Abstract

In 2018, data from a surveillance study in Botswana evaluating adverse birth outcomes raised concerns that women on antiretroviral therapy (ART) containing dolutegravir (DTG) may be at increased risk for neural tube defects (NTDs). The mechanism of action for DTG involves chelation of Mg2+ ions in the active site of the viral integrase. Plasma Mg2+ homeostasis is maintained primarily through dietary intake and reabsorption in the kidneys. Inadequate dietary Mg2+ intake over several months results in slow depletion of plasma Mg2+ and chronic latent hypomagnesemia, a condition prevalent in women of reproductive age worldwide. Mg2+ is critical for normal embryonic development and neural tube closure. We hypothesized that DTG therapy might slowly deplete plasma Mg2+ and reduce the amount available to the embryo, and that mice with pre-existing hypomagnesemia due to genetic variation and/or dietary Mg2+ insufficiency at the time of conception and initiation of DTG treatment would be at increased risk for NTDs. We used two different approaches to test our hypothesis: 1) we selected mouse strains that had inherently different basal plasma Mg2+ levels and 2) placed mice on diets with different concentrations of Mg2+. Plasma and urine Mg2+ were determined prior to timed mating. Pregnant mice were treated daily with vehicle or DTG beginning on the day of conception and embryos examined for NTDs on gestational day 9.5. Plasma DTG was measured for pharmacokinetic analysis. Our results demonstrate that hypomagnesemia prior to conception, due to genetic variation and/or insufficient dietary Mg2+ intake, increases the risk for NTDs in mice exposed to DTG. We also analyzed whole-exome sequencing data from inbred mouse strains and identified 9 predicted deleterious missense variants in Fam111a that were unique to the LM/Bc strain. Human FAM111A variants are associated with hypomagnesemia and renal Mg2+ wasting. The LM/Bc strain exhibits this same phenotype and was the strain most susceptible to DTG-NTDs. Our results suggest that monitoring plasma Mg2+ levels in patients on ART regimens that include DTG, identifying other risk factors that impact Mg2+ homeostasis, and correcting deficiencies in this micronutrient might provide an effective strategy for mitigating NTD risk.

Keywords: dolutegravir, antiretroviral therapy, gene-nutrient interactions, neural tube defect, magnesium, hypomagnesemia, maternal diet, FAM111A

1 Introduction

Neural tube defects (NTDs) are congenital malformations of the brain and/or spinal cord (anencephaly, spina bifida) that result from failure of the neural tube to close properly during early embryonic development. The etiology of NTDs is multifactorial, involving complex gene-nutrient-environment interactions. Numerous factors that contribute to NTDs are known, including maternal nutritional deficiencies, metabolic disorders (diabetes, obesity), genetic variants, environmental toxins, and pharmaceutical exposures (Finnell et al., 2021; Isaković et al., 2022). It has also been established that the occurrence (Czeizel and Dudas, 1992) or recurrence (MRC Vitamin Study Research Group, 1991; Toriello, 2011; Atta et al., 2016) of NTD-affected pregnancies can be effectively reduced by periconceptional use of folic acid supplements. However, to implement additional strategies for NTD prevention, the continued identification of modifiable or actionable risk factors is critical.

In 2018, a surveillance study in Botswana evaluating adverse birth outcomes among women on different antiretroviral therapy (ART) regimens reported a 9-fold increase in the prevalence of NTDs among women who began treatment with dolutegravir (DTG) prior to conception (Zash et al., 2018). DTG is a second-generation Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitor (INSTI) used to treat patients living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) (Shah et al., 2014). In the Botswana Tsepamo Study, NTDs reported for 4/426 (.94%) infants exposed to DTG from conception included encephalocele, myelomeningocele, iniencephaly, and anencephaly. These findings raised significant concern among scientific and medical communities, prompting the World Health Organization (WHO) to review the existing data and reevaluate guidelines for use of DTG in pregnant women. When an unexpected NTD ‘safety signal’ is raised for a new medication, the potential role of maternal folate deficiency and other known risk factors are considered. However, due to the multifactorial nature of NTDs, additional elements that might tip the balance to create the ‘perfect storm’ can often be elusive.

In response to the safety alert, the Botswana Harvard AIDS Partnership conducted a larger follow-up study, and found that the prevalence of DTG-NTDs (5/1683 deliveries, .30%) was lower than in the original report, although still elevated compared to other ART regimens (.10%) (Zash et al., 2019). Notably, in all 5 of the NTD-affected pregnancies, DTG therapy was initiated more than 3 months prior to conception (Zash et al., 2022). The use of folic acid supplements did not differ across groups, and no other confounders were present. Based on this new evidence, and a risk-benefit assessment, the WHO again recommended DTG as the preferred first (and second)-line ART for all adults, including women of reproductive age and women who are pregnant or breastfeeding (WHO, 2019).

The preclinical embryo-fetal development (EFD) studies found no significant evidence of DTG-related maternal or developmental toxicity when pregnant animals were administered oral doses of DTG up to 1000 mg/kg/d (Stanislaus et al., 2020). Animals were exposed to DTG beginning on gestational day (GD) 6 and continuing until GD 17 (rats) or GD 18 (rabbits). DTG exposure in both species occurred post-conception, but prior to neurulation and organogenesis. The use of animal models for pre-market testing of new drugs is often a reliable predictor of potential adverse birth outcomes in humans (Koren et al., 1998). Experimental variables (genetic background, diet, husbandry, timing of exposure) in such studies are well-controlled. However, numerous confounding variables exist in human populations, making it difficult to evaluate and/or predict in a laboratory setting the complex interactions that may ultimately culminate in failure of neural tube closure. Post-marketing pharmacovigilance is therefore necessary to further evaluate the safety of new medications in pregnant women, and additional investigation is warranted when a safety signal is identified.

After the report from the Tsepamo Study was released, several laboratories conducted investigations using animal or cell-based models to examine potential adverse effects of DTG, most of which focused on the folate pathway. Studies in Madin-Darby canine kidney II cells did not find a significant DTG or INSTI class effect on inhibition of folate transport (Zamek-Gliszczynski et al., 2019). In contrast, DTG partially inhibited FOLR1-mediated uptake of folic acid in human placental trophoblast cells (Cabrera et al., 2019), and reduced FOLR1-mediated uptake in human choriocarcinoma cells (Gilmore et al., 2022). Significant mortality occurred in zebrafish embryos when DTG exposure was initiated at 3 h post-fertilization, but not when exposure began later in gastrulation-stage embryos, and mortality could be rescued by supplemental folic acid (Cabrera et al., 2019).

In 2 different human embryonic stem cell (hESC) lines, DTG exposure resulted in cytotoxicity and a dose-dependent loss of pluripotency (Smith et al., 2022). In a 3-dimensional (3D) hESC morphogenesis model, exposure to DTG caused altered growth and expression of genes involved in body patterning (Kirkwood-Johnson et al., 2021). DTG was also tested in a pluripotent P19C5 mouse embryonal carcinoma cell 3D morphogenesis model validated for the study of developmental toxicants (Marikawa et al., 2020; Warkus and Marikawa, 2017). When DTG exposure occurred within the first 1–2 days (corresponding to pre/early gastrulation), changes were observed in the expression of genes involved in axial patterning. A concentration-dependent inhibition of growth and axial elongation was also observed, but not when DTG exposure was initiated later in development (2–4 days) (Kirkwood-Johnson et al., 2021). In this study, supplementation with folic or folinic acid did not demonstrate a protective effect nor restore normal morphogenesis.

Additional studies were conducted using rodent models. Whole rat embryos were cultured ex vivo and exposed to DTG during the window of neurulation (GD 9–11] (Posobiec et al., 2021). DTG concentrations used were approximately 2 times higher than the plasma concentration reported for the maximum recommended human dose (MRHD) of 50 mg DTG twice daily, but no developmental toxicity or NTDs were observed (Posobiec et al., 2021). However, a limited number of studies in mice have been able to demonstrate a positive connection between DTG and NTDs. In C57BL/6J mice, 2.5 mg/kg/d oral DTG (co-formulated with tenofovir [TDF] and emtricitabine [FTC]) was found to yield peak plasma DTG concentrations (Cmax) that approximate human plasma concentrations. Mice were maintained on a folate-sufficient diet, and DTG exposure began at the time of conception (GD 0.5). This treatment regime yielded 5/150 NTD-affected litters (3.3%), with n = 1 NTD/affected litter (Mohan et al., 2021); however, no NTDs were observed in n = 111 litters from dams treated with a 5x higher dose. Another study in C3H/HeJ mice found 1 NTD affected pup in 17 litters examined (5.8%) when pregnant dams were given 50 mg/kg/d DTG oral gavage beginning on GD 0.5 (Bade et al., 2021). In pregnant C57BL/6J mice maintained on a folate-deficient diet administered oral 12.5 mg/kg/d DTG beginning on GD 0.5, modest changes in mRNA transcript levels of folate transporters (upregulation of Rfc1 and downregulation of Folr1) were detected in GD 10.5 placentas (just after neural tube closure); however, when the mice were maintained on a folate-sufficient diet, a modest increase in Folr1 mRNA occurred only at the 2.5 mg/kg/d DTG dose, and no changes were observed at the 5x higher dose (Gilmore et al., 2022).

Collectively, key findings from human, cell-based, and animal studies demonstrate an important connection between very early (pre-gastrulation) exposure to DTG and potential for disruption of morphogenesis, axial patterning, gastrulation, and neural tube closure. Nonetheless, studies evaluating a possible connection between DTG and folic acid rescue or altered transport of folic acid in different models have yielded variable results, suggesting the relationship between DTG and folate may be indirect, rather than direct. In published in vivo mouse models of DTG-NTDs, the DTG dose(s) used were calculated to approximate or slightly exceed human exposure based on established plasma levels in patients. However, the % of NTD-affected litters and the mean litter rate was small, which would make it difficult to detect with any certainty whether maternal folate supplementation in vivo has a protective effect.

In the current study we decided to focus on the potential role of a different micronutrient as a risk factor for DTG-NTDs, based on the known mechanism of action for the INSTI class of ART. DTG and other INSTIs chelate two magnesium (Mg2+) ions in the active site of the HIV integrase, inhibiting its catalytic activity and preventing incorporation of viral DNA into the host genome (Kawasuji et al., 2006; Barreca et al., 2009). Mg2+ is found in foods such as nuts, whole grains, and seeds, and is an important co-factor for hundreds of enzymatic reactions in the body (Mathew and Panonnummal, 2021; Jahnen-Dechent and Ketteler, 2012). In plasma, ∼60–70% of Mg2+ is ionized (Rosanoff et al., 2022), and homeostasis is regulated primarily by Mg2+ absorption in the small intestine and reabsorption in the kidneys (Schuchardt and Hahn, 2017; Claverie-Martin et al., 2021). Hypomagnesemia (<.7 mml/L) can lead to cardiac arrhythmias, and seizures (de Baaij et al., 2015) and is implicated in the pathogenesis of obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [reviewed in Pelczynska et al., 2022].

