Abstract

The global impact of COVID-19 has led to the development of numerous mathematical models to understand and control the pandemic. However, these models have not fully captured how the disease’s dynamics are influenced by both within-host and between-host factors. To address this, a new mathematical model is proposed that links these dynamics and incorporates immune response. The model is compartmentalized with a fractional derivative in the sense of Caputo–Fabrizio, and its properties are studied to show a unique solution. Parameter estimation is carried out by fitting real-life data, and sensitivity analysis is conducted using various methods. The model is then numerically implemented to demonstrate how the dynamics within infected hosts drive human-to-human transmission, and various intervention strategies are compared based on the percentage of averted deaths. The simulations suggest that a combination of medication to boost the immune system, prevent infected cells from producing the virus, and adherence to COVID-19 protocols is necessary to control the spread of the virus since no single intervention strategy is sufficient.

MSC: 92B05, 92C37, 92D30, 34A08

Keywords: COVID-19, Fractional derivatives, Fixed point, Sensitivity analysis, Multi-scale

1. Introduction

The Coronavirus disease, globally called COVID-19, started in Wuhan, China and has affected millions of people across the globe [1]. The virus that causes COVID-19 is SARS-CoV-2, belonging to the family Coronaviridae and in the Nidovirals order [2]. The most common symptoms of COVID-19 include fever, cough, and other flu-like symptoms such as fatigue, chills, and sore throat. Critically ill patients can develop severe pneumonia, sometimes acute respiratory distress, which can lead to multiple organ failure and death. [3]. Some of the factors that complicate COVID-19 control are the individual’s immune response to SARS-CoV-2 and long period of incubation [4]. For more details as regards the diagnosis, symptoms, fatality rate etc. of SARS-CoV-2, see [3], [5], [6], [7], [8].

Our focus here is to use a mathematical model to better understand the dynamics and control COVID-19. Several mathematical models have been proposed to study the epidemiology of COVID-19. For instance, see [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17].

Monda & Khajanchi [18] developed a compartmental model of COVID-19 in India and showed that disease transmission rate has an impact on controlling the spread of the disease. Zenebe et al. [19] proposed and validated a mathematical model for the transmission dynamics of COVID-19, using the COVID-19 infected data reported from March 13, 2020 to July 31, 2021, in Ethiopia. Their results showed that the spread of COVID-19 can be controlled by minimizing contact rate of infected people and increasing quarantine of exposed individuals. The results and conclusions of the articles [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19] seem interesting however only the epidemiology of the virus was considered while the immunology aspect was neglected.

The dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 in human host has been mathematically studied by few authors. For instance in [20], the authors studied an in-host model that gave the influence of effector T-cell to the behaviour of SARS-CoV-2 within human host. Their results suggested that SARS-CoV-2 may replicate fast enough to overcome T cells response and cause infection. Mathematical analysis of the model in [21] was analyzed in [22]. It was biologically gathered that for the basic reproduction number to be less than unity, infection needs to be cleared from a human body. Recently, the authors in [23] proposed a within-host mathematical model of SARS-CoV-2 dynamics incorporating innate and adaptive immune responses. In their results, it was suggested that blocking the infected cells from producing the virus can be an effective control measure.

Animal models are often used for experimental trials, while developing antiviral drugs. Thus in [24], mathematical models and experimental data were used to characterize the in-host SARS-CoV-2 dynamics in ferrets (animal hosts). It was reported, by analysis and simulations, that ferrets can be an appropriate animal model for SARS-CoV-2 dynamics in human hosts. Immune response has a significant impact on the dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 within a human host however, the data fitting in [24] did not support the need to include immune response in the model. This is a significant gap. A within-host and aerosol mathematical model was proposed in [25] and used to determine the relationship between viral kinetics in the aerosols as well as the upper respiratory track, and new transmissions in golden hamsters challenged with SARS-CoV-2. The authors reported sex-based differences in the dynamics of the virus - the within-host basic reproductive number is less than one in all female hamsters while basic reproductive number is above one in all male hamsters.

In this article, we propose a model which links the dynamics of the disease within a host with the dynamics of the disease between hosts. This kind of model is known as multiscale model and has been extensively used to study the transmission dynamics of infectious diseases [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31]. However, the use of multiscale model to study the dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 is very rare in literature. The advantage of multiscale approach is that it gives more comprehensive insights to the understanding the spread of a disease at different scales [26].

Bellomo et al. [32] proposed a multiscale modeling of COVID-19 pandemic and presented further development of the model developed by [33]. They incorporated the dynamics of mutations into new variants and showed that the onset of a new variant that is more aggressive than the primary virus, generates a progressive prevalence of the variant over the firstly appeared virus. Wang et al. [34] developed a multiscale model to study the coupled within-host and between-host dynamics of COVID-19. Explicit analysis was carried out, in terms of local and global dynamics of fast, slow and full systems, which includes both forward and backward bifurcations. It was concluded that viral treatment can delay, but not prevent, the onset of disease. Between host and within host dynamics of pathogen evolution with application to SARS-CoV-2 was presented in [35]. The within-host dynamics was modelled using random walk while an SIR model was used for inter-host dynamics. This allowed for consideration of multiple hosts. However, the random walk model is not suitable for modeling interventions like vaccination or social distancing. Therefore, the article did not discuss intervention strategies or the impact of memory processes. Additionally, the epidemiological dynamics of COVID-19 are more complex than the SIR model used in the article.

We contribute to the existing body of works by proposing and studying a fractional mathematical model which links the between-host and within-host models to investigate the dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 replication inside a human host and COVID-19 spread outside a human host. The main reasons for using a differential operator with fractional order are that many systems (including disease dynamics) are influenced by memory, history, or non-local effects, which can be difficult to model with integer order derivatives [36]. The fractional differential operator for the constructed model is taken in the Caputo–Fabrizio sense because it is non-local, non-singular and has a fading memory [37]. A fractional differential operator with fading memory is used with the hypothesis that the dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 depends on the recent past occurrences but not on the distant past.

Many studies have reported that immune response is important in modeling virus infections, see [20], [38], [39] and the references therein. T-cells (helper T-cells and cytotoxic T-cells in particular) play a significant role in the fight against pathogens and the risk of developing autoimmunity or overwhelming inflammation [39]. In within-host dynamics, helper T-cells activate other cells (such as B cells) to secrete antibodies that kill the invading virus while cytotoxic T-cells can kill virally infected cells [22], [39], [40], [41]. Helper and cytotoxic T-cells are parts of adaptive immune response. Innate immunity also helps to attack foreign bodies in human body. While adaptive immunity is specific in its actions, innate immunity is general and non-specific, it is also the first line of defence against pathogens [42], [43]. Innate and adaptive immune responses are therefore incorporated into our model and their impacts on the dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 are investigated. These were not considered in [32], [33], [34], [35]. We include in our model, the populations of natural killer cells, B-cells and cytotoxic T-cells with the assumption that the transmission rate is a function of the viral load. Qualitative properties of our model is given after which some parameters of the model are estimated by fitting the model to real-life data. Simulations are then carried out to investigate the influence of each parameter on the dynamics of the disease and various intervention strategies are suggested.

The rest of this article is organized as follows: A deterministic model is formulated and analyzed in Section 2. It was shown in Section 3 that the model has a unique solution while the disease free stationary solution of the model is analyzed in Section 3. Parameter estimation, sensitivity analysis and other simulations are done in Section 5. The work is concluded in Section 6.

2. Model description and formulation

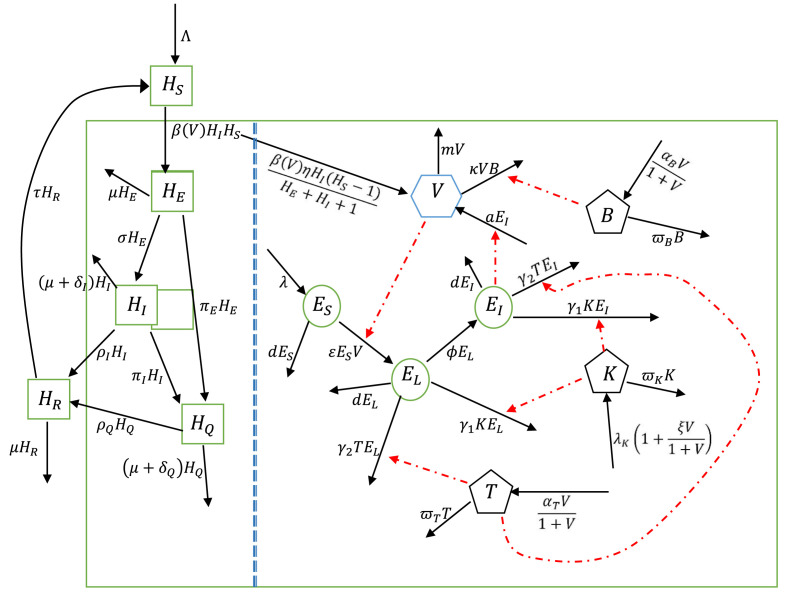

The between-host subsystem is divided into five compartments: Susceptible human , Exposed human , Infectious human (asymptomatic and symptomatic), Quarantined human and Recovered human .

The following assumptions were made:

- (i)

There is no vertical transmission of the virus;

- (ii)

The transmission of the virus is only by coming in contact with an infectious individual;

- (iii)

There is no immigration of infectious individuals;

- (iv)

The dynamics of the disease is independent of weather;

- (v)

Humans die naturally at a rate .

A new recruit enters the susceptible human population at a rate . It was reported in [44] that the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is directly connected to the viral load in infectious individuals. It is therefore assumed that transmission of the virus depends on the average viral load per infected individual. Susceptible human comes in contact with an infectious human who sheds virus and becomes infected at a rate .

| (2.1) |

where , , . An exposed individual becomes infectious at a progression rate , becomes detected and quarantined at a rate .

| (2.2) |

An infectious individual die due to infection at a rate , detected and quarantined at a rate , and recover at a rate .

| (2.3) |

Quarantined human die as a result of COVID-19 at a rate and recovered individuals lose their immunity and become susceptible after a period of .

| (2.4) |

| (2.5) |

Following [22], [23], [45], [46], the within host subsystem consists of susceptible epithelial cell population (), latently infected epithelial cells (), infectious epithelial cells (), SARS-CoV-2 virus in the biological environment (), natural killer cells (), B cells () and cytotoxic T-cells ().

