Abstract

Cyberbullying is a growing problem for middle school students. Bystander interventions that train witnesses to positively intervene can prevent cyberbullying. Through six focus groups, we explored forty-six middle school students’ experiences with cyberbullying and opportunities for school-based prevention programs to encourage positive bystander behavior. Focus groups were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using content analysis. Students viewed cyberbullying as an important problem with significant consequences. They noted hesitancy in reporting to parents and school personnel and felt more comfortable discussing cyberbullying with a near-peer (e.g., older sibling or friend). Students desired combining school-based and online programming with near-peer mentorship. This study suggests need for targeted prevention programs that center middle school students’ lived experiences with cyberbullying and their preferences for learning and utilizing positive bystander strategies.

Keywords: cyberbullying, middle school, bullying prevention, bystander intervention

Introduction

Cyberbullying is a significant problem in the United States. Cyberbullying has been defined as, “the use of digital-communication tools (such as the internet and cell phones) to make another person feel angry, sad, or scared, usually again and again” (Common Sense Media, 2020). Rates of cyberbullying have increased during the COVID-19 pandemic while other forms of bullying have decreased (Patchin, 2021). Recent national survey data suggests cyberbullying is highest around the time students are in middle school (Hinduja, 2021). In the 30 days before being surveyed, one-quarter of youth ages 12–15 reported experiencing cyberbullying (Hinduja, 2021), and in another survey the same proportion of youth reported witnessing cyberbullying in the past month (Holfeld & Mishna, 2018). While cyberbullying often co-occurs with traditional bullying (Tural Hesapcioglu & Ercan, 2017), cyberbullying presents a unique context. The availability, permanence, and anonymity of social media creates added opportunities for bullying and in some cases harsher forms of bullying (Nesi, Choukas-Bradley, & Prinstein, 2018).

Cyberbullying has many forms that can be overt (e.g., harassment or heated online exchanges) or covert in nature (e.g., social exclusion or isolation; Kowalski, Limber, & Agatston, 2012) and can vary in severity level. Particularly when cyberbullying is overt or severe, such as when important aspects of identity are targeted (e.g., race, ethnicity, gender, or sexuality), it can negatively impact mental health (Duarte et al, 2018; Tynes et al, 2020). However, even less severe or covert forms of cyberbullying can emotionally impact middle school students, such as through anger, stress, and loneliness (Ortega et al, 2009).

When cyberbullying occurs at an early age, it is linked with deleterious social, health, and academic impacts (Kowalski et al, 2014) and is associated with poor outcomes over the life course (Kim, Boyle, & Georgiades, 2018). Both victimization and perpetration of cyberbullying can contribute to a range of poor outcomes, including mental health impacts (e.g., depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, and suicidality; Kowalski et al., 2014; Kwan et al., 2020). Cybervictimization in particular has shown a robust association to suicidal thoughts and behavior among youth (Nesi et al., 2021). Given its potentially serious and long-lasting consequences, the prevention of cyberbullying among middle school students is a critical public health need (National Academies of Sciences & Medicine [NASM], 2016).

School-Based Cyberbullying Prevention Efforts

Existing school-based bullying prevention programs often focus on universal bullying prevention approaches, which combine individual-level prevention (e.g., holding meetings with students involved with bullying) with prevention activities at a classroom, school, and community level (NASM, 2016). Universal bullying prevention programs on average are associated with a 20–23% decrease in bullying perpetration and a 17–20% decrease in victimization (Ttofi & D. Farrington, 2011). In other cases, prevention approaches are targeted for youth who are at risk for engaging in or experiencing bullying (NASM, 2016). Targeted prevention programs for cyberbullying have used strategies such as educational campaigns to improve recognition and response to cyberbullying (Chisholm, 2014) and empathy training, an approach that challenges normative beliefs of aggression and supports protective online environments (Ang, 2015). A meta-analysis of cyberbullying prevention programs showed reductions in perpetration of 9–15% and victimization of 14–15% (Gaffney et al, 2019).

Some school-based programs involve students, a strategy that could extend dialogue beyond parents and school personnel to whom only 38–57% of middle school students disclose cyberbullying (NCES, 2019). While engaging students must be done carefully to mitigate risks of reinforcing victimization (Ttofi & D. P. Farrington, 2011), peer-led interventions can be beneficial, especially when students voluntarily agree to participate (Zambuto et al 2020) and receive sufficient training (Menesini & Nocentini, 2012). A recent meta-analysis (Gaffney et al., 2021) found programs that involved students reduced bullying perpetration by 12.5% and victimization by 9%, significantly more than programs that did not involve students. Peer-led interventions offer benefits to peer leaders, such as improvements in self-esteem and social stress (King & Fazel, 2021) and digital literacy skills (Agatston et al., 2012) that could aid their response to cyberbullying. Further, utilizing near-peer mentors (e.g., college or high school student mentors for middle or elementary students)shows promise for improving student engagement (Destin et al 2020) and mentees’ self-esteem and social relations (Haft et al, 2019).

Cyberbullying as a Peer-Group Process and Bystander Interventions

Bullying is often conceptualized as a peer-group process, in which students can be involved as perpetrators, victims, or witnesses. Youth who are witnesses or “bystanders” can play a critical role in cyberbullying prevention. Notably, 80% of incidents of bullying involve a witness, and when bystanders intervene there is a 50% chance of stopping bullying behavior (Polanin, Espelage, & Pigott, 2012). Bystanders may intervene in positive ways by emotionally supporting victims, discouraging bullying behavior, and reporting to a parent or school personnel (Allison & Bussey, 2016). Youth who use these positive bystander behaviors are sometimes referred to as “upstanders.” Upstanders may challenge the bully’s status of power over the victim (Salmivalli, 2010) while ameliorating negative consequences on victims (Desmet et al., 2012; DeSmet et al, 2019). Conversely, bystanders may also intervene in negative ways, such as encouraging or joining the perpetrator in bullying behavior, which may worsen the severity of the bullying (Salmivalli, 2010) and its mental health consequences (DeSmet et al., 2019). Despite their potential influence, most bystanders remain passive when they witness bullying (Lenhart et al., 2011), often influenced by a lack of skill and confidence in effective response to cyberbullying (Desmet et al., 2016). In experimental studies, 50–90% of youth did not directly intervene in response to various cyberbullying simulations (Dillon & Bushman, 2015; Freis & Gurung, 2013; Shultz, Heilman, & Hart, 2014). While passivity may not directly condone cyberbullying, perpetrators may perceive bystanders’ inaction as tacit approval of their actions (Bastiaensens et al., 2014).

