Abstract

Introduction

Complex ankle fractures frequently involve the posterior malleolus. Many classifications describing posterior malleolar fractures (PMF) exist. The aim of this study was to provide a systematic literature review to outline existing PMF classifications and estimate their accuracy.

Methods

The databases PubMed and Scopus were searched without time limits. Only specific PMF classifications were included; general ankle and/or pilon fracture classifications were excluded. Selection and data extraction was performed by three independent observers. The systematic literature search was performed according to the current criteria of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). The methodological quality of the included studies was quantified using the modified Coleman score.

Results

A total of 110 studies with a total of 12.614 patients were included. Four main classifications were identified: Those describing the size of the posterior malleolar fracture (n = 66), Haraguchi (n = 44), Bartoníček/Rammelt (n = 21) and Mason (n = 12). The quality of the studies was moderate to good with a median Coleman-score of 43.5 (14–79) and a weighted median Coleman-score of 42.5 points. All classifications achieved a substantial to perfect score regarding the inter- and intraobserver reliability, with Mason scoring the lowest in comparison.

Conclusions

None of the reviewed PMF classifications has been able to establish itself decisively in the literature. Most of the classifications are insufficient in terms of a derivable treatment algorithm or a prognosis with regard to outcome. However, as the Bartoníček/Rammelt classification has the greatest potential due to its treatment algorithm, its reliability in combination with consistent predictive values, its usage in clinical practice and research appears advisable.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00402-022-04643-7.

Keywords: Ankle fracture, Posterior malleolus, Systematic literature review, Fracture classification

Introduction

Ankle fractures present as one of the most common fractures with a prevalence of 4–9% [1, 2]. Posterior malleolar fracture (PMF), also known as malleolus tertius, posterior tibial fracture, or Volkmann-fragment appears in up to 44% of ankle fractures [3–5]. If the posterior malleolus is affected, therapy results may be worse and its presence in ankle fractures is known to be of negative prognostic value [1, 4, 6–10].

Decision-making to fixate PMF is still highly debatable and traditionally often based on fracture size measurement on radiographs, with lack of accuracy and poor reliability [11–18]. Nowadays, it is generally believed that the morphology of the fragment is more closely related to the fracture pattern and is, therefore, more important in classifying the fracture [14, 19–21]. Consequently, with regard to the proportion of the affected joint surface and recommendation for surgical fixation of PMF, there is a shift away from the 1/3 dogma [7, 17, 22–28]. With increasing understanding of fracture morphology and the routine use of computed tomography (CT), efforts have been made in recent years to establish new classification systems based on CT imaging [14, 29, 30]. Until now, there is no international consensus regarding classification and treatment of PMF [24, 31, 32].

A good classification system helps the orthopedic surgeon to identify and characterize a problem, suggest a potential prognosis, and offer guidance in determining the appropriate treatment method for a particular condition. To achieve optimal therapeutic results, a complete understanding of the morphology is indispensable.

Therefore, the aims of this systematic review were first, to determine how many studies use a classification of the PMF; second, to identify and to describe which classifications of PMF exist; third to examine which classification system does have the most reliable (inter- and intra- observer) scores; and fourth, to evaluate the predictive value of the classifications in terms of postoperative outcomes.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

The study protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD42021264268). The review was performed and reported according to the PRISMA 2020 checklist [33].

The electronic databases of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE via PubMed and Scopus were searched systematically. The search was performed on the 20th of March 2021. The following search algorithm was used: (posterior AND ankle AND fracture) OR (posterior AND (malleolus OR malleolar) AND fracture) OR (ankle AND volkmann) OR (trimalleolar AND fracture) OR (posterior AND pilon AND fracture). A final update of the search was conducted 12th of May 2022 using the same search string. Furthermore, reference lists of relevant reviews and included articles were screened for additional articles. Bidirectional citation search was used including backward and forward citation search methods [34]. There were no limitations on journal or publication date of the article.

Study selection

Studies reporting data on classification systems of trimalleolar ankle fractures were screened for using a PMF classification. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were cross checked by three reviewers (HW, JT, EM), first by screening the title and abstract, second by reading the full text. Clinical studies were included for data extraction. Cadaveric studies, review articles, case reports with fewer than 10 cases, studies that did not include a posterior malleolus specific classification, and studies not written in English, were excluded.

Data extraction

The study selection and data extraction were independently performed by two review authors (JT, EM). Disagreements were discussed in a consensus meeting and if a disagreement persisted, a third reviewer (HW) made the final decision. Data were extracted from the included studies using a Microsoft Office® Excel spreadsheet. This included the following data: study design, sample size and source, fragment characteristics (e.g., classification, displacement, treatment), reliability- and validity scores and additional data the classification addressed, like treatment allocation and prognostic value of it, were collected. Names of used classification system were listed and their frequency in use was counted.

Study quality assessment

The methodological quality of the included studies was quantified using a modified Coleman score [35]. The modified Coleman score was applied by two independent reviewers (HW, JT) (Online Resource 1). The score is composed of two parts. Part A assesses study size, average follow-up time, percentage of patients with follow-up, number of interventions, study type, diagnostic certainty, description of surgical method, and postoperative rehabilitation. Part B is comprised of outcome criteria, procedure for assessing outcomes, and description of the subject selection process. The maximum score to be achieved is 100 points.

Statistical analysis

The data were processed descriptively, therefore, no meta-analysis was performed. Patient demographic characteristics (number of patients/feet, patient age and sex) were summarized. Weighted median scores were calculated for the modified Coleman score and for the age of the evaluated patient cohort. Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The kappa values of inter- and intraobserver reliability were interpreted as defined by Landis and Koch (< 0.20: slight, 0.21–0.40: fair, 0.41–0.60: moderate, 0.61–0.80: substantial, 0.81–1.00: almost perfect) [36].

Results

Included studies

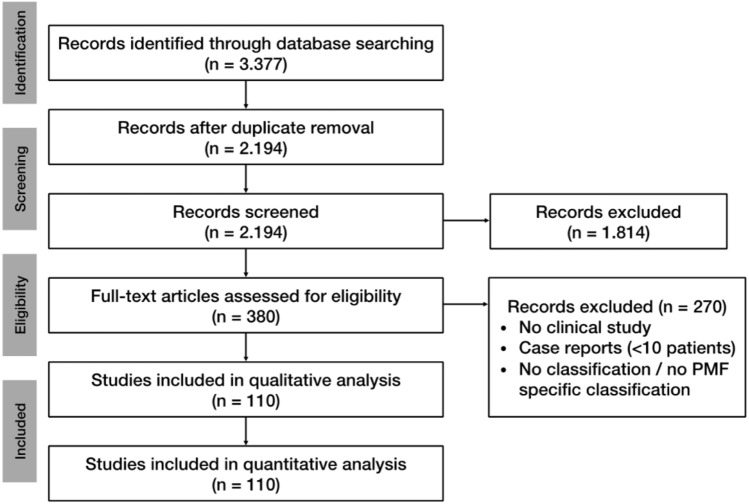

Evaluation of the databases revealed 3.377 studies potentially relevant for inclusion. After excluding duplicates, title and abstract of the remaining studies were assessed. 380 studies were eligible for full-text analysis, after applying the exclusion criteria (no clinical study, case reports < 10 patients, no classification/no PMF-specific classification), 110 remaining relevant studies were included in this review. The selection process was performed according to “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses” (PRISMA) and is shown in Fig. 1 [33].

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart

Study characteristics

A total of 110 studies, published between 1965 and 2022, using 143 classification systems, were included. The studies include a number of 12.614 patients with 12.633 ankle fractures and a weighted median age of 44.55 years (13–100). 5.963 patients were female and 5.231 male, 11 studies did not report gender distribution [6, 20, 24, 37–44]. There were 22 prospective studies, 88 retrospective studies; 11 studies were multicenter, and 99 single center studies (Table 1). Detailed information about patient demographics is demonstrated in Table 2. Four specific classifications for the PMF were found: a classification based on the relation of the fragment size compared to the size of the tibial joint surface [45] (referred to as PMF Classification according to fracture size) and 3 CT-based classifications according to Haraguchi, Bartoníček/Rammelt, and Mason [14, 29, 30].

Table 1.

Overview of the included studies

| Study | Study type | Single center vs. multicenter | Modified Coleman methodology score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective vs. retrospective | LoE | Part A | Part B | Total | ||

