Abstract

Learning in the mammalian lateral amygdala (LA) during auditory fear conditioning (tone – foot shock pairing), one form of associative learning, requires N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor-dependent plasticity. Despite this fact being known for more than two decades, the biophysical details related to signal flow and the involvement of the coincidence detector, NMDAR, in this learning, remain unclear. Here we use a 4000-neuron computational model of the LA (containing two types of pyramidal cells, types A and C, and two types of interneurons, fast spiking FSI and low-threshold spiking LTS) to reverse engineer changes in information flow in the amygdala that underpin such learning; with a specific focus on the role of the coincidence detector NMDAR. The model also included a Ca2s based learning rule for synaptic plasticity. The physiologically constrained model provides insights into the underlying mechanisms that implement habituation to the tone, including the role of NMDARs in generating network activity which engenders synaptic plasticity in specific afferent synapses. Specifically, model runs revealed that NMDARs in tone-FSI synapses were more important during the spontaneous state, although LTS cells also played a role. Training trails with tone only also suggested long term depression in tone-PN as well as tone-FSI synapses, providing possible hypothesis related to underlying mechanisms that might implement the phenomenon of habituation.

I. Introduction

Associative pairing of tone and shock signals is thought to underlie Pavlovian fear conditioning. In this conditioning paradigm, a subject is exposed to a neutral stimulus, called the conditioned stimulus, such as tone or light (e.g., 10 sec tones at 5 kHz, 80 dB) which co-terminates with an aversive, unconditioned stimulus such as foot-shock (e.g., 0.1–0.8 mA for 1–2 sec, delivered through the wires of the cage floor). Decades of research suggests that a brain region called amygdala is the primary site of plasticity related to fear and that activity of projections from the amygdala to downstream targets elicit a defensive, fear response in the mammal [1].

The neurons in the lateral nucleus of the amygdala (LA) and their synapses are putatively structured to acquire several critical memories critical for survival of the animal, e.g., fear and reward [2]. The intrinsic circuitry in the LA responsible for storing the fear memory after conditioning is shown in Fig. 1. The LA contains several neuronal types of which the four relevant ones in this model and their basal firing rates are as follows: principal neurons (PNs, PYR, red), and three inhibitory interneurons types: fast spiking (FSI, light blue), low-threshold spiking (LTS, medium blue), and VIP type (dark blue) [1]. Approximately 70% of the three types of these amygdala neurons receive tone and shock information in the form of spike trains (Fig.1). Through associative pairing, these stimuli engender plasticity in specific synapses during conditioning, via Hebb’s rule [2]. A coincidence-detection receptor located at excitatory synapses, the NMDA-receptor (NMDAR), is thought to implement this associative pairing. However, the details related to the role of NMDARs in generating network activity in the intrinsic circuitry, and how such information processing causes plasticity remain unclear.

Figure 1.

Cartoon of connectivity. Red/blue lines represent exc/inh connections

To shed light on information processing in LA, our computo-experimental team developed a biophysically realistic network model of the LA. For this we updated a prior model [3–7] by using recent data (e.g., [8]), and also included recent findings about the connection of the shock afferents to the PNs [9]. The new model was then used to gain insights into the role of NMDARs in modulating information processing during spontaneous and auditory tone states.

II. Method

Single cell models.

The LA, which receives both tone and shock inputs, was modeled with its glutamatergic pyramidal neurons (PNs) and gamma aminobutyric acid (GABAergic) interneurons. Principal cells were of two types, fully adapting (type A) and non-adapting (type C) pyramidal neurons [7]. GABAergic interneurons were of three types: parvalbumin-immunopositive fast-spiking interneurons (FSI), low-threshold spiking (LTS) and vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) cells. Models of single neurons and of the network were developed using experimental cellular and microcircuit parameters from the literature, including for network connectivity and synaptic strengths. The network model was run on the parallel NEURON 7.7 simulator [10], and the Brain Modeling Toolkit (BMTK) [11] with a fixed time step of 10 μs.