Bystander interventions are targeted prevention programs that promote positive bystander behaviors, such as supporting the victim and seeking help from a trusted adult, and target reduction of negative or passive bystander responses that may exacerbate bullying (Cantone et al., 2015; Polanin et al., 2012). In effective bystander interventions, students learn to recognize bullying through identifying inappropriate behaviors and problem situations, gain skills for intervening, and make a commitment to intervene (Banyard, Moynihan, & Plante, 2007). School-based bystander interventions often use role play in classrooms to behaviorally enact positive bystander behaviors in response to hypothetical bullying scenarios (Polanin et al., 2012). Some programs have also used videos to illustrate positive bystander behaviors and technology for tracking and offering feedback to students on bystander behaviors (Polanin et al., 2012).

School-based prevention programs that encourage positive bystander behaviors have shown promise across a range of outcomes (Cantone et al., 2015; Torgal et al., 2021) and are considered integral to bullying prevention. For example, Steps to Respect (Brown, Low, Smith, & Haggerty, 2011; Frey et al, 2009), which promotes positive bystander behaviors as part of a comprehensive bullying prevention program for elementary school children, showed a range of positive effects, including improved school climate and lower perpetration rates. Another intervention, KiVA (Karna et al., 2011) for elementary and middle school youth, aimed to improve bystander’s self-efficacy to intervene on behalf of the victim and reduce negative bystander behavior (e.g., passivity or support of bullying behavior). This program showed an effect in reducing both traditional and cyberbullying and depression and anxiety symptoms (Karna et al., 2011; Williford et al., 2012).

Study Objectives

While extant bullying prevention programs have contributed to positive gains for youth, less attention has been paid to the specific needs of middle school students impacted by cyberbullying. Middle school students are disproportionately impacted by cyberbullying (Hinduja & Patchin, 2021). They are in a developmental stage when they are still learning to interact safely and responsibly online, which may make them especially vulnerable to cyberbullying’s distinct influences on online communication (i.e., potential for harsh communication, misunderstanding, and wide-spread, public dissemination; Nesi et al., 2018), suggesting need for targeted prevention. This study was designed to enhance understanding of the needs of middle school students impacted by cyberbullying and identify opportunities for targeted prevention programming that promotes positive bystander behaviors. Toward these aims, we conducted a qualitative focus group study with middle school students to explore their experiences with cyberbullying, perspectives toward existing school-based cyberbullying prevention programming, and perceptions toward ways to promote positive bystander behaviors to inform future targeted cyberbullying prevention efforts.

Materials and Methods

Data collection occurred between October 2019 and January 2020. Appointments were conducted in-person at students’ middle schools. All participants received a $20 incentive. Purposive sampling focused on students within middle schools in the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania area. Sampling continued until saturation was reached. The study primary investigator sent letters to fifteen middle schools to describe the study. Administrators from three schools responded with interest, after which the research team scheduled appointments to conduct focus groups. Schools varied geographically within urban and suburban settings and were a combination of public and private schools. Students were approached by their school personnel about their interest in participating in a research study, who scheduled a mutually agreeable time for a focus group of interested students. Prior to the focus group, parents provided informed consent and youth provided assent. The informed consent process included discussion of anonymity and the need for confidentiality for the information shared during the focus groups. School personnel were excluded from the focus groups to facilitate open dialogue. Further, as a resource for students who reported personally being negatively impacted by cyberbullying during focus groups, we provided all students with an informational sheet on mental health support and crisis resources. This study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh IRB (STUDY19050147). Reporting of data collection and analytic methods follows the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (Tong, Sainsbury, & Craig, 2007).

Following consent, students participated in focus groups led by experienced facilitators (AR, MO, LN, & CB), who were all female researchers at the University of Pittsburgh with MDs or PhDs. Focus groups lasted approximately 90 minutes and were conducted using a semi-structured interview guide that included questions about how cyberbullying should be defined, the degree to which cyberbullying is a problem for middle school students, experiences with cyberbullying and its impact, perceptions toward reporting cyberbullying, and cyberbullying prevention programs and protocols within their school. Additionally, participants were asked to consider their preferences toward school-based programming that would support engagement in positive bystander behaviors. Before eliciting students’ perspectives, they were provided a description of bystander interventions. This included description of training on being an upstander, involving support in enacting positive bystander behaviors such as empathizing with the victim, offering support, and aiding report to a trusted adult. Students were asked their perspectives for potential modalities for programming, including through classroom discussion, school assemblies, and an online platform. Further, students were also asked to provide perspectives on engaging near-peers as mentors (e.g., high school or college students), who would facilitate discussion and learning around positive bystander behaviors.