Viral load within an infected individual is generated following intake of SARS-CoV-2 through transmission from an infectious individual. When transmission takes place, the population of susceptible individuals decreases by 1 while the population of infected individuals increases by one. Thus following [26], we assume that when a susceptible human contract SARS-CoV-2 virus, there is a transition given by

Therefore, the average rate of intake of SARS-CoV-2 virus by a single susceptible human host is modelled by

leading to one infected human host. This means that the average viral load in an infected human increases at a rate where represents the average viral load intake by a susceptible individual who comes in contact with an infectious individual.

Helper T-cells promote the production of virus-specific antibodies by activating T-dependent B-cells [43], [47]. Let represent the local interaction dynamics of the virus with B cells . Due to this interaction, virus particles are reduced at the rates . Also, infectious epithelial cells produce virus into the biological environment at a rate . We thus have

| (2.6) |

Susceptible epithelial cells () become latently infected () by free virus in the biological environment at a rate . represents death rate while is the regeneration rate of susceptible epithelial cells.

| (2.7) |

Latently infected epithelial cells () become infectious after days and also die naturally at a rate . When a cell becomes infected with the virus, it becomes a target for natural killer cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes which attack and kill the infected cells [22], [39], [40], [41], [43], [47]. Let the and be the rates at which natural killer cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes, respectively, interact and kill infected epithelial cells. Then we have

| (2.8) |

| (2.9) |

For the dynamics of natural killer cells, B-cells and cytotoxic T-cells, we have the following equations,

| (2.10) |

| (2.11) |

| (2.12) |

represents the natural recruitment rate of natural killer cells while represent the natural clearance rates of natural killer cells, B-cells and cytotoxic T-cells respectively. It is assumed that the recruitment rate of natural killer cells increases with the inversion of the virus. B-cells and cytotoxic T-cells are adaptive immune responses and only respond when there is a foreign inversion by virus [40], [42], [43]. Therefore their recruitment depends on viral inversion. We denote by and the maximum proliferations in response to the presence of virus particles. Fig. 2.1 describes the model diagrammatically. Putting (2.1)–(2.12) together, we have the multiscale model below (see Table 1)

Fig. 2.1.

Flow diagram of the mathematical model linking within-host and between-host dynamics of SARS-CoV-2.

Table 1.

Description of state variables of between-host and within-host COVID-19 model.

| Variables | Description |

|---|---|

| Susceptible human | |

| Exposed human | |

| Infectious human | |

| Quarantined human | |

| Recovered human | |

| Average viral load within a single infected human | |

| Susceptible epithelial cells | |

| Latently infected epithelial cells | |

| Infectious epithelial cells | |

| Killer T-cells | |

| B-cells | |

| Cytotoxic T-cells |

| (2.13) |

| (2.14) |

| (2.15) |

| (2.16) |

| (2.17) |

| (2.18) |

| (2.19) |

| (2.20) |

| (2.21) |

| (2.22) |

| (2.23) |

| (2.24) |

Model (2.13)–(2.24) has the following initial conditions:

, , , , , , , , , , , .

All parameters are non-negative for all and are as defined in Table 2 while the fractional derivative is understood to be in Caputo–Fabrizio (CF) sense. We have the following definition (cf [37]):

Table 2.

Summary of the parameters.

| Parameter | Meaning | Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recruitment rate for human population | individual day−1 | ||

| Effective transmission rate per infectious individual per time | individual−1 day−1 | Data fitting | |

| Loss of immunity rate | day−1 | [48] | |

| Progression rate at which exposed individuals become infectious | day−1 | [19], [49], [50] | |

| Quarantine rate of | 0.761 day−1 | Data fitting | |

| Quarantine rate of | 0.90 day−1 | Data fitting | |

| Disease-induced death rate for undetected infectious individuals | 0.015 day−1 | [51] | |

| Disease-induced death rate for quarantined individuals | day−1 | Data fitting | |

| Recovery rate of | day−1 | [52], [53] | |

| Recovery rate of | 0.101 day−1 | Estimated [54] | |

| Natural death rate of human | (43.5 year)−1 | [55] | |

| Average viral load intake by a susceptible individual who comes in contact with an infectious individual | 2.15 copies ml−1 | Data fitting | |

| Production rate of SARS-CoV-2 | 12 copies ml−1 cell−1 day−1 | [34] | |

| Killing rate of the virus by B-cell per time | cell−1 day−1 | [23] | |

| Recruitment rate of | cells day−1 | [56] | |

| Rate at which are infected by SARS-CoV-2 | ml copy−1 day−1 | Data fitting | |

| Natural death rate of epithelia cells | day−1 | [57] | |

| Killing rate of infected epithelia cells by natural killer cell | cell−1 day−1 | [58] | |

| Killing rate of infected epithelia cells by cytotoxic T-cell | cell−1 day−1 | Data fitting | |

| Transition rate from to | 0.60 day−1 | Data fitting | |

| Activation rate of cytotoxic T-cells | cells day−1 | Assumed | |

| Activation rate of B-cells | cells day−1 | Assumed | |

| Constant regeneration rate of natural killer cells | cells day−1 | [59] | |

| Natural death rate for natural killer cells | day−1 | [60] | |

| Natural death rate for B-cells | Assumed | ||

| Natural death rate for cytotoxic T-cells | 0.1 day−1 | [57] | |

| Half saturation constant for viral shedding | 0.759 copy ml−1 | Estimated [61] | |

| Natural viral clearance rate from biological environment | 0.699 day−1 | Data fitting | |

| Influence of viral load on regeneration rate of natural killer cells | 0.688 | Data fitting | |

| Influence of viral load on transmission | 0.598 | Data fitting |

Definition 2.1

For a given function , the Caputo–Fabrizio (CF) fractional derivative is defined as

(2.25) where is a normalization functions satisfying .

Without losing generality, we take , where represents the fractional order index. The fractional integral corresponding to (2.25) is defined in [62] as

| (2.26) |

The dimension of the right side of model (2.13)–(2.24) is day−1 while the fractional operator on the left has dimension day. To address this problem of dimensional mismatch, we use the approach in [63], in which case the normalization parameter is taken as 1.

3. Existence and uniqueness of solutions to the model

In this section, we show that model (2.13)–(2.24) with the initial condition has a unique solution. For convenience, we define

Theorem 3.1

satisfies the Lipschitz condition

(3.1) Furthermore, if there exists such that

(3.2) then the fractional initial value problem (2.13) – (2.24) admits a unique solution on the interval .

Proof

Clearly, , , , , , , , , , , , are bounded functions and there exist , such that , , , , , , , , , , , . Where denotes the maximum norm.

Now consider kernel . Let , be any two functions (with other variables as constant), then

Let , be any two functions (with other variables as constant), then

Let , be any two functions (with other variables as constant), then

Finally, let , be any two functions (with other variables as constant), then

Use is made of mean value theorem to obtain the above, where . Taking , we see that satisfies Lipschitz condition with respect to its arguments. By a similar argument, one can obtain Lipschitz constants for , . Thus, there exists a positive constant such that

(3.3) Applying the integral operator (2.26) to both sides of model (2.13)–(2.24), we have

(3.4) Now, we define a recursive formula

(3.5)

(3.6)

By iteration on

(3.7) Existence of solution follows by taking the limit on both sides of (3.7).

Next, we establish the uniqueness of solution. Assume and are different solutions of model (2.13)–(2.24), then

Inequality (3.1) implies

Condition (3.2) implies

Uniqueness of solution follows immediately. □

4. Disease-free equilibrium solution

Here, we find the equilibrium points, obtain the basic reproduction number and give some qualitative results. The disease-fee equilibrium solution of model (2.13)–(2.24) is given as

| (4.1) |

Below, we obtain the basic reproduction number by expressing the disease class of the model as the difference between the new infection vector and transmission vector .

We obtain the Jacobian matrices , of and at the disease-free equilibrium point. Then, we compute (see the equation in Box I)

Box I.

Finding the eigenvalues of the above matrix, we have

where

is the basic reproduction number corresponding to the epidemiological (between host) part of the model while corresponds to the immunological (within host) part.

Consider the following fractional-order linear system with Caputo–Fabrizio derivative:

| (4.2) |

where , , and . The following definition and result will be needed in the sequel:

Definition 4.1 [64, Definition 2] —

The characteristic equation of system (4.2) is

Lemma 4.2 [64, Theorem 1] —

If the matrix is invertible, then (4.2) is asymptotically stable if and only if the real parts of the roots of the characteristic equation of system (4.2) are negative.

We have the following result on stability of the disease-free equilibrium point:

Theorem 4.3

The disease-free equilibriumof(2.13)–Eq. (2.24) is locally asymptotically stable if .

Proof

Lemma 4.2 is used to establish this result. We obtain matrix by linearizing the model (2.13)–(2.24) at the disease-free equilibrium point (see the equation in Box II):

where

Next, we show that is invertible and the roots of have negative real parts. After a few lines of calculation, we have

for . This shows that is invertible. Now, the roots of are

The remaining roots can be obtained from the equation

(4.3) where

Obviously, are negative real numbers, have negative real parts provided . For , Routh–Hurwitz criterion is used to show that (4.3) has roots with negative real parts. By Routh–Hurwitz criterion, (4.3) has roots with negative real parts if and only if , and are positive and [65]. Obviously, , and provided . After a few lines of calculations, we have

The result follows from Lemma 4.2. □

Box II.

5. Simulations and discussions

This section is devoted to simulations of various forms as well as discussions of results. Codes are written in MATLAB® for this purpose. For the choice of , it is assumed that has a base transmission rate and increases as the viral load increases.

