Abstract

Aging can cause attenuation in the functioning of multiple organs, and blood-brain barrier (BBB) breakdown could promote the occurrence of disorders of the central nervous system during aging. Since inflammation is considered to be an important factor underlying BBB injury during aging, vascular endothelial cell senescence serves as a critical pathological basis for the destruction of BBB integrity. In the current review, we have first introduced the concepts related to aging-induced cognitive deficit and BBB integrity damage. Thereafter, we reviewed the potential relationship between disruption of BBB integrity and cognition deficit and the role of inflammation, vascular endothelial cell senescence, and BBB injury. We have also briefly introduced the function of CREB-regulated transcription co-activator 1 (CRTC1) in cognition and aging-induced CRTC1 changes as well as the critical roles of CRTC1/cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) in regulating inflammation, endothelial cell senescence, and BBB injury. Finally, the underlying mechanisms have been summarized and we propose that CRTC1 could be a promising target to delay aging-induced cognitive deficit by protecting the integrity of BBB through promoting inhibition of inflammation-mediated endothelial cell senescence.

Keywords: CRTC1, cognition, aging, AMPK, blood-brain barrier

General introduction

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) plays a crucial role in maintaining homeostasis of the microenvironment which is essential for keeping the neural function of the central nervous system (CNS). Upon exposure to different intrinsic or extrinsic stimuli, BBB integrity is disrupted, and this is considered an early event in the pathogenesis of a variety of neurological diseases in aged patients, including acute and chronic cerebral ischemic stroke, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and Parkinson’s disease (PD). Thus, novel treatment strategies which could improve BBB integrity could prevent or delay neurological diseases in response to various stimuli. 1

Aging-induced cognitive deficit

Normal aging is associated with severe impairments in stimulus recognition. In particular, aging can impair recognition memory, which is defined as the ability to remember a previously presented item and which entails familiarity and recollection judgment. 2 Aging can damage short-term and long-term recognition memory in and mice. 3 Episodic-like memory is the memory of events which is related to specific context and content (when, what, where) and is vulnerable to both AD-like pathological conditions as well as normal ageing processes in mice. 4

Brain ageing is a complex process which is accompanied by either learning and memory impairment or cognitive deficit. Several previous studies in humans and animals have reported a clear decline in spatial memory and working memory with age. 5 For example, the results of 28 cognitively unimpaired participants showed that the younger participants performed better than the older participants in both the egocentric and allocentric spatial memory tasks. 6 In addition, spatial learning and working memory performance when measured by the Morris Water Maze (MWM) exhibited a significant decrease at 18 and 22 months of age in mice. 7 Moreover, age has been reported to impair learning and working memory in the common marmoset. 8 Memory impairment is closely associated with the risk of post-stroke dementia which rarely occurs alone and it is an important component of the post-stroke cognitive syndrome. 9 The decrease in stroke-related dementia in recent years may be partly attributed to limited memory loss resulting from improvements in stroke care after stroke onset. 10 Ageing can alter the cholinergic innervations and reduce acetylcholinergic tonus, therefore triggering activation of a couple of signal pathways, which can regulate excitotoxicity, Aβ toxicity, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and disturb brain neurotrophic factors. 11

Aging-associated disruption of BBB integrity

During ageing progress, several factors including aortic or arterial stiffness, autonomic disorder, neurovascular unit uncoupling, and disruption of BBB integrity can effectively determine the blood flow dynamics and local perfusion of the brain. 12 Atheromatous disease-induced blood flow retarding is a common vascular insult, which can markedly increase exponentially with age increasing and arteriolosclerosis. It is primarily characterized as a major trait of small vessel disease that initially occurs during the pathology progress of the cerebrovascular disease. For the capillary, the brain endothelium undergoes rapid changes including a reduction in the volume of cytoplasm, fewer mitochondria, loss of tight junction proteins (TJPs), and thickened basement membranes with collagenous. 12 Increasing evidence demonstrates that the incidence of cerebral microvascular disease upregulates significantly with age increasing and is related to stroke, vascular dementia, and AD. Interestingly, BBB hyperpermeability occupies the “center stage” in age-induced vascular/brain damage. 13

BBB protects the brain by selectively transporting the substances between the brain parenchyma and the blood. 14 Moreover, the brain capillary endothelium-mediated substrate transport is controlled by dynamic inputs from astrocytes, pericyte, and neurons, whose changes induced by aging can also cause major abnormalities in BBB transportation in the aged or AD brain. 15 BBB injuries are associated with several diseases, such as stroke, vascular cognition impairment, AD, PD, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated dementia, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), multiple sclerosis (MS), Huntington's disease (HD), and traumatic brain injury (TBI). 16

It is of note that upon exposure to the different various extrinsic or intrinsic stimuli, 17 BBB is disrupted and BBB impairment is considered a primary cause rather than a consequence in aging-related neurodegenerative diseases. 18 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) results have shown aging-induced loss of BBB integrity in the hippocampus. 19 The aging process has been shown to cause severe structural and functional impairments to BBB and age-associated physiological, as well as pathological changes at the BBB, have been extensively reviewed by Erdo et al. 20

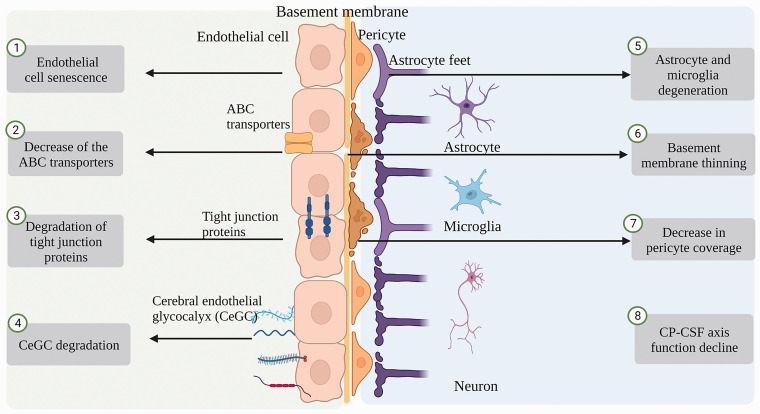

TJPs between the endothelial cells and transporters expressed on the endothelial cells constitute the key components of the BBB. The compositions of TJPs, transporter changes, brain fluid dynamics, glycocalyx, basement membrane, microglia, astrocytes, and pericyte compositions have been reported to be altered with healthy aging 21 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Aging-associated disruption of BBB integrity. Aging-induced vascular endothelial dysfunction, abnormalities in transporters expressed on endothelial cells, degradation of tight junction proteins (TJPs), degradation of brain endothelial glycocalyx (CeGC), degeneration of astrocytes and microglia, decreased pericyte coverage, thinning of basement membranes, and a decline in choroid plexus (CP)-cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) axis function.

Aging-associated changes of endothelial cells

Vascular endothelial dysfunction caused by aging plays a vital role in the development of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. 22 The aging of vascular endothelial cells can lead to BBB destruction, 22 and endothelial cell senescence is related to vascular aging-related diseases. 23 Endothelial cell senescence induced several changes in structure and function including vascular tone disorder, endothelium hyperpermeability, arterial stiffness, the deficit in angiogenesis and vascular repair, and mitochondrial biogenesis of endothelial cells decrease. 24 Interestingly, dysregulation of the cell cycle, oxidative stress, altered calcium signaling, hyperuricemia, and vascular inflammation have all been exhibited in aging-induced development and progress of endothelial cell senescence and vascular-related disease. 24

Aging-associated changes of the tight junction proteins (TJPs)

A critical factor that determines the barrier function is the density of TJPs, which is composed of claudin, occludin, and zonula occluden-1 (ZO-1). 25 TJPs facilitate low paracellular permeability of the different water-soluble substances from the blood vessel to the brain parenchyma. 26 Aging induces significant BBB alterations by changing the anatomy structure of te BBB via regulating TJPs. 27 Age-associated neurodegenerative diseases showed a marked influence on the expression of TJPs and barrier damage critically contributed to several neurological diseases. 28 Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), cyclooxygenases (Cox), and oxygen and nitrogen-produced free radicals have been reported to damage BBB during the early and delayed stages. Injury-induced upregulation of free radicals and proteases can potentially attack the cell membranes and degrade the TJPs occludin, damaging the integrity of BBB.29–31 In addition, aged NADPH oxidase 5 (NOX5) mice exhibited significantly reduced levels of both ZO-1 and occludin, thus showing the integrity disruption of BBB. 32 The age-related increase in permeability of endothelial cells derived from the human umbilical cord blood has been associated with an increase in tyrosine phosphorylation of occludin. 33 Notably, the death of endothelial cells of microvessels also is involved in BBB injury. 34 Therefore, protective strategies designed to restore the integrity of BBB should target endothelial cell death as well as TJPs degradation.

