Abstract

Probiotics have shown a benefit in reducing necrotising enterocolitis in the premature infant, however the study of their effect on premature neonates’ neurodevelopment is limited. The aim of our study was to elucidate whether the effect of Bifidobacterium bifidum NCDO 2203 combined with Lactobacillus acidophilus NCDO 1748 could positively impact the neurodevelopment of the preterm neonates. Quasi-experimental comparative study with a combined treatment of probiotics in premature infants < 32 weeks and < 1500 g birth weight, cared for at a level III neonatal unit. The probiotic combination was administered orally to neonates surviving beyond 7 days of life, until 34 weeks postmenstrual age or discharge. Globally, neurodevelopment was evaluated at 24 months corrected age. A total of 233 neonates were recruited, 109 in the probiotic group and 124 in the non-probiotic group. In those neonates receiving probiotics, there was a significant reduction in neurodevelopment impairment at 2 years of age RR 0.30 [0.16–0.58], and a reduction in the degree of impairment (normal-mild vs moderate-severe, RR 0.22 [0.07–0.73]). Additionally, there was a significant reduction in late-onset sepsis (RR 0.45 [0.21–0.99]). The prophylactic use of this probiotic combination contributed to improving neurodevelopmental outcome and reduced sepsis in neonates born at < 32 weeks and < 1500 g.

Subject terms: Paediatric research, Neurodevelopmental disorders, Nutrition

Introduction

Probiotics are “live microorganisms which, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host”1. Preterm neonates, below 32 weeks gestational age and under 1500 g birthweight, show dysbiosis produced by a delay in microbiota acquisition2. Dysbiosis is combined with a substantial difference in microbiota composition, with lower numbers of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium (considered protective microorganisms) and risen Enterobacteriaceae, containing potential pathogens such as Escherichia coli and Klebsiella2. Delayed human milk introduction, early antibiotic therapy, caesarean delivery, and total parenteral nutrition, predispose to microbiota imbalance3. In premature infants, dysbiosis could dysregulate proinflammatory and protective factors, increasing the risk of necrotising enterocolitis (NEC), and raising mortality3. Nowadays, numerous publications show the benefit of using probiotics to prevent NEC and late onset sepsis (LOS), especially when combining strains of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus4–6.

A premature infant is faced with a variety of neurological complications and potential sequelae, including psychomotor and neurological delay, with consequences beyond cerebral palsy, hearing loss and blindness7,8. With regards to neurodevelopment, the gut-brain axis is interconnected through endocrine, neural and immune pathways9–11. Microbiota, with the intrinsic capability of processing indispensable metabolites, regulating pathogenic microorganisms, and modulating the immune response3,12—for instance by reducing gut permeability to the Lipopolysaccharide (LPS, pro-inflammatory factor)3,12—could play a critical role in the brain-gut axis11. Substances such as the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), neurotrophins, or interleukin-6, involved in neuroinflammation and neurodevelopment13, can be regulated by changes in the microbiota14. Furthermore, the BDNF, the nerve growth factor and neurotrophins 3 and 4, promote neurone survival and diminish apoptosis in the central and peripheral nervous systems, being of vital importance in the pre and postnatal development of the brain15,16. Despite all the previous findings, little has been published regarding the effect of probiotics on the premature infant neurodevelopment, with recent published studies finding no benefit17–21.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the effect of combining two probiotics (Bifidobacterium bifidum NCDO 2203 and Lactobacillus acidophilus NCDO 1748) in the neurodevelopment of preterm neonates below 32 weeks’ gestation and a birthweight under 1500 g. This probiotic combination has shown to be safe and beneficial in premature neonates in the prevention of NEC4. We hypothesised that this mixture would contribute to better neurodevelopmental outcomes of preterm neonates when assessed at 24 months corrected age. Secondarily, these probiotics could reduce NEC, LOS, intraventricular haemorrhage and neonatal mortality in accordance with previous studies4,6.

Materials and methods

Design

Quasi-experimental, unicentric cohort study, where the probiotic intervention was implemented for one group (born 2014–2016) and compared to a control group (born 2018–2019) with follow-up and neurodevelopment evaluation with neuropsychological tests at 24 months corrected age. Quasi-experimental studies aim to evaluate interventions but do not use randomisation. Given the described high risk of cross-contamination and ethical concerns22,23, we sought a sequential design with consecutive recruitment, without randomisation, with a washout period between both groups (year 2017)22. Using “Power and Sample Size Calculations”24 version 3.0.14, considering an alpha risk of α = 0.05 and a beta risk of β = 0.2 in a bilateral contrast, a minimum of 90 subjects in each group were required to detect a statistically significant difference between groups, where for the control group the proportion of some neurodevelopmental alteration was expected to be at least 0.4 and for the group treated with probiotics at least 0.2. The accepted loss-to-follow-up rate was 20%, which meant the subjects needed were 109 in both groups. Expecting higher mortality in the control group, as probiotics have been shown to reduce mortality4, we increased the control group by 10% to ensure having enough sample size at the 24-month evaluation. The values of α and β were selected in line with standard scientific publications25,26 ensuring adequate significance with optimum statistical power.