In humans, chronic latent hypomagnesemia is not uncommon, and undetected (subclinical) Mg2+ deficiency is prevalent in women of childbearing age worldwide (Dalton et al., 2016). Inadequate Mg2+ intake over a period of several months leads to slow depletion of serum Mg2+ that may not be recognized clinically, even in cases of severe hypomagnesemia (Elin, 1988). Analysis of NHANES (2003–2014) data revealed that women living with HIV in the United States not only had lower serum folate levels, but also lower intake of Mg2+ than women who were not infected (Thuppal et al., 2017). In the U.S., only ∼66% of prenatal vitamin supplements contain Mg2+, and only 5% of those on the market meet or exceed the 350–400 mg/day recommended daily amount (RDA) for pregnant women (Adams et al., 2021). Women of reproductive age living with HIV in resource-limited countries are likely to be at increased risk for undernutrition and consumption of poor-quality diets deficient in folate and other micronutrients, including magnesium (Darnton-Hill and Mkaru, 2015).

Two of the major transporters involved in regulating Mg2+ homeostasis in the body are the transient receptor potential melastatin (TRPM) divalent-selective ion channels TRPM6 and TRPM7 (Voets et al., 2004; Chubanov et al., 2005; Groenestege et al., 2006; Schlingmann and Gudermann, 2005; Schlingmann et al., 2007). In the mouse embryo, these 2 Mg2+ transporters also play critical non-redundant roles in cell movement during gastrulation and neurulation (Liu et al., 2011; Komiya et al., 2014; Komiya and Runnels, 2015; Komiya et al., 2017; Runnels and Komiya, 2020): Trpm7 knockout mice initiate gastrulation but die in utero between GD 6.5–7.5 (Jin et al., 2008), while Trpm6 knockout mice exhibit NTDs (Walder et al., 2009). Transport of adequate Mg2+ from maternal blood across the placenta to the developing embryo is essential for normal embryonic development and neural tube closure (Chubanov et al., 2016). In mice, Mg2+ deficiency or insufficiency during pregnancy causes placental abnormalities, growth restriction, and increased fetal mortality (Schlegel et al., 2015). In human studies, low maternal dietary intake of Mg2+ increased risk for spina bifida (Groenen et al., 2004) while, in contrast, periconceptional dietary intake of foods rich in magnesium decreased risk for NTDs (Shaw et al., 1999).

Based on the known mechanism of action for DTG (Mg2+ chelation) and the importance of Mg2+ in neural tube closure, we hypothesized that if DTG administration was initiated at conception, slow depletion of ionized Mg2+ in maternal plasma might occur over time, reducing the amount available for transport across the placenta as the pregnancy progressed. In dams unable to compensate and maintain Mg2+ homeostasis through increased dietary intake and/or increased renal reabsorption, the level of available Mg2+ might be inadequate to support normal neural tube closure. In addition, the unbound fraction of DTG that crosses the placenta might chelate Mg2+ present in coelomic or amniotic fluid and/or embryonic tissues. We hypothesized that in mice with pre-existing (subclinical) hypomagnesemia due to genetic variation and/or dietary Mg2+ insufficiency at the time of conception/initiation of DTG treatment, Mg2+ levels would be more likely to drop below a critical threshold before the onset of neurulation. In other words, in mice with underlying nutritional and/or genetic risk factors that compromise Mg2+ homeostasis but still allow embryogenesis to proceed normally, the addition of DTG might ‘tip the balance’ to create the perfect storm for development of NTDs.

To test our hypothesis concerning pre-existing perturbations in Mg2+ homeostasis as an underlying risk factor for DTG-NTDs, we selected 3 mouse strains on different genetic backgrounds that had inherently different basal plasma Mg2+ levels, ranging from low (subclinical hypomagnesemia) to high. In the first set of experiments, these 3 mouse strains were maintained on the same diet and administered the same dose of DTG. Litter outcomes were compared across strains for susceptibility to DTG-NTDs based on genetic variation in plasma and urine Mg2+ levels. In the second set of experiments, we placed mice on diets with different concentrations of Mg2+ (deficient, control, high) to examine the effect of reduced dietary Mg2+ intake on susceptibility to DTG-NTDs. In both experiments, plasma and urine Mg2+ levels were determined before mice were placed into timed mating. Dams were treated with vehicle or DTG by daily oral gavage, beginning on GD 0.5, and embryos examined for NTDs on GD 9.5. Plasma DTG levels were measured for pharmacokinetic (PK) analysis. In a third experiment, we analyzed whole-exome sequencing (WES) data from our inbred mouse strains to determine if the strain most susceptible to DTG-NTDs had variants in genes involved in Mg2+ homeostasis.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Selection of mouse strains

Mouse strains were selected for testing based on predicted basal plasma levels of magnesium reported in the Jackson Laboratory Mouse Phenome Database (Yuan et al., 2008). The C3H/HeJ strain was selected for low (0.90 mml/L) serum Mg2+ and the C57BL/6J strain for high (1.19 mmol/L) serum Mg2+. These 2 strains were purchased from Jackson Labs (Bar Harbor, ME). The SWV and LM/Bc (on C3H background (Harris et al., 1984)) strains were also tested. These 2 inbred strains have been maintained as closed colonies by the van Waes lab for >20 years and used extensively for teratology studies.

2.2 Animal husbandry and timed matings

Breeding colonies and experimental mice were housed in Thoren micro-isolator cages with autoclaved corncob bedding and maintained on a 12-h light-dark cycle in climate-controlled AAALAC-accredited animal facilities at Creighton University. Mice were given ad libitum access to autoclaved water and pelleted irradiated rodent chow. For timed matings, nulliparous female mice were placed with a male overnight (1 male:2-3 females). The presence of a vaginal plug the next morning was considered GD 0.5. Plugged females were weighed, placed into a separate cage, and randomly assigned to a treatment group. All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the Public Health Service (PHS) policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Creighton University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

2.3 Dolutegravir: Route of administration, dose selection, and gestational window of exposure

2.3.1 Route and timing of administration

Dolutegravir (CAS 1051375-16-6, GSK1349572) was purchased from MedKoo Biosciences (Morrisville, NC). Pregnant mice were dosed with vehicle (dimethylsulfoxide: Solutol®: 50 mM N-methylglucamine in 3% mannitol [1:1:8, v:w:v]) (Moss et al., 2015) or DTG (500 mg/kg or 750 mg/kg) by daily oral gavage beginning on GD 0.5 and continuing until the day of sacrifice (GD 9.5). All treatments were administered in a volume of 0.1 mL/10 g bodyweight (bwt).

2.3.2 Rationale for dose selection

According to the European Medicines Agency ICH S5 (R3). (2020) Guidelines on Reproductive Toxicology: Detection of Toxicity to Reproduction for Human Pharmaceuticals: “For small molecules, a systemic exposure representing a large multiple of the human AUC or Cmax at the maximum recommended human dose (MRHD) can be an appropriate endpoint for high dose selection. Doses providing an exposure in pregnant animals >25-fold the exposure at the MRHD are generally considered appropriate as the maximum dose for Developmental and Reproductive Toxicology studies and should be sufficient to detect the teratogenic hazard. Biological plausibility is assessed by comparison of pharmacologic mechanism of action with the known role of the target in development. This relationship is further strengthened by evidence that the finding is dose-related, whether characterized as increasing incidence or severity. In the absence of confounding maternal toxicity, the selection of a high dose for EFD studies that represents a >25-fold exposure ratio to human plasma exposure of total parent compound at the intended maximal therapeutic dose is therefore considered pragmatic and reasonably sufficient for detecting outcomes relevant for human risk assessment.” [ICH S5 (R3), 2020; Andrews et al., 2019] Based on the NOAEL (1000 mg/kg/d) and DTG dose range used in preclinical studies involving rabbits and rats (Stanislaus et al., 2020), and recommended appropriate high dose selection of >25-fold the MRHD for rodent EFD studies, we started with an oral test dose of DTG 750 mg/kg/d in the selected mouse strains. Blood samples were collected from pregnant and non-pregnant mice for pharmacokinetic (PK) determination of Cmax and AUC to confirm the DTG exposure ratio relative to human plasma.

2.4 Experimental diets

The SWV and LM/Bc breeding colonies have been maintained on Envigo Rodent Chow #8904 (a soy protein-based irradiated diet) for >20 years. C3H/HeJ and C57BL/6J mice (6–10 weeks old) were immediately placed on Envigo #8904 upon arrival at Creighton University and were maintained on this diet for a minimum of 1 month prior to analysis of basal plasma and urine cations. The National Research Council (NRC) estimate for the minimum Mg2+ requirement in adult mice is 0.5 ppm of diet (0.05%). Magnesium in standard rodent diets ranges between 2–3 g mg/kg; the Envigo #8904 soy diet contains .3% Mg2+ by weight (5 times the NRC requirement) and was therefore considered a ‘high’ Mg2+ diet. Sources of Mg2+ in the soy diet include magnesium oxide (∼20%) and Mg2+ found naturally in grain ingredients (∼80%); it was therefore not possible to remove Mg2+ to create a soy-based version that was Mg2+ deficient. To test the hypothesis that low maternal plasma Mg2+ prior to conception would increase susceptibility to DTG-induced NTDs, it was necessary to switch to casein-based purified ingredient diets with defined levels of Mg2+ added back. The following casein-based purified ingredient diets were selected as experimental diets: TD.120,574 high Mg2+ diet (.3% Mg2+ oxide added to match the .3% high Mg2+ soy-based diet); TD.98341 control Mg2+ diet with 0.05% Mg oxide added back to match the NRC requirement; and TD.93106 Mg2+-deficient diet (<.003%, no Mg2+ added back). The purified casein diets met or exceeded the NRC requirements for all other minerals and vitamins, including folic acid (Supplementary Table S1: Diet Comparison). Thus, the 4 experimental diets were as follows: 1) high Mg2+ (.3%) soy diet; 2) high Mg2+ (3%) casein diet; 3) control Mg2+ (.05%) casein diet; and 4) deficient Mg2+ (<.003%) casein diet. C57BL/6J mice placed on severely Mg2+-deficient diets (<.003% Mg2+) demonstrate a significant decrease in plasma Mg2+ within 10–14 days, although they continue to appear healthy (Bardgett et al., 2005). Our initial DTG teratology studies were performed in mice on the high Mg2+ soy diet. However, our objective in the second set of experiments was to reduce pre-conception plasma Mg2+ levels prior to DTG exposure. To accomplish this objective, weaned female mice were placed on either the high Mg2+ casein diet or one of the 2 casein-based experimental diets with reduced Mg2+ (control or deficient) for a minimum of 2 weeks. After this minimum period of acclimation to the experimental casein-based diets, blood and urine samples were collected for Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) determination of Mg2+ (and other cations).

2.5 Urine collection (metabolic cages)

Non-pregnant female mice of each strain were placed into metabolic cages in groups of 3 mice per cage (n = 3 cages of each strain/diet) and allowed to acclimate for 24 h before urine collection began. Following adaptation, 24-h pooled urine samples were collected from each cage for 3 consecutive days to determine strain and/or diet-induced differences in urine cations. The volume of urine collected for each 24-h period was recorded, and samples were frozen at −80 °C for ICP-MS analysis.

