Abstract

Based on a qualitative analysis of Donald Trump’s speeches and public documents from 2020, this article examines the role of xenophobia in constructing oppositional divisions within Latino groups in the United States. Rather than pitting minority ethnic/racial groups against the White majority, xenophobia frames unauthorized populations against legal, albeit subordinated, ones. Five main Latino categories are identified in this study. First, the “illegal immigrant” is portrayed as the criminal border crosser that targets other Latinos—the latter embodied by the “Hispanic victim.” Next, is the “Hispanic border patrol” agent who safeguards the United States by actively detaining and expelling undocumented immigrants. Third, the “Hispanic supporter” is welcomed into the American Dream by ascribing to meritocratic values of hard work and family values. A final actor is represented by foreign allies (e.g., Mexico’s President) who crack down their own citizens to protect the United States border. Furthermore, this article discusses Trump’s xenophobic camouflage of race (and racism) by highlighting undocumented Latinos’ alleged immoral and criminal nature rather than their physical characteristics. Concomitant to this narrative is the conditional inclusion of a subset of Hispanics into the American dream. In the conclusions, the article compares the study findings with the results of the 2020 presidential election to shed light on the growth of Trump’s Latino base. This research piece ultimately provides a contribution to our understanding of the conceptual power of xenophobia in galvanizing divergent interests within racial and ethnic minorities, in this case Latinos in the United States.

Keywords: Trump, Hispanics, Latinos, xenophobia, racism

Introduction

In September 2020, I signed up to volunteer for a phone bank organized by a handful of progressive unions in the New York metropolitan area. My colleagues and I were enlisted to reach out to Latinos in battleground states, mostly Texas and Florida, to convince them to cast their votes for Joe Biden in the upcoming Presidential election. As part of a 101 virtual training, we were tasked to remind them of then-President Trump’s appalling handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, along with the public policies that had failed Latinos amid his draconian immigration agenda.

Less than an hour into our phone marathon, I realized that the contagious optimism I had initially shared with the other volunteers was not reciprocated by a sizable number of those on the other end of the line. The social scientist in me wanted to know more about them so, for the next two and a half hours, I inquired about their motives for supporting Trump. Despite the wide variety of reasons they gave, including Trump’s purportedly conservative family values and his anti-socialist agenda, a common thread in their responses was his stand on immigration issues along with his commitment to rebounding the economy during the pandemic. They were also concerned about Biden’s potential lockdowns if he won and his alleged “open door” migration policy, which would presumably allow undocumented immigrants to continue “jumping the line” to unfairly take advantage of government handouts.

I left the phone bank convinced that there was something critical to be learned from Trump’s “rhetorical efficacy” (Schaefer 2020) in attracting disparate Latino groups during an out-of-the ordinary pandemic year. A month and a half later, the results of the 2020 Presidential Election reported an increase in Latino support for Trump at the national level. Despite his overt anti-immigrant views, he scored a record number of votes among Latino populations, particularly those without a college degree and in red states, especially Florida and Texas (Equis 2021; Garza 2021; Igielnik, Keeter, and Hartig 2021). Contrary to the portrayal of Latinos as a monolithic aggregate, recent scholarship has showed their enormous diversity, a large segment of which favored Trump in the United States Presidential elections of 2016 and 2020 (Alamillo 2019; Corral and Leal 2020; Galbraith and Callister 2020; Gonzalez-Sobrino 2020, 2021).

The trend in traditional media to frame immigration policy as Latinos’ main concern has failed to recognize not only their heterogeneity but also the array of divergent issues that set them apart (Cadava 2020; Dávila 2012). Research on Hispanic Republicans has shed light on how conservative discourses, including anti-Black Latino racism (Haywood 2017), have aligned with their paths to incorporation (Alamillo 2019; Cadava 2020; Garza 2021). With Donald Trump rising as a Presidential candidate in 2016, the United States witnessed the gradual marriage of right-wing media with the executive branch which, in due course, contributed to the polarization of the electorate (Stelter 2020; Yang and Bennett 2022). As the leading media channel, Fox News (Rupert Murdoch’s multibillion-dollar empire) exerted a significant influence on Trump and the Republican party generally (Stelter 2020). As a tour de force of unpaid advertising, Trump paired up with Fox News to forge a feedback loop of interactive propaganda through which they generated repetitively broadcast news—to the point that it eventually became unclear who was following whose lead (Ott and Dickinson 2019; Stelter 2020; Yang and Bennett 2021). At the time, reports of undocumented immigrants killing American citizens were a recurrent feature of Fox programs such as Fox and Friends. These stories were designed to instill fear and hate, particularly toward foreigners. In April 2020, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, Trump’s announcement that he would “suspend immigration,” followed by the rapid expulsion of asylum seekers under Title 42, was triggered by host Tucker Carlson’s on-air call for Trump to take a tougher stance on immigration.

Since the 2016 United States Presidential election, scholars and the general public have been fascinated by Trump’s relatively quick rise to political stardom: from media spectacle to spokesperson for a new wave of neopopulism (al Gharbi 2018; Kellner 2017). The sociological literature has been prolific in addressing the complex, even contradictory forces behind Trump’s political ascent among White and minority groups—mostly Christian and conservative. A recent body of sociological research has focused on the “Trump phenomenon” in relationship to the rise of global authoritarianism, racism, and right-wing populism (Baker, Cañarte, and Day 2018; Massey 2021; Smith 2019a). This literature has shown how the Trump administration strengthened nativism and xenophobia in the United States, greatly supported by the mainstream and social media’s amplification of his anti-immigrant agenda (Baker et al. 2018; Canizales and Vallejo 2021; Cervantes and Menjívar 2018; Louie and Viladrich 2021; Silber Mohamed and Farris 2020a).

Much of this prolific body of research has focused on Trump’s derogative images of Latino immigrants as lawless criminals (Cervantes and Menjívar 2018; Menjívar 2016; Sanchez and Gomez-Aguinaga 2017). Scholars have particularly addressed Trump’s obsession with the United States-Mexico border and his promises to finish building the wall—a physical and symbolic manifestation of apartheid and a prime symbol of ethnoracial exclusion (Heuman and González 2018; Massey 2021). Conversely, a gap still exists in the literature regarding the complex reasons behind Latino support for conservative and anti-immigrant agendas, along with the type of discourses deployed by Republican representatives to attract them. In addressing the latter, this study provides an original contribution to the sociological field of race and ethnicity by studying how xenophobic discourses that exclude “criminal Latino aliens” also grant entry to subsets of the Latino population.

By examining Presidential speeches and official documents issued in 2020, a pandemic and national election year in the United States, this article shows how xenophobia works by labeling difference: Hispanic patriots versus illegal border crossers, and defenders of national integrity versus spreaders of foreign pathogens. The choice of the year 2020 for the analysis signals the confluence of two critical phenomena: the onset of a global pandemic and a United States Presidential election year that featured the largest number of voters generally, and of Latinos particularly (Bergad and Miranda 2021). The convergence of these events offers a unique opportunity to witness Trump’s rhetorics regarding Latinos amid his divisional politics. While the pandemic prompted Trump’s refurbished xenophobic tropes (e.g., his obsession with building the wall to keep “illegals” away along with his anti-Asian rants), the impeding election increased his efforts to attract the Latino vote by relying on both inclusionary and exclusionary stances. It is precisely here, in the production of discourses, where we began this research journey.

We next turn to the notion of xenophobia, identified here as the main conceptual construct for analyzing and interpreting the study results. The methods section will then be presented, followed by the research findings that, both in their descriptive and qualitative form, reveal Trump’s conditional inclusion of legal Latino groups (i.e., called Hispanics by Trump) vis-à-vis the exclusion of undocumented Latino immigrants—including asylum seekers. The study results will highlight the main Latino actors identified in Trump’s public speeches and documents, in conversation with central dimensions of his xenophobic construct. Against the image of the “illegal criminal,” Trump’s preferred Latinos are portrayed as industrious legal immigrants fully committed to defending the nation against undocumented trespassers. In Trump’s narrative, the former are represented by four distinct but intertwining categories: the Border Patrol agent, the Hispanic supporter, the victim of crimes perpetrated by “illegal aliens,” and Latin American heads of state aligned with Trump’s national security doctrine. The discussion section will review these findings in dialogue with the scholarly literature and, in the conclusions, this piece will provide a comparison between the study results and the outcomes of the 2020 Presidential election toward shedding light on the growth of Trump’s Latino base.