Patients and intervention

Infants born below 32 weeks gestational age and birth weight under 1500 g cared for at BCNatal Hospital Clínic (tertiary neonatal unit) in Barcelona between January 2014 and December 2019. Patients received a daily dose of 6 × 109 UFC Infloran® -Berne, Switzerland- (Bifidobacterium bifidum NCDO 2203 and Lactobacillus acidophilus NCDO 1748) from 7 days of life until reaching a postmenstrual age of 34 weeks or discharge. The probiotic mixture was provided in capsules, which were opened, dissolved in water and given orally or via nasogastric tube, according to the feeding regime of each neonate (breast milk, donor milk or formula). Where concerns for NEC or LOS were present, probiotics were stopped and reinstated once enteral feeds were recommenced. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee in Drug Research of Hospital Clínic (HCB/2021/0454-April 2021). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. The unit had an existing standardised nutrition protocol.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

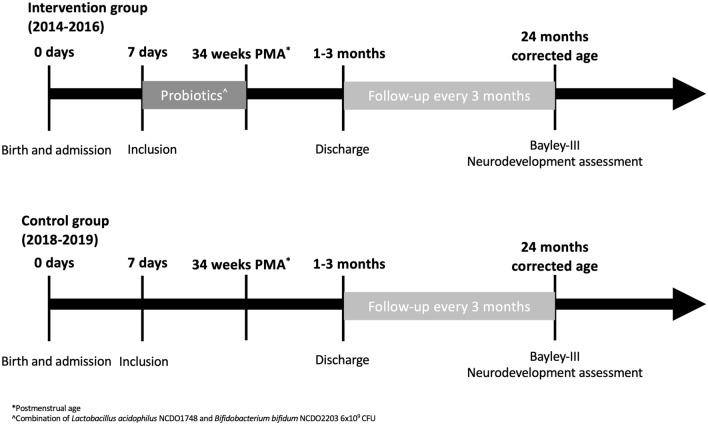

All neonates below 32 weeks gestational age and 1500 g who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were recruited, independently of their method of delivery. Those born between years 2014 and 2016 were allocated to the intervention group and received the probiotic combination (Fig. 1). The control group was created using neonates born between years 2018 and 2019. In this group we included all neonates born under 32 weeks, and 1500 g and surviving beyond 7 days of life (age when probiotics were introduced in the previous cohort).

Figure 1.

Brief depiction of the conducted study, group intervention, follow-up and main analysed outcome.

All neonates presenting with suspected congenital anomalies, inborn errors of metabolism, or genetic defects were excluded. Infants with a suspected syndrome, or who had suffered events beyond the neonatal period, not related to prematurity, that could entail impairment in neurodevelopment (severe cranioencephalic trauma, oncological process, meningitis, or exposure to toxic substances) were also excluded.

Outcomes

All patients underwent a standardised follow-up program for high-risk premature infants at our centre, up until 24 months corrected gestational age. At that stage, a Bayley-III scale test27 was included in an extensive examination performed by independent assessors, blinded to group allocation. After this evaluation, patients were divided into four categories according to their degree of neurodevelopment: survival without neurodevelopment impairment (normal neurodevelopment), mild impairment, moderate impairment, or severe impairment28. Mild impairment was considered if they had muscle tone changes, impaired fine or gross motor coordination, Bayley scale score between 71 and 84, moderate behaviour disorders or mild visual disability. Moderate impairment was diagnosed when suffering from spastic diplegia, hemiplegia, seizures (non-febrile), Bayley scores between 50 and 70, severe behaviour disorders, moderate visual disability or mild-moderate hypoacusis. Severe impairment was attributed to subjects with spastic quadriplegia, choreoathetosis, ataxia, Bayley score < 50, blindness or severe hypoacusis.

The secondary outcomes were the incidence of NEC, all-cause mortality, LOS, retinopathy of prematurity, intraventricular haemorrhage and intensive care length of stay. We defined NEC as those cases fulfilling the stage II or above of the modified Bell’s Criteria29. LOS was defined as a positive blood culture beyond 72 h of life. Close monitoring was implemented for side effects of the probiotic administration and probiotic sepsis.

Statistical analysis and measurement of treatment effect

IBM SPSS Statistics 27.0.1.0 was used for the statistical analysis. Non-parametrical analysis with a double-sided Mann–Whitney U test was calculated for all continuous variables, whilst for categorical variables the chi-square test was applied. In all cases, 0.05 was considered the threshold of statistical significance. The relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence intervals were determined for dichotomous variables. When encountering significant differences, the number needed to treat (NNT) was calculated.

Consent statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital Clínic (HCB/2021/0454- April 2021). Informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians for all subjects involved in the study.

