Abstract

Inequality is increasingly recognized as a major problem in contemporary society. The causes and consequences of inequality in wealth and power have long been central concerns in the social sciences, whereas comparable research in biology has focused on dominance and reproductive skew. This theme issue builds on these existing research traditions, exploring ways they might enrich each other, with evolutionary ecology as a possibly unifying framework. Contributors investigate ways in which inequality is resisted or avoided and developed or imposed in societies of past and contemporary humans, as well as a variety of social mammals. Particular attention is paid to systematic, socially driven inequality in wealth (defined broadly) and the effects this has on differential power, health, survival and reproduction. Analyses include field studies, simulations, archaeological and ethnographic case studies, and analytical models. The results reveal similarities and divergences between human and non-human patterns in wealth, power and social dynamics. We draw on these insights to present a unifying conceptual framework for analysing the evolutionary ecology of (in)equality, with the hope of both understanding the past and improving our collective future.

This article is part of the theme issue ‘Evolutionary ecology of inequality’.

Keywords: egalitarian, hierarchy, humans, inheritance, mammals, wealth

1. Introduction

Our goal in assembling this issue is to explore the insights that evolutionary ecology can bring to the study of inequality, while encouraging transdisciplinary dialogue and a pluralistic view of relevant ideas. The forms and dynamics of inequality have long been central concerns in several social sciences, including anthropology and archaeology, economics, history, political science and sociology. In biology, the study of dominance and reproductive skew are well-established fields of inquiry [1–3]. This theme issue draws on these existing research traditions, exploring ways they might enrich each other, or perhaps be synthesized. The papers herein investigate mechanisms shaping variation in inequality, paying attention to ways in which inequality is resisted or avoided as well as developed or imposed. Most of them do so within the framework of evolutionary ecology and examine the utility of social science concepts such as wealth, property, social power and institutions.

Defining inequality is not straightforward, as its meaning depends on context, ranging from colloquial use to economic analysis to mathematics. In empirical research, inequality is typically defined through quantitative measures such as Gini coefficients or skew indices, with the factors shaping these variables left open to investigation. While straightforward, this lumps variation in a given trait (e.g. accumulated wealth or reproductive success) due to genetic endowment and random accidents with that due to social interactions. Accordingly, for present purposes we define inequality as those differences that are imposed on individuals (or classes of individuals) by structural features of a social system. Thus, inequality as used here focuses on that subset of phenotypic variation shaped by social structures—reinforced within or across generations—that privileges some individuals over others.

Furthermore, our concern is with systematic, socially driven inequality in wealth and the effects this has on differential power (social influence or control over conspecifics), well-being (health, stress, mortality, etc.), reproduction and ultimately fitness. We define wealth as attributes or possessions that contribute to well-being or fitness. Forms of wealth can be material (resources, such as food or territory), relational (social networks) or embodied (knowledge, skill) [4–7]. Note that in this view, power or social influence is viewed as a consequence of underlying wealth inequalities, although more power can also contribute to subsequent wealth accumulation.

2. Comparative inequality: theory and evidence

For this theme issue, we formulated several key questions about inequality (as defined above):

-

(a)

What factors shape variation in inequality within and across species?

-

(b)

How and why is inequality in human societies similar and different from other mammals, including our primate relatives?

-

(c)

Why was persistent institutionalized inequality in Homo sapiens rare for most of our species' existence, yet spread widely in recent millennia?

-

(d)

What are the consequences of inequality for differences in social influence, nutritional state, well-being, survival and reproduction?

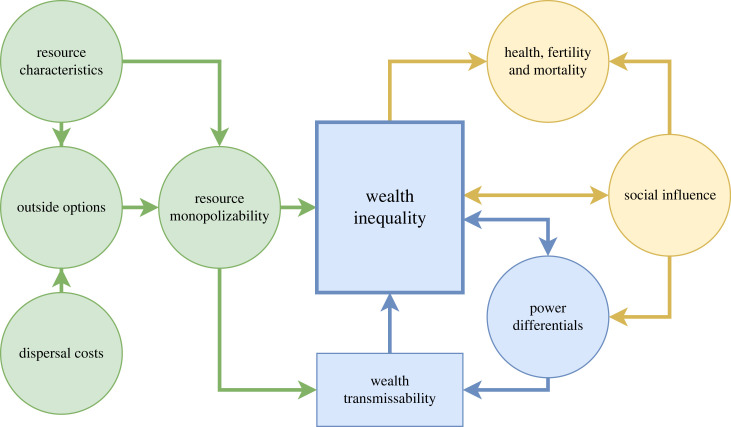

The following discussion of the papers in this issue and related research is organized around these questions. We build on this information to synthesize a conceptual framework for understanding the evolutionary ecology of (in)equality (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Some causes and consequences of wealth inequality. The left side of the diagram includes ecological and economic drivers of inequality, while the right side lists major biological outcomes. Arrows indicate the primary pathways delineated in theoretical and empirical research, although additional possible pathways and feedback loops are omitted in the interest of legibility. (Online version in colour.)

(a) . Factors shaping variation in inequality

Considerable research across multiple disciplines has contributed insights into the variables and mechanisms influencing variation in inequality. Within the evolutionary ecology paradigm, perhaps the most frequently invoked drivers are ecological parameters such as resource density, predictability, and patchiness or clumping that facilitates control by a subset of individuals within a society [8,9]. In this issue, theoretical and cross-cultural analyses highlight the effect of these variables in shaping the form and degree of inequality [10–12]. Their importance is given further support in archaeological case studies, which also implicate Malthusian population dynamics involving competition for diminishing resources [13,14].

From a strategic or game-theoretical standpoint, another key variable is the available alternatives to being subordinated—defined as wielding relatively low power within a social group [15,16]. These alternatives, often termed ‘outside options’, might involve joining a different group, migrating to an ‘empty’ locale, or even actively resisting forms of oppression (e.g. [17]). Which options are feasible, and their associated consequences for individuals, is determined to a considerable degree by local or regional socioecological conditions. Theory supported by empirical evidence indicates that switching groups or migrating to greener pastures has lower odds of succeeding as population density increases and/or as resource-quality gradients steepen, as discussed in several papers in this issue [11,18,19]. Resistance to subordination can be costly for both subordinates and dominants [20], and the balance of these costs will shape the outcome; in some cases, threats may be enough to exact a better deal (reduced inequality in resource sharing) for subordinates, as examined in concession models of reproductive skew [21,22] or bargaining models in social science [23,24].

