Abstract

Objective:

The Prevention of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (PLUS) research consortium launched the RISE FOR HEALTH (RISE) national study of women’s bladder health which includes annual surveys and an in-person visit. For the in-person exam, a standardized, replicable approach to conducting a pelvic muscle (PM) assessment was necessary. The process used to develop the training, the products, and group testing results from the education and training are described.

Methods:

A comprehensive pelvic muscle assessment (CPMA) program was informed by literature view and expert opinion. Training materials were prepared for use on an electronicLearning (e-Learning) platform. An in-person hands-on simulation and certification session was then designed. It included a performance checklist assessment for use by Clinical Trainers, who in collaboration with a gynecology teaching assistant, provided an audit and feedback process to determine Trainee competency.

Results:

Five discrete components for CPMA training were developed as e-Learning modules. These were: (1) overview of all the clinical measures and PM anatomy and examination assessments, (2) visual assessment for pronounced pelvic organ prolapse, (3) palpatory assessment of the pubovisceral muscle to estimate muscle integrity, (4) digital vaginal assessment to estimate strength, duration, symmetry during PM contraction, and (5) pressure palpation of both myofascial structures and PMs to assess for self-report of pain. Seventeen Trainees completed the full CPMA training, all successfully meeting the a priori certification required pass rate of 85% on checklist assessment.

Conclusions:

The RISE CPMA training program was successfully conducted to assure standardization of the PM assessment across the PLUS multicenter research sites. This approach can be used by researchers and healthcare professionals who desire a standardized approach to assess competency when performing this CPMA in the clinical or research setting.

Keywords: comprehensive pelvic muscle assessment, pelvic examination, pelvic floor myofascial pain, pelvic muscle strength, pelvic organ prolapse, pubovisceral (pubococcygeus) muscle, women’s health

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Over the last decade, research has revealed new, expanded knowledge regarding pelvic muscle (PM) complexity,1 anatomic specificity, physiologic functioning, and potential for specific muscle injury2 (e.g., tears) or pain3 (e.g., myofascial). Improved imaging techniques have refined the assessment and identification of the range of PM changes, injuries, and recovery associated with life course events (e.g., childbirth).4–8 There remains a need to estimate PM health (optimal to poor) using clinical examination that draws on this new knowledge to support ongoing research and advance clinical care. However, standardization of PM assessment including training materials and quality control is lacking.

The Prevention of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (PLUS) research consortium is comprised of eight clinical centers and a scientific and data coordinating center focused on advancing science to understand bladder health (BH) and prevent lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in adolescent and adult women.9 The PLUS consortium launched the RISE FOR HEALTH (RISE) national study of BH which includes annual surveys and an in-person visit.10

During RISE study development, the need arose for a process to clearly identify and prioritize which PMs to assess (e.g. levator ani [LA] consisting of the pubovisceral [PV; pubococcygeus], puborectalis, and the iliococcygeus and the obturator internus [OI] muscles)1,11 in the in-person visit and how to standardize a replicable training approach to PM assessment. Hence, the PLUS research consortium was motivated to develop an overall, standardized, replicable clinician training program for comprehensive pelvic muscle assessment (CPMA). We describe our process, products (e.g., electronic-Learning [e-Learning] modules), and group testing results from the education and training methods developed and used by Clinical Trainers in the PLUS RISE CPMA program.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

The PLUS research consortium was established to create the evidence base for the promotion of BH and prevention of LUTS by using a transdisciplinary approach that integrates discipline-specific perspectives and extends this knowledge to generate a fundamentally new aspect of scientific inquiry.9 The team of PLUS investigators (n = 22) spans a range of perspectives and areas of expertise in the healthcare of adolescent and adult women. The research protocol for the PM assessment was developed by PLUS investigators, including physical medicine and rehabilitation physicians, urologists, and urogynecologists, nurse practitioner continence specialists, nurse-midwife, primary healthcare providers, geriatricians, and epidemiologists. The steps of the planning process and launch of the training are described.

2.1 |. Planning Task 1: Literature review

The team’s first task was to conduct a literature search for the most current understanding and knowledge regarding the following:

PMs anatomical detail and complexity,

the function of discrete components,

evidence on muscle injury type and prevalence, and

evidence of muscle and myofascial pain.

Once informed by the literature, the group used consensus to identify as comprehensively as practical, the PM examination components deemed most important for the RISE study (Table 1) and to develop two case report forms: (1) for compiling data from the PM assessment, and (2) for providing detailed instructions on the PM assessment procedure itself (available in Supporting Information: Materials).

TABLE 1.

Components of RISE pelvic assessment

| Exam component | Assessment approach | Comment/rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Evaluation for prolapse and incontinence | Visual inspection of the presence of prolapse protruding beyond the introitus at rest and/or with Valsalva. | Damage to the levator ani musculature and ligamentous support of the pelvic organs may result in vaginal prolapse.12 |

| Pubovisceral (PV) muscle integrity. Note: PV nomenclature aligns with the muscle naming convention as opposed to the alternative name pubococcygeus. Muscle “origin” denotes attachment at an unmoving anchoring site and muscle “insertion” reflects attachment at a site that responds to muscle contraction with movement. |

Palpatory assessment will estimate the extent of the PV muscle body integrity where it passes the vaginal sidewall bilaterally.1,13–16 The degree of detachment (tear) for the origin of the pubic bone can vary from none to complete loss on either side of the bilateral muscle structure. |

Prevalence of PV muscle tear ranges from 13% to 36% of women who have had a vaginal delivery with a higher prevalence associated with older maternal age and obstetric variables indicative of a more complex vaginal birth.5–8,17 A PV muscle tear has been identified as a risk factor for two important pelvic floor disorders: pelvic organ prolapse and possibly stress urinary incontinence.5,6 |

| LA muscle strength and endurance | Transvaginal digital palpation is used to assess the PMs and surrounding areas during contraction to determine the duration and symmetry of muscle contractions. | The recommended position of the examining digit(s) is to place the palmar surface of the examining finger on the LA.11,18–22 Pressure or stretch is applied perpendicular to the muscle fibers to assess tone. A contraction is felt as a tightening, lifting, and squeezing action under the examining finger as per the modified Oxford scale. |

| Pelvic floor myofascial pain with palpation | Palpation to determine presence of obturator internus (OI) and LA myofascial pain with palpation. Myofascial pain is characterized by the presence of trigger points or tenderness on a scale of 0 to 10 with palpation of the OI and LA muscles bilaterally.3,23 |

Pelvic floor myofascial painmay occur in conjunction with, or as sequelae of disease of the urinary, genital or musculoskeletal systems, or it may arise independently and has been observed in patients with LUTS and pelvic floor dysfunction.24,28 |

Abbreviation: LA, levator ani; PM, pelvic muscle; RISE, RISE FOR HEALTH.

2.2 |. Planning Task 2: e-Learning module development

A content lead for each of the four exam components was responsible for gathering any additional required materials (e.g., figures, diagrams, videos, and references) and drafting an e-Learning module with a voice-over presentation. An e-Learning platform was selected to accommodate investigators and research staff from the eight sites across the United States. Each module was determined as complete only after initial review and discussion with the entire team, with iterative improvements and a final team review for establishing consensus regarding module accuracy and completeness. All modules were designed for self-administration using a personal computer.

