Abstract

Purpose:

To determine if Artificial Intelligence-based computation of global longitudinal strain (GLS) from left ventricular (LV) MRI is an early prognostic factor of cancer therapy-related cardiac dysfunction (CTRCD) in breast cancer patients. The main hypothesis based on the patients receiving antineoplastic chemotherapy treatment was CTRCD risk analysis with GLS that was independent of LV ejection fraction (LVEF).

Methods:

Displacement Encoding with Stimulated Echoes (DENSE) MRI was acquired on 32 breast cancer patients at baseline and 3- and 6-month follow-ups after chemotherapy. Two DeepLabV3+ Fully Convolutional Networks (FCNs) were deployed to automate image segmentation for LV chamber quantification and phase-unwrapping for 3D strains, computed with the Radial Point Interpolation Method. CTRCD risk (cardiotoxicity and adverse cardiac events) was analyzed with Cox Proportional Hazards (PH) models with clinical and contractile prognostic factors.

Results:

GLS worsened from baseline to the 3- and 6-month follow-ups (−19.1 ± 2.1%, −16.0 ± 3.1%, −16.1 ± 3.0%; P < 0.001). Univariable Cox regression showed the 3-month GLS significantly associated as an agonist (hazard ratio [HR]-per-SD: 2.1; 95% CI: 1.4–3.1; P < 0.001) and LVEF as a protector (HR-per-SD: 0.8; 95% CI: 0.7–0.9; P = 0.001) for CTRCD occurrence. Bivariable regression showed the 3-month GLS (HR-per-SD: 2.0; 95% CI: 1.2–3.4; P = 0.01) as a CTRCD prognostic factor independent of other covariates, including LVEF (HR-per-SD: 1.0; 95% CI: 0.9–1.2; P = 0.9).

Conclusions:

The end-point analyses proved the hypothesis that GLS is an early, independent prognosticator of incident CTRCD risk. This novel GLS-guided approach to CTRCD risk analysis could improve antineoplastic treatment with further validation in a larger clinical trial.

Keywords: Cancer therapy-related cardiac dysfunction, Cox proportional hazards, Global longitudinal strain, Left ventricular ejection fraction, Fully convolutional network, Artificial intelligence

1. Introduction

Peak global longitudinal strain (GLS) in the left ventricle (LV) assessed by MRI, echocardiography, and other medical imaging techniques provides quantitative assessment of systolic dysfunction in cardiac diseases, which is now an extensively studied prognostic factor in heart failure (HF) [1–3]. GLS is also an independent indicator of cancer therapy-related cardiac dysfunction (CTRCD) in breast cancer patients during or following treatment with antineoplastic chemotherapeutic agents such as anthracyclines and trastuzumab [3–13]. Many studies have reported the short and long-term natural history of CTRCD, including cardiotoxicity, primarily diagnosed with a reduced LV ejection fraction (LVEF) or an adverse cardiac event that may occur following antineoplastic treatment [3,8,9,14,15]. LVEF is also used as a prognostic factor for CTRCD risk analysis, followed by prognosis with other clinical measurements such as troponin and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) levels [8,10,14]. However, monitoring systolic cardiac dysfunction from chemotherapy can be inadequate with LVEF if it remains preserved during early, subclinical LV deterioration in patients and does not provide sufficient evidence to begin medical therapy for toxic CTRCD [3,5,15,16]. Alternatively, recent single-center to large-scale meta-analysis studies and expert-analysis (such as the Tuzovic et al. recent summary on 26 major clinical studies) show that GLS is an emerging biomarker for prognosticating CTRCD [15–19]. These studies consistently report GLS as a more sensitive biomarker than LVEF for the early diagnosis of cardiac dysfunction that may arise from antineoplastic treatment and progress to CTRCD [15,16,18–20]. In one of the early single-center prospective studies, Sawaya et al. investigated GLS as a CTRCD prognosticator in patients treated with a combination of anthracyclines, trastuzumab, and taxanes [14]. The authors showed via multiple logistic regression that the 3-month follow-up GLS (odds ratio [OR]: 500; 95% CI: 6.7–110,000, P = 0.01) and elevated high-sensitivity plasma troponin (OR: 9; 95% CI: 1.8–50, P = 0.006) were the only prognosticators of later occurrence of cardiotoxicity. A recent single-center study by Araujo-Gutierrez et al. on 188 patients (a majority with breast and hematologic cancers) showed that baseline GLS ≥ −18% was predictive (hazard ratio [HR]-per-SD: 3.5; 95% CI: 1.3–9.4; P <0.01) of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity with 70% for both sensitivity and specificity in the 23 patients who developed CTRCD [21]. In their meta-analysis, Oikonomou et al. also established an absolute threshold GLS ≥ −18% (−21.0 - −13.8%), occurring within a mean follow-up time of ~2.8 months for prognosticating CTRCD in breast cancer patients from nine single-center studies [14,15,18,22,23]. In the 19.9% (9.3–32.1%) clinically diagnosed cases from all nine studies, the authors found the above threshold GLS to prognosticate high CTRCD risk (OR: 30.0; 95% CI: 5.9–151.6) with 83% sensitivity and 74% specificity [15].

In this prospective study, we investigated early alterations in prognostic factors such as GLS with standard Cox Proportional Hazards (PH) regression for incident CTRCD risk in breast cancer patients treated with anthracyclines and trastuzumab [24,25]. The prognostic factors were selected from clinical and contractile measurements (such as blood pressure [BP], glomerular filtration rate [GFR], LVEF, and GLS) before the initiation of chemotherapy and at two post-treatment follow-ups after 3 and 6 months, and the changes observed in each parameter over time with one-way repeated ANOVA (RANOVA). Cox PH regression models for risk and survival analysis were built from the prognostic factor(s) determined at the time point when its measurement significantly differed from other time points in the RANOVA results. Patients were imaged with the Displacement Encoding with Stimulated Echoes (DENSE) MRI sequence, a convenient, one-stop protocol for LV imaging and motion capture [6,7,11,12,26–28]. For detecting LV dysfunction, we used validated, advanced Artificial Intelligence (AI) methodologies developed with Fully Convolutional Networks (FCNs) for (a) segmenting the DENSE magnitude images for chamber quantification and (b) segmenting the DENSE phase images for phase-unwrapping and 3D strain analysis [6,7,11,12,29–38]. To the best of our knowledge, this is a novel study that enabled the prediction of CTRCD risk in breast cancer patients treated with antineoplastic agents in our center based on chamber quantification and strain prognostic factors estimated with FCN technology [6,7,11,12].

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Human subjects

The tracking of CTRCD was conducted in adult female breast cancer survivors (N = 32 out of 39 eligible) who were treated with antineoplastic chemotherapy agents (anthracyclines and trastuzumab). The patients were evaluated at baseline (before chemotherapy) and at two follow-ups at 3 and 6 months after completion of chemotherapy. Patients with preexisting, acute cardiovascular diseases (CVD) with the potential to confound CTRCD diagnosis were excluded [6]. Overall, exclusion criteria included LVEF <45%, previous cardiac injury (for example, myocardial infarction), valvular stenosis or moderate-to-severe regurgitation; previous diagnosis of HF, systolic blood pressure (SBP) < 100 mmHg, contraindications to beta-blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), metastatic disease, chronic kidney and liver diseases, and < 12-month life expectancy [6]. Patients who did not consent to participation or dropped out after the baseline were excluded, but data on those who completed the 3-month follow-up were added to the final analysis. Patients signed informed consent forms approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) to acknowledge participation on the three occasions of their MRI studies and. to grant access to their medical histories.

The chemotherapy treatment regimen in patients (with individual patient-based modifications) consisted of either one of the two broader categories: (a) 60 mg/m2 of doxorubicin (anthracycline), cyclophosphamide, and taxol for 4-cycles or weekly for 12 weeks (ACT); (b) 8 mg/kg loading +6 mg/kg trastuzumab, taxol, carboplatin, and optional pertuzumab for 6-cycles, followed by optional 8 mg/kg initial loading and 6 mg/kg trastuzumab weekly for up to a year (TCH[P]) [6]. At each visit, blood was obtained for measurement of routine electrolyte and metabolic parameters. The navigator-gated DENSE sequence was chosen for MRI scans that we have used in previous studies to investigate cardiotoxicity arising from antineoplastic chemotherapy in breast cancer patients [6,7,11,12,26–28]. Transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) measurements for LVEF, LV filling indices and GLS were acquired coincidental with their MRI exams at all three time points, thus allowing LVEF and GLS comparisons between the two modalities. CTRCD was diagnosed in this study according to guidelines from the 2022 consensus issued by the International Cardio-Oncology Society (IC-OS) and the American College of Cardiology (ACC), and the 2014 consensus issued by the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging (ASE-EACI) [8,9,19]. The five cardiotoxic focus areas that may lead to CTRCD and adverse cardiac event occurrences are defined by these societies as defined in Fig. 1 [8,9,19].

Fig. 1.

Outline of the five focus areas of cancer therapy related cardiac dysfunction caused by potentially toxic chemotherapy.

