Abstract

The restrictions triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic, especially during the first weeks of confinement in 2020, entailed marked changes concerning urban socio-spatial relations. This article analyzes perceptions of the importance of public space, neighbors' support, neighborhood safety, and home safety before and during the initial months of the COVID-19 lockdown. We conducted an online survey between March and April 2020 in Quito, Ecuador, and applied quantitative and spatial methods to analyze the perceptions. The results show statistically significant differences in neighbors’ support, home safety, and neighborhood safety between normal days and lockdown days. The perceptions of the public space as non-important before the lockdown and the perceptions of not being safe at home or in the neighborhood are spatially random, not concentrated in a specific area of the city. Our findings also show that gender, the importance of public space during normal days, and the willingness of neighbors to support each other on lockdown days could explain the perception of the importance of public space on lockdown days. This research provides unique information to contribute with perspectives and discussions of public space and social dynamics in pandemic and post pandemic times.

Keywords: COVID-19, Lockdown, Perceptions, Public space, Neighbor, Safety

1. Introduction

Public space is a concept that includes a diversity of places, such as streets and civic squares (Carmona, 2019), where the physical setting intertwines behaviors, affections, and cognitions (Aguila et al., 2019). The use of public space is strongly influenced by attachment to space and place identity (Purwanto & Harani, 2020), and place identity/attachment acknowledges the connection between people and places while considering both individual and community contexts (Brown et al., 2015; Raymond et al., 2010; Trentelman, 2009). Attachment and identity are dimensions of the subjective experience of perception of space. Perception of space refers to the meanings people can assign to a specific location based on spatial or physical experiences, as well as based on mental and emotional senses (Blaschke et al., 2018). Thus, place can be defined as belonging to a spatial metric but also as the mediator and influencer of social processes, that is to say, place is conceived as a location, as a setting for everyday-life activities, and as a sense of belonging or identification (sense of place) (Agnew, 2011). Space can be understood by humans in relation to the sense of place that inhabited and experienced (Song et al., 2013). Therefore, humans think the World in terms of places (Blaschke et al., 2018), where inter-connected people have place-specific social forms expressed in the space (P. F. Cabrera-Barona & Merschdorf, 2018). In this sense, the perceptions of urban spaces such as public spaces or neighborhoods are based on location (space) and at the same time based on the sense of place, the everyday-life, and the connections between people.

Experiences at a specific location (Backlund & Williams, 2003) and different scales, such as dwelling, neighborhood, city, and region (Cuba & Hummon, 1993; Hidalgo & Hernandez, 2001), shape the perceptions of space, and past experiences in a space influence cognitive responses to the current conditions of that space (Aguila et al., 2019). Thus, importance of a given space may remain even when the person is absent (Hidalgo, 2013). The public spaces may offer openness, democracy, and inclusiveness to construct social fabrics (Low & Smart, 2020), and is a collective space where social practices are expressed (Low, 1996), a space of encounters, relationships, and consumption (Ricart & Remesar, 2013), where identities and subjectivities are operated (Qian, 2020). These characteristics of public space might also be shared with the neighborhood, another key element of the urban system. The neighborhood is a concept that includes social and physical features (Brown et al., 2004) and can be evaluated trough diverse perceptions of place, such as perceived safety (Comstock et al., 2010), social cohesion and local health problems (Pampalon et al., 2007).

Since the public space is understood in a multifaceted way (Qian, 2020), perceptions of place can be very heterogeneous, due to for a single space, there are as many senses of place as individuals experiencing that space (P. F. Cabrera-Barona & Merschdorf, 2018). Certainly, variables such as gender and age impact the perception of place (Hidalgo & Hernandez, 2001; Lewicka, 2010). Moreover, public space perceptions could rely in factors such as openness, importance, safety, convenience, or visitability (Ho & Au, 2020; Mehta, 2014). The perceptions towards places such parks, green areas, squares, sidewalks, or playgrounds –considered as public spaces within this study– and the bonding experience with neighbors are dimensions of the urban experience concerning a specific context, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Analyzing perceptions of places during the COVID-19 lockdown is a key aspect to better understand human behaviors towards the urban environment in times of restricted mobility and social vulnerability that may support a better urban planning for more heathy, sustainable, and inclusive cities.

The COVID-19 expanded as a worldwide pandemic in 2020 (Bedford et al., 2020). Isolation, lockdowns, and social distancing were recommended as public health tools to tackle COVID-19 outbreaks (Wilder-Smith & Freedman, 2020). The socio-spatial restrictions, especially during the first weeks of lockdowns, entailed a radical change in social dynamics and people-environment relationships. In this context, the perceptions of safety became an important factor for urban residents. Carmona (2015) emphasizes that some problematics of public space are segregation and insecurity, factors that influence perceptions of a place. Previous research has also found lower levels of feelings of safety during the COVID-19 pandemic (Nouri & Kochel, 2022). Recognizing that the neighborhood scale is crucial for livable cities during the COVID-19 pandemic, Mouratidis and Yiannakou (2022) identify that neighborhood perceived safety, as well as neighborhood social cohesion and place attachment, shape urban residents’ quality of life.

