Abstract

Introduction

Moyamoya disease (MMD) is a chronic cerebrovascular steno-occlusive disease of largely unknown etiology. Variants in the RNF213 gene are strongly associated with MMD in East-Asia. In MMD patients of Northern-European origin, no predominant susceptibility variants have been identified so far.

Research question

Are there specific candidate genes associated with MMD of Northern-European origin, including the known RNF213 gene? Can we establish a hypothesis for MMD phenotype and associated genetic variants identified for further research?

Material and methods

Adult patients of Northern-European origin, treated surgically for MMD at Oslo University Hospital between October 2018 to January 2019 were asked to participate. WES was performed, with subsequent bioinformatic analysis and variant filtering. The selected candidate genes were either previously reported in MMD or known to be involved in angiogenesis. The variant filtering was based on variant type, location, population frequency, and predicted impact on protein function.

Results

Analysis of WES data revealed nine variants of interest in eight genes. Five of those encode proteins involved in nitric oxide (NO) metabolism: NOS3, NR4A3, ITGAV, GRB7 and AGXT2. In the AGXT2 gene, a de novo variant was detected, not previously described in MMD. None harboured the p.R4810K missense variant in the RNF213 gene known to be associated with MMD in East-Asian patients.

Discussion and conclusion

Our findings suggest a role for NO regulation pathways in Northern-European MMD and introduce AGXT2 as a new susceptibility gene. This pilot study warrants replication in larger patient cohorts and further functional investigations.

Keywords: Moyamoya, Stroke, Nitric oxide, Gene, RNF213, Whole exome sequencing

Highlights

-

•

In this Norwegian pilot study, whole exome sequencing was performed and variants in eight candidate genes identified.

-

•

Five of these genes are involved in NO regulation. The AGXT2 gene, was identified as a de novo variant.

-

•

Identification of a de novo variant in AGXT2 supports the hypothesis of NO pathway dysregulation as a contributor in MMD.

-

•

Identification of five other rare gene variants in our cases, in NR4A3, ITGAV, GRB7, NOS3, are all involved in NO metabolism.

-

•

This pilot study proposes a role of NO metabolism in MMD that should be further assessed in larger patient cohorts.

Abbreviations and acronyms:

- ADMA

Asymmetric dimethylarginine

- AGXT2

Alanine--Glyoxylate Aminotransferase 2

- CADD

Combined Annotation-Dependent Depletion

- CNV

Copy number variant

- DIAPH1 –

Diaphanous Related Formin 1

- GATK

Genome Analysis Toolkit

- GRB7

Growth Factor Receptor Bound Protein 7

- GUCY1A3

Guanylate cyclase soluble subunit alpha-3

- IEL –

Internal elastic lamina

- ITGAV

Integrin Subunit Alpha V

- ITGB3 –

Integrin Subunit Beta 3

- MMD –

Moyamoya disease

- NO –

Nitric oxide

- NOS3

Nitric Oxide Synthase 3

- NR4A3

Nuclear Receptor Subfamily 4 Group A Member 3

- PI3K

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- RNF213

Ring finger protein 213

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- SDMA –

Symmetric dimethylarginine

- SGC

Soluble guanylyl cyclase

- PKB –

Protein kinase B

- VEGF –

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- VSMC –

Vascular smooth muscle cell

- WES

Whole-exome sequencing

1. Introduction

Moyamoya disease (MMD) is a rare cerebrovascular condition characterized by progressive stenosis of the distal internal carotid artery and its proximal branches, with subsequent development of a compensatory collateral network at the base of the brain (Suzuki and Takaku, 1969). Disease incidence is higher in Japan, Korea and China than in Europe and North America (Kleinloog et al., 2012). Differences in disease susceptibility by ethnic background are conserved after emigration (Uchino et al., 2005). One study of 15 Japanese families with three or more members affected by MMD suggests an autosomal mode of inheritance with incomplete penetrance of familial MMD (Mineharu et al., 2006). This suggests a key role of genetic factors in MMD development. However, there is limited data on epidemiology and genetic predisposition in European patients with MMD, with only a few case reports describing familial cases (Birkeland and Lauritsen, 2018; Hever et al., 2015; Kraemer et al., 2012; Grangeon et al., 2019). The appearance of both sporadic and familial MMD cases suggests a complex mode of inheritance. Some genetic variants have more impact than others. In East-Asian populations, variants in the RNF213 gene confer a strong susceptibility to develop disease (Liu et al., 2011; Kamada et al., 2011). In particular, the missense variant p.R4810K (NM_001256071.3: c.14429G > A) is strongly associated with MMD (Guey et al., 2015). However, this association has not been replicated in other populations, as the p.R4810K variant is only present in Asian populations (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/variant/17-78358945-G-A) (Uchino et al., 2005; Ma et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2010, 2013a; Cecchi et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2013). Other rare RNF213 missense variants have been identified in Caucasian MMD populations, suggesting that variants in the RNF213 gene might confer some susceptibility, also in non-Asian patients (Guey et al., 2017a; Kobayashi et al., 2016; Zanoni et al., 2023). However, no single predominant susceptibility variant has been identified so far. Attempts have been made to identify variants responsible for the major effects in familial MMD, but findings have not been replicable (Wang et al., 2020). A genome wide association study (GWAS) was unsuccessful in identifying a predominant susceptibility variant for Caucasian MMD in contrast to the strong association of the variant p.R4810K in the RNF213 gene in East-Asian populations (Liu et al., 2013a).

