Abstract

Most flowering plants require animal pollination and are visited by multiple pollinator species. Historically, the effects of pollinators on plant fitness have been compared using the number of pollen grains they deposit, and the number of seeds or fruits produced following a visit to a virgin flower. While useful, these methods fail to consider differences in pollen quality and the fitness of zygotes resulting from pollination by different floral visitors. Here we show that, for three common native self-compatible plants in Southern California, super-abundant, non-native honeybees (Apis mellifera L.) visit more flowers on an individual before moving to the next plant compared with the suite of native insect visitors. This probably increases the transfer of self-pollen. Offspring produced after honeybee pollination have similar fitness to those resulting from hand self-pollination and both are far less fit than those produced after pollination by native insects or by cross-pollination. Because honeybees often forage methodically, visiting many flowers on each plant, low offspring fitness may commonly result from honeybee pollination of self-compatible plants. To our knowledge, this is the first study to directly compare the fitness of offspring resulting from honeybee pollination to that of other floral visitors.

Keywords: honey bees, Apis mellifera, geitonogamy, self-fertilization, self-pollination, inbreeding depression

1. Introduction

Approximately 85% of all angiosperms require animal visitation to successfully reproduce [1,2] and flowers of the great majority of these plants are visited by multiple pollinator species [3–5]. It has long been recognized that pollinators can vary in the amount of pollen deposited, the number of seeds produced, or the probability of fruit set resulting from of their visits [6–9]. Far less attention has been paid to differences among pollinators in the fitness of the zygotes that result from the pollen they deposit. This is despite the fact that pollinators vary considerably in a behaviour that may strongly affect fitness: the number of flowers on a plant they visit before moving to another plant. Successive visits to flowers on the same plant (geitonogamous visitation) is often the primary cause of self-fertilization in plants with large floral displays [10–12]. For self-compatible plants, self-fertilization often severely reduces the fitness of offspring compared to those produced via cross-fertilization [13,14]. For self-incompatible plants, self-pollination may result in fewer seeds set or fruits produced even when stigmatic pollen loads delivered are large [15,16].

Inbreeding depression (IBD), the reduced fitness of self-fertilized progeny in comparison to cross-fertilized ones, has been widely measured in plants since it is thought to be a primary selective force acting on plant mating systems [13,17]. Studies of IBD cataloged in several reviews have shown that the fitness of self-fertilized zygotes is often less than half that of cross-fertilized ones [14,18,19]. In addition, reductions in fitness due to self-fertilization tend to be larger for longer-lived plants, reflecting either higher levels of deleterious somatic mutations [20], higher population levels of outcrossing which maintains more genetic load in populations, or larger cumulative effects of deleterious alleles over longer lifespans [21]. Finally, the timing of the expression of IBD varies, with longer-lived, generally more outcrossing plants showing more IBD early in the life cycle (i.e. between fertilization and seed set or germination) than is observed in annual herbs [18,22].

We were motivated to investigate the fitness of seeds produced by native plants resulting from different pollinators in San Diego County, California, USA for the following reasons. First, honeybees forage methodically, and casual observation suggested that their levels of geitonogamous visitation are perhaps higher than the average among native pollinating insects. Self-fertilization rates are known to increase as the number of flowers consecutively visited on a plant during a foraging bout increase [23]. This led us to hypothesize that if honeybees make more geitonogamous visits, the offspring that result from their pollination might have reduced fitness due to the negative effects of inbreeding.

In addition, studies in San Diego County have shown that non-native, primarily feral, honeybees (Apis mellifera L.) are by far the most common floral visitors to native plants in the region [24]. In intact habitats with native vegetation, honeybees make up approximately 75% of all floral visitors. Honeybees are even more dominant on the most abundantly blooming species, often exceeding 90% of all visitors [24]. This is among the highest levels of honeybee community dominance recorded anywhere in the world [25]. At the same time, San Diego County is a biodiversity hotspot with over 600 species of native bees [26] and at least 2400 plant taxa [27]. Therefore, the impacts of this highly abundant non-native pollinator on the plants they pollinate are of interest.