Aging-associated changes of transporter/receptor

BBB maintains the brain function in part via its low transcellular permeability. Aging-induced BBB damage has been demonstrated in the morphology and structure of the cerebral microvessels as well as in the expression and function of the transporter proteins in the luminal and basolateral surfaces of the endothelial cells in the capillary. For example, CD147, an endothelial cell specifically expressed transmembrane glycoprotein, is essential for BBB integrity and decreases with age. 35 In addition, aging has been reported to significantly decrease the number of the vesicles for receptor-mediated endocytosis and increase the caveolin number for non-specific protein transportation, 36 thereby indicating that the aging disrupted the blood-brain transport by a shift in the process of transcytosis.

ATP-binding cassette transporters (ABC transporter proteins), which can prevent the accumulation of drugs, drug couples, nucleosides, and xenobiotics in the brain require energy to transport the various molecules. 37 Age-induced expression decrease of the ABC transporters can effectively result in BBB hyperpermeability and more exposure to different xenobiotics. In AD, the clearance of Aβ can effectively decrease because of the dysfunction of P-glycoprotein (P-GP), the gene product of ATP-binding cassette, sub-family B (Abcb1). 38 Cerebrovascular P-GP at the BBB functions as an active efflux pump for several endogenous and exogenous compounds and age-induced P-GP function decline could promote the gathering of the diverse toxic substances in the brain, thus increasing aging-related venture of neurodegenerative diseases. 39 It has been reported that the expressions of Abcb1 genes and P-GP, were upregulated with age in senescence-accelerated mouse P8 (SAMP8) mice, which indicates age-related damage of BBB. 40

Aging-associated changes of glycocalyx

The abluminal side of the endothelial cells which form the BBB are coated with basement membrane (BM) and astrocyte endfeet, while the luminal side of endothelial cells is covered by glycocalyx, 41 which is consisted of the proteoglycans, glycoproteins, and glycolipids. The glycocalyx is a dynamic structure covering capillaries throughout the body and it serves as a selective barrier for large molecules. 41

The cerebral endothelial glycocalyx (CeGC) is thicker in cerebral microvessels and it is crucial in guarding the fragile parenchymal tissue. The intact glycocalyx is necessary to maintain the integrity of BBB and damage to the glycocalyx can lead to dysfunction of the BBB. 42 Degradation of CeGC occurs spontaneously with age increasing and it is one of the factors which can induce BBB hyperpermeability. Advanced age can induce lower glycocalyx thickness and damage the barrier function associated with microvascular perfusion dysfunction in both mice and humans. 43 For instance, a dramatic decrease in the volume of endothelial glycocalyx was observed in a mouse model of the endothelium-specific deficit in sirtuin 1 deacetylase activity, 44 thus suggesting that age-induced glycocalyx disruption might play a crucial role in the microvascular disorder and subsequent pathophysiological response in older adults. 45 Notably, premature degradation of CeGC has been associated with cognitive deficit induced by AD, brain edema, inflammation, cerebral malaria, and recently Covid-19. 43

Aging-associated changes of basement membrane (BM)

The basement membrane (BM) can also contribute to maintaining the integrity of BBB. 41 The thickness of the BM from 24-month-old mice was twice of the BM from 6-month-old mice. In addition, the aged BBB exhibited collection of the lipid droplets within the BM which further increased the thickness and altered its structure as the lipid-rich BM regions are located in the small pockets which are formed by the end-feet of astrocytes. Moreover, dyshomeostasis of the lipid metabolism may be ahead of the BM structural changes which favor the accumulation of the diverse abnormal proteins leading to neurodegeneration in ageing. 46

Aging-associated changes of pericytes

Pericytes, a bunch of multi-functional mural cells, are located at the abluminal side of the perivascular space in the microvessels and make a crucial contribution to stem cell-like properties acquisition, inflammatory cells trafficking, toxic waste products clearance from the brain, development, and maintenance of BBB, and modulating the neurovascular system. 47

Pericytes can control key neurovascular functions and loss of pericytes result in gradual age-dependent vascular-mediated neurodegeneration. 48 For example, in pericytes-deficient mice, age-dependent vascular damage can occur ahead of neuroinflammatory response, neurodegeneration, and memory deficit. 48 Pericytes downregulation is associated with the BBB disruption in the deep white matter in several aging-related dementias. 49 Moreover, pericyte remodeling can restore coverage of endothelial cells and vascular tone within days, and pericyte remodeling is deficient in the aged brain and contribute to impaired capillary flow and structure, 50 which is an important hallmark of aging and dementia.

Aging-associated changes of microglia and astrocytes

The diverse changes in the microglia phenotype are related to the different cellular processes including specific neurotransmitters, or immune-related receptor activation. After activation, microglia cells can release some substances, e.g., chemokines, cytokines, and reactive oxygen species. Abnormal activation of microglia during CNS injury is involved in the development and progression of neurodegenerative diseases. 51 Notably, the ketogenic diet improves cognitive function in AD by inhibiting microglia activation and neuroinflammation. 52 Aging can shift microglia morphology and microglia lost the ability to regulate the migration and clearance function, as well as the ability to shift from a pro-inflammatory to an anti-inflammatory status to modulate injury and repair. 53 Moreover, microglial depletion studies have demonstrated that microglial cells have a critical role in the vasculo-protective effect in the aged brain. 54

Astrocytes play dual roles in PD. The vitamin D-activating enzyme CYP27B1 in astrocytes have a beneficial role and astrocytes protect neurons by internalizing α-synuclein aggregates, while inflammation in astrocytes leads to deleterious effects. 55 In addition, age-induced accumulation of senescent astrocytes in the brain demonstrates a decreased functional capacity. Senescent astrocytes secret senescent-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) factors, which contribute to neuroinflammation and neurotoxicity. Moreover, age-associated BBB dysfunction causes the hyperactivation of transformation growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling in astrocytes, which can elicit a pro-inflammatory and epileptogenic phenotype. Aging-induced progressive BBB dysfunction and senescence increase which have been associated with a raised risk of neurodegenerative diseases. 56 Notably, astrocyte plasticity in mice ensures continued end-foot coverage of the cerebral blood vessels following injury and declines rapidly with age. 57

Age-induced alternation in the microglia and astrocytes can also alleviate BBB disruption. 58 Microglia cells are featured by significant alterations in the negative regulation of the protein phosphorylation and phagocytic vesicles, whereas astrocytes can show elevated enzyme or peptidase-inhibitor activity in the recovery of BBB structure and function. 58

Aging-associated changes of blood-cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-barrier/choroid plexus

The choroid plexus (CP) is a complex structure that is inside the ventricles of the brain and consists mainly of the choroid plexus epithelial (CPE) cells surrounding the fenestrated capillaries. These CPE cells form an anatomical barrier between blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), named the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier (BCSFB) . 59 The main role of the CP in the brain is to keep optimal homeostasis by secreting CSF including various nutrients, neurotrophins, and growth factors. The CP can also clear the toxic and undesirable molecules from CSF and prevent leukocytes in the brain. 59 During later stages of life, the CP-CSF axis demonstrates an obvious function decrease, including protein synthesis and CSF secretion which might increase the risk for the incidence of late-life diseases, such as normal pressure hydrocephalus and AD. 60 With age increasing, epithelial cells can effectively activate the host defense, and resident macrophages can increase the expression of the interleukin-1β (IL-1β) signaling pathway. 61 Loss of BBB and BCSFB function has been reported both in AD rodent models and human subjects. 62

Possible mechanisms underlying aging-induced disruption of BBB integrity

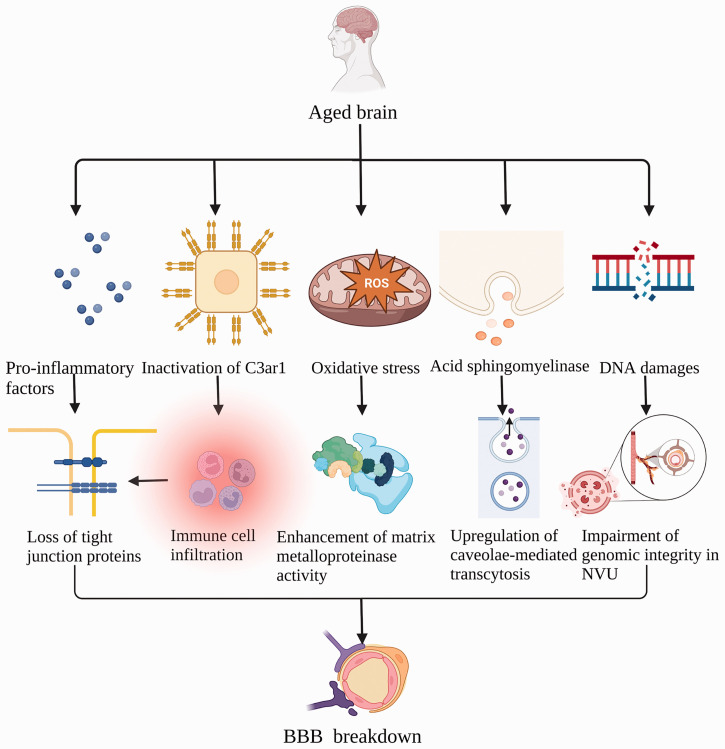

The upregulation of vasoactive mediators, astrocytes, and monocytes/macrophages activation and channel ions and surface vector expression downregulation in endothelial cells, serve as the main factors regulating the hyperpermeability of BBB. 63 Peripheral proinflammatory cytokines consisting of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukins-1β (IL-1β), and IL-6 are elevated with aging, 64 aging-associated BBB hyperpermeability might be a consequence of pro-inflammatory factors-induced loss of endothelial TJPs. 65 Aging-associated chronic low-grade inflammatory state can also affect the acute inflammatory response involved in myocardial infarction or acute ischemic stroke. 66 Moreover, the complement pathway is regarded as a well-established regulator of innate immunity in the brain. For example, complement C3 has been implicated in inflammation and ischemia/reperfusion injury, and high serum complement C3 levels at baseline are associated with increased risks of adverse clinical outcomes at 3 months after ischemic stroke. 67 Inactivation of endothelial C3ar1 can also inhibit the microglial cells and improve volumes of hippocampus and cortex in the aging brain, thus demonstrating that the endothelial C3a receptor is involved in aging-associated vascular inflammation and BBB hyperpermeability. 68

