Abstract

Although the COVID-19 pandemic highly impacted transit ridership as people reduced or stopped travel, these changes occurred at different rates in different regions across the United States. This study explores the impacts of COVID-19 on ridership and recovery trends for all federally funded transit agencies in the United States from January 2020 to June 2022. The findings of this analysis show that overall transit ridership hit a 100-year low in 2020. Changepoint analysis revealed that June 2021 marked the beginning of the recovery for transit ridership in the United States. However, even by June 2022, rail and bus ridership were only about two-thirds of the pre-pandemic levels in most metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs). Only in a handful of MSAs like Tampa and Tucson did rail ridership reach or exceed 2019 ridership. This retrospective study concludes with a discussion of some longer-term changes likely to continue to impact ridership, such as increased telecommuting and operator shortages, as well as some opportunities, such as free fares and increased availability of bus lanes. The findings of this study can help inform agencies about their performance compared to their peers and highlight general challenges facing the transit industry.

Keywords: COVID-19, Transit, Bus, Rail, Ridership, Changepoint, Recovery

1. Background

The COVID-19 pandemic affected humanity in enormous ways. From the declaration of COVID-19 as a pandemic in March 2020 to the final edits on this paper in April 2023, COVID-19 has resulted in more than one million deaths in the United States (CDC, 2023). One highly impacted sector has been public transit, as users stopped or reduced riding transit as they feared contracting COVID-19 on transit, no longer had the need to commute, or shifted their travel mode (Hu et al., 2020, Das et al., 2021, Simons et al., 2021). While transit ridership in the United States was declining prior to the pandemic (Watkins et al., 2021), the impact of COVID-19 on transit ridership was more devastating than any other prior event in the last century. Fig. 1 shows that overall transit ridership and rail ridership hit a 100-year low in 2020, and bus ridership was at the lowest level since the 1930s.

Fig. 1.

Annual transit ridership in the United States

Data Source: American Public Transportation Association (2023).

While some prior studies have considered the impacts of COVID-19 on transit ridership, most focused primarily on the early period of the pandemic for specific agencies/regions. To the best of the authors' knowledge, no prior study did a comprehensive study of transit ridership trends that considers all federally funded transit agencies beyond the first year of the pandemic. Therefore, this study begins to fill this gap in the literature by exploring the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on transit ridership from January 2020 to June 2022 for all federally funded transit agencies in the United States. This retrospective analysis will help transit agencies compare their performance to their peers and understand industry-wide recovery trends.

This paper begins with a brief review of the prior studies. Then, the data and method used to conduct this analysis are presented. Next, the results are presented, and the conclusions and directions forward are discussed.

2. Prior studies

A growing body of knowledge has explored different aspects of how COVID-19 has impacted transit ridership in various regions of the world. This body of knowledge includes numerous international studies, such as recent studies of Australia (Beck et al., 2021), Bangkok, Thailand (Siewwuttanagul and Jittrapirom, 2023), Canada (Palm et al., 2021, Kapatsila et al., 2022), Coruña, Spain (Orro et al., 2020), India (Das et al., 2021), Madrid, Spain(Pozo et al., 2022), Scotland (Downey et al., 2022), Stockholm, Västra Götaland and Skåne, Sweden (Jenelius and Cebecauer, 2020), Tampere, Finland (Tiikkaja and Viri, 2021), and Wuhan, China (Xin et al., 2021).

In the United States, several studies have explored the impact of COVID-19 on transit ridership with a focus on a specific city or a specific state like New York City (Halvorsen et al., 2021, Wang and Noland, 2021, Moghimi et al., 2022), Chicago (Hu and Chen, 2021), Nashville (Wilbur et al., 2020), Chattanooga (Wilbur et al., 2020), Los Angeles (Gleason, 2021), North Dakota (Molina et al., 2021), and Ohio (Simons et al., 2021). However, a limited number of studies have explored the COVID-19 impacts on transit ridership in more than one region of the United States, which is the focus of the following brief literature review.

In one study, Liu et al. 2020 used logistic regression to explore public transit demand changes for 113 transit agencies using data from the Transit app (a widely used smartphone application that provides transit information). This prior study showed higher transit demand was observed in areas with higher percentages of essential workers, minorities, females, and people over 45 (Liu et al., 2020). However, the authors of this study have acknowledged that one limitation is that Transit app data do not represent all riders. They also called for future research to use data from automated passenger counters or other more representative sources.

A study by USDOT on the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the future of transportation explored changes in bus and rail ridership for the top 26 transit markets in the United States from August 2019 to August 2020 using ridership data from the National Transit Database (NTD) (Polzin and Choi, 2021). The findings of this study showed that rail ridership declined by 72% from August 2019 to August 2020, while bus ridership declined by 37% in the same period. This difference in decline was partially attributed to the fact that rail riders typically "travel from white-collar urban and suburban locations to central business district" (Polzin and Choi, 2021). These white-collar jobs were more likely replaced by telecommuting, so the need for travel was negated. While this prior study is very relevant to the topic at hand, it focused on changes during the early months of the pandemic.

Another study by Qi et al. explored ridership changes for bus and light rail in the top 20 largest metropolitan areas in the United States from February 2020 to January 2021 (Qi et al., 2021). Using random-effects models, Qi et al. showed that areas with higher median household incomes, higher employment rates, and higher Asian populations experienced higher ridership declines (Qi et al., 2021). Similarly, a study by Sullivan explored the COVID-19 impacts on transit ridership in New England using NTD ridership data. This prior study found that 11 of the 12 transit agencies in the region experienced more than a 50% decline in ridership in the first year of the pandemic (Sullivan, 2021). These studies also focused on the first year of the pandemic, leaving room for additional research on nationwide trends in the later stages of the pandemic.

While these prior studies on the impacts of COVID-19 on ridership in the first year of the pandemic are interesting, the transit industry in the United States now faces the question of how it can fully rebound as the major public health threat of the pandemic subsides. Therefore, continued analysis of the impact of COVID-19 on transit ridership is needed. This study explores transit ridership trends for all federally funded transit agencies that report to the National Transit Database in the United States from January 2020 to June 2022, which is an area for research suggested in prior studies (Qi et al., 2021, Liu et al., 2020). This study makes three contributions. This study examines transit ridership trends during the early portion of the pandemic as well as more recent recovery trends (until June 2022) using a changepoint analysis to investigate transit ridership's recovery trajectory. This changepoint analysis detects any significant changes in the recovery of transit ridership. In addition, this study explores ridership changes in operational clusters across the United States, allowing transit providers to compare their performance to their peers.

3. Data

This study used monthly ridership data from the National Transit Database from January 2019 to June 2022 (National Transit Database, 2022). NTD data provides monthly ridership estimates by mode for all transit agencies that receive federal funds. For this analysis, only rail and bus were considered since they are the dominant modes in the United States. The rail mode included heavy rail (HR), light rail (LR), streetcars (SR), and commuter rail (CR), and the bus mode contained motor bus (MB), bus rapid transit (RB), trolley bus (TB), and commuter bus (CB). It should be noted that demand-responsive transit was not considered in this study; future studies should explore demand-responsive transit and how it was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The unit of analysis was the metropolitan statistical area (MSA); all transit agencies operating in the same region were aggregated to the MSA level. The reason for using the MSA level instead of the transit agency was to compare regions with similar transit characteristics based on American Public Transportation Association (APTA) operational expenses clusters (American Public Transportation Association, 2019):

-

•

High operational expenses cluster: Above $300 Million per year. This cluster had both bus and rail operators.