From a situated perspective in the context of the COVID-19 crisis, Devine-Wright et al. (2020) identified three interdependent concepts of place-people bonds during the lockdown: emplacement-displacement, inside-outside, and fixity-flow. They mention that the applied fixities (e.g., home confinement) involve a re-assessment of the subjective meanings of the inside (e.g., home) and outside (e.g., workplaces, public spaces), and that the generation of unequal access to and exclusion from a place has a political dimension of emplacement-displacement. The study of Rogers et al. (2020) captured additional lockdown-induced dualities: visibility-invisibility, presence-absence, selfishness-solidarity, and privilege-privation. The authors mention the physical emptiness of the city caused a drastic change in the urban soundscape, and people could not move through the city as they used to. Thus, it is evident that during the COVID-19 crisis, the perceptions of places such as the home, the neighborhood, or the city have been altered in concordance with the experience of transitions from open spaces (e.g., public spaces) and working spaces toward enclosure and entrapment of private spaces (e.g., home). The altered life circumstances could have modified cognitions and behaviors, therefore changing perceptions of the importance of public space and other spaces such as neighborhood and home.

Honey-Rosés et al. (2020) identified emerging questions regarding the COVID-19 and the public space, including questions of socio-spatial changes and human practices. However, linking these questions with inquiries at neighborhood and household scales is important in terms of multi-scale urban evaluations, and have not been fully explored. Evaluating if perceptions of place at home and neighborhood scale (e.g., perceptions of safety and social cohesion) are determinants of perceptions of the importance of public space is an open question to be analyzed. Additionally, as previously mentioned, past experiences in a space could influence the current experiences in that space (Aguila et al., 2019; Hidalgo, 2013). The perceived importance of public space before and during the pandemic is also an open question. Furthermore, the spatial differences of the mentioned perceptions are an issue that needs to be explored. Certainly, the pandemic offered an increasing awareness of an emplaced existence and the connectedness between places, affecting livability and perceptions of place at different scales. Thus, the objective of this study is to assess the perceived importance of public space, neighborhood cohesion (represented by neighborhood support), neighborhood safety, and home safety in the context of the COVID-19 lockdown. Our hypotheses are the following:

-

1.

There are significant differences in the perceived importance of public space, neighbors' support, neighborhood safety, and home safety between the normal days (before lockdown) and lockdown days.

-

2.

The analyzed perceptions show clustered spatial patterns in the study area.

-

3.

The perceptions of public space importance on normal days, neighbors' support, home safety, and neighborhood safety influence the perceptions of the importance of public space in lockdown days.

2. Methods

We carried out a survey between March 20th and April 19th, 2020 (during the COVID-19 lockdown), for the city of Quito, Ecuador. Due to isolation measures and mobility restrictions implemented during the lockdown, we applied an online survey using a convenience sampling with a snowball strategy by distributing the survey through social networks and E-mail. The survey included 37 questions regarding socio-demographic features, perceptions of safety in the neighborhood and home, importance of public space, neighbors' support, use of private spaces, and mobility to food outlets (P. Cabrera-Barona & Carrión, 2020). For the present study, we used 11 questions, and these questions extracted information for lockdown days and for “normal days” (before de pandemic lockdown) of the following perceptions: importance of the public space, willingness of neighbors to support each other, neighborhood safety, and home safety. These questions used a Likert-scale of 4 levels or categories. For instance, in the case of the importance of public space for normal days, the question was “how important was for you the public space in normal days (before the pandemic lockdown)?”, and the response options were “non-important”, “little important”, “important”, “very important”; or in the case of the safety of neighborhood for lockdown days, the formulated question was “how safe is your neighborhood in days of pandemic lockdown?”, and the response options for this questions were “no safe”, “little safe”, “safe”, and “very safe”. Thus, we used 8 ordinal variables of perceptions of importance of public space, neighbors’ support, neighborhood safety and home safety for normal days and lockdown days. Additionally, we considered socio-demographic variables of gender, age, and ethnicity. Online surveys with a snowball strategy often obtain responses from locations different from the study area; consequently, not all responses are valid. We filtered the responses to restrict the sampling to Quito, obtaining 1001 valid answers. For privacy matters, the survey only requested general information regarding the main streets of residency. We developed a GIS-based programming code to generate the spatial coordinates of each response. With the geo-location of each response, we restricted the sample to the study area. Fig. 1 shows a representation of the study area and the data points (responses) obtained from the survey.

Fig. 1.

Study area and survey data points.