It has been reported that endothelial cells-derived acid sphingomyelinase (ASM) is critically involved in regulating BBB integrity. Elevated levels of ASM were found in the endothelium of the brain and plasma of aged humans and mice, resulting in BBB hyperpermeability through upregulating caveolae-mediated transcytosis. Moreover, ASM could damage the caveolae-cytoskeleton via protein phosphatase 1-mediated ezrin/radixin/moesin dephosphorylation in the primary mouse brain endothelial cells. 69

It is of note that aging is also accompanied by dramatic changes in sleep quality and quantity and sleep gradually become fragmented with age. 70 In healthy adults, a sleep disorder can induce inflammation. It has been established that various aspects of aging and sleep disorder can disrupt BBB by interaction via neuroimmune mechanisms. 70 In addition, recent evidence has suggested that aging-related oxidative stress, DNA damage accumulation, and DNA repair disabilities can significantly compromise the integrity of the genome in the most cell of the neurovascular unit (NVU). Thus, alleviating DNA damage or enhancing DNA repair abilities in the NVU could be a promising strategy for the management of vascular and neurodegenerative disorders.

Structural and functional alterations of vascular in various AD mouse models have revealed that a dysfunctional NVU produces a series of events that ultimately lead to reduced cerebral blood flow (CBF), increased BBB leakage, and related complications reported in AD. 71 Reduced CBF-induced NVU changes is one of the pathogenic mechanisms of vascular dementia 72 and NVU coupling is disturbed with the pathological process of PD. 73 In addition, PS1M146V mutation induced an Aβ oligomer-associated disruption of cerebrovascular function in rCBF response to diazoxide in AD mice. 74 The mechanism underlying aging-induced BBB damage has been summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Mechanisms underlying aging-induced disruption of BBB integrity. Pro-inflammatory cytokines are elevated with aging, causing loss of endothelial tight junction proteins (TJPs). Inactivation of endothelial C3ar1 promotes immune cell infiltration involved in aging-related vascular inflammation and degradation of TJPs. Endothelial cell-derived acid sphingomyelinase (ASM) leads to high BBB permeability through the upregulation of caveolin-1-mediated transcytosis. Oxidative stress associated with aging promotes the expression of matrix metalloproteinase. The accumulation of DNA damage greatly impairs genomic integrity in neurovascular units (NVU), leading to BBB disruption.

Disruption of BBB integrity and cognitive deficit

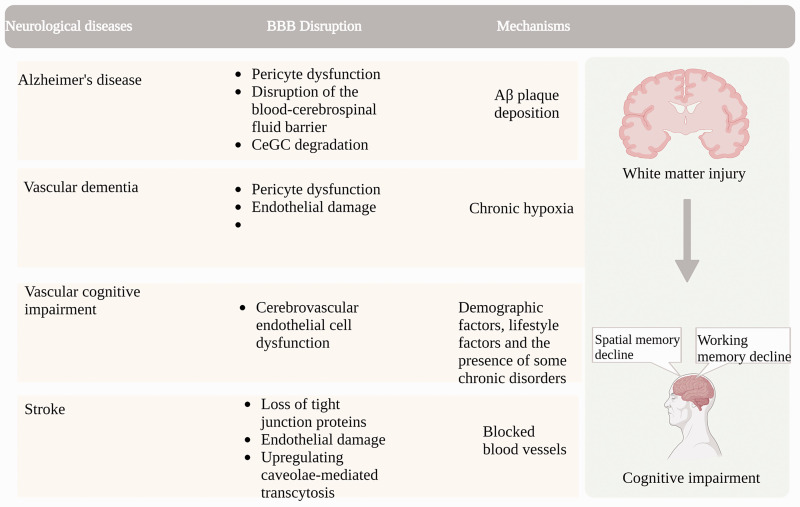

The integrity of BBB disruption is an early feature of AD that is ahead of the hallmarks of deposition of Aβ plaque and formation of neuronal neurofibrillary tangle. 75 A damaged BBB has been reported to correlate with microglial activation and reactive astrogliosis-related neuroinflammation. Increased expression of high-mobility group box protein 1 (HMGB1) and thrombin which mediate the BBB disruption can act as potential biomarkers of neuroinflammation and promote the progression of neurodegeneration in AD. 75 In addition, specific upregulation of ribosomal complexes were observed in AD and is an important manifestation of AD patients 76 and hippocampal BBB permeability is associated with APOE4 mutation, and may predict cognitive function. 77 Moreover, deprivation of E3 ubiquitin ligase Pdzrn3 prevents AD-induced alterations in Wnt target genes and enhances endothelial TJPs, and Wnt signaling may regulates BBB integrity and cognitive decline in AD. 78

Vascular dementia (VaD) is the second most common type of dementia 79 and it is usually induced by cerebrovascular disorder, during which the cerebrovascular endothelial cells (CECs) are very fragile. CEC damage occurs before the start of VaD and can finally result in the dysfunction of cerebral blood flow and BBB injury, followed by glial activation and an inflammatory microenvironment in the brain. 79

Vascular cognitive impairment (VCI) is major dementia that is caused by chronic hypoxia. Chronic hypoxia can induce progressive injury to the white matter (WM) secondary to BBB hyperpermeability and vascular functional disorder. 80 Cerebral small vessel disease (CSVD) is recognized as the leading source of VCI as it can alter the microcirculation integrity of the neurovascular unit involved in VCI. 81 Cerebrovascular structural and functional disorders can impair cognition in aged people, and improving cerebrovascular function has become an important strategy to reduce the risk of dementia 82 since vascular health is essential to protect brain structure and cognitive function in old age,83,84 Aging-induced BBB disruption and cognitive deficit are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

BBB disruption as a cause of cognitive impairment in aging-related neurodegenerative diseases. BBB disruption ahead of impaired cognition is shown in Alzheimer's disease characterized by Aβ plaque deposition, vascular dementia due to chronic hypoxia, vascular cognitive impairment due to age and lifestyle and chronic diseases, and stroke with vascular occlusion, microvascular instability-induced BBB disruption and white matter damage.

Evidence showing the disruption of BBB integrity and cognitive deficit

Age-related BBB disruption and cerebral microvascular rarefaction in mice have been previously demonstrated by longitudinal intravital two-photon microscopy and optical coherence tomography, thereby suggesting that age-related BBB injury and cerebral microvascular rarefaction can contribute significantly to the pathogenesis of both vascular cognitive impairment and dementia and AD. 85 In addition, leakage measures by MRI in healthy people showed that the neurovascular alteration could be a plausible explanation for the cognitive decline inherent to the ageing process. 86 Moreover, BBB injury is ahead of the cognitive deficit and neurodegeneration in a diabetic insulin-resistant mouse model 87 and surprisingly a connection between the cognitive deficiency and BBB disruption in the hippocampus was observed in low-density lipoprotein receptor knockout mice, which could mimic familial hypercholesterolemia. 88 In summary, BBB dysfunction could be a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of various neurodegenerative diseases.