Factors facilitating or impeding wealth inheritance can play a prominent role in shaping inequality for both humans [4,25,26] and non-humans [5,7]. Although any of the three forms of wealth noted above can be transmitted to descendants, material forms are generally more successfully inherited. These can include arable land, livestock, durable goods, resource patches, burrows, food caches, nesting sites and the like, as discussed in several papers in this issue [12–14,20,27,28]. However, embodied wealth such as skills or knowledge passed down from parents [27] or parental investment in offspring condition [29,30] can be important as well, contributing to developmental origins of inequality [30]. This differential access early in life can impose lifetime consequences for individuals [31]. Likewise, relational wealth such as social support from kin or allies can play critical roles in some cases [7,21,28,32].

Finally, factors that do not fit readily into the tripartite wealth typology appear to shape variation in inequality in particular cases. Specifically, the ways in which hierarchy can facilitate decision-making and other forms of collective action have received prominent attention in the animal behaviour literature on movement decisions [33], as well as analyses of variation in political forms of human societies [24,34].

(b) . Comparing humans and other species

One goal of this theme issue is to help strengthen theoretical and empirical linkages in research on inequality across biological and social science disciplines. We are well aware of the difficulties and potential pitfalls in comparing human and non-human behaviour, particularly when it concerns complex patterns of behaviour such as property/territory inheritance [35] and systems of domination and subordination [36]. Nevertheless, there is much to be gained from careful and nuanced sharing of concepts between evolutionary biology and social sciences. The benefits of such cross-fertilization are exemplified by the adaptation of game theory to evolutionary contexts by biologists, and in turn the near replacement of classical game theory with evolutionary game theory in economics. Such mutual influence is central to several papers in this issue [11,18,34].

We stress that comparison does not entail ignoring differences, but rather aims to reveal commonalities and contrasts within and among species to enhance our understanding of the socioecological circumstances that promote more or less equal societal structures. Such differences between human and non-human animals are driven in part by human reliance on symbolic communication (syntactic language) and a depth and complexity of cultural inheritance unequalled in other species [37,38]. Yet, many species share common mechanisms for promoting or disrupting social structures that contribute to inequality. Whereas the study of evolutionary processes in non-human animals can offer insights into factors shaping the origins of power dynamics (e.g. [39]) and cooperation (e.g. [40]) in humans, approaches used to study humans may also offer new insights and theoretical predictions that can be used in turn to study and explain patterns of equality and inequality in non-human animals [5]. In sum, we argue that cross-species comparison can provide valuable insights into the factors contributing to equality and inequality.

The empirical papers in this issue focus almost exclusively on mammalian species, including humans. We offer two primary justifications for this focus. First, the reproductive ecology of social mammals constrains the dynamics of inequality in ways that differ greatly from the possible forms it can take in many other taxonomic groups, and markedly so in social insects. Second, the mechanisms underlying unequal access to resources in humans are more comparable (whether or not they are homologous) in social mammals, including other primates. Nevertheless, we recognize that broader comparative studies might prove fruitful.

When comparing inequality in humans and other mammals, both similarities and differences are evident. Drivers of inequality that appear similar across species include resource control, kin-based politics and coalitions of both dominants and subordinates competing for power. Comparative evidence on these is found in many articles in this issue.

One factor central to inequality in human societies is the role of institutions. Some scholars define institutions quite broadly; for example, ‘locally stable, widely shared rules that regulate social interaction’ ([41], p. 326). Others adopt a narrower meaning that refers to a set of explicit roles assigned to individuals and the rules governing their behaviour (cf. [25,34]). Most would agree that the term covers both formal institutions such as legal rules and procedures, inheritance systems, political offices (and their rules of succession), marriage rules, economic regulations, and class- and caste-based systems, as well as various informal practices or norms.

Analyses of inequality in human societies, including several in this issue, often focus on whether and when inequality becomes institutionalized. All human societies, and indeed those of other social species, exhibit achieved differences between individuals in status, skill, and influence or power over others, including at minimum differences due to age and strength. However, these forms of inequality, even though recurrent, wax and wane with their underlying individual attributes; they are easily reversed and are not passed to others via institutions [42]. Institutionalized inequality is qualitatively different, involving codified differences in power and wealth that are ascribed to individuals via inheritance (e.g. hereditary slavery, aristocracy) or some other institutional procedure (e.g. priesthood) [9]. Most anthropologists and archaeologists believe that institutionalized inequality was absent for most of the 300 or so millennia that Homo sapiens has existed, as discussed in the following subsection.

Social interactions in non-human animals are often also structured by roles and patterns analogous to institutions, such as dominance hierarchies, alliances, leadership roles, territoriality and mating systems. Such structures are particularly evident in animal societies in which hierarchical positions are passed on from one generation to another via arbitrary social conventions (e.g. nepotistic inheritance) to reinforce intergenerational legacies of inequality [43]. Matrilineal inheritance structures profoundly influence resource access, survival and reproduction in non-human animals [7], but matrilineal human societies, such as that of Mosuo, possess striking similarities in how power and access is transferred among maternal lines [27]. Like humans, other mammals also possess countering mechanisms such as inequity aversion, peacekeeping, forgiveness and sharing food with non-kin [44–48] to reduce inequality [7]. Moreover, variation in dominance structures across mammals exhibits minimal phylogenetic constraints, revealing greater flexibility in this social trait than previously assumed [7]. Nevertheless, institutions clearly have much greater elaboration and variability in our species compared to any other single non-human species. Presumably, this is due to much higher rates of cultural transmission and resultant behavioural diversification, as well as cumulative cultural evolution [37], resulting from the high-volume information flow made possible by language [49]. Comparative study of these processes across the Tree of Life could uncover the conditions promoting more or less equal societies, revealing the general processes that (de)stabilize social structures that contribute to inequality.

