Abstract

Introduction

Acute postoperative pain is a major concern among surgical patients. Thus, this study established a new acute pain management model and compared the effects of the acute pain service (APS) model in 2020 and the virtual pain unit (VPU) model in 2021 on postoperative analgesia quality.

Methods

This retrospective, single-center clinical study involved 21,281 patients from 2020 to 2021. First, the patients were grouped on the basis of their pain management model (APS and VPU). The incidence of moderate to severe postoperative pain (MSPP) [numeric rating scale (NRS) score ≥ 5], postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), and postoperative dizziness were recorded.

Results

The VPU group recorded significantly lower MSPP incidence (1–12 months), PONV, and postoperative dizziness (1–10 months and 12 months) compared with the APS group. In addition, the annual average incidence of MSPP, PONV, and postoperative dizziness in the VPU group was significantly lower than in the APS group.

Conclusions

The VPU model reduces the incidence of moderate to severe postoperative pain, nausea, vomiting, and dizziness; hence, it is a promising acute pain management model.

Keywords: Acute pain service, Postoperative analgesia, Virtual pain unit

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| The acute pain service (APS) model does not solve the high incidence of postoperative pain. |

| A new pain management model (virtual pain unit) VPU was established and compared with APS. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| The VPU model is associated with improved quality of postoperative analgesia. |

| The VPU model reduced the incidence of moderate to severe postoperative pain nausea and vomiting and dizziness compared with the APS model. |

Introduction

Global statistics have shown that approximately 312.9 million operations are performed annually [1]. The surgical volume will continue to grow with socioeconomic development, but even lifesaving surgery is potentially harmful to the human body, such as pain during and after the procedure. Despite the progress in understanding pain mechanisms, physiology, and pharmacology, healthcare providers still face challenges in postoperative pain management. For instance, Gan et al. [2] reported that 86% of patients experienced postoperative pain, and among this population, 75% suffered moderate to severe pain during the immediate postoperative period. Poor management of postoperative pain continues to be a major healthcare problem worldwide. Undertreatment of postoperative pain has adverse impacts, including delayed recovery, extended hospital stay, increased morbidity, poor quality of life, and patient dissatisfaction [3].

Recent advances have prompted the establishment and implementation of pain management guidelines [4], acute pain services (APS) [5], multimodal analgesia [6], procedure-specific pain management (PROSPECT) [7] strategies, and the introduction of new drugs and devices [8]. Nevertheless, undertreatment of postoperative pain has remained unchanged for decades [9]. The APS was introduced as a new organizational structure to improve postoperative analgesia and has been implemented for the past three decades [10]. Healthcare providers continue to discuss the acute pain management model [11] as the APS faces new challenges and opportunities in the era of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS).

In this study, a novel, virtual-ward-based and cloud-ward-based model [12–14] of postoperative pain management, namely a virtual pain unit (VPU), was established. This model is designed to assemble patients requiring postoperative pain management in a virtual care unit. This innovative VPU model of postoperative pain management is a potential upgrade from the APS model to enhance postoperative analgesia. This study retrospectively analyzed postoperative analgesia quality before and after VPU establishment between 2020 and 2021.

Methods

The APS model was introduced in Zhengzhou Central Hospital on 1 January 2020. A part-time faculty anesthesiologist and three full-time perianesthesia nurses managed this perianesthesia, nurse-led postoperative pain management model. The responsibilities of an APS anesthesiologist encompass daily operating room (OR) anesthesia and advice on perioperative analgesia regimens for the OR anesthesia team. Subsequently, the OR anesthesia team performs the regional block analgesia if necessary, according to the APS anesthesiologist’s recommendation. Meanwhile, the APS perianesthesia nurses, under the guidance of the APS anesthesiologist, were mainly tasked with pain rounds for patients who received postoperative pain management, including patient-control analgesia (PCA) pump daily ward inspection, adjustment of PCA pump parameters under the supervision of attending anesthesiologist, and patients’ pain education and health promotion.

