Résumé

Position du problème

Après l'annonce de la pandémie de COVID-19 en mars 2020, le programme de dépistage du cancer colorectal (CCR) a été suspendu dans plusieurs pays. Comparativement aux lésions cancéreuses détectées précédemment (2017 à 2019), l’étude évalue la gravité des CCR détectés en 2020 en Île-de-France, région la plus touchée par la 1ère vague de la pandémie.

Méthodologie

L'étude descriptive et étiologique a inclus tous les tests de dépistage (FIT), réalisés entre janvier-2017 et décembre-2020 par des personnes d’Île-de-France, âgées de 50-74 ans. D'abord, la proportion de coloscopies réalisées dans le mois; le taux de détection de la Coloscopie (Nb_néoplasmes/Nb_coloscopies)) et la sévérité du CCR (Classification TNM, Niveau-0: T0/N0/M0, Niveau-1: T1/T2/N0/M0, Niveau-2: T3/T4/N0/ M0 ; Niveau-3: T3/T4/N1/M0 ; Niveau-4: M1) ont été décrites en 2020 comparativement aux 3 précédentes campagnes. Puis, le lien entre le niveau de gravité du CCR et les facteurs prédictifs, notamment l'année de campagne et délai d'accès à la coloscopie, a été analysé en régression polytomique multivariée.

Résultats

La différence de proportions de coloscopies réalisées dans le délai d'un mois (2017: 9,1% de 11529 coloscopies; 2018: 8,5% de 13346; 2019: 5,7% de 7881; 2020: 6,7% de 11040; p<0,001), le taux de détection de la coloscopie (respectivement: 65,2%; 64,1%; 62,4%; 60,8%, p<0,001) étaient significativement différent entre campagnes. La proportion de CRC de niveau-4 (4,8% en 2017 (653 CCR); 7,6% en 2018 (674 CCR); 4,6% en 2019 (330 CCR) et 4,7% en 2020 (404 CCR); p<0,29) n'était pas significativement différente entre campagnes. La probabilité d'avoir un CCR de gravité élevé était inversement proportionnelle au délai d'accès à la coloscopie mais non liée à l'année de campagne. Comparativement aux patients ayant réalisé une coloscopie dans le mois, l’ odds était significativement réduit de 60% pour les coloscopies réalisées après >7 mois (adjusted Odds-Ratio: 0,4 [0,3; 0,6]; p<0,0001).

Conclusions

En France, les indicateurs évalués étaient dégradés avant la première vague de COVID-19. Le délai d'accès et son allongement induit par COVID-19 n'avaient pas d'impact sur la gravité des CCR, probablement à cause d'une démarche de discrimination priorisant les patients ayant des symptômes apparents.

Mots clés: Dépistage du cancer colorectal, Gravité du cancer colorectal, Test Faecal immunochimique, Délai d'accès à la coloscopie, COVID-19

Abstract

Background

After the announcement in March 2020 of the COVID-19 pandemic, colorectal cancer screening programs were suspended in several countries. Compared to the lesions detected during previous campaigns, this study aims to assess the severity of CRC detected during the 2020 screening campaign in Île-de-France, the region most affected by the 1st wave of the pandemic.

Methods

The descriptive and etiological study included all faecal immunochemical test (FIT) results carried out between January 2017 and December 2020 on people aged 50-74, living in Île-de-France. First, the proportion of colonoscopies performed within one month (One-month-colo) following FIT; the yield of Colonoscopy (Nb_neoplasms/Nb_colonoscopies)) and CRC severity (TNM Classification, Level-0: T0/N0/M0, Level-1: T1/T2/N0/M0, Level-2: T3/T4/N0/M0; Level-3: T3/T4/N1/M0; Level- 4: M1) were described in 2020 compared to previous campaigns (2017, 2018, and 2019). Subsequently, the link between the level of CRC severity and the predictive factors, including campaign year and time to colonoscopy, was analysed using polytomous multivariate regression.

Results

The one-month-colo (2017: 9.1% of 11,529 colonoscopies; 2018: 8.5% of 13,346; 2019: 5.7% of 7,881; 2020: 6.7% of 11,040; p<0.001), the yield (65.2%, 64.1%, 62.4%, 60.8% respectively, p<0.001) were significantly different between campaigns. The proportion of CRC level-4 (4.8% in 2017 (653 CRC); 7.6% in 2018(674 CRC); 4.6% in 2019 (330 CRC) and 4.7% in 2020 (404 CRC); p<0.29) was not significantly different between campaigns. The probability of having CRC with a high severity level was inversely related to the time to colonoscopy but not to the campaign year. Compared to patients having undergone colonoscopy within 30 days, the odds were significantly reduced by 60% in patients having undergone colonoscopy after 7 months (adjusted Odds-Ratio: 0.4 [0.3; 0 .6]; p<0.0001).

Conclusions

The French indicators were certainly degraded before the first wave of the COVID-19. The delay in access to colonoscopy as well as its extension induced by the COVID-19 crisis had no impact in terms of cancer severity, due to a discriminatory approach prioritizing patients with evident symptoms.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer screening, Colorectal cancer severity, Faecal immunochemical tests, Time to screening colonoscopy, COVID-19

1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer and the second deadliest in the world [1]. However, after the World Health Organization (WHO) announcement in March 2020 of the global COVID-19 pandemic and the reallocation of healthcare resources to control this infection, cancer screening programs, in particular CRC screening programs, were suspended in many countries [2].

The consequences of this suspension are being analysed in most programs around the world. In addition to the lengthening of the interval between two screening rounds due to the postponement of campaign invitations, the fear of infection by the coronavirus may also have affected patients’ recourse to colonoscopy after a positive test, as hypothesized in a previous study [3].

Similarly, the risk of contamination of gastroenterologists by the COVID-19 virus during an endoscopic examination increased because of the presence of the virus in droplets of saliva and faeces [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]. To minimize this risk during endoscopic practice, in mid-April 2020 the French Society of Digestive Endoscopy (SFED) and the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) published recommendations limiting the influx of people in endoscopy departments [5,10].

The SFED issued the specific recommendation to postpone by 6 weeks any colonoscopy following a positive screening test if there were no clinical and biological signs of CRC. According to Belle et al. [11], these recommendations, which came out only one month after the declaration of the pandemic situation by the WHO, probably led to significantly reduced endoscopic activity in France. Assuming that 2 to 3 months of activity were lost during the pandemic, while the incidence of digestive pathologies and the total number of patients had not changed, Ponchon & Chaussade suggested a hierarchy of priorities in endoscopy units [12].

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the European guide for quality assurance in colorectal cancer screening recommended performance of a colonoscopy within 31 days following a positive test result [13]. In patients with a positive faecal immunochemical test result, compared with follow-up colonoscopy at 8 to 30 days, follow-up after 10 months is associated with a higher risk of colorectal cancer and more advanced-stage disease at the time of diagnosis [14]. Lengthy delays in access to colonoscopy were observed in patients with a positive Guaiac (gFOBT) test when they first took part in screening campaigns [15]. This delay was significantly higher in Ile-de-France region (IDF) following introduction of the faecal immunochemical test (FIT) OC-Sensor® in the French population-based CRC screening program (CRCSP) [16].

The hypothesis that these program quality indicators, particular as regards CRC severity, were worse in 2020 has not yet been investigated in France, particularly in IDF, which was inevitably the French region most affected by the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic [17]. Compared to CRC cases detected during previous campaigns, this study aims to assess the severity of CRC detected during 2020, which was likely to have been affected by the Covid-19 health crisis.