Although human populations do certainly exhibit reproductive skew [50], extreme forms of reproductive suppression and altruism such as in mole rats [20] and social insects [51] have little human counterpart. One key difference in the human case is attributed to enhanced paternity certainty and resultant paternal investment, resulting in a major expansion of kinship ties and the option of patrilineal as well as matrilineal networks and inheritance pathways [27,28,52,53]. In addition, ecological changes in the hominin lineage may have favoured paternal provisioning [54]. Data in this special issue also highlight that patterns of reproductive skew in other species are by no means fixed or static but rather vary from population to population within species. For example, reproductive skew among our closest relatives, chimpanzees and bonobos, also varies within species and among communities [21]. These patterns reflect adaptive variability and the flexible nature of power systems in mammalian societies.

In sum, differences between humans and other mammals are apparent at the levels of mechanisms, intensity and dynamics of inequality, while similarities appear to lie in evolutionary ecology principles that account for these patterns. Analysis of these factors can offer new insights into the mechanisms promoting diversity in social structures.

(c) . The late blooming of persistent institutionalized inequality

Many small-scale human societies are relatively egalitarian, meaning that status and power differentials within age and gender categories are muted and primarily achieved rather than ascribed, and access to subsistence resources is equalized through sharing and other means. This contrasts with many social mammals, including some of our closest primate relatives [7,55]. For non-human species, dominance due to size or strength is best classified as achieved, whereas dominance due to mother's rank is ascribed. Some argue that human egalitarianism is due to countermeasures such as active resistance to domination or collective punishment of aggrandizing behaviour [56–58], while others point to ecological drivers such as risk-pooling and gains from cooperation [59,60].

Be that as it may, the archaeological record indicates that institutionalized inequality, as measured typically by grave goods, as well as by variations in residential size and other architectural signatures, is rare until Holocene times (beginning roughly 11 millennia ago) [61–63] although some contest this [64], and periodic episodes of inequality that came and went in the more distant past may prove to have been more common than currently documented. But it is only in the past few millennia that non-egalitarian and even markedly stratified systems have replaced nearly all such societies. The near absence of institutionalized differences in wealth and power for most of the history of our species raises the question of what changed. Several papers in this special issue offer important clues [10,14,18]. The development and spread of agriculture certainly accounts for some of the temporal dynamics of institutionalized inequality, but its absence in low-intensity ‘horticultural’ societies [65], muted presence even among some agriculturally dependent state-level societies [66–68] and multiple cases of non-egalitarian hunter–gatherers [69,70] indicate it cannot be the only, or perhaps even the main, explanation. In terms of timing, the high-amplitude high-frequency climate fluctuations of the Pleistocene, and their amelioration in the Holocene, suggests a historically contingent answer for the late emergence of inequality [9,71]. In particular, Holocene climate amelioration increases the economic defensibility of high-quality resource patches by dominants, who can transmit these holdings to descendants as well as offer access to subordinates in exchange for labour and other services [9,10].

The asymmetries in bargaining power that arise from controlling highly productive resources (especially arable land) in turn fuel economic specialization and exchange, further cementing institutionalized inequality [16,66,72]. However, particular ecological circumstances can limit economic productivity even in Holocene climates, thus allowing small-scale relatively egalitarian systems to persist into the contemporary historic period [73]. This undercuts misinterpretations of Holocene history as a uniform process and highlights the multifaceted conditions that are necessary for the emergence and persistence of inequality.

(d) . Biological consequences of inequality

There is considerable research on the effects of inequality on various biologically significant dimensions, including health and mortality, nutrition or food intake, status or social influence, and reproductive success. A recent review [74] illuminates the ways in which social factors shape health and survival in humans and other social mammals. Both theoretical and empirical work implicates income inequality (measured by the Gini index) as fostering low levels of trust and high levels of violence and mortality, even holding average income constant in humans [75–78]. In non-human animals, biologists often measure inequality in terms of hierarchy strength, which influences an individual's priority of access to resources that contribute to variation in reproductive success and survival [5–7]. These measures allow for comparisons among societal structures to help identify which ecological conditions and historical factors contribute to more or less equal societies.

The association between hierarchy and health is evident for many social mammals, from primates [79] and carnivores [80] to ground squirrels [81]. In human societies, this pattern is well documented for modern, large-scale societies [25,82]. For small-scale societies, the evidence is mixed (cf. [83,84]), although those subject to colonial and racist regimes clearly suffer from huge inequalities in health care access and outcomes [85,86].

Differences in both material and relational wealth impact social influence, although effects can clearly flow in both directions [21,32]. Effects of unequal wealth and power according to gender can be quite complex in both humans [27,28] and other species [20,87,88]. The uniquely developed degree of paternal investment and kinship reckoning in humans noted above creates its own set of variations involving matrilineal versus patrilineal inheritance of wealth and social status.

Reproductive success, closely related as it is to fitness, is of obvious significance in evolutionary analyses. While much variation in reproductive success can be due to individual circumstances, some of it certainly falls within the socially structured variation we define as inequality [89]. The varied forms and dynamics this can take are amply covered in various papers in this issue [7,11,13,20,21,31,32].

A comparative approach has the potential to reveal factors favouring or countering inequality across social mammals, as well as patterned consequences of inequality. The documentation and analysis of variation in inequality across multiple species by no means portrays inequality as invariable or inevitable. To the contrary, such research demonstrates the complexity of social dynamics, and their effects on wealth distributions in a range of ecological circumstances.

(e) . Social and political implications

Various critics have argued that sharing concepts between biology and social sciences (in either direction) ‘naturalizes’ phenomena such as inequality, hierarchy and gender roles—and in so doing makes them seem inevitable, thus reinforcing the oppressive status quo [90,91]—or otherwise conceals socially constructed aspects of inequalities [92,93]. To this we offer two responses. First, something being ‘socially constructed’ does not entail that there is no role for ecological or evolutionary factors (or does so only in extreme versions of social constructionism, a form of Cartesian dualism we reject). Second, the kinds of social or behavioural phenomena examined in this issue are not like eye colour or blood type, but phenotypically plastic traits, and in many cases conditional strategies [49] that help to adapt behaviour to current context. In such cases, the evolved feature is not the behaviour or other phenotypic expression, which can change rapidly and dramatically, but the underlying strategy or reaction norm [94–96].