First, we calculated percentages for all the categories of the ordinal variables of the importance of public space, neighbors’ support, home safety and neighborhood safety, for normal days, and lockdown days. We also analyzed these variables by performing the technique of Quadrat Count (De Smith et al., 2018), with a hexagonal tessellation of 1 km radius. The value assigned to each tessellation is the absolute frequency per category of each variable under study. The Quadrat test applies the Chi-square test for spatial randomness and evaluates spatial patterns on points representing the categories of the ordinal variables. This test compares the distribution of a variable with a random distribution of Poisson simulated for the physical and statistical spaces. The null hypothesis is the spatial randomness. If the null hypothesis is rejected, there is a clustering pattern of the categories of the variable. The significance threshold considered was 95% of confidence. The calculations and maps of this test were performed with the R packages sf (Pebesma, 2018), statspat (Baddeley et al., 2016) and tmap (Tennekes, 2018). Additionally, to identify if significant differences of the studied variables between normal days and lockdown days exist, the Wilcoxon test was applied. The significance threshold considered for this analysis was 95% of confidence.

We also calculated an ordinal regression considering the perception of the importance of public spaces during the lockdown, as the dependent variable. A general analysis of the correlation of variables was applied prior to performing the regression. It was not our intention to perform a regression model representing all the population of Quito, but to offer an exploratory analysis of causality, useful for a better understanding of place perceptions in the city but limited to the sample data obtained in the present research.

The independent variables considered were perceptions of the importance of public space for normal days, and the perceptions of neighbors' support, home safety, and neighborhood safety, for lockdown days. The independent variable of importance of public space for normal days is valid for the regression model as previous research has shown that past-experiences influence the importance of public spaces during the lockdown (Backlund & Williams, 2003; Lewicka, 2008), and the independent variables of neighbors’ support and safety are useful for the model due to relationships with the community (Backlund & Williams, 2003; Trentelman, 2009), and safety expressed at different scales or levels, such as household and neighborhood levels (Cuba & Hummon, 1993; Hidalgo & Hernandez, 2001), are associated with perceptions of place. In the ordinal regression model we also included the independent variables of age, gender and ethnicity, due to these socio-demographic variables can also be used to assess the importance and the preference for a place (Hidalgo & Hernandez, 2001; Lewicka, 2010).

The ordinal regression model can be expressed with the following equation:

Where represents the ordinal dependent variable with their categories , is the model threshold, and represents the different independent variables with their coefficients. We considered significant the independent variables with levels of significance lower than 0.05 (95% of confidence or higher).

3. Results

In this section, first we present descriptive statistics, including the percentages of the categories of the variables of the importance of public space, the variable of neighbors’ support, and the variables of home/neighborhood safety. Second, we show the statistical and spatial results of the Quadrat test. Third, the results of the Wilcoxon test are shown. Finally, the outcomes of the regression model are presented.

For this study, 64.1% of respondents are female, 35.5% are male, 0.4% are of other gender. The average age is 38.4 years old ±0.4 standard error. The age of respondents ranges from 14 to 74, where 69% of respondents are 26–50 years old, 16% of respondents are 25 or younger, and 15% of respondents are 51 or older. The 91.6% of respondents are mestizos (mixed ethnicity), 1.9% are indigenous, 0.9% are afro-Ecuadorians, 4.3% are white, and 1.3% are of another ethnicity.

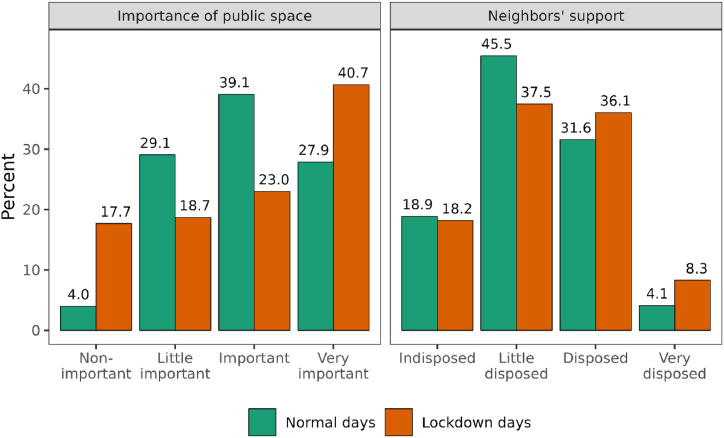

Fig. 2 shows percentages for the importance of public space and the willingness of neighbors to support each other. In the case of the importance of public space, 27.9% and 40.7% of respondents consider public space as very important during normal days and during the lockdown, respectively. Additionally, 4% consider public space as non-important for normal days, and 17.7% consider this type of space as non-important during the lockdown. The mode (predominant perception) for the importance of public space for normal days is “important” while for lockdown days is “very important”. Regarding the willingness of neighbors to support each other, 8.3% reported that their neighbors are very disposed to collaborate during the lockdown, in contrast with the 4.1% of respondents that gave this same answer for normal days. The mode for neighbors’ support in normal days and lockdown days is “little disposed”.