BBB, tight junction protein, cognitive deficit

Angiogenesis is very crucial for the remodeling of neurovascular, by using the spontaneously hypertensive/stroke-prone rats with unilateral carotid artery occlusion and a Japanese permissive diet to model white matter damage, Yang et al., proposed that chronic hypoxia can disrupt TJPs, induce vascular hyperpermeability, and initiate angiogenesis in WM in a rat model of VCI. 80 In addition, deficiency of CD36, a class B scavenger receptor, alleviated stroke-induced memory deficit by preserving BBB integrity. 89 Of note, reduced levels of adropin in the brain and plasma are associated with aging and stroke and post-stroke adropin treatment significantly reduced MMP-9 and protected TJPs and improved cognitive function by reducing BBB damage. 90 Moreover, oxytocin treatment improves mice spatial memory by maintaining BBB integrity and upregulating AQP4 expression after stroke 91 and β-hydroxybutyrate has been shown to improve chronic cerebral hypoperfusion-induced memory deficit through reducing neuroinflammation and BBB impairment. 92

White matter lesions (WML) are associated with dementia and are commonly implicated in brain ageing. Albumin extravasation could be detected in the whole ageing brain and increased in WML, thus suggesting that BBB injury might play a critical role in the pathogenesis of WML although this was not along with significant changes in TJPs expression between the endothelial cells. 93

CeGC and cognitive deficit

The CeGC is relatively thicker in the cerebral microvessels, indicating specialization for the function as an important component of the BBB. 43 CeGC degradation can lead to BBB permeability increase which can occur during aging, nevertheless, CeGC degradation has been reported in multiple conditions related to cognitive deficit. 43 For example, enzymatic degradation of CeGC increases capillary stagnation and impaired microcirculatory blood flow, thus participating in the pathogenesis of subcortical vascular dementia. 94 In addition, thinning and discontinuities within the vascular BM are found to be associated with the leakage of the plasma protein prothrombin across the BBB in AD. 95

Pericyte and cognitive deficit

Loss of brain capillary pericyte has been reported to be critically contributed to the pathologies and cognitive impairment in AD and pericyte injury is involved in AD progression in an Aβ-independent pathway in the early stage. 96 Thus, promoting the recovery of pericyte function could be a key strategy to prevent and interevent early AD. 96

Pericytes dysfunction is involved in a couple of diseases that induce cognitive deficits such as CSVD, acute stroke, AD, and other neurological diseases. For example, in CSVDs, degeneration of pericytes can lead to microvessel instability and demyelination, whereas, ischemic stroke-induced pericyte constriction can cause a no-reflow phenomenon in the capillaries of the brain. A marked decrease in the pericyte coverage and subsequent microvascular damage can be observed in association with white matter impairment in AD. Moreover, pericyte loss can induce BBB breakdown, which can lower Aβ clearance and promote the extravasation of neurotoxic molecules into the brain. 47

BCSFB and cognitive deficit

Age has been established as the key risk factor for many neurodegenerative diseases. Aβ accumulation was found in both the AD brain and the normal aging brain. Thus, Aβ clearance from the brain could be done by active transport at the BBB and blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier (BCSFB). However, with age increasing, the Aβ efflux transporters and influx transporters are significantly downregulated and upregulated respectively at the BBB, thus increasing the burden of Aβ in the brain. Age-dependent changes of Aβ transporters are associated with a significant downregulation in Aβ42 accumulation in the choroid plexus (CP) and BCSFB. 97

Possible mechanisms and treatment strategy

Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) is critically involved in regulating inflammation, NVU remodeling, and cognitive recovery after stroke. Interestingly, eNOS deficit has been reported to exacerbate brain injury and cognitive impairment in bilateral common carotid artery stenosis-induced mouse models of vascular dementia. 98 In addition, NADPH oxidases (NOX) play important roles in oxidative stress-induced vascular function disorder and are involved in the pathophysiology progress of its target organs. For instance, aged NOX5 deficit mice exhibited reduced levels of TJPS, thus exhibiting an impairment of both the integrity of BBB and memory. 32 Moreover, increased vascular NOX2 and microvascular inflammatory in human subjects with cerebrovascular disease support NOX2 as a critical determinant of VCI. 99

It is of note that the perioperative neurocognitive disorder is becoming a surgery-induced common complication in older patients in the clinic. 100 Atorvastatin, a strong HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor which has been widely used in the clinic, has been shown to attenuate surgery-produced BBB injury and cognitive deficit partly by suppressing nuclear factor kappaB (NF-κB) pathway and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome activation in aged mice. 100 In addition, whole transcriptome sequencing of hippocampus of aged mice reveals genes and signaling pathways associated with neuroinflammation and BBB in different perioperative periods. 101 In addition, astrocyte connexin43 has been shown to attenuate oxidative stress and improve prolonged isoflurane anesthesia- caused cognitive impairment by inhibiting hippocampal neuroinflammation, 102 which has been characterized as a hallmark of perioperative cognitive impairment 103 anesthesia-induced cognitive impairment. 102 Galectin-1 has been shown to ameliorate cognitive dysfunction by inhibiting microglia activation-mediated neuroinflammation in old mice. 104 Of note, cholecystokinin octapeptide can attenuate postoperative cognitive impairment by inhibiting microglia activation and A1 reactive astrocytes induction in aged mice. 105 In addition, electroacupuncture improves postoperative cognitive impairment by inhibiting the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome and NF-κB in old mice. 106

Cortistatin-14 is a neuropeptide that structurally resembles somatostatin. It has been found to exert neuroprotective effects against microglial activation, BBB damage, and cognitive deficit in sepsis-induced encephalopathy which showed disabling cognitive dysfunction. 107 Moreover, omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) have been reported to maintain BBB integrity, improve cognitive function, and decrease the risk of developing dementia in aging populations. 108 Interestingly, diets rich in omega-3 PUFAs have been shown to decrease aging-associated BBB damage in different preclinical studies. 108

Inflammation, vascular endothelial cell senescence, and BBB injury

Cell senescence, which is defined as an irreversible growth arrest characterized by the acquisition of a pro-inflammatory secretory phenotype in response to DNA damage or exposure to other cellular stimuli, 109 can contribute to BBB compromise, which facilitates the brain permeability to inflammatory cytokines, leading to substantial damage of neuron and glial cells. 110 The damaged macromolecules and organelles that accumulate in cells are regarded as the “agonists” of aging in many eukaryotes and cause their viability to decline. 111 Senescent cells accumulate in diverse organs, alter the microenvironment, and impair tissue repair/renewal by secreting a bunch of MMPs and inflammatory cytokines. The type of cells is regarded as the secretory phenotype of senescence-related. 111

Endothelial cell (EC) senescence, which has been associated with vascular aging-related diseases, 23 is a pathophysiological process of structural and functional changes including arterial stiffness, endothelium hyperpermeability, impaired vascular tone, a deficit in angiogenesis and vascular repair, and a marked decrease of endothelial cells mitochondrial biogenesis. 24 In addition, dysregulation of the cell cycle, oxidative stress, altered calcium signaling, hyperuricemia, and vascular inflammation have been reported to play critical roles in the development and progress of endothelial cell senescence and aging-related vascular disease. 24 EC senescence can increase traction forces by promoting the various age-accompanied changes in the glycocalyx and sirtuin1 (SIRT1). Aging downregulated the expression of SIRT1 and SIRT1 activation can decrease the traction forces and upregulate the peripheral actin in aged ECs, thus suggesting that EC senescence can augment the traction forces and alter actin localization through driving changes of the glycocalyx and SIRT1. 112 Vascular endothelial dysfunction caused by aging plays a vital role in the development of several cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases 22 and vascular endothelial cell senescence can lead to the destruction of BBB integrity 111 and BBB dysfunction associated with aging can cause the development of cerebrovascular disease and exacerbate neuronal damage. 111

Peripheral inflammation can destroy the BBB through various pathways, leading to different CNS disorders. 113 Age-associated changes have been reported in the immune system and can alter the BBB functions. 114 Vascular inflammation, peripheral lymphocyte infiltration, and BBB hyperpermeability have been associated with increasing age. 68 Moreover, BBB disruption, neuroinflammation, and cognitive deficit have been reported in nondemented elders. 115 Inflammatory-related mechanisms, including neutrophil migration, cell adhesion, lipid metabolism, and angiogenesis have been reported. 115 For example, endothelial function restoration reverses BBB disruption and reduces neuroinflammation in a model of VCI. 116 Moreover, the functional loss of BBB has been demonstrated to play a pivotal role in vascular injury-induced neurodegenerative disorders such as AD. 117 Aging-induced gradual worsening of the function of capillary concomitant with increased neuroinflammation. 117 BBB dysfunction developed during normal aging has been reported to be associated with inflammation caused by the inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α and IL-1β and loss of TJPs, but not with leukocyte recruitment. 117 Notably, small extracellular vesicles obtained from mesenchymal stromal cells were shown to induce neuroprotection in mice by modulating the brain infiltration of leukocytes in mice. 118 The staging of the inflammatory cascade response to different cerebrovascular disease states may be critical for the development and implementation of anti-inflammatory strategies.119,120

Role of CRTC1 in cognition and aging-induced CRTC1 changes

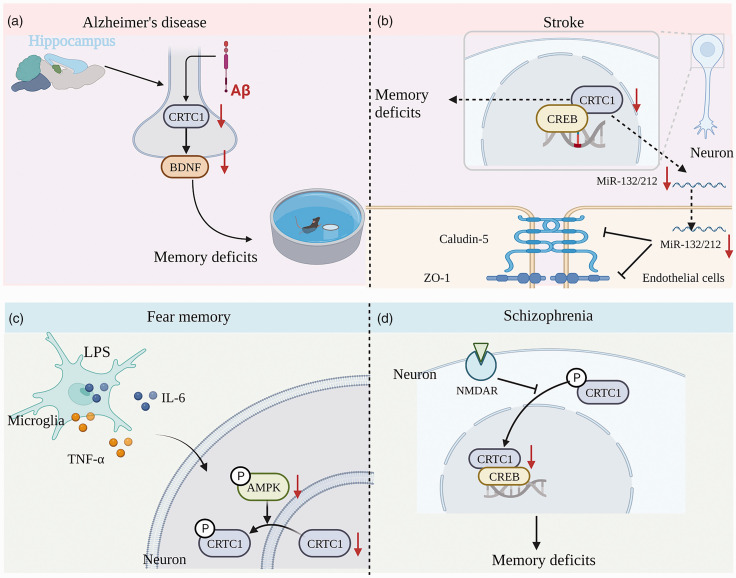

CRTCs, which is required for maintaining both energy balance and fertility and controls systemic mitochondrial metabolism and longevity, is the first CREB coactivator that has been found to increase CREB activity. 121 Interestingly, the neuronal activity has been reported to recruit the CRTC1/CREB to promote transcription-dependent autophagy to maintain late-phase long-term depression 122 and synapse to nuclear signaling-induced excitation-transcription coupling has been shown to trigger autophagy for long-lasting synaptic depression. 123 It is noteworthy that CRTC1 has been reported to critically contribute to regulating depression, 124 AD, 125 fear memory, 126 stroke-induced memory impairment, 127 LPS-induced fear memory impairment, 128 and schizophrenia-induced memory impairment. 129

