Highlights

-

•

Government in the United States is considering annual COVID-19 boosters.

-

•

We conducted a panel survey to investigate popular attitudes toward annual booster.

-

•

Partisan self-identification and trust in government correlate with these attitudes.

Abstract

Objectives

On January 26, 2023, an advisory panel of the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a plan for annual vaccination for COVID-19. Given slowing booster uptake in the US, full participation of the public is in doubt. Using data from a longitudinal survey, we investigated the predictors of attitudes toward receiving a COVID-19 booster dose annually.

Study design

In February 2023, we completed a panel study of 243 adults from South Dakota who indicated being at least fully vaccinated in a survey conducted in May 2022.

Methods

In addition to attitudes on an annual booster, we measured partisan self-identification, trust in government, interpersonal trust, COVID-19 vaccination status, age, gender, education, and income. We examined the effect of changes in COVID-19 vaccination status, and the two trust variables on the willingness to receive a COVID-19 booster dose annually.

Results

Logistic regression analysis results showed statistically significant relationships between partisan self-identification, changes in trust in government and COVID-19 vaccination status, age, and the willingness to receive a COVID-19 booster dose annually.

Conclusions

The findings underscore the continued relevance of partisan self-identification and trust in government on attitudes toward COVID-19 mitigation measures.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to threaten public health in the United States. On January 11, 2023, the Department of Health and Human Services extended its designation of the COVID-19 pandemic as a public health emergency. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has recommended vaccination as a form of protection from COVID-19. The majority of scholars agree that vaccines protect from hospitalization and death from COVID-19, nevertheless, their effectiveness wanes over time, particularly for older adults [1]. Bivalent boosters appear to be effective against both new and old variants of the virus [2], [3], however, researchers acknowledge lingering uncertainties, such as their long-term side effects and effectiveness against future strains [4].

Despite their wide availability, only 20 % of adults have received the updated (bivalent) booster as of March 2023 [5]. According to one study, if the vaccination rate stays the same as in 2022, between 89,000 and 120,000 people will die annually from COVID-19 in the United States over the next decade. The number of deaths could be reduced to 10,000 a year with an 84 % vaccination rate [6].

Given the low booster uptake rate, public health authorities have been seeking strategies to protect society from COVID-19 long-term. Various options to increase COVID-19 vaccination rates have previously been explored, such as public encouragements and making vaccination compulsory. However, public encouragements proved ineffective at convincing the vaccine-hesitant population and mandatory vaccination proved divisive. In September 2021, the federal government announced mandatory COVID-19 vaccination for healthcare workers (HCWs) and military personnel. Additional mandates were put in place in November 2021 through an emergency rule by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), for employers with 100 or more employees. However, these mandates sparked protests and were strongly opposed by many, particularly self-identified Republicans [7]. Vaccine mandates were promptly challenged in court, with the former being allowed to stand and the latter being struck down in January 2022. However, the Biden administration announced on May 1, 2023, that most federal vaccination mandates will be lifted. Overall, the development of a policy that would simultaneously increase vaccine uptake and have public support has been a continuing challenge since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

One obstacle to increasing COVID-19 vaccine uptake has been the constantly changing vaccination schedule. Experts recommend harmonizing the COVID-19 vaccination schedule [8]. Governments around the world, such as in the United Kingdom and Taiwan, started exploring how to routinize COVID-19 vaccination annually. Scholars have provided evidence for the benefits of vaccination routinization. One study estimated that receiving a COVID-19 vaccination yearly, increased protection and prevented 75 % of infections, compared to 55 % after an 18-month gap between vaccinations [9].

