Abstract

Scaffolds delivered to injured spinal cords to stimulate axon connectivity often match the anisotropy of native tissue using guidance cues along the rostral-caudal axis, but current approaches do not mimic the heterogeneity of host tissue mechanics. Although white and gray matter have different mechanical properties, it remains unclear whether tissue mechanics also vary along the length of the cord. Mechanical testing performed in this study indicates that bulk spinal cord mechanics do differ along anatomical level and that these differences are caused by variations in the ratio of white and gray matter. These results suggest that scaffolds recreating the heterogeneity of spinal cord tissue mechanics must account for the disparity between gray and white matter. Digital light processing (DLP) provides a means to mimic spinal cord topology, but has previously been limited to printing homogeneous mechanical properties. We describe a means to modify DLP to print scaffolds that mimic spinal cord mechanical heterogeneity caused by variation in the ratio of white and gray matter, which improves axon infiltration compared to controls exhibiting homogeneous mechanical properties. These results demonstrate that scaffolds matching the mechanical heterogeneity of white and gray matter improve the effectiveness of biomaterials transplanted within the injured spinal cord.

Keywords: 3D-printing, digital light processing, rheology, spinal cord injury, axon regeneration, tissue engineering

Introduction

A potential benefit of transplanting bioengineered scaffolds is the delivery of a matrix with mechanical properties that mimic the host tissue, but the mechanics of native tissue are often heterogeneous and difficult to characterize. In particular, our understanding of the mechanical properties of the central nervous system (CNS), specifically the spinal cord, has primarily been informed by macroscale measurements[6–8]. These studies have shown that CNS mechanics are heterogenous via tensile, shear, compression testing[9,10] and magnetic resonance elastography[11,12]. In order to supplement bulk approaches, atomic force microscopy (AFM) has proven a useful tool to measure the stiffness of the spinal cord with higher spatial resolution. However, published data are contradictory regarding the difference in mechanical properties between white and gray matter[13–15]. Physiologically, white and gray matter exhibit differences in cellular and matrix composition: white matter mainly consists of glial cells and myelinated axons aligned along the rostral-caudal direction, whereas gray matter is mostly comprised of neuronal cell bodies, which likely alters its mechanical properties. Moreover, the complex and variable environment of a spinal cord injury (SCI) is known to alter cord mechanics[16]. Therefore, transplanting a scaffold that mimics the mechanical heterogeneity of white and gray matter may improve axon infiltration at the site of spinal cord injury.

Several studies have interrogated the effect of injury on the mechanical properties of the spinal cord. In the aftermath of a spinal cord injury, an influx of inflammatory cytokines and localized ischemia impose a biochemical barrier, while the formation of a glial scar alters the composition and the mechanical properties of the cord tissue that mitigates axon growth [4,5]. Studies using AFM to characterize cord mechanics after injury indicate that the tissue undergoes an initial decrease in stiffness in a complex process that involves alteration to the cord extracellular matrix, cell death, and axon retraction and demyelination. Therefore, axons attempting to bridge the site of CNS injuries face an insurmountable challenge, in part due to the body’s own response to the damage. One potential treatment strategy currently being investigated in clinical trials is the use of implantable scaffolds to aid axon growth at the site of injury.

Bioengineered scaffolds with a wide array of mechanical properties have previously been used in spinal cord injury. The overall goal of transplanted hydrogels or conduits is to bridge the injured area by facilitating axon connectivity and eventual functional recovery for patients. Previously used scaffolds in animal studies and human clinical trials incorporate a wide variety of biomaterials including collagen [17], polycaprolactone[18–21], electrospun fibers[22–24], fibrin [25–27] and can either be injected[28,29] or delivered as solid conduits[17]. These approaches use several repair strategies including delivery of neurotrophic factors or cells [30], implementation of a conductive microenvironment using electrically active materials[31], and providing guidance cues by anisotropic topologies including cylindrical voids [19,32,33]. Considerations for biomaterials used in previous spinal cord scaffolds include biocompatibility, degradability, permissivity to infiltrating axons from the host, and matching approximate, bulk mechanical properties of the spinal cord [34]. Yet, none of the previous approaches tune the mechanical heterogeneity within the construct as a potential repair strategy for spinal cord regeneration.

3D-printed scaffolds provide a means to fabricate heterogeneous mechanical properties that match native spinal cord tissue. Previous approaches have demonstrated that photocrosslinkable hydrogels can be used in 3D-printed systems that can mimic the anisotropy of various tissues including skeletal muscle [35], bone [36–38], cartilage [39–42], and neural tissue [43,44]. 3D-printing has also been used to fabricate spinal cord conduits that feature voids aligned in the rostral-caudal to mimic specific axon tracts [45]. However, the scaffolds in that particular study exhibited an elastic modulus exceeding 200 kPa, which far surpasses the mechanical properties of the surrounding spinal cord tissue and precludes the ability to differentiate between the stiffness of white and gray matter. Recent innovations in 3D-printing approach, specifically digital light printing (DLP) have been used to create complex topologies within tunable 3D scaffolds that overcomes the limitations of previous strategies [46,47]. This process can be used to control and guide the growth of axons in scaffolds with heterogeneous mechanical properties to facilitate both infiltration and outgrowth from the site of injury. In this study, an array of macroscale and microscale mechanical tests are used to characterize the mechanical properties of native spinal cord tissue, which then inform a DLP-based approach to mimic the mechanical heterogeneity in transplantable scaffolds.

Materials and methods

Solution preparation

Dissecting and measuring artificial cerebrospinal fluids were formulated to maintain the viability of isolated spinal cords using previous methods [48,49]. Briefly, dissecting artificial cerebrospinal fluid (d-aCSF) was supplemented with 191 mM sucrose, 0.75 mM K-gluconate, 1.25 mM KH2PO4, 26 mM NaHCO3, 4 mM MgSO4, 1 mM CaCl2, 20 mM glucose, 2 mM kynurenic acid, 1 mM (+)-sodium L-ascorbate, 5 mM ethyl pyruvate, 3 mM myo-inositol, and 2 mM NaOH. Additionally, measuring artificial cerebrospinal fluid (m-aCSF) was composed of 121 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 25 mM NaHCO3, 1.1 mM MgCl2, 2.2 mM CaCl2, 15 mM glucose, 1 mM (+)-sodium L-ascorbate, 5 mM ethyl pyruvate, and 3 mM myo-inositol. The resulting pH of these solutions was ~7.3. All the above reagents were purchased from VWR.

Spinal cord preparation

Bovine spinal cords were severed at the C3 level and isolated directly into quart-sized containers of ice-cold dissecting artificial cerebrospinal fluid (d-aCSF) at Bringhurst Meats (Berlin, NJ). After measuring the lengths of the cords, each tissue was divided into three regions: cervical (between 31 and 35 inches from caudal end), lumbar (between 20 and 26 inches from caudal), and sacral (10 inches from caudal). All regions were cut along the transverse anatomical plane in approximately 5–6-mm slices, and then immersed in m-aCSF for testing. For mechanical testing of rat cords, an established technique for hydraulic extrusion was used on male Sprague Dawley rats provided by David Li of Dr. Rebecca Wells laboratory at the University of Pennsylvania within an hour of sacrifice [50]. The cords were cut into approximately 5–6-mm slices and adhered to a 60-mm Petri dish filled with m-aCSF.

Spinal cord macroscale mechanical characterization

All spinal cord mechanics were examined within 1 to 2 hours after extraction and experiments were performed within 6 hours, as previous studies have shown that cords preserved in aCSF maintain their mechanical properties over this timespan [48]. The local mechanics of the gray and white matter were examined using AFM. Spinal cord sections were fixed to the petri dishes using transglutaminase that has been shown as a tissue adhesive [51] and fully embedded in m-aCSF during these measurements. AFM measurements were taken in triplicates in regions of both gray and white matter using a 20-μm diameter silicon spherical tip with a cantilever spring constant of 0.6 N/m.