| Warner (1965) [37] | RS | SC | IV | 17 | 0 | 17 |

| McDaniel (1977) [58] | RS | SC | IV | 35 | 7 | 42 |

| Yde (1980) [99] | RS | SC | IV | 15 | 10 | 25 |

| Olerud (1986) [38] | RS | SC | IV | 38 | 14 | 52 |

| Jaskulka (1989) [4] | RS | SC | III | 33 | 15 | 48 |

| Broos (1991) [8] | PS | MC | IV | 23 | 10 | 33 |

| Broos (1992) [100] | RS | MC | IV | 18 | 12 | 30 |

| Heim (2002) [39] | PS | SC | II | 22 | 12 | 34 |

| Langenhuijsen (2002) [7] | RS | SC | IV | 32 | 21 | 53 |

| Papachristou (2003) [101] | PS | SC | II | 38 | 17 | 55 |

| De Vries (2005) [52] | RS | SC | IV | 14 | 21 | 35 |

| Haraguchi (2006) [14] | PS | SC | IV | 12 | 12 | 24 |

| Farsetti (2009) [102] | RS | SC | III | 34 | 18 | 52 |

| Büchler (2009) [13] | RS | SC | IV | 5 | 14 | 19 |

| Forberger (2009) [103] | RS | SC | IV | 34 | 23 | 57 |

| Tejwani (2010) [6] | PS | SC | IV | 38 | 23 | 61 |

| Hong-Chuan (2010) [104] | RS | SC | IV | 37 | 18 | 55 |

| Heim (2010) [77] | RS | SC | IV | 27 | 21 | 48 |

| Mingo-Robinet (2011) [46] | RS | SC | II | 34 | 18 | 52 |

| Purnell (2011) [105] | RS | SC | IV | 14 | 14 | 28 |

| Abdelgawad (2011) [70] | RS | SC | IV | 28 | 10 | 38 |

| Xu (2012) [53] | RS | MC | III | 20 | 21 | 41 |

| Di Giorgio (2013) [106] | RS | SC | IV | 30 | 21 | 51 |

| Hoelsbrekken (2013) [107] | PS | SC | III | 53 | 26 | 79 |

| Erdem (2014) [108] | PS | SC | II | 47 | 23 | 70 |

| Hong (2014) [109] | RS | SC | IV | 15 | 21 | 36 |

| Bartonicek (2015) [29] | RS | MC | IV | 15 | 19 | 34 |

| Evers (2015) [47] | RS | SC | III | 14 | 20 | 34 |

| Drijfhout van Hooff (2015) [71] | RS | SC | IV | 23 | 21 | 44 |

| Kim (2015) [110] | PS | SC | IV | 40 | 26 | 66 |

| Verhage (2015) [111] | RS | SC | III | 20 | 23 | 43 |

| Mangnus (2015) [20] | RS | SC | IV | 9 | 11 | 20 |

| Choi (2015) [112] | RS | SC | IV | 34 | 16 | 50 |

| de Muinck Keizer (2016) [40] | RS | SC | IV | 8 | 6 | 14 |

| Endo (2016) [113] | PS | SC | II | 40 | 20 | 60 |

| Chan (2016) [114] | RS | SC | IV | 25 | 12 | 37 |

| Guo (2017) [54] | RS | SC | III | 40 | 19 | 59 |

| Naumann (2017) [115] | RS | MC | IV | 21 | 21 | 42 |

| Vidovic (2017) [116] | PS | SC | II | 49 | 23 | 72 |

| Bali (2017) [64] | PS | MC | IV | 35 | 31 | 66 |

| Shi (2017) [117] | PS | SC | II | 47 | 28 | 75 |

| Zhong (2017) [118] | RS | SC | III | 34 | 21 | 55 |

| Mason (2017) [30] | RS | SC | III | 25 | 24 | 49 |

| Saygili (2017) [55] | RS | SC | III | 32 | 18 | 50 |

| Zhou (2017) [119] | RS | SC | IV | 30 | 15 | 45 |

| Wang (2017) [120] | RS | SC | IV | 37 | 21 | 58 |

| Xing (2018) [121] | RS | SC | IV | 30 | 12 | 42 |

| Baek (2018) [122] | PS | SC | II | 40 | 19 | 59 |

| Levack (2018) [123] | RS | SC | III | 40 | 21 | 61 |

| Kumar (2018) [80] | PS | SC | IV | 19 | 19 | 38 |

| Kim (2018) [124] | RS | SC | IV | 30 | 20 | 50 |

| Yi (2018) [95] | RS | SC | IV | 12 | 14 | 26 |

| Tosun (2018) [51] | RS | SC | III | 27 | 18 | 45 |

| Miller (2018) [125] | RS | SC | III | 28 | 12 | 40 |

| Huang (2018) [126] | RS | SC | III | 15 | 14 | 29 |

| Zhang (2018) [82] | RS | SC | III | 9 | 14 | 23 |

| Xing (2018) [127] | RS | SC | III | 34 | 15 | 49 |

| Sobol (2018) [41] | RS | SC | III | 18 | 12 | 30 |

| Baumbach (2019) [48] | RS | SC | III | 30 | 14 | 44 |

| Bartonicek (2019) [128] | RS | MC | IV | 9 | 14 | 23 |

| Jayatilaka (2019) [43] | PS | MC | IV | 19 | 5 | 24 |

| Blom (2019) [19] | RS | SC | III | 22 | 21 | 43 |

| Vosoughi (2019) [67] | RS | SC | III | 9 | 12 | 21 |

| Hendrickx (2019) [129] | RS | SC | IV | 15 | 14 | 29 |

| Mason (2019) [68] | RS | SC | IV | 32 | 21 | 53 |

| Kang (2019) [49] | PS | SC | II | 47 | 26 | 73 |

| Kellam (2019) [130] | RS | SC | III | 12 | 14 | 26 |

| Meijer (2019) [131] | PS | SC | II | 23 | 28 | 51 |

| Sheikh (2019) [60] | RS | SC | IV | 5 | 14 | 19 |

| Meijer (2019) [132] | RS | SC | III | 23 | 23 | 46 |

| Testa (2019) [133] | RS | SC | iV | 34 | 21 | 55 |

| Mitchell (2019) [42] | RS | SC | IV | 18 | 9 | 27 |

| Verhage (2019) [72] | RS | SC | IIB | 28 | 23 | 51 |

| Philpott (2020) [44] | RS | SC | IV | 30 | 14 | 44 |

| Lee (2020) [134] | RS | SC | III | 33 | 21 | 54 |

| Wang (2020) [61] | RS | SC | III | 15 | 14 | 29 |

| Pilskog (2020) [56] | RS | SC | III | 37 | 21 | 58 |

| Zhang (2020) [135] | RS | SC | IV | 12 | 14 | 26 |

| Blom (2020) [63] | RS | SC | IV | 17 | 23 | 40 |

| Yang (2020) [136] | PS | SC | IV | 28 | 18 | 46 |

| Wang (2020) [137] | RS | SC | III | 9 | 12 | 21 |

| Wang (2020) [138] | RS | SC | III | 40 | 21 | 61 |

| Sultan (2020) [75] | RS | SC | IV | 18 | 14 | 32 |

| Lee (2020) [139] | RS | SC | III | 12 | 14 | 26 |

| Mertens (2020) [65] | PS | SC | IV | 48 | 26 | 74 |

| Gandham (2020) [83] | RS | SC | IV | 15 | 9 | 24 |

| McHale (2020) [50] | RS | SC | III | 17 | 23 | 40 |

| He (2020) [140] | RS | SC | IV | 9 | 14 | 23 |

| Liu (2020) [141] | PS | SC | II | 47 | 23 | 70 |

| Palmanovich (2020) [62] | RS | SC | III | 17 | 12 | 29 |

| Martin (2021) [142] | PS | SC | IV | 40 | 28 | 68 |

| Yu (2021) [143] | PS | SC | III | 44 | 33 | 77 |

| Tucek (2021) [66] | RS | SC | IV | 30 | 18 | 48 |

| Maluta (2021) [1] | RS | SC | IV | 30 | 21 | 51 |

| Ceccarini (2021) [144] | RS | SC | III | 38 | 21 | 59 |

| Neumann (2021) [21] | RS | SC | III | 35 | 21 | 56 |

| Quan (2021) [79] | RS | SC | III | 12 | 12 | 24 |

| Black (2021) [145] | RS | MC | IV | 15 | 12 | 27 |

| Fidan (2021) [146] | RS | SC | IV | 29 | 16 | 45 |

| Erinç (2021) [147] | RS | SC | III | 40 | 19 | 59 |

| Sun (2021) [98] | RS | SC | IV | 26 | 29 | 55 |

| Ræder (2021) [59] | RS | MC | III | 21 | 20 | 41 |

| Xie (2021) [28] | RS | SC | III | 25 | 10 | 35 |

| Schoenmakers (2021) [78] | RS | SC | III | 15 | 23 | 38 |

| Seo (2022) [148] | RS | SC | III | 15 | 12 | 27 |

| Kleinertz (2022) [32] | RS | SC | IV | 26 | 12 | 14 |

| Yamamoto (2022) [57] | RS | MC | III | 30 | 20 | 50 |

| Patton (2022) [149] | RS | SC | IV | 20 | 12 | 32 |

| Pflüger (2022) [24] | RS | SC | IV | 18 | 11 | 29 |

| Sun (2022) [150] | RS | SC | IV | 30 | 21 | 51 |

Table 2.

Patient demographics

| Number of patients | 12.614 |

| Median age in years, (range) | 44.55 (13–100) |

| Female, n (%) | 5.963 (53.2) |

| Male, n (%) | 5.231 (46.7) |

| PMF classification according to fracture size | |

| Number of patients | 8.506 |

| Median age in years, (range) | 46.67 (13–100) |

| Female, n (%) | 4.035 (52.6) |

| Male, n (%) | 3.624 (47.3) |

| Fracture ≥ 25% of joint surface | 1.095 |

| Fractrure < 25% of joint surface | 1.579 |

| Other cut-off value used for fracture | 1.117 |

| Fracture cut-off value not stated | 2.199 |

| Haraguchi classification | |

| Number of patients | 3.790 |

| Median age in years (range) | 46.8 (13–100) |

| Female, n (%) | 1.699 (52.9) |

| Male, n (%) | 1.508 (47.0) |

| HC Type I | 1.525 |

| HC Type II | 910 |

| HC Type III | 318 |

| Bartonicek/Rammelt classification | |

| Number of patients | 2.497 |

| Median age in years (range) | 47.0 (14–90) |

| Female, n (%) | 1.282 (55.6) |

| Male, n (%) | 1.022 (44.3) |

| BRC type 1 | 145 |

| BRC type 2 | 917 |

| BRC type 3 | 458 |

| BRC type 4 | 348 |

| BRC type 5 | 7 |

| Mason classification | |

| Number of patients | 1.164 |

| Median age in years (range) | 48.55 (17–90) |

| Female, n (%) | 479 (59.5) |

| Male, n (%) | 326 (40.4) |

| MC type 1 | 149 |

| MC type 2A | 248 |

| MC type 2B | 263 |

| MC type 3 | 124 |

HC Haraguchi classification, BRC Bartonicek/Rammelt classification, MC Mason classification

PMF classification according to fracture size

Sixty-six studies that used the size of the PMF in relation to the joint surface as a classification could be included. Of these, 35 studies used radiographs and 30 studies used CT to estimate size, one study did not provide a clear statement in this regard. Only one studied inter- and intraobserver reliability, measuring a substantial Kappa of 0.64 and 0.63 respectively [13]. The majority of these studies used either a cut-off value of 25% for fixation of the PMF (26 studies) or fixed the posterior malleolus regardless of size (28 studies). The remaining studies used either 20% (4 studies), 30% (2 studies), or > 1/3 of the joint area (5 studies) as the cut-off value, 1 study fixed the PMF in young patients or in the presence of subluxation from 10%, and 3 studies did not provide any information (Table 3). Nine studies reported a better outcome with reduction of smaller posterior malleolus fragments [4, 6, 7, 46–51], whereas seven studies reported no difference between fixation and no fixation of smaller posterior malleolus fragments [52–58].

Table 3.

