Abstract

Phycobiliproteins is a family of chromophore-containing proteins having light-harvesting and antioxidant capacity. The phycocyanin (PC) is a brilliant blue coloured phycobiliprotein, found in rod structure of phycobilisome and has been widely studied for their therapeutic and fluorescent properties. In the present study, the hexameric assembly structure of phycocyanin (Syn-PC) from Synechococcus Sp. R42DM is characterized by X-ray crystallography to understand its light-harvesting and antioxidant properties. The crystal structure of Syn-PC is solved with 2.15 Å resolution and crystallographic R-factors, Rwork/Rfree, 0.16/0.21. The hexamer of Syn-PC is formed by heterodimer of two polypeptide chains, namely, α- and β-subunits. The structure is analysed at atomic level to reveal the chromophore microenvironment and possible light energy transfer mechanism in Syn-PC. The chromophore arrangement in hexamer, deviation angle and distance between the chromophore contribute to the energy transfer efficiency of protein. The structural attributes responsible for the antioxidant potential of Syn-PC are recognized and annotated on its 3-dimensional structure.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13205-023-03665-1.

Keywords: Synechococcus, Phycobiliproteins, Phycocyanin, X-ray crystallography, Antioxidant

Introduction

Cyanobacteria, isolated from different niches, display variation in amino acid composition and spectral properties of phycobiliproteins (PBP) to optimize maximum light harvesting (Patel et al. 2022). Synechococcus species are widely distributed in different environments and show versatility in PBP compositions (Adir et al. 2001, 2002; Pittera et al. 2017). The structural characterization of Phycocyanin (PC) from different Synechococcus species by X-ray crystallography has been carried out by several research groups to explore the structural attributes and chromophore positioning responsible for efficient light-harvesting activity (Adir et al. 2001, 2002; Everroad and Wood 2012; Murray et al. 2007). More than 20 crystal structures of phycocyanins (PC, the red-light absorbing PBP class) from Synechococcus and related cyanobacterial species (Thermosynechococcus elongatus BP-1, Thermosynechococcus vulcanus, Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942, S. elongatus, Synechococcus sp. JA-2-3B'a (2–13), Synechococcus sp. RCC307) have been solved and studied to understand their light-harvesting and energy transferring properties (Adir et al. 2001, 2002; Everroad and Wood 2012; Nield et al. 2003).

Besides the light-harvesting function, PBPs are useful in various nutraceutical and biomedical applications due to their biomedical properties, such as bright fluorescence, anti-inflammatory (Romay et al. 2003), hepatoprotective (Remirez et al. 2002), antioxidant (Sonani et al. 2017, 2014) and anti-cancer activities (Liao et al. 2016; Ravi et al. 2015). These properties differ between PBP of different origin due to the minor variations in their amino acid sequences and structures. The present study describes the crystal structure of PC of Synechococcus sp. R42DM, obtained from the industrially polluted site, Vatva (Gujarat, India). The atomic level structural details provide the description of chromophore geometry and microenvironment with high precision, which in turn allows the light energy transfer pathway prediction. Furthermore, the structural attributes responsible for the earlier described antioxidant activity of Syn-PC (Sonani et al. 2017) have also been recognized and annotated on its 3-dimensional atomic structure.

Materials and methods

Culture cultivation and Syn-PC purification

Cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. R42DM, isolated from industrially polluted site, Vatva, Gujarat, India was grown in BG-11 media (Rippka et al. 1979) at 27 ± 2 °C with 12:12 h light:dark cycles of illumination provided by 36W white fluorescent lamps (Sonani et al. 2017).

The optimally grown culture was harvested and treated with 0.01% Triton-X 100 followed by ultrasonication to extract out the intracellular soluble proteins. The purification of Syn-PC was performed as described earlier (Sonani et al. 2017). Briefly, the partial purification was performed by two steps (20% and 60% saturation) ammonium sulphate precipitation. The protein pellet obtained after 60% ammonium sulphate precipitation was subjected to dialysis and ion-exchange chromatography (DEAE-cellulose) to achieve high purity. The purity of protein was checked by SDS-PAGE and UV–visible spectroscopy.

Peptide Mass Fingerprinting (PMF) analysis

Peptide mass fingerprinting (PMF) analysis of purified Syn-PC subunits was performed as described earlier (Sonani et al. 2015). The obtained peptide masses were analysed against the SWISSPORT database using Mascot server (Perkins et al. 1999).

Sequence determination of Syn-PC

The gene-based sequencing approach was used to deduce full protein sequences of Syn-PC. The Primer3 server (Untergasser et al. 2012) was used to design primers for cpcA and cpcB genes expressing α- and β-subunits of Syn-PC, respectively. Both genes were PCR amplified from Synechococcus sp. R42DM genomic DNA using designed forward primer 5ʹ CAACGCATACACGAACCGTC 3ʹ and reverse primer 5ʹ CAGAATCTGCTCTTTCCGGGT 3ʹ for cpcA gene, and forward primer 5ʹ TCGCGATCGCTCTAAATCCC 3ʹ and reverse primer 5ʹ GACGGTTCGTGTATGCGTTG 3ʹ for cpcB gene. Amplified genes were sequenced using Sanger’s sequencing method. The obtained sequences were checked and edited using BioEdit software (Hall 1999) and sequences were deposited to NCBI GenBank. The amino acid sequences were deduced from the gene sequences and analysed with reference to PCs of other cyanobacteria species whose structures are available in the PDB using NCBI BLAST and Clustal Omega (Sievers et al. 2011).