Rheology was conducted at several levels of compressive strain to characterize the macroscopic mechanical properties of the cord at different regions. Measurements were conducted on a rheometer (Kinexus) with a 20-mm parallel attachment. During rheological measurements, m-aCSF was pipetted around the tissue to prevent the cord from drying out. The gap was set with respect to the height of each spinal cord section. The bulk mechanical properties of the cords were evaluated by measuring the shear modulus at a steady frequency of 1 Hz and 1% strain for 90 seconds. The test was repeated for successive compression steps of 100 μm.

A Kibron tensiometer was used to measure the relaxation effects of the gray and white matter of bovine spinal cords. Tissue sections were submerged in m-aCSF during relaxation measurements. A 500-μm probe was lowered in the gray and white matter to interrogate the relaxation profiles within each matter region. The relaxation factors were calculated by measuring the decay in force with time after indentation.

Synthesis of polymer and photoinitiator

The polymers and initiators for the prehydrogel solutions, including gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) and lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP), were synthesized as previously described [46]. In brief, GelMA was synthesized through dropwise addition of methacrylic anhydride to 10 wt% gelatin (Sigma, derived from porcine skin; type A; gel strength 300) in carbonate/bicarbonate buffer for 4 hours at 50–55 °C, then precipitated in ethanol. The precipitate was allowed to dry for multiple days before resuspension at 20 wt% in PBS. GelMA was sterilized with 0.22 μm filters and stock solutions were aliquoted then stored at −20 °C until use. LAP was prepared by the reaction of dimethyl phenylphosphinite and 2,3,6-trimethylbenzoyl chloride under argon overnight at room temperature. Then 4 M excess lithium bromide dissolved in 2-butanone was added to the reaction mixture. The solution was heated to 50 °C for precipitation (~10–30 min), cooled to room temperature for 4 hours then filtered with 2-butanone and diethyl ether. The resulting precipitate was allowed to dry for several days before storing under nitrogen at 4 °C until use. Stock solutions were prepared at 200 mM in PBS, sterile filtered, and protected from light until use.

Preparation of 3D Printed Scaffolds

For all fabrication of hydrogel scaffolds, prehydrogel mixtures were prepared containing 15 wt% GelMA, 17 mM LAP, 2.255 mM tartrazine photoabsorber, and 10% glycerol in sterile 1x PBS. The Volumetric-α Bioprinter used in fabrication was previously developed by the Jordan Miller lab and Volumetric [46]. This stereolithography-based 3D printer used a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) coated Petri dish as a vat for the prehydrogel mixture and a build platform with a bonded frosted-glass slide onto which the cured gel would attach during printing. After transferring the prehydrogel solution into the vat, the build platform was then lowered to the first fabrication layer position to start printing. A custom Matlab script was used to create the 2D photomasks from a 3D model. Grayscale patterning was the method used for outputting a hydrogel with the desired mechanical heterogeneity of localized regions for the study. The grayscale patterning uses light intensity values between 0–100%, representing black to white, to change the extent of polymerization of the hydrogel. This process included an analysis of the 3-dimensional model, separating them into even 50-μm sections in the z-direction, then applying the grayscaled pattern on top of the resulting slices to create the final photomasks. A built-in software on the printer was used to import the photomask and control the apparatus by sending GCode commands for vertical movement of the build platform and images to the projector. The photomasks are projected in sequence for a set exposure time of 14.5 seconds and light intensity of 20 mW/cm2 (at 100% grayscale) for each projection to build the 3D hydrogel object through layer-by-layer photopolymerization. After printing was complete, the 3D fabricated hydrogels were removed from the glass slide of the build platform with a razor and equilibrated in multiple sterile PBS washes. The 3D models ofT10 rat thoracic regions of the spinal cord were created in Blender. The grayscale light intensity value for the simulated white matter was 75% and the gray matter was 100%. These intensity values were chosen to create substantial heterogeneity in the scaffold stiffness without sacrificing the fidelity of the print. The hydrogels were printed in groupings of 8.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The microstructure of 3D-printed GelMA hydrogels was examined using a scanning electron microscope (FEI SEM). The scaffolds were frozen with liquid nitrogen and lyophilized for 2 hours. The freeze-dried samples were cut in cross-section and sputter coated for 30 seconds per sample. The porosity was analyzed by measuring pore diameters with the measure function in ImageJ.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM)

For atomic force microscopy, raster scans (100 μm × 100 μm) were performed to generate force-distance curves on regions within the regions of gray matter, white matter, and regions that contain both the gray and white matter. The scaffolds were submerged in a-CSF during the AFM experiments. Measurements were employed using a 20-μm silicon spherical tip with a spring constant of 0.6 N/m.

Spinal cord surgery and transplantation

Animal surgeries were conducted at the Drexel University Queen Lane Medical Campus. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Drexel University College of Medicine (approval number: 20938 21–26) and these experiments were performed according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Nine female Sprague-Dawley rats (225–250 g) were housed with a 12-h/12-h light/dark cycle in this study. These rats were administered with 5% of isoflurane until unconscious and the concentration of anesthesia was reduced to 3% during surgery. To create the transection spinal cord injury model, a laminectomy was performed at the thoracic 10 (T10) and aspiration was performed to remove the tenth level of the thoracic leaving a cavity of approximate dimensions of 2 × 2 × 2 mm. Upon transplantation, two scaffold conditions were employed: 1) homogeneous hydrogels that exhibit the same mechanics within the gray and white matter and 2) heterogeneous scaffolds that mimic the differences in gray and white matter. Muscles and skin were sutured and closed with clips. Buprenex (0.015 – 0.02 mg/kg) was subcutaneously administered after the surgery. Bladder was manually expressed twice a day until the end of the experiment. Animals were sacrificed 2 weeks after peptide injections.

Bovine spinal cord immunohistochemistry

Bovine spinal cord sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde on ice for 40 minutes. After fixation, the spinal sections were embedded in OCT compound and snap-frozen to cryopreserve the tissue and stored at −80 °C until processing. Each tissue region was sectioned at 20 μm thick in a cryostat and mounted onto gelatin-coated slides. The slides were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and sections were blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Anti-myelin primary antibodies (VWR) were diluted at a ratio of 1:200 in dilution buffer consisted of 1% BSA (VWR), 0.3% Triton X-100 (Sigma), and 0.01 sodium azide (VWR) and incubated overnight at 2 to 8 °C. The slides were washed thoroughly with PBS and secondary antibodies were incubated at room temperature for 60 minutes at a ratio of 1:500. DAPI stains were added to each slide for an addition incubation time of 5 minutes at room temperature. Finally, sections were washed and mounted in anti-fade mounting media.

Rat spinal cord immunohistology

Two weeks following transplantations, rats were overdosed with Euthasol (J. A. Webster) and transcardially perfused with 100 mL of 0.9% saline and 500 mL of 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer. Spinal cords were removed and incubated in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight and cryoprotected with 30% sucrose/0.1 M phosphate buffer at 4°C for 3 days. The cords were transferred to M1 medium and cryosectioned with thicknesses of 20 μm. Sagittal sections were separated into six sets (approximately 10 – 15 mm in length) with gelatin coated glass slides. Adjacent sections on glass slides were approximately 120-μm spaced apart within the cord and the histological slides were kept at −20 °C.

Histological sections were thoroughly washed and blocked with 10% goat or donkey serum, for 1 hour prior to immunohistochemical staining. Sections were selected for immunohistochemical staining using primary antibodies Tuj (1:500, Covance) for general axon growth, GFAP (1:1000, Chemicon) for glial scar formation, and CGRP (1:2000, Peninsula) for sensory axons. These sections were incubated in primary antibodies overnight at room temperature followed by incubating in species-specific secondary antibodies (goat anti-mouse, donkey anti-goat, or goat anti-rabbit conjugated to FITC or rhodamine, 1:1000, Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 2 hours at room temperature. Sections were cover-slipped with fluoromount-G with DAPI (SouthernBiotech).

