Abstract

Healthcare decision-makers are becoming increasingly aware that climate change poses significant threats to population health and continued delivery of quality care. Challengingly, responding to climate change requires complex, often expensive, and multi-faceted actions to limit new emissions from worsening climate trajectories, while investing in climate-resilient systems. We present a Climate Resilience Maturity Matrix that brings together both mitigation and adaptation actions into a high-level tool for health leaders, for supporting organizational review, assessment, and decision-making for climate change readiness. This tool is designed to (i) support leaders in Canadian health facilities and regional health authorities in designing mitigation and adaptation roadmaps, (ii) support decision-making for climate change-related strategic planning processes, and (iii) create a high-level overview of organizational readiness. This tool is intended to consolidate key data, provide a clear communication tool, allow for objective rapid baselining, enable system-level gap analysis, facilitate comparability/transparency, and support rapid learning cycles.

How the climate crisis affects healthcare organizations

Climate change is an intensifying threat to human health and health systems. 1 Health systems will face increasing demand from climate-related impacts on health, as well as physical risks to health infrastructure and supply chains. 2 Projections show the top climate change threats to the health of Canadians 2 are (1) heat-linked health burdens 3 ; (2) declining air quality; and (3) increasing incidence of Lyme disease. Both increased heat and poor air quality are linked to respiratory and cardiac issues, which are among the top five reasons for hospital admissions in Canada; in this way, climate change will intensify what is already a considerable burden of disease for health systems, such as exacerbating surge volumes during extreme weather events. 4 Further, as the health sector is a major emitter of greenhouse gases, responsible for approximately 5% of Canada’s overall emissions, 5 addressing the carbon footprint of health systems is also vital for reducing future climate change. These risks to healthcare are substantial, with the threat magnifying for the worse climate trajectories.

Health leaders are faced with the challenge of designing strategic plans which protect populations from the impacts of climate change. Addressing climate change requires both mitigation (reducing greenhouse gas emissions) and adaptation (adjusting to the actual or expected climate, so as to moderate harm or exploit beneficial opportunities). 6 Climate-resilient health systems aim to be: “capable of anticipating, responding to, coping with, recovering from, and adapting to climate-related shocks and stresses, so as to bring about sustained improvements in population health, despite an unstable climate.” 7 Strategic planning for climate-ready health system functions8,9 includes supporting effective leadership and governance; training and supporting the health workforce; assessing climate change vulnerability; designing systems for integrated risk monitoring and early warning; funding health/climate research; ensuring that health-system technologies, products, and infrastructure are designed to withstand current and projected future climate impacts, and are minimizing greenhouse gas emissions; managing the environmental determinants of health; designing and implementing health programs that are adaptive to climate change impacts and/or address greenhouse gas emissions; ensuring effective emergency preparedness and response; and ensuring there is adequate funding in place for all of these activities. Such strategic planning for the climate crisis by health leaders is complex and time-consuming.

Climate change will affect human health substantially, and innovations are needed to accelerate climate resiliency in health organizations. As many of these organizations have not begun action, tools are needed to support strategic planning and how to get started. Here, the Climate Resilience Maturity Matrix is presented as a tool to enhance strategic planning for health leaders. In this article, we are focusing on regional- and local-level policy-making, which is generally carried out by regional health authorities (a collective term for regional/provincial health authorities, local health units, and centres integrés universitaires de santé et de services sociaux 10 ), and individual health facilities (e.g. hospitals and long-term care facilities).10-12

This article addresses the following questions:

• How can the maturity matrix be used to formulate a climate strategy, and track progress?

• How can organizations customize their climate strategy?

• How can learning health systems accelerate progress?