Based on the vast heterogeneity of reported findings in MMD patients of other than East-Asian origin, the aim of our pilot study was to establish an analysis strategy and genetically characterize MMD by WES in patients of Northern-European origin.

2. Methods

2.1. Ethics

The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee of South Eastern Norway (No. 2018/1377) and written informed consent was obtained from all study participants regarding publication of their data.

2.2. Patient recruitment

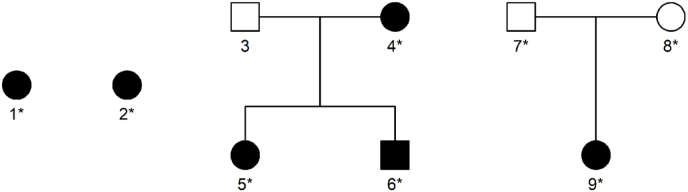

In this pilot study, adult patients of Northern-European origin, treated surgically for MMD at Oslo University Hospital (OUH) in the recruitment period (October 2018 to January 2019) were consecutively included. In familial cases, affected members were also asked to participate, and in one of the sporadic cases, healthy parents were included. Blood samples were drawn from all six patients and the healthy parents of one sporadic patient. The family structures of the collected patients are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Overview of patients and families included in this study. Squares = men; circles = women. Filled symbols indicate MMD. Starred individuals (∗) were subjected to exome sequencing.

All patients treated at OUH were thoroughly assessed at baseline, including medical history, family history, lifestyle factors, neurological examination, neuropsychological testing, laboratory tests and imaging. Symptomatic patients with hypoperfusion on MRI were offered surgical treatment with a combined direct and indirect revascularization. Diagnosis of MMD was based on international guidelines (Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment, 2012).

2.3. Whole exome sequencing

Whole exome sequencing (WES) was performed in all six patients and in two unaffected parents. Exome capture was done using the SureSelectXT V5 kit (Agilent, Böblingen, Germany), following the supplier's protocol for 3 μg DNA samples (Technologies, 2017). Paired end sequencing with read lengths of 150 bp was performed with Illumina HiSeq3000 technology (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA).

2.4. Bioinformatic analysis and variant filtering

The sequences were aligned to the reference human genome (hg19) with bwa mem (v0.7.12) (Li and Durbin, 2010). The alignments were refined by the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK, v3.3) and PCR duplicates were marked by Picard (v1.124) (McKenna et al., 2010; Van der Auwera et al., 2013). Variant calling was performed with the Haplotype Caller feature of GATK (v3.3), applying joint calling for related individuals. The variants were annotated with ANNOVAR (v2017Jul16) (Wang et al., 2010) while filtering and downstream analysis was done in FILTUS (Vigeland et al., 2016).

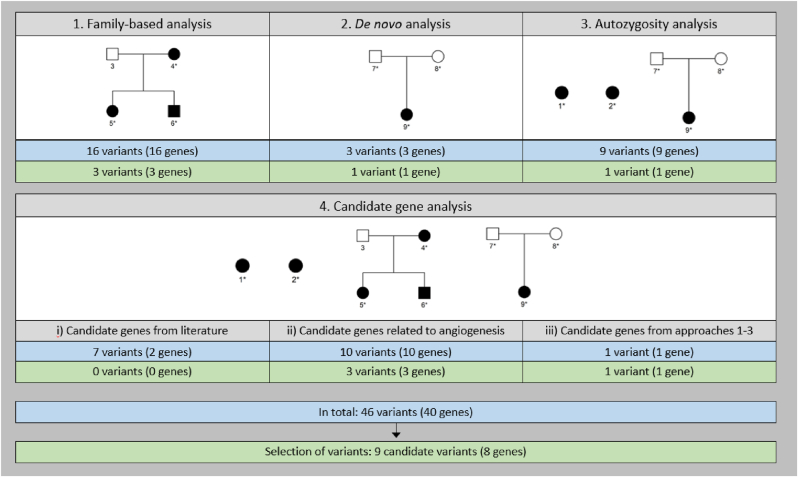

2.5. Analysis strategies for the identification of genetic variants associated with MMD

Our analysis strategy was tailored to each patient, according to family structure and sample availability. The four different approaches are summarized in Table 1 and illustrated in Fig. 2. Approach 1: a family-based analysis was applied for the three patients in the same family, applying a dominant model, i.e., identification of all joint heterozygous variants. Approach 2: de novo mutation analysis was performed for the patient with available parental samples. Approach 3: autozygous regions were identified in all three non-familial cases, using the AutEx algorithm of the FILTUS program. Though consanguinity was not suspected in any of the patients, this analysis was included to identify potential cryptic consanguinity, i.e., homozygous regions resulting from unknown distant parental relationships. Approach 4: Analysis of candidate genes was performed in all patients. We applied three candidate gene lists, based on three sources: i) 27 candidate genes previously reported in MMD (see Supplementary Table 2); ii) 147 genes known to be involved in angiogenesis, i.e., a selection based on gene lists made for QIAGEN array (complete list in Supplementary Table 3); and iii) the genes in which variants were identified by analysis approach 1, 2 or 3 were re-analysed in all patients using the more liberal filters for approach 4 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Filtering strategies for identification of genetic variants associated with MMD.

| Analysis | Patients | Region | Depth | Allele frequency | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Family-based, dominant model | 4, 5, 6 | Exon/splice site | >5 | <0.0001 | Strict frequency filter justified by dominant disease model |

| 2. De novo | 9 | Exon/splice site | >9 | <0.01 | Higher depth to avoid false positives. Mutation rate set to 10−8 |

| 3. Autozygosity | 1, 2, 9 | Exon/splice site | >5 | <0.015 | Relaxed frequency filter justified by autozygous disease model |

| 4. Candidate genes | All patients | Exon/splice site | >5 | <0.01 | Selected genes from the literature and analyses 1-3 |

Fig. 2.