Confocal microscopy

Immunohistological sections of the bovine spinal cord (thickness: 20 μm) were imaged on a Nikon A1 laser scanning confocal microscope to generate z-stacks (approximately 10 slices with a 2-μm step size) in the Nikon Elements software. Image quantification was performed by normalizing the intensity of either myelin or laminin stains within 100 × 100 μm2 measured areas. A macro in FIJI was written to automate image processing and quantification over the directory of images. Specifically the Huang Dark method was used to identify the stain-positive region to quantify the protein of interest and normalized against the total area of the section measured. Cell nuclei quantification was conducted using moments dark thresholding followed by water shedding to separate the nuclei. Particle analysis was used to count nuclei with diameters of 5–10 μm with a circularity greater than 0.75. The number of cell nuclei was normalized to the area of each scan (1 mm2). Myelin quantification was performed by normalizing the intensity of myelin stains within 1 mm2 measured areas. For transplantation analysis, at least four adjacent sections on each slide (approximately 360 μm in height) from each animal were scanned and analyzed. A 4X objective was used to provide lower magnification images to observe whether axons infiltrated through the rostral end and extend towards the caudal end. 10X and 20X objectives were used to quantify the number of infiltration axons through the prefabricated channels in the scaffolds. Tuj+ axons and CGRP fibers inside the scaffolds were quantified using the multi-point tool in ImageJ. Infiltration distance was analyzed using the measure tool in ImageJ to determine the lengths of which axons infiltrate.

Statistics

One-way ANOVA and post-hoc Tukey’s HSD tests were performed to calculate statistical significance unless stated otherwise. Statistical analysis of mechanical heterogeneity was calculated using a Welch Two Sample t-test, assuming normal distributions with unequal variances between groups between the gray and white matter of the scaffolds. Significant differences were denoted with p-values less than 0.05. In vivo analysis (9 animals total) was averaged from 3 histological sections per animal. Three different bovine spinal cords with three sections from each level (cervical, lumbar and sacral) were examined for rheology, tensiometry and atomic force microscopy (AFM). Regarding the tensiometer and AFM experiments, at least 5 measurements were recorded from both the gray and white matter and 3 sections from each level were examined on the rheometer.

Results

I. Microstructural characterization of spinal cord mechanical properties

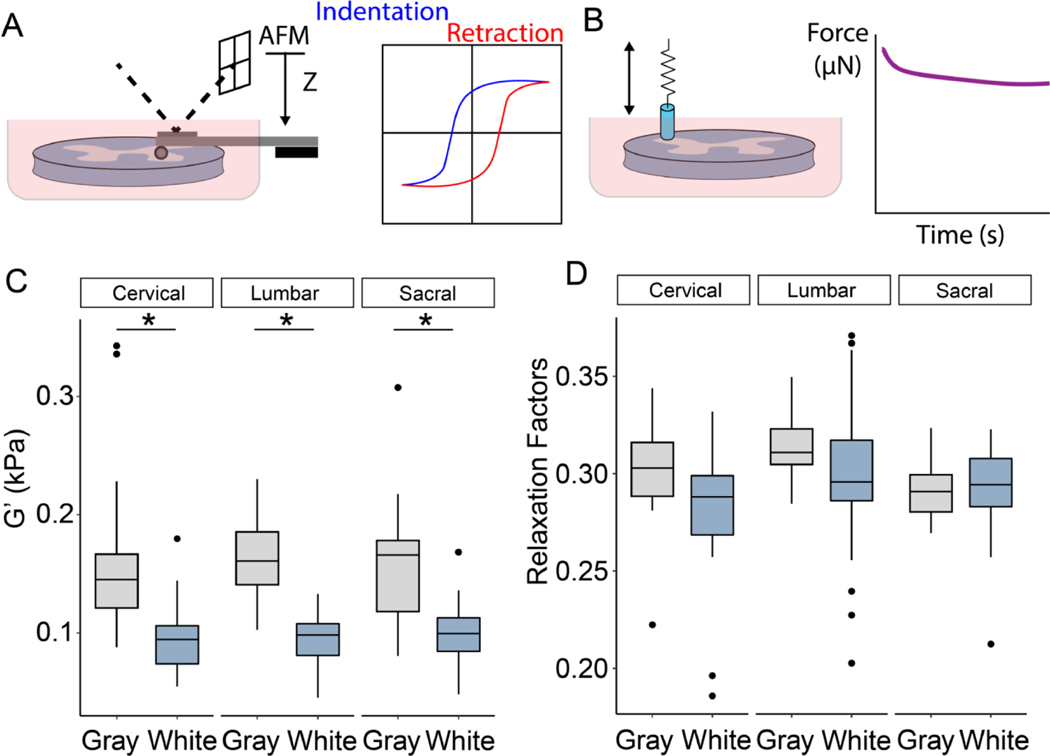

In order to examine the heterogeneity of spinal cord tissue, initial experiments using AFM and tensiometry were conducted to interrogate differences in gray and white matter along the transverse anatomical plane. Previous experiments have found that the gray matter is stiffer than white matter in all anatomical plans (coronal, sagittal and transverse) [48], though there is also conflicting evidence that no significant different between gray and white matter exists [13]. To clarify the discrepancies between these studies, AFM and tensiometry experiments were performed on the spinal cord (Fig. 1A,B). The tissue was divided into three regions: sacral, thoracic/lumbar, and cervical to assess whether anatomical level affected the mechanical properties of the cord. AFM, which has been used previously to characterize cord mechanics [52], revealed that the gray matter exhibits significant higher elastic moduli compared to white matter, though there were no statistical differences between the three levels (Fig. 1C). Post-hoc Tukey tests indicated significant differences between gray and white matter at each level. Tensiometry examined the relaxation factors of both gray and white matter by measuring stress relaxation following indentation. Figure 1D shows the relaxation factors for both gray and white matter in all three regions, and two-factor ANOVAs revealed a statistical difference between the gray and white matter, though again there is no difference between levels. Taken together, these results presented here indicate that the gray matter exhibits stiffer and more viscoelastic mechanics compared to white matter, and that there is no difference in the microstructural mechanical properties of gray and white matter along the length of the cord. To verify that this mechanical heterogeneity also exists within the rat spinal cord, AFM was conducted on cervical level slices of the rat cord and indicated a significantly higher elastic modulus in the gray matter region compared to the surrounding white matter region (Supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Microstructural mechanical properties of bovine spinal cord tissues. (A,B) Schematic of atomic force microscopy (AFM) and tensiometer. (C) Measurements of gray and white matter using AFM. (D) Relaxation factors of gray and white matter via tensiometer. The box plots depict the median, 25 and 75 percentiles, and the whiskers represent 1.5x the interquartile range. *p < 0.05 (n = 5 measurements per matter with 3 sections from each level: cervical, lumbar, and sacral stemming from 3 animals).

