Abstract

Leaders play a critical role in the development and execution of Total Worker Health (TWH). Small businesses, in particular, can benefit from strong leadership support for TWH as the burden of work-related injury, illness and fatality, as well as poor health and well-being is high in this population. In the present study, we conducted a program evaluation of a TWH leadership development program for small business leaders using the RE-AIM framework. The goal of the program was to help change leaders’ behaviors around health, safety and well-being practices following the theory of transformational leadership. Two leaders from each business participated in pre-training activities on their own, a 6-hour in-person training, and three months of access to virtual training transfer activities, including coaching and goal tracking. Our results suggest that the TWH leadership development program is effective at improving leaders’ self-reported TWH leadership practices and that the in-person training was implemented successfully. However, leaders did not report improvements in their personal health and in fact reported increased levels of work stress after the program. We also observed some challenges when implementing our training transfer strategies. Our study suggests that leaders may benefit from attending TWH leadership trainings alongside other colleagues in their organization to facilitate a shared vision and goals for TWH in their organization. As a next step, it will be important to determine the program’s effectiveness in changing business TWH policies and practices, employee perceptions of TWH and leadership, and employee health and safety outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

Organizational leadership plays a critical role in the development and execution of Total Worker Health (TWH) in practice. TWH is defined as the integration of protection from work-related safety and health hazards with promotion of injury and illness prevention efforts to advance worker well-being (NIOSH, 2020). Small businesses, in particular, can benefit from strong leadership support for TWH (Shore et al., 2020). In 2016, 83% of establishments in the United States had fewer than 500 employees and they employed almost half of the entire US workforce (United States Census Bureau, 2020). The burden of work-related injury, illness, and fatality, as well as poor health and well-being, is high in this population (Schwatka et al., 2018). Our research and that of others suggest that this may be driven by the relative lack of TWH policies and programs to protect and promote worker health (Linnan et al., 2008). However, one of the root causes of this paucity of policies and programs may be inadequate leadership support for TWH. In a study of 382 businesses, Tenney et al. (2019) found that smaller the business, the less likely there were to be leadership supports for TWH efforts via resource allocation, role modeling, communication, recognition, and accountability. In a separate qualitative study with 18 small business leaders from diverse industries, Thompson et al. (2018) found that leaders may not have a complete understanding of and skills for TWH leadership. Given the impact that leadership support can have on small business health and safety outcomes (Shore et al., 2020), it is important to understand how to foster leadership support for TWH.

Effect of leadership on health, safety, & well-being

Kelloway et al. argued that “the relationship with one’s formal leader in an organization is one of the most important workplace relationships with implications for individual well-being” (2010, p.g., 261–262). This relationship can be characterized by the style of leadership that the leader adopts. Most of the occupational health and safety literature has focused on Bass’s (1985) transformational and transactional leadership styles. Transformational leaders set examples for their employees, they motivate employees to achieve group and individual goals, they inspire employees to be creative and innovative, and they show respect and concern for each employee. More active forms of transactional leadership, such as contingent reward where rewards are given for positive behaviors, elicit positive health and safety outcomes. However, more passive forms of transactional leadership, such as management-by-exemption where corrections are given after the fact, are less effective (Mullen, Kelloway, & Teed, 2011). There is even evidence that leaders who switch between more active and passive leadership styles elicit poor safety outcomes (Mullen et al., 2011).

There is a significant amount of literature demonstrating the relationship between leadership and worker health, safety, and well-being. Several meta-analyses link leadership to safety climate, safety behaviors, burnout, and accidents and injuries (Christian, Bradley, Wallace, & Burke, 2009; Clarke, 2013; Nahrgang, Morgeson, & Hofmann, 2011). Studies also link leadership to stress (Sosik & Godshalk, 2000), depression (Munir, Nielsen, & Carneiro, 2010), sleep quality (Munir & Nielsen, 2009), ischemic heart disease (Nyberg et al., 2009), high blood pressure (Karlin, Brondolo, & Schwartz, 2003), problem drinking (Bamberger & Bacharach, 2006), smoking (Erikson, 2005), well-being (Nielsen, Randall, Yarker, & Brenner, 2008) as well as sickness absence and disability pension (Kuoppala, Lamminp, Liira, & Vainio, 2008).

Safety and health leadership interventions

There are several examples of successful safety leadership interventions. Some safety leadership interventions focus specifically on safety communication between supervisors and workers (e.g., Zohar & Polachek, 2014) while others are focused on leadership broadly (e.g., Clarke & Taylor, 2018). In the construction industry, for example, interventions vary in length from multi-hour, one-day trainings (e.g., Schwatka et al., 2019) to multi-week or multi-month trainings focused on didactics, feedback, and practice (e.g., Jeschke et al., 2017). Most focus on leadership and safety climate outcomes and generally observe positive changes from before to after their leadership interventions (Clarke & Taylor, 2018), but some have not observed changes in these outcomes (Casey, Krauss, & Turner, 2018).

To our knowledge, there are only a few health promoting leadership intervention studies. In the Swedish public administration industry, researchers describe program evaluations of multi-month health promoting leadership interventions that focus on discussion, coaching, and action plans (Eriksson, Axelsson, & Axelsson, 2010; Larsson, Stier, Akerlind, & Sandmark, 2015). Other worksite wellness interventions include management or champions in their health promotion interventions. For example, senior management were provided coaching during a broader worksite wellness intervention (e.g., Linnan et al., 2020) and in other studies members of management were included as participants in the intervention but not given leadership training (e.g., Ryan et al., 2019).

There are few examples of TWH leadership interventions in small enterprises. However, there are some promising approaches tested amongst larger employers. For example, Hammer et al. (2015) evaluated an integrated family as well as safety supportive supervisor training for construction workers employed in an urban municipal department. In a field study of health care employees, Bronkhorst et al. (2018) evaluated an intervention to improve safety climate, including senior management safety rounds (i.e., bi-monthly meetings between management and employees) and supervisor leadership training. During the intervention, they transitioned between three themes: physical health and safety, psychosocial health and safety, and organizational conditions for health and safety. Although Anger et al.’s (2019) review indicates that most TWH interventions engage company leadership in the TWH intervention, it is not typically in the form of leadership training for TWH.

Taken from another perspective, there is limited research on how leadership development interventions can influence leaders’ own health. This is likely due to the typical focus on employee outcomes as a result of leadership development (Kelloway & Barling, 2010). Barling et al. (2017), for example, noted a lack of research on leader development and their mental health. One recent review of the use of coaching as a leadership development activity found some evidence that coaching may improve leader psychological well-being, stress, and depression (Grover & Furnham, 2016). We argue that it will be hard for leaders to effectively lead for employee health, safety, and well-being if they are not also caring for their own health, safety, and well-being. When leaders focus on their own health, they are role modeling pro-health behaviors, a strong signal to employees that health is valued. Indeed, evidence suggests that leader health indicators, such as poor sleep, can influence their leadership practices as well as their followers’ health (Barnes, Guarana, Nauman, & Kong, 2016). It should be noted that there are examples of health promoting interventions for leaders (e.g., Cutts, Gunderson, Proeschold-Bell, & Swift, 2012).

Conceptual models propose that TWH leadership development is the key to facilitating TWH organizational change (Schwatka et al., 2018). Thus, in the present study, we present a demonstration of how to implement a TWH leadership development program for pairs of leaders from small businesses. We present preliminary evidence of the value of implementing this approach by testing the hypothesis (H1) that from one month before to three months after the TWH leadership development program, leaders would improve their TWH leadership practices and modifiable health risk factors. We also wanted to determine whether leaders would report changes to their intentions to transfer the training to the job from immediately after to three months after the program (Research Question 1 - RQ1).

We also evaluated the implementation process by addressing several additional research questions. We aimed to determine whether leaders had favorable reactions to the TWH leadership development program, including what leaders identified as barriers and facilitators to their behavior change (RQ2). Given the importance of goal setting during leadership training to facilitate transfer of training (Johnson, Garrison, Hernez-Broome, Fleenor, & Steed, 2012), we assessed what goals leaders set for themselves during the program and whether they met their goals as a means of both understanding what leaders were focused on working on as a result of our training and as a means of tracking transfer of training (RQ3). Finally, we evaluated whether each of the components of the program were implemented as planned (RQ4).