The federal government in the United States has begun to make concrete steps toward streamlining the COVID-19 vaccination schedule. On January 26, 2023, an advisory panel of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a plan for annual vaccination for COVID-19. Experts have called this plan the “biggest change to the COVID-vaccination regimen” [10]. The FDA argued that this proposal would simplify the vaccination regimen, streamline vaccine deployment, and clarify communication about vaccination [11]. Dr. Anthony Fauci, the former chief medical adviser of President Biden said during a media interview that administering booster doses annually would “get more people to get into a rhythm of keeping up to date” [12]. Despite a positive reception by the scientific community, some experts said that more data are needed to determine if administering a vaccine dose annually was the best policy. [10].

How will the public respond to receiving a COVID-19 booster annually? Given the sensitive nature of COVID-19 vaccination, the success of the new policy will depend to a large degree on its reception by the public. The Biden administration was forced to abandon mandatory COVID-19 vaccination for some groups due to the anger [13] and the strong popular opposition it triggered.

This paper uses data from a longitudinal survey to investigate popular attitudes toward an annual COVID-19 vaccine. The longitudinal research design has advantages over the cross-sectional design used in most studies investigating people’s attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination. It is likely that people’s attitudes toward vaccination, or key determinants of those attitudes, evolved since the start of the pandemic. While the threat posed by the virus is still serious, it is waning compared to a few years ago. Pandemic fatigue might have affected some people’s willingness to comply with mitigation measures [14]. Some people who were initially open to the first vaccination sequence might now be reluctant to receive additional boosters. However, for other people, their experiences might have made them more supportive of vaccination and more open to receiving annual boosters. Such changes may drive attitudes toward annual COVID-19 booster uptake. It is advantageous to use a research design that can capture changes in people’s attitudes. We add to the growing number of studies investigating people’s attitudes toward the COVID-19 pandemic over time [15], [16], [17].

Additionally, we contribute to the existing scholarship by investigating whether attitudes toward an annual COVID-19 booster are driven by the factors that predicted people’s attitudes toward COVID-19 mitigation at the start of the pandemic, particularly partisan self-identification and trust in government. Scholars demonstrated that attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination are linked to demographic factors, such as gender, age, and evangelical Christian identity [18], [19], [20], psychological factors, such as personality traits [21] and scientific reasoning [22], as well as socio-economic factors, such as household income [23]. Nevertheless, since its start, the management of the COVID-19 pandemic has been highly structured on a partisan dimension. Scholars reported partisan self-identification and trust in government as strong predictors of individual-level attitudes and behaviors on COVID-19 vaccine uptake and compliance with lockdowns [24], [25], [26]. As annual COVID-19 is being considered, it is important to understand whether people’s attitudes toward this policy will be shaped by these factors.

Methods

Study design

In February 2023, we completed a panel study of 243 adults from South Dakota who indicated being at least fully vaccinated in a survey conducted in May 2022.

Data

Our data came from an original longitudinal survey examining popular attitudes toward the COVID-19 pandemic. The first wave was fielded in South Dakota from May 2 to 15, 2022. Using the registration-based sampling method [27], we randomly selected 21,000 individuals from the list of registered voters obtained from the Secretary of State for public opinion research. Those selected received a mailed invitation letter to participate in a survey administered online on the QuestionPro survey platform. Each invitation letter contained the URL address and QR code to access the survey, as well as a unique personal identification number that unlocked the survey.

We originally received 1,199 responses, yielding a response rate of 5.5 %, which is on par with other surveys using the registration-based sampling method [16], [27], [28]. As a part of the survey, respondents could opt into the panel by providing their email addresses. We collected email addresses from 833 respondents. Nine months later, on February 16, 2023, those participants received an invitation email to take part in a short follow-up survey. Between February 16 and 26, 290 respondents completed the second survey wave. Fig. S1 shows the data collection flowchart.

Both survey waves were conducted by the authors and received approval from the Institutional Review Board of [University name and approval number redacted for peer review]. All respondents provided consent for participation in both surveys. Participants did not receive compensation for completing either of the two survey waves. Following best practices in survey research, we included a single attention check question in the second wave. A total of 7 respondents failed the test (2.8 %). We did not uncover any appreciable or substantively important differences between statistical models where those participants who failed the attention check question were included or excluded. We, therefore, kept those participants in the sample and models reported.