2.2. Fully convolutional networks for chamber quantification and strain analysis

For LV dysfunction analysis, we applied automated AI methodologies with two DeepLabV3+ FCNs for segmenting the DENSE magnitude images for chamber quantification and the DENSE phase images for phase-unwrapping and 3D strain analysis [6,7,11,12,29–34,36,38]. The DeepLabV3+ FCN consists of an encoder-decoder architecture, atrous convolution (with different dilation rates) to capture multi-scale context, a convolutional scorer function, and a softmax with cross-entropy function for final classification before output [11,12,31–33,36–39]. Two of our recent studies give details on the DeepLabV3+ architectures for segmenting the DENSE magnitude and phase images for automating LV strain analysis [11,12]. Upon segmenting the magnitude images and 3D LV reconstructions, the chamber quantification parameters computed were LVEF, LV end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD), end-diastolic volume (LVEDV), end-systolic diameter (LVESD), end-systolic volume (LVESV), stroke volume (LVSV) and mass (LVM). A similar DeepLabV3+ FCN architecture was used for phase-unwrapping the DENSE data, which is converted to displacements for computing 3D strains (radial, circumferential and longitudinal) and torsion with our existing meshfree Radial Point Interpolation Method (RPIM) technique [11,12,38,40]. Phase-unwrapping with DeepLabV3+ semantic segmentation to classify the integer wrap-counts, k(x, y), which relates the true underlying phase, φ(x,y), to the wrapped phase, ∅ (x, y), by the equation, φ(x,y) = ∅ (x,y) + 2πk(x,y), and converting φ(x, y) to displacements are detailed in our previous study [12,40,41].

To maximize the accuracy of the segmentation networks, both DeepLabV3+ FCNs were evaluated with three different backbone encoders using MATLAB’s Deep Learning Toolbox™ (MATLAB, Version 2022a, Natick, MA) [36,38,42,43]. The three backbones evaluated per FCN were the ResNet-50, ResNet-101, and Xception encoders (each having atrous convolution for gradual feature map reductions), and segmentation results from the highest accuracy encoders used for chamber quantification and strain analysis [36,38,39,43]. We made modifications to particular encoder layers, such as initializing the first convolution layer with smaller LoG filters, to improve the detection and phase-unwrapping of small-object classes like the myocardium [38]. The training and testing with all six combinations of FCNs and encoders were performed on a machine with Intel Xeon E5–2690 Processor at 2.60 GHz CPU, NVIDIA Pascal Titan X GPU, and 128-GB RAM. While full details on the three encoders can be found in the original studies by Chen et al., brief descriptions of each are provided in the following [35,36,38].

2.2.1. ResNet-50 and ResNet-101 as encoders

For both, we used He et al.’s [39] original model modified by Chen et al. [35,36] to incorporate the use of multiple repeated convolutional architecture elements and residual modules for identity mapping. The modifications include employing atrous convolution for denser feature extraction, where a dilation rate = 2 was applied in the last encoder block [35]. The other main modification is augmentation with the Atrous Spatial Pyramid (ASPP) block, which also probes convolutional features at multiple scales by applying different rates of dilated convolution [36].

2.2.2. Xception as encoder

This was a modified, atrous version of the original Aligned Xception model proposed by Chollet et al. [38,43]. The proposed modifications by Chen et al. we adapted for the Xception model included (a) addition of depth with more convolutional layers, (b) extra batch normalization and ReLU added after each 3 × 3 depthwise convolution, and (c) feature map extractions with ASPP as above [38].

For segmenting the magnitude images, the apex-to-base DENSE data acquired over the systolic period were distributed into a training set (44 datasets consisting of 8995 images), a validation set (20 datasets consisting of 4080 images), and a test set (32 datasets consisting of 6545 images). A bigger training set (higher than 50% of data) was not required because of imaging similar anatomy with similar acquisition parameters (such as FOV) and because sequential studies were repeated in the patients. The DICOM data were converted into default three-channel Portable Network 16-bit Graphics (PNG) RGB images as input into the DeepLabV3+ network [11]. The ground truth labels were generated with a semi-automated, quantization-based segmentation technique validated in our previous studies, and each image was segmented into four classes for training the FCN [44,45]. The four classes the FCN learned to classify automatedly were the (a) myocardium between the epicardium-endocardium walls, (b) LV-cavity (LVC), (c) chest-wall (CW) denoting the surrounding frame, and (d) chest cavity (CC) [11]. Like our validation study on segmenting the DENSE magnitude images, the training parameters chosen for this FCN were a mini-batch of size = 24 of randomly selected images in every epoch and random data augmentation set to ±10% translation in the x and y directions and ± 45° of rotation [11]. As done previously, other parameters like the learning rate and the number of max epochs were determined as 0.001 and 60 from fine-tuning via the gradient proportional to the noise-scale method [11,12]. For segmenting the phase images, the systolic period apex-to-base phase data in the three acquisition directions were divided into training (44 datasets consisting of 26,985 images), validation (20 datasets consisting of 12,240 images), and test sets (32 datasets consisting of 19,635 images) [11,12]. The ground-truth phase data were generated with the Quality Guided Phase Unwrapping (QGPU) algorithm, a classical unwrapping approach used in all our previous validation studies [6,7]. Since human LV displacement does not exceed ~1–2 cm (−3π < φ < 3π in detected true phases), three distinct integer wrap-counts, k(x, y) ∈ [−1,0,1], were detected in the phase images, amounting to four segmented classes after adding an extra-myocardial background class [12,46]. For input to the encoder, the wrapped DICOM phase images were converted into single-channel grayscale images in PNG format. The DeepLabV3+ architecture and parameters from the phase-unwrapping validation study were retained for training and deploying this FCN to segment wrap-counts [12]. Following phase-unwrapping, the LV global radial strain (GRS), circumferential strain (GCS), GLS, and apical torsion were computed with RPIM [6,12,26].

2.3. DENSE acquisition protocol

Navigator-gated, spiral 3D DENSE data were acquired on a 1.5 T MAGNETOM Espree (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) scanner with displacement encoding applied in two orthogonal in-plane directions and one through-plane direction [6,26–28,41,45]. The parameters for acquiring patient LV images were field of view (FOV) = 360 × 360 mm2, matrix size = 128 × 128, echo time (TE) = 1.04 ms, repetition time (TR) = 15 ms, end flip angle = 20°, voxel size of 2.81 × 2.81 × 5 mm3, displacement encoding frequency (𝓀e) = 0.06 cycles/mm, and number of cardiac phases = 19–21 in each x, y, and z directions. The mechanism of artifact suppression was via simple 4-point encoding and 3-point phase cycling [27,28]. For receiving patient signals, the Espree has an anterior 18-channel array coil in combination with elements of the table-mounted spine array coil. Heart rates (HRT) and diastolic and systolic blood pressures (DBP/SBP) were monitored continuously during the scans.

2.4. Echocardiography acquisition protocol and offline analysis

Echocardiography was performed using a GE Vivid E95 system equipped with a 6Tc (3.0–8.0 MHz) TEE probe (GE HealthCare, Chicago, IL). For each patient’s assessment, ECG-synchronized frames were recorded from at least three consecutive cardiac cycles with 2D echocardiography (2DE) parasternal views and apical 4-, 3-, and 2-chamber views. Chamber quantification and strain analysis with 2D Speckle-tracking (2D-STE) were performed offline on a workstation computer using the EchoPAC (Version 1.8.1.X, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) software. Measurements of all LV chamber quantification parameters were done in the parasternal long axis and in the apical 4-chamber view and chamber volumes were calculated with the Simpson formula. Longitudinal strain was detected at the basal, midventricular, and apical level of each wall, for which the ROI was defined by the examiner and timed at end-diastole and end-systole.

2.5. Performance metrics and statistical analysis

The performance metrics of both FCNs were evaluated with the Deep Learning Toolbox™ in MATLAB, and statistical analyses on clinical and contractile prognostic factors were conducted with SPSS (Version 28, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). The performances were evaluated on independent test sets and included computing the F1 score, Dice score, average perpendicular distance (APD), Hausdorff distance, and sensitivity-specificity analysis [11,12]. Precision and recall results of pixelwise classification in both test sets were expressed via confusion matrices, which provided a one-to-one comparison between actual and predicted classes [11,12]. The receiver-operating characteristic curve (ROC) with the area under the curve (AUC) based on the true-positive and false-positive rates of myocardial detection and wrap-count predictions by the FCNs were graphed.

Basic statistical analysis included computing means and standard deviations on the patients’ clinical and contractile data after all three time points of MRI acquisition. The clinical data obtained from each patient at each time point included their DBP, SBP, HRT, body surface area (BSA), body mass index (BMI), GFR, existing comorbidities (hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, coronary artery disease (CAD), and diabetes mellitus), medications for any congestive HF (CHF), and details on chemotherapy regimen (ACT or TCH[P]) and radiation therapy. Measurements of contractile parameters included chamber quantification and strains listed under the Fully Convolutional Networks for Chamber Quantification and Strain Analysis section. Any changes in the parameters of interest between baseline and the two follow-ups was observed with RANOVA and within-subject pairwise comparisons. RANOVA to observe any time-dependent changes in the contractile parameters were also conducted in a subgroup of patients without a net reduction in LVEF within the study period. The Interclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) with Cronbach’s Alpha indices were computed between the DENSE and 2DE-derived LVEF and GLS at each time point to establish the reliability of the new DENSE-FCN methodology.

2.6. Risk and survival analysis

This study’s end-point goal was to identify prognostic factors that predict risk and onset of CTRCD (cardiotoxicity and other cardiac events as defined above) that arise from treatment with antineoplastic agents. It is noted that in this study’s context, statistical survival refers to predictive analysis for the non-development of CTRCD [24,25]. The challenge was assuring the quality of prognostic factors research with risk analysis in a small, single-center prospective study complete with survival time information and censoring [24,25,47]. Hence, to determine genuine prognostic factors, we approached CTRCD risk analysis with gold standard univariable and bivariable Cox PH models built from significant RANOVA parameters (GLS, LVEF, and others) [24,25]. We chose the prognostic factors based on RANOVA parameters at specific time points when their measurement differed significantly from other time points in the within-subjects pairwise comparisons. Supplement A outlines the Cox PH formulation behind this study’s risk and survival analyses [24]. A hazard score with P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for both univariable and bivariable models. Finally, we investigated the personalized risk of CTRCD occurring in the individual patient with the built Cox PH models to assess the trade-off between the benefit of antineoplastic treatment versus high risk of cardiotoxicity [48,49]. In the Results section, we show examples of computing an individual patient’s chances of not developing CTRCD by estimating survival, , where t is time and Xi are prognosis factors given in Eq. A5 in Supplement A.