More moderate critiques might hold that evolutionary analyses of human behaviour may have some scientific validity but are too easily distorted by others to justify or reinforce existing oppression. In effect, they propose that the costs (in potential societal harm) outweigh the benefits (in scientific insight and applied potential). Although we see some merit in this position, we feel it should only stand in cases where the insights have a weak basis, and the potential harm is significant and highly probable. Furthermore, ceding evolutionary analysis to those who valorize status quo inequalities is unwise; pretending there is no evolutionary or ecological basis to inequality in cases where evidence clearly supports such inference is intellectually dishonest, and can potentially strengthen regressive agendas. Indeed, if we wish to identify ways to reduce inequality—whether based on class, gender, race, or some other attribute—we must first understand the underlying causes, which evolutionary ecology is primed to contribute to. It is our sincere hope that the body of work set forth in this theme issue will help to elucidate the mechanisms contributing to wealth disparities to offer new insights for mitigating their harmful effects.

The view taken by most papers in this issue is that enduring, systematic differences in wealth and power arise out of long-term socioecological dynamics, including competition, resource transfers within and between generations, and collective action, as well as chance events. This view is closer to historical materialism (the theory of social change developed by Marx & Engels [97] and Cohen [98]) than to any form of social Darwinism or genetic determinism. Instead, our focus is on the ecological circumstances that favour or resist inequality, and how these processes can accumulate over time in human and non-human societies. This approach does not deny agency, but rather places goals and preferences—and constraints on those goals and preferences—within a complex framework that is ultimately subject to evolutionary analysis, whether biological or cultural [99]. In sum, analysing the causes and consequences of inequality (or any other phenomenon) does not entail justifying these as right or inevitable. To the contrary, deeper understanding is often necessary to mitigate or eliminate them.

3. Conclusion and prospects

In this issue, various research projects analyse how multifaceted environmental and social dynamics interact to allow or discourage the emergence of inequality in wealth, power and well-being. Further progress in disentangling drivers of inequality as well as its diverse effects will require both theoretical advances (e.g. [30]) and increasingly sophisticated empirical research that integrates data from multiple disciplines [100–102]. Although structural inequality is widespread in social species, the research reported in this issue demonstrates that it would be a mistake to view it as an inevitable or invariable outcome of reproductive competition or natural selection more generally—a point developed further elsewhere in this issue [7].

There is no question that research in both biology and evolutionary social science can be repurposed to support conservative or regressive views. White nationalists and neo-Nazis, for example, sometimes cite genetic research or Darwinian theory to advance their racist and xenophobic agendas [103,104]. However, this argument cuts both ways, as behavioural biology and evolution can be used to support progressive arguments [105–107]. Additionally, regressive political views can find comfort in claiming human exemption from biological evolution [108,109]. Be that as it may, we agree with those who hold that progressive politics can be quite compatible with efforts to use evolutionary and ecological concepts to understand human behavioural variation [110,111]. Evolutionary social scientists frequently contribute substantive critiques of racism, sexism, ethnocentrism, and other oppressive ideologies and practices [87,112,113], and empirical evidence refutes the claim that they are more likely to hold regressive views [114,115].

We acknowledge the ways in which unconscious bias and positionality can affect our research, and the potential for others to wrongfully co-opt such research for their own purposes. However, we argue it would be a mistake to abandon such research out of these concerns. Indeed, failing to understand the underlying drivers of inequality, as well as mechanisms that counter it, might well trap us in a position where we can do little to reduce it. To that end, contributions in this special issue highlight factors that influence (in)equality across mammalian societies, advancing our understanding of its causes and consequences that are common as well as unique. Our hope is that this helps advance a unifying evolutionary ecological framework regarding (in)equality.

Acknowledgements

We thank Stotra Chakrabarti, Paul Hooper and Daniel Nettle for their formative comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript, and Madison Mueller for her assistance with the references associated with this article. We are also grateful for early conversations with Christopher Schell and Ambika Kamath that helped us shape this project.

Authors’ profiles and positionality statements

As co-editors of this special issue, we recognize the sensitive and inherently political aspects of research on inequality. We also recognize that research by members of communities subject to the worst effects of social and economic inequality is underrepresented in our disciplines, and in this issue. We support efforts to rectify this historically-rooted exclusion, which we believe will only enhance the scientific as well as social benefits of research on inequality. We conclude with statements regarding the journeys that led us here.

Eric Alden Smith (he/him/his) is Professor Emeritus of Anthropology at the University of Washington, Seattle, USA. He received his PhD in Anthropology at Cornell University in 1980, which included training in behavioural ecology (Stephen Emlen and Ruth Buskirk) and held an NSF postdoc at University of Washington under Gordon Orians. Eric is an ecological and evolutionary anthropologist with research interests in hunter–gatherers, socioecological adaptation and political economy, and he has conducted fieldwork on foraging economies and demography in the Canadian Arctic, Torres Strait and Western Australia. Although a white male with its attendant privileges, he was born into a multiracial family and an anti-racist milieu and has participated in progressive politics on and off campus, all of which has informed his focus on the causes and consequences of inequality for much of his career.

Eric Alden Smith (he/him/his) is Professor Emeritus of Anthropology at the University of Washington, Seattle, USA. He received his PhD in Anthropology at Cornell University in 1980, which included training in behavioural ecology (Stephen Emlen and Ruth Buskirk) and held an NSF postdoc at University of Washington under Gordon Orians. Eric is an ecological and evolutionary anthropologist with research interests in hunter–gatherers, socioecological adaptation and political economy, and he has conducted fieldwork on foraging economies and demography in the Canadian Arctic, Torres Strait and Western Australia. Although a white male with its attendant privileges, he was born into a multiracial family and an anti-racist milieu and has participated in progressive politics on and off campus, all of which has informed his focus on the causes and consequences of inequality for much of his career.

Jennifer Elaine Smith (she/her/hers) is an Assistant Professor of Biology at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire. She studies the evolutionary ecology of social mammals using long-term data on free-living animals and comparative approaches. She received a joint PhD in Zoology and Ecology, Evolutionary Biology and Behavior from the Michigan State University focused on patterns of cooperation in female-dominated societies of spotted hyenas and was a postdoctoral fellow at the University of California Los Angeles. For the past decade, Smith served as an Associate Professor and Chair of Biology at Mills College in urban Oakland, California prior to its closure as an independent Hispanic-serving college for women and non-binary students with a mission for promoting racial and gender justice. Smith is a first-generation PhD from a family with limited financial means in rural Maine and has a hidden intellectual disability. She recognizes her privilege as an able-bodied white woman, and is strongly committed to promoting equity, diversity and inclusion. She considers herself a work in progress, and sincerely hopes this special issue will contribute to inclusive conversations, elevate diverse voices and promote positive change.