Mathematical equations for voltage-dependent ionic currents:

The dynamics for each compartment followed the standard Hodgkin-Huxley formulation [3–7].

Network model.

We developed a 4000-cell model of the LA by scaling down the number of neurons in a rodent LA while preserving the ratios of its principal cell to intraneuronal subpopulations.

Connectivity.

Intrinsic connectivity between different cell types were based on experimental data [8]. Briefly, the connections were random with the probabilities as follows: PN-PN 9% uni-directional (uni), 8% bi-directional (bi), 0.8% PN-FSI, 35% uni 15% bi 20%, PN-LTS 35% uni 23% bi 12%, PN-VIP 35 uni 35%, FSI-PN 53% uni 33% bi 20%, FSI-FSI 27% uni 23% bi 4%, FSI-LTS 40% uni 14% bi 26%, LTS-PN 35% uni 23% bi 12%, LTS-FSI 65% uni 39% bi 26%, LTS-LTS 27% uni 23% bi 4%, LTS-VIP 55% bi 55%, VIP-LTS 55 bi 55%, respectively. All synaptic weights were sampled from log-normal distributions [12] and their parameters were varied during the tuning process.

Synapses and Plasticity:

AMPA, NMDA, GABAA and GABAB currents were modeled with rise and decay times, and synaptic weights, using the standard formulation (e.g., [13]). Long-term plasticity was dependent on Ca2+ influx via the NMDA receptor following the Ca2+ learning rule [14]. The model also incorporated biologically seen short-term depression in PN-FSI and FSI-PN synapses [7] and short-term facilitation in PN-LTS synapses [15].

Extrinsic inputs:

In the spontaneous state, inputs to PNs and FSIs were uncorrelated 2 Hz Poisson spike trains with adjustable mean and SD. For the tone case, a random 70% of the tone-PN and tone-FSI synapses received 10 to 20 tone pips (5 KHz, 75 dB), each of 500 ms duration, with inter-trial intervals varying between 70–120 ms.

Analysis of network model responses:

For network results, we randomly sampled 30 each of PN, FSI and LTS cells, and analyzed their firing rates during spontaneous and tone states, for baseline, and 50% and 75% NMDAR-block cases.

III. Results

A. Biophysical single cell models replicate experimental in vitro data and in vivo spontaneous state data.

The model single cells reproduced experimental reports of passive properties and current injection responses. The cell models were from previous work (e.g., [7]) with each adjusted to match the specific experimental data for the species of rodents in this set of experiments. The VIP cell used the same model as the LTS cell since its role in the model is solely to inhibit the LTS cell at the onset of tone (Fig.1).

The single cell models were then inserted into the network (Fig. 1), and using a 2 Hz Poisson train for background input into each cell, the synaptic weights were tuned to reproduce in vivo basal firing rates reported in LA: 0.9 Hz (SD of ± 0.6 Hz), 22 Hz (± 16 Hz). and 11 Hz (± 5 Hz) for PNs, FSI and LTS cells, respectively. It is known that the local field potential in the amygdala reveals an intrinsically generated gamma rhythm (40–100 Hz), and this was reproduced in a recent biophysical model that showed weak gamma that matched in vivo data during the quiet waking state with only random Poisson inputs at 2 Hz [7]. We tuned our network to match the weak gamma seen during the quite waking state.

B. Role of NMDARs in modulating network activity

After matching the spontaneous (baseline) activity in the network, we explored the role of NMDARs in modulating network activity in both spontaneous and tone cases. The tone-PN and tone-PV lines that had 2 Hz Poisson trains during the spontaneous state now carried 20 tone pips during the tone state [8], as cited earlier. A random sample of 30 PNs, FSI and LTS cells from the network were used for the analyses below.