Five out of six focus groups were recorded and transcribed verbatim. The recording for one focus group failed. Thorough field notes were drafted by the facilitator for that focus group (CB) and were reviewed by co-facilitators (AR and EM). A codebook was inductively developed based on the content from the interview script. Two qualitative analysts (CB & EM) independently coded all focus group transcripts using NVivo version 12, and the two coders met to fully adjudicate coding differences. Interrater reliability calculations indicated substantial agreement (kappa = 0.75 – 0.84) (McHugh, 2012). Coding definitions were reviewed for clarity after coding of the first two focus groups by the two qualitative analysts and senior author (AR), following which all transcripts were adjudicated to full agreement. The primary coder (CB) then used the completed coding to produce a thematic analysis of the interviews. Salient quotes were identified to illustrate the themes/findings. As described by Sandelowski (Sandelowski, 2000), we culled themes by logically organizing and describing the information presented in the focus groups in a way that best fit the data. Resulting themes were corroborated by the secondary coder (EM) and the other team members as a form of investigator triangulation.

While exploring differences in opinions of students across types of schools was outside of the scope of this study, unique perspectives were observed among students from public and private schools. As such, differences among public and private students were considered during analysis to provide additional context to themes identified across focus groups. Three focus groups took place at one private school, and three focus groups took place at two public schools.

Results

Forty-six middle school students participated in focus groups with between 7 and 10 students in each group. There were 13 males (30%) and 31 (70%) females. Their ages ranged from 11 to 14 years old (average age was 13). All participants were identified by personnel within their schools and were in 6th to 8th grade. Students were from two urban schools that each had approximately 36% racial and ethnic minority enrollment and one suburban school with 19% minority enrollment. Five themes were identified regarding the context for cyberbullying experiences and prevention programming within their schools. Two additional themes emerged regarding perspectives toward ways to improve and expand school-based cyberbullying prevention programming and promote positive bystander behaviors.

1. Students thought cyberbullying had unique aspects compared to traditional bullying, including less adult oversight.

Students defined cyberbullying as bullying in an online context, “basically like when they’re bullying over the internet and not directly saying it to your face.” Like traditional bullying, students described how cyberbullying was often repeated in nature and occurred at different levels of severity. However, they felt bullying that occurred online offered unique context. Participants felt it was easier to be mean online than it was in-person. They explained this was influenced by the ability to communicate anonymously without seeing facial cues or body language that could portray how the victim was feeling. Some thought cyberbullying could be more damaging than traditional bullying, because of the amount of information available online that could be used harmfully. For example, one student described how some people steal passwords to others’ social media accounts and add embarrassing or harmful comments. Some students also reflected on how parents or teachers knew much less about bullying that occurred online than at school. As one student commented, the presence of limited adult oversight made them feel like cyberbullying was often left unchecked:

“I think like online it’s probably easier to get away with because your parents don’t see it then whereas if you do it in-person someone’s gonna say something.”

2. Many students had personally experienced cyberbullying and thought it was an important problem for middle school students, although students in private school acknowledged being less personally affected than those in public school.

Across focus groups, students felt cyberbullying was a problem for middle school students, some of whom thought the problem was growing. Considering why this may be, they described how many middle school students newly attain smartphones/devices and are still learning about how to use them safely. As one student described:

“I think back then [elementary school] it wasn’t really a problem because all our parents were like, because mine was like, ‘You don’t need a phone. You don’t need to go on all that stuff.’ But now it’s just to the point where you’re having bullying at school and it just extends to online, and it just gets worse and worse.”

Public school students expressed that cyberbullying happened at their school and was problematic, whereas private school students felt cyberbullying was less of an issue for them. One student noted their exposure to cyberbullying was mostly outside of their community:

“We don’t have many issues I would say, but…most of us know people that go to other schools that we’ve heard stories of people having problems with other people online.”

Across focus groups, students made 40 references to witnessing cyberbullying, 24 references to being targeted by cyberbullying, and 3 references to engaging in cyberbullying. Experiences with being a victim ranged from negative comments related to physical appearance, posts that diminished others’ reputation, and being rejected from a peer group. While fewer students reported personal experiences engaging in cyberbullying, one described a time they unintentionally hurt someone who took offense to a joke they made. Many students acknowledged witnessing others being cyberbullied, more so than they experienced it themselves. When asked what they considered to be severe cyberbullying, they described attempts at digital harm like hacking or stealing private information and disparaging comments toward someone’s race, religion, or body image. Students within one focus group described how threats of suicide could be used as a severe form of cyberbullying. While they thought that online communication about suicide was sometimes intended seeking help or support, at times they felt the intent was to threaten suicide as a way of exerting influence on others:

“Like a person saying they were going to commit suicide if that person didn’t do something that they wanted to do, like drugs or drink, anything like that real.”

3. Students identified a variety of impacts of cyberbullying for victims and perpetrators and felt empathy for youth who were more vulnerable to cyberbullying.

Students were aware of consequences to victims’ mental health (i.e., lowered self-esteem, feeling down, or having suicidal thoughts) and social lives. As one student described, sometimes cyberbullying contributed to withdrawing from others or feeling trust among friends was broken:

“It could make you like lose trust in your friends, cause maybe your friends believe that too, so you could start like blocking yourself out from the rest of like your friend group or whoever you hang out with and kind of like push yourself into a corner.”

Students observed consequences for perpetrators of being removed from social media accounts or groups chats, or the potential for disciplinary action at school. One participant offered an example of a student in their school who made a racial slur and subsequently was “asked to leave,” referring to their school’s process for expelling someone. Students described how some youth may be more vulnerable to experiencing cyberbullying, such as those with a lower maturity level who may not take steps to defend themselves. Further, they felt a desire to change one’s reputation, challenging home environments, or life stress could contribute to students engaging in cyberbullying. As one student described:

“You don’t know what they’re going through. Like people can be getting like hurt by their parents or something. They could be like, they’re just like, someone could be dying in their family. Like you never know.”

4. Students considered talking with parents, same-age friends, and school personnel about cyberbullying with some hesitation and had most comfort with older friends or relatives.