Measures

The dependent variable was the likelihood of receiving a COVID-19 booster dose annually. We measured the variable with a single question using a 1–5 Likert scale in the second survey wave. Time-variant variables were derived from questions measuring COVID-19 vaccination status, trust in government, and interpersonal trust from both surveys. We collected data on age, gender, education, income, and partisan self-identification during the first survey wave. We provided the full text of all survey questions in the supplementary appendix.

Changes in trust in government and interpersonal trust were modeled by subtracting the values of the first wave from the second wave of the survey (t2 − t1). Congruent with prior research [16], we expect to see some changes in the values of trust between survey waves within individuals, given the politicization of virtually all COVID-19 mitigation measures. We suspect that those who were more inclined to support various COVID-19 mitigation efforts may have increased their trust in government reinforced given the government response to the pandemic. Meanwhile, those predisposed to oppose COVID-19 mitigation measures may have seen their trust in government undermined. Positive scores indicate an increase of trust within an individual between the two waves on the respective variable. Conversely, a negative score indicates a decrease between survey waves. Positive values of either variable should be associated with a routinization of COVID-19 vaccination.

Change in COVID-19 vaccination status was another time-variant independent variable. We constructed an indicator to capture whether a person received an additional booster dose using questions measuring COVID-19 vaccination status. For example, answers from individuals whose vaccination status changed from being fully vaccinated to being fully vaccinated and boosted were coded as “1″. And, answers from participants whose vaccination status remained unchanged since the last survey were coded as “0”.

We measured partisan self-identification on an ordinal scale. Though partisan self-identification can be treated as a multinomial variable, psychology and political science researchers commonly measure it ordinally since respondents identifying as “independents” place themselves between the two parties spatially on the same dimension [24], [29].

Analysis

We first described our sample and then estimated an ordered logistic regression using the likelihood of receiving a COVID-19 booster dose annually as the dependent variable. The other variables mentioned above served as independent variables. Afterward, predicted probabilities were estimated for the likelihood of respondents answering “very likely” on the question of receiving an annual booster for COVID-19 on the two statistically significant continuous variables – partisan self-identification and age. We analyzed the data in Stata 17 [30] and used the spost package to estimate the regression model [31].

Results

Overall, 290 participants completed both surveys. During the first survey, 248 reported being at least fully vaccinated. Of those, 49 % were male and 51 % were female. The average age was 59 years, and over 66 % received at least a 4-year college degree. Over 67 % of participants reported a change in COVID-19 vaccination status; 50 % of the sample registered differences between waves on trust in government, whereas 44 % changed scores on interpersonal trust. Concerning the willingness to receive a COVID-19 booster dose annually, 15 % reported being very unlikely, 8 % unlikely, 6 % were neither likely, nor unlikely, 13 % were likely, and 58 % were very likely to receive a COVID-19 booster dose annually.

Table 1 displayed results from the ordered logistic regression. We observed statistically significant associations between changes in COVID-19 vaccination status (β = 2.622, p < 0.001), change in trust in government (β = 0.417, p = 0.019), age (β = 0.021, p = 0.045), and willingness to receive a COVID-19 booster dose annually. The associations between other variables and the dependent variable were not statistically significant. McFadden’s r-square value of 0.2470 suggested a well-specified model. A low variance inflation factor score (mean VIF score of 1.14) did not indicate the presence of multicollinearity.

Table 1.

Ordered logistic regression of willingness to receive annual COVID-19 booster.

| Partisan self-identification | −0.996*** |

| (0.211) | |

| Age | 0.021* |

| (0.010) | |

| Change in trust in government | 0.418* |

| (0.179) | |

| Change in vaccination status | 2.623*** |

| (0.341) | |

| Change in interpersonal trust | 0.044 |

| (0.181) | |

| Gender | 0.451 |

| (0.312) | |

| Education | 0.013 |

| (0.118) | |

| Income | −0.077 |

| (0.109) | |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.247 |

| Observations | 228 |

Standard errors in parentheses.