2. Results and discussion

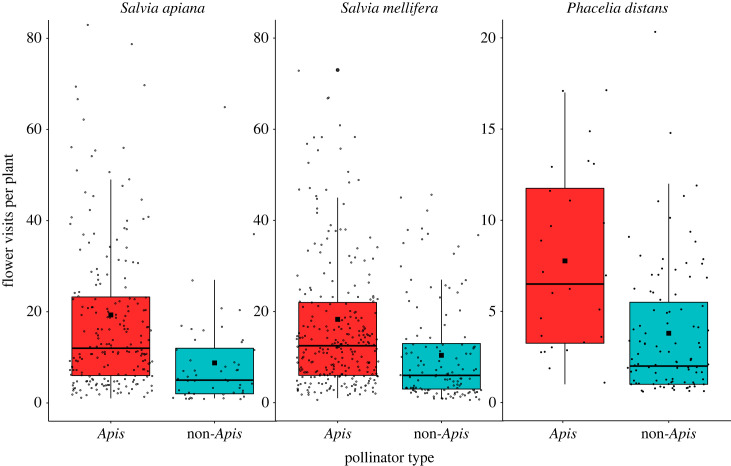

We recorded the number of flowers visited per plant for 212 Apis and 51 non-Apis visitors on Salvia apiana, 274 Apis and 131 non-Apis visitors on S. mellifera and 27 Apis and 99 non-Apis visitors on P. distans. Apis on average made 1.76–2.33 times as many geitonogamous visits per plant compared to non-Apis floral visitors which comprise a suite of overwhelmingly native insects [26] (p < 0.0001 for all three species, figure 1, electronic supplementary material, table S4). Detailed identities and frequencies of insect visitors to plants in western San Diego County can be found at https://library.ucsd.edu/dc/collection/bb0072854b.

Figure 1.

The number flowers visited per plant by Apis and non-Apis pollinators during single foraging bouts. Boxplots: the lines show medians; black squares show means; boxes and the whiskers represent interquartile ranges; dots represent individual insect foraging bouts. For all three species, honeybees visited more flowers per plant compared to non-Apis insects (p < 0.0001). See electronic supplementary material, table S4 for statistical model outputs.

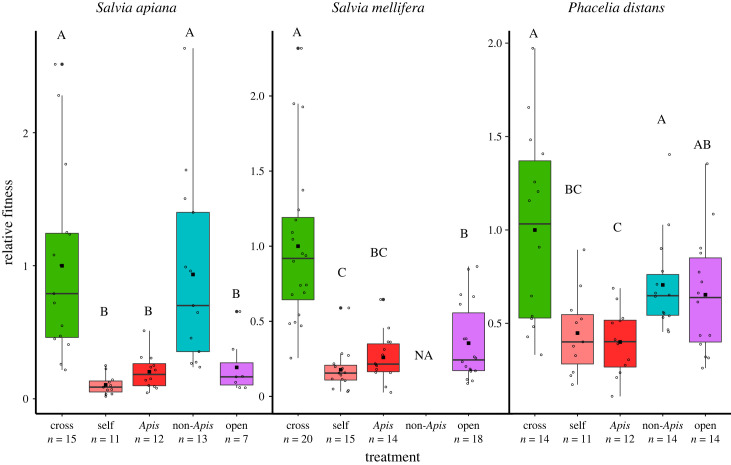

All three plant species exhibited strong inbreeding depression, with cross-pollination providing 2- to 10-fold higher multiplicative fitness values when germinated and then grown in a greenhouse (figure 2; electronic supplementary material, tables S1–S3 and S6). Consistent with results of meta-analyses of inbreeding depression [28,29], the two perennial species (S. mellifera and S. apiana) exhibited greater fitness differences between self- and cross-pollination treatments than the annual P. distans. We also observed strong inbreeding depression in both early (seed set, germination, electronic supplementary material, tables S7 and S8) and later (number of leaves, electronic supplementary material, table S10) life stages in the Salvia species, while differences between self- and cross-pollination treatments in the annual P. distans were significant but smaller than the perennial species for seed set and germination rate, and there were differences among these treatments in the production of flowers (electronic supplementary material, tables S3 and S11). For all three species, there was no significant difference among treatments in seedling survival to ten weeks (electronic supplementary material, table S9).

Figure 2.

Relative fitness of each pollination treatment for each plant species. All values have been standardized so that the mean fitness of cross treatments equal 1. Boxplots: the lines show medians; black squares show means; boxes and the whiskers represent interquartile ranges; dots represent mean values for maternal plant families. Bold letters signify statistical differences between treatments. Pollination treatment had a significant effect for all three species (p < 0.0001). See electronic supplementary material, tables S1–S3 for full model outputs for each fitness trait measured.

Fitness resulting from single Apis visits did not differ from the hand self-pollination treatment for all three species. For the two species (S. apiana and P. distans) with sufficient native insect visitation to allow us to assess the reproductive consequences, fitness resulting from single visits by native pollinators was not different than fitness from hand cross-pollination and two to fivefold greater than fitness resulting from pollination by Apis or hand self-pollination. For the two species of Salvia, the fitness measured for open-pollinated seeds was not significantly different from the fitness of seeds from the Apis pollination treatment, probably reflecting the fact that the vast majority of visits to those species were likely made by honeybees (electronic supplementary material, table S12). For P. distans, open-pollinated seeds had an average fitness intermediate between self- and cross- treatments and intermediate between non-Apis and Apis pollination treatments. This may reflect the sizeable fraction (20–25%) of visitors to this species that were native pollinators, or that P. distans plants have significantly fewer flowers open simultaneously compared to the Salvia species. It should be noted that these fitness measures come from greenhouse estimates of fitness components. Greenhouse experiments often underestimate the cost of selfing relative to outcrossing in comparison to estimates based on measurements made in more stressful, field environments [30,31].

