Abstract

The coccolithophore Emiliania huxleyi shows a variety of responses to ocean acidification (OA) and to high-CO2 concentrations, but there is still controversy on differentiating between these two factors when using different strains and culture methods. A heavily calcified type A strain isolated from the Norwegian Sea was selected and batch cultured in order to understand whether acclimation to OA was mediated mainly by CO2 or H+, and how it impacted cell growth performance, calcification, and physiological stress management. Emiliania huxleyi responded differently to each acidification method. CO2-enriched aeration (1200 µatm, pH 7.62) induced a negative effect on the cells when compared to acidification caused by decreasing pH alone (pH 7.60). The growth rates of the coccolithophore were more negatively affected by high pCO2 than by low pH without CO2 enrichment with respect to the control (400 µatm, pH 8.1). High CO2 also affected cell viability and promoted the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which was not observed under low pH. This suggests a possible metabolic imbalance induced by high CO2 alone. In contrast, the affinity for carbon uptake was negatively affected by both low pH and high CO2. Photochemistry was only marginally affected by either acidification method when analysed by PAM fluorometry. The POC and PIC cellular quotas and the PIC:POC ratio shifted along the different phases of the cultures; consequently, calcification did not follow the same pattern observed in cell stress and growth performance. Specifically, acidification by HCl addition caused a higher proportion of severely deformed coccoliths, than CO2 enrichment. These results highlight the capacity of CO2 rather than acidification itself to generate metabolic stress, not reducing calcification.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00248-022-02035-3.

Keywords: Emiliania huxleyi, Ocean acidification, Calcification, pCO2, Photochemistry, Phytoplankton, Stress, Coccolithophores

Introduction

Over the twenty-first century, the ocean is projected to transition to unprecedented conditions relative to preindustrial levels [1]. The worst case-scenario (Representative Concentration Pathway RCP 8.5) [1, 2] predicts an atmospheric pCO2 increase above 1000 µatm with a concomitant reduction of 0.4 units in seawater pH in the upper layer of the ocean with respect to preindustrial levels; this process is known as ocean acidification (OA). OA is already altering the carbonate system (comprising the proportions of the different inorganic carbon forms maintained by the carbonate pump, the carbonate counter pump, and the solubility pump in the ocean) that controls seawater pH [3]. Carbon speciation is predicted to be highly affected, with an expected 17% increase in bicarbonate ions (HCO3−) and a 54% decrease in carbonate (CO32−) concentrations in equilibrium [4]. Thereupon, the saturation state of calcite (Ωcalcite) and the rain ratio (the ratio of calcite precipitation to organic matter production, RR) will also change [5, 6].

Increased CO2 concentration in seawater, and its accompanying acidification, may benefit some phytoplanktonic species while being detrimental to others. Calcifying organisms such as coccolithophores are suggested to be strongly impacted by OA [7]. Coccolithophores take up inorganic carbon (Ci) and produce both particulate organic carbon (POC) through photosynthesis and particulate inorganic carbon (PIC, CaCO3) via calcification [5]. The coccolithophore Emiliania huxleyi is a major calcifier in the world’s oceans and can account for 20% to total organic carbon fixation [5, 8] and up to 50% of CaCO3 flux to marine sediments [9, 10]. Its abundance and calcifying activity result in the paramount importance of this phytoplankton species [11, 12]. It contributes to the regulation of CO2 exchange across the ocean–atmosphere interface and to the biogeochemical cycles through the RR and the production of CO2 during calcification by means of the carbonate counter pump [5]. It also depends on the Ωcalcite since it is relevant to the maintenance of coccoliths after exocytosis [13]. E. huxleyi has a pangenome that provides this species with a high genome variability [14]. This is reflected in a plethora of alternative metabolic traits, a consequence of the ample metabolic repertoire displayed [14, 15]. Such genome variability underpins its capacity to thrive in habitats ranging from the equator to the subarctic, forming extensive blooms under a large variety of environmental conditions that can be seen from outer space [14, 16].

The response of E. huxleyi to carbonate chemistry variations has been studied both in the field using natural populations and in the laboratory using monocultures [7, 17–21]. When exposed to elevated CO2 and concomitantly low pH, E. huxleyi reduced its growth rate and its level of calcification in most of the experiments, leading to thinner coccospheres [22] and thus, imposing high stress to the cells that compromises their viability [15, 23]. However, there is still controversy on whether OA will promote or reduce calcification rates, since some experiments with this same species have resulted in conflicting responses [19, 22, 24–26]. For instance, it has been recently reported that some species of coccolithophores are able to maintain relatively constant ratios of calcification-to-photosynthesis under conditions of high CO2 by maintaining pH homeostasis at the site of coccolith forming vesicles [27].

Cell production has been described to be either unaffected or stimulated by increased pCO2 [20, and references therein]; however, calcification typically decreases with malformations of coccoliths being commonly observed [13, 28, 29]. Bach et al. [30] suggested that biomass production was stimulated by increased CO2 at sub-saturating conditions for photosynthesis, whereas calcification was specifically responsive to the associated decrease in pH. The “CO2 or pH issue” has been discussed for long regarding phytoplankton responses to OA, especially in coccolithophores [29]. Such differential CO2 and/or pH effects on biomass production and calcification seem to be due to acidification distorting ion homeostasis, thus shifting the metabolism from oxidative to reductive pathways [31, 32] and from HCO3− use to CO2 diffusive-only C uptake [33]. Differences also largely depend on the specificity of the strain, its calcification ability, and its life cycle [33].

The aim of the present work was to investigate the response of E. huxleyi (RCC 1226) from the Norwegian Sea to acidification, either by using increased pCO2 condition or by acidification of the media by adding HCl. Our target was to differentiate between CO2 or H+ ions effects on cell growth performance, calcification, and physiological stress management. For this purpose, we analysed the effects of the two acidification methods on: (1) cell abundance, (2) cell viability, (3) the photosynthetic and C acquisition performance, (4) oxidative stress, (5) calcification, and (6) morphology of the coccospheres.

Methods

Culture Conditions and Experimental Set-Up

Emiliania huxleyi (Lohmann) Hay et Mohler (RCC 1226) cells were provided by the Roscoff Culture Collection, France. This is a heavily calcified type A strain isolated from the Atlantic Ocean close to the Norwegian coast in July 1998. Cells were grown in 3 L sterile Perspex cylinders (Plexiglas XT® 29,080) in artificial seawater medium [34] enriched with f/2 nutrients [35]. Cultures were grown at 16 °C, 120 µmol photons m−2 s−1 photosynthetic active radiation (PAR, 400–700 nm), and at a 14:10 h light: darkness photoperiod. Irradiance was provided by fluorescent tubes of daylight type Osram Sylvania standard truelight 18 W, as measured by a submersible micro quantum sensor (US-SQS/L, Walz, Germany) connected to a Li-COR 250A radiometer. Cells were exposed to low pH (7.7, LP) by either aerating with air enriched with CO2 to 1200 µatm (HC-LP, high carbon and low pH) or by HCl additions in combination with non-enriched aeration (LC-LP, low carbon and low pH). The control condition consisted of non-acidified, non-enriched cultures at 400 µatm CO2 (LC-HP, low carbon and high pH). All treatments, including the control, consisted of triplicate cultures continuously stirred with a magnetic bar and aerated to ensure homogeneity without mechanical stress and to avoid cell shading. HC levels of CO2 were obtained by mixing atmospheric air with pure CO2 (Biogon®, Linde, Germany) to achieve 1200 µatm pCO2 inlet flow in each culture was measured by non-dispersive infrared analysis by using a CO2 gas analyser (LI-820, Li-COR) at 200 mL min−1. The air was filtered through Millipore 0.2 µm fiberglass filters (Merck, Germany). For lowering the pH with HCl, the required volume of 12 N HCl (Merck, Germany) was added to the culture medium until pH = 7.7 was reached prior to cells inoculation. The medium and stock cultures were pre-acclimated to the different pCO2 and pH conditions for 72 h in order to avoid transient effects [36] under the conditions described just above. The experiment lasted 9 days, and the 3 L cultures were sampled by extracting 175 mL on days 2, 4, 7, and at the end of the experiment, thus the remaining volume before last sampling was 82.5% of the initial.