METHODS

Sample

We recruited program participants through the Small+Safe+Well (SSWell) Study that tests an intervention targeting organizational TWH change through two intervention components. In the present study, we examined the leadership development component of the intervention (see Schwatka et al., 2018 for more detail). Businesses with fewer than 500 employees enrolled in SSWell, completed an organizational assessment (Healthy Workplace Assessment™) and advising offered through the Health Links™ program (www.healthlinkscertified.org). After completing the Healthy Workplace Assessment, businesses were asked to administer an employee health and safety culture survey. Once the business completed its business- and employee-level assessments, they were randomly assigned to either an early TWH leadership development program or a lagged program. The businesses randomly assigned to the lagged program served as controls in the SSWell study by completing two sets of assessments one-year apart before participating in their TWH leadership development program. All businesses had the opportunity to participate in the TWH leadership development program prior to the conclusion of the study, regardless of program assignment.

For the purposes of this evaluation, we combined data from both early and lagged businesses and focused on leader-level data that were collected for program evaluation purposes. It should be noted that the study design of the SSWell study included a control group to assess changes in business- and employee-level outcomes, however this program evaluation of the leadership program by design did not include a control group to assess changes in leader outcomes. The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board approved all study protocols.

We included four cohorts of leaders who participated in the TWH leadership development program between January 2019 and January 2020. All eligible small businesses were invited to enroll one owner or another key decision maker from their senior leadership team to participate in the program through an online enrollment form. During the piloting of the program, we learned that the owner or other key decision makers on the senior leadership team favored having a colleague familiar with the organization’s safety and health efforts attend the program with them. They indicated that it was important to have a key individual responsible for health and safety to understand what their leadership was learning about. Thus, if the key decision maker agreed to participate, they were also invited to nominate another colleague from their business to attend, such as their human resources or safety manager. A maximum of two leaders per business were invited to participate.

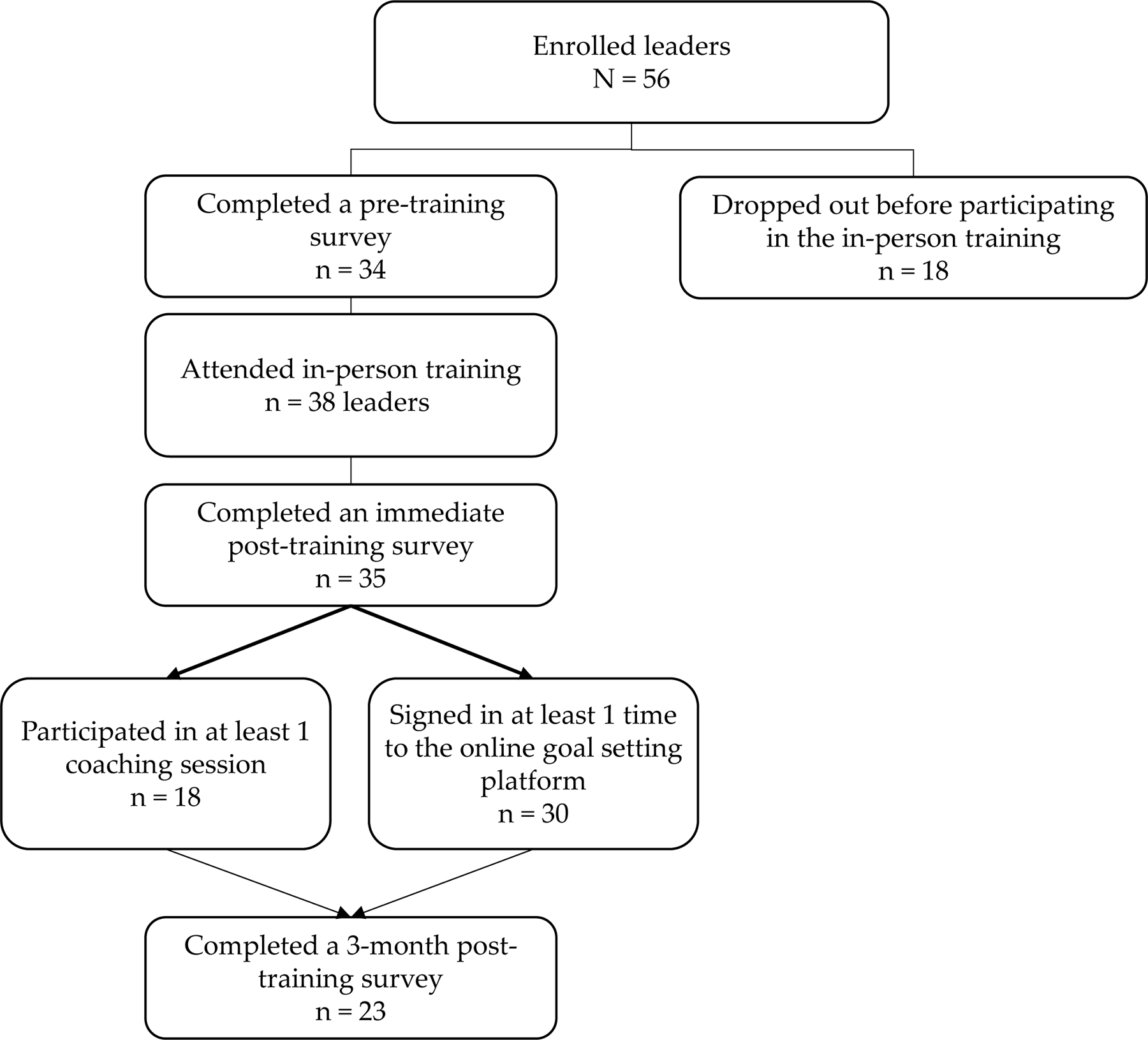

Figure 1 displays leader study enrollment and participation. Ultimately, 38 leaders (i.e., owner or other key decision maker and other key health and safety personnel) from 23 businesses participated in the TWH leadership development program. Leaders who enrolled in the TWH leadership development program but did not ultimately come to the in-person training (n = 18), indicated that they were too busy to attend (n=9), the weather was too poor to travel in (n=3), or they were sick (n=3). Three leaders did not give a reason. Of the 38 leaders who participated in the in-person training, 34 (89%) completed a pre-training survey, 35 (92%) completed an immediate post-training survey, and 23 (58%) completed the 3-month follow-up survey.

Figure 1.

Study enrollment and participation

TWH Leadership Development Program & Evaluation Strategy

Our TWH leadership development program consisted of 10-hours of self-paced reflection, in-person training, and virtual training transfer support over four months. The goal of the program was to help small business leaders change their behaviors around workforce health protection and promotion following the theory of transformational leadership (Kelloway & Barling, 2010). Leaders participated in pre-training activities (1-hour), a 6-hour in-person training, and were offered three months of access to virtual coaching and goal tracking that were estimated to last for 3 hours. Each program component is described below and an outline of the program can be viewed in Online Resource 1. All materials were piloted prior to this study.