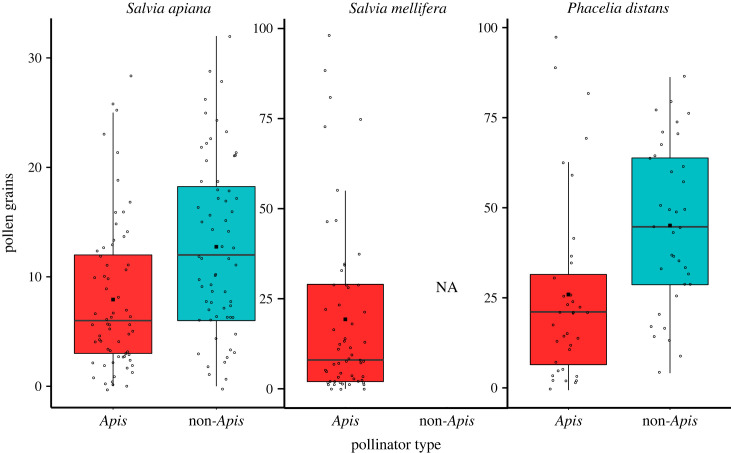

Differences between Apis and non-Apis pollination treatments in seed set could reflect pollen limitation if single Apis visits deliver fewer pollen grains than those of native insects, and if the amount of pollen they deliver limits seed set. We measured stigmatic pollen loads following single visits to previously unvisited flowers by honeybees and native pollinators. We examined 64 Apis and 63 non-Apis pollinated stigmas from S. apiana, and 37 Apis and 35 non-Apis pollinated stigmas from P. distans. For S. mellifera, we collected 55 stigmas that were visited by Apis. For S. apiana and P. distans, pollen deposition following single visits by Apis and non-Apis pollinators did not differ significantly, though honeybees deposited somewhat fewer grains, on average, in both species (figure 3; electronic supplementary material, table S5).

Figure 3.

The number of pollen grains deposited on stigmas in a single visit by Apis and non-Apis pollinators. Boxplots: features are the same as in figure 1. Honeybees deposit a similar number of pollen grains as non-Apis insects for S. apiana and P. distans (p > 0.05). See electronic supplementary material, table S5 for full model outputs.

Whether the amount of pollen deposited by single Apis visits limited seed set is more difficult to assess. All three species have four ovules per flower and can produce a maximum of four seeds per fruit. When given abundant cross-pollen, all three species averaged approximately two seeds per flower (electronic supplementary material, tables S1–S3). The mean single visit pollen deposition by Apis was 7.9 (s.e. = 0.85), 19.8 (s.e. = 3.20), and 29.9 (s.e. = 4.57) grains for S. apiana, S. mellifera and P. distans respectively, which seems to be sufficient for full seed set since ad libitum deposition of self-pollen did not produce significantly more seeds than single Apis visits in any of the three species. For Salvia apiana and S. mellifera, the open pollination treatment, in which flowers are typically visited multiple times per day by Apis (D.J.T. 2023, unpublished data), also did not produce significantly more seeds than did single Apis visits. For P. distans, which garners more visitation from native insects, open pollinated seed set did not differ from that which resulted from hand cross-pollination (electronic supplementary material, table S3). By contrast, for both S. apiana and P. distans, single visits by non-Apis pollinators resulted in seed set values that did not differ from application of abundant cross-pollen, indicating differences in the quality of pollen delivered between the two types of pollinators. Further, in S. apiana, the species with the lowest pollen deposition following single Apis visits, differences between Apis and non-Apis pollination treatments for fitness components that occur after seed set (germination and leaf production) are significant, again indicating differences in the quality of pollen received from different pollinators (electronic supplementary material, table S1).

Our findings have several major implications. First, honeybees are estimated to be the most frequent floral visitors to natural vegetation worldwide, accounting for 13% of all floral visits globally [25]. Pollination studies of many plant species, or whole-community pollination networks, often use visitation rates as the measure of a pollinator's importance. Some go further and refine these estimates of importance by multiplying them by single visit pollinator effectiveness, measured as pollen grains delivered, seeds set or probability of fruit set [16,32,33]. While measures of single-visit effectiveness of honeybees vary across plant species, meta-analyses have shown that, on average, their effectiveness is not different than the mean of other pollinators visiting the same species [25,34]. But if pollinators deliver pollen of different quality (e.g. primarily self- versus outcross pollen) that leads to strong differences in the fitness of the offspring produced, this will impact the importance of different pollinators to a plant's reproductive success. The fitness differences resulting from honeybee versus primarily native, non-Apis insect visits measured here indicate that a pollinator's real importance may be strongly influenced by their foraging behaviour (e.g. differences in geitonogamous visitation) and the pollen quality delivered. High levels of self-pollen delivered by honeybees may also help explain why, across a wide range of 41 crops, increased visitation by non-honeybee insects increased seed or fruit set regardless of the amount of honeybee visitation [35].