2. Methods

2.1. Study type and population

The descriptive and etiological study included all FITs performed between Jan-2017 and Dec-2020 on people aged 50-74 living in the 8 departments (Paris, Seine-et-Marne, Yvelines, Essonne, Hauts-de-Seine, Seine-Saint-Denis, Val-de-Marne and Val-d'Oise) of the IDF region, France. First, the indicators (number of FITs completed, proportion of FITs that could not be analysed by the laboratory (T-NA), proportion of positive FITs, colonoscopy completion rate, time to colonoscopy after a positive FIT result, yield of colonoscopy and severity of neoplasm lesions) were described in 2020 as compared to previous campaigns (2017, 2018, and 2019). In a second step, an etiological analysis of CRC severity was made according to time to colonoscopy adjusted to year of FIT.

2.2. Screening campaign organization and data sources

The medical demographic data are those made available by the study department of the French National Order of Physicians. The data of screening and follow-up of positive test results were extracted from the departmental databases on the same date : January 28, 2022. Following the CRCSP specifications [18,19], the screening campaigns were organized in IDF by the IDF Regional Cancer Screening Coordination Center (CRCDC-IDF). As a preliminary to each campaign, an update of the files of eligible people was made after transmission of individual data by the program partners (health Insurance plans (HIS), hospital medical information services, anatomo-pathologists, gastroenterologists, surgeons, GPs, patients). In France, the contract concluded in 2014 between the National Health Insurance agency and the Cerba-Daklapack® consortium recommends supply of screening test kits by the consortium and analysis of their results by a single laboratory (CERBA). Regardless of habitual residence, any test carried out at home by an eligible person must be sent to the laboratory within at most six days. In the screening campaign, the FITs that could not be analysed (T-NA) by the laboratory had either expired, or arrived at the laboratory without a collection date, or arrived at the laboratory more than 6 days after collection of the stool sample, or not analysed by the laboratory for any other reason. The FIT positivity threshold was set at 150ng of haemoglobin/ml of stool (“Institut National du Cancer”, www.e-cancer.fr).

2.3. Definition of variables

2.3.1. Dependent variable

The colonoscopy was classified as positive when a neoplasm lesion (Polyp/adenoma or CRC) was found, negative if not. Colonoscopy yield was estimated in terms of the proportion of positive colonoscopies among the colonoscopies performed. The diagnoses associated with CRC and polyps/adenomas were those related to C18–C20 and D12 in the 10th version of the World Health Organization's International Classification of Diseases (ICD10) [20]. Adenomas ≥ 10 mm (except hyperplastic polyps), serrated adenomas, adenomas with high grade dysplasia, villous or tubulo-villous adenomas were classified as high-risk polyps (HRP). CRC lesions were characterized in terms of stage of severity, using the tumour, node and metastasis (TNM) classification based on tumour size, lymph node involvement and possible presence of metastases [21]. Level-0 : CCR (T0) without lymph node involvement (N0/M0) ; Level-1 : CCR (T1/T2) without lymph node involvement (N0/M0) ; Level-2 : CCR (T3/T4) without lymph node involvement (N0/M0) ; Level-3 : CRC (T1-T4) with nodal involvement ; Level-4 : CRC with metastasis (M1). Cancers with unknown or unspecified stage (NR) were excluded from the severity assessment.

2.3.2. Independent variables

The main factors studied were FIT completion year and time to access colonoscopy.

The (complete or incomplete) colonoscopy chosen was the one performed after a positive FIT. The colonoscopy completion rate was expressed by the proportion of people having had a colonoscopy to people with a positive test result. Time to colonoscopy was expressed as the number of months between the date of the screening test and the date of the colonoscopy. In the cases where several colonoscopies were carried out to investigate the same positive test result, the time retained by the study pertained to the first colonoscopy.

Time to colonoscopy was first described in mean and standard deviation according to : i) place of performance of the colonoscopy : 1-private clinic in IDF ; 2-private hospitals in IDF ; 3-Paris University Hospital Center –APHP–, 4-other public hospitals in IDF including : army hospitals and municipal health centers, 5-another France region, 6- unspecified place or outside of France ; ii) the proximity of the place of performance of the colonoscopy : 1- the patient's municipality of residence, 2-other municipalities in the patient's department of residence, 3-other departments in the IDF region, 4-another French region, 5- unspecified place or outside of France ; iii) density (D) of GEs in the patient's municipality of residence, estimated as number of GEs/100,000 inhabitants with reference to a regional average range of 5.5 to 7.5 GEs/100,000 inhabitants (no GEs : D=0, low density of GEs : D <5.5GE/100,000 inhabitants, average-density : D between 5.5 and 7.5GE/100,000 inhabitants, High density of GEs D > 7.5GE/100,000 inhabitants).

Subsequently, the time to colonoscopy was coded as a discrete variable ( ≤ 1 month ; 1-3 months ; 4-7 months and ≥ 8 months).

The adjustment factors studied in the etiological analysis were : i) gender (female vs. male) ; ii) age (50-54, 55-59, 60-64, 65-69, ≥ 70 years) ; iii) number (0, 1, ≥ 2) of screening tests completed before those of which the positivity prompted the colonoscopy ; iv) the relevant compulsory health insurance schemes : 1- General schemes, 2- “Mutuelle Générale de l'Education Nationale”(MGEN) or "Mutuelle de la Fonction Publique” (MFP) , 3-“Régie Autonome des Transports Parisiens”(RATP) or "Société Nationale des Chemins de Fer”(SNCF), 4-Other schemes ;

2.3.3. Statistical analysis

The colonoscopy completion rate, the yield of colonoscopy and the proportions of lesions (adenoma and CRC) were described and compared between years (2017-2020) using the Pearson Chi-2 test. Similarly, in the strata defined according to patient characteristics, comparison of the proportions between years was made by the Pearson Chi-2 test.

The colonoscopy completion times (in months), expressed as a mean and confidence interval (CI), were compared between years (2017-2020) by an analysis of variance (one-factor ANOVA). Similarly, in the strata defined according to patient characteristics and GE, comparison of the mean delays between years was made by a one-factor ANOVA.

The relationship between CRC severity (ordinal variable 0 to 4) and predictive factors (time to colonoscopy, age, gender, number of previous tests completed, health insurance schemes) was analysed using a polytomous multivariate regression model. The campaign year (2017 to 2020) was introduced as an independent variable in this multivariate regression analysis. Multivariate analysis was performed using a model with all covariates and an interaction variable between age and number of tests. The model was evaluated by the likelihood ratio test.

All the analyses were carried out at the 5 % threshold with version 13 of the STATA software (College Station, Texas, USA).

2.3.4. Regulatory issues

Before analysis, all data were anonymized. The screening database had a favourable opinion from the institution that oversees the ethics of data collection (“Commission nationale de l'informatique et des libertés” : CNIL) [22]. According to current French legislation, a study that does not change patient care does not require the opinion of a clinical research center's ethics committee. This article does not contain any studies with human participants conducted by any of the authors. As the study does not involve human participants, informed consent was not required. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

3. Results

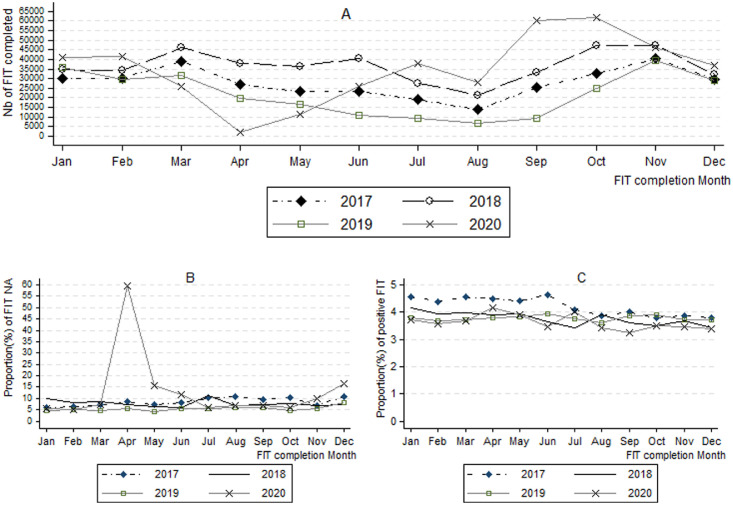

All in all, 333,579 FITs were performed in 2017, including 8.3 % (27,659 tests) of T-NA. The proportion of T-NA was 7.7 % in 2018 (438,378 FIT performed), 5.4 % in 2019 (262,994) and 8.3 % in 2020 (418,547). This proportion of T-NA, which was in continuous decline between 2017 and 2019 (significant decrease between 2017 and 2018, p<0.001, then a significant drop between 2018 and 2019, p<0.001) recorded a significant jump between 2019 and 2020, p<0.001. The proportion of positive tests (4.2 % in 2017 ; 3.8 % in 2018 and 2019 ; 3.5 % in 2020) was significantly (p<0.001) lower in 2020 compared to each of the previous three years. The distribution of these indicators by month and year of test completion is shown in Figure-1 . In April 2020, only 2282 FITs were completed in IDF (Figure-1-A) with a proportion of T-NA that reached a record of 59 % (Figure-1-B). The proportion of positive tests was higher in the first six months of 2017 (Figure-1-C).