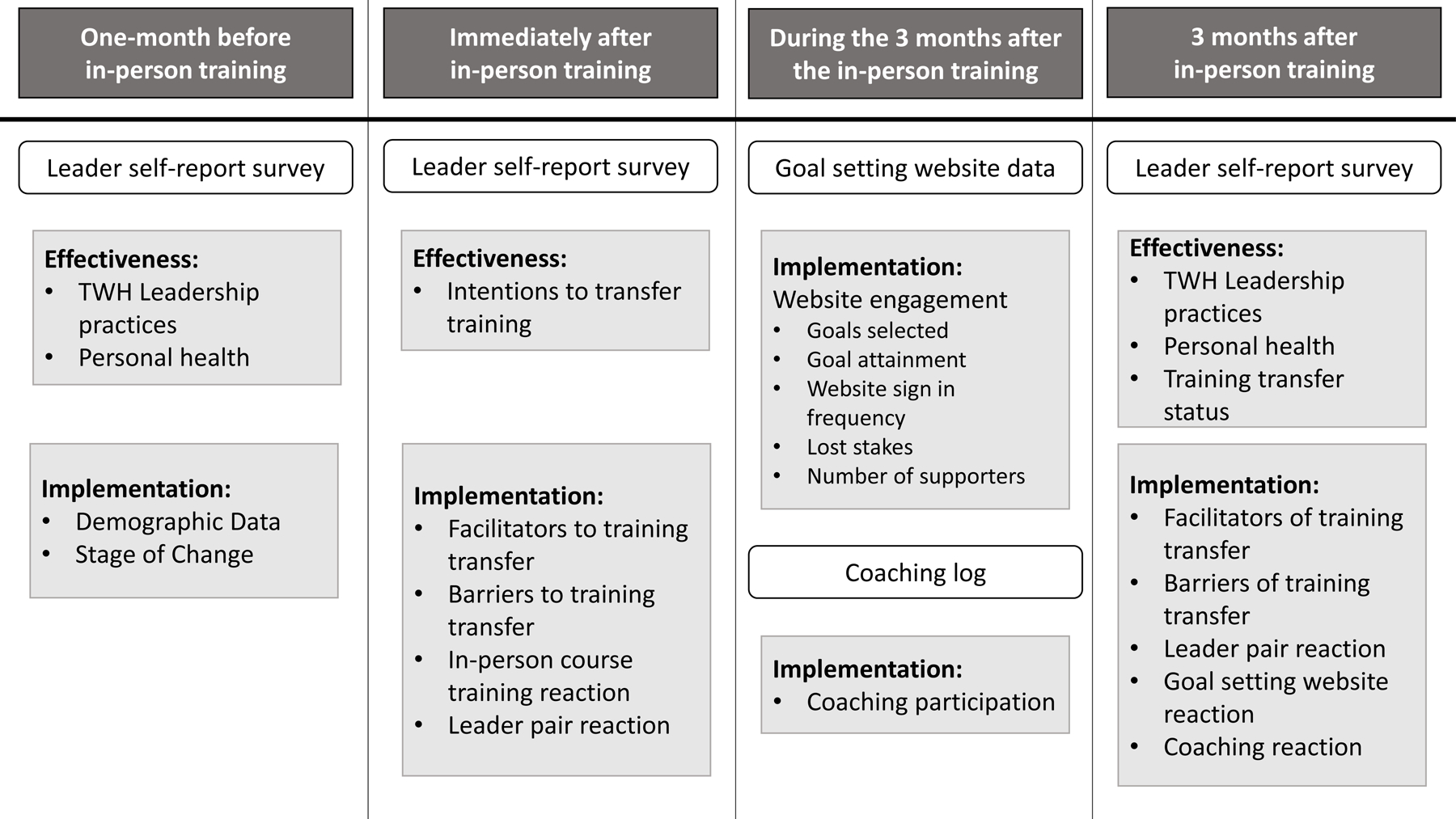

We applied the RE-AIM program framework (Glasgow, Vogt, & Boles, 1999) to evaluate core constructs of the program. The RE-AIM framework has been utilized in a variety of settings for the planning, implementation, and evaluation of public health interventions (Gaglio, Shoup, & Glasgow, 2013). The RE-AIM framework includes five dimensions (reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance) to measure the public health impact of an intervention (Glasgow, Vogt, & Boles, 1999). For this evaluation, we focused only on effectiveness and implementation as the most relevant dimensions. Effectiveness refers to the impact of an intervention and can include both positive and negative impacts. Implementation refers to how the intervention was delivered, particularly as compared to the intervention protocol - for example, whether all parts of the intervention successfully delivered or were changes made by in the delivery (Glasgow, Vogt, & Boles, 1999). Figure 2 displays the effectiveness and implementation outcome variables. Measures of reach and adoption are presented in the results, but are a function of the overall enrollment in the SSWell Study, as those were the organizations and individuals eligible to participate in the leadership training. Maintenance is not reported, as the timeframe of this program evaluation has not yet allowed us to measure longer-term sustainability of leadership outcomes. Each component of our program evaluation strategy is discussed below.

Figure 2.

Program evaluation design

Pre-training activities

Before the in-person training, participants were asked to spend time reflecting upon their business’s TWH strategy as well as their own TWH leadership practices and personal health. To facilitate this, they were given access to their business- and employee-level assessment reports completed as part of the SSWell study. Participants also completed an online survey that asked questions about their current TWH leadership practices as well as their modifiable health risk factors.

The business-level assessment report was generated from the Healthy Workplace Assessment™ (Tenney et al., 2019). The Assessment is a 35-item web-based instrument measuring existing evidence-based TWH strategies across 6 core benchmarks including organizational supports, workplace assessment, health policies and programs, safety policies and programs, engagement, and evaluation. All items refer to the previous 12 months and answered with a “yes” or “no” response. After completing the Assessment, organizations received a report card with a total score and benchmark scores along with recommendations for improvement in each area. Businesses were also directed to an online resource center that provided a centralized database of tools including online materials for implementing TWH, relevant to each recommendation. Leaders were given their report card as well as an answer-by-answer copy of their entire assessment.

The employee-level assessment is a 109 question employee health and safety culture survey, which assesses employee perceptions of organizational support, satisfaction, and commitment (Eisenberger, Huntinton, Hutchinson, & Sowa, 1986; Fisher, Matthews, & Gibbons, 2015; Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006); work/life balance (Fisher et al., 2015); well-being (Staehr, 1998); work stress (Schwatka et al., 2017); leadership commitment to safety and health (Shore et al., 2020); safety and health climates (Lee et al., 2014; Zweber, Henning, & Magley, 2016); and employee safety and health motivations and behaviors (Conchie, 2013; Griffin & Neal, 2000). Leaders were given a summary report containing average and range of employee responses to each of the dimensions. For privacy reasons, we did not provide demographic or employee health responses. Three participants did not receive a report because there were fewer than five employee responses to the survey.

Data collection.

One month before the in-person training, leaders were emailed a link to an online survey containing questions about their demographics, TWH leadership practices, personal modifiable health risk factors, and change readiness. We asked leaders about their age, gender, race, ethnicity, education, job level, and tenure. We addressed hypothesis (H1) with 27 TWH leadership practice questions that covered five domains specifically asking about their behaviors towards employee health, safety, and well-being and aligning closely with transformational leadership theory (Bass, 1985; Kouzes & Posner, 2012) (1–5 Likert scale, strongly disagree to strongly agree): passionate advocate (α = 0.79), provide a supportive work environment (α = 0.66), be a role model (α = 0.65), encourage growth and change (α = 0.64), and expect and recognize success (α = 0.64). An example question is, “I communicate a positive outlook for employee health, safety, and well-being.” See Online Resource 2 for a list of all questions and more information on a reliability analysis used to determine which items to include in the final analysis. The 12 personal health questions (H1) asked about well-being (Staehr, 1998), overall health (1–5, poor to excellent), stress at work (1–5, never to always), stress at home (1–5, never to always), stress over finances (1–5, never to always), physical activity (number of days per week of 30 minutes of moderate to vigorous activity), and sleep hours per night (1=<6 hours, 2=6–6.9 hours, 3=7–8 hours, 4=>8 hours) (Schwatka et al., 2017). Finally, we asked leaders about their stage of change for TWH leadership by adapting one question from Cunningham et al. (2002) that asked leaders to pick the statement that resonated most with them. Each statement corresponded to one of the five stages of change. The stages of change is based on the transtheoretical model that focuses on decisions to intentionally change behaviors over time. It starts with pre-contemplation where one may not be ready to change and progresses to contemplation (getting ready to change in a few months), preparation (ready to change in immediate future), action (made changes already), and, finally, maintenance (made changes already and are working to prevent a relapse).

In-person training

The in-person 6-hour training began with a discussion of key leadership practices for TWH and the business case for TWH, including topics like return on investment, value, etc. The rest of the training covered three content areas: business TWH strategy, employee perspectives of TWH culture, and personal health and well-being. Participants were asked to consider the TWH leadership practices they could use to influence their businesses in each of these three areas. The training included didactics, discussions at the business pair level, broader group discussions, and TWH goal setting. Trainings were conducted by experienced TWH educators using a single set of presentation materials and an outlined script covering learning objectives. NS and LN were trainers for all four cohorts and JS was also a trainer for two of the cohorts. The number of individuals per training ranged from 6 to 14 participants. At the end of each in-person training, participants identified business, culture, and individual health goals based on the assessment data in the context of their TWH leadership practices.

Participants selected goals from multiple pre-set goals developed based on the training content. These goals served as explicit examples by which we taught leaders how to implement TWH principles. They were able to customize their goal by writing in the specific action they will take to meet the goal. Depending on the goal content and complexity, we set the completion date to be either in 30, 60 or 90 days and the goal reporting period to be weekly or one-time. For example, one of the goals in the employee section was “Incorporate TWH values into business mission/vision.” Leaders who selected this goal were required to report on their goal one-time within 30 days. It is important to note that we chose to create these goals for leaders because of feedback we received during the pilot of our program. Leaders expressed an interested in taking action after the in-person training but needed help identifying specific actions they could take.