Results

Baseline characteristics

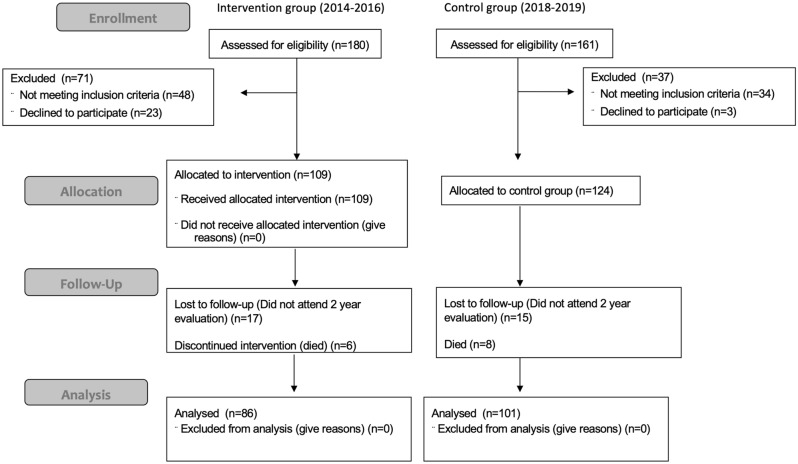

A total of 233 neonates were included in the analysis after fulfilling all inclusion and exclusion criteria: 109 neonates in the probiotic group and 124 in the control group (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Flowchart showing study selection of subjects.

Preterm infants that received probiotics were significantly more mature than those neonates that did not receive probiotics (29 weeks vs 28.5 weeks), however, this difference had no clinical relevance. There was also a moderately higher incidence of multiple gestation births and preeclampsia in the probiotic group. There were no other significant differences between groups at baseline (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the probiotic and non-probiotic cohort.

| Variable | Probiotics (n = 109) | No Probiotics (n = 124) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age (weeks) | 29 (27.9–30.3) | 28.5 (26.9–30.0) | p = 0.034* |

| Weight (g) | 1040 (909–1260) | 1065 (830–1280) | NS |

| Maternal age (years) | 35(29–38) | 34 (30–37) | NS |

| Multiple gestation | 50 (45.9%) | 41 (33.1%) | p = 0.046* |

| Antenatal steroids (full course) | 80 (73.4%) | 95 (76.6%) | NS |

| Antenatal steroids (partial course) | 25 (22.9%) | 25 (20.2%) | NS |

| Sex (men) | 58 (53.2%) | 54 (43.5%) | NS |

| Maternal hypertension | 27 (24.8%) | 16 (12.9%) | p = 0.020* |

| Labour (caesarean) | 73 (67%) | 75 (60.5%) | NS |

| Chorioamnionitis | 29(26.6%) | 30 (24.8%) | NS |

| Advanced resuscitation | 18 (16.7%) | 18 (14.8%) | NS |

| Umbilical artery pH | 7.27 (7.21–7.32) | 7.26(7.19–7.30) | NS |

| Apgar, 5 min (median and IQR) | 9 (8–10) | 9 (8–10) | NS |

| Exclusive breastfeeding | 65.4% | 64.5% | NS |

| Mixed feeding | 29 (27.1%) | 40 (33.3%) | NS |

| Formula feeding | 8 (7.5%) | 3 (2.5%) | NS |

Variables expressed as median and interquartile range or percentage, where applicable. Statistical analysis was performed using non-parametric U of Mann Whitney, with a degree of significance at 0.05. Antenatal steroids: administration of corticosteroids (betamethasone) to induce lung maturation prior to preterm birth, and to reduce respiratory distress; 1 dose is considered partial, and 2 doses are considered a full course. Chorioamnionitis: Infection of the placenta and the amniotic fluid. Mixed feeding: Combination of breast milk and formula feeding. Advanced resuscitation: Need for intubation, cardiac compressions, or adrenaline in labour suite.

*Statistical significance.

Effect of probiotics on neurodevelopment

Of all the included patients, 86(78%) of infants receiving the probiotic combination, and 101(80%) infants of the non-probiotic cohort underwent a full 2-year review. There was a significant increase in survival without neurodevelopment impairment in the probiotic cohort at 24 months corrected age, RR 0.30 [0.16–0.58], NNT 3.85 [2.6–7.1]. The probiotic intervention also led to an improvement in overall Bayley-III Scale scores with a statistically significant difference in language with median scores of 94 [89–100] vs 88.5 [77–97] p = 0.006 respectively.

The degree of impairment was also less severe in the probiotic group (normal-mild vs moderate-severe, RR 0.22 [0.07–0.73]), NNT 8.1 [4.8–25.9]. The effect was still significant when comparing mild and moderate impairment with RR 0.37 [0.17–0.83] and RR 0.21 [0.05–0.94] subsequently. The overall incidence of severe neurodevelopment impairment was low in both groups, with no statistically significant differences. All neurodevelopment outcomes can be found in Table 2. Neurodevelopmental outcomes did not vary after analysing effect of preeclampsia and gestational age.

Table 2.