Studies reporting on the “Size Classification”

| Study | Patients/ ankles |

Sex/ age |

Imaging | Description | PMF type distribution | Treatment allocation | Cut-off | Assesing Classification |

Reliability | Predictive outcome values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inter OR |

Intra OR |

||||||||||

| Warner (1965) [37] | n.r./100 | n.r | x-ray | Percentage of tibial articular surface | Unclear | 0–20%: closed reduction, 20–30% only fix MM/LM, 30–60%: ORIF; via transfibular approach | ≥ 20% | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| McDaniel (1977) [58] | 50/51 | 13m, 37f, 41 (20–68) yo | x-ray | Percentage of tibial articular surface | < 10% (9), 10–25% (27), ≥ 25% (15) | Closed methods (28), treated operatively (23; 7 screw fixation PMF ≥ 25%) | ≥ 25% | Yes | n.r | n.r | In PMF ≥ 25% ORIF associated with better outcome than closed treatment |

| Yde (1980) [99] | 487/488 | 263m, 224f, 44 yo | x-ray | Percentage of joint surface | SER3: Only 14% of cases PMF ≥ 25%; PER4: In 73% of cases PMF ≥ 25% | n.r | ≥ 25% | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Olerud (1986) [38] | 134/134 | Not clear/48 (15–86) yo | x-ray | Percentage of joint surface | 86 of 134 with PMF, < 1⁄6 of surface (49), 1⁄6 -1/3(32), ≥ 1/3(5) | Posterior fragments either left alone or fixed with screw | No cut- off | No | n.r | n.r | PMF without displacements best |

| Jaskulka (1989) [4] | 142/142 | 47m, 95f, 46.7 yo | x-ray | Percentage of articular surface | 62 of 142 with PMF: avulsion of posterior Lip (32), PMF 5–20% (15), PMF ≥ 20% (15) | 14 ORIF with screws (none of the posterior lip); if < 20% generally no osteosynthesis | No cut- off | Yes | n.r | n.r | Longterm outcome poorer if fracture of posterior margin present (even small fragments); poorest results: conservativly treated PMF |

| Broos (1991) [8] | 604/612 | 320m, 284f, 41 yo | x-ray | One-third of the joint surface | 178 of 612 fractures with PMF | 100 of 178 patients with PMF fixed with screws; PMF < 1/3 left untouched | ≥ 1/3 | Yes | n.r | n.r | If PMF present only 66% excellent or good result compared with 81% without PMF; ankle fx with PMF > 1/3 with perfect anatomic fixation, give worse results than ankle fractures with small unfixed PMF |

| Broos (1992) [100] | 604/612 | 320m, 284f, 41 yo | x-ray | One-third of the joint surface | 178 of 612 fractures with PMF | 100 of 178 with PMF fixed with screws; PMF < 1/3 left untouched | ≥ 1/3 | Yes | n.r | n.r | In spite of perfect anatomic internal fixation of fragments > 1/3, the results remained worse than with small non fixed posterior fragments |

| Heim (2002) [39] | n.r./111 | n.r | x-ray | One-third of the articular surface | n.r | Surgically fixed if PMF ≥ 1/3 size | ≥ 1/3 | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Langenhuijsen (2002) [7] | 57/57 | 21m, 36f, 49.6 (18–89) yo | x-ray | Percentage of articular surface | PMF < 10% (24); 10–25% (19), > 25% (14) | 53 of 57 treated operatively, 4 conservatively; ORIF (14) (1x < 10%, 3 × 10–25%, 10x ≥ 25%) | No cut- off | Yes | n.r | n.r | Size or fixation of fragment did not influence prognosis; joint congruity was significant factor for prognosis, congruity should be achieved for fragments > 10% of the tibial articular surface |

| Papachristou (2003) [101] | 15/15 | 4m, 11f, 48.8 (14–73) yo | x-ray | Perecntage of articular surface | All between 1/4—1/3 of articular surface | All ORIF PL or PM approach | ≥ 25% | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| De Vries (2005) [52] | 45/45 | 10m, 35f, 61 (37–81) yo | x-ray | Percentage of articular surface | PMF < 25% (32), PMF > 25% (13) | 11 of 45 patients with PMF fixation: PMF ≥ 25% (8), PMF < 25% (3) | ≥ 25% | Yes | n.r | n.r | PMF fixation did not have better outcome than not fixated (AFSS); no evidence for the need for fixation of fragments smaller than 25% |

| Haraguchi (2006) [14] | 57/57 | 41m, 16f, 43 (13–80) yo | CT | Percentage of tibial plafond | 9 of 57 Fx ≥ 25% (7 of 9 extended to medial malleolus) | All fractures treated with ORIF, best approached medially because of medial extension | ≥ 25% | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Farsetti (2009) [102] | 44/44 | 19m, 25f, 43 (18–69) yo | x-ray | Percentage of joint surface length | 26 trimalleolar fractures | ORIF if PMF > 25% (10) | ≥ 25% | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Büchler (2009) [13] | 22/22 | 7m, 15f, 50 (21.9–72.2) yo | x-ray + CT | Percentage of articular surface | All trimalleolar fractures, 19 ankles (86%) with a PM lesion of tibial plafond | n.r | No cut- off | Yes | Kap-pa 0.64 | Kappa 0.63 | n.r |

| Forberger (2009) [103] | 45/45 | 12m, 33f, 54 (18–83) yo | x-ray | Percentage of articular surface |

PMF ≥ 25% (19); PMF ≥ 10% surgically treated if younger (under 50yo) or with subluxation (n = 26) |

PL approach used for osteosynthesis in 45 patients |

≥ 25% ≥ 10% if sub-luxation or < 50 yo |

No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Tejwani (2010) [6] | 309/n.r | n.r./43.3 yo | x-ray | Percentage of fragment size | 54 of with PMF | Fixation decision by surgeon based on size and tibio-talar stability: fixation (20) average size 25.2%; not fixed (34) average size 16.1% | No cut- off | No | n.r | n.r | Trend for better outcome scores for patients who had fixation (numbers too small to meaningfully compare fixation versus no fixation groups) |

| Hong-Chuan (2010) [104] | 96/96 | 75m, 21f, 38 (17–79) yo | x-ray | Percentage of articular surface | PMF < 25% (10); PMF ≥ 25% (26) | PMF ≥ 25 fixed (4 × PM approach, 3 × PL approach, 19 × medial approach; PMF < 25% reduced spontane. after reduction of LM | ≥ 25% | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Heim (2010) [77] | 43/43 | 15m, 28f, 58.8 yo | x-ray | Percentage of articular surface | No PMF (7), small shelllike (10), PMF < 25% (18), PMF ≥ 25% (8) | 8 PMF ≥ 25% fixed: AP screw (4), PA screw (1), plate (3) | No cut- off | Yes | n.r | n.r | Volkmann fx worse prognosis; fixation with anatomic results does not return score to norm (OMAS), instability as indicator for PMF fixation |

| Mingo-Robinet (2011) [46] | 45/45 | 10m, 35f, 50.69 ± 17.32 (20–80) yo | x-ray | Percentage of articular surface | PMF < 25% (20), PMF ≥ 25% (25) | Ligamentotaxis (27), AP fixation (15), PL fixation (3) | No cut- off | Yes | n.r | n.r | Tendency toward worse result when PMF ≥ 25%; better radiological results when small PMF reduced; results encourage to fix all PMF ≥ 25% and fix most of smaller PMF not satisfactorily reduced by ligamentotaxis |

| Purnell (2011) [105] | 66/67 | 45m, 21f, 44 (18–69) yo | CT | Percentage of articular surface | 23 of 67 with PMF | PMF fixed if ≥ 25% (AP screws after closed reduction) | ≥ 25% | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Abdelgawad (2011) [70] | 12/12 | 10m, 2f, 41 (20–61) yo | x-ray | Percentage of tibial plafond | All ≥ 30% of tibial plafond | Fixation of PMF done if ≥ 30% of tibial plafond and more than 2 mm displaced after closed reduction (12) with PL approach | ≥ 30% | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Xu (2012) [53] | 102/102 | 41m, 61f, 43.4 (15–80) yo | x-ray | Percentage of articular surface | PMF < 10% (16), PMF 10–25% (62), PMF ≥ 25% (24) | 42 of 102 surgically fixed; PMF < 25% fixed (18) unfixed (60) | No cut- off | Yes | n.r | n.r | Arthritis score for different PMF sizes differed greatly; difference in treatment effect between articular surface evenness and unevenness for all fragment; no difference in treatment effect between fixed and unfixed PMF (AOFAS; VAS) |

| Di Giorgio (2013) [106] | 18/18 | 12m, 6f, 44.2 (26–61) yo | x-ray | Percentage of articular surface | 8 of 18 with PMF; ≥ 25% (8) | Fixating PMF ≥ 25% and ignoring smaller fragments followed in 82% of patients (21); in 5 of 13 (38%) PMF ≥ 25% not fixated | ≥ 25% | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

|

Hoelsbrekken (2013) [107] |

82/82 | 31m, 51f, 52.8 (± 15,3) yo | x-ray | Percentage of articular surface | n.r | ORIF of PMF if the fragment ≥ 25% of the articular surface | ≥ 25% | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Hong (2014) [109] | 31/31 | 10m, 21f, 46 (20–76) yo | x-ray | Percentage of articular surface | PMF < 25% (21), PMF ≥ 25% (10); mean size 22.3% (range 6% to 46%) | 8 of 31 PMF fixed (≥ 25%) | ≥ 25% | No | n.r | n.r | Poorer functional outcome with increasing posterior malleolar fragment size (OMAS score) |

| Erdem (2014) [108] | 40/40 | 20m, 20f, 48.9 (24–51) yo | x-ray + CT | Percentage of articular surface | n.r | Surgical treatment if fracture > 20%, screws (20), plate (20) | ≥ 20% | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Evers (2015) [47] | 42/42 | 16m, 26f, 52.8 (19–86) yo | x-ray + CT | Percentage of joint surface involvement | Group I: 54,8% < 25% (23), group II: 45% ≥ 25% (19) | < 25% osteosynthesis (2), ≥ 25% osteosynthesis (14) | No cut- off | Yes | n.r | n.r | Patients with PMF fixation had higher probability achieving good AOFAS Score and therefore improved outcomes |

| Kim (2015) [110] | 36/36 | 16m, 20f, 58 (23–85) yo | x-ray | Percentage of articular surface | All ≥ 30% of the tibial plafond | All lateral transmalleolar approach and miniscrews fixation | ≥ 30% | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Verhage (2015) [111] | 243/243 | 114m, 129f, 52 yo | x-ray | Percentage of articular surface | Mean PMF size 16% (range 3–53%) | Fixation in 11 cases: 8x ≥ 25%, 3 × 5–25%, large posterior fragments reduced closed or percutaneously and fixed by 1- 2 AP screws | No cut- off | Yes | n.r | n.r | Fragments > 5% resulted in worse functional outcome than fragments < 5% (not statistically significant) |