Crystallization of Syn-PC

Crystallization conditions for Syn-PC (10 mg ml−1 in 20 mM Tris buffer, pH 8.0) were screened using pre-formulated commercial crystallization kits, JCSG + and PACT premier (Molecular Dimensions, UK). Crystallization was set with sitting drop 96-well 2-drop crystallization plates. The good-quality crystals were obtained at 27 °C in a condition of 0.1 M HEPES buffer pH 6.5 with 10% (W/V) PEG 6000. The diffraction quality crystals were cryo-protected using 20% glycerol before storing in the liquid nitrogen. The 3-dimensional diffraction data were acquired at PX BL-21 beam line, INDUS-2 synchrotron radiation facility, RRCAT, Indore, India (Kumar et al. 2016). The data were indexed and integrated by iMOSFLM (Battye et al. 2011). The scaling and merging of the data were performed by Aimless (Evans and Murshudov 2013) in a CCP4 suit (Winn et al. 2011). Data collection statistics is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

The X-ray crystallography data collection and structure refinement statistics of Syn-PC

| PDB ID | 7D6W |

| Data collection | |

| Space group | P 21 21 21 |

| Unit cell parameters | 106.63, 113.99, 183.59 (Å), 90.00, 90.00, 90.00 (o) |

| (αβ) per asymmetric unit | 6 (12 chains) |

| Observed reflections | 784,128 [37,448] |

| Unique reflections | 122,052 [5976] |

| Resolution (Å) | 96.84–2.15 [2.19–2.15] |

| Completeness (%) | 100 [100] |

| Rmerge | 0.12 [0.38] |

| CC1/2 | 0.99 [0.89] |

| I/σ (I) | 9.6 [4.1] |

| Multiplicity | 6.4 [6.3] |

| Mosaicity | 0.8 |

| Wilson B-factor (Å2) | 15.5 |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 96.84–2.15 |

| Number of reflections in working set | 121,960 |

| Number of reflections in test set | 6335 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.16/0.21 |

| Mean B-value (Å2) | 16.07 |

| R.m.s.d. bonds (Å) | 0.01 |

| R.m.s.d. angles (°) | 1.53 |

| Ramachandran values (%) | |

| Most favoured/additional allowed/disallowed | 98.22/1.48/0.31 |

Values given in square bracket indicate the highest resolution outer shell

Molecular replacement and structure refinement

The crystal of Syn-PC belongs to the P212121 space group. The initial phases were calculated using the structure of the PC of S. elongatus sp. PCC 7942, (PDB ID: 4H0M) as initial search model by molecular replacement (MR) method using the PHASER program (McCoy 2007). The structure refinement was performed by combination of automatic refinement using the REFMAC5 software (Murshudov et al. 2011) and interactive refinement using COOT (Emsley et al. 2010; Emsley and Cowtan 2004) until the reasonable agreement between diffraction data and model was obtained. The final refined structure and data were deposited to the PDB. The structure analysis and figure preparation were performed using PyMOL (Version 2.0 Schrödinger, LLC), Chimera (Pettersen et al. 2004), LigPlot+ (Laskowski and Swindells 2011), Mol* Viewer (Sehnal et al. 2021) and CCP4MG softwares (McNicholas et al. 2011).

In silico analysis of therapeutic potential of Syn-PC

The α- and β-subunit sequences of Syn-PC were analysed for their amino acid composition using ProtParam tool (http://www.expasy.ch/tools/protparam.html) (Gasteiger et al. 2005). The percentage of residues responsible for DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picryl-hydrazyl-hydrate) and FRAP (ferric reducing antioxidant power) activity was calculated as described by Udenigwe and Aluko (2011). The distribution of positive and negative contributing residues on the Syn-PC hexamer surface was visualized by PyMOL.

Results and discussion

Sequence analysis

The bands of α- and β-subunits of purified Syn-PC obtained in SDS-PAGE were characterized by LC–MS/MS analysis. The m/z ratio of the peptides was compared with the protein sequences available at SWISSPORT database. The peptides of α- and β-subunits showed the similarity with the PC of Synechococcus sp. (strain ATCC 27144/PCC 6301/SAUG 1402/1) (Online Resources 1 and 2).