In all, during the training leaders were asked to set one goal in each of the three content areas described above and enter them into an online, social goal setting website that could be accessed by a computer or mobile device, which we maintained. We created a goal setting platform specifically for purposes of this study by customizing a website called www.stickk.com. The website allows users to create goals, select accountability methods, and track goal progress. Leaders used their own login to input each goal. The website had a few methods to facilitate goal attainment. Participants could choose to set an disincentive for not meeting their goal – called “setting the stakes”. Leaders who chose to set stakes on their goal(s) entered personal credit card information and placed a dollar amount that they would put at risk if they failed to accomplish their goal by the date indicated. It also allowed them to invite peers, employees or family members as “supporters”. Finally, the trainers were assigned as “referees” to track leaders’ goal progress and provide feedback along the way.

Data collection.

Immediately after the in-person training, leaders were given a paper survey. They were asked eight training reaction questions about the organization, quality, and educational content that we developed (1–5 Likert scale, strongly disagree to strongly agree). They were also asked to give an overall rating of the course (1–5, poor to excellent) (RQ2). Next, they were asked about their intentions to transfer what they learned in the training to their business (RQ1) (4 items, 1– 5 Likert scale strongly disagree to strongly agree) (Al-Eisa, Furayyan, & Alhemoud, 2009; Machin & Fogarty, 2004) for this study. An example question is, “I plan to discuss ways to apply the material that I have learned in the TWH leadership program with my TWH lead(s).” We also asked them to rate whether they expected to experience barriers and facilitators to training transfer. They were given a list of potential barriers (e.g., stress or too much work) and facilitators (e.g., supervisor support and teamwork) and were asked to check all that apply. Additionally, since pairs of leaders from each organization attended the training, we also asked them questions about how they worked together during the training by asking four questions we developed about collaboration, shared goals, and role clarification (1 to 5 Likert scale, strongly disagree to strongly agree). Finally, we asked them an open-ended question about their suggestions for improving the training.

Training transfer activities

For three months after the training, we offered two training transfer activities with the leaders: goal tracking and virtual coaching. Participants were able to access the online, social goal setting website from which they could track their goal progress and use the comment board to report their progress and ask the trainers questions. To successfully complete a goal on the website, the leader had to sign in by the appropriate date and report on whether they met their goal. Leaders were also offered up to three 30-minute virtual coaching sessions with a trainer to receive customized advice and guidance on goal attainment. The leaders could schedule the coaching sessions anytime during the three months following the in-person training via a link to an online calendar application that was emailed to them three times during the training transfer activity period. The coach took notes about goal progress and the next steps during each session and emailed the leader a summary after each session.

Data collection.

During the three months that leaders participated in the virtual training transfer activities, we collected data to address our third and fourth research questions. We collected data on the number of times leaders participated in a virtual coaching session. We also collected user data from the online goal setting website to determine which goals leaders were selecting and whether they reported meeting their goals. Information on how many times they signed into the website, whether they lost money due to not meeting their goals, and how many supporters they had was also available. We supplemented the analysis of goal setting and attainment with qualitative information gathered during coaching sessions.

Three months after attending the in-person training and participating in the virtual training transfer activities, leaders were asked to complete an online follow-up survey. The survey contained the same four training transfer questions as the immediate post training survey, phrased using the past tense (RQ1). An example question is, “I have discussed with my TWH lead(s) ways to apply the material that I have learned in the TWH leadership program.” The survey also contained 15 training reaction questions (RQ2) about the organization, quality, and helpfulness of the online, social goal setting website and the virtual coaching sessions in helping them stick to their goals, including open ended questions that asked them why they did not engage in the training transfer activities and their suggestions for the activities that we developed. Finally, the survey contained the same four questions about how the pairs of leaders from each organization worked together. We also added a question about whether they experienced conflict working together during the training transfer period.

The online follow-up survey also contained the same 27 TWH leadership practice questions and the 12 modifiable health risk factors questions included in the pre-training survey (H1).

Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to describe all data. Additionally, we ran linear mixed regression models with a random intercept to account for repeated measures within leader to test the hypothesis that leaders would report improvements in their TWH leadership practices as well as improvements in their modifiable health risk factors from one month before to three months after the in-person training. We used the same statistical model framework to address our first research question about changes in intentions to apply what was learned in the program from immediately after to three months after the program. All models controlled for industry, number of employees in the business, tenure with their current company, and whether their job level was at least a senior management position (senior manager, executive, president/CEO) or not. We used Stata (StataCorp. 2017. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC.) to analyze all study data.

RESULTS

Participants came from a variety of industries, including nearly half from health care and social assistance or public administration (see Table 1). They primarily represented businesses with 11–49 (50.0%) or with less than 10 employees (10.5%). One quarter of them worked for businesses in a rural area of Colorado. They were mostly white, non-Hispanic/Latino females with an average age of 42 (SD = 11.4) and at least a 4-year degree (88.24%). Almost three-quarters held a senior management role. Leaders reported being in a pre-contemplation (n = 1, 3%), contemplation (n = 9, 27%), preparation (n = 8, 24%), action (n = 9, 27%), or maintenance (n = 6, 18%) stage of change for TWH leadership.

Table 1.

Demographics

| Mean/n | SD/% | |

|---|---|---|

| Industry | ||

| Accommodation & Food Service | 2 | 5.3% |

| Construction | 1 | 2.6% |

| Educational Services | 1 | 2.6% |

| Health Care & Social Assistance | 15 | 39.5% |

| Information | 1 | 2.6% |

| Manufacturing | 3 | 7.9% |

| Non-profit | 2 | 5.3% |

| Public Administration | 8 | 21.1% |

| Real Estate & Rental & Leasing | 1 | 2.6% |

| Services | 4 | 10.5% |

| Region | ||

| Urban | 17 | 73.9% |

| Rural | 6 | 26.1% |

| Number of employees | ||

| <10 employees | 4 | 10.5% |

| 11–49 employees | 19 | 50.0% |

| 50–200 employees | 9 | 23.7% |

| 201+ employees | 6 | 15.8% |

| Age (years) | 42 | 11.4 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 3 | 8.8% |

| Female | 31 | 91.2% |

| Race | ||

| White | 31 | 91.8% |

| Black or African American | 1 | 2.9% |

| Native American or Alaskan Native | 2 | 5.9% |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic or Latino or Spanish Origin | 1 | 3.1% |

| Not Hispanic or Latino or Spanish Origin | 31 | 96.9% |

| Education | ||

| High school diploma or GED | 1 | 2.9% |

| Some college or 2-year degree | 3 | 8.8% |

| 4-year college degree | 16 | 47.1% |

| Graduate or professional degree | 14 | 41.2% |

| Job Level | ||

| Non-supervisor | 5 | 14.7% |

| First-level supervisor | 1 | 2.9% |

| Mid-level supervisor | 2 | 5.9% |

| Senior manager | 12 | 35.3% |

| Executive level | 11 | 32.4% |

| President/CEO | 2 | 5.9% |

| Not sure | 1 | 2.9% |

| Job Tenure (years) | 6 | 4.1 |

Note. Column values do not add to the total number of leaders who came to the training (38) due to missing data.

There were minimal differences between those who engaged in the program and those who did not. Significantly more females participated in the in-person training than males (χ2 (1) = 6.06, p = 0.01). Leaders who participated in at least one coaching session had been with their current company for a significantly longer amount of time (t(32) = −2.02, p = 0.05). Third, leaders who signed into the website at least one time worked for larger companies than leaders who did not (t(36) = −1.66, p = 0.05). There were no other differences in the types of businesses and no other demographic differences between leaders who showed up to the in-person training, participated in at least one coaching session, or signed in at least one time to the goal setting website after the in-person training.

Effectiveness

To address our first research question on whether leaders maintained their intentions to transfer what they learned in the in-person training at three months after the in-person training we compared survey responses collected immediately after the training and three months after the training (see Table 2). Immediately after the in-person training, leaders reported strong intentions to transfer what they learned in the training. Three months after the in-person training, we observed that leaders had maintained their intentions to discuss ways to apply the material with their TWH lead. They also maintained their initial assessment that the knowledge and skills were useful in their current role. However, we observed a slight decline from immediately after to three months after in leaders’ assessment of their use of the knowledge and skills on the job as well as their assessment of whether the knowledge and skills helped to improve their job performance.

Table 2.