Figure 1.

Number of Fecal immunochemical tests (FIT) completed (A), proportion of FITs not analyzed (B) and proportion of positive FITs (C) by month and year of the screening test.

More than four fifths (82.1 %) of the 14,047 people with a positive test in 2017 underwent a colonoscopy. Colonoscopy completion rate was 80.9 % in 2018 (16496 positive tests), 79.6 % in 2019 (9906 positive tests) and 74.5 % in 2020 (14,813 positive tests) ; p<0.001.

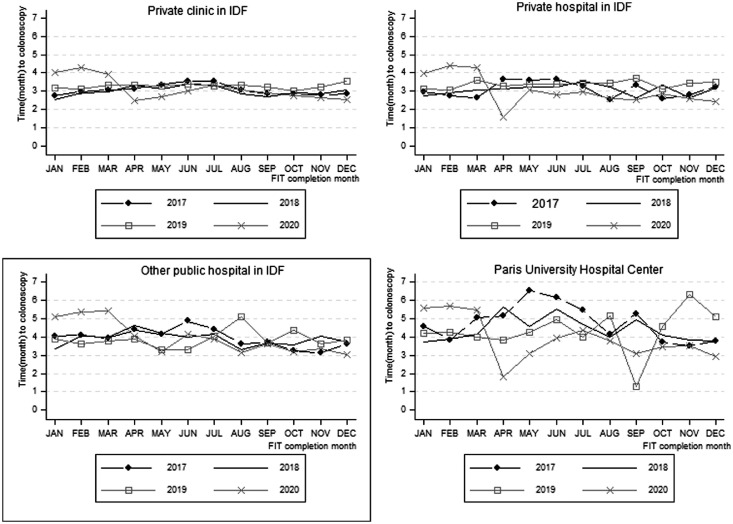

The proportion of colonoscopies performed within one month was lower in 2019 (5.7 % of 7881 colonoscopies) and 2020 (6.7 % of 11,040 colonoscopies) compared to 2017 (9.1 % of 11,529 colonoscopies) and 2018 (8.5 % out of 13,346 colonoscopies) ; p<0.001. Distribution by campaign year of the proportion of colonoscopies completed in the one-month delay is summarized in Table-1 . The average time to colonoscopy was significantly different between campaign years. Average time was 4.8 months for the 458 colonoscopies performed at the Paris University Hospital Centre in 2017. For the colonoscopies performed at the Paris University Hospital Centre, the difference in time to colonoscopy was not significant (p=0.48) between campaign years (Table-2 ). The evolution of the average time to colonoscopy according to place of colonoscopy, by month and campaign year is summarized in Figure-2 .

Table 1.

The colonoscopy completion rate by year of completion of the positive screening FIT.

| Characteristics | Year of completion of the positive FIT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | P* | |

| Nb of T+ (Colo-Rate in %) | Nb of T+ (Colo-Rate in %) | Nb of T+ (Colo-Rate in %) | Nb of T+ (Colo-Rate in %) | ||

| Overall | 14 047 (82.1) | 16 496 (80.9) | 9906 (79.6) | 14 813 (74.5) | <10-3 |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 6333 (82.8) | 7577 (82.1) | 4649 (80.2) | 6911 (76.0) | <10-3 |

| Male | 7714 (81.5) | 8919 (79.8) | 5257 (78.9) | 7902 (73.1) | <10-3 |

| Age (year) | |||||

| 50 - 54 | 3473 (81.0) | 3422 (79.0) | 2229 (78.9) | 3161 (74.1) | <10-3 |

| 55 – 59 | 2602 (81.7) | 3130 (80.2) | 2009 (77.4) | 2885 (73.1) | <10-3 |

| 60 – 64 | 2723 (82.9) | 3305 (81.4) | 1882 (81.5) | 2885 (74.6) | <10-3 |

| 65 - 69 | 2976 (83.1) | 3507 (81.9) | 1879 (79.8) | 2909 (74.9) | <10-3 |

| ≥ 70 | 2273 (81.5) | 3132 (81.6) | 1907 (80.0) | 2973 (75.5) | <10-3 |

| Nb of previous FIT | |||||

| 0 | 6088 (77.4) | 5548 (74.8) | 3154(74.2) | 4382 (70.5) | <10-3 |

| 1 | 2660 (82.0) | 3347 (80.1) | 2420 (78.1) | 3128 (72.3) | <10-3 |

| ≥ 2 | 5299 (87.3) | 7601 (85.6) | 4332 (84.1) | 7303 (77.8) | <10-3 |

| Health Insurance Schemes | |||||

| General Schemes | 11 884 (81.3) | 14 008 (80.3) | 8550 (78.7) | 13 216 (74.0) | <10-3 |

| MGEN/MFP | 1109 (87.8) | 1212 (85.2) | 662 (85.1) | 786 (78.1) | <10-3 |

| RATP/SNCF | 243 (81.9) | 247 (82.6) | 162 (84.6) | 192 (79.7) | 0.69 |

| Other Schemes | 811 (84.1) | 1029 (82.3) | 532 (83.5) | 619 (77.2) | 0.005 |

| Density GE/5000Hbts in patient's municipality of residence | |||||

| No GE | 5961 (85.2) | 7033 (84.1) | 4473 (82.3) | 6369 (76.7) | <10-3 |

| Low density | 3250 (82.3) | 3651 (79.4) | 2078 (76.7) | 3385 (72.1) | <10-3 |

| Average Density | 664 (84.2) | 916 (83.8) | 637(80.5) | 732 (74.5) | <10-3 |

| High density | 4172 (77.0) | 4896 (76.6) | 2718 (76.6) | 4327 (73.0) | <10-3 |

*Pearson chi2 ; Colo-Rate : Colonoscopy completion rate ; FIT : Fecal immunochemical test ; GE : Gastroenterologist ; iHbts : inhabitants ; MFP : Mutuelle de la Fonction Publique ; MGEN : Mutuelle Générale de l'Education Nationale ; Nb : Number ; T+ : positive FIT ; RATP : Régie Autonome des Transports Parisiens ; SNCF : Société Nationale des Chemins de Fer.

Table 2.