To obtain full protein sequences, Syn-PC α- and β-subunit encoding genes, cpcA and cpcB, were amplified by gene specific primers, sequenced and deposited to the NCBI database with accession numbers, MW526393 and MW526394, respectively. Syn-PC α- and β-subunits are composed of 162 and 172 amino acids, respectively. The experimentally determined sequences of both subunits were modelled in the electron density maps. The multiple sequence alignment of Syn-PC with other PCs is shown in Online Resource 3, which shows the 100% sequence identity with the protein sequences of PC structure PDB ID 4H0M (of cyanobacteria S. elongatus PCC 7942) despite that the two species are from totally different ecological niches (Marx and Adir 2013). The identity of protein is also confirmed at protein level by peptide mass fingerprinting of the α- and β-subunits of the Syn-PC. The Syn-PC protein having sequence similarities was further analysed and compared to check the changes occurring in structural features and chromophore microenvironment by X-ray crystallography. The Syn-PC structure is refined to the excellent fit in electron density map (Rfree/work = 0.16/0.21), compared to previously reported structure (PDB ID: 4H0M; Rfree/work = 0.24/0.29), which was helpful in describing the energy transfer pathways and chromophore microenvironment within 3-dimensional structure. Additionally, the earlier observed (Sonani et al. 2017) antioxidant property of Syn-PC is rationalized with mapping of the residues on the presently solved atomic 3-dimensional structure.

Crystallographic analysis

Syn-PC crystal belongs to P21212 space group with unit cell parameters a = 106.63, b = 113.99, c = 183.59 (Å) and α, β, γ = 90.00 (deg). The asymmetric unit of Syn-PC crystal is made up of six copies of each, α- and β-subunits and 18 chromophores (phycocyanobilin; PCB) with 53.25% solvent content. The data collection and refinement statistics are detailed in Table 1. Diffraction data allowed constructing the final model with 2.15 Å resolution with reasonable R-factors values (Rwork/Rfree, 0.16/0.21). The representative view of PCB and interaction with surrounding residue are shown in Fig. 1. The quality of electron density maps obtained from X-ray crystallographic data describe main chains and side chains of almost all residues of both α- and β-subunits and water molecules H-bonded to the protein. The final structure was validated by the Ramachandran plot which showed 98.22/1.48/0.31 (%) residues falling within Ramachandran favoured/allowed/outliers regions (Online Resource 4). Furthermore, the final model was evaluated by MOLPROBITY (Chen et al. 2010), which showed good stereochemistry with a clash score of 3.79 and overall MOLPROBITY score of 1.17. The refined model and diffraction data have been deposited to the Protein Data Bank with PDB ID, 7D6W.

Fig. 1.

X-ray structure of Syn-PC, the blue stick model represents the PCB chromophore, yellow line illustrates the H-bonds with the surrounding residues. This image was created using Chimera software (Pettersen et al. 2004)

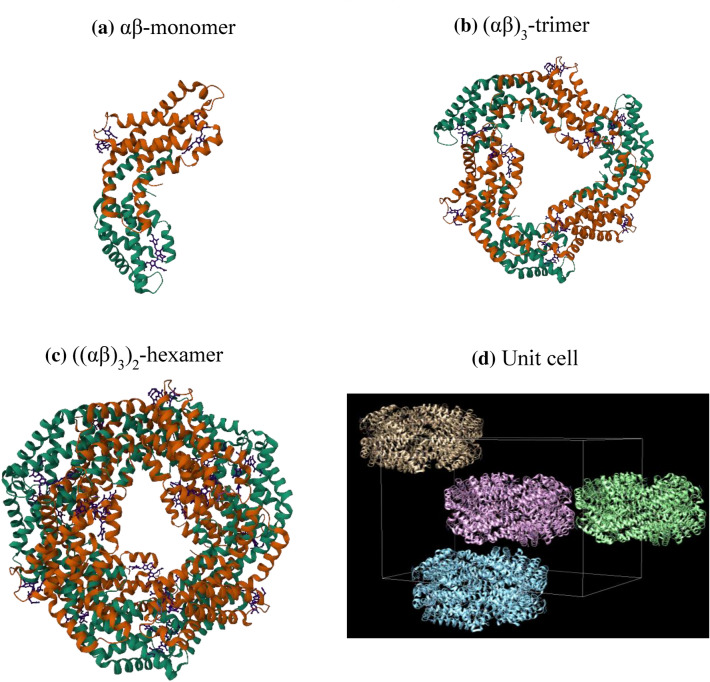

Structural analysis of Syn-PC

The Syn-PC shows similar overall tertiary fold as compared to other reported PC structures. Its α- and β-subunits interact with each other and form the stable heterodimer (hereafter, αβ monomer) (Fig. 2a) with total buried area of ~ 6378 (± 67) Å2 and solvation free energy gain of 72 (± 0.67) kcal/mol, as calculated by the PISA server (Krissinel and Henrick 2007). The disc-like structure trimer (αβ)3 is formed by association of three αβ monomers with a total buried area of ~ 24,135 (± 91) Å2 and solvation free energy gain of 252 (± 2.68) kcal/mol. The α-subunit of one monomer interacts with the β-subunit of neighbouring monomers, thus following C3 symmetry (Fig. 2b). Two trimers form the biologically active unit of PBS, the hexameric assembly ((αβ)3)2 of the Syn-PC (Fig. 2c) with a total buried area of 60,857.2 Å2 and a solvation free energy gain of 516.3 kcal/mol (Krissinel and Henrick 2007). The arrangement of four hexamers with reference to the crystallographic unit cell is represented in Fig. 2d.