-

•

Mid operational expenses cluster: Between $30 Million and $300 Million per year. This cluster also had bus and rail operators.

-

•

Low operational expenses cluster: Below $30 Million per year. This cluster had bus operators only.

The New York MSA, which includes transit agencies operating in New York State and New Jersey, was explored separately since this region carries about 40% of the total transit ridership in the United States (Watkins et al., 2021). Also, New York was a COVID-19 hotspot in the early months of the pandemic, which also warrants special consideration.

4. Method

This study begins with a retrospective analysis of ridership, service provision, and productivity changes using APTA operational expense clusters from January 2020 to June 2022. By comparing trends across regions within each cluster, this retrospective analysis provides an overview of how transit ridership changed in the different MSAs and allows transit providers to compare their performance to their peers.

The second part of the study applied a changepoint analysis to detect any significant changes in the recovery of transit ridership. Changepoints are defined as "abrupt variations in time series data" and could represent changes that occur between conditions or states (Aminikhanghahi and Cook, 2017). Changepoint analysis is gaining interest in the field of transportation in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic; some recent studies have used this method to explore changes in mobility levels and subway ridership during COVID-19 (Panik et al., 2022, Moghimi et al., 2022). Changepoint analysis was applied to identify changes in ridership recovery measured as the percent decline compared to the same month in 2019. Transit ridership recovery might have experienced more than one change during the study period; therefore, this study used the multiple changepoint approach. This study applied a detection method proposed by Killick and Eckley to explore the multiple changepoints (Killick and Eckley, 2014). The method uses multiple search methods compared to other methods that apply single search methods (Killick and Eckley, 2014).

The Killick and Eckley method applies a likelihood-based framework to detect changepoints (Killick and Eckley, 2014). The multiple changepoint method is an extension of the single changepoint approach that uses a likelihood ratio test statistic for changes in the mean and/or variance of the outcome variable (y) before and after the changepoint. The likelihood ratio test has a null hypothesis indicating no changepoint (m = 0), and an alternative hypothesis that there is a single changepoint (m = 1) (Killick and Eckley, 2014). The multiple changepoint approach uses the same concept to test for m> 1 by summing the likelihood for each m (Killick and Eckley, 2014).

The multiple changepoint approach identifies the multiple changepoints by minimizing Eq. (1) (Killick and Eckley, 2014).

| (1) |

Where:

y is the outcome variable.,

C is the cost function (e.g., negative log-likelihood).

is a penalty to guard against overfitting.

m is the number of changepoints.

is a changepoint at the time i.

Killick and Eckley proposed three different algorithms to minimize Eq. (1) as follows: binary segmentation, segment neighborhoods, and pruned exact linear time (PELT) (Killick and Eckley, 2014).

This study used the pruned exact linear time (PELT) algorithm to detect multiple changepoints in the mean of the percent decline in monthly ridership compared to 2019, since it is the most accurate and computationally efficient (Killick and Eckley, 2014). Also, to protect against overfitting, a penalty = 200 *log(n) was applied, and the minimum length of the segment was restricted to two months. This analysis was carried out in RStudio using the "changepoint" package version 2.2.3 (Killick et al., 2022).

5. Results

This section presents ridership, service provision, and productivity trends from January 2020 to June 2022 for both rail and bus.

5.1. Rail trends

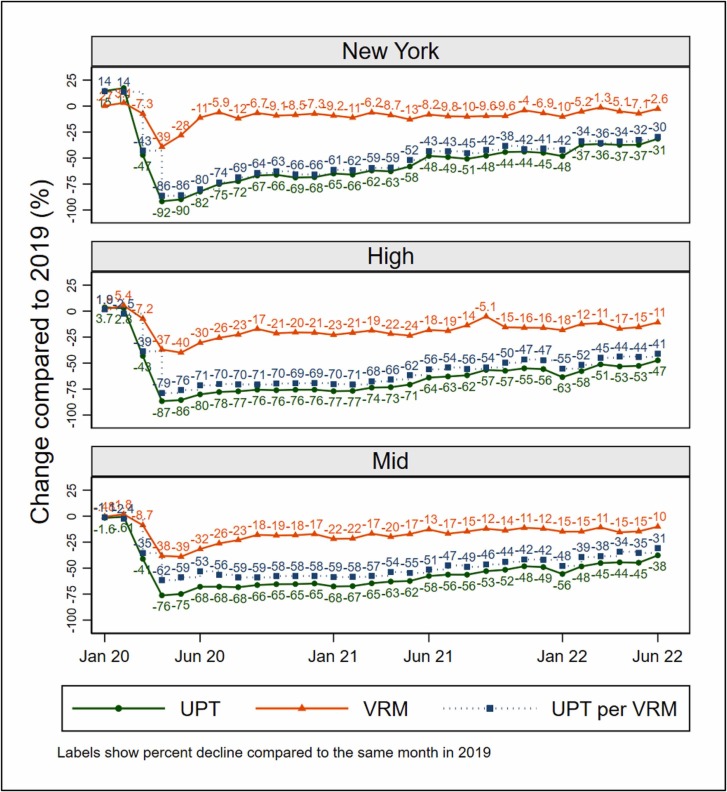

Fig. 2 shows the percentage change compared the same month in 2019 for New York, the high operational expenses cluster, and the mid operational expenses cluster. New York experienced substantial drops early in the pandemic; ridership dropped by more than 90% in April 2020 and May 2020 compared to 2019. These dramatic drops coincided with a significant service reduction of 39% of vehicle revenue miles (VRM) in April 2020. However, as New York announced a phased reopening plan in June and July 2020 (Wang and Noland, 2021), 90% of the rail service was restored by July 2020, and ridership started to bounce back slightly. New York ridership recovered slowly in 2021 and the first half of 2022 until it reached about 70% of 2019 by June 2022. This generally aligns with the findings of a prior study that predicted transit ridership in New York would be about 73% of the pre-pandemic levels after the city reopened (Wang et al., 2021).

Fig. 2.

Percent decline in ridership, service provision, and productivity for rail.

Fig. 2 also shows that rail ridership in the high operational expenses cluster experienced similar ridership declines to New York in April and May 2020 (about an 87% decline in UPT). However, rail ridership in these MSAs experienced a slower recovery than in New York. By June 2022, they were still 47% below ridership levels in 2019, although the service levels were only 11% below 2019.

In the mid operational expenses cluster shown in Fig. 2, ridership declines were less dramatic during the early period of the pandemic; the largest decline was 76% of 2019 ridership levels in April 2020. However, ridership was almost constant from July to December 2020 at about a third of 2019 levels. From the beginning of 2021, ridership started a slow recovery until it reached about 60% of the 2019 levels by June 2022.

Comparing ridership for these three clusters, ridership recovery was slower for the high operational expenses cluster. This slower recovery suggests that transit agencies in this cluster may have a tough time bringing rail ridership back to the pre-pandemic levels; it may be particularly challenging for those agencies with higher numbers of choice riders and high-income riders, as a prior study showed that high-income riders used transit less than low-income riders during the pandemic (Parker et al., 2021). Those riders might be reluctant to return to transit as they have access to other options. Also, areas with higher levels of white-collar jobs may struggle to recover as white-collar workers may continue to work from home (Kurzhanskiy and Lapardhaja, 2021).