II. Macrostructural mechanical properties of spinal cord tissue

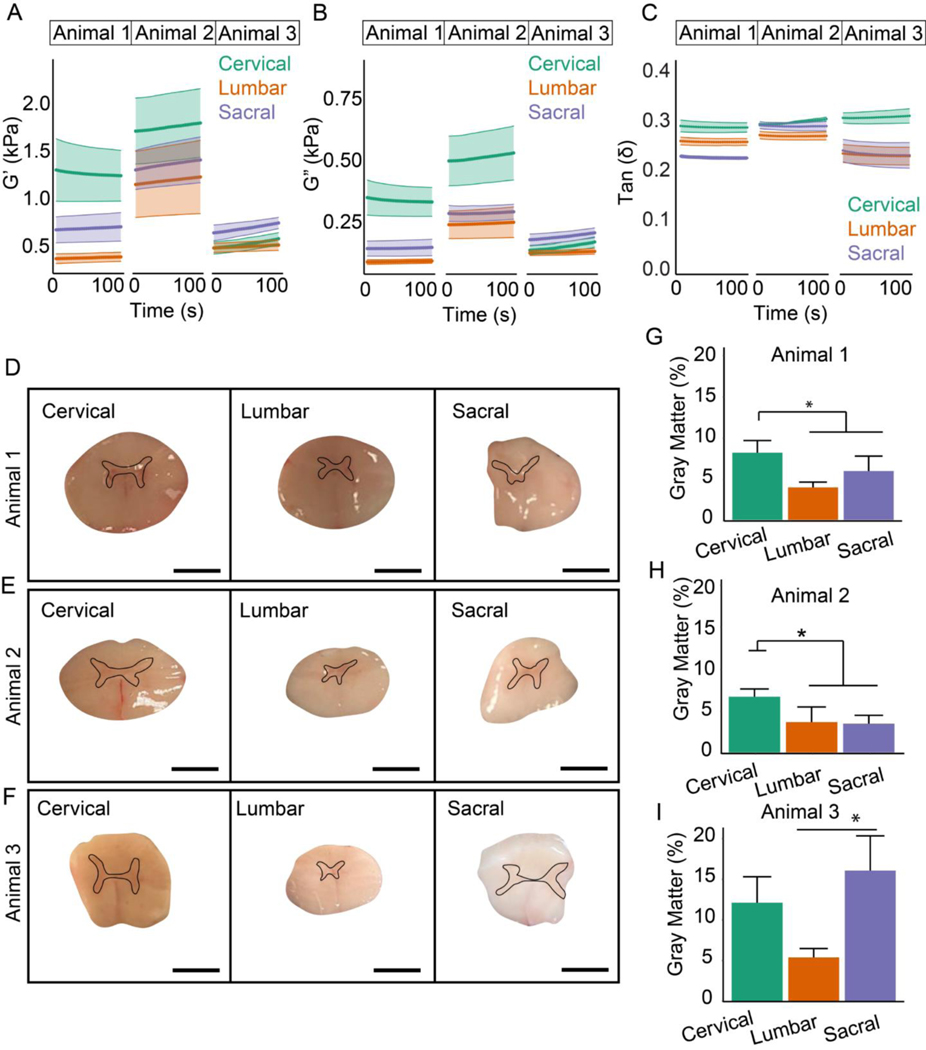

Rheology was conducted to characterize bulk mechanics of the cord at cervical, lumbar, and sacral levels. Three different sections from each level (cervical, lumbar and sacral) from three separate bovine spinal cords were examined with rheology (nine total samples). Given the results of the AFM testing, these experiments tested the hypothesis that the disparity in bulk mechanical properties of anatomical levels is due to differences in the ratio of gray-to-white matter. Therefore, shear storage and loss moduli as well as cross-sectional area of gray and white matter were measured in 5–6-mm thick transverse spinal cord sections taken from different levels. Figures 2A–C show rheological experiments performed on three different bovine spinal cords. The highest storage and loss moduli were measured in cervical regions of two of the animals and in the sacral region in the third animal. Moreover, Supplemental Figure 2 displays the sections were tested at increasing magnitudes of compressive strain to demonstrate that the cord exhibits the compression stiffening observed in other tissues [53,54]. In order to reconcile the bulk testing with the AFM measurements that found no difference in gray or white matter along the cord, transverse spinal cord sections (Fig. 2D–F) were imaged and the percentage of gray matter in the cross-section was expressed as a percentage of the total area (Fig. 2G–I). Figure 2G provides the rheological measurements for animal 1, Figure 2H corresponds to animal 2 and Figure 2I represents the data from animal 3 (all measurements were performed in triplicate). The gray matter in the cervical region was significantly higher compared to the lumbar and sacral regions in the experiment from the first two cords, and highest in the sacral region in the third animal. Therefore, these results suggest that bulk rheological properties along the cord are determined by differences in the ratio of gray to white matter in the cross-section of the cord.

Figure 2.

Characterization of macrostructural mechanical properties of bovine spinal cord tissues. Rheological experiments of cervical, lumbar and sacral regions of spinal cords from 3 animals showing (A) storage modulus, (B) loss modulus and (C) tan(δ). Data presented as mean ± s.e.m. (D-F) Images of spinal cords and (G-I) quantification of gray-to-white matter ratios for each animal. The black lines indicate the representative regions of quantified gray matter. Data presented as mean ± s.d. *p < 0.05 (n = 3 spinal sections from per level: cervical, lumbar, and sacral stemming from 3 animals).

III. Microstructural analysis of gray and white matter

In order to provide insight into structural differences between gray and white matter that give rise to mechanical heterogeneity, immunohistochemistry was performed to examine differences in cell nuclei, myelin, and laminin expression in both regions along the different levels of the cord. These measurements also provided an opportunity to assess whether the cords undergo substantial demyelination or changes in matrix content over the course of the mechanical experiments. Figure 3 shows cervical, lumbar, and sacral sections fixed at the beginning (Fig. 3A,C,E) and 6 hours later at the end (Fig. 3B,D,F) of the mechanical characterization experiments. Quantification of DAPI, myelin, and laminin indicated significant differences between the white and gray matter regions at all the levels. There was significantly higher DAPI staining in gray compared to white matter at both the beginning and end of the experiment (Fig. 3G), which is consistent with the results of a previous study [48]. The myelin and laminin also exhibited a higher intensity in the gray matter ( Figs. 3H,I). In the white matter, the anti-laminin revealed a network pattern that may highlight the vascular bed, due to the prevalence of laminin in the basement membrane. The gray matter appeared much denser in both the myelin and laminin staining. Importantly, there was no significant difference between DAPI staining nor expression of myelin and laminin at the beginning of the experiment compared to the end of the experiment, verifying that the tissue did not undergo substantial degradation during the mechanical testing.

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical analysis of gray and white matter. (A) Images of cervical sections treated with anti-myelin and anti-laminin antibodies after isolation and (B) at a 6-hour time point. (C) Images of lumbar sections treated with anti-myelin and anti-laminin antibodies after isolation and (D) at a 6-hour time point. (E) Images of sacral sections treated with anti-myelin and anti-laminin antibodies after isolation and (F) at a 6-hour time point. Quantification of DAPI (G), myelin (H), and laminin (I) within the gray and white matter at both the beginning and end of experiment for all cord levels. The box plots depict the median, 25 and 75 percentiles, and the whiskers represent 1.5x the interquartile range. *p < 0.05 (n = 3 measurements per matter with 3 sections from each region: cervical, lumbar, and sacral at each time point).

IV. 3D-printing scaffolds with heterogeneous mechanical properties

A novel DLP approach was developed to fabricate a scaffold that mimicked the difference in stiffness between gray and white regions observed by microstructural mechanical testing of the bovine spinal cord. Figure 4A shows a schematic of the printing method, which applies varying levels of light intensity to a single z-plane using a grayscale mask. Grayscale patterns were created to alter light intensity values between 0–100%, representing black to white, to modulate the extent of polymerization of the GelMA hydrogel. In order to verify this approach, test patterns of alternating intensity were printed in square blocks. Figure 4B shows the grayscale mask used for these preliminary prints, with stripes of 1-mm thickness in a 10 × 10 × 3-mm block. Tensiometry was used to validate differences in mechanical properties. Quantification of this data and subsequent statistical analysis reveal significant differences between each stripe, demonstrating that the regions exposed to higher light intensities exhibit stiffer mechanics than the regions with lower light intensities (Fig. 4C). These results verify that heterogeneity can be achieved within the 3D-printed scaffolds to mimic the difference in stiffness between gray and white matter regions.

Figure 4.

3D-printing scaffolds with heterogeneity. (A) Schematic of grayscale patterns to facilitate printing of a single plane with varying levels of light intensity. (B) Preliminary 3D-printed hydrogels with heterogeneity by using a mask with alternating light intensity. (C) Mechanical quantification of each stripe within the 3D-printed hydrogels. Data presented as mean ± s.d. *p < 0.05 (n = 3, one measurement per stripe from 3 different gels).