Neurodevelopmental outcomes at the 2-year analysis.

| Probiotics | No Probiotics | Relative risk [95% CI] | χ2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurodevelopment at 2 years | P < 0.001* | ||||

| Normal | 76/86 | 63/101 | |||

| Mild impairment | 7/86 | 22/101 | 0.37 [0.17–0.83] | 6.59 | p = 0.0159* |

| Moderate impairment | 2/86 | 11/101 | 0.21 [0.05–0.94] | 5.27 | p = 0.0407* |

| Severe impairment | 1/86 | 5/101 | 0.24 [0.03–1.97] | 2.15 | p = 0.1821 |

| Normal vs impaired | 0.30 [0.16–0.58] | 16.45 | p = 0.0003* | ||

| Normal-mild vs moderate-severe | 0.22 [0.07–0.73] | 7.77 | p = 0.0013* | ||

| Bayley-III | |||||

| Mental | 99 (95–104) | 95 (85–105) | p = 0.244 | ||

| Motor | 97 (91–103) | 97 (85–107) | p = 0.323 | ||

| Language | 94 (89–100) | 88.5 (77–97) | p = 0.006* | ||

*Statistical significance.

Secondary outcomes

When focusing on secondary outcomes (Table 3), probiotics did not affect incidence of NEC, overall mortality beyond 7 days of life, intraventricular haemorrhage, retinopathy of prematurity, nor periventricular leukomalacia.

Table 3.

Outcomes of the probiotic and non-probiotic group from birth up until the 2-year analysis.

| Outcome | Probiotics | No probiotics | Relative risk [95% CI] | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory distress syndrome | 43/109 | 45/124 | 1.007 (0.78–1.51) | P = 0.620 |

| Late-onset sepsis | 8/109 | 20/124 | 0.45 [0.21–0.99] | p = 0.040* |

| Intraventricular haemorrhage | 22/109 | 32/124 | 0.78 [0.49–1.27] | p = 0.311 |

| Retinopathy of prematurity | 28/103 | 38/116 | 0.84 [0.55–1.27] | p = 0.370 |

| Patent ductus arteriosus | 35/109 | 42/124 | 0.95 [0.66–1.37] | p = 0.776 |

| Necrotising enterocolitis | 3/109 | 3/124 | 1.14 [0.23–5.52] | p = 0.873 |

| Death beyond 7 days of life | 6/109 | 8/124 | 0.85 [0.30–2.38] | p = 0.761 |

| Periventricular leukomalacia | 6/103 | 2/116 | 3.38 [0.69–16.4] | p = 0.107 |

*Statistical significance.

There was a significant reduction in LOS, RR 0.45 [0.21–0.99], NNT 11.4 [5.8–200.7]. Additionally, there was a statistically significant reduction in the intensive care length of stay in the probiotic cohort 9 [6–15] vs 14 [7–41.5] days (p < 0.001). During the study, there were no cases of probiotic sepsis nor side effects.

Discussion

Recent literature demonstrated the beneficial effects of probiotics on NEC and LOS in very low birth weight neonates when used in the first weeks of life4–6,30. However, neurodevelopment benefits of probiotic use have not been clearly demonstrated21,31,32. The lack of effect of probiotics in neurodevelopment in previous studies (Table 4) could have resulted from varying factors.

Table 4.

Comparison of the previous existing studies analysing the use of probiotics and premature infant neurodevelopment.

| Study | Probiotic used | Neurodevelopment assessment | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jacobs et al.17 | Bifidobacterium infantis BB-02 96579 30 × 106, Streptococcus thermophilus TH-4 15957 350 × 106 and Bifidobacterium lactis BB-12 15954 350 × 106 (ABC Dophilus Probiotic Powder for Infants, Solgar USA) |

Composite of (at least one) at 2–5 years corrected age: Bayley-III < 77.5 or WPPSI-III < 2 standard deviations CP with GMFCS 2–5 Deafness requiring hearing aid or cochlear implant Blindness 6/60 better eye |

No difference in survival free of neurodevelopment impairment RR 1.01 [0.93–1.09]. Deafness lower in probiotic group (0.6% vs 3.4%) |

| Sari et al.18 | Lactibacillus sporogenes 350 × 106(DMG ITALIA SRL, Rome Italy) |

Composite outcome of at last one at 18–22 months corrected age: Bayley-II < 70 PDI < 70 Deafness needing hearing aids in both ears Blindness with no useful vision in either eye CP (abnormal one in 1 limb) |

There was no significant difference in growth and neurodevelopmental outcomes (p = 0.788) between the two groups |

| Romeo et al.19 | Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC 55730 1 × 108 or Lactobacillus rhamnosus ATCC 53103 6 × 109 | Hammersmith score of < 73 (suboptimal) at 12 months corrected age |

No statistical differences were observed in the incidence of suboptimal scores in both probiotic groups (p > 0.05). Statistically significant difference of suboptimal scores (p < 0.05) in the control group vs both probiotic groups |

| Chou et al.20 | Lactobacillus acidophilus 109 and Bifidobacterium infantis 109 (Swiss Serum and Vaccine Institute, Berne, Switzerland) |

Composite of (at least one) at 3 years corrected age: Bayley-II < 70 PDI < 70 Bilateral Blindness Hearing impairment > 55 dB in both ears CP requiring ambulatory assistance |

No significant differences in growth or in any of the neurodevelopmental and sensory outcomes between the 2 groups |

| Akar et al.21 | Lactobacillus reuteri 108 (Biogaia AB, Stockholm, Sweden) |

Composite outcome of at last one at 18–24 months corrected age: Bayley-II < 70 PDI < 70 Deafness needing hearing aids in both ears Blindness with no useful vision in either eye CP (abnormal tone in 1 limb) |

Neurodevelopment impairment did not differ between groups Probiotic 37/124 vs Non-probiotic 37/125 p = 0.96 |

WPPSI (Weschler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence), CP (Cerebral Palsy), PDI (Psychomotor development index.