Jennifer Elaine Smith (she/her/hers) is an Assistant Professor of Biology at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire. She studies the evolutionary ecology of social mammals using long-term data on free-living animals and comparative approaches. She received a joint PhD in Zoology and Ecology, Evolutionary Biology and Behavior from the Michigan State University focused on patterns of cooperation in female-dominated societies of spotted hyenas and was a postdoctoral fellow at the University of California Los Angeles. For the past decade, Smith served as an Associate Professor and Chair of Biology at Mills College in urban Oakland, California prior to its closure as an independent Hispanic-serving college for women and non-binary students with a mission for promoting racial and gender justice. Smith is a first-generation PhD from a family with limited financial means in rural Maine and has a hidden intellectual disability. She recognizes her privilege as an able-bodied white woman, and is strongly committed to promoting equity, diversity and inclusion. She considers herself a work in progress, and sincerely hopes this special issue will contribute to inclusive conversations, elevate diverse voices and promote positive change.

Brian F. Codding (he/him/his) is Professor of Anthropology at the University of Utah, USA. He received his PhD and masters in Anthropology from Stanford University, and his bachelor's degree in interdisciplinary social science from Cal Poly San Luis Obispo. His work examines variation in past and present human behaviour through the lens of evolutionary ecology in order to understand complex socioenvironmental dynamics and issues of environmental justice. As a white, able-bodied, cis-gendered male, he recognizes his privilege. Raised by a single mother following the death of his father, he is a first-generation graduate degree earner with learning disabilities. He is committed to lowering barriers for students and scholars from underrepresented backgrounds, and to increasing access for all individuals regardless of status or ability. While his interest in this topic began mostly as academic, his research increasingly examines inequality in order to identify factors that may help reduce or eliminate it, to which he hopes this special issue will contribute.

Brian F. Codding (he/him/his) is Professor of Anthropology at the University of Utah, USA. He received his PhD and masters in Anthropology from Stanford University, and his bachelor's degree in interdisciplinary social science from Cal Poly San Luis Obispo. His work examines variation in past and present human behaviour through the lens of evolutionary ecology in order to understand complex socioenvironmental dynamics and issues of environmental justice. As a white, able-bodied, cis-gendered male, he recognizes his privilege. Raised by a single mother following the death of his father, he is a first-generation graduate degree earner with learning disabilities. He is committed to lowering barriers for students and scholars from underrepresented backgrounds, and to increasing access for all individuals regardless of status or ability. While his interest in this topic began mostly as academic, his research increasingly examines inequality in order to identify factors that may help reduce or eliminate it, to which he hopes this special issue will contribute.

Data accessibility

This article has no additional data.

Authors' contributions

E.A.S. and J.E.S.: conceptualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; B.F.C.: conceptualization, writing—review and editing.

All authors gave final approval for publication and agreed to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Conflict of interest declaration

This theme issue was put together by the Guest Editor team under supervision from the journal's Editorial staff, following the Royal Society's ethical codes and best-practice guidelines. The Guest Editor team invited contributions and handled the review process. Individual Guest Editors were not involved in assessing papers where they had a personal, professional or financial conflict of interest with the authors or the research described. Independent reviewers assessed all papers. Invitation to contribute did not guarantee inclusion.

Funding

This work was supported by a Student-Faculty Research Collaboration Grant from the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire to Madison Mueller and J.E.S.

