Abstract

Introduction:

In seven southern African countries (Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, Namibia, South Africa, Swaziland and Zimbabwe), following implementation of a measles mortality reduction strategy starting in 1996, the number of annually reported measles cases decreased sharply to less than one per million population during 2006–2008. However, during 2009–2010, large outbreaks occurred in these countries. In 2011, a goal for measles elimination by 2020 was set in the World Health Organization (WHO) African Region (AFR). We reviewed the implementation of the measles control strategy and measles epidemiology during the resurgence in the seven southern African countries.

Methods:

Estimated coverage with routine measles vaccination, supplemental immunization activities (SIA), annually reported measles cases by country, and measles surveillance and laboratory data were analyzed using descriptive analysis.

Results:

In the seven countries, coverage with the routine first dose of measles-containing vaccine (MCV1) decreased from 80% to 65% during 1996–2004, then increased to 84% in 2011; during 1996–2011, 79,696,523 people were reached with measles vaccination during 45 SIAs. Annually reported measles cases decreased from 61,160 cases to 60 cases and measles incidence decreased to <1 case per million during 1996–2008. During 2009–2010, large outbreaks that included cases among older children and adults were reported in all seven countries, starting in South Africa and Namibia in mid-2009 and in the other five countries by early 2010. The measles virus genotype detected was predominantly genotype B3.

Conclusion:

The measles resurgence highlighted challenges to achieving measles elimination in AFR by 2020. To achieve this goal, high two-dose measles vaccine coverage by strengthening routine immunization systems and conducting timely SIAs targeting expanded age groups, potentially including young adults, and maintaining outbreak preparedness to rapidly respond to outbreaks will be needed.

Keywords: Measles, Elimination, Africa, Immunization, Vaccination

1. Introduction

Measles caused an estimated 2.6 million deaths worldwide in 1980 [1]. Following widespread use of measles vaccine, estimated measles deaths decreased globally to 158,000 in 2011 [2]. In 2012, the World Health Organization (WHO) Global Vaccine Action Plan (GVAP) set a goal for measles elimination in five of the six WHO regions by 2020 [3]. In September, 2013 the WHO South-East Asia Region adopted a measles elimination goal by 2020; therefore, for the first time, all six WHO regions have a goal for measles elimination by 2020 or earlier [4].

During the early 1990s, the WHO Region of the Americas (ROA) pioneered a measles elimination strategy that included (1) an initial one-time nationwide ‘catch-up’ supplemental immunization activity (SIA) targeting children nine months to 14 years of age, (2) ‘keep-up’ measles vaccination through routine immunization of successive birth cohorts, (3) periodic ‘follow-up’ SIAs targeting children born since the initial SIA to prevent accumulation of susceptible individuals, and (4) establishing case-based measles surveillance [5]. The ROA goal of measles elimination, established in 1994, was achieved by 2002 [6]. In 2003, ROA countries adopted a goal for rubella elimination by 2010 and started implementing large, one-time ‘speed-up’ SIAs using combined measles-rubella-containing (MR) vaccine targeting children and adults, generally up to 29 or 39 years of age [7]. The last endemic rubella case was reported in 2009 [8]. The added benefit of combined MR SIAs was that adults who remained measles-susceptible were vaccinated, thus reducing the accumulation of measles-susceptible persons [9].

In 1996, seven southern African countries (Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, Namibia, South Africa, Swaziland, and Zimbabwe) with relatively high (~80%) MCV1 coverage in the WHO African Region (AFR) started implementing a measles mortality reduction strategy that was adapted from the ROA strategy [10]. During 1996–2000 in these seven countries, a nationwide “catch-up” measles SIA targeting children nine months to 14 years of age was completed, annually reported measles cases decreased from 61,160 to 7057 and reported measles deaths decreased to zero [10,11].

In 2001, based on the success in these seven countries, all 46 WHO-AFR countries became part of a global initiative to reduce estimated measles mortality by 50% by 2005, compared with the 1999 estimate [12]. The WHO-UNICEF recommended measles mortality reduction strategies included (1) first dose of measles-containing vaccine through routine services (MCV1) for children at nine months of age, (2) a one-time nationwide catch-up SIA targeting children nine months to 14 years of age and periodic follow-up SIAs targeting children 9–59 months of age, (3) measles case-based surveillance with laboratory testing, and (4) improved measles case management [13]. Additionally, in 2010 the World Health Assembly established the following WHO-recommended targets to measure progress towards measles eradication: (1) reduce annual measles incidence to <1 laboratory-confirmed or epidemiologically-linked case per million and maintain that level; (2) >95% coverage annually of both MCV1 and a second dose of measles-containing vaccine (MCV2) both nationally and in every district or equivalent administrative unit [14,15].

During 2000–2008, in AFR, reported measles cases decreased 93% and estimated measles deaths decreased 92% from 371,000 to 28,000 [16]. However, measles-susceptible persons accumulated over a prolonged time period with suboptimal vaccination coverage, and during 2009–2010, confirmed measles outbreaks occurred in 28 AFR countries, including the seven southern African countries that started SIA implementation in 1996. In 2011, AFR countries adopted a goal for measles elimination by 2020 [17]. To inform AFR measles elimination efforts and identify likely causes of the measles resurgence, measles vaccination, epidemiological and laboratory surveillance data in the seven southern African countries from 1996 to 2011 were analyzed.

2. Methods

2.1. Routine immunization

WHO/UNICEF MCV1 coverage estimates for children aged one year and MCV2 coverage estimates reported by countries using the WHO/UNICEF joint reporting form (JRF) were analyzed [11].

2.2. Supplemental immunization activities

SIA administrative coverage, calculated by dividing the number of children vaccinated by the number of children targeted for vaccination, reported by each country to WHO were reviewed.

2.3. Measles surveillance

Annual measles cases reported by each country using the JRF during 1996–2011 and national measles case-based surveillance data reported by each country to WHO during 2009–2011 were analyzed [11]. JRF-reported cases were classified as suspected cases for analysis, since these data were either from case-based surveillance or the Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response system of aggregate numbers of suspected measles cases [18]. For surveillance, the suspected measles case definition used was an illness characterized by maculopapular rash, fever and ≥1 of the following symptoms: conjunctivitis, coryza, and cough, or any patient in whom the clinician suspects measles. Investigations of suspected cases included collection of information on sex, place of residence (urban/rural), age, vaccination status, and collection of a serum specimen for laboratory testing. According to WHO-AFR guidelines, suspected measles cases were classified as confirmed by laboratory, epidemiologic linkage and/or clinical criteria. Laboratory-confirmed measles cases were defined as having measles-specific immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibody positive test result, and not receiving a measles vaccination during the 30 days prior to rash onset. An epidemiologically-linked case was defined based on WHO-AFR guidelines as meeting the suspected measles case definition and having contact (i.e., lived in the same district or adjacent districts with plausibility of transmission) with a laboratory-confirmed measles case with rash onset within the preceding 30 days. A clinically-compatible case was defined as meeting the measles case definition, and with no sample available for laboratory testing and no evidence of epidemiological linkage to a laboratory-confirmed case.

Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute). Testing for measles-specific IgM antibody was performed at national measles laboratories using a standard enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay (Enzygnost ELISA™, Siemens, Marburg, Germany). RNA was extracted from available specimens using the QIAamp® viral RNA mini kit (QIAGEN®), and amplified by RT-PCR using primers MeV214 and MeV216 designed to target a 634 nucleotide region coding for the 3’terminus of the nucleoprotein (N) gene (measles genotyping kit v2.0 CDC, Atlanta). Sequences were analyzed using Sequencher software (Gene Codes Corporation 4.1.4, Ann Arbor, MI) and phylogenetic and molecular evolutionary analyses were conducted using MEGA version 5 software using the maximum likelihood algorithm with bootstrap test of phylogeny relative to WHO measles virus reference strains [19].

3. Results

3.1. Routine immunization

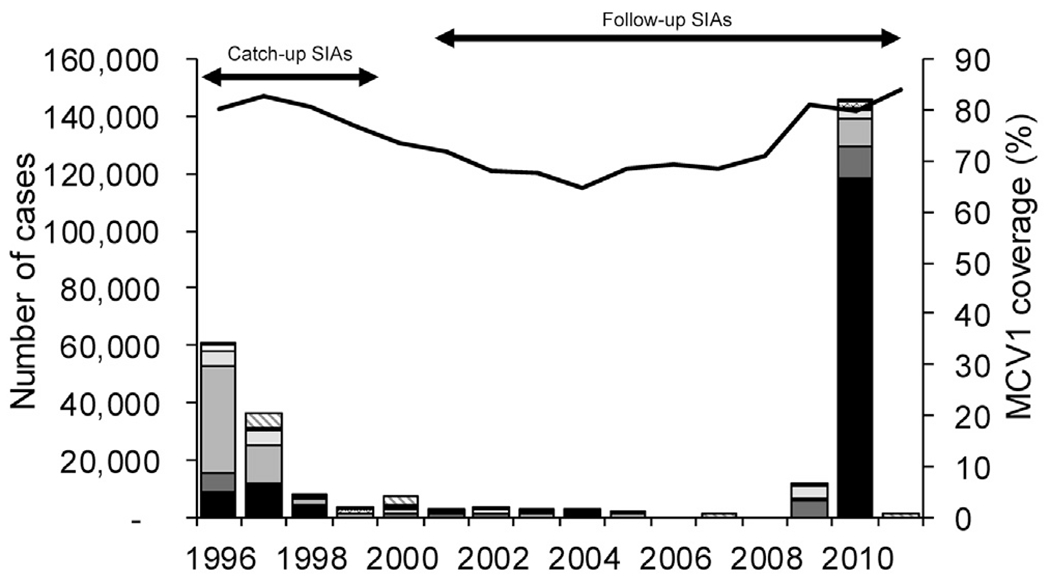

During 1996–2011, MCV1 was recommended to be administered at nine months of age. MCV2 though routine services at 18 months of age was introduced in South Africa in 2000, Lesotho in 2001, Swaziland in 2002, and Botswana in 2011. During 1996–2011, WHO/UNICEF MCV1 coverage estimates increased in all seven countries, with absolute increases ranging from 2% in South Africa to 16% in Swaziland (Table 1). In 2011, MCV1 coverage estimates ranged from 74% in Namibia to 98% in Swaziland. The weighted average of MCV1 coverage estimates in the seven countries decreased from 80% to 65% during 1996–2004, then increased to 84% in 2011 (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Measles supplementary immunization activities (SIA) and estimated coveragea with the routine first dose measles-containing vaccine (MCV1), seven southern African countries, 1996–2011.

| Country | Extent of SIA | Dates of SIA | Target age group | Target population | Number of target population vaccinated | SIA vaccination coverage (%)b | 1996 MCV1 coverage (%) | 2011 MCV1 coverage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Botswana | National | Jul–Aug 97 | 9M–14Y | 344,280 | 347,265 | 101 | 89 | 94 |

| National | May 98 | 9M–14Y | 234,960 | 246,420 | 105 | |||

| National | May 01 | 9–59M | 160,000 | 136,000 | 85 | |||

| National | Oct 05 | 9–59M | 180,450 | 179,587 | 100 | |||

| National | Nov 09 | 9–59M | 171,038 | 195,841 | 115 | |||

| Lesotho | National | Oct 99 | 9–59M | 266,329 | 159,933 | 60 | 82 | 85 |

| National | Oct 00 | 5–14Y | 624,994 | 469,005 | 75 | |||

| National | Apr–May 03 | 9–59M | 204,786 | 178,522 | 87 | |||

| National | Oct 07 | 9–59M | 212,800 | 196,416 | 92 | |||

| Nationalc | Sep 10 | 6M–15Y | 615,109 | 558,335 | 91 | |||

| Malawi | National | Oct 98 | 9M–14Y | 4,179,229 | 4,747,452 | 114 | 90 | 96 |

| Sub-national | Aug 02 | 9–59M | 1,583,664 | 1,906,985 | 120 | |||

| National | Sep 05 | 9–59M | 1,851,176 | 2,137,152 | 115 | |||

| National | Oct 08 | 9–59M | 2,120,557 | 2,087,375 | 98 | |||

| Nationalc | Aug 10 | 9M–15Y | 6,370,409 | 6,785,428 | 107 | |||

| Namibia | National | Jun 97 | 9M–14Y | 737,977 | 677,538 | 92 | 61 | 74 |

| National | Jun 00 | 9–59M | 285,504 | 257,590 | 90 | |||

| National | Jun 03 | 9–59M | 340,000 | 318,240 | 94 | |||

| Sub-national | Aug 06 | 9–59M | 353,270 | 318,905 | 90 | |||

| National | Jun 09 | 9–59M | 246,501 | 256,006 | 104 | |||

| Sub-national | Feb–Mar 10 | 6–59Md | NA | NA | Range by district 88–115 | |||

| South Africa | Sub-national | Aug 96 | 9M–14Y | 3,559,252 | 3,317,400 | 93 | 76 | 78 |