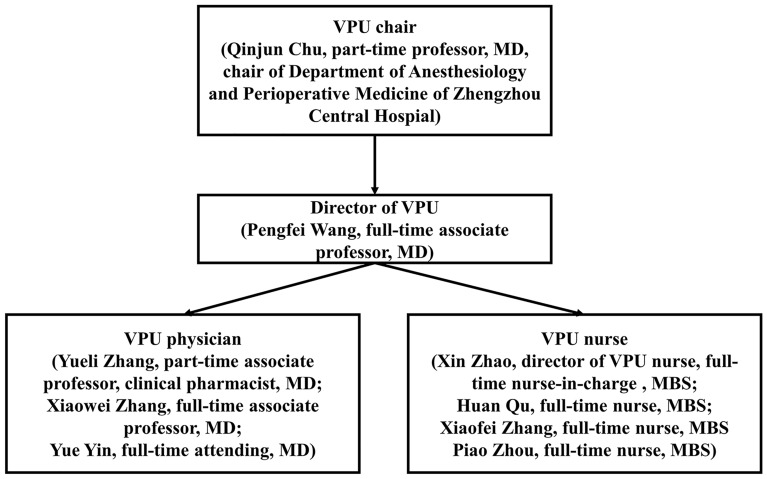

The VPU is an anesthesiologist-led model of postoperative pain management. All the surgical patients requiring pain management, according to the hospital information system (HIS), were “admitted” to the VPU before surgery while physically remaining in the surgical ward. The patients’ medical records were independently stored in a VPU electronic medical record system. This unit is now an independent virtual nursing unit (see Fig. 1). Patients who were admitted to the VPU were managed by a group of three anesthesiologists who are experts in regional anesthesia, four perianesthesia nurses who are independent of OR perianesthesia nursing services and a part-time clinical pharmacist who is an expert in analgesic pharmacology (see Fig. 2).

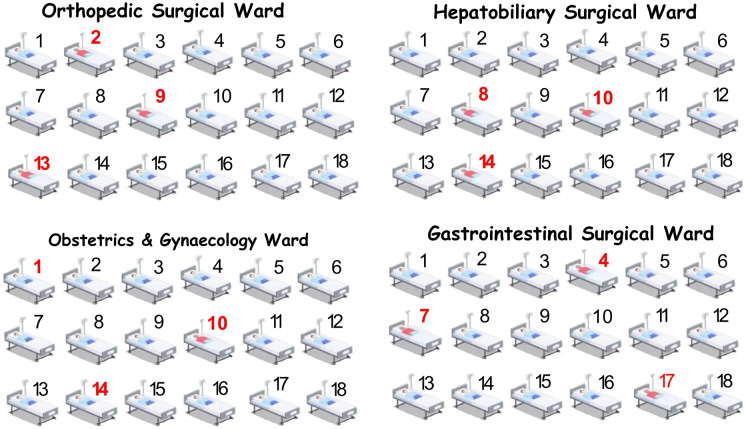

Fig. 1.

A schematic diagram of the VPU. Arabic numeral 1–18 represents hospital bed numbers in the ward. The numbers in red represent the patients that require postoperative analgesia. The red dashed box represents the VPU

Fig. 2.

The VPU staff organizational structure

The VPU anesthesiologists (VPU physicians) are not involved in OR anesthesia-related daily work and are mainly responsible for preoperative regional analgesia-related procedures, hospital acute pain consults, VPU patients’ daily pain rounds, and in-patient regional analgesia-related procedures. Likewise, the VPU perianesthesia nurses (VPU nurses) are not involved in OR anesthesia-related daily work. They are assigned to assist VPU physicians with their daily work, conducting pain education and health promotion and daily rounds with VPU physicians. The VPU clinical pharmacist provides analgesia-related pharmacy service, including joint pain rounds with the VPU physician once or twice weekly, implements detailed pharmacy consultation for the VPU team, surgery team, and patients, and supervises drug overdose and adverse drug reaction.