Information flow during spontaneous state is modulated primarily via NMDAR synapses onto FSIs

To study the role of NMDARs during information flow in the spontaneous case, we simulated the systemic injection of NMDAR-antagonist CPP in experiments [8] in the network model. Administration of CPP was modeled by reducing the maximal conductances of NMDARs in the network model by either 50% or 75%. The firing rates of the relevant model cell types, PNs (A and C types), FSIs, and LTS cells are shown in Figure 4 for three cases of NMDAR-block during the spontaneous state: 0 % (baseline), 50% and 75%. NMDAR-block minimally depressed the average firing rate of PNs from 0.89 Hz (baseline) to 0.92 and 0.94 Hz for the 50% and 75% block cases, respectively. However, the firing rate of FSIs went down significantly from 22 Hz (baseline) to 11 and 7 Hz for the 50% and 75% block cases, respectively. Experimental data show suppression of both PN-IN interactions and of the spontaneous firing rate of interneurons, but no change in either the spontaneous rate of PNs or in the strength of PN-PN interactions.

Figure 4.

Results for the three cases: baseline state with 2 Hz background input and 2Hz tone noise input, baseline + 50% MDA-block, and baseline+ 75% NMDA-block to mimic the effects of systemic CPP. Firing rate of FSIs but not other cell types change significantly with blockade of NMDA receptors. The findings match those in recent in vivo experiments (Figure 4.4 of Yan [8]).

Involvement of NMDARs is hypothesized to occur via coincident spikes when the footshock-evoked spikes in the postsynaptic cell coincide with tone driven synaptic activity. Although not discussed in the literature, such an involvement by NMDARs might also occur during the spontaneous state when random spiking of the postsynaptic cells coincides with tone driven synaptic activity. Results in Figure 4 indicate that the excitatory synapses onto PNs encounter fewer coincident spikes compared to such synapses onto FSIs. A reason for this would be the significantly higher firing rate of FSI cells that would increase the probability of temporal contiguity between the FSI spikes and those on its afferent lines. Another reason would be the much higher probability of PN-FSI compared to PN-PN connections. Finally, the synaptic weights between PN-PN synapses were found to be smaller than those for the PN-FSI synapses after tuning for the spontaneous state.

Information flow during tone is controlled by both NMDARs and LTS cells

The role of NMDARs during information flow in the tone case was studied along similar lines. The model firing rates of the relevant model cell types, PNs (A and C types), FSIs, and LTS cells this case is shown in Figure 5 for the 0 % (baseline), 50% and 75%. NMDAR-block cases. As expected, the tone-evoked firing rates of PNs and of FSIs were higher during the tone compared to the spontaneous state: 2 Hz for PNs and 36 Hz for FSIs. In the tone case, NMDAR-block decreased the average firing rate of PNs from 2 Hz (baseline) to 1.5 and 1.5 Hz for the 50% and 75% block cases, respectively. However, the firing rate of FSIs went down significantly from 36 Hz (baseline) to 20 and 15 Hz for the 50% and 75% block cases, respectively. Experimental data shows a suppression of both PN-IN interactions and of the spontaneous firing rate of interneurons, but no change in either the spontaneous rate of PNs or in the strength of PN-PN interactions. The LTS cells gate tone as shown in Fig. 1, and so play an important role during tone states.

Figure 5.

Tone response during trials of 500 ms tone pips. Tone is provided to the network with connectivity shown in Table 1. The resulting spikes of all cell types are summarized for the baseline and NMDA-block cases. Similar to the cases in Fig. 2, 50% and 75% of NMDA receptors are then blocked to mimic the effects of systemic CPP. Comparing baseline tone responses to the NMDA-block cases, the firing rate of FSI cells decreases, that of LTS cells increases, while that of Pyr cells remain unchanged. This trend matches that seen in in vivo experiments (Table 4.2 in Yan [8])

The contribution of NMDAR-based long-term plasticity in organizing information flow.