In addition, Fig. 2 shows that service levels measured as vehicle revenue miles (VRM) in New York were almost restored to pre-pandemic service provision levels by June 2022, and VRM was only about 10% less than 2019 levels for the high and mid operational expenses clusters. By this point, rail service was almost at the pre-pandemic levels across the different clusters.

Last, Fig. 2 displays transit productivity (measured as UPT per VRM and shown in blue). Transit productivity followed a similar trajectory ridership for the different clusters.

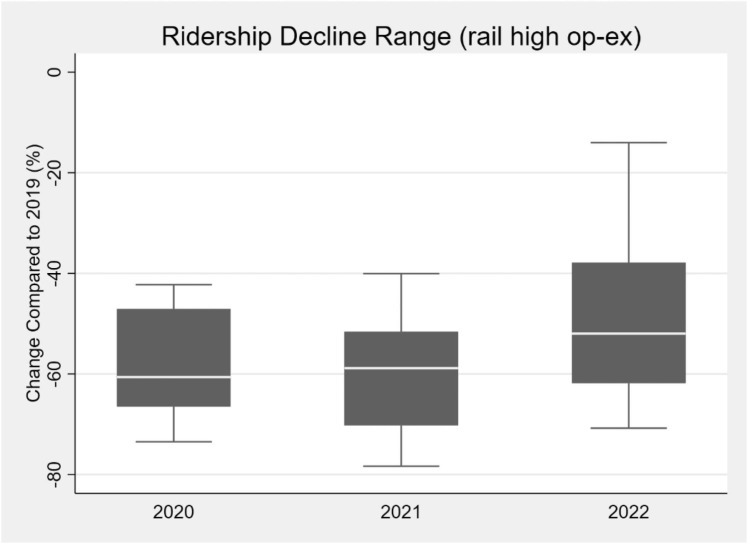

5.1.1. Rail ridership changes by region in the high operational expenses cluster

Fig. 3 shows declines in rail ridership for 2020, 2021, and 2022 (Jan to Jun only) compared to similar periods in 2019, measured as a percent decline relative to 2019. The change in ridership in June 2022 compared to June 2019 for each MSA is represented by the circle's color and size.

Fig. 3.

Rail ridership declines for New York, and the high operational expenses cluster MSAs.

Fig. 3 shows that San Francisco and Washington, DC were the most affected MSAs in this cluster; they experienced ridership declines of 73% and 71% in 2020, respectively. This finding is consistent with the findings of a prior study by (Qi et al., 2021). One possible reason that may explain these sharp declines is telecommuting. Washington, DC, had substantially declined ridership as most federal government employees worked virtually during 2020. Data from the Maryland Transportation Institute at the University of Maryland College Park showed that between March 2020 and December 2020, about 52% of the workforce in Washington, DC worked from home, the highest nationwide during this period (Maryland Transportation Institute, 2020). Similarly, San Francisco and the larger Bay Area metropolitan region are home to many tech companies whose employees could work remotely for extended periods. In contrast, Houston, Dallas, Phoenix, and San Diego were the least affected in 2020 in percentage terms; they experienced ridership declines ranging from 42% to 44%.

In 2021, ridership declines in this cluster ranged from 40% to 78% ( Fig. 4). San Jose joined San Francisco and Washington, DC, as the most affected MSAs. Ridership declines in these three MSAs ranged from 78% to 76% below the 2019 levels. This high ridership decline in San Jose could be attributed to the system being out of service for three months due to a mass shooting in one of the light rail stations in May 2021 (Preciado et al., 2021). San Diego, Dallas, Miami, and Houston were the least affected in 2021.

Fig. 4.

Rail ridership declines range for the high operational expenses cluster.

Fig. 3 also shows that in June 2022, MSAs in this cluster experienced ridership declines ranging from 9% to 67%, with a mean decline of 43%. San Diego experienced the least decline as ridership was only 9% below June 2019, which indicates that it had almost recovered. On the other hand, ridership in Baltimore was still 67% below June 2019 levels (the highest in this cluster). San Francisco, Washington, DC, San Jose, and Chicago were also among the most affected. Recent research has shown that downtown San Francisco continues to feel the impacts of the pandemic, and it had the lowest recovery ratio among 31 large cities with populations of more than 350,000 across the United States and Canada (Chapple et al., 2022). Chapple et al. 2022 showed that visits to downtown San Francisco in the period March 2022 to May 2022 were only 31% of the number of visits in 2019 for the same period (Chapple et al., 2022). Similarly, Chicago ridership was 52% less in June 2022 than in June 2019, which suggests that ridership in Chicago had yet to recover as of 2022. This finding contradicts the prediction of a prior study in Chicago that expected ridership would recover immediately as all travel restrictions were lifted (Osorio et al., 2022). A recent report suggested that ridership recovery in Chicago has been affected by remote work policies rather than travel restrictions (Liu et al., 2023).

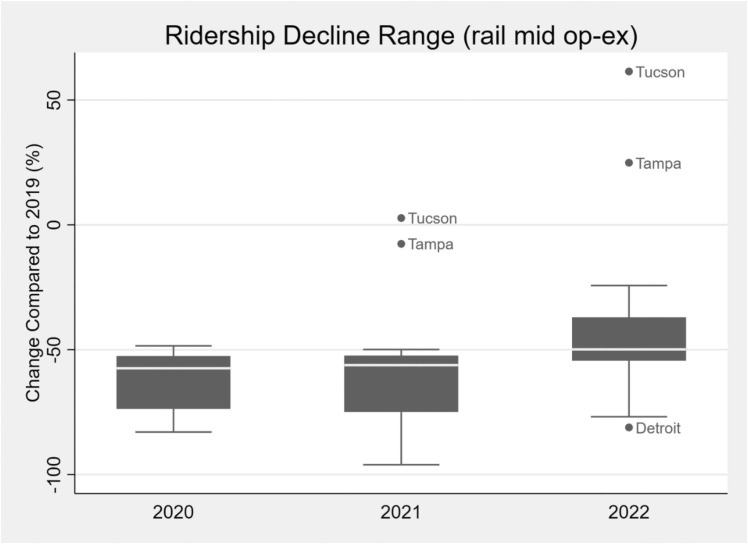

5.1.2. Rail ridership changes by region in the mid-operational expenses cluster

Fig. 5 shows that St. Louis experienced a 48% drop in ridership in 2020, which is the smallest in this cluster, followed by Sacramento (50% drop in 2020). Fig. 5 also shows that the most impacted MSAs in terms of percentages were Albuquerque, Detroit, El Paso, Portland (ME), Nashville, and Stockton; these MSAs experienced ridership declines ranging between 83% and 73% in 2020. Those MSAs could be divided into two groups. The first group contains Albuquerque, Detroit, and El Paso. These three MSAs shut down their transit service in April 2020. The second group contains Portland (ME), Nashville, and Stockton, which operate only commuter rail. These three MSAs with commuter rail only experienced higher declines than other MSAs in this cluster, which is expected as telecommuting was one of the main strategies used to reduce the spread of COVID-19, and many commuter rail patrons have higher-income jobs that are more likely to allow work from home (Polzin and Choi, 2021).