| Choi (2015) [112] | 50/50 | 27m, 23f, 47.5 (25–75) yo | CT | Percentage of articular surface | Mean area 31.7% | ORIF with single oblique PL approach; included involvement of PMF < 25% | No cut- off | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Drijfhout van Hooff (2015) [71] | 131/131 | 55m, 76f, 51 (24–74) yo | x-ray | Percentage of joint surface | Small (< 5%, n = 20), medium (5–25%, n = 86), or large (≥ 25%, n = 25) | In 24 patients PMF fixed (mainly percutaneously in AP direction) | No cut- off | Yes | n.r | n.r | No difference in outcome comparing small PMF to medium and large fragments (AOFAS, AAOS, VAS,RoM); patients with PMF > 5% developed more OA; anatomical fixation of PMF between 5 and 25% may lead to improved outcome |

| Endo (2016) [113] | 20/20 | 15m, 5f, 47 (18–67) yo | CT | Percentage of articular surface | n.r | PMF ≥ 25% fixed with 1—2 screws; PMF < 25% of the articular surfaces were fixed depending on surgeons preference | No cut- off | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Chan (2016) [114] | 254/254 | 106m, 148f, 45.1 (13–83) yo | x-ray + CT | One-third of the articular surface | 95 of 256 with PMF | Only 13 with fixation (fixed with guide pins through PL approach if displaced > 2 mm and involved > 1/3 size) | ≥ 1/3 | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Guo (2017) [54] | 284/284 | 156m, 128f, 39.12 (± 12.23) yo | CT | Percentage of joint surface involve-ment | < 25% (239), ≥ 25% (44) | Fixation ≥ 25% (40) < 25% (72) AP screws; no fixation ≥ 25% (4) < 25% (168) conservatively | No cut- off | Yes | n.r | n.r | PMF < 25%: no difference in outcomes fixed vs. not fixed in tibial spiral fx; PMF > 25% significantly improved clinical outcome with fixation (AOFAS; VAS) |

| Naumann (2017) [115] | 1011/1011 | 455m, 556f, 51.4 (18–94) yo | x-ray | ≥ ¼ of the articular surface | 235 of 1011 with PMF | ORIF if PMF ≥ 1/4 of the articular surface | ≥ 25% | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Vidovic (2017) [116] | 46/46 | 28m, 18f, 52.3 (33–71) yo | CT | Percentage of articular surface | All ≥ 25% of articular surface | Indirect reduction and percutaneous AP fixation (22); direct reduction and PA fixation (24) | ≥ 25% | No | n.r | n.r | Significantly better quality of reduction with direct reduction |

| Shi (2017) [117] | 116 | 59m, 57f, 48.6 (± 13.36) yo | x-ray + CT | Percentage of articular surface | All ≥ 25% of articular surface | Direct fixation (plate or screw) (64), indirect fixation (ligamentotaxis) (52) | ≥ 25% | No | n.r | n.r | Direct reduction technique provide better quality of fracture reduction and outcome of PMF > 25% (AOFAS) |

| Saygili (2017) [55] | 73/73 | 34m, 39f, 42.65 (± 13.68) yo | x-ray | Percentage of joint surface | All < 25% of joint surface | PMF fixation (10 × screw, 17 × plate), no fixation (46) | ≥ 25% | Yes | n.r | n.r | PMF fixation vs no fixation had no significant difference (AOFAS) |

| Zhou (2017) [119] | 34/34 | 15m, 19f, 41.2 (21–71) yo | 3DCT | Percentage of distal articular tibia | All ≥ 25% of articular surface (1/4–1/3(19), 1/3–1/2 (11), ≥ 1/2 (4)) | ORIF: plates and screws via a PL approach | ≥ 25% | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Wang (2017) [120] | 84/84 | 39m, 45f, 44.16 (15–75) yo | CT | Percentage of articular surface | 40 of 84 patients with PMF ≥ 25% |

PMF ≥ 25% fixed with 2 screws via PL approach; PMF remain untreated when fracture < 25% |

≥ 25% | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Xing (2018) [121] | 30/30 | 19m, 11f, 30 (22–65) yo | x-ray + CT | Percentage of articular surface | All ≥ 25% of articular surface | PMF fixed with screw or Kirschner wire | ≥ 25% | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Baek (2018) [122] | 29/29 | 20m, 9f, 31.3 (17–55) yo | x-ray + CT | Percentage of articular involve-ment | 19 of 29 with PMF | n.r | ≥ 20% | No | n.r | n.r | 71.4% of the patients with malreduced syndesmosis had associated PMF without fixation since < 20% size |

| Levack (2018) [123] | 178/178 | 63m, 115f, 50.2 (16.9) yo | CT | Percentage of 2-D tibial plafond area | 122 of 178 with PMF: 10% (60%), 10%–20% (28%), ≥ 20% (12%) | PMF reduced and with plate regardless of fracture size | No cut- off | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Kim (2018) [124] | 19/19 | 7m, 12f, 45.1 (13–68) yo | x-ray | Percentage of articular surface | All ≥ 25% of articular surface | Release of PITFL through PL approach for PMF reduction with posterior screws (19) | ≥ 25% | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Tosun (2018) [51] | 49/49 | 21m, 28f, 47 (20–82) yo | CT | Percentage of articular surface | Mean size of PMF: 21.3% in group 1, 28.9% in group 2 | 29 × untreated PMF; group 2: PMF treated regardless size (surgeons preference) 8 of 20 PMF < 25% fixation: screw or plate | No cut- off | Yes | n.r | n.r | Recommend all PMFs to be fixed regardless of size (related to successful radiological and functional outcomes, AOSAF, OA) |

| Miller (2018) [125] | 198/198 | 69m, 129f, 48.86 (± 15,98) yo | x-ray | Percentage of articular width | Mean in prone group (n = 47): 22.2%, mean in supine group (n = 151): 15.2% | Prone: 100% fixation (46 × plate, 1 × syndesmotic); supine: 24.5% fixation (37) (2 × plate, 41 × syndesmotic) | No cut- off | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

|

Huang (2018) [126] |

111/111 | 72m,39f, 46.6 ± 16.1 yo | CT | Percentage of articular surface | 42 of 111 with PMF | Surgical treatment (19) PMF ≥ 25%, conservative treatment (23) | ≥ 25% | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Xing (2018) [127] | 69/69 | 41m,28f, 37.36 (20–67) yo | x-ray + CT | Percentage of articular surface | All at least 25% of the articular surface | PMF anatomically reduced by screw | ≥ 25% | no | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Baumbach (2019) [48] | 236/236 | 99m, 137f, 53.0 (± 18.3) (18–100) yo | CT | Percent tibial plafond depth | < 25% (169), ≥ 25% (67) | ORIF (48 < 25%, 30 > 25%), CRIF (14 < 25%, 30 > 25%), none (107 < 25%, 7 > 25%) | No cut- off | Yes | n.r | n.r | All PMF independent of size should be treated by ORIF, as this restores syndesmotic stability significantly more often than untreated PMF |

| Kang (2019) [49] | 62/62 | 35m, 27f, 50.7 (19–78) yo | CT | Percentage of tibial joint surface | All affecting > 10%—< 25% of the tibial joint surface | 32 × screw fixation; 30 × internal fixation malleolar fractures and no screw fixation PMF | No cut- off | Yes | n.r | n.r | Surgical fixation of PMF < 25% results in better clinical outcome (AAOS, FS-36, FAOS) |

| Meijer (2019) [132] | 104/104 | 41m, 63f, 63 (37–91) yo | x-ray | Percentage of articular surface | n.r | 25% cut-off; fixation of PMF in 19 fixated (18%) with AP or PA screw | ≥ 25% | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Meijer (2019) [131] | 31/31 | 12m, 19f, 46 (19–73) yo | Q3DCT | Percentage of articular surface | Mean articular surface of 12% (range 0.0%–36.0%) of the joint surface | All ORIF: direct fixation (14), syndesmotic screw (4), no fixation (13) | No cut- off | Yes | n.r | n.r | Fragment size was correlated with arthrosis; no significant correlations were found for FAOS and SF-36 scores |

| Testa (2019) [133] | 48/48 | 22m, 26f, 44.7 (19–72) yo | x-ray | Percentage of articular surface | Mean fragment size 18%, mean fragment size fixing 26%, 13 of 48 ≥ 25% | Fixation of PMF in 8 of 48 when PMF ≥ 25%, fixed with screws | ≥ 25% | No | n.r | n.r | No correlation between size of PMF and ankle dislocation and size of PMF and syndesmosis stability |

| Verhage (2019) [72] | 169/169 | 67m, 102f, 52.3 yo | x-ray | Percentage of intra-articular surface | < 5% (20), 5–25% (119), ≥ 25% (30) | 39 × Fixation of PMF: none of < 5% were fixated, 15 of the 5–25% fixated,24 of ≥ 25% fixated | No cut- off | Yes | n.r | n.r | Size and fixation of PMF not associated with OA or outcome; postoperative step-off as risk factor |

| Pilskog (2020) [56] | 130/130 | 36 m, 94f, 57 (41–67) yo | x-ray | Percentage of joint involve-ment | Median PMF size 17%; 65 PMF < 25% (31 × fixation, 35 × no fixation) | PMF fixation in 42 of 43 (98%) in group A, 7 of 43 (16%) in group B | No cut- off | Yes | n.r | n.r | PMF < 25% fixed vs. not-fixed same SEFAS, RANS-36, VAS |

| Blom (2020) [63] | 70/70 | 30m, 40f, 47 (SD 14.6) yo | CT | Percentage of tibial articular surface | Mean of 15.9% of articular surface | According to AO principles of ORIF | No cut- off | Yes | n.r | n.r | PMF morphology and not size found as predictor of FAOS score |

| Wang (2020) [138] | 243/243 | 120m, 123f, 44.27 (± 12,5) yo | CT |

FAR from CT crossectional images |

≥ 15% (136) and < 15% (107) | All ORIF: reduction of PMF via PL approach, PA/ AP screws and PA plate used | No cut- off | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| McHale (2020) [50] | 75/75 | 24m, 51f, 56.2 yo | x-ray | Percentage of fragment size | < 10% (34), 10–20% (18), 20–30% (12), ≥ 30% (11) | 25 of 75 fractures fixed (surgeons preference) using PL approach (22 × plate, 3 × PA screw) | No cut- off | Yes | n.r | n.r | Worse outcome (MOXFQ, EQ-5D VAS) when PM size 10–20%, due to higher rate of anatomic reduction when fixed; best PROMs in PMF < 10% |

| Lee (2020) [134] | 166/166 | 97m, 69f, 44.6 (18–83) yo | CT | Percentage of intra-articular surface | 92 of 166 Fx with PMF (51 ≥ 25%) | Screw fixation PMF ≥ 25% and no long proximal extension; additional plate with PMF ≥ 25% and long proximal extension | ≥ 25% | No | n.r | n.r | Incidence of chronic syndesmotic instability higher, regardless of PMF fixation |

| Liu (2020) [141] | 85/85 | 48m, 37f, 42.92 (21–66) yo | not clear | Percentage of articular surface | All ≥ 25%; exclusion: medial malleolus extension type of PMF | plate group (n = 47), screw group (n = 38) | ≥ 25% | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Palmanovich (2020) [62] | 85/85 | 23m,62f, 53.4 (17–89) yo | CT |