V. Mechanical characterization of 3D-printed scaffolds for spinal cord injury

Having validated the approach to 3D-print scaffolds with heterogeneous mechanical properties, hydrogels were printed to mimic a rat T10 geometry. Homogenous scaffolds were exposed with the same light intensity across the entire cross-section in both the “gray” and “white” regions, while heterogeneous scaffolds were printed with different intensity light between the two regions. Mechanical and microstructural assays were conducted to characterize these scaffolds. Previous studies have shown that the stiffening effect in photocrosslinkable hydrogels decreases dextran diffusivity [55], with the porosity of these scaffolds examined using a scanning electron microscope (SEM). Figure 5A displays images of the scaffold within the gray and white matter regions in a homogenous scaffold (printed at the same light intensity used for the white matter of the heterogeneous scaffold) and one heterogeneous scaffold. Quantification demonstrated that the pore diameters were decreased in the simulated gray matter of the heterogeneous scaffold (Fig. 5B), which is consistent with a previous study on modifying GelMA with altered light intensity [56]. In order to further validate the difference between simulated white and gray matter, compression tests were performed on bulk hydrogels exposed to varying light intensity. Compression tests revealed that hydrogels exposed to the light intensity used to create the gray matter region exhibited a significantly higher elastic modulus compared to hydrogels representing white matter (Fig. 5C). Nonetheless, the compression indicated no significant difference in the Poisson ratio of the hydrogels: both white and gray matter were nearly incompressible (v ~ 0.4) (Fig. 5D). Having validated that there is a difference between the mechanical properties of scaffolds exposed to different pixel intensities, images of the homogeneous and heterogenous scaffolds were obtained to demonstrate that the varying stiffness did not affect the geometry of the scaffold (Fig. 5E). The scaffolds contained cylindrical channels with diameters of 325 μm to guide axonal infiltration into the scaffold due to their established ability to align axons along the rostral-caudal direction [19,45]. AFM raster scans were performed on the scaffold surface to provide two-dimensional elasticity maps. Three different printing conditions were used: homogenous stiffness printed at 75% intensity (simulated white matter), homogenous stiffness printed at 100% intensity (simulated gray matter), and heterogenous stiffness with varying light intensity in the gray and white regions. Figures 5F–H display heatmaps of the elastic moduli in both the homogeneous and heterogeneous scaffolds. Two-factor ANOVAs with post-hoc Tukey tests revealed that the gray matter within the heterogeneous scaffolds exhibited significantly higher elastic moduli than the surrounding white matter and the homogeneous hydrogels printed at 75% intensity. There was no significant difference between the stiffness of the gray matter in the heterogeneous scaffolds and the homogeneous scaffolds printed at 100% intensity (Fig. 5I). Taken together, the data presented here demonstrate that mechanical heterogeneity can be achieved in spinal cord scaffolds.

Figure 5.

Interrogation of 3D-printed heterogeneous scaffolds. (A) SEM images of the gray and white matter in homogeneous and heterogeneous hydrogels. (B) Quantification of porosity within the scaffolds. (C) Mechanical testing of 3D-printed scaffolds that exhibit the mechanics of gray matter and white matter. (D) Poisson ratios of 3D-printed scaffolds. (E) Brightfield images of 3D-printed scaffolds that mimic the T10 level of rat’s spinal cord and exhibit homogeneous or heterogeneous mechanics within the constructs. Elasticity heatmaps of homogeneous white (F), homogeneous gray (G) and heterogeneous (H) scaffolds. (I) Young’s moduli in both the gray and white matter within homogeneous and heterogeneous hydrogels. The data in the bar graphs are represented as mean ± s.d. The box plots depict the median, 25 and 75 percentiles, and the whiskers represent 1.5x the interquartile range. Scale = 500 μm. *p < 0.05 (n = 3 scaffolds with at least 6 measurements from each matter).

VI. Assessing axon infiltration into scaffolds with heterogeneous mechanical properties

Transplantation studies were then conducted to determine whether the heterogeneous scaffolds would elicit increased axon infiltration compared to homogeneous controls. Both heterogeneous scaffolds and homogeneous scaffolds of stiffnesses matching the heterogeneous scaffold were transplanted into a model of acute spinal cord injury. Figure 6A displays a schematic of hydrogel fabrication, injury model, and transplantation of the T10 scaffolds. Immunohistochemistry examined the infiltration of axons into the channels patterned in the scaffold two weeks post-transplantation. The presence of ascending sensory-specific tracts was measured using calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), a peptide widely expressed in sensory axons [57] (Fig. 6B). Quantification of CGRP+ fibers demonstrated that heterogeneous scaffolds significantly augmented the infiltration of sensory axons compared to both homogeneous conditions (Fig. 6C). To further assess axon infiltration into the scaffolds, both the rostral and caudal regions of the transplanted scaffolds were examined for the presence of beta-tubulin III (Tuj) fibers. Figure 6D displays the presence of Tuj+ axons located only in the rostral region of the scaffolds with homogeneous mechanics matching the “white matter” of the heterogeneous scaffold. Figure 6E indicates a similar response in the homogeneous scaffold matching the grey matter. However, the infiltration and outgrowth of Tuj+ fibers were observed in both the rostral and caudal sections of the heterogeneous scaffolds (Fig. 6F), demonstrating that the mechanical heterogeneity stimulated neuronal regeneration. In order to determine whether the heterogeneous scaffold stimulated increased axon growth, quantification of Tuj fibers was evaluated in the white matter regions of both scaffold types and indicated that the heterogeneous scaffolds significantly promoted the growth of Tuj+ fibers (Fig. 6G) and stimulated the infiltration distance compared to the homogeneous hydrogels (Fig. 6H). The heterogeneous scaffolds also exhibited increased infiltration of motor specific (5-HT+) and regenerating (RT-97+) axons compared to homogeneous controls (Supplemental Figure 3). The scar area, as indicated by GFAP positive regions, was not substantially different between conditions (Supplemental Figure 4). Overall, these results demonstrate 3D-printed scaffolds with heterogeneous mechanical properties matching the anisotropy of host tissue have beneficial effects on the infiltration and regrowth of axons.

Figure 6.

Examination of axon infiltration post-transplantation. (A) Schematic showing scaffold fabrication to transplantation. (B,C) Immunofluorescence and quantification of CGRP+ axons infiltrating the channels of both the homogeneous and heterogeneous scaffolds. (D,E,F) Infiltration of Tuj+ fibers within the cylindrical channels in three scaffold conditions. Quantification of (G) Tuj+ fibers and (H) infiltrating distance in homogeneous and heterogeneous scaffolds. The data in the bar graphs are represented as mean ± s.d. *p < 0.05 (n = 3 histological slides for each condition).

Discussion

The results demonstrate that mimicking the stiffness disparity between gray and white matter in an implantable scaffold encourages axon growth at the site of a rat spinal cord transection injury. Previous studies have demonstrated that multicellular migration is enhanced along a gradient in the rigidity of the extracellular matrix, referred to as durotaxis, in both in vivo [58] and in vitro [59,60] microenvironments. In contrast, the stiffness gradient used here is orthogonal to the direction of axonal growth, though this gradient is more representative of native spinal cord tissue. The mechanical testing conducted in this study indicates that the inner gray matter is stiffer than the surrounding white matter in the cord, and the mechanics of gray and white matter do not change along the rostral-caudal axis. The primary goal of a spinal cord scaffold or conduit is to encourage axon growth in the rostral-caudal direction to restore connectivity across the site of injury, since axon tracts are primarily aligned in this direction [17,28,45]. Therefore, the axons infiltrating the scaffold are not growing along a rigidity gradient, but like axon tracts in native tissue, they are growing perpendicular to a disparity in matrix stiffness. The heterogeneity in scaffold stiffness may also affect the infiltration of other cell types beyond neurons including glial, immune, and vascular cells that may contribute to differences in axon infiltration. Overall, the mechanisms underlying increased axon infiltration in heterogeneous scaffolds compared to homogenous controls are likely different than those identified in previous durotaxis studies, including specific cell-matrix interactions [61,62] and small GTPase-mediated actomyosin contractility [63–65]. Future studies, which may include in vitro models of the spinal cord microenvironment, are therefore required to understand the molecular mechanisms responsible for the increased axon growth into the heterogeneous scaffolds.