Time to colonoscopy after positive FIT by year of completion of the positive screening test.

| Characteristics | Year of completion of the positive screening FIT. | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | P1* | P2** | |||||

| Nb of colo (% TC ≤ 1 month) | ATC [CI95 %] | Nb of colo (% TC ≤ 1 month) | ATC [CI95 %] | Nb of colo (% TC ≤ 1 month) | ATC [CI95 %] | Nb of colo (% TC ≤ 1 month) | ATC [CI95 %] | |||

| Overall | 11 529 (9.1) | 3.3 [3.2 ; 3.4] | 13 346 (8.5) | 3.3 [3.2 ; 3.3] | 7881 (5.7) | 3.6 [3.5 ; 3.7] | 11 040 (6.7) | 3.5 [3.4 ; 3.6] | <10-3 | <10-3 |

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Female | 5244 (9.7) | 3.3 [3.2 ; 3.4] | 6222 (9.0) | 3.2 [3.1 ; 3.2] | 3732 (6.1) | 3.5 [3.4 ; 3.6] | 5252 (6.6) | 3.5 [3.4 ; 3.5] | <10-3 | <10-3 |

| Male | 6285 (8.6) | 3.3 [3.2 ; 3.4] | 7124 (8.1) | 3.3 [3.3 ; 3.4] | 4149 (5.3) | 3.6 [3.5 ; 3.7] | 5788 (6.8) | 3.5 [3.5 ; 3.6] | <10-3 | <10-3 |

| Age (year) | ||||||||||

| 50 - 54 | 2816 (8.7) | 3.5 [3.3 ; 3.6] | 2705 (8.3) | 3.5 [3.3 ; 3.6] | 1760 (6.1) | 3.6 [3.4 ; 3.7] | 2345 (6.7) | 3.7 [3.6 ; 3.8] | <10-3 | 0.19 |

| 55 – 59 | 2127 (8.7) | 3.2 [3.1 ; 3.4] | 2514 (9.2) | 3.4 [3.2 ; 3.5] | 1556 (4.1) | 3.8 [3.6 ; 4.0] | 2108 (5.8) | 3.5 [3.4 ; 3.6] | <10-3 | <10-3 |

| 60 – 64 | 2256 (9.7) | 3.2 [3.1 ; 3.4] | 2693 (8.1) | 3.1 [3.0 ; 3.3] | 1536 (5.0) | 3.5 [3.3 ; 3.7] | 2156 (6.7) | 3.5 [3.4 ; 3.6] | <10-3 | <10-3 |

| 65 - 69 | 2476 (9.6) | 3.2 [3.2 ; 3.4] | 2875 (9.0) | 3.2 [3.1 ; 3.3] | 1502 (6.2) | 3.4 [3.2 ; 3.5] | 2179 (7.8) | 3.4 [3.3 ; 3.5] | <10-3 | 0.008 |

| ≥ 70 | 1854 (9.1) | 3.2 [3.1 ; 3.3] | 2559 (8.1) | 3.1 [3.0 ; 3.2] | 1527 (6.9) | 3.6 [3.4 ; 3.7] | 2252 (6.3) | 3.4 [3.3 ; 3.5] | <10-3 | <10-3 |

| Nb of previous FIT | ||||||||||

| 0 | 4717 (9.5) | 3.5 [3.4 ; 3.6] | 4150 (8.8) | 3.5 [3.4 ; 3.6] | 2343 (6.1) | 3.7 [3.5 ; 3.8] | 3091 (6.7) | 3.6 [3.5 ; 3.7] | <10-3 | 0.34 |

| 1 | 2183 (9.1) | 3.3 [3.2 ; 3.5] | 2683 (7.6) | 3.3 [3.2 ; 3.4] | 1894 (5.3) | 3.6 [3.5 ; 3.8] | 2265 (6.1) | 3.6 [3.5 ; 3.7] | <10-3 | <10-3 |

| ≥ 2 | 4629 (8.8) | 3.1 [3.0 ; 3.2] | 6513 (8.7) | 3.1 [3.0 ; 3.1] | 3644 (5.6) | 3.5 [3.4 ; 3.6] | 5684 (6.8) | 3.4 [3.4 ; 3.5] | <10-3 | <10-3 |

| Health Insurance Schemes | ||||||||||

| General schemes | 9674 (9.5) | 3.3 [3.2 ; 3.4] | 11 261 (8.7) | 3.3 [3.2 ; 3.3] | 6737 (5.5) | 3.6 [3.5 ; 3.7] | 9795 (6.9) | 3.5 [3.4 ; 3.5] | <10-3 | <10-3 |

| MGEN/MFP | 974 (8.1) | 3.2 [3.0 ; 3.4] | 1033 (8.1) | 3.2 [2.9 ; 3.2] | 563 (7.8) | 3.3 [3.0 ; 3.6] | 614 (5.5) | 3.4 [3.2 ; 3.6] | 0.001 | 0.12 |

| RATP/SNCF | 199 (5.0) | 3.1 [2.7 ; 3.5] | 204 (4.9) | 3.2 [2.8 ; 3.5] | 137 (7.3) | 4.0 [3.3 ; 4.6] | 153 (5.9) | 3.5 [3.1 ; 3.9] | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| Other schemes | 682 (6.9) | 3.4 [3.1 ; 3.6] | 848 (7.3) | 3.4 [3.2 ; 3.6] | 444 (5.0) | 3.5 [3.2 ; 3.8] | 478 (4.6) | 3.7 [3.4 ; 3.9] | 0.005 | 0.33 |

| Place of colonoscopy completion | ||||||||||

| Private clinic in IDF | 7387 (9.7) | 3.1 [3.0 ; 3.2] | 8336 (9.2) | 3.1 [3.0 ; 3.1] | 4825 (6.5) | 3.4 [3.3 ; 3.5] | 6944 (7.4) | 3.4 [3.3 ; 3.5] | <10-3 | <10-3 |

| Private hospital in IDF | 1816 (11.9) | 3.2 [3.0 ; 3.3] | 2395 (9.6) | 3.1 [3.0 ; 3.3] | 1432 (5.3) | 3.5 [3.4 ; 3.7] | 2089 (7.2) | 3.4 [3.2 ; 3.5] | <10-3 | <10-3 |

| Paris University Hospital Center | 458 (4.6) | 4.8 [4.5 ; 5.2] | 512 (5.1) | 4.5 [4.2 ; 4.9] | 285 (3.5) | 4.7 [4.3 ; 5.1] | 419 (3.6) | 4.5 [4.2 ; 4.8] | 0.84 | 0.48 |

| Others public hospital in IDF | 1208 (4.3) | 4.0 [3.8 ; 4.2] | 1352 (4.7) | 4.0 [3.8 ; 4.2] | 905 (2.8) | 4.1 [3.8 ; 4.3] | 926 (3.1) | 4.2 [4.0 ; 4.3] | <10-3 | 0.69 |

| Another France region | 196 (5.1) | 4.0 [3.4 ; 4.6] | 284 (4.6) | 3.9 [3.4 ; 4.3] | 181 (2.2) | 4.6 [4.0 ; 5.1] | 285 (2.8) | 3.9 [3.6 ; 4.3] | 0.30 | 0.17 |

| Unspecified place | 464 (8.4) | 3.4 [3.0 ; 3.8] | 467 (7.9) | 3.1 [2.9 ; 3.4] | 253 (7.9) | 3.2 [2.8 ; 3.6] | 377(4.8) | 3.2 [2.9 ; 3.4] | 0.61 | 0.70 |

| Proximity of the place | ||||||||||

| Patient's municipality of residence | 3259 (10.0) | 3.1 [3.0 ; 3.2] | 3779 (8.9) | 3.1 [3.0 ; 3.2] | 2116 (6.1) | 3.3 [3.2 ; 3.4] | 3176 (7.2) | 3.4 [3.3 ; 3.5] | <10-3 | <10-3 |

| Other municipalities in the patient's department of residence | 5611 (7.9) | 3.4 [3.3 ; 3.5] | 6456 (8.2) | 3.3 [3.2 ; 3.4] | 3807 (5.0) | 3.8 [3.6 ; 3.9] | 5221 (6.4) | 3.6 [3.5 ; 3.7] | <10-3 | <10-3 |

| Other departments in the IDF | 1998 (11.7) | 3.4 [3.2 ; 3.5] | 2360 (9.4) | 3.3 [3.2 ; 3.4] | 1524 (6.6) | 3.5 [3.4 ; 3.7] | 1980 (7.6) | 3.5 [3.3 ; 3.6] | <10-3-3 | 0.20 |