How to formulate a climate strategy, and track progress, with a maturity matrix

Unfortunately, while some policy guidance exists,13-16 there are limited resources for Canadian policy-makers for building roadmaps to climate resilience. Health leaders interested in climate resilience need to integrate a systems-thinking approach with carbon literacy and the ability to understand climate change projections, but this may require a large learning curve. Health professionals and policy-makers currently have limited training in carbon footprinting, climate change trajectories, and the range of human health impacts from climate change. Therefore, leaders are often under-equipped for assessing the magnitude of climate change impacts on their organizations and determining high-impact solutions. Further, health leaders are always contending with limited resources. Allocating resources to address climate risks is easily overlooked if not part of a strategic plan. Prioritizing climate action through a strategic plan (e.g. CHEO 17 and Vancouver Coastal Health Authority 18 ) helps to keep the spotlight on resource allocation for medium to long-term resilience in the midst of responding to immediate care delivery needs. Finally, even well-intentioned organizations with climate targets in place are at risk of (i) focusing only on either mitigation or adaptation, and not recognizing the co-benefits of undertaking both simultaneously, or (ii) overlooking the low-effort, high-reward actions such as their unique carbon hotspots or climate vulnerabilities. While there are some lengthy reports and complex tools that describe health system climate mitigation and adaptation, we argue that decision-makers require tools that provide a high-level overview of their organizations.

The Climate Resilience Maturity Matrix (Table 1) aims to simplify decision-makers’ strategic planning for climate change. Maturity matrices allow the synthesis of information from many sources7,8 to support organizational review, assessment, and decision-making related to climate change readiness. This tool is intended to serve six purposes: (1) consolidate key data, (2) provide a clear communication tool, (3) allow for objective rapid baselining, (4) enable system-level gap analysis, (5) facilitate comparability and transparency, and (6) support rapid learning cycles. Its conciseness is ideal for the purpose of an executive overview, and to facilitate conversations with internal domain experts (e.g. facilities, sustainability, procurement, and clinical staff).

Table 1.

Climate Resilience Maturity Matrix.

|

The design of the Climate Resilience Maturity Matrix is concise, allowing for easy comparisons to highlight and track progress. The maturity matrix incorporates four chronological phases, each with six domains of capacity providing an overview of parallel actions for both mitigation and adaptation. 20 The inclusion of separate columns for mitigation and adaptation makes progress and gaps explicit to encourage strategic planning in both areas.

The capacity domains for the maturity matrix are adapted from the WHO 2020 document WHO guidance for climate resilient and environmentally sustainable health care facilities 21 and the 2022 WHO document Measuring the Climate Resilience of Health Systems, 7 encompassing:

• Leadership and governance: strategic consideration and management of the scope and magnitude of climate-related stress and shocks to health systems now and in the future, and their incorporation into strategic health policies. 8

• Health workforce: adequate numbers of skilled human resources, with decent working conditions, empowered and informed to respond to environmental challenges. 7

• Water, sanitation, and waste: the sustainable and safe management of water, sanitation, and healthcare waste services. 10

• Energy: low carbon and resilient energy services. 7

• Infrastructure, technologies, and products: appropriate infrastructure, technologies, products, and processes, including health information systems. 7

• Service delivery in healthcare facilities. 7

A guidance document is provided at this link: https://greenhealthcare.ca/climate-change/resiliency/, which provides examples of types of actions that constitute a “check-mark” for each of these maturity matrix cells. This tool is meant to be flexible and customizable for organizations, and the examples in the guidance document are not expected to be fully comprehensive. If multiple actions have been performed in a cell of the matrix, multiple checkmarks can be added.

A further design feature of the Climate Resilience Maturity Matrix is the inclusion of phases, which encourages organizations to collect foundational information and develop detailed plans before committing resources and staff to implementing projects. The phases, adapted from the EPIS Implementation Framework,19,22 are (i) Exploration, (ii) Preparation, (iii) Implementation, and (iv) Continued improvement. Organizations new to sustainable health system planning should focus on the Exploration and Preparation phases, to focus their efforts on adequate planning and gathering baseline data while reducing their barrier to entry. Once a health system organization is further along on its net-zero pathway and climate adaptation roadmap, this tool provides a 10,000 ft. overview, helping staff members to map out activities that might have been overlooked (e.g. is a specific program overly focused on either mitigation/adaptation, is there limited staff engagement/training, is there a lack of implementation). Maturity matrices are used as annual tracking tools that provides a bridge between working-level project implementation and executives/steering committees’ strategic plans. To ensure it remains updated, consider assigning this task to an individual responsible for tracking.