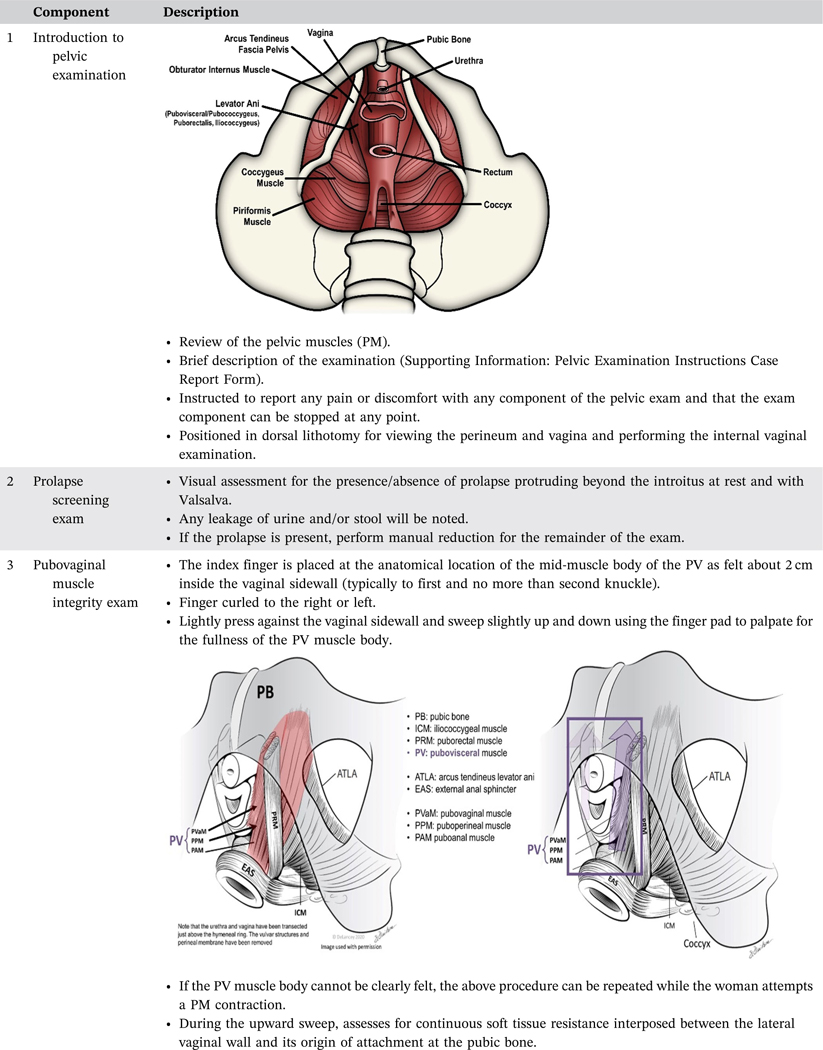

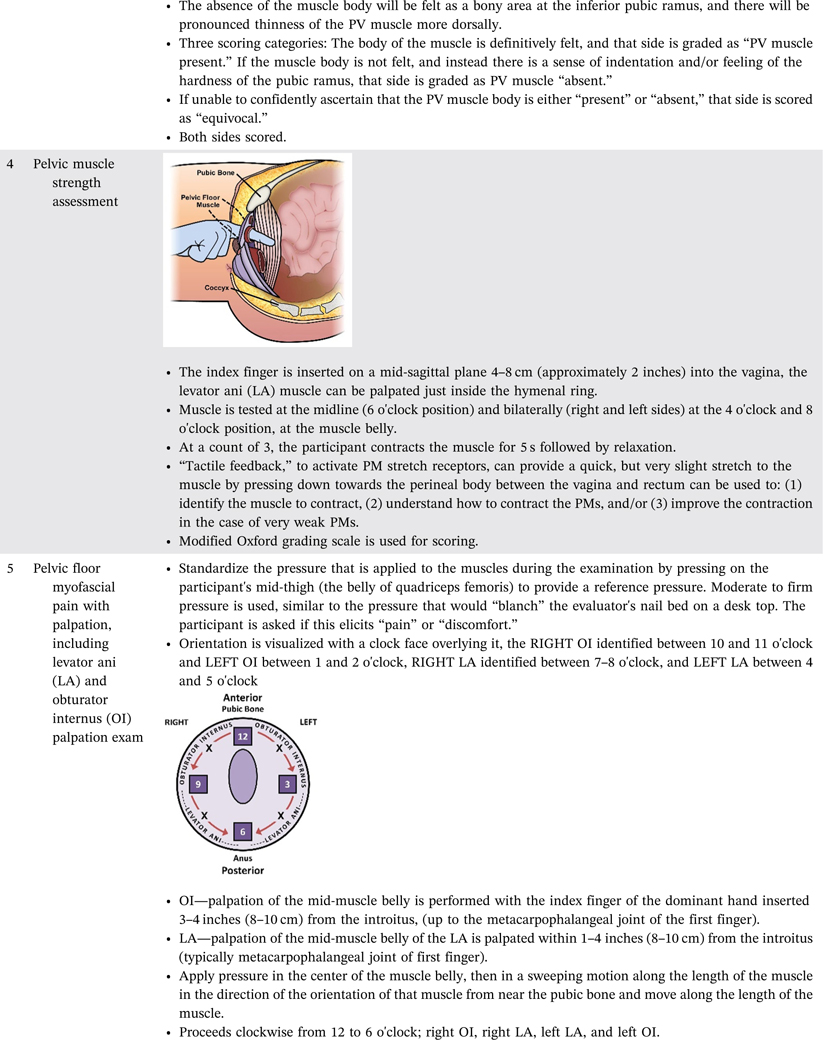

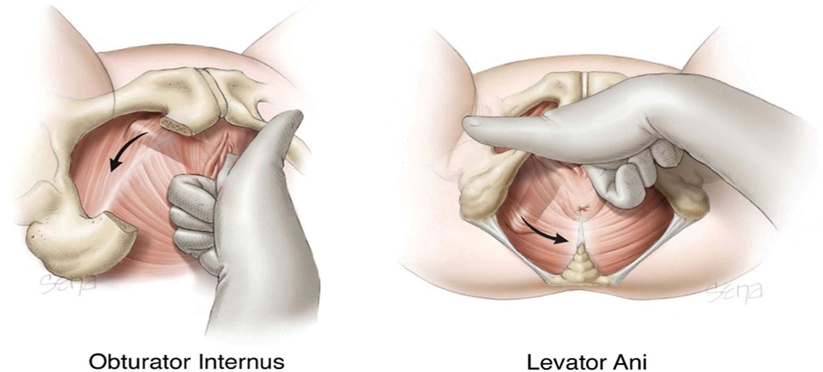

The University of Minnesota REDCap web interface was assigned as the e-Learning platform. The modules were voice-over PowerPoint presentations and were designed for easy access online at any time and were available to download. In brief, the five modules and components include (1) an overview of all the clinical measures and PM examination assessments, (2) pelvic organ prolapse (POP) assessment without and with Valsalva while also evaluating for any urinary or stool leakage during Valsalva, (3) palpatory assessment of the PV (pubococcygeus) muscle to estimate muscle integrity, (4) PM strength digital vaginal assessment for duration and symmetry, and (5) PM and internal hip myofascial pain with palpation examination that incorporates self-reported pain with pressure over specific muscles (LA and OI) areas. Full details are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

TABLE 2.