| Density GE/5000Hbts in patient's municipality of residence | ||||||||||

| No GE | 5080 (8.3) | 3.3 [3.2 ; 3.4] | 5921 (7.7) | 3.3 [3.2 ; 3.4] | 3684 (5.2) | 3.6 [3.5 ; 3.8] | 4892 (6.4) | 3.6 [3.5 ; 3.7] | <10-3-3-3 | <10-3-3 |

| Low density | 2674 (8.6) | 3.5 [3.3 ; 3.6] | 2904 (8.8) | 3.4 [3.2 ; 3.5] | 1596 (5.9) | 3.6 [3.5 ; 3.8] | 2444 (6.1) | 3.5 [3.4 ; 3.6] | <10-3 | 0.10 |

| Average Density | 560 (7.9) | 3.4 [3.1 ; 3.7] | 770 (11.1) | 3.1 [2.9 ; 3.4] | 516 (4.5) | 3.5 [3.3 ; 3.8] | 545 (7.5) | 3.4 [3.2 ; 3.6] | <10-3 | 0.14 |

| High density | 3215 (11.1) | 3.1 [3.0 ; 3.2] | 3751 (9.1) | 3.1 [3.0 ; 3.2] | 2085 (6.7) | 3.5 [3.3 ; 3.6] | 3159 (7.4) | 3.4 [3.3 ; 3.5] | <10-3 | <10-3 |

*Pearson's Chi-square comparing the proportions of colonoscopies performed within one month ; ** Fisher's test (Prob > F) comparing average times to colonoscopy ; ATC : Average time (in month) to colonoscopy ; CI95 % : 95 % Confident interval ; Colo : Colonoscopy ; FIT : Fecal immunochemical test ; GE : Gastroenterologist IDF : Ile-de-France ; iHbts : inhabitants ; MFP : Mutuelle de la Fonction Publique ; MGEN : Mutuelle Générale de l'Education Nationale ; Nb : Number ; RATP : Régie Autonome des Transports Parisiens ; SNCF : Société Nationale des Chemins de Fer. TC : Time (in month) to colonoscopy.

Figure 2.

Time to colonoscopy according to the place of performance of the colonoscopy by month and year of the positive Fecal immunochemical test (FIT).

The yield of colonoscopy gradually decreased (p<0.0001), from 65.2 % in 2017 to 60.8 % in 2020. In 2018, the proportion of CRCs level-4 was : 15.7 % among the 70 CRCs (whose status was known) detected after a one-month waiting period for colonoscopy, 6.8 % among the 366 CRCs detected after a waiting time of > 1-3 months ; 5.4 % among the 184 CRCs detected after a waiting time of > 3-7 months, 7.9 % among the 38 cancers screened after a waiting time of > 7 months ; the difference was not significant (p=0.18) (Table-3 ).

Table 3.

Distribution of the number of neoplasms screened according to the time to colonoscopy by year of the positive FIT.

| Year of completion of the positive FIT | Time (in month) to colonoscopy | Time to colonoscopy unspecified | OVERALL | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 1Month | ]1-3M] | ]3-7M] | > 7M | P* | ||||

| 2017 | ||||||||

| Nb of colonoscopies | 1052 | 6428 | 3032 | 954 | 63 | 11 529 | ||

| Nb of neoplasms (YC in %) | 625 (59.4) | 4238 (65.9) | 1987 (65.5) | 632 (66.3) | 0.001 | 36 (57.1) | 7518 (65.2) | |

| Polyp : | Nb (% Adenoma) | 532 (53.6) | 3769 (56.8) | 1816 (56.8) | 560 (55.5) | 0.52 | 18 (38.9) | 6695 (56.4) |

| CRC : | Nb (% CRC-K) | 93 (73.1) | 469 (80.0) | 171 (80.7) | 72 (83.3) | 0.36 | 18 (66.7) | 823(79.3) |

| Nb CRC-K | 68 | 375 | 138 | 60 | 0.49 | 12 | 653 | |

| % CRC Level-0 | 23.5 | 28.5 | 27.5 | 35.0 | 0.0 | 27.9 | ||

| % CRC Level-1 | 22.1 | 29.3 | 31.9 | 28.3 | 16.7 | 28.8 | ||

| % CRC Level-2 | 20.6 | 18.7 | 14.5 | 18.3 | 33.3 | 18.2 | ||

| % CRC Level-3 | 23.5 | 19.2 | 21.7 | 16.7 | 41.7 | 20.4 | ||

| % CRC Level-4 | 10.3 | 4.3 | 4.4 | 1.7 | 8.3 | 4.8 | ||

| 2018 | ||||||||

| Nb of colonoscopies | 1137 | 7384 | 3720 | 1028 | 77 | 13 346 | ||

| Nb of neoplasms (YC in %) | 677 (59.5) | 4785 (64.8) | 2407 (64.7) | 641 (62.4) | 0.003 | 40 (52.0) | 8550 (64.1) | |

| Polyp : | Nb (% Adenoma) | 586 (49.7) | 4328 (54.8) | 2165 (54.3) | 591 (51.4) | 0.06 | 18 (27.8) | 7688 (54.0) |

| CRC : | Nb (% CRC-K) | 91 (76.9) | 457 (80.1) | 242 (76.0) | 50 (76.0) | 0.60 | 22 (72.7) | 862 (78.2) |

| Nb CRC-K | 70 | 366 | 184 | 38 | 0.18 | 16 | 674 | |

| % CRC Level-0 | 17.1 | 27.9 | 26.6 | 23.7 | 6.3 | 25.7 | ||

| % CRC Level-1 | 22.9 | 32.2 | 34.2 | 36.8 | 31.3 | 32.1 | ||

| % CRC Level-2 | 17.1 | 15.9 | 16.3 | 15.8 | 6.3 | 15.9 | ||

| % CRC Level-3 | 27.1 | 17.2 | 17.4 | 15.8 | 43.8 | 18.8 | ||

| % CRC Level-4 | 15.7 | 6.8 | 5.4 | 7.9 | 12.5 | 7.6 | ||

| 2019 | ||||||||

| Nb of colonoscopies | 446 | 4263 | 2316 | 824 | 32 | 7881 | ||

| Nb of neoplasms (YC in %) | 293 (65.7) | 2651 (62.2) | 1458 (63.0) | 498 (60.4) | 0.28 | 18 (56.3) | 4918 (62.4) | |

| Polyp : | Nb (% Adenoma) | 251 (53.4) | 2411 (53.1) | 1339 (54.3) | 458 (49.3) | 0.33 | 10(40.0) | 4469 (53.1) |

| CRC : | Nb (% CRC-K) | 42 (69.1) | 240 (71.3) | 119 (79.0) | 40 (80.0) | 0.29 | 8(50.0) | 449 (73.5) |

| Nb CRC-K | 29 | 171 | 94 | 32 | 0.03 | 4 | 330 | |

| % CRC Level-0 | 6.9 | 21.6 | 33.0 | 37.5 | 0 | 24.9 | ||

| % CRC Level-1 | 34.5 | 40.9 | 30.9 | 28.1 | 0 | 35.8 | ||

| % CRC Level-2 | 20.7 | 18.7 | 14.9 | 18.9 | 25.0 | 17.9 | ||

| % CRC Level-3 | 37.9 | 14.6 | 14.9 | 12.5 | 50.0 | 17.0 | ||

| % CRC Level-4 | 0 | 4.1 | 6.4 | 3.1 | 25.0 | 4.6 | ||

| 2020 | ||||||||

| Nb of colonoscopies | 736 | 5348 | 3866 | 1032 | 58 | 11 040 | ||

| Nb of neoplasms (YC in %) | 433 (58.8) | 3280 (61.3) | 2354 (60.9) | 616 (59.7) | 0.50 | 25(43.1) | 6695 (60.8) | |

| Polyp : | Nb (% Adenoma) | 379 (55.9) | 2979 (51.3) | 2184 (50.5) | 569 (51.1) | 0.27 | 12 (25.0) | 6123 (51.2) |