Fig. 5.

Rail ridership declines in the mid-operational expenses cluster MSAs.

In 2021, interestingly, rail ridership in Tucson exceeded 2019 ridership levels by 3%, which is the first MSA to reach pre-pandemic rail ridership levels ( Fig. 6). Transit officials in Tucson attribute this recovery to the continuation of offering free rides, waiving the $4.25 single fare on the streetcar system (Koldnews, 2022). In the first half of 2022, Tampa joined Tucson as the only two MSAs to exceed 2019 ridership with 25% and 61% increases, respectively. Officials in Tampa attribute this increase in ridership to increased tourism and major events like the Tampa Bay Lightning playoff (Spectrum Bay News 9, 2022). Also, the Tampa streetcar has been running free since October 2018 (Harlan, 2022). Last, Detroit, El Paso, Nashville, and Stockton were also the most affected MSAs in 2021 and the first half of 2022.

Fig. 6.

Rail ridership declines range for the mid operational expenses cluster.

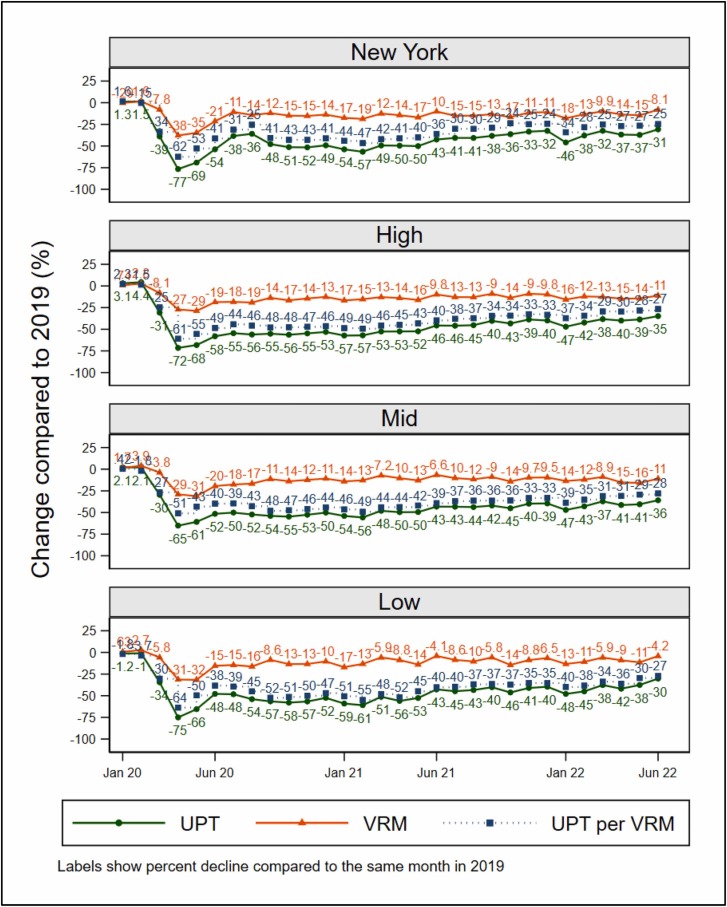

5.2. Bus trends

Fig. 7 shows that the largest decline in bus ridership in the New York MSA was observed in April 2020, with a 77% drop compared to April 2019. New York bus ridership reached two-thirds of 2019 levels in August 2020 before dropping again in the following months; this second decline could be attributed to the increase in COVID-19 cases during this period. COVID-19 cases in New York were again on the rise during the period from October 2020 to December 2020 (CDC, 2023). By June 2022, New York bus ridership was about two-thirds of ridership levels observed in 2019.

Fig. 7.

Percent decline in ridership, service provision, and productivity for bus.

Fig. 6 shows that bus ridership in the other operational expense clusters (High, Mid, and Low) followed a similar trend. Bus ridership in these three clusters experienced the largest decline in April 2020, about 70%, compared to April 2019. After that, ridership started a slow recovery until it reached about two-thirds of 2019 ridership levels by June 2022. However, bus ridership in the different clusters dipped during surges in COVID-19 cases in January 2021 (Alpha variant) and January 2022 (Omicron variant) (CDC, 2023). This finding suggests that bus ridership was still affected by COVID-19 waves but at a smaller magnitude compared to when the pandemic first hit.

Fig. 7 also shows the service provision levels for the different clusters. All clusters reduced bus service by about 30% in April and May 2020. New York, mid, and low operational expenses clusters restored about 90% of service by fall 2020. On the other hand, the high operational expenses cluster VRM levels were about 80–85% of the 2019 levels through June 2021. Fig. 7 also shows that productivity followed a similar trend to ridership.

Comparing bus and rail trends, bus ridership experienced less decline than rail at the beginning of the pandemic and started to recover faster. This difference may be partly due to the demographics of bus riders compared to rail; essential workers more often use buses than rail, and rail systems often have higher percentages of choice riders than buses before and during the pandemic (Clark, 2017, Taylor and Morris, 2015, Brown et al., 2014, He et al., 2022). Last, the results of this study indicate that rail and bus ridership experienced ridership declines of about 30% in June 2022. This finding suggests that ridership is still below some of the early recovery predictions that projected ridership declines will be less than 20% by June 2022 (Polzin and Choi, 2021).

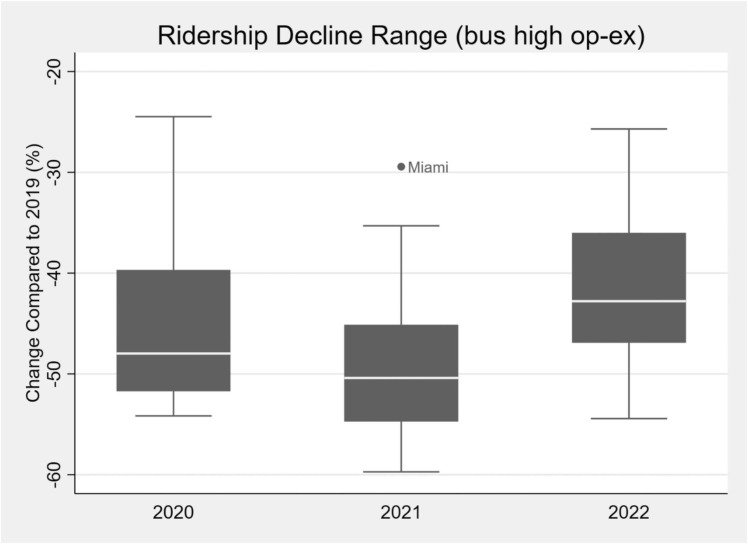

5.2.1. Bus ridership changes by region in the high operational expenses cluster

Fig. 8 shows declines in bus ridership compared to 2019 for MSAs in the high operational expenses cluster for 2020, 2021, and the first half of 2022. In 2020, MSAs in this cluster experienced a similar percentage drop in bus ridership, ranging from 36% to 54% (mean decline of 46%), except for Phoenix, which experienced a drop of only 24%. In 2021, most MSAs experienced larger percentages of decline compared to 2020, ranging from 29% to 60% ( Fig. 9). These larger declines were likely because COVID-19 affected ridership in 2020 starting from March, while it affected the whole year of 2021. Boston, Miami, Los Angeles, and Washington, DC, debunked this trend as they experienced smaller declines in 2021 compared to 2020, suggesting they started to recover faster than other MSAs.