| Sub-national | Aug 96 | 9M–4Y | 2,173,753 | 1,786,048 | 82 | |||

| National | May 97 | 5–14Y | 4,045,498 | 3,495,415 | 86 | |||

| Sub-national | May 97 | 9M–14Y | 4,278,598 | 3,281,321 | 77 | |||

| National | May 00 | 9–59M | 3,384,890 | 3,005,319 | 89 | |||

| National | Jul 04 | 9–59M | 3,791,127 | 3,501,447 | 92 | |||

| Sub-national | Apr–May 05 | 9–59M | 2,674,829 | 2,273,604 | 85 | |||

| National | May 07 | 9–59M | 4,349,921 | 3,880,585 | 89 | |||

| Sub-nationale | May 09 | 9–59M | 229,514 | 186,334 | 81 | |||

| Sub-nationale | Sep–Nov 09 | 5–19Y | 396,114 | 304,981 | 77 | |||

| Sub-nationale | Oct–Nov 09 | 5–19Y | 2,566,587 | 2,251,305 | 88 | |||

| Nationalc | May–Jul 10 | 6M–15Y | 14,930,510 | 14,592,721 | 98 | |||

| Swaziland | National | Jun 98 | 9–59M | 147,545 | 146,626 | 99 | 82 | 98 |

| National | May 99 | 5–14Y | 276,732 | 244,739 | 88 | |||

| National | Jun 02 | 9–59M | 157,381 | 127,829 | 81 | |||

| National | Jul 06 | 9–59M | 153,504 | 140,143 | 91 | |||

| National | Jul 09 | 9–47M | 91,124 | 87,592 | 96 | |||

| National | Oct–Nov 10 | 9–59M | 125,845 | 112,740 | 90 | |||

| Zimbabwe | National | Jun 98 | 9M–14Y | 5,279,248 | 4,929,475 | 93 | 88 | 92 |

| National | Jun–Jul 02 | 9–59M | 1,808,552 | 1,537,263 | 85 | |||

| Sub-national | Jul 03 | 9–59M | 375,782 | 353,235 | 94 | |||

| National | Jun 06 | 9–59M | 1,479,957 | 1,407,510 | 95 | |||

| National | Jun 09 | 9–59M | 1,523,344 | 1,408,589 | 92 | |||

| Nationale | May 10 | 6M–14Y | 5,310,480 | 5,164,307 | 97 | |||

| Total | 80 | 84 |

M: months, Y: years, NA: not available, ORI: Outbreak response immunization campaign, SIA: supplemental immunization activity.

WHO/UNICEF estimates of MCV1 coverage among children aged one year.

Values >100% indicate that the intervention reached more persons than the estimated target population.

Planned SIA with expanded age group in response to the outbreak.

Target age in Opuwo district was ≥6 M.

ORI campaign in response to the outbreak.

Fig. 1.

Reported measles cases*, estimated coverage** with the routine first dose of measles-containing vaccine (MCV1), and measles supplemental immunization activities*** (SIAs), seven southern African countries, 1996–2011.

*Measles cases reported annually to WHO by member states through the WHO/UNICEF Joint Reporting Form.

**Population-weighted average using United Nations Development Programme population estimates and annual national WHO/UNICEF MCV1 coverage estimates for children aged 1 year for 1996–2011

***In each country, measles SIAs started with an initial catch-up SIA targeting all children aged 9 months to 14 years and then periodic follow-up SIAs, generally targeting all children born since the last SIA, conducted nationwide every 2–4 years targeting children aged 9–59 months, in some cases, expanded age groups were used in follow-up SIAs.

Reports of MCV2 coverage began in South Africa in 2000, Lesotho in 2001, and Swaziland in 2002; the most recent available reported data for MCV2 coverage was 70% for Lesotho in 2009, 83% for South Africa in 2010, and 74% for Swaziland in 2010. In Botswana MCV2 was introduced in 2011; however, no reported coverage data was available. By 2012, MCV2 had not been introduced in Malawi, Namibia or Zimbabwe.

3.2. Supplemental immunization activities

During 1996–2011, 45 nationwide or sub-national follow-up SIAs were implemented, including five each in Botswana, Lesotho, and Malawi, six each in Namibia, Swaziland, and Zimbabwe, and 12 in South Africa (Table 1). During the 45 SIAs, a total of 79,696,523 people received measles vaccination and reported coverage was ≥95% in 15 SIAs (34%), 90–94% in 13 SIAs (30%), 80–89% in 12 SIAs (27%), and <80% in four SIAs (9%) (Table 1).

3.3. Measles surveillance

From 1996 to 1999, the number of annually reported measles cases from the WHO/UNICEF JRF in the seven countries decreased 95%, from 61,160 to 2988 (Fig. 1). The number of reported cases in 2000 increased to 7057 due to an increase in reported cases from Botswana and South Africa. During 2001–2008, the number of annually reported measles cases decreased 98%, from 2528 to 60 and measles incidence decreased 98% from 33 cases per million to <1 case per million, with all seven countries reporting decreases in cases and incidence.