***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

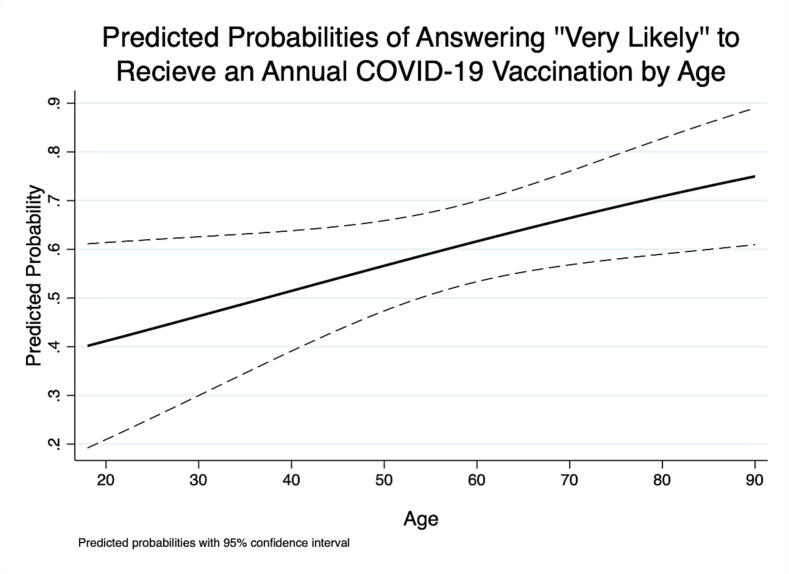

As Fig. 1 showed, the probability of Democrats answering “very likely” was 0.800, whereas Republicans had a probability of 0.353. Fig. 2 demonstrated the significant effect of age. A 20-year-old respondent had a probability of 0.412 of being very likely to receive an annual booster, as opposed to a 70-year-old having a 0.664 probability of the same.

Fig. 1.

Predicted probabilities of answering “very likely” to receive an annual COVID-19 vaccination by partisan self-identification.

Fig. 2.

Predicted probabilities of answering “very likely” to receive an annual COVID-19 vaccination by age.

Discussion

COVID-19 vaccination remains a politically divisive topic even three years after the start of the pandemic. During its early stages, vaccines, and vaccination policy were a point of contestation between the Democratic and Republican parties. Scholars showed that partisan self-identification strongly predicted vaccine uptake, booster, and attitudes toward mandatory vaccination [7], [24]. Our findings suggest that even after three years, people’s attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination remain split along partisan lines. Experts are concerned that the continued divide over partisan lines might affect attitudes toward other vaccines [32]. A political consensus toward COVID-19 vaccination and bipartisan support for mitigation policies developed by scientists is urgently needed.

Our results showed that older adults indicated a higher willingness to receive a COVID-19 booster dose annually. Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicated that older adults are at greatest risk of hospitalization and death from COVID-19 than younger adults [33]. Older adults are the population group that is most at risk, and experts recommend that they receive additional doses regularly. Previously, scholars reported that age correlates with attitudes and behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. More specifically, older adults are therefore more likely to be vaccinated and support various mitigation policies [20], [23]. Our findings are consistent with these studies. It is encouraging that older adults showed greater willingness to receive a booster dose annually.