Where is the half saturation constant for viral shedding and is the influence of viral load on transmission.

5.1. Parameter estimation

We use the COVID-19 data provided by Malaysian government from 10/01/2022 through 10/03/2022 which is publicly available at [54] for our model fitting. We choose this range because of the high spread of the virus in Malaysia at this period.

For this purpose, we add two new compartments - confirmed cases () and confirmed death cases () to model (2.13)–(2.12).

| (5.1) |

| (5.2) |

The quarantined compartment , death compartment and confirmed cases compartment are fitted to the “active cases”, “cumulative death cases” and “cumulative confirmed cases” data respectively. As Malaysia is roughly a 33,000,000 population country, we therefore set . and are taken from the data while and are estimated.

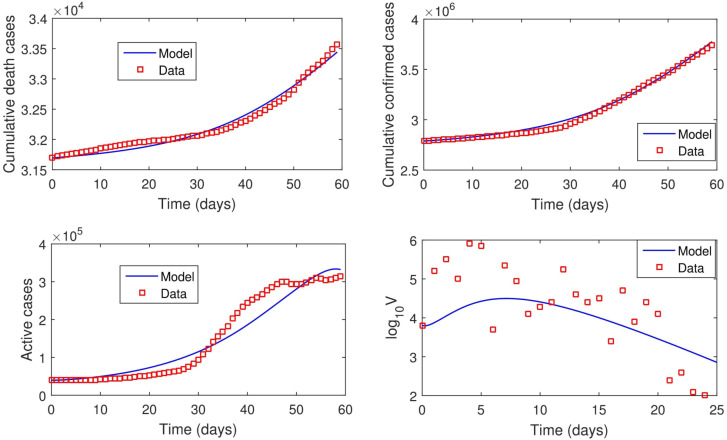

For the immunological part of the model, we fit our model to the mean viral load data of Hong Kong patients [66]. The model fitting for epidemiological and immunological parts are done simultaneously. Our simulation was carried out using “fmincon” package by MATLAB® [67]. The data available in [54], [66] is not sufficient to estimate all the parameters involved in the dynamics of the disease. We therefore rely on the values found in literature for some parameters and assumed values for some. Our estimated parameter values and other parameter values are contained in Table 2. From our model fitting, it was estimated that and while the order of differentiation was estimated as 0.569 (ie ). This therefore means that fractional order differential equations best fit the data than differential equations with classical differentiation. In other words, this study shows that including memory effects in modeling COVID-19 dynamics significantly improves the accuracy of the fit to the data. For subsequent simulations, we take . Fig. 5.1 shows the fitted curves and the real-life data. Using the estimated parameter values, while . This shows that the major driver of the dynamics of the disease (during the period used for parameter estimation) is the dynamics of the virus within host.

Fig. 5.1.

Real-life COVID-19 data and lines of best.

5.2. Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis helps to measure the influence of each parameter in the dynamics of infection being studied [68]. We investigate the influence of each parameter on the dynamics of the disease both locally and globally. While local sensitivity analysis examines the sensitivity of a variable or parameter with respect to change in a single parameter value, global sensitivity analysis examines the sensitivity of a variable or parameter with respect to change within the entire parameter range [69]. Global sensitivity analysis (GSA) seems to provide comprehensive result however, different methods of GSA can give different results and furthermore, the result of analysis greatly depends on the assumed probability distribution of the input parameters [68], [70]. Local sensitivity analysis, on the other hand, considers only the variation in one input parameter at a time, the sensitivity coefficient obtained can be used for comparison with other parameters independent of the range of parameter variations [70]. Considering the advantage of one approach over the other, both approaches are therefore used in this work.

5.2.1. Local sensitivity analysis

In order to determine the most essential parameters in the transmission dynamics of COVID 19, we perform a sensitivity analysis of the formulated model (2.13) –(2.24) according to [71].

Definition 5.1

The normalized forward sensitivity index, of a variable, to a parameter denoted by , is denoted as a ratio of the relative change in the variable to the relative change in the parameter

The magnitudes and signs of the sensitivity indices of the basic reproduction numbers with respect to model parameters obtained and shown in Fig. 5.2 reveal how changes in the model parameters affect the basic reproduction number. The parameters with positive indices suggest that an increase (or decrease) in the value of each of these parameters will lead to the increase (or decrease) in . For example, , implies that increasing (or decreasing) the transmission rate, , by 10% also increases (or decreases) the basic reproduction number, , by 10%, provided other parameters are constant. On the other hand, the parameters with negative indices suggest that an increase (or decrease) in the value of each of these parameters will lead to the decrease (or increase) in .

Fig. 5.2.

Sensitivity indices of to model parameters.

From the sensitivity indices in Fig. 5.2, it can be seen that the basic reproduction number is more sensitive to the parameters corresponding to the in-host dynamics. Fig. 5.2 suggests that immune response plays sensitive role in controlling the spread of the disease. It is worth mentioning that natural human death rate (), natural death rate of epithelial cell (), human recruitment rate (), epithelial cell recruitment rate () have significant influence on , however control measures can not be built around these parameters. For example, the sensitivity indices in Fig. 5.2 suggests that natural human death rate should be increased in other to curtail the spread of the virus. This is not good and therefore not implementable.

Other important parameters worthy of attention are the transmission rate (), progression of exposed individuals to infectious compartment (), quarantine of both exposed and infectious individuals (), rate at which susceptible epithelial cells are infected by SARS-CoV-2 (), progression of latently infected epithelia cells to infectious epithelial cells (), production rate of SARS-CoV-2 by infected epithelial cells (), viral clearance rate from biological environment (). The basic reproduction number is positively sensitive to parameters , , , and but negatively sensitive to , and . Therefore the control measure be such that the values of the parameters with positive indices are reduced while the values of the parameters with negative indices are increased. Our point here is this, the sensitivity indices suggests that in order to curtail the spread of the virus, the following are necessary - use of drugs/medication to boost immune response, observance of COVID-19 protocol to reduce transmission, use of medication that prevents epithelial cells from being infected or prevents (or reduce) infected epithelial cell from producing the virus, use of drugs to hasten the clearance of virus from human body and contact tracing followed by quarantined of infected individuals.

5.2.2. Global sensitivity analysis

In order to further quantify the impact of each parameter on the basic reproduction number (), we adopt a sampling-based method called Latin hypercube sampling with partial rank correlation coefficient index, (LHS-PRCC). The goal of LHS-PRCC is to identify key parameters whose uncertainties contribute to the inaccuracy of prediction and to rank these parameters by their level of influence in contributing to the prediction imprecision. The magnitude and the statistical significance (-value) of the PRCC value of a parameter indicate the contribution of the uncertainty in the parameter to the model’s prediction. The closer the PRCC value to or , the more strongly the parameter influences the outcome measure. The -value is the probability of getting a correlation as large as the observed value by random chance, when the true correlation is zero. The PRCC value is significant if the -value is small, say less than 0.05. For a comprehensive description of this method, we refer to [72], [73].

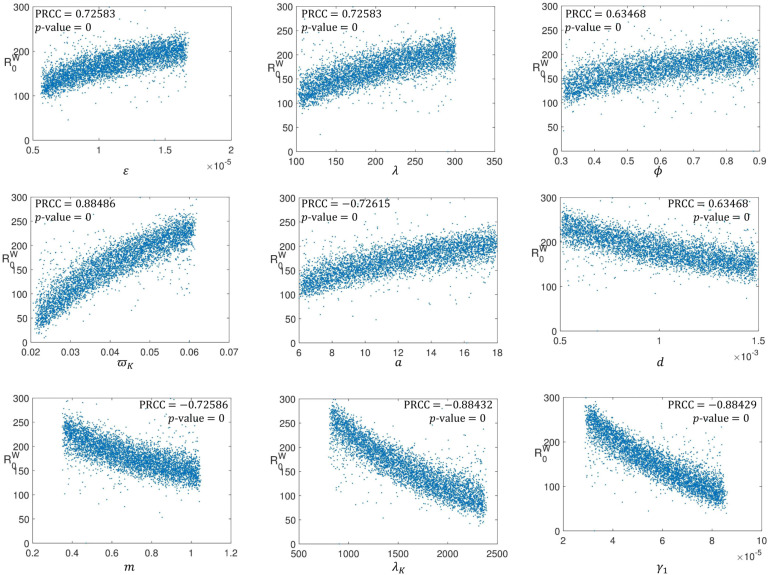

As a measure of uncertainty in our parameter values, we take 50% to the right and left of the parameter values given in Table 2 while is the input function. LHS/PRCC method with 5000 uniformly distributed samples from each parameter range were generated and used as simulation inputs. The PRCC for the model parameters are shown in Fig. 5.3, Fig. 5.4, Fig. 5.5. The magnitude of PRCC shows the influence of the parameter on the dynamics of the disease, the PRCC sign (positive or negative) shows the qualitative relationship between the input parameter and the basic reproduction number while the -value gives the significance of the PRCC value.

Fig. 5.3.

PRCC showing the influence of each parameter on .

Fig. 5.4.

PRCC showing the influence of each parameter on .

Fig. 5.5.

PRCC showing the influence of each parameter on .

Firstly, we investigate the influence of uncertainties in each parameter on the epidemiological part of the model. This we do by taking as the input function and obtain the PRCC result shown in Fig. 5.3. Fig. 5.3 shows the reproduction number is strongly positively sensitive to human-human transmission rate (), human recruitment rate () and progression rate from exposed compartment to infectious class (). However, the reproduction number is strongly negatively sensitive to quarantine rate of exposed human (), quarantine rate of infectious human (), and natural human death rate (). These parameters (, , , , and ) have high PRCC values which are statistically significant thus, uncertainty in any of these parameters is an important contributor to uncertainty in prevalence of the disease. While human-human transmission rate () and progression rate from exposed compartment to infectious class () should be decreased, quarantine rate of exposed human () and quarantine rate of infectious human () should be increased in order to curtail the transmission of the virus. The scatter plots corresponding to parameters , , , and indicate that with these parameters in their respective ranges, chances are that , a condition for disease control. Also since the PRCC values obtained for these parameters are statistically significant, understanding how to control these parameters will greatly help in controlling the spread of the virus among human. The PRCC value obtain for and are very low which implies that these parameters have ignorable impact on the dynamics of the disease.

