Abstract

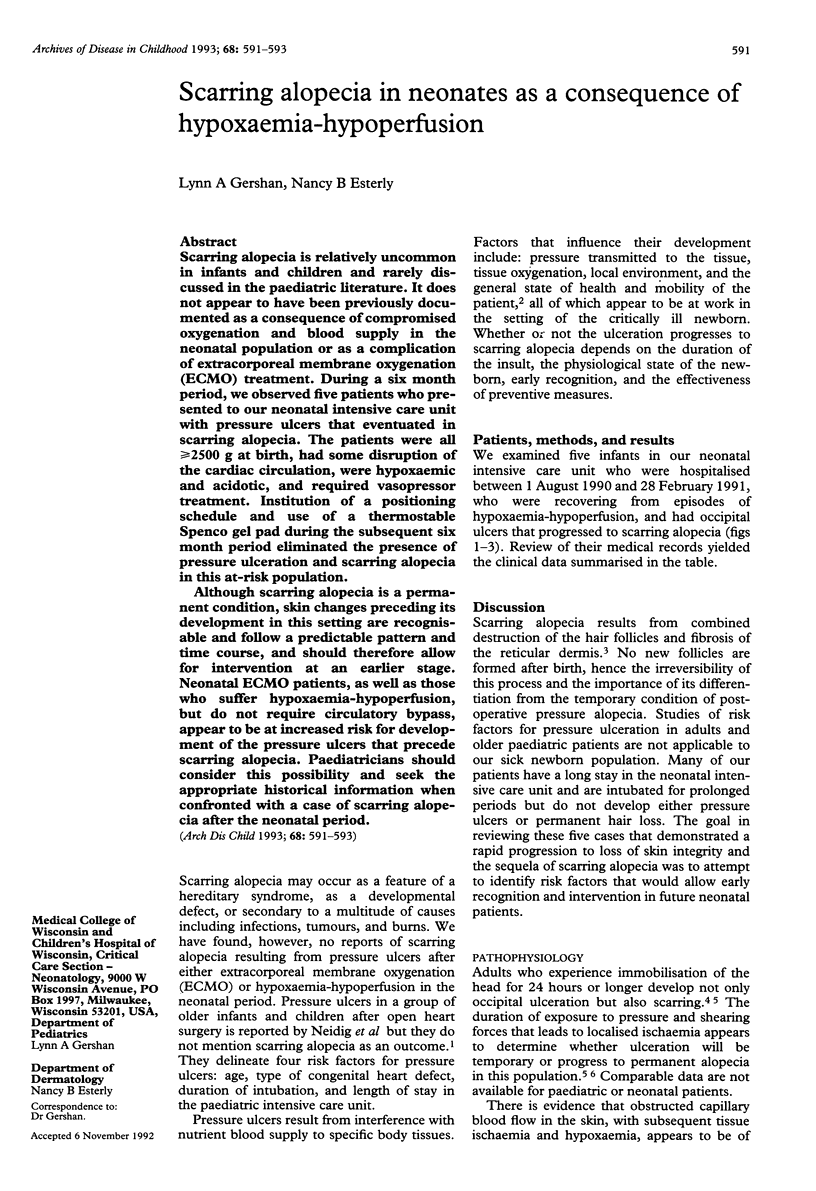

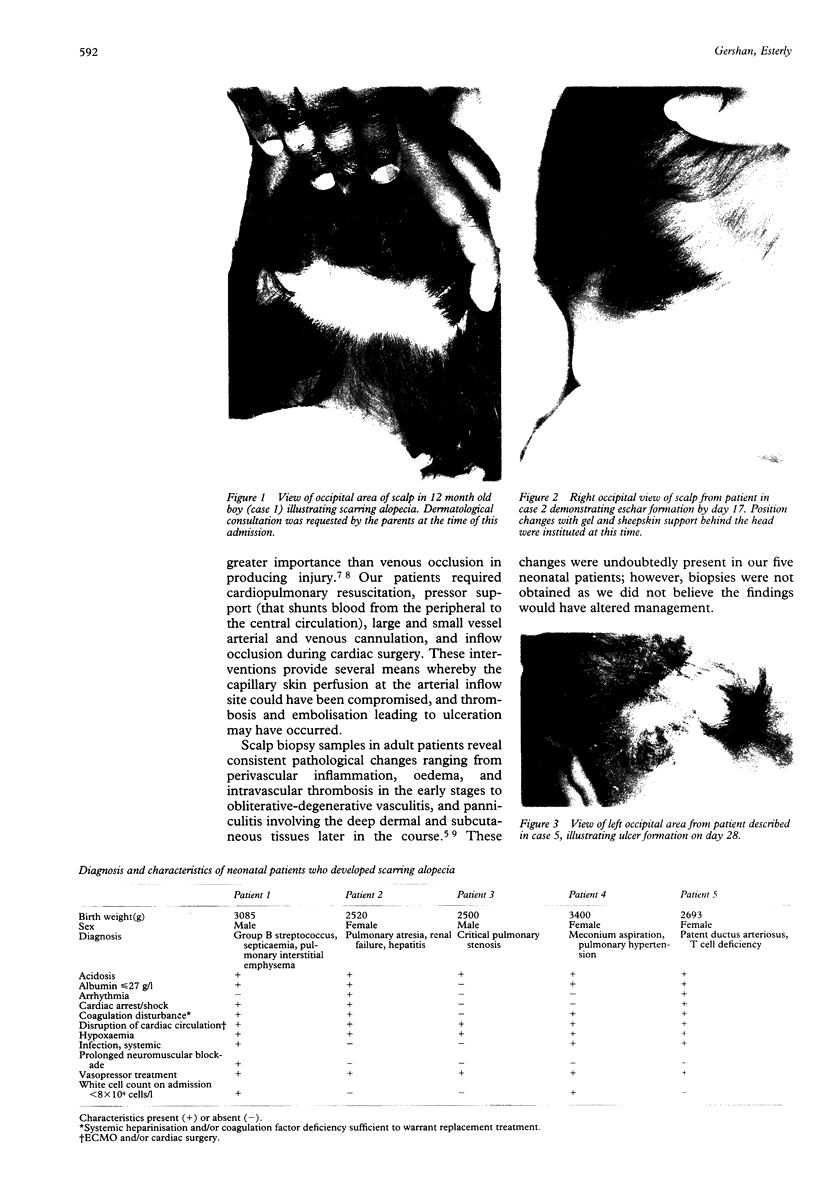

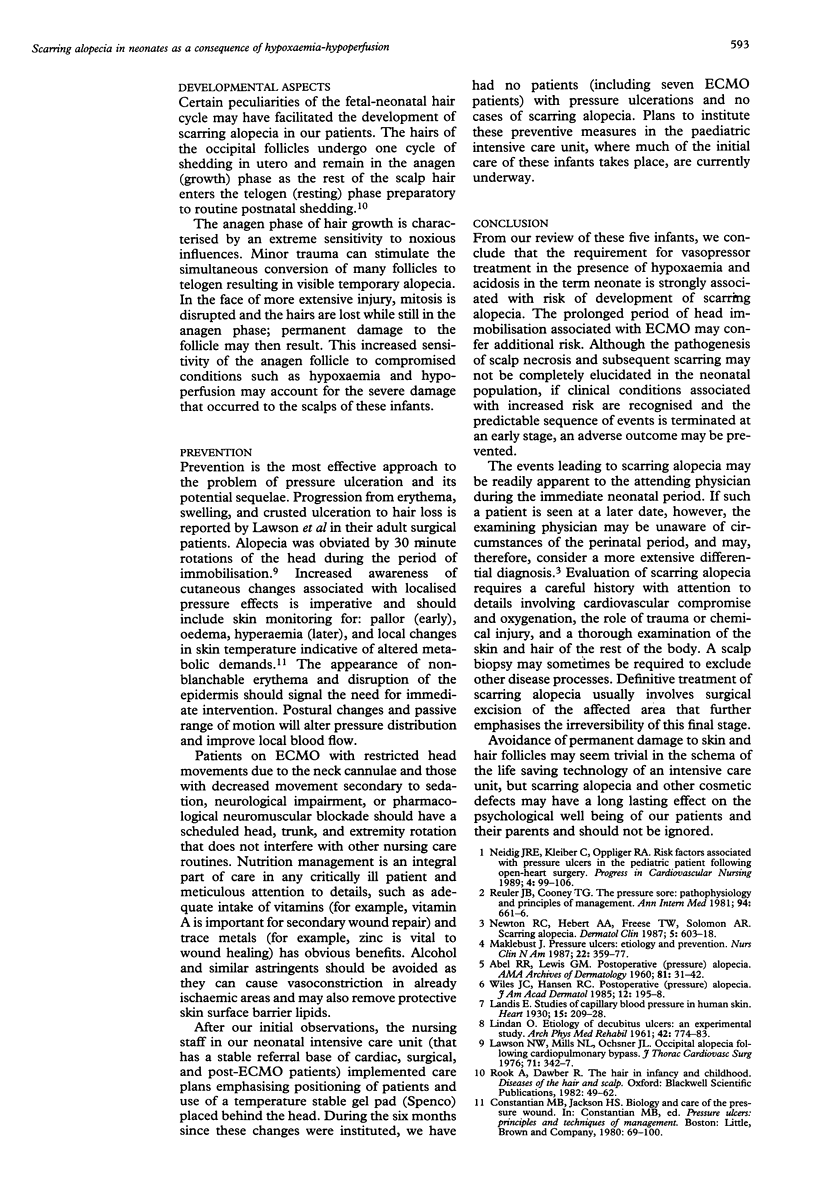

Scarring alopecia is relatively uncommon in infants and children and rarely discussed in the paediatric literature. It does not appear to have been previously documented as a consequence of compromised oxygenation and blood supply in the neonatal population or as a complication of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) treatment. During a six month period, we observed five patients who presented to our neonatal intensive care unit with pressure ulcers that eventuated in scarring alopecia. The patients were all > or = 2500 g at birth, had some disruption of the cardiac circulation, were hypoxaemic and acidotic, and required vasopressor treatment. Institution of a positioning schedule and use of a thermostable Spenco gel pad during the subsequent six month period eliminated the presence of pressure ulceration and scarring alopecia in this at-risk population. Although scarring alopecia is a permanent condition, skin changes preceding its development in this setting