1/3 of antero-posterior curvature of articular surface |

All over 1/3 articular surface | Single PA screw fixation | ≥ 1/3 | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Lee (2020) [139] | 70/70 | 41m, 29f, 51.0 (18–78) yo | CT | Percentage of articular surface | n.r | PMF not fixed if no rotation or displacement, if PMF ≥ 20% fixation | ≥ 20% | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Ceccarini (2021) [144] | 135/135 | 82m, 53f, 38.2 (19–50) yo (9 lost to FU) | x-ray | Percentage of articular surface | n.r | ≥ 25% fixation with screw in AP or PA direction | ≥ 25% | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Schoen- makers (2022) [78] | 26/26 | 10m, 16f, 58.08 ± 18.9 (22–78) yo | CT | Percentage of surface area | < 10% (6), 10%–25% (14), > 25% (6) | Surgical treatment 14 of 26 (9 × 10–25%, 4x > 25%) | No cut- off | Yes | n.r | n.r | Optimal value for PMF size to predict excellent AOFAS score was < 15%; PMF size ≤ 10% had a significantly greater RoM |

| Yamamoto (2022) [57] | 110/110 | 44m, 66f, 52.5 ± 12.9 yo | CT | Percentage of intra-articular surface | < 25% ( 62), > 25% (48) | n.r | No cut- off | Yes | n.r | n.r | PMF < 25% fragment reduction, fixation, and ankle stability not associated with AOFAS score; |

| Pflüger (2022) [24] | 193/193 | n.r | CT | Proportion of PMF in relation to tibial diameter | 0%-10% (11), 11%-15% (20), 16%-20% (30), 21%-25% (54), 26%-30% (36), 31%-35% (15), > 35% (27) | Surgical fixation PMF with larger size compared to without, no influence of size on direct or indirect fixation method | No cut- off | Yes | n.r | n.r | n.r |

Haraguchi classification

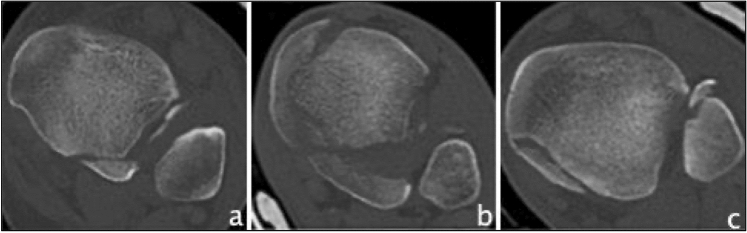

The first CT-based classification found, was developed 2006 by Haraguchi et al. which classified PMF into 3 distinct types [14]. Type I is described as a posterolateral-oblique wedge-shaped fragment involving the posterolateral corner of the tibial plafond, type II as a transverse medial-extension fracture line extending from the fibular notch to the medial malleolus, and type III is characterized as a small-shell type fragment at the posterior lip of the tibial plafond (Fig. 2). So far, Haraguchi's classification has been mentioned in 101 studies and was applied in 44 of them, which were, therefore, included and can be seen in Table 4. Three studies reported on the reliability of the classification, all showing substantial interobserver reliability (Fleiss kappa 0.70/Cohen’s kappa 0.799/Cohen’s kappa 0.797) and substantial to almost perfect intraobserver reliability (Fleiss kappa 0.77/Cohen’s kappa 0.985) [24, 32, 59]. Modifications of the Haraguchi classification were found three times. Kumar et al. divided Haraguchi type II into subtype A: a single fracture line extending from the fibular notch of the tibia to the medial malleolus, and subtype B: a posterior fracture lines forming 2 separate fragments, which was also applied by Sheikh et al. [60]. Wang et al. also modified Haraguchi type II by categorizing the fracture line into an anterolateral oblique line (subtype I) and into a small avulsion (subtype II) [61]. Palmanovich et al. divided the posterior segment by a central line, perpendicular to the bimalleolar line, into medial and lateral sub-segments, creating a 4-quadrant grid; each posterior malleolar fracture was then categorized based on the fragment’s location into “postero-lateral”, “postero-medial” and “postero-central” [62]. In terms of predictive values, type II fractures were regarded to show worse outcome [19, 59, 63], have higher presence of osteoarthritis [59], and are more likely to require placement of 2 syndesmotic screws [41]. The use of a posteromedial approach for type II fractures have resulted in good Olerud and Molander ankle score (OMAS)[64]. Mertens et al. observed an improving AOFAS score from type I to type III [65], Xie et al. found most intercalary fragments (more than 2/3) in type I fractures [28], and Kang et al. reported a better outcome with surgical treatment of type I fractures smaller than 25% [49].

Fig. 2.

Overview of the Haraguchi classification based on CT images (axial views). a Haraguchi type I b Haraguchi type II c Haraguchi type III

Table 4.

Studies reporting on the Haraguchi classification

| Study | Patients/ ankles |

Sex/ age |

PMF type distribution | Treatment allocation | Assesing Classification | Reliability | Predictive outcome values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inter OR |

Intra OR |

|||||||

| Haraguchi (2006) [14] | 57/57 | 41m, 16f, 43 (13–80) yo | Type I (38), type II (11), type III (8) | Type I: ORIF only when persistent intra-articular displacement; type II: only fixation of medial fragment and one-part fragments | Yes | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Erdem (2014) [108] | 40/40 | 20 m, 20f, 48.9 (24–51) yo | Type I (28), type II 10), type III (2) | Screws (20), plate (20) via PL approach | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Mangnus (2015) [20] | 45/45 | n.r | Type I (13), type II (15), type III (17) | n.r | Yes | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Choi (2015) [112] | 50/50 | 27m, 23f, 47.5 (25–75) yo | Type I (21), type II (29), type III (0) | Single oblique PL approach for ORIF (37 × screw, 3 × buttress plate) | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| de Muinck Keizer (2016) [40] | 28/28 | n.r | Type I (17), type II (8), type III (3) | n.r | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Bali (2017) [64] | 15/15 | 9m, 6f, 37.8 yo | Only type II | PM approach for type II fixation | No | n.r | n.r | Good functional outcome using posteromedial approach (OMAS) |

| Zhong (2017) [118] | 48/48 | 18m, 30f, 43.4 ± 12.7 (18–64) yo | Type I (26), type II (13), type III (9) | AP screws using PM approach (20), PA screws using PL approach (28) | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Saygili (2017) [55] | 73/73 | 34m, 39f, 42.65 ± 13.68 yo | Type I (39), type II (28), type III (6) | ORIF: posterior plate (17) percutaneous screw fixation (10) | Yes | n.r | n.r | Correlation was found between PMF ratio and Haraguchi type I and II fractures |

| Yi (2018) [95] | 107/107 | 43m, 64f, 46.58 ± 15.5 yo | Type I (76), type II (30), type III (1) | n.r | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Kumar (2018) [80] | 56/56 | 48m, 8f, 34.7 ± 11.7 yo | 16 of 56 with PMF; type I (9), modified type II into subtypes:A (3);B (1); type III (3) | Prefer a PL incision in type I and a PM incision in type II, both PM and PL incisions preferred in type IIB | Yes | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Huang (2018) [126] | 111/111 | 72m,39f, 46.6 ± 16.1 yo | 42 of 111 with PMF: type I (41), type II (0), type III (1) | Surgical treatment (19), conservative treatment (23) | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Kim (2018) [124] | 19/19 | 7m, 12f, 45.1 (13–68) yo | Type I (13), type II (6), type III (0) | Release of PITFL through PL approach for PMF reduction with posterior screws (19) | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Sobol (2018) [41] | n.r./193 | n.r | 24 of 193 with PMF: type I (18), type II (6), type III (0) | All type II with 2 AP screws, type I: screws (16), plate (1), no fixation (1); single syndesmotic screw (3 type I, 1 type II) | Yes | n.r | n.r | Type II were significantly more likely than type I fractures to have 2 screws placed |

| Hendrickx (2019) [129] | 164/164 | 118m, 46f, 41.7 (14–90) yo | 36 of 164 patients with PMF, 2 CTs insufficient: type I (33), type II (1), type III (0) | n.r | No | n.r | n.r | Type I was the pattern specific to PMF associated with tibial shaft fractures |

| Baumbach (2019) [48] | 236/236 | 99m, 137f, 53.0 ± 18.3 (18–100) yo | Type I (112), type II (81), type III (43) | ORIF: type I (44), type II (34), type III (0); CRIF: type I (15), type II (28), type III (1); no fixation type I (53) type II (19), type III (42) | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Blom (2019) [19] | 73/73 | 30m, 43f, 48 ± 14.8 yo | Type I (20), type II (21), type III (32) | Type I: direct fixation (8), non-direct fixation (6), no fixation (6); type II: direct fixation (13), non-direct fixation (1), no fixation (7); type III: direct fixation (1), non-direct fixation (20), no fixation (11) | Yes | n.r | n.r | Type II: worse outcome (FAOS, symptoms, pain, ADL) |

| Kang (2019) [49] | 62/62 | 35m, 27f, 50.7 (19–78) yo | Only type I involving < 25% of the articular surface | 32 × screw fixation for PMFs (group A), 30 × internal fixation for malleolar fractures without screw fixation for PMFs (group B) | Yes | n.r | n.r | Surgical fixation of type I PMFs involving < 25% of the articular surface results in better clinical outcome (AAOS, FS-36, FAOS) |

| Kellam (2019) [130] | 115/115 | 52m, 63f, 47 (16–93) yo | Type I (62), type II (43), type III (10) | PMF in tibial shaft fractures: 50 (93%) underwent direct surgical fixation, PMF in ankle fx: 38 (63%) direct surgical fixation | Yes | n.r | n.r | PMF in tibial shaft fx: 14 (47%) of type II injuries had additional fracture line oriented in the sagittal plane (fx pattern unique to these injuries) and more frequently extended to include MM |