We then explored how long-term synaptic plasticity impacted the changes in tone response of PNs and FSIs after 10 tone trial habituation phase. As stated earlier, long-term synaptic plasticity is implemented by the Ca2+ learning rule that requires activation of NMDARs in the post-synaptic membrane. The model revealed that 16% of the tone driven excitatory PN synapses underwent long-term depression (LTD). The picture changed dramatically during ton-only trials, with 48% of the tone-PN synapses exhibiting depression. Significantly, none of the excitatory synapses exhibited long-term potentiation (LTP). For the tone-FSI synapse during baseline 12% of synapses had LTD during spontaneous case. Then during tone trials 75% of the tone-FSI synapses underwent LTD.

The findings related to plasticity could shed light on the phenomenon of habituation. For instance, animals are routinely habituated to tones prior to conditioning experiments. However, the underlying mechanisms that might implement the behavioral phenotype of habituation are unknown. Model findings suggest that a decrease in the synaptic strengths of afferents carrying tone to the amygdala might represent the neural correlates of habituation. This is also supported by noting that tone arrives to a random 70% of PNs and FSIs, and around the same number of tone synapses exhibit LTD. These issues are presently being explored. The next step would be extending the findings to the tone-shock case.

IV. Discussion

We developed a biophysical computational model of the BLA to explore how the intrinsic microcircuitry in the amygdala supports network activity and information processing across different brain states. The model provided the following insights related to the role of NMDARs: (i) Network activity is modulated by NMDARs at synapses onto FSIs during the resting state. This is due to the high firing rates of FSIs compared to PNs (Fig. 2); (ii) During tone trials, NMDARs again controlled network activity, but LTS cells also played an important role by their gating of tone onto PNs; (iii) although preliminary, it appears that habituation to tone involves LTD in both tone-PN and tone-FSI synapses. Detailed analyses of the data, including role of coincident spikes is on-going. Some of these predictions are also testable in experiments.

Fig.2.