Fig. 8.

Bus ridership declines in the high operational expenses cluster MSAs.

Fig. 9.

Bus ridership declines range for the high operational expenses cluster.

In the first half of 2022, most MSAs' ridership reached more than half the 2019 levels, with Miami being the fastest to recover (74% of 2019 ridership levels).

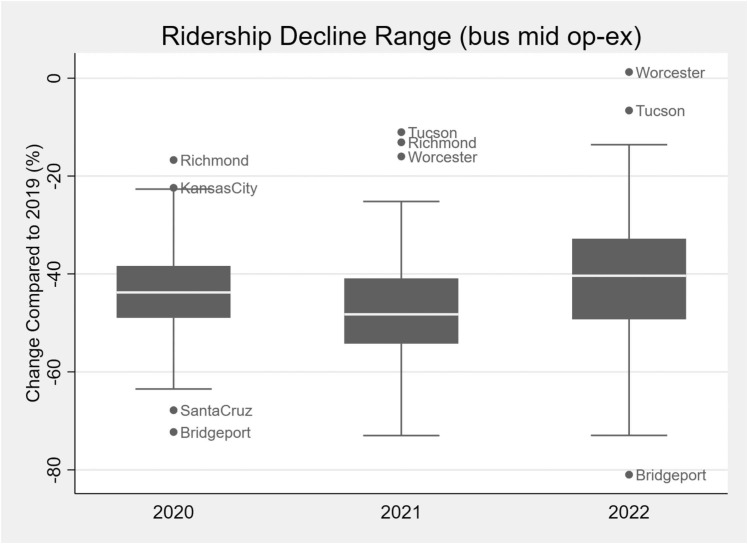

5.2.2. Bus ridership changes by region in the mid operational expenses cluster

In 2020, this cluster's mean decline in ridership was 44%. Richmond, VA, was the least affected, with a decline of only about 17% in 2020, as shown in Fig. 10 and Fig. 11. Bridgeport, CT, was the most affected in the mid operational expenses cluster (−73%), followed by Santa Cruz-Watsonville, CA (−68%) (Fig. 11). In 2021, Tucson, AZ, and Richmond, VA, experienced only 11% and 13% less than the 2019 levels, respectively, which were the least percentages of decline in ridership in this cluster. Bridgeport, CT (−73%) and Santa Cruz-Watsonville, CA (−68%) were also the most affected. In the first half of 2022, bus ridership in Worcester, MA-CT, recovered to the pre-pandemic levels, with ridership gains also attributed to the agency operating fare-free since the beginning of the pandemic (Milneil, 2021). In June 2022, ridership in Worcester, MA-CT, was about 25% higher than in June 2019, which indicates that ridership continued to increase.

Fig. 10.

Bus ridership decline in the mid operational expenses cluster MSAs.

Fig. 11.

Bus ridership declines range for the mid operational expenses cluster.

5.2.3. Bus ridership changes by region in the low operational expenses cluster

Fig. 12 shows that declines in the low operational expenses cluster ranged from − 93% to − 42%, with a mean decline of 42%. Rome, GA, was the most impacted in this cluster in 2020 (−93% drop in ridership), followed by Elizabethtown, KY (−80%), Bay City, MI (−74%), State College, PA (−70%), Blacksburg, VA (−69%), and Ithaca, NY (−66%). Many of these cities are college towns where students moved to eLearning when the COVID-19 pandemic began. Elizabethtown, KY, stopped fixed-route bus services when the pandemic hit.

Fig. 12.

Bus ridership declines in the low operational expenses cluster MSAs.

In 2021, ridership declines ranged from 7% to 93% below 2019 levels ( Fig. 13), with a mean decline of 45%. Sebastian, FL, experienced the fastest recovery as ridership was only about 7% below 2019. One interesting aspect of transit in Sebastian, FL, is that GoLine (the transit provider) operates fare-free but encourages riders to donate to help the system (Goline, 2022).

Fig. 13.

Bus ridership declines range for the low operational expenses cluster.

In the first half of 2022, Toledo experienced a 19% increase in ridership compared to the same period in 2019; the transit agency in Toledo was operating fare-free from March 2020 till July 2022 but reinstated fares starting August 2022 (Toledo Area Regional Transit Authority (Toledo Area Regional Transit Authority Tarta, 2022). Figs. 12 and 13 also show that ridership in Fayetteville, NC, experienced a ridership increase of more than 20% in the first half of 2022. These increases likely resulted from low ridership in the first half of 2019 in Fayetteville, NC, not a large increase in 2022.

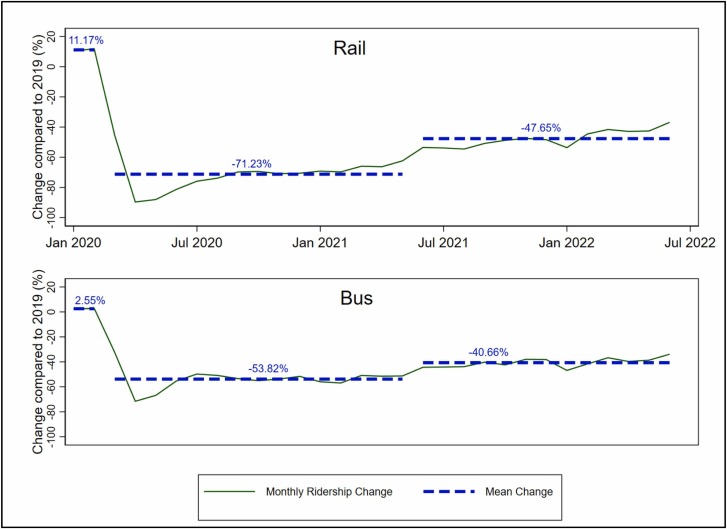

5.3. Changepoint analysis

Fig. 14 shows the changepoint results of nationwide rail and bus ridership compared to 2019. Rail and bus ridership change had two changepoints within the study period, in March 2020 and June 2021. The first changepoint in March 2020 identifies the beginning of the pandemic with substantial ridership declines until May 2021. During this period, the average monthly ridership decline was about 71.23% on rail and 53.82% on bus. Stay-at-home orders and higher unemployment rates defined this period. This finding aligns with the findings of prior studies in different regions (Moghimi et al., 2022, Osorio et al., 2022). The other changepoint in June 2021 signals the beginning of the recovery for transit ridership. The beginning of the recovery corresponds with 50% of US adults being fully vaccinated by the end of May 2021 (CDC, 2023). From June 2021 to June 2022, rail ridership was 47.65% lower than 2019 levels, while bus ridership was about 40.66% less than in 2019. These two numbers indicate 23.58% and 13.16% points increase in rail and bus ridership, respectively. These increases are consistent with the findings of a nationwide survey of transit riders (n = 531) that found effective vaccines would encourage 38% of riders to increase transit use (Parker et al., 2021).

Fig. 14.

Changepoint results of nationwide rail and bus ridership.

In summary, this analysis shows that early in the pandemic, buses experienced fewer declines compared to rail, likely due to the fact that buses typically serve more essential workers and transit-dependent riders compared to rail (Clark, 2017). However, after the changepoint, rail ridership recovered a higher portion of lost ridership compared to the bus.