Few studies have measured the fitness of seeds resulting from different pollinators or sets of pollinators [8,36–38], and none have directly compared the fitness effects of honeybee visits to those of other insects. In the most relevant study, Herrera [8] planted seeds of Lavandula latifolia that resulted from exposure to pollinators at different times of day. In a field planting study, seeds from flowers exposed only to pollinators during the early morning and late evening were significantly less likely to germinate and survive than seeds which resulted from flowers exposed to pollinators only during the middle of the day. This plant has an array of floral visitors. Large bees, which were predominantly honeybees, visit throughout the day, but lepidoptera and small bees, which made up a minority of pollinators, were more common in the middle of the day than when cooler temperatures prevailed. Herrera [8] attributed the observed fitness differences to the fact that small bees and, particularly, lepidoptera, make fewer geitonogamous visits than do large bees. The fact that both Herrera's study and ours implicate honeybees as pollinators whose services result in low quality offspring should motivate further research into the generality of whether honeybees tend to deliver more geitonogamous self-pollen than other pollinators, and the fitness consequences that may result.

Clearly one limitation of our study is that we could only directly compare offspring fitness resulting from honeybee and non-honeybee pollination in two species. More studies of this nature are warranted both in San Diego County and elsewhere before the generality of the effects of honeybee pollination on plant offspring fitness can be more fully assessed. An additional weakness of our study is that we did not directly measure the self-fertilization rate that results from honeybee and non-honeybee pollination. Genomic tools could be used to measure the inbreeding coefficients of both parental plants and their offspring. This approach could quantify differences in levels of inbreeding of offspring produced by different pollinators. In addition, estimates of inbreeding depression in the field could be obtained by comparing differences in inbreeding coefficients of adult plants and seeds or seedlings [39].

In San Diego County (USA), non-native, feral, honeybees dominate the pollinator community that visits native plants. Many of these native plant species are self-compatible, so if honeybees generally transfer pollen that reduces the fitness of offspring there could be many ecological consequences. We speculate on just three. First, to the degree that individual species become more inbred due to honeybee pollination, their evolutionary future might be compromised. This is important because San Diego County is biodiversity hotspot having the most plant taxa of any county in the USA [27]. Second, if honeybees generally lower seed fitness of native plants, this could make the native the plant community more susceptible to invasion by introduced plant species that do not require insect pollination, or which are historically highly self-fertilizing, such as invasive annual Mediterranean grasses and mustard species (Hirschfeldia incana and Brassica nigra) that currently occupy much of the space between native shrubs and increase the ecosystem's susceptibility to fire. Third, to the extent that honeybees focus their resource gathering efforts on the most abundantly blooming taxa, ignoring or at least not fully dominating visitation to rarer taxa [24], they might preserve plant diversity by reducing the fitness of the most abundant plant species. It is impossible to predict all the repercussions of high honeybee abundance and the lower reproductive fitness of the plants they pollinate, but these effects are likely to be substantial.

3. Material and methods

We compared the effects of honeybees and native pollinating insects on the reproductive fitness of three common plant species in coastal sage scrub habitats of San Diego County: Phacelia distans (common phacelia, Boraginaceae) an annual herb, and both Salvia mellifera (black sage, Lamiaceae) and Salvia apiana (white sage, Lamiaceae) which are perennial shrubs. All three species produce protandrous hermaphroditic flowers on multiple inflorescences and commonly display dozens to hundreds of flowers at once, with both male (anthers dehiscent) and female (stigmas receptive) phase flowers open simultaneously. All three species are self-compatible [40,41] and therefore visits to multiple flowers on the same plant may lead to geitonogamous self-fertilization and potentially lower the fitness of the resulting zygotes. The two Salvia species are large shrubs, and during peak bloom, are often the most abundantly flowering species at a given site and attract a large (greater than 90%) fraction of floral visits from honeybees. Phacelia distans, an annual, is rarely the most abundantly blooming plant at a given site and a greater proportion of non-Apis visitors were observed for this plant compared to the two Salvia species (electronic supplementary material, table S12).

To determine if non-native honeybees make more geitonogamous visits than native pollinators, in 2018 we identified sites where at least one of our plant species occurred in intact coastal sage scrub habitat (S. apiana: 4 sites and 22 plants; S. mellifera: 2 sites and 37 plants; P. distans: 1 site and 44 plants). During peak bloom for each species, we collected visitation data from 10.00 to 16.00 on days with less than 50% cloud cover, little to no wind, and air temperatures exceeding 16°C to minimize environmental impacts on foraging behaviour. Visitation data were collected by observing a pollinator approach a plant and counting the number of flowers they visited before moving on to another plant or out of our field of vision. For each foraging bout, we recorded the site, date, plant species and individual, pollinator type (Apis or non-Apis), and the number of flowers the pollinator visited before moving on. Due to the diversity of native insect visitors, our interest in comparing non-native honeybees to the native pollinator community, and the expertise required to identify insects on the fly to the species level, pollinators were classified as Apis or non-Apis.