Overview of analysis approaches and variant filtering. Blue boxes are the results from the filtering with the cut-offs given in Table 1, whereas the green boxes are the results from discretionary selection of variant after review of literature and results from in silico prediction tools. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

After filtering and analysing in FILTUS, a discretionary review of the candidate variants was performed based on literature review of the genes combined with predicted impact on protein function using several prediction tools including GERP++ (Davydov et al., 2010), SIFT (Kumar et al., 2009), PolyPhen (v2) (Adzhubei et al., 2013), LRT (Chun and Fay, 2009), MutationTaster (Schwarz et al., 2010), MutationAssessor (Reva et al., 2011), FATHMM-XF (Rogers et al., 2018), PROVEAN (Choi and Chan, 2015) and the CADD score (Rentzsch et al., 2019; Kircher et al., 2014).

3. Results

3.1. Study cohort

Six adult patients of Northern-European origin, diagnosed with MMD were included. The study cohort consisted of three unrelated sporadic cases and one family with MMD. The family included three confirmed MMD family members: one mother and two adult children (Fig. 1). Blood samples were obtained from all six patients and from the two unaffected parents, i.e., 8 blood samples in total.

Five out of six patients were female, and mean age was 33 years (range 23–56). All patients had experienced at least one ischemic stroke, whereas the three familial patients had multiple TIAs or strokes. Headaches and fatigue were the most common chronic symptoms, reported in four of the patients. Five of the patients received both medical and surgical treatment with revascularization, while one patient had refused treatment.

3.2. Genetic analysis

The results of genetic analyses and filtering are summarized in Fig. 2. After WES, analysis approaches 1–3 resulted in 28 genes of interest: 16 variants in 16 genes of interest from approach 1 (family-based); three variants in three genes from approach 2 (de novo analysis) and 9 variants in 9 genes resided in an autozygous region in individual 1 (approach 3, autozygous regions). Next, analysis approach 4, the candidate gene analysis, yielded variants in 13 genes: 7 variants in 2 genes (gene list based on literature); 10 variants in 10 genes (list of candidate genes involved in angiogenesis), and finally only one variant was identified in candidate genes included from analyses 1–3. In total, we identified 46 variants in 40 genes of interest. Of note, one gene (NR4A3) is listed in both approach 1 and in approach 4 iii). A discretionary review of these variants narrowed the list to nine variants in eight genes (Table 2). Of these eight genes, five encode proteins involved in NO metabolism: NOS3, NR4A3, ITGAV, GRB7 and AGXT2. A list of the 32 genes not selected by the last discretionary selection can be found in Supplementary Table 4.

Table 2.

Genetic variants identified in the study cohort.

| Gene | Variant | Frequency (gnomAD, popmax) | Identification method | CADD score | Patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NR4A3 | NM_006981: c.C872T; p.Thr291Met | 0.00006 | Family-based analysis | 24.8 | 4, 5, 6 |

| NR4A3 | NM_006981: c.C1578G; p.Ser526Arg | 0.00014 | Candidate gene approach (Re-analysis of genes identified in approaches 1–3) | 16.01 | 2 |

| PDZRN3 | NM_001303139: c.C1362G; p.Ser454Arg | Not previously observed | Family-based analysis | 25.6 | 4, 5, 6 |

| TNFAIP2 | NM_006291: c.C1240G; p.Gln414Glu | Not previously observed | Family-based analysis | 12.09 | 4, 5, 6 |

| AGXT2 | NM_001306173: c.C703T; p.Pro235Ser | Not previously observed | De novo analysis | 13.9 | 9 |

| NOS3 | NM_001160109: c.G1684A; p.Glu562Lys | 0.00003 | Candidate gene approach (angiogenesis gene) | 33 | 1 |

| ITGAV | NM_001145000: c.A1313T; p.Asn438Ile | Not previously observed | Candidate gene approach (angiogenesis gene) | 26.8 | 1 |

| FGR3 | NM_000142: c.A1136G; p.Tyr379Cys | Not previously observed | Candidate gene approach (angiogenesis gene) | 25.3 | 2 |

| GBR7 | NM_001030002: c.G869A; p.Arg290His | 0.00089 | Autozygous region | 32 | 1 |

4. Discussion

In this study, whole exome sequencing in six MMD patients and two healthy parents of Northern-European origin was performed, including different analysis strategies (Table 1). We identified variants in eight candidate genes (Table 2). Remarkably, five of these genes are involved in NO regulation, where one gene, the AGXT2 gene, was identified as a de novo variant in one of the sporadic cases. AGXT2 has not been previously described as a gene that confers increased susceptibility for MMD, and the identification of this gene through an unbiased analysis (de novo analysis) thus corroborates the hypothesis of NO pathway involvement in MMD pathophysiology.