Linear mixed regression results for change in self-reported Total Worker Health leadership practices and Total Worker Health leadership training transfer practices from one month before to three months after the in-person training

| One month before | Three months after | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Outcome | M | SD | M | SD | Beta | 95% CI | P-value |

| TWH leadership practices | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Passionate advocate | 4.20 | 0.52 | 4.36 | 0.44 | 0.11 | −0.04, 0.25 | 0.15 |

| Provide a supportive work environment | 4.05 | 0.51 | 4.43 | 0.50 | 0.36 | 0.15, 0.58 | <0.01 |

| Be a role model | 3.89 | 0.54 | 4.22 | 0.41 | 0.30 | 0.10, 0.49 | <0.01 |

| Encourage growth and change | 3.68 | 0.60 | 4.04 | 0.52 | 0.26 | 0.05, 0.48 | <0.01 |

| Expect and recognize success | 3.74 | 0.43 | 4.17 | 0.51 | 0.34 | 0.13, 0.56 | <0.01 |

|

| |||||||

| Immediately after | Three months after | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| TWH leadership training transfer practices | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Discuss ways to apply the material with my TWH lead(s). | 4.58 | 0.61 | 4.60 | 0.50 | −0.11 | −0.46, 0.22 | 0.51 |

| Use the knowledge and skills on the job. | 4.05 | 1.05 | 4.36 | 0.66 | −0.16 | −.046, 0.13 | 0.26 |

| The knowledge and skills will be useful to me in my current role. | 4.70 | 0.47 | 4.45 | 0.51 | −0.32 | −0.55, −0.09 | <0.01 |

| The knowledge and skills I learned in the TWH Leadership Program will help me improve my job performance. | 4.27 | 0.63 | 4.00 | 0.76 | −0.35 | −0.70, −0.00 | 0.05 |

Note. Each variable was entered into its own model. All models controlled for industry, number of employees the business had, tenure, and whether they were in at least a senior management position or not.

Hypothesis 1 stated that there would be a change in TWH leadership practices and leader modifiable health risk factors from before to 3-months after the training. The results of the linear mixed models demonstrate that leaders reported improving four out of five TWH leadership practices (see Table 3). Leaders reported engaging in more practices around providing a supportive work environment, being a role model, encouraging growth and change. and expecting and recognizing success. Leaders did not report being more of a passionate advocate after the training. Correlations among variables can be found in Online Resource 3.

Table 3.

Linear mixed regression results for change in health indicators from one month before to three months after the in-person training

| One month before | Three months after | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Outcome | M | SD | M | SD | Beta | 95% CI | P-value |

| Well-being | 3.79 | 0.69 | 3.94 | 0.70 | 0.19 | −0.10, 0.49 | 0.19 |

| Overall health | 3.48 | 0.70 | 3.45 | 0.67 | 0.01 | −0.30, 0.32 | 0.96 |

| Stress at home | 3.48 | 0.80 | 2.68 | 0.65 | −0.86 | −1.30, −0.41 | <0.001 |

| Stress at work | 2.59 | 0.75 | 3.41 | 0.67 | 0.73 | 0.28, 1.17 | <0.001 |

| Stress over finances | 2.70 | 0.87 | 2.59 | 1.01 | 0.11 | −0.21, 0.43 | 0.51 |

| Exercise days | 3.31 | 1.63 | 3.57 | 1.84 | 0.23 | −0.06, 0.53 | 0.12 |

| Sleep | 2.78 | 1.31 | 1.67 | 0.58 | −0.02 | −1.27, 1.08 | 0.97 |

Note. Each variable was entered into its own model. All models controlled for industry, number of employees the business had, tenure, and whether they were in at least a senior management position or not.

We also hypothesized that leaders would improve their modifiable health risk factors from one month before to 3-months after the in-person training (H1). As can be seen in Table 3, leaders reported an increase in stress levels at work, but decreased stress levels at home. We did not observe changes in any of the other health variables.

Implementation

In-person Training Reactions

Participants rated all aspects of the in-person training highly (RQ2). The average training reaction rating was 4.54 out of 5.00 (SD = 0.41, α = 0.83) with mean scores ranging from 4.09 for the question about their confidence to successfully lead their organization towards health and safety to 4.82 for items addressing the quality of instruction and their increased awareness about Total Worker Health leadership (see Table 1 in Online Resource 3). One leader wrote, “I’m so excited about this and I love the practical info, accountability, and support! This would have been so daunting to try on my own.”

Immediately following the training, participants reported their anticipated barriers to implementing what they learned into their business (RQ2). The most common personal barriers reported were stress (n = 19, 54.3%), too much work (n = 18, 51.4%), time pressure (n = 15, 42.9%), and lack of control over how or when work is done (n = 12, 34.3%). Participants also reported on those things that could help them transfer what they learned into their workplace immediately following training. The most frequently cited anticipated facilitators included teamwork (n = 23, 65.7%), an environment that is supportive of work/life balance (n = 21, 60.0%), supervisor support (n = 21, 60.0%), and good leadership (n = 20, 57.1%). At the three month follow-up, participants were again asked to report on actual barriers and facilitators they faced. Due to a large number of people (87%) who skipped those items, results are not presented here.

Goal Setting

We addressed our third research question (RQ3) by reviewing data collected from the goal setting website. Thirty-five of 38 leaders (92.1%) set goals during the in-person training. They were instructed to set three goals (one for their business’s TWH strategy, one for culture, and one for themselves) and 26 people (74.3%) selected three goals. An additional seven people (20.0%) selected two goals, and one person (2.9%) each selected one goal and four goals. The most common business TWH strategy goal selected by participants was develop a TWH program – write a plan for your TWH program, which was selected by 53.9% (see Table 4). The most common employee goal was to identify the needs and interests of your employees – meet with employees at least one time per week to define TWH needs and interests, which was selected by 51.7% of participants. Finally, the most common self-goal was personal health, safety, and well-being – take time to enhance my health, safety, and well-being each week, which was selected by 93.1% of participants.

Table 4.

Description of goals set during the training and frequency with which goals were selected

| Training section | Goal Title | Goal Structure (I commit to…) | Goal description | Reporting structure | # (%) of times the specific goal was chosen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Business Strategy | Develop TWH program | Writing a plan for your TWH program. | Use TWH leadership skills to address a strategy for the policies and programs your business will do to protect and promote employee health. | One time within 30 days | 21 (53.9%) |

| Initiate TWH program | Initiating a new TWH program element. | Use TWH leadership skills to initiate a new policy or program to protect and promote employee health. | One time within 60 days | 5 (12.8%) | |

| Coordinate your TWH team | Assigning a TWH team lead(s) and meeting with the team lead(s) monthly for the next 3 months to discuss our TWH goals and progress. | You may not be the point person for your TWH program. However, as a TWH leader you must be in touch and in the know. Check in frequently. If you don’t have a lead, designate one! | One time within 90 days | 13 (33.3%) | |

|

| |||||

| TWH Culture | Incorporate TWH values into business mission/vision | Updating business’s mission/vision statement to include shared TWH values | The first step is baking it into the heart of your business. Show your commitment by including TWH as part of your core mission and vision. | Onetime within 30 days | 5 (17.2%) |

| Share TWH leadership program | Sharing what I learned in the TWH leadership training with my employees, and steps I am taking as a result of the training. | Your employees should know what steps you are taking to address employee TWH. Use existing ways to share why it’s important - newsletters, meetings, evaluations, casual conversation & signage. Consistent and frequent communication matters. | Onetime within 30 days | 5 (17.2%) | |

| Identify the needs and interests of your employees | Meeting with employee(s) at least 1 time per week to define their TWH needs and interests. | Use your TWH leadership skills to actively ask and listen to your employees. Make sure you get different views to inform how to best meet the needs and interests of your employees. | Weekly for 30 days | 15 (51.7%) | |

| Incorporate work-life balance expectations into business | Write a formal company work/life balance expectation statement | Employees all have unique work/life balance challenges. As a TWH leader you can facilitate employee work/life balance by communicating expectations formally. | Onetime within 30 days | 2 (6.9%) | |

| Share TWH expectations | Sharing my values for TWH and communicating expectations with my employees. | It is important that your employees know your values for and expectations around TWH. Consistent and frequent communication matters. | Weekly for 90 days | 2 (6.9%) | |

| Define positive and negative feedback processes | Identify three ways to regularly give and receive constructive feedback on whether employees are meeting TWH expectations. | It is hard for you and your employees to learn and grow, if you/they do not know how you/they are doing. Determine the best methods for you to regularly give and receive constructive feedback. | Onetime within 30 days | 0 (0%) | |

| Display gratitude and recognition to employees | Recognize my employees’ achievements and display gratitude at least once a week as they work towards TWH goals. | Displaying appreciation is a good way to motivate employees to participate in the TWH program. | Weekly for 90 days | 0 (0%) | |

|

| |||||

| Self Health, Safety & Well-being | Personal health, safety, and well-being | Taking time to enhance my health, safety and well-being each week | TWH leadership starts with you. Consider what you personally need to do to make sure you are healthy and safe at work. | Weekly for 90 days | 27 (93.1%) |

| Define personal importance of health, safety, and well-being | Defining personal importance of health, safety and wellness for my business and write elevator pitch to share with employees. | TWH leadership starts with you. Take the time to evaluate why your employees’ safety, health and wellness matters to you, and communicate that to your employees. | Onetime within 30 days | 2 (6.9%) | |

Out of all of the goals that leaders set, the goal website data showed that there was an overall success rate of 27.8% (range = 0% - 100%). However, these data indicated that about 90% of the time leaders failed to meet their goal simply because they did not sign in into report on their goal progress. Qualitative information collected during coaching sessions indicated that some participants made progress on their goals despite not reporting goal attainment online. Leaders commonly reported working though the steps needed to meet their goals either on their own or with a safety and health committee or senior leadership team. They often found it easier to work on their personal health goals than their business or culture goals, citing more control over their own actions. For example, a few leaders reported that scheduled meetings to discuss their business and culture goals were cancelled due to competing business priorities. Leaders who reported no progress during coaching sessions cited barriers similar to those mentioned above (e.g., stress and too much work).