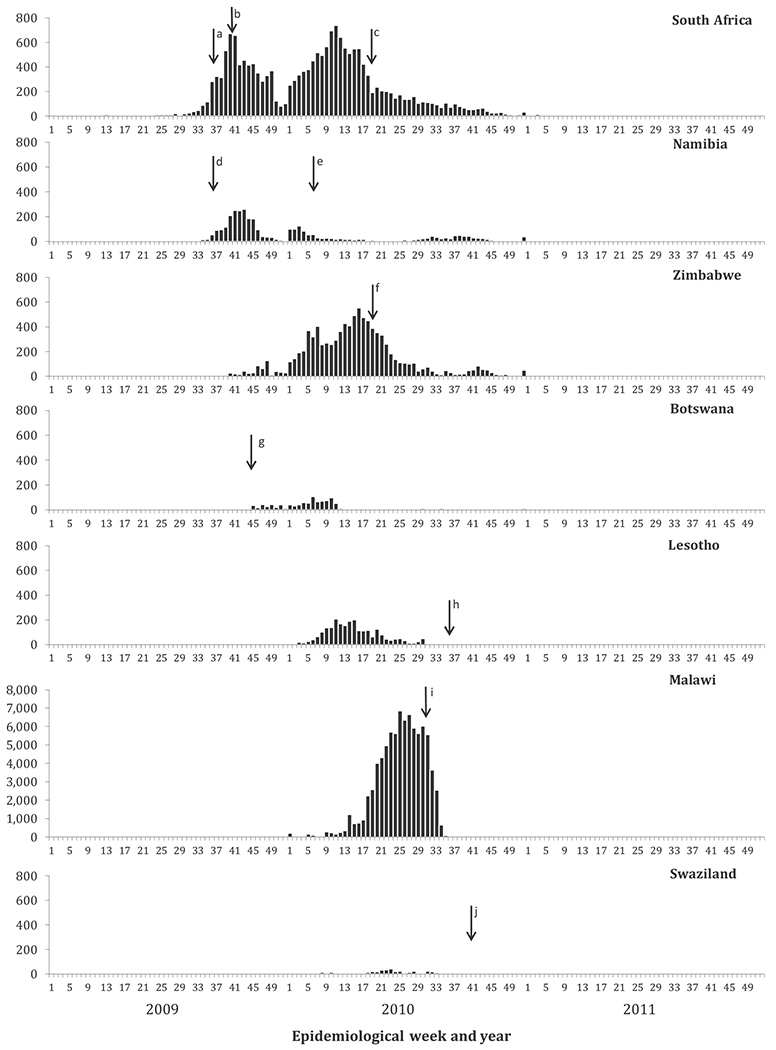

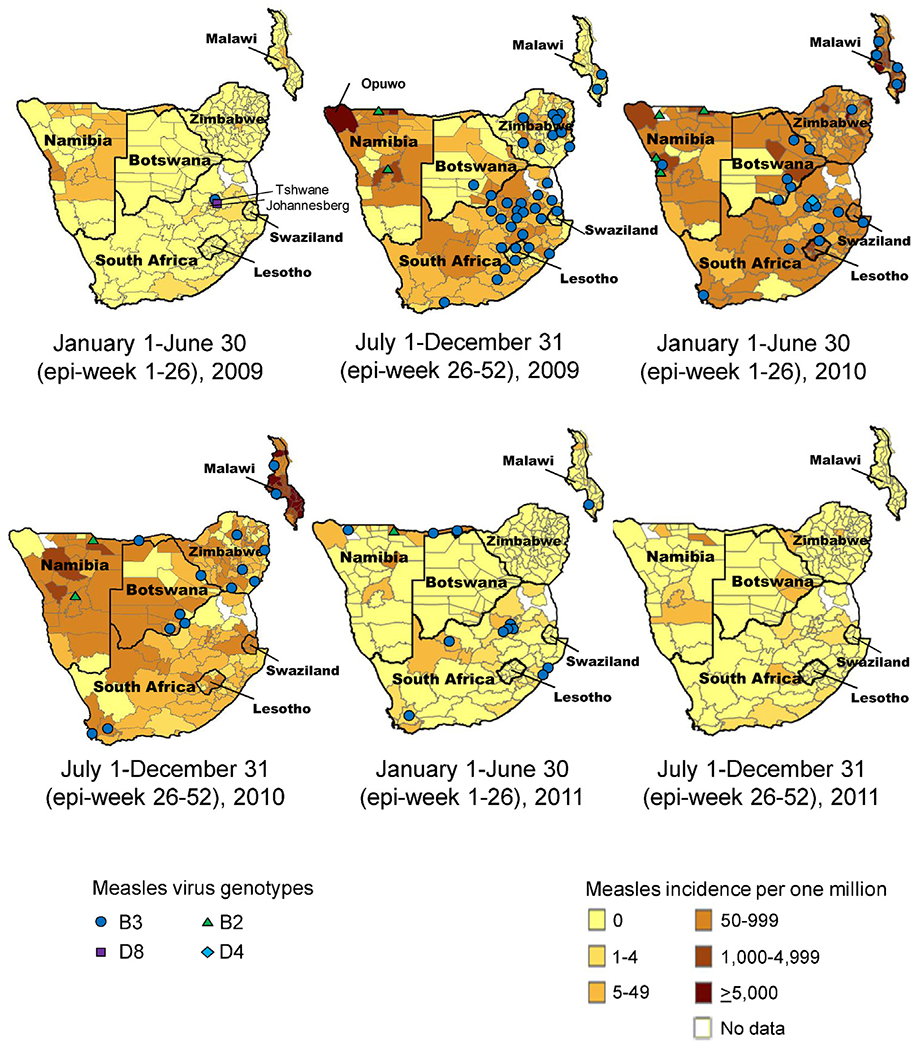

During 2001–2004, isolated outbreaks occurred; the number of JRF-reported suspected measles cases was 1166 in 2001 and 1043 in 2002 from South Africa, 1278 in 2002 from Namibia, and 1116 from Malawi in 2004. During 2006–2008, between zero and 242 suspected measles cases were reported annually through the JRF from each of the seven countries. However, during 2009–2010, large outbreaks were reported in all seven countries. Starting in epidemiologic week (epi-week) 24 of 2009, clusters of confirmed cases were reported in South Africa, primarily from the Tshwane and Johannesburg municipal districts in Gauteng Province (Figs. 2 and 3).

Fig. 2.

Confirmed* measles cases by epidemiological week, seven southern African countries, 2009 (N = 9546), 2010 (N = 111,186), and 2011 (N = 267).

*Confirmed measles cases were defined by laboratory confirmation, epidemiological link, or classified as clinically compatible.

Note: In 2009, 33 cases in Namibia had missing date data. In 2010, 23,548 cases in Malawi had missing date data.

M: months, Y: years, ORI: Outbreak response immunization campaign, SIA: supplemental immunization activity.

aSub-national ORI campaign in response to the outbreak conducted in September–November 2009, target age 5–19Y, 77% coverage achieved.

bSub-national ORI campaign in response to the outbreak conducted in October–November 2009, target age 5–19Y, 88% coverage achieved.

cNational planned SIA with expanded age group in response to the outbreak conducted in May–July 2010, target age 6M–15Y, 98% coverage achieved.

dSub-national ORI campaigns in response to the outbreak conducted September–December 2009 in 6 districts, target age 6–59M, coverage achieved NA.

eSub-national ORI campaigns in response to the outbreak conducted in February–March 2010 in 4 districts, target age 6–59M in 3 districts, >6M in 1 district, irrespective of previous vaccination status, coverage range by district 88–115%.

fNational ORI campaign in response to the outbreak conducted in May 2010, target age 6M-14Y, 97% coverage achieved.

gNational campaign conducted in November 2009, target age 9–59M, 115% coverage achieved.

hNational planned SIA with expanded age group in response to the outbreak conducted in September 2010, target age 6M–15Y, 91% coverage achieved.

iNational planned SIA with expanded age group in response to the outbreak conducted in August 2010, target age 9M–15Y, 107% coverage achieved.

jNational campaign conducted in October–November 2010, target age 9–59M, 90% coverage achieved.

Fig. 3.

Annualized reported confirmed measles incidence* and measles virus genotypes detected by district, seven southern African countries, 2009–2011.

*Annualized reported measles incidence was calculated by dividing the number of reported confirmed measles cases from national measles case-based surveillance data by annual population estimates from national census projections.

Note: Each genotype symbol on the map indicates between 1 and 37 specimens of that genotype in a district.

Reported confirmed cases increased sharply starting in epi-week 35 in South Africa, and peaked with 674 cases in epi-week 40. The outbreak in South Africa coincided with an increase in confirmed cases in Namibia starting in epi-week 31, 2009 (Fig. 2). In July–December 2009 in Namibia, confirmed measles incidence ≥50 cases per million was reported in 21 districts in northern Namibia and along the Angola border, including Opuwo district with the highest confirmed measles incidence, 12,454 cases per million (Fig. 3). Increases in confirmed cases started in Botswana, Malawi, and Zimbabwe by epi-week one, 2010 and in Lesotho and Swaziland by epi-week five, 2010 (Fig. 2). Weekly reported confirmed cases reached peaks of 107 cases in epi-week six in Botswana, 209 cases in epi-week 11 in Lesotho, 555 cases in epi-week 16 in Zimbabwe, 42 cases in epi-week 23 in Swaziland, and 6869 cases in epi-week 25 in Malawi. After January 2011, sporadic cases occurred in all seven countries.

During 2009–2011, through measles case-based surveillance in the seven countries, 181,826 suspected measles cases were reported (Table 2). Of these, 51,700 (28%) had a specimen sent for laboratory testing to detect measles-specific IgM; 21,265 (41%) tested positive, 28,691 (55%) tested negative, 891 (2%) had indeterminate test results, and 853 (2%) had unknown test results (Table 2). During 2009–2011, 144,580 confirmed cases were reported from the seven countries (Table 3); of these, 21,265 (15%) were laboratory-confirmed, 115,767 (80%) were confirmed by epidemiological link, and 7548 (5%) were confirmed by clinically compatible classification (data not shown). Malawi accounted for 108,717 (75%) confirmed cases. In six of the seven countries (all except Namibia), measles incidence peaked in 2010, ranging from 237 cases per million population in South Africa to 7293 cases per million population in Malawi (Table 3).