Conceptual Framework: Deconstructing Xenophobia During Trumpist Times

Xenophobia (etymologically xénos, meaning “stranger” and phóbos, meaning “fear”) is generally conceptualized as apprehension and hatred directed to those considered alien to one’s cultural identity or nationality. Although this term tends to be used and juxtaposed with others such as nativism and racism, an understanding of their differences is key to better conceptualizing their respective reach and impact (Kim and Sundstrom 2014; Saito 2021; Sundstrom 2013). Despite being semantically related, racism and xenophobia are not the same, as the latter entails the racialization of those excluded from the national polity—even if they belong to it (Saito 2021). More pervasively complex than binary racist dimensions (i.e., White and Black) xenophobia requires the exclusion of the “other” in an in-group versus out-group dichotomy (Baker et al. 2018; Wimmer 1997).

The differences between racism and xenophobia can also be understood in terms of hierarchization as racism implies the tiering of out-groups, while xenophobia identifies an out-group response without rankings (Wimmer 1997). While open racism is not generally accepted, xenophobic rejection of the other tends to galvanize the nation against the divisions promoted by internal racism (Saito 2021). Unlike nativism, xenophobia is not linked to the nation-state since racial/ethnic groups may express xenophobic claims without conveying nativist connotations. An example would be the case of nationless, nomadic populations that may act upon out-group rivalries against other tribes—while xenophobic, these reactions do not involve nativist claims (Baker et al. 2018; Sundstrom 2013). Furthermore, nativism denotes the preference for, and privileges granted to, the native-born population, while xenophobia conveys the rejection of the foreign born that are presumably antagonistic to the nation’s moral principles (Fernandez 2013).

Recent scholarship has highlighted the contribution of German political theorist Carl Schmitt to the conceptualization of the “other” in the development of modern xenophobia amid national populism, islamophobia, White nationalism, and its sister movements in Europe (Henley and Warren 2020; Mannarini and Salvatore 2020; Marin 2016; Sundstrom 2013). As noted by L. Marin (2016), even if Schmitt’s theories do not directly translate into racism or chauvinism, his community-based politics is reliant on the exclusion of the other(s) and “leads directly to xenophobia as an unavoidable result of the political” (p. 312). In The Concept of the Political (Schmitt 2007), originally written in 1927, Schmitt argues that state sovereignty is dependent on the identification of public enemies: strangers who are not necessarily foreign and can be anyone, such as a religious group, a political party, a sexual or racial minority. What becomes politically relevant for Schmitt is the public construction of the enmity itself, which finds its counterpoint in a homogeneous nation. In this view, the opposition between “friend and enemy” is crucial in mobilizing mass support and a sine qua non condition for the existence of a united nation.

As will be shown in this article, the xenophobic construction of the “ally/enemy” involves a more complex toolbox than Schmitt’s binary distinctions, in which racism is masked as foreignness of both newcomers and racialized minorities (i.e., the perennial foreigner). As a twofold process, “othering” is directly rooted in racism (i.e., perceptions of White racial superiority) and xenophobia (i.e., fear/hatred of foreigners). Rhetorical constructions of “othering,” leading to stigmatizing discourses and practices, have largely informed Latinos’ experiences of exclusion (Cervantes and Menjívar 2018; Chavez 2013; Lamont, Park, and Ayala-Hurtado 2017; Menjívar 2016). Likewise, the distinction between xenophobia and racism should not preclude us from assessing their interdependence. Racist xenophobia is rampant, particularly in the developed world, as it is mostly people of color who are excluded and demonized. In a related framework, racist nativism—or the racialized framing of noncitizens as threats—is also key to understanding United States racial hierarchies (Huber et al. 2008; Louie and Viladrich 2021). Xenophobia and racism also share common ground in the reproduction of exclusion and dominance. Whereas racism focuses on physical characteristics to target purportedly inferior groups, xenophobia rejects those perceived as foreigners—even if members of the same community (Wistrich 2013).

Rooted in racist xenophobia, the “perennial foreigner” and “alien citizen” stigma are applied to those who, although legally belonging to the nation-state, are perceived as strangers who live among us (Kim and Sundstrom 2014; Ngai 2014). Likewise, the notion of alien citizenship directly speaks to a judicial field that both grants and removes legal rights. Two examples of this phenomenon are the expulsion of thousands of ethnic Mexicans during the Great Depression, and the internment of United States citizens of Japanese origin during the Second World War (Ngai 2014). Similarly, concerns about “illegal aliens” during Trump’s presidency led to lawmaking efforts to strip birthright citizenship from immigrants seen as unworthy of it. Trump’s diatribe against “anchor babies” was directed at removing citizenship rights from the children of noncitizens born in the United States, under the assumption that their mothers had given birth in this country for personal gain and at the expense of American taxpayers (Foster 2017). During the last year of his presidency, Trump’s xenophobic narrative was clearly seen in his vilification of Asian communities, especially in his framing of COVID-19 as the “Chinese virus” and the “Kung fu virus.” Research has shown how such xenophobic rhetoric led to racial and ethnic hate as well as verbal and physical violence against Asian populations in the United States and overseas (Gover, Harper, and Langton 2020; Louie and Viladrich 2021; Viladrich 2021).

Rather than rejecting the “other” on the basis of skin color or other phenotypical characteristics, xenophobia focuses on foreigners’ nonvisible traits—including their alleged (im)moral and deviant features—as the rationale for expelling them from the nation-state. Hence, xenophobia offers a channel for covert racism to express itself under the guise of protecting the public from immigrants’ unlawful and unethical mores. For instance, the scorn directed against Muslims by Islamophobes, rather than being rooted in race, is justified on the basis of Islam’s alleged incompatibility with Western cultural values and democratic principles (Baker et al. 2018; Sundstrom 2013).

N. T. Saito (2021) argues that xenophobia—in its shaping of a foreign population as a threat—achieves what racism cannot: it allows the latter to spread its wings by camouflaging racial contempt as fear of those who allegedly bring deadly pathogens and moral turpitude. As will be discussed in this article, using taxpayer dollars to build an astronomically expensive border wall is justified by invoking the hordes of Latin American invaders that must be stopped. Neither weak nor innocent, the latter are portrayed as morally inferior and tenacious adversaries always ready to attack.

Research Design and Methods

This article is based on the qualitative content analysis of former President Trump’s speeches, press briefings, and official documents released during the year 2020. This period, known as “the great coronavirus pandemic year” (Gostin 2020) offers a unique opportunity to understand how the 45th United States President navigated a public health crisis of unprecedented proportions by labeling particular immigrant groups as either allies or “virus vectors.” An analysis of Trump and his public statements allows us to tap into a first-order production of public messages (Petroff, Viladrich, and Parella 2021). Trump’s speeches, official statements, and press releases were culled from two main repositories: the Whitehouse archive (https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/) which is the official website of the United States presidency, and the American Presidency Project (https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/), a free online university-based database for public Presidential documents hosted by the University of California at Santa Barbara. A third source, NEXIS Uni (and academic database engine), was accessed through the University’s online library to further identify any of Trump’s public appearances (e.g., roundtables) that might have been missed by the other web resources.