Several variants of the RNF213 gene are strongly associated with MMD in East-Asia (Liu et al., 2011; Kamada et al., 2011; Ma et al., 2013) and rare missense variants have been reported in non-Asian MMD (Zanoni et al., 2023; Guey et al., 2017b). However, we did not identify the p.R4810K variant of the RNF213 gene in any of the patients, nor any other potential risk variants in this gene. This finding is in line with previous reports on non-Asian MMD, not confirming predominant susceptibility variants (Cecchi et al., 2014; Guey et al., 2017a; Liu et al., 2013b).

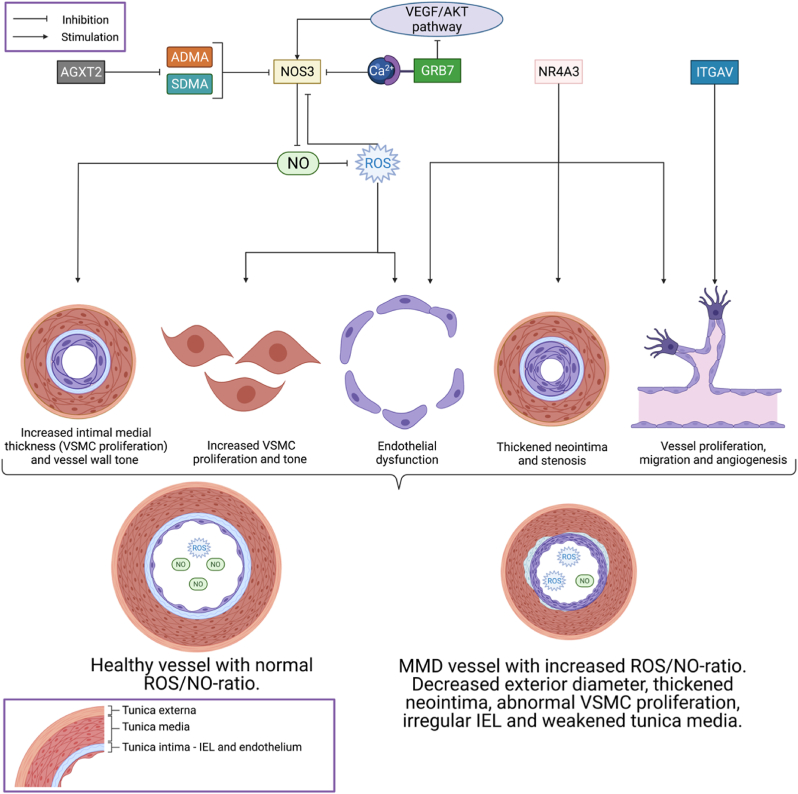

The eight identified candidate genes were selected based on rare frequencies in the population, and prediction of pathogenic effects on protein function, including the CADD score (Rentzsch et al., 2019). Five of the identified candidate genes may influence endothelial NO regulation (Fig. 3). NO-dependent pathways are crucial for healthy angiogenesis, and NO plays a protective role as an endogenous vasodilator by regulating normal blood vessel tone and diameter (Rochette et al., 2013). Reduced NO bioavailability in the endothelium results in decreased vasodilation by reduced vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) relaxation (Davignon and Ganz, 2004). Loss of NO triggers VSMC proliferation and migration, leading to vessel stenosis (Northcott et al., 2017).

Fig. 3.

Suggested involvement of NR4A3, AGXT2, NOS3, ITGAV and GRB7 in the development of vessel wall pathology and angiogenesis in moyamoya disease. (Abbreviations: VSMC = vascular smooth muscle cell; IEL = internal elastic lamina; MMD = moyamoya disease; NO = Nitric oxide; ROS = reactive oxygen species.) Created with BioRender.com.

Endothelial-derived NO is crucial for angiogenesis, suggesting that variants in genes encoding proteins involved in the regulation of NO levels are plausible candidates for MMD pathology. Moreover, some evidence of dysfunctional NO regulation in MMD patients exists: Biallelic variants in the gene GUCY1A3 encoding a NO receptor have been shown to cause MMD associated with achalasia in European patients (Herve et al., 2014; Wallace et al., 2016), and recently, biallelic variants in NOS3 were identified in two consanguineous probands with moyamoya angiopathy (Guey et al., 2023). NO metabolites are further elevated in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with MMD (Noda et al., 2000).

NO is produced by NO-synthases (NOS) (Rochette et al., 2013), and NOS3 produces NO in the endothelium. Variants in the NOS3 gene in MMD patients may thus represent a possible link to disease phenotype. It has been shown that imbalanced NOS3 synthesis leads to endothelial dysfunction by increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Rochette et al., 2013). Increased ROS levels then lead to oxidative stress in cells (Rochette et al., 2013; Alonso et al., 2018). Moreover, ROS can oxidize a cofactor of NOS3, which again prevents the formation of the NOS3 dimer (Rochette et al., 2013). NOS3 then contributes to a further increased ROS production, thus creating a vicious circle (Rochette et al., 2013).