3. Results

Of the 39 breast cancer patients found eligible, five patients refused participation, two did not return for follow-ups after the baseline, and one patient did not return for the final 6-month follow-up. After excluding the seven patients with all or majority of their DENSE MRI data missing, 32 patients were finally included in the analysis The reasons for non-participation or dropping out were (a) perceived lack of clinical benefit from a research study, (b) emotional distress caused by suffering from breast cancer, and (c) long-distance drives to the research facility. The mean scan time per MRI exam per patient was 30 ± 22 min. The MRI scans were held at the institute’s Children’s and Women’s Hospital, which houses the Espree scanner in its Imaging Center. The Imaging Center is an easily accessible first-floor facility that provides a pleasant, relaxed atmosphere for patients. For the patient whose 6-month MRI results were not available, the missing chamber quantification and strain data were replaced with regression-based multiple imputations in SPSS. Student’s t-test comparisons did not show any differences between the patients with fully available data (N = 31) and the entire cohort with imputed parameter values (N = 32). Table 1 shows the clinical profiles of patients recorded at baseline and at the two follow-up visits. The RANOVA analyses in Table 1 between the three time points show the short-term increases in SBP (P < 0.001) and HRT (P < 0.001) from baseline to the 3-month follow-up. Posthoc analyses with a Bonferroni adjustment revealed SBP increased significantly from baseline to the 3-month follow-up (ΔSBP = 1.6 mmHg; 95% CI: 1.0–2.1 mmHg; P < 0.001) but then significantly decreased between the 3-month and 6-month follow-ups (ΔSBP = −1.4 mmHg; 95% CI: −2.0 - −0.8 mmHg; P < 0.001). Similarly, HRT significantly increased from baseline to the 3-month follow-up (ΔHRT = 1.4 bpm; 95% CI: 0.3–2.5 bpm; P = 0.01), and then decreased between the 3-month and 6-month follow-ups (ΔHRT = −1.3 bpm; 95% CI: −2.3 - −0.3 bpm; P = 0.02). Hence, insignificant net changes were seen between baseline and the 6-month follow-up for both SBP (ΔSBP = 0.2 mmHg; 95% CI: −0.1 – 0.4 mmHg; P = 0.14) and HRT (ΔHRT = 0.2 bpm; 95% CI: 0.0–0.4 bpm; P = 0.07).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and treatment.

| Parameters | Intervals | P-value* | Pairwise (0–3 mos.)** | Pairwise (3–6 mos.)** | Pairwise (0–6 mos.)** | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 months | 3 months | 6 months | |||||

| Demography | |||||||

| Age (years) | 59.4 (9.7) | 59.6 (9.7) | 59.9 (9.7) | < .001 | 0.25 (0.25 – 0.25, <.001) | 0.25 (0.25 – 0.25, < .001) | 0.50 (0.50 – 0.50, < .001) |

| DBP (mmHg) | 77.2 (9.4) | 77.6 (9.5) | 77.4 (9.4) | .10 | 0.33 (−0.05 – 0.70, .09) | −0.16 (−0.32 – 0.01, .06) | 0.17 (−0.10 – 0.44, .21) |

| SBP (mmHg) | 126.2 (18.9) | 127.7 (18.4) | 126.4 (18.6) | < .001 | 1.54 (0.96 – 2.12, <.001) | −1.38 (−2.00 - −0.76, < .001) | 0.16 (−0.05 – 0.37,. 14) |

| HRT (bpm) | 79.5 (10.3) | 80.9 (10.2) | 79.7 (9.9) | < .001 | 1.43 (0.32 – 2.54, .01) | −1.25 (−2.25 - −0.26, .02) | 0.18 (−0.02 – 0.37, .07) |

| Body Mass (kg) | 81.4 (18.4) | 83.9 (21.4) | 81.6 (18.3) | .32 | 2.55 (−2.36 – 7.46, .30) | −2.31 (−7.16 – 2.53, .34) | 0.24 (−0.10 – 0.58, .16) |

| BMI (kg/m 2 ) | 30.2 (6.9) | 31.2 (8.2) | 30.3 (6.9) | .27 | 1.02 (−0.76 – 2.80, .25) | −0.92 (−2.68 – 0.84, .30) | 0.10 (−0.03 −0.22, .12) |

| BSA (m 2 ) | 1.9 (0.2) | 1.9 (0.3) | 1.9 (0.2) | .36 | 0.04 (−0.03 – 0.09, .31) | −0.03 (−0.09 – 0.04, .41) | 0.01 (−0.01 – 0.02, .33) |

| GFR (mL/min/1.73m 2 ) | 87.3 (18.1) | 86.1 (19.5) | 86.7 (19.6) | .34 | −1.22 (−3.14 – 0.69, .20) | 0.63 (−0.03 – 1.28, .06) | −0.60 (−3.01 – 1.81, .62) |

| Comorbidities | |||||||

| Hypertension | 11 | 12 | 13 | 0.228 | 0.03 (−0.03 – 0.10, 0.33) | 0.03 (−0.03 – 0.10, 0.33) | 0.06 (−0.03 – 0.15, 0.16) |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 10 | 11 | 11 | 0.325 | 0.03 (−0.03 – 0.10, 0.33) | 0.00 (0.00 – 0.00, 1.00) | 0.03 (−0.03 – 0.10, 0.33) |

| CAD | 2 | 2 | 2 | - | - | - | - |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 5 | 5 | 5 | - | - | - | - |

| CHF Meds | 14 | 14 | 14 | - | - | - | - |

| Chemotherapy | |||||||

| Anthracyclines | - | - | 18 | - | - | - | - |

| Trastuzumab | - | - | 14 | - | - | - | - |

| Radiotherapy | - | - | 17 | - | - | - | - |

| Detected cases ₵ | - | - | 9 | - | - | - | - |

Abbreviations: DBP: Diastolic blood pressure, SBP: Systolic blood pressure, HRT: Heart rate, BSA: Body surface area, BMI: Body mass index, GFR: Glomerular filtration rate.

Clinician detected cardiotoxicity.

RANOVA P-value between the three measurements.

pairwise differences and its CI and P-values.