The following Boolean terms, in alphabetical order, were used in conducting the searches (separately and combined): “Hispanic/s,” “illegal/s,” “immigrant/s,” “Latino/s,” “Latin-American migrants,” “migrants,” “President Trump,” “Trump,” “undocumented,” and “US/United States President.” The main selection criteria for gathering the documents were that former President Trump was the prime speaker at official, government-sponsored events, or the author and/or signatory of official documents, as in the case of White House press releases. This project did not consider entries from his social media feeds, about which much research has already been conducted. For the sake of consistency, this study only included transcripts and records that explicitly addressed Hispanics/Latinos in the United States, either by referring to them directly (i.e., mentions of Hispanic Americans) or indirectly, as when Trumps used the terms “illegals” or “Mexicans,” which implicitly referred to undocumented Latin American immigrants.

An initial search led to 112 records divided among speeches, official White House statements, and press releases. After eliminating duplicate transcripts, 89 items were left in the final corpus. Three types of in-person events were included: rallies (i.e., mass demonstrations of Trump supporters), spoken addresses (i.e., formal speeches and press briefings), and roundtables. The latter refers to semi-informal settings during which Trump sat down with other speakers (e.g., Latinos for Trump roundtables) to share his experiences and hear the attendees’ personal and political trajectory.

Each document was uploaded to Dedoose, a web-based application utilized for qualitative and mixed-methods analysis (Dedoose 2021). The analysis followed a constructivist and inductive approach, which, in agreement with grounded theory principles, required the texts to be read several times for the purpose of identifying themes and common narratives throughout the corpus (Glaser and Strauss 2017). In a second stage, codes (i.e., empirical indicators of conceptual categories) were created and applied during text analysis—a process called “code mapping” (Gonzalez 2016). For instance, references to Latinos’ role in Border Patrol units were classified under the code “Patriotic Duty,” and tropes indicating the alleged criminality of “illegal trespassers” were labeled under the “Criminal Aliens” code. A codebook was created to categorize the selected excerpts (i.e., phrases, quotes, and passages from speeches), which were then entered in Dedoose and linked to each code. The analysis resulted in 22 codes and 314 coded excerpts across five distinct thematic categories: Hispanic Supporters (98), Latin American Allies (45), Border Security/National Security (78), and Illegal Aliens (93). Identifiers for each of the recorded materials were then entered and classified according to type of document (i.e., rally, roundtable, press release), target audience (e.g., Hispanic supporters), place where the speech/document took place or was released (e.g., the White House), and date (i.e., month and day in the year 2020).

Research Findings

Descriptive Results

Table 1 disaggregates the documents according to their specific type. Trump’s preference for in-person events is reflected in the fact that this category accounted for approximately 65 percent of the materials (N = 58) versus 35 percent of his official written documents (N = 31).

Table 1.

Documents Analyzed by Type.

| Document/Event Type | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Briefing and spoken Addresses | 29 |

| Press release and White House statements | 31 |

| Rally | 24 |

| Roundtable | 5 |

| Total | 89 |

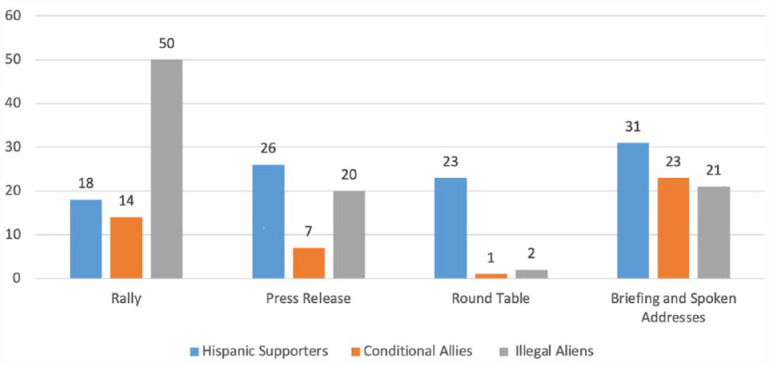

Graph 1 illustrates the distribution of the population categories that appeared in the coded excerpts across the documents (i.e., Hispanic Supporters, Conditional Allies, and Illegal Alliens). As shown in this figure, Trump’s rants about “illegal alliens” were most apparent during his rallies (i.e., MAGA events) when he typically stirred his base against “criminals” crossing the United States-Mexican border. Conversely, his references to Hispanic supporters were more marked during the roundtables, which were mostly organized by his Latino followers (i.e., Latinos for Trump), and spoken addresses (i.e., campaign events), in which his target audience included the general Latino population. The third population category (Latin American heads of state as conditional allies) appears consistently across all documents, signaling these countries’ support for Trump’s national security doctrine.

Graph 1.

Population categories across excerpts by document type.

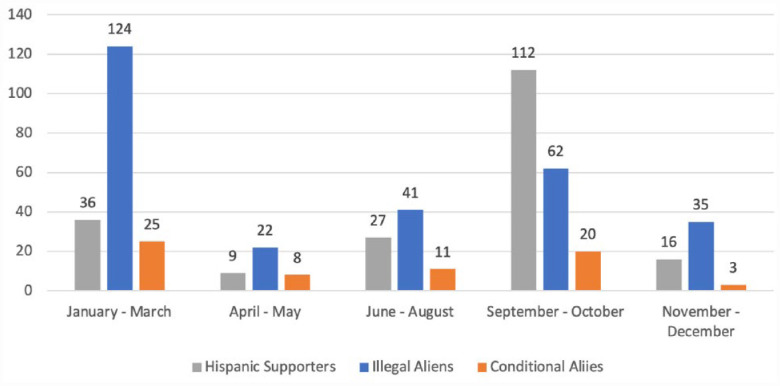

Graph 2 presents the number of excerpts associated with each population category that appeared in the corpus during 2020. The figure of the “illegal alien” was most prominent during the first three-month period of 2020. Meanwhile, Trump’s calls to his “Hispanic supporters” peaked in September and October, close to the end of the campaign period, and decreased noticeably after the United States Presidential election in November 2020.

Graph 2.

Distribution of population categories by month.

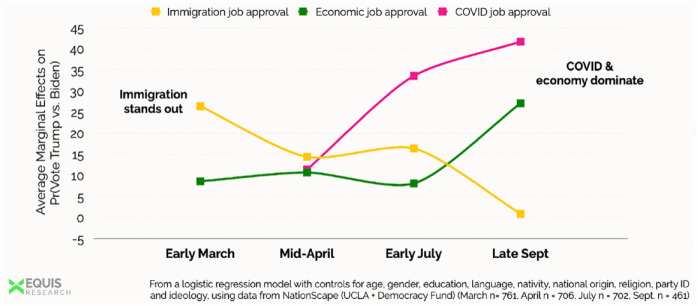

We compared Graph 2 with poll data presented in Graph 3 (taken from Equis 2021) that shows Latinos’ approval of Trump on major issue areas and found striking correlations between the two.

Graph 3.

Average marginal effects on the probability of voting for Trump (vs. Biden) on major issue areas, among all Hispanics.

As per Graph 3, in early March 2020, Trump’s immigration agenda—led by his calls to close the border and prevent “illegals” from crossing it—earned the highest approval among his Latino sympathizers. As the pandemic progressed, Trump’s Latino support increased with regard to his handling of the COVID-19 pandemic and the economy (i.e., his efforts to reopen businesses and raise employment levels, along with his government’s financial stimulus). According to post-election results, Trump emphasis on the latter explained his uptick among Latinos in the 2020 Presidential Election (Equis 2021). As will be discussed later, Trump asked his Hispanic supporters to keep the economy open during COVID-19, as he pledged to protect both their financial stability and, ultimately, their entry into the American Dream.