We evaluated the implementation fidelity of the goal setting website using website data (RQ4). Thirty participants (78.9%) logged into the online goal setting website at least one time after the in-person training. Those participants who did not log in cited that they did not want to add another website to their work life, that they used a different system already to track time management and they incorporated their TWH goals into that system, and they did not have time. Six leaders (17%) set stakes on at least one of their goals and all of them lost money due to not reporting their progress. Thirteen leaders (37%) invited supporters to help them meet their goals.

We evaluated leaders’ reaction to the goal setting website (RQ2) with survey data collected three months after the program. The evaluation of the online goal setting website showed neutral to slightly positive ratings. The average rating of the goal setting website was 3.40 out of 5.00 (SD = 1.00, α = 0.93) with ratings ranging from a 3.00 for the item stating they used the online goal setting website to enhance their business’s culture of health and safety to 3.80 for the item stating the online goal setting website was of high quality (see Table 2 in Online Resource 3). Feedback provided in respondents’ comments focused mainly on how the website prompted them to log in and update their progress. Comments ranged from they received too many email reminders, text messages would have been more effective, and reminders came on days they were out of the office (e.g., travel, weekends) so they failed to log in in a timely manner. For example, one leader wrote, “It was helpful to have weekly reminders to stay on track, but there were several weeks during the course of follow up where I was out of the office and the reminders that I had not submitted my report only added more stress (and nothing had changed since the previous report since I was not at work).”

Coaching

We assessed leaders’ reaction to the coaching component of the intervention (RQ2) as well as the fidelity of coaching implementation (RQ4). Eighteen participants (47.4%) completed one or more coaching session. Of those, eight people (44.4%) participated in only one session, and five people (27.8%) participated in two sessions and another five people (27.8%) participated in three sessions. Of those people who indicated why they did not participate in coaching, lack of time was the most cited reason. For example, one leader wrote, “Not enough time. My job is already overwhelming and adding something else (although very important) did not rise to the top due to trying to keep the organization running and fires from happening.” For those people who did participate in coaching, their feedback was positive. The average rating of the coaching sessions was 4.32 out of 5.00 (SD = 0.57, α = 0.94), and ratings ranged from 3.93 for the overall rating for coaching sessions to 4.57 for the item stating coaching sessions helped them maintain their awareness of Total Worker Health leadership (see Table 3 in Online Resource 3). Open-ended comments indicated that participants found the coaching sessions to be a useful tool to support their TWH initiatives and they appreciated the opportunity to reflect on their progress.

Leader pairs

Finally, we assessed leaders’ reaction to training with leaders (n = 30, 78.9%) who attended the program with another person from their organization (RQ2). Items measuring how well the leader pairs worked together during the program were asked immediately after the in-person training and again three months later in the follow up. The average rating of the program’s ability to facilitate shared leadership during the in-person training was 4.44 out of 5.00 (SD = 0.28, α = 0.71). Three months later, ratings for related items were lower. The average rating of the leader pair’s collaboration in the three months after the in-person training was 4.04 out of 5.00 (SD = 0.73, α = 0.80). Table 4 in Online Resource 3 presents all ratings for the shared leadership evaluation.

DISCUSSION

The implementation and effectiveness of TWH interventions depend on organizational leaders who are committed to workforce health, safety, and well-being. This is the first study to evaluate an approach to building TWH leadership capacity, specifically in small businesses. Our results suggest that the TWH leadership development program is effective at improving leaders’ self-reported TWH leadership practices and that the in-person training was implemented successfully. It also suggests the potential usefulness of training of multiple leaders per organization to build TWH leadership capacity in small business. Leaders reported a reduction in stress at home, but no improvements in other modifiable health risk factors. In fact, they reported more work-related stress after the program. We also observed some challenges when implementing our training transfer strategies. Overall these findings demonstrate the benefits and challenges of implementing a TWH leadership development program amongst small business leaders.

Our results demonstrate that the TWH leadership program enhances leaders’ self-reported TWH leadership practices but that it also increases their work-related stress, which provides partial support for our first hypothesis. Prior occupational health and safety leadership interventions also found improvements in leader self-reported outcomes (Mullen & Kelloway, 2009; Schwatka et al., 2019; von Thiele Schwarz, Hasson, & Tafvelin, 2016). As addressed in our first research question (RQ1), this finding may be due to leaders following through with their stated intentions to transfer the training to their job immediately after the training. It may also be due in part to the fact that over two-thirds of the leaders indicated that they were ready to make a change in the way the lead for TWH. However, to our knowledge, this is the first TWH study to understand the effects of TWH leadership development on leader modifiable health risk factors, in particular on leaders’ work-related stress. Barling et al.’s (2017) review may help explain why we observed an increase in leaders’ self-reported work-related stress. They note that there is a potential cost of high quality leadership in the form of increased responsibility, cognitive complexity of work, difficult goals, and emotional labor. Thus, while leaders in our study may have reacted favorably to our training and reported improving their TWH leadership practices from before to after the training, the challenges of implementing these practices may have caused some stress. Indeed, stress was reported as the most common implementation barrier as addressed in research question 2 (RQ2). Alternatively, it may be that leaders’ personal demands and resources in their home lives impacted the level of stress they feel at work. However, due to the nature of our study design, it is hard to say whether the TWH leadership program or something else caused an increase in self-reported stress.

We found that the TWH leadership program, as designed, does not help improve modifiable health risks among small business leaders themselves, at least based on self-report data in the time frame of the study. Like typical workplace health promotion programs (McCoy, Stinson, Scott, Tenney, & Newman, 2014), we offered leaders a short health risk assessment, health education during the training, and coaching in the three months following the training. To help understand why leaders may not have improved their modifiable health risk factors, we reviewed what specific personal health goals leaders chose during the in-person training. As noted in the results, 93% of leaders chose a goal about “personal health, safety, and well-being – take time to enhance my health, safety, and well-being each week.” Of the leaders that chose this goal and chose to customize it by writing in specific details about what they wanted to do to address this goal, over two-thirds of them specifically wrote about needing to “unplug” from work either in the form of taking a break during the day, limiting communication with employees after hours, or taking vacation or sick time. It may be that as leaders start to “unplug” they may have more time to address stress, sleep, exercise, and overall well-being. Thus, we hypothesize that we may need a longer amount of time to observe a change in these modifiable health risk factors as leaders work to “unplug” from their work.

For our third research question (RQ3), we aimed to assess what goals leaders set for themselves during the program. It is interesting to note that small business leaders chose goals for their TWH business strategy and culture that were foundational to integrating a TWH approach into their business strategy versus focused on implementing specific policies or practices. It was particularly encouraging to see that half of the leaders chose a goal around identifying the needs and interests of their employees as a first step in creating a culture of TWH. In a previous TWH leadership interview study with small business leaders, we found that leaders rarely spoke about TWH from the perspective of their employees (Thompson et al., 2018). Our findings indicate that the TWH leadership development program encourages small business leaders to strategically think about their business’s TWH strategy in the context of the needs and interests of their employees. This is encouraging as our TWH leadership program addresses calls for a TWH approach that incorporates participatory methods (Punnett et al., 2013).