The modification to digital light processing described here enables 3D-printing of complex topologies within mechanically heterogeneous hydrogels. DLP is a powerful tool for recreating complex tissue architectures in hydrogels, though previously the method has been limited to printing scaffolds exhibiting homogenous mechanics. However, other existing 3D-printing approaches are capable of printing interfacial and heterogeneous structures. For example, extrusion-based methods have been used to create heterogeneous aortic valve scaffolds [66]. But these methods are not applicable to softer, cell-permeable hydrogels, which are more appropriate for printing scaffolds with mechanics that match soft tissue like the spinal cord. And although 3D-printed scaffolds with elastic moduli greater than 200 kPa have been implanted within the spinal cord and demonstrated axon infiltration [45], DLP can recreate native tissue topology while also incorporating cell-based therapies by creating cell-permeable scaffolds with elastic moduli less than 10 kPa. One potential consideration for printing low stiffness hydrogels that is not addressed in this study is its effect on degradation rate and whether heterogeneous stiffness yields differences in degradation between the white and gray matter regions. Regardless of how the scaffolds are remodeled or degraded over time, the results of this study demonstrate that the initial stiffness gradient patterned in the heterogeneous scaffolds leads to increased axon infiltration at the 2-week time point. Moreover, the findings suggest that advancing DLP technology to print hydrogels with spatially varying mechanics provides an avenue to mimic the anisotropy of native tissues and to harness durotaxis by fabricating hydrogels that control cell growth and migration with stiffness gradients.

As advances in 3D-printing technology are made to mimic native tissue, one limitation to fabricating scaffolds that recreate the in vivo microenvironment is our understanding of complex tissue mechanics. Tissue mechanical properties are a function of multiple length scales, creating heterogeneity that is difficult to characterize and then implement in 3D-printed constructs. In this study, a variety of mechanical testing, including rheology and atomic force microscopy, are used to characterize spinal cord tissue ex vivo. These studies indicate that the macroscale mechanical properties of the spinal cord change as a function of level. Although previous work has shown that the mechanics of the cord are different based on the type of sectioning (e.g. coronal, sagittal, or transverse) [48], these results are the first to find differences in mechanical properties along the cord. Combining macroscale with microscale mechanical testing indicates that although the bulk mechanics differ along the cord, the mechanics of white matter and gray matter remain constant and gray matter is stiffer than white matter. Therefore, the differences in rheological properties arise from differences in the percentage of gray matter in the coronal section and not intrinsic disparity between levels. These findings justify the DLP-based approach to fabricate scaffolds that recreate a stiffer inner region to mimic the difference in gray-white matter mechanics. However, one aspect of the spinal cord tissue mechanics that the scaffolds do not mimic is viscoelasticity: the GelMA scaffolds are primarily elastic even though tensiometry indicated that gray matter exhibited higher stress relaxation. Therefore, there is a need for photoinks with tunable viscoelasticity, especially for tissues like the spinal cord that exhibit these properties.

Nonetheless, the DLP approach described here has the flexibility to incorporate existing neurotrophic therapies. As mentioned, in contrast to other 3D-printing approaches, the GelMA scaffolds printed for these studies are compatible with cell seeding within the bulk of the scaffold. There are currently ongoing clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of intrathecal injection of mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) in spinal cord injury patients [67], with evidence that MSCs release neurotrophic factors to stimulate axon growth and connectivity. Therefore, future studies will interrogate the benefit of incorporating MSCs into the heterogeneous scaffolds following implantation at the site of injury. In contrast to intrathecal injection, this approach can augment the residence time for MSCs at the site of injury and determine whether longer retention is beneficial. Moreover, the composition of the scaffold is also tunable. Although GelMA is used here, the DLP approach is compatible with many photoinks. Therefore, printing heterogeneous mechanics in degradable [68] or electrically conductive [31] photoinks provides a new means to combine different aspects of regenerative approaches in a multifunctional scaffold that mimics the mechanical anisotropy of native tissue.