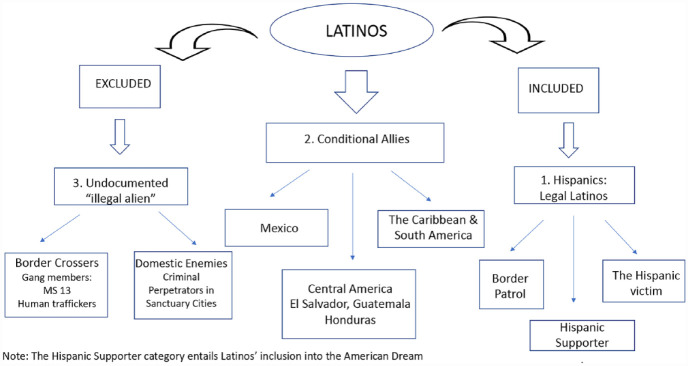

Finally, Graph 4 brings together the conceptualization of the categories presented above by introducing the study’s framework: “Xenophobic Conceptualization of Latinos in the United States” On the right of the graph, the term “Hispanics” (i.e., legal Latino immigrants and their families) represents the “included” population and is divided into three categories: the “Hispanic Border Patrol agent”; the “Hispanic supporter,” who is given access to the American Dream; and the “Hispanic victim” of crimes perpetrated by “illegal aliens.” Trump’s conditional allies, in the center of the graph, are epitomized by Latin American countries (and their representatives) who supported Trump in his fight against “illegal immigration.” Finally, the category of “excluded” Latin Americans, on the left of the graph, is divided into two groups: “Border crossers” (i.e., the MS-13 gang, drug traffickers) and “domestic enemies”—undocumented immigrants protected by sanctuary city laws. We now turn to analyzing the qualitative meaning of the findings drawn from these main population categories.

Graph 4.

Xenophobic conceptualization of Latinos in the United States.

Hispanics at the Border: Exposé of the Unfailing Surveillant

During the final year of his presidency, Trump’s promise to complete the United States-Mexican border wall became one of his main battle cries, and he consistently encouraged his base to engage with the “build the wall” chant—all amid the largest public health crisis in the United States in more than a century. Meanwhile, he oscillated between minimizing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and denying it altogether, such as when calling it a Democratic “hoax,” or blaming China and Latino border crossers for its spread. Trump’s keen maneuvering of divisional politics achieved its maximum expression when framing the southern wall as his own persona, while praising Hispanic Americans for being vigilant against the nation’s enemies—namely Latino “trespassers.” During a “Latinos for Trump Roundtable” in Las Vegas (on September 25, 2020) he stated,

I’m a wall between the American Dream and—and chaos and—and a horror show, a horror show. It would be very bad. It would be very bad. Many Latino and Hispanic Americans came here to pursue the American Dream, having left countries that really had a very, very unruly group of people. You know, we’re throwing out MS-13 all the time . . . But they’re rough. They’re bad. And they’re bad people . . . They’re bad people, and we throw thousands and thousands out of our country. And if we didn’t have ICE and these people [Hispanic American Border Patrol officers] you would be living in real fear and real problems.

A few key findings transpire from the excerpt above. First, Trump’s “wall” is continuously invoked as reassurance of the physical and symbolic barrier that will stop “illegal” Latin Americans from entering the United States. The wall as a protective fortification of the nation-state is a classic example of xenophobic language that claims to be in favor of racial integration while simultaneously denigrating specific racial/ethnic groups—not based on their phenotypic markers but on their alleged incompatibility with American values. Trump’s bombastic manner of speech was more palpable during his public appearances than in his written documents and was aimed to rile up his base—both White people and members of ethnic minorities. As noted by Hirschfeld David and Baker (2019), Trump’s advisors ingeniously produced the “build the wall” chant to enthuse his supporters whenever they seemed disengaged. Trump’s wall also speaks to the notion of the sovereign ruler who will not hesitate to use an iron fist to save his nation, as described by C. Schmitt (2007) early on.

Trump’s praise of Hispanic Border Patrol agents—who keep the “bad hombre” away—is also consistent across all his in-person appearances. Public assertions of rising immigrant criminality are a sine qua non condition for framing the Hispanic protector, whose main duty is to defend the physical and symbolic boundaries of the nation. Trump repeatedly reminded his followers of the large number of Hispanics serving in the Border Patrol and military and claimed that they understood and wanted to protect the southern border more than anyone. During a rally in Yuma, Arizona (August 18, 2020), he referred to them as “heroes that protect our nation in uniform.”

That includes the millions of incredible Hispanic Americans who follow our laws, uplift our community [applause] and protect our nation, in uniform. Half of all Border Patrol agents are Hispanic Americans; I was just with them. And today I salute each and every one of those true American heroes and that’s what they are. [Applause]. And you know nobody understands the border better than Hispanics. They know what’s well, what’s bad. They don’t want bad people coming into our country, taking their jobs, taking their homes, causing crime. Hispanic Americans are the people that are most in favor of what we’re doing on the border because they understand it. They understand it better than anybody. With the help of these patriots, we’ve stopped the rampant asylum fraud, shut down the human smugglers and we’re finding the drug dealers, traffickers, predators, and we’re throwing them the hell in jail or sending them back home. [Applause].

The recruitment of Border Patrol agents among people of color has been a longstanding tactic to assure compliance on the part of subaltern groups to help build a unified political façade. In fact, minorities have historically been the first to be called to the front during armed conflicts (Buckley 2002; Saito 2021). The reiterated convocation of a powerful enemy is also needed to feed an expensive technocratic military apparatus able to defend the country against it. Finally, the construction of the “illegal other” keeps Hispanics’ demands in check by diverting attention from domestic issues, including racial and social inequality, all while devising a common enemy that is blamed for the nation’s woes (Saito 2021).

Promises of Whiteness: Hispanics Joining the American Dream

I’ve achieved more for the Hispanic Americans. And think of it, I’ve achieved more for Hispanic Americans in 47 months than Joe Biden has achieved in 47 years. I’ve been here for 47 months.

Donald Trump, Latinos for Trump Roundtable, Florida, September 25, 2020.

In Trump’s view, Hispanics are committed stakeholders that have prospered under his leadership and will continue to do so. Due to their proven Americanness, they are welcomed into the American Dream—a reward for their commitment to protecting and investing in the nation-state. During a White House event honoring veterans of the Bay of Pigs Invasion (September 23, 2020), the former President remarked,

Hispanic Americans embody the American Dream. And my administration is delivering for you that American Dream like nobody has ever delivered for the Hispanic Americans and, hopefully, for everybody else. We implemented the historic tax cuts, regulation cuts, and I recently created the Hispanic Prosperity Initiative to expand economic opportunity.

At the height of the pandemic and closer to the 2020 election, Trump’s speeches increasingly switched from his anti-immigrant stand to prioritizing his rebounding of the United States economy. This was paired with his praising Hispanics for their individual enterprise and hard work as their entry ticket to the American Dream. Promising the latter has been a political strategy of the Republican Party since Reagan (Sosa 2009). Trump’s extension of the American Dream to eligible Hispanics is also in tune with the latter’s aspiration for whiteness supported by their meritocratic achievements (Filindra and Kolbe 2022; Hochschild 1995).

Research has consistently pointed out the association between becoming American and achieving whiteness, on one hand, and seeking inclusion into the American Dream and embracing the larger White majority, on the other (Basler 2008; Menjívar 2016). Basler’s study (2008) revealed how Mexican American respondents aligned themselves with Whites (against Blacks) for the sake of gaining the latter’s social and political capital. By identifying as White, Basler’ participants channeled their demand for validation and protective inclusion into an imagined American community.

Trump’s promises to improve Latinos’ financial prospects during COVID-19, while taking credit for their pre-pandemic success, became a staple of his public speeches. On July 9, 2020, he signed an executive order, the Hispanic Prosperity Initiative, which promised to expand jobs and educational opportunities for Latinos. Once again, he deflected blame for the United States health crisis by referring to the pandemic as the “Chinese virus” and promised to reopen the economy as soon as possible to return Hispanics to their pre-pandemic employment levels.

The Hispanic Americans and the Hispanic American community is a treasure. Thank you. . . . Before the plague from China came in—you know what that is; that’s the China virus—before it came in and hit us, we achieved the lowest Hispanic American unemployment rate and the lowest poverty rate ever recorded—history of our country—ever recorded. And we’re getting back to it very quickly. We achieved the highest ever incomes for Hispanic Americans and many other American groups and communities.