To assess single visit pollen deposition, in 2021 we exposed receptive, unvisited stigmas to one visit from a honeybee or a non-Apis insect. After the insect contacted the stigma, we immediately collected stigmas and pressed them into fuchsin jelly on a microscope slide and later counted pollen grains with a dissecting microscope. Plants used for this pollen deposition study were at the same sites used previously, but the individual plants studied were not same across all years.

We measured the fitness effects of different pollination treatments as follows. In the spring of 2018, we identified 5 individuals of S. apiana at each of 3 sites, and in the spring of 2019, we added 15 individuals of S. apiana at each of 2 sites, 15 S. mellifera individuals at each of 2 sites and 30 P. distans individuals at a single site (electronic supplementary material, table S13). In total, we studied 45 S. apiana, 30 S. mellifera and 30 P. distans individuals. Before pollination treatments, we placed mesh pollinator-exclusion bags over 6 inflorescences on each plant to prevent visitation. During peak bloom for each species, we returned to individual plants and removed the mesh bags to expose unvisited female phase flowers to one of the following six pollination treatments. 1. Open-pollinated (control) flowers were exposed to visitation for the duration of a flower's life to assess pollination and seed set in field conditions. 2. Cross-pollinated flowers were hand pollinated using pollen from 3–5 individuals at least 20 m away to minimize any impact of donor identity. Pollen was transferred to a stigma using forceps ad libitum until the stigmas were well coated with pollen. 3. Self-pollinated flowers were hand pollinated with pollen acquired from 3–5 fresh anthers from the same plant, and stigmas were again well coated with pollen. 4. Apis-pollinated flowers were exposed until a single Apis was observed foraging on an unvisited flower, after which the inflorescence was bagged to exclude further visitation. 5. Non-Apis insect-pollinated flowers were exposed until a single non-Apis insect visited a flower and then bagged to exclude further visitation. 6. The pollinator exclusion treatment in which flowers where enclosed in mesh bags for their lifetime to determine the degree to which pollinators are necessary for set seed. The calyx of each treatment flower was marked with a dot of acrylic paint, and after 4 to 6 weeks mature seeds were recovered. Due to insufficient visitation by non-Apis insects to experimental flowers of Salvia mellifera, we were unable to assess the impact non-Apis pollination for this species.

We counted the number of seeds produced in each pollination treatment for every maternal plant. Seeds that were less than 10% normal size and appeared aborted were not included. After counting, seeds were washed with a 10% bleach solution, dried, and stored at 4°C for at least 6 months to help break seed dormancy. In late January 2020, seeds were removed from storage and placed into sterile filter paper lined Petri dishes. Seeds produced from the pollinator exclusion treatment were not included due to greenhouse space constraints. Since both Salvia species have low (10–20%) germination rates [38], we employed a variety of treatments to promote germination. After being removed from 4°C, Salvia seeds were heated to 70°C for 1 h [42], treated with a 1:10 dilution of Wrights liquid smoke [43], then soaked in 5–6 ml of a 500 ppm solution of gibberellic acid in deionized water overnight [44]. To further stimulate germination, Petri dishes containing the hydrated Salvia spp. seeds were placed on a warming mat set to 26°C and exposed to the natural light in the greenhouse [42]. P. distans seeds germinate readily so the seeds were placed in Petri dishes, soaked in 5–6 ml of deionized water, and placed in the dark to encourage germination.

Each morning we examined all Petri dishes, if a seed's radical had emerged, the date was recorded, and the seed was planted in a pot (5 × 12″ tree pots, Stuewe & Sons) filled with native topsoil and placed in a randomized position within our greenhouse. Due to the space limitations, if two seeds from the same parent and treatment germinated on the same day, they were placed on opposite sides of the same pot. After four weeks, if both seedlings were alive in the same pot, one was culled at random. After four weeks we counted the number of seeds that failed to germinate in each Petri dish.