| CRC : | Nb (% CRC-K) | 54 (66.7) | 301 (69.8) | 170 (72.4) | 47 (63.8) | 0.66 | 13 (38.5) | 585 (69.1) |

| Nb CRC-K | 36 | 210 | 123 | 30 | 0.40 | 5 | 404 | |

| % CRC Level-0 | 13.9 | 25.7 | 27.6 | 43.3 | 0 | 26.2 | ||

| % CRC Level-1 | 30.6 | 30.5 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 20.0 | 31.4 | ||

| % CRC Level-2 | 19.4 | 18.1 | 15.5 | 6.7 | 40.0 | 16.8 | ||

| % CRC Level-3 | 27.8 | 21.9 | 19.5 | 10.0 | 20.0 | 20.8 | ||

| % CRC Level-4 | 8.3 | 3.8 | 4.1 | 6.7 | 20.0 | 4.7 | ||

*CHI-2 de Pearson ; CRC : Colorectal Cancer ; CRC-K : CRC with specified TNM stage ; CRC severity level (Level-0 : CCR (T0) without lymph node involvement (N0/M0) ; Level-1 : CCR (T1/T2) without lymph node involvement (N0/M0) ; Level-2 : CCR (T3/T4) without lymph node involvement (N0/M0) ; Level-3 : CRC (T1-T4) with nodal involvement ; Level-4 : CRC with metastasis (M1)) ; Nb : Number ; YC : Yield of neoplasms at colonoscopy.

The proportion of CRC level-4 (4.8 % in 2017 (653 CRC) ; 7.6 % in 2018 (674 CRC) ; 4.6 % in 2019 (330 CRC) and 4.7 % in 2020 (404 CRC) ; p<0.29) was not significantly different between campaigns. Over the four years of study, the proportion of metastatic CRC ( ≤ 1Month : 10.3 % among 203 CRC ; ]1-3M] : 5.0 % among 1122 CRC ; ]3-7M] : 5.0 % among 539 CRC ; > 7M : 4.4 % among 160 CRC ; p<0.001) was significantly higher among CRCs diagnosed during colonoscopies performed within one month. The distribution of cancers by level and according to the time to colonoscopy for all years combined is detailed in Table-4 .

Table 4.

CRC severity according to year of completion of the positive screening FIT and the time to colonoscopy by year of the positive FIT.

| CRC severity level (TNM) | Year of completion of the positive screening FIT | Time (in month) to colonoscopy | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | p | ≤ 1Month | ]1-3M] | ]3-7M] | > 7M | p | |

| 0.29 | <10-3 | |||||||||

| CIS | 182(27.9) | 173(25.7) | 82(24.8) | 106(26.2) | 35(17.3) | 300(26.7) | 152(28.2) | 55(34.4) | ||

| T1 to T2, N0, M0 | 188(28.8) | 216(32.0) | 118(35.8) | 127(31.4) | 52(25.6) | 362(32.3) | 177(32.8) | 50(31.2) | ||

| T3 to T4, N0, M0 | 119(18.2) | 107(15.9) | 59(17.9) | 68(16.8) | 39(19.2) | 198(17.6) | 83(15.4) | 25(15.6) | ||

| T1 to T4, N1 to N2 | 133(20.4) | 127(18.8) | 56(17.0) | 84(20.8) | 56(27.6) | 206(18.4) | 100(18.6) | 23(14.4) | ||

| M1 | 31(4.7) | 51(7.6) | 15(4.5) | 19(4.7) | 21(10.3) | 56(5.0) | 27(5.0) | 7(4.4) | ||

| Total | 653(100.0) | 674(100.0) | 330(100.0) | 404(100.0) | 203(100.0) | 1122(100.0) | 539(100.0) | 160(100.0) | ||

CRC : Colorectal cancer : CRC stage of severity : described by the tumor, node, and metastasis (TNM) classification based on tumor size (T), lymph node (N) involvement and the possible presence of metastases (M) : CIS : Carcinoma In Situ ; T1 : tumor invading the submucosa ; T2 : Tumor invading the muscularis ; T3 : Tumor invading the subserosa, perirectal/pericolic tissues ; T4 : Tumor invading the serosa, peritoneum and surrounding organs ; N0 : No lymph node metastasis ; N1 : 1 to 3 regional lymph nodes invaded ; N2 : > 3 regional lymph nodes invaded ; M0 : No distant metastasis ; M1 : Distant metastasis (including supraclavicular lymph node) ; FIT : Fecal Immunochemical test.

Analysis of CRC severity in uni/multivariate regression model was made on a baseline of 2024 cancers because out of a total of 2061 CRCs (75.8 % of the total CRCs diagnosed) of which the TNM status was collected, time to colonoscopy was missing for 36 CRC cases (12 in 2017 ; 16 in 2018 ; 4 in 2019 and 5 in 2020). The probability of having a CRC with a high severity level was inversely related to time to colonoscopy but not to the campaign year. Compared to patients having undergone colonoscopy within 30 days, the odds were significantly reduced by 60 % in patients who completed the colonoscopy after 7 months (Adjusted Odds-Ratio (ORa) : 0.4[0.3 ; 0 .6] ; p<0.0001). The odds were reduced by 20 % in patients having completed at least one FIT before the positive FIT compared to patients who had no previous FIT (0.8 [0.7 ; 1.0] ; p=0.02). Compared to patients aged 50-54, the odds were increased by 50 % in patients aged ≥ 70 (Table-5 ).

Table 5.

Uni and multivariate analysis of the relationship between the time to colonoscopy and the severity of the detected CRC lesions.

| Covariables | Severity risk analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate (n=1973 CRC) | |||