| Meijer (2019) [131] | 31/31 | 12m, 19f, 46 (19–73) yo | Type I (17), type II (7), type III (7) | Type I: fixation (8), no fixation (9); type II both fragments fixed (3)(2xplate, 1 × AP screws),only PL fragment (4); type III: syndesmotic screw (2), no fixation(5) | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Mitchell (2019) [42] | n.r./122 | n.r | 59 of 122 with PMF; 44 of 59 with CT data: type I (41), type II (3), type III (0) | 30 treated with 1—2 screws, 29 treated nonoperatively | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Sheikh (2019) [60] | 20/20 | 11m, 9f, 50.4 (22–76) yo | Modified after Kumar: Type I (10), type IIA (5), type IIB (4), type III (1) | n.r | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Yang (2020) [136] | 27/27 | 11m, 16f, 61.5 (53–67) yo | Only type II | ORIF (combined posterolateral and posteromedial approach) | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Mertens (2020) [65] | 50/50 | 24m, 26f, 54 (21–83) yo | Only 46 of 50 patients classified: type I (23), type II (20), type III (3) | All ORIF (plate osteosynthesis) | Yes | n.r | n.r | Improving clinical outcomes (AOFAS score) from type I to type III |

| Blom (2020) [63] | 70/70 | 30m, 40f, 47 ± 14.6 yo | Type I (23), type II (22), type III (25) | Type I: direct fixation (10), non-direct fixation (7), no fixation (6); type II: direct fixation (16), non-direct fixation (1), no fixation (5); type III: direct fixation (1), non-direct fixation (20), no fixation (4) | Yes | n.r | n.r | Type II with poorer FAOS; Type I: quality of reconstruction of tibial articular surface as predictive factor; Type III: quality of syndesmosis stabilization as predictive factor |

| Wang (2020) [138] | 78/78 | 40m, 38f, 49.05 ± 15.97 yo | Created subtypes of type II: Type I (40), type II (38) | n.r | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Zhang (2020) [135] | 106/106 | 59m, 47f, 47.3 (21–75) yo | Only type I | n.r | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Wang (2020) [137, 140] | 48/48 | 13m, 35f, 48.9 (16–82) yo | Type I (25), type II (18), type III (5) | All were treated surgically (33 underwent ORIF: 5 × plates, 28 × screws) | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| He (2020) [140] | 41/41 | 32m, 9f, 37.9 (18–61) yo | 34 of 41 patients with PMF: type I (20), type II (4), type III (10) | n.r | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Palmanovich (2020) [62] | 85/85 | 23m,62f, 53.4 (17–89) yo | Modified Haraguchi: 61 cases “postero-lateral” 4 cases “postero-medial” 20 cases “postero-central” | Mean trajectory angle for single PA screw was 21° lateral for “postero-lateral” fragments, 7° lateral for “postero-central” fragments, and 28° medial for “postero-medial” | Yes | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Martin (2021) [142] | 28/28 | 16m, 12f, 36 (19–69) yo | Type I (13), type II (14), type III (1) | Posterior arthroscopic reduction and internal fixation | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Yu (2021) [143] | 76/76 | 49m, 27f, 47.2 ± 13,5 yo | Only type I | Percutaneous PA and AP screw fixation | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Quan (2021) [79] | 95/95 | 28m, 67f, 50.07 (20–83) yo | Type I (66), type II (19), type III (10) | n.r | Yes | n.r | n.r | Most multifragment fractures cannot be defined with Haraguchi classification |

| Black (2021) [145] | 279/279 | 93m, 186f, 55 ± 19 yo | Type I (161), type II (94), type III (24) | n.r | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Fidan (2021) [146] | 65/65 | 29m, 36f, 39.6 (18–89) yo | Type I (45), type II (12), type III (8) | Posterior plating via PL approach | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Erinç (2021) [147] | 86/86 | 53m, 33f, 41.70 ± 14.24 yo | Type I (27), type II (59), type III (0) | AP screw (50), ORIF (36) | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Sun (2021) [98] | 46/46 | 20m, 26f, 52.9 ± 14.1 yo | Type I (11), type II (38), type III (0) | Single-fragment type: posterior plate fixation with PL approach; double-fragment type: AP screw for PL fragment, PA screw for PM fragment | No | n.r | n.r | |

| Ræder (2021) [59] | 210/210 | 130m, 80f, 44.74 ± 14.63 yo | 125 of 210 with PMF: type I (61), type II (28), type III (36) |

Syndesmotic stabilization in all patients; 13% treated surgically (5 × type 1, 12 × type 2) |

Yes | C.kappa 0.797 | n.r | Presence of OA after 2 years ranged from 34% in type III group to 64% in type II group; type II had lower AOFAS score compared to no PMF |

| Schoenmakers (2022) [78] | 26/26 | 10m, 16f, 58.08 ± 18.9 (22–78) yo | Type I (11), type II (11), type III (4) | Surgical treatment in 14 of 26 | Yes | n.r | n.r | Classification showed no relationship with functional outcome |

| Kleinertz (2022) [32] | 113/113 | 37m, 76f, 56.2 ± 17.8 yo | n.r | n.r | Yes | C.kappa 0.799 | C.kappa 0.985 | n.r |

| Yamamoto (2022) [57] | 110/110 | 44m, 66f, 52.5 ± 12.9 yo | Only Type I if > 5% of joint surface and type II; type I (70), type II (40) | n.r | Yes | n.r | n.r | Postoperative complications associated with low AOSAF score but not reduction and fixation |

| Patton (2022) [149] | 153/153 | 46m, 107f, 51 ± 8 (18–89) yo | Type I (50), type II (49), type III (37), unclassifiable (5) | n.r | No | n.r | n.r | No association to Lauge-Hansen injury mechanism |

| Pflüger (2022) [24] | 193/193 | n.r | n.r | n.r | Yes | F.kappa 0.70 | F.kappa 0.77 | n.r |

| Sun (2022) [150] | 32/32 | 11m, 21f, 45.6 ± 6.3 (32–59) yo | Type I (20), type II (12), type III (0) | PL approach with distal locking plate | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

Bartoníček/Rammelt classification

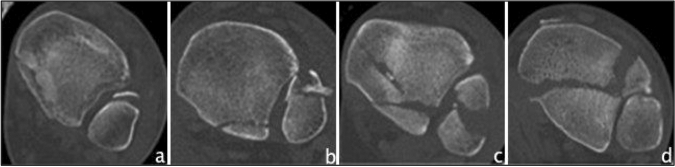

Another CT-based classification was presented by Bartoníček/Rammelt in 2015 [29]. Five different fracture types were defined: type 1 as an extraincisural fragment with intact fibula notch, type 2 as a posterolateral fragment including the fibula notch, a posteromedial two-part fragment extending to the medial malleolus as type 3 fracture, a posterolateral fragment larger than one-third of the notch as type 4 fracture, and finally irregular osteoporotic fragments as type 5 fracture (Fig. 3). It also includes a treatment algorithm. The Bartoníček/Rammelt classification has been found 46 times in the literature, of these, 21 studies have used it as a classification system, which were included in this study and are shown in Table 5. There is one modification made by Tucek et al., who divided Bartoníček type 4 into three subtypes: subtype 1 as a fracture line that passes laterally past the malleolar groove, subtype 2 as a fracture line that involves the malleolar groove, and subtype 3 as an intercollicular fracture line or a line involving the posterior colliculus [66]. Two studies reported reliability of the classification, both showing substantial interobserver reliability (Fleiss kappa 0.78/Cohen’s kappa 0.744) and almost perfect intraobserver reliability (Fleiss kappa 0.81/Cohen’s kappa 0.936) [24, 32]. Regarding the predictive outcome value, type 1 fractures showed to have better outcome than type 2 fractures [65], and a significantly improved clinical outcome was achieved in type 4 fractures when they were surgically fixed [54]. With increasing fracture type, clinical outcome became worse [1, 21, 63].

Fig. 3.

Overview of the Bartoníček/Rammelt classification based on CT images (axial views). a Bartoníček type 1 b Bartoníček type 2 c Bartoníček type 3 d Bartoníček type 4

Table 5.

Studies reporting on the Bartoníček/Rammelt classification

| Study | Patients/ ankles |

Sex/ age |

PMF type distribution | Treatment allocation | Assessing Classification | Reliability | Predictive outcome values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inter OR |

Intra OR |

|||||||

| Bartoníček (2015) [29] | 141/141 | 63m, 78f, 49 (19–83) yo | Type 1 (11), type 2 (74), type 3 (39), type 4 (13), type 5 (4) | Type 1: no fixation; type 4: ORIF, type 2–3: individual decision | Yes | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Evers (2015) [47] | 42/42 | 16m, 26f, 52.8 (19–86) yo | Type 1 (2), type 2 (5), type 3 (15), type 4 (2), type 5 (0)—only 24 CTs available | In 16 patients PMFs were fixated by osteosynthesis (75% direct, 25% indirect) | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Guo (2017) [54] | 284/284 | 156m, 128f, 39.12 (± 12.23) yo | Type 1 (0), type 2 (238), type 3 (5), type 4 (41), type 5 (0) | Type 2: fixation (82) no fixation (156), type 3 were all fixed, type 4: fixation (25) no fixation (16); fixation with AP screws | Yes | n.r | n.r | Type 2: no statistically significant differences in outcome operation vs. no operation; type 4: significantly improved outcome with fixation (AOFAS, VAS) |

| Yi (2018) [95] | 107/107 | 43m, 64f, 46.58 ± 15.5 yo | Type 1 (1), type 2 (50), type 3 (30), type 4 (26), type 5 (0) | n.r | No | n.r | n.r | PMF in SER group mainly had PL shape, PMF in PER group mainly had PM two-part shape or large PL triangular shape |

| Zhang (2018) [82] | 55/55 | 33m, 22f, 45.18 (24–83) yo | Type 1 (0), type 2 (9), type 3 (7), type 4 (39), type 5 (0) | Displaced PMF fixated with 1—2 PA screws | Yes | n.r | n.r | Highest rate of PMF violation in type 4, followed by type 3; potency of classification in directing treatment of PMF combined with distal tibial spiral fx confirmed |