Fig. 2.

Perceptions of the importance of public space and willingness of neighbors to support each other, for normal days and lockdown days.

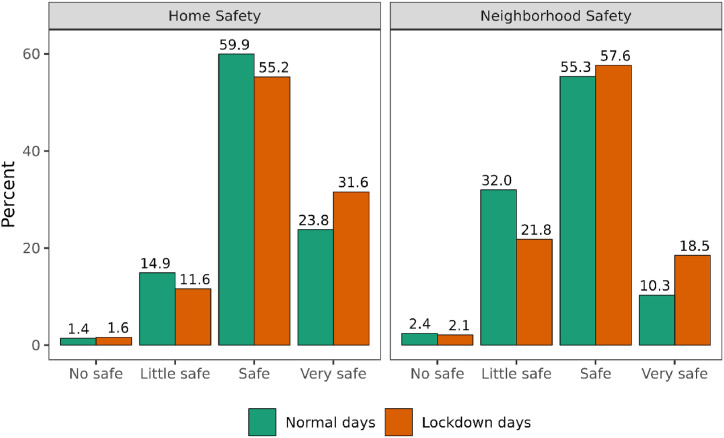

Fig. 3 shows the perceptions of home and neighborhood safety, for normal days and lockdown days. Herein, 31.6% responded that their home is very safe during the lockdown, while 23.8% consider their home as very safe in normal days. In the case of neighborhood safety, 18.5% of people think that their neighborhood is very safe during the lockdown, while in the case of normal days, the 10.3% of respondents consider their neighborhood as very safe. The mode for home and neighborhood safety, for normal days and for lockdown days, is “safe”.

Fig. 3.

Perceptions of home and neighborhood safety, for normal days and lockdown days.

Fig. 4 depicts the Quadrat test-based spatial representations of perceptions of the importance of public space and the willingness of neighbors to support each other (neighbors' support). In Fig. 4, the darker the yellow-orange color range, the higher the clustering of the category of the variable. We did not identify any cluster of the category of non-important (public space), for normal days. Table 1 shows the p-values of the Quadrat test by category of importance of public space and neighbors' support, for normal and lockdown days. The p-values lower than 0.05 mean spatial clustering. The calculated p-values found are significant except for the perception of public space as non-important for normal days: the answers for this category are spatially random, before lockdown. The variable of willingness of neighbors to support each other (neighbors’ support) shows significance for all their categories, before and during the lockdown, which means a spatial clustering of this variable.

Fig. 4.

Quadrat counts spatial representations of perceptions of the importance of public space and willingness of neighbors to support each other, for normal days and lockdown days.

Table 1.

Chi-square p-values by category of importance of public space and neighbors’ support, for normal and lockdown days.

| Variable | Category | p-value (normal days) | p-value (lockdown days) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Importance of public space | Non-important | 0.744 | 0.001 |

| Little important | 0.001 | 0.027 | |

| Important | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Very important | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Neighbors' support | Indisposed | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Little disposed | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Disposed | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Very disposed | 0.007 | 0.005 |

Fig. 5 depicts Quadrat test-based spatial representations of the studied perceptions of safety, the darker the yellow-orange color range, the higher the clustering of the category of the ordinal variables of safety. High spatial clustering for the category of safe, for both home and neighborhood, is visualized. Table 2 shows the p-values of the Quadrat test. All the p-values are significant except for the category of no safe. Hence, the perceptions of not feeling safe at home and the neighborhood are not clustered around any specific sector, these perceptions are spatially random in the study area.

Fig. 5.

Quadrat counts spatial representations of perceptions of home and neighborhood safety, for normal days and lockdown days.

Table 2.

Chi-square p-values by category of neighborhood and home safety, for normal and lockdown days.

| Variable | Category | p-value (normal days) | p-value (lockdown days) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neighborhood safety | No safe | 0.843 | 0.153 |

| Little safe | 0.001 | 0.027 | |

| Safe | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Very safe | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Home safety | No safe | 0.302 | 0.349 |

| Little safe | 0.003 | 0.007 | |

| Safe | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Very safe | 0.001 | 0.001 |

Table 3 shows the p-values of Wilcoxon test to evaluate statistically significant differences of the perceptions between normal days and lockdown days. When the p-value is lower than 0.05, it can be concluded that there are significant differences of the variable between normal and lockdown days. The obtained results indicate significant differences in perceptions of all variables, with the exception of the importance of public space.

Table 3.

Wilcoxon test.

| Variable | p-value |

|---|---|

| Public space importance | 0.17 |

| Neighbors' support | 0.00 |

| Home safety | 0.00 |

| Neighborhood safety | 0.00 |

Table 4 shows the regression results. The variables that could explain variations of the importance of public space during the lockdown are gender, importance of public space for normal days, and neighborhood support during the lockdown. The results of the significant variables can be interpreted as follows:

-

1.