Standard deviations given in parenthesis

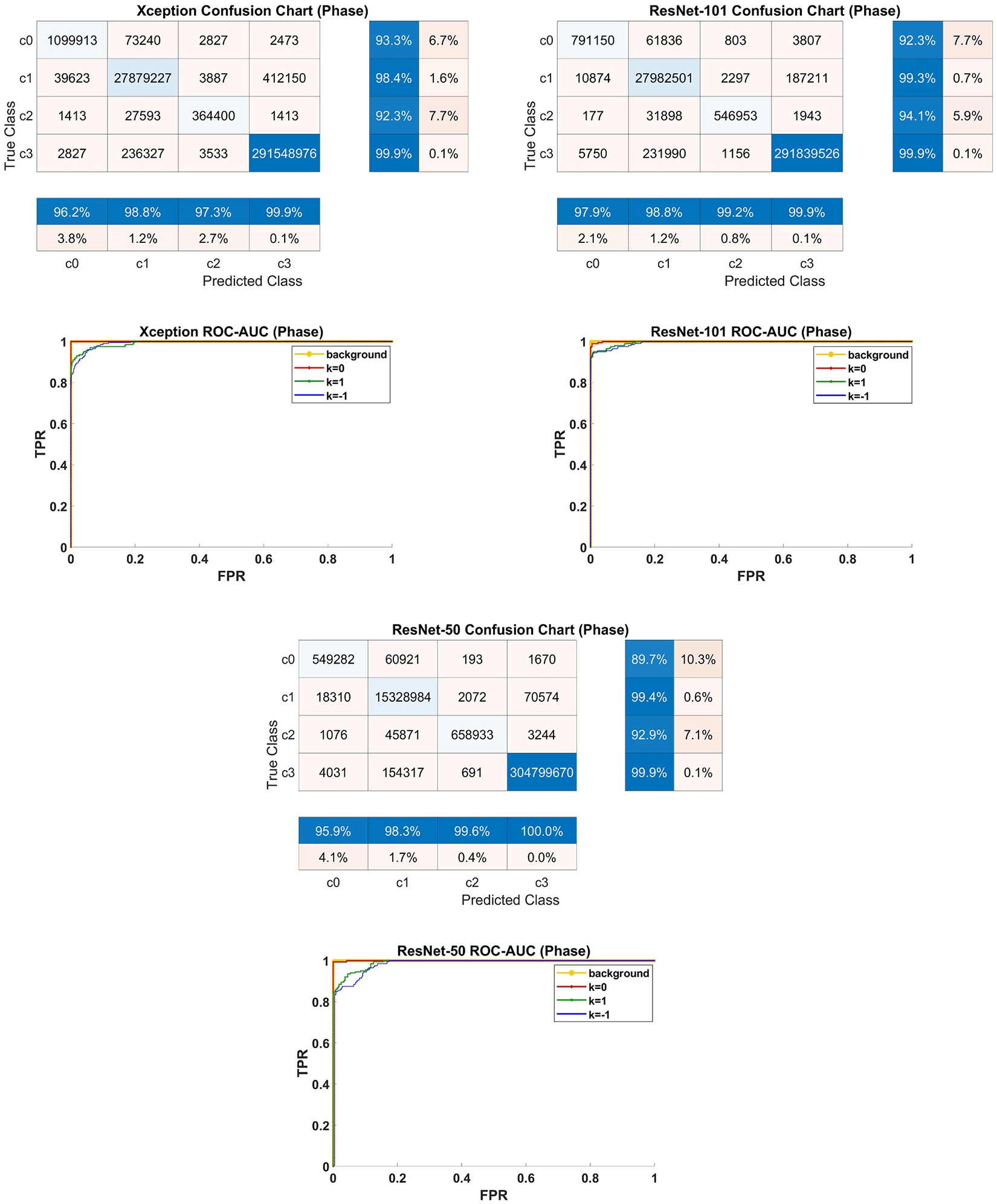

The decision on which DeepLAbV3+ encoder to use for chamber quantification and strain analysis depended on the encoder with which the highest test set segmentation accuracies were achieved. This was ResNet-101 for both FCNs for magnitude and phase image segmentation, with Tables B1–B6 (Supplement B) showing the performance metrics of all six FCNs for segmenting four classes each in the magnitude and phase image test sets. With the ResNet-101 backbone in the FCN for segmenting the magnitude images, a training accuracy >95% and a cross-entropy loss <0.1 after 22,488 iterations and 16.5 h were achieved. Similarly, achieved with the ResNet-101 backbone for phase image segmentation was a training accuracy >95% and a cross-entropy loss <0.1 after 63,021 training iterations and ~ 36 h. Figs. 2–3 show by confusion matrix the precision and recall results of all six FCNs for segmenting the magnitude and phase image test sets. The highest test set scores achieved with ResNet-101 for segmenting the magnitude images were F1 = 0.93 and Dice = 0.93 for the myocardium, and F1 = 0.97 and Dice = 0.96 for LVC, as shown in Table B2. Similarly, the highest test set scores achieved with ResNet-101 for the wrap-count segmentation, k(x, y) = [−1,0,1], in the phase images were F1 = [0.95, 0.99, 0.97] and Dice = [0.90, 0.98, 0.97], as shown in Table B5. The corresponding AUC results (calculated from Figs. 2–3) with the ResNet-101 backbone were 0.99 and 0.97 for segmenting the myocardium and LVC classes in the magnitude images and [0.99, 1.0, 0.99] for segmenting the three wrap-count classes in the phase images.

Fig. 2.

The test set results of segmenting the LV and other anatomy in the DENSE magnitude images in N = 32 patient datasets with the DeepLabV3+ network and three different backbones (Resnet-50, Resnet-101, and Xception).

Fig. 3.

The test set results of segmenting the LV wrap-counts in the DENSE phase images in N = 32 patient datasets with the DeepLabV3+ network and three different backbones (Resnet-50, Resnet-101, and Xception). The wrap-count classes (× 2π) are c0: k = −1 (< 0), c1: k = 0, c2: k = 1 (> 0), c3: background (BG).

Table 2 shows the results of evaluating the DENSE and TEE-derived contractile parameters, the RANOVA comparisons between baseline and the two follow-ups, and the pairwise results between each two time points. It is seen that GLS changed significantly from baseline to the 3-and 6-month follow-ups (−19.1 ± 2.1%, −16.0 ± 3.1%, and −16.1 ± 3.0%; P < 0.001), while the MRI-based and echocardiographic LVEF measurements remained unchanged. Posthoc analysis with a Bonferroni adjustment revealed that GLS significantly increased from baseline to the 3-month follow-up (ΔGLS = 3.1%; 95% CI: 2.1–4.1%; P < 0.001), decreased insignificantly from the 3-month to 6-month follow-ups (ΔGLS = −0.1%; 95% CI: −0.8 – 0.7%; P = 0.83), and therefore, increased significantly from baseline to the 6-month follow-up (ΔGLS = 3.0%; 95% CI: 2.2–3.9%; P < 0.001). Posthoc analysis with a Bonferroni adjustment revealed that apical torsion decreased significantly from baseline to the 3-month follow-up (ΔTORSION = −1.1°; 95% CI: −1.8 - −0.4°; P < 0.001), decreased insignificantly from the 3-month to 6-month follow-up (ΔTORSION = −0.2°; 95% CI: −0.8 – 0.4°; P = 0.6), and therefore, decreased significantly from baseline to the 6-month follow-up (ΔTORSION = −1.3° 95% CI: −2.1 - −0.40°; P = 0.01). The ICC reliability results between DENSE and 2DE-derived LVEF were C-α > 0.95 measured at all three time points and similar good correlations for GLS with C-α = 0.89 at baseline, C-α = 0.93 at 3-months, and C-α = 0.94 at 6-months. In patients whose LVEF remained unchanged over the course of the study, the results of evaluating the LV contractile parameters, the RANOVA comparisons between the three time points, and the pairwise comparisons between each two time points are shown in Table C1, Supplement C. It is seen from the RANOVA p-values and pairwise comparisons in Table C1 that the MRI-based and echocardiographic GLS changed significantly over the 6 months, despite the corresponding unchanged values of LVEF. The ICC reliability results between DENSE and 2DE-derived LVEF and GLS were both C-α > 0.95 at each time point in the subgroup of patients with preserved LVEF. Fig. 4a shows the systolic period magnitude images of a mid-ventricular slice in a patient, overlayed with the myocardium and other labels generated by the FCN with ResNet-101 backbone. Fig. 4b shows the wrapped phase images in this patient in the x, y, and z-directions, overlayed with the wrap-count labels generated by the FCN with ResNet-101 backbone. Fig. 5 shows the Cox PH univariable and bivariable cumulative survival and hazard curves with GLS LVEF, SBP, and HRT that were significantly different at the 3-month follow-up, and Tables D1 and D2 (Supplement D) show the corresponding HR-per-SD and other Cox PH results. The Cox PH univariable regressions in Table D1 show that GLS was independently associated with a 2.1-fold increased risk of a cardiac event occurring per 1-SD higher GLS (HR-per-SD: 2.1; 95% CI: 1.4–3.1; P < 0.001). Table D1 also shows that in bivariable analysis when GLS (HR-per-SD: 2.0; 95% CI: 1.2–3.4; P = 0.01) was adjusted with LVEF (HR-per-SD: 1.0; 95% CI: 0.9–1.2; P = 0.9), it did not contribute significantly to estimating risk, and neither did adjustments with SBP and HRT. Fig. 6 shows the changes in circumferential and longitudinal strains at the three time points in a patient with CTRCD (age = 50.3 years, BMI = 34.2 kg/m2) whose LVEF dropped >5% within a month of starting anthracycline treatment and reached a final LVEF = 30%. Her individual risk analysis showed that the probability of avoiding CTRCD within a month was (1 mo., 44.7%) = 1/5 based on her LVEF, (1 mo., 142.5 mmHg) < 3/5 based on SBP, (1 mo., 78 bpm) = 3/5 based on HRT, and the lowest, (1 mo., −9.5%) <1/10000 based on GLS from the 3-month follow-up. In comparison, in a patient (age = 55.3 years, BMI = 20.3 kg/m2) with more normal clinical and contractile measurements, SBP = 114 mmHg, HRT = 71 bpm, LVEF = 65%, and GLS = −17.0%, at the first follow-up who did not develop CTRCD, all of these prognosticators showed the chances of maintaining normal LV function at >95%. The survival analyses on both patients were conducted with Eq. A5 and the 1-month cumulative hazard and log HR given in Table D2.

Table 2.

Timeline of chamber quantification and 3d strains.

| Chamber Quantification | Intervals | P-value* | Pairwise (0–3 mos.)** | Pairwise (3–6 mos.)** | Pairwise (0–6 mos.)** | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 months | 3 months | 6 months | |||||

| EDD (cm) | 4.6 (0.5) | 4.6 (0.5) | 4.6 (0.5) | .54 | −0.03 (−0.10 – 0.05, .48) | 0.03 (−0.03 – 0.08, .40) | 0.00 (−0.04 – 0.04, .98) |

| ESD (cm) | 3.0 (0.4) | 3.0 (0.4) | 3.0 (0.4) | .95 | 0.00 (−0.02 – 0.02, .84) | 0.00 (−0.05 – 0.05, .98) | 0.00 (−0.05 – 0.04, .90) |

| EDV (ml) | 112.9 (25.8) | 112.1 (25.9) | 112.8 (24.3) | .72 | −0.82 (−4.12 – 2.49, .62) | 0.78 (−1.93 – 3.48, .56) | −0.04 (−1.92 – 1.84, .97) |

| ESV (ml) | 47.6 (12.1) | 47.5 (12.0) | 47.4 (11.3) | .86 | −0.10 (−0.83 – 0.63, .78) | −0.14 (−1.65 – 1.37, .85) | −0.24 (−1.66 – 1.18, .73) |

| SV (ml) | 65.3 (17.3) | 64.6 (17.9) | 65.4 (16.9) | .58 | −0.73 (−3.33 – 1.88, .57) | 0.92 (−1.11 – 2.95, .36) | 0.20 (−1.27 – 1.67, .79) |

| MRILVEF (%) | 58.0 (5.6) | 57.3 (6.6) | 57.8 (6.1) | .40 | −0.65 (−1.44 – 0.14, .10) | 0.44 (−0.69 – 1.58, .42) | −0.21 (−1.32 – 0.91, .71) |

| ECHO LVEF (%) | 58.5 (6.0) | 57.9 (7.2) | 58.3 (6.5) | .41 | −0.63 (−1.35 – 0.08, .10) | 0.41 (−0.70 – 1.52, .39) | −0.18 (−1.23 – 0.81, .70) |

| LVM(g) | 130.1 (15.3) | 129.6 (15.3) | 128.8 (16.8) | .48 | −0.47 (−2.43 – 1.49, .63) | −0.88 (−3.52 – 1.76, .50) | −1.35 (−3.72 – 1.02, .25) |

| Strain | |||||||

| GRS (%) | 33.3 (8.3) | 32.4 (9.2) | 33.1 (8.8) | .51 | −0.86 (−2.53 – 0.80, .30) | 0.64 (−1.11 – 2.40, .46) | −0.22 (−1.55 – 1.11, .74) |

| GCS (%) | −22.5 (5.0) | −22.6 (4.9) | −22.5 (5.2) | .83 | −0.09 (−0.41 – 0.23, .55) | 0.05 (−0.31 – 0.42, .77) | −0.04 (−0.33 – 0.25, .78) |

| MRI GLS (%) | −18.8 (1.5) | −16.1 (2.4) | −16.0 (2.5) | < .001 | 2.71 (1.44 – 3.97, 0.00) | 0.14 (−0.89 – 1.18,1.00) | 2.85 (1.37 – 4.33, < .001) |

| ECHO GLS (%) | −18.6 (2.6) | −16.2 (2.6) | −16.0 (2.6) | < .001 | 2.35 (0.59 – 4.11, 0.01) | 0.21 (−1.33 – 1.75, 1.00) | 2.56 (0.85 – 4.28, < .001) |

| Apical Torsion (°) | 9.5 (3.1) | 8.4 (3.4) | 8.2 (3.4) | < .005 | −1.08 (−1.75 - −0.40, < .001) | −0.17 (−0.77 – 0.43, .57) | −1.25 (−2.09 - −0.41, .01) |