Description of the RISE pelvic examination

|

|

|

Abbreviations: RISE, RISE FOR HEALTH; PV, pubovisceral.

2.3 |. Planning Task 3: In-person training process for certification in PM assessment

To complement the e-Learning modules, the RISE in-person team also designed an in-person training and certification process. This was to confirm and document skill acquisition and skill consistency across Trainees preparatory to the RISE study. Each Trainee would first complete all five e-Learning modules as a prerequisite.

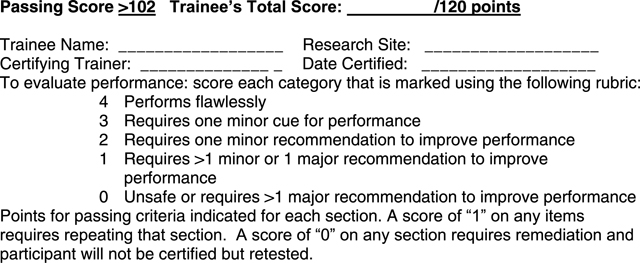

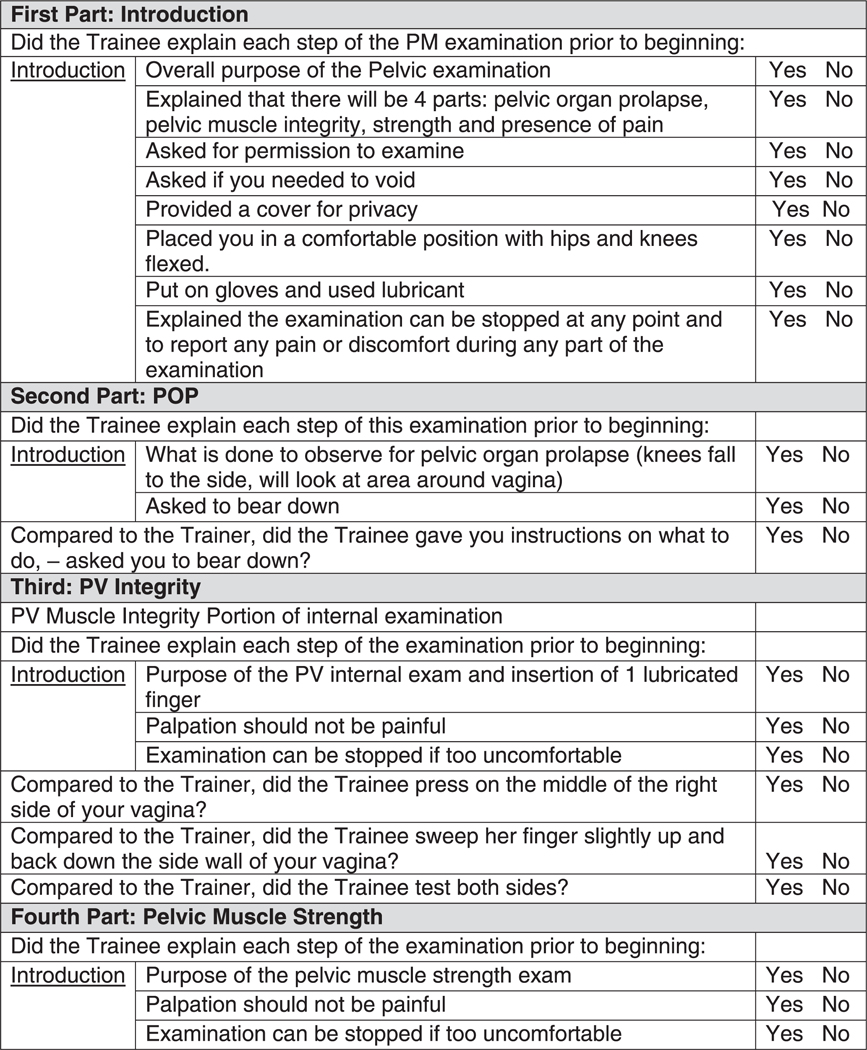

The in-person training and certification process was envisioned as a 1-day simulation experience using gynecology teaching assistants (GTA) who received training before the session and the use of the PM assessment Certification Checklist of the PM Assessment (Appendix 1) for the Trainee and the Standardized PM Checklist for the GTA (Appendix 2). To recruit Trainees, the planning team asked each of the eight PLUS clinical research sites for the RISE study to identify at least two individuals as their Trainees. Each Trainee would be an advanced practice provider (e.g., nurse practitioner, certified nurse midwife, physician assistant) or a physician, who conducts pelvic examinations as a regular component of their practice.

A competency assessment checklist was prepared for use by the Clinical Trainer with detailed steps of the process indicated. A second assessment, using the GTA checklist, was conducted by the GTA indicating whether components of the exam were completed consistently between the Trainer and Trainee. The planning team decided a score of 85% was required for passing the in-person hands-on PM assessment. However, it was also decided that those unable to successfully certify by achieving 85% during a first assessment process could undergo remediation (review of the necessary elements on the checklist and feedback with the evaluator) and be allowed a second certification opportunity within the same day.

The competency process was led by four expert clinicians (two physicians, one nurse practitioner, and one midwife) with prior experience in one or more parts of the PM assessment. Each of these clinicians would serve as a Clinical Trainer and is further referred to as such here. Each Clinical Trainer, as with all Trainees, would be required to complete all five e-Learning modules before leading the training and certification processes. Each Clinical Trainer would also be fully oriented to the highly detailed performance Certification Checklist of the PM assessment (Appendix 1) developed by the planning team to use as the tool to standardize the in-person training process, set expectations, and determine pass or fail of Trainees via a quantified scoring system. The checkoff list would be inclusive of the case report form developed for recording PM assessment data.

