrier oil on β-carotene bioaccessibility. Food Chemistry. 2012;135:1440–1447. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessa M, Tsao R, Liu R, Ferrari G, Donsi F. Evaluation of the stability and antioxidant activity of nanoencapsulated resveratrol during in vitro digestion. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2011;59:12352–12360. doi: 10.1021/jf2031346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sham T-T, Yuen AC-Y, Ng Y-F, Chan C-O, Mok DK-W, Chan S-W. A review of the phytochemistry and pharmacological activities of raphani semen. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013;2013:636194. doi: 10.1155/2013/636194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song D, Liang H, Kuang P, Tang P, Hu G, Yuan Q. Instability and structural change of 4-methylsulfinyl-3-butenyl isothiocyanate in the hydrolytic process. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2013;61:5097–5102. doi: 10.1021/jf400355d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan C, Nakajima M. Β-carotene nanodispersions: Preparation, characterization and stability evaluation. Food Chemistry. 2005;92:661–671. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.08.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tian G, Li Y, Cheng L, Yuan Q, Tang P, Kuang P, Hu J. The mechanism of sulforaphene degradation to different water contents. Food Chemistry. 2016;194:1022–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.08.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian G, Li Y, Yuan Q, Cheng L, Kuang P, Tang P. The stability and degradation kinetics of sulforaphene in microcapsules based on several biopolymers via spray drying. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2015;122:5–10. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian G, Tang P, Xie R, Cheng L, Yuan Q, Hu J. The stability and degradation mechanism of sulforaphene in solvents. Food Chemistry. 2016;199:301–306. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Kang MJ, Hur G, Lee TK, Park IS, Seo SG, Yu JG, Song YS, Park JHY, Lee KW. Sulforaphene suppresses adipocyte differentiation via induction of post-translational degradation of ccaat/enhancer binding protein beta (c/ebpβ) Nutrients. 2020;12:758. doi: 10.3390/nu12030758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yucel C, Quagliariello V, Iaffaioli RV, Ferrari G, Donsi F. Submicron complex lipid carriers for curcumin delivery to intestinal epithelial cells: Effect of different emulsifiers on bioaccessibility and cell uptake. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2015;494:357–369. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Cho C-G, Posner GH, Talalay P. Spectroscopic quantitation of organic isothiocyanates by cyclocondensation with vicinal dithiols. Analytical Biochemistry. 1992;205:100–107. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90585-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.