| ORb[CI95 %] | P > |z| | ORa[CI95 %] | P > |z| | |

| Time (in month) to colonoscopy (Ref. : ≤ 1Mois) | ||||

| ]1-3Month] | 0.5 [0.4 ; 0.7] | <10-3 | 0.5 [0.4 ; 0.7] | <10-3 |

| ]3-7Mnth] | 0.5 [0.4 ; 0.7] | <10-3 | 0.5 [0.4 ; 0.7] | <10-3 |

| > 7Month | 0.4 [0.3 ; 0.5] | <10-3 | 0.4 [0.3 ; 0.6] | <10-3 |

| Gender (Ref. : Female) | ||||

| Male | 0.9 [0.8 ; 1.1] | 0.24 | 0.9 [0.8 ; 1.1] | 0.38 |

| Age (Ref. : 50-54y) | ||||

| 55 – 59y | 1.1 [0.8 ; 1.5] | 0.43 | 1.1 [0.8 ; 1.5] | 0.46 |

| 60 – 64y | 1.1 [0.8 ; 1.4] | 0.56 | 1.2 [0.9 ; 1.5] | 0.30 |

| 65 – 69y | 1.1 [0.9 ; 1.5] | 0.31 | 1.1 [0.9 ; 1.6] | 0.13 |

| ≥ 70y | 1.3 [1.0 ; 1.7] | 0.02 | 1.5 [1.0 ; 1.9] | 0.007 |

| Nb of previoous FIT (Ref. : None) | ||||

| 1 | 0.9 [0.7 ; 1.1] | 0.33 | 0.9 [0.7 ; 1.1] | 0.30 |

| ≥ 2 | 0.8 [0.7 ; 1.0] | 0.06 | 0.8 [0.7 ; 1.0] | 0.02 |

| Health Insurance Schemes (Ref. General Schemes) | ||||

| MGEN/MFP | 1.0 [0.7 ; 1.3] | 0.79 | 1.0 [0.7 ; 1.3] | 0.88 |

| RATP/SNCF | 0.6 [0.3 ; 1.2] | 0.13 | 0.5 [0.3 ; 1.2] | 0.12 |

| Other schemes | 0.9 [0.7 ; 1.3] | 0.63 | 1.0 [0.7 ; 1.4] | 0.86 |

| Campaign year (Ref. : 2017) | ||||

| 2018 | 1.1 [0.9 ; 1.3] | 0.54 | 1.1 [0.9 ; 1.3] | 0.58 |

| 2019 | 1.0 [0.8 ; 1.2] | 077 | 1.0 [0.8 ; 1.2] | 0.78 |

| 2020 | 0.9 [0.8 ; 1.2] | 0.65 | 1.0 [0.8 ; 1.2] | 0.71 |

| Estimated multivariate ologit model constants | ||||

| /cut 1 | -1.6 [-1.9 ; 1.2] | |||

| /cut 2 | -0.2 [-0.6 ; 0.1] | |||

| /cut 3 | 0.6 [0.2 ; 0.9] | |||

| /cut 4 | 2.3 [1.9 ; 2.7] | |||

CI95 % : 95 % Confident interval ; CRC severity level (Level-0 : CCR (T0) without lymph node involvement (N0/M0) ; Level-1 : CCR (T1/T2) without lymph node involvement (N0/M0) ; Level-2 : CCR (T3/T4) without lymph node involvement (N0/M0) ; Level-3 : CRC (T1-T4) with nodal involvement ; Level-4 : CRC with metastasis (M1)) ; ORb : Odds-Ration brut ; ORa : Odds-Ration ajusté ; MGEN : Mutuelle Générale de l'Education Nationale ; MFP : Mutuelle de la Fonction Publique ; RATP : Régie Autonome des Transports Parisiens ; SNCF : Société Nationale des Chemins de Fer.

4. Discussion

Given the results of this study, the hypothesis that the quality and monitoring indicators of the screening program were worse in IDF in 2020 compared to previous campaigns is not obvious. The average time to colonoscopy certainly increased by a few days in 2020, but this study reminds us that it has never been less than 3.3 months in IDF, regardless of the campaign year. The study shows that the CRCs detected in 2020 were no more advanced than those of previous years. The study also shows that the CRCs detected after 7 months of waiting for a colonoscopy were less advanced than those detected during a colonoscopy carried out in the month following the positive test result. While the number of FITs completed was not affected in 2020, the proportion of tests not analysed reached an all-time high in April 2020 due to the deterioration of postal services induced by the first lockdown in France. The colonoscopy completion rate was certainly lower in 2020, but the proportion of colonoscopies performed within one month was lower in 2019, at which time there was no health crisis.

In France, the impact of the pandemic on CRCSP campaigns defies current literature data. The significant decrease in activity documented elsewhere [23,24] was not observed in IDF, where the interruption of activity observed between March and May 2020 was largely compensated in the second half, making the 2020 campaign paradoxically more successful than the 2019 campaign. It should be remembered, however, that 2019 was marked by an interruption in the supply of test kits, which occasioned a drastic drop in the number of tests carried out and the deterioration of certain program evaluation indicators [25]. Similarly, the negative impact on the severity of CRC lesions of long time to colonoscopy observed in the literature [14,26,27] was unexpectedly not observed in this study. As of now, it is recommended that the impact of colonoscopy demand on waiting times for symptomatic patients be assessed to ensure sufficient new planned capacity ; the objective being to avoid excessively long waiting times for these patients [13]. The hypothesis of an appointment being shortened by the gastroenterologist himself (or at the request of the patient's doctor), after a few signs were noted during the first consultation, could be raised to explain this paradoxical link between waiting time to colonoscopy and severity of the screened CRCs.

Several other indicators were degraded before the first wave of the COVID-19 crisis. Colonoscopy completion rate in IDF has remained very stable and is much lower than the 97.1 % observed in Rhône-Alpes [28]. The difference of six points the colonoscopy completion rate between 2018 and 2020 could be linked to a deterioration of the means of collecting information induced by the health crisis. In the United States [29], medical databases are updated in real time because they are mostly electronic and shared by several care actors. In France, transmission of colonoscopy data has yet to be dematerialized, as each gastroenterologist decides (or not) to send to the CRCDC a paper colonoscopy report drawn up after a positive screening test. Sometimes the report to the CRCDC is transmitted by the patient himself, most often at the request of the CRCDC. From March 2020, the lockdown and other restrictive measures lengthened the delay in transmission of colonoscopy reports in a region where the colonoscopy completion rate had never reached 85 % since 2015. Long delays in colonoscopy, exceeding 12 months, are rare in France. The low colonoscopy completion rate observed in 2020 was corrected by additional colonoscopies, of which the reports arrived late, most often for colonoscopies performed outside the region. While this catch-up in the collection of colonoscopy data may have affected the colonoscopy performance rate, it did not necessarily affect colonoscopy completion time, let alone the conclusions of this study.

In addition to continuous deterioration, the colonoscopy completion rate and time to colonoscopy recorded a disparity between the strata defined on several explanatory variables. This suggests that the deterioration of the indicators is better explained by patient characteristics than by the colonoscopy offer. The impact of cultural diversity has been mentioned [18], and a link between gender, racial/ethnic group, and the completion of colonoscopy within 60 days has been established in the USA [30]. The strong mobilization of people affiliated to special health insurance schemes has been proven [31]. The patient's socioeconomic level and type of health insurance are factors influencing the physician's decision to recommend screening or not [32]. The link between age and participation in screening campaigns has been demonstrated in some studies [19,31]. In this study, while the differences were certainly reduced, patients with no previous participation in CRCSP and those affiliated to the general scheme had a low rate of colonoscopy completion. Despite being at higher risk of CRC, people over the age of 70 were no different from the others in terms of rate and time to perform colonoscopy, particularly in 2019 and 2020.

The completion rate and time to colonoscopy were not related to density of gastroenterologists in the municipality of residence of the patients. This study shows that in addition to being less in demand for screening colonoscopies, the public hospital service already had a very long waiting time to colonoscopy before the health crisis. To explain this long delay in the use of the public service in France, other studies are necessary because the consequences of a possible reorganization of the care services on the screening programs as analysed elsewhere [33], were apparent in France before the pandemic.

The main limitation of this study is related to the fact that the multivariate analysis of the relationship between CRC severity and time to colonoscopy was not exhaustive regarding all the explanatory variables described in the literature, particularly the social deprivation index. In Ile-de-France, the negative impact of this index was shown with regard to another screening program [34]. However, this limitation does not affect the quality of the regression analysis insofar as the univariate relationship proved between severity and time to colonoscopy was not affected by the multivariate analysis.

5. Conclusions

In France, most of the assessed indicators were already degraded before the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. The impact of the pandemic on the CRCSP defies current data from the literature. The time to colonoscopy and ths extension induced by the health crisis had no impact in terms of CRC severity, probably due to a discriminatory approach prioritizing patients with existing symptoms.

The decrease in activity documented elsewhere could not be observed in IDF because the cessation of activity between March and May 2020 was largely compensated in the following months, making the 2020 campaign more successful than the 2019 campaign. In addition to continuous deterioration, time to colonoscopy recorded a disparity between strata defined on several explanatory variables. This suggests that the deterioration of the indicators is better explained by patient characteristics than by the colonoscopy offer.