Carbonate System (pCO2, DIC, Ωcalcite, pH, Alkalinity)

pCO2, DIC, and Ωcalcite were calculated from daily measurements of pH, temperature, salinity, and total alkalinity (TA) using the CO2Calc software [37] fitted using GEOSECS constants. pH was measured in all the cultures by using a pH-meter (CRISON Basic 20 +) calibrated daily using the NBS scale. Salinity was measured with a conductivity meter (CRISON 524). The accuracy of the pH-meter and conductivity meter were ± 0.01 pH units and ± 1.5%, respectively. TA was measured using the Gran’s potentiometric method [38]. No certified reference standards were used.

Cell Abundance and Growth Rates

Cell density was determined using an Accuri™ C6 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, USA) equipped with an air-cooled laser providing 15 mW at 488 nm and with a standard filter set-up by using 1 mL samples. The trigger was set on red fluorescence and samples were analysed for 90 s at an average flow rate of 14 μL min−1. Cells were discriminated on the basis of the side-scatter signal (SSC) versus chlorophyll [39, 40].

The growth rate (µ) was calculated by fitting the cell density data to the logistic growth model (Eq. 1):

| 1 |

where K refers to the loading capacity, N is the cell density at any given time, N0 is the cell density at time 0, µ is the intrinsic growth rate, and t is the time (in days). The logistic model was preferred over the exponential model because the cultures reached the stationary phase.

Chlorophyll a (Chl a) Concentration and In Vivo Chl a Fluorescence Associated to PSII

Samples of 5 mL were collected from each culture, centrifuged at 4000 g, and the pellet snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and kept at − 80 °C until analysis. Pellets were incubated overnight at 4 °C in N,N-dimethylformamide (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for Chl a extraction. The concentration was determined spectrophotometrically and calculated accordingly [41].

The optimal quantum yield (FV/Fm) for charge separation in photosystem II (PSII) is frequently used as an indicator of photoinhibition, reflecting the general status. In vivo chlorophyll a fluorescence of PSII was determined by using a pulse amplitude modulated fluorometer Water-PAM (Heinz Waltz, Effeltrich, Germany) as described by Schreiber et al. [42]. F0 and Fm were determined in 10-min dark-adapted freshly taken 2 mL culture samples, to ensure oxidation of primary quinone acceptor (QA), to obtain the FV/Fm. FV is the variable fluorescence of dark-adapted algae when all the reaction centres are opened as Fm − F0. Fm is the maximal fluorescence intensity with all PSII reaction centres closed obtained after an intense actinic saturation light pulse > 4000 µmol photons m−2 s−1, and F0 is the basal fluorescence (minimal fluorescence) of dark-adapted after 10 min. Using the software WinControl-3.25, rapid light curves (RLCs) were constructed and fitted to the nonlinear least-squares regression model of Eilers and Peeters [43] to obtain the initial slope of the curve related to the photosynthetic light-harvesting efficiency (αETR) (as an estimator of photosynthetic efficiency) and the relative maximal electron transport rate (rETRmax). The actinic light intensities were selected according to the saturation pattern and measured in the PAM cuvette using a US-SQS/L micro quantum sensor (Walz) attached to a Licor 250-A radiometer. The light requirement for saturating photosynthetic rate (Ek) and the maximum irradiance before photoinhibition of rETR was observed (Eopt) were derived from rETRmax and α and ß slopes, respectively, where ß is the slope of rETR decay at high irradiance.

Cell Viability and Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

Cell stress was studied by using the cellular green fluorescence emission of specific probes (Invitrogen, USA) added to samples cultured at each treatment [44]. Cell viability was assessed with fluorescein diacetate (FDA), and 0.4 µL of a 0.09 µM working stock was added to 1 mL samples. FDA is a nonpolar, non-fluorescent stain, which diffuses freely into cells. Inside the cell, the FDA molecule is cleaved (hydrolysed) by nonspecific esterases to yield the fluorescent product fluorescein and two acetates. Accumulations of fluorescein are the result of intracellular esterase activity and thus indicate metabolic activity and therefore cell viability. ROS were assayed with carboxy-H2DFFDA, a cell-permeable fluorescent indicator that is non-fluorescent until oxidation by ROS occurs within the cell. H2DFFDA detects intracellular ROS species, and despite its lack of specificity, it has been proven very useful and reliable for assessing the overall oxidative stress being oxidized by any possible radical with oxidative activity [44]. ROS detection was performed after 15 µL of a 2 mM working stock of carboxy-H2DFFDA were added to 1 mL samples. Samples were incubated at 16 °C in darkness for 120 min under gentle shaking. Fluorescence was measured using an Accuri™ C6 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, USA). Counts were triggered using forward scatter (FSC) signals.

Substrate Dependent Kinetics of Inorganic C Fixation

A 14C-based method was used to estimate the substrate dependent kinetics of inorganic C fixation based on Tortell et al. [45]. These measurements were conducted through short-term incubations of 10 min over a range of external C concentrations in buffered seawater (20 mM Bicine, pH 8.0). Prior to the beginning of the experiments, inorganic C was removed from the assay buffer by purging 20 mL aliquots with CO2-free air for at least 3 h [46, 47]. 1.5 mL of phytoplankton aliquots in C-free buffer were dispensed into polypropylene microcentrifuge tubes and placed in a custom-made, temperature-controlled glass chamber (16 °C). The incubation tubes were illuminated from the side with 600 µmol photons m−2 s−1 provided by a fluorescent tube of daylight type Osram Sylvania standard truelight 18 W. To initiate measurements, various amounts of 6 mM H12CO3− (0.108 g HCO3− + 20 mL of CO2-free water + 30 µL NaOH 4 N) and H14CO3− (DHI, Denmark) (specific activity vial: 2.18 × 109 Bq · mmol−1; final specific activity: 0.055 × 109 Bq · mmol−1; 2 mL stock of HCO3− cold + 0.2 mL ampoule of 14C (total 2.2 mL)) were added to each tube. The 14C/12C additions were adjusted to yield a final concentration of total inorganic carbon ranging from ≈ 50 to 4,000 µM, with a final specific activity of 0.055 × 109 Bq mmol−1. After 10 min of incubation, 500 µL of each tube were rapidly transferred into 500 µL of 6 N HCl in 20 mL scintillation vials and vortexed. Vials were then placed on a shaker table to degas evolved 14CO2 for at least 12 h. After this time, 14C activity of the samples was measured after adding 10 mL of scintillation cocktail (Ultima Gold, Perkin Elmer, USA) using a liquid scintillation counter (Packard Tri Carb Liquid Scintillation Analyser, Model 1900 A, Perkin Elmer, USA) with automatic quench correction. Background activity levels in cell-free blanks were subtracted from all samples.

Kinetic parameters Vmax and Km were derived from the 14C data using nonlinear, least-squares regression of the hyperbolic Michaelis–Menten equation (Eq. 2):

| 2 |

where V is the rate of C fixation at any given external C concentrations (S), and Vmax is the maximal rate of C fixation [note that maximal C fixation rates obtained from this analysis are not directly comparable to steady-state C uptake rates measured in traditional (12–24 h) 14C-incubation experiments. The 10-min rates reflect the total cellular capacity for C fixation, while longer-term rates include a significant contribution of respiration and organic C release, and cell death]. Km was the concentration of C for half Vmax. Carbon fixation rates were normalized by previously obtained cell counts.

Elemental Composition

Total particulate carbon (TPC) was measured using a C:H:N elemental analyser (Perkin-Elmer 2400 CHN). Twenty-five millilitres of each culture were gently filtered through pre-combusted (4.5 h, 500 °C) GF/F filters (Whatman) and dried at 60 °C for 24 h. For the determination of POC, the protocol was the same as for TPC, except those filters were fumed with saturated HCl overnight before analysis. PIC was assessed as the difference between TPC and POC.

