Abstract

Acute phase COVID-19 has been associated with an increased risk for several mental health conditions, but less is known about the interaction of long COVID and mental illness. Prior reports have linked long COVID to PTSD, depression, anxiety, obsessive compulsive symptoms, and insomnia. This case report describes a novel presentation of mania arising in the context of long COVID symptoms with attention given to possible interacting etiological pathways. The case report also highlights the need for integrated, multidisciplinary treatment to support patients whose alarming, confusing, and multidetermined symptoms increase risk of psychological deterioration.

Keywords: Long COVID, bipolar disorder, mania, integrated care, personalized medicine, complex comorbidities

Introduction

Seemingly overnight, the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) led to the global deconstruction of societal functioning and shook the foundation of mental and physical health worldwide. Limited access to resources (i.e., food, healthcare, education) and mounting financial uncertainties contributed to increasing psychological distress (Zheng et al., 2021) that eclipsed individual coping capacities and drove symptoms and dysfunction above clinical thresholds (Xiong et al., 2020). Psychiatric morbidity with acute phase COVID-19 has been well-established, with reports of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), generalized anxiety, depression, psychosis, and delirium occurring most frequently (Hossain et al., 2020; Iqbal et al., 2020; O'Leary and Keenmon, 2023; Poyraz et al., 2021; Rogers et al., 2020). Increased stress, anxiety, and depressive thoughts due to the COVID-19 outbreak have been pervasive across populations (Czeisler et al., 2020; Salari et al., 2020; Son et al., 2020), and there have been an observable rise in substance use for coping (Czeisler et al., 2020).

Post-acute-COVID syndrome, or “long-COVID” is defined as the continued experience of clinical symptoms after a microbiological recovery is complete as indicated by a negative PCR test (Raveendran et al., 2021). Long-COVID symptoms commonly include a variety of physical concerns, especially: fatigue, dyspnea, pain symptoms, brain fog, cognitive deficits, and cardiovascular abnormalities (Crook et al., 2021; del Rio et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2022; Venkataramani and Winkler, 2022). Long-COVID has been linked with an increased incident of mental health concerns, particularly, PTSD, depression, anxiety, obsessive compulsive symptoms, and insomnia (Crook et al., 2021). Although there are reports of mania and psychosis occurring in patients experiencing acute phase COVID-19 symptoms or in those who have recovered (Correa-Palacio et al., 2020; Haddad et al., 2021; Khatib et al., 2021; Noone et al., 2020; O'Leary and Keenmon, 2023; Shanmugam et al., 2021), there are no known reports of mania associated with long-COVID. This paper presents the novel case of an individual who experienced an episode of mania and psychosis in the context of long-COVID symptomology. We also highlight the potential efficacy of integrated, multimodal treatment for disrupting the negative interaction of long-COVID psychiatric and physical symptoms.

Case Background

Ms. A, a middle-aged, Caucasian female, was a high performing business executive in excellent physical health when she developed a moderate case of COVID-19 on April 24, 2022. Prior to infection, her medical history was significant only for mild intermittent asthma without complications that was well-managed with as-needed albuterol as well as multivitamin/pyridoxine supplementation. Her psychiatric history was significant for childhood trauma and family conflict for which she had sought psychotherapy but had never been diagnosed with a mental illness or had periods of functional impairment. She reported past episodes of increased goal-directed behavior and impaired judgment, though these behaviors appeared to be secondary to her hyperthymic temperament (Akiskal and Mallya, 1987) rather than an undiagnosed bipolar condition. Cyclothymia was also considered given the vulnerability to bipolar disorder in those with cyclothymia (Baldessarini et al., 2011), but the patient rarely if ever experienced depressive symptoms and tended to maintain an unshakably upbeat attitude. The patient indicated that no one in her family had been diagnosed with a mental illness, although she indicated that her father may have had symptoms of mania. She reported that at the time of her COVID-19 infection, she was using CBD and medical marijuana 1-2 times per week (1-5 mg per use), but she indicated that she discontinued use while symptomatic and did not restart.