Author contributions

AK, GA, TLT, HAH, AB, HD and CV are the doctors in charge of coordinating the screening program in each IDF department. JN is the medical director of the CRCDC-IDF. All doctors in charge of coordinating the screening program collected the field data. AK analysed the data, interpreted the results, and drafted the manuscript. All the authors revised the manuscript, read, and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

No conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

The study did not receive any special funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff of the CRCDC-IDF, particularly Aude TRIEUL, who updated the DOCCR database daily. The authors would also like to thank Stéphanie RASSE (National Council of the Order of Physicians, Research and Statistics Study Department) who facilitated access to medical demographic data. The authors are grateful to all contributors who participated in the final revisions.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mazidimoradi A, Tiznobaik A, Salehiniya H. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Colorectal Cancer Screening: a Systematic Review. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2022;53(3):730–744. doi: 10.1007/s12029-021-00679-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kortlever TL, de Jonge L, Wisse PHA, Seriese I, Otto-Terlouw P, van Leerdam ME, et al. The national FIT-based colorectal cancer screening program in the Netherlands during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev Med. 2021;151 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhandari P, Subramaniam S, Bourke MJ, Alkandari A, Chiu PWY, Brown JF, et al. Recovery of endoscopy services in the era of COVID-19: recommendations from an international Delphi consensus. Gut. 2020;69(11):1915–1924. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gralnek IM, Hassan C, Beilenhoff U, Antonelli G, Ebigbo A, Pellise M, et al. ESGE and ESGENA Position Statement on gastrointestinal endoscopy and the COVID-19 pandemic. Endoscopy. 2020;52(6):483–490. doi: 10.1055/a-1155-6229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parodi SM, Liu VX. From Containment to Mitigation of COVID-19 in the US. JAMA. 2020;323(15):1441–1442. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Repici A, Aragona G, Cengia G, Cantu P, Spadaccini M, Maselli R, et al. Low risk of COVID-19 transmission in GI endoscopy. Gut. 2020;69(11):1925–1927. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tian Y, Rong L, Nian W, He Y. Review article: gastrointestinal features in COVID-19 and the possibility of faecal transmission. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51(9):843–851. doi: 10.1111/apt.15731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson NM, Norton A, Young FP, Collins DW. Airborne transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 to healthcare workers: a narrative review. Anaesthesia. 2020;75(8):1086–1095. doi: 10.1111/anae.15093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.SFED Epidémie de COVID-19 – Recommandations en endoscopie digestive 11 mars 2020. Société Française d'Endoscopie Digestive(SFED) 2020 https://www.sfed.org/sites/www.sfed.org/files/2021-10/covid19endo_reco.pdf Accessible à l'adresse. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belle A, Barret M, Bernardini D, Tarrerias AL, Bories E, Costil V, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on gastrointestinal endoscopy activity in France. Endoscopy. 2020;52(12):1111–1115. doi: 10.1055/a-1201-9618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ponchon T, Chaussade S. COVID-19: How to select patients for endoscopy and how to reschedule the procedures? Endosc Int Open. 2020;8(5):E699–E700. doi: 10.1055/a-1154-8768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valori R, Rey JF, Atkin WS, Bretthauer M, Senore C, Hoff G, et al. European guidelines for quality assurance in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis. First Edition–Quality assurance in endoscopy in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis. Endoscopy. 2012;44(Suppl 3):SE88–S105. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1309795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corley DA, Jensen CD, Quinn VP, Doubeni CA, Zauber AG, Lee JK, et al. Association Between Time to Colonoscopy After a Positive Fecal Test Result and Risk of Colorectal Cancer and Cancer Stage at Diagnosis. JAMA. 2017;317(16):1631–1641. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.3634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrat E, Le Breton J, Veerabudun K, Bercier S, Brixi Z, Khoshnood B, et al. Colorectal cancer screening: factors associated with colonoscopy after a positive faecal occult blood test. Br J Cancer. 2013;109(6):1437–1444. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaufmanis A, Vincelet C, Koivogui A, Ait Hadad H, Bercier S, Brixi Z, et al. Dépistage organisé du cancer colorectal en Ile-de-France: état des lieux du délai de réalisation de la coloscopie avant et après l'introduction du test immunologique. In: (SNFGE) SNFdG-E, editor. Journées Francophones d'Hépato-Gastroentérolgie et d'Oncologie Digestive (JFHOD); 2018 MARCH 22-25; Paris. Paris, France2018. p. P.418.

- 17.Bayardin V, Mosny E, Moreau E, Roger S. Une hausse de 20 % des décès en Île-de-France en 2020. Insee Analyses Île-de-France. 2021;132. Available at: https: //www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/5350486,accessed 10 April 2023.

- 18.Koivogui A, Ecochard R, Le Mab G, Benamouzig R. Impact of stopping sending colorectal cancer screening tests kits by regular mail. Public Health. 2019;12(7):10–12. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2019.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leuraud K, Jezewski-Serra D, Viguier J, Salines E. Colorectal cancer screening by guaiac faecal occult blood test in France: Evaluation of the programme two years after launching. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013;37(6):959–967. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World-Health-Organization. 10th International Classification of Diseases, Version: 2008. Geneve: World Health Organization, 1990. Available from: https://icd.who.int/browse10/2008/fr. 1990.

- 21.Amin MB, Edge S, Greene F, Byrd DR, Brookland RK, Washington MK, et al. 8th ed. Springer; New York: 2017. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Délibération n° 2017-215 du 13 juillet 2017 portant adoption d'une norme destinée à simplifier l'obligation de déclaration des traitements de données à caractère personnel ayant pour finalité le dépistage organisé du cancer du sein, du cancer colorectal et du cancer du col de l'utérus mis en œuvre par les structures de gestion conventionnées, et abrogeant la délibération n° 2015-175 du 11 juin 2015 (décision d'autorisation unique n° AU-043) (NS-059) NOR: CNIL1724568X (2017).

- 23.Battisti F, Falini P, Gorini G, Sassoli de Bianchi P, Armaroli P, Giubilato P, et al. Cancer screening programmes in Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic: an update of a nationwide survey on activity volumes and delayed diagnoses. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2022;58(1):16–24. doi: 10.4415/ANN_22_01_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dennis LK, Hsu CH, Arrington AK. Reduction in Standard Cancer Screening in 2020 throughout the U.S. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13(23) doi: 10.3390/cancers13235918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koivogui A, Vincelet C, Abihsera G, Ait-Hadad H, Delattre H, Le Trung T, et al. Supply and quality of colonoscopy according to the characteristics of gastroenterologists in the French population-based colorectal-cancer screening program. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29(9):1492–1508. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v29.i9.1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beshara A, Ahoroni M, Comanester D, Vilkin A, Boltin D, Dotan I, et al. Association between time to colonoscopy after a positive guaiac fecal test result and risk of colorectal cancer and advanced stage disease at diagnosis. Int J Cancer. 2019 doi: 10.1002/ijc.32497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee YC, Fann JC, Chiang TH, Chuang SL, Chen SL, Chiu HM, et al. Time to Colonoscopy and Risk of Colorectal Cancer in Patients With Positive Results From Fecal Immunochemical Tests. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(7) doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.10.041. 1332-40 e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balamou C, Koivogui A, Rodrigue CM, Clerc A, Piccotti C, Deloraine A, et al. Prediction of the severity of colorectal lesion by fecal hemoglobin concentration observed during previous test in the French screening program. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27(31):5272–5287. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i31.5272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verma M, Sarfaty M, Brooks D, Wender RC. Population-based programs for increasing colorectal cancer screening in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(6):497–510. doi: 10.3322/caac.21295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oluloro A, Petrik AF, Turner A, Kapka T, Rivelli J, Carney PA, et al. Timeliness of Colonoscopy After Abnormal Fecal Test Results in a Safety Net Practice. J Community Health. 2016;41(4):864–870. doi: 10.1007/s10900-016-0165-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pornet C, Denis B, Perrin P, Gendre I, Launoy G. Predictors of adherence to repeat fecal occult blood test in a population-based colorectal cancer screening program. Br J Cancer. 2014;111(11):2152–2155. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pollack CE, Mallya G, Polsky D. The impact of consumer-directed health plans and patient socioeconomic status on physician recommendations for colorectal cancer screening. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(10):1595–1601. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0714-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kopel J, Ristic B, Brower GL, Goyal H. Global Impact of COVID-19 on Colorectal Cancer Screening: Current Insights and Future Directions. Medicina (Kaunas) 2022;58(1) doi: 10.3390/medicina58010100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Audiger C, Bovagnet T, Deghaye M, Kaufmanis A, Pelisson C, Bochaton A, et al. Factors associated with participation in the organized cervical cancer screening program in the greater Paris area (France): An analysis among more than 200,000 women. Prev Med. 2021;153 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]