At a rally held in Henderson, Nevada (September 13, 2020), the former President celebrated his economic achievements on behalf of his Hispanic supporters, while reminding them of their role in keeping “criminals from coming across” the border.

For the last four years, I’ve been delivering for our incredible Hispanic community; I’m fighting for school choice, safe neighborhoods, low taxes, low regulations on all Hispanic-owned small business, and they are great businesspeople. And they understood that. . . . Our Hispanic population knows our southern border better than anybody else and they don’t want criminals coming across. They want people to come across, but they want them to come across legally. And we have the strongest southern border now that we’ve ever had. [Cheers and applause].

Hispanics, as constructed in Trump’s narrative, are fierce individual entrepreneurs, defenders of the Second Amendment and advocates of heterosexual, religious, and anti-abortion family values—as an extension of the ideal Trumpist worker, they could be labeled as “rugged meritocrats” (Cech 2017). Still, Trump’s rhetorical investment in his Hispanic supporters was dependent on their proven support and patriotism in the fight against “illegal trespassers.”

Framing the Internal Enemy: Hispanic Victims Versus Illegal Perpetrators

During his Presidential campaign, Trump made explicit references to the horrific killings of American citizens at the hands of “criminal aliens” and blamed sanctuary cities—municipalities that protect undocumented immigrants from Homeland Security—for providing cover to illegal outsiders. These stories typically highlighted the murders perpetrated by those unlawfully residing in United States territory. Contrary to empirical evidence (Collingwood and O’Brien 2019), Trump framed sanctuary cities, such as San Francisco and New York, as magnets for undocumented immigrants who were allegedly responsible for these cities’ high crime rates. At an event organized by the Members of the National Border Patrol Council (February 14, 2020), Trump detailed the horrific rape and murder of a 92-year-old Hispanic woman, Maria Fuentes, at the hands of an “illegal criminal”:

In my State of the Union Address, I shared the tragic story of Maria Fuertes, a 92-year-old great-grandmother who was allegedly raped, beaten, and murdered by a criminal illegal alien in New York City. I think I can—no, I don’t think—I’ll take the word “allegedly” out. She was raped, beaten, and murdered. Only five weeks before the murder, the criminal alien had been arrested for assault. ICE asked for the criminal to be turned over but, instead, he was released under New York City’s sanctuary laws. If New York had simply honored ICE’s detainer request—very simple thing to do—Maria Fuertes could be with her family right now. And we’re deeply moved to be joined this afternoon by Maria’s grieving granddaughter, Daria. Where is Daria? Daria Ortiz. Daria. Please come up, Daria. Please. Daria is joined by her beautiful five-year-old son. Thank you, Daria. It’s a great honor!

During his first Presidential campaign, Trump began calling mothers and families whose children had lost their lives to undocumented immigrants “Angel moms” and “Angel families.” After his election, this group became an informal “think tank” that supported his claims that unauthorized immigrants were on a killing spree of innocent Americans. Fox and other pro-Trump think tanks, such as America First Policies, helped amplify the plight of Angel moms along with Trump’s crusade to build the wall and keep “illegals” at bay (Fearnow 2019).

On October 20, just a few weeks before the United States Presidential election, the Trump Administration released a document titled “National Day of Remembrance for Americans Killed by Illegal Aliens,” which commemorated those whose lives had been “egregiously taken from us by criminal illegal aliens.” Trump promised to prevent similar crimes and seek justice on behalf of the victims. In 2014, Mary Ann Mendoza’s son, Hispanic Sergeant Brandon Mendoza, died in a car collision with an undocumented immigrant. During a “Students for Trump Rally” in Phoenix, Arizona (June 23, 2020) Trump referred to Ms. Mendoza, who later became a prime spokesperson for the Angel Moms, as follows:

I also want to recognize a truly courageous woman, “angel mom”—she’s a friend of mine too, by the way. One of the first people I met when I announced I was going to run. What she has gone through with illegal immigration, nobody will ever go through. Hopefully, nobody ever has to go through. And she lost a magnificent child to an illegal immigrant. And it’s just a horrible thing. And she spent her life—she spent the last long period of years fighting and fighting and fighting. And people have gotten to respect her greatly: Mary Ann Mendoza, wherever you might be. A lot of guts. She’s got a lot of guts.

The discursive efficacy of anti-immigrant narratives achieves new heights when the foreign invader makes other Latinos a prime target. Not only is xenophobia here deployed to camouflage racism by endowing “the other” with essential immoral traits, but it also offers the tools for its internalization among specific Hispanic groups. The trope of the “enemy within” highlights the wrongdoings of outsiders who, rather than being detained at the border as they should have been, get a free ride to sanctuary cities to “kill our children.” Finally, the dual-frame illegal criminal-Hispanic victim puts into evidence how the notions of the external and internal enemy become entangled into one single entity: a border trespasser that metamorphoses into a sanctuary city’s illegal refugee.

Conditional Allies in Defense of the Nation-state

Devised to recruit support for his reelection campaign, Trump’s initial promise that Mexico would pay for the southern border wall continued throughout 2020. Meanwhile, he did succeed in erecting what it has been called an “invisible legal wall” (Smith 2019b) represented by the Third Country Transit Bar—his version of an anti-asylum agreement that he signed with Central America’s Northern Triangle countries (El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala). Never using the term asylum petitioners, Trump consistently called them “illegal criminals” and “gang members” as at a rally in Milwaukee, Wisconsin (January 14, 2020):

We are removing these illegal criminals and gang members by the tens of thousands, and we will not let them back. And we made a deal with Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Mexico, where they accept them back. Under the Obama administration, they’d get them, they’d bring ’em back. And Honduras and Guatemala, would say “go to hell—we’re not taking them back.” But with us, they take ’em back. They take ’em back. [Applause]. Very great!

In the meantime, the Mexican Government had agreed to deploy their troops to help stop migrants from entering the United States, in return for preventing sanctions that would otherwise force Mexico to pay additional tariffs on its exports and remittances. Mexican President López Obrador became a prime actor in this discursive repertoire by endorsing additional bilateral agreements, including the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) known as the “Remain in Mexico” program. Under the MPP, asylum seekers were ordered to wait in Mexico until their court date was set in the United States Lack of legal counsel, plus the financial and physical insecurity of waiting at border towns, made it almost impossible for asylum seekers to win their cases (American Immigration Council 2021). At a Rally in Yuma, Arizona (August 18, 2020), Trump praised the Mexican President for his backing of the MPP as follows:

I entered into a historic partnership with Mexico, known as the migrant protection protocols, to safely return asylum seekers to Mexico, while awaiting hearings in the United States. You know about that [in the past] we had to have them in the United States, and we captured them, we had to keep him here. I said: “No, no, we don’t want them here, we want them outside.” We got sued all over the place and we won. So now they don’t come into the United States, they can wait outside.”

Trump’s references to his “love affair” with Mexico was evident in his frequent praising of López Obrador for having joined forces to protect the United States-Mexico border, as reported at a “Keep America Great Again Rally” in Iowa (January 30, 2020):

Right now, we have a love affair with Mexico because the Democrats, the Democrats wouldn’t give us what we needed and I got Mexico, they’re great. They put up 27,000 soldiers on our southern border and the numbers are plummeting, 87% down [cheers and applause]. So, the President of Mexico is doing a great job.

Trump’s ability to turn enemies into allies, and vice versa, fits well into tropes that forge conditional coalitions toward protecting the nation-state. The narrative of Mexicans as enemies, which predominated during Trump’s first Presidential run, was gradually replaced by the portrayal of “Mexico as an ally,” particularly during his reelection campaign. Close to the end of his mandate, he needed to reinforce the reach and impact of his early pledges (i.e., “illegals will be sent back to where they came from”). To that end, he used the same xenophobic framework of inclusion/exclusion, with which he had skillfully contraposed the Hispanic versus the undocumented Latino immigrant, for his Mexican and Central American associates. Still, while the latter became his conditional partners, their citizens and their countries’ asylum seekers continued to be portrayed as enemies of the United States.