When asked who students would reach out to about cyberbullying, most responded that they would talk with a parent (referenced 35 times). They agreed parents were trusted sources of support and understanding, some of whom sought parents for advice about reporting cyberbullying on social media. However, some students feared disclosing cyberbullying to a parent could result in restrictions to their social media use. Students were divided on their comfort level in talking with a friend. Students felt it would be helpful to talk with someone close to their age who could relate (referenced 18 times). Others worried friends would share their discussion with other peers without their permission.

Students’ comfort in talking with school personnel professionals varied, in part based on if cyberbullying pertained to school. While some trusted their teachers and administrators to help (referenced 7 times), others expressed concern (referenced 16 times), worrying they would break their confidentiality, not understand, take disciplinary action, or be unhelpful in their response. Comfort talking with school mental health professionals varied based on whether students had an established relationship with them. In one focus group, students who had a limited relationship with their school counselor felt it would be “kind of awkward if you’re forced to talk with them [about cyberbullying].” However, in another focus group in which students described knowing their guidance counselor, they said they trusted their counselor, because they “take everything serious no matter what it is” and “know how to handle the situation.”

By contrast, students who talked about cyberbullying with a high school or college-aged friend or relative (referenced 11 times) expressed being more comfortable talking with them than other sources of support. They felt youth in this age range could relate to their experience and be helpful. Several students cited examples of helpful guidance they received from a sibling or cousin about cyberbullying. One student described seeking support from her 18-year-old brother:

“My brother always writes me stuff about like, cause he’s learned and he’s like one time he gave me like these eight things to go off of and use. One of them was like…your friends might leave you but just remember that you have yourself and that’s what really counts… But like I always look back and it always does help me.”

The most common factors reported by middle school students that would influence their decision making about whether to reach out for help in response to cyberbullying included availability of someone that they trust (referenced 22 times), fear of rumors or being referred to as a “snitch” or a “tattletale” (referenced 20 times), concerns about confidentiality (referenced 17 times), and belief that they need help or support (referenced 17 times).

5. Students felt their school’s response to cyberbullying was useful in some contexts, albeit existing cyberbullying prevention programs were not always taken seriously.

When asked to describe when their school responded to cyberbullying, students perceived that their schools stepped in when cyberbullying involved the school, (e.g., took place in a group chat of students who mentioned the school by name) and when it was serious and overt in nature, whereas covert forms of cyberbullying were less frequently discussed. Students found their school’s response to cyberbullying helpful when the school took reports seriously and addressed their conversations with students calmly and rationally. Responses that seemed out of proportion for the situation or when inconsiderate of the context for what was happening were seen as unhelpful. One student described how teachers can respond without understanding the situation:

“But like they don’t, they’re not going to ask for context, they’re going to see the text and they’re going to go with what they saw or who it’s from.”

When asked about their school’s existing programs for cyberbullying, students reflected on how discussion of cyberbullying was incorporated into their curriculum and through school-wide prevention programs. Students found programming helpful when it created a comfortable environment for discussion that felt authentic and relatable. Students had experience with Rachel’s Challenges (a violence prevention program), which they found compelling because it centered the voice of a Columbine High School shooting survivor to consider how to make their school a safer place. They were also aware of Safe2Say (a Pennsylvania violence prevention program), which they thought was helpful because it offered an anonymous means to report cyberbullying. However, there were concerns that prevention programs were sometimes treated as a topic of jokes, which they felt could undermine their benefit. As one student described:

“Yeah, I feel upset sometimes because people make fun of those kind of things. Like, Safe2Say - people will take something like insignificant and then like joke around like what other people say.”

6. Students felt targeted prevention programming that involved near-peer mentors would be an acceptable way to learn how to respond to cyberbullying they experienced or witnessed.

When asked about perceptions toward mentors near to them in age, participants reflected such mentors would be ideally placed to offer feedback about cyberbullying, because they are mature and experienced with effective response. They posited that near-peer mentors would be relatable because they experienced similar trends in cyberbullying and social media use to what they have. When considering the age group ideally suited to act as mentors, students’ preferences varied between high school and college students. In several focus groups, students reflecting on the importance of mentors’ experience more so than their age:

“Maybe like a mix of both…like I would say I lean mostly to high schoolers or like freshmen or sophomores in college because I feel that even though high schoolers will be—will have—will be like experiencing it, I feel that college students have—they have experienced some of the worst stuff that happens because they’ve been in high school.”

Students from public schools reflected on how the severity of bullying could vary in different places and preferred mentors from within their school district or community, who they thought would have perspectives that felt relatable to their experiences. By contrast, private school students desired diverse perspectives through extending mentorship across communities. When asked about mentorship preferences within or outside their school, students from an urban private school described wanting inclusion from “not just like the couple little private schools around, you could [have a] couple with the public schools too.” They noted interest in hearing perspectives from a range of schools, large and small in size and from urban and rural areas.

7. Students thought combining school-based programming with an online platform that offered education and connection could be helpful, for students and parents alike.

When asked to consider modes for prevention programming, students noted value in discussing cyberbullying at school. Some thought role playing during school assemblies could be effective in communicating the seriousness of cyberbullying, if it were done in a way that met students’ comfort levels for talking in front of groups. They emphasized the importance of using scenarios about cyberbullying that felt authentic to middle school students, so the program is taken seriously, “not just some printed story, you can tell it’s fake…something relatable.”

Students agreed that an online platform would be a useful way to extend the content of school-based programming and could provide an added venue for connection among students and mentors to discuss and seek advice about cyberbullying they experienced or witnessed. They had a strong preference for communication on the platform to be anonymous to guard their confidentiality. Some students thought an online platform should also have resources for parents, to help parents understand social media use among middle school students, which would make it easier to talk with their parents about cyberbullying. As students in one focus group described:

Student 1: “There should be some information … that kind of makes parents feel safer about letting their kid use social media.”

Student 2: “An organization that’s giving the pros and cons, why or why not you should let your child, what’s the safest app to let them use if you want to try social media.”