Stable δ13C Isotopic Determination

The value of δ13C is used as a proxy of HCO3− versus CO2 only used by an aquatic primary producer, the former requiring a carbon concentrating mechanism (CCM). Typically, a value below (more negative than) − 30‰ indicates an inactive or absent CCM. However, this reference value should be taken cautiously, since it can be influenced by the specific δ13C value of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase-oxygenase (RuBisCO) for CO2 fixation in a given species. The abundance of 13C relative to 12C in E. huxleyi samples was determined by mass spectrometry using a DELTA V Advantage (Thermo Electron Corporation, USA) Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer (IRMS) connected to a Flash EA 1112 CNH analyser. δ13C isotopic discrimination in the microalgae samples (δ13Csample) was expressed in the unit notation as deviations from the 13C/12C ratio of the Pee-Dee Belemnite CaCO3 (PDB, which is the same as VPDB) calculated according to (Eq. 3):

| 3 |

To determine the isotopic composition of dissolved inorganic carbon (δ13CDIC), 25 mL from each cylinder were filtered (Whatman GF/F). Measurements of δ13CDIC were performed with the same IRMS mentioned above connected to a GasBench II (Thermo Electron Corporation) system. The δ13Csample was corrected by δ13CDIC values from the medium, previously tested in a TOC-L analyser.

pH Drift

A pH drift experiment was carried out to determine if E. huxleyi can use HCO3− as a source of inorganic carbon. The ability of algae to raise the pH of the medium to more than 9.0 is considered as evidence of their ability to use HCO3−. Samples were placed in 100 mL glass bottles filled (without leaving a head space) with 0.2 µL filtered seawater enriched with f/2 nutrients, and tightly sealed to avoid gas exchange. To obtain a complete homogenization of the medium, a magnetic bar was placed into each bottle and continuous stirring was provided by a magnetic stirrer. Samples were exposed to continuous illumination provided by white fluorescent tubes at saturating light. The pH was recorded by introducing a glass electrode through the lid of the glass bottle each 4–5 h until a stable reading was reached. Measurements were carried out until no further increase of the pH was detected.

Morphometric and Data Analysis of Coccoliths and Coccospheres

Size and morphological features of the cells were analysed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Samples of the different treatments (250 µL, 500 µL, and 1000 µL, depending on cell abundance) were filtered using Millipore Isopore™ hydrophilic polycarbonate membranes (RTTO01300) of 13 mm in diameter, and a pore size of 0.8 µm, using a vacuum pump under low pressure (< 200 mbar). Filters were rinsed with buffered distilled water to remove salt and then air dried overnight, mounted on aluminium SEM stubs, sputter coated with gold/palladium, and subsequently examined using a Zeiss EVO MA10 SEM.

The coccoliths were visually classified according to four morphological categories to estimate their degree of malformation [48, 49] (Fig. 6). The first category corresponds to normal coccoliths with all segments connected and forming an oval ring. The next three categories represent stages with increasing malformation signs characterized by a reduced symmetry, an altered shape of some of the elements, and reduced distal shield elements. Specifically, the second category corresponds to slightly malformed coccoliths, with less than 5 T-segments not well connected to others. The third category corresponds to malformed coccoliths where more than 5 T-segments are disconnected or not entirely formed. The fourth corresponds to fragmented coccoliths, in which parts of the coccoliths are missing. Category 4 is considered as severe malformation. The damaged coccoliths were measured only if their “reference points” could be unequivocally determined. Approximately 30 coccospheres and 30 coccoliths of each treatment were analysed (i.e., HC-LP, LC-HP, and LC-LP). The mean values of each parameter were considered constant when there were more than 20 coccospheres and coccoliths measurable per sample [50]. As for the coccoliths, all the morphometric measurements were performed on the distal shield of flat lying E. huxleyi placoliths (see Supplementary Fig. S2). Measurements included the length of the distal shield (DL), the width of the distal shield (DW), the length of the central area (CAL), and the width of the central area (CAW). CAL and CAW could not be determined in cases where the coccolith was lying upside-down on the filter. In addition, the number of segments or elements that form the distal shield were recorded. The surface area of the distal shield (DSA) was estimated with the values of DL and DW [51] (Eq. 4):

| 4 |

Fig. 6.

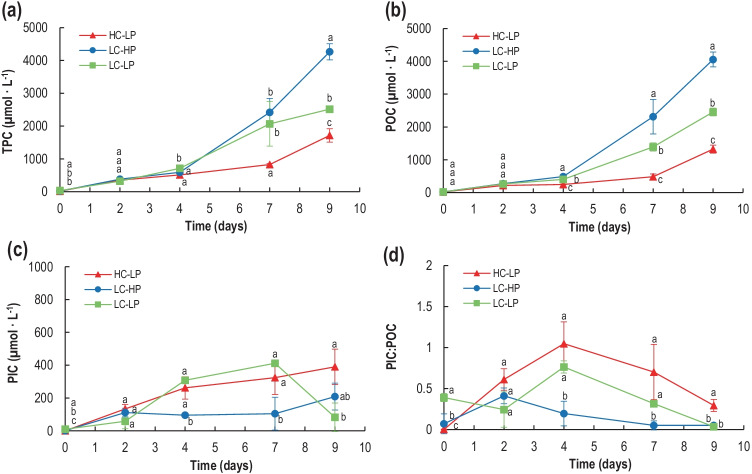

Temporal development of total particulate carbon, TPC (a), particulate organic carbon, POC (b), and particulate inorganic carbon, PIC (c) concentrations (µmol L−1) and molar inorganic C (PIC): organic C ratio (POC) (d) in E. huxleyi cultures under HC-LP (1000–1200 µatm and pH 7.6–7.8), LC-HP (380–390 µatm and pH 8.2), and LC-LP (380–390 µatm and pH 7.6–7.8). Values are mean ± SD (n = 3). Significant differences between treatments are indicated by different letters for any given time (p < 0.05)

The outer shield length (OSL) was calculated assuming an elliptical shape of coccolith, such as (Eq. 5):

| 5 |

In addition, the calculation of the surface area of central shield (CSA) is proposed taking the values of CAL and CAW, such as (Eq. 6):

| 6 |

The width of the tube (protococcolith ring) (TW) varies between coccoliths of E. huxleyi, from slightly calcified coccoliths in which the central area is wide and the tube is narrow to very calcified coccoliths in which the central area is almost closed. To obtain a size independent parameter to measure this degree of calcification variation, we used relative tube width (TWrelative) (Eq. 7). This parameter is used here as a calcification index. This ratio is dimensionless and should be size-independent.

| 7 |

Coccoliths mass (m) has also been used as an indicator of the impact of OA on coccolithophores [52, 53] as (Eq. 8):

| 8 |

where ks is a shape dependant constant, Ks = 0.07 TWrelative, and DL distal shield length.

The roundness of the distal shield (DR) (Eq. 9) and the roundness of the central area (CAR) (Eq. 10) were calculated, from the ratio of their width and length measurements [54] as:

| 9 |

| 10 |

As for the coccospheres, two measurements were made, one of them corresponding to the greater length L and another to the shorter length W.

Measurements were taken from SEM micrographs which were processed and analysed using the software Fiji-ImageJ 1.49v software [55, 56] (National Institute of Health, USA).

Statistical Analyses

Statistical significance of treatments was analysed by performing split-plot ANOVAs (SPANOVAs, or mixed-model ANOVAs) followed by post hoc Sidak or Tukey and Bonferroni tests, respectively (considering p < 0.05 as significant). When appropriate, data were specifically tested for significant differences (p < 0.05) induced by the treatments by using 1-way ANOVAs and/or Student’s t-tests, as well as Pearson’s product-moment correlations. All analyses were performed using the general linear model (GLM) procedure. Data were previously checked for normality (by Shapiro-Wilks’ test), homoscedasticity (by Cochran’s and Levene’s tests), and sphericity (by Mauchly’s and/or Bartlett’s tests). Variables met all criteria mentioned above. Statistical analyses were performed using the software SPSS v.22 (IBM statistics) and R-studio.

Results

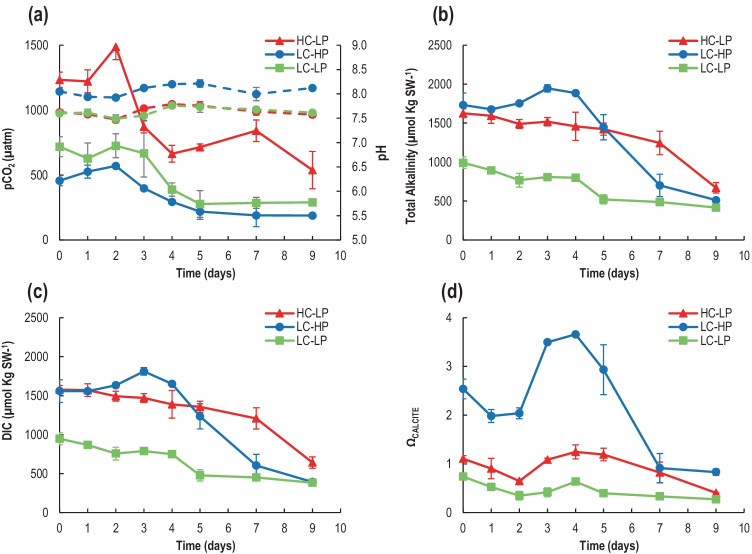

Carbonate System

The carbonate system data are shown in Table 1. The initial pCO2 levels were 1233 ± 59 µatm in the “high-CO2” treatment (HC-LP) and 456 ± 39 µatm and 718 ± 77 µatm in the control (LC-HP) and “low-pH” (LC-LP) treatments, respectively. The biological activity promoted a gradual change in the carbonate chemistry conditions from the start to the end of the experiment. Accordingly, pCO2 decreased between day 1 (d1) and day 4 (d4) in all treatments, reaching a minimum level of ~ 300 µatm in the LC-LP and 200 µatm in LC-HP, as a consequence of the gradual decline in total alkalinity derived from calcification and cell division. Values for pCO2 did not show significant differences between the two low CO2 treatments (LC-HP and LC-LP) for the rest of the experiment (see Supplementary Table S4).