This changepoint analysis was also conducted by cluster; the results are shown in Table 1. In all clusters but rail mid operational expenses, ridership recovery followed the same trend as nationwide ridership with two changepoints in March 2020 and June 2021. The rail mid operational expenses cluster's second changepoint was in July 2021, suggesting ridership in this cluster started to recover one month later but within a similar timeframe. Interestingly, the COVID-19 pandemic hit when ridership across all clusters was increasing except the bus low operational expenses cluster and the rail mid operational expenses cluster (Table 1). These increases came after years of decline in transit ridership since 2014 (Erhardt et al., 2022, Watkins et al., 2021). However, as the pandemic hit, ridership experienced the most severe declines in the last 100 years.

Table 1.

Changepoint Results by Cluster.

| Cluster | # of CP | Time of CPs |

Mean ridership change compared to 2019 (%) |

Difference between (3) and (2) (pp) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Jan 20 to Feb 20 | (2) Mar 20 to May 21 | (3) Jun 21 to Jul 22 | |||||

| Bus (US) | 2 | March 2020 | June 2021 | 2.55 | -53.82 | -40.66 | 13.16 |

| Bus NY | 1.36 | -51.48 | -37.33 | 14.15 | |||

| Bus High | 3.72 | -55.38 | -41.56 | 13.82 | |||

| Bus Mid | 2.08 | -51.86 | -41.66 | 10.20 | |||

| Bus Low | -1.10 | -55.24 | -41.41 | 13.82 | |||

| Rail (US) | 11.17 | -71.23 | -47.65 | 23.58 | |||

| Rail NY | 15.94 | -69.45 | -42.81 | 26.64 | |||

| Rail High | 3.23 | -74.95 | -56.84 | 18.11 | |||

| Rail Mid | 2 | March 2020 | July 2021 | -1.09 | -65.02 | -49.17 | 15.85 |

Table 1 also shows the difference in average ridership decline between the two periods before and after the second changepoint. The recovered portion of ridership ranged from 10% in the bus mid operational expenses cluster to 26% in the rail New York cluster.

6. Conclusions

This retrospective study explored transit ridership, service provision, and productivity changes for all federally funded agencies in the United States due to the COVID-19 pandemic from January 2020 to June 2022. Overall transit ridership and rail ridership hit 100-year lows in 2020, and bus ridership reached the lowest level since the 1930s. Most metropolitan areas and modes experienced the highest drop in April 2020, when there were many lockdowns and travel restrictions. Riders started to return to transit as cities began to reopen, but ridership declines were still substantial in most MSAs through June 2021. This significant changepoint in the recovery trajectory in June 2021 is likely attributed to 50% of US adults being fully vaccinated and messaging from officials that the pandemic was ending. From June 2021 to June 2022, ridership recovery continued but slowly until it reached about two-thirds of the 2019 levels in most MSAs.

In a handful of MSAs like Tampa and Tucson, rail ridership reached or exceeded 2019 ridership. Bus ridership also exceeded 2019 ridership in some MSAs in the low operational expenses cluster. One common factor among many of these MSAs that recovered is continuing to offer fare-free transit for an extended period. While this finding suggests that fare free operations expedited ridership recovery in some MSAs, further research is needed to confirm this finding and to estimate the magnitude of the impact.

Last, transit productivity (measured as UPT per VRM) followed the same trend as ridership across different modes across all clusters. This finding indicates that the capacity limits implemented by agencies did not greatly impact ridership.

7. Directions forward

The findings of this study showed that though transit ridership in the United States has recovered slowly, it was still about one-third below the 2019 levels by June 2022, while other modes of travel, like vehicular travel, had already reached pre-pandemic levels Bureau of Transportation Statistics, 2022). As the transit industry works to regain ridership to pre-pandemic levels, some additional factors may impact continued recovery. Service cuts due to bus operator shortages are a major concern. 71% of agencies that participated in a recent survey by APTA (n = 117) stated that they had to cut service or delay service increases because of the bus operators' shortage (American Public Transportation Association, 2022). This shortage could be attributed to factors like competition from delivery companies, general low unemployment, and reports of increased assaults against transit operators, along with increases in crime in many cities (TransitCenter, 2022,, Walker, 2021). Transit providers must address this driver shortage issue as a major step toward full recovery.

Another threat to the recovery is the projected fiscal cliff at many transit agencies, as federal funding is expected to end soon (TransitCenter, 2023). Agencies benefited from the additional federal funding provided through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act (Congress.Gov., 2020a, Congress.Gov., 2020b), the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act of 2021 (Congress.Gov., 2020a, Congress.Gov., 2020b), and the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (Congress.Gov, 2021) to overcome the loss of revenue resulting from fare collection suspension. As this funding source is drying up, agencies face severe deficits in their budget (TransitCenter, 2023).

Furthermore, many of the MSAs that reached or exceeded pre-pandemic ridership levels operated fare-free services for extended periods, which suggests that it could play a role in transit recovery. However, the fare-free operation could be costly, particularly for agencies with higher farebox recovery ratios. In the future, transit providers need other sources of revenue to replace the farebox revenue if they decide to continue fare-free operations.

Telecommuting is expected to be a long-lasting impact of the COVID-19 pandemic; a survey of more than 30,000 Americans indicated that the percentage of telecommuting is expected to be 20% after COVID-19 compared to only 5% prior to the pandemic (Barrero et al., 2021). This significant increase in telecommuting is expected to change how people use transit either by reducing the frequency of riding or the purpose of using transit. Transit providers should consider this as they plan for future service changes. For example, agencies could change their fare policy to encourage part-time commuters to use transit when they commute through programs such as fare capping with flexible periods (Hightower et al., 2022) or short-term period passes instead of 31-day passes. Also, agencies could consider planning services for more diverse travel purposes rather than focusing on commuting.

A related challenge to telecommuting is that many people have moved to less dense areas to avoid crowding or benefit from large areas for outdoor activities (Burke and Grogan, 2021). Lower densities would negatively affect transit ridership (Watkins et al., 2021), and more transit services would be needed to provide the same level of accessibility.

The COVID-19 pandemic also resulted in many changes to transit planning and operations (Gkiotsalitis and Cats, 2021). Some of these changes were implemented primarily in the early stages of the pandemic, like social distancing and masks on vehicles, changes to frequencies and timetables, and capacity limits (Federal Transit Administration, 2022, Gkiotsalitis and Cats, 2021). Other changes could remain in the longer term. One example is providing real-time tools to track crowding on vehicles (Federal Transit Administration, 2022); while this was particularly useful for social distancing purposes, it is also helpful as ridership grows. Real-time crowding information could be used to improve riders' satisfaction, reduce overcrowding, and help reduce bus bunching (Drabicki et al., 2022, Drabicki et al., 2023). Another modification was the installation of temporary bus lanes during the pandemic in cities like Boston, Chicago, and San Francisco (Cobbs, 2020). These temporary lanes helped to increase the speed of buses; for example, one evaluation of a temporary bus lane installed along a high ridership corridor in San Francisco showed that riders experienced 15% faster travel times (Mcmillan, 2022). The success of temporary bus lanes shows that prioritizing transit by providing increased levels of right-of-way could be done relatively quickly and at a low cost.