Seedlings were watered with 200 ml of water twice a week using an automated drip irrigation system (DripWorks). All pot positions were re-randomized within the greenhouse 4 and 8 weeks after the beginning of the experiment to reduce microclimate effects. 10 weeks after germination the following were measured: percent germination, survival to 10 weeks, and for Salvia apiana and S. mellifera, the number of leaves at 10 weeks as a proxy for size [18,45] which is strongly associated with reproductive output in plants [46]. For the annual P. distans, which reaches sexual maturity several weeks after germination, we counted the number of flowers each plant produced. We then calculated mean values of these traits for each maternal parent plant for every treatment. Relative fitness for each treatment and maternal plant was calculated using a multiplicative fitness function [18,45]. For S. apiana and S. mellifera, relative fitness of each treatment was calculated as the product of mean seed set, germination success, proportion of seedlings that survived at 10 weeks, and the number of leaves at 10 weeks. For P. distans, relative fitness was calculated in a similar fashion except the mean number of flowers produced for each treatment was used in place of the number of leaves.

4. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted in R (v. 3.5.0, 2021), using packages lme4 [47], nlme [48], lmerTest [49], lattice [50], Rmisc [51], multcomp [52], lsmeans [53], ggplot2 [54] and plyr [55].

We used generalized mixed-effects models to assess differences in single visit pollen deposition between pollinator types for each plant species. Each model had a Poisson distribution with a log link function. Random effects considered were plant identity, site and date. Plant identity was nested in site, and site was nested in date. The fixed effect considered in each of these models was pollinator type (Apis or non-Apis). We used linear mixed-effect models to determine differences in single visit pollen deposition between Apis and non-Apis pollinators for each plant species. Random effects considered were date, individual plant identity, and site when applicable. Individual plant identity was nested in site, and site was nested in date. The fixed effect considered in the models was pollinator type (Apis or non-Apis). Single visit pollen deposition values were square root transformed to fit model assumptions. To assess differences in relative fitness (log10 transformed) between pollination treatments, we constructed a linear mixed-effect model with maternal identity, site and year as random effects when applicable for each plant species. Again, maternal identity was nested in site, and site was nested in year. The fixed effect considered was pollination treatment in all models. Random effects in each model were tested by performing likelihood ratios tests. If models failed to converge, the random effect that caused the failure was removed. For all models, we conducted an analysis of variance (ANOVA) test and extracted P- and F- values when applicable.

Acknowledgements

D. Meszaros, J. Bohey, J. Noonan, N. Callen, B. Tsai, M. Musse and J. Waits assisted in data collection. This work was performed in part at the University of California Natural Reserve System's Elliott Chaparral and Dawson Los Monos Canyon Reserves. The comments of two anonymous reviewers improved the clarity of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Dillon J. Travis, Email: dtravis@ucsd.edu.

Joshua R. Kohn, Email: jkohn@ucsd.edu.

Data accessibility

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available at the Knowledge Network for Biocomplexity repository (http://knb.ecoinformatics.org/view/doi:10.5063/F1RF5SGF) [56].

Additional information is provided in electronic supplementary material [57].

Authors' contributions

D.J.T.: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, validation, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; J.R.K.: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, visualization, writing—review and editing.

All authors gave final approval for publication and agreed to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Conflict of interest declaration

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding

D.J.T. was supported by grants from Sea and Sage Audubon Society, the Messier Family Fund and by a UC MRPI grant to J.R.K.