For Jacobs et al.17, Sari et al.18, Romeo et al.19 and Akar et al.21 the use of different strains could explain their absence of benefits. As described, probiotics encompass a wide range of microorganisms that have completely different effects according to strain, dose and even site33. Different timing of the supplementation, as well as variations in gestational age or birth weight of the new-borns, could also influence the effectiveness of the treatment. Current evidence shows the best efficacy is achieved when combining probiotics3,4.

Our study is the first to show benefit with a significantly higher proportion of infants having normal neurodevelopment outcomes when given probiotics. Furthermore, there was a reduction in the length of stay in intensive care by almost half in these infants.

Traditionally, mild-moderate neurodevelopment impairment has seldom been considered in studies of premature outcomes7,17,18,20,21. Our study considered smaller degrees of impairment given their potential major impact on later quality of life. A broader spectrum of neurodevelopment evaluations could have highlighted a more subtle effect of probiotics, and impacted our results, compared to more restrictive criteria of other authors17,18,20,21. Moreover, mild and moderate neurodevelopment impairment are much more prevalent than severe impairment34.

Current literature suggests that neurocognitive disabilities manifest around 5–6 years of age8 and therefore 12-month evaluations could mask the true impact of probiotics. The inclusion up until 5 years corrected age of Jacobs et al.17 could help clarify such an effect. However, the loss of participants underpowered their study. Likewise, the lack of statistical power in the study by Chou et al.20 could explain the differences encountered with our study, despite the use of similar combinations of probiotics.

Finally, differing inclusion criteria with varying birthweights and gestation, also play a role in the findings of each study.

In short, key strong points of our study are the use of a probiotic combination with well-established benefits in preterm neonates5,6,35, the extensive follow-up and evaluation programme of premature infants at risk, and a broader analysis of neurodevelopmental outcomes. Unfortunately, the lack of randomisation and the sequential nature of the study could introduce bias in the results presented. Also, establishing an analysis at 24 months corrected age could mask the full impact of probiotics on neurodevelopment. Although there was higher preeclampsia in the probiotic group, and possible exposure to magnesium sulphate –a widely used treatment for maternal hypertension and proposed therapy for improving neurodevelopment outcome36-, once adjusted by maternal hypertension differences in neurodevelopment impairment were sustained between groups. An overall low incidence of severe neurodevelopment impairment in both our study groups could have made achieving statistical significance difficult. Nonetheless, the reduction of severe cases of neurodevelopment impairment in the probiotic group compared to the control group has clinical relevance. Lastly, despite borderline statistically significant differences in gestational age between groups, we considered a difference of 2 days in gestational age not to have clinical significance.

When centring on the explanations of the effect of probiotics on the neurodevelopment, the existence of the brain-gut axis has been proven to be of paramount importance9–11. Dysbiosis can contribute to the increase of gut permeability causing a rise in bacterial translocation and LPS, directly implicated in chronic inflammation, leading to an upscaling of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukine-6 and tumour necrosis factor α and subsequent cortisol activation10,11,13. Lactobacillus helveticus combined with Bifidobacterium longum have shown a decrease in hippocampal apoptosis in rats exposed to LPS37, as well as reducing serum cortisol -main stress hormone- levels in humans and rats38. Bifodobacterium bifidum and Lactobacillus salivarius administered in the prenatal period, decreased LPS and impacted foetal gut microbiota39. Cortisol has been found to influence the secretion of BDNF. Exposure to postnatal steroids in premature infants has been linked to an increased risk of cerebral palsy and neurobehavioural changes40. As pointed out by Bailey et al.41, stress can induce dysbiosis and a reduction in native Lactobacillus in human gut, which is then related to an increase in interleukin-6 and posterior anxiety-like patterns of behaviour. Studies in mice have shown that the correction of dysbiosis in adulthood did not normalise behavioural patterns and neuroregulation as it did if corrected in early stages of life42. Therefore, correction should be within this critical window to ensure the long-term benefits in neurodevelopmental programming, thus reinforcing the need for probiotic implementation early in the timeline of the developing premature brain.

The study of Kim et al.43 showed the ability of Bifidobacterium bifidum BGN4 to increase BDNF expression and reverse apoptosis in aging mouse models. As proposed by Liu et al.16, BDNF could have a major role in Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder (ADHD) and other psychiatric disorders, which, as reflected in the EPIC study group, premature infants have a higher risk of manifesting44. Additionally, premature infants have lower numbers of Bifidobacterium bifidum compared to term neonates45. Although it should be considered cautiously, the study of Wang et al.46 hinted that during the administration of Bifidobacterium bifidum (Bf-688) children with ADHD showed improvement in symptoms. The administration of Lactobacillus rhamnosus (JB-1) to mice induced a changed expression of GABAB1b and GABAA⍺2 receptor subunits mRNA47. Interestingly, vagotomy impeded the effects of the probiotic on the GABAA⍺2 subunit, enhancing the theory that the vagus nerve is important in the brain-gut axis, stress and anxiety.