Our findings also showed that the people who reported a positive change in trust in government were also more likely to receive a COVID-19 booster annually. Given the many uncertainties regarding the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly the issue of vaccination, trust in government has been a key predictor of people’s COVID-19-related attitudes and behaviors [25], [34]. For example, citizens might not have detailed knowledge of how COVID-19 vaccines work, such as the mRNA technology. Given the uncertainties and a large amount of misinformation, those with higher trust in government will have warmer feelings toward vaccines because their use was authorized by the government. Trust in government might have evolved during the COVID-19 pandemic as the number of COVID-19-related hospitalizations and deaths fluctuated. One study showed that changes in trust in government were linked to compliance with expert-recommended health behaviors [34]. Our finding that those individuals with a positive shift in their trust in government are more likely to receive a COVID-19 vaccination annually is consistent with those expectations.

We also found that a positive change in COVID-19 vaccination status was linked to a greater willingness to receive a booster dose annually. Those people who received an additional vaccine dose between survey waves are also more likely to receive a vaccination annually. Given the magnitude of the threat posed by COVID-19 at the start of the pandemic, compliance with mitigation guidelines was high. However, scholars were concerned that it might drop over time [35]. Some studies reported a substantial decrease [15], others did not note a difference [36], while others observed greater guidelines compliance [37]. Our results underscore that attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination change over time, and public health officials should be mindful of these changes could interfere with their efforts to stop the spread of the virus.

We also note some limitations of our study. Our sample is composed only of those adults who are registered to vote. Therefore, those individuals who only recently moved to the state and have not yet updated their registration would not be included. Those residents who are not eligible to vote would likewise be excluded. Additionally, our sample is older and more educated than the general population. We believe this slight imbalance to be an artifact of the recruitment method, as older and more educated adults are more likely to be registered to vote than younger adults and less educated adults. While this brings fewer respondents into the sample relative to their proportion in the general population, there were still enough to show clear statistically significant differences in the hypothesized directions on the dependent variable.

Our participants come only from one state, and our findings might not be representative of the national population. South Dakota is overwhelmingly white, high in religiosity, and comparatively conservative. Additionally, the state's political leaders expressed strong resistance to some COVID-19 mitigation strategies, such as COVID-19 “vaccination passports” or vaccine mandates. As such, the South Dakota electorate is more predisposed than the broader population of the United States to be more hostile towards many aspects of COVID-19 mitigation, including regular vaccination. In some respects, this makes the state a good “least likely” case study, due to the COVID-19 skeptical population.

Another limitation of this study is that both trust in government and interpersonal trust were measured using a single item. Single-item measures have been long used by social scientists to investigate the link between trust in government and attitudes towards various policy areas [38], including the COVID-19 pandemic [39], [40]. Nevertheless, multiple-item measures exist for trust in government [41] and interpersonal trust [42]. Arguably such multiple-item measures would provide a finer-grained assessment, even though evidence exists that single-item measures are equally valid and reliable [43].

Conclusion

In this study, we used data from an original longitudinal survey to study predictors of popular attitudes toward receding a COVID-19 booster dose annually. We found that older adults and self-identified Democrats are more likely to do so. The routinization of COVID-19 vaccination might be one way to increase people’s confidence in vaccination and stop the spread of anti-vaccine activism that has grown since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Findings from this study will contribute to the scholarship that explores people’s attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination as the pandemic wears on, yet threatens public health. The results will also be valuable to public health officials as they seek to create strategies to increase the public’s confidence in an annual COVID-19 booster.

Ethics approval

This study received approval from South Dakota State University’s research compliance officer.

Consent to participate

All participants consented to participate in our study.

Funding

This work was supported by South Dakota State University.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Filip Viskupič: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. David L. Wiltse: Formal analysis, Visualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvacx.2023.100337.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Figure S1: Data collection flowchart.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Menni C., May A., Polidori L., Louca P., Wolf J., Capdevila J., et al. COVID-19 vaccine waning and effectiveness and side-effects of boosters: a prospective community study from the ZOE COVID Study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22(7):1002–1010. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00146-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bobrovitz N., Ware H., Ma X., Li Z., Hosseini R., Cao C., et al. Protective effectiveness of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection and hybrid immunity against the omicron variant and severe disease: a systematic review and meta-regression. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023;23(5):556–567. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00801-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Link-Gelles R., Ciesla A.A., Fleming-Dutra K.E., Smith Z.R., Britton A., Wiegand R.E., et al. Effectiveness of bivalent mRNA vaccines in preventing symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection — increasing community access to testing program, United States, September–November 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(48):1526–1530. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7148e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mohamed K., Rzymski P., Islam M.S., Makuku R., Mushtaq A., Khan A., et al. COVID-19 vaccinations: the unknowns, challenges, and hopes. J Med Virol. 2022;94(4):1336–1349. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CDC. COVID data tracker. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2020, March 28. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker [accessed on March 9, 2023].