Secondly, we investigate the influence of uncertainties in each parameter on the in-host part of the model. This is done by taking as the input function and obtain the PRCC result shown in Fig. 5.4. One can see from Fig. 5.4 that all the parameters involved in the dynamics of the within host part have significant PRCC values. Rate at which are infected by SARS-CoV-2 (), recruitment rate of susceptible epithelial cell (), rate at which latently infected epithelial cells become infectious (), death rate for natural killer cells () and production rate of SARS-CoV-2 () all have positive correlation with reproduction number . These parameters need to be reduced in order to control the dynamics of the virus within a host individual however, looking through the scatter plots corresponding to these parameters, has the greatest PRCC value and with this parameter in its range, chances are that . The implication of this is that having vaccines that boost human immunity system is paramount to curtaining SARS-CoV-2 dynamics. is negatively sensitive to natural death rate of epithelial cells (), natural viral clearance rate from biological environment (), constant regeneration rate of natural killer cells () and killing rate of infected epithelial cells by natural killer cell (). Again, one can see that parameters corresponding to immunity are the parameters with most correlation coefficient.

Lastly, we have Fig. 5.5 which shows the impact of the within-host and between-host parameters on the basic reproduction number. It is obvious from the PRCC values in Fig. 5.5 that the influence of between-host parameters is almost insignificant compared to the influence of the within-host parameters. This suggests that in order to control the dynamics of the virus, great attention must be paid to the behaviour of the virus within infected individuals while not neglecting the transmission dynamics. It is also very clear from the scatter diagrams that no single parameter can single-handedly make the basic reproduction number less that unity. This suggests that multiple intervention strategies must be implemented if the spread of SARS-CoV-2 will be curtailed.

5.3. Model simulations

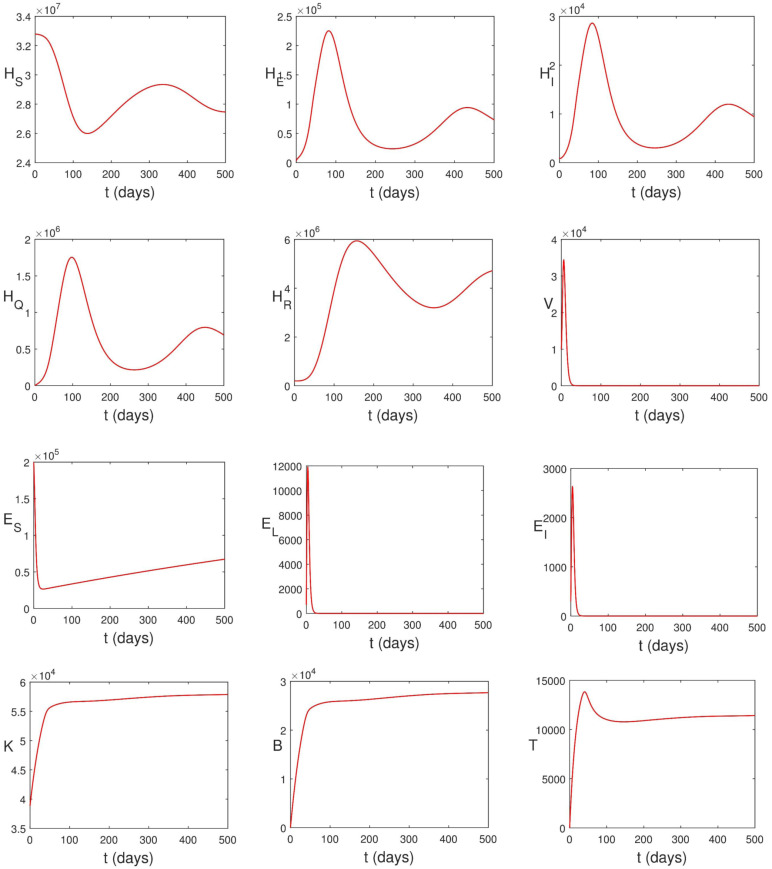

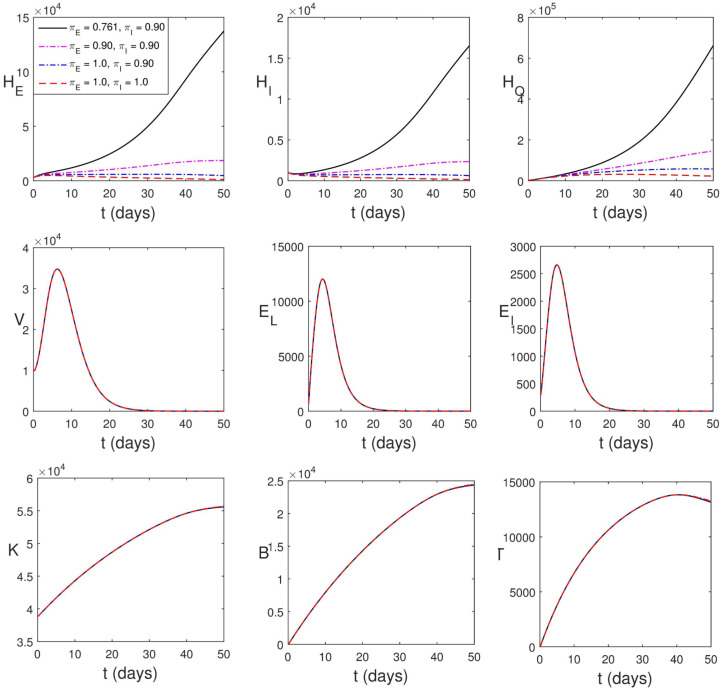

In this section, model (2.13)–(2.12) is solved numerically using two-step fractional Adams Bashforth method (see [74, Theorem 3.2]). Codes are written in MATLAB® for this purpose. Effects of control strategies on the dynamics of the disease are investigated numerically. The parameter values in Table 2 are used to carry out the numerical simulations. We take , , , , , , , , , , and .

Solving model (2.13)–(2.24) numerically, we obtain the graphs in Fig. 5.6. It can be seen that the population of infected epithelial cells decreases. This is as a result of infection by SARS-CoV-2 and the killing effects of natural killer cells and cytotoxic T-cells. This observation is supported by the work of Deinhardt-Emmer et al. [75]. The viral load also decreases due to the presence of B-lymphocytes and the decrease in the population of epithelial cells. In spite of these immune responses, the disease still persists in human population. This is because the remaining virus in human body is enough to ensure that the disease persists in human population. While most articles on the epidemiological dynamics of COVID-19 concluded that reducing the transmission such that will help in curtailing the spread of the virus, this research has shown that this condition is not enough. Both and are necessary before the disease can be curtailed.

Fig. 5.6.

Simulation of (2.13)–(2.24) using parameter values in Table 2.

5.3.1. Influence of viral load on transmission

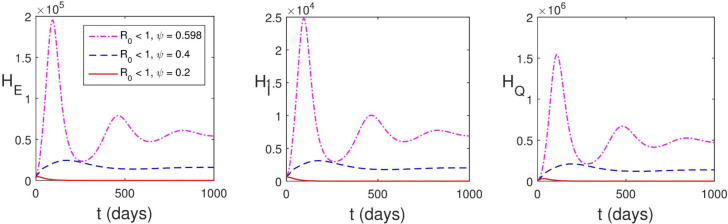

The condition guarantees the local stability of the disease-free equilibrium, however it is shown in Fig. 5.7 that the disease still persists in human population when . This is because the transmission rate depends on the average viral load in infectious individuals whereas the basic reproduction number does not capture this. We therefore have the effective basic reproduction number

where

where is the parameter that accounts for the increase in transmission rate caused by viral load. It can be seen in Fig. 5.7 that has a significant impact on the dynamics and control of SARS-CoV-2. The implication of this is that incomplete recovery from COVID-19 is a treat to the control of the disease. The assumption that transmission rate depends on the viral load was also made in [34] however, there was no discussion on its influence on transmission dynamics of the disease. We conclude this session by stating that is the requirement for the disease control.

Fig. 5.7.

Influence of viral load on transmission.

5.3.2. Intervention strategies

Next we explore various intervention strategies. For each intervention strategy, we compute the percentage death averted (PDA). PDA is the ratio of the total number of death averted to the total number of death when there is no control measure while the total number of death averted (TDA) is the difference between the total death due to infection over the simulation period in the absences of control and the total death due to infection when there is control.

Vaccine

There are many COVID-19 vaccines being used in countries of the world - Moderna mRNA-1273, Pfizer/BioNTech BNT162b2, Gamaleya Sputnik V, Janssen Ad26.COV2.S, Oxford/AstraZeneca AZD1222 and Covishield (Oxford/AstraZeneca formulation) [76]. COVID-19 vaccines help the body to develop immunity to SARS-CoV-2. It normally takes some weeks after vaccination for the body to build resistance against the virus. It is therefore possible for a person to still contract COVID-19 just after vaccination. This is due to the fact that the vaccine has not had sufficient time to offer protection [77]. It was also noted in [78] that COVID-19 vaccine does not provide 100% protection. Since the vaccine works with immune system, we numerically study the impact of natural K-cells, B-lymphocytes and cytotoxic T-cells on the dynamics of the disease in what follows.