Our final research question (RQ4) addressed whether each training program component was implemented as planned. In addressing this question, we demonstrate the challenges of training transfer strategies in the workplace. Many trainings commonly include goal setting as an effective method to facilitate training transfer (Johnson et al., 2012), but we are unaware of any published studies that included a website-based goal setting and tracking method like ours based on www.stickk.com. Drawing upon behavioral economics theory, Stickk helps individuals place value on future actions by setting the stakes on the goals they input into the website. The results of our study suggest that few leaders are willing to set the stakes during the training and the website user interface regarding goal reporting could be improved. McColl (2009) notes there is mixed evidence on whether this goal setting strategy helps improve health, but it can be a useful tool when used alongside other methods. In our study, leaders reacted more favorably to coaching than to the goal setting website. However, leaders noted that finding the time to do coaching was a challenge. Engaging senior organizational leaders in trainings is a common challenge and stresses the importance of creating trainings that accommodate their busy schedules and competing demands (Barling & Cloutier, 2017). It is important to note that despite these challenges, leaders reported high levels of training transfer activities three months after the in-person training (RQ1). This suggests that something else, such as personal motivation and a supportive work environment, may be helping leaders transfer the training to their job.

Strengths and weaknesses

This study represents the first study of TWH leadership development amongst small business leaders. A major strength of this study is the demonstration of how to implement this intervention in a small business sample. However, our intervention evaluation strategy had some limitations including the lack of a control group and a small sample size. While we had a control group for the broader SSWell study to evaluate changes in business- and employee-level outcomes, data on a control group were not collected as part of this leadership program evaluation study. Therefore, it is hard to determine whether the changes we observed in TWH leadership practices and stress were due to the intervention. Additionally, the small sample size may have limited our statistical power to test our hypothesis and generalizability of our research question findings. Relatedly, it is important to note that many of the leaders were ready to change the way they lead for TWH. Our study results may have been different had we enrolled leaders who were not interested in changing or were not yet ready to change. It is of particular note that the majority of leaders in our study were females. This is likely due to the industries that were most commonly represented in the study. For example, researchers who have studied other occupational health and safety leadership interventions in healthcare find high participation rates among women (Mullen & Kelloway, 2009) while researchers who study this in construction find high participation rates among men (Schwatka et al., 2019). Another potential limitation is participation bias as some leaders dropped out after enrolling in the program or did not complete all aspects of the program. However, there were minimal demographic differences between leaders that participated and those that did not. While a strength of our study is the focus on both effectiveness and implementation evaluation strategies, our data were based on self-reported surveys. Our study could have been strengthened if we included business- or employee-level outcomes. Finally, as described in the implementation results, our method of collecting data on goal attainment from the website data did not go as planned. However, during the coaching sessions leaders did verbally report progress on meeting their goals. Thus, we were limited in our ability to determine whether leaders did or not did meet their goals.

Future research

An important next step in the evaluation of this TWH leadership development program is to understand the mechanisms by which it coupled with a TWH intervention (Health Links) facilitates change in business TWH policies, procedures, and practices, employee perceptions of these practices, and employee health and safety outcomes (Kelloway & Barling, 2010; Schwatka et al., 2018). We are currently testing this in a sample of diverse small businesses, and we hypothesize that the key mechanism is a change in employee perceptions of safety climate and health climate (Schwatka et al., 2018). In other words, if a business undergoes organizational TWH change as a result of our intervention, employee perceptions that their organization is committed to their safety and health need to change for us to observe changes in employee health and safety outcomes.

One future avenue of TWH leadership development research should be understanding how to facilitate shared leadership amongst multiple individuals in an organization. Indeed, Ford et al. (2018) notes that training transfer may be enhanced if a team training approach is used. While we invited two leaders per organization to attend the program, we did not specifically design the program to facilitate coordinated leadership strategies. This was reflected in our findings three months after the in-person training where leaders noted only a moderate level of collaboration with the other leader in their organization. Unlike existing research on TWH participatory approaches where teamwork between multiple employees is promoted (Punnett et al., 2013), a shared leadership model of TWH leadership development would facilitate distributed influence and responsibility among team members. This may help to mitigate some of the work stress leaders reported after the program. Emerging evidence suggests that a shared leadership approach may be more effective than a focus on individual leadership development. The advantages of this approach to leadership development are that it can ensure program sustainability, management and labor joint-leadership, and it has the potential to enhance the effectiveness and innovativeness of TWH teams (D’Innovenzo, Mathieu, & Kurkenberger, 2016; Wu, Cormican, & Chen, 2018). It may also address known challenges and barriers for participants, such as work stress and lack of time.

Conclusions

Our study makes several important contributions to the TWH leadership development literature. It demonstrates preliminary evidence that a TWH leadership development program is effective at improving leaders’ self-reported TWH leadership practices. Our results suggest that this may be due to a high degree of readiness for change prior training and a high level of follow through with their stated intentions to transfer the training to their job after the in person training. However, the observed increase in leader work-related stress warrants further research to ensure leaders can implement new TWH leadership practices while successfully managing work-related stress. This may be especially important in the smallest businesses where manpower to implement TWH strategies is limited. Second, we show that this program, in particular the in-person training, can be implemented successfully. Third, our challenges with implementing the training transfer strategies suggest there is an opportunity for future research on how to help leaders transfer TWH leadership practices to their work. Finally, it suggests that leaders may benefit from attending TWH leadership trainings alongside other colleagues in their organization to facilitate a shared vision and goals for TWH in their organization. As a next step, it will be important to determine the program’s effectiveness in changing business TWH policies, procedures, and practices, employee perceptions of these practices, and employee health and safety outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement. On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Al-Eisa AS, Furayyan MA, & Alhemoud AM (2009). An empirical examination of the effects of self-efficacy, supervisor support and motivation to learn on transfer intention. Management Decision, 47(8), 1221–1244. doi: 10.1108/00251740910984514 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anger W, Rameshbabu A, Olson R, Bodner R, Hurtado D, Parker K, … Rohlman D (2019). Effectiveness of Total Worker Health interventions. In Hudson H, Nigam J, Sauter S, Chosewood L, Schill A, & Howard H (Eds.), Total Worker Health (pp. 61–89). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Bamberger PA, & Bacharach SB (2006). Abusive supervision and subordinate problem drinking: Taking resistance, stress, and subordinate personality into account. Human Relations, 59(6), 723–752. [Google Scholar]

- Barling J, & Cloutier A (2017). Leaders’ mental health at work: Empirical, methodological, and policy directions. J Occup Health Psychol, 22(3), 394–406. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes CM, Guarana CL, Nauman S, & Kong DT (2016). Too tired to inspire or be inspired: Sleep deprivation and charismatic leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(8), 1191–1199. doi: 10.1037/apl0000123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass B (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bronkhorst B, Tummers L, & Steijn B (2018). Improving safety climate and behavior through a multifaceted intervention: Results from a field experiment. Safety Science, 103, 293–304. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2017.12.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Casey TW, Krauss AD, & Turner N (2018). The one that got away: Lessons learned from the evaluation of a safety training intervention in the Australian prawn fishing industry. Safety Science, 108, 218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2017.08.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christian MS, Bradley JC, Wallace JC, & Burke MJ (2009). Workplace safety: a meta-analysis of the roles of person and situation factors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(5), 1103–1127. doi: 10.1037/a0016172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke S (2013). Safety leadership: A meta-analytic review of transformational and transactional leadership styles as antecedents of safety behaviours. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 86(1), 22–49. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8325.2012.02064.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke S, & Taylor I (2018). Reducing workplace accidents through the use of leadership interventions: A quasi-experimental field study. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 121, 314–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conchie SM (2013). Transformational leadership, intrinsic motivation, and trust: A moderated-mediated model of workplace safety. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 18(2), 198–210. doi: 10.1037/a0031805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham C, Woodward C, Shannon H, Lendrum B, Rosenbloom D, & Brown J (2002). Readiness for organizational change: A longitudinal study of workplace, psychological and behavioural correlates. Journal of Occupational & Organizational Psychology, 75(4), 377–392. [Google Scholar]

- Cutts TF, Gunderson GR, Proeschold-Bell RJ, & Swift R (2012). The life of leaders: an intensive health program for clergy. J Relig Health, 51(4), 1317–1324. doi: 10.1007/s10943-010-9436-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Innovenzo L, Mathieu J, & Kurkenberger M (2016). A Meta-Analysis of Different Forms of Shared Leadership–Team Performance Relations. Journal of Management, 42(7), 1964–1991. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger R, Huntinton R, Hutchinson SR, & Sowa D (1986). Percieved organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71, 500–507. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson W (2005). Work factors as predictors of smoking relapse in nurses’ aides. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 79(3), 244–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson A, Axelsson R, & Axelsson S (2010). Development of health promoting leadership – experiences of a training programme. Health Education, 110(2), 109–124. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher GG, Matthews RA, & Gibbons AM (2015). Developing and investigating the use of single-item measures in organizational research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 1–22. doi: 10.1037/a0039139 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ford JK, Baldwin TT, & Prasad J (2018). Transfer of Training: The Known and the Unknown. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav, 5(1), 201–225. [Google Scholar]