- 6.Yang F, Tran TN-A, Howerton E, Boni MF, Servadio JL. Benefits of near-universal vaccination and treatment access to manage COVID-19 burden in the United States. medRxiv; 2023. doi: 10.1101/2023.02.08.23285658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Viskupič F., Wiltse D.L., Kayaalp A. Attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccine mandate: the role of psychological characteristics and partisan self-identification. Pers Individ Differ. 2023;206 doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2023.112119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kozlov M. Should COVID vaccines be given yearly? Proposal divides US scientists. Nature. 2023 doi: 10.1038/d41586-023-00234-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Townsend J.P., Hassler H.B., Dornburg A. Infection by SARS-CoV-2 with alternate frequencies of mRNA vaccine boosting. J Med Virol. 2023;95(2):e28461. doi: 10.1002/jmv.28461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu KJ. The flu-ification of COVID policy is almost complete. The Atlantic; 2023, January 26. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2023/01/annual-seasonal-covid-vaccine-shots-federal-regulation/672854.

- 11.FDA. FDA briefing document future vaccination regimens addressing COVID-19; 2023, January 26. https://www.fda.gov/media/164699/download.

- 12.Castronuovo C. It’s too soon for annual Covid booster shots, some experts say. Bloomberg Law; 2023, February 7. https://news.bloomberglaw.com/health-law-and-business/its-too-soon-for-annual-covid-booster-shots-some-experts-say.