2.6 Blood collection

Baseline blood samples were collected via cheek bleed (submandibular vein) from all animals prior to timed matings, and again on GD 9.5. A Goldenrod sterile lancet (MEDIpoint, Inc., Mineola, NY) was used to lance the submandibular vein, and 3-4 drops (∼100 µL) of blood was collected into a Microvette CB 300 Lithium Heparin plasma separator tube (SARSTEDT AG and Co., Germany) and then centrifuged at 2000 g for 8 min. Plasma samples were frozen at −80 °C for LCMS analysis of DTG or ICP-MS determination of cations.

2.7 Embryo harvest and phenotyping

Pregnant dams were anesthetized with isoflurane and sacrificed by cervical dislocation on GD 9.5. The uterus was removed and examined under a dissecting microscope; individual implants were separated, assigned a number, and placed in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline. Embryos were examined and the phenotype reported as normal (GD 9.5, fully turned, Theiler stage 14, cranial neural tube closed), resorption, developmental delay (not fully turned, Theiler Stage 12–13, open neural folds), or NTD (GD 9.5, fully turned, exencephalic). Whole embryos were photographed under a Nikon SMZ 1500 stereomicroscope mounted with an AmScope™ 18MP USB3.0 digital camera. Placentas (decidua basalis) and embryos were fixed in 10% formalin or frozen at −80°C.

2.8 Liquid chromatography—Mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS): Determination of plasma DTG concentration

DTG detection and quantification was performed at Creighton University using a previously published method (Bennetto-Hood et al., 2014) with minor modifications. Briefly, a seven-point calibration curve ranging from 0.1 to 100 μg/mL was challenged with quality control vials at known concentrations of 5, 20, and 80 μg/mL. All controls and calibrators with known drug concentrations were added to DTG-free mouse plasma. To initiate protein precipitation, 120 µL of acetonitrile containing 10 ng/mL of d5- DTG internal standard (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) was added to 20 µL mouse plasma (calibrators, controls, unknown samples), and mixed for 2 min on an orbital shaker (1500 rpm), followed by centrifugation at 2,655 g for 5 min. Finally, 20 µL of supernatant was transferred into a vial containing 120 µL of 1 mg/mL EDTA (pH 8) with 0.1% formic acid. LC-MSMS separation was achieved using Agilent 1200 liquid chromatography devices and an AB Sciex 3200 Q-Trap mass spectrometer. The mobile phase consisted of an isocratic gradient of 0.1% formic acid in water:0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (60:40) with a flow rate of 0.475 mL/min across an XBridge C18 column (Waters, Milford, MA, United States). The mass spectrometer identified DTG (m/z = 420.2 (277.2) and d5-dolutegravir (m/z 425.2 (277.2) in MRM scan mode with ESI positive polarity. All solvents used were HPLC grade and above. Linear best fit curves of calibrators allowed for quantification of control and unknown sample concentrations.

2.8.1 Pharmacokinetics

Blood was collected from separate groups of n = 3 non-pregnant LM/Bc female mice/time point for each of 10 different time points (0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 16, 20, and 24 h) following oral gavage administration of a single dose of DTG (750 mg/kg). Plasma DTG levels were determined by LC-MS/MS and PK Solver v2.0 (Zhang et al., 2010) was used to determine Cmax, Tmax, t½, and AUC. To evaluate potential differences in DTG pharmacokinetics (PK) between non-pregnant females (single oral dose DTG750) and pregnant females (10 doses DTG750, daily oral gavage from E0.5–E9.5), pregnant mice were given the last DTG dose on E9.5 and blood samples were collected at 12 different time points over a period of 24 h after that dose.

2.9 ICP-MS determination of plasma and urine cations

ICP-MS analyses of plasma and urine Mg2+ (and 17 other cations) were performed by Dr. Javier Seravalli at the Spectroscopy and Biophysics Core Facility, Redox Biology Center, University of Nebraska-Lincoln. These analyses used an Agilent Technologies ICP-MS 7500cs and an ESI SC-4 high-throughput autosampler, and the method was optimized for the analysis of eighteen elements (including 24Mg and 44Ca). Each biological sample was run in triplicate.

2.10 Statistical analysis

Strains and treatments were compared by 2-way ANOVA followed by post hoc analyses. Pairwise comparisons of the proportion of affected embryos in each litter between strains and treatments were evaluated by the Fisher least significant difference method. Index value pairwise comparisons were evaluated using the Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric test in Sigma XL (v9.0). Comparisons of cation levels in urine and plasma between strains and between diets as well as the effect of DTG on the incidence of NTDs in LM/Bc dams was performed by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test using GraphPad Prism version 9.5.0 for Windows. The level of significance p < 0.05 was used for all analyses. DTG pharmacokinetics were evaluated by noncompartmental analysis (NCA) using PKsolver (Zhang et al., 2010).

2.11 Whole-exome sequencing, alignment, detection of genetic variants

DNA from tail snips of LM/Bc and SWV mice were extracted using the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI). Exonic regions were enriched for one mouse of each strain using the SureSelect XT Mouse All Exon kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. This kit targets 221,784 exons within 24,306 genes, with a total capture size of 49.6 MB. Prepared libraries were sequenced 2x100nt on an Illumina HiSeq at the David H. Murdock Research Institute (Duke University) in 2012. The resulting data was aligned against the NCBI37 mouse reference genome, the alignments cleaned, and the variants called, except without use of the contamination threshold parameter or allele phasing. To reduce artifacts and false positives, variants were required to have a read depth of at least 4, fewer than 10% of reads with mapping quality of 0, and a quality-by-depth of at least 7.

2.11.1 Identification of genetic variants involved in Mg2+ homeostasis

Variants were lifted over to the GRCm39 (C57BL/6J) reference genome using the Ensembl Assembly Converter tool and annotated using the Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) tool. To identify potential variants that might explain differences in basal plasma and urine Mg2+ and susceptibility to DTG–NTDs between the different mouse strains, moderate (missense) and high (nonsense, splicing, frameshifting, and start-loss) risk variants in known magnesium pathway homeostasis genes were examined. The set of magnesium homeostasis genes was assembled using a union of OMIM and Clinvar genes. A list of the 35 candidate genes analyzed is given in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Candidate genes involved in magnesium homeostasis.

| Apc | Clcnkb | Egf | Hip14l | Mmgt2 | Nipal1 | Slc41a1 |

| Atp13a2 | Cldn16 | Egfr | Hnf1b | Mrs2 | Nipal4 | Slc41a2 |

| Atp13a4 | Cldn19 | Fam111a | Kcna1 | Mt-t1 | Pcbd1 | Trpm6 |

| Bsnd | Cnmm2 | Fyxd2 | Kcnj10 | Nipa1 | Sars2 | Trmp7 |

| Casr | Cnnm2 | Hip14 | Mmgt1 | Nipa2 | Slc12a3 | Xk |

2.11.2 Primer design, Sanger validation

Primers for Sanger validations were designed using Primer3web (v 4.1.0). DNA was extracted from tail snips using the PureLink™ Genomic DNA Mini Kit (Invitrogen). Samples were amplified using the Phusion Flash High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher) and 1 µM of primers. PCR was denatured at 98 °C for 10 s, followed by 35 cycles of 98 °C for 1 s, 48 °C for 5 s, and 72 °C for 15 s, and a final extension of 72 °C for 1 min. Products were cleaned using AMPureXP beads (Beckman Coulter) at 1.8X, eluted in water, and quantified using a Qubit BR dsDNA kit (Invitrogen). Sanger sequencing was performed at Genewiz/Azenta Life Sciences and consensus calling was manually checked from chromatograph traces using GeneSnap Viewer v5.3.2.

3 Results

3.1 Strain comparison: Basal plasma and urine cations on the high Mg2+ soy natural ingredient diet

3.1.1 Strain differences in basal plasma cations

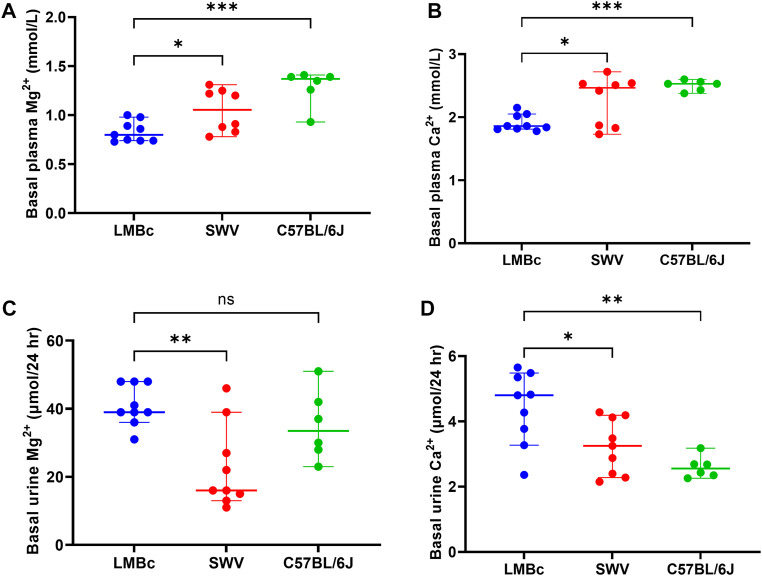

After a minimum of 4 weeks on the high Mg2+ soy diet, average basal plasma Mg2+ levels were determined for each of the 4 mouse strains (n = 9 non-pregnant females/strain). The results are shown in Figure 1A. As predicted, basal plasma Mg2+ values (average ± SEM) were lowest for C3H/HeJ (0.78 ± 0.03, not shown) and LM/Bc (0.83 ± 0.03), and not significantly different from one another. Moreover, basal plasma Mg2+ for LM/Bc was significantly lower than SWV (1.05 ± 0.08) and C57BL6/J (1.29 ± 0.07). Based on these results, C3H/HeJ and LM/Bc were considered to have ‘low’, SWV ‘intermediate’, and C57BL6/J ‘high’ basal plasma Mg2+ levels.

FIGURE 1.

Strain comparison: Basal plasma and urine cations. The results of the strain comparison for (A) basal plasma Mg2+ and (B) basal plasma Ca2+ are shown (median mmol/L ± 95% CI). LM/Bc mice have inherently lower plasma Mg2+ and Ca2+ than either the SWV (*p < 0.05) or the C57BL/6J strain (***p < 0.001). The results of the strain comparison for (C) basal urinary excretion of Mg2+ and (D) basal urinary excretion of Ca2+ (D) are also shown (µmol/24 h ± 95% CI). Urinary excretion of Mg2+ in LM/Bc was significantly higher than SWV (**p < 0.01) but did not differ from C57BL/6J. However, urinary Ca2+ excretion in LM/Bc mice was significantly higher than in both SWV (*p < 0.05) and C57BL/6J (**p < 0.01) mice.