Table 2.

Laboratory results for measles-specific IgM antibody testing of suspected measles cases, seven southern African countries, 2009–2011.

| Suspected measles cases | Measles IgM laboratory test

result |

Rubella IgM laboratory test

result |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measles IgM tested |

IgM + |

IgM− |

Indeterminate |

Unknown |

Positivity Ratea | Rubella IgM tested |

Rubella IgM + |

||||||||||

| Country | Year | n | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | % | n | % | n | % |

| Botswana | 2009 | 595 | 592 | 99 | 177 | 30 | 294 | 50 | 24 | 4 | 97 | 16 | 36 | 535 | 90 | 4 | 1 |

| 2010 | 1411 | 1117 | 79 | 563 | 50 | 491 | 44 | 62 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 50 | 534 | 38 | 13 | 2 | |

| 2011 | 735 | 735 | 100 | 6 | 1 | 596 | 81 | 1 | 0 | 132 | 18 | 1 | 497 | 68 | 193 | 39 | |

| Total | 2741 | 2444 | 89 | 746 | 31 | 1381 | 57 | 87 | 4 | 230 | 9 | 34 | 1566 | 57 | 210 | 13 | |

| Lesotho | 2009 | 189 | 189 | 100 | 20 | 11 | 166 | 88 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 188 | 99 | 73 | 39 |

| 2010 | 2728 | 702 | 26 | 372 | 53 | 281 | 40 | 49 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 53 | 746 | 27 | 78 | 10 | |

| 2011 | 169 | 150 | 89 | 0 | 0 | 150 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 150 | 89 | 78 | 52 | |

| Total | 3086 | 1041 | 34 | 392 | 38 | 597 | 57 | 52 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 38 | 1084 | 35 | 229 | 21 | |

| Malawi | 2009 | 529 | 528 | 100 | 16 | 3 | 511 | 97 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 316 | 60 | 40 | 13 |

| 2010 | 109,267 | 852 | 1 | 370 | 43 | 477 | 56 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 44 | 851 | 1 | 26 | 3 | |

| 2011 | 659 | 651 | 99 | 21 | 3 | 630 | 97 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 651 | 99 | 223 | 34 | |

| Total | 110,455 | 2031 | 2 | 407 | 20 | 1618 | 80 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 20 | 1818 | 2 | 289 | 16 | |

| Namibia | 2009 | 2716 | 951 | 35 | 344 | 36 | 522 | 55 | 61 | 6 | 24 | 3 | 37 | 802 | 30 | 25 | 3 |

| 2010 | 2234 | 698 | 31 | 167 | 24 | 489 | 70 | 42 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 622 | 28 | 157 | 25 | |

| 2011 | 875 | 854 | 98 | 59 | 7 | 453 | 53 | 9 | 1 | 333 | 39 | 11 | 852 | 97 | 134 | 16 | |

| Total | 5825 | 2503 | 43 | 570 | 23 | 1464 | 58 | 112 | 4 | 357 | 14 | 27 | 2276 | 39 | 316 | 14 | |

| South Africa | 2009 | 15,246 | 15,204 | 100 | 6086 | 40 | 8559 | 56 | 559 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 15,215 | 100 | 3009 | 20 |

| 2010 | 23,264 | 16,189 | 70 | 11,904 | 74 | 4028 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 257 | 2 | 75 | 5910 | 25 | 1236 | 21 | |

| 2011 | 8632 | 8610 | 100 | 116 | 1 | 8460 | 98 | 34 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8590 | 100 | 3226 | 38 | |

| Total | 47,142 | 40,003 | 85 | 18,106 | 45 | 21,047 | 53 | 593 | 1 | 257 | 1 | 46 | 29,715 | 63 | 7471 | 25 | |

| Swaziland | 2009 | 240 | 240 | 100 | 16 | 7 | 223 | 93 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 240 | 100 | 135 | 56 |

| 2010 | 769 | 617 | 80 | 301 | 49 | 311 | 50 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 49 | 614 | 80 | 94 | 15 | |

| 2011 | 77 | 77 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 77 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 77 | 100 | 19 | 25 | |

| Total | 1086 | 934 | 86 | 317 | 34 | 611 | 65 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 34 | 931 | 86 | 248 | 27 | |

| Zimbabwe | 2009 | 853 | 401 | 47 | 127 | 32 | 264 | 66 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 32 | 351 | 41 | 29 | 8 |

| 2010 | 9762 | 1468 | 15 | 600 | 41 | 836 | 57 | 32 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 41 | 482 | 5 | 97 | 20 | |

| 2011 | 876 | 875 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 873 | 100 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 873 | 100 | 448 | 51 | |

| Total | 11,491 | 2744 | 24 | 727 | 26 | 1973 | 72 | 40 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 27 | 1706 | 15 | 574 | 34 | |

| Total | 181,826 | 51,700 | 28 | 21,265 | 41 | 28,691 | 55 | 891 | 2 | 853 | 2 | 42 | 39,096 | 22 | 9337 | 24 | |

The number of IgM+ divided by the number with a known test result.

Table 3.

Confirmed measles cases by sex, setting, age group, and vaccination status, seven southern African countries, 2009–2011.

| Country | Year | Annual Incidence per 1 milliona | Casesb | Male |

Settingc |

Age Group |

Vaccination Status |

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | % | Urban | Rural | <9 M | 9M–4Y | 5–9Y | 10–14Y | ≥15 Y | 1 dose | ≥2 doses | None | Missing | ||||||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||||

| Botswana | 2009 | 137 | 271 | 126 | 47 | 129 | 48 | 139 | 52 | 25 | 9 | 30 | 11 | 30 | 11 | 75 | 28 | 109 | 41 | 35 | 13 | 14 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 219 | 81 |

| 2010 | 454 | 912 | 454 | 50 | 223 | 24 | 689 | 76 | 100 | 11 | 89 | 10 | 118 | 13 | 245 | 27 | 357 | 39 | 206 | 23 | 173 | 19 | 11 | 1 | 522 | 57 | |

| 2011 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 43 | 2 | 29 | 5 | 71 | 2 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 43 | 1 | 14 | 1 | 14 | 1 | 14 | 2 | 29 | 1 | 14 | 3 | 43 | |

| Total | 1190 | 583 | 49 | 354 | 30 | 833 | 70 | 127 | 11 | 119 | 10 | 151 | 13 | 321 | 27 | 467 | 39 | 242 | 20 | 189 | 16 | 15 | 1 | 744 | 63 | ||

| Lesotho | 2009 | 11 | 23 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 0 | 3 | 13 | 8 | 35 | 9 | 39 | 3 | 13 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 87 |

| 2010 | 1112 | 2415 | 1108 | 48 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 162 | 7 | 489 | 20 | 714 | 30 | 708 | 29 | 338 | 14 | 70 | 3 | 123 | 5 | 48 | 2 | 2174 | 90 | |

| 2011 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 2438 | 1108 | 48 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 162 | 7 | 492 | 20 | 722 | 30 | 717 | 29 | 341 | 14 | 71 | 3 | 125 | 5 | 48 | 2 | 2194 | 90 | ||