Discussion: The Coupled Effect Of Xenophobia

This article inquired about former President Trump’s rhetorics of inclusion/exclusion with respect to subordinate groups, Latinos in this case. By relying on xenophobia as the main conceptual framework (see Graph 4), this study examined Trump’s public messages designed to attract the Latino vote during an extraordinary pandemic and election year. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine how Trump’s xenophobia served his aim to embrace his Latino sympathizers (i.e., the deserver of the American Dream, the defender of the nation-state, and the victim of the illegal immigrant) for the sake of upholding to United States racial and ethnic hierarchies.

These findings have shown how xenophobia simultaneously ostracizes certain groups while embracing others—even if conditionally. Building on Schmitt’s “friend versus enemy” distinction, xenophobia draws an imaginary “us” against the “other” and, under Trump’s presidency, it galvanized a sector of his Latino electorate for a common crusade against an external enemy—the “illegal trespasser” who settles among us—which simultaneously includes carriers of the “Kung Fu virus,” the immigrant freeloader, and the gang member/drug dealer.

A discussion of our main findings regarding Trump’s use of xenophobia in engaging the Latino electorate is in order. First, Trump’s skillful camouflaging of race, the enemy is both colorless and shapeless, is systematically deployed in his refusal to name and personalize undocumented immigrants. In all his documents and public appearances, those crossing the border from Mexico are “faceless,” with no other identity than that associated with their criminal record—typically they are drug traffickers/human smugglers and/or gang members. Trump continuously reminded his audiences of the nonvisible characteristics that make “the other” ineligible for citizenship, including the deviant features of the MS-13 border crosser and the illegal felon protected by sanctuary city laws.

In line with our findings, the literature shows that while racism rests on specific phenotypical features to justify domination, xenophobia subjugates those with alleged essential immoral traits (Chiricos, Welch, and Gertz 2004; Saito 2021; Wistrich 2013). And while open racism is not generally accepted, rejection of the other (framed as a threat) is celebrated (Saito 2021). Trump’s “cloaked racism” is conspicuously illustrated in his popular self-laudatory claim: “I am the least racist person there is anywhere in the world,” as he railed against Mexican immigrants and Muslims—not on the basis of their phenotypical characteristics but on their presumed criminal nature and deviant behaviors (Kelly 2020; McIntosh and Mendoza-Denton 2020). By stressing cultural and moral difference rather than racial characteristics, xenophobia provides a screen for White supremacy as United States citizens are now contrasted against those who are deemed essentially and perennially foreign. While this phenomenon is nothing new, this was the first time that a President made the nation-state and the Republican Party openly subservient to the principles of White supremacy (Massey 2021).

Second, the figure of the “illegal alien” is depicted as a powerful threat to both the White-majority and subaltern groups (i.e., the image of the Hispanic victim). Protected by sanctuary cities, the illegal immigrant not only invades the national polity but also remains among us. Therefore, the full investment of the nation-state is required to keep him in check—in Trump’s narratives, “border invaders” are consistently male. In line with our findings, studies on the Latino threat narrative point to the public construction of “the brown threat,” shared with other groups such as Middle Eastern immigrants, who allegedly bring crime and moral turpitude and are therefore underserving of the American Dream (Chavez 2013; Rivera 2014). This rhetoric has been fueled by claims that the greatness of the United States has been threatened by the invasion of illegal workers, from Mexico and other Latin American countries, who steal jobs from legitimate American citizens and commit crimes against them (Hinojosa-Ojeda and Telles 2021).

Third, to be effective, xenophobia must grant the right to inclusion to particular subsets of subaltern groups. Rather than counterposing specific ethnic/racial groups against the White majority, xenophobia frames an illegitimate minority against a legal, albeit subordinated, one. Trump constructed a homogeneous Hispanic minority that is welcomed into the American Dream and respected for its hard work and family values. Contrary to unidentified “illegal immigrants,” Trump typically called his Hispanic supporters by their first and last names (e.g., Jorge or Martinez), and told poignant stories about their struggles and paths to success. This concords with the media literature that shows that naming individuals and recounting their personal trajectories is an effective tool to forge empathy and identification with public audiences (Petroff et al. 2021; Viladrich 2019). Still, as a reminder of Latinos’ perennial foreigner status, Trump made sure to frame a distance effect between a “we/us” (i.e., White patriots, Americans) and “them” (i.e., Hispanics). In this view, the plurals “they” and “them” work to stress the discrepancies between the White majority and a seemingly homogeneous Latino aggregate (Schneider and McClure 2020).

Fourth, although Trump’s speeches made quite explicit his political support for Hispanics, their status as included had to be earned. As discussed in this article, the figure of the “Hispanic Border Patrol agent” is subjected to a patriotic scrutiny that grants Latinos provisional inclusion in exchange for their unconditional commitment to protecting the nation. Every time Trump praised Hispanics for their value and contributions to America’s grandeur, he reminded them of their inescapable duty to reject “illegals” and defend the homeland—a symbolic entry fee for joining the American Dream and becoming “honorary whites” (Bonilla-Silva 2004). Finally, Trump’s welcoming of representatives from some Latin American countries, as conditional foreign allies, was dependent on their endorsement of American’s racial-ethnic status quo: Mexicans paying for the wall, and Guatemalans and Salvadorans persecuting their own kind and bringing their deported nationals back home.

Trump’s speeches ultimately conveyed a binary distinction between those non-Whites that are conditionally welcomed into the national polity (i.e., the Hispanic supporter and the Border Patrol agent) and those excluded from it (i.e., the illegal immigrant) due to their cultural and moral incongruency with United States values. Last, Trump’s keen maneuvering of divisional politics achieved its maximum expression when praising his allies, internal and external, for being vigilant against the nation’s enemies—namely, Latino trespassers.

In its next and final section, this article draws some parallels between the study findings and Trump’s growth among the Latino electorate in 2020 toward envisioning new areas of sociological research.

Conclusion: The Day After The 2020 Presidential Election

This article began with a vignette recounting the author’s personal realization of Trump’s inroads among Latinos just before the United States 2020 Presidential Election. Fast forward a few years, and there is now little doubt that one of the major surprises of that election was his receiving roughly 38 percent of the Latino electorate—one of the highest shares of the Latino vote for the Republican Party in history (Igielnik et al. 2021). The former President outperformed himself, with a 10-point gain among Latinos from 2016 to 2020 (Equis 2021; Igielnik et al. 2021). Latinos’ support for Trump grew particularly in states like Texas (where he received 41 percent of the Latino vote) and Florida (45 percent), the latter not only due to the endorsement of Cubans but of LatAms, particularly in South Florida, a group that includes people from a variety of Latin American countries, such as Venezuela (Equis 2021).

Scholars and policy analysts are still debating the reasons for Trump’s Latino uptick during the 2020 election. Post-election research suggests that Trump and the GOP actively campaigned for the Latino vote and made gains that cut across geography and nationality, crafting messages that resonated well with specific segments of the electorate—even if for different reasons (Equis 2021; Ocampo, Garcia-Rios, and Gutierrez 2021; Robb 2022). This phenomenon has also been credited to the relentless pro-Trump propaganda broadcast by right-wing outlets (i.e., Fox News) along with the active social media messages (i.e., WhatsApp, YouTube, and Twitter) featuring Trump, his followers, and think tanks such as “Latinos for Trump” (Louie and Viladrich 2021; Robb 2022).

Although this study focused on the production of Trump’s discourses, and not its effects, some key parallels can be drawn between our findings and the results of the 2020 election. As suggested in the framing of the “Hispanic supporter,” studies have shown that Trump attracted Hispanic entrepreneurs (i.e., the “Goya type”) who ascribed to pro-family and meritocratic ideals of upward mobility, along with their deep distrust in government intervention and taxes (Garza 2021; Robb 2022).