How organizations can customize their climate strategy

Climate resiliency strategies are not one-size-fits-all and are improved by being customized to local contexts. For example, sites’ location can influence risks of flooding, wildfires, and extreme weather events. The Climate Atlas of Canada is a resource that is user-friendly and a good introduction for health leaders to appreciate their sites’ likely climate-related risks and vulnerabilities.23,24 The World Health Organization provides a comprehensive list of indicators to measure for hydrometeorological events, population, and health system outcomes. 7 These WHO factors that have varying climate-related impacts across organizations are summarized in Table 2, with the addition of relevant Canadian data sources. Vulnerability assessments and carbon footprint hotspot analysis both support the identification of specific weak points every organization would benefit from addressing.

Table 2.

Guidance for assessing climate-related impacts and population health risks at your site.

|

How learning health systems can accelerate progress

Continuous improvement of strategies for climate-resilient health system operation is critical for rapid and effective action. Small incremental and consistent improvements yield compounding large results. Therefore, continuous improvement is embedded in the maturity matrix’s fourth phase. Yet, it is difficult to sustain incremental and consistent learning. The process and culture required for such iterative feedback are well-supported by learning health systems. Learning health systems are characterized by the systematic gathering and application of evidence in real time to improve decision-making and guide care, along with an emphasis on the continuous assessment of outcomes and refinement of processes to create a feedback cycle of learning and improvement. 27 In such systems, research evidence, informatics, incentives, and culture are aligned for continuous improvement and innovation, with best practices seamlessly embedded in the delivery process and new knowledge captured as an integral by-product of the delivery experience. 28

Learning cycles enable health system policy-makers to use aggregated practice data and research evidence in their decision-making for continual analysis, self-critique, and innovation which will be crucial for supporting climate change-related policy making.28-32

Learning supports iterative risk management to ensure that climate-relevant policies are appropriately designed, refined, and implemented across a range of possible climate futures. 29 These learning cycles are vital for rapidly transforming health systems to be climate change resilient. A range of data (Table 3), including information on climatic and environmental conditions, health conditions, and response capacity, is needed to support learning cycles. 8 Crucially, the maturity matrix is aligned with the concept of learning health systems by including objective rapid baselining, thus enabling system-level gap analysis, and facilitating comparability and transparency. Better data collection and monitoring is a foundational step to derive indicators for rapid learning cycles for net-zero and climate resilience work in Canadian health system organizations.

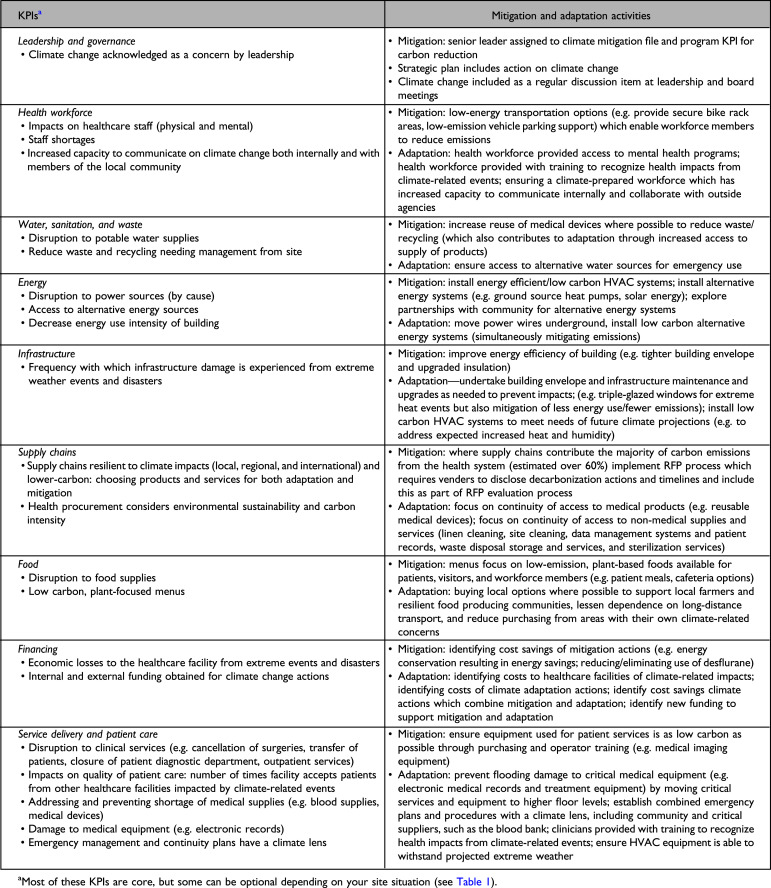

Table 3.