Fig. 2.

Cartoon representation of a αβ monomer, b (αβ)3 trimer, and c ((αβ)3)2 hexamer of Syn-PC. Cartoon ribbons in green and brown colour indicate α- and β-subunits, respectively. The chromophores are represented by pink stick structure, d Cartoon representation of four Syn-PC hexamers with reference to the crystallographic unit cell. These figures were prepared by Mol* viewer (Sehnal et al. 2021)

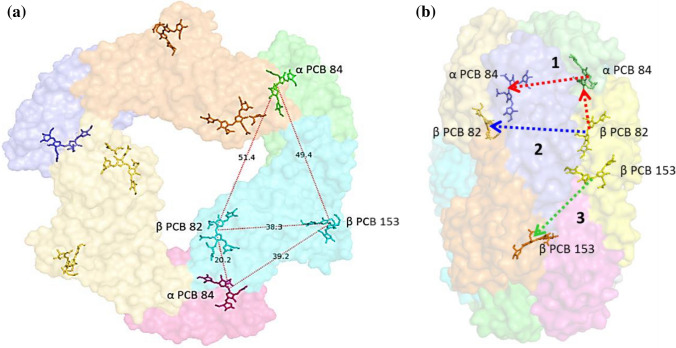

Chromophore microenvironment, geometry and energy transfer pathways

There are three phycocyanobilin (PCB) chromophores covalently attached to the conserved cysteine residues of each αβ monomer. The α-subunit contains a single PCB attached to the αCys84 residue which we name αPCB84. The β-subunit contains two PCBs attached to βCys82 and βCys153 residues are named as βPCB82 and βPCB153, respectively. The PCB is composed of the tetrapyrrole ring as shown in Online Resource 5, the ring covalently attached to the cysteine residue is named as ring A followed by rings B, C and D (Peng et al. 2014). All PCBs within Syn-PC adopt overall curved geometry and coplanarity between central two rings, B and C. Such characteristic geometry of PCB is imposed by its interaction with the conserved aspartate residues (Gupta et al. 2016; Sonani et al. 2020). The stable conformation of the PCB is further supported by the network of hydrogen bonds (H-bonds) and hydrophobic interactions with the surrounding residues, as shown in the 2D representation using LigPlot+ (Laskowski and Swindells 2011) (Online Resources 5 and 6).

The αPCB84 chromophore of α-subunit is stabilized by the hydrogen bond between A ring of αPCB84 and side chain atom of αAsn73. The B ring forms two H-bonds with two side chain atoms of βArg57 of adjacent monomer and an H-bond with side chain atom of αAsp87. The C ring of PCB forms an H-bond with side chain atoms of αLys83 and αAsp87. The two H-bonds are found between ring C and side chain atoms of αArg86. The αAsp87 seems to play a crucial role in maintaining the coplanarity between B and C rings and thus specific spectral property of αPCB84. The D ring of PCB forms an H-bond with the main chain atom of βThr75 of the adjacent monomer (Online Resource 5a).

The βPCB82 is found to be located towards the inner cavity of the trimer disc and located closest to the αPCB84 of the adjacent monomer (Fig. 3). It is surrounded by and interacts with only residues of the same β-subunit and does not show interaction with residues of the adjacent monomers. The conformation and angle between ring A and ring B of βPCB82 is controlled by H-bond with the side chain atoms of surrounding residues, methylated asparagine βMeN72 and βArg77, respectively. βMeN72 is a methylated form of the Asn residue also found in several other PC structures (Ferraro et al. 2020; Patel et al. 2019). The side chain atoms of βAsp85 are involved in maintaining the coplanarity between the rings B and C by H-bonds (Online Resource 5b).

Fig. 3.

a Diagram representing arrangement of PCBs and the possible closest distances between the PCBs of monomers within the trimeric disc of Syn-PC. b Possible energy transfer pathways in the hexamer. These figures were prepared using PyMOL software

The βPCB153 is covalently bound to Cys153 and resides on the outer surface of the trimer disc (Fig. 3). This is the only chromophore which shows the interaction between two trimers. The βPCB153 forms a total nine hydrogen bonds with surrounding residues out of which three H-bonds are with the α-subunit of adjacent monomers of other trimeric disc. As shown in Online Resource 5c, the A ring forms two hydrogen bonds, one with main chain atom of βGly151 and another with side chain atom of βThr149. The orientation of ring B is maintained by H-bonds with side chain atoms of two residues βAsp39 and βAsn35. The ring C is stabilized by interaction with the side chain atoms of Asp39 and Thr149 and forms hydrogen bonds. Three hydrogen bonds are formed by ring D with side chain atoms surrounding αAsp145, αArg32 and αGln33 of the α-subunit of adjacent trimer structure (Online Resource 5c).