A reduction in the total days of intensive care, seen in the probiotic cohort, and transfer to a lower level of care, with a reduction of painful procedures and overall stress, could also contribute to better neurobehavioural development48.

Alcon-Giner et al. have published a study on the metabolome of premature infants supplemented with the same mixture used in our study. They showed that the supplemented preterm infants had a lower abundance of potential pathobionts, more typical of the preterm gut, which have previously been linked to NEC and LOS49. Furthermore, the B. bifidum Infloran® strain was able to metabolise specific human milk oligosaccharides. This fact not only facilitates digestion and improves nutrition in the preterm neonates, but the human milk oligosaccharide degradation by-products (acetate and lactate) inhibit the growth of some pathogenic bacteria, reinforce the intestinal barrier, and have anti-inflammatory effects. Therefore, hinting the possible neuroprotective properties for preterm neonates. The authors also observed that B. bifidum Infloran® strain was able to persist in the gut for more than 50 days after the end of treatment.

On the other hand, the reduction in late-onset sepsis by probiotics was concordant with previous findings4,30. Said outcome could also help explain the effects in neurodevelopment. Studies in rat models have manifested that infection can cause alterations in the expression of BDNF. Probiotics such as Bifidobacterium longum can help palliate such an effect and restore BDNF expression10. Moreover, the use of Lactobacillus plantarum ZLP001 was shown to combat the increase in gut permeability caused by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli diminishing proinflammatory cytokines in piglets50. Exposure to antibiotics is well known to diminish beneficial microbiota such as Lactobacillus and cause dysbiosis. Hence, a reduction in the number of septic episodes would decrease the use of antibiotics. However, the rise in antibiotic stewardship might have contributed to decrease initial antibiotic exposure, affecting our results.

Finally, although the probiotic combination used has been shown to reduce NEC51, our lack of statistical differences in NEC could be justified by a traditionally low incidence in our unit (yearly incidence of NEC < 3%), combined with a high use of expressed breast milk and donor milk, with a very low prevalence of formula-exposed preterm neonates. There has been extensive research in the use of breast milk for the reduction of NEC. As shown by a recent meta-analysis52, exclusive breast feeding is superior to formula and mixed feeding in randomised controlled trials.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to prove the benefit of a probiotic mixture in premature infant neurodevelopment. However, since the bigger impact of prematurity in neurodevelopment is truly shown in later stages of life, further studies are needed in older infants to understand the full scope of said intervention, opening a new field of studies in probiotics and the premature infant. It would also be interesting to conduct studies with postbiotics in this area. Postbiotics not only have more advantages than probiotics when used in these vulnerable populations but also have proven safety, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulating and antimicrobial action. These characteristics are of great help in very preterm infants, where intestinal permeability and inflammation is evident53.

Conclusions

The prophylactic administration of Bifidobacterium bifidum NCDO2203 combined with Lactobacillus acidophilus NCDO1748 contributed to improve neurodevelopmental outcome and reduce LOS in neonates born at less than 32 weeks and less than 1500 g. More clinical trials would be needed to corroborate these findings and to explain the mechanisms by which reversing dysbiosis may improve neurological outcomes.

Abbreviations

- ADHD

Attention deficit and hyperactive disorder

- BDNF

Brain derived neurotrophic factor

- CP

Cerebral Palsy

- LOS

Late-onset sepsis

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- NEC

Necrotising enterocolitis

- NNT

Numbers needed to treat

- PDI

Psychomotor development index

- RR

Relative risk

- WPPSI

Weschler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence

Author contributions

B.J.B. contributed to conception and design, acquisition of data, and analysis and interpretation of data. Additionally contributed in drafting the article and final approval of the version to be published. G.S. contributed to conception and design, acquisition of data and supervision of study. Additionally contributed in drafting the article and critical review together with the final approval of the version to be published. L.H. contributed to acquisition of data and analysis and interpretation of data. Final approval of the version to be published was also undertaken. V.A. contributed to conception and design of the study and interpretation of data. Additionally contributed in drafting and reviewing the article with the approval of the final version to be published. E.N. contributed to conception and design of the study, as well as supervision of the study. Additionally contributed to drafting and reviewing the article with final approval of version to be published. O.G. contributed to conception and design of the study and reviewed critically for intellectual content of article. He also gave his approval of the final version to be published. J.F. contributed to acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation of said data. He also provided critical review for intellectual content and a final approval of the version to be published.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due patient confidentiality but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Benjamin James Baucells and Giorgia Sebastiani.