References

- 1.Ollerton J, Winfree R, Tarrant S. 2011. How many flowering plants are pollinated by animals? Oikos 120, 321-326. ( 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2010.18644.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ne'eman G, Jürgens A, Newstrom-Lloyd L, Potts SG, Dafni A. 2010. A framework for comparing pollinator performance: effectiveness and efficiency. Biol. Rev. 85, 435-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olesen JM. 2000. Exactly how generalised are pollination interactions. Det Norske Videnskaps-Akademi. I. Matematisk Naturvidensskapelige Klasse, Skrifter. Ny Serie 39, 161-178. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herrera CM. 1996. Floral traits and plant adaptation to insect pollinators: a devil's advocate approach. In Floral biology (eds Lloyd DG, Barrett SCH), pp. 65-87. New York, NY: Chapman & Hall. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waser NM, Chittka L, Price MV, Williams NM, Ollerton J. 1996. Generalization in pollination systems, and why it matters. Ecology 77, 1043-1060. ( 10.2307/2265575) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rader R, et al. 2004. Alternative pollinator taxa are equally efficient but not as effective as the honeybee in a mass flowering crop. J. Appl. Ecol. 46, 1080-1087. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2009.01700.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fenster CB, Armbruster WS, Wilson P, Dudash MR, Thomson JD. 2004. Pollination syndromes and floral specialization. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 35, 375-403. ( 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132347) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herrera CM. 2000. Flower-to-seedling consequences of different pollination regimes in an insect-pollinated shrub. Ecology 81, 15-29. ( 10.1890/0012-9658(2000)081[0015:FTSCOD]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herrera CM. 1987. Components of pollinator ‘quality': comparative analysis of a diverse insect assemblage. Oikos 1, 79-90. ( 10.2307/3565403) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eckert CG. 2000. Contributions of autogamy and geitonogamy to self-fertilization in a mass-flowering, clonal plant. Ecology 81, 532-542. ( 10.1890/0012-9658(2000)081[0532:COAAGT]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snow AA, Spira TP, Simpson R, Klips RA. 1996. The ecology of geitonogamous pollination. In Floral biology (eds Lloyd DG, Barrett SCH), pp. 191-216. New York, NY: Chapman & Hall. [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Arroyo MTK. 1976. Geitonogamy in animal pollinated tropical angiosperms: a stimulus for the evolution of self-incompatibility. Taxon 25, 543-548. ( 10.2307/1220107) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charlesworth D, Willis JH. 2009. The genetics of inbreeding depression. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 783-796. ( 10.1038/nrg2664) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winn A, et al. 2011. Analysis of inbreeding depression in mixed-mating plants provides evidence for selective interference and stable mixed mating. Evolution 65, 3339-3359. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01462.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diller C, Castañeda-Zárate M, Johnson SD. 2022. Why honeybees are poor pollinators of a mass-flowering plant: experimental support for the low pollen quality hypothesis. Am. J. Bot. 109, 1305-1312. ( 10.1002/ajb2.16036) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eeraerts M, Vanderhaegen R, Smagghe G, Meeus I. 2020. Pollination efficiency and foraging behaviour of honey bees and non-Apis bees to sweet cherry. Agric. For. Entomol. 22, 75-82. ( 10.1111/afe.12363) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charlesworth B, Charlesworth D. 1999. The genetic basis of inbreeding depression. Genet. Res. 74, 329-340. ( 10.1017/S0016672399004152) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Husband BC, Schemske DW. 1995. Magnitude and timing of inbreeding depression in a diploid population of Epilobium angustifolium (Onagraceae). Heredity 75, 206-215. ( 10.1038/hdy.1995.125) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Angeloni F, Ouborg NJ, Leimu R. 2011. Meta-analysis on the association of population size and life history with inbreeding depression in plants. Biol. Conserv. 144, 35-43. ( 10.1016/j.biocon.2010.08.016) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scofield DG, Schultz ST. 2006. Mitosis, stature and evolution of plant mating systems: low-Φ and high-Φ plants. Proc. R. Soc. B 273, 275-282. ( 10.1098/rspb.2005.3304) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morgan MT, Schoen DJ, Bataillon TM. 1997. The evolution of self-fertilization in perennials. Am. Nat. 150, 618-638. ( 10.1086/286085) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duminil J, Hardy OJ, Petit RJ. 2009. Plant traits correlated with generation time directly affect inbreeding depression and mating system and indirectly genetic structure. BMC Evol. Biol. 9, 1-14. ( 10.1186/1471-2148-9-177) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karron JD, Holmquist KG, Flanagan RJ, Mitchell RJ. 2009. Pollinator visitation patterns strongly influence among-flower variation in selfing rate. Ann. Bot. 103, 1379-1383. ( 10.1093/aob/mcp030) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hung KLJ, Kingston JM, Lee A, Holway DA, Kohn JR. 2019. Non-native honey bees disproportionately dominate the most abundant floral resources in a biodiversity hotspot. Proc. R. Soc. B 286, 20182901. ( 10.1098/rspb.2018.2901) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hung KLJ, Kingston JM, Albrecht M, Holway DA, Kohn JR. 2018. The worldwide importance of honey bees as pollinators in natural habitats. Proc. R. Soc. B 285, 20172140. ( 10.1098/rspb.2017.2140) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hung KLJ, Cen HJ, Lee A, Holway DA. 2020. Plant-pollinator interaction networks in coastal sage scrub reserves and fragments in San Diego. UC San Diego Library Digital Collections 10, J0DZ067F. ( 10.6075/J0DZ067F) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rebman JP, Simpson MG. 2014. Checklist of the vascular plants of San Diego County, 5th edn. San Diego, CA: San Diego Natural History Museum. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Byers DL, Waller DM. 1999. Do plant populations purge their genetic load? Effects of population size and mating history on inbreeding depression. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 30, 479-513. ( 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.30.1.479) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lloyd DG, Schoen DJ. 1992. Self-and cross-fertilization in plants. I. Functional dimensions. Int. J. Plant Sci. 153, 358-369. ( 10.1086/297040) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Armbruster P, Reed DH. 2005. Inbreeding depression in benign and stressful environments. Heredity 95, 235-242. ( 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800721) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fox CW, Reed DH. 2010. Inbreeding depression increases with maternal age in a seed-feeding beetle. Evol. Ecol. Res. 12, 961-972. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Monzón VH, Bosch J, Retana J. 2004. Foraging behavior and pollinating effectiveness of Osmia cornuta (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) and Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera: Apidae) on ‘Comice’ pear. Apidologie 35, 575-585. ( 10.1051/apido:2004055) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Santiago-Hernández MH, et al. 2019. The role of pollination effectiveness on the attributes of interaction networks: from floral visitation to plant fitness. Ecology 100, e02803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Page ML, et al. 2021. A meta-analysis of single visit pollination effectiveness comparing honeybees and other floral visitors. Am. J. Bot. 108, 2196-2207. ( 10.1002/ajb2.1764) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garibaldi LA, Steffan-Dewenter I, Winfree R, Aizen MA, Bommarco R, Cunningham SA, Klein AM. 2013. Wild pollinators enhance fruit set of crops regardless of honey bee abundance. Science 339, 1608-1611. ( 10.1126/science.1230200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hervias-Parejo S, Traveset A. 2018. Pollination effectiveness of opportunistic Galapagos bords compared to that of insects: from fruit set to seedling emergence. Am. J. Bot. 105, 1142-1153. ( 10.1002/ajb2.1122) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Valverde J, Perfectti F, Gómez JM. 2019. Pollination effectiveness in a generalist plant: adding the genetic component. New Phytol. 223, 354-365. ( 10.1111/nph.15743) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gómez JM. 2000. Phenotypic selection and response to selection in Lobularia maritima: importance of direct and correlational components of natural selection. J. Evol. Biol. 13, 689-699. ( 10.1046/j.1420-9101.2000.00196.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ritland K. 1990. Inferences about inbreeding depression based on changes of the inbreeding coefficient. Evolution 44, 1230-1241. ( 10.2307/2409284) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Montalvo AM. 2004. Salvia apiana Jepson. In Wildland shrubs of the United States and its territories: thamnic descriptions, vol. 1 (ed. Francis JK), pp. 671-675. Fort Collins, CO: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, International Institute of Tropical Forestry and Rocky Mountain Research Station. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Montalvo AM, McMillan P. 2004. Salvia mellifera Greene. Wildland Shrubs of the United States and its Territories: Thamnic Descriptions. General Technical Report IITF-GTR-26, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, International Institute of Tropical Forestry and Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fort Collins, CO. 1, 676–680.