Similar results were obtained when comparing basal plasma Ca2+ across strains (Figure 1B). Plasma Ca2+ (average ± SEM) was not significantly different between C3H/HeJ (1.91 ± 0.09) and LM/Bc (1.91 ± 0.04). However, plasma Ca2+ was significantly lower in LM/Bc when compared to SWV (2.27 ± 0.14) with ‘intermediate’ and C57BL6/J (2.51 ± 0.03) with ‘high’ plasma Ca2+ levels.

3.1.2 Strain differences in basal urinary cations

After a minimum of 4 weeks on the high Mg2+ soy diet, basal urinary excretion of Mg2+ (Figure 1C) and Ca2+ (Figure 1D) were determined for the 4 mouse strains. Although both the C3H/HeJ and LM/Bc strains had low plasma Mg2+ on this diet, they differed in urinary Mg2+ excretion. The 24 h urinary Mg2+ output (µmol/24 h ± SEM) in LM/Bc mice (41.07 ± 2.03) was significantly higher compared to that in C3H/HeJ (28.08 ± 3.61, not shown) and SWV mice (22.82 ± 4.12). Meanwhile, in C57BL/6J mice, urinary Mg2+ was high (35.06 ± 4.21), and not significantly different from LM/Bc. However, unlike LM/Bc mice, C57BL/6J mice were able to maintain high basal plasma Mg2+ levels despite elevated urinary Mg2+ excretion (Figure 1A).

Urinary Ca2+ excretion (µmol/24 h ± SEM) was also significantly higher in LM/Bc (4.42 ± 0.37) compared to SWV (3.23 ± 0.28) and C57BL/6J (1.73 ± 0.44) (Figure 1D) but did not differ from the C3H/HeJ strain (3.92 ± 0.25, not shown). LM/Bc and C3H/HeJ mice both have low basal plasma Mg2+ and Ca2+ levels; the major difference is that only the LM/Bc strain exhibits hypermagnesuria (Figure 1C). Continued high urinary Mg2+ output in the LM/Bc strain despite low basal plasma Mg2+ levels on the high Mg2+ soy diet suggests renal Mg2+ wasting and an imbalance in Mg2+ homeostasis.

3.2 Strain comparison: DTG-NTD susceptibility on high Mg2+ soy diet

Based on basal plasma Mg2+ levels, the LM/Bc strain was predicted to be susceptible to DTG-NTDs, whereas the SWV and C57BL/6J strains were predicted to be more resistant. The strain comparison with respect to NTD susceptibility on the high Mg2+ soy diet and DTG750 treatment is shown in Table 2. The dam is considered the experimental unit; comparisons are between litter means. The mean litter rate was calculated by averaging the % of embryos in each litter that had an NTD. Any litter with one or more exencephalic embryo(s) was considered ‘affected’. No NTDs were observed in any vehicle-treated litter, regardless of strain. No NTDs were observed in C57BL/6J litters (n = 10) treated with DTG750. However, 3 pups with exencephaly were observed in 1/13 litters (7.6%) from DTG750-treated SWV dams, and a total of 28 pups with exencephaly (out of 166 total implants) were observed in 12/19 (63.2%) litters from DTG750-treated LM/Bc dams (1–6 NTDs/affected litter). The number of affected litters following exposure to DTG750 was significantly higher in the LM/Bc strain compared to either the SWV or C57BL6/J strain (p < .01). Unexpectedly, there were no significant differences between strains in the number of resorptions or developmental delays following exposure to DTG750.

TABLE 2.

Strain comparison: NTDs ON HIGH Mg2+ SOY DIET x DTG750. Pregnant dams from three different mouse strains with inherently different basal plasma Mg2+ levels were maintained on a high Mg2+ (0.3%) soy diet and treated with oral vehicle or DTG (750 mg/kg/d) from the day of conception (GD 0.5) until GD 9.5. The strains were compared for susceptibility to DTG-NTDs. The dam is considered the experimental unit and comparisons are between litter means. The mean litter rate was calculated by averaging the % of embryos in each litter that had an NTD. A litter is considered affected if at least 1 embryo presented with exencephaly (NTD). Statistical analysis was done by 2-way ANOVA and post hoc analysis (Fisher least significant difference method) or by the Kruskal–Wallis test for nonparametric analyses of index values, both using the software Sigma XL (https://www.sigmaxl.com/). Within each variable, the highlighted numbers and asterisks indicate statistical differences in pairwise comparisons (α > 0.99).

| LMBc | SWV | C57BL/6J | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | VEH | DTG750 | VEH | DTG750 | VEH | DTG750 |

| Implants per litter | 8.40 (1.65) | 8.74 (2.47) | 14.17 (1.03)** | 13.15 (2.12)** | 8.82 (1.47) | 9.80 (1.48) |

| Resorptions per litter | 0.90 (0.88) | 0.95 (1.27) | 1.25 (1.29) | 0.62 (0.87) | 0.82 (1.08) | 0.50 (0.85) |

| Total viable embryos | 7.50 (1.08) | 7.79 (2.76) | 12.92 (1.08)** | 12.54 (2.37)** | 8.00 (2.19) | 9.30 (1.77) |

| Dev. delayed | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.58 (0.96) | 0.25 (0.45) | 0.31 (0.48) | 0.09 (0.30) | 0.20 (0.42) |

| NTDs | 0.00 (0.00) | 1.47 (1.74)** | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.23 (0.83) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) |

| Index Values Average % (SD) | ||||||

| Resorptions/implants | 9.6% (8.87) | 11.5% (15.75) | 8.5% (8.50) | 5.0% (7.62) | 10.8% (14.81) | 5.3% (9.30) |

| Dev delay/implants | 0.0% (0.00) | 8.1% (17.76) | 1.7% (3.16) | 2.0% (3.19) | 1.0% (3.35) | 1.9% (4.15) |

| NTDs/implants | 0.0% (0.00) | 17.7% (20.63)** | 0.0% (0.00) | 1.6% (5.94) | 0.0% (0.00) | 0.0% (0.00) |

| NTDs/embryos | 0.0% (0.00) | 20.9% (23.65)** | 0.0% (0.00) | 1.8% (6.40) | 0.0% (0.00) | 0.0% (0.00) |

| Affected litters % | 0.0% | 63.2%** | 0.0% | 7.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Number of litters | 10 | 19 | 12 | 13 | 11 | 10 |

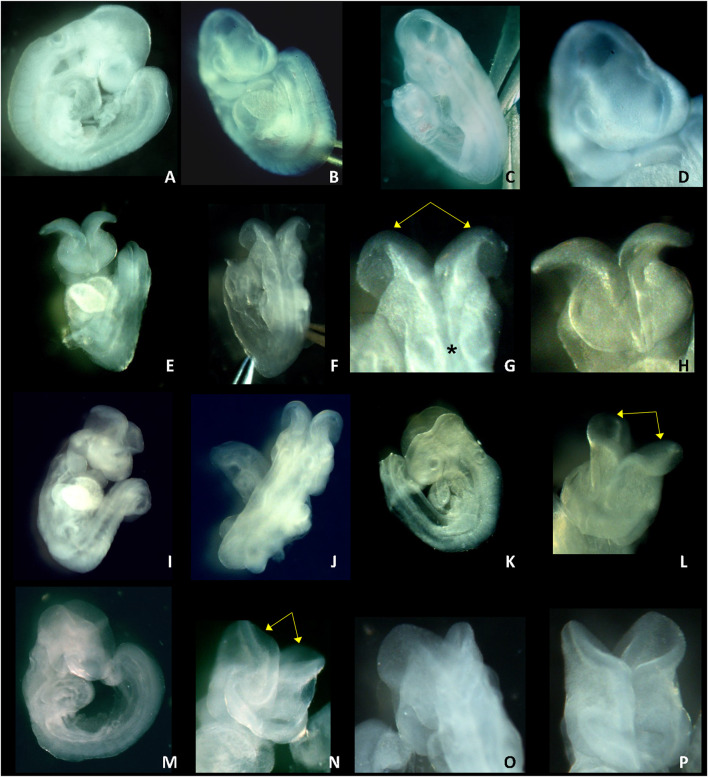

Photos of GD 9.5 LM/Bc embryos harvested from dams on the high Mg2+ soy diet treated with vehicle or DTG750 are shown in Figure 2. Vehicle-treated GD 9.5 embryos are fully turned, and the cranial neural tube is closed (Figures 2A–D). DTG750-treated GD 9.5 embryos are fully turned but have open cranial neural tubes (exencephaly) in which the neural folds bend outward (bilaterally) at the dorsolateral hinge points. Divergence of the neural folds begins at the rhombic lip (the boundary between the cervical spine and the hindbrain) and extends rostrally, including the boundary of the midbrain with the caudal forebrain, demonstrating failure of closure site 2 (Figure 2E–P).

FIGURE 2.

NTDs IN GD 9.5 LM/Bc EMBRYOS ON HIGH Mg2+ SOY DIET x DTG750. Photos of GD 9.5 embryos from LM/Bc dams on high Mg2+ soy diet treated with vehicle (first row) or from dams treated with DTG750 (second, third and fourth rows) are shown. First row: normal GD 9.5 embryos with closed neural tube from vehicle treated litter (A) side view of normal, fully turned GD 9.5 embryo; (B) front (rostral) view, normal; (C) back (caudal) view, normal; and (D) close-up of front view. The remaining three panels (rows) show representative exencephalic GD 9.5 embryos from litters treated with DTG750. Second row: Photos (E—G) are of the same GD 9.5 exencephalic embryo: (E) front view showing open (everted) cranial neural folds; (F) caudal view of the same embryo; (G) close-up of caudal view showing that from the rhombic lip (boundary between spinal neural tube and hindbrain, denoted by asterisk*) forward, the neural folds are open and diverge away from one another (yellow arrows); (H) close-up of rostral view. Third row: (I, J) rostral and caudal view of a GD 9.5 embryo with open cranial neural folds (K) side view and (L) close-up rostral view of another GD 9.5 embryo with open cranial neural folds (yellow arrows) that diverge and bend outward bilaterally at the dorsolateral hinge points. Bottom row: (M–P) different views of an exencephalic GD 9.5 embryo (M) side view; (N) front (rostral) view of open cranial neural folds (yellow arrows); (O) back (caudal) view; (P) close-up front view.

No NTDs were observed in LM/Bc mice on the high Mg2+ soy diet when pregnant dams were treated with DTG 500 mg/kg/d (DTG500). Of the n = 7 litters examined at this lower dose, all 62 viable embryos were developmentally normal, fully turned GD 9.5 embryos with a closed cranial neural tube (71 implants, 9 resorptions, no developmental delays, 62 normal). Additional DTG doses on this diet will need to be tested to definitively determine the NOAEL.