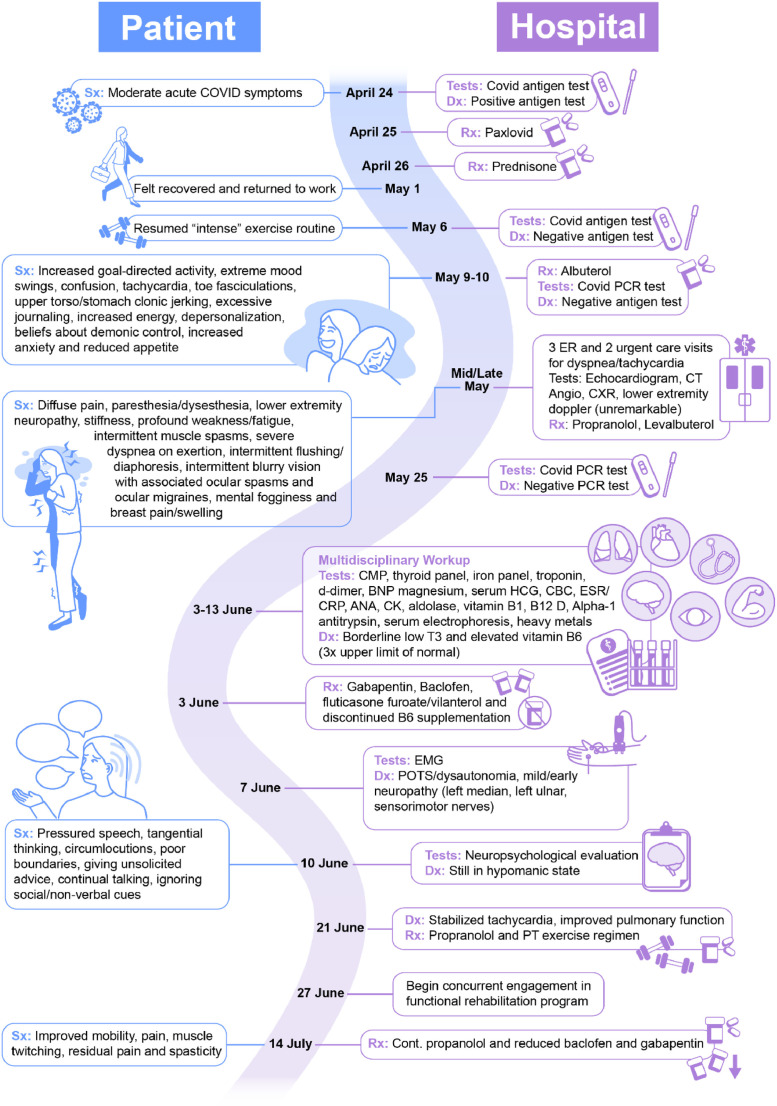

On April 25, 2022, a day after testing positive for COVID-19, she was started on a course of antiviral therapy (nirmatrelvir, 300 mg/ritonavir, 100 mg, twice daily for five days) at a local healthcare facility. She had been taking fluticasone for several days prior due to feeling her lungs tightening. On April 26th, she presented to a local ER for worsening asthma symptoms and was prescribed prednisone, which she took until May 1st (200 mg total). On May 6th, she tested negative for COVID-19 with a rapid test and was able to return to work and normal intensive exercise routine which included regular treadmill walking, 20 to 45 minute outdoor walks, and rowing. During the following weeks, Ms. A noted the onset of post-COVID symptoms including worsening dyspnea and tachycardia upon minimal physical exertion. On May 9, she began displaying prominent manic and possible psychotic features lasting approximately 8 days. These included reduced sleep (e.g., 1-4 hours per night), increased goal-directed behavior (e.g., 100 pages of journaling in 2 days, painting for hours), increased energy, reduced appetite, beliefs that a demonic power was tormenting her mind, disorganized thinking and confusion, depersonalization, and extreme mood swings (laughing and crying spells). In addition, anxiety symptoms were noted including rumination about asthma and panic attacks (Refer to Figure 1 for a review of symptom timeline). During the week of May 9th, she experienced as many as nine asthma attacks and used an albuterol inhaler to manage.

Figure 1.