are recognisable and follow a predictable pattern and time course, and should therefore allow for intervention at an earlier stage. Neonatal ECMO patients, as well as those who suffer hypoxaemia-hypoperfusion, but do not require circulatory bypass, appear to be at increased risk for development of the pressure ulcers that precede scarring alopecia. Paediatricians should consider this possibility and seek the appropriate historical information when confronted with a case of scarring alopecia after the neonatal period.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- ABEL R. R., LEWIS G. M. Postoperative (pressure) alopecia. Arch Dermatol. 1960 Jan;81:34–42. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1960.03730010038004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINDAN O. Etiology of decubitus ulcers: an experimental study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1961 Nov;42:774–783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lwason N. W., Mills N. L., Ochsner J. L. Occipital alopecia following cardiopulmonary bypass. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1976 Mar;71(3):342–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maklebust J. Pressure ulcers: etiology and prevention. Nurs Clin North Am. 1987 Jun;22(2):359–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neidig J. R., Kleiber C., Oppliger R. A. Risk factors associated with pressure ulcers in the pediatric patient following open--heart surgery. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. 1989 Jul-Sep;4(3):99–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton R. C., Hebert A. A., Freese T. W., Solomon A. R. Scarring alopecia. Dermatol Clin. 1987 Jul;5(3):603–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuler J. B., Cooney T. G. The pressure sore: pathophysiology and principles of management. Ann Intern Med. 1981 May;94(5):661–666. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-94-5-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiles J. C., Hansen R. C. Postoperative (pressure) alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985 Jan;12(1 Pt 2):195–198. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(85)80016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]