The relative odds of perceiving the public space as important during the lockdown are 1.36 times greater for female respondents. In other words, the relative odds of perceiving the public space as important during the lockdown increases by 36% for women.

-

2.

The relative odds of perceiving high importance of public space during the lockdown are 1.97 times greater for people perceiving high importance of public space for normal days than for those reporting low importance of public space for normal days.

-

3.

The relative odds of perceiving high importance of public space during the lockdown are 35% higher for people perceiving the willingness of neighbors to support each other than for those who perceived poor neighbors' support during the lockdown.

Table 4.

Results of the ordinal regression.

| Variable | Odds ratio | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1.36* | 1.07 | 1.73 |

| Age | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.00 |

| Ethnicity | 1.12 | 0.97 | 1.31 |

| Public space importance (normal days) | 1.97** | 1.69 | 2.28 |

| Neighbors' support | 1.35** | 1.18 | 1.55 |

| Home safety | 1.21 | 0.96 | 1.54 |

| Neighborhood safety | 0.97 | 0.77 | 1.23 |

Levels of significance: **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

Our research contributes with empirical data to the provocative and genuinely relevant thoughts, perspectives and discussions of public space during the COVID-19 pandemic (Honey-Rosés et al., 2020; Jasiński, 2020; Low & Smart, 2020). The study analyzed the importance of public space, neighbors' support (as a variable of social cohesion), and safety perceptions and contributes to the analyses of place and public space in the context of the 2020 COVID-19 lockdown. There are several remarkable results of this research. First, we identified statistically significant differences of perceptions of neighbors' support, home safety, and neighborhood safety between normal and lockdown days. Second, the perceptions of considering the public space as non-important for the time before the lockdown, and the perceptions of not being safe at home or in the neighborhood are spatially random, that is, are not clustered in any specific sector of the city. Third, the variables of gender, perceptions of the importance of public space for normal days and the perceptions of neighbors’ support could influence the perceptions of the importance of public space for lockdown days.

Acuto et al. (2020) argue that if we see COVID-19 as a “city”, we can achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the urban complexity and have a better urban response to the pandemic. If the city can be interpreted as an arena of social networks, where the willingness to support neighbors is a component of these networks, the identified significant differences of neighbors’ support and home/neighborhood safety between normal days and lockdown days suggest a modification of the urban social settings along with a disruption of places such as homes as safe places athwart the public space. In contrast, surprisingly, we did not find significant differences in the perceptions of the importance of public space between normal and lockdown days. This finding indicates that the public space is considered important for some people independently of lockdown measures, and is in line with the finding of Paköz et al. (2022) regarding the use of public space. Using an online survey with 337 participants, considering residential and individual features, these authors did not find significant differences in the use of public spaces between days before and after the COVID-19 outbreak, except for the variable of gender.

Borja (2011) argues that the city is the public space, and the public space is the city, which is a condition, an expression, and a means of contestation of modern citizenship. In this sense, the public space may be seen as the “city context”, independently of the lockdown or normal days. We found an increment of perceptions of neighborhood safety and neighbors’ support for lockdown days in compared with normal days that suggest a better predisposition for social cohesion within the neighborhood during the pandemic. However, as Acuto (2020) comments, a greater community building remains to be seen in the city, in the context of COVID-19. The higher level of feeling very safe at home for lockdown days compared to normal days, demonstrates that home was a symbol of protection during the pandemic. Indeed, home and the neighborhood, for the increasing needs of personal safety and health during the pandemic, became places of safety (Devine-Wright et al., 2020), in accordance with a re-evaluation of the “quality of places” in the urban space (Salama, 2020). Our finding of the spatial patterns of the perceptions of safety also reveals socio-spatial implications of the pandemic lockdown. The perceptions of not being safe at home or in the neighborhood are spatially random, while the perceptions of safety are clustered, which indicates socio-spatial segregations of perceptions of home safety and neighborhood safety, a finding that suggests urban inequalities. These inequalities could be exacerbated with the changing of habits in terms of post-lockdown new spatial patterns of environments (e.g., home environment) as the products of previously applied distancing measures (Salama, 2020).

The results of the performed regression showed relevant factors in explaining the importance of public space for lockdown days. These results suggest that being women, considering public spaces as very important for normal days, and perceiving disposition of neighbors to support each other, are statistically significant variables to explain the importance of public spaces for lockdown days. Although conservative social practices have assigned women to the private domain and men to the public domain, the significance of the gender variable found in this research are in line with previous investigation showing that women are involved in diverse and complex uses of urban public spaces (Franck & Paxson, 1989). During the lockdown, the changes in social practices and domestic roles had gender implications, including increased violence against women (Mittal & Singh, 2020; Usta et al., 2021). Thus, our finding regarding gender is striking due to the importance for women in accessing to public space beyond the private space, due this latter space could be a space that in some cases perpetuate patriarchal and violent practices against women.