References

- 1.Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations and World Health Organization . Health and Nutritional Properties of Probiotics in Food Including Powder Milk with Live Lactic Acid Bacteria. Word Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mai V, Young CM, Ukhanova M, et al. Fecal microbiota in premature infants prior to necrotizing enterocolitis. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(6):e20647. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Navarro-Tapia E, Sebastiani G, Sailer S, et al. Probiotic supplementation during the perinatal and infant period: Effects on gut dysbiosis and disease. Nutrients. 2020;12(8):2243. doi: 10.3390/nu12082243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baucells BJ, MercadalHally M, Álvarez Sánchez AT, Figueras AJ. Probiotic associations in the prevention of necrotising enterocolitis and the reduction of late-onset sepsis and neonatal mortality in preterm infants under 1,500g: A systematic review. An Pediatr. 2016;85(5):247–255. doi: 10.1016/j.anpedi.2015.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas JP, Raine T, Reddy S, Belteki G. Probiotics for the prevention of necrotising enterocolitis in very low-birth-weight infants: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Acta Paediatr. 2017;106(11):1729–1741. doi: 10.1111/apa.13902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharif S, Meader N, Oddie SJ, Rojas-Reyes MX, McGuire W. Probiotics to prevent necrotising enterocolitis in very preterm or very low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020;2020(10):5496. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005496.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wood NS, Marlow N, Costeloe K, Gibson AT, Wilkinson AR. Neurologic and developmental disability after extremely preterm birth. EPICure Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000;343(6):378–384. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008103430601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allotey J, Zamora J, Cheong-See F, et al. Cognitive, motor, behavioural and academic performances of children born preterm: A meta-analysis and systematic review involving 64 061 children. BJOG. 2018;125(1):16–25. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hortensius LM, Van Elburg RM, Nijboer CH, Benders MJNL, De Theije CGM. Postnatal nutrition to improve brain development in the preterm infant: A systematic review from bench to bedside. Front. Physiol. 2019;10:961. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cryan JF, O’Mahony SM. The microbiome-gut-brain axis: From bowel to behavior. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2011;23(3):187–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang I, Corwin EJ, Brennan PA, Jordan S, Murphy JR, Dunlop A. The infant microbiome: Implications for infant health and neurocognitive development. Nurs. Res. 2016;65(1):76–88. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Europe ILSI. ILSI Europe Concise Monograph on Nutrition and Immunity in Man. 2. ILSI Europe; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang EJ, Reichardt LF. Neurotrophins: Roles in neuronal development and function. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;24:677–736. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ranuh R, Athiyyah AF, Darma A, et al. Effect of the probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum IS-10506 on BDNF and 5HT stimulation: A role of intestinal microbiota on the gut-brain axis. Iran J. Microbiol. 2019;11(2):145–150. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nikolaou KE, Malamitsi-Puchner A, Boutsikou T, et al. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. Blackwell Publishing Inc.; 2006. The varying patterns of neurotrophin changes in the perinatal period; pp. 426–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu DY, Shen XM, Yuan FF, et al. The physiology of BDNF and its relationship with ADHD. Mol. Neurobiol. 2015;52(3):1467–1476. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8956-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobs SE, Hickey L, Donath S, et al. Probiotics, prematurity and neurodevelopment: Follow-up of a randomised trial. BMJ Paediatr. Open. 2017 doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2017-000176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sari F, Eras Z, Dizdar E, et al. Do oral probiotics affect growth and neurodevelopmental outcomes in very low-birth-weight preterm infants? Am. J. Perinatol. 2012;29(8):579–585. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1311981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romeo MG, Romeo DM, Trovato L, et al. Role of probiotics in the prevention of the enteric colonization by Candida in preterm newborns: Incidence of late-onset sepsis and neurological outcome. J. Perinatol. 2011;31(1):63–69. doi: 10.1038/jp.2010.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chou IC, Kuo HT, Chang JS, et al. Lack of effects of oral probiotics on growth and neurodevelopmental outcomes in preterm very low birth weight infants. J. Pediatr. 2010;156(3):393–396. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akar M, Eras Z, Oncel MY, et al. Impact of oral probiotics on neurodevelopmental outcomes in preterm infants. J. Maternal-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017;30(4):411–415. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2016.1174683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hickey L, Garland SM, Jacobs SE, O’Donnell CPF, Tabrizi SN. Cross-colonization of infants with probiotic organisms in a neonatal unit. J. Hosp. Infect. 2014;88(4):226–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Samuels N, Van De Graaf R, Been JV, et al. Necrotising enterocolitis and mortality in preterm infants after introduction of probiotics: A quasi-experimental study. Sci Rep. 2016;6:31643. doi: 10.1038/srep31643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dupont WD, Plummer WD. Power and sample size calculations. A review and computer program. Control Clin. Trials. 1990;11(2):116–128. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(90)90005-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim H, Kim JE, Kim Y, Hong SW, Jung H. Slow advancement of the endotracheal tube during fiberoptic-guided tracheal intubation reduces the severity of postoperative sore throat. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):7709. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-34879-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sánchez-Liñan N, Pérez-Rueda A, Parrón-Carreño T, Nievas-Soriano BJ, Castro-Luna G. Evaluation of biometric formulas in the calculation of intraocular lens according to axial length and type of the lens. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):4678. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-31970-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development. 3. Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jimenez R, Figueras J, Botet F. Neonatología: Procedimientos Diagnósticos y Terapéuticos. 