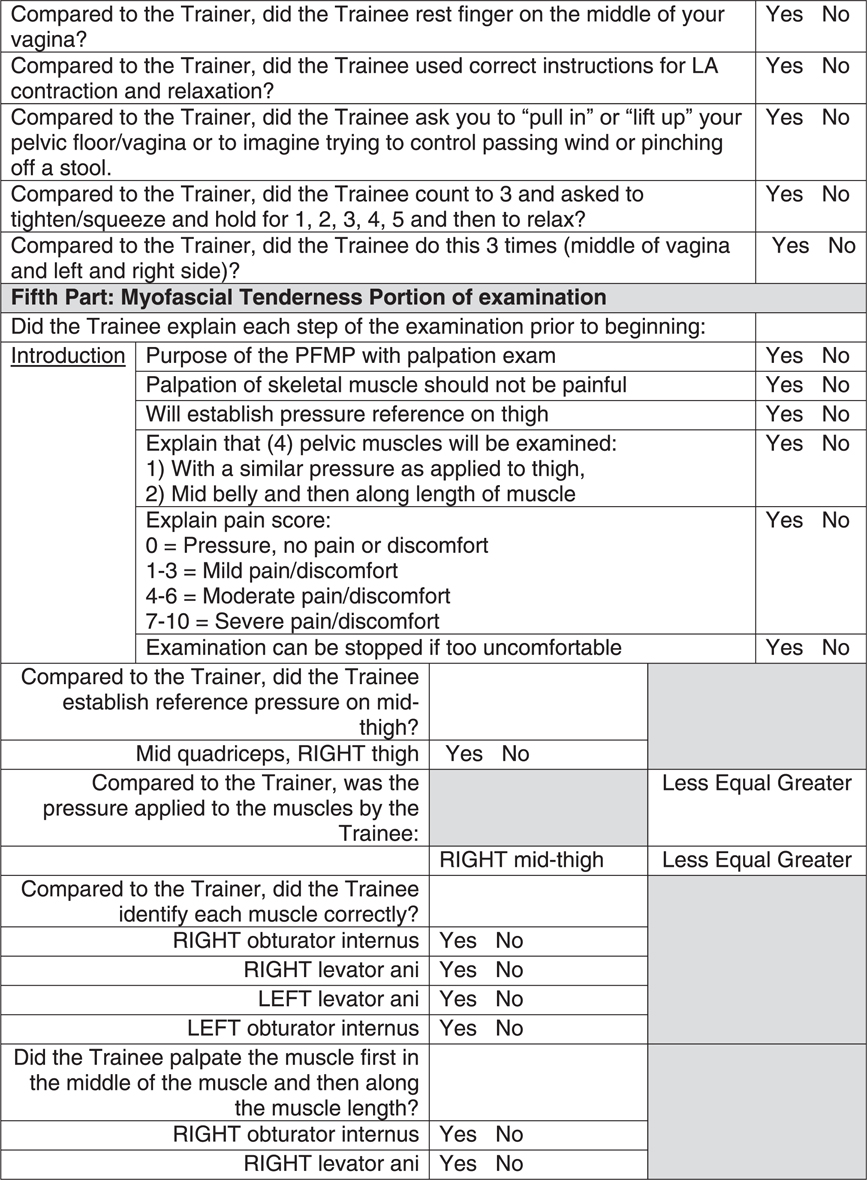

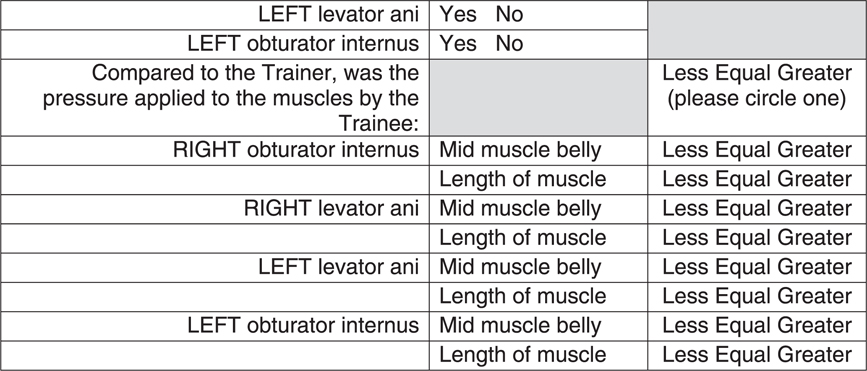

Several components of the PM assessment were recognized as not feasible for direct visualization by the Clinical Trainer such as the LA assessment and the myofascial pain assessment. Therefore, the planning team designed alternative Trainee feedback and evaluation, which included feedback from trained GTAs. The GTAs were volunteer staff at the clinical simulation center that hosted the 1-day training simulation and had prior training and competency in educating healthcare professional students in pelvic exams process and procedures. The GTAs served in the role of standardized patients but also with an evaluative capacity constructed per a performance standardized checklist of items (Appendix 2) that only they could perceive with accuracy. The details of the hands-on component of the CPMA are found in Table 2. Before the in-person training session and per request, the GTAs were provided with an overview of the entirety of the PM examination (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

RISE training, GTA pelvic examination description

| We are asking you to undergo four pelvic examinations for an NIH-funded research study on women. The examination is to test the muscles that surround your vagina. The only way to test them is to insert one finger into your vagina. These examinations will be done by an examiner (Trainer) or Trainee who is a doctor or nurse practitioner who has experience in performing pelvic examinations. The trainee will be observed by an experienced clinician (doctor or nurse practitioner) to ensure the exam is being done correctly. The reason for the pelvic examination is to check how your internal pelvic muscles, often called “Kegels”, work. There are 4 parts to this pelvic examination. A speculum will not be used. The four parts of the pelvic examination will take approximately 15–20 min. You will be asked to: • Urinate before you are examined. • Undress from the waist down and you will be given a gown to wear. • Lie on an exam table with your feet in stirrups and knees separated. 1. Look for pelvic organ prolapse (dropped bladder or uterus) • The first part of the exam is to determine if you have a dropped bladder or uterus and it only involves looking at the opening of your vagina. • The examiner will ask you to push down like you are moving your bowels and look at the opening to your vagina to see. 2. Palpate (touch) for pelvic muscle integrity • Involves examining the muscles inside your vagina. • To do this, the examiner will place a gloved lubricated finger about 1 inch inside your vagina and lightly press against the center and the left and right sides of your vagina muscles. • The examiner will then sweep slightly up and down using one finger to feel for the fullness of the muscle. 3. Test for pelvic muscle strength • While the lubricated gloved finger is in your vagina, the examiner will lightly touch three different areas in your vagina, the middle, and each side. • You will then be asked to squeeze or tighten your pelvic muscles around the examiner’s fingers. To do this you will be asked to pull in the muscle like you are holding back gas. • You will be asked to hold the muscle squeeze for 5 s and you will be asked to do this three times. 4. Check for any pain or discomfort • Before starting this exam, the examiner will first press on your thigh to let you know how the pressure will feel when doing the test inside your vagina. • The examiner will assess the muscles for any pain or discomfort. • While applying a small amount of pressure on the left and right side of the muscle, the examiner will ask you to rate any pain or discomfort you have on a scale of 0–10, with 0 being none and 10 being the most pain or discomfort. A Trainer will perform the exam at the start of this test so you will know what each part of the exam should feel like. At the end of the exam, you will be asked to compare the rainee’s examination with the examination performed by the experienced clinician. |

Abbreviations: GTA, gynecologic teaching assistants; RISE, RISE FOR HEALTH.

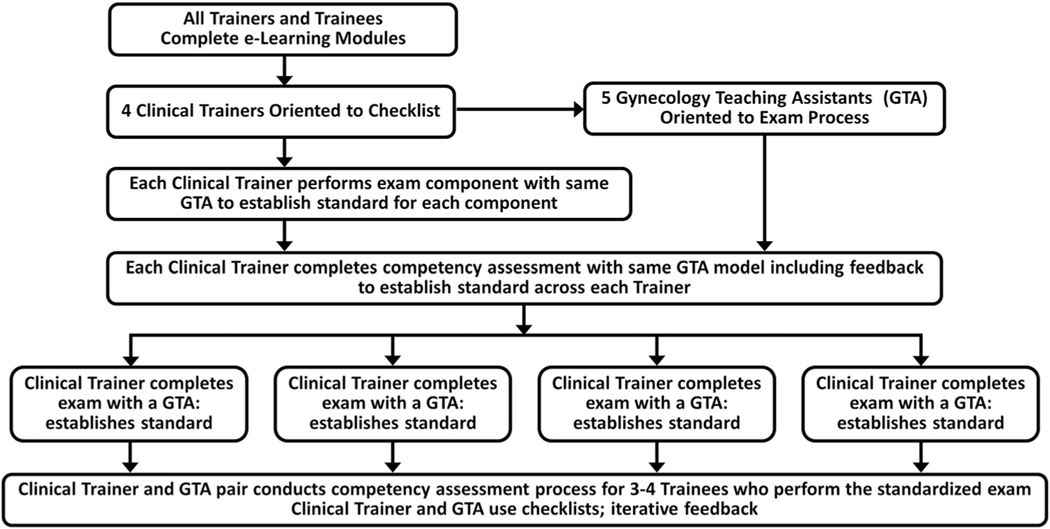

The process established for the GTAs and Clinical Trainers to ensure baseline competency (Figure 1) was as follows:

FIGURE 1.