Table 1.

Corrected δ13C isotopic discrimination (δ13Cmicroalgae) and pH compensation point for E. huxleyi under the different experimental conditions on day 9; HC-LP (pCO2: 1000–1200 µatm; pH: 7.6–7.8), LC-HP (pCO2: 380–390 µatm; pH: 8.2), and LC-LP (pCO2: 380–390 µatm; pH: 7.6–7.8). Values are mean ± SD. Significant differences between treatments are indicated by different letters (p < 0.05)

| Treatment | δ13Cmicroalgae (‰) | pH compensation point |

|---|---|---|

| HC-LP | − 28.37 ± 1.10a | 8.02 ± 0.03a |

| LC-HP | − 16.07 ± 0.27b | 9.70 ± 0.07b |

| LC-LP | − 18.17 ± 1.15b | 9.17 ± 0.03c |

Ωcalcite was significantly higher in the control than in the two other treatments (p < 0.05, Supp. Table S4), reaching a maximum value of 3.66 ± 0.04 at d4, in contrast to 1.25 ± 0.14 and 0.63 ± 0.05 in the high-CO2 and the low-pH treatments, respectively. In agreement with the two acidification methods, TA and DIC did not present significant differences between the control and the high-CO2 treatments at d0, but were higher than in the low-pH treatment (Table S4). TA and DIC values gradually decreased between d0 and d9 in all treatments, to finally drop to the minimum values by the end of the culture period. The concentration of HCO3− showed a similar pattern to TA/DIC when acidification was produced by pCO2 and not by HCl, being similar at both pH 8.2 and 7.6–7.8 until day 5 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Measured pH (dotted line) (a) and total alkalinity (b), and calculated pCO2 (solid line) (a), dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) (c), and calcite saturation estate (Ωcalcite) (d), in the different treatments: HC-LP (pCO2: 1000–1200 µatm; pH: 7.6–7.8), LC-HP (pCO2: 380–390 µatm; pH: 8.2), and LC-LP (pCO2: 380–390 µatm; pH: 7.6–7.8). Values are mean ± SD (n = 3). Significant differences between treatments are indicated by different letters for any given time (p < 0.05)

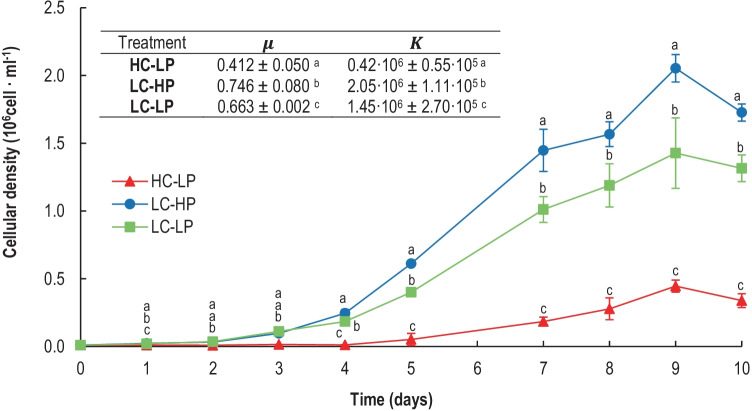

Cell Density and Growth Rates

All cultures reached the highest densities after d9 (Fig. 2). The maximal cell densities of the cultures (K) ranged between 0.24 × 106 cells mL−1 (in HC-LP, CO2-enriched cultures) and 2.05 × 106 cells mL−1 (in LC-HP, control conditions). The intrinsic growth rate (µ) was lower in HC-LP (0.412 d−1) than in LC-HP (0.746 d−1) (p < 0.05, Table S4). Both K and µ were mostly affected by high pCO2 (HC-LP); K was reduced by 80% and µ by 45% with respect to control conditions (LC-HP). When pH was decreased by acidification with HCl (LC-LP), the reductions of K and µ were only 30% and 11%, respectively, with respect to the control.

Fig. 2.

Cellular abundance (106 cell mL−1), net growth rates (µ, d−1), and loading capacity of the culture (K, 106 cell mL−1) of E. huxleyi cultures calculated with the logistic model of growth under HC-LP (1000–1200 µatm and pH 7.6–7.8), LC-HP (380–390 µatm and pH 8.1), and LC-LP (380–390 µatm and pH 7.6–7.8). Values are mean ± SD (n = 3). Significant differences between treatments are indicated by different letters for any given time (p < 0.05)

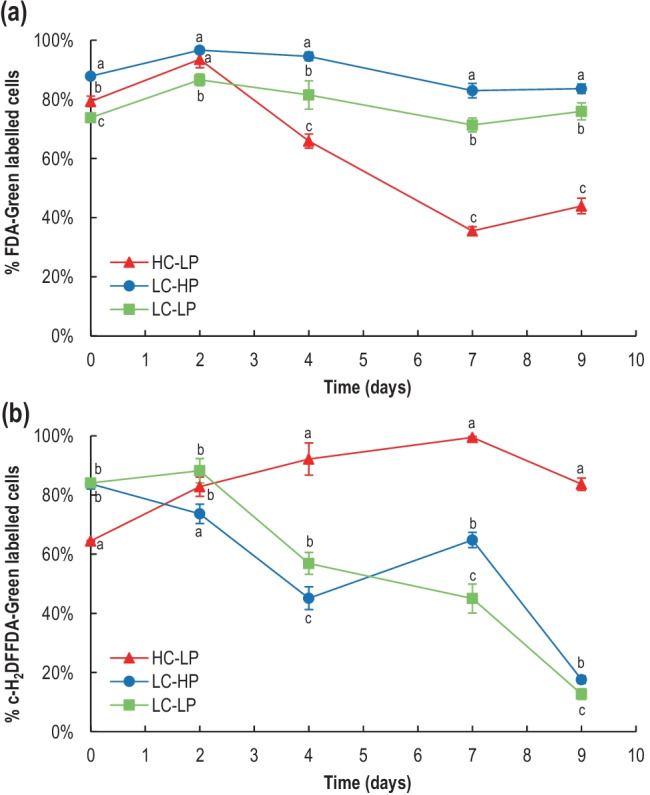

Cell Viability and Oxidative Stress

Cell viability showed significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05, Table S4; Fig. 3a). In the control conditions (LC-HP), cell viability was ~ 90% along the entire experiment. Acidification with HCl (LC-LP) reduced cell viability by an extra 10% compared to the control, i.e., 80% were still viable. However, in CO2-enriched cultures (HC-LP), the cell viability sharply declined from 48 h onwards, and only 35% of the cells remained alive by the end of the experiments. General oxidative stress was high in all treatments at initial times (Fig. 3b), most likely indicating a temporary stress by the dilution effect according to ROS accumulation. Highest ROS content occurred in HC-LP (~ 90% green fluorescence labelled cells) from d4 to d9. However, in LC-HP and LC-LP, only ~ 10% of the cells showed ROS green fluorescence by d9, and thus in LC, only a small proportion of the cells were stressed.

Fig. 3.