Last, while this study focused on ridership (the typical measure for transit performance), the COVID-19 pandemic showed that transit plays a critical equity role in providing access to essential workers around the country who helped keep the cities running. This kind of benefit could not be quantified by ridership or productivity. Therefore, in the future, transit success should not be measured only by ridership or productivity measures; other measures are needed to gauge transit performance.

Funding information

Funding: This work was supported by the Transit-Serving Communities Optimally, Responsively, and Efficiently (TSCORE) University Transportation Center Grant No. 69A3552047141 with matching funds from the Tennessee Department of Transportation (TDOT RES2021–15) and the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- American Public Transportation Association, 2019, City Clustering Methodology proposed by APTA.

- American Public Transportation Association, 2022, Workforce Shortages Impacting Public Transportation Recovery.

- American Public Transportation Association, 2023, Ridership Report Archives [Online]. Available: 〈https://www.apta.com/research-technical-resources/transit-statistics/ridership-report/ridership-report-archives/〉 [Accessed May 9, 2023].

- Aminikhanghahi S., Cook D.J. A survey of methods for time series change point detection. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2017;51:339–367. doi: 10.1007/s10115-016-0987-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrero J.M., Bloom N., Davis S.J. National Bureau of Economic Research,; 2021. Why Working from Home Will Stick. [Google Scholar]

- Beck M.J., Hensher D.A., Nelson J.D. Public transport trends in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic: An investigation of the influence of bio-security concerns on trip behaviour. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021;96 doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2021.103167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J., Thompson G., Bhattacharya T., Jaroszynski M. Vol. 51. 2014. Understanding transit ridership demand for the multidestination, multimodal transit network in Atlanta, Georgia: Lessons for increasing rail transit choice ridership while maintaining transit dependent bus ridership; pp. 938–958. (Urban studies). [Google Scholar]

- Bureau Of Transportation Statistics, 2022, Latest Weekly COVID-19 Transportation Statistics [Online]. @USDOT. Available: 〈https://www.bts.gov/covid-19/week-in-transportation〉 [Accessed September 8, 2022].

- Burke, T. & Grogan, T., 2021, Where Did People Relocate During 2020? [Online]. Available: 〈https://www.streetlightdata.com/where-did-people-relocate-during-2020/?type=blog/〉 [Accessed December 10, 2021].

- Chapple, K., Leong, M., Huang, D., Moore, H., Schmahmann, L. & Wang, J., 2022, The death of downtown? Pandemic recovery trajectories across 62 North American Cities.

- Clark H.M. Who rides public transportation. Am. Public Transp. Assoc. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- Cobbs, C., 2020, How have pandemic bus lanes worked out in Chicago, Boston, and SF? [Online]. Available: 〈https://chi.streetsblog.org/2020/12/03/how-have-pandemic-bus-lanes-worked-out-in-chicago-boston-and-sf/〉 [Accessed November 15, 2021].

- Congress.Gov. December 27, 2020a. Text - H.R.133 - 116th Congress (2019–2020): Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/133/text. [Accessed].

- Congress.Gov. March 11, 2021. Text - H.R.1319 - 117th Congress (2021–2022): American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 [Online]. Available: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/1319/text. [Accessed].

- Congress.Gov. March 27, 2020b. H.R.748 - 116th Congress (2019–2020): CARES Act [Online]. Available: https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/748. [Accessed].

- Das S., Boruah A., Banerjee A., Raoniar R., Nama S., Maurya A.K. Impact of COVID-19: A radical modal shift from public to private transport mode. Transp. Policy. 2021;109:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2021.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey L., Fonzone A., Fountas G., Semple T. The impact of COVID-19 on future public transport use in Scotland. Transp. Res. Part A: Policy Pract. 2022;163:338–352. doi: 10.1016/j.tra.2022.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabicki A., Cats O., Kucharski R., Fonzone A., Szarata A. Should I stay or should I board? Willingness to wait with real-time crowding information in urban public transport. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2023 [Google Scholar]

- Drabicki A., Kucharski R., Cats O. Mitigating bus bunching with real-time crowding information. Transportation. 2022:1–28. doi: 10.1007/s11116-022-10270-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erhardt G.D., Hoque J.M., Goyal V., Berrebi S., Brakewood C., Watkins K.E. Why has public transit ridership declined in the United States? Transp. Res. Part A: Policy Pract. 2022;161:68–87. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Transit Administration 2022. COVID-19 Recovery Practices in Transit. In: DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION (ed.).

- Gkiotsalitis K., Cats O. Public transport planning adaption under the COVID-19 pandemic crisis: literature review of research needs and directions. Transp. Rev. 2021;41:374–392. [Google Scholar]

- Gleason, Q., 2021, THE EFFECTS OF COVID-19 ON LOS ANGELES METRO BUS RIDERSHIP. California State Polytechnic University, Pomona.

- Goline, 2022, Riding GoLine [Online]. Available: 〈http://www.golineirt.com/info.html〉 [Accessed September 7, 2022].

- Halvorsen A., Wood D., Jefferson D., Stasko T., Hui J., Reddy A. Examination of New York City Transit’s Bus and Subway Ridership Trends During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Transp. Res. Rec. 2021 doi: 10.1177/03611981211028860. 03611981211028860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlan, A., 2022, Tampa Streetcar on track to surpass one million riders in 2022 [Online]. @thatssotampa. Available: 〈https://thatssotampa.com/tampa-streetcar-ridership-2022/〉 [Accessed Sep 7, 2022].

- He Q., Rowangould D., Karner A., Palm M., Larue S. Covid-19 pandemic impacts on essential transit riders: findings from a US Survey. Transp. Res. Part D: Transp. Environ. 2022;105 doi: 10.1016/j.trd.2022.103217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hightower A., Ziedan A., Crossland C., Brakewood C. Current Practices and Potential Rider Benefits of Fare Capping Policies in the USA. Transp. Res. Rec. 2022 03611981221089572. [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Barbour W., Samaranayake S., Work D. Impacts of Covid-19 mode shift on road traffic. arXiv Prepr. arXiv. 2020;2005:01610. [Google Scholar]

- Hu S., Chen P. Who left riding transit? Examining socioeconomic disparities in the impact of COVID-19 on ridership. Transp. Res. Part D: Transp. Environ. 2021;90 [Google Scholar]

- Jenelius E., Cebecauer M. Impacts of COVID-19 on public transport ridership in Sweden: Analysis of ticket validations, sales and passenger counts. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020;8 doi: 10.1016/j.trip.2020.100242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapatsila B., Grisé E., Van Lierop D., Bahamonde-Birke F.J. From Riding to Driving: the Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Public Transit in Metro Vancouver. Findings. 2022:33884. [Google Scholar]

- Killick R., Eckley I. changepoint: An R package for changepoint analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2014;58:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Killick R., Haynes K. & Eckley I. 2022. _changepoint: An R package for changepoint analysis_. R package version 2.2.3, [Online]. Available:<https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=changepoint>. [Accessed].

- Koldnews 2022. Sun Link streetcar experiencing record ridership after fare lifted because of COVID-19 pandemic. In: CURRIER, C. (ed.). @KOLDNews.

- Kurzhanskiy, A. & Lapardhaja, S. 2021. Bus Operations of Three San Francisco Bay Area Transit Agencies during the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic.