Detailed timeline of patient's illness course and treatment.

Ms. A presented to local ERs and urgent care repeatedly thereafter for dyspnea and tachycardia. She indicated that during this time she began utilizing a wheelchair because any movement reportedly triggered dyspnea. She developed multisystemic issues including diffuse pain, paresthesia and dysesthesia (face, behind ears, neck, pain in scapular area bilaterally, calves), toe fasciculations, lower extremity neuropathy, stiffness, profound weakness/fatigue (inability to walk more than 30 steps), intermittent muscle spasms, localized skin discoloration, intermittent flushing and diaphoresis, intermittent blurry vision with associated ocular spasms and ocular migraines, mental fogginess, and breast pain and swelling. Medical tests were all unremarkable (echocardiogram, computed tomography angiography, chest x-ray, lower extremity doppler). She was started on propranolol and levalbuterol.

Clinical Presentation

Due to continued struggle and profound physical impairment, on June 2, 2022, Ms. A sought out a multidisciplinary evaluation and treatment at Houston Methodist's long-COVID clinic. She presented as functionally disabled by her physical and psychiatric symptoms. She struggled to walk and arrived at appointments riding an electric scooter. She was seen by a team of providers, including internal medicine, pulmonology, physiatry, neurology, and neuropsychology. Medically, her labs were all within normal limits aside from an elevated vitamin B6 level, which may have been causing pyridoxine toxicity, a known contributor to peripheral sensory neuropathy, difficulty with ambulation, hyperesthesia, bone pains, numbness, and fasciculations (Albin et al., 1987; Dalton, 1987). Cardiology performed a PET myocardial perfusion scan that was unremarkable. Neurology's electromyography revealed carpal tunnel syndrome, mild left ulnar sensory neuropathy, and possible mild and early sensorimotor neuropathy.

During Ms. A's meeting with the neuropsychologist on June 10, lingering symptoms of mania were observed including pressured speech, tangential thinking, circumlocutions, and continued beliefs about demonic influence involving persecutory ideation. She displayed poor boundaries, including giving unsolicited advice and coaching to strangers. She was unable to appreciate social and non-verbal cues. Although she wanted a neuropsychological evaluation due to reports of continued cognitive dysfunction (e.g., issues with memory, concentration, and disorganized thinking), neuropsychological testing was not indicated given her mental status.

Interdisciplinary Course of Treatment

Taken together, Ms. A's symptoms were consistent with post-COVID syndrome with the acute onset of new psychiatric comorbidity. She was diagnosed with post-viral dysautonomia with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), sensorimotor neuropathy, paresthesia, muscle spasms, and post-viral fatigue syndrome. Psychiatrically, her symptoms were consistent with mania of unspecified origin with possible psychotic symptoms. A multipronged treatment approach was formulated that included medication adjustment, physical therapy, psychiatric treatment, consultation with ophthalmology for continued issues with blurry vision, and follow-up consultation with pulmonology for monitoring of dyspnea. Medication adjustments consisted of a trial of gabapentin and baclofen for neuropathy, spasticity, and pain. She was continued on propranolol for stabilization of her heart rate and was switch from levalbuterol to fluticasone furoate / vilanterol. Her dosing of vitamin B6 was discontinued. A trial of olanzapine was recommended for mood, but the patient declined.

She was referred to the Functional Rehabilitation Program within the Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Health for an intensive, 5-week outpatient program known for working with complex co-occurring medical and psychiatric conditions (Orme et al., 2022). Her treatment program included psychiatry consultation, intensive individual therapy from a panel of collaborating providers, and group therapy (e.g., psychoeducational, creative arts, and experiential/process groups). Her program was tailored accordingly to allow for concurrent engagement in physical therapy and ongoing medical appointments. Treatment goals were to stabilize mood and increase physical functioning through behavioral activation. Ms. A exhibited attributes that predispose fatigue and reduced physical functioning including a tendency to overextend herself, excessive caregiving, avoidance of uncomfortable emotions, and self-hatred of perceived bodily weakness. Providers worked with her on active pacing, tolerating urges to rescue others without overextending herself, acceptance of uncomfortable emotion, and self-compassion.