CRTC1 is necessary for the induction of ischemic tolerance 130 and can play pivotal roles in SIK2-mediated neuron survival after ischemia. 131 The function of CRTC1 can be affected if CRTC1 is phosphorylated after ischemia. 131 Oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD) can induce phosphorylation of CRTC1 (p-CRTC1) which is localized in the cytoplasm. Reoxygenation can quickly promote the dephosphorylation and translocation of p-CRTC1. OGD-induced degradation of the salt-inducible kinase 2 (SIK2) protein accompanied by CRTC1 dephosphorylation, followed by the transcription activation of the downstream target genes. 131 Our recent study assessed the role of CRTC1 expression in stroke-induced memory impairment. We observed that acute ischemic stroke (AIS) can induce a significant decrease of CRTC1, fluorocitrate (FC) treatment which could suppress the reactive astrocytes can significantly inhibit this decrease, thereby indicating that inhibition of reactive astrocytes with FC treatment can ameliorate AIS-induced memory deficit by increasing CRTC1 expression in rats. 127

In addition, previous studies have shown that the function of CRTCs is not limited to the level of transcriptional regulation, and abnormalities in CRTCs may be closely related to organ aging and human age-related diseases. 132 CRTC1 dysregulation acts as a new driver of aging that can potentially link aging to disease. 132 CRTCs are deregulated in aging and can increase aging-related disease risk. 132 For example, Aβ can disrupt activity-dependent gene transcription required for memory through the CRTC1. 133 Our recent study also showed that impaired CRTC1-BDNF signaling pathways in the hippocampus are involved in the Aβ-induced deficit of long-term memory and synaptic plasticity 134 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

CRTC1 plays a critical role in cognitive impairment-related diseases. (a) In an Aβ rat model of AD, intra-neuronal Aβ disrupts hippocampal CRTC1-dependent gene expression and cognitive function. (b) Role of CRTC1 expression in stroke-induced memory impairment. CRTC1 deficiency leads to reduced miRNA-132/212 expression and increased BBB permeability in the mouse brain after ischemic stroke. (c) AMPK inactivation-induced CRTC1 downregulation mediates LPS-induced fear memory impairment and (d) CRTC1 expression downregulation in the prefrontal cortex is involved in schizophrenia-induced memory deficits.

Mechanisms underlying CRTC1’s effect and the factors that could regulate CRTC1

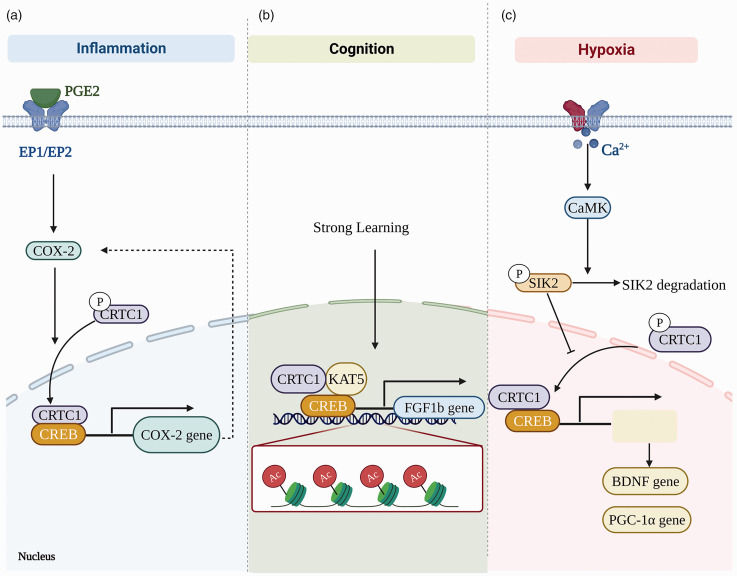

The mechanism underlying CRTC1’s effect and the factors that could regulate CRTC1 are summarized in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Mechanisms underlying CRTC1’s effect and the factors that could regulate CRTC1. (a) PGE2 promotes dephosphorylation and nuclear entry of CRTC1 through E prostaglandin (EP1 and EP2) receptor signaling, and CRTC1 plays an important role in aging-associated endothelial cell dysfunction by affecting inflammation via targeting COX-2. (b) CRTC1-mediated substitution of histone acetyltransferase KAT5 for CREB-binding protein (CBP) on the fibroblast growth factor (Fgf1b) promoter enhances memory and (c) In chronic hypoxia, calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMK) leads to the degradation of salt-inducible kinase 2 (SIK2), resulting in the translocation of CRTC1 from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, and rendering neurons resistant to subsequent effects.

The CRTC1/COX2 in inflammation and endothelial cell senescence

Inflammation is considered to be an important causative factor of BBB injury during aging. 117 It has been reported that the expression of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) increases with the aging process, and part of the increase in COX-2 expression could be attributed to the dietary molecules-induced reactive oxygen series (ROS), chemical reactions, and physical shearing. COX-2 plays important role in endothelial cell dysfunction associated with aging. 135 Perivascular macrophages produce prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) through COX-2 136 and the increase of COX-2-derived PGE2 caused by ischemia can lead to BBB damage. 137 CRTC1 is a novel mediator of the PGE2 signaling pathway 138 and PGE2 can promote the dephosphorylation and nuclear entry of CRTC1 through E prostanoid (EP1) and EP2 receptor signaling, thus resulting in enhanced transcriptional activity of CRTC1. 138 Interestingly, treatment with SC-51089, the EP1 receptor antagonist, or EP1 gene deletion can lead to short-term focal cerebral ischemia after BBB destruction and hemorrhagic transformation was significantly reduced. 137 CRTC1 has been reported to affect inflammation by targeting COX-2. 139 For example, COX-2 inhibitors can reduce the level of active nuclear CRTC1 in mouse colon tumors. 138 However, fewer studies do not support this conclusion. For example, cerebral arterioles responses were explored in adult (6–8 mo old) and aged (22-24 mo old) rats and impaired vasodilatation of cerebral arterioles in aged rats did not appear to be related to the production of a cyclooxygenase constrictor substance. 140 We also have recently reported that the decreased CRTC1 level in the hippocampus could be potentially involved in depression-like behavior in a stress-induced animal model. Inflammation-related factors including Lysozyme (Lyz2), G-Protein-Coupled Receptor 84 (Gpr84), intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (Icam1), and Toll-like receptor 2 (Tlr2) were found to be markedly increased in the rat hippocampus in depression animal model. 124

Role of CRTC1 in the interaction between neurons and endothelial cells as well as in the process of the cognitive deficit

CRTC1 deletion has been reported to lead to the decrease of miRNA-132/212 expression in the mice brain after ischemic stroke, significantly increase infarct volume, and can exacerbate BBB damage accompanied by aggravating neurological function disorder. In addition, the co-culture of endothelial cells with CRTC1-deficient neurons could augment the cell vulnerability to hypoxia, thus suggesting that the miRNA-132/212 cluster could be primarily regulated by CRTC1 and plays a key role in the alleviation of ischemic damage. 141 In addition, our recent study showed that CRTC1-mediated neuronal loss can effectively contribute to acute ischemia and reperfusion-damaged BBB integrity, and modulation of α7nAchR by melatonin could reduce the BBB damage by promoting upregulation of CRTC1. 142

CRTC1 regulation by AMPK and aging-induced AMPK change

Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling pathway can coordinate several physiological processes including that cellular growth, autophagy, and metabolism. 143 AMPK is involved in energy production and metabolism. AMPK can be activated by low energy levels, has the effect of prolonging life, and can serve as a potential target for drugs. In addition, the activation of AMPK can regulate a variety of longevity pathways to promote health and delay aging. 144

Aging has been reported to affect the activation of AMPK, 144 which is a heterotrimeric serine/threonine protein kinase and is critically involved in regulating energy balance, life span extension, and memory. 145 For example, AMPK agonist AICAR can improve cognition in both young and aged mice 145 and metformin treatment could inhibit Aβ accumulation and memory deficit in APP/PS1 mice. 146 Interestingly, pharmacological enhancement of AMPK activity can also significantly improve traumatic brain injury-induced cognitive impairment. 147 Inactivation of AMPK has been reported to be involved in LPS-induced BBB damage in aged mice. 148 In addition, trans-10-hydroxy-2-decenoic acid can alleviate LPS-induced BBB dysfunction by activating the AMPK. 149 In addition, activation of AMPK by metformin could effectively alleviate LPS-induced memory impairment through upregulating CRTC1. 128