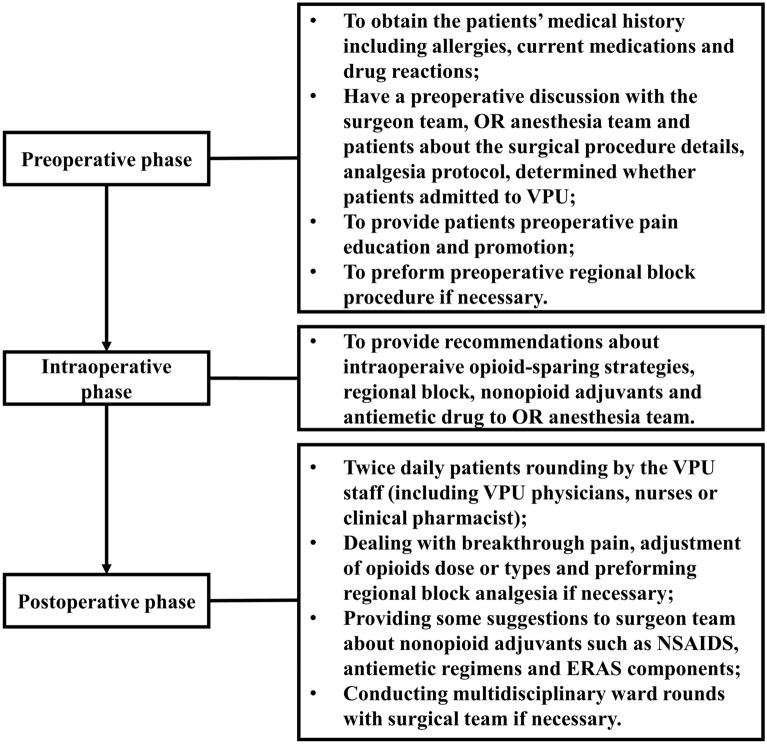

The VPU physicians also provide whole-process perioperative pain interventions, focusing on patients’ identification, pain education, and communication with the surgical team during the preoperative phase. Furthermore, they offer intraoperative opioid-sparing pain management recommendations to the OR anesthesia team, including suggestions for regional block, non-opioid adjuvants, and antiemetic drugs. The VPU physicians were responsible for managing all the VPU patients’ perioperative pain regimen until an acceptable pain intensity was achieved without intervention or the transition to oral pain medication. Moreover, this team provided postoperative pain services, including dealing with breakthrough pain, adjustment of opioid dose or types, and performing regional block analgesia if necessary. They advise surgeons about non-opioid adjuvants, such as nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), antiemetic regimens, and ERAS components. The daily routine of VPU physicians and nurses includes rounding the patients twice daily and creating a culture of open communication with the surgical team. Additionally, the VPU physicians and nurses occasionally conducted multidisciplinary ward rounds with the surgical team if required (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The workflow of VPU staff

As this retrospective study did not involve any identifying patient information, clinical trial registration was not required and was exempted from the Zhengzhou Central Hospital ethics committee. First, medical records of patients who received postoperative pain management between 1 January 2020 and 31 December 2021 were collected from the anesthesia information management system (AIMS) (Dacheng software, Zhengzhou, China) and hospital information system (HIS) (Neusoft Group Co., Ltd., Shenyang, China) of Zhengzhou Central Hospital. The study was divided into the pre-VPU establishment (APS model for postoperative pain management, 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2020) and the VPU establishment period (VPU model for postoperative pain management, 1 January 2021 to 31 December 2021). The inclusion criteria were patients who received postoperative pain management and were > 18 years old. Meanwhile, the exclusion criteria were incomplete clinical data, chronic pain, long-term use of analgesic drugs, postoperative transfer to the intensive care unit (ICU) for various reasons, and cognitive dysfunction.

The patients’ demographic data, including age, height, weight, gender, and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade, were collected for this study. In addition, the incidence of moderate to severe postoperative pain (MSPP) [numeric rating scale (NRS) score ≥ 5], postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), and postoperative dizziness in patients who received postoperative pain management (monthly data between 1 January 2020, to 31 December 2021) were obtained. Meanwhile, the incidence of MSPP, PONV, and postoperative dizziness in each sub-specialty patient was recorded monthly throughout the study. The patients’ average length of stay (ALOS) in the hospital, per capita cost of hospitalization, per capita number of ward rounds, patient controlled intravenous analgesia (PCIA) utilization rate, the coverage rate of nerve block, per capita opioid consumption (including sufentanil, remifentanil, and oxycodone, expressed by equivalent morphine in mg) were also acquired for this study.