| Malawi | 2009 | 1 | 17 | 11 | 65 | 1 | 6 | 16 | 94 | 3 | 18 | 6 | 35 | 7 | 41 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 82 | 0 | 0 |

| 2010 | 7293 | 108,679 | 54,746 | 51 | 81 | 22 | 287 | 78 | 14,566 | 14 | 29,822 | 28 | 16,663 | 16 | 16,087 | 15 | 30,244 | 28 | 48 | <1 | 1 | <1 | 266 | <1 | 108,364 | 100 | |

| 2011 | 1 | 21 | 7 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 100 | 5 | 24 | 4 | 19 | 4 | 19 | 2 | 10 | 6 | 29 | 4 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 19 | 13 | 62 | |

| Total | 108,717 | 54,764 | 51 | 82 | 20 | 324 | 80 | 14,574 | 14 | 29,832 | 28 | 16,674 | 16 | 16,090 | 15 | 30,250 | 28 | 55 | <1 | 1 | <1 | 284 | <1 | 108,377 | 100 | ||

| Namibia | 2009 | 910 | 2041 | 1057 | 52 | 1179 | 94 | 75 | 6 | 407 | 20 | 427 | 21 | 170 | 8 | 119 | 6 | 889 | 44 | 92 | 5 | 20 | 1 | 628 | 31 | 1301 | 64 |

| 2010 | 632 | 1442 | 708 | 49 | 76 | 13 | 513 | 87 | 77 | 5 | 418 | 29 | 340 | 24 | 194 | 14 | 405 | 28 | 290 | 20 | 56 | 4 | 408 | 28 | 688 | 48 | |

| 2011 | 37 | 87 | 43 | 49 | 69 | 79 | 18 | 21 | 10 | 11 | 25 | 29 | 19 | 22 | 10 | 11 | 23 | 26 | 26 | 30 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 9 | 50 | 57 | |

| Total | 3570 | 1808 | 51 | 1324 | 69 | 606 | 31 | 494 | 14 | 870 | 25 | 529 | 15 | 323 | 9 | 1317 | 37 | 408 | 11 | 79 | 2 | 1044 | 29 | 2,039 | 57 | ||

| South Africa | 2009 | 134 | 6646 | 3450 | 54 | 1384 | 90 | 146 | 10 | 1576 | 24 | 1498 | 23 | 521 | 8 | 685 | 10 | 2366 | 36 | 18 | <1 | 17 | <1 | 105 | 2 | 6,506 | 98 |

| 2010 | 237 | 11,904 | 808 | 52 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 4344 | 36 | 2477 | 21 | 1005 | 8 | 1723 | 14 | 2355 | 20 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 11,904 | 100 | |

| 2011 | 3 | 150 | 74 | 52 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 35 | 23 | 53 | 35 | 9 | 6 | 21 | 14 | 32 | 21 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 150 | 100 | |

| Total | 18,700 | 4332 | 53 | 1384 | 90 | 146 | 10 | 5955 | 32 | 4028 | 22 | 1535 | 8 | 2429 | 13 | 4753 | 25 | 18 | <1 | 17 | <1 | 105 | 1 | 18,560 | 99 | ||

| Swaziland | 2009 | 15 | 17 | 13 | 76 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 100 | 5 | 29 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 53 | 2 | 12 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 94 |

| 2010 | 386 | 458 | 244 | 53 | 22 | 5 | 436 | 95 | 67 | 15 | 69 | 15 | 71 | 16 | 167 | 36 | 84 | 18 | 9 | 2 | 11 | 2 | 41 | 9 | 397 | 87 | |

| 2011 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 475 | 257 | 54 | 22 | 5 | 453 | 95 | 72 | 15 | 70 | 15 | 71 | 15 | 176 | 37 | 86 | 18 | 10 | 2 | 11 | 2 | 41 | 9 | 413 | 87 | ||

| Zimbabwe | 2009 | 45 | 564 | 233 | 46 | 77 | 17 | 379 | 83 | 26 | 5 | 212 | 38 | 196 | 35 | 110 | 20 | 20 | 4 | 11 | 2 | 9 | 2 | 541 | 96 | 3 | <1 |

| 2010 | 710 | 8924 | 3978 | 45 | 5164 | 58 | 3760 | 42 | 859 | 11 | 2522 | 33 | 1743 | 23 | 1316 | 17 | 1184 | 16 | 711 | 8 | 388 | 4 | 5907 | 66 | 1,918 | 21 | |

| 2011 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 50 | 1 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 9,490 | 4213 | 45 | 5241 | 56 | 4141 | 44 | 885 | 11 | 2736 | 33 | 1939 | 24 | 1426 | 17 | 1204 | 15 | 723 | 8 | 398 | 4 | 6448 | 68 | 1,921 | 20 | ||

| Total | 144,580 | 67,065 | 51 | 8407 | 56 | 6503 | 44 | 22,269 | 16 | 38,147 | 27 | 21,621 | 15 | 21,482 | 15 | 38,418 | 27 | 1527 | 1 | 820 | 1 | 7985 | 6 | 134,248 | 93 | ||

M: months, Y: years, NA: not available.

Data: Case-based surveillance data. 2009 and 2010 data from South Africa include measles case-based surveillance data and measles laboratory data.

Annual measles incidence was calculated using confirmed measles cases as reported by countries using measles case-based surveillance to the World Health Organization (WHO) African Regional Office and population estimates from the United Nations Population Division.

Confirmed by laboratory testing, epidemiological link, or clinically compatible as reported by countries using measles case-based surveillance to the WHO African Regional Office.

Setting classification reported as either urban or rural; percents are of those without a missing value.

Of 144,580 confirmed cases reported during 2009–2011, 14,910 (10%) had information on residence; of these, 8407 (56%) were from urban settings (Table 3). The proportion of reported cases from an urban setting was highest in 2009 in Namibia (94%) and in 2010 in Zimbabwe (58%). Of the 141,937 (98%) cases with age information, 38,418 (27%) were adults ≥15 years of age (Table 3); of these 14,065 (37%) were 15–19 years, 7981 (21%) were 20–24 years, 7474 (19%) were 25–29 years, and 8898 (23%) were ≥30 years of age. Information about vaccination status was missing for 134,248 (93%) confirmed cases. However, of the 10,332 (7%) confirmed cases with vaccination history, 7985 (77%) were unvaccinated for measles (Table 3).

During 2009–2011, genotype data were available for 282 reported cases: two from Swaziland, 16 from Lesotho, 16 from Botswana, 25 from Malawi, 34 from Zimbabwe, 64 from Namibia, and 125 from South Africa (Fig. 3 and Supplemental Fig. 1). Of the 282 genotype results, 229 (81%) were B3, 51 (18%) were B2, one (<1%) was D4, and one (<1%) was D8. The genotype B3 viruses were of a single strain detected in all seven countries and found to be closely related to measles virus previously detected in West Africa; in Namibia, the genotype B2 strain was found to be closely related to measles virus previously detected in Angola and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The genotype D8 was detected in 2009 and the genotype D4 was detected in 2010, both in South Africa.