Conclusions

The bulk rheological testing of transverse spinal cord sections reveal that the viscoelastic properties of the cord change along its length. But rather than being due to differences in microstructural properties, AFM and tensiometry indicate that the stiffness of gray and white matter does not change according to level. Therefore, the differences in bulk mechanical properties along the cord are caused by the disparity in the relative amounts of gray and white matter. A modification to an existing digital light processing technique that facilitate printing of scaffolds with heterogeneous mechanical properties provides a means to mimic the difference in stiffness between gray and white matter. Transplantation experiments in an acute transection rat model indicate that scaffolds featuring this heterogeneous mechanical profile results in greater axon infiltration compared to homogeneous mechanical properties. Although the mechanism underlying this difference is unclear, these results highlight the importance of developing biomaterials that mimic the spatial heterogeneity of spinal cord tissue.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Jordan Miller for helpful discussions and Kevin Jansen for assistance in printing scaffolds. We are especially grateful for the great people at Bringhurst Meats in Berlin, New Jersey for generously providing the bovine spinal cord tissue for the mechanical testing experiments. This work was funded by the Craig H. Neilsen Foundation.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Björklund A, Lindvall O, Cell replacement therapies for central nervous system disorders, Nat Neurosci. 3 (2000) 537–544. 10.1038/75705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Fischer I, Dulin JN, Lane MA, Transplanting neural progenitor cells to restore connectivity after spinal cord injury, Nat Rev Neurosci. 21 (2020) 366–383. 10.1038/s41583-020-0314-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Brown M, Vandergoot D, Quality of Life for Individuals with Traumatic Brain Injury: Comparison with Others Living in the Community, Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 13 (1998) 1–23. 10.1097/00001199-199808000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Massey JM, Amps J, Viapiano MS, Matthews RT, Wagoner MR, Whitaker CM, Alilain W, Yonkof AL, Khalyfa A, Cooper NGF, Silver J, Onifer SM, Increased chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan expression in denervated brainstem targets following spinal cord injury creates a barrier to axonal regeneration overcome by chondroitinase ABC and neurotrophin-3, Exp Neurol. 209 (2008) 426–445. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Yuan Y-M, He C, The glial scar in spinal cord injury and repair, Neurosci Bull. 29 (2013) 421–435. 10.1007/s12264-013-1358-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Iwashita M, Kataoka N, Toida K, Kosodo Y, Systematic profiling of spatiotemporal tissue and cellular stiffness in the developing brain, Development. 141 (2014) 3793–3798. 10.1242/dev.109637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Elkin BS, Azeloglu EU, Costa KD, Morrison III B, Mechanical Heterogeneity of the Rat Hippocampus Measured by Atomic Force Microscope Indentation, J Neurotrauma. 24 (2007) 812–822. 10.1089/neu.2006.0169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Christ AF, Franze K, Gautier H, Moshayedi P, Fawcett J, Franklin RJM, Karadottir RT, Guck J, Mechanical difference between white and gray matter in the rat cerebellum measured by scanning force microscopy, J Biomech. 43 (2010) 2986–2992. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Chatelin S, Constantinesco A, Willinger R, Fifty years of brain tissue mechanical testing: From in vitro to in vivo investigations, Biorheology. 47 (2010) 255–276. 10.3233/BIR-2010-0576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Cheng S, Clarke EC, Bilston LE, Rheological properties of the tissues of the central nervous system: A review, Med Eng Phys. 30 (2008) 1318–1337. 10.1016/j.medengphy.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].di Ieva A, Grizzi F, Rognone E, Tse ZTH, Parittotokkaporn T, Rodriguez y Baena F, Tschabitscher M, Matula C, Trattnig S, Rodriguez y Baena R, Magnetic resonance elastography: a general overview of its current and future applications in brain imaging, Neurosurg Rev. 33 (2010) 137–145. 10.1007/s10143-010-0249-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Mariappan YK, Glaser KJ, Ehman RL, Magnetic resonance elastography: A review, Clinical Anatomy. 23 (2010) 497–511. 10.1002/ca.21006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ichihara K, Taguchi T, Shimada Y, Sakuramoto I, Kawano S, Kawai S, Gray Matter of the Bovine Cervical Spinal Cord is Mechanically More Rigid and Fragile than the White Matter, J Neurotrauma. 18 (2001) 361–367. 10.1089/08977150151071053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hung T-K, Chang G-L, Chang J-L, Albin MS, Stress-strain relationship and neurological sequelae of uniaxial elongation of the spinal cord of cats, Surg Neurol. 15 (1981) 471–476. 10.1016/S0090-3019(81)80043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bilston LE, Thibault LE, The mechanical properties of the human cervical spinal cordIn Vitro, Ann Biomed Eng. 24 (1995) 67–74. 10.1007/BF02770996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Moeendarbary E, Weber IP, Sheridan GK, Koser DE, Soleman S, Haenzi B, Bradbury EJ, Fawcett J, Franze K, The soft mechanical signature of glial scars in the central nervous system, Nat Commun. 8 (2017) 1–11. 10.1038/ncomms14787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Partyka PP, Jin Y, Bouyer J, DaSilva A, Godsey GA, Nagele RG, Fischer I, Galie PA, Harnessing neurovascular interaction to guide axon growth, Sci Rep. 9 (2019) 1–10. 10.1038/s41598-019-38558-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Donoghue PS, Lamond R, Boomkamp SD, Sun T, Gadegaard N, Riehle MO, Barnett SC, The Development of a ɛ-Polycaprolactone Scaffold for Central Nervous System Repair, Tissue Eng Part A. 19 (2013) 497–507. 10.1089/ten.tea.2012.0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Shahriari D, Koffler JY, Tuszynski MH, Campana WM, Sakamoto JS, Hierarchically Ordered Porous and High-Volume Polycaprolactone Microchannel Scaffolds Enhanced Axon Growth in Transected Spinal Cords, Tissue Eng Part A. 23 (2017) 415–425. 10.1089/ten.tea.2016.0378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Zhang S, Wang X-J, Li W-S, Xu X-L, Hu J-B, Kang X-Q, Qi J, Ying X-Y, You J, Du Y-Z, Polycaprolactone/polysialic acid hybrid, multifunctional nanofiber scaffolds for treatment of spinal cord injury, Acta Biomater. 77 (2018) 15–27. 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Zhou X, Shi G, Fan B, Cheng X, Zhang X, Wang X, Liu S, Hao Y, Wei Z, Wang L, Feng S, Polycaprolactone electrospun fiber scaffold loaded with iPSCs-NSCs and ASCs as a novel tissue engineering scaffold for the treatment of spinal cord injury, Int J Nanomedicine. Volume 13 (2018) 6265–6277. 10.2147/IJN.S175914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zhang X, Gong B, Zhai J, Zhao Y, Lu Y, Zhang L, Xue J, A Perspective: Electrospun Fibers for Repairing Spinal Cord Injury, Chem Res Chin Univ. 37 (2021) 404–410. 10.1007/s40242-021-1162-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Xi K, Gu Y, Tang J, Chen H, Xu Y, Wu L, Cai F, Deng L, Yang H, Shi Q, Cui W, Chen L, Microenvironment-responsive immunoregulatory electrospun fibers for promoting nerve function recovery, Nat Commun. 11 (2020) 4504. 10.1038/s41467-020-18265-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Schaub NJ, Johnson CD, Cooper B, Gilbert RJ, Electrospun Fibers for Spinal Cord Injury Research and Regeneration, J Neurotrauma. 33 (2016) 1405–1415. 10.1089/neu.2015.4165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Yu Z, Li H, Xia P, Kong W, Chang Y, Fu C, Wang K, Yang X, Qi Z, Application of fibrin-based hydrogels for nerve protection and regeneration after spinal cord injury, J Biol Eng. 14 (2020) 22. 10.1186/s13036-020-00244-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Zhang Z, Yao S, Xie S, Wang X, Chang F, Luo J, Wang J, Fu J, Effect of hierarchically aligned fibrin hydrogel in regeneration of spinal cord injury demonstrated by tractography: A pilot study, Sci Rep. 7 (2017) 40017. 10.1038/srep40017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Sudhadevi T, Vijayakumar HS, v Hariharan E, Sandhyamani S, Krishnan LK, Optimizing fibrin hydrogel toward effective neural progenitor cell delivery in spinal cord injury, Biomedical Materials. 17 (2022) 014102. 10.1088/1748-605X/ac3680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Tran KA, Jin Y, Bouyer J, DeOre BJ, Suprewicz Ł, Figel A, Walens H, Fischer I, Galie PA, Magnetic alignment of injectable hydrogel scaffolds for spinal cord injury repair, Biomater Sci. (2022). 10.1039/d1bm01590g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Tran KA, Partyka PP, Jin Y, Bouyer J, Fischer I, Galie PA, Vascularization of self-assembled peptide scaffolds for spinal cord injury repair, Acta Biomater. 104 (2020) 76–84. 10.1016/j.actbio.2019.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Nakahashi T, Fujimura H, Altar CA, Li J, Kambayashi JI, Tandon NN, Sun B, Vascular endothelial cells synthesize and secrete brain-derived neurotrophic factor, FEBS Lett. 470 (2000) 113–117. 10.1016/S0014-5793(00)01302-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kiyotake EA, Thomas EE, Homburg HB, Milton CK, Smitherman AD, Donahue ND, Fung K, Wilhelm S, Martin MD, Detamore MS, Conductive and injectable hyaluronic acid/gelatin/gold nanorod hydrogels for enhanced surgical translation and bioprinting, J Biomed Mater Res A. 110 (2022) 365–382. 10.1002/jbm.a.37294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Shahriari D, Shibayama M, Lynam DA, Wolf KJ, Kubota G, Koffler JY, Tuszynski MH, Campana WM, Sakamoto JS, Peripheral nerve growth within a hydrogel microchannel scaffold supported by a kink-resistant conduit, J Biomed Mater Res A. 105 (2017) 3392–3399. 