Outcome

Over the course of treatment, Ms. A worked with her multidisciplinary team of medical specialists, mental health providers, and physical therapists to make small, incremental improvements across multiple domains that interacted to bring progressive symptom relief. Tachycardia was stabilized with propranolol, her pulmonary function improved, and she was able to tolerate graded exercise regimen with physical therapy including aqua aerobics. Many of her neuropsychiatric symptoms improved as well, although she reported some residual pain, spasticity, and anxiety. Although she did not take the prescribed olanzapine for mood, she was able to make use of behavioral interventions such as active pacing to increase physical functioning without incurring rebound effects of overexertion. Through individual therapy and trauma-centered song writing in music therapy, she delved into addressing trauma sequelae she thought she had processed but that continued to drive hyperfunctioning and avoidance of emotion. She had learned to take a more accepting and compassionate stance toward her physical struggles and tolerate feelings of physical weakness. She made important, real-world changes including deciding to make organizational changes at work that would relieve her of excessive responsibilities. By the end of her program on August 5, 2022, although she continued to experience neuropathic pain and muscle spasms, she was able to park her motorized scooter outside providers’ doors and walk into her appointments.

Discussion

The compounding effect of novel psychiatric symptoms, an uncertain symptom trajectory, and pervasive physical distress associated with long-COVID creates a uniquely painful circumstance of complex physical and psychological suffering. To add to the distress, the occurrence of rare multi-morbidities can make it difficult for providers to select the optimal intervention strategies with fragmented healthcare providing piece-meal, ineffective solutions. Although psychiatric comorbidity with COVID-19 is well-documented (O'Leary and Keenmon, 2023; Rogers et al., 2020), only a few case reports document mania and psychosis in patients who have recovered from COVID-19, with manic symptoms emerging up to seven days after COVID-19 recovery (Correa-Palacio et al., 2020; Haddad et al., 2021; Khatib et al., 2021; Noone et al., 2020; Shanmugam et al., 2021). There are no known cases document symptoms emerging in long-COVID patients. The case presented above highlights the profound impacts and adjustment-related distress in an otherwise healthy patient with long-COVID with the emergence of manic and possible psychotic symptoms. While acute symptoms of COVID-19 have been clarified over the past few years, the sequalae of long-COVID is a relatively novel investigation, and the confluence of overlapping psychophysiological symptoms needs more exploration.

There are multiple mechanisms that may explain the emergence of mania and psychosis in the context of long-COVID. First, mania and psychosis may occur as a side-effect of administration or withdrawal from corticosteroids (Correa-Palacio et al., 2020; Kazi and Hoque, 2021; Rogers et al., 2020). However, secondary adrenal insufficiency from steroid withdrawal occurs in approximately 1% of patients taking steroids for less than 28 days (Broersen et al., 2015) and localized skin discoloration is typically a manifestation of primary adrenal insufficiency (Pelewicz and Miśkiewicz, 2021). Moreover, the patient's interval improvement after cessation of steroids for 9 days followed by an acute decline would make this explanation less likely. Notwithstanding, corticotropin stimulation tests were not performed to rule out this possibility entirely. An additional possibility is that the patient's course of antiviral medication may have contributed to sleep disturbance, as this is a known side effect (Zareifopoulos et al., 2020). Second, her elevated pyridoxine level may have contributed to several of her neuropsychiatric symptoms, particularly ataxia, confusion, and neuropathy (Scientific Committee on Food, 2006). However, cases of clinical neuropathy generally occur after about 12 months or longer treatment with doses of 2 g/day, well above the limit in over the counter preparations (Scientific Committee on Food, 2006). As others have noted (Haddad et al., 2021; Noone et al., 2020) the onset of mania and psychosis in the context of COVID-19 may be explained by an immune system activation and neuroinflammatory processes given that inflammation has been linked to both psychosis and mania, as well as a variety of other psychiatric illnesses (Jansen van Vuren et al., 2021; Tanaka et al., 2017). Finally, psychosocial stress may have played a contributing role as considered in prior case reports of mania during COVID-19 (Haddad et al., 2021; Uvais, 2020). Precipitating pathological factors prior to acute stressful events and the rapid changes in environments may contribute to exacerbated distress. In the case of Ms. A, her life was rapidly altered from a physically and intellectually rich daily life, full of responsibilities and social roles, to one of profound disability and difficulty with basic, everyday function. It is certainly possible that multiple pathways interacted to give rise to symptoms. In particular, given Ms. A's background of childhood trauma and hyperthymic temperament, her baseline psychophysiological arousal may have been chronically elevated, which when amplified by the cardiopulmonary and inflammatory effects of COVID-19, may have created a compounding cycle of worsening physical symptoms, psychological distress, psychosocial changes, and functional impairment.