- 13.Sprengholz P., Betsch C., Böhm R. Reactance revisited: Consequences of mandatory and scarce vaccination in the case of COVID-19. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2021;13(4):986–995. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bodas M., Adini B., Jaffe E., Kaim A., Peleg K. Lockdown efficacy in controlling the spread of COVID-19 may be waning due to decline in public compliance, especially among unvaccinated individuals: a cross-sectional study in Israel. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(9) doi: 10.3390/ijerph19094943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franzen A., Wöhner F., Zia A. Fatigue during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence of social distancing adherence from a panel study of young adults in Switzerland. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0261276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Viskupič F., Wiltse D.L. Trust in physicians predicts COVID-19 booster uptake among older adults: evidence from a panel survey. Aging Health Res. 2023;3(1) doi: 10.1016/j.ahr.2023.100127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang J., Zhu H., Lai X., Zhang H., Huang Y., Feng H., et al. From COVID-19 vaccination intention to actual vaccine uptake: A longitudinal study among Chinese adults after six months of a national vaccination campaign. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2022;21(3):385–395. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2022.2021076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corcoran K.E., Scheitle C.P., DiGregorio B.D. Christian nationalism and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and uptake. Vaccine. 2021;39(45):6614–6621. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.09.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khubchandani J., Sharma S., Price J.H., Wiblishauser M.J., Sharma M., Webb F.J. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in the United States: a rapid national assessment. J Community Health. 2021;46(2):270–277. doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00958-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reiter P.L., Pennell M.L., Katz M.L. Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among adults in the United States: how many people would get vaccinated? Vaccine. 2020;38(42):6500–6507. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin F.-Y., Wang C.-H. Personality and individual attitudes toward vaccination: a nationally representative survey in the United States. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1759. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09840-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Čavojová V., Šrol J., Ballová Mikušková E. How scientific reasoning correlates with health-related beliefs and behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic? J Health Psychol. 2022;27(3):534–547. doi: 10.1177/1359105320962266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Callaghan T., Moghtaderi A., Lueck J.A., Hotez P., Strych U., Dor A., et al. Correlates and disparities of intention to vaccinate against COVID-19. Soc Sci Med. 2021;272:113638. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Motta M. Republicans, not democrats, are more likely to endorse anti-vaccine misinformation. Am Politics Res. 2021;49(5):428–438. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trent M., Seale H., Chughtai A.A., Salmon D., MacIntyre C.R. Trust in government, intention to vaccinate and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: a comparative survey of five large cities in the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia. Vaccine. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.06.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Camobreco J.F., He Z. The party-line pandemic: a closer look at the partisan response to COVID-19. PS: Polit Sci Polit. 2022;55(1):13–21. doi: 10.1017/S1049096521000901. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barber M.J., Mann C.B., Monson J.Q., Patterson K.D. Online polls and registration-based sampling: a new method for pre-election polling. Polit Anal. 2014;22(3):321–335. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sokhey A.E., Djupe P.A. Name generation in interpersonal political network data: results from a series of experiments. Soc Netw. 2014;36:147–161. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2013.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peng Y. Politics of COVID-19 vaccine mandates: left/right-wing authoritarianism, social dominance orientation, and libertarianism. Pers Individ Differ. 2022;194 doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2022.111661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.StataCorp . StataCorp LLC; College Station, TX: 2021. Stata statistical software: release 17. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Long S., Freese J. 3rd Ed. Stata Press; 2014. Regression models for categorical dependent variables using Stata. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Motta M. Is partisan conflict over COVID-19 vaccination eroding support for childhood vaccine mandates? npj Vaccines. 2023;8(1):5. doi: 10.1038/s41541-023-00611-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.CDC. Cases, data, and surveillance. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-age.html [accessed on March 23, 2023].

- 34.Suhay E., Soni A., Persico C., Marcotte D.E. Americans’ trust in government and health behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. RSF: Russell Sage Found J Soc Sci. 2022;8(8):221–244. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Michie S., West R., Harvey N. The concept of “fatigue” in tackling covid-19. BMJ. 2020;371 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wright L., Steptoe A., Mak H.W., Fancourt D. Do people reduce compliance with COVID-19 guidelines following vaccination? A longitudinal analysis of matched UK adults. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2022;76(2):109–115. doi: 10.1136/jech-2021-217179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levitt E.E., Gohari M.R., Syan S.K., Belisario K., Gillard J., DeJesus J., et al. Public health guideline compliance and perceived government effectiveness during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada: findings from a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Regional Health - Am. 2022;9 doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2022.100185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morris S.D., Klesner J.L. Corruption and trust: theoretical considerations and evidence from Mexico. Comp Pol Stud. 2010;43(10):1258–1285. doi: 10.1177/0010414010369072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schiff M., Pat-Horenczyk R., Benbenishty R. University students coping with COVID-19 challenges: do they need help? J Am Coll Health. 2022:1–9. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2022.2048838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jennings W., Stoker G., Bunting H., Valgarðsson V.O., Gaskell J., Devine D., et al. Lack of trust, conspiracy beliefs, and social media use predict COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Vaccines. 2021;9(6):593. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9060593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grimmelikhuijsen S., Knies E. Validating a scale for citizen trust in government organizations. Int Rev Adm Sci. 2017;83(3):583–601. doi: 10.1177/0020852315585950. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Evans A.M., Revelle W. Survey and behavioral measurements of interpersonal trust. J Res Pers. 2008;42(6):1585–1593. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2008.07.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ang L., Eisend M. Single versus multiple measurement of attitudes: a meta-analysis of advertising studies validates the single-item measure approach. J Advert Res. 2018;58(2):218–227. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: Data collection flowchart.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.