Variation of (a) cell viability measured as FDA-green fluorescence labelled E. huxleyi cells, and (b) reactive oxygen species (ROS) measured as c-H2DFFDA-green fluorescence labelled E. huxleyi cells in HC-LP (1000–1200 µatm and pH 7.6–7.8), LC-HP (380–390 µatm and pH 8.1), and LC-LP (380–390 µatm and pH 7.6–7.8). Values are mean ± SD (n = 3). Significant differences between treatments are indicated by different letters for any given time (p < 0.05)

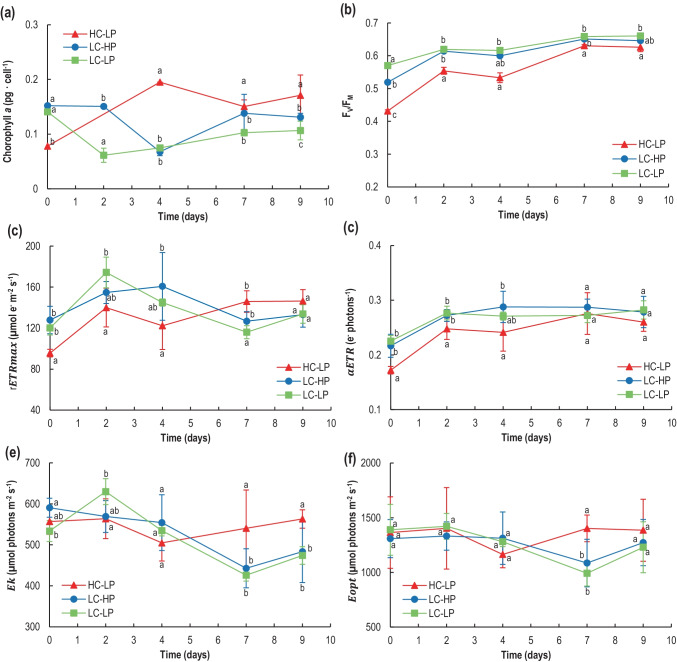

Chl a Concentration and In Vivo PAM Fluorescence

Chlorophyll a per cell showed an initial decrease in all treatments up to d2–d4 (probably due to increased radiation reaching the cells after dilution at time d3), then it sharply increased, especially in high CO2 with respect to control treatment (Fig. 4a). Chl a cellular concentration was steady from d7 onwards, and it was similar to initial values in both LC treatments; however, in HC, it remained significantly higher. Initial FV/Fm values (Fig. 4b) ranged from 0.43 (high CO2) to 0.57 (low pH), and in all cases increased from the beginning to the end of the experiment, reflecting a temporary dilution stress and subsequent recovery. Final values around 0.63–0.66 were found in all treatments. However, FV/Fm was always significantly lower in high-CO2 cultures (p = 0.017, Sidak), suggesting not only that the photosynthetic performance was affected when aerated with high-CO2-enriched air, but also that acclimation to those conditions was possible, but slow. Both control and low-pH treatments exhibited a similar trend, without significant differences between treatments over time. The results of the low-pH compared to high-CO2 treatments indicate that the responses of the photosynthetic activity and the state of the photosystem II depend on the method used for acidification, with a negative effect by high CO2.

Fig. 4.

Photosynthetic parameters of rapid light curves in E. huxleyi cultures under conditions of HC-LP (1000–1200 µatm and pH 7.6–7.8), LC-HP (380–390 µatm and pH 8.2), and LC-LP (380–390 µatm and pH 7.6–7.8). Chlorophyll a (pg cell−1) (a), optimal quantum yield of Chl a associated to photosystem II (FV/Fm) (b), relative maximum ETR (rETRmax) (c), photosynthetic efficiency (αETR) (d), saturation irradiance (Ek) (e), and the highest irradiance just before photoinhibition occurs (Eopt) (f). Values are mean ± SD (n = 3). Significant differences between treatments are indicated by different letters for any given time (p < 0.05)

RLCs investigating photosynthetic performance indicated a similar maximum electron transport rate (rETRmax) in all conditions for E. huxleyi cells (d9), albeit it was higher in both control and low-pH treatments during the first 4 days (Fig. 4c). The photosynthetic efficiency (αETR) increased in all treatments as cultures developed, and at d9, there were no significant differences between treatments. The irradiance at which photosynthetic linear electron transport was saturated (Ek) declined during cultivation in both control and low-pH treatments as cell density raised, but it remained high in high CO2 (Fig. 4e). This is in agreement with the lower cell density in this latter treatment (Fig. 2), reflecting the higher irradiance levels inside the cultures. Treatments had only marginal effects on the irradiance at which chronic photoinhibition is established (typically between 1200 and 1500 µmol quanta m−2 s−1), according to the Eopt values (Fig. 4f).

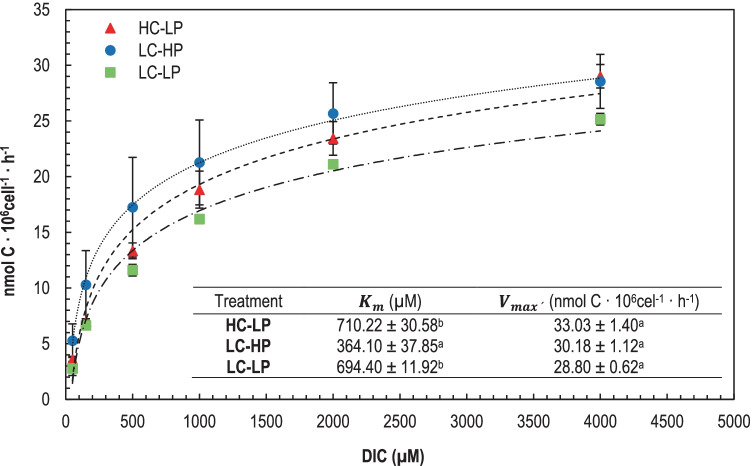

Carbon Fixation Performance

A typical Michaelis–Menten saturation kinetic resulted from measuring C fixation at increasing DIC concentrations in cells from all three treatments (Fig. 5). Vmax was not significantly different between the treatments. Values varied between 28.80 ± 0.62 and 33 ± 1.40 nmol C 106 cell−1 h−1, revealing similar RuBisCO fixation ability for all culture conditions (p < 0.05, Table S5). However, both acidification conditions (HC-LP and LC-LP) produced a significant decrease in DIC affinity according to nearly double KM values with respect to the control (LC-HP). This result indicates that carbon uptake was negatively affected by low pH rather than high CO2.

Fig. 5.

Carbon fixation rate showing KM (µM) and Vmax (nmol C · 106 cell−1 · h−1) for E. huxleyi in d4 under HC-LP (1000–1200 µatm and pH 7.6–7.8), LC-HP (380–390 µatm and pH 8.1), and LC-LP (380–390 µatm and pH 7.6–7.8) treatments. DIC concentrations in the assay medium were 50, 150, 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 µM. The kinetic parameters were calculated by fitting to Michaelis–Menten kinetics. Values are mean ± SD (n = 3). Significant differences between treatments are indicated by different letters (p < 0.05)

pH Drift and Stable δ13C Isotopic Determination

The pH compensation point is the final pH obtained in the pH drift experiment. This is the maximal pH value that the E. huxleyi cultures were able to reach while performing photosynthesis, as measured at the end of the culture period (day 9). It is commonly assumed that pH values greater than 9.0 pinpoint the ability of the cells to use HCO3−, in addition to CO2, as a source of inorganic carbon for photosynthesis. This capacity was observed under control conditions (final pH 9.7). However, both low-pH treatments decreased the ability of E. huxleyi to use HCO3−, specifically when acidification was caused by high pCO2 aeration (HC-LP; Table 1). The isotopic discrimination values (δ13Cmicroalgae) in E. huxleyi (Table 1) were significantly more negative in high-CO2 cultures, decreasing from − 16.1‰ for LC-HP (control) to − 28.4‰ for HC-LP (p < 0.05, Table S5). These data are close to the theoretical limit of − 30‰, indicative of downregulation of CCMs; however, this interpretation must be taken with caution as it is determined by the specific discrimination of RuBisCO. Boller et al. [57] gave an unexpected value for RuBisCO discrimination of − 11‰. Wilkes and Pearson [58] suggest a mechanism by which the in vitro carbon isotope discrimination of RuBisCO in Boller et al. [57] can be reconciled with in vivo carbon isotope discrimination of E. huxleyi. Nonetheless, when acidification was produced by HCl addition, δ13Cmicroalgae decreased only slightly, to − 18.2 ‰, evidencing the requirement for high concentrations of CO2 to deactivate CCMs in E. huxleyi.

Calcification and Morphometry

TPC as well as POC in the cultures rapidly increased after cell inoculation in all treatments (Fig. 6a, b). Up to day 4, there were no significant differences between treatments (Table S4). However, from d4 onwards, significant differences were found. The highest concentrations of both TPC and POC (µmol L−1) occurred in control cultures (LC-HP), while they reached just one-third of the control concentration at high CO2. The low-pH treatment showed an intermediate trend. These data partly reflected the growth of E. huxleyi in the three conditions tested in this work. A different scenario was found for PIC. In the control cultures, PIC increased during the first 2 days, remaining steady to the end of the experiment (Fig. 6c). PIC highest accumulation occurred at d9 in high CO2 and at d7 in low pH. It returned to initial values at the end of the experiment. Ratio of PIC:POC transiently increased in all treatments during d2 to d4, dropping to initial values after at d9. PIC:POC was always higher in high CO2, reflecting the accumulation of PIC in the medium, concomitant with a lower POC. In both control and low-pH conditions, PIC represented a very small fraction of the total particulate carbon in the cultures.