- Gaglio B, Shoup JA, & Glasgow RE (2013). The RE-AIM Framework: A Systematic Review of Use Over Time. American Journal of Public Health, 103(6), e38–e46. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2013.301299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow R, Vogt T, & Boles S (1999). Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: The RE-AIM framework. American Journal of Public Health, 89(9), 1322–1327. Retrieved from /pmc/articles/PMC1508772/?report=abstract [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin M, & Neal A (2000). Perceptions of safety at work: a framework for linking safety climate to safety performance, knowledge, and motivation. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 1, 347–358. Retrieved from http://0-search.ebscohost.com.catalog.library.colostate.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=cookie,ip,url,cpid&custid=s4640792&db=psyhref&AN=JOHP.A.CDG.GRIFFIN.PSWFLS&site=ehost-live [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover S, & Furnham A (2016). Coaching as a Developmental Intervention in Organisations: A Systematic Review of Its Effectiveness and the Mechanisms Underlying It. PLoS One, 11(7), e0159137. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer LB, Truxillo DM, Bodner T, Rineer J, Pytlovany AC, & Richman A (2015). Effects of a workplace intervention targeting psychosocial risk factors on safety and health outcomes. Biomed Res Int, 2015, 836967. doi: 10.1155/2015/836967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeschke KC, Kines P, Rasmussen L, Andersen LPS, Dyreborg J, Ajslev J, … Andersen LL (2017). Process evaluation of a Toolbox-training program for construction foremen in Denmark. Safety Science, 94, 152–160. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2017.01.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SK, Garrison LL, Hernez-Broome G, Fleenor JW, & Steed JL (2012). Go for the goal(s): Relationship between goal setting and transfer of training following leadership development. Academy of management learning and education, 11(4), 555–569. doi: 10.5465/amls.2010.0149 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karlin W, Brondolo E, & Schwartz J (2003). Workplace social support and ambulatory cardiovascular activity in New York City traffic agents. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65, 67–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelloway EK, & Barling J (2010). Leadership development as an intervention in occupational health psychology. Work and Stress, 24(3), 260–279. doi: 10.1080/02678373.2010.518441 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzes JM, & Posner BZ (2012). The leadership challenge: How to make extraordinary things happen in organizations (5th ed.). San Francisco: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Kuoppala J, Lamminp A, Liira J, & Vainio H (2008). Leadership, job well-being, and health effects - A systematic review and a meta-analysis. J Occup Environ Med, 50(8), 904–915. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31817e918d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson R, Stier J, Akerlind I, & Sandmark H (2015). Implementing Health-Promoting Leadership in Municipal Organizations: Managers’ Experiences with a Leadership Program. Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies, 5(1), 93–114. Retrieved from http://rossy.ruc.dk/ojs/index.php/njwls/article/view/4767/2452 [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Huang Y-H, Robertson MM, Murphy LA, Garabet A, & Chang W-R (2014). External validity of a generic safety climate scale for lone workers across different industries and companies. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 63, 138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2013.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnan L, Bowling M, Childress J, Lindsay G, Blakey C, Pronk S, … Royall P (2008). Results of the 2004 National Worksite Health Promotion Survey. American Journal of Public Health, 98(8), 1503–1509. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.100313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnan L, Vaughn A, Smith F, Westgate P, Hales D, Arandia G, … Ward D (2020). Results of caring and reaching for health (CARE): a cluster-randomized controlled trial assessing a worksite wellness intervention for child care staff. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act, 17(1), 64. doi: 10.1186/s12966-020-00968-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machin MA, & Fogarty GJ (2004). Assessing the antecedents of transfer intentions in a training context. International Journal of Training and Development, 8(3), 222–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-3736.2004.00210.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McColl K (2009). Betting on health. Bmj, 338, b1456. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy K, Stinson K, Scott K, Tenney L, & Newman LS (2014). Health promotion in small business: A systematic review of factors influencing adoption and effectiveness of worksite wellness programs. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 56(6), 579–587. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgeson FP, & Humphrey SE (2006). The Work Design Questionnaire (WDQ): Developing and validating a comprehensive measure for assessing job design and the nature of work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(6), 1321–1339. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.6.1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen J, & Kelloway E (2009). Safety leadership: A longitudinal study of the effects of transformational leadership on safety outcomes. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 82(2), 253–272. doi: 10.1348/096317908x325313 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen J, Kelloway K, & Teed M (2011). Inconsistent style of leadership as a predictor of safety behavior. Work and Stress, 25(1), 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Munir F, & Nielsen K (2009). Does self-efficacy mediate the relationship between transformational leadership behaviours and healthcare workers’ sleep quality? A longitudinal study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65(9), 1833–1843. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05039.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munir F, Nielsen K, & Carneiro IG (2010). Transformational leadership and depressive symptoms: A prospective study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 120(1–3), 235–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahrgang JD, Morgeson FP, & Hofmann DA (2011). Safety at work: A meta-analytic investigation of the link between job demands, job resources, burnout, engagement, and safety outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(1), 71–94. doi: 10.1037/a0021484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen K, Randall R, Yarker J, & Brenner S-O (2008). The effects of transformational leadership on followers’ perceived work characteristics and psychological well-being: A longitudinal study. Work and Stress, 22(1), 16–32. doi: 10.1080/02678370801979430 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- NIOSH. (2020). What is Total Worker Health? Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/twh/default.html

- Nyberg A, Alfredsson L, Theorell T, Westerlund H, Vahtera J, & Kivimaki M (2009). Managerial leadership and ischaemic heart disease among employees: the Swedish WOLF study. Occup Environ Med, 66(1), 51–55. doi: 10.1136/oem.2008.039362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punnett L, Warren N, Henning R, Nobrega S, Cherniack M, & CPH-NEW Research Team. (2013). Participatory ergonomics as a model for integrated programs to prevent chronic disease. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 55(12 Suppl), S19–24. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan M, Erck L, McGovern L, McCabe K, Myers K, Nobrega S, … Punnett L (2019). “Working on Wellness:” protocol for a worksite health promotion capacity-building program for employers. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 111. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6405-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwatka N, Atherly A, Dally MJ, Fang H, Brockbank C. v., Tenney L, … Newman LS (2017). Health risk factors as predictors of workers’ compensation claim occurrence and cost. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 74(1), 14–23. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2015-103334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwatka N, Goldenhar L, Johnson S, Beldon M, Tessler J, Dennerlein J, … Trieu H (2019). A training intervention to improve frontline construction leaders’ safety leadership practices and overall jobsite safety climate. Journal of Safety Research, 70, 253–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwatka N, Tenney L, Dally M, Scott J, Brown C, Weitzenkamp D, … Newman L (2018). Small business Total Worker Health: A conceptual and methodological approach to facilitating organizational change. Occupational Health Science, 2(1), 25–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore E, Schwatka N, Dally M, Brown C, Tenney L, & Newman L (2020). Small business employees perceptions of leadership are associated with safety and health climates and their own behaviors. Journal of Environmental and Occupational Medicine, 62(2), 156–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosik J, & Godshalk V (2000). Leadership styles, mentoring functions received, and job- related stress: A conceptual model and preliminary study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21, 365–390. [Google Scholar]

- Staehr J (1998). The use of well-being measures in primary health care-the DepCare project. World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe: Well-Being Measures in Primary Health Care-the DepCare Project Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Tenney L, Fan W, Dally M, Scott J, Haan M, Rivera K, … Newman L (2019). Health LinksTM assessment of Total Worker Health practices as indicators of organizational behavior in small business. Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine, 61(8), 623–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J, Schwatka N, Tenney L, & Newman L (2018). Total Worker Health: A Small Business Leader Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(11). doi: 10.3390/ijerph15112416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. (2020, July 29, 2019). 2016 SUSB annual data tables by establishment industry Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2016/econ/susb/2016-susb-annual.html [Google Scholar]

- von Thiele Schwarz U, Hasson H, & Tafvelin S (2016). Leadership training as an occupational health intervention: Improved safety and sustained productivity. Safety Science, 81, 35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2015.07.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]