| Bartoníček (2019) [128] | 54/54 | 33m, 21f, 48.2 (19–78) yo | 43 of 54 with PMF only 37 CTs, type 1 (5), type 2 (18), type 3 (11), type 4 (3), type 5 (0) | n.r | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Hendrickx (2019) [129] | 164/164 | 118m, 46f, 41.7 (14–90) yo | 36 of 164 with PMF, 2 CTinsufficient: type 1 (0), type 2 (12), type 3 (1), type 4 (21) type 5 (0) | n.r | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Yang (2020) [136] | 27/27 | 11m, 16f, 61.5 (53–67) yo | Only type 3 (27) | ORIF (combined PL and PM approach) | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Mertens (2020) [65] | 50/50 | 24m, 26ff, 54 (21–83) yo | Only 46 of 50 patients classified: type 1 (2), type 2 (17), type 3 (13), type 4 (14), type 5 (0) | All ORIF (plate osteosynthesis) | Yes | n.r | n.r | Type 1 show better postoperative results than type 2 (AOFAS score) |

| Blom (2020) [63] | 70/70 | 30m, 40f, 47 (SD 14.6) yo | Type 1 (16), type 2 (30), type 3 (22), type 4 (2), type 5 (0) | n.r | Yes | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Sultan (2020) [75] | 369/369 | 167m, 202f, 46.91 (18–85) yo | 247 of 369 with PMF: type 1 (22), type 2 (122), type 3 (54), type 4 (49), type 5 (0) | n.r | No | n.r | n.r | Type 3: highest incidence of intercalary fragment (70%) |

| Tucek (2021) [66] | 19/19 | 1m, 18f, 58 (20–76) yo | Only type 4 (19)- devided in subtypes 1 (11), 2 (4), 3 (4) | ORIF (PL approach 14x, PM approachl 5x) | Yes | n.r | n.r | Osteoarthritic changes in all four patients with subtype 3, ORIF with good functional results (AOFAS) |

| Maluta (2021) [1] | 46/46 | 18m, 28f, 55.63 ± 6.11 yo | Type 1 (22), type 2 (18), type 3 (6), type 4 (0), type 5 (0) | Immobilized with cast and no-weight bearing for 5 weeks | Yes | n.r | n.r |

Worse outcome with increase of injury severity after 2 years of FU (AOFAS, OMAS) |

| Neumann (2021) [21] | 100/100 | 31m, 69f, 60.0 (20–83) yo | Type 1 (7), type 2 (35), type 3 (25), type 4 (23), type 5 (0) | No fixation (37), AP screw (14), PA screw (13), plate (36) | Yes | n.r | n.r |

No significant postoperative outcome difference between type 1 to 4 (OMAS, FFI, AOFAS score) |

| Sun (2021) [98] | 46/46 | 20m, 26f, 52.9 ± 14.1 yo | Type 1 (0), type 2 (1), type 3 (36), type 4 (12), type 5 (0) | Single-fragment type: posterior plate fixation with PL approach; double-fragment type: AP screw for PL fragment, PA screw for PM fragment | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Black (2021) [145] | 279/279 | 93m, 186f, 55 ± 19 yo | Type 1 (20), type 2 (139), type 3 (93), type 4 (24), type 5 (3) | n.r | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Seo (2022) [148] | 153/153 | 71m, 82f, 48.1 ± 14.6 yo | Type 1 (27), type 2 (81), type 3 (30), type 4 (15), type 5 (0) | ORIF recommended when marginal impaction present, even in small type 2 PMFs | Yes | n.r | n.r | Marginal impaction associated with PMF highly observed in type 2 (58%) |

| Kleinertz (2022) [32] | 113/113 | 37m, 76f, 56.2 ± 17.8 yo | n.r | n.r | Yes | C.kappa 0.744 | C.kappa 0.936 | n.r |

| Patton (2022) [149] | 153/153 | 46m, 107f, 51 ± 8 (18–89) yo | Type 1 (10), type 2 (68), type 3 (44), type 4 (13), type 5 (0), unclassifiable (6) | n.r | No | n.r | n.r | No association to Lauge-Hansen injury mechanism |

| Pflüger (2022) [24] | 193/193 | n.r | n.r | n.r | Yes | F.kappa 0.78 | F.kappa 0.81 | n.r |

| Sun (2022) [150] | 32/32 | 11m, 21f, 45.6 ± 6.3 (32–59) yo | Only type 4 (32) | PL approach with distal locking plate | Yes | n.r | n.r | n.r |

Mason classification

In 2017, Mason et al. developed a CT-based classification of PMF ascending in severity of injury [30]. Therefore, Mason described type 1 as an extra-articular avulsion fracture following a rotational force applied to the foot when the ankle is in plantarflexion and the talus unloaded. Rotational forces applied to a loaded foot result in a type 2A fracture in form of a primary triangular posterolateral fragment. A type 2B fracture with a secondary posteromedial fragment, usually angled at 45° to the primary fragment, occurs when the talus continues to rotate in the mortise. A type 3 fracture is characterized by a coronal fracture line that involves the entire posterior plafond due to an axial loading of a plantarflexed talus (Fig. 4). Until now, Mason's classification has been mentioned 22 times in literature, and used for classification in 12 studies, which were included and can be found in Table 6. One modification of Mason type 2B fracture was found. Vosoughi et al. divided it into a large intra-articular pilon fragment and a small extra-articular fragment [67]. Interobserver reliability ranged from substantial to almost perfect values (Cohen’s kappa 0.919/Fleiss kappa 0.61/Cohen’s kappa 0.717) as did intraobserver reliability (Fleiss kappa 0.65/Cohen’s kappa 0.957) [24, 30, 32]. As for the predictive outcome value, type 3 fractures tend to show worse postoperative outcome [68].

Fig. 4.

Overview of the Mason classification based on CT images (axial views). a Mason type 1 b Mason type 2A c Mason type 2B d Mason type 3

Table 6.

Studies reporting on the Mason classification

| Study | Patients/ ankles |

Sex/ age |

PMF type distribution | Treatment allocation | Assesing Classification | Reliability | Predictive outcome values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inter OR |

Intra OR |

|||||||

| Mason (2017) [30] | 121/121 | 49m, 72f, 48 (17–90) yo | Type 1 (41), type 2A (30), type 2B (25), type 3 (25) | Type 1: no fixation; type 2A: ORIF; type 2B: ORIF, medial fragment first; type 3: ORIF | Yes | C.kappa 0.919 | n.r | In type 1 syndesmosis was disrupted in 100% of cases |

| Jayatilaka (2019) [43] | 80/80 | n.r., 48.1 (17–90) yo | Only type 2 (33 type 2A, 47 type 2B) | n.r | Yes | n.r | n.r | Rate of syndesmotic injury greater in type 2A than type 2B, although type 2B had greater extent of bone injury |

| Vosoughi (2019) [67] | 47/47 | 11m, 36f, 46.6 (17–90) yo | Only type 2B | Large pilon intra-articular fragment (29): fixation; small extra-articular avulsion fragment (18): secondary syndesmotic stabilizer | Yes | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Mason (2019) [68] | 50/50 | 22m, 28f, 46.8 (21–87) yo | Type 1 (17), type 2A (12), type 2B (10), type 3 (11) | Type 1: syndesmotic fixation; type 2A: ORIF; type 2B: ORIF (medial fragment first) type 3: ORIF | Yes | n.r | n.r | Type 3 fractures tend to worse postoperative outcome (OMAS) |

| Philpott (2020) [44] | n.r./86 | n.r | Only type 2 (2A (33), 2B (34)) and type 3 (19) | ORIF (not homogenous fracture paterns → different appraches) | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Lee (2020) [134] | 166/166 | 97m, 69f, 44.8 (18–83) yo | PMF in 92 of 166 Fx; type 1 (34), type 2A (18), type 2B (16), type 3 (24) | n.r | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Yang (2020) [136] | 27/27 | 11m, 16f, 61.5 (53–67) yo | Only type 2B | ORIF (combined posterolateral and posteromedial approach) | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Gandham (2020) [83] | 141/141 | 54m, 87f, 49.2 (17–90) yo | Type 1 (45), type 2A (41), type 2B (35), type 3 (20) | Type 1: syndesmotic fixation or PL approach; type 2A: PL approach, type 2B: combined MPM and PL approach, PM approach for almost all type 3 fx | Yes | n.r | n.r | n.r |

| Xie (2021) [28] | 108/108 | 34m, 74f, 49 (18–89) yo | Type 1 (12), type 2A (71), type 2B (22), type 3 (3) | n.r | Yes | n.r | n.r |

IAIF was found in more than 2/3 cases of single fragment fractures (type 2A) |

| Kleinertz (2022) [32] | 113/113 | 37m, 76f, 56.2 ± 17.8 yo | n.r | n.r | Yes | C.kappa 0.717 | C.kappa 0.957 | n.r |

| Pflüger (2022) [24] | 193/193 | n.r | n.r | n.r | Yes | F.kappa 0.61 | F.kappa 0.65 | n.r |

| Sun (2022) [150] | 32/32 | 11m, 21f, 45.6 ± 6.3 (32–59) | Type 1 (0), type 2A (10), type 2B (0), type 3 (22) | PL approach with distal locking plate | No | n.r | n.r | n.r |

Quality assessment of included studies

The Coleman score achieved a total median value of 43.5 points (14–79), composed of Part A with a median of 26 points, and Part B with 18 points. Based on the number of patients included, the weighted median total Coleman score was 42.5. Coleman score points are shown in Table 1.

Discussion

By reviewing the literature, 4 classifications were found describing PMF: a classification based on the fragment proportion in relation to the distal tibial joint surface [45] and the three CT-based classifications according to Haraguchi, Bartoníček/Rammelt, and Mason [14, 29, 30]. The earliest and most commonly used classification was the PMF Classification according to fracture size as first specified by Nelson and Jensen, who postulate a recommendation for treatment of PMF with a fragment size exceeding more than 1/3 of the articular surface on lateral radiographs based on a study sample consisting of 8 patients [45]. With 66 included studies, this classification accounts for the largest proportion of classifications used by surgeons in clinical practice. In the included studies the most used cut-off value was 25%, but also values of 20%, 30% or 1/3 of the articular surface were used.