Abbreviations: EDD: end-diastolic diameter, ESD: end-systolic diameter, EDV: end-diastolic volume, ESV: end-systolic volume, SV: stroke volume, LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction, LVM: left ventricular mass, GRS: global radial strain, GCS: global circumferential strain, GLS: global longitudinal strain.

RANOVA P-value between the 3 time point measurements.

Pairwise differences and associated CI and P-values.

Standard deviations given in parenthesis.

Fig. 4.

(a) DeepLabV3+ segmentation and labeling of the magnitude images of the LV into 4 classes: myocardium (green), LV-cavity (red), chest-wall and surrounding anatomy (blue), and chest-cavity (brown), (b) DeepLabV3+ segmentation for unwrapping the LV phase images and labeling according to the three wrap-count classes, yellow: k = −1 (< 0), green: k = 0, forest: k = 1 (> 0) and the background, black: (BG).

Fig. 5.

CTRCD (a) survival and (b) hazard analysis with Cox Proportional Hazards regression in the breast cancer patients with the prognostic factors of GLS, LVEF, SBP, and HRT found significantly changed at the 3-month follow-up.

Fig. 6.

Full-LV surface maps of (a) circumferential and (b) longitudinal strains in a patient with CTRCD whose LVEF dropped from 45% (baseline) and 45% (3-month follow-up) to 30% (6-month follow-up). An early, high variation in absolute GLS was seen, increasing from −16% to −13.5% and −13.8%, but the absolute circumferential strain variation was negligible, remaining at −20%, −19.2%, and 19.5%.

4. Discussion

This study’s primary goal was CTRCD risk analysis with clinical and LV contractile parameters to observe if GLS was an early, independent prognosticator of cardiac dysfunction in breast cancer patients who received antineoplastic chemotherapy treatment. Our prospective study on CTRCD risk analysis is novel, with the contractile prognostic factors (GLS, LVEF, and others) computed from LV motion-encoding with DENSE and FCN methodologies for automated chamber quantification and strain analysis [11, 12]. The main findings from the 3-month follow-up were univariable risk analyses showing SBP, HRT, GLS, and LVEF as significant prognostic factors and bivariable analyses showing GLS as an independent CTRCD prognosticator, irrespective of other covariates. The identification of CTRCD risk factors was aided by following guidelines on the quality in prognostic factors studies, where we (a) conducted research with a collaborative and multi-disciplinary team from cardiology, radiology, and the biomedical sciences and engineering; (b) ensured adequate participation in the study by eligible patients and described those not able to participate or lost to follow-up; (c) used standard, validated scientific techniques for repeated data acquisition and analyses (TEE, DENSE MRI, DeepLabV3+ and RPIM) [11,12]; (d) analyzed CTRCD risk with different Cox PH models with justifications and adjustments for covariates [24,25,47]. In addition, we evaluated three standard DeepLabV3+ encoders for optimal accuracy and used the highest performing ResNet-101 backbone for segmenting both magnitude and phase images (Tables B1–B6 and Figs. 3–4).

Table 1 shows that SBP and HRT were the only parameters in the patient clinical profiles which demonstrated significant differences between the two follow-up measurements. Both SBP and HRT increased significantly from baseline to the 3-month follow-up, but then decreased to near baseline values by the 6-month follow-up, indicating only a temporary, short-term spike in these monitored parameters. This is a finding similar to previous studies also showing short-term changes in hemodynamic parameters with altered SBP (hypertension or hypotension) and HRT (tachycardia) during or just after completing chemotherapy [50,51]. A study with doxorubicin (DX) and cyclophosphamide (CY) adjuvant chemotherapy found acute impairment of neurovascular and hemodynamic responses in female breast cancer patients during the administration of chemotherapy versus saline as a placebo [51]. The authors showed that a single cycle of DX-CY therapy elevated SBP and CTRCD risk, reduced vascular muscle conductance, and increased sympathetic nerve activity in the patients [51]. In a prospective study of similar duration (6 months) on cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction in breast cancer patients, it was shown that anthracycline and trastuzumab chemotherapy was associated with tachycardia, impaired exercise-recovery HRT, and hypotension [50]. The chemotherapy-related tachycardia in a third of patients and hypotension in half of the patients peaked immediately following chemotherapy completion, with both hemodynamic perturbations responding in <10 weeks to moderate intensity aerobic and resistance exercises [50]. Our study shows a longer recovery to baseline for both SBP and HRT, likely due to the absence of prescribed exercises and the unavailability of interim observations between follow-up visits. After reviewing expert consensus, we have deduced that the short-term (3-month follow-up) hemodynamic changes are antineoplastic drug-related elevations that may occur in a chemotherapy-treated subpopulation even when vital parameters remain in the normal range [8,9]. Neither were long-term (nor short-term) treatment-related nephrotoxic effects or renal dysfunction found in the patient cohort, and GFR levels remained within a normal range and unchanged over time, as shown in Table 1. While previous studies show increased risks of cardiotoxicity from trastuzumab in patients with renal dysfunction, the exclusion of patients with chronic kidney disease and metastatic breast cancer most likely contributed to the GFR levels remaining stable over time [52]. Like the clinical measurements in Table 1, most contractile parameters in Table 2 did not change significantly over time (such as MRI and echocardiography-based LVEF) except for the significant changes in GLS (P < 0.001) and apical torsion (P < 0.005). GLS did not revert to baseline at the 6-month follow-up visit, indicating a pattern of significant long-term change in cardiac contraction, which is dissimilar to the short-term changes in the hemodynamic variables. Hence, can we rely on GLS remaining elevated to predict CTRCD in the long term? The answer partly lies in our data showing that CTRCD did occur in patients beyond the first follow-up, as observed from the cumulative increase in risk and decrease in preserved left ventricular function (survival) in Fig. 5. We also predict that monitoring long-term CVD-related morbidity in the patients beyond the 6-month follow-up may establish the significance of a persistently elevated GLS [10,15].

The Cox PH regression results in Table D1 and Fig. 5 summarize the end-point of this study to show the strength of GLS as an independent prognostic factor of CTRCD. It can be seen from the bivariable models that when Cox regression with GLS was adjusted with LVEF, SBP, and HRT, those covariates did not contribute significantly to estimating risk (P = 0.9 for LVEF; P = 0.5 for SBP, and P = 0.07 for HRT). Here, the clinically important finding is CTRCD risk associated with elevated GLS, which may significantly and independently improve CVD risk management in cancer patients receiving treatment with antineoplastic chemotherapy. Higher GLS and lower torsion have similarly been shown in our past studies on post-chemotherapy breast cancer patients compared to healthy subjects, which include studies with similar FCN-based approaches to LV strain analysis [6,12]. Furthermore, we widely searched studies on CTRCD risk assessment with GLS when breast cancer patients received treatment with anthracyclines and trastuzumab [14–16,20]. Among the detailed sources of information on the value of GLS as a prognosticator of subsequent CTRCD are Oikonomou et al.’s [15] meta-analysis and systematic review and Thavendiranathan et al.’s [20] study showing the low sensitivity of risk prediction with LVEF (in comparison to GLS) that inhibit the initiation of cardioprotective therapy (CPT). Additionally, studies by Gripp et al. [23], Guerra et al. [18], Milks et al. [22], and Sawaya et al. [14] have reported increased GLS with high-risk absolute cutoff values ranging from −21.0% to −13.8% as an early indicator of CTRCD risk. In one of those studies, Gripp et al. prospectively observed 49 consecutive breast cancer patients who underwent anthracycline therapy with or without trastuzumab and identified five patients with cardiotoxicity [23]. Like our study, they showed that cardiotoxicity risk was independently associated with the 3-month follow-up GLS (HR-per-SD: 2.8; 95% CI: 1.4–5.5; P = 0.004), with an absolute cutoff value ≥ −16.6% (AUC = 0.95; 95% CI: 0.9–1.0). Guerra et al. studied a cohort of 69 patients with breast carcinoma undergoing adjuvant and neoadjuvant chemotherapy and evaluated GLS with 2D-speckle tracking before beginning chemotherapy and at 3-month follow-ups for one year [18]. Nineteen patients (27%) developed cardiac dysfunction with an average onset time from enrolment of <7 months and a cutoff GLS ≥ −16% measured at a 3-month follow-up after initiating chemotherapy (OR: 24.2; 95% CI: 4.9–119.3) with 80% sensitivity and 90% specificity [15,18]. They also saw after introducing cardioprotective drugs that the alterations in GLS persisted at the 1-year follow-up while LVEF recovered progressively. In their retrospective study, Milks et al. studied 2D echocardiography at clinically determined intervals in a cohort of 183 women with breast cancer aged 50.9 ± 10.8 years who received treatment with anthracyclines, with 41.2% of subjects also receiving trastuzumab [22]. Patients were pooled according to clinical factors for low-to-high risks of CTRCD (7.4% in the low-risk, 26.9% in the intermediate-risk, and 54.6% in the high-risk groups; chi-square = 20.7; P < 0.001), from which the authors developed a novel multivariable model to predict CTRCD using an absolute cutoff GLS ≥ −19% as the only variable for predicting cardiotoxicity (OR: 8.4; 95% CI: 3.7–19.1%) [22].