No sample size was calculated as this was a retrospective study. The R software (R version 4.2.0) was applied to analyze all statistical data. The measurement data of normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and the comparison of mean between the two groups was performed by a two independent samples t-test. The counting data were expressed by the number of cases (%), and the comparison was performed by the chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

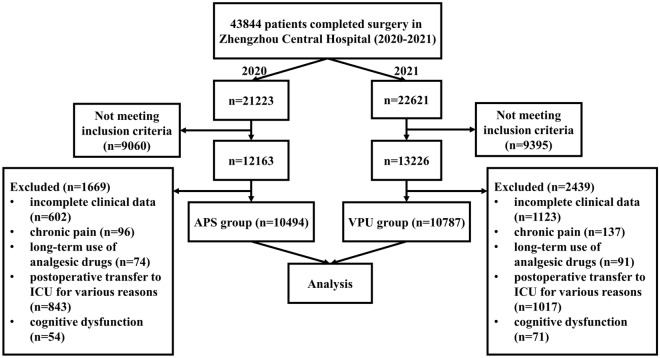

A total of 43,844 patients (2020 = 21,223, 2021 = 22,621) for OR surgical procedures from 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2021 were retrieved from the HIS database of Zhengzhou Central Hospital. After screening the potential candidates on the basis of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 10,494 patients were included in the APS group in 2020 and 10,787 patients in the VPU group in 2021 (see Fig. 4).There was no significant difference in age, height, weight, gender, ASA grade, and the number of sub-specialty between the two groups (P > 0.05) (see Table 1).

Fig. 4.

Flow chart of study cohort selection

Table 1.

Demographics of APS and VPU patients

| Index | APS (n = 10,494) | VPU (n = 10,787) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 47.52 ± 17.78 | 46.60 ± 18.73 |

| Height (cm) | 162.47 ± 14.13 | 164.20 ± 11.84 |

| Weight (kg) | 66.82 ± 71.96 | 69.96 ± 73.85 |

| Gender (n, %) | ||

| Male | 3855 (36.74%) | 3871 (35.89%) |

| Female | 6639 (63.26%) | 6916 (64.11%) |

| ASA (n, %) | ||

| I | 423 (4.03%) | 487 (4.52%) |

| II | 8785 (83.71%) | 9088 (84.25%) |

| III | 1187 (11.31%) | 1134 (10.51%) |

| IV | 99 (0.95%) | 78 (0.72%) |

| Sub-specialty | ||

| Bariatric surgery | 451 (4.30%) | 522 (4.84%) |

| Gastrointestinal surgery | 314 (2.99%) | 355 (3.29%) |

| Hepatobiliary surgery | 403 (3.84%) | 439 (4.07%) |

| Urology surgery | 1005 (9.58%) | 914 (8.47%) |

| Anorectal surgery | 227 (2.16%) | 208 (1.93%) |

| TESS | 410 (3.91%) | 381 (3.53%) |

| Orthopedic surgery | 1033 (9.84%) | 964 (8.94%) |

| Gynecologic surgery | 1850 (17.63%) | 2004 (18.58%) |

| Obstetric surgery | 1281 (12.21%) | 1177 (10.91%) |

| OM surgery | 602 (5.74%) | 672 (6.23%) |

| ENT surgery | 1289 (12.28%) | 1426 (13.22%) |

| Thoracic surgery | 151 (1.44%) | 138 (1.28%) |

| Thyroid surgery | 615 (5.86%) | 689 (6.39%) |

| Neurosurgery | 144 (1.37%) | 163 (1.51%) |

| Breast surgery | 719 (6.85%) | 735 (6.81%) |

APS acute pain service, VPU virtual pain unit, ASA American Society of Anesthesiologists, TESS transforaminal endoscopic spine surgery, OM oral and maxillofacial, ENT ear-nose-throat

Data are presented as mean ± SD, number of patients (%)