4. Discussion

Following intensive efforts to control measles in southern Africa starting in 1996, reported measles incidence was reduced to <1 per million population in Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, Namibia, South Africa, Swaziland and Zimbabwe during 2006–2008. Thereafter, these seven countries experienced large outbreaks, starting in 2009 in South Africa and Namibia before spreading to neighboring countries, predominantly with a single strain of measles virus genotype B3 previously detected in West Africa. Of confirmed measles cases during the resurgence, 16% were among infants <9 months of age and 27% among adults.

Outbreak investigations conducted during the resurgence determined that the principal cause of these outbreaks was failure to vaccinate eligible persons, causing measles-susceptibility that accumulated over a prolonged time period [20–27]. During the past decade, the significant reduction in measles burden likely led to complacency in measles vaccination efforts, including SIA planning and implementation and routine immunization services. Additionally, suboptimal vaccination coverage contributed to outbreaks among known at-risk subpopulations, for example, the nomadic populations in Namibia, and the apostolic religious communities reluctant to accept vaccinations for faith-based reasons in Zimbabwe, Malawi, Botswana, Swaziland and South Africa [28]. Measles outbreak response immunization (ORI) activities conducted during the resurgence included ‘selective’ vaccination of unvaccinated children 6–59 months of age at routine services and ‘non-selective’ mass campaigns targeting age groups ranging from 6–59 months to ≥6 months of age. Following ORI, cases decreased; however, ORI implementation generally was not rapid and occurred months after the start of outbreaks.

In some settings, immunization program data were found to be unreliable for guiding vaccination efforts. For example, in South Africa, during 2005–2011, reported MCV1 coverage ranged from 83% to 99% while WHO/UNICEF estimates that incorporate available survey results ranged from 63% to 78% [29,30]. In the seven countries prior to the resurgence, reported SIA administrative coverage estimates were high; however post-SIA coverage surveys were not routinely conducted to validate reported coverage and outbreaks occurred among children in SIA target age groups, suggesting suboptimal SIA coverage and inaccuracies in reported coverage.

These findings should be considered with several limitations. First, reported vaccination coverage data may be biased by inaccurate estimates of target populations and reporting of doses delivered. Second, surveillance systems do not detect all measles cases because reporting is incomplete from communities and health facilities. Third, although adequate case investigation is recommended for >80% of suspected cases, 90% and 93% of the cases had missing information for urban/rural and vaccination status, respectively. Therefore, analysis of residence and vaccination status might not be representative of all cases. Finally, comparing annual reported measles case totals and incidence is difficult when sensitivity and completeness of reporting vary by country and by year.

The 2010 World Cup soccer games hosted by South Africa during June–July, 2010, coincided with the peak of the measles outbreak in that country, resulting in infection of susceptible visitors and subsequent exportation of measles virus to several countries. In general, the Southern Africa economic block has a relatively high volume of cross-border movement by traders, business people, students, tourists and migrant workers; international migration and travel provide opportunities for measles virus importations [31]. In countries that share open borders and frequent migration, coordinated vaccination strategies, including synchronized SIAs prior to large public gatherings, e.g. international sporting events, could be considered to prevent outbreaks.

Optimal ORI strategies, including timing, geographic scope, and target age groups are uncertain and remain a global research priority [32]. Infants born with transferred maternal antibodies from vaccine-induced protection rather than from naturally acquired measles virus infection generally result in lower geometric mean titers that wane faster, leaving the infant unprotected in early infancy [33,34]. Also, children born to HIV-infected mothers have lower concentrations of passively acquired maternal antibodies [35,36], and measles antibody titers decline more rapidly after vaccination among HIV-infected compared with non-HIV infected persons [36–38]. Therefore, WHO recommends ORI target age groups include young infants starting at 6 months of age, and in areas with high incidence of both HIV infection and measles, the first dose of measles vaccine may be offered as early as 6 months of age, in addition to the routine two-dose schedule [39].

The relative contribution of HIV infection to measles virus transmission in southern Africa appears to have been minimal [27,40,41]. In 2002 in South Africa and during 2009–2011 in South Africa and Malawi, investigations determined the outbreaks were caused primarily by suboptimal vaccination coverage and that high HIV-prevalence played a minor role in the accumulation of measles-susceptible persons [40,42]. Moreover, Biellik et al. reported in 2002 that measles was nearly eliminated in these countries despite high HIV prevalence [10].

To achieve measles elimination, high population immunity is needed and WHO recommends >95% two-dose measles vaccination coverage at the national and district levels as a measure to monitor progress toward measles elimination [14]. To achieve high coverage, routine outreach services to communities known to be measles-susceptible or with poor access to immunization services are needed. Additionally, these communities should be included in SIA micro-planning and SIA planning should start 6–8 months prior to implementation [43]. The shift of measles epidemiology towards older age groups is well documented [44]; therefore, adequate resources should be made available to ensure timely SIA implementation, and if indicated, using expanded target age groups [14,39,45].

Measles and rubella elimination strategies, including using MR vaccine, were effectively integrated in the ROA, leading to elimination of both measles and rubella. However, in AFR, by the start of 2013, MR vaccine was not publicly available in 43 of the 46 countries and rubella virus circulated widely [46]. In 2012, the GAVI Alliance committed funding for eligible countries to introduce rubella-containing vaccine starting with a one-time MR SIA targeting children nine months to 14 years of age. But, unlike the ‘speed-up’ MR SIAs in ROA that started within ten years after initial measles SIAs and included adults, MR SIAs in AFR will start >17 years after initial measles SIAs and will not include adults; therefore, existing measles susceptibility among adults will remain, increasing the need for high population immunity among infants and children needed to achieve elimination.

The Measles & Rubella Initiative 2012–2020 Global Measles and Rubella Strategic Plan, with goals aligned to the GVAP, aims to (i) achieve and maintain high levels of population immunity through high coverage with two doses of MR vaccines, (ii) establish effective surveillance to monitor disease and evaluate progress, (iii) develop and maintain outbreak preparedness for rapid response and appropriate case management, (iv) communicate and engage to build public confidence in and demand for vaccination, and (v) conduct research and development to support operations and improve vaccination and diagnostic tools [47]. To implement these strategies and improve data quality for guiding program efforts, adequate resources and intensified efforts are needed to achieve measles elimination in AFR by 2020.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the work of all immunization officers, surveillance medical officers, and measles laboratory personnel across AFR involved in the implementation of the strategies for measles control. We also thank the Measles & Rubella Initiative for providing financial and technical assistance to member states for strategy implementation and efforts to achieve measles elimination in AFR.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the World Health Organization or the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Authors declare that this article has not been previously presented.

Financial interest: The authors do not have a financial or proprietary interest in a product, method, or material or lack thereof.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.089.

References

- [1].Wolfson LJ, Strebel PM, Gacic-Dobo M, et al. Has the 2005 measles mortality reduction goal been achieved? A natural history modelling study. Lancet 2007;369(9557):191–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Global control and regional elimination of measles, 2000–2011. MMWR 2013;62(2):27–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].World Health Organization. Global vaccine action plan 2011–2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. http://www.who.int/immunization/global_vaccine_action_plan/GVAP_doc_2011_2020/en/index.html [accessed September 25, 2013]. [Google Scholar]

- [4].World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia. Resolution of the WHO Regional Committee for South-East Asia. SEA/RC66/R5. Measles Elimination and Rubella/Congenital Rubella Syndrome Control; 2013.