Given in Table C1 (Supplement C) are the contractile parameters in patients whose LVEF remained preserved during the study period, which also shows the RANOVA results of investigating changes between follow-ups. A significant net increase in GLS found in those patients can be seen in Table C1 despite LVEF preservation. Clinical studies have seen that LVEF reduction caused by chemotherapeutic agents like anthracyclines may take months to years before a change is detected, by when tissue level damage may already be extensive with high chances of irreversible damage from CTRCD [10,53–55]. In contrast, studies show that pre-clinical measurements of troponin to find cell damage, extra-cellular volume (ECV) calculations to identify myocardial tissue remodeling, and CMR-derived GLS showing LV perturbations, can identify early, subclinical cardiac toxicity from chemotherapy [10,53,54,56]. The effect of diagnosing CTRCD with delayed LVEF reduction was seen in the Cardinale et al. study on a significant patient population (N = 2625) receiving anthracycline therapy, which took 12 long months to identify nearly all cases (98%) of cardiotoxicity [56]. The significant end-point outcome of their study was that after initiating CPT with enalapril and beta-blockers, full recovery of LVEF to baseline values occurred in only 11% of patients [56]. Thavendiranathan et al.’s recent study (Strain Surveillance of Chemotherapy for Improving Cardiovascular Outcomes [SUCCOUR]) investigated whether administering CPT (ramipril as ACEi and carvedilol as beta-blockers) in high-risk patients undergoing cardiotoxic chemotherapy was superior for preventing CTRCD in a GLS-guided patient arm (defined as >12% relative GLS reduction from baseline), compared to an LVEF-guided arm (defined as >10% absolute reduction of LVEF) [20,57,58]. The primary findings showed that with significant early indications of relative GLS reductions and greater use of CPT, fewer patients met CTRCD criteria in the GLS-guided arm compared to the LVEF-guided arm (5.8 vs. 13.7%; p = 0.02). Moreover, patients who received CPT in the GLS-guided arm had significantly lower LVEF reduction compared to the LVEF-guided arm (2.9 ± 7.4% vs. 9.1 ± 10.9%; p = 0.03). Our findings, along with the above studies, confirm that LVEF remaining normal does not exclude the risk of CTRCD, which can be identified subclinically as reversible cardiac dysfunction via a relative reduction in GLS [10,53–56]. Furthermore, in this study, the increase (reduction in negative value) seen in GLS is supported by the ICC values showing good reliability between the DENSE and 2DEderived GLS. This finding of inter-modality agreement between CMR techniques, such as CMR-tagging, and 2DE, is consistent with similar outcomes shown in previous studies [60,73]. Amundsen et al. compared peak systolic strain between CMR-tagging and different 2DE modes for LV motion tracking, and showed strong inter-modality agreement between tagging and 2D-STE (95% CI: −12 – 11%, R = 0.59, P<0.001) [60]. Amzulescu et al. prospectively compared peak-systolic global and regional subendocardial Lagrangian longitudinal strain between CMR-tagging and 2D-STE at two centers and found that GLS agreed well (ICC = 0.89 P<0.001) between the modalities [73]. TEE was chosen in contrast to transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) as the preferred method of clinical echocardiographic examination since the latter may sometime be technically inadequate for detecting acute and subacute cardiac CTRCD [63,64]. Better images with TEE are possible because of the closeness of the esophagus to the heart, which means high-frequency sound waves need not pass through extra skin, muscle, or bone and allow for greater spatial resolution of cardiac structures [63–66]. TEE is recommended in chemotherapeutic treatment for clinical cardiac examination to identify CTRCD-related conditions like tachyarrhythmia, atrial fibrillation, pericardial myocarditis, and congestive HF due to systolic dysfunction; when TTE is nondiagnostic due to poor acoustic windows, obesity, or lung disease; or when TEE is the proven superior imaging technique in assessments such as atrioventricular valve (AV) dysfunctions [63–66]. Historically, the agreement shown between 2D TEE and TTE global strains (GLS inclusive) has been moderate-to-good, but agreement between regional strains has been reported as poor [67–69]. The studies reporting the strain agreements believe that the differences in regional strains arise due to differing scanning frequencies and imaging factors mentioned above [67–69]. Hence, we can conclude that TTE-derived GLS would be equally accurate and interchangeable with TEE-derived GLS but cannot surpass the latter for accuracy. An important note is that accurate strain analysis with any 2D echocardiography technique can be influenced by several limiting factors, including through-plane artifacts, poor acoustic windows, poor image quality and varying SNR, and heavy dependence on operator skills [70–73]. In contrast, there are several advantages to LV strain analyzed with 3D navigator-gated, spiral DENSE that uses balanced multi-point displacement encoding applied at pixel intensities in three planar directions and directly quantifies tissue deformation [27,28]. DENSE is considered a gold standard for characterizing 3D global and regional LV systolic strain parallel to CMR-tagging, with excellent inter-technique agreement between the two sequences shown in our studies and others [29,79,80,81]. Deep-learning segmentation of the DENSE images adds further major advantages, including automated boundary detection for volumetric analysis and automated phase-unwrapping for displacement and strain analysis, where the deep networks with image augmentation can accurately identify a heterogeneously appearing organ in any sized patient cohort [11,12,34].

4.1. The clinical utility of GLS for CTRCD diagnosis and treatment

Until now, a specific lack of guidelines on what constitutes a GLS perturbation threshold (absolute or relative) to indicate abnormal LV function, was the primary barrier in cardio-oncology practice for diagnosing subclinical cardiac dysfunction and initiating therapeutic interventions [5,57,58]. Hence, similar to using LVEF guidelines for cardiotoxicity treatment, clinical cardio-oncology studies will need to deeply investigate GLS thresholds that can guide preventive strategies, therapeutic interventions, and any modifications to cancer treatment [8,9]. In this regard, guidelines from the ACC/IC-OS/ASE-EACI consensus or SUCCOUR trial can be used, which defines a 15% relative GLS reduction seen between regular follow-ups for initiation and titration of CPT [20,57,58]. Similar to this study, we can prospectively conduct a new clinical trial over 12 months at 3-month follow-ups from baseline. Cardio-oncology protocols guided by the recommended relative GLS reductions will be added with ACEi and beta-blockers for CPT to normalize LV function [20,57,58]. GLS will be assessed with the validated DENSE-DeepLabV3-RPIM framework, and the reliability of the results verified in comparison to echocardiographic strain values [5,11,12,57]. A prospective study on preventive intervention for cardio-protection can also be initiated by evaluating patients for cardiac risk based on an increased GLS at baseline, similar to prevention studies conducted with LVEF and troponin level thresholds [74–76]. The recent Prevention of Cardiac Dysfunction During Adjuvant Breast Cancer Therapy (PRADA) trial evaluated the cardioprotective effects of metoprolol (beta-blocker) and candesartan (angiotensin II receptor blocker) in 130 breast cancer patients undergoing contemporary doses of 240 mg/m2 anthracyclines [75]. This study demonstrated the benefit of candesartan use in preventing cardiotoxicity, with a less pronounced decrease in LVEF (bias = −0.8%, 95% CI: −1.9 – 0.4%) compared to the metoprolol and placebo groups (bias = −1.6%, 95% CI: −2.8 - −0.4% and bias = −1.8%, 95% CI: −3.0 - −0.7%) [75]. The prospective research study we present here was limited to determining GLS strength for prognosticating CTRCD on a research basis, and hence, cardioprotective drug efficacy to minimize exposure to chemotherapeutic agents could not be investigated. Hence, our next goal is a clinical study on preventive CPT initiated before cancer treatment and guided by the latest GLS thresholds, where we monitor cardiac function in each patient with the DENSE-DeepLabV3-RPIM framework and observe treatment effects at 3-month intervals for a year [11,12,20,57,58]. Finally, at the end of the Results section, we show the benefit of prognosticating individual cardiac safety with GLS in two patients, one who did and one who did not develop CTRCD. The GLS-based low prediction of survival (1 mo., −9.5%) < 1/10000 in the patient who developed CTRCD (Fig. 6) shows that our risk identification model can be tailored to estimate each patient’s chances of cardiac dysfunction that can arise from antineoplastic treatment [22,48,49].

Similar to CTRCD studies, an increasing number of HF-specific studies also show the superiority of GLS over LVEF for prognosticating mortality and other adverse outcome in patients [1,2]. In the largest prospective study to date on patients with chronic HF, GLS was evaluated in a full range of HF syndromes along with other clinical factors and for its prognostic relevance for adverse outcomes in individuals [1]. The main finding of their study was the independent association of follow-up GLS with all-cause mortality (HR-per-SD, 1.6; 95% CI: 1.2–2.0; P <0.001) and cardiac death (HR-per-SD, 2.3; 95% CI: 1.6–3.4; P < 0.001) regardless of clinical profile, HF medications, NYHA class, and cardiac structure and function [1]. HF studies like the above are important to CTRCD research since HF is one of the most dreaded complications of antineoplastic chemotherapy that significantly impact patient care, clinical outcomes, and mortality [77]. As discussed earlier, with a longer clinical trial, this novel CTRCD prognostication tool may enable better cardioprotective strategies, influence decisions to continue or interrupt cancer therapy, and reduce CVD-induced morbidity and mortality.