Some women may have perceived a higher longing for the public space during the lockdown, due to feelings of insecurity and fear inside households. Moreover, lockdown isolated vulnerable women and disconnected them from their support networks (Mittal & Singh, 2020), and, in general, the pandemic could have more marked negative effects in the use of public spaces for women than for men (Paköz et al., 2022). Our investigation confirms the need of women of accessing save public spaces. Age and ethnicity were not found significant to explain importance of public space. Most of inhabitants of Quito are of mixed ethnicity, thus, the variable of ethnicity has not variations that could influence perceptions of place at ecological level (not individual). In the case of age, most of respondents' ages range between 26 and 50, and those 25 or younger, and 51 or older, did not present important differences of perceptions between normal and lockdowns days, excepting for the case of older adults in relation to the variable of neighbors’ support.

Regarding public spaces, even though active engagement was restricted during the lockdown, our regression results suggest that pre-pandemic positive ideas of public space were maintained during the lockdown. This finding supports Low and Smart (2020) opinion that the social spaces (e.g., public spaces) “will come back” after the pandemic, as a “constant” feature of the urban fabric aiming at. Thus, people that agree with these attributes may have retained their feelings during the lockdown.

In 2020, social segregation was augmented due to the social distancing measures applied in the public space (Jasiński, 2020). In this sense, finding that the willingness of neighbors to support each other could increase the perceptions of the importance of public space, can be interpreted as a coping mechanism for social segregation during the COVID-19 crisis. Trust and solidarity between neighbors could shape the public space, and social cohesion may have tackled the COVID-19 crisis of minimizing the role of the public space. Despite the setback of the public space during a lockdown, maintaining neighbors’ cooperation and positive perspectives of public space may have helped to start regaining the public spaces for our everyday life in future cities.

Qian (2020) claims that public space is an ideological space of power relations and differences. The identified differences in perceptions between normal days and lockdown days and the significance of gender and neighbors’ support in the perception of public space represent, to some extent, power relations in the pandemic society. The public space needs to be seen as the opportunity to create and develop social and political networks to make cities more resilient and livable in the face of social-environmental risks and changes. Indeed, Sepe (2021), in the context of the Charter of Public Space presented at the Quito Habitat 3 Conference, claims that, due to the pandemic, the adequate use of public spaces needs to be associated with the adaptability to environmental disasters and pandemic emergencies.

This study has some limitations. The applied survey is an online convenience survey, which is why the results of the regression model do not lay claim to generalizability, and future studies may corroborate the significant independent variables found in this investigation. The considered socio-demographic variables may not fully represent the complexity of socio-demographic and economic factors that could influence the perceptions of the importance of public space. Future research would need to consider additional confounders in the proposed regression model and explore gender-based and age-based differences of the use of public space and perceptions of safety. Additionally, this research does not analyze the role of virtual spaces as displacements of traditional public spaces. Although the virtual spaces are not yet completely set to replace the unpredictability and inclusiveness of the public space (Low & Smart, 2020), many urban functions and services are being digitalized or becoming virtual (Jasiński, 2020). Future studies could study the role of virtual spaces as “urban arenas” for COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 times. Future investigations may also consider specific perceptions, in the sense of capturing, for instance, perceptions of safety for specific features of home and neighborhood. Additionally, future research could incorporate social-environmental variables as covariables to explain the importance of public space.

All in all, the present study reports important differences of perceptions of place in the context of the pandemic COVID-19, with an emphasis in public space. The understanding of these differences may support ideas for a better design of public space and planning of urban safety in post-pandemic cities.

5. Conclusions

During the COVID-19 crisis, especially during the 2020 lockdown, mobility restrictions and social isolation modified several perceptions of urban residents. Regarding the hypothesis of this study, we conclude that:

-

1.

There are significant differences of neighbors' support, neighborhood safety and home safety between normal days, and lockdown days. There are no significant differences in the perceived importance of public space between normal days and lockdown days.

-

2.

The analyzed perceptions have a spatial clustering pattern, except the category of public space as non-important before the lockdown, and the category of not being safe at home or in the neighborhood.

-

3.

The perceptions of public space importance on normal days and neighbors' support may influence the perceptions of the importance of public space for lockdown days. Home safety and neighborhood safety do not influence the perceptions of the importance of public space for lockdown days. However, gender is a variable that could also influence the importance of public space.