- 42.Keeley JE. 1987. Role of fire in seed germination of woody taxa in California chaparral. Ecology 68, 434-443. ( 10.2307/1939275) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilkin KM, Holland VL, Keil D, Schaffner A. 2013. Mimicking fire for successful chaparral restoration. Madroño 60, 165-172. ( 10.3120/0024-9637-60.3.165) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Emery DE. 1988. Seed propagation of native California plants. Santa Barbara, CA: Santa Barbara Botanic Garden. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kittelson PM, Maron JL. 2000. Outcrossing rate and inbreeding depression in the perennial yellow bush lupine, Lupinus arboreus (Fabaceae). Am. J. Bot. 87, 652-660. ( 10.2307/2656851) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weiner J, Campbell LG, Pino J, Echarte L. 2009. The allometry of reproduction within plant populations. J. Ecol. 97, 1220-1233. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2009.01559.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1-48. ( 10.18637/jss.v067.i01) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D. 2019. nlme: linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. R package version 3.1–142. See https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme.

- 49.Kuznetsova A, Brockhoff PB, Christensen RB. 2017. lmerTest package: tests in linear mixed effects models. J. Stat. Softw. 82, 1-26. ( 10.18637/jss.v082.i13) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sarkar D. 2008. Lattice: multivariate data visualization with R. New York, NY: Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-75968-5. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hope RM. 2013. Rmisc: ryan miscellaneous. R package version 1.5. See https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=Rmisc.

- 52.Hothorn T, Bretz F, Westfall P. 2008. Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biom. J. 50, 346-363. ( 10.1002/bimj.200810425) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lenth RV. 2016. Least-squares means: the R package lsmeans. J. Stat. Softw. 69, 1-33. ( 10.18637/jss.v069.i01) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wickham H. 2016. Ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wickham H. 2011. The split-apply-combine strategy for data analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 40, 1-29. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Travis DJ, Kohn JR. 2022. Traits associated with fitness, flower visits per plant, single visit pollen deposition, pollinator abundance in San Diego County, USA (2018–2021). knb dataset. (http://knb.ecoinformatics.org/view/doi:10.5063/F1RF5SGF)

- 57.Travis DJ, Kohn JR. 2023. Honey bees (Apis mellifera) decrease the fitness of plants they pollinate. Figshare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.6697775) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Travis DJ, Kohn JR. 2022. Traits associated with fitness, flower visits per plant, single visit pollen deposition, pollinator abundance in San Diego County, USA (2018–2021). knb dataset. (http://knb.ecoinformatics.org/view/doi:10.5063/F1RF5SGF)

- Travis DJ, Kohn JR. 2023. Honey bees (Apis mellifera) decrease the fitness of plants they pollinate. Figshare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.6697775) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available at the Knowledge Network for Biocomplexity repository (http://knb.ecoinformatics.org/view/doi:10.5063/F1RF5SGF) [56].

Additional information is provided in electronic supplementary material [57].