Thus, sequentially measured GLS appears to be a very sensitive tool to assess LV function in women with breast cancer who begin chemotherapy with agents known to depress cardiac contractility. The present data suggest that LVEF should be abandoned as the parameter to follow in these patients. Although LVEF is easily measured with echocardiography, the unavoidable influence of acoustic windows, operator skill, and poor reproducibility make it an insensitive measure, which can be sub-optimal even with operator-independent MRI technology, as seen in this study [19]. Moreover, the present AI technique can reliably assess GLS in only a few minutes and provides important data to guide medical decisions [11,12].

The first limitation of this study is that this is a single-center study without results from external validation, and data were unavailable in 18% of the patients deemed eligible at our center. However, most small-to-large scale single-center prospective studies and Phase I clinical trials are conducted without multicenter validations and with missing data, which has been reported as high as 49% [1,10]. A second limitation is not integrating CTRCD risk analysis by combining circulating troponin levels with GLS measurements that can be an effective bivariable prognostic approach, as shown in previous studies and which the ACC and IC-OS recommend in their 2022 consensus [8–10]. Our cardiology team is currently reviewing the new guidelines to conduct similar diagnostic tests on outpatient CVD cases, while our health system already monitors troponin levels in patients hospitalized for HF via routine laboratory tests.

5. Conclusion

This prospective study investigated GLS computation with current AI-FCN methodologies as an early, independent prognosticator of LV dysfunction that may progress to CTRCD in breast cancer patients. The 3-month follow-up after chemotherapy confirmed that an elevated, absolute value GLS was an early, independent prognostic factor irrespective of LVEF for predicting CTRCD risk from anthracyclines and trastuzumab-based regimens. By conducting a larger and longer clinical trial to confirm our current observations, there is potential for this new CTRCD risk model with GLS to improve cardiac dysfunction management in breast cancer patients who receive antineoplastic chemotherapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This study was partly funded by the NIH grant 1R21EB028063-03| Recipient: Julia Kar, Ph.D. We are very appreciative of staff at the Imaging Center, Children’s and Women’s Hospital, University of South Alabama for helping us acquire the MRI data. We greatly appreciate Dr. Fredrick Epstein making the DENSE MRI sequence available for our study.

Funding

This study was partly funded by the NIH grant 1R21EB028063-03| Recipient: Julia Kar, Ph.D.| Authorization: 42 USC 241 42 CFR 52| Project End Date: March 31, 2023.

Footnotes

Declarations and Competing Interest

We have read the publisher’s guidance on competing interests and confirm that none of the authors have any competing interests in the manuscript. Neither are there conflicts of interest with any entities within the University of South Alabama or outside including academic institutes, commercial and non-profit organizations.

Ethics approval

Our manuscript does not contain any individual person’s data who is identifiable or is a case study. Hence, requiring them to fill out a consent form for releasing personal details is not applicable.

Knowledge generated

Women who receive anthracyclines and/or trastuzumab have increased risk of developing CTRCD including heart failure, cardiac arrest, cardiomyopathy, stroke, arrhythmia, and thromboembolic disease.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mri.2022.12.015.

Availability of data

Data related to this project can be obtained from the Open Science Framework repository at URL: https://osf.io/3t64z/

DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/3T64Z or upon request to the corresponding author, Julia Kar, Ph.D., jkar@southalabama.edu

References

- [1].Tröbs SO, Prochaska JH, Schwuchow-Thonke S, Schulz A, Müller F, Heidorn MW, et al. Association of global longitudinal strain with clinical status and Mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. JAMA Cardiol 2021;6(4):448–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bertini M, Ng AC, Antoni ML, Nucifora G, Ewe SH, Auger D, et al. Global longitudinal strain predicts long-term survival in patients with chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Imag 2012;5(3):383–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Smiseth OA, Torp H, Opdahl A, Haugaa KH, Urheim S. Myocardial strain imaging: how useful is it in clinical decision making? Eur Heart J 2016;37(15):1196–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Mehta LS, Watson KE, Barac A, Beckie TM, Bittner V, Cruz-Flores S, et al. Cardiovascular disease and breast cancer: where these entities intersect: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018;137(8):e30–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Liu Jennifer E, Barac A, Thavendiranathan P, Scherrer-Crosbie M. Strain Imag Cardio-Oncol JACC: CardioOncol 2020;2(5):677–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kar J, Cohen MV, McQuiston SA, Figarola MS, Malozzi CM. Can post-chemotherapy cardiotoxicity be detected in long-term survivors of breast cancer via comprehensive 3D left-ventricular contractility (strain) analysis? Magn Reson Imaging 2019;62:94–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kar J, Cohen MV, McQuiston SA, Figarola MS, Malozzi CM. Fully automated and comprehensive MRI-based left-ventricular contractility analysis in post-chemotherapy breast cancer patients. Br J Radiol 2020;93(1105):20190289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Herrmann J, Lenihan D, Armenian S, Barac A, Blaes A, Cardinale D, et al. Defining cardiovascular toxicities of cancer therapies: an international cardio-oncology society (IC-OS) consensus statement. Eur Heart J 2022;43(4):280–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hayek S Defining cardiovascular toxicities of cancer therapies: consensus statement. American college of. Cardiology 2022:1. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Cardinale D, Iacopo F, Cipolla CM. Cardiotoxicity of anthracyclines. Front Cardiovasc Med 2020:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kar BJ, Cohen MV, McQuiston SP, Malozzi CM. A deep-learning semantic segmentation approach to fully automated MRI-based left-ventricular deformation analysis in cardiotoxicity. Magn Reson Imaging 2021;78:127–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kar J, Cohen MV, McQuiston SA, Poorsala T, Malozzi CM. Direct left-ventricular global longitudinal strain (GLS) computation with a fully convolutional network. J Biomech 2022;130:110878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Greenlee H, Iribarren C, Rana JS, Cheng R, Nguyen-Huynh M, Rillamas-Sun E, et al. Risk of cardiovascular disease in women with and without breast cancer: the pathways heart study. J Clin Oncol 2022;40(15):1647–58. 10.1200/JCO.21.01736. Epub 2022 Apr 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Sawaya H, Sebag IA, Plana JC, Januzzi JL, Ky B, Cohen V, et al. Early detection and prediction of cardiotoxicity in chemotherapy-treated patients. Am J Cardiol 2011; 107(9):1375–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Oikonomou EK, Kokkinidis DG, Kampaktsis PN, Amir EA, Marwick TH, Gupta D, et al. Assessment of prognostic value of left ventricular global longitudinal strain for early prediction of chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Cardiol 2019;4(10):1007–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Thavendiranathan P, Poulin F, Lim KD, Plana JC, Woo A, Marwick TH. Use of myocardial strain imaging by echocardiography for the early detection of cardiotoxicity in patients during and after cancer chemotherapy: a systematic review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63(25 Pt A):2751–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tuzovic M, Yang E, Witteles R. Summary of clinical trials for the prevention and treatment of cardiomyopathy related to anthracyclines and HER2-targeted agents. American College of Cardiology; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Guerra F, Marchesini M, Contadini D, Menditto A, Morelli M, Piccolo E, et al. Speckle-tracking global longitudinal strain as an early predictor of cardiotoxicity in breast carcinoma. Support Care Cancer 2016;24(7):3139–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Plana JC, Galderisi M, Barac A, Ewer MS, Ky B, Scherrer-Crosbie M, et al. Expert consensus for multimodality imaging evaluation of adult patients during and after cancer therapy: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2014;27 (9):911–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Thavendiranathan P, Negishi T, Somerset E, Negishi K, Penicka M, Lemieux J, et al. Strain-guided management of potentially cardiotoxic cancer therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021;77(4):392–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Araujo-Gutierrez R, Chitturi KR, Xu J, Wang Y, Kinder E, Senapati A, et al. Baseline global longitudinal strain predictive of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity. Cardiooncology 2021;7(1):4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Milks MW, Velez MR, Mehta N, Ishola A, Van Houten T, Yildiz VO, et al. Usefulness of integrating heart failure risk factors into impairment of global longitudinal strain to predict anthracycline-related cardiac dysfunction. Am J Cardiol 2018;121 (7):867–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Gripp EA, Oliveira GE, Feijo LA, Garcia MI, Xavier SS, Sousa AS. Global longitudinal strain accuracy for cardiotoxicity prediction in a cohort of breast cancer patients during anthracycline and/or Trastuzumab treatment. Arq Bras Cardiol 2018;110(2):140–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Cox DR, Oakes D. Analysis of survival data. New York: Chapman & Hall; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Riley RD, Moons KGM, Snell KIE, Ensor J, Hooft L, Altman DG, et al. A guide to systematic review and meta-analysis of prognostic factor studies. BMJ 2019;364: k4597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kar J, Cupps B, Zhong X, Koerner D, Kulshrestha K, Neudecker S, et al. Preliminary investigation of multiparametric strain Z-score (MPZS) computation using displacement encoding with simulated echoes (DENSE) and radial point interpretation method (RPIM). J Magn Reson Imaging 2016;44(4):993–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Zhong X, Gibberman LB, Spottiswoode BS, Gilliam AD, Meyer CH, French BA, et al. Comprehensive cardiovascular magnetic resonance of myocardial mechanics in mice using three-dimensional cine DENSE. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2011;13:83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Zhong X, Spottiswoode BS, Meyer CH, Kramer CM, Epstein FH. Imaging three-dimensional myocardial mechanics using navigator-gated volumetric spiral cine DENSE MRI. Magnet Reson Med: Off J Soc Magnet Reson Med/Soc Magnet Reson Med 2010;64(4):1089–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kar J, Knutsen AK, Cupps BP, Zhong X, Pasque MK. Three-dimensional regional strain computation method with displacement encoding with stimulated echoes (DENSE) in non-ischemic, non-valvular dilated cardiomyopathy patients and healthy subjects validated by tagged MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 2015;41(2): 386–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lundervold AS, Lundervold A. An overview of deep learning in medical imaging focusing on MRI. Z Med Phys 2019;29(2):102–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Krizhevsky A, Sutskever I, Hinton GE. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun ACM 2017;60(6):84–90. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Long J, Shelhamer E, Darrell T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. In: 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2015. p. 3431–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Szegedy C, Ioffe S, Vanhoucke V, Alemi A. Inception-v4, inception-ResNet and the impact of residual connections on learning. In: Proceedings of the Thirty-First AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. San Francisco, California, USA; 2017. p. 4278–84. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Chen C, Qin C, Qiu H, Tarroni G, Duan J, Bai W, et al. Deep learning for cardiac image segmentation: a review. Front Cardiovasc Med 2020;7:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Chen LC, Papandreou G, Kokkinos I, Murphy K, Yuille AL. DeepLab: semantic image segmentation with deep convolutional nets, Atrous convolution, and fully connected CRFs. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell 2018;40(4):834–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Chen L-C, Papandreou G, Schroff F, Adam H. Rethinking atrous convolution for semantic image segmentation. ArXiv 2017;Volume: abs/1706.05587.:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Henglin M, Stein G, Hushcha PV, Snoek J, Wiltschko AB, Cheng S. Machine learning approaches in cardiovascular imaging. Circul: Cardiovasc Imag 2017;10 (10):e005614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Chen LC, Zhu Y, Papandreou G, Schroff F, Adam H. Encoder-Decoder with Atrous Separable Convolution for Semantic Image Segmentation. In: Ferrari V, Hebert M, Sminchisescu C, Weiss Y, editors. Computer Vision – ECCV 2018. ECCV. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 11211 Springer, Cham; 2018. p. 833–59. 10.1007/978-3-030-01234-2_49. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [39].He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition; 2016. p. 770–8. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Spoorthi GE, Gorthi S, Gorthi RK. A Deep Learning-based Model for Phase Unwrapping. In: Proceedings of the 11th Indian Conference on Computer Vision, Graphics and Image Processing; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Kim D, Gilson WD, Kramer CM, Epstein FH. Myocardial tissue tracking with two-dimensional cine displacement-encoded MR imaging: development and initial evaluation. Radiology 2004;230(3):862–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].MathWorks. Deep Learning Toolbox: Design, train, and analyze deep learning networks. Available from: https://www.mathworks.com/products/deep-learning.html; 2020. [Accessed December 1 2020].