2. Ed. Espaxs; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kliegman RM, Walsh MC. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis: Pathogenesis, classification, and spectrum of illness. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. 1987;17(4):213–288. doi: 10.1016/0045-9380(87)90031-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deshpande G, Jape G, Rao S, Patole S. Benefits of probiotics in preterm neonates in low-income and medium-income countries: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open. 2017;7(12):e017638. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agrawal S, Pestell CF, Granich J, et al. Difficulties in developmental follow-up of preterm neonates in a randomised-controlled trial of Bifidobacterium breve M16-V: Experience from Western Australia. Early Hum. Dev. 2020;151:105165. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2020.105165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Firmansyah A, Dwipoerwantoro PG, Kadim M, et al. Improved growth of toddlers fed a milk containing synbiotics. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011;20(1):69–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shanahan F. Molecular mechanisms of probiotic action: It’s all in the strains! Gut. 2011;60(8):1026–1027. doi: 10.1136/gut.2011.241026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Serenius F, Ewald U, Farooqi A, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes among extremely preterm infants 65 years after active perinatal care in Sweden. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(10):954. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meyer MP, Chow SSW, Alsweiler J, et al. Probiotics for prevention of severe necrotizing enterocolitis: Experience of New Zealand neonatal intensive care units. Front. Pediatr. 2020;8:119. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.00119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shepherd E, Salam RA, Manhas D, et al. Antenatal magnesium sulphate and adverse neonatal outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2019;16(12):e1002988. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mohammadi G, Dargahi L, Naserpour T, et al. Probiotic mixture of Lactobacillus helveticus R0052 and Bifidobacterium longum R0175 attenuates hippocampal apoptosis induced by lipopolysaccharide in rats. Int. Microbiol. 2019;22(3):317–323. doi: 10.1007/s10123-018-00051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Messaoudi M, Lalonde R, Violle N, et al. Assessment of psychotropic-like properties of a probiotic formulation (Lactobacillus helveticus R0052 and Bifidobacterium longum R0175) in rats and human subjects. Br. J. Nutr. 2011;105(5):755–764. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510004319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kar F, Hacioglu C, Kar E, Donmez DB, Kanbak G. Probiotics ameliorates LPS induced neuroinflammation injury on Aβ 1–42, APP, γ-β secretase and BDNF levels in maternal gut microbiota and fetal neurodevelopment processes. Metab. Brain Dis. 2022;37(5):1387–1399. doi: 10.1007/s11011-022-00964-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Halliday HL. Update on postnatal steroids. Neonatology. 2017;111(4):415–422. doi: 10.1159/000458460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bailey MT, Dowd SE, Galley JD, Hufnagle AR, Allen RG, Lyte M. Exposure to a social stressor alters the structure of the intestinal microbiota: Implications for stressor-induced immunomodulation. Brain Behav. Immun. 2011;25(3):397–407. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heijtz RD, Wang S, Anuar F, et al. Normal gut microbiota modulates brain development and behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108(7):3047–3052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010529108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim H, Shin J, Kim S, et al. Bifidobacterium bifidum BGN4 and Bifidobacterium longum BORI promotes neuronal rejuvenation in aged mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2022;603:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2022.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson S, Hollis C, Kochhar P, Hennessy E, Wolke D, Marlow N. Psychiatric disorders in extremely preterm children: Longitudinal finding at age 11 years in the EPICure study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2010;49(5):453–63.e1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saturio S, Nogacka AM, Suárez M, et al. Early-life development of the bifidobacterial community in the infant gut. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22(7):3382. doi: 10.3390/ijms22073382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang LJ, Yang CY, Kuo HC, Chou WJ, Tsai CS, Lee SY. Effect of Bifidobacterium bifidum on clinical characteristics and gut microbiota in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Pers. Med. 2022;12(2):227. doi: 10.3390/jpm12020227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bravo JA, Forsythe P, Chew MV, et al. Ingestion of Lactobacillus strain regulates emotional behavior and central GABA receptor expression in a mouse via the vagus nerve. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108(38):16050–16055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102999108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vinall J, Miller SP, Bjornson BH, et al. Invasive procedures in preterm children: Brain and cognitive development at school age. Pediatrics. 2014;133(3):412–421. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alcon-Giner C, Dalby MJ, Caim S, et al. Microbiota supplementation with bifidobacterium and lactobacillus modifies the preterm infant gut microbiota and metabolome: An observational study. Cell Rep. Med. 2020;1(5):100077. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2020.100077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang J, Ji H, Wang S, et al. Probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum promotes intestinal barrier function by strengthening the epithelium and modulating gut microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:1953. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Uberos J, Campos-Martinez A, Fernandez-Marín E, Millan IC, Lopez AR, Blanca-Jover E. Effectiveness of two probiotics in preventing necrotising enterocolitis in a cohort of very-low-birth-weight premature new-borns. Benef. Microbes. 2022;13(1):25–31. doi: 10.3920/BM2021.0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Altobelli E, Angeletti PM, Verrotti A, Petrocelli R. The impact of human milk on necrotizing enterocolitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2020;12(5):1322. doi: 10.3390/nu12051322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morniroli D, Vizzari G, Consales A, Mosca F, Giannì ML. Postbiotic supplementation for children and newborn’s health. Nutrients. 2021;13(3):781. doi: 10.3390/nu13030781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due patient confidentiality but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.