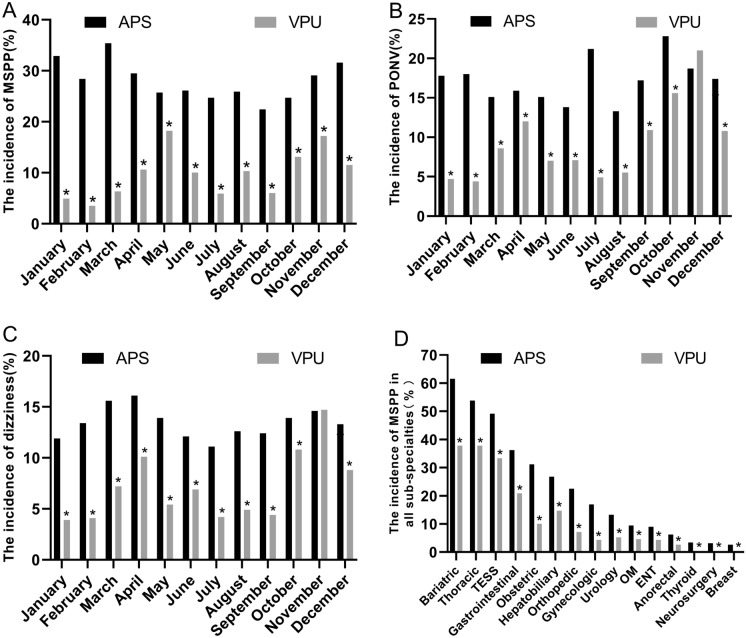

The VPU group recorded significantly lower incidence of MSPP (1–12 months) (see Fig. 5A), PONV (see Fig. 5B), postoperative dizziness (1–10 months, 12 months) (see Fig. 5C), and annual average incidence of MSPP in all sub-specialties (see Fig. 5D) (P < 0.05) than the APS group. Additionally, the average annual incidence of MSPP, PONV, and postoperative dizziness in the VPU group was significantly lower (P < 0.05) compared with the APS group (see Table 2).

Fig. 5.

Assessment of VPU group. A The incidence of MSPP per month in the two models, B the incidence of PONV per month in the two models, C the incidence of postoperative dizziness per month in the two models, and D the average annual incidence of MSPP in all sub-specialties of the two models. *P < 0.05. APS acute pain service, VPU virtual pain unit, MSPP moderate to severe postoperative pain, PONV postoperative nausea and vomiting, TESS transforaminal endoscopic spine surgery, OM oral and maxillofacial, ENT ear-nose-throat

Table 2.

Annual average incidence of MSPP, PONV, and dizziness among patients’ post-surgery

| Index | APS (n = 10,494) | VPU (n = 10,787) | Difference between APS and VPU (△) | Percentage of reduction (α) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSPP (%) | 2941(28.03%) | 1056 (9.79%) | 18.24% | 65.07% |

| PONV (%) | 1804(17.19%) | 1012 (9.38%) | 7.81% | 45.43% |

| Dizziness (%) | 1407(13.41%) | 768 (7.12%) | 6.29% | 46.91% |

APS acute pain service, VPU virtual pain unit, MSPP moderate to severe postoperative pain, PONV postoperative nausea and vomiting

Data are presented as number of patients (%)

△ = APS−VPU, α = [(APS−VPU)/APS] × 100%

There was no statistical difference between the two groups in terms of ALOS (5.1 ± 3.0 versus 4.7 ± 2.9, P > 0.05). Meanwhile, the per capita hospitalization cost was $2422 ± 655 and $2563 ± 605, respectively (P > 0.05), and the per capita number of rounds was 2 ± 1 and 5 ± 1, respectively (P < 0.001) from 2020 to 2021. On the other hand, the PCIA utilization rate (33.82% versus 41.06%, P < 0.001), the coverage rate of a nerve block (20.51% versus 44.37%, P < 0.001), and opioid consumption per capita (morphine equivalents) (116.5 ± 23.6 mg versus 142.6 ± 15.2 mg, P < 0.05) were significantly increased in the VPU group.