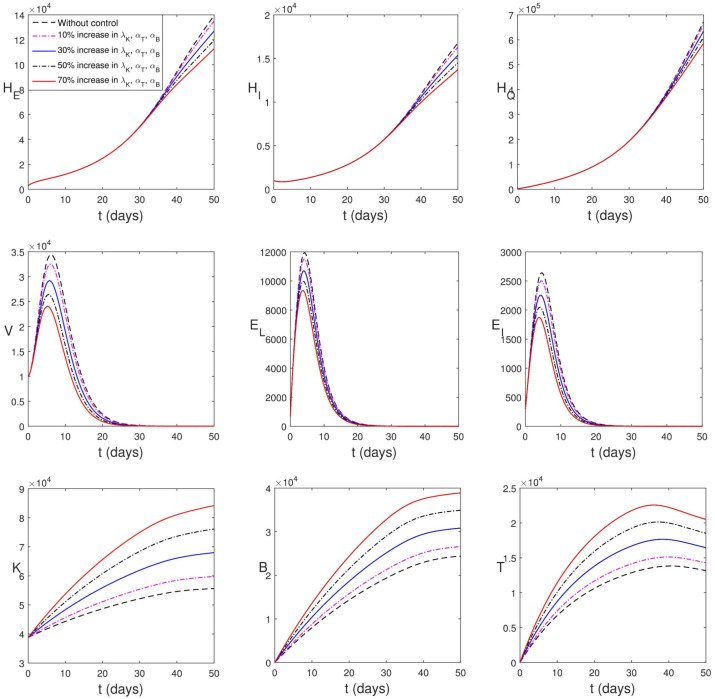

Firstly, we consider vaccination leading to increased amount of natural K-cells, B-lymphocytes and cytotoxic T-cells. As shown in Fig. 5.8, increase in the population of immune compartments lead to a decline in the peak values of viral load and infected epithelial cells. However, in the human population, the impact of this intervention strategy is not seen until after a later time (of about 35 days). The PDA of the strategy is in Table 3.

Fig. 5.8.

Simulation of (2.13)–(2.24) considering the increase in proliferation rates of immune cells.

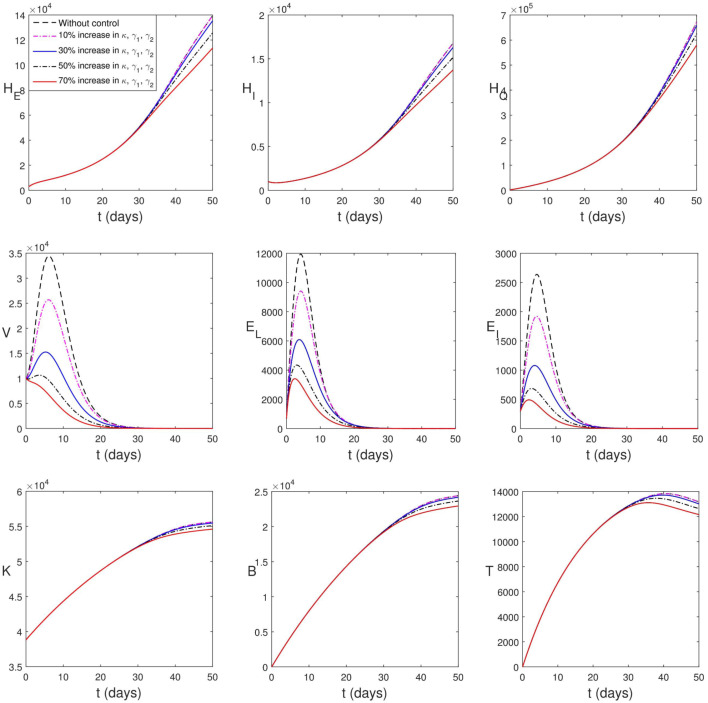

Secondly, we consider vaccination leading to increased efficacy of natural K-cells, B-lymphocytes and cytotoxic T-cells. This is shown in Fig. 5.9. Increase in the efficacy of immune compartments lead to a rapid decline in the peak values of viral load and infected epithelial cells. Also in the case, it will take a while before the impact of this strategy is found in human population. This strategy appears (pictorially) to be more effective however Table 3 shows that it averts less human death when the vaccine improves the efficacy of the immune components by 10% and 30%.

Fig. 5.9.

Simulation of (2.13)–(2.24) with increase in the strength of immune cells.

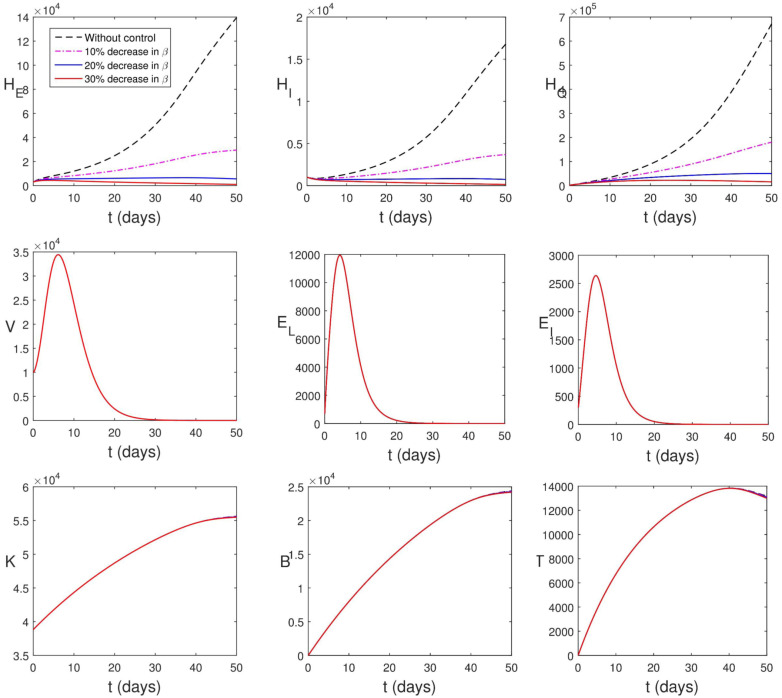

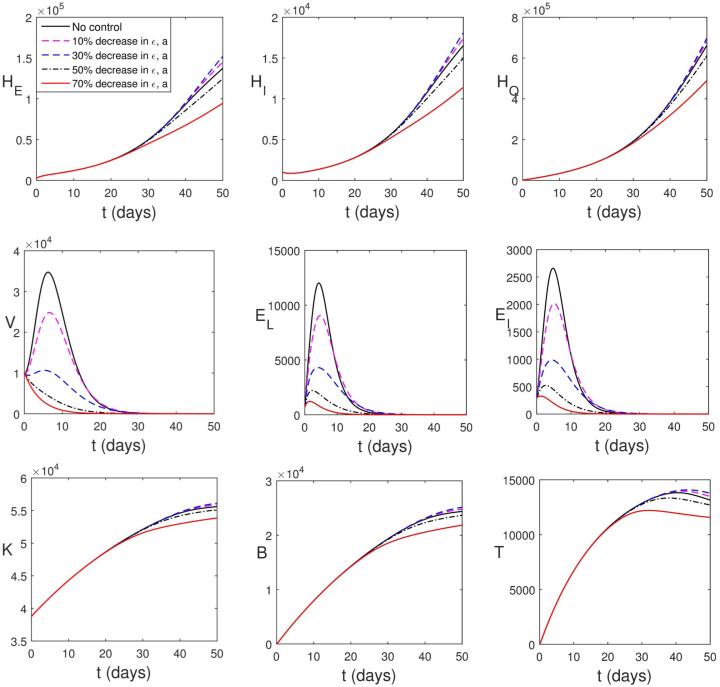

Social distancing, face mask and other measures to reduce transmission rate

It is known that the countries of the world have initiated certain control measures (such as frequent hand washing with alcohol-based sanitizer, use of face masks in public, social distancing, movement restrictions, etc.). Malaysian government has also initiated such containment measures during the period used for parameter estimation. This is responsible for the low value of and high values of and . Yet in this section, we consider the cases where the transmission rate () is further lowered. Fig. 5.10 shows the impact of this strategy. It is obvious that the infected human compartments reduce drastically which accounts for the high percentage death averted (see Table 3). Fig. 5.10 further shows that reduction in transmission rate has negligible impact on within-host dynamics.

Fig. 5.10.

Simulation of (2.13)–(2.24) with reduction in transmission rate.

When there is 30% decrease in transmission rate, , . This accounts for the drastic reduction in the populations of infected individuals. The average viral load per infectious individual also decreases however, the virus remains in the system. A quick way to know that the virus remains in the body is to check the volume of immune cells. A high volume of immune cells is an indication of the presence of virus/pathogens. The remnant virus in the body can cause another surge any time the COVID-19 protocol is relaxed. Thus, taken care of epidemiological components only provides a temporary measure to curtailing the spread of the virus, the within-host dynamics will drive the entire dynamics and the virus will continue to live within human population.

Fig. 5.11 shows the effect of increase in the rate at which infected individuals are detected and quarantined. It is reasonable to assume that it takes a minimum of 1 day to detect and quarantine an infected individual. In Fig. 5.11, the infected human compartments reduce drastically which accounts for the high percentage death averted (see Table 3). Also Fig. 5.11 shows that increase in quarantine rate has negligible impact on within-host dynamics.

Fig. 5.11.

Simulation of (2.13)–(2.24) with increase in the rate at which infected individuals are detected and quarantined.

Reduction in viral infection of epithelial cells using medication or vaccine

Although there is no particular medication for treating COVID-19, people can recover by following a treatment protocol. Nonetheless, there are few questions to consider: Can we have drugs or vaccines that can prevent the epithelial cells from being infected? Can we have drugs or vaccines that can prevent the infected epithelial cells from reproducing the virus? Interferon, a component of human immune system interfere with viral replication and protects uninfected cells from the virus. Interferons, are produced and secreted by infected cells following virus infection. The secreted interferons act on neighboring cells to induce enzymes that render these cells more resistant to viral infection [43]. Resistance to viral infection causes reduction in the infection of epithelial cells by SARS-CoV-2. We therefore investigate the effect of the reduction of infection of epithelial cells by the virus as well as the reduction in the production rate of SARS-CoV-2.