10.1002/jbm.a.36186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Pawelec KM, Koffler J, Shahriari D, Galvan A, Tuszynski MH, Sakamoto J, Microstructure and in vivo characterization of multi-channel nerve guidance scaffolds, Biomedical Materials. 13 (2018) 044104. 10.1088/1748-605X/aaad85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Bakshi A, Fisher O, Dagci T, Himes BT, Fischer I, Lowman A, Mechanically engineered hydrogel scaffolds for axonal growth and angiogenesis after transplantation in spinal cord injury, J Neurosurg Spine. 1 (2004) 322–329. 10.3171/spi.2004.1.3.0322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Costantini M, Testa S, Fornetti E, Barbetta A, Trombetta M, Cannata SM, Gargioli C, Rainer A, Engineering Muscle Networks in 3D Gelatin Methacryloyl Hydrogels: Influence of Mechanical Stiffness and Geometrical Confinement, Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 5 (2017). 10.3389/fbioe.2017.00022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lewandowska-Łańcucka J, Mystek K, Mignon A, van Vlierberghe S, Łatkiewicz A, Nowakowska M, Alginate- and gelatin-based bioactive photocross-linkable hybrid materials for bone tissue engineering, Carbohydr Polym. 157 (2017) 1714–1722. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Poldervaart MT, Goversen B, de Ruijter M, Abbadessa A, Melchels FPW, Öner FC, Dhert WJA, Vermonden T, Alblas J, 3D bioprinting of methacrylated hyaluronic acid (MeHA) hydrogel with intrinsic osteogenicity, PLoS One. 12 (2017) e0177628. 10.1371/journal.pone.0177628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Feng Q, Wei K, Lin S, Xu Z, Sun Y, Shi P, Li G, Bian L, Mechanically resilient, injectable, and bioadhesive supramolecular gelatin hydrogels crosslinked by weak host-guest interactions assist cell infiltration and in situ tissue regeneration, Biomaterials. 101 (2016) 217–228. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Li X, Chen S, Li J, Wang X, Zhang J, Kawazoe N, Chen G, 3D Culture of Chondrocytes in Gelatin Hydrogels with Different Stiffness, Polymers (Basel). 8 (2016) 269. 10.3390/polym8080269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Chung C, Beecham M, Mauck RL, Burdick JA, The influence of degradation characteristics of hyaluronic acid hydrogels on in vitro neocartilage formation by mesenchymal stem cells, Biomaterials. 30 (2009) 4287–4296. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Erickson IE, Huang AH, Chung C, Li RT, Burdick JA, Mauck RL, Differential Maturation and Structure–Function Relationships in Mesenchymal Stem Cell- and Chondrocyte-Seeded Hydrogels, Tissue Eng Part A. 15 (2009) 1041–1052. 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Bryant SJ, Anseth KS, The effects of scaffold thickness on tissue engineered cartilage in photocrosslinked poly(ethylene oxide) hydrogels, Biomaterials. 22 (2001) 619–626. 10.1016/S0142-9612(00)00225-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Li H, Koenig AM, Sloan P, Leipzig ND, In vivo assessment of guided neural stem cell differentiation in growth factor immobilized chitosan-based hydrogel scaffolds, Biomaterials. 35 (2014) 9049–9057. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Leipzig ND, Wylie RG, Kim H, Shoichet MS, Differentiation of neural stem cells in three-dimensional growth factor-immobilized chitosan hydrogel scaffolds, Biomaterials. 32 (2011) 57–64. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Koffler J, Zhu W, Qu X, Platoshyn O, Dulin JN, Brock J, Graham L, Lu P, Sakamoto J, Marsala M, Chen S, Tuszynski MH, Biomimetic 3D-printed scaffolds for spinal cord injury repair, Nat Med. (2019). 10.1038/s41591-018-0296-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Grigoryan B, Paulsen SJ, Corbett DC, Sazer DW, Fortin CL, Zaita AJ, Greenfield PT, Calafat NJ, Gounley JP, Ta AH, Johansson F, Randles A, Rosenkrantz JE, Louis-Rosenberg JD, Galie PA, Stevens KR, Miller JS, Multivascular networks and functional intravascular topologies within biocompatible hydrogels, Science (1979). 364 (2019) 458–464. 10.1126/science.aav9750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Kinstlinger IS, Miller JS, 3D-printed fluidic networks as vasculature for engineered tissue, Lab Chip. 16 (2016) 2025–2043. 10.1039/C6LC00193A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Koser DE, Moeendarbary E, Hanne J, Kuerten S, Franze K, CNS Cell Distribution and Axon Orientation Determine Local Spinal Cord Mechanical Properties, Biophys J. 108 (2015) 2137–2147. 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Mitra P, Brownstone RM, An in vitro spinal cord slice preparation for recording from lumbar motoneurons of the adult mouse, J Neurophysiol. 107 (2012) 728–741. 10.1152/jn.00558.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Richner M, Jager SB, Siupka P, Vaegter CB, Hydraulic Extrusion of the Spinal Cord and Isolation of Dorsal Root Ganglia in Rodents, Journal of Visualized Experiments. (2017). 10.3791/55226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].GRIFFIN M, CASADIO R, BERGAMINI CM, Transglutaminases: Nature’s biological glues, Biochemical Journal. 368 (2002) 377–396. 10.1042/bj20021234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Domínguez-Bajo A, González-Mayorga A, Guerrero CR, Palomares FJ, García R, López-Dolado E, Serrano MC, Myelinated axons and functional blood vessels populate mechanically compliant rGO foams in chronic cervical hemisected rats, Biomaterials. 192 (2019) 461–474. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Pogoda K, Chin L, Georges PC, Byfield FJ, Bucki R, Kim R, Weaver M, Wells RG, Marcinkiewicz C, Janmey PA, Compression stiffening of brain and its effect on mechanosensing by glioma cells, New J Phys. 16 (2014) 075002. 10.1088/1367-2630/16/7/075002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Perepelyuk M, Chin L, Cao X, van Oosten A, Shenoy VB, Janmey PA, Wells RG, Normal and Fibrotic Rat Livers Demonstrate Shear Strain Softening and Compression Stiffening: A Model for Soft Tissue Mechanics, PLoS One. 11 (2016) e0146588. 10.1371/journal.pone.0146588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Bian L, Hou C, Tous E, Rai R, Mauck RL, Burdick JA, The influence of hyaluronic acid hydrogel crosslinking density and macromolecular diffusivity on human MSC chondrogenesis and hypertrophy, Biomaterials. 34 (2013) 413–421. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.09.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Puckert C, Tomaskovic-Crook E, Gambhir S, Wallace GG, Crook JM, Higgins MJ, Electromechano responsive properties of gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) hydrogel on conducting polymer electrodes quantified using atomic force microscopy, Soft Matter. 13 (2017) 4761–4772. 10.1039/C7SM00335H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Li XQ, Verge VMK, Johnston JM, Zochodne DW, CGRP peptide and regenerating sensory axons, J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 63 (2004) 1092–1103. 10.1093/jnen/63.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Shellard A, Mayor R, Collective durotaxis along a self-generated stiffness gradient in vivo, Nature. 600 (2021) 690–694. 10.1038/s41586-021-04210-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Pi-Jaumà I, Alert R, Casademunt J, Collective durotaxis of cohesive cell clusters on a stiffness gradient, The European Physical Journal E. 45 (2022) 7. 10.1140/epje/s10189-02100150-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Guimarães CF, Gasperini L, Marques AP, Reis RL, The stiffness of living tissues and its implications for tissue engineering, Nat Rev Mater. 5 (2020) 351–370. 10.1038/s41578019-0169-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Hartman CD, Isenberg BC, Chua SG, Wong JY, Vascular smooth muscle cell durotaxis depends on extracellular matrix composition, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (2016) 11190–11195. 10.1073/pnas.1611324113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Espina JA, Marchant CL, Barriga EH, Durotaxis: the mechanical control of directed cell migration, FEBS J. 289 (2022) 2736–2754. 10.1111/febs.15862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].DeOre BJ, Partyka PP, Fan F, Galie PA, CD44 mediates shear stress mechanotransduction in an in vitro blood‐brain barrier model through small GTPases RhoA and Rac1, The FASEB Journal. 36 (2022). 10.1096/fj.202100822RR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].DeOre BJ, Baldwin‐LeClair A, Tran KA, DaSilva A, Byfield FJ, Janmey PA, Galie PA, Microindentation of Fluid‐Filled Cellular Domes Reveals the Contribution of RhoA‐ROCK Signaling to Multicellular Mechanics, Small. 18 (2022) 2200883. 10.1002/smll.202200883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].DeOre BJ, Tran KA, Andrews AM, Ramirez SH, Galie PA, SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Disrupts Blood–Brain Barrier Integrity via RhoA Activation, Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology. 16 (2021) 722–728. 10.1007/s11481-021-10029-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Hockaday LA, Kang KH, Colangelo NW, Cheung PYC, Duan B, Malone E, Wu J, Girardi LN, Bonassar LJ, Lipson H, Chu CC, Butcher JT, Rapid 3D printing of anatomically accurate and mechanically heterogeneous aortic valve hydrogel scaffolds, Biofabrication. 4 (2012) 035005. 10.1088/1758-5082/4/3/035005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Bydon M, Dietz AB, Goncalves S, Moinuddin FM, Alvi MA, Goyal A, Yolcu Y, Hunt CL, Garlanger KL, del Fabro AS, Reeves RK, Terzic A, Windebank AJ, Qu W, CELLTOP Clinical Trial: First Report From a Phase 1 Trial of Autologous Adipose Tissue–Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells in the Treatment of Paralysis Due to Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury, Mayo Clin Proc. 95 (2020) 406–414. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Thomas A, Orellano I, Lam T, Noichl B, Geiger M-A, Amler A-K, Kreuder A-E, Palmer C, Duda G, Lauster R, Kloke L, Vascular bioprinting with enzymatically degradable bioinks via multi-material projection-based stereolithography, Acta Biomater. 117 (2020) 121–132. 10.1016/j.actbio.2020.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.