Discussion

The effect of the VPU model for postoperative pain management on postoperative analgesia quality was explored in this study. This model offered improved postoperative analgesia quality and reduced adverse effects post-surgery, such as PONV and postoperative dizziness, than the traditional APS model for postoperative pain management. The current healthcare facility demonstrated a decrease in MSPP (65%), PONV (45%), and postoperative dizziness (47%) incidence when the VPU model was implemented compared with the APS model.

Postoperative pain has not been addressed appropriately for decades. The guidelines [4] issued by the American Pain Society in 2016 indicated that 80% of patients experienced acute pain post-surgery, 75% claimed to experience moderate, severe, or even extreme pain postoperation, and < 50% received good analgesia after undergoing their procedure. In 2021, Vasilopoulos et al. [15] from the University of Florida in the USA showed that 63% of patients experienced moderate to severe pain within seven days postoperatively. Likewise, a large-scale multicenter study from Denmark [16] exhibited that 20% of patients experienced moderate to severe pain immediately after awakening. After the development of APS 30 years ago, the implementation has improved postoperative analgesia quality tremendously. Nevertheless, the system is facing significant challenges and requires further upgrading.

Various APS models have been reported in the literature, including physician-led [9] and nurse-led [17] operation models. A stand-alone APS model independent of OR was widely discussed recently [11], potentially enhancing multimodal pain management and improving postoperative analgesia quality. In the present study, a novel VPU model was designed on the basis of the “virtual ward” concept to create an independent virtual nursing unit. The VPU, or stand-alone APS, was fully staffed with dedicated anesthesiologists, perianesthesia nurses, and part-time clinical pharmacists. An organizational structure was established to achieve the goals and enhance postoperative analgesic quality. The selected staff managed the VPU patients similar to those in general wards by conducting daily pain rounds and remotely monitoring operations via a PCA internet of things (IoT) (microchip, base station, and central station) [18] for timely adjustments.

The current healthcare institution upgraded the conventional APS model to the VPU model to effectively manage acute postoperative pain. The findings indicated that the VPU model reduced the incidence of MSPP (28.3% to 9.79%), PONV (17.19% to 9.38%), and the incidence of postoperative dizziness (13.41% to 7.12%). Furthermore, the VPU model supported the regional analgesia-based, opioid-sparing, multimode analgesic strategies to promote the implementation of the ERAS program, such as DREAMS (Drinking, Eating, Analgesic, Mobilising, Sleeping) [19]. In addition, the coverage rate of the nerve block was increased in the VPU model compared with APS. Optimization of analgesic regimen using the new model reduced the incidence of PONV and postoperative dizziness, suggesting that VPU is a promising and improved alternative to APS for postoperative pain management. Despite that, there were no significant differences in the incidence of PONV and dizziness in November between the two models, mainly due to more gastrointestinal surgeries in the VPU group than in the APS group (21.2% versus 9.4%). Gastrointestinal surgeries are attributed to a higher incidence of PONV and dizziness [20].

Moderate–severe pain was commonly observed among patients that underwent bariatric, thoracic, gastrointestinal, obstetric, hepatobiliary, and transforaminal endoscopic spine surgeries (TESS) compared with other sub-specialties. Gerbershagen et al. [21] also found that postoperative pain intensity differed significantly on the first day after surgery among various surgical procedures. The recognition led to developing evidence-based recommendations for PROSPECT. Thus, healthcare providers are strongly advised to adhere to the PROSPECT strategy in managing postoperative pain.

No statistical differences were identified between the two groups in terms of ALOS, but there was a tendency for ALOS to decrease. It is postulated that further upgrades of the VPU model could reduce ALOS, as this model is still new and ALOS shortening is complex. Moreover, the VPU model improved the PCIA utilization rate and the coverage rate of nerve block, which may increase per capita hospitalization cost and opioid consumption but reduce the incidence of acute postoperative pain. The slight increase in per capita hospitalization cost is deemed worthwhile to improve the patient’s medical experience. In addition, the VPU model is under continuous improvement to create an optimal pain management model that reduces the per capita hospitalization cost and enhances the patient’s future medical experience. In view of the current opioid-free concept, the developers of this study also aim to improve the coverage rate of nerve blocks.