Fig. 5.12 shows the effects of the reduction of infection of epithelial cells by the virus as well as the reduction in the production rate of SARS-CoV-2. This strategy lowers the peak values of viral load and infected epithelial cells however it has no significant effect on the immune cells. Fig. 5.12 and Table 3 show that this strategy does not have immediate impact on the population of infected human until when it is 50% effective. This intervention strategy is very good when combined with other strategies. Table 3 shows a drastic increase in PDA when this strategy is combined with other strategies. This further suggests that vaccines that offer at least 50% reduction in , and at least 50% increase in , , , , , will have a notable impact in controlling the spread of the virus. Our point here is that vaccine/medication should be made to achieve the following purpose: boost immune response, prevents epithelial cells from being infected or prevents (or reduce) infected epithelial cell from producing the virus, hasten the clearance of virus from human body.

Fig. 5.12.

Simulation of (2.13)–(2.24) with decrease in viral infection of epithelial cells.

Table 3.

PDA of intervention strategies.

| Intervention strategy | PDA | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccination | Increased proliferation rate of immune cells () | 10% increase in , , | 1.08% |

| 30% increase in , , | 3.33% | ||

| 50% increase in , , | 5.68% | ||

| 70% increase in , , |

8.07% |

||

| Increased efficacy of immune cells () | 10% increase in , , | 0.10% | |

| 30% increase in , , | 1.33% | ||

| 50% increase in , , | 4.51% | ||

| 70% increase in , , |

9.18% |

||

| () & () | 10% increase in , , , , , | 1.40% | |

| 30% increase in , , , , , | 7.21% | ||

| 50% increase in , , , , , | 16.50% | ||

| 70% increase in , , , , , | 23.48% | ||

| Social distancing, face mask and other measures to reduce transmission | Reduction in transmission rate | 10% decrease in | 65.86% |

| 20% decrease in | 86.52% | ||

| 30% decrease in |

93.45% |

||

| Increase in quarantine rate | , | 73.36% | |

| , | 86.85% | ||

| , | 93.11% | ||

| Reduction in viral infection of epithelial cells using medication or vaccine | Reduction in viral infection of epithelial cells () | 10% reduction in and | 0% |

| 30% reduction in and | 0% | ||

| 50% reduction in and | 5.32% | ||

| 70% reduction in and |

19.31% |

||

| (),(),() | 50% reduction in , and 50% increase in , , , , , | 22.82% | |

| 70% reduction in , and 70% increase in , , , , , | 37.05% | ||

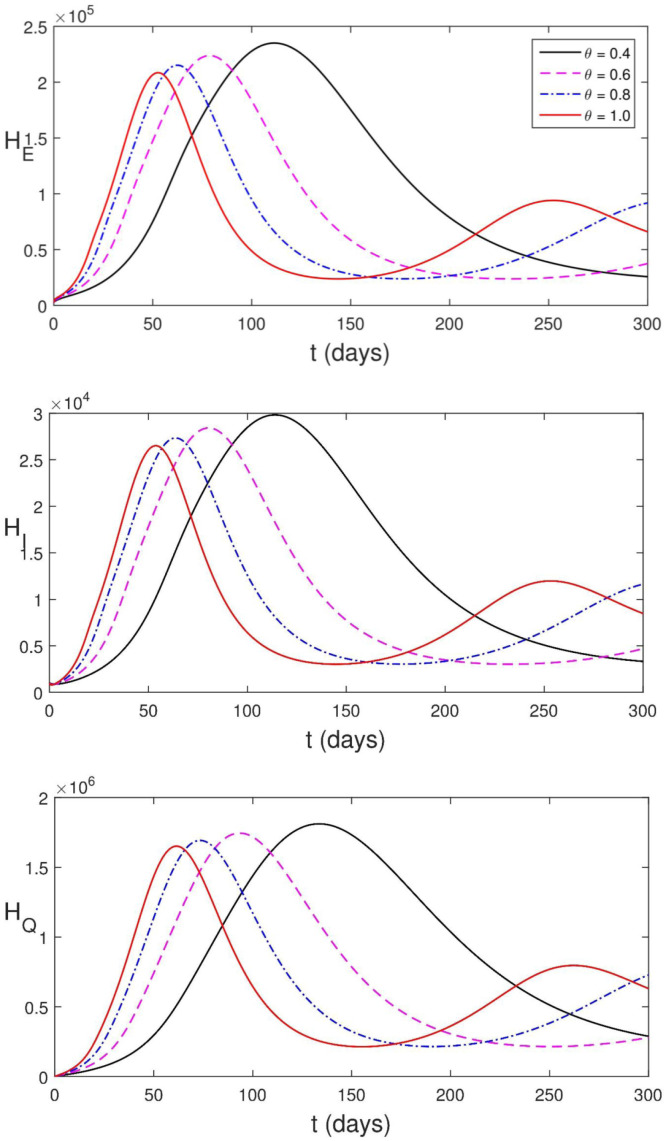

5.3.3. Influence of memory on the disease dynamics

Memory indicates the dependence of a system not only on the present state of the system, but also on the previous history of the system. One advantage of using fractional order differential equations is that it incorporates memory. In Fig. 5.13, we present the effect of memory on the dynamics of the disease on human population. Parameter values in Table 2 are used for our simulation. The dynamics of the disease changes more rapidly as the order of the derivative tends to one while the infection reaches greater peak value as the order of the derivative tends to zero . This is due to the contribution by the previous history of the system. Caputo–Fabrizio fractional derivative has a fading memory [37]. Although fractional derivative incorporates memory, Caputo–Fabrizio fractional derivative is such that the dynamics of the disease is more influenced by the weight given to the moments near the present, and the further we go back in time, the more the weight decreases.

Fig. 5.13.

Simulation of (2.13)–(2.24) showing the effect of memory on the disease dynamics.

6. Conclusion

In this study, we propose a deterministic model which links between-host (population transmission) dynamics with within-host (disease processes within a single host) dynamics. Immune response is incorporated into our model in order to understand the interaction between SARS-CoV-2 and immune cells and how this inform the transmission from human to human. Considering the fact that disease dynamics leaves a memory in human immunologically and epidemiologically, a compartmentalized model with fractional derivative in the sense of Caputo–Fabrizio is proposed. The existence and uniqueness of solution to the model is established by fixed point method. The disease-free equilibrium solution is found to be locally asymptotically stable when . Parameters are estimated by fitting the model to four sets of real-life data simultaneously. We use cumulative confirmed cases, cumulative death cases and active cases data provided by Malaysian government which is publicly available at [54] for our model fitting. For the immunological part of the model, we fit our model to the mean viral load data of Hong Kong patients [66]. Local and global sensitivity analysis are carried via normalize forward sensitivity index and Latin hypercube sampling with partial rank correlation coefficient index respectively. Lastly the model is solved numerically using two-step fractional Adams–Bashforth method and various intervention strategies are investigated. Percentage death averted is computed to compare various intervention strategies.

By data fitting, parameters are estimated and we see that within-host dynamics is the major driver of SARS-CoV-2 dynamics during the period used for data fitting. Data fitting further shows that the order of differential equations involved in the model is 0.569. This therefore means that fractional order differential equations best fit the data than differential equations with classical differentiation.

Sensitivity analysis helps to measure the influence of each parameter in the dynamics of infection being studied. While local sensitivity analysis (LSA) measures the influence of a parameter on the disease dynamics when other parameters are constant, global sensitivity analysis (GSA) measures the influence of uncertainties in parameter values on disease dynamics. Both are needed in order to know the parameters that influence the dynamics of the disease and to propose control measures. LSA reveals that immune response plays sensitive role in controlling the spread of the disease. It further shows that viral transmission rate, progression of exposed individuals to infectious compartment, rate at which susceptible epithelial cells are infected by SARS-CoV-2, production rate of SARS-CoV-2 by infected epithelial cells are to be controlled in order to curtail the spread of the disease. GSA reveals that no single parameter can single-handedly make the basic reproduction number less that unity. Thus, suggesting that multiple intervention strategies must be implemented if the spread of SARS-CoV-2 will be curtailed. Both GSA and LSA suggest that in order to curtail the spread of the virus, the following are necessary: use of drugs/medication to boost immune system, use of medication that prevents epithelial cells from being infected or prevents (or reduce) infected epithelial cell from producing the virus and observance of COVID-19 protocol to reduce transmission.

It is shown, by simulations that in order to reduce human death, it is encouraged to strictly maintain measures that reduce transmission of the virus, however to automatically solve the problem of SARS-CoV-2, attention must be paid to the use of vaccines/medications which greatly improve on human immune systems, prevent epithelial cells from being infected and also prevent infected epithelial cells from reproducing more virus. While immune system (innate and adaptive) needs to be boosted greatly, it is crucial that adaptive immune cells be made to specifically recognise SARS-CoV-2. This is because occasionally, the adaptive immune system may fail to distinguish between what is foreign and what is not and reacts destructively against the host’s own molecules [42].

For our simulation, we employed a particular type of that varies as an increasing function of . This selection was made based on the fact that SARS-CoV-2 transmission rises with an increase in viral load [44]. Despite using a specific form of for the simulation, the outcome of our study remains applicable to any that is an increasing function of . Generalization of the findings to the case where is a piecewise continuous function or time-dependent function is straightforward with little modifications. Summarily, the assumption that the transmission rate increases with viral load aligns with clinical findings and underscores the importance of our model in emphasizing the effects of pandemic prevention and control measures.

Our proposed model is based on other assumptions, one of which is that the entire population is homogeneously mixed. Heterogeneity may be incorporated using a risk-structured model. Another limitation of our multiscale model is that it assumes individual hosts have the same internal states at a time. An improvement in this direction is subject to further study but possible in view of [35], [79]. Nonetheless the result of this work is robust as it presents the efforts of public health interventions to control SARS-CoV-2 which are focused on the reduction of human-to-human transmission of the virus on one hand and medical interventions to treat the disease which are focused on enhancing immune response on the other hand.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Matthew O. Adewole: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Writing – review & editing. Taye Samuel Faniran: Methodology, Investigation, Writing—original draft. Farah A. Abdullah: Software, Validation, Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration. Majid K.M. Ali: Software, Validation, Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Authors like to thank the School of Mathematical Sciences, University Sains Malaysia for providing the facilities used for the research. We would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for valuable suggestions which led to the improvement of the quality of this work.