NOS3 is also activated by an elevation in intracellular calcium (Andrew and Mayer, 1999). Through this signalling pathway, mutations in Grb7 may cause endothelial dysfunction through reduced angiogenetic activity both through changes in intracellular calcium signalling and the VEGF/Akt (PKB)/NO pathway (Andrew and Mayer, 1999; Sahlberg et al., 2013).

The naturally occurring amino acids ADMA and SDMA, are endogenous inhibitors of NOS and can inhibit NOS competitively (Rees et al., 1990; Faraci et al., 1995) or partly by reducing substrate availability (Boger et al., 2000; Closs et al., 1997). AGXT2 metabolizes both ADMA and SDMA (MacAllister et al., 1996; Seppala et al., 2016), and lower AGXT2 activity is associated with higher risk for cardiovascular disease and increased carotid intimal medial thickness (Yoshino et al., 2014). Reduced AGXT2 activity may lower the NO-producing activity of NOS3, through a higher concentration of ADMA and SDMA. Elevated serum levels of ADMA and SDMA have been shown to reduce NO bioavailability leading to endothelial dysfunction (Sitia et al., 2010; Tain et al., 2010; Vallance et al., 1992; Boger et al., 2009; Feliers et al., 2015) and intimal hyperplasia (Masuda et al., 1999), and to increase superoxide production in endothelial cells (Antoniades et al., 2009; Wilcox, 2012).

The transcription factor NR4A3 belongs to the NR4A subfamily of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily, and is implicated in angiogenesis, induces endothelial cell growth (Hirano et al., 2019; Mohan et al., 2012; Wenzl et al., 2015; Crean and Murphy, 2021; Rius et al., 2004, 2006; Martinez-Gonzalez et al., 2003; Arkenbout et al, 2002, Arkenbout et al, 2003) and is modulated through several pathways, including PI3K/Akt (PKB). Up-regulation by NR4A3 causes endothelial dysfunction by promoting vessel proliferation and migration (Wang et al., 2021), as well as thickened neointima and increasing stenosis after vascular damage (Rodríguez-Calvo et al., 2013).

ITGAV encodes a αVβ3 heterodimer subunit. αVβ3 has been implicated in regulation of endothelial cell adhesion, migration and survival and may play a key role in angiogenesis (Avraamides et al., 2008; Mahabeleshwar et al., 2006; Ruegg and Mariotti, 2003). The αVβ3 heterodimer is highly expressed in proliferative endothelial cells and is up-regulated in tumorigenic blood vessels (Liao et al., 2017; Felding-Habermann and Cheresh, 1993; Plow et al., 2014). Blocking αVβ3 function reduces angiogenesis and capillary network size (Friedlander et al., 1995; Mas-Moruno et al., 2010; Fukushima et al., 2005). VEGF up-regulates the ITGAV/ITGB3 subunit (Witmer et al., 2004). Recently, genes regulating chromatin remodelling have been shown to be associated with moyamoya angiopathy (Pinard et al., 2020). NO seems to play a key role in chromatin folding in human vascular endothelial cells (Illi et al., 2008). This may suggest that several possible pathophysiological mechanisms underlying MMD seem to converge through the pathway of NO dysregulation.

The identified gene variants in our study have not been associated with other neurovascular disorders, however, several have an impact on NO pathways. Thus, NO pathways may well represent a key mechanism in MMD pathology. Our findings are in line with a complex mode of inheritance and underpin previous findings where one distinct predominant susceptibility gene is absent in Northern-European MMD patients.

Our study has several limitations. The main limitation is the small number of patients with different family structures, posing a particular challenge to our study with regards to the choice of analytical approach. Given our small and heterogeneous cohort, our results must be considered hypothesis generating and warranting confirmation from larger studies. It also needs to be considered that the selection of genes associated with angiogenesis in our candidate gene list may bias our results towards a false positive finding in regards to NO regulation pathways involved in MMD pathogenesis. Finally, a restriction of WES is the exclusive identification of variants in the coding regions of the genome. Variations in non-coding regions as well as large structural changes, such as large indels, duplications of genes and CNV remain undetected.

The candidate genes identified in this study add to the growing list of candidate genes in MMD. Moreover, the recent finding of biallelic NOS3 variants in familial moyamoya angiopathy (Guey et al., 2023) underlines the importance of the NO pathways and warrants future functional exploration of the consequences of the variants identified. In addition to the genes identified in the current report, other genes associated with NO pathways and vascular regulation in MMD would also be valuable candidates for future functional studies. For instance, homozygous variants in the gene GUCY1A3 increased the risk for MMD in a small sub-set of European patients with achalasia (Wallace et al., 2016). GUCY1A3 encodes a subunit of the soluble guanylyl cyclase (SGC) complex which acts as an important receptor for NO (Kessler et al., 2017). Inactivation of genes encoding subunits of the SGC complex has been shown to reduce angiogenesis in vitro (Saino et al., 2004). Recently, DIAPH1 variants have been shown to be associated with sporadic MMD in Non-East Asian patients in a genetic association study using WES (Kundishora et al., 2021). The results from the latter study suggest DIAPH1 as a novel risk gene for MMD by association with impaired vascular cell actin remodelling in MMD pathogenesis (Kundishora et al., 2021).