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for measuring impacts on health facilities and authorities.

|

Key performance indicators for health systems climate action transform raw data into meaningful feedback for learning health systems. Table 3 provides examples of mitigation and adaptation activities which can be undertaken to address specific key performance indicators. There are many instances where a specific mitigation action can also be adjusted to achieve an adaptation objective, which reinforces why mitigation and adaptation planning should be undertaken at the same time; for example, lowering the energy consumption of a facility will reduce GHGs for climate mitigation, which simultaneously makes that facility more adaptable to climate-related power outages, as it is easier to maintain its services via backup generators.

Learning health system innovations provide hope for accelerated climate resiliency for Canadian healthcare facilities, yet data availability and quality may prevent this (if not addressed). There is high data quality for health administrative data, such as the Canadian Institute for Health Information’s Discharge Abstract Database (DAD) which captures data on inpatient hospital discharges (deaths, sign-outs, and transfers), Hospital Morbidity Database (HMDB), Hospital Mental Health Database (HMHDB) and the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System (NACRS). Yet, these health administrative data and climatic data are in separate siloes, making it resource-intensive for individual sites to assess local patterns. An individual organization’s access to these data will depend on its own ability to retain submitted information and correlate the data to specific climate and environmental events. Provinces and territories can request CIHI to provide specific health data which can help with identifying climate change impacts, as some provinces have done for timely access to opioid data. These data will still need to be correlated with climate-related extreme weather events. Some data are simply not (yet) available, such as disaggregated, longitudinal data specific to the health of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis populations. 33 More broadly, systemic barriers, such as a fragmented health data foundation and lack of coordinated data governance, have prevented the timely and effective collection, sharing, and use of health data in Canada. 34 Efforts across health system levels to address this deficiency will support more effective responses to climate change. Further work is needed, at a national level, to synthesize health and climate patterns and make these data easily accessible.

Conclusion

In order to address climate-health risks and impacts, health systems around the world will have to develop and implement appropriate and effective mitigation and adaptation interventions. Working in collaboration with other sectors and with local communities is essential for addressing the social and environmental determinants of health which heavily influence population and individual health outcomes from climate change impacts. 35 Health leaders must be prepared to support both mitigation and adaptation efforts to build sustainable and resilient health systems. This work has to be continuously integrated into strategic and business continuity plans.

Referring in part to the steady intensification of climate change, Coeira has written, “If we wish to flourish or even just make do in this emerging reality, we will need to do more than create a learning health system that learns from the past. We must build a health system prepared to face that which cannot be foreseen.” 31 There will always be a degree of uncertainty associated with planning for future impacts on human health and infrastructure, given the complexities of climate change and the range of possible trajectories and future development choices. 29 This uncertainty, however, is not a reason to delay taking action. Policy-makers and professionals working in healthcare settings will need to continuously monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of their resilience planning to facilitate institutional learning that will enable rapid responses as climate-change evolution becomes more clear. 29 It is our hope that the Climate Resilience Maturity Matrix presented here will support decision-makers in health authorities and hospitals across Canada as they approach this vitally important work.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: Institutional Review Board approval was not required.

ORCID iDs

Denise Thomson https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4972-5331

Linda Varangu https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7207-6723

Richard J. Webster https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7682-8993

References

- 1.Haines A, Ebi K. The Imperative for Climate Action to Protect Health. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(3):263-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canadian Institute for Climate Choices . The Health Costs of Climate Change: How Canada Can Adapt, Prepare, and Save Lives. June 2021.