This paper raises awareness that COVID-19 and the multisystemic changes that may be the result of infection can predispose patients to rare and unexpected symptomology. The complexity of presenting symptoms calls for the need for corresponding multimodal, interdisciplinary care. In the present case, our multimodal treatment with various collaborating disciplines allowed for a patient-centered, evidence-based, individualized treatment plan with rapid updating as more information was available. Ms. A's return to everyday life, physical activity, and stable psychiatric status enabled her to reengage with her roles by provision of effective and efficient intervention.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient prior to publication.

Uncited References

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Rachael Whitehead (Academic Affairs, Houston Methodist Academic Institute) for graphic design and production.

References

- Akiskal H.S., Mallya G. Criteria for the “soft” bipolar spectrum: treatment implications. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1987;23:68–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albin R.L., Albers J.W., Greenberg H.S., Townsend J.B., Lynn R.B., Burke J.M., Alessi A.G. Acute sensory neuropathy-neuronopathy from pyridoxine overdose. Neurology. 1987;37:1729–1732. doi: 10.1212/wnl.37.11.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldessarini R.J., Vázquez G., Tondo L. Treatment of cyclothymic disorder. Commentary. Psychother Psychosom. 2011 doi: 10.1159/000322234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broersen L.H.A., Pereira A.M., Jørgensen J.O.L., Dekkers O.M. Adrenal insufficiency in corticosteroids use: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2015;100:2171–2180. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correa-Palacio A.F., Hernandez-Huerta D., Gómez-Arnau J., Loeck C., Caballero I. Affective psychosis after COVID-19 infection in a previously healthy patient: a case report. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crook H., Raza S., Nowell J., Young M., Edison P. Long covid - Mechanisms, risk factors, and management. The BMJ. 2021;374:1–18. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeisler M.É., Lane R.I., Petrosky E., Wiley J.F., Christensen A., Njai R., Weaver M.D., Robbins R., Facer-Childs E.R., Barger L.K. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, June 24–30, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2020;69:1049. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton M.J.T. Characteristics of pyridoxine overdose neuropathy syndrome. Acta Neurol Scand. 1987;76:8–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1987.tb03536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Rio C., Collins L.F., Malani P. Long-term Health Consequences of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324:1723. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.19719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo P., Benito Ballesteros A., Yeung S.P., Liu R., Saha A., Curtis L., Kaser M., Haggard M.P., Cheke L.G. COVCOG 2: Cognitive and Memory Deficits in Long COVID: A Second Publication From the COVID and Cognition Study. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022;14 doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2022.804937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad P.M., Alabdulla M., Latoo J., Iqbal Y. Delirious mania in a patient with COVID-19 pneumonia. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14:1–6. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2021-243816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain M.M., Tasnim S., Sultana A., Faizah F., Mazumder H., Zou L., McKyer E.L.J., Ahmed H.U., Ma P. Epidemiology of mental health problems in COVID-19: a review. F1000Res. 2020;9:636. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.24457.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal Y., Abdulla M.A., Albrahim S., Latoo J., Kumar R., Haddad P.M. Psychiatric presentation of patients with acute SARS-CoV-2 infection: a retrospective review of 50 consecutive patients seen by a consultation-liaison psychiatry team. BJPsych Open. 2020;6:1–5. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2020.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen van Vuren E., Steyn S.F., Brink C.B., Möller M., Viljoen F.P., Harvey B.H. The neuropsychiatric manifestations of COVID-19: Interactions with psychiatric illness and pharmacological treatment. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.111200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazi S.E., Hoque S. Acute Psychosis Following Corticosteroid Administration. Cureus. 2021 doi: 10.7759/cureus.18093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatib M.Y., Mahgoub O.B., Elzain M., Ahmed A.A., Mohamed A.S., Nashwan A.J. Managing a patient with bipolar disorder associated with COVID-19: A case report from Qatar. Clin Case Rep. 2021;9:2285–2288. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.4015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noone R., Cabassa J.A., Gardner L., Schwartz B., Alpert J.E., Gabbay V. Letter to the Editor: New onset psychosis and mania following COVID-19 infection. J Psychiatr Res. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.07.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary K.B., Keenmon C. New-Onset Psychosis in the Context of COVID-19 Infection: An Illustrative Case and Literature Review. J Acad Consult Liaison Psychiatry. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.jaclp.2023.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orme W.H., Fowler J.C., Bradshaw M.R., Carlson M., Hadden J., Daniel J., Flack J.N., Freeland D., Head J., Marder K., Weinstein B.L., Madan A. Functional Rehabilitation: An Integrated Treatment Model for Patients With Complex Physical and Psychiatric Conditions. J Psychiatr Pract. 2022;28:193–202. doi: 10.1097/PRA.0000000000000623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelewicz K., Miśkiewicz P. Glucocorticoid withdrawal—an overview on when and how to diagnose adrenal insufficiency in clinical practice. Diagnostics. 2021 doi: 10.3390/DIAGNOSTICS11040728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poyraz B.Ç., Poyraz C.A., Olgun Y., Gürel Ö., Alkan S., Özdemir Y.E., Balkan İ.İ., Karaali R. Psychiatric morbidity and protracted symptoms after COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 2021;295 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raveendran, A.V., Jayadevan, R., Sashidharan, S., 2021. Long COVID: An overview. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews 15, 869–875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2021.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rogers J.P., Chesney E., Oliver D., Pollak T.A., McGuire P., Fusar-Poli P., Zandi M.S., Lewis G., David A.S. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:611–627. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30203-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salari N., Hosseinian-Far A., Jalali R., Vaisi-Raygani A., Rasoulpoor Shna, Mohammadi M., Rasoulpoor Shabnam, Khaledi-Paveh B. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Global Health. 2020 doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scientific Committee on Food, 2006. Tolerable upper intake levels for vitamins and minerals [WWW Document]. URL https://www.efsa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/efsa_rep/blobserver_assets/ndatolerableuil.pdf (accessed 6.12.23).