5. Conclusion

No shared genetic risk variant or gene was identified in our patients of Northern-European origin, and none had the East-Asian variant in the ring finger protein RNF213. Identification of a de novo variant in the AGXT2 gene supports the hypothesis of NO pathway dysregulation as a key contributor and plausible risk factor in MMD pathophysiology. This is further supported by the identification of five other rare gene variants in NR4A3, ITGAV, GRB7 and NOS3, all involved in NO metabolism. The role of NO metabolism in MMD should be further assessed in functional studies and confirmed in larger patient cohorts.

Compliance with ethical standards

No funding was received for this research.

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the National Hospital, Oslo University Hospital, the Regional Ethics Committee of South Eastern Norway and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Declaration of competing interest

MW: research grants from the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority (grant number 2014060), ownership of stock Biontech/Pfizer, speaker honoraria from the Norwegian Medical Association.

The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Handling Editor: Dr W Peul

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bas.2023.101745.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Adzhubei I., Jordan D.M., Sunyaev S.R. Predicting functional effect of human missense mutations using PolyPhen-2. Curr. Protoc. Hum. Genet. 2013 doi: 10.1002/0471142905.hg0720s76. (Chapter 7): p. Unit7 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso J., et al. The nuclear receptor NOR-1 modulates redox homeostasis in human vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2018;122:23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrew P.J., Mayer B. Enzymatic function of nitric oxide synthases. Cardiovasc. Res. 1999;43(3):521–531. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00115-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniades C., et al. Association of plasma asymmetrical dimethylarginine (ADMA) with elevated vascular superoxide production and endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling: implications for endothelial function in human atherosclerosis. Eur. Heart J. 2009;30(9):1142–1150. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arkenbout E.K., et al. Protective function of transcription factor TR3 orphan receptor in atherogenesis: decreased lesion formation in carotid artery ligation model in TR3 transgenic mice. Circulation. 2002;106(12):1530–1535. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000028811.03056.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arkenbout E.K., et al. TR3 orphan receptor is expressed in vascular endothelial cells and mediates cell cycle arrest. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2003;23(9):1535–1540. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000084639.16462.7A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avraamides C.J., Garmy-Susini B., Varner J.A. Integrins in angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2008;8(8):604–617. doi: 10.1038/nrc2353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkeland P., Lauritsen J. Incidence of moyamoya disease in Denmark: a population-based register study. Acta Neurochir. Suppl. 2018;129:91–93. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-73739-3_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boger R.H., et al. LDL cholesterol upregulates synthesis of asymmetrical dimethylarginine in human endothelial cells: involvement of S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferases. Circ. Res. 2000;87(2):99–105. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boger R.H., et al. Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) as a prospective marker of cardiovascular disease and mortality–an update on patient populations with a wide range of cardiovascular risk. Pharmacol. Res. 2009;60(6):481–487. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecchi A.C., et al. RNF213 rare variants in an ethnically diverse population with Moyamoya disease. Stroke. 2014;45(11):3200–3207. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.006244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y., Chan A.P. PROVEAN web server: a tool to predict the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(16):2745–2747. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun S., Fay J.C. Identification of deleterious mutations within three human genomes. Genome Res. 2009;19(9):1553–1561. doi: 10.1101/gr.092619.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Closs E.I., et al. Interference of L-arginine analogues with L-arginine transport mediated by the y+ carrier hCAT-2B. Nitric Oxide. 1997;1(1):65–73. doi: 10.1006/niox.1996.0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crean D., Murphy E.P. Targeting NR4A nuclear Receptors to control stromal cell inflammation, metabolism, angiogenesis, and tumorigenesis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.589770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davignon J., Ganz P. Role of endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2004;109(23 Suppl. 1) doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000131515.03336.f8. III27-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davydov E.V., et al. Identifying a high fraction of the human genome to be under selective constraint using GERP++ PLoS Comput. Biol. 2010;6(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1001025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraci F.M., Brian J.E., Jr., Heistad D.D. Response of cerebral blood vessels to an endogenous inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;269(5 Pt 2) doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.5.H1522. p. H1522-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felding-Habermann B., Cheresh D.A. Vitronectin and its receptors. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1993;5(5):864–868. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(93)90036-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feliers D., et al. Symmetric dimethylarginine alters endothelial nitric oxide activity in glomerular endothelial cells. Cell. Signal. 2015;27(1):1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedlander M., et al. Definition of two angiogenic pathways by distinct alpha v integrins. Science. 1995;270(5241):1500–1502. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5241.1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima K., et al. Tumor necrosis factor and vascular endothelial growth factor induce endothelial integrin repertories, regulating endovascular differentiation and apoptosis in a human extravillous trophoblast cell line. Biol. Reprod. 2005;73(1):172–179. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.039479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grangeon L., et al. Clinical and molecular features of 5 European multigenerational families with moyamoya angiopathy. Stroke. 2019;50(4):789–796. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.023972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guey S., et al. Moyamoya disease and syndromes: from genetics to clinical management. Appl. Clin. Genet. 2015;8:49–68. doi: 10.2147/TACG.S42772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guey S., et al. Rare RNF213 variants in the C-terminal region encompassing the RING-finger domain are associated with moyamoya angiopathy in Caucasians. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2017;25(8):995–1003. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2017.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guey S., et al. Rare RNF213 variants in the C-terminal region encompassing the RING-finger domain are associated with moyamoya angiopathy in Caucasians. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2017;25(8):995–1003. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2017.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guey S., et al. Biallelic variants in NOS3 and GUCY1A3, the two major genes of the nitric oxide pathway, cause moyamoya cerebral angiopathy. Hum. Genom. 2023;17(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s40246-023-00471-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of moyamoya disease (spontaneous occlusion of the circle of Willis) Neurol. Med.-Chir. 2012;52(5):245–266. doi: 10.2176/nmc.52.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herve D., et al. Loss of alpha1beta1 soluble guanylate cyclase, the major nitric oxide receptor, leads to moyamoya and achalasia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2014;94(3):385–394. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hever P., Alamri A., Tolias C. Moyamoya angiopathy - is there a Western phenotype? Br. J. Neurosurg. 2015;29(6):765–771. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2015.1096902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano T., et al. Forced expression of NR4A3 induced the differentiation of human neuroblastoma-derived NB1 cells. Med. Oncol. 2019;36(8):66. doi: 10.1007/s12032-019-1289-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illi B., et al. Nitric oxide modulates chromatin folding in human endothelial cells via protein phosphatase 2A activation and class II histone deacetylases nuclear shuttling. Circ. Res. 2008;102(1):51–58. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.157305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamada F., et al. A genome-wide association study identifies RNF213 as the first Moyamoya disease gene. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;56(1):34–40. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2010.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler T., et al. Functional characterization of the GUCY1A3 coronary artery disease risk locus. Circulation. 