- Liu L., Miller H.J., Scheff J. The impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on public transit demand in the United States. Plos One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0242476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Osorio J., Ouyang Y. Quantifying Impacts COVID. 2023:19. [Google Scholar]

- Maryland Transportation Institute, 2020, University of Maryland COVID-19 Impact Analysis Platform, [Online]. University of Maryland, College Park, USA. Available: 〈https://data.covid.umd.edu〉 [Accessed September 10,2022].

- Mcmillan, E. 2022. Benefits of Temporary Transit Lanes Made Permanent | SFMTA [Online]. Available: https://www.sfmta.com/blog/benefits-temporary-transit-lanes-made-permanent [Accessed September 8, 2022].

- Milneil, C., 2021, The WRTA’s Fare-Free Bus Experiment Was Popular, But Won’t Last Without Funding [Online]. @streetsblogMass. Available: 〈https://mass.streetsblog.org/2021/05/07/the-wrtas-fare-free-bus-experiment-was-popular-but-wont-last-without-funding/〉 [Accessed September 7, 2022].

- Moghimi B., Kamga C., Safikhani A., Mudigonda S., Vicuna P. Non-Stationary Time Series Model for Station-Based Subway Ridership During COVID-19 Pandemic: Case Study of New York City. Transp. Res. Rec. 2022 doi: 10.1177/03611981221084698. 03611981221084698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina A., Malalgoda N., Taleqani A.R., Mattson J., Ezekwem K., Askarzadeh T., Hough J. Surv. Transit Riders Agencies COVID-19 Pandemic. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- National Transit Database, 2022, Monthly Module Adjusted Data Release [Online]. @USDOT. Available: 〈https://www.transit.dot.gov/ntd/data-product/monthly-module-adjusted-data-release〉 [Accessed August 25, 2022].

- Orro A., Novales M., Monteagudo Á., Pérez-López J.-B., Bugarín M.R. Impact on city bus transit services of the COVID–19 lockdown and return to the new normal: the case of A Coruña (Spain) Sustainability. 2020;12:7206. [Google Scholar]

- Osorio J., Liu Y., Ouyang Y. Executive orders or public fear: What caused transit ridership to drop in Chicago during COVID-19? Transp. Res. Part D: Transp. Environ. 2022;105 doi: 10.1016/j.trd.2022.103226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palm M., Allen J., Liu B., Zhang Y., Widener M., Farber S. Riders who avoided public transit during COVID-19: Personal burdens and implications for social equity. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2021;87:455–469. [Google Scholar]

- Panik R.T., Watkins K., Ederer D. Metrics of Mobility: Assessing the Impact of COVID-19 on Travel Behavior. Transp. Res. Rec. 2022 doi: 10.1177/03611981221131812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker M.E., Li M., Bouzaghrane M.A., Obeid H., Hayes D., Frick K.T., Rodríguez D.A., Sengupta R., Walker J., Chatman D.G. Public transit use in the United States in the era of COVID-19: Transit riders’ travel behavior in the COVID-19 impact and recovery period. Transp. Policy. 2021;111:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2021.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polzin S., Choi T. COVID-19′s Effects on The Future of Transportation. U. S. Dep. Transp. OFFICE ASSISTANT SECRETARY. 2021 (FOR, R. T. (ed.)) [Google Scholar]

- Pozo R.F., Wilby M.R., Díaz J.J.V., González A.B.R. Data-driven analysis of the impact of COVID-19 on Madrid's public transport during each phase of the pandemic. Cities. 2022;127 doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2022.103723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC, 2023. COVID Data Tracker [Online]. @CDCgov. Available: 〈https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker〉 [Accessed May 03, 2023].

- Preciado, N. , Gabbert, L. & Vera, V., 2021, Nine dead in San Jose VTA shooting; light rail service suspended - San José Spotlight [Online]. @SJSpotlight. Available: 〈https://sanjosespotlight.com/vta-to-suspend-san-jose-light-rail-service-following-shooting/〉 [Accessed September 13, 2022].

- Qi Y., Liu J., Tao T., Zhao Q. Impacts of COVID-19 on public transit ridership. Int. J. Transp. Sci. Technol. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- Siewwuttanagul S., Jittrapirom P. The impact of COVID-19 and related containment measures on Bangkok’s public transport ridership. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2023;17 doi: 10.1016/j.trip.2022.100737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons R.A., Henning M., Poeske A., Trier M., Conrad K. Covid-19 and its effect on trip mode and destination decisions of transit riders: experience from Ohio. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2021;11 [Google Scholar]

- Spectrum Bay News 9, 2022, TECO Line Streetcar sees record ridership [Online]. Available: 〈https://www.baynews9.com/fl/tampa/news/2022/07/07/teco-line-streetcar-sees-record-ridership〉 [Accessed September 07, 2022].

- Sullivan R. The COVID-19 Pandemic's Impact on Public Transportation Ridership and Revenues Across New England. N. Engl. Public Policy Cent. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- Taylor B.D., Morris E.A. Public transportation objectives and rider demographics: are transit’s priorities poor public policy? Transportation. 2015;42:347–367. [Google Scholar]

- Tiikkaja H., Viri R. The effects of COVID-19 epidemic on public transport ridership and frequencies. A case study from Tampere, Finland. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2021;10 doi: 10.1016/j.trip.2021.100348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toledo Area Regional Transit Authority (Tarta) Announces Plans to Go Cashless. 2022. TARTA Extends Fare-Free Policy through July. (COLE, A. (ed.)) [Google Scholar]

- TransitCenter, 2023, Transit's Looming Fiscal Cliff: How Bad is it and What Can We Do? [Online]. @transitcenter. Available: 〈https://transitcenter.org/transits-fiscal-cliff-why-we-need-a-new-funding-paradigm/〉 [Accessed May 3, 2023].

- Walker, J., 2021, The Bus Driver Shortage is an Emergency — Human Transit [Online]. @humantransit. Available: 〈https://humantransit.org/2021/12/the-bus-driver-shortage-is-an-emergency.html〉 [Accessed December 10, 2021].

- TransitCenter, 2022, Bus Operators in Crisis: The Steady Deterioration of One of Transit’s Most Essential Jobs, and How Agencies Can Turn Things Around 2022 TransitCenter.

- Wang D., He B.Y., Gao J., Chow J.Y.J., Ozbay K., Iyer S. Impact of COVID-19 behavioral inertia on reopening strategies for New York City transit. Int. J. Transp. Sci. Technol. 2021;10:197–211. [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Noland R.B. Bikeshare and subway ridership changes during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City. Transp. Policy. 2021;106:262–270. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2021.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins K., Berrebi S., Erhardt G., Hoque J., Goyal V., Brakewood C., Ziedan A., Darling W., Hemily B., Kressner J. TCRP 231: Recent Decline in Public Transportation Ridership: Analysis, Causes, Responses. Transp. Res. Board. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- Wilbur M., Ayman A., Ouyang A., Poon V., Kabir R., Vadali A., Pugliese P., Freudberg D., Laszka A., Dubey A. Impact of COVID-19 on public transit accessibility and ridership. arXiv Prepr. arXiv. 2020;2008:02413. doi: 10.1177/03611981231160531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin M., Shalaby A., Feng S., Zhao H. Impacts of COVID-19 on urban rail transit ridership using the Synthetic Control Method. Transp. Policy. 2021;111:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2021.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]