- Shanmugam S., Kumar P., Carr B. Acute mania with psychotic symptom in post COVID-19 patient. BJPsych Open. 2021;7:S50–S51. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2021.182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Son C., Hegde S., Smith A., Wang X., Sasangohar F. Effects of COVID-19 on College Students’ Mental Health in the United States: Interview Survey Study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22 doi: 10.2196/21279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T., Matsuda T., Hayes L.N., Yang S., Rodriguez K., Severance E.G., Yolken R.H., Sawa A., Eaton W.W. Infection and inflammation in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Neurosci Res. 2017;115:59–63. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2016.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uvais N.A. Mania Precipitated by COVID-19 Pandemic–Related Stress. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2020;22 doi: 10.4088/PCC.20l02641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkataramani V., Winkler F. Cognitive Deficits in Long Covid-19. New England Journal of Medicine. 2022;387:1813–1815. doi: 10.1056/nejmcibr2210069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong J., Lipsitz O., Nasri F., Lui L.M.W., Gill H., Phan L., Chen-Li D., Iacobucci M., Ho R., Majeed A., McIntyre R.S. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zareifopoulos N., Lagadinou M., Karela A., Kyriakopoulou O., Velissaris D. Neuropsychiatric Effects of Antiviral Drugs. Cureus. 2020 doi: 10.7759/cureus.9536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J., Morstead T., Sin N., Klaiber P., Umberson D., Kamble S., DeLongis A. Psychological distress in North America during COVID-19: The role of pandemic-related stressors. Soc Sci Med. 2021;270 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]