- [5].de Quadros CA, Olive JM, Hersh BS, et al. Measles elimination in the Americas, evolving strategies. JAMA 1996;275(3):224–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Castillo-Solorzano CC, Matus CR, Flannery B, et al. The Americas: paving the road toward global measles eradication. J Infect Dis 2011;204(Suppl. 1):S270–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Castillo-Solorzano C, Marsigli C, Bravo-Alcantara P, et al. Elimination of rubella and congenital rubella syndrome in the Americas. J Infect Dis 2011;204(Suppl. 2):S571–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progress toward control of rubella and prevention of congenital rubella syndrome–worldwide, 2009. MMWR 2010;59(40):1307–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Andrus JK, de Quadros CA, Solorzano CC, Periago MR, Henderson DA. Measles and rubella eradication in the Americas. Vaccine 2011;29(Suppl. 4):D91–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Biellik R, Madema S, Taole A, et al. First 5 years of measles elimination in southern Africa: 1996–2000. Lancet 2002;359(9317):1564–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].World Health Organization. WHO vaccine-preventable diseases: monitoring system 2013 global summary; 2013. http://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/globalsummaty [accessed July 8, 2013].

- [12].World Health Organization. World Health Assembly resolution WHA 56.20. In: Reducing global measles mortality. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- [13].World Health Organization and UNICEF. Measles mortality reduction and regional elimination: strategic plan 2001–2005. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. http://www.who.int/immunizatiomdelivery/adc/measles/measles_strategic_plan.pdf [accessed July 8, 2013]. [Google Scholar]

- [14].World Health Organization. Monitoring progress towards measles elimination. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2010;85(49):490–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].World Health Organization. Framework for verifying elimination of measles and rubella. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2013;88(9):89–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].World Health Organization. Global reductions in measles mortality 2000–2008 and the risk of measles resurgence. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2009;84(49):509–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].World Health Organization African Regional Office, Resolution AFR/RC61/14. 61st Session of the WHO regional committee for Africa: Towards the elimination of measles in the African Region by 2020; 2011. http://www.afro.who.int/en/sixty-first-session.html [accessed March 1, 2013].

- [18].World Health Organization, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Technical guidelines integrated disease surveillance and response in the African region. 2nd ed. Brazzaville, Republic of Congo/Atlanta, USA: World Health Organization; 2010. p. 398. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, et al. MEGA5: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol 2011;28:2731–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Final report to the Ministry of Health-Malawi. Technical assistance for the 2009–2010 nationwide measles outbreak from the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Namibia measles outbreak, 2009–2011. Report of epidemiologic investigation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [22].World Health Organization IST/ESA. Retrospective documentation of measles outbreak & response in Malawi; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kisakye A. Documentation of a Measles Outbreak in the Kingdom of Swaziland. World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [24].World Health Organization IST/ESA. Retrospective documentation of measles outbreak & response in Lesotho; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [25].World Health Organization. Measles outbreak in Botswana 2010. IST technical support mission; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [26].World Health Organization. Measles outbreak in South Africa, key findings and recommendations. WHO/IST technical support mission; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Minetti A, Kagoli M, Katsulukuta A, et al. Lessons and challenges for measles control from unexpected large outbreak in Malawi. Emerg Infect Dis 2013;19(2):202–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Measles outbreaks and progress toward measles preelimination—African region, 2009–2010. MMWR 2011;60(12):374–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Burton A, Monasch R, Lautenbac B, et al. WHO and UNICEF estimates of national infant immunization coverage: methods and processes. Bull World Health Organ 2009;87(July (7)):535–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Burton A, Kowalski R, Gacic-Dobo M, et al. A formal representation of the WHO and UNICEF estimates of national immunization coverage: a computational logic approach. PLoS One 2012;7(10):e47806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Yameogo KR, Perry RT, Yameogo A, et al. Migration as a risk factor for measles after a mass vaccination campaign Burkina Faso, 2002. Int J Epidemiol 2005;34(3):556–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Goodson JL, Chu SY, Rota PA, et al. Research priorities for global measles and rubella control and eradication. Vaccine 2012;30(32):4709–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Martins CL, Garly ML, Bale C, et al. Protective efficacy of standard Edmonston-Zagreb measles vaccination in infants aged 4.5 months: interim analysis of a randomised clinical trial. BMJ 2008;337:a661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Aaby P, Martins CL, Garly ML, et al. The optimal age of measles immunisation in low-income countries: a secondary analysis of the assumptions underlying the current policy. BMJ Open 2012;2(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Moss WJ, Monze M, Ryon JJ, et al. Prospective study of measles in hospitalized, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected and HIV-uninfected children in Zambia. Clin Infect Dis 2002;35(2):189–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Scott S, Moss WJ, Cousens S, et al. The influence of HIV-1 exposure and infection on levels of passively acquired antibodies to measles virus in Zambian infants. Clin Infect Dis 2007;45(11):1417–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Choudhury SA, Hatcher F, Berthaud V, et al. Immunity to measles in pregnant mothers and in cord blood of their infants: impact of HIV status and mother’s place of birth. J Natl Med Assoc 2008;100(12):1445–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Moss WJ, Scott S, Mugala N, et al. Immunogenicity of standard-titer measles vaccine in HIV-1-infected and uninfected Zambian children: an observational study. J Infect Dis 2007;196(3):347–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].World Health Organization. Measles vaccines: WHO position paper. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2009;84(35):349–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Sartorius B, Cohen C, Chirwa T, et al. Identifying high-risk areas for sporadic measles outbreaks: lessons from South Africa. Bull World Health Organ 2013;91(3):174–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Helfand RF, Moss WJ, Harpaz R, Scott S, Cutts F. Evaluating the impact of the HIV pandemic on measles control and elimination. Bull World Health Organ 2005;83(5):329–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].McMorrow ML, Gebremedhin G, van den Heever J, et al. Measles outbreak in South Africa, 2003–2005. S Afr Med J 2009;99(5):314–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa Measles SIAs Field Guide; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Goodson JL, Masresha BG, Wannemuehler K, Uzicanin A, Cochi S. Changing epidemiology of measles in Africa. J Infect Dis 2011;204(Suppl. 1):S205–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].World Health Organization. Implementing the Reaching Every District (RED) Approach: A Guide for District Health Management Teams; August 2008. https://www.who.int/immunization_delivery/systems_policy/AFRO-RED-guide_2008.pdf [accessed July 8, 2013].

- [46].Goodson JL, Masresha B, Dosseh A, et al. Rubella epidemiology in Africa in the prevaccine era, 2002–2009. J Infect Dis 2011;204(Suppl. 1):S215–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].World Health Organization. Global Measles and Rubella Strategic Plan 2012–2020; 2012. http://www.who.int/immunization/newsroom/Measles_Rubella_StrategicPlan_2012_2020.pdf [accessed March 7, 2013].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.