Almost counterintuitively, the economic downturn during COVID-19 allowed Trump to highlight his promise to keep the economy open—a message that resonated strongly among his Latino voters—even as immigration issues became less important. Furthermore, Biden’s cautious approach toward the pandemic left room for Trump to court the Latino electorate (Equis 2021; Ocampo et al. 2021). Trump’s Latinos, many of whom had experienced a pre-pandemic bonanza, were fearful that electing Biden would lead to more shutdowns and economic recession during an enduring health crisis (Garza 2021; Equis 2021). Despite the ongoing high unemployment in 2020, Trump continued to be seen as a successful entrepreneur committed to guaranteeing jobs and protecting traditional family values, religion, and free enterprise. His trajectory as a businessman made him particularly appealing to first-time, younger, and swing Latino voters, who saw him as best equipped to drive the country out of a pandemic-driven recession (Equis 2021; Garza 2021; Ocampo et al. 2021).

In line with our findings, the literature has shown how the divisive power of Trump’s rhetoric, including his call for patriotic duty, helped split the Latino vote (Garza 2021; Robb 2022). Both the Democratic Party and the media overstated Latinos’ monolithic interests, particularly regarding progressive immigration issues, including the plight of undocumented Latinos (Gonzalez-Sobrino 2021; Ocampo et al. 2021; Robb 2022). Furthermore, Trump’s calls for militarization and national safety found a sounding board among his supporters. For instance, the “defund the police” slogan of the BLM (Black Lives Matter) movement, a direct threat to Trump’s “law and order” motto, helped move the Latino needle toward Trump among those who feared an increase in crime (Garza 2021).

A final note about the scope of our findings is in order, particularly regarding the contemporary role of xenophobia in cementing ethnoracial nationalism. If, until now, xenophobia was mostly known for its exclusionary discourses and practices, this study revealed how it grants conditional inclusion to particular racial and ethnic groups that, irrespective of their skin color, pledge allegiance to the nation-state—even at the price of persecuting their own kind. Finally, by stressing the moral inferiority of the “other,” rather than their racial/ethnic characteristics, xenophobia succeeds in camouflaging racism while merging the nation’s external and internal enemy into one single entity: the undocumented Latino immigrant.

Future studies should consider the emotional and intellectual resonance (i.e., framing effects) of Trump’s speeches on different Latino audiences, particularly regarding the different dimensions of the xenophobic construct (i.e., the framing of the “other” as a threat to minority populations), which may have been effective in attracting specific Latino groups. In sum, we need more data on the diverse—and even contradictory—effects of Trump’s tropes on Latino voters, including the complex ways through which xenophobic narratives help enlist minorities into neopopulist, anti-immigrant political stands.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge my colleague Vivian S. Louie, with whom I began shaping my research notions on Trump’s rhetorics with respect to minority groups generally and Latinos particularly. Sara E. Grummert’s theoretical ideas and data management expertise were invaluable in helping me refine my research findings. I am also thankful to Sandra Gil Araujo and Carolina Rosas, along with the members of their research group at the Gino Germani Institute (University of Buenos Aires, Argentina), for their helpful comments to an earlier version of this paper. As always, Slava Faybysh provided superb editorial assistance. I am particularly grateful to the Journal’s co-editor B. Brian Foster for being in constant communication with me (and for his kindness) during the submission and revision process, and to managing editor Donald R. Guillory for his timely copyediting assistance. The final version of this paper owes a debt of gratitude to the anonymous reviewers whose comments greatly helped improve it.

Author Biography

Anahí Viladrich is an interdisciplinary social science scholar and public health specialist whose work focuses on international migration, Latinos in the United States, health disparities, gender, and culture. The author of more than 60 peer-reviewed publications, this article builds upon her current research trajectory, grants, and publications, geared toward understanding the role of public discourse in shaping mainstream representations of immigrants in the United States and overseas. She is currently a full professor in the Department of Sociology and is affiliated with the Department of Anthropology at Queens College, the Graduate Center (Sociology) and the Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy of the City University of New York (CUNY).

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article: This project was financed by a PSC-CUNY Award (65367-00 53).

ORCID iD: Anahí Viladrich  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4422-7429

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4422-7429

References

- al Gharbi M. 2018. “Race and the Race for the White House: On Social Research in the Age of Trump.” The American Sociologist 49(4):496–519. [Google Scholar]

- Alamillo R.2019. “Hispanics Para Trump?: Denial of Racism and Hispanic Support for Trump.” Du Bois Review 16(2):457–87. [Google Scholar]

- American Immigration Council. 2021. “The Migrant Protection Protocols.” Factsheet, October6. Retrieved November 6 (https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/migrant-protection-protocols).

- Baker J. O., Cañarte D., Day L. E.2018. “Race, Xenophobia, and Punitiveness Among the American Public.” The Sociological Quarterly 59(3):363–83. [Google Scholar]

- Basler C.2008. “White Dreams and Red Votes: Mexican Americans and the Lure of Inclusion in the Republican Party.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 31(1):123–66. [Google Scholar]

- Bergad L. W., Miranda L. A., Jr.2021. “Latino Voter Registration and Participation Rates in the 2020 Presidential Election.” Latino Data Project, Report No. 94, NYC: CLACS. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva E.2004. “From Bi-racial to Tri-racial: Towards a New System of Racial Stratification in the USA.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 27(6):931–50. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley G. L.2002. American Patriots: The Story of Blacks in the Military from the Revolution to Desert Storm. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Cadava G.2020. The Hispanic Republican: The Shaping of an American Political Identity, from Nixon to Trump. New York: HarperCollins. [Google Scholar]

- Canizales S. L., Vallejo J. A.2021. “Latinos & Racism in the Trump Era.” Daedalus 150(2):150–64. [Google Scholar]

- Cech E. A.2017. “Rugged Meritocratists: The Role of Overt Bias and the Meritocratic Ideology in Trump Supporters’ Opposition to Social Justice Efforts.” Socius 3:1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes A. G., Menjívar C.2018. “‘Bad Hombres’: The Effects of Criminalizing Latino Immigrants Through Law and Media in the Rural Midwest.” Migration Letters 15(2):182–96. [Google Scholar]

- Chavez L. R.2013. The Latino Threat: Constructing Immigrants, Citizens, and the Nation, Second Edition. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chiricos T., Welch K., Gertz M.2004. “Racial Typification of Crime and Support for Punitive Measures.” Criminology 42(2):358–90. [Google Scholar]

- Collingwood L., O’Brien B. G.2019. Sanctuary Cities: The Politics of Refuge. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Corral Á. J., Leal D. L.2020. “Latinos Por Trump? Latinos and the 2016 Presidential Election.” Social Science Quarterly 101(3):1115–31. [Google Scholar]

- Dávila A.2012. Latinos, Inc.: The Marketing and Making of a People. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dedoose. 2021. Web Application for Managing, Analyzing, and Presenting Qualitative and Mixed Method Research Data. Version 9.0.17. Los Angeles, CA: Sociocultural Research Consultants, LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Equis. 2021. “Post-mortem: Part 2.” The American Dream Voter, December14. (https://equisresearch.medium.com/post-mortem-part-two-the-american-dream-voter-66dd6f673d1e).

- Fearnow B.2019. “Who Are ‘Angel Moms?’ Trump Jr, RNC Tout Victims’s Families to Promote Border Wall.” Newsweek. January14. (https://www.newsweek.com/angel-moms-illegal-immigrants-killed-donald-trump-jr-border-wall-fox-news-1290461).