We identified a valorization of the public space during the lockdown days, the relevance of home or neighborhood symbolizing a refuge during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the willingness of neighbors to support each other that reflects some degree of social cohesion during the lockdown. The perception of public space has gendered and social cohesion implications and responds to the perspectives of the importance of this kind of space before the lockdown. We aim to acknowledge the value of the public space, the benefits of social cohesion, and the need for secure neighborhoods to support better planning and urban management. The city requires public policies that recognize the interdependences between neighborhood communities and public spaces. The design of new spaces should integrate diverse perceptions and perspectives, recognizing gender-based needs and guaranteeing adaptability in the contexts of potential drastic socio-environmental changes such as pandemics and extreme climate. Scholars, stakeholders, and decision-makers must interpret the city as a complex system where key elements (e.g., public spaces) need to be adjusted to support individual and collective health and well-being.

Declarations of competing interest

None.

References

- Acuto M. COVID-19: Lessons for an urban(izing) World. One Earth. 2020;2(4):317–319. doi: 10.1016/j.oneear.2020.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acuto M., Larcom S., Keil R., Ghojeh M., Lindsay T., Camponeschi C., Parnell S. Seeing COVID-19 through an urban lens. Nature Sustainability. 2020;3(12):977–978. doi: 10.1038/s41893-020-00620-3. Nature Research. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Agnew J. In: Handbook of geographical knowledge. Agnew J., Livingstone D., editors. Sage; 2011. Space and place. [Google Scholar]

- Aguila M.D., Ghavampour E., Vale B. Theory of place in public space. Urban Planning. 2019;4:249–259. doi: 10.17645/up.v4i2.1978. 2 Public Space in the New Urban Agenda Research into Implementation. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Backlund E., Williams D. Proceedings of the 2003 northeast recreation research symposium. 2003. A quantitative synthesis of place attachment research: Investigating past experience and place attachment. [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley A., Rubak E., Turner R. CHAPMAN & HALL CRC; 2016. Spatial point patterns: Methodology and applications with R.http://book.spatstat.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Bedford J., Enria D., Giesecke J., Heymann D.L., Ihekweazu C., Kobinger G., Lane H.C., Memish Z., Oh M., Sall A.A., Schuchat A., Ungchusak K., Wieler L.H. COVID-19: Towards controlling of a pandemic. The Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1015–1018. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30673-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaschke T., Merschdorf H., Cabrera-Barona P., Gao S., Papadakis E., Kovacs-Györi A. Place versus space: From points, lines and polygons in GIS to place-based representations reflecting language and culture. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2018;7(11) doi: 10.3390/ijgi7110452. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borja J. Espacio público y derecho a la ciudad. Viento Sur. 2011:39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Brown G., Brown B.B., Perkins D.D. New housing as neighborhood revitalization: Place attachment and confidence among residents. Environment and Behavior. 2004;36(6):749–775. doi: 10.1177/0013916503254823. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown G., Raymond C.M., Corcoran J. Mapping and measuring place attachment. Applied Geography. 2015;57:42–53. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2014.12.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera-Barona P., Carrión A. Voiding public spaces, enclosing domestic places: Place attachment at the onset of the pandemic in Quito, Ecuador. Journal of Latin American Geography. 2020 doi: 10.1353/lag.0.0145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera-Barona P.F., Merschdorf H. A conceptual urban quality space-place framework: Linking geo-information and quality of life. Urban Science. 2018;2(3) doi: 10.3390/urbansci2030073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carmona M. Re-Theorising contemporary public space: A new narrative and a new normative. Journal of Urbanism. 2015;8(4):373–405. doi: 10.1080/17549175.2014.909518. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carmona M. Principles for public space design, planning to do better. Urban Design International. 2019;24(1) doi: 10.1057/s41289-018-0070-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Comstock N., Miriam Dickinson L., Marshall J.A., Soobader M.-J., Turbin M.S., Buchenau M., Litt J.S. Neighborhood attachment and its correlates: Exploring neighborhood conditions, collective efficacy, and gardening. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2010;30(4):435–442. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cuba L., Hummon D.M. A place to call home: Identification with dwelling, community, and region. The Sociological Quarterly. 1993;34(1):111–131. www.jstor.org/stable/4121561 [Google Scholar]

- De Smith M.J., Goodchild M.F., Longley P. 2018. Geospatial analysis: A comprehensive guide to principles, techniques and software tools. [Google Scholar]