The number of ward rounds per capita in the VPU model is double that of the APS model. This method allows the staff to listen to the patients’ concerns, provide the best comfort and care, and improve patients’ experience, enhancing the VPU model through continuous feedback. Furthermore, the extra time and interaction increase the opportunity for bedside education for patients and create a good rapport between the anesthesiologists and patients. The VPU also aligns with the concept of anesthesia and perioperative medicine, improves patients’ postoperative management, and expands anesthesiologists’ services. Another advantage of the VPU model is the complete organizational structure, multidisciplinary personnel ratio, individualized analgesia regimen, and quality control, which substantially reduces the interval between the onset of acute pain and relief, improves the treatment efficiency, and reduces the workload of OR anesthesiology team. In conclusion, the VPU is an innovative acute pain management model that improves the status quo of postoperative patient pain management.

This study has several limitations. First, there may be confounding factors and bias in the data in the present retrospective study, and the reliability of the results is not as high as that of prospective studies. Therefore, future studies are essential to validate the model performance. Secondly, this study is a single-center study, which may differ in operation type, number, and demography from other centers. Thus, large-scale multicenter research should be performed to confirm the viability of the VPU model. Finally, nearly half of the patients were excluded from the screening process as most patients included in APS and VPU mainly had MSPP. Local anesthesia surgery (minimally invasive mammotome biopsy, cataract surgery) and surgery with mild postoperative pain (vitrectomy, hysteroscopy) were not included. In the end, nearly half of the patients were finally excluded after considering other inclusion and exclusion criteria. Nonetheless, the physician can conduct APS or VPU for treatment if patients experience MSPP.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated the viability and efficacy of VPU model in reducing the incidence of moderate to severe postoperative pain, nausea, vomiting, and dizziness, compared with APS. Therefore, this new model is a promising solution for acute pain management among postoperative patients.

Acknowledgements

We thank each sub-specialty for their help in implementing our VPU model.

Funding

This study was supported by the Soft Science Research Program of Henan (Zhengzhou Bureau of Science and Technology) (fund title: study on the construction and evaluation of virtual pain unit). The rapid service fee was funded by the authors.

Medical Writing Assistance

We are thankful to William Pat Fong of the Home for Researchers editorial team (www.home-for-researchers.com) for language editing service. Funding for this service was provided by corresponding author Qinjun Chu.

Authorship

All authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, supervision, and writing (review and editing): Qinjun Chu and Hongkai Lian. Investigation and project administration: Yue Yin, Xiaowei Zhang, Yanling Ma, Gang Quan, Yueli Zhang, Xin Zhao, Huan Qu, Piao Zhou, Xiaofei Zhang, and Huaibin Zhang. Formal analysis and writing (original draft): Guanyu Yang, Shanshan Zuo, and Pengfei Wang.

Disclosures

Guanyu Yang, Shanshan Zuo, Pengfei Wang, Yue Yin, Xiaowei Zhang, Yanling Ma, Gang Quan, Yueli Zhang, Xin Zhao, Huan Qu, Piao Zhou, Xiaofei Zhang, Huaibin Zhang, Hongkai Lian, and Qinjun Chu declare no conflicts of interest.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

As this retrospective study did not involve any identifying patient information, clinical trial registration was not required and was exempted from the Zhengzhou Central Hospital ethics committee.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during, and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Footnotes

Guanyu Yang, Shanshan Zuo and Pengfei Wang have contributed equally to this work: co-first authorship.

Hongkai Lian and Qinjun Chu have contributed equally to this work: joint correspondence.

Contributor Information

Hongkai Lian, Email: lhklzdavid716@zzu.edu.cn.

Qinjun Chu, Email: jimmynetchu@163.com.