- Fernandez L.2013. “Nativism and Xenophobia.” Pp. 1–7 in The Encyclopedia of Global Human Migration, edited by Ness Immanuel, Bellwood Peter. Chichester, England: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Filindra A., Kolbe M.2022. “Latinx Identification with Whiteness: What Drives It, and What Effects Does It Have on Political Preferences?” Social Science Quarterly 103(6):1424–39. [Google Scholar]

- Foster C. H.2017. “Anchor Babies and Welfare Queens: An Essay on Political Rhetoric, Gendered Racism, and Marginalization.” Women, Gender, and Families of Color 5(1):50–72. [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith Q., Callister A.2020. “Why Would Hispanics Vote for Trump? Explaining the Controversy of the 2016 Election.” Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 42:77–94. [Google Scholar]

- Garza D.2021. “Policies, Not Personality: The Defining Characteristic of the 2020 Latino Vote.” Harvard Journal of Hispanic Policy 33:16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. G., Strauss A. L.2017. Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Sobrino B.2020. “Searching for the Sleeping Giant: Racialized News Coverage of Latinos Pre-2020 Elections.” Sociological Forum 35(S1):1019–39. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Sobrino B.2021. “The Nuances of the “Latino Vote”: Toward the Unpacking of the Panethnic.” Sociological Forum 36(2):548–49. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez M. M.2016. “The Coding Manual for Qualitative Research: A Review.” Qualitative Report 21(8):1546–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gostin L. O.2020. “The Great Coronavirus Pandemic of 2020—7 Critical Lessons.” JAMA 324(18):1816–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gover A. R., Harper S. B., Langton L.2020. “Anti-Asian Hate Crime During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Exploring the Reproduction of Inequality.” American Journal of Criminal Justice 45(4):647–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haywood J. M.2017. “Anti-Black Latino Racism in an Era of Trumpismo.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 30(10):957–64. [Google Scholar]

- Henley K., Warren P.2020. “Populism, American Nationalism and Representative Democracy.” Pp. 193–207 in Democracy, Populism, and Truth (AMINTAPHIL: The Philosophical Foundations of Law and Justice Book 9) edited by Navin M. C., Nunan R.Switzerland, Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Heuman A., González A.2018. “Trump’s New Essentializing Rhetoric: Racial Identities and Dangerous Liminalities.” Journal of Intercultural Communication Research 47(4):326–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hinojosa-Ojeda R., Telles E.2021. The Trump Paradox. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld David J., Baker P.2019. “How the Border Wall Is Boxing Trump in.” The New York Times. Retrieved October10, 2021. (https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/05/us/politics/donald-trump-border-wall.html).

- Hochschild J. L.1995. Facing Up to the American Dream: Race, Class and the Soul of the Nation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huber L. P., Lopez C. B., Malagon M. C., Velez V., Solorzano D. G.2008. “Getting Beyond the Symptom, Acknowledging the Disease: Theorizing Racist Nativism.” Contemporary Justice Review 11(1):39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Igielnik R., Keeter S., Hartig H.2021. “Behind Biden’s 2020 Victory.” Pew Research Center Report, June20. Retrieved October23, 2021 (https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2021/06/30/behind-bidens-2020-victory/).

- Kellner D.2017. American Horror Show: Election 2016 and the Ascent of Donald J. Trump. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly C. R.2020. “Donald J. Trump and the Rhetoric of White Ambivalence.” Rhetoric and Public Affairs 23(2):195–223. [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. H., Sundstrom R. R.2014. “Xenophobia and Racism.” Critical Philosophy of Race 2(1):20–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lamont M., Park B. Y., Ayala-Hurtado E.2017. “Trump’s Electoral Speeches and His Appeal to the American White Working Class.” The British Journal of Sociology 68:S153–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louie V., Viladrich A.2021. “Divide, Divert, and Conquer: Deconstructing the Presidential Framing of White Supremacy in the COVID-19 Era.” Social Sciences 10(8):280. [Google Scholar]

- Mannarini T., Salvatore S.2020. “The Politicization of Otherness and the Privatization of the Enemy: Cultural Hindrances and Assets for Active Citizenship.” Human Affairs 30(1):86–95. [Google Scholar]

- Marin L.2016. “Something to Die For. The Individual as Interruption of the Political in Carl Schmitt’s the Concept of the Political.” Revue Roumaine de Philosophie 60(2):311–25. [Google Scholar]

- Massey D. S.2021. “What Were the Paradoxical Consequences of Militarizing the Border with Mexico?” Pp. 32-46 in The Trump Paradox, edited by Hinojosa-ojeda R., Tells E.Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh J. eds. 2020. Language in the Trump Era: Scandals and Emergencies. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Menjívar C.2016. “Immigrant Criminalization in Law and the Media: Effects on Latino Immigrant Workers’ Identities in Arizona.” American Behavioral Scientist 60(5–6):597–616. [Google Scholar]

- Ngai M. M.2014. Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ocampo A. X., Garcia-Rios S. I., Gutierrez A. E.2021. “Háblame De Tí: Latino Mobilization, Group Dynamics and Issue Prioritization in the 2020 Election.” The Forum 18(4):531–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ott B. L., Dickinson G.2019. The Twitter Presidency: Donald J. Trump and the Politics of White Rage. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Petroff A., Viladrich A., Parella S.2021. “Framing Inclusion: The Media Treatment of Irregular Immigrants’ Right to Health Care in Spain.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 82:135–44. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera C.2014. “The Brown Threat: Post-9/11 Conflations of Latina/os and Middle Eastern Muslims in the US American Imagination.” Latino Studies 12(1):44–64. [Google Scholar]

- Robb J.2022. Political Migrants: Hispanic Voters on the Move—How America’s Largest Minority Is Flipping Conventional Wisdom on Its Head. Arlington, VA: NumbersUSA Education & Research Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Saito N. T.2021. “Why Xenophobia?” La Raza Law Journal 31:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez G. R., Gomez-Aguinaga B.2017. “Latino Rejection of the Trump Campaign: How Trump’s Racialized Rhetoric Mobilized the Latino Electorate as Never Before.” Aztlan 42(2):165–81. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer D. O.2020. “Whiteness and Civilization: Shame, Race, and the Rhetoric of Donald Trump.” Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies 17(1):1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt C.2007. The Concept of the Political. Expanded ed. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider U., McClure K. K.2020. “I’m Doing Great with the Hispanics. Nobody Knows It.” Pp. 130–152 in Linguistic Inquiries into Donald Trump’s Language: From “Fake News” to “Tremendous Success,” edited by Schneider U., Eitelmann M.New York: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Silber Mohamed H., Farris E. M.2020. “‘Bad Hombres’? An Examination of Identities in US Media Coverage of Immigration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46(1):158–76. [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. N.2019. a. “Authoritarianism Reimagined: The Riddle of Trump’s Base.” The Sociological Quarterly 60(2):210–23. [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. M.2019. b. “The Trump Administration’s Third Country Transit Bar.” Georgetown Immigration Law Journal 34:539–43. [Google Scholar]

- Sosa L.2009. “Politics and the Latino Future: A Republican Dream.” Pp. 115–124 in Latinos and the Nation’s Future, edited by Cisneros H., Rosales J.Houston, Texas: Arte Público Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stelter B.2020. Hoax: Donald Trump, Fox News, and the Dangerous Distortion of Truth. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Sundstrom R. R.2013. “Sheltering Xenophobia.” Critical Philosophy of Race 1(1):68–85. [Google Scholar]

- Viladrich A.2019. “We Cannot Let Them Die”: Framing Compassion Towards the Health Needs of Unauthorized Immigrants in the United States (United States).” Qualitative Health Research 29(10):1447–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viladrich A.2021. “Sinophobic Stigma Going Viral: Addressing the Social Impact of COVID-19 in a Globalized World.” American Journal of Public Health 111(5):876–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimmer A.1997. “Explaining Xenophobia and Racism: A Critical Review of Current Research Approaches.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 20(1):17–41. [Google Scholar]

- Wistrich R. S., ed. 2013. Demonizing the Other: Antisemitism, Racism and Xenophobia. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Bennett L.2022. “Interactive Propaganda: How Fox News and Donald Trump Co-produced False Narratives About the COVID-19 Crisis.” Pp. 83–100 in Political Communication in the Time of Coronavirus, edited by Van Aelst P., Brumler J. G.New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]