There are still controversial opinions for osteosynthetic treatment of PMF [69]: McDaniel and Wilson demonstrated, that if a PMF of less than 25% of the tibial joint area was not reduced, it did not significantly affect the overall outcome [58]. De Vries et al. and Xu et al. found no evidence for fixing PMF smaller than 25%, as outcome scoring systems showed no significant better outcome [52, 53], as well as Guo et al. for PMF in tibial spiral fractures [54]. Comparing the outcome of treating PMF less than 25% with that of not fixing it no significant difference in the AOFAS Score was found [55–57]. On the other hand, a trend toward better clinical and radiological outcome in patients in whom PMF was fixed was observed and, therefore, authors recommend PMF fixation of even smaller fragments that cannot be satisfactorily reduced by ligamentotaxis [6, 46, 47, 49, 50]. Baumbach et al. and Tosun et al. postulated even that in PMF of all sizes, syndesmotic stability is significantly more likely to be restored if treated by open reduction internal fixation [48, 51]. In relation to the total number of studies using this classification, the number of studies in terms of predictive outcome values is rather limited. In the matter of inter- and intraobserver reliability, the available evidence is also meager, Büchler et al. were the only ones to study this, providing good results with an inter- and intraobserver reliability of kappa of 0.64 and 0.63, respectively [13]. Of all studies that asses the PMF classification according to fracture size, all but two [6, 49] are of retrospective design. Especially in the earlier studies, the evaluation of the fracture was not optimal, since this was done mainly on the basis of lateral radiographs.

The use of radiographs was found to be limited for the accurate size estimation of PMF [12, 14, 18, 70], therefore, it recently came to the increasing use of computed tomography (CT) in the diagnosis of trimalleolar ankle fractures [18, 47, 54]. Subsequently, the conviction increases that not the size, but the fracture morphology is crucial for the improvement of outcome [19]. Factors such as syndesmotic stability, joint congruity, postoperative step-off, reconstruction of the incisura, intercalary fragments and talar subluxation are thought to be of prognostic importance to consider when treating PMF [7, 23, 48, 50, 51, 53, 58, 63, 71–76]. Hence, a paradigm shift has occurred [21, 24, 31, 77], as also the systematic review by Odak et al. has previously shown [22].

This is where the three CT-based classifications come to the fore. The classification used in the majority of studies is the one proposed by Haraguchi [14]. Most probably due to being the first CT-based classification and due to the simple and clear structure dividing the fracture in three types. Since 2015, however, a preference for the Bartoníček/Rammelt classification has emerged, with the main strengths of this classification being the ascending severity of the classification and the derived therapy recommendations [29]. After noting that the Haraguchi classification did not map the mechanism of injury, Mason developed the most recent classification, also considering the injury mechanism [30].

Some objections against Haraguchi’s classification have arisen with the time. First, the classification is not based on severity and thus does not relate to functional outcome [78]. Second, that the classification was based only on axial sectional images and, therefore, fractures were only assessed in one plane, vertical size expansion not being estimated [31], that medial injuries were not evaluated, which may lead to misjudgments [17, 32], and that the extent of involvement of the tibial incisura was not specified, wherefore type I fractures include a wide range of both small and large posterolateral fragments [59]. Most multi-fragmentary fractures cannot be defined using this classification [79]. Also, the three modifications found [61, 62, 80] may suggest that Haraguchi’s classification is not as advanced to represent all fracture types. Regarding the predictive value of the classifications in terms of postoperative outcomes, some authors have shown that type II fractures have worse clinical outcomes [19, 59, 63], whereas Mertens et al. observed an improvement in the AOFAS score from type I to type III [65].

The Bartoníček/Rammelt classification was developed on the basis of a larger patient population. It ascends in severity and contains a therapy recommendation [29, 81]. Zhang et al. were able to show that the potency of the Bartoníček/Rammelt classification also applies to distal tibial spiral fractures with associated PMF [82]. One objection is the imprecise definition of type 5 fractures, which includes all fractures that cannot be classified as type 1–4. We were not able to find an image of such a type 5 fracture: neither in the original article nor in our own fracture-database. Another objection is the difficulty of estimating 1/3 of the tibial incision to distinguish between a type 2 and type 4 fracture [32]. There is a consistent opinion on worse outcome with increasing fracture type [1, 63, 65]. Only Neumann et al. saw an increase in the AOFAS score and no difference in the Olerud and Molander ankle score (OMAS) [21].

The authors of the Mason classification see the advantage in the ascending degree of severity of the classification considering the accident mechanism. They have also introduced treatment recommendations based on their classification. Gandham et al. even made a recommendation on the appropriate operative approaches [30, 68, 83]. However, they described the classification using schematic drawings and also do not define the tibial incisura [32]. In addition, a multi-fragmentary fracture of the entire tibial plafond may be mistaken for a two-part posterolateral and posteromedial fracture (type 2B) [32]. With the exception of one study describing a worse outcome in Mason type 3 fractures [68], there are no further statements on predictive values. Until now, Mason’s classification has not yet been able to establish itself in literature with only 12 included studies. In addition, half of all studies using Mason’s classification were conducted by the author's own research group, and it was Mason himself who found the highest interobserver reliability in his study (kappa 0.919) whereas other authors found considerable lower reliability scores (Fleiss kappa 0.61 / Cohen’s kappa 0.717) [24, 30, 32, 43, 44, 67, 68, 83].

Intra- and interobserver reliability are substantial to perfect for all classifications, with Mason scoring the lowest in comparison to the other classifications [24, 32]. However, none of the classifications can adequately describe the complexity of posterior malleolus fracture, as factors such as extent of articular surface impaction, degree of dislocation or intercalary fragments among others are not taken into account [32, 79].

Several important classifications were excluded because they are not PMF-specific. This includes the AO classification originally published in 1987 by Müller/AO, being a universal classification depicting all skeletal injuries. It is a valuable, international classification, which has its justification, and which has been used for years [84, 85]. With the routine use of CT imaging to reliably diagnose and classify trimalleolar fractures [9], authors have shown that all fractures involve the articular surface of the distal tibia [14, 29, 81]. This in contrast to the specification of the AO’s classification through Heim, dividing posterior malleolar fractures into extra- and intra-articular fractures [86]. The AO classification, based on standard plain radiographs, is therefore not suitable for considering the significance and morphology of PMF, nor is it applicable in addressing specific questions regarding PMFs [24, 48, 87].

Classification systems of posterior pilon fractures were also considered to be non-PMF-specific. Hence, the differentiation of pilon fractures from trimalleolar ankle fractures still often causes difficulties in clinical practice [75, 88, 89]. This has led to the emergence of a subset of PMF, also known as the “posterior pilon” variant, which has recently gained popularity [61, 87, 90–93]. However, there is still no clear definition and the understanding of it varies [75, 81, 94, 95]. In addition, there are studies showing that posterior pilon fractures are a separate entity due to morphological differences [61, 94].

Other excluded classifications were sub-entities of PMF fractures. For example, a classification of PMF in tibial shaft fractures (TSF) [96, 97], and one also involving talar subluxation [98].

A few more limitations are worth noting, with majorly the limited quality of the included studies. Limitations affecting the Coleman score include the predominantly retrospective nature of the included studies and small patient cohorts. Therefore, the results of this study could only be presented in a descriptive manner. Only studies written in English were considered, excluding further useful contributions written in other languages.

In conclusion, this review demonstrates that there has been a shift from usage of the PMF classification by fracture size to the newer CT-based classifications, however, none have been able to establish itself in the literature so far. Summarizing all of the previously described points, we believe that, to date, no classification is able to adequately describe the complexity of the PMF. Also, the classifications are weak in terms of a derivable treatment algorithm or prognosis of outcome. According to this review, the Bartoníček/Rammelt classification has the most potential to prevail in the literature and in clinical practice due to its treatment algorithm, its reliability in combination with consistent predictive outcome values.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. No funding was received for conducting this study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the local ethics committee of the medical board in Hamburg, Germany (WF-093/21).

Informed consent

This study did not involve human participants.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Julia Terstegen and Hanneke Weel have contributed equally. In memoriam of Alexej Barg.

References

- 1.Maluta T, Samaila EM, Amarossi A, Dorigotti A, Ricci M, Vecchini E, Magnan B. Can treatment of posterior malleolus fractures with tibio-fibular instability be usefully addressed by Bartonicek classification? Foot Ankle Surg. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2021.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elsoe R, Ceccotti AA, Larsen P. Population-based epidemiology and incidence of distal femur fractures. Int Orthop. 2018;42(1):191–196. doi: 10.1007/s00264-017-3665-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Court-Brown CM, McBirnie J, Wilson G. Adult ankle fractures–an increasing problem? Acta Orthop Scand. 1998;69(1):43–7. doi: 10.3109/17453679809002355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaskulka RA, Ittner G, Schedl R. Fractures of the posterior tibial margin: their role in the prognosis of malleolar fractures. J Trauma. 1989;29(11):1565–70. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198911000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koval KJ, Lurie J, Zhou W, Sparks MB, Cantu RV, Sporer SM, Weinstein J. Ankle fractures in the elderly: what you get depends on where you live and who you see. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19(9):635–9. doi: 10.1097/01.bot.0000177105.53708.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tejwani NC, Pahk B, Egol KA. Effect of posterior malleolus fracture on outcome after unstable ankle fracture. J Trauma. 2010;69(3):666–9. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181e4f81e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Langenhuijsen JF, Heetveld MJ, Ultee JM, Steller EP, Butzelaar RM. Results of ankle fractures with involvement of the posterior tibial margin. J Trauma. 2002;53(1):55–60. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200207000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Broos PL, Bisschop AP. Operative treatment of ankle fractures in adults: correlation between types of fracture and final results. Injury. 1991;22(5):403–6. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(91)90106-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts V, Mason LW, Harrison E, Molloy AP, Mangwani J. Does functional outcome depend on the quality of the fracture fixation? Mid to long term outcomes of ankle fractures at two university teaching hospitals. Foot Ankle Surg. 2019;25(4):538–541. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Regier M, Petersen JP, Hamurcu A, Vettorazzi E, Behzadi C, Hoffmann M, Grossterlinden LG, Fensky F, Klatte TO, Weiser L, Rueger JM, Spiro AS. High incidence of osteochondral lesions after open reduction and internal fixation of displaced ankle fractures: Medium-term follow-up of 100 cases. Injury. 2016;47(3):757–61. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2015.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ebraheim NA, Mekhail AO, Haman SP. External rotation-lateral view of the ankle in the assessment of the posterior malleolus. Foot Ankle Int. 1999;20(6):379–83. doi: 10.1177/107110079902000607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferries JS, DeCoster TA, Firoozbakhsh KK, Garcia JF, Miller RA. Plain radiographic interpretation in trimalleolar ankle fractures poorly assesses posterior fragment size. J Orthop Trauma. 1994;8(4):328–31. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199408000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buchler L, Tannast M, Bonel HM, Weber M. Reliability of radiologic assessment of the fracture anatomy at the posterior tibial plafond in malleolar fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2009;23(3):208–12. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31819b0b23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]