- 3.Eyquem JL, Feltmate B. Irreversible Extreme Heat: Protecting Canadians and Communities from a Lethal Future. Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation, University of Waterloo; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berry P, Enright P, Varangu L, et al. Adaptation and Health System Resilience. In: Berry P, Schnitter R, eds. Health of Canadians in a Changing Climate: Advancing our Knowledge for Action. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eckelman MJ, Sherman JD, MacNeill AJ. Life cycle environmental emissions and health damages from the Canadian healthcare system: An economic-environmental-epidemiological analysis. PLoS Med. 2018;15(7):e1002623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matthews JBR, Möller V, van Diemen R, et al. Annex VII: Glossary. In: Masson-Delmotte V, Zhai P, Pirani A, et al. , eds. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization . Measuring the Climate Resilience of Health Systems. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization . Operational framework for building climate resilient health systems. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Health Care without Harm . Climate Resilience for Health Care and Communities: Strategies and Case Studies. January2022. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fierlbeck K. Health Care in Canada: A Citizen's Guide to Policy and Politics. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marchildon G, Allin S, Merkur S. Health Systems in Transition: Canada, 3rd ed.Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lavis JN, ed Ontario's Health System: Key Insights for Engaged Citizens, Professionals and Policymakers. Hamilton, ON: McMaster Health Forum; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13.CASCADES . Climate Conscious Inhaler Prescribing Collaborative. Accessed January 5, 2023.https://cascadescanada.ca/courses/climate-conscious-inhaler-prescribing-collaborative/

- 14.Lower Mainland Facilities Management . Moving Towards Climate Resilient Facilities for Vancouver Coastal Health. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Health Canada . Extreme Heat Events Guidelines: Technical Guide for Health Care Workers. Ottawa, ON: Health Canada; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Health Canada . Communicating the Health Risks of Extreme Heat Events: Toolkit for Public Health and Emergency Management Officials. Ottawa, ON: Health Canada; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Webster R. Decarbonizing Canadian hospitals: CHEO as a case study for leadership, KPIs and engagement. Healthc Manage Forum. submitted.

- 18.Perkins+Will . Vancouver Coastal Health: St. Mary's Hospital Expansion and Renovation Case Study. Vancouver, BC: Perkins+Will; n.d. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moullin JC, Dickson KS, Stadnick NA, et al. Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) framework. In: Nilsen P, Birken SA, eds. Handbook on Implementation Science. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited; 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank . Climate-Smart Healthcare: Low-Carbon and Resilience Strategies for the Health Sector. Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization . WHO Guidance for Climate-Resilient and Environmentally Sustainable Health Care Facilities. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, Horwitz SM. Advancing a Conceptual Model of Evidence-Based Practice Implementation in Public Service Sectors. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(1):4-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prairie Climate Centre . Climate Atlas of Canada. Accessed January 10, 2023.https://climateatlas.ca/

- 24.Prairie Climate Centre . Connecting Climate Change and Health: A Guidebook of Health and Climate Change Content on the Climate Atlas of Canada. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayes K, Poland B. Addressing Mental Health in a Changing Climate: Incorporating Mental Health Indicators into Climate Change and Health Vulnerability and Adaptation Assessments. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(9):1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Environment Canada . Air Quality. Accessed February 12, 2023.https://weather.gc.ca/mainmenu/airquality_menu_e.html

- 27.Alberta SPOR SUPPORT Unit. Learning Health System. Accessed January 14, 2023.https://absporu.ca/learning-health-system/

- 28.Menear M, Blanchette MA, Demers-Payette O, Roy D. A framework for value-creating learning health systems. Health Res Policy Syst. 2019;17(1):79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ebi KL, Boyer C, Bowen KJ, Frumkin H, Hess J. Monitoring and evaluation indicators for climate change-related health impacts, risks, adaptation, and resilience. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(9):1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hess JJ, McDowell JZ, Luber G. Integrating climate change adaptation into public health practice: Using adaptive management to increase adaptive capacity and build resilience. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(2):171-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coiera E, Braithwaite J. Turbulence health systems: engineering a rapidly adaptive health system for times of crisis. BMJ Health Care Inform. 2021;28(1): e100363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abimbola S, Sheikh K, Abimbola S. Strong health systems are learning health systems. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2022;2(3):e0000229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health (NCCIH) . Climate Change and Indigenous Peoples' Health in Canada. In: Berry P, Schnitter R, eds. Health of Canadians in a Changing Climate: Advancing our Knowledge for Action. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goel V, McGrail K. Modernize the Healthcare System: Stewardship of a Strong Health Data Foundation. Healthc Pap. 2022;20(3):61-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ebi KL, Vanos J, Baldwin JW, et al. Extreme Weather and Climate Change: Population Health and Health System Implications. Annu Rev Public Health. 2021;42(1):293-315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]