3.3 DTG pharmacokinetics

The results of the LC-MS/MS pharmacokinetic analyses for plasma DTG in non-pregnant and pregnant LM/Bc mice on the high Mg2+ soy diet are shown in Table 3. The Cmax and AUC are compared to values reported from human studies in which non-pregnant participants received a single dose of DTG 50 mg (Min et al., 2010). The most prescribed dose for DTG is 50 mg/d, but the maximum human recommended dose (MHRD) is 50 mg twice a day (100 mg/d). Values for a single dose of DTG 100 mg (Min et al., 2010) and DTG 100 mg × 7d (Wang et al., 2019) are shown for comparison. PK values shown for pregnant women were from the second trimester (50 mg/d) (Mulligan et al., 2018). Using both the Cmax and AUC for comparison, a single dose of DTG750 in non-pregnant mice is less than the target goal of >25x the MHRD. In pregnant mice, multiple doses of DTG750 give a Cmax of 35.3x human values for the 50 mg/d dose in pregnant women, but an AUC of only 17.8x. Although Tmax is the same in pregnant mice and women (2 h) following oral dosing, DTG was metabolized more rapidly in mice; the t½ in mice is considerably shorter (4.4 h compared to 11 h in women) resulting in a reduced multiplication factor for AUC.

TABLE 3.

Pharmacokinetics: Plasma DTG in LM/Bc MICE on HIGH Mg2+ SOY DIET. Published pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters (Cmax, AUC, t½, and Tmax) for single or multiple doses of DTG in non-pregnant and pregnant humans are compared to the PK parameters in LM/Bc mice receiving a single oral dose (non-pregnant) or multiple doses (pregnant) of DTG. The maximum human recommended dose (MHRD) for DTG is 50 mg twice a day (100 mg/d). Female LM/Bc mice were maintained on high Mg2+ soy diet. Non-pregnant females were administered a single oral dose of DTG (750 mg/kg/d) and pregnant females were administered the same oral dose (DTG750) daily (from GD 0.5 to GD9.5). For developmental toxicology studies, the goal is to provide a systemic exposure >25x the MHRD (Cmax or AUC) [ICH S5 (R3)]. In pregnant LM/Bc mice the Cmax approximates 35x the Cmax in pregnant women (second trimester) taking oral DTG (50 mg/d); however, in the same comparison, the AUC in pregnant mice approximates only 18x the AUC in pregnant women because the DTG t½ is much shorter in mice.

| Mouse (DTG750 mg/kg, oral gavage) | Human | Mouse (multiplication factor) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PARAMETER | UNIT | VALUE | ||

| Cmax | ||||

| Non-pregnant (single dose DTG750) | µg/mL | 132.98 | 4.6 (50 mg single dose) 1 | 28.9 x |

| 6.7 (100 mg × 7d) 2 | 19.8 x | |||

| 8.1 (100 mg single dose) 1 | 16.4 x | |||

| Pregnant (10 daily doses DTG750) GD 0.5—GD 9.5 | µg/mL | 127.89 | 3.62 (2.57–4.63) | 35.3 x |

| (2nd trimester, 50 mg/d) 3 | ||||

| AUC 0-24 | ||||

| Non-pregnant (single dose DTG750) | µg*h/mL | 1299.36 | 70.8 (50 mg single dose) 1 | 18.4 x |

| 92.3 (100 mg × 7d) 2 | 14.1 x | |||

| 131 (100 mg single dose) 1 | 9.9 x | |||

| Pregnant (10 daily doses DTG750) GD 0.5—GD 9.5 | µg*h/mL | 846.55 | 47.6 (33.4–63.7) (2nd trimester, 50 mg/d) 3 | 17.8 x |

| t½ | ||||

| Non-pregnant (single dose DTG750) | h | 6.30 h | 13–14 h (50 mg single dose) 1 | |

| Pregnant (10 daily doses DTG750) | h | 4.40 h | 11 h (2nd trimester, 50 mg/d) 3 | |

| Tmax | ||||

| Non-pregnant (single dose DTG750) | h | 2.00 h | 1.25 h (50 mg single dose) 1 | |

| Pregnant (10 daily doses DTG750) | h | 2.00 h | 2 h (2nd trimester, 50 mg/d) 3 | |

3.4 Plasma and urine Mg2+ on purified-ingredient casein diets with defined Mg2+ concentrations

To determine the role of reduced or deficient maternal dietary Mg2+ intake on DTG-NTD susceptibility, newly weaned female LM/Bc mice (from lactating dams maintained on the high Mg2+ soy diet) were placed on casein-based purified ingredient experimental diets with defined Mg2+ concentrations as previously described.

3.4.1 Impact of reduced dietary Mg2+ intake on plasma and urine Mg2+ in LM/Bc mice

Non-pregnant LM/Bc mice were placed on the 3 experimental casein-based diets to evaluate the impact of reduced dietary Mg2+ intake on plasma and urine Mg2+ levels prior to timed matings.

The first group of female LM/Bc mice (n = 5) placed on the deficient Mg2+ casein diet all died unexpectedly within 5–7 days. They appeared active and healthy prior to being found dead in their cage. Necropsy did not reveal any remarkable findings. Low blood levels of Mg2+ are known to cause cardiac arrhythmias and seizures. Dietary Mg2+ insufficiency coupled with renal Mg2+ wasting in the LM/Bc mice likely resulted in a severe drop in plasma Mg2+ and death due to a sudden cardiac event. Due to this unforeseen outcome, it was not possible to move forward with experiments examining the combined effect of DTG and Mg2+-deficient diet in LM/Bc mice. Instead, LM/Bc females were placed only on the high or control Mg2+ casein diets.

Plasma and urine Mg2+ concentrations were measured in female LM/Bc mice (n = 9) on the high Mg2+ soy diet at the time of weaning and then again in the same group of mice after 2 weeks (15 days) on the high Mg2+ casein diet. Another group of LM/Bc mice (n = 6) was placed on the control Mg2+ casein diet at the time of weaning and had plasma and urine Mg2+ measured after 2 weeks (15 days) and again after 8 weeks (60 days). LM/Bc mice maintained on the control Mg2+ casein diet for 8 weeks continued to appear healthy. It was determined that additional LM/Bc mice could safely be placed on this diet for up to 8 weeks and used for timed matings.

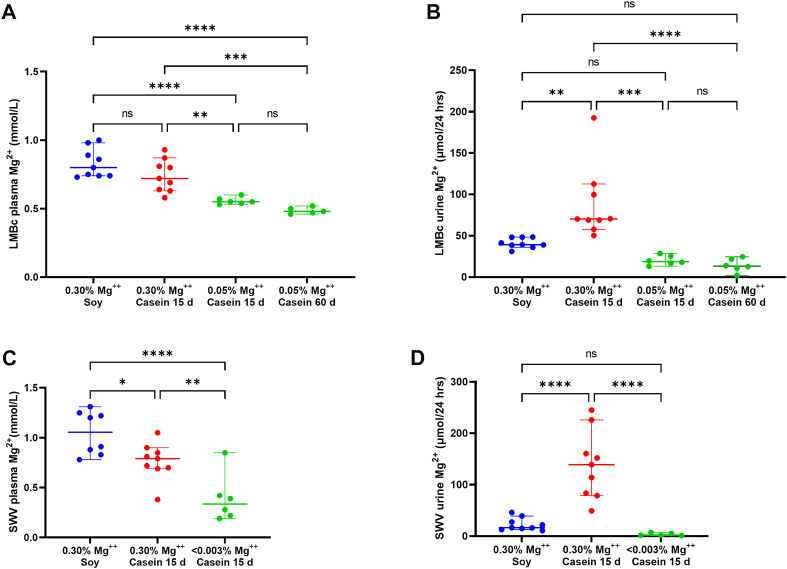

3.4.1.1 LM/Bc Plasma Mg2+

The results for diet effect on plasma Mg2+ levels are shown in Figure 3A. In the LM/Bc strain, there was a slight but insignificant decrease in plasma Mg2+ (mmol/L ± SEM) when mice on the high Mg2+ soy diet (0.83 ± .04) were placed on the high Mg2+ casein diet for 15 days (0.74 ± .04). LM/Bc mice on both high Mg2+ diets maintained similar basal plasma Mg2+ values. However, as predicted, when mice were placed on the control Mg2+ casein diet, average plasma Mg2+ levels dropped significantly after 15 days (0.56 ± .01) and slightly further after 60 days (0.49 ± .01), although the additional decrease was not itself statistically significant.

FIGURE 3.

Impact of reduced dietary Mg2+ on plasma and urine Mg2+ in LM/Bc and SWV mice. The impact of reduced dietary intake of Mg2+ on plasma Mg2+ levels (median mmol/L ± 95% CI) in LM/Bc mice are shown in (A). Plasma samples were evaluated in weaned females on high Mg2+ (0.3%) soy diet (blue dots) and 15 days after they were placed on the high Mg2+ (0.3%) casein diet (red dots). There was no significant change in plasma Mg2+ between the 2 high Mg2+ (soy and casein) diets. However, after LM/Bc mice were placed on the control Mg2+ (0.05%) casein diet for 15 days or 60 days (green dots), plasma Mg2+ dropped significantly when compared to either of the high Mg2+ diets. For all plots in Figure 3 (*p < .0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001). The impact of reduced dietary intake on urinary excretion of Mg2+ (µmol/24 h ± 95% CI) for the corresponding diets and time points in LM/Bc mice is shown in (B). After 15 days on the high Mg2+ casein diet (red dots), urinary Mg2+ excretion was significantly higher than on either the high Mg2+ soy diet (blue dots) or the control Mg2+ casein diet (green dots). After 15 days or 60 days on the control Mg2+ (0.05%) casein diet, urinary Mg2+ output was similar and not significantly different from the high Mg2+ soy diet. The impact of severely reduced dietary intake of Mg2+ on plasma Mg2+ levels (median mmol/L ± 95% CI) in SWV mice is shown in (C). Plasma samples were evaluated in weaned females on high Mg2+ (0.3%) soy diet (blue dots) and again 15 days after they were placed on the high Mg2+ (0.3%) casein diet (red dots); somewhat unexpectedly, plasma Mg2+ levels decreased on the high Mg2+ (0.3%) casein diet (p < .05). After 15 days on Mg2+ deficient (<0.003%) diet, plasma Mg2+ levels dropped significantly (purple dots) relative to either of the high Mg2+ diets. The impact of reduced dietary intake on urinary excretion of Mg2+ (µmol/24 h ± 95% CI) for the corresponding diets and time points in SWV mice is shown in (D). Like the trend observed in LM/Bc mice, urinary Mg2+ excretion in SWV mice increased significantly after 15 days on the high Mg2+.

3.4.1.2 LM/Bc urine Mg2+

The results for urinary Mg2+ excretion on the experimental casein diets at time points corresponding to plasma Mg2+ quantifications are shown in Figure 3B. After 15 days on the high Mg2+ casein diet, urinary Mg2+ excretion (µmol/24 h ± SEM) in LM/Bc mice was highly variable, and on average, significantly higher (87.90 ± 15.50) than on the high Mg2+ soy diet (41.07 ± 2.16). The .3% Mg oxide added to the purified casein diet is predicted to be more bioavailable and more readily absorbed from the gut than the .3% Mg in the soy natural ingredient diet due to chelation of Mg2+ by phytate in plant sources (Gibson et al., 2018; Marolt et al., 2020). Monogastric animals do not have phytases in their digestive tract to break down phytic acid and release bound Mg2+ for absorption, so bio-accessibility in the soy diet may be <.3%. This could explain the higher urinary Mg2+ output for mice on the high Mg2+ casein diet vs the high Mg2+ soy diet; despite that disparity in urine output between the 2 high Mg2+ diets, basal plasma Mg2+ levels remained comparable. However, when mice were placed on the control Mg2+ casein diet, urine Mg2+ output declined significantly after 15 days (20.19 ± 2.56) and 60 days (14.26 ± 3.62).