Discussion

Thematic analysis of focus groups with middle school students shed light on their cyberbullying experiences and suggested opportunities for targeted prevention. Students viewed cyberbullying as a problem for young people their age who are newly learning to use phones and other devices safely and felt it could have serious consequences. While students thought it could be beneficial to confide in parents or school personnel after cyberbullying, they also acknowledged barriers that contributed to hesitation in reporting and desired opportunities to report cyberbullying in a manner that protected their privacy. Students acknowledged comfort in talking with an older sibling, family member, or friend, who they felt would understand their experience while still having enough maturity to offer helpful advice. They valued existing prevention programming in their schools when cyberbullying was taken seriously, and at the same time recognized limitations when programming felt inauthentic. Students recognized potential benefits of incorporating near-peer mentors, who they felt would be relatable and helpful, within an intervention that promoted positive bystander behavior. They thought combining school-based programming with an online educational platform could extend opportunities for connection among students and mentors while also offering beneficial information for students and parents in preventing and responding to cyberbullying.

Implications for School Mental Health Professionals Engaged in Cyberbullying Prevention

A range of school mental health professional organizations have released policy and position statements recognizing the importance and ethical priority of cyberbullying prevention. The National Association of Social Work (NASW; Issurdatt, 2010) suggests school social workers both engage in direct services for bullied youth within schools and advocate for change within institutions to combat bullying’s negative effects. The American School Counselor Association (ASCA; ASCA 2012, 2014) calls counselors to be change agents in developing and delivering bullying prevention programming within small groups and classrooms and to individual students. The National Association of School Psychologists (NASP; NASP, 2012) calls for school psychologists to take a leadership role in developing and implementing universal and targeted prevention efforts. NASP has pointed to the importance of creating school cultures where students feel safe and that they belong, which importantly includes empowering students who witness bullying to stop harassment and intimidation. They suggest focus on bystanders to promote safe schools and engaging youth to be a part of the solution, an approach that can foster ownership and relevancy and give youth a voice (Cassidy, Faucher, & Jackson, 2013).

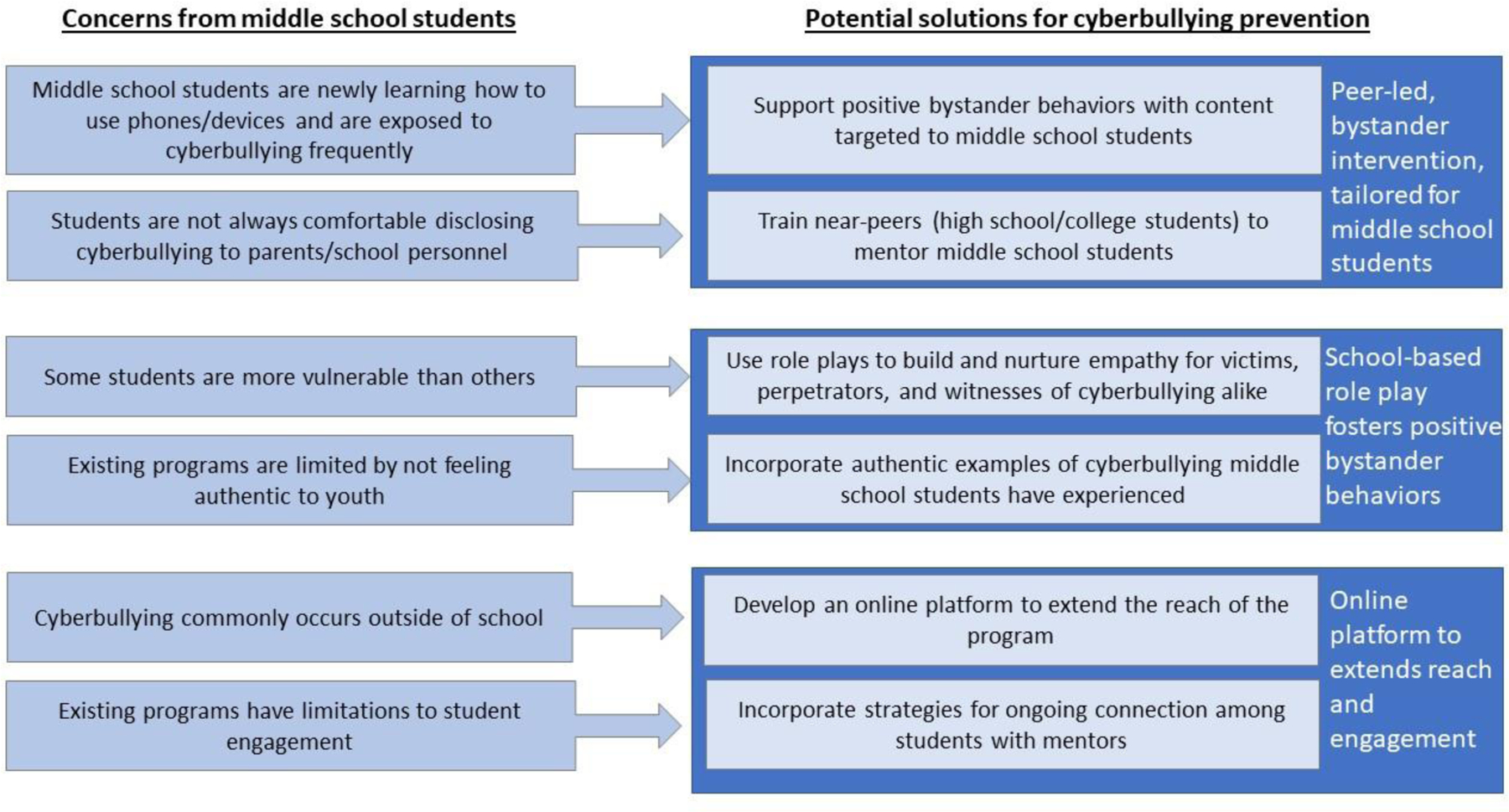

Data from these focus groups contributes to knowledge for how school mental health professionals can involve and empower students to engage in cyberbullying prevention programming using strategies that are desirable to middle school students. Specifically, our data suggests considerations for the delivery, scope, and relatability of prevention programming to ideally meet middle school students’ needs. Figure 1 depicts the needs identified by middle school students and corresponding considerations for prevention programming.