- Devine-Wright P., Pinto De Carvalho L., Masso A.Di, Lewicka M., Manzo L., Williams D.R. Re-placed”-Reconsidering relationships with place and lessons from a pandemic. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2020;72 doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franck K.A., Paxson L. In: Public places and spaces. Altman I., Zube E.H., editors. Springer US; 1989. Women and urban public space; pp. 121–146. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo M.C. Operationalization of place attachment: A consensus proposal. Studies in Psychology. 2013;34(3):251–259. doi: 10.1174/021093913808295190. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo M.C., Hernandez B. Place attachment: Conceptual and empirical questions. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2001;21(3):273–281. doi: 10.1006/JEVP.2001.0221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ho R., Au W.T. Scale development for environmental perception of public space. Frontiers in Psychology. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.596790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honey-Rosés J., Anguelovski I., Chireh V.K., Daher C., Konijnendijk van den Bosch C., Litt J.S., Mawani V., McCall M.K., Orellana A., Oscilowicz E., Sánchez U., Senbel M., Tan X., Villagomez E., Zapata O., Nieuwenhuijsen M.J. The impact of COVID-19 on public space: An early review of the emerging questions – design, perceptions and inequities. Cities & Health. 2020:1–17. doi: 10.1080/23748834.2020.1780074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jasiński A. Public space or safe space – remarks during the COVID-19 pandemic. Technical Transactions. 2020 doi: 10.37705/TechTrans/e2020020. 20200020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewicka M. Place attachment, place identity, and place memory: Restoring the forgotten city past. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2008;28(3):209–231. doi: 10.1016/J.JENVP.2008.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewicka M. What makes neighborhood different from home and city? Effects of place scale on place attachment. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2010;30(1):35–51. doi: 10.1016/J.JENVP.2009.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Low S. Spatializing culture: The social production and social construction of public space in Costa Rica. American Ethnologist. 1996;23(4):861–879. doi: 10.1525/ae.1996.23.4.02a00100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Low S., Smart A. Thoughts about public space during covid-19 pandemic. City and Society. 2020;32(1) doi: 10.1111/ciso.12260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta V. Evaluating public space. Journal of Urban Design. 2014;19(1):53–88. doi: 10.1080/13574809.2013.854698. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal S., Singh T. Gender-based violence during COVID-19 pandemic: A mini-review. Frontiers in Global Women’s Health. 2020;1 doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2020.00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouratidis K., Yiannakou A. What makes cities livable? Determinants of neighborhood satisfaction and neighborhood happiness in different contexts. Land Use Policy. 2022;112 doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nouri S., Kochel T.R. Residents' perceptions of policing and safety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Policing. 2022;45(1):139–153. doi: 10.1108/PIJPSM-05-2021-0067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paköz M.Z., Sözer C., Doğan A. Changing perceptions and usage of public and pseudo-public spaces in the post-pandemic city: The case of istanbul. Urban Design International. 2022;27(1):64–79. doi: 10.1057/s41289-020-00147-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pampalon R., Hamel D., De Koninck M., Disant M.-J. Perception of place and health: Differences between neighbourhoods in the Québec City region. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;65(1):95–111. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pebesma E. Simple features for R: Standardized support for spatial vector data. The R Journal. 2018;10(1):439. doi: 10.32614/rj-2018-009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Purwanto E., Harani A.R. Understanding the place attachment and place identity in public space through the ability of community mental map. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2020;402(1) doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/402/1/012024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qian J. Geographies of public space: Variegated publicness, variegated epistemologies. Progress in Human Geography. 2020;44(1):77–98. doi: 10.1177/0309132518817824. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond C.M., Brown G., Weber D. The measurement of place attachment: Personal, community, and environmental connections. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2010;30(4):422–434. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ricart N., Remesar A. Reflexiones sobre el espacio público. On the W@terfront. 2013;25:5–35. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers D., Herbert M., Whitzman C., McCann E., Maginn P.J., Watts B., Alam A., Pill M., Keil R., Dreher T., Novacevski M., Byrne J., Osborne N., Büdenbender M., Alizadeh T., Murray K., Dombroski K., Prasad D., Connolly C.…Caldis S. The city under COVID-19: Podcasting as digital methodology. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie. 2020;111(3):434–450. doi: 10.1111/tesg.12426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salama A.M. Coronavirus questions that will not go away: Interrogating urban and socio-spatial implications of COVID-19 measures. Emerald Open Research. 2020;2:14. doi: 10.35241/emeraldopenres.13561.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sepe M. Covid-19 pandemic and public spaces: Improving quality and flexibility for healthier places. Urban Design International. 2021;26(2):159–173. doi: 10.1057/s41289-021-00153-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song G., Janowicz K., McKenzie G., Li L. Towards platial joins and buffers in place-based GIS. Proceedings of The First ACM SIGSPATIAL International Workshop on Computational Models of Place. 2013 doi: 10.1145/2534848.2534856. 42–49. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tennekes M. tmap: Thematic maps in R. Journal of Statistical Software. 2018;84(6) doi: 10.18637/jss.v084.i06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trentelman C.K. Place attachment and community attachment: A primer grounded in the lived experience of a community sociologist. Society & Natural Resources. 2009;22(3):191–210. doi: 10.1080/08941920802191712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Usta J., Murr H., El-Jarrah R. COVID-19 lockdown and the increased violence against women: Understanding domestic violence during a pandemic. Violence and Gender. 2021;8(3):133–139. doi: 10.1089/vio.2020.0069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilder-Smith A., Freedman D.O. Isolation, quarantine, social distancing and community containment: Pivotal role for old-style public health measures in the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak. Journal of Travel Medicine. 2020;27(2) doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]