Comprehensive pelvic muscle assessment training process

Expert Clinical Trainers review the PM exam with the lead GTA so she could ascertain specifics of the assessment (e.g., degree of finger pressure on the muscle as exerted by the expert Clinical Trainer) to establish intertrainer reliability of the PM assessment process.

Each Clinical Trainer conducts each PM component with the lead GTA for her to provide feedback about consistency between Clinical Trainers.

Each Clinical Trainer would then conduct all PM exam components with the GTA specifically assigned to her/him for later work with Trainees. The goal would be to demonstrate the exam to the GTA and establish the benchmark exam (including all components, expected sites of touch, and pressure for each component).

For each new Trainee and across every component, the GTAs would complete a standardized checklist (Appendix 2) that assessed if a step of the exam was completed or not and how consistent the exam component was to the Clinical Trainer’s criterion exam.

For the competency assessment certification, Clinical Trainers would be responsible for completing a competency certification checklist (Appendix 1) of the Trainees in performing each component of the comprehensive PM assessment in a 1:1 ratio (Clinical Trainer/Trainee).

The GTA assessment then served as an audit process and was used to provide feedback to the Trainees during the examination process as a summative review of the full assessment process and to correct the level of pressure.

Throughout the training process, to the extent possible, the planning team’s goal was to simulate the setting for a typical clinical research exam setting. Thus, it was decided that each PLUS clinical site would be asked to identify a person on their research staff (research coordinator [RC]) to attend the in-person training in the role of assistant to their site’s Trainees, further simulating and establishing the dynamic that would occur during the RISE study’s PM examination between the PM assessor and RC (chaperone and data recorder).

2.4 |. Logistics of the in-person training

The site of the in-person portion of the training program was the University of Minnesota Health Sciences Education Center in Minneapolis, MN. This location is a state-of-the-art clinical simulation center that is staffed by experts in clinical training processes and procedures and with enough space to allow for a clinical examination space for each Clinical Trainer/ Trainee/Assistant team. The center staff includes trained GTAs who participate in health professional trainee education in the performance of gynecologic pelvic examinations.

The intention of the first step of the in-person training session was to confirm the Clinical Trainer’s expectations and establish intertrainer rater reliability before going into the competency assessments of new Trainees. This step was accomplished using one GTA who provided feedback to the four Clinical Trainers as a way to confirm intertrainer reliability. The staffing model to support the training process included four GTAs who would be paired with the four Clinical Trainers to form an expert training team. Each expert Clinical Trainer/ GTA team then used detailed checklists to assess the competency of the PM assessment with each new Trainee. Hereafter, we refer to this total program for training in CPMA as the PLUS consortium’s CPMA Training Program.

2.5 |. Data analysis

Assessment results for this report are limited to module completion rates, certification pass rates presented as a number, and percent of Trainees passing by overall scores. We also report these descriptive statistics stratified by the various components.

3 |. RESULTS

Results from the planning process included consensus on the need for five discrete e-Learning modules to incorporate all components of the CPMA.

The five PM modules were made available to all PLUS members who would be participating in the in-person visit, which included content not related to PM assessment. A total of 40 PLUS members took at least some portion of the e-Learning training with 36 completing all 5 PM modules as confirmed by a Trainee e-signature documented in the e-Learning platform. Of the total 36 completers, 17 were Clinical Trainees for the PM assessment certification process during the in-person training. Other completers included the RCs who served as in-person examination chaperones and data recorders for the results of the PM examination.

All participants who completed the full in-person training (N = 17), including the initial four Clinical Trainers, met or exceeded the pre-specified overall 85% pass rate for the overall PM assessment, with an average passing rate of 96.3%. The average pass rate for each examination component was: 95.2% for the POP assessment, 97.5% for the PV muscle integrity exam, 96.2% for the PM strength exam, and 95.6% for the pelvic floor and internal hip myofascial pain for the palpation screening exam. The Trainees were also evaluated on how a description of the research exam process for the participant was conducted (average score 94.1%) and professionalism/communication (average score 98.0%) during the exam process.

From the GTA patient models’ assessments, the overall “yes” versus “not done” for the Trainees (n = 17) as a percentage for each component’s details (as listed in the Appendix) were: (1) Introduction of the examination, 78% yes; (2) the POP assessment, 97% “yes”; (3) the PV muscle integrity exam, 85% “yes”; (4) the PM strength exam, 83% “yes”; and (5) the pelvic floor myofascial pain assessment, 89% “yes.” Eighty percent of Trainees established the reference pressure on the model’s thigh before performing the internal component of the pelvic floor myofascial pain examination. The GTAs assessed the Trainee’s pressure during palpation of each muscle during the myofascial pain assessment as “less pressure,” “greater pressure,” or “equal pressure” as compared to the Clinical Trainers. The reported percentage of Trainees using less pressure than the Clinical Trainer’s pressure was 7%, equal pressure was 31%, and greater pressure was 62%.

4 |. DISCUSSION

We present the novel CPMA Training Program developed by the PLUS research consortium that included Gynecology Teaching Assistants in sufficient detail to reproduce it for use in research and other settings that require high-quality training in PM assessment. Standardization and current knowledge application in assessment measures are critical for accurate interpretation of scientific results, but also for application to clinical and community-based populations. Standardization of training for these broad applications relies on simplicity without loss of comprehensiveness or rigor, and a balance of feasibility and burden matched against the opportunity to gain accurate assessments for research purposes and clinical applications as indicated.

Extensive efforts have been taken to validate instruments used for outcome assessment in the RISE for Health study including validation of the Bladder Health Index.29 Similarly, the pelvic examination protocol was designed using the best available evidence and expert opinion with rigorous e-Learning and centralized in-person training for all clinical evaluators to ensure consistency across participants and sites.

We used existing validated measures whenever possible for the evaluation of PM integrity, function, and pain with the additional focus of creating a physical assessment process (relative to its application in the RISE study) yet simplistic enough to be reproducible in a standardized manner. The long-term outcome expected is generating accurate information and minimizing participant burden.

For example, our method for prolapse evaluation follows guidelines for standard clinical POP measurements23,30 using prolapse beyond the hymen as a dichotomous outcome and simplifying the presence or absence of prolapse. There is good evidence that clinically significant and bothersome prolapse does not occur until it is beyond the hymen. As the RISE study is aimed at evaluating BH in community-dwelling women, rather than women with known pelvic floor disorders, we elected not to perform a detailed pelvic organ prolapse quantification examination; thus, minimizing participant and evaluator burden. Similarly, there are numerous validated and reliable methods to assess PM strength.18–21 Our protocol selected the Modified Oxford assessment24 with its standardized, validated scoring measure for the strength assessment which also aligns with the current understanding of muscle function.