Data availability

We have stated the data source in the article.

References

- 1.Du S.Q., Yuan W. Mathematical modeling of interaction between innate and adaptive immune responses in COVID-19 and implications for viral pathogenesis. J Med Virol. 2020;92:1615–-1628. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25866. URL https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jmv.25866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harapan H., Itoh N., Yufika A., Winardi W., Keam S., Te H., Megawati D., Hayati Z., Wagner A.L., Mudatsir M. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A literature review. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13(5):667–673. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.03.019. URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1876034120304329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. URLhttps://doi.org/10.1016/S0140–6736(20)30183–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang C., Wang J. A mathematical model for the novel coronavirus epidemic in Wuhan, China. Math Biosci Eng. 2020;17(3):2708–2724. doi: 10.3934/mbe.2020148. URL https://www.aimspress.com/fileOther/PDF/MBE/mbe-17-03-148.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization C. 2020. Coronavirus. URL https://www.who.int/fr/health-topics/coronavirus/coronavirus. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou M., Zhang X., Qu J. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a clinical update. Front Med. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11684-020-0767-8. URL https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s11684-020-0767-8.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li T., Wei C., Li W., Hongwei F., Shi J. Beijing Union Medical College Hospital on ”pneumonia of novel coronavirus infection” diagnosis and treatment proposal (V2.0) Med J Peking Union Med Coll Hosp. 2020 URL http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/11.5882.r.20200130.1430.002.html. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adewole M.O., Onifade A.A., Abdullah F.A., Kasali F., Ismail A.I.M. Modeling the dynamics of COVID-19 in Nigeria. Int J Appl Comput Math. 2021;7(3):67. doi: 10.1007/s40819-021-01014-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adeniyi M.O., Oke S.I., Ekum M.I., Benson T., Adewole M.O. In: Modeling, control and drug development for COVID-19 outbreak prevention. Azar A.T., Hassanien A.E., editors. Springer International Publishing; Cham: 2022. Assessing the impact of public compliance on the use of non-pharmaceutical intervention with cost-effectiveness analysis on the transmission dynamics of COVID-19: Insight from mathematical modeling; pp. 579–618. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samui P., Mondal J., Khajanchi S. A mathematical model for COVID-19 transmission dynamics with a case study of India. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;140 doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110173. 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhadauria A.S., Pathak R., Chaudhary M. A SIQ mathematical model on COVID-19 investigating the lockdown effect. Infect Dis Model. 2021;6:244–257. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2020.12.010. URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2468042721000014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bachar M., Khamsi M.A., Bounkhel M. A mathematical model for the spread of COVID-19 and control mechanisms in Saudi Arabia. Adv Difference Equ. 2021:18. doi: 10.1186/s13662-021-03410-z. Paper No. 253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okposo N.I., Adewole M.O., Okposo E.N., Ojarikre H.I., Abdullah F.A. A mathematical study on a fractional COVID-19 transmission model within the framework of nonsingular and nonlocal kernel. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2021;152 doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2021.111427. Paper No. 111427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adewole M.O., Okekunle A.P., Adeoye I.A., Akpa O.M. Investigating the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 in Nigeria: A SEIR modelling approach. Sci Afr. 2022;15 doi: 10.1016/j.sciaf.2022.e01116. URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2468227622000254?via%3Dihub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.González-Parra G., Arenas A.J. Qualitative analysis of a mathematical model with presymptomatic individuals and two SARS-CoV-2 variants. J Comput Appl Math. 2021;40(6):25. doi: 10.1007/s40314-021-01592-6. Paper No. 199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faniran T.S., Bakare E.A., Falade A.O. The COVID-19 model with partially recovered carriers. J Appl Math. 2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/6406274. 17. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faniran T.S., Ali A., Al-Hazmi N.E., Asamoah J.K.K., Nofal T.A., Adewole M.O. New variant of SARS-CoV-2 dynamics with imperfect vaccine. Complexity. 2022;2022 URL https://www.hindawi.com/journals/complexity/2022/1062180/ [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mondal J., Khajanchi S. Mathematical modeling and optimal intervention strategies of the COVID-19 outbreak. Nonlinear Dynam. 2022;109:177–202. doi: 10.1007/s11071-022-07235-7. URL https://europepmc.org/backend/ptpmcrender.fcgi?accid=PMC8801045&blobtype=pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kifle Z.S., Obsu L.L. Mathematical modeling for COVID-19 transmission dynamics: A case study in Ethiopia. Results Phys. 2022;34:448–456. doi: 10.1016/j.rinp.2022.105191. URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211379722000122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Almocera A.E.S., Quiroz G., Hernandez-Vargas E.A. Stability analysis in COVID-19 within-host model with immune response. Commun Nonlinear Sci Numer Simul. 2021;95:15. doi: 10.1016/j.cnsns.2020.105584. Paper No. 105584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li C., Xu J., Liu J., Zhou Y. The within-host viral kinetics of SARS-CoV-2. Math Biosci Eng. 2020;17(4):2853–2861. doi: 10.3934/mbe.2020159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nath B.J., Dehingia K., Mishra V.N., Chu Y.-M., Sarmah H.K. Mathematical analysis of a within-host model of SARS-CoV-2. Adv Difference Equ. 2021:11. doi: 10.1186/s13662-021-03276-1. Paper No. 113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghosh I. Within host dynamics of SARS–CoV–2 in humans: Modeling immune responses and antiviral treatments. SN Comput Sci. 2021;2 doi: 10.1007/s42979-021-00919-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vaidya N.K., Bloomquist A., Perelson A.S. Modeling within-host dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 infection: A case study in ferrets. Viruses. 2021;13(8):1635. doi: 10.3390/v13081635. URL https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8402735/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heitzman-Breen N., Ciupe S.M. Modeling within-host and aerosol dynamics of SARS-CoV-2: The relationship with infectiousness. PLoS Comput Biol. 2022;18(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009997. URL https://journals.plos.org/ploscompbiol/article?id=10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garira W., Mathebula D., Netshikweta R. A mathematical modelling framework for linked within-host and between-host dynamics for infections with free-living pathogens in the environment. Math Biosci. 2014;256:58–78. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiyaka C., Garira W., Dube S. Transmission model of endemic human malaria in a partially immune population. Math Comput Modelling. 2007;46(5–6):806–822. doi: 10.1016/j.mcm.2006.12.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feng Z., Velasco-Hernandez J., Tapia-Santos B. A mathematical model for coupling within-host and between-host dynamics in an environmentally-driven infectious disease. Math Biosci. 2013;241(1):49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bundy D.A., Grenfell B.T., Rajagopalan P. Immunoepidemiology of lymphatic filariasis: the relationship between infection and disease. Parasitol Today. 1991;7(3):71–75. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(91)90038-P. URL . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang H.M. Malaria transmission model for different levels of acquired immunity and temperature-dependent parameters (vector) Rev Saude Publica. 2000;34:223–231. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102000000300003. URL https://www.scielo.br/j/rsp/a/ccLrLgyDmvvfxCfRSmcsvSP/?lang=en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mideo N., Alizon S., Day T. Linking within- and between-host dynamics in the evolutionary epidemiology of infectious diseases. Trends Ecol Evol. 2008;23(9):511–517. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2008.05.009. URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0169534708002188#:~:text=The%20within%2Dhost%20dynamics%20will,might%20then%20alter%20inoculum%20size. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bellomo N., Burini D., Outada N. Multiscale models of COVID-19 with mutations and variants. Netw Heterog Media. 2022;17(3):293–310. doi: 10.3934/nhm.2022008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bellomo N., Bingham R., Chaplain M.A.J., Dosi G., Forni G., Knopoff D.A., Lowengrub J., Twarock R., Virgillito M.E. A multiscale model of virus pandemic: heterogeneous interactive entities in a globally connected world. Math Models Methods Appl Sci. 2020;30(8):1591–1651. doi: 10.1142/S0218202520500323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang X., Wang S., Wang J., Rong L. A multiscale model of COVID-19 dynamics. Bull Math Biol. 2022;84(9):41. doi: 10.1007/s11538-022-01058-8. Paper No. 99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang X., Ruan Z., Zheng M., Zhou J., Boccaletti S., Barzel B. Epidemic spreading under mutually independent intra- and inter-host pathogen evolution. Nature Commun. 2022;13:6218. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-34027-9. URL https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-022-34027-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moore E.J., Sirisubtawee S., Koonprasert S. A Caputo-Fabrizio fractional differential equation model for HIV/AIDS with treatment compartment. Adv Difference Equ. 2019:20. doi: 10.1186/s13662-019-2138-9. Paper No. 200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Caputo M., Fabrizio M. A new definition of fractional derivative without singular kernel. Progr Fract Differ Appl. 2015;1(2):73–85. URL http://www.naturalspublishing.com/files/published/0gb83k287mo759.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doherty P.C., Turner S.J., Webby R.G., Thomas P.G. Influenza and the challenge for immunology. Nat Immunol. 2006;7(5):449–455. doi: 10.1038/ni1343. URL https://www.nature.com/articles/ni1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li G., Fan Y., Lai Y., Han T., Li Z., Zhou P., Pan P., Wang W., Hu D., Liu X., Zhang Q., Wu J. Coronavirus infections and immune responses. J Med Virol. 2020;92:424––432. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25685. URL https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jmv.25685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uchiyama T., Nelson D.L., Fleisher T.A., Waldmann T.A. A monoclonal antibody (anti-Tac) reactive with activated and functionally mature human T cells. II. Expression of Tac antigen on activated cytotoxic killer T cells, suppressor cells, and on one of two types of helper T cells. J Immunol. 1981;126(4):1398–1403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meckiff B.J., Ramírez-Suástegui C., Fajardo V., Chee S.J., Kusnadi A., Simon H., Eschweiler S., Grifoni A., Pelosi E., Weiskopf D., Sette A., Ay F., Seumois G., Ottensmeier C.H., Vijayanand P. Imbalance of regulatory and cytotoxic SARS-CoV-2-reactive CD4+ T cells in COVID-19. Cell. 2020;183(5):1340–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alberts B., Johnson A., Lewis J., et al. Molecular biology of the cell. 4th ed. Garland Science; New York: 2002. The adaptive immune system. Ch. 24, URL https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK21070/ [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lodish H., Berk A., Kaiser C.A., Krieger M., Scott M.P., Bretsher A., Ploegh H., Matsudaira P. W. H. Freeman and Company; 2008. Molecular cell biology. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bhavnani D., James E.R., Johnson K.E., Beaudenon-Huibregtse S., Chang P., Rathouz P.J., Weldon M., Matouschek A., Young A.E. SARS-CoV-2 viral load is associated with risk of transmission to household and community contacts. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22:672. doi: 10.1186/s12879-022-07663-1. URL https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-022-07663-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marzban S., Han R., Juhász N., Röst G. A hybrid PDE–ABM model for viral dynamics with application to SARS-CoV-2 and influenza. R Soc Open Sci. 2021;8 doi: 10.1098/rsos.210787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li Q., Guan X., Wu P., Wang X., Zhou L., Tong Y., Ren R., Leung K.S., Lau E.H., Wong J.Y., Xing X., Xiang N., Wu Y., Li C., Chen Q., Li D., Liu T., Zhao J., Liu M., Tu W., Chen C., Jin L., Yang R., Wang Q., Zhou S., Wang R., Liu H., Luo Y., Liu Y., Shao G., Li H., Tao Z., Yang Y., Deng Z., Liu B., Ma Z., Zhang Y., Shi G., Lam T.T., Wu J.T., Gao G.F., Cowling B.J., Yang B., Leung G.M., Feng Z. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–Infected pneumonia. New Engand J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. URL https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alberts B., Johnson A., Lewis J., et al. Molecular biology of the cell. 4th ed. Garland Science; New York: 2002. Helper T cells and lymphocyte activation. Ch. 24, URL https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK26827/ [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang J, Kaperak C, Sato T, Sakuraba A. COVID-19 reinfection: a rapid systematic review of case reports and case series. J Investig Med, 69. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Lauer S.A., Grantz K.H., Bi Q., Jones F.K., Zheng Q., Meredith H.R., et al. The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: Estimation and application. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(9):577–582. doi: 10.7326/M20-0504. URL https://annals.org/aim/fullarticle/2762808/incubation-period-coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-from-publicly-reported. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li R., Pei S., Chen B., Song Y., Zhang T., Yang W., et al. Substantial undocumented infection facilitates the rapid dissemination of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) Science. 2020;368(6490):489–493. doi: 10.1126/science.abb3221. URL https://science.sciencemag.org/content/368/6490/489/tab-pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Iboi E.A., Sharomi O., Ngonghala C.N., Gumel A.B. Mathematical modeling and analysis of COVID-19 pandemic in Nigeria. Math Biosci Eng. 2020;17(6):7192–7220. doi: 10.3934/mbe.2020369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ferguson NM, Laydon D, Nedjati-Gilani G, Imai N, Ainslie K, Baguelin M, et al. Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID-19 mortality and healthcare demand. Imperial College London, 10.25561/77482, (16-03-2020), URL. [DOI]