References

- 1.Drews C. 1993. The concept and definition of dominance in animal behaviour. Behaviour 125, 283-313. ( 10.1163/156853993X00290) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hager R, Jones C. 2009. Reproductive skew in vertebrates: proximate and ultimate causes. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hobson EA. 2022. Quantifying the dynamics of nearly 100 years of dominance hierarchy research. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 377, 20200433. ( 10.1098/rstb.2020.0433) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borgerhoff Mulder M, et al. 2009. Intergenerational wealth transmission and the dynamics of inequality in small-scale societies. Science 326, 682-688. ( 10.1126/science.1178336) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith JE, Natterson-Horowitz B, Alfaro ME. 2022. The nature of privilege: Intergenerational wealth in animal societies. Behav. Ecol. 33, 1-6. ( 10.1093/beheco/arab137) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strauss ED, Shizuka D. 2022. The ecology of wealth inequality in animal societies. Proc. R. Soc. B 289, 20220500. ( 10.1098/rspb.2022.0500) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith JE, Natterson-Horowitz B, Mueller MM, Alfaro ME. 2023. Mechanisms of equality and inequality in mammalian societies. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 378, 20220307. ( 10.1098/rstb.2022.0307) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vehrencamp SL. 1983. A model for the evolution of despotic versus egalitarian societies. Anim. Behav. 31, 667-682. ( 10.1016/S0003-3472(83)80222-X) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mattison SM, Smith EA, Shenk MK, Cochrane EE. 2016. The evolution of inequality. Evol. Anthropol. Issues News Rev. 25, 184-199. ( 10.1002/evan.21491) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson KM, Cole KE, Codding BF. 2023. Identifying key socioecological factors influencing the expression of egalitarianism and inequality among foragers. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 378, 20220311. ( 10.1098/rstb.2022.0311) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bowles S, Hammerstein P. 2023. A biological employment model of reproductive inequality. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 378, 20220289. ( 10.1098/rstb.2022.0289) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hooper PL, Reynolds AZ, Jamsranjav B, Clark JK, Ziker JP, Crabtree SA. 2023. Inheritance and inequality among nomads of South Siberia. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 378, 20220297. ( 10.1098/rstb.2022.0297) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kohler TA, Bird D, Bocinsky RK, Reese K, Gillreath-Brown AD. 2023. Wealth inequality in the prehispanic northern US Southwest: from Malthus to Tyche. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 378, 20220298. ( 10.1098/rstb.2022.0298) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prentiss AM, Foor TA, Hampton A, Walsh MJ, Denis M, Edwards A. 2023. Emergence of persistent institutionalized inequality at the Bridge River site, British Columbia: the roles of managerial mutualism and coercion. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 378, 20220304. ( 10.1098/rstb.2022.0304) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sachdev I, Bourhis RY. 1991. Power and status differentials in minority and majority group relations. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 21, 1-24. ( 10.1002/ejsp.2420210102) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boone J. 1992. Competition, conflict, and the development of social hierarchies. In Evolutionary ecology and human behavior (eds Smith E, Winterhalder B), pp. 301-337. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hellmann JK, Hamilton IM. 2018. Dominant and subordinate outside options alter help and eviction in a pay-to-stay negotiation model. Behav. Ecol. 29, 553-562. ( 10.1093/beheco/ary006) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dow GK, Reed CG. 2023. The economics of early inequality. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 378, 20220293. ( 10.1098/rstb.2022.0293) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perret C, Currie TE. 2023. Modelling the role of environmental circumscription in the evolution of inequality. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 378, 20220291. ( 10.1098/rstb.2022.0291) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wallace KME, Hart DW, Venter F, van Vuuren AKJ, Bennett NC.. 2023. The best of both worlds: no apparent trade-off between immunity and reproduction in two group-living African mole-rat species. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 378, 20220310. ( 10.1098/rstb.2022.0310) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mouginot M, et al. 2023. Reproductive inequality among males in the genus Pan. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 378, 20220301. ( 10.1098/rstb.2022.0301) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buston P, Reeve H, Cant M, Vehrencamp S, Emlen S. 2007. Reproductive skew and the evolution of group dissolution tactics: a synthesis of concession and restraint models. Anim. Behav. 74, 1643-1654. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2007.03.003) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Binmore K, Rubinstein A, Wolinsky A. 1986. The Nash bargaining solution in economic modelling. RAND J. Econ. 17, 176. ( 10.2307/2555382) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hooper PL, Kaplan HS, Boone JL. 2010. A theory of leadership in human cooperative groups. J. Theor. Biol. 265, 633-646. ( 10.1016/j.jtbi.2010.05.034) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carlisle JE, Maloney TN. 2023. The evolution of economic and political inequality: minding the gap. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 378, 20220290. ( 10.1098/rstb.2022.0290) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haynie HJ, et al. 2021. Pathways to social inequality. Evol. Hum. Sci. 3, e35. ( 10.1017/ehs.2021.32) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mattison SM, Mattison PM, Beheim BA, Liu R, Blumenfield T, Sum C-Y, Shenk MK, Seabright E, Alami S. 2023. Gender disparities in material and educational resources differ by kinship system. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 378, 20220299. ( 10.1098/rstb.2022.0299) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Redhead D, Maliti E, Andrews JB, Borgerhoff Mulder M. 2023. The interdependence of relational and material wealth inequality in Pemba, Zanzibar. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 378, 20220288. ( 10.1098/rstb.2022.0288) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marshall HH, et al. 2021. A veil of ignorance can promote fairness in a mammal society. Nat. Commun. 12, 1-8. ( 10.1038/s41467-021-23910-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malani A, Archie EA, Rosenbaum S. 2023. Conceptual and analytical approaches for modelling the developmental origins of inequality. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 378, 20220306. ( 10.1098/rstb.2022.0306) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vitikainen EIK, et al. 2023. The social formation of fitness: lifetime consequences of prenatal nutrition and postnatal care in a wild mammal population. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 378, 20220309. ( 10.1098/rstb.2022.0309) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strauss ED. 2023. Demographic turnover can be a leading driver of hierarchy dynamics, and social inheritance modifies its effects. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 378, 20220308. ( 10.1098/rstb.2022.0308) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Couzin ID, Krause J, Franks NR, Levin SA. 2005. Effective leadership and decision-making in animal groups on the move. Nature 433, 513-516. ( 10.1038/nature03236) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Powers ST, Perret C, Currie TE. 2023. Playing the political game: the coevolution of institutions with group size and political inequality. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 378, 20220303. ( 10.1098/rstb.2022.0303) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kamath A, Wesner AB. 2020. Animal territoriality, property and access: a collaborative exchange between animal behaviour and the social sciences. Anim. Behav. 164, 233-239. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2019.12.009) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen Zeng T, Cheng JT, Henrich J. 2022. Dominance in humans. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 377, 20200451. ( 10.1098/rstb.2020.0451) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boyd R. 2018. A different kind of animal: How culture transformed our species. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith EA. 2010. Communication and collective action: language and the evolution of human cooperation. Evol. Hum. Behav. 31, 231-245. ( 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2010.03.001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith JE, et al. 2016. Leadership in mammalian societies: emergence, distribution, power, and payoff. Trends Ecol. Evol. 31, 54-66. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2015.09.013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith JE, Swanson EM, Reed D, Holekamp KE. 2012. Evolution of cooperation among mammalian carnivores and its relevance to hominin evolution. Curr. Anthropol. 53, S436-S452. ( 10.1086/667653) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McElreath R, et al. 2008. Individual decision making and the evolutionary roots of institutions. In Better than conscious? Decision making, the human mind, and implications for institutions (eds Engel C, Singer W), pp. 325-342. Boston, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fitzhugh B. 2020. Reciprocity and asymmetry in social networks: Dependency and hierarchy in a North Pacific comparative perspective. In Social inequality before farming (ed. Moreau L), pp. 233-254. Cambridge, UK: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research University of Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strauss ED, Holekamp KE. 2019. Social alliances improve rank and fitness in convention-based societies. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 8919-8924. ( 10.1073/PNAS.1810384116) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brosnan SF, De Waal FBM. 2014. Evolution of responses to (un)fairness. Science 346, 1251776. ( 10.1126/science.1251776) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jaeggi AV, Van Schaik CP.. 2011. The evolution of food sharing in primates. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 65, 2125-2140. ( 10.1007/s00265-011-1221-3) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stevens JR, Gilby IC. 2004. A conceptual framework for nonkin food sharing: Timing and currency of benefits. Anim. Behav. 67, 603-614. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2003.04.012) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aureli F, Cords M, Van Schaik CP.. 2002. Conflict resolution following aggression in gregarious animals: a predictive framework. Anim. Behav. 64, 325-343. ( 10.1006/anbe.2002.3071) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arnold K, Aureli F. 2006. Postconflict reconciliation. In Primates in perspective (eds Bearder S, Campbell C, Fuentes A, McKinnon KC, Panger M), pp. 592-608. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith EA. 2011. Endless forms: human behavioural diversity and evolved universals. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 366, 325-332. ( 10.1098/rstb.2010.0233) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ross CT, et al. 2023. Reproductive inequality in humans and other mammals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, 2220124120. ( 10.1073/pnas.2220124120) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ratnieks FLW, Helanterä H. 2009. The evolution of extreme altruism and inequality in insect societies. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364, 3169-3179. ( 10.1098/rstb.2009.0129) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hill KR, et al. 2011. Co-residence patterns in hunter-gatherer societies show unique human social structure. Science 331, 1286-1289. ( 10.1126/science.1199071) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chapais B. 2008. Primeval kinship: How pair-bonding gave birth to human society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alger I, Hooper PL, Cox D, Stieglitz J, Kaplan HS. 2020. Paternal provisioning results from ecological change. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 10 746-10 754. ( 10.1073/pnas.1917166117) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Strauss ED, Curley JP, Shizuka D, Hobson EA. 2022. The centennial of the pecking order: current state and future prospects for the study of dominance hierarchies. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 377, 20200432. ( 10.1098/rstb.2020.0432) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bowles S. 2006. Group competition, reproductive leveling, and the evolution of human altruism. Science 314, 1569-1572. ( 10.1126/science.1134829) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.von Rueden CR. 2020. Making and unmaking egalitarianism in small-scale human societies. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 33, 167-171. ( 10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.07.037) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cashdan EA. 1980. Egalitarianism among hunters and gatherers. Am. Anthropol. 82, 116-120. ( 10.1525/aa.1980.82.1.02a00100) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hooper P, Kaplan H, Jaeggi A. 2021. Gains to cooperation drive the evolution of egalitarianism. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5, 847-856. ( 10.1038/s41562-021-01059-y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kaplan H, Gurven M, Hill K, Hurtado AM. 2005. The natural history of human food sharing and cooperation: a review and a new multi-individual approach to the negotiation of norms. In Moral sentiments and material interests: the foundations of cooperation in economic life (eds Gintis H, Bowles S, Boyd R, Fehr E), pp. 75-113. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Flannery KV, Marcus J. 2012. The creation of inequality: How our prehistoric ancestors set the stage for monarchy, slavery, and empire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sterelny K. 2021. The pleistocene social contract: culture and cooperation in human evolution. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shultziner D, Stevens T, Stevens M, Stewart BA, Hannagan RJ, Saltini-Semerari G. 2010. The causes and scope of political egalitarianism during the Last Glacial: a multi-disciplinary perspective. Biol. Philos. 25, 319-346. ( 10.1007/s10539-010-9196-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Singh M, Glowacki L. 2022. Human social organization during the Late Pleistocene: beyond the nomadic-egalitarian model. Evol. Hum. Behav. 43, 418-431. ( 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2022.07.003) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gurven M, et al. 2010. Domestication alone does not lead to inequality. Curr. Anthropol. 51, 49-64. ( 10.1086/648587) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kohler T, Smith M. 2018. Ten thousand years of inequality: the archaeology of wealth differences. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Smith M, Dennehy T, Kamp-Whittaker A, Colon E, Harkness R. 2014. Quantitative measures of wealth inequality in ancient central Mexican communities. Adv. Archaeol. Pract. 2, 311-323. ( 10.7183/2326-3768.2.4.XX) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Smith M, Chatterjee A, Huster A, Stewart S, Forest M. 2019. Apartment compounds, households, and population in the ancient city of Teotihuacan, Mexico. Anc. Mesoamerica 30, 399-418. ( 10.1017/S0956536118000573) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Arnold J, Sunell S, Nigra B, Bishop K, Jones T, Jacob B. 2016. Entrenched disbelief: complex hunter-gatherers and the case for inclusive cultural evolutionary thinking. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 23, 448-499. ( 10.1007/s10816-015-9246-y) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Smith EA, Codding BF. 2021. Ecological variation and institutionalized inequality in hunter-gatherer societies. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2016134118. ( 10.1073/pnas.2016134118) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Richerson P, Boyd R, Bettinger RL. 2001. Was agriculture impossible during the Pleistocene but mandatory during the Holocene? A climate change hypothesis. Am. Antiq. 66, 387-411. ( 10.2307/2694241) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Feinman GM, Neitzel JE. 2023. The social dynamics of settling down. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 69, 101468. ( 10.1016/j.jaa.2022.101468) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Medupe D, Roberts SG, Shenk MK, Glowacki L. 2023. Why did foraging, horticulture and pastoralism persist after the Neolithic transition? The oasis theory of agricultural intensification. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 378, 20220300. ( 10.1098/rstb.2022.0300) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Snyder-Mackler N, et al. 2020. Social determinants of health and survival in humans and other animals. Science 368, eaax9553. ( 10.1126/science.aax9553) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Elgar FJ, Aiken N. 2011. Income inequality, trust and homicide in 33 countries. Eur. J. Public Health 21, 241-246. ( 10.1093/eurpub/ckq068) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.de Courson B, Frankenhuis WE, Nettle D, van Gelder J-L.. 2023. Why is violence high and persistent in deprived communities? A formal model. Proc. R. Soc. B 290, 20222095. ( 10.1098/rspb.2022.2095) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Daly M, Wilson M, Vasdev S. 2019. Income inequality and homicide rates in Canada and the United States. Can. J. Criminol. 