3.4.2 Impact of reduced dietary Mg2+ intake on plasma and urine Mg2+ in SWV mice

To determine the role of deficient maternal dietary Mg2+ intake on DTG-NTD susceptibility in the SWV strain, newly weaned female SWV mice (from lactating dams maintained on the natural ingredient high Mg2+ soy diet) were placed on the Mg2+-deficient casein diet. Blood and urine samples were collected prior to the start of the experimental diet and again after 2 weeks (15 days) on the diet for ICP-MS determination of cations.

3.4.2.1 SWV plasma Mg2+

The results for diet effect (food matrix and Mg2+ concentration) on SWV plasma Mg2+ levels are shown in Figure 3C. Compared to plasma Mg2+ levels (mmol/L ± SEM) in SWV mice on the high Mg2+ soy diet (1.05 ± 0.08), average plasma Mg2+ decreased significantly after 15 days on the high Mg2+ casein diet (0.77 ± 0.07), although the reason(s) for this are not clear and may involve compensatory mechanisms such as release of parathyroid hormone that shift the homeostatic ‘set point’ in response to excess dietary Mg2+.

Mg 2+ -Deficient Diet: Plasma Mg2+ declined drastically in SWV after 15 days on the Mg2+-deficient casein diet (0.39 ± 0.11) to levels comparable with those observed in LM/Bc mice maintained on control Mg2+ casein diet for 60 days (0.49 ± .01).

3.4.2.2 SWV urine Mg2+

The impact of changing from high Mg2+ soy to high or deficient Mg2+ casein diets on urinary Mg2+ excretion in SWV mice is shown in Figure 3D. After 15 days on the high Mg2+ casein diet, urinary Mg2+ excretion (µmol/24 h ± SEM) in SWV mice was highly variable, and significantly higher (138.52 ± 23.30) than on the high Mg2+ soy diet (22.82 ± 4.37), the same trend that was observed for the LM/Bc strain. Increased Mg2+ bio-accessibility and elevated urinary Mg2+ output after 15 days on the high Mg2+ casein diet might explain the corresponding decline in plasma Mg2+ in SWV mice.

Mg 2+ -Deficient Diet: After 15 days on the Mg2+-deficient casein diet, urinary Mg2+ excretion decreased significantly (3.38 ± 1.25) relative to the high Mg2+ casein diet, indicative of renal conservation and reabsorption of Mg2+ in the SWV strain to compensate for the severe restriction in dietary Mg2+ intake.

3.5 Impact of reduced maternal dietary Mg2+ intake on susceptibility to DTG-NTDs

3.5.1 LM/Bc: High Mg2+ casein diet x DTG exposure

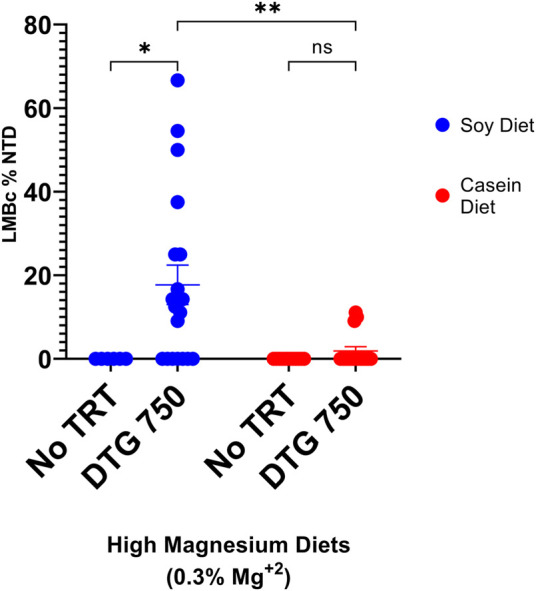

No NTDs were observed in LM/Bc mice (n = 12 litters, 89 implants) on the high Mg2+ casein diet only. However, in LM/Bc dams on the high Mg2+ casein diet who were treated with DTG750 90 implants total), 3/16 litters (19% NTD-affected litters; mean rate 2% NTDs/litter) each had n = 1 exencephalic embryo. This was significantly fewer NTD-affected litters compared to LM/Bc dams treated with DTG750 that were maintained on the high Mg2+ soy diet (63% NTD-affected litters; mean rate 18% NTDs/litter) (Figure 4). The higher incidence of DTG-NTD affected litters and mean % affected embryos/litter on the high Mg2+ soy diet is likely due to phytate chelation of Mg2+ in the plant-based diet and therefore less bio-accessibility of Mg2+ in the soy-vs. the casein-based diet.

FIGURE 4.

NTDs IN LM/Bc MICE ON HIGH Mg2+ DIETS (SOY vs CASEIN) x DTG750. LM/Bc mice were placed on either soy (blue dots) or casein (red dots) high Mg2+ (0.3%) diet for a minimum of 4 weeks prior to timed matings. Susceptibility to NTDs following administration of DTG (750 mg/kg/d oral gavage from GD 0.5—GD 9.5) was compared within each diet to a diet only control group (no treatment). Comparisons were also made between the two high Mg2+ (soy vs casein) diets in dams treated with DTG750. [An additional n = 6 dam on each diet received vehicle to confirm previous results that vehicle treatment alone did not cause NTDs; no NTDs were found in any of these litters (data not shown on graph)]. The dam was considered the experimental unit and comparisons shown are between litter means (average % of embryos in each litter that had an NTD). A litter was considered affected if at least 1 embryo presented with exencephaly (NTD). The % DTG-NTD-affected litters (63% soy vs 19% casein) and mean % affected embryos/litter (shown on graph) were both higher on the high Mg2+ soy diet compared to the high Mg2+ casein diet. (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01)

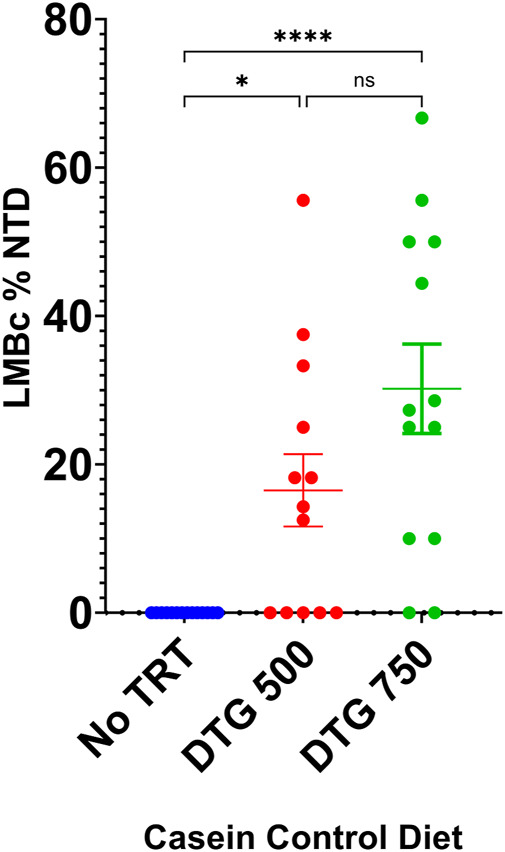

3.5.2 LM/Bc: control Mg2+ casein diet x DTG exposure

LM/Bc mice placed on the control Mg2+ casein diet for a minimum of 4 weeks continued to appear healthy and were placed into timed matings. Plugged females were randomly placed into one of 4 experimental groups: 1) diet-only control (no treatment); 2) vehicle; 3) DTG500; or 4) DTG750. No NTDs were observed in litters from LM/Bc mice on the control Mg2+ casein diet only (n = 14) or in litters from dams on the control Mg2+ casein diet who were treated with vehicle (n = 6). However, exencephalic embryos were observed when LM/Bc dams were administered either DTG750 (n = 13 litters) or DTG500 (n = 13 litters). In DTG750-treated dams, 11/13 litters (85%) had 1 or more exencephalic embryos (total of 33 NTDs/105 implants), ranging from 1 to 6 per litter. In DTG500-treated dams, 8/13 litters (62%) had 1 or more exencephalic embryos (total of 19 NTDs/116 implants), ranging from 1 to 5/litter. These results are depicted graphically in Figure 5. Fewer litters were affected with NTDs when exposed to DTG500 compared to DTG750; however, because of the within-litter variability in number of NTDs, analysis of litter means did not detect a statistically significant difference between dosages. Both DTG dosages were statistically significant compared to the diet-only control. Determination of the NOAEL and dose-response relationship will require testing lower doses of DTG in LM/Bc mice on the control Mg2+ casein diet. The present results demonstrate that LM/Bc mice are susceptible to NTDs at a lower DTG dose when dietary Mg2+ intake is reduced and hence maternal plasma Mg2+ levels are lower at the time of conception and start of DTG treatment.

FIGURE 5.

DTG-NTD dose-response in LM/Bc mice on casein control Mg2+ diet. LM/Bc mice were placed on the control Mg2+ (0.05%) casein diet for a minimum of 4 weeks prior to timed matings. Pregnant mice on diet only control (no treatment) were compared to mice treated with either DTG500 or DTG750 (oral gavage from GD 0.5—GD 9.5) and litters examined for NTDs. [No NTDs were observed in litters from an additional n = 6 dam on control Mg2+ diet treated with vehicle (data not shown)]. Comparisons shown are between litter means (average % of embryos in each litter that had an NTD). No NTDs were observed in diet only control litters (blue dots). The % DTG-NTD-affected litters (62% for DTG500 and 85% for DTG750) and mean % affected embryos/litter (shown on graph) were both significantly higher than the diet only control group, but DTG500 (red dots) and DTG750 litter means (green dots) were not significantly different from each other. (*p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001).