Standardized, validated assessments of PV integrity and pelvic myofascial pain are published but not widely adopted yet.26–28 The PV muscle integrity assessment was included as an estimate of prior tear away from its origin (which is chronic).5,6 Measurement was simplified as the presence or absence of the PV muscle as a categorical outcome with the option for “equivocal” if the examiner was uncertain.13 There is evidence that loss of PV muscle fibers (tear) indicates/or is associated with LUTS and prolapse. The RISE study will determine if a physical assessment estimate of PV loss is associated with measures of BH.

In the PM functional strength measure, we relied on techniques well-documented in the literature, slightly modified to align with modern understandings of anatomical landmarks. Because our goal was “comprehensive” assessment, we additionally included PM muscle pain assessment, which has typically not been evaluated in research contexts or clinical settings focusing on BH. PM pain with palpation has been associated with LUTS symptoms.25

One of the most innovative highlights of our PM exam is combining integrity (tear), strength and pain in the assessment and planning to explore all three with BH. Putting these many components of PM assessment together in a single training program is a strength of our work. In addition to a comprehensive assessment process based on the latest knowledge and understanding of PM anatomy and function, an additional strength of our methods is the use of e-Learning and centralized in-person training and evaluation using experienced women who volunteer as models for pelvic exams and were trained GTAs. A priori metrics were set to ensure adequate training and consistency across examiners. Postexam assessments and immediate feedback from GTAs yielded high pass rates from Trainees.

Limitations and challenges to developing the in-person part of the CPMA training included the inability to rigorously validate PM assessment using test–retest reliability or validity testing of exam measures within a single-day training program. However, the training resources and materials are available for replication testing of this process to extend into train-the-trainer models and further validity testing. Future studies beyond this initial development of the CPMA training program should include test/retest reliability testing, inter-/intrarater reliability of exam measures and indicators of their validity, and evaluation of sustainment of competence following the initial assessment. With the building blocks in place, e-Learning modules, in-person training processes, use of checklist assessments of Trainee by Clinical Trainer and GTA and initial success indicated by our findings, the field is now primed for undertaking these next steps. A potential limitation to the use of the process is the cost of the training process. This should be proactively planned into research budgets during the proposal phase.

5 |. CONCLUSIONS

As the PLUS research consortium prepared to initiate the RISE study, the need for a comprehensive PM assessment training program was a necessary component of the in-person examination process to support new insights and discoveries related to BH and the prevention of LUTS. Through a process of literature review and expert-generated procedures, a comprehensive PM assessment training program was developed that was based on current knowledge and understanding of PM anatomic and physiologic function. The RISE CPMA training program was successfully conducted to assure standardization of the PM assessment process across the PLUS multicenter research study. These resources and tools are available for use by others who have a need for a standardized clinician training program in PM assessment.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the following: RISE research coordinators for their invaluable contributions: UCSD: Kyle Herrala, Elia Smith, and Dulce Rodriguez-Ponciano; UMICH: Sarah Hortsch and Ruta Misiunas; UPenn: Emily Gus; WASHU: Ratna Pakpahan; Loyola: Mary Tulke; UIC: Elise Levin; Yale: Leslie Burke-Hovey; NU: Melissa Marquez and Sophia Kallas; UAB: Hannah Burns; Emory: Taressa Sergent; Meg Tolbert, CRNP for assistance as a PM Clinical Trainer; Diane K. Newman, Melanie Meister, Jerry L. Lowder, and Sarah Hortsch for a voice over for PM e-Learning modules; and Vanika Chary and K. D. Bohara for implementation of the PM training. They would also like to thank the collegial research work of the Prevention of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Research Consortium members. This work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases at the National Institutes of Health by cooperative agreements (U24 DK106786, U01 DK106853, U01 DK126045, U01 DK106858, U01 DK106898, U01 DK106893, U01 DK106827, U01 DK106908, U01 DK106892). and the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health Office of Research on Women’s Health.

Diane K. Newman: Consultant: EBT Medical, COSM, and Urovant; research funding: Society for Urologic Nurses and Associates; editorial: Digital Science Press; and royalties: Springer. Jerry L. Lowder: Expert witness. Colleen M. Fitzgerald: Royalties: UptoDate and Expert Witness. Cynthia S. Fok: Royalties: UptoDate and consultant: UroCure. Emily S. Lukacz: Consultant: Axonics, Pathnostics, Urovant, and BioElectronics; research funding: Boston Scientific, Cogentix/Uroplasty; and royalties: UpToDate.

Funding information

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

APPENDIX 1: CERTIFICATION CHECKLIST FOR THE RISE COMPREHENSIVE PELVIC MUSCLE ASSESSMENT

| SKILL: Pelvic Examination | Score | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Preparation-Required Review: | ||

| Review RISE Manual of Operations | NS | |

| View Powerpoint presentations | NS | |

| View Instructional Videos & Relevant Publications | NS | |

| CONDUCT Practice with Volunteers at your site (if possible) | NS | |

| Section I. Preparation of Participant | ||

| Performs hand hygiene, dons gloves appropriately, applies lubricant | ||

| Explains examination procedure: “Hello [participant’s name], 1 am (examiner’s name and profession [MD, NP etc], 1 am an investigator [or principal investigator] at/with the [research site] being a participant in this study. Thank you so much for being a participant in this study. Now 1 am going to do a pelvic examination. 1 do not use a speculum for this exam. First, 1 will be looking at the outside of your vagina and asking you to cough. Then, 1 will insert one finger into your vagina to test the strength of your muscles. 1 will put pressure on different areas in your vagina to determine the muscle tone and if you have any discomfort. At any time during the exam you can ask to stop. Please also let me know if there is any pain or discomfort during the exam. You are in control of the process. Is it OK if 1 begin the exam? |

||

| Asks participant if she needs to void | ||

| Positions comfortably in supine position, hips and knees flexed. | ||

| Maintains proper draping of participant during exam | ||

| Passing Score Section 1: /20 | ||

| Section 2. Observation of Perineum for POP | ||

| Explains examination procedure to participant “First, please let your knees fall to the side. 1 am going to start by looking at the opening of the vagina and then while you strain, push or bear down like you are moving your bowels.” |

||

| Asks participant to bear down while observing the perineum | ||

| Passing Score Section 2: /8 | ||

| Section 3. Internal Examination-PV Muscle Integrity | ||

| Informs participant that the internal examination will be performed next. “I will be feeling the muscles inside the vagina. I will not use a speculum but will place 1 finger in your vagina. I will examine the muscles on each side of your pelvis.” |

||

| Index finger is placed at the expected anatomical location of the midmuscle body of the PV as felt about 2 cm inside the vaginal sidewall, with the finger curled to the right or left | ||

| Sweeps slightly up and back down using the finger pad at each point to palpate for fullness of the PV muscle body. It is allowed to ask the woman to attempt a pelvic floor muscle contraction as a check on impression regarding felt fullness. | ||

| Repeats exam bilaterally | ||

| Completes CRF for PV muscle integrity scoring related to PV muscle | ||

| Completes CRF for pain during PV palpatory assessment, including assessing for indicators of pain from both observation and verbal confirmation from the woman | ||

| Passing Score Section 3: /24 | ||

| Section 4. Internal Examination-PM Functional Strength | ||

| Informs the participant of the next part of the internal examination, pelvic muscle strength test. “Next, I will examine the muscles around your vagina. I will ask you to squeeze these muscles around my fingers. You may know this as a Kegel contraction.” |