2017;136(5):476–489. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircher M., et al. A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat. Genet. 2014;46(3):310–315. doi: 10.1038/ng.2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinloog R., et al. Regional differences in incidence and patient characteristics of moyamoya disease: a systematic review. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2012;83(5):531–536. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2011-301387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi H., et al. RNF213 rare Variants in Slovakian and Czech moyamoya disease patients. PLoS One. 2016;11(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer M., et al. Inheritance of moyamoya disease in a Caucasian family. Eur. J. Neurol. 2012;19(3):438–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P., Henikoff S., Ng P.C. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat. Protoc. 2009;4(7):1073–1081. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundishora A.J., et al. DIAPH1 Variants in Non-East Asian patients with sporadic moyamoya disease. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(8):993–1003. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Durbin R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(5):589–595. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Z., Kasirer-Friede A., Shattil S.J. Optogenetic interrogation of integrin alphaVbeta3 function in endothelial cells. J. Cell Sci. 2017;130(20):3532–3541. doi: 10.1242/jcs.205203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., et al. A rare Asian founder polymorphism of Raptor may explain the high prevalence of Moyamoya disease among East Asians and its low prevalence among Caucasians. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2010;15(2):94–104. doi: 10.1007/s12199-009-0116-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., et al. Identification of RNF213 as a susceptibility gene for moyamoya disease and its possible role in vascular development. PLoS One. 2011;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., et al. Genomewide association study identifies no major founder variant in Caucasian moyamoya disease. J. Genet. 2013;92(3):605–609. doi: 10.1007/s12041-013-0304-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., et al. Genomewide association study identifies no major founder variant in Caucasian moyamoya disease. J. Genet. 2013;92(3):605–609. doi: 10.1007/s12041-013-0304-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J., et al. RNF213 polymorphism and Moyamoya disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol. India. 2013;61(1):35–39. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.107927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacAllister R.J., et al. Concentration of dimethyl-L-arginine in the plasma of patients with end-stage renal failure. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 1996;11(12):2449–2452. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.ndt.a027213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahabeleshwar G.H., et al. Integrin signaling is critical for pathological angiogenesis. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203(11):2495–2507. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Gonzalez J., et al. Neuron-derived orphan receptor-1 (NOR-1) modulates vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Circ. Res. 2003;92(1):96–103. doi: 10.1161/01.es.0000050921.53008.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mas-Moruno C., Rechenmacher F., Kessler H. Cilengitide: the first anti-angiogenic small molecule drug candidate design, synthesis and clinical evaluation. Anti Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2010;10(10):753–768. doi: 10.2174/187152010794728639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda H., et al. Accelerated intimal hyperplasia and increased endogenous inhibitors for NO synthesis in rabbits with alloxan-induced hyperglycaemia. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;126(1):211–218. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna A., et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20(9):1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mineharu Y., et al. Inheritance pattern of familial moyamoya disease: autosomal dominant mode and genomic imprinting. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2006;77(9):1025–1029. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.096040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan H.M., et al. Molecular pathways: the role of NR4A orphan nuclear receptors in cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012;18(12):3223–3228. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda A., et al. Elevation of nitric oxide metabolites in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with moyamoya disease. Acta Neurochir. 2000;142(11):1275–1279. doi: 10.1007/s007010070025. discussion 1279-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northcott J.M., Czubryt M.P., Wigle J.T. Vascular senescence and ageing: a role for the MEOX proteins in promoting endothelial dysfunction. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2017;95(10):1067–1077. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2017-0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinard A., et al. The pleiotropy associated with de novo variants in CHD4, CNOT3, and SETD5 extends to moyamoya angiopathy. Genet. Med. 2020;22(2):427–431. doi: 10.1038/s41436-019-0639-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plow E.F., Meller J., Byzova T.V. Integrin function in vascular biology: a view from 2013. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2014;21(3):241–247. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0000000000000042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees D.D., et al. Characterization of three inhibitors of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in vitro and in vivo. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1990;101(3):746–752. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb14151.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rentzsch P., et al. CADD: predicting the deleteriousness of variants throughout the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D886–D894. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reva B., Antipin Y., Sander C. Predicting the functional impact of protein mutations: application to cancer genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(17):e118. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rius J., et al. Involvement of neuron-derived orphan receptor-1 (NOR-1) in LDL-induced mitogenic stimulus in vascular smooth muscle cells: role of CREB. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004;24(4):697–702. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000121570.00515.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rius J., et al. NOR-1 is involved in VEGF-induced endothelial cell growth. Atherosclerosis. 2006;184(2):276–282. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochette L., et al. Nitric oxide synthase inhibition and oxidative stress in cardiovascular diseases: possible therapeutic targets? Pharmacol. Ther. 2013;140(3):239–257. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Calvo R., et al. Over-expression of neuron-derived orphan receptor-1 (NOR-1) exacerbates neointimal hyperplasia after vascular injury. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013;22(10):1949–1959. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers M.F., et al. FATHMM-XF: accurate prediction of pathogenic point mutations via extended features. Bioinformatics. 2018;34(3):511–513. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruegg C., Mariotti A. Vascular integrins: pleiotropic adhesion and signaling molecules in vascular homeostasis and angiogenesis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2003;60(6):1135–1157. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-2297-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahlberg K.K., et al. The HER2 amplicon includes several genes required for the growth and survival of HER2 positive breast cancer cells. Mol. Oncol. 2013;7(3):392–401. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saino M., et al. Inhibition of angiogenesis in human glioma cell lines by antisense RNA from the soluble guanylate cyclase genes, GUCY1A3 and GUCY1B3. Oncol. Rep. 2004;12(1):47–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz J.M., et al. MutationTaster evaluates disease-causing potential of sequence alterations. Nat. Methods. 2010;7(8):575–576. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0810-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seppala I., et al. Associations of functional alanine-glyoxylate aminotransferase 2 gene variants with atrial fibrillation and ischemic stroke. Sci. Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep23207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitia S., et al. From endothelial dysfunction to atherosclerosis. Autoimmun. Rev. 2010;9(12):830–834. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki J., Takaku A. Cerebrovascular "moyamoya" disease. Disease showing abnormal net-like vessels in base of brain. Arch. Neurol. 1969;20(3):288–299. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1969.00480090076012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tain Y.L., et al. Melatonin prevents hypertension and increased asymmetric dimethylarginine in young spontaneous hypertensive rats. J. Pineal Res. 2010;49(4):390–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2010.00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Technologies A. 2017. SureSelectXT Target Enrichment System for Illumina Paired-End Multiplexed Sequencing Library Protocol. [Online]. [Google Scholar]