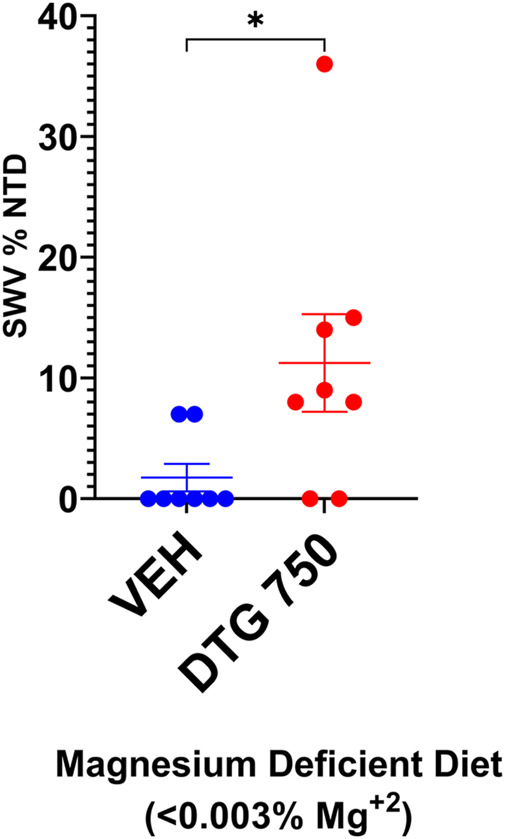

3.5.3 SWV: Deficient Mg2+ casein diet x DTG exposure

After a minimum of 4 weeks on the Mg2+-deficient casein diet, SWV females appeared in good health and were placed in timed matings. Plugged females received either no treatment (diet-only control) or the Mg2+-deficient casein diet + DTG750 to test whether severely reduced dietary intake of Mg2+ would increase susceptibility to DTG-NTDs (n = 8 females/treatment group). The results are shown in Figure 6. NTDs were observed in 2/8 (25%) litters (n = 1 exencephalic pup in each litter) among mice on the Mg2+-deficient casein diet only, demonstrating that maternal dietary Mg2+ deficiency alone compromises neural tube closure in SWV mice. In SWV dams on the Mg2+-deficient casein diet + DTG750, NTDs were observed in 6/8 (75%) litters (total of 11 NTDs, ranging from 1-4 per affected litter). The results demonstrate a combined diet x drug effect and increased susceptibility to DTG- NTDs (in an otherwise relatively resistant strain) when dietary Mg2+ intake is reduced and hence maternal plasma Mg2+ levels are lower at the time of conception and start of DTG treatment.

FIGURE 6.

NTDs IN SWV MICE ON Mg2+ DEFICIENT DIET x DTG750. SWV mice were placed on Mg2+ deficient (<0.003%) casein diet for a minimum of 4 weeks prior to timed matings. Pregnant mice received either no treatment (diet-only control) or DTG750 (oral gavage from GD 0.5—GD 9.5). NTDs were observed in 25% of diet only control litters and 75% of litters treated with DTG750. The mean % affected embryos/litter (shown on graph) was significantly higher in the DTG750-treated group (red dots) than in the diet only control group (red dots). (p < .05).

3.6 Analysis of variants in magnesium homeostasis pathway genes

A diet x drug effect and increased susceptibility to DTG-NTDs was observed in both LM/Bc and SWV mice when maternal plasma Mg2+ levels were lower prior to the onset of drug treatment due to reduced dietary Mg2+ intake. However, the LM/Bc strain was more susceptible to DTG-NTDs than the SWV strain when dietary Mg2+ levels were sufficient, suggesting an underlying genetic predisposition. To identify genetic variants that might contribute to perturbations in Mg2+ homeostasis and hence the increased susceptibility of the LM/Bc strain to DTG-NTDs, we reanalyzed a whole-exome sequencing data set previously generated from these 2 strains.

The summary statistics for the analyses of all variants in the SWV and LM/Bc mouse strains compared to a C57BL/6J reference are shown in Supplementary Table S2. All SNVs and insertions/deletions (indels) found in the DTG-NTD susceptible LM/Bc strain are shown in Supplementary Table S3; Supplementary Table S4. No variants in Ugt1a1, Ugt1a3, Ugt1a9, or Cyp3a4 (genes involved in DTG metabolism) were found that were unique to LM/Bc (validated by Transnetyx, Inc, Cordova, TN). One high-risk variant in a known magnesium homeostasis gene was identified in LM/Bc but not in SWV–a heterozygous frameshifting variant in Hnf1b (Supplementary Table S4). However, Sanger validation (Supplementary Figure S1) showed that this was likely a false positive call in a difficult-to-sequence region of the genome.

We also looked for variants unique to LM/Bc with a predicted deleterious effect (SIFT) that are intolerant to mutation in humans (pLI >0.9 applied to putative LoF variants or a missense z > 3 applied to missense variants; gnomAD, Broad Institute). This list included 17 SNVs in 14 genes (Nck2, Eef2, Gck, Smurf2, Scn8a, Vps52, Psmc3, Camta1, Rbpj, Ran, Cdk8, Kcnn1, Ano8, and Dnmt1) shown in Supplementary Table S3. Six of these variants have risen to a homozygous state in the LM/Bc strain.

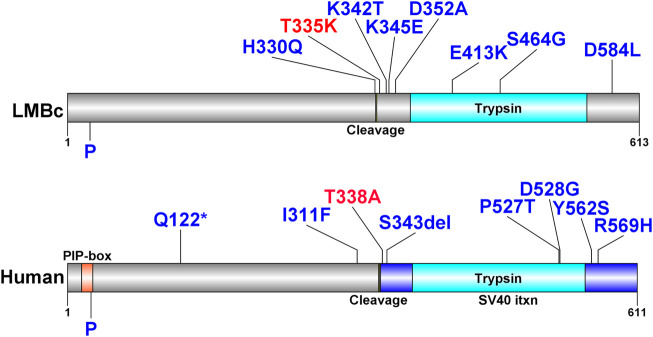

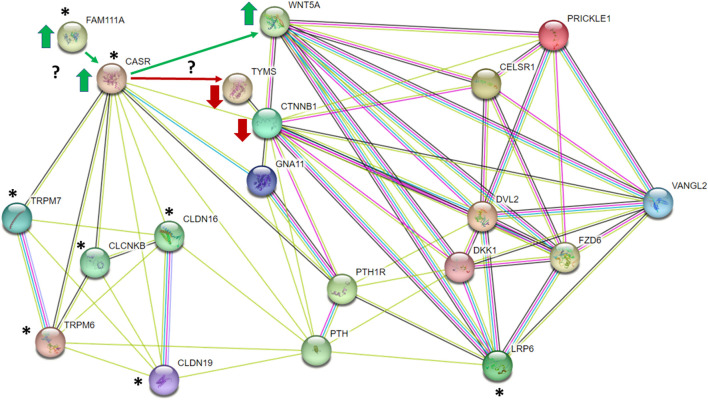

Identification of Unique Fam111a Variants in LM/Bc: For missense variants, we further filtered for those with a predicted deleterious effect as determined by SIFT, which identified a collection of 9 Sanger-verified SNVs in the gene Fam111a. LM/Bc mice are homozygous for all 9 of the predicted deleterious variants. Thirty-seven additional benign SNVs were also found in this gene in the LM/Bc strain but not in SWV or in the C57BL/6J reference genome. Three of the same benign SNVs were found in the background C3H/HeJ strain, but none were predicted to be protein disruptive. All benign variants falling within the Sanger amplicon containing the 9 deleterious variants were also validated. The results are shown in Supplementary Figure S2. SNVs are shown in bold red font. In PCR reactions, the Fam111a_F primer was used to amplify all samples, with Fam111a_R for SWV and Fam111a_R2 for LM/Bc. Sanger sequencing was performed using the Fam111a_F primer at Genewiz/Azenta Life Sciences and consensus calling was manually checked from chromatograph traces using GeneSnap Viewer v5.3.2. Additional tail samples from mice used in these experiments and mice randomly selected from the breeding colony were screened by Transnetyx, Inc. (Cordova, TN) Automated Genotyping Services to confirm that the LM/Bc mice currently in-house remain homozygous for the 9 deleterious variants identified in Fam111a.

The human FAM111A protein (NP001299838) is a 611 amino acid serine protease that contains a conserved catalytic triad [reviewed in Welter and Machida, 2022] with chymotrypsin-like specificity at the C- terminus and an autocleavage site between Phe334 and Gly335 (Hoffmann et al., 2020; Kojima et al., 2020). Its known functions include 1) interacting directly with PCNA and nascent chromatin to load PCNA at the DNA replication fork; 2) removing protein obstacles at the replication fork to prevent stalling and promote DNA synthesis; and 3) acting as a host restriction factor in antiviral defense (Kojima et al., 2020; Nie et al., 2021) against SV40 polyomavirus (Fine et al., 2012; Tarnita et al., 2018), orthopoxvirus (Panda et al., 2017), and Zika virus (Ren et al., 2021). Depletion of FAM111A in virus-infected cells disrupts host cell nuclear pore proteins and barrier function, leading to increased formation of viral replication centers (Hoffmann et al., 2020; Nie et al., 2021; Welter and Machida, 2022).

The positions of the deleterious missense variants identified in Fam111a in LM/Bc mice and corresponding amino acid changes in the protein are shown in Table 4. The locations of known human variants in FAM111A and the 9 predicted deleterious variants in Fam111a in the LM/Bc mouse strain are shown in Figure 7. Five of the 9 LM/Bc variants are within or near the autocleavage site. Two are within the catalytic domain and alter the charge or polarity of an amino acid (aa 413, 464). The remaining 2 variants near the C-terminus are alternate variants at the same location; both result in a charge-altering amino acid change (aa 584).

TABLE 4.

Predicted deleterious SNVs in LM/Bc Fam111a. Whole exome sequencing data generated for the inbred LM/Bc and SWV strains was analyzed to identify potential variants in genes involved in Mg2+ homeostasis. The positions of the predicted deleterious missense variants identified in Fam111a that are unique to LM/Bc mice are shown along with the corresponding amino acid change in the protein. The T335K variant in LM/Bc mice corresponds to the T338A variant in humans that is associated with the osteocraniostenosis (OCS) phenotype (OMIM# 602361).

| SNV location (LM/Bc) | Position and AA change (mouse) | PROTEIN domain (mouse) | Side chain charge | CORRESPONDING human AA *conserved | Condition (human variant) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs52218749 | 330 His → Gln | Autocleavage site | Basic → Polar | Thr 333 | |

| rs49986153 | 335 Thr → Lys | Near autocleavage site | Polar → Basic | Thr 338* | OCS (T338A) |

| rs46660569 | 342 Lys → Thr | Basic → Polar | Lys 345* | ||

| rs240389514 | 345 Lys → Glu | Basic → Acidic | Lys 348* | ||

| rs47274130 | 352 Asp → Ala | Acidic → Nonpolar | Asp 355* | ||

| rs263904583 | 413 Glu → Lys | Catalytic domain | Acidic → Basic | Glu 415* | |

| rs258735034 | 464 Ser → Gly | Catalytic domain | Polar → Nonpolar | Ser 466* | |

| rs263418225 | 584 Asp → His | Acidic → Basic | Leu 582 | ||

| rs225390403 | 584 Asp → Val | Acidic → Nonpolar | Leu 582 |

FIGURE 7.

FAM111A protein plots with variants in humans and LM/Bc mice. FAM111A protein plots in humans and LM/Bc mice. Protein plots show locations of known protein domains (colored and annotated regions). Variants predicted to be deleterious found only in the LM/Bc strain are shown (top) as are likely pathogenic and pathogenic variants found in humans in ClinVar (bottom). The variants highlighted in red are aligned between mouse (T335) and human (T338). P: phosphorylation site.