||

| Inserts 1–2 gloved, lubricated index (and middle) fingers (pads down) into the vagina. Inserts fingers (posterior) to depth of proximal interphalangeal joint. Rests fingers on muscle belly of LA -midline | ||

| Uses correct instructions for LA contraction and relaxation “I am going to count to 3 and when I say 3,I want you to tighten and squeeze your pelvic floor muscle and hold it as I count to 5. I am going to have you do this 3 times.” Explains she is to “pull in” or “lift up” the floor of her vagina or to imagine she is trying to control passing wind or pinching off a stool. |

||

| At a count of 3, asks participant to tighten/squeeze and hold for 1,2,3, 4, 5 and asks her to relax. | ||

| Accurately evaluates LA muscle contraction/relaxation midline | ||

| Repeats exam bilaterally (right & left side) repeating same instructions | ||

| Completes CRF for PM strength section | ||

| Passing Score Section 4: /28 | ||

| Section 5. Obturator Internus and Levator Ani Myofascial Pain Screening Examination | ||

| Introduces the participant to the myofascial pain exam | ||

| “Now, I would like to move to the next step of the assessment focused on assessing the muscles of your pelvic floor for any pain or discomfort with pressure. I will be pressing on 4 muscles during a vaginal examination.” Is it ok to proceed? | ||

| Orients the participant to the internal examination by pressing on midthigh to provide a reference pressure that will be applied on the exam “First, I will first press on your thigh to let you know how the pressure will feel when I press internally (inside you). Do you feel my finger on your thigh? (palpate mid-thigh) This is as firmly as I am going to be pressing on the muscles. Is there any pain or discomfort? If not, this will be a “0” on a scale of “0–10”. Please let me know if you experience pain or discomfort and rate that pain or discomfort on a scale of 0 to 10. No pain or discomfort would beaO and severe pain or discomfort is a 10.” |

||

| Informs participant that 1 finger will be inserted vaginally. “I will begin the exam by inserting 1 finger into your vagina and begin with the muscles on your RIGHT side, then will test the muscles on your left side. ” |

||

| Asks participant if pressure applied to RIGHT Ol induces pressure-only vs pain or discomfort. **Trainee directs hand/finger to the 10–11 O’clock position. “When I press on this muscle, if it only pressure, a “0” or is there pain or discomfort? If there is pain or discomfort, please rate it on a scale of 1–10. “Mild” pain or discomfort would be a 1,2 or 3, “moderate” pain or discomfort a 4,5 or 6, and “severe”pain or discomfort a 7,8,9, or 10.” |

||

| Trainee may move knee of RIGHT knee medially-laterally-medially to help identify Ol muscle. | NS | |

| Asks participant if pressure applied to RIGHT LA induces pressure- only vs pain or discomfort. **Trainee will direct hand/finger to the 7–8 o’clock position. (During application of pressure) When 1 press on this muscle, is there pressure or pain/discomfort? (May reorient to pain scales “If there is pain or discomfort, please rate it on a scale of 1–10. “Mild” pain or discomfort would be a 1,2 or 3, “moderate” pain or discomfort a 4,5 or 6, and “severe”pain or discomfort a 7,8,9, or 10.” |

||

| Asks participant if pressure applied to LEFT OI induces pressure-only vs pain or discomfort. **Trainee will direct hand/finger to the 1–2 o’clock position. (During application of pressure) When I press on this muscle, is there pressure or pain/discomfort? (May reorient to pain scales “If there is pain or discomfort, please rate it on a scale of 1–10. “Mild” pain or discomfort would be a 1,2 or 3, “moderate” pain or discomfort a 4,5 or 6, and “severe” pain or discomfort a 7,8,9, or 10.” |

||

| Asks participant if pressure applied to LEFT LA induces pressure-only vs pain or discomfort. **Trainee will direct hand/finger to the 4–5 o’clock position. (During application of pressure) When 1 press on this muscle, is there pressure or pain/discomfort? (May reorient to pain scales “If there is pain or discomfort, please rate it on a scale of 1–10. “Mild” pain or discomfort would be a 1,2 or 3, “moderate” pain or discomfort a 4,5 or 6, and “severe” pain or discomfort a 7,8,9, or 10.” |

||

| Passing Score Section 5: /28 | ||

| Section 6: OVERALL: Professionalism/Communication | ||

| Develops a professional rapport with the participant. | ||

| Speaks at an appropriate pace | ||

| Demonstrates appropriate closure after exam | ||

| Passing Score Overall Section 6: /12 | ||

| Total Score (Passing ≥102/120 points) | ||

APPENDIX 2: STANDARDIZED PM CHECKLIST FOR GTA ASSESSMENT OF THE TRAINEE

Instructions: There are 5 components to this exam, Introduction and 4 parts. We are asking you to evaluate and complete the specific section after each component.

|

|

|

Footnotes

ETHICS STATEMENT

This manuscript is the original work of the authors and has not been submitted for publication elsewhere.