Figure 1.

Summary of Focus Groups Findings and Implications for Targeted Cyberbullying Prevention

Delivery.

Students in our focus groups felt programming at their schools was helpful but not always delivered in a way they found to be authentic or impactful, which in some cases contributed to them not taking it seriously. Authentic programming was exemplified through the inclusion of real-life examples of cyberbullying and young people who were passionate toward a cause. Inauthentic programming was exemplified by omission of youth voice and not understanding and accurately reflecting students’ experiences. School mental health professionals have an important role in advocating for curriculum to be delivered in a way that effectively reaches students and inspires buy in to the importance of prevention. Research supports involving and empowering students is critical to students’ engagement (Cassidy et al., 2013). Likewise, students recommended identifying student volunteers who were emboldened and passionate to lead assemblies and classroom programs, as well as using student-led role plays as a strategy for experiential learning about positive bystander behaviors.

Scope.

Prevention programming within participants’ schools predominantly focused on overt cyberbullying, whereas covert examples of cyberbullying (e.g., social rejection and exclusion) were often not addressed. Notably, both overt and covert aggression can contribute to poor mental health outcomes (Prinstein, Boergers, & Vernberg, 2001). Further, during early adolescence, a time when youth are growing in their socioemotional abilities and especially vulnerable to peer influence, covert aggression is common (Casas & Bower, 2018). This suggests need to aid middle school students in recognizing, understanding, and responding to not only overt but also covert forms of cyberbullying.

Furthermore, students desired the scope of school-based programming to be expanded to include an online educational platform that offered opportunity for connection among students and mentors. This suggestion is consistent with a growing body of literature citing benefits of incorporating technology into cyberbullying prevention. In fact, a recent meta-analysis (Chen et al., 2022) found that digital health interventions showed significant reductions in cyberbullying with critical components of effective interventions including training and skill-building to support positive bystander behaviors. An online platform for students and mentors could also extend support to students outside of the classroom, where much of cyberbullying occurs (Kowalski & Limber, 2007). Nonetheless, incorporating such an approach requires careful consideration of ethical and legal complexities associated with schools’ involvement with cyberbullying that may occur off of school grounds (Hinduja & Patchin, 2011).

Relatability.

Existing programs primarily rely on students to report cyberbullying, despite data indicating a majority of students do not report cyberbullying to a trusted adult (NCES, 2019). These focus groups echoed these findings, indicating a variety of barriers to reporting cyberbullying to parents, school personnel, and even to their friends. A key aspect that motivates adolescents to disclose cyberbullying is the belief that the person to whom they intend to report cyberbullying will be understanding and helpful. Incorporating best practices for nurturing positive school climates and educating parents to effectively and supportively respond to cyberbullying (NASM, 2016) could foster students’ openness in disclosure. Educational resources, such as the Cyberbullying Research Center (www.cyberbullying.org) and Common Sense Media (www.commonsensemedia.org), could aid these pursuits through offering information on social media use and cyberbullying among youth and age-appropriate guidance for monitoring. Utilizing near-peers as mentors could also offer benefit for providing a comfortable space for middle school students to discuss and seek guidance about cyberbullying. Importantly such approaches require training for peer mentors, including on confidentiality and empathic communication, and availability of professional support for situations that rise beyond a level student mentors can address on their own (King & Fazel, 2021).

Limitations.

This study was limited by the use of a purposive sample within the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania area, which prohibits generalizability to a larger population or to schools within other geographic regions. While differences among private- and public-school students were noted, only one private school was included within this sample in which three focus groups were conducted. This may bias findings, which may not be representative of students’ experiences within private middle schools in general. Further, few students in focus groups reported cyberbullying others, which may have been due to discomfort disclosing this in a group context. Even though youth were assured of the confidentiality of focus groups were done not in the presence of school personnel, youth may still have been concerned about disciplinary action. Individual interviews may have been more likely to elicit more personal experiences. We chose focus groups to encourage group discussion and consensus, particularly regarding recommendations for prevention.

Conclusions.

Our findings provide valuable insights toward middle school students’ experiences with cyberbullying and existing school-based cyberbullying prevention programs and policies. These data suggest need for school mental health professionals to recognize the unique problem of cyberbullying among middle school students and to involve students in the solution through targeted, youth engaged and empowered prevention programming.

Acknowledgements.

The authors are grateful to the students and schools who engaged with this study, without whom this work would not have been possible.

Declaration of Interest Statement.

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare. This work was supported by AT&T and the National Institute of Mental Health under Grants T32 MH189051 and K23 MH111922.