POC and PIC per cell sharply increased in all treatments during the first 4 days, coincident with the lag phase of growth. This increase was more pronounced in high-CO2 conditions (HC-LP) (Table 2). POC further decayed by 50–75% in high CO2 as compared to the other two treatments. The similar trend was found for cell PIC content but, at the end of the experimental period, PIC was 7- to 15-fold higher at high-CO2 cultures. These data indicate that on a per cell basis, E. huxleyi accumulated more POC and PIC in high carbon compared to low carbon conditions.

Table 2.

Particulate organic (POC) and inorganic (PIC) carbon cell quotas for E. huxleyi (pg cell−1) in HC-LP (1000–1200 µatm and pH 7.6–7.8), LC-HP (380–390 µatm and pH 8.1), and LC-LP (380–390 µatm and pH 7.6–7.8). Values are mean ± SD (n = 3). Significant differences between treatments are indicated by different letters for any given time (p < 0.05)

| Day | POC (pg cell−1) | PIC (pg cell−1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC-LP | LC-HP | LC-LP | HC-LP | LC-HP | LC-LP | |

| 0 | 23.61 ± 2.83a | 25.82 ± 9.40a | 29.40 ± 0.91a | 0.12 ± 0.00a | 3.62 ± 0.00b | 11.47 ± 1.60c |

| 2 | 285.87 ± 23.91a | 97.76 ± 0.48b | 81.31 ± 11.42b | 174.17 ± 35.93a | 40.16 ± 9.47b | 27.31 ± 9.75b |

| 4 | 241.51 ± 7.28a | 23.83 ± 0.23b | 26.45 ± 1.93b | 253.24 ± 66.24a | 4.66 ± 0.29b | 20.09 ± 0.70b |

| 7 | 31.36 ± 5.53a | 19.18 ± 4.37b | 16.50 ± 1.47b | 21.06 ± 6.68a | 0.86 ± 0.83b | 4.89 ± 0.00b |

| 9 | 35.68 ± 3.30a | 23.70 ± 1.32b | 20.65 ± 1.00b | 10.50 ± 2.90a | 1.49 ± 0.004b | 0.69 ± 0.73b |

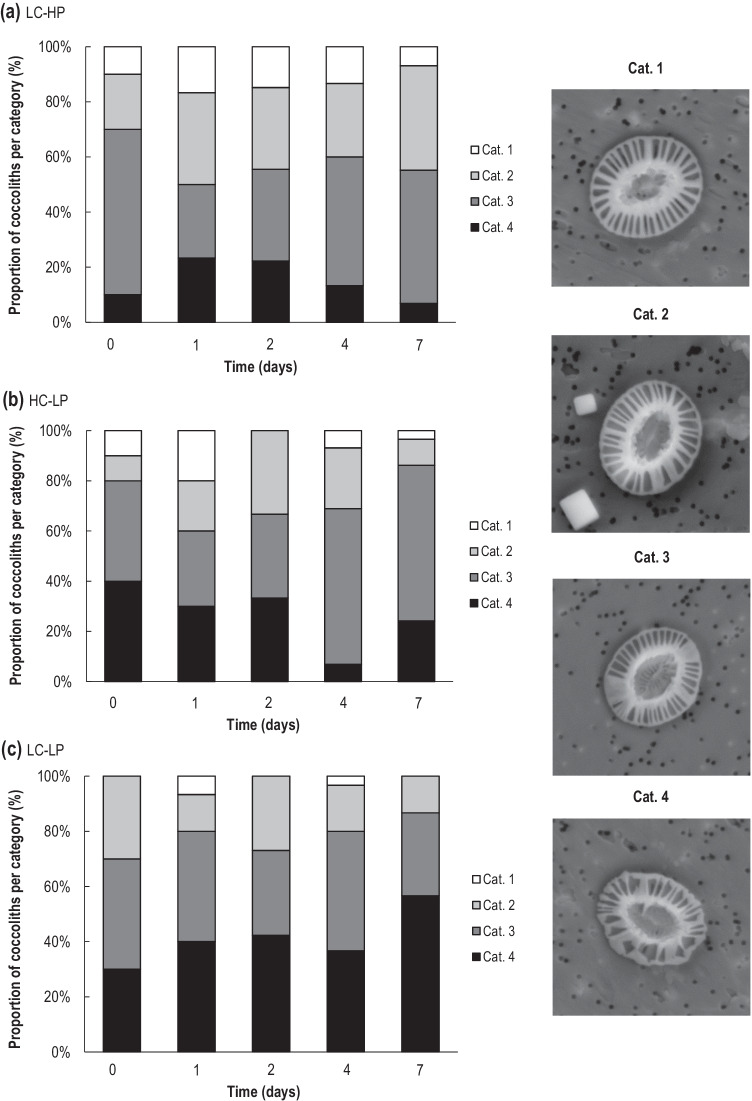

SEM images confirmed the presence of a single E. huxleyi morphotype in the cultures; coccospheres with heavily calcified elements and almost closed coccolith central area, corresponding to type A “overcalcified” (see Supplementary Fig. S1, and Supplementary Table S2) [59]. The morphological analysis revealed several degrees of coccolith malformation (Fig. 7) in the cultures throughout the experiment. The percentage of non-distorted coccoliths (Cat. 1) was higher in the high-CO2 and control treatments, with up to 20% and 16.67% respectively in d1, while only 6.67% of coccoliths showed no evidence of malformation in low pH at the same time. On the contrary, up to 56.67% (d7) of malformed coccoliths (Cat. 4) was observed in low pH, followed by 40% in d0 at high CO2. The highest percentage of 23.33% severely damaged coccoliths was found in d1, being lower in LC-HP. In general, the proportion of intact coccoliths decreased throughout the experiment in all treatments (Fig. 7). Similarly, the percentage of damaged coccoliths (Cat. 4) decreased over time in the control treatment while it increased in low pH. The proportion of severe malformation in coccoliths showed no significant relationship with carbonate chemistry variables. Detailed size morphology measurements of the coccoliths are shown in Supplementary Table S3.

Fig. 7.

Percentage of E. huxleyi coccoliths per category. We assigned Cat. 1 to normal intact coccoliths, and Cat. 4 to fragmented coccoliths in all different treatments: LC-HP (380–390 µatm and pH 8.2) (a), HC-LP (1000–1200 µatm and pH 7.6–7.8) (b), and LC-LP (380–390 µatm and pH 7.6–7.8)

Discussion

The results indicate that the strain of E. huxleyi used in this study responded differently to acidification depending on whether it was caused by high levels of dissolved CO2 or by HCl addition. Several studies have previously focused on the differential effects of the acidification methods on several species of calcifiers and a varied strain of E. huxleyi, i.e., by means of increasing pCO2 maintaining TA constant, or by manipulating pH with concomitant change on TA [29], and diverse response patterns were observed. It is now known that the different strains of E. huxleyi show phenotypic plasticity regarding their growth performance, light-responses, calcification, and virus susceptibility [14]. This phenomenon is most likely a consequence of genomic differences, transcriptomic [14], and metabolomic [15] responses to environmental conditions, and/or threats such as viral infections [60]. Moreover, methodological differences are also responsible for the variety of response patterns observed in growth and photosynthetic performance, as well as in calcification [24, 29]. One of the methodological controversies when differentiating CO2 and pH effects as acidification methods is the aeration of the cultures. Shi et al. [61] compared responses of growth, POC and PIC quotas, and primary production of one E. huxleyi strain (NZEH), in closed TA and open DIC manipulations. Even though the cells responded differently under the two manipulations, it is still unclear whether this was due to differences in the carbonate chemistry or to mechanical effects of gas bubbles during aeration (independently of TA and DIC levels). The latter only occurred in the open DIC manipulation treatment and affected cell sedimentation. This was not the case in our study, since aeration was the same for all treatments and, additionally, mixing was ensured by gentle stirring at the bottom of the culture cylinders, rendering optimal growth rates and calcification in control conditions. Thus, the differences observed must be due to bubbling mechanical effects as previously demonstrated in this species [29].