CRTC1 is regulated by FGF 1

CRTC1-mediated substitution of the histone acetyltransferase KAT5 for CREB-binding protein (CBP) on the fibroblast growth factor (Fgf1b) promoter can enhance memory. 126 Learning-induced CRTC1 nuclear translocation could modulate the strength of memory by the exchange of chromatin remodeling complexes on the fibroblast growth factor (Fgf1) gene. 126

CRTC1 gene is methylated in the human hippocampus in AD

It has been reported that the methylation level of the CRTC1 gene is markedly lower in AD cases within both promoter regions (Prom1 and Prom2). Interestingly, the methylation level of CRTC1 was inversely correlated with AD-related neuropathological changes, particularly with p-tau deposition. Moreover, a marked downregulation of CRTC1 mRNA level was found in the hippocampus of AD, thereby supporting that CRTC1 was decreased in the hippocampus of AD. 150

Conclusion

The integrity of BBB damage plays a critical role in regulating aging-induced cognitive deficit. BBB dysfunction can serve as a potential therapeutic target for various neurodegenerative disorders. CRTC1/COX2 is important in modulating inflammation and endothelial cell senescence. Thus, CRTC1 is a potential target to delay aging-induced cognitive deficit by protecting the integrity of BBB by inhibiting inflammation-mediated endothelial cell senescence.

Abbreviations

AD, Alzheimer's disease; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; BBB, blood-brain barrier; ASM, acid sphingomyelinase; BM, basement membrane; BCSFB, blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier; CaMK, calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase; CBF, cerebral blood flow; CBP, CREB-binding protein; CeGC, cerebral endothelial glycocalyx; CNS, central nervous system; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; CP, choroid plexus; CREB-regulated transcription co-activator 1; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CRTC1, CSVD, cerebral small vessel disease; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; EP1, E prostanoid; FC, Fluorocitrate; Fgf1, fibroblast growth factor; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; LTP, long term potentiation; MMP-9, matrix metalloproteinase-9; NOX, NADPH oxidases; NVU, neurovascular units; OGD, oxygen-glucose deprivation; PD, Parkinson's disease; PGE2, prostaglandins 2; P-GP, P-glycoprotein; SIK2, salt-inducible kinase 2; TJPs, tight junction proteins; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; VaD, vascular dementia; VCI, vascular cognitive impairment; WM, white matter; ZO-1, zonula occludens-1.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFC3602805). This work was also supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81870973, 81671145), by the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LY23H090003), by Ningbo science and technology plan project (2022S021), by Jiaxing Plan of Science and Technology (2022AY30028).

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ contributions

YW, WD, YS drafted the manuscript, WD, YS drafted the figures. JZ prepared the reference. JZ, CM, XJ revised the manuscript. All authors agreed on the final draft.