In humans, most of the heterozygous de novo missense variants that have been identified result in ‘gain of function’ and hyperactivity of the protease (Hoffmann et al., 2020). Mutations in human FAM111A are associated with Kenny-Caffey Syndrome, type 2 (KCS2, OMIM #127000), in which patients exhibit increased bone density, growth retardation, macrocephaly, facial dysmorphism, hypoparathyroidism, and electrolyte imbalances, including hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia (Isojima et al., 2014; Abraham et al., 2017) or Gracile Bone Dysplasia/Osteocraniostenosis (GCLEB/OCS, OMIM #602361), characterized by skeletal/craniofacial malformations, and perinatal lethality (Unger et al., 2013; Muller et al., 2021; Rosato et al., 2022). In LM/Bc mice, only 1/9 of the identified deleterious missense variants correspond to a known human variant: the T335K variant in LM/Bc near the autocleavage site corresponds to the T338A variant in humans that have an OCS phenotype. Although we have not examined skeletal preparations, we do not grossly observe the severe skeletal malformation phenotype described for OCS in humans. We do, however, frequently observe microphthalmia (often unilateral) in the colony, and the occasional birth of small (runted) pups that fail to thrive, consistent with the ocular malformation and perinatal lethality phenotype described for humans with OCS. Based on results in the current study, LM/Bc mice exhibit hypomagnesemia and hypocalcemia, consistent with the human phenotype described for KCS2. Human variants in FAM111A are associated with hypomagnesemia and renal Mg2+ wasting; this phenotype in LM/Bc mice is thought to contribute to increased DTG-NTD susceptibility. Although several Fam111a deleterious variants unique to the LM/Bc strain were identified in this study, the significance of these mutations with respect to phenotype remains to be determined.

4 Discussion

Our results demonstrate the multifactorial etiology of NTDs and the complex gene-nutrient-environment interactions that contribute to risk for this type of congenital malformation. In addition, the data supports a role for maternal Mg2+ status as an underlying risk factor for DTG-NTDs. Magnesium is an important micronutrient, but its critical role in pregnancy is often overlooked. Genetic variants, inadequate dietary intake, and various disease conditions and/or medications can lead to chronic latent hypomagnesemia. In individuals who have one or more of these risk factors and subclinical hypomagnesemia, starting DTG in the months before conception may tip the balance towards an NTD affected pregnancy.

Numerous genetic variants predispose to hypomagnesemia. To test our hypothesis, we selected mouse strains on diverse genetic backgrounds with a range of inherently different basal plasma Mg2+ levels. LM/Bc mice had low basal plasma Mg2+ levels and elevated urinary Mg2+ excretion, but the underlying genetic cause was unknown. The LM/Bc strain was the most susceptible to DTG-NTDs, whereas C57BL/6J mice (highest basal plasma Mg2+) proved to be the most resistant. Our WES study identified several unique variants in the Fam111a gene in LM/Bc mice. In humans, FAM111A variants are associated with hypomagnesemia and renal Mg2+ wasting, consistent with the phenotype observed in LM/Bc mice. Pre-existing perturbations in Mg2+ homeostasis appear to be an underlying risk factor for DTG-NTDs in LM/Bc mice. However, it will be important to corroborate these findings by testing other mouse models with mutations in Mg2+ homeostasis pathway genes.

Our results also underscore the importance of adequate Mg2+ intake during pregnancy. Dietary intake of this micronutrient impacted both maternal plasma Mg2+ levels and susceptibility to DTG-NTDs. The food matrix also affected Mg2+ bio-accessibility, homeostasis, and susceptibility to DTG-NTDs. In LM/Bc dams maintained on a high Mg2+ (soy or casein) diet, none of the vehicle-treated litters were affected with an NTD. However, when exposed to DTG750, 63.2% of the LM/Bc litters on high Mg2+ soy diet had 1 or more NTD, while only 19% of litters were NTD-affected on the high Mg2+ casein diet. This was an unexpected difference, but can likely be attributed, at least in part, to phytate chelation of Mg2+ in the plant (soy)-based diet, which makes the 0.3% Mg2+ less bio-accessible (Gibson et al., 2018; Marolt et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2021). Notably, nutritionists, food scientists, and plant geneticists are aware of this issue, and are working on strategies to reduce phytic acid in cereal grains, legumes, and nuts to help alleviate this type of micronutrient deficiency in countries that rely heavily on plants as the major food source (Gupta et al., 2015; Vashishth et al., 2017).

Insufficient dietary Mg2+ intake and subclinical hypomagnesemia is a prevalent condition in humans worldwide, even in developed countries (Dalton et al., 2016). When LM/Bc mice were placed on casein diet with Mg2+ reduced to the NRC recommended control level (0.05%), plasma Mg2+ levels dropped significantly. Despite this, mice appeared healthy, and embryos developed normally in vehicle-treated dams. However, when LM/Bc dams on this diet were treated with DTG750, 85% of litters had 1 or more pups with exencephaly, and when given a lower dose of DTG500, 62% of litters were NTD-affected. SWV female mice placed on a severely restricted Mg2+ deficient diet became hypomagnesemic prior to conception, and 25% of litters were NTD-affected in the diet only control group. The proportion of NTD-affected litters increased to 75% when SWV dams were treated with DTG750. In addition to the data presented, offspring from 2 additional SWV litters on Mg2+ deficient diet were examined at GD 12.5. In both, the entire litter was in the process of being resorbed, suggesting that severe dietary Mg2+ deficiency is incompatible with fetal development and term pregnancy. Moving forward, to reproduce a more likely scenario in humans, it would be preferable to test DTG-NTD susceptibility in mice on a ‘low’ Mg2+ diet that is compatible with a healthy pregnancy, rather than one so severely Mg2+ deficient that diet alone causes NTDs and fetal death.

Another potential hidden dietary risk factor for altered Mg2+ homeostasis and NTDs is exposure to the mycotoxin fumonisin B1 (FB1). FB1 is a common contaminant found in maize-based foods worldwide, including many countries in Africa where rollout of DTG has been widespread (Yli-Mattila and Sundheim, 2022; Alberts et al., 2019; Omotayo et al., 2019). FB1 inhibits the enzyme ceramide synthase in de novo sphingolipid biosynthesis, causing accumulation of sphingoid bases (sphingosine and sphinganine) in human and mouse blood (Riley et al., 2015a; Riley et al., 2015b), and in mouse placentas and embryos (Gelineau-van Waes et al., 2005). Sphingosine is a potent inhibitor of the magnesium transporter TRPM7 (Qin et al., 2013). Subclinical hypomagnesemia in LM/Bc mice may therefore also have been a predisposing risk factor for susceptibility to FB1-NTDs (Gelineau-van Waes et al., 2012). In cultured mouse embryos, the incidence of FB1−NTDs could be reduced by adding folic acid to the culture medium (Sadler et al., 2002). Daily folic acid supplementation was also partially protective against FB1-NTDs in pregnant LM/Bc dams maintained on a folate-sufficient diet (Gelineau-van Waes et al., 2005). The diets used for the DTG studies were folate replete, but it will be important to determine if additional maternal folic acid supplementation is effective at reducing risk for DTG-NTDs.

In addition to dietary Mg2+ insufficiency, genetic variants that alter Mg2+ homeostasis represent known risk factors for NTDs. In the early embryo, magnesium plays an important role in cell migration and tissue morphogenesis through regulation of noncanonical Wnt/planar cell polarity signaling (Komiya et al., 2014; Komiya et al., 2017; Runnels and Komiya, 2020). Mg2+ transport via TRPM7 is important for mediolateral intercalation, cell polarity, adhesion, and axis elongation during early gastrulation, while Mg2+ transport via TRPM6 is required for radial intercalation during neural tube closure (Komiya et al., 2017; Runnels and Komiya, 2020). In mice, homozygous deletion of Trpm7 is embryonic lethal, and Trpm6 knockout mutants exhibit exencephaly and/or spina bifida occulta (Walder et al., 2009; Woudenberg-Vrenken et al., 2011; Jin et al., 2008). In humans, mutations in TRPM6 cause familial hypomagnesemia with secondary hypocalcemia (OMIM #607009) (Walder et al., 2002; Schlingmann et al., 2002), and a TRPM6 variant has been associated with meningomyelocele (Sarac et al., 2016).

Our WES analysis of inbred LM/Bc and SWV mouse strains and comparison to the C57BL/6J reference genome identified 9 unique homozygous de novo missense variants in Fam111a in the LM/Bc strain. In LM/Bc mice, several of the predicted deleterious Fam111a variants are near the autocleavage site (Figure 7), and the T335K variant corresponds to the pathogenic T338A variant in humans. Human GOF variants in FAM111A are associated with hypomagnesemia and hypermagnesuria (Viering et al., 2017), but exactly how FAM111a is involved in regulation of renal Mg2+ transport is not clear. Fam111a knockout (KO) mice on a C57BL/6N genetic background maintained on standard rodent chow containing 0.22% Mg2+ are viable, and display no overt phenotype (Ilenwabor et al., 2022). The KO mice have normal bone, kidney, and parathyroid morphology, and normal serum and urine Mg2+, Ca2+ and phosphate levels. Based on the lack of electrolyte abnormalities in Fam111a KO mice, and the fact that missense variants in humans lead to GOF, hypocalcemia, and hypomagnesemia, we predict that one or more of the missense Fam111a variants identified in LM/Bc mice also result in GOF, although this remains to be determined.

In humans, disease-causing mutations in FAM111A result in a phenotype that resembles activating mutations in the G protein-coupled Calcium Sensing Receptor (CASR). It has been proposed that FAM111A is a potential modifier of CASR (Tan et al., 2021), and that GOF in FAM111A protease activity may result in constitutive activation of CASR by preventing its internalization and downregulation (Pi et al., 2005; Mos et al., 2019). CASR is expressed in the parathyroid glands, intestines, and kidneys, and plays a pivotal role in homeostatic regulation of Ca2+ and Mg2+ (Chavez-Abiega et al., 2020). Heterozygous activating mutations in CASR cause Autosomal Dominant Hypocalcemia, type 1 (ADH1), or Bartter’s Syndrome, type V (both OMIM# 601198). ADH1 is characterized by low serum Ca2+ and hypercalciuria; Bartter’s Syndrome is more severe, and patients exhibit defective renal sodium chloride transport and increased urinary sodium excretion, which alters the electrochemical gradient necessary for Mg2+ and Ca2+ reabsorption. This leads to renal Mg2+ wasting, hypocalcemia, and hypomagnesemia (consistent with the phenotype observed in LM/Bc mice). In the thick ascending loop of Henley, CASR regulates paracellular transport of Ca2+ and Mg2+ through the cation-selective pore formed by claudin-16 (CLDN16) and claudin-19 (CLDN19) (Gunzel and Yu, 2009; Downie and Alexander, 2022). Human CLDN16 and CLDN19 variants are associated with familial hypomagnesemia with hypercalciuria (FHHNC; OMIN 248250), and a missense variant in CLDN19 has been associated with NTDs (Baumholtz et al., 2020).