Factors that affect growth rate and FV/Fm are likely to also affect the acclimation rate. For instance, in experiments that were carried out at a temperature significantly colder (8 °C) than the temperature used in our study (16 °C), about 10 days were needed for cells to be completely acclimated to the high-CO2 levels [62, 63]. However, studies at higher temperatures (22 °C) have shown that acclimation is normally reached 3–4 days after the start of the CO2 aeration [64]. Therefore, 72 h are well within the range to allow for full acclimation to the new pCO2 according to the temperatures used in our study.

Growth rate is a comprehensive variable integrating all physiological processes in marine phytoplankton, and its different responses to increased pCO2 have been reported for different strains of E. huxleyi, with positive, negative, or even no significant changes (e.g., [29] and references therein).To our knowledge, a notably stronger detrimental effect of acidification by using CO2 enrichment (HC-LP treatment in our experiment) than by increasing [H+] alone (LC-LP treatment) has not been previously reported. Yet, growth and organic carbon production rates in E. huxleyi seemed to be adversely affected by the associated decrease in pH directly related to high-CO2 levels [30, 51]. A reduction of 10 to 35% in growth rates at high CO2 have been also described for this species [13, 29], and the latter study [29] reports low sensitivity of growth to modifications of pH alone.

Importantly, a comparable effect with the present results has been reported for C. leptoporus [65] where adverse effects were caused by CO2 instead of pH. We discuss here the differences between the effects of the HC-LP and the LC-LP treatments despite the steady pH values, concluding that the differences lie on both DIC and CO2. Therefore, the different responses of the cells could be caused by either DIC or CO2, or indeed by both, most likely through increasing the CO2 concentration in the diffusive boundary layer of the cell [65]. Fukuda et al. [66] used experimental pH and CO2 treatment levels similar to the one used in the present study. The strain they used was originally from the Pacific Ocean (NIES 837) and their results showed an opposite trait for growth than ours, i.e., growth increased at high CO2, and decreased at lower pH (without CO2 enrichment). They did not bubble continuously with CO2-enriched air, which suggest that those results are to be taken carefully.

Lorenzo et al. [21] used the same strain as in the present study but cultured cells at 400 and 800 µatm CO2 and found no significant effect of increased CO2 on the growth rate. Two reasons account for the apparent contradiction with the results shown here: (1) they used the exponential model of growth to calculate the growth rate instead of the logistic model, which resulted in an underestimation; and (2) their highest CO2 concentration was notably lower than the one used in the present work (1200 µatm). Hoppe et al. [29] also reported invariable growth rates up to 800 µatm, declining significantly beyond this value (highest CO2 concentration tested 1200 µatm). Similarly, Bach et al. [30] did not find significant differences in a smaller range up to 600 µatm. This supports the idea that detrimental effects of CO2 on growth rates occur at CO2 levels above 800 ppm. Nevertheless, other reports have shown negative effects of CO2 on growth rate at 600 ppm [13]. Since it is expected that by the end of this century the level of atmospheric CO2 will be over 900 ppm, E. huxleyi is predicted to be negatively affected in the near future.

Growth rates at high-CO2 and control conditions in this experiment were very similar to those found by Segovia et al. [20] under similar treatments (but using around 1000 µatm as high-CO2 level) in a mesocosm experiment in the Norwegian coast with a natural population. This suggests that both the natural population growing in those mesocosms and the strain used here had similar CO2 sensitivity and growth performance. These authors also showed, as here, a strong restriction of the maximum cell density at high CO2. The presence of high levels of CO2 did not only prevent cell division but also promoted the unviability of already formed cells [23]. It also affected the cellular level of many metabolites (175 out of 333 metabolites identified, [15]). All aminoacids (except glycine) and all detected TCA cycle substrates decreased at high CO2 relative to control conditions. Our results also indicate a metabolic misbalance (i.e., changes that affected the allocation of carbon and cellular energy efficiency) induced by high CO2, but not by lowering pH alone. Decreased cell viability promoted by high-CO2 levels was also reported for the above-mentioned Norwegian natural population mesocosm experiment [23]. It is known that elevated CO2 can impair signal transduction as well as ion-transport and catabolic processes [31]; yet, to our knowledge, this is the first study to directly point to CO2, and not acidification, as the cause of such impediments. A possible explanation is the permeation of CO2 to the intracellular space and its spontaneous conversion to HCO3− and H+, the latter deterring the processes mentioned above. Indeed, Langer and Bode [65] suggested that intracellular acidification through increased CO2 might be due to the diffusive boundary mechanism. Blanco-Almeijeiras et al. [67] demonstrated that the plasma membrane of E. huxleyi was permeable to CO2 but nearly impermeable to HCO3− under a high-CO2 environment, supporting the variation in carbon isotopic fractionation of photosynthetically produced organic matter assuming solely diffusive acquisition of CO2. In contrast, Suffrian et al. [68] are not able to detect a CO2 permeability high enough to change intracellular pH.

The onset of the cultures seemed to have imposed some sort of stress on the cells, probably due to increased irradiance after dilution of the stock culture, according to their relatively high signal for ROS accumulation and low FV/Fm. While cells under normal CO2 conditions were able to detoxify the high ROS as the cultures progressed, cells under high-CO2 conditions remained with high levels of stress. Genes encoding for ROS scavenging antioxidants, enzymes the synthesis of vitamin B6 mediating photo-oxidative stress in plants, and many light-harvesting complex (LHC) proteins have also been found in the core genome of E. huxleyi [14] and, more interestingly, they have been reported to orchestrate the response to stress in the coccolithophore under high pCO2 [23]. At least, some of these processes seemed to be also hindered by high-CO2 conditions, but not by low pH.

CO2-dependent changes in photosynthesis are highly variable and seem to differ between strains. Lorenzo et al. [21] found no differences in ETRmax between 400 and 800 ppm CO2 using the same strain. Also, Segovia et al. [23] found very discrete changes in fluorescence-derived photosynthetic parameters in a natural E. huxleyi population from Norway. Fukuda et al. [66], using a Pacific strain, reported no difference in FV/Fm and effective quantum yield (inversely related to ETR), either under acidification alone or with extra pCO2. It is common that CO2 uncouples photosynthetic C production from growth [33]. Growth restriction without effect on photosynthesis usually leads to organic C accumulation in the cell [33]. In this study, POC per cell was highest in HC cultures, particularly in the first half of the culture period, when most of the cells were still viable. Yet, cells were considerably smaller when a decrease in cell viability occurred over time. This evidences that the fate of C can vary depending on the growth phase of the culture, even when the photosynthetic capacity remains constant, as discussed below.

In other phytoplankton species, high-CO2 levels enhanced growth and photosynthesis protecting against photoinhibition [69]. In this sense, increased CO2 would have a positive role in photoprotection [69]. However, E. huxleyi presents a remarkable capacity to withstand photoinhibition even in normal CO2 conditions [12]. The coccolithophore’s core genome encodes a variety of photoreceptors, and related proteins that function in the assembly and repair of photosystem II, such as D1-specific proteases and FtsH enzymes, as well as proteins that have a role in non-photochemical quenching (NPQ) or synthesis of NPQ compounds [14]. The complex repertoire of such photoprotectors facilitates tolerance to high light minimizing ROS accumulation and preventing oxidative damage, so that, presumably, increased CO2 would not pose a positive selection pressure on E. huxleyi populations at the photochemistry level.

Carbon uptake by E. huxleyi is influenced by the pH of the assay medium and by the resulting carbonate chemistry, rather than by the pCO2 condition during acclimation [33]. However, since our 14C-based method for the determination of C uptake kinetics was performed in a buffered medium (pH 8) in all cases, the differences can only be attributed to culture conditions and not to the assay conditions. The decrease in Ci affinity (higher KM) can be ascribed to partial deactivation of some of the components of the CCMs. Like most phytoplankton, E. huxleyi operates a CCM which accumulates CO2 in the vicinity of RuBisCO [70, 71]. The deactivation of the CCM is corroborated by lower (more negative) values of δ13Cmicroalgae and lower pH compensation points in the high-CO2 cultures but not in low-pH ones. Hence, the decreased affinity, at least in the latter, might be due to a weaker H+ gradient across the plasma membrane that could provoke a CO2 leakage from within the cell. Leakage of CO2 was higher when the CO2 gradient between the cytosol and the external medium increased [72]. In our experiment, this CO2 gradient was most likely larger at low external pCO2, and the loss of CO2 via leakage (and therefore the reduction in carbon fixation affinity) could have been more pronounced under these conditions (LC cultures). The leakage of CO2 strongly increased at pCO2 levels below 200 µatm in several other species [73, 74]. However, its effect on C fixation can be reverted by an active HCO3− transporter. E. huxleyi relies mainly on CO2 diffusive entry at pH < 8.1 [33] (as in LC-LP, Table 1), but can use a HCO3− transporter at higher pH (as in the control). By using the isotope disequilibrium assay [70], it was demonstrated that the E. huxleyi strain studied in a natural phytoplankton community from coastal waters of Norway did use HCO3− transporters actively, so that the main Ci source was HCO3− [71]. This could account for the difference in Ci affinity and CCM activation level of the three treatments used in this work.