References

- 1.Liu WC, Wang X, Zhang X, et al. Melatonin supplementation, a strategy to prevent neurological diseases through maintaining integrity of blood brain barrier in old people. Front Aging Neurosci 2017; 9: 165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burke SN, Wallace JL, Nematollahi S, et al. Pattern separation deficits may contribute to age-associated recognition impairments. Behav Neurosci 2010; 124: 559–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diaz A, Trevino S, Vazquez-Roque R, et al. The aminoestrogen prolame increases recognition memory and hippocampal neuronal spine density in aged mice. Synapse 2017; 71: e21987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis KE, Eacott MJ, Easton A, et al. Episodic-like memory is sensitive to both Alzheimer's-like pathological accumulation and normal ageing processes in mice. Behav Brain Res 2013; 254: 73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang M, Gamo NJ, Yang Y, et al. Neuronal basis of age-related working memory decline. Nature 2011; 476: 210–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernandez-Baizan C, Diaz-Caceres E, Arias JL, et al. Egocentric and allocentric spatial memory in healthy aging: performance on real-world tasks. Braz J Med Biol Res 2019; 52: e8041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shukitt-Hale B, Mouzakis G, Joseph JA.Psychomotor and spatial memory performance in aging male Fischer 344 rats. Exp Gerontol 1998; 33: 615–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glavis-Bloom C, Vanderlip CR, Reynolds JH.Age-related learning and working memory impairment in the common marmoset. J Neurosci 2022; 42: 8870–8880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Sullivan MJ, Li X, Galligan D, et al. Cognitive recovery after stroke: memory. Stroke 2023; 54: 44–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eng CW, Mayeda ER, Gilsanz P, et al. Temporal trends in stroke-related memory change: results from a US national cohort 1998-2016. Stroke 2021; 52: 1702–1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Majdi A, Kamari F, Vafaee MS, et al. Revisiting nicotine's role in the ageing brain and cognitive impairment. Rev Neurosci 2017; 28: 767–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalaria RN, Hase Y.Neurovascular ageing and age-related diseases. Subcell Biochem 2019; 91: 477–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stamatovic SM, Martinez-Revollar G, Hu A, et al. Decline in sirtuin-1 expression and activity plays a critical role in blood-brain barrier permeability in aging. Neurobiol Dis 2019; 126: 105–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin X, Liu J, Liu W.Early ischemic blood brain barrier damage: a potential indicator for hemorrhagic transformation following tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) thrombolysis? Curr Neurovasc Res 2014; 11: 254–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pardridge WM.Does the brain's gatekeeper falter in aging? Neurobiol Aging 1988; 9: 44–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenberg GA.Neurological diseases in relation to the blood-brain barrier. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2012; 32: 1139–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weiss N, Miller F, Cazaubon S, et al. The blood-brain barrier in brain homeostasis and neurological diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta 2009; 1788: 842–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cai W, Zhang K, Li P, et al. Dysfunction of the neurovascular unit in ischemic stroke and neurodegenerative diseases: an aging effect. Ageing Res Rev 2017; 34: 77–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montagne A, Barnes SR, Sweeney MD, et al. Blood-brain barrier breakdown in the aging human hippocampus. Neuron 2015; 85: 296–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erdő F, Denes L, de Lange E.Age-associated physiological and pathological changes at the blood-brain barrier: a review. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2017; 37: 4–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banks WA, Reed MJ, Logsdon AF, et al. Healthy aging and the blood-brain barrier. Nat Aging 2021; 1: 243–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donato AJ, Morgan RG, Walker AE, et al. Cellular and molecular biology of aging endothelial cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2015; 89: 122–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tian XL, Li Y.Endothelial cell senescence and age-related vascular diseases. J Genet Genomics 2014; 41: 485–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jia G, Aroor AR, Jia C, et al. Endothelial cell senescence in aging-related vascular dysfunction. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2019; 1865: 1802–1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hawkins BT, Davis TP.The blood-brain barrier/neurovascular unit in health and disease. Pharmacol Rev 2005; 57: 173–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stamatovic SM, Keep RF, Andjelkovic AV.Brain endothelial cell-cell junctions: how to “open” the blood brain barrier. Curr Neuropharmacol 2008; 6: 179–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mooradian AD, Haas MJ, Chehade JM.Age-related changes in rat cerebral occludin and zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1). Mech Ageing Dev 2003; 124: 143–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Costea L, Mészáros Á, Bauer H, et al. The blood-brain barrier and its intercellular junctions in age-related brain disorders. IJMS 2019; 20: 5472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jin X, Liu J, Liu KJ, et al. Normobaric hyperoxia combined with minocycline provides greater neuroprotection than either alone in transient focal cerebral ischemia. Exp Neurol 2013; 240: 9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu J, Weaver J, Jin X, et al. Nitric oxide interacts with caveolin-1 to facilitate autophagy-lysosome-mediated claudin-5 degradation in oxygen-glucose deprivation-treated endothelial cells. Mol Neurobiol 2016; 53: 5935–5947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang X, Liu Y, Sun Y, et al. Blood brain barrier breakdown was found in non-infarcted area after 2-h MCAO. J Neurol Sci 2016; 363: 63–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cortes A, Solas M, Pejenaute A, et al. Expression of endothelial NOX5 alters the integrity of the blood-brain barrier and causes loss of memory in aging mice. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland) 2021; 10: 1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheung TM, Ganatra MP, Peters EB, et al. Effect of cellular senescence on the albumin permeability of blood-derived endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2012; 303: H1374–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simard JM, Kent TA, Chen M, et al. Brain oedema in focal ischaemia: molecular pathophysiology and theoretical implications. Lancet Neurol 2007; 6: 258–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang H, Lv JJ, Zhao Y, et al. Endothelial genetic deletion of CD147 induces changes in the dual function of the blood-brain barrier and is implicated in Alzheimer's disease. CNS Neurosci Ther 2021; 27: 1048–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang AC, Stevens MY, Chen MB, et al. Physiological blood-brain transport is impaired with age by a shift in transcytosis. Nature 2020; 583: 425–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sweeney MD, Zhao Z, Montagne A, et al. Blood-brain barrier: from physiology to disease and back. Physiol Rev 2019; 99: 21–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Erdő F, Krajcsi P.Age-Related functional and expressional changes in efflux pathways at the blood-brain barrier. Front Aging Neurosci 2019; 11: 196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bartels AL, Kortekaas R, Bart J, et al. Blood-brain barrier P-glycoprotein function decreases in specific brain regions with aging: a possible role in progressive neurodegeneration. Neurobiol Aging 2009; 30: 1818–1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu B, Ueno M, Onodera M, et al. Age-related changes in P-glycoprotein expression in senescence-accelerated mouse. Curr Aging Sci 2009; 2: 187–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kutuzov N, Flyvbjerg H, Lauritzen M.Contributions of the glycocalyx, endothelium, and extravascular compartment to the blood-brain barrier. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018; 115: E9429–e9438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao F, Zhong L, Luo Y.Endothelial glycocalyx as an important factor in composition of blood-brain barrier. CNS Neurosci Ther 2021; 27: 26–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stoddart P, Satchell SC, Ramnath R.Cerebral microvascular endothelial glycocalyx damage, its implications on the blood-brain barrier and a possible contributor to cognitive impairment. Brain Res 2022; 1780: 147804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lipphardt M, Song JW, Goligorsky MS.Sirtuin 1 and endothelial glycocalyx. Pflugers Arch 2020; 472: 991–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Machin DR, Bloom SI, Campbell RA, et al. Advanced age results in a diminished endothelial glycocalyx. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2018; 315: H531–H539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ceafalan LC, Fertig TE, Gheorghe TC, et al. Age-related ultrastructural changes of the basement membrane in the mouse blood-brain barrier. J Cell Mol Med 2019; 23: 819–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Uemura MT, Maki T, Ihara M, et al. Brain microvascular pericytes in vascular cognitive impairment and dementia. Front Aging Neurosci 2020; 12: 80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bell RD, Winkler EA, Sagare AP, et al. Pericytes control key neurovascular functions and neuronal phenotype in the adult brain and during brain aging. Neuron 2010; 68: 409–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ding R, Hase Y, Ameen-Ali KE, et al. Loss of capillary pericytes and the blood-brain barrier in white matter in poststroke and vascular dementias and Alzheimer's disease. Brain Pathol 2020; 30: 1087–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Berthiaume AA, Schmid F, Stamenkovic S, et al. Pericyte remodeling is deficient in the aged brain and contributes to impaired capillary flow and structure. Nat Commun 2022; 13: 5912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang Z, Li X, Zhou H, et al. NG2-glia crosstalk with microglia in health and disease. CNS Neurosci Ther 2022; 28: 1663–1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xu Y, Jiang C, Wu J, et al. Ketogenic diet ameliorates cognitive impairment and neuroinflammation in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. CNS Neurosci Ther 2022; 28: 580–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harry GJ.Microglia during development and aging. Pharmacol Ther 2013; 139: 313–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Halder SK, Milner R.Exaggerated hypoxic vascular breakdown in aged brain due to reduced microglial vasculo-protection. Aging Cell 2022; 21: e13720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mazzetti S, Barichella M, Giampietro F, et al. Astrocytes expressing vitamin D-activating enzyme identify Parkinson's disease. CNS Neurosci Ther 2022; 28: 703–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Preininger MK, Kaufer D.Blood-Brain barrier dysfunction and astrocyte senescence as reciprocal drivers of neuropathology in aging. Ijms 2022; 23: 6217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mills WA, 3rd, Woo AM, Jiang S, et al. Astrocyte plasticity in mice ensures continued endfoot coverage of cerebral blood vessels following injury and declines with age. Nat Commun 2022; 13: 1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pan J, Ma N, Zhong J, et al. Age-associated changes in microglia and astrocytes ameliorate blood-brain barrier dysfunction. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2021; 26: 970–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Balusu S, Brkic M, Libert C, et al. The choroid plexus-cerebrospinal fluid interface in Alzheimer's disease: more than just a barrier. Neural Regen Res 2016; 11: 534–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Redzic ZB, Preston JE, Duncan JA, et al. The choroid plexus-cerebrospinal fluid system: from development to aging. Curr Top Dev Biol 2005; 71: 1–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dani N, Herbst RH, McCabe C, et al. A cellular and spatial map of the choroid plexus across brain ventricles and ages. Cell 2021; 184: 3056–3074 e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Braun M, Iliff JJ.The impact of neurovascular, blood-brain barrier, and glymphatic dysfunction in neurodegenerative and metabolic diseases. Int Rev Neurobiol 2020; 154: 413–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kurz C, Walker L, Rauchmann BS, et al. Dysfunction of the blood-brain barrier in Alzheimer's disease: evidence from human studies. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2022; 48: e12782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Salvioli S, Capri M, Valensin S, et al. Inflamm-aging, cytokines and aging: state of the art, new hypotheses on the role of mitochondria and new perspectives from systems biology. Curr Pharm Des 2006; 12: 3161–3171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lv S, Song HL, Zhou Y, et al. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha affects blood-brain barrier permeability and tight junction-associated occludin in acute liver failure. Liver Int 2010; 30: 1198–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bochaton T, Leboube S, Paccalet A, et al. Impact of age on systemic inflammatory profile of patients with ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction and acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2022; 53: 2249–2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang P, Zhu Z, Zang Y, et al. Increased serum complement C3 levels are associated with adverse clinical outcomes after ischemic stroke. Stroke 2021; 52: 868–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Propson NE, Roy ER, Litvinchuk A, et al. Endothelial C3a receptor mediates vascular inflammation and blood-brain barrier permeability during aging. J Clin Invest 2021; 131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Park MH, Jin HK, Bae JS.Acid sphingomyelinase-mediated blood-brain barrier disruption in aging. BMB Rep 2019; 52: 111–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Opp MR, George A, Ringgold KM, et al. Sleep fragmentation and sepsis differentially impact blood-brain barrier integrity and transport of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in aging. Brain Behav Immun 2015; 50: 259–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Szu JI, Obenaus A.Cerebrovascular phenotypes in mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2021; 41: 1821–1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li C, Wang Y, Yan XL, et al. Pathological changes in neurovascular units: lessons from cases of vascular dementia. CNS Neurosci Ther 2021; 27: 17–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shang S, Ye J, Wu J, et al. Early disturbance of dynamic synchronization and neurovascular coupling in cognitively normal Parkinson's disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2022; 42: 1719–1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu D, Ahmet I, Griess B, et al. Age-related impairment of cerebral blood flow response to K(ATP) channel opener in Alzheimer's disease mice with presenilin-1 mutation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2021; 41: 1579–1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Festoff BW, Sajja RK, van Dreden P, et al. HMGB1 and thrombin mediate the blood-brain barrier dysfunction acting as biomarkers of neuroinflammation and progression to neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease. J Neuroinflammation 2016; 13: 194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Suzuki M, Tezuka K, Handa T, et al. Upregulation of ribosome complexes at the blood-brain barrier in Alzheimer's disease patients. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2022; 42: 2134–2150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Moon WJ, Lim C, Ha IH, et al. Hippocampal blood-brain barrier permeability is related to the APOE4 mutation status of elderly individuals without dementia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2021; 41: 1351–1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gueniot F, Rubin S, Bougaran P, et al. Targeting Pdzrn3 maintains adult blood-brain barrier and central nervous system homeostasis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2022; 42: 613–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang F, Cao Y, Ma L, et al. Dysfunction of cerebrovascular endothelial cells: prelude to vascular dementia. Front Aging Neurosci 2018; 10: 376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yang Y, Kimura-Ohba S, Thompson JF, et al. Vascular tight junction disruption and angiogenesis in spontaneously hypertensive rat with neuroinflammatory white matter injury. Neurobiol Dis 2018; 114: 95–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yang Q, Wei X, Deng B, et al. Cerebral small vessel disease alters neurovascular unit regulation of microcirculation integrity involved in vascular cognitive impairment. Neurobiol Dis 2022; 170: 105750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bliss ES, Wong RH, Howe PR, et al. Benefits of exercise training on cerebrovascular and cognitive function in ageing. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2021; 41: 447–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jansen MG, Griffanti L, Mackay CE, et al. Association of cerebral small vessel disease burden with brain structure and cognitive and vascular risk trajectories in mid-to-late life. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2022; 42: 600–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lamar M, Leurgans S, Kapasi A, et al. Complex profiles of cerebrovascular disease pathologies in the aging brain and their relationship with cognitive decline. Stroke 2022; 53: 218–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nyul-Toth A, Tarantini S, DelFavero J, et al. Demonstration of age-related blood-brain barrier disruption and cerebromicrovascular rarefaction in mice by longitudinal intravital two-photon microscopy and optical coherence tomography. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2021; 320: H1370–H1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Verheggen ICM, de Jong JJA, van Boxtel MPJ, et al. Imaging the role of blood-brain barrier disruption in normal cognitive ageing. Geroscience 2020; 42: 1751–1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Takechi R, Lam V, Brook E, et al. Blood-brain barrier dysfunction precedes cognitive decline and neurodegeneration in diabetic insulin resistant mouse model: an implication for causal link. Front Aging Neurosci 2017; 9: 399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.de Oliveira J, Engel DF, de Paula GC, et al. High cholesterol diet exacerbates blood-brain barrier disruption in LDLr-/- mice: impact on cognitive function. J Alzheimers Dis 2020; 78: 97–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Balkaya M, Kim ID, Shakil F, et al. CD36 deficiency reduces chronic BBB dysfunction and scar formation and improves activity, hedonic and memory deficits in ischemic stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2021; 41: 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yang C, Liu L, Lavayen BP, et al. Therapeutic benefits of adropin in aged mice after transient ischemic stroke via reduction of blood-brain barrier damage. Stroke 2023; 54: 234–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Momenabadi S, Vafaei AA, Bandegi AR, et al. Oxytocin reduces brain injury and maintains blood-brain barrier integrity after ischemic stroke in mice. Neuromolecular Med 2020; 22: 557–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wang Z, Li T, Du M, et al. Beta-hydroxybutyrate improves cognitive impairment caused by chronic cerebral hypoperfusion via amelioration of neuroinflammation and blood-brain barrier damage. Brain Res Bull 2023; 193: 117–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Simpson JE, Wharton SB, Cooper J, et al. Alterations of the blood-brain barrier in cerebral white matter lesions in the ageing brain. Neurosci Lett 2010; 486: 246–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yoon JH, Shin P, Joo J, et al. Increased capillary stalling is associated with endothelial glycocalyx loss in subcortical vascular dementia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2022; 42: 1383–1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zipser BD, Johanson CE, Gonzalez L, et al. Microvascular injury and blood-brain barrier leakage in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging 2007; 28: 977–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wang J, Fan DY, Li HY, et al. Dynamic changes of CSF sPDGFRbeta during ageing and AD progression and associations with CSF ATN biomarkers. Mol Neurodegener 2022; 17: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pascale CL, Miller MC, Chiu C, et al. Amyloid-beta transporter expression at the blood-CSF barrier is age-dependent. Fluids Barriers CNS 2011; 8: 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.An L, Shen Y, Chopp M, et al. Deficiency of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) exacerbates brain damage and cognitive deficit in a mouse model of vascular dementia. Aging Dis 2021; 12: 732–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Alfieri A, Koudelka J, Li M, et al. Nox2 underpins microvascular inflammation and vascular contributions to cognitive decline. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2022; 42: 1176–1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Liu P, Gao Q, Guan L, et al. Atorvastatin attenuates surgery-induced BBB disruption and cognitive impairment partly by suppressing NF-kappaB pathway and NLRP3 inflammasome activation in aged mice. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2021; 53: 528–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Suo Z, Yang J, Zhou B, et al. Whole-transcriptome sequencing identifies neuroinflammation, metabolism and blood-brain barrier related processes in the hippocampus of aged mice during perioperative period. CNS Neurosci Ther 2022; 28: 1576–1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Dong R, Lv P, Han Y, et al. Enhancement of astrocytic gap junctions Connexin43 coupling can improve long-term isoflurane anesthesia-mediated brain network abnormalities and cognitive impairment. CNS Neurosci Ther 2022; 28: 2281–2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Liu Y, Fu H, Wang T.Neuroinflammation in perioperative neurocognitive disorders: from bench to the bedside. CNS Neurosci Ther 2022; 28: 484–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shen Z, Xu H, Song W, et al. Galectin-1 ameliorates perioperative neurocognitive disorders in aged mice. CNS Neurosci Ther 2021; 27: 842–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chen L, Yang N, Li Y, et al. Cholecystokinin octapeptide improves hippocampal glutamatergic synaptogenesis and postoperative cognition by inhibiting induction of A1 reactive astrocytes in aged mice. CNS Neurosci Ther 2021; 27: 1374–1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sun L, Yong Y, Wei P, et al. Electroacupuncture ameliorates postoperative cognitive dysfunction and associated neuroinflammation via NLRP3 signal inhibition in aged mice. CNS Neurosci Ther 2022; 28: 390–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wen Q, Ding Q, Wang J, et al. Cortistatin-14 exerts neuroprotective effect against microglial activation, blood-brain barrier disruption, and cognitive impairment in sepsis-associated encephalopathy. J Immunol Res 2022; 2022: 3334145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Barnes S, Chowdhury S, Gatto NM, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids are associated with blood-brain barrier integrity in a healthy aging population. Brain Behav 2021; 11: e2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Graves SI, Baker DJ.Implicating endothelial cell senescence to dysfunction in the ageing and diseased brain. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2020; 127: 102–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lucke-Wold BP, Logsdon AF, Turner RC, et al. Aging, the metabolic syndrome, and ischemic stroke: redefining the approach for studying the blood-brain barrier in a complex neurological disease. Adv Pharmacol 2014; 71: 411–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Yamazaki Y, Baker DJ, Tachibana M, et al. Vascular cell senescence contributes to blood-brain barrier breakdown. Stroke 2016; 47: 1068–1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Cheung TM, Yan JB, Fu JJ, et al. Endothelial cell senescence increases traction forces due to age-associated changes in the glycocalyx and SIRT1. Cell Mol Bioeng 2015; 8: 63–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Huang X, Hussain B, Chang J.Peripheral inflammation and blood-brain barrier disruption: effects and mechanisms. CNS Neurosci Ther 2021; 27: 36–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Erickson MA, Banks WA.Age-associated changes in the immune system and blood(-)brain barrier functions. IJMS 2019; 20: 1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Bowman GL, Dayon L, Kirkland R, et al. Blood-brain barrier breakdown, neuroinflammation, and cognitive decline in older adults. Alzheimers Dement 2018; 14: 1640–1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Trigiani LJ, Bourourou M, Lacalle-Aurioles M, et al. A functional cerebral endothelium is necessary to protect against cognitive decline. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2022; 42: 74–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Elahy M, Jackaman C, Mamo JC, et al. Blood-brain barrier dysfunction developed during normal aging is associated with inflammation and loss of tight junctions but not with leukocyte recruitment. Immun Ageing 2015; 12: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wang C, Borger V, Mohamud Yusuf A, et al. Postischemic neuroprotection associated with anti-inflammatory effects by mesenchymal stromal cell-derived small extracellular vesicles in aged mice. Stroke 2022; 53: e14–e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Mun KT, Hinman JD.Inflammation and the link to vascular brain health: timing is brain. Stroke 2022; 53: 427–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kelly PJ, Lemmens R, Tsivgoulis G.Inflammation and stroke risk: a new target for prevention. Stroke 2021; 52: 2697–2706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Saura CA, Cardinaux JR.Emerging roles of CREB-regulated transcription coactivators in brain physiology and pathology. Trends Neurosci 2017; 40: 720–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Pan Y, He X, Li C, et al. Neuronal activity recruits the CRTC1/CREB axis to drive transcription-dependent autophagy for maintaining late-phase LTD. Cell Rep 2021; 36: 109398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Pan Y, Zhou G, Li W, et al. Excitation-transcription coupling via synapto-nuclear signaling triggers autophagy for synaptic turnover and long-lasting synaptic depression. Autophagy 2021; 17: 3887–3888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Li D, Liao Q, Tao Y, et al. Downregulation of CRTC1 is involved in CUMS-induced depression-like behavior in the hippocampus and its RNA sequencing analysis. Mol Neurobiol 2022; 59: 4405–4418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Parra-Damas A, Chen M, Enriquez-Barreto L, et al. CRTC1 function during memory encoding is disrupted in neurodegeneration. Biol Psychiatry 2017; 81: 111–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Uchida S, Teubner BJW, Hevi C, et al. CRTC1 nuclear translocation following learning modulates memory strength via exchange of chromatin remodeling complexes on the Fgf1 gene. Cell Rep 2017; 18: 352–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Zhang X, Shen X, Dong J, et al. Inhibition of reactive astrocytes with fluorocitrate ameliorates learning and memory impairment through upregulating CRTC1 and synaptophysin in ischemic stroke rats. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2019; 39: 1151–1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Shu H, Wang M, Song M, et al. Acute nicotine treatment alleviates LPS-induced impairment of fear memory reconsolidation through AMPK activation and CRTC1 upregulation in hippocampus. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2020; 23: 687–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Wang Q, Wang MW, Sun YY, et al. Nicotine pretreatment alleviates MK-801-induced behavioral and cognitive deficits in mice by regulating Pdlim5/CRTC1 in the PFC. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2023; 44: 780–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Hara T, Hamada J, Yano S, et al. CREB is required for acquisition of ischemic tolerance in gerbil hippocampal CA1 region. J Neurochem 2003; 86: 805–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Sasaki T, Takemori H, Yagita Y, et al. SIK2 is a key regulator for neuronal survival after ischemia via TORC1-CREB. Neuron 2011; 69: 106–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Escoubas CC, Silva-Garcia CG, Mair WB.Deregulation of CRTCs in aging and age-related disease risk. Trends Genet 2017; 33: 303–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Espana J, Valero J, Minano-Molina AJ, et al. beta-Amyloid disrupts activity-dependent gene transcription required for memory through the CREB coactivator CRTC1. J Neurosci 2010; 30: 9402–9410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]