PREVENTION OF LOWER URINARY TRACT SYMPTOMS RESEARCH CONSORTIUM MEMBERS

Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, IL (U01DK106898): Multi-Principal Investigators: Linda Brubaker, MD and Elizabeth R. Mueller, MD, MSME, and Investigators: Marian Acevedo-Alvarez, MD, Colleen M. Fitzgerald, MD, MS, Cecilia T. Hardacker, MSN, RN, CNL; Jeni Hebert-Beirne, PhD, MPH, and Missy Lavender, MBA. Northwestern University, Chicago IL (U01DK126045)—Multi-Principal Investigators: James W. Griffith, PhD; Kimberly Sue Kenton, MD; Melissa Simon, MD, MPH; and Investigator: Julia Geynisman-Tan, MD. University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL (U01DK106858)—Principal Investigator: Alayne D. Markland, DO, MSc and Investigators: Tamera Coyne-Beasley, MD, MPH, FAAP, FSAHM; Kathryn L. Burgio, PhD; Cora E. Lewis, MD, MSPH; and Camille P. Vaughan, MD, MS; Beverly Rosa Williams, PhD. University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA (U01DK106827)—Principal Investigator: Emily S. Lukacz, MD and Investigators: Sheila Gahagan, MD, MPH; D. Yvette LaCoursiere, MD, MPH; and Jesse Nodora, DrPH. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI (U01DK106893)—Principal Investigator: Janis M. Miller, PhD, APRN, FAAN and Investigator: Lisa Kane Low, PhD, CNM, FACNM, FAAN. University of Minnesota (Scientific and Data Coordinating Center), Minneapolis MN (U24DK106786)—Multi-Principal Investigators: Gerald McGwin, Jr., MS, PhD and Kyle D. Rudser, PhD. Investigators: Sonya S. Brady, PhD; Haitao Chu, MD; Bernard L. Harlow, PhD; Cynthia S. Fok, MD, MPH; Peter Scal, PhD; and Todd Rockwood, PhD. University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA (U01DK106892)—Multi-Principal Investigators: Diane K. Newman, DNP; Ariana L. Smith, MD; Investigators: Amanda Berry, MSN, CRNP; Andrea Bilger, MPH; Terri H. Lipman, PhD; Heather Klusaritz, PhD, MSW; Ann E. Stapleton, MD; and Jean F. Wyman, PhD. Washington University in St. Louis, Saint Louis, MO (U01DK106853)—Principal Investigator: Siobhan Sutcliffe, PhD, ScM, MHS and Investigators: Aimee S. James, PhD, MPH; Jerry L. Lowder, MD, MSc; and Melanie R. Meister, MD, MSCI. Yale University, New Haven, CT (U01DK106908)—Principal Investigator: Leslie M. Rickey, MD, MPH and Investigators: Marie A. Brault, PhD; Deepa R. Camenga, MD, MHS; and Shayna D. Cunningham, PhD. Steering Committee Chair: Linda Brubaker, MD. UCSD, San Diego. (January 2021–). NIH Program Office: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Division of Kidney, Urologic, and Hematologic Diseases, Bethesda, MD. NIH Project Scientist: Julia Barthold, MD.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Melanie Meister, Lisa K. Low, Julia Geynisman-Tan None, Alayne Markland, Sara Putnam, Kyle Rudser, Ariana L. Smith, and Janis M. Miller declare no conflict of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supporting Information of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.DeLancey JOL. Lies, damned lies, and pelvic floor illustration: confused about pelvic floor anatomy? You are not alone. Int Urogynecol J. 2022;33(3):453–457. doi: 10.1007/s00192-022-05087-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeLancey J. The appearance of levator ani muscle abnormalities in magnetic resonance images after vaginal delivery. Obstetr Gynecol. 2003;101(1):46–53. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02465-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meister MR, Shivakumar N, Sutcliffe S, Spitznagle T, Lowder JL. Physical examination techniques for the assessment of pelvic floor myofascial pain: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219(5):497. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Egorov V, Raalte H, Shobeiri SA. Tactile and ultrasound image fusion for functional assessment of the female pelvic floor. Open J Obstetr Gynecol. 2021;11(6):674–688. doi: 10.4236/ojog.2021.116063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Low LK, Zielinski R, Tao Y, Galecki A, Brandon CJ, Miller JM. Predicting Birth-Related levator ani tear severity in primiparous women: evaluating maternal recovery from labor and delivery (EMRLD Study). Open J Obstetr Gynecol. 2014;4(6): 266–278. doi: 10.4236/ojog.2014.46043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller JM, Low LK, Zielinski R, Smith AR, Delancey JOL, Brandon C. Evaluating maternal recovery from labor and delivery: bone and levator ani injuries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(2):188. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shek K, Dietz H. Intrapartum risk factors for levator trauma. BJOG, Int J Obstetr Gynaecol. 2010;117(12):1485–1492. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02704.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valsky DV, Lipschuetz M, Bord A, et al. Fetal head circumference and length of second stage of labor are risk factors for levator ani muscle injury, diagnosed by 3-dimensional transperineal ultrasound in primiparous women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(1):91. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.03.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harlow BL, Bavendam TG, Palmer MH, et al. The Prevention of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (PLUS) Research Consortium: a transdisciplinary approach toward promoting bladder health and preventing lower urinary tract symptoms in women across the life course. J Women’s Health. 2018;27(3): 283–289. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2017.6566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith AL, Rudser K, Harlow BL, et al. RISE FOR HEALTH: rationale and protocol for a prospective cohort study of bladder health in women. Neurourol Urodyn. 2022. doi: 10.1002/nau.25074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Frawley H, Shelly B, Morin M, et al. An International Continence Society (ICS) report on the terminology for pelvic floor muscle assessment. Neurourol Urodyn. 2021;40(5): 1217–1260. doi: 10.1002/nau.24658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bø K, et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175(1):10–17. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70243-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheng Y, Low LK, Liu X, Ashton-Miller JA, Miller JM. Association of index finger palpatory assessment of pubovisceral muscle body integrity with MRI-documented tear. Neurourol Urodyn. 2019;38(4):1120–1128. doi: 10.1002/nau.23967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delancey JOL. Taking a systematic approach to urinary incontinence. Contemp OB/GYN. 2016;61(8):30–32. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zubieta M, Carr RL, Drake MJ, Bø K. Influence of voluntary pelvic floor muscle contraction and pelvic floor muscle training on urethral closure pressures: a systematic literature review. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27(5):687–696. doi: 10.1007/s00192-015-2856-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim J, Betschart C, Ramanah R, Ashton-Miller JA, DeLancey JOL. Anatomy of the pubovisceral muscle origin: macroscopic and microscopic findings within the injury zone. Neurourol Urodyn. 2015;34(8):774–780. doi: 10.1002/nau.22649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dietz H, Steensma A. The prevalence of major abnormalities of the levator ani in urogynaecological patients. BJOG, Int J Obstetr Gynaecol. 2006;113(2):225–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00819.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brink CA, Sampselle CM, Wells TJ, Diokno AC, Gillis GL. A digital test for pelvic muscle strength in older women with urinary incontinence. Nurs Res, 38(4):196–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newman DK, Laycock J. Clinical evaluation of the pelvic floor muscles. Pelvic Floor Re-Education: Principles and Practice. Springer Nature; 2008:91–104. doi: 10.1007/978-1-84628-505-9_9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newman DK, Borello-France D, Sung VW. Structured behavioral treatment research protocol for women with mixed urinary incontinence and overactive bladder symptoms. Neurourol Urodyn. 2018;37(1):14–26. doi: 10.1002/nau.23244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bo K, Frawley HC, Haylen BT, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for the conservative and nonpharmacological management of female pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017;36(2): 221–244. doi: 10.1002/nau.23107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Messelink B, Benson T, Berghmans B, et al. Standardization of terminology of pelvic floor muscle function and dysfunction: report from the pelvic floor clinical assessment group of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2005;24(4):374–380. doi: 10.1002/nau.20144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall AF, Theofrastous JP, Cundiff GW, et al. Interobserver and intraobserver reliability of the proposed International Continence Society, Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, and American Urogynecologic Society pelvic organ prolapse classification system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175(6): 1467–1471. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70091-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chevalier F, Fernandez-Lao C, Cuesta-Vargas AI. Normal reference values of strength in pelvic floor muscle of women: a descriptive and inferential study. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14:143. doi: 10.1186/s12905-014-0143-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meister MR, Sutcliffe S, Badu A, Ghetti C, Lowder JL. Pelvic floor myofascial pain severity and pelvic floor disorder symptom bother: is there a correlation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221(3):235. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.07.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meister MR, Sutcliffe S, Ghetti C, et al. Development of a standardized, reproducible screening examination for assessment of pelvic floor myofascial pain. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(3):255. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.11.1106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bø K, Finckenhagen HB. Vaginal palpation of pelvic floor muscle strength: inter-test reproducibility and comparison between palpation and vaginal squeeze pressure. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80(10):883–887. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2001.801003.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pastore EA, Katzman WB. Recognizing myofascial pelvic pain in the female patient with chronic pelvic pain. J Obstet, Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2012;41(5):680–691. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2012.01404.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lukacz ES, Constantine ML, Kane Low L, et al. Rationale and design of the validation of bladder health instrument for evaluation in women (VIEW) protocol. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21(1):18. doi: 10.1186/s12905-020-01136-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baden WF, Walked TA. Genesis of the vaginal profile: a correlated classification of vaginal relaxation. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1972;15(4):1048–1054. doi: 10.1097/00003081-197212000-00020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supporting Information of this article.