- 53.Tang B., Bragazzi N.L., Li Q., Tang S., Xiao Y., Wu J. An updated estimation of the risk of transmission of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Infect Dis Model. 2020;5:248–255. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2020.02.001. URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S246804272030004X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.GITHUB. [link],URL https://github.com/MoH-Malaysia/covid19-public.

- 55.World health organization (WHO), webpage: www.who.org.

- 56.Li C., Xu J., Liu J., Zhou Y. The within-host viral kinetics of SARS-CoV-2. Math Biosci Eng. 2020;17(4):2853–2861. doi: 10.3934/mbe.2020159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chowdhury S.M.E.K., Chowdhury J.T., Ahmed S.F., Agarwal P., Badruddin I.A., Kamangar S. Mathematical modelling of COVID-19 disease dynamics: interaction between immune system and SARS-CoV-2 within host. AIMS Math. 2022;7(2):2618–2633. doi: 10.3934/math.2022147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ben-Shachar R., Koelle K. Minimal within-host dengue models highlight the specific roles of the immune response in primary and secondary dengue infections. J R Soc Interface. 2015;12(103) doi: 10.1098/rsif.2014.0886. URL https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4305404/pdf/rsif20140886.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kuznetsov V.A., Makalkin I.A., Taylor M.A., S. P.A. Nonlinear dynamics of immunogenic tumors: Parameter estimation and global bifurcation analysis. Bull Math Biol. 1994;56(2):295–321. doi: 10.1007/BF02460644. URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0092824005802605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.de Pillis L.G., Gu W., Radunskaya A.E. Mixed immunotherapy and chemotherapy of tumors: modeling, applications and biological interpretations. J Theoret Biol. 2006;238(4):841–862. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2005.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Karita H.C.S., Dong T.Q.D., Johnston C., Neuzil K.M., Paasche-Orlow M.K., Kissinger P.J., Bershteyn A., Thorpe L.E., Deming M., Kottkamp A., Laufer M., Landovitz R.J., Luk A., Hoffman R., Roychoudhury P., Magaret C.A., Greninger A.L., Huang M.-L., Jerome K.R., Wener M., Celum C., Chu H.Y., Baeten J.M., Wald A., Barnabas R.V., Brown E.R. Trajectory of viral RNA load among persons with incident SARS-CoV-2 G614 infection (wuhan strain) in association with COVID-19 symptom onset and severity. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(1) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.42796. URL https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2787768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Losada J., Nieto1 J.J. Properties of a new fractional derivative without Singular Kernel. Progr Fract Differ Appl. 2015;1(2):87–92. URL http://www.naturalspublishing.com/files/published/2j1ns3h8o2s789.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Correa-Escudero I.L., Gómez-Aguilar J.F., López-López M.G., Alvarado-Martínez V., Baleanu D. Correcting dimensional mismatch in fractional models with power, exponential and proportional kernel: Application to electrical systems. Results Phys. 2022;40 URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211379722005083?via%3Dihub. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li H., Cheng J., Li H.-B., Zhong S.-M. Stability analysis of a fractional-order linear system described by the Caputo–fabrizio derivative. Mathematics. 2019;7(2):200. URL https://www.mdpi.com/2227-7390/7/2/200. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Polyanin A.D., Manzhirov A.V. Chapman & Hall/CRC; Boca Raton, FL: 2007. Handbook of mathematics for engineers and scientists. [Google Scholar]

- 66.To K.K.-W., Tsang O.T.-Y., Leung W.-S., Tam A.R., Wu T.-C., Lung D.C., Yip C.C.-Y., Cai J.-P., Chan J.M.-C., Chik T.S.-H., Lau D.P.-L., Choi C.Y.-C., Chen L.-L., Chan W.-M., Chan K.-H., Ip J.D., Ng A.C.-K., Poon R.W.-S., Luo C.-T., Cheng V.C.-C., Chan J.F.-W., Hung I.F.-N., Chen Z., Chen H., Yuen K.-Y. Temporal profiles of viral load in posterior oropharyngeal saliva samples and serum antibody responses during infection by SARS-CoV-2: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(5):565–574. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30196-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.MathWorks. https://www.mathworks.com/help/optim/ug/lsqcurvefit.html.

- 68.Saltelli A., Ratto M., Andres T., Campolongo F., Cariboni J., Gatelli D., et al. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Chichester; 2008. Global sensitivity analysis. The primer. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hoops S., Hontecillas R., Abedi V., Leber A., Philipson C., Carbo A., Bassaganya-Riera J. Computational immunology: Models and tools. Elsevier; 2016. Ordinary differential equations (ODEs) based modeling; pp. 63–78. Ch. 5, URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128036976000059. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Razavi S., Gupta H.V. What do we mean by sensitivity analysis? The need for comprehensive characterization of “global” sensitivity in Earth and Environmental systems models. Water Resour Res. 2015;51(5):3070–3092. URL https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/2014WR016527. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chitnis N., Hyman J.M., Cushing J.M. Determining important parameters in the spread of malaria through the sensitivity analysis of a mathematical model. Bull Math Biol. 2008;70(5):1272–1296. doi: 10.1007/s11538-008-9299-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Marino S., Hogue I.B., Ray C.J., Kirschner D.E. A methodology for performing global uncertainty and sensitivity analysis in systems biology. J Theoret Biol. 2008;254(1):178–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Blower S.M., Dowlatabadi H. Sensitivity and uncertainty analysis of complex-models of disease transmission—an HIV model, as an example. Int Stat Rev. 1994;62:229–243. URL https://mysite.science.uottawa.ca/rsmith43/mat4996/blower_lhsmethodology.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Atangana A., Owolabi K.M. New numerical approach for fractional differential equations. Math Model Nat Phenom. 2018;13(1):21. doi: 10.1051/mmnp/2018010. Paper No. 3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Deinhardt-Emmer S., Böttcher S., Häring C., Giebeler L., Henke A., Zell R., Jungwirth J., Jordan P.M., Werz O., Hornung F., Brandt C., Marquet M., Mosig A.S., Pletz M.W., Schacke M., Rödel R., Nietzsche S., Löffler B., Ehrhardt C. SARS-CoV-2 causes severe epithelial inflammation and barrier dysfunction. J Virol. 2021;95(10):e00110–e00121. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00110-21. URL https://journals.asm.org/doi/pdf/10.1128/JVI.00110-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.COVID19 Vaccine Tracker. 2021, [link]URL https://covid19.trackvaccines.org/country/nigeria/.

- 77.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/keythingstoknow.html.

- 78.NHS. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/coronavirus-covid-19/coronavirus-vaccination/coronavirus-vaccine/.

- 79.Martcheva M., Tuncer N., St Mary C. Coupling within-host and between-host infectious diseases models. Biomath. 2015;42 URL https://people.clas.ufl.edu/maia/files/WHBHREVv6-BIOMATH-R.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

We have stated the data source in the article.