References

- Agatston P, Kowalski R, & Limber S (2012). Youth views on cyberbullying. In Patchin J & Hinduja S (Eds.), Cyberbullying Prevention and Response: Expert Perspectives (pp. 57–71). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Allison K, & Bussey K (2016). Cyber-bystanding in context: a review of the literature on witnesses’ responses to cyberbullying. Children and Youth Services Review, 65, 183–194, doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.03.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ang R (2015). Adolescent cyberbullying: a review of characteristics, prevention and intervention strategies. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 25, 35–42, doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2015.07.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ASCA. (2012). ASCA National Model: A Framework for School Counseling Programs (3rd Edition ed.). Alexandria, VA: American School Counselor Association. [Google Scholar]

- ASCA. (2014). ASCA Mindsets & Behaviors for Student Success: K-12 College- and Career-readiness Standards for Every Student. Alexandria, VA: American School Counseling Association. [Google Scholar]

- ASCA. (2016). ASCA Ethical Standards for School Counselors. Alexandra, VA: American School Counselors Association. [Google Scholar]

- Banyard V, Moynihan M, & Plante E (2007). Sexual violence prevention through bystander education: an experimental evaluation. Journal of Community Psychology, 35, 463–481, doi: 10.1002/jcop.20159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bastiaensens H, Vandebosch K, Poels K, Van Cleemput A, DeSmet I, & De Bourdeaudhuij I (2014). Cyberbullying on social network sites: an experimental study into bystanders’ behavioural intentions to help the victim or reinforce the bully. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 259–271, doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown E, Low S, Smith B, & Haggerty K (2011). Outcomes from a school randomized controlled trial of steps to respect: a bullying prevention program. School Psychology Review, 40(3). [Google Scholar]

- Cantone E, Piras A, Vellante M, Preti A, Danielsdottir S, D’Aloja E, … Bhugra D (2015). Interventions on bullying and cyberbullying in schools: a systematic review. Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental Health, 11, 58–76, doi: 10.1080/02796015.2011.12087707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casas J, & Bower A (2018). Developmental manifestiations of relational aggression. In Coyne S & Ostrov J (Eds.), The Development of Relational Aggression. New York, NY: Oxford Unviersity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy W, Faucher C, & Jackson M (2013). Cyberbullying among youth: a comprehensive review of current international research and its implications and application to policy and practice. School Psychology International, 34(6), 575–612, doi: 10.1177/0143034313479697. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Chan KL, Guo S, Chen M, Lo CK, & Ip P (2022). Effectiveness of digital health interventions in reducing bullying and cyberbullying: a meta-analysis. Trauma Violence and Abuse, 15248380221082090, doi: 10.1177/15248380221082090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm J (2014). Review of the status of cyberbullying and cyberbullying prevention. Journal of Information Systems Education, 25(1), 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Common Sense Media (2020). What is cyberbullying? Retrieved from https://www.commonsensemedia.org/articles/what-is-cyberbullying.

- Desmet A, Bastiaensens S, Van Cleemput K, Poels K, Vandebosch H, & De Bourdeaudhuij I (2012). Mobilizing bystanders of cyberbullying: an exploratory study into behavioural determinants of defending the victim. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 181, 58–63, doi: 10.3233/978-1-61499-121-2-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmet A, Bastiansens S, Van Cleemput K, Poels K, Vandebosch H, Cardon G, & De Bourdeaudhuij I (2016). Deciding whether to look after them, to like it, or leave it: a multidimensional analysis of predictors of positive and negative bystander behavior in cyberbullying among adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 57, 398–415, doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.12.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeSmet A, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Walrave M, & Vandebosch H (2019). Associations between bystander reactions to cyberbullying and victims’ emotional experiences and mental health. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 22(10), 648–656, doi: 10.1089/cyber.2019.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Destin M, Castillo C, & Meissner L (2018). A field experiment demonstrates near peer mentorship as an effective support for student persistence. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 40(5), 269–278, doi: 10.1080/01973533.2018.1485101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon K, & Bushman B (2015). Unresponsive or un-noticed?: cyberbystander intervention in an experimental cyberbullying context. Computers in Human Behavior, 45, 144–150, doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte C, Pittman S, Thorsen M, Cunningham R, & Ranney M (2018). Correlation of minority status, cyberbullying, and mental health: a cross-sectional study of 1031 adolescents. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 11, 39–48, doi: 10.1007/s40653-018-0201-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freis S, & Gurung R (2013). A Facebook analysis of helping behavior in online bullying. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 2(1), 11–19, doi: 10.1037/a0030239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frey K, Kirschstein M, Eddstrom L, & Snell J (2009). Observed reductions on school bullying, nonbullying aggression, and destructive bystander behavior: a longitudinal evaluation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101, 466–481, doi: 10.1037/a0013839. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffney H, Farrington D, Espelage D, & Ttofi M (2019). Are cyberbullying intervention and prevention programs effective? a systematic and meta-analytic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 45, 134–153, doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2018.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffney H, Ttofi MM, & Farrington DP (2021). What works in anti-bullying programs? Analysis of effective intervention components. Journal of School Psychology, 85, 37–56, doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2020.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Melgar A, & Meyers N (2020). STEM near peer mentoring for secondary school students: a case study of university mentors’ experiences with online mentoring. Journal of STEM Education Research, 3, 19–42, doi: 10.1007/s41979-019-00024-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haft SL, Chen T, Leblanc C, Tencza F, & Hoeft F (2019). Impact of mentoring on socio-emotional and mental health outcomes of youth with learning disabilities and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 24(4), 318–328, doi: 10.1111/camh.12331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins D, Pepler D, & Craig W (2001). Naturalistic observations of peer interventions in bullying. Social Development, 10, 512–527, doi: 10.1111/camh.12331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hinduja S (2021). Cyberbullying in 2021 by age, gender, sexual orientaiton, and race. Retrieved from https://cyberbullying.org/cyberbullying-statistics-age-gender-sexual-orientation-race.