References

- 1.Weiser TG, Haynes AB, Molina G, Lipsitz SR, Esquivel MM, Uribe-Leitz T, et al. Estimate of the global volume of surgery in 2012: an assessment supporting improved health outcomes. Lancet. 2015;385(Suppl 2):S11. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60806-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gan TJ, Habib AS, Miller TE, White W, Apfelbaum JL. Incidence, patient satisfaction, and perceptions of post-surgical pain: results from a US national survey. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30(1):149–160. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2013.860019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cousins MJ, Brennan F, Carr DB. Pain relief: a universal human right. Pain. 2004;112(1–2):1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chou R, Gordon DB, de Leon-Casasola OA, Rosenberg JM, Bickler S, Brennan T, et al. Management of postoperative pain: a clinical practice guideline from the american pain society, the american society of regional anesthesia and pain medicine, and the american society of anesthesiologists' committee on regional anesthesia, executive committee, and administrative council. J Pain. 2016;17(2):131–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ready LB, Oden R, Chadwick HS, Benedetti C, Rooke GA, Caplan R, et al. Development of an anesthesiology-based postoperative pain management service. Anesthesiology. 1988;68(1):100–106. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198801000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beverly A, Kaye AD, Ljungqvist O, Urman RD. Essential elements of multimodal analgesia in Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) guidelines. Anesthesiol Clin. 2017;35(2):e115–e143. doi: 10.1016/j.anclin.2017.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kehlet H. Procedure-specific postoperative pain management. Anesthesiol Clin North Am. 2005;23(1):203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.atc.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang R, Wang S, Duan N, Wang Q. From patient-controlled analgesia to artificial intelligence-assisted patient-controlled analgesia: practices and perspectives. Front Med (Lausanne) 2020;7:145. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tawfic QA, Faris AS. Acute pain service: past, present and future. Pain Manag. 2015;5(1):47–58. doi: 10.2217/pmt.14.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stamer UM, Liguori GA, Rawal N. Thirty-five years of acute pain services: where do we go from here? Anesth Analg. 2020;131(2):650–656. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Missair A, Visan A, Ivie R, Gebhard RE, Rivoli S, Woodworth G. Daring discourse: should acute pain medicine be a stand-alone service? Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2021;46(6):529–531. doi: 10.1136/rapm-2020-102288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewis G. Case study: virtual wards at Croydon primary care trust. London UK: The King’s Fund; 2006. Available from: http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/fielddocument/PARR-croydon-pct-case-study.pdf

- 13.Lewis G, Vaithianathan R, Wright L, Brice MR, Lovell P, Rankin S, et al. Integrating care for high-risk patients in England using the virtual ward model: lessons in the process of care integration from three case sites. Int J Integr Care. 2013;13:e046. doi: 10.5334/ijic.1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim KX, Chen YT, Chiu KM, Hung FM. Rush Hour: Transform a modern hotel into cloud-based virtual ward care center within 80 hours under COVID-19 pandemic. Far eastern MemorialHospital’s experience. J Formos Med Assoc. 2022;121(4):868–869. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2021.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vasilopoulos T, Wardhan R, Rashidi P, Fillingim RB, Wallace MR, Crispen PL, et al. Patient and procedural determinants of postoperative pain trajectories. Anesthesiology. 2021;134(3):421–434. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rasmussen AM, Toft MH, Awada HN, Dirks J, Brandsborg B, Rasmussen LK, et al. Waking up in pain: a prospective unselected cohort study of pain in 3702 patients immediately after surgery in the Danish Realm. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2021;46(11):948–953. doi: 10.1136/rapm-2021-102583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mackintosh C, Bowles S. Evaluation of a nurse-led acute pain service. Can clinical nurse specialists make a difference? J Adv Nurs. 1997;25(1):30–37. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997025030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sahu D, Pradhan B, Khasnobish A, Verma S, Kim D, Pal K. The internet of things in geriatric healthcare. J Healthc Eng. 2021;2021:6611366. doi: 10.1155/2021/6611366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levy N, Mills P, Mythen M. Is the pursuit of DREAMing (drinking, eating and mobilising) the ultimate goal of anaesthesia? Anaesthesia. 2016;71(9):1008–1012. doi: 10.1111/anae.13495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horn CC, Wallisch WJ, Homanics GE, Williams JP. Pathophysiological and neurochemical mechanisms of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;722:55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.10.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerbershagen HJ, Aduckathil S, van Wijck AJ, Peelen LM, Kalkman CJ, Meissner W. Pain intensity on the first day after surgery: a prospective cohort study comparing 179 surgical procedures. Anesthesiology. 2013;118(4):934–944. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31828866b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during, and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.