43, 219-236. ( 10.3138/CJCRIM.43.2.219) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Uslaner EM, Brown M. 2005. Inequality, trust, and civic engagement. Am. Polit. Res. 33, 868-894. ( 10.1177/1532673X04271903) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sapolsky RM. 2005. The influence of social hierarchy on primate health. Science 308, 648-652. ( 10.1126/science.1106477) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gicquel M, East ML, Hofer H, Benhaiem S. 2022. Early-life adversity predicts performance and fitness in a wild social carnivore. J. Anim. Ecol. 91, 2074-2086. ( 10.1111/1365-2656.13785) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Uchida K, Ng R, Vydro SA, Smith JE, Blumstein DT. 2022. The benefits of being dominant: health correlates of male social rank and age in a marmot. Curr. Zool. 68, 19-26. ( 10.1093/CZ/ZOAB034) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nettle D, Dickins TE. 2022. Why is greater income inequality associated with lower life satisfaction and poorer health? Soc. Sci. J. 59, 1-12. ( 10.1080/03623319.2022.2117888) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jaeggi AV, et al. 2021. Do wealth and inequality associate with health in a small-scale subsistence society? Elife 10, e59437. ( 10.7554/eLife.59437) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fedurek P, Lehmann J, Lacroix L, Aktipis A, Cronk L, Makambi E, Mabulla I, Berbesque J. 2023. Status does not predict stress among Hadza hunter-gatherer men. Sci. Rep. 13, 1327. ( 10.1038/s41598-023-28119-9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Elias A, Paradies Y. 2021. The costs of institutional racism and its ethical implications for healthcare. J. Bioeth. Inq. 18, 45-58. ( 10.1007/s11673-020-10073-0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Durey A, Naylor N, Slack-Smith L. 2023. Inequalities between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians seen through the lens of oral health: time to change focus. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 378, 20220294. ( 10.1098/rstb.2022.0294) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Smith JE, von Rueden CR, van Vugt M, Fichtel C, Kappeler PM.. 2021. An evolutionary explanation for the female leadership paradox. Front. Ecol. Evol. 9, 468. ( 10.3389/fevo.2021.676805) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Smith JE, Ortiz CA, Buhbe MT, van Vugt M.. 2020. Obstacles and opportunities for female leadership in mammalian societies: a comparative perspective. Leadersh. Q. 31, 101267. ( 10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.09.005) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.von Rueden CR, Jaeggi AV.. 2016. Men's status and reproductive success in 33 nonindustrial societies: effects of subsistence, marriage system, and reproductive strategy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 10 824-10 829. ( 10.1073/pnas.1606800113) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kamath A, Velocci B, Wesner A, Chen N, Formica V, Subramaniam B, Rebolleda-Gómez M. 2022. Nature, data, and power: How hegemonies shaped this special section. Am. Nat. 200, 81-88. ( 10.1086/720001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Scott JW. 1999. Gender and the politics of history. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Neves T, Pereira MJ, Nata G. 2012. One dimensional school rankings: a non-neutral device that conceals and naturalizes inequalities. Int. J. Sch. Disaffection 9, 7-22. ( 10.18546/IJSD.09.1.02) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zanoni P, Janssens M, Benschop Y, Nkomo S. 2010. Guest editorial: unpacking diversity, grasping inequality: rethinking difference through critical perspectives. Organization 17, 9-29. ( 10.1177/1350508409350344) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dingemanse NJ, Kazem AJN, Réale D, Wright J. 2010. Behavioural reaction norms: animal personality meets individual plasticity. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25, 81-89. ( 10.1016/J.TREE.2009.07.013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tomkins JL, Hazel W. 2007. The status of the conditional evolutionarily stable strategy. Trends Ecol. Evol. 22, 522-528. ( 10.1016/J.TREE.2007.09.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jaeggi A, Boose K, White F, Gurven M. 2016. Obstacles and catalysts of cooperation in humans, bonobos, and chimpanzees: behavioural reaction norms can help explain variation in sex roles, inequality, war and peace. Behaviour 153, 1015-1051. ( 10.1163/1568539X-00003347) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Marx K, Engels F. 1970. The German ideology, 1st edn. New York, NY: International Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Cohen GA. 1978. Karl Marx‘s theory of history: A defence. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Smith EA. 2013. Agency and adaptation: new perspectives in evolutionary anthropology. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 42, 103-120. ( 10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155447) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Scheffer M, van Bavel B, van de Leemput I, van Nes E.. 2017. Inequality in nature and society. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 13 154-13 157. ( 10.1073/pnas.1706412114) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Racimo F, Sikora M, Vander Linden M, Schroeder H, Lalueza-Fox C. 2020. Beyond broad strokes: sociocultural insights from the study of ancient genomes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 21, 355-366. ( 10.1038/s41576-020-0218-z) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lalueza-Fox C. 2022. Inequality: a genetic history. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Swain CM. 2002. The new white nationalism in America: its challenge to integration. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Jeynes WH. 2011. Race, racism, and Darwinism. Educ. Urban Soc. 43, 535-559. ( 10.1177/0013124510380723) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Mitman G. 1992. The state of nature: ecology, community, and American social thought. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Leonard TC. 2009. Origins of the myth of social Darwinism: the ambiguous legacy of Richard Hofstadter's Social Darwinism in American Thought. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 71, 37-51. ( 10.1016/j.jebo.2007.11.004) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Roughgarden J. 2004. Evolution‘s rainbow: diversity, gender and sexuality in nature and people. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hooper A. 2021. Denial of evolution is a form of white supremacy. Sci. Am. See www.scientificamerican.com/article/denial-of-evolution-is-a-form-of-white-supremacy. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Syropoulos S, Lifshin U, Greenberg J, Horner D, Leidner B. 2022. Bigotry and the human–animal divide: (dis)belief in human evolution and bigoted attitudes across different cultures. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 123, 1264-1292. ( 10.1037/pspi0000391) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Singer P. 2000. A darwinian left: politics, evolution and cooperation. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lindisfarne N, Neale J. 2021. All things being equal: a critique of David Graeber and David Wengrow's The Dawn of Everything. Ecologist. See https://theecologist.org/2021/dec/17/all-things-being-equal. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Panofsky A, Dasgupta K, Iturriaga N. 2021. How White nationalists mobilize genetics: from genetic ancestry and human biodiversity to counterscience and metapolitics. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 175, 387-398. ( 10.1002/ajpa.24150) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sear R. 2021. Demography and the rise, apparent fall, and resurgence of eugenics. Popul. Stud. (NY) . 75, 201-220. ( 10.1080/00324728.2021.2009013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lyle HF, Smith EA. 2012. How conservative are evolutionary anthropologists? A survey of political attitudes. Hum. Nat. 23, 306-322. ( 10.1007/s12110-012-9150-z) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Tybur JM, Miller GF, Gangestad SW. 2007. Testing the controversy: an empirical examination of adaptationists' attitudes toward politics and science. Hum. Nat. 18, 313-328. ( 10.1007/s12110-007-9024-y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This article has no additional data.