Surrounding interactions with residues provides each chromophore the stable conformation and position with specific planarity between their pyrrole rings. The light absorption property of PCB is influenced by the π-conjugation and deviation of ring D plane with respect to ring B–C plane (Peng et al. 2014; Sonani et al. 2019). The Syn-PC also shows the coplanarity in rings B and C with deviation angle in the range of 5°–13° in all three PCBs. The deviation of ring D plane from B–C rings co-plane in αPCB84, βPCB82 and βPCB153 is 27.7° ± 3.4°, 40.42° ± 0.75° and 16.97° ± 1.83°, respectively. The αPCB84 and βPCB82 chromophores in S. elongatus sp. PCC 7942 phycocyanin structure (PDB id: 4H0M) show deviation angles, 29.82° ± 3° and 43.76° ± 2.8°, respectively, which are close to those measured by our Syn-PC structure. But the deviation angle in βPCB153 differs slightly in present Syn-PC (16.97° ± 1.83°) than that in the 4H0M structure (11.47° ± 3.43°). The comparison of interaction analysis of Syn-PC structure shows the presence of extra H-bonds between D ring of βPCB153 and residue (Asp145, Arg32, Gln33) of adjacent monomer (E monomer) is responsible for angle deviation and stabilization of the chromophore. It has been proposed that the chromophore with the high deviation angle shows the blue shift in their absorption spectra and absorbs the light with high energy and passes it to the chromophores having low deviation angles (Patel et al. 2019; Peng et al. 2014).

Excitation energy transfer (EET) pathway within hexamer has been deduced based on inter-chromophore distances and the deviation angle of pyrrole rings (Table 2) (Fig. 3) (Duerring et al. 1991; Jiang et al. 1999; Nield et al. 2003). Based on the closest distance between chromophores, three possible pathways have been proposed for Syn-PC hexameric structure. The closest chromophores are αPCB84 and βPCB82 with distance 20.13 ± 0.07 Å within the trimer, so, first proposed pathway (βPCB82 → αPCB84 → αPCB84*; *indicates different trimer) includes both intra-timer and inter-trimer transfer components, which is necessary for unidirectional energy transfer within PC rods. The second proposed pathway is βPCB82 → βPCB82* (between two trimers) and third is βPCB153 to βPCB153* (between two trimers) (Fig. 3b).

Table 2.

The possible closest distances between phycocyanobilins of Syn-PC in αβ monomer, (αβ)3 trimer and ((αβ)3)2 hexamer assemblies

| Assembly | Distance (Å) between | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| αPCB84 and βPCB82 | αPCB84 and βPCB153 | βPCB82 and βPCB153 | Inter αPCB84 | Inter βPCB82 | Inter βPCB153 | |

| αβ monomer | 49.27 ± 0.1 | 51.25 ± 0.11 | 38.46 ± 0.1 | – | – | – |

| (αβ)3 trimer (between adjacent monomers) | 20.13 ± 0.07 | 39.36 ± 0.11 | 46.47 ± 0.14 | 68.21 ± 0.13 | 34.14 ± 0.23 | 82.60 ± 0.11 |

| ((αβ)3)2 hexamer (between monomers of two trimers) | 36.13 ± 0.13 | 40.31 ± 0.09 | 45.48 ± 0.24 | 27.0 ± 0.12 | 34.02 ± 0.41 | 25.24 ± 0.10 |

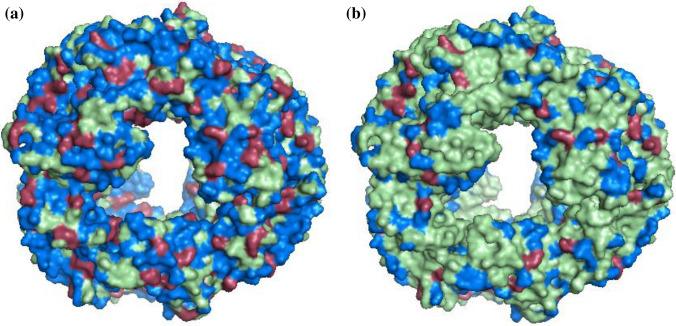

Implications of antioxidant properties of Syn-PC

The analysis of amino acid sequences of different antioxidant peptides showed the presence of high proportion of hydrophobic amino acids and charged amino acids in their sequences and those have been proposed to contribute in antioxidant activities (Zou et al. 2016). The α- and β-subunit amino acid composition of Syn-PC was analysed by ExPASy ProtParam online tool (Online Resource 7). The α-subunit contains 9.9% and 8.6% negatively and positively charged residues, respectively, whereas β-subunits contains 12% and 10.3% negatively and positively charged residues, respectively. The high proportion of hydrophobic amino acids, like Gly, Ala, Val, Leu, Ile, Pro, Phe, Met and Trp, have been found in Syn-PC. The α- and β-subunits of Syn-PC contain total 83 (~ 51% of total) and 95 (~ 54% of total) hydrophobic amino acids, respectively, contributing the radical scavenging activity.