Distributions of spontaneous firing rates of the cells

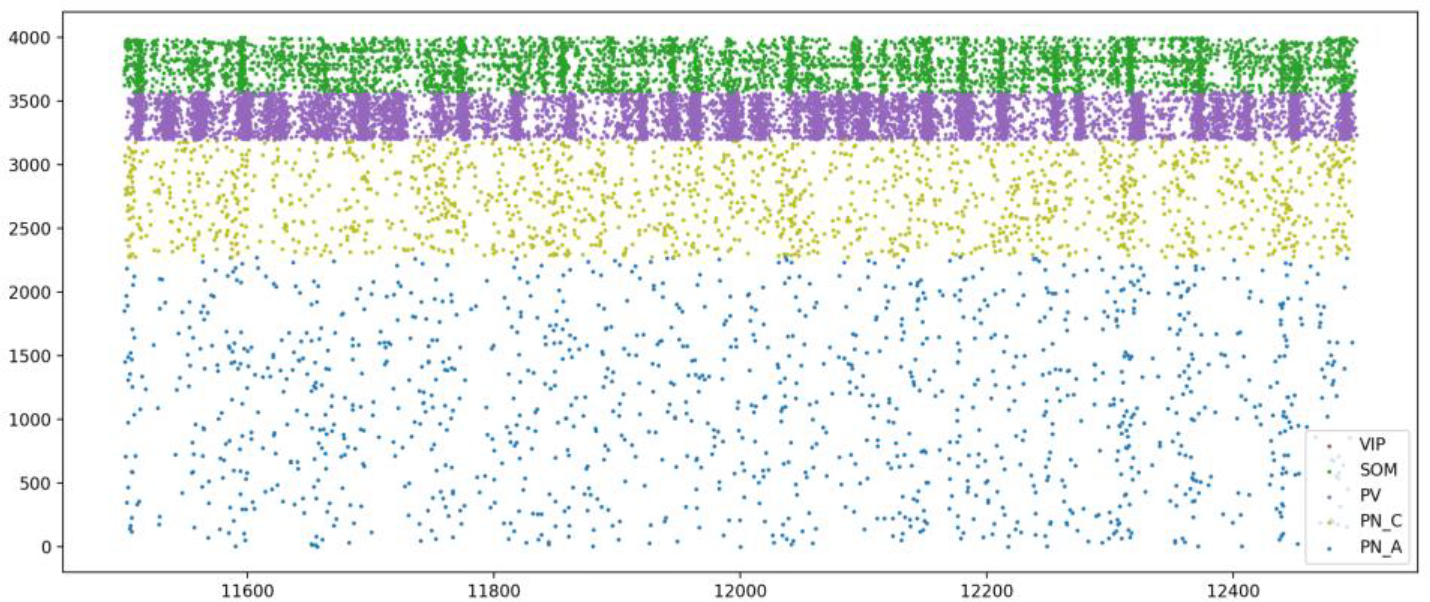

Figure 3.

Raster plot showing the activity of all cell types in the LA during the spontaneous state.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was supported in part by grants NIH MH122023 and NSF OAC-1730655 to SSN, and NHMRC and ARC grants to PS.

References

- [1].Sun Y, Gooch H, and Sah P, “Fear conditioning and the basolateral amygdala,” F1000Res, vol. 9, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Pape HC, and Pare D, “Plastic synaptic networks of the amygdala for the acquisition, expression, and extinction of conditioned fear,” Physiol Rev, vol. 90, no. 2, pp. 419–63, Apr, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Li G, Nair SS, and Quirk GJ, “A biologically realistic network model of acquisition and extinction of conditioned fear associations in lateral amygdala neurons,” J Neurophysiol, vol. 101, no. 3, pp. 1629–46, Mar, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kim D, Pare D, and Nair SS, “Mechanisms contributing to the induction and storage of Pavlovian fear memories in the lateral amygdala,” Learn Mem, vol. 20, no. 8, pp. 421–30, Aug, 2013a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kim D, Samarth P, Feng F, Pare D, and Nair SS, “Synaptic competition in the lateral amygdala and the stimulus specificity of conditioned fear: a biophysical modeling study,” Brain Struct Funct, vol. 221, no. 4, pp. 2163–82, May, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Feng F, Samarth P, Pare D, and Nair SS, “Mechanisms underlying the formation of the amygdalar fear memory trace: A computational perspective,” Neuroscience, vol. 322, pp. 370–6, May 13, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Feng F, Headley DB, Amir A, Kanta V, Chen Z, Paré D, and Nair SS, “Gamma oscillations in the basolateral amygdala: Biophysical mechanisms and computational consequences,” eNeuro, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. ENEURO.0388–18.2018, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Yan S, “NMDA Receptors in the Neural Circuit Underlying Fear Learning,” Ph.D. Dissertation vol. University of Queensland, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wolff SB, Grundemann J, Tovote P, Krabbe S, Jacobson GA, Muller C, Herry C, Ehrlich I, Friedrich RW, Letzkus JJ, and Luthi A, “Amygdala interneuron subtypes control fear learning through disinhibition,” Nature, vol. 509, no. 7501, pp. 453–8, May 22, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Carnevale N, and Hines M, The NEURON Book, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Gratiy SL, Billeh YN, Dai K, Mitelut C, Feng D, Gouwens NW, Cain N, Koch C, Anastassiou CA, and Arkhipov A, “BioNet: A Python interface to NEURON for modeling large-scale networks,” PLOS ONE, vol. 13, no. 8, pp. e0201630, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Buzsaki G, and Mizuseki K, “The log-dynamic brain: how skewed distributions affect network operations,” Nat Rev Neurosci, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 264–278, 04//print, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Destexhe A MZFSTJ, “Kinetic models of synaptic transmission,” Methods Neuronal Model, vol. 2, pp. 1–25, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Shouval HZ, Bear MF, and Cooper LN, “A unified model of NMDA receptor-dependent bidirectional synaptic plasticity,” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 99, pp. 10831–6, 2002b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Feng F, Headley DB, and Nair SS, “Model neocortical microcircuit supports beta and gamma rhythms.” pp. 91–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]