- Hinduja S, & Patchin JW (2011). Cyberbullying: a review of the legal issues facing educators. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 55(2), 71–78, doi: 10.1080/1045988X.2011.539433. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holfeld B, & Mishna F (2018). Longitudinal associations in youth involvement as victimized, bullying, or witnessing cyberbullying. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networks, 21(4), 234–239, doi: 10.1089/cyber.2017.0369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issurdatt S (2010). A shift in approach: addressing bullying in schools. School Social Work: Practice Update. Washington DC: National Association of Social Workers. [Google Scholar]

- Karna A, voeten M, Little T, Poskiparta E, Alanen E, & Salmivalli C (2011). Going to scale: a nonrandomized nationwide trial of the KiVa antibullying program for Grades 1–9. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(6), 796–805, doi: 10.1037/a0025740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Boyle MH, & Georgiades K (2018). Cyberbullying victimization and its association with health across the life course: a Canadian population study. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 108(5–6), e468–e474, doi: 10.17269/cjph.108.6175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King T, & Fazel M (2021). Examining the mental health outcomes of school-based peer-led interventions on young people: a scoping review of range and a systematic review of effectiveness. PLoS One, 16(4), e0249553, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0249553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski R, Limber S, & Agatston P (2012). Cyberbullying: Bullying in the Digital Age, 2nd Edition. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski RM, Giumetti GW, Schroeder AN, & Lattanner MR (2014). Bullying in the digital age: a critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychological Bulletin, 140(4), 1073–1137, doi: 10.1037/a0035618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski RM, & Limber SP (2007). Electronic bullying among middle school students. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41(6 Suppl 1), S22–30, doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan I, Dickson K, Richardson M, MacDowall W, Burchett H, Stansfield C, … Thomas J(2020). Cyberbullying and children and young people’s mental health: a systematic map of systematic reviews. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 23(2), 72–82, doi: 10.1089/cyber.2019.0370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart A, Madden M, Smith A, Purcell K, Zickuhr K, & Rainie L (2011). Teens, Kindness and Cruelty on Social Network Sites. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh M (2012). Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica, 22(3), 276–282, doi: 10.11613/BM.2012.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menesini E, & Nocentini A (2012). Peer education intervention: face-to-face versus online. In Costabile A & Spears B (Eds.), The Impact of Technology on Relationships in Educational Settings (pp. 139–150). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- National Assocition of School Psychologists. (2012). NASP position statement on bullying prevention and intervention in schools. Retrieved from https://njbullying.org/documents/NASPBullyingStatementAdoptedFeb2012.pdf.

- National Academies of Sciences & Medicine. (2016). Preventing Bullying Through Science, Policy, and Practice. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Educational Statistics. (2019). Student Reports of Bullying: Results from the 2017 School Crime Supplement to the National Crime Victimization Survey. (NCES 2019–054). Washington DC [Google Scholar]

- Nesi J, Burke TA, Bettis AH, Kudinova AY, Thompson EC, MacPherson HA, … Liu RT (2021). Social media use and self-injurious thoughts and behaviors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 87, 102038, doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesi J, Choukas-Bradley S, & Prinstein MJ (2018). Transformation of adolescent peer relations in the social media context: part 2-application to peer group processes and future directions for research. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 21(3), 295–319, doi: 10.1007/s10567-018-0262-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D, Limber S, & Breivik K (2019). Addressing specific forms of bullying: a large-scale evaluation of the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program. Interntional Journal of Bullying Prevention, 1, 70–84, doi: 10.1007/s42380-019-00009-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega R, Elipe P, Mora-Merchan J, Calmaestra J, & Vega E (2009). The emotional impact on victims of traditional and cyberbullying. Journal of Psychology, 217(4), 197–204, doi: 10.1027/0044-3409.217.4.197. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patchin J (2021). Bullying during the COVID-19 pandemic. Retrieved from https://cyberbullying.org/bullying-during-the-covid-19-pandemic

- Polanin J, Espelage D, & Pigott T (2012). A meta-analysis of school-based bullying prevention programs’ effects on bystander intervention behavior. School Psychology Review, 41(1), 47–65, doi: 10.1080/02796015.2012.12087375. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Boergers J, & Vernberg EM (2001). Overt and relational aggression in adolescents: social-psychological adjustment of aggressors and victims. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 30(4), 479–491, doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3004_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmivalli C (2010). Bullying and the peer group: a review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15(2), 112–120, doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2009.08.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M (2000). Focus on research methods: whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing and Health, 23, 334–340, doi: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shultz E, Heilman R, & Hart K (2014). Cyber-bullying: An exploration of bystander behavior and motivation. Cyberpsychology, 8(4), 2014, doi: 10.5817/CP2014-4-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, & Craig J (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Internatinoal Journal of Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357, doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torgal C, Espelage DL, Polanin JR, Ingram KM, Robinson LE, El Sheikh AJ, & Valido A (2021). A meta-analysis of school-based cyberbullying prevention programs’ impact on cyber-bystander behavior. School Psychology Review, 1–15, doi: 10.1080/2372966X.2021.1913037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ttofi M, & Farrington D (2011). Effectiveness of school-based programs to reduce bullying: a systematic and meta-analytic review. Journal of Experimental Criminiology, 7(1), 27–56, doi: 10.1007/s11292-010-9109-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ttofi MM, & Farrington DP (2011). Effectiveness of school-based programs to reduce bullying: a systematic and meta-analytic review. Journal of Experimental Criminiology, 7, 27–56, doi: 10.1007/s11292-010-9109-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tural Hesapcioglu S, & Ercan F (2017). Traditional and cyberbullying co-occurrence and its relationship to psychiatric symptoms. Pediatrics International, 59(1), 16–22, doi: 10.1111/ped.13067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tynes BM, English D, Toro JD, Smith NA, Lozada FT, Williams DR. (2020) Trajectories of Online Racial Discrimination and Psychological Functioning Among African American and Latino Adolescents. Child Development, 91(5), 1577–1593. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williford A, Boulton A, Noland B, Little T, Karna A, & Salmivalli C (2012). Effects of the KiVa anti-bullying program on adolescents’ depression, anxiety, and perception of peers. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40, 289–300, doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9551-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zambuto V, Palladino BE, Nocentini A, & Menesini E (2020). Voluntary vs nominated peer educators: a randomized trial within the NoTrap! anti-bullying program. Prevention Science, 21(5), 639–649, doi: 10.1007/s11121-020-01108-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]