Based on amino acid composition, Udenigwe and Aluko (2011) had classified the amino acid residues in positive and negative contributors for the DPPH activity and ferric reducing ability (FRAP) activities. Syn-PC has been characterized to possess in vitro and in vivo antioxidant activities in an earlier report (Sonani et al. 2017). Given the availability of high-quality 3-dimensional structure, the distribution of positively and negatively contributing residues on Syn-PC structure is analysed. According to this classification, the present Syn-PC contains a total 68% and 68.9% positive contributors of DPPH in α- and β-subunits, respectively (Table 3), whereas it contains only 9.2% and 10.4% negative contributors of DPPH in α- and β-subunits, respectively (Table 3). The percentage of positive contributors for FRAP/RP activity in α- and β-subunits is 18.6% and 23%, respectively. The percentage of negative contributors for FRAP/RP activity in α- and β-subunits is 4.9% and 2.9%, respectively. Total positive contributors cover 56.29% (for DPPH-scavengers) and 30.34% (FRAP/RP-scavengers) of total surface of Syn-PC hexamer structure, whereas total negative contributors covering the surface of Syn-PC hexamer structure are only 18.87% and 7.13% for DPPH and FRAP/RP activities, respectively (Fig. 4). The higher distribution of positive contributors on the surface justifies earlier observed antioxidant potential of Syn-PC.

Table 3.

The percentage of positively and negatively contributing residues to DPPH and FRAP/RP activities in Syn-PC sequences

| Alpha-subunit (%) | Beta-subunit (%) | % coverage on surface area (in hexamer) (%) | % coverage on surface area (in monomer) (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPPH | Positive contributors (D, N, T, V, I, P, A, C, M, F, L, Y and W) | 68 | 68.9 | 56.29 | 54.33 |

| Negative contributors (H, K and R) | 9.2 | 10.4 | 18.87 | 19.01 | |

| FRAP/RP | Positive contributors (C, M, E, Q, D and N) | 18.6 | 23 | 30.34 | 28.98 |

| Negative contributors (K) | 4.9 | 2.9 | 7.13 | 6.99 |

Capital letters in bracket () represent the strong positive/negative contributing amino acids for DPPH and FRAP/RP activity

Fig. 4.

Distribution of residues on the surface of hexamer structure contributing for DPPH and FRAP/RP activity. a Surface distribution of positive and negative contributors for DPPH activity. b Surface distribution of positive and negative contributors for FRAP/RP activity. Here, hexamer structure is represented in pale green colour, whereas positive and negative contributors are represented by marine blue colour and red colour, respectively. These figures were created using PyMOL

Conclusions

In the present study, the crystal structure of Syn-PC is analysed in order to understand its light-harvesting and antioxidant activities. The Syn-PC forms the hexameric structure by face-to-face assembly of two trimers. The chromophore arrangement and deviation angle within hexamer were analysed to draw out the possible EET pathway. The nearest chromophores were considered for the EET in the present model. In cyanobacteria, the hexameric form of PC arranges in the rod structures and there are several such rod structures that may radiate from the core of the phycobilisome. In the present study we could deduce the EET path within chromophores of two trimers in same hexamer. The chromophore microenvironment and their interaction with surrounding residues were found to be similar to PC structure (PDB ID: 4H0M) except that the ring D of βPCB153 chromophore in Syn-PC that shows the deviated conformation than 4H0M structure. Both of these Synechococcus species have been isolated from different geological sources. The chromophore arranges within the hexamer in such a way to fulfil the energy demand of the cyanobacteria in that environment by photosynthesis. The deviation observed in current Syn-PC could be the reason of adaptation to environment conditions. Since this change in deviation angle is observed only in one chromophore out of three chromophores of the monomer, the effect of crystallization condition can be neglected. Further, the distribution of residues on 3D structure suggests that the Syn-PC is a strong contributor of antioxidant activity. These fluorescence and antioxidant properties of Syn-PC can be explored further for their usage in various food, cosmetics and pharmaceutical industries.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

DM and SNP are thankful to PDPIAS, CHARUSAT and Bhartiben and P. R. Patel Biological Research Laboratory for providing instrumental facility to conduct this research. DM acknowledges the Gujarat Council on Science and Technology, Gandhinagar, Gujarat, India (GUJCOST/STI/2021-22/3878) for financial support. The authors acknowledge Indus-2, RRCAT, Indore and Dr. Ravindra D. Makde for the help in diffraction data acquisition.

Author contributions

SNP, RRS and MGC conducted crystallographic experiments and analysed the data; VK and GDG contributed in reviewing and correcting the structure; SNP and RRS wrote the manuscript; DM contributed in conceptualization and arranging the funding; VK, GDG, NKS and DM proofread the results and edited the manuscript.

Data availability

Accession numbers: The Syn-PC crystal structure is available at the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with PDB ID 7D6W. The α- and β-subunit gene sequences are available at NCBI Nucleotide database with accession numbers MW526393 and MW526394, respectively.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Mukesh G. Chaubey: Deceased.