- Uchino K., et al. Moyamoya disease in Washington state and California. Neurology. 2005;65(6):956–958. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000176066.33797.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallance P., et al. Accumulation of an endogenous inhibitor of nitric oxide synthesis in chronic renal failure. Lancet. 1992;339(8793):572–575. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90865-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Auwera G.A., et al. From FastQ data to high confidence variant calls: the Genome Analysis Toolkit best practices pipeline. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics. 2013;43(1110) doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1110s43. 11.10.1-11.10.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigeland M.D., Gjøtterud K.S., Selmer K.K. FILTUS: a desktop GUI for fast and efficient detection of disease-causing variants, including a novel autozygosity detector. Bioinformatics. 2016;32(10):1592–1594. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace S., et al. Disrupted nitric oxide signaling due to GUCY1A3 mutations increases risk for moyamoya disease, achalasia and hypertension. Clin. Genet. 2016;90(4):351–360. doi: 10.1111/cge.12739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K., Li M., Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(16):e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., et al. Impacts and interactions of PDGFRB, MMP-3, TIMP-2, and RNF213 polymorphisms on the risk of Moyamoya disease in Han Chinese human subjects. Gene. 2013;526(2):437–442. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.05.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., et al. Association of genetic variants with moyamoya disease in 13 000 individuals: a meta-analysis. Stroke. 2020;51(6):1647–1655. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.029527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., et al. NR4A3 induces endothelial dysfunction through up-regulation of endothelial 1 expression in adipose tissue-derived stromal cells. Life Sci. 2021;264 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzl K., et al. The nuclear orphan receptor NR4A1 and NR4A3 as tumor suppressors in hematologic neoplasms. Curr. Drug Targets. 2015;16(1):38–46. doi: 10.2174/1389450115666141120112818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox C.S. Asymmetric dimethylarginine and reactive oxygen species: unwelcome twin visitors to the cardiovascular and kidney disease tables. Hypertension. 2012;59(2):375–381. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.187310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witmer A.N., et al. In vivo angiogenic phenotype of endothelial cells and pericytes induced by vascular endothelial growth factor-A. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2004;52(1):39–52. doi: 10.1177/002215540405200105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshino Y., et al. Missense variants of the alanine:glyoxylate aminotransferase 2 gene are not associated with Japanese schizophrenia patients. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2014;53:137–141. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanoni P., et al. The genetic landscape and clinical implication of pediatric Moyamoya angiopathy in an international cohort. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2023 doi: 10.1038/s41431-023-01320-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.