- [43].Chollet F Xception: deep learning with depthwise separable convolutions. In: Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition.; 2017. p. 1251–8. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Kar J, Cohen MV, McQuiston SA, Malozzi CM. Comprehensive enhanced methodology of an MRI-based automated left-ventricular chamber quantification algorithm and validation in chemotherapy-related cardiotoxicity. J Med Imaging (Bellingham) 2020;7(6):064002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Kar J, Zhong X, Cohen MV, Cornejo DA, Yates-Judice A, Rel E, et al. Introduction to a mechanism for automated myocardium boundary detection with displacement encoding with stimulated echoes (DENSE). Br J Radiol 2018;91(1087)):20170841. 10.1259/bjr.20170841. Epub 2018 May 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Asgeirsson D, Hedström E, Jögi J, Pahlm U, Steding-Ehrenborg K, Engblom H, et al. Longitudinal shortening remains the principal component of left ventricular pumping in patients with chronic myocardial infarction even when the absolute atrioventricular plane displacement is decreased. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2017;17 (1):208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Riley RD, Sauerbrei W, Altman DG. Prognostic markers in cancer: the evolution of evidence from single studies to meta-analysis, and beyond. Br J Cancer 2009;100 (8):1219–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Romond EH, Jeong J-H, Rastogi P, Swain SM, Geyer CE Jr, Ewer MS, et al. Seven-year follow-up assessment of cardiac function in NSABP B-31, a randomized trial comparing doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel (ACP) with ACP plus trastuzumab as adjuvant therapy for patients with node-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012;30 (31):3792–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Upshaw JN, Ruthazer R, Miller KD, Parsons SK, Erban JK, O’Neill AM, et al. Personalized decision making in early stage breast cancer: applying clinical prediction models for anthracycline cardiotoxicity and breast Cancer mortality demonstrates substantial heterogeneity of benefit-harm trade-off. Clin Breast Cancer 2019;19(4). 259–67.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Kirkham AA, Lloyd MG, Claydon VE, Gelmon KA, McKenzie DC, Campbell KL. A longitudinal study of the Association of Clinical Indices of cardiovascular autonomic function with breast cancer treatment and exercise training. Oncologist 2019;24(2):273–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Sales ARK, Negrão MV, Testa L, Ferreira-Santos L, Groehs RVR, Carvalho B, et al. Chemotherapy acutely impairs neurovascular and hemodynamic responses in women with breast cancer. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2019;317(7):H1–h12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Lameire N Nephrotoxicity of recent anti-cancer agents. Clin Kidney J 2014;7(1): 11–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Houbois CP, Nolan M, Somerset E, Shalmon T, Esmaeilzadeh M, Lamacie MM, et al. Serial cardiovascular magnetic resonance strain measurements to identify cardiotoxicity in breast cancer: comparison with echocardiography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2021;14(5):962–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Harries I, Berlot B, Ffrench-Constant N, Williams M, Liang K, De Garate E, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance characterisation of anthracycline cardiotoxicity in adults with normal left ventricular ejection fraction. Int J Cardiol 2021;343:180–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Jensen BV, Skovsgaard T, Nielsen SL. Functional monitoring of anthracycline cardiotoxicity: a prospective, blinded, long-term observational study of outcome in 120 patients. Ann Oncol 2002;13(5):699–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Cardinale D, Cipolla CM. Chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity: importance of early detection. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2016;14(12):1297–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Negishi T, Thavendiranathan P, Negishi K, Marwick TH, Aakhus S, Murbræch K, et al. Rationale and Design of the Strain Surveillance of chemotherapy for improving cardiovascular outcomes: the SUCCOUR trial. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2018;11(8):1098–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Barac A Optimal treatment of stage B heart failure in cardio-oncology?: the promise of strain*. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2018;11(8):1106–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Amundsen BH, Crosby J, Steen PA, Torp H, Slørdahl SA, Støylen A. Regional myocardial long-axis strain and strain rate measured by different tissue Doppler and speckle tracking echocardiography methods: a comparison with tagged magnetic resonance imaging. Eur J Echocardiogr 2009;10(2):229–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Vitarelli A, Gheorghiade M. Transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography in the hemodynamic assessment of patients with congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol 2000;86(4, Supplement 1):36–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Jain D, Russell RR, Schwartz RG, Panjrath GS, Aronow W. Cardiac complications of Cancer therapy: pathophysiology, identification, prevention, treatment, and future directions. Curr Cardiol Rep 2017;19(5):36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Guglin M, Aljayeh M, Saiyad S, Ali R, Curtis AB. Introducing a new entity: chemotherapy-induced arrhythmia. EP Europace 2009;11(12):1579–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Kamphuis JAM, Linschoten M, Cramer MJ, Doevendans PA, Asselbergs FW, Teske AJ. Early- and late anthracycline-induced cardiac dysfunction: echocardiographic characterization and response to heart failure therapy. Cardio-Oncology 2020;6(1):23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Marcucci CE, Samad Z, Rivera J, Adams DB, Philips-Bute BG, Mahajan A, et al. A comparative evaluation of transesophageal and transthoracic echocardiography for measurement of left ventricular systolic strain using speckle tracking. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2012;26(1):17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Kurt M, Tanboga IH, Isik T, Kaya A, Ekinci M, Bilen E, et al. Comparison of transthoracic and transesophageal 2-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2012;26(1):26–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Simmons LA, Weidemann F, Sutherland GR, D’Hooge J, Bijnens B, Sergeant P, et al. Doppler tissue velocity, strain, and strain rate imaging with transesophageal echocardiography in the operating room: a feasibility study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2002;15(8):768–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Amzulescu MS, De Craene M, Langet H, Pasquet A, Vancraeynest D, Pouleur AC, et al. Myocardial strain imaging: review of general principles, validation, and sources of discrepancies. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2019;20(6):605–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Ünlü S, Duchenne J, Mirea O, Pagourelias ED, Bézy S, Cvijic M, et al. Impact of apical foreshortening on deformation measurements: a report from the EACVI-ASE strain standardization task force. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2019;21(3): 337–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Mirea O, Pagourelias ED, Duchenne J, Bogaert J, Thomas JD, Badano LP, et al. Intervendor differences in the accuracy of detecting regional functional abnormalities: a report from the EACVI-ASE strain standardization task force. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2018;11(1):25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Amzulescu MS, Langet H, Saloux E, Manrique A, Boileau L, Slimani A, et al. Head-to-head comparison of global and regional two-dimensional speckle tracking strain versus cardiac magnetic resonance tagging in a multicenter validation study. Circ Cardiovasc Imag 2017;10(11). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Pituskin E, Mackey JR, Koshman S, Jassal D, Pitz M, Haykowsky MJ, et al. Multidisciplinary approach to novel therapies in cardio-oncology research (MANTICORE 101-breast): a randomized trial for the prevention of Trastuzumab-associated cardiotoxicity. J Clin Oncol 2017;35(8):870–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]