Contributor Information

Vinay Kumar, Email: vkbhatia@gmail.com.

Datta Madamwar, Email: datta_madamwar@yahoo.com.

References

- Adir N, Dobrovetsky Y, Lerner N. Structure of c-phycocyanin from the thermophilic cyanobacterium Synechococcus vulcanus at 2.5 Å: structural implications for thermal stability in phycobilisome assembly11 Edited by R. Huber. J Mol Biol. 2001;313:71–81. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adir N, Vainer R, Lerner N. Refined structure of c-phycocyanin from the cyanobacterium Synechococcus vulcanus at 1.6 Å: insights into the role of solvent molecules in thermal stability and co-factor structure. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA) Bioenerget. 2002;1556:168–174. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2728(02)00359-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battye TGG, Kontogiannis L, Johnson O, Powell HR, Leslie AGW. iMOSFLM: a new graphical interface for diffraction-image processing with MOSFLM. Acta Cryst D. 2011;67:271–281. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910048675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen VB, Arendall WB, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Cryst D. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duerring M, Schmidt GB, Huber R. Isolation, crystallization, crystal structure analysis and refinement of constitutive C-phycocyanin from the chromatically adapting cyanobacterium Fremyella diplosiphon at 1.66 Å resolution. J Mol Biol. 1991;217:577–592. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90759-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Cryst D. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Cryst D. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans PR, Murshudov GN. How good are my data and what is the resolution? Acta Cryst D. 2013;69:1204–1214. doi: 10.1107/S0907444913000061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everroad RC, Wood AM. Phycoerythrin evolution and diversification of spectral phenotype in marine Synechococcus and related picocyanobacteria. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2012;64:381–392. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro G, Imbimbo P, Marseglia A, Lucignano R, Monti DM, Merlino A. X-ray structure of C-phycocyanin from Galdieria phlegrea: determinants of thermostability and comparison with a C-phycocyanin in the entire phycobilisome. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA) Bioenerget. 2020;1861:148236. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2020.148236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasteiger E, Hoogland C, Gattiker A, Duvaud S, Wilkins MR, Appel RD, Bairoch A. The proteomics protocols handbook. Totowa: Humana Press; 2005. Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPASy Server; pp. 571–607. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta GD, Sonani RR, Sharma M, Patel K, Rastogi RP, Madamwar D, Kumar V. Crystal structure analysis of phycocyanin from chromatically adapted Phormidium rubidum A09DM. RSC Adv. 2016;6:77898–77907. doi: 10.1039/C6RA12493C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall TA. Presented at the nucleic acids symposium series. London: Information Retrieval Ltd.; 1999. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT; pp. 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang T, Zhang J, Liang D. Structure and function of chromophores in R-phycoerythrin at 1.9 Å resolution. Proteins Struct Funct Bioinform. 1999;34:224–231. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0134(19990201)34:2<224::AID-PROT8>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krissinel E, Henrick K. Protein interfaces, surfaces and assemblies service PISA at European Bioinformatics Institute. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:774–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Ghosh B, Poswal HK, Pandey KK, Jagannath, Hosur MV, Dwivedi A, Makde RD, Sharma SM. Protein crystallography beamline (PX-BL21) at Indus-2 synchrotron. J Synchrotron Rad. 2016;23:629–634. doi: 10.1107/S160057751600076X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA, Swindells MB. LigPlot+: multiple ligand-protein interaction diagrams for drug discovery. J Chem Inf Model. 2011;51:2778–2786. doi: 10.1021/ci200227u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao G, Gao B, Gao Y, Yang X, Cheng X, Ou Y. Phycocyanin inhibits tumorigenic potential of pancreatic cancer cells: role of apoptosis and autophagy. Sci Rep. 2016;6:34564. doi: 10.1038/srep34564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx A, Adir N. Allophycocyanin and phycocyanin crystal structures reveal facets of phycobilisome assembly. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA) Bioenerget. 2013;1827:311–318. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy AJ. Solving structures of protein complexes by molecular replacement with Phaser. Acta Cryst D. 2007;63:32–41. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906045975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNicholas S, Potterton E, Wilson KS, Noble MEM. Presenting your structures: the CCP4mg molecular-graphics software. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67:386–394. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911007281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray JW, Maghlaoui K, Barber J. The structure of allophycocyanin from Thermosynechococcus elongatus at 3.5 Å resolution. Acta Cryst Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2007;63:998–1002. doi: 10.1107/S1744309107050920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov GN, Skubák P, Lebedev AA, Pannu NS, Steiner RA, Nicholls RA, Winn MD, Long F, Vagin AA. REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Cryst D. 2011;67:355–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911001314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nield J, Rizkallah PJ, Barber J, Chayen NE. The 1.45Å three-dimensional structure of C-phycocyanin from the thermophilic cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus. J Struct Biol. 2003;141:149–155. doi: 10.1016/S1047-8477(02)00609-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel HM, Roszak AW, Madamwar D, Cogdell RJ. Crystal structure of phycocyanin from heterocyst-forming filamentous cyanobacterium Nostoc sp. WR13. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;135:62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.05.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel SN, Sonani RR, Roy D, Singh NK, Subudhi S, Pabbi S, Madamwar D. Exploring the structural aspects and therapeutic perspectives of cyanobacterial phycobiliproteins. 3 Biotech. 2022;12:224. doi: 10.1007/s13205-022-03284-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng P-P, Dong L-L, Sun Y-F, Zeng X-L, Ding W-L, Scheer H, Yang X, Zhao K-H. The structure of allophycocyanin B from Synechocystis PCC 6803 reveals the structural basis for the extreme redshift of the terminal emitter in phycobilisomes. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Biol Crystallogr. 2014;70:2558–2569. doi: 10.1107/S1399004714015776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins DN, Pappin DJ, Creasy DM, Cottrell JS. Probability-based protein identification by searching sequence databases using mass spectrometry data. Electrophoresis. 1999;20:3551–3567. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19991201)20:18<3551::AID-ELPS3551>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. UCSF Chimera–a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittera J, Partensky F, Six C. Adaptive thermostability of light-harvesting complexes in marine picocyanobacteria. ISME J. 2017;11:112–124. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravi M, Tentu S, Baskar G, Rohan Prasad S, Raghavan S, Jayaprakash P, Jeyakanthan J, Rayala SK, Venkatraman G. Molecular mechanism of anti-cancer activity of phycocyanin in triple-negative breast cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:768. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1784-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remirez D, Fernández V, Tapia G, González R, Videla LA. Influence of C-phycocyanin on hepatocellular parameters related to liver oxidative stress and Kupffer cell functioning. Inflamm Res. 2002;51:351–356. doi: 10.1007/PL00000314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rippka R, Deruelles J, Waterbury JB, Herdman M, Stanier RY. Generic assignments, strain histories and properties of pure cultures of cyanobacteria. Microbiology. 1979;111:1–61. doi: 10.1099/00221287-111-1-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romay C, Gonzalez R, Ledon N, Remirez D, Rimbau V. C-Phycocyanin: a biliprotein with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2003;4:207–216. doi: 10.2174/1389203033487216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehnal D, Bittrich S, Deshpande M, Svobodová R, Berka K, Bazgier V, Velankar S, Burley SK, Koča J, Rose AS. Mol* Viewer: modern web app for 3D visualization and analysis of large biomolecular structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:W431–W437. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, Lopez R, McWilliam H, Remmert M, Söding J, Thompson JD, Higgins DG. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:539. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonani RR, Singh NK, Awasthi A, Prasad B, Kumar J, Madamwar D. Phycoerythrin extends life span and health span of Caenorhabditis elegans. Age (dordr) 2014;36:9717. doi: 10.1007/s11357-014-9717-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonani RR, Rastogi RP, Joshi M, Madamwar D. A stable and functional single peptide phycoerythrin (15.45 kDa) from Lyngbya sp. A09DM. Int J Biol Macromol. 2015;74:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonani RR, Patel S, Bhastana B, Jakharia K, Chaubey MG, Singh NK, Madamwar D. Purification and antioxidant activity of phycocyanin from Synechococcus sp. R42DM isolated from industrially polluted site. Biores Technol. 2017;245:325–331. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.08.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonani RR, Rastogi RP, Patel SN, Chaubey MG, Singh NK, Gupta GD, Kumar V, Madamwar D. Phylogenetic and crystallographic analysis of Nostoc phycocyanin having blue-shifted spectral properties. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46288-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonani RR, Roszak AW, Liu H, Gross ML, Blankenship RE, Madamwar D, Cogdell RJ. Revisiting high-resolution crystal structure of Phormidium rubidum phycocyanin. Photosynth Res. 2020;144:349–360. doi: 10.1007/s11120-020-00746-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udenigwe CC, Aluko RE. Chemometric analysis of the amino acid requirements of antioxidant food protein hydrolysates. Int J Mol Sci. 2011;12:3148–3161. doi: 10.3390/ijms12053148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Untergasser A, Cutcutache I, Koressaar T, Ye J, Faircloth BC, Remm M, Rozen SG. Primer3—new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:e115–e115. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn MD, Ballard CC, Cowtan KD, Dodson EJ, Emsley P, Evans PR, Keegan RM, Krissinel EB, Leslie AGW, McCoy A, McNicholas SJ, Murshudov GN, Pannu NS, Potterton EA, Powell HR, Read RJ, Vagin A, Wilson KS. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Cryst D. 2011;67:235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou T-B, He T-P, Li H-B, Tang H-W, Xia E-Q. The structure-activity relationship of the antioxidant peptides from natural proteins. Molecules. 2016;21:72. doi: 10.3390/molecules21010072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Accession numbers: The Syn-PC crystal structure is available at the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with PDB ID 7D6W. The α- and β-subunit gene sequences are available at NCBI Nucleotide database with accession numbers MW526393 and MW526394, respectively.