Since the response of ocean chemistry to increasing pCO2 involves the decrease in calcium carbonate saturation that might affect biological calcification, many acidification experiments commonly focus on calcification by coccolithophores. Such experiments have generally shown a negligible to relatively large decrease in calcification at high pCO2, but there are also reports on higher calcification at high CO2/low pH, depending on the species, strains, and methodology used [75]. PIC and POC content per cell indicated an over-accumulation with respect to the control (LC-HP) during the exponential growth phase, which was much more obvious at high CO2. An increase in the cellular POC quotas at higher CO2/lower pH is more commonly reported than the increase in PIC quotas. Usually, calcification is defective under corrosive conditions, and rapid coccolith dissolution has been observed to start with Ωcalcite values below 0.4 [30]. We did not obtain Ωcalcite values below 0.4 at high CO2, but we did at low pH. Malformed coccospheres were more abundant under both acidified conditions, but particularly in the low-pH treatment. Thus, increased CO2 did not restrict calcification; on the contrary, both POC and PIC accumulation in high-CO2-grown cells seems to have served as a fate of Ci being taken up and not used for growth. The LC-LP treatment was characterized by a substantial dissolution. Data supports this inference because while the cultures were still growing, the PIC quota (both cell and volume normalized) was decreasing. In parallel, the DIC and TA decrease leveled off. Taken together, these results strongly support PIC dissolution. SEM analyses showing an increased level of Cat. 4 “malformations” in LC-LP (Fig. 7) reinforce the former affirmation on PIC dissolution. Cat. 4 morphology is possibly a malformation but could equally possibly be a dissolution-morphology. In E. huxleyi, malformation and dissolution can be very difficult to differentiate. It is not possible to assess PIC production in this treatment and that makes complex to interpret coccolith morphology because Cat. 4 coccoliths here are likely a mix of malformed and partially dissolved ones. PIC and POC cellular quotas in the present work varied notably during the different phases of the culture. This means that experiments in which samples are either taken at a specific time point or kept in semi-continuous exponential phase of growth do not describe completely the overall behaviour of an E. huxleyi bloom. In this sense, the high PIC and POC values observed perfectly correlated with the long lag phase of growth found under those conditions. Cells did not start to divide in HC-LP until approx. day 4, and we presume that accumulation of both PIC and POC was occurring. When active growth resumed, cell POC and PIC quotas dropped off to normal values. Thus, we think that this overcalcified type A strain might have had cell division arrested during that phase of the experiment while photosynthesis and calcification were active, hence accumulating cellular POC and PIC. Clearly, these are exceptional values that have never been reported before. We also demonstrate in this study that other relevant variables such as cell viability, ROS accumulation, and PIC:POC ratio depend on the phase of the bloom, as also previously reported in mesocosm experiments [23, 71].

As concluding remarks, the results obtained with the strain of E. huxleyi used here highlight the capacity of CO2 rather than acidification itself to generate metabolic stress and functional imbalance (meaning metabolic changes that affected the allocation of carbon and cellular energy efficiency). The metabolic and growth impairment caused by high CO2 exceeded the small effect on photochemistry, even though a considerable accumulation of ROS was recorded. The precise mechanism by which CO2 permeating the cell (and/or enhanced CO2 leakage) may interfere with the metabolism of E. huxleyi still remains to be elucidated. Accordingly, the levels of CO2 expected in the near future may compromise growth and cell viability (despite the small effect on calcification). CO2 perturbation experiments are major tools used to mimic future ocean scenarios and to study the response of relevant organisms contributing to the C cycle and the biological pump. Data supply for large-scale system models critically depend on ecophysiological studies of functional groups such as calcifying organisms. The diversity of the response depicted here reflects the difficulty to estimate the amount of anthropogenic CO2 taken up by globally important calcifying species such as E. huxleyi. The heterogeneous behaviour of this species indicates that a single strain is unlikely to represent the whole species. It is also worth noting that other environmental drivers (such as temperature and Fe availability) may be equally or more influential than CO2 and pH in regulating the physiological responses of E. huxleyi; hence, more multistressors experiments are needed to improve our understanding on how phytoplankton communities will develop in our future high-CO2 oceans.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff from the Microscopy Facility at the Institute of Medical Sciences, University of Aberdeen, UK. We thank the reviewers for their time, constructive criticisms, and insightful comments.

Author Contribution

VV: run the experiments, worked in the lab, analysed samples and data, wrote the paper.

PL: analysed samples and data, wrote the paper.

FG: designed the experiment, worked in the lab, discussed results, wrote the paper.

CJ: designed the experiment, worked in the lab, discussed results, wrote the paper.

CI: analysed samples.

KM: analysed samples.

EB: analysed samples.

MS: designed the experiment, worked in the lab, discussed results, wrote the paper.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. Funding for open access charge: Universidad de Málaga / CBUA This work was funded by FC14-RNM-27 research grant (FITOVIA) from the University of Málaga, Spain (Plan Propio) to CJ. VV was funded by a EUROPE ERASMUS + grant to carry out research short-stay at Marine Scotland Marine Laboratory in Aberdeen, UK, and by a grant from the University of Málaga, Spain (Plan Propio).

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

Declarations

Ethics Approval

This article does not contain any study with humans or other animals.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.IPCC (2019) Global warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D.

- 2.IPCC (2014) Climate change 2014: synthesis report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, R.K. Pachauri and L.A. Meyer (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 151 pp.

- 3.Millero FJ, Woosley R, Ditrolio B, Water J Effect of ocean acidification on the speciation of metals in seawater. Oceanography. 2009;22:72–85. doi: 10.5670/oceanog.2009.98. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beardall J, Stojkovic S, Larsen S. Living in a high CO2 world: impacts of global climate change on marine phytoplankton. Plant Ecol Divers. 2009;2:191–205. doi: 10.1080/17550870903271363. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rost B, Riebesell U (2004) Coccolithophores and the biological pump: responses to environmental changes. In: Coccolithophores: from molecular processes to global impact [Thierstein, H. R., Young, J. R. (Eds.)]. Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg, 99–125 pp.

- 6.Doney SC. Oceanography: plankton in a warmer world. Nature. 2009;444:695–696. doi: 10.1038/444695a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riebesell U, Tortell PD. Effects of ocean acidification on pelagic organisms and ecosystems. In: Gattuso JP, Hansson L, editors. Ocean acidification. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 99–121. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poulton AJ, Adey TR, Balch WM, Holligan PM. Relating coccolithophore calcification rates to phytoplankton community dynamics: regional differences and implications for carbon export. Deep-Sea Res. 2007;54:538–557. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2006.12.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ziveri P, de Bernardi B, Baumann KH, Stoll HM, Mortyn PG. Sinking of coccolith carbonate and potential contribution to organic carbon ballasting in the deep ocean. Deep Sea Res Part II Top Stud Oceanogr. 2007;54:659–675. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2007.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Broecker W, Clark E (2009) Ratio of coccolith CaCO3 to foraminifera CaCO3 in late Holocene deep sea sediments. Paleoceanogr Paleoclimatology 24: PA3205. 10.1029/2009PA001731

- 11.Westbroek P, Young JR, Linschooten K. Coccolith production (biomineralization) in the marine alga Emiliania huxleyi. J Protozool. 1989;36:368–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1989.tb05528.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paasche E (2002) A review of the coccolithophorid Emiliania huxleyi (Prymnesiophyceae), with particular reference to growth, coccolith formation and calcification-photosynthesis interactions. Phycol 40: 503–529. 2216/i0031–8884–40–6–503.1

- 13.Langer G, Nehrke G, Probert I, Ly J, Ziveri P. Strain-specific responses of Emiliania huxleyi to changing seawater carbonate chemistry. Biogeosciences. 2009;6:2637–2646. doi: 10.5194/bg-6-2637-2009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Read BA, Kegel J, Klute MJ, Kuo A, Lefebvre SC, Maumus F, et al. Pan genome of the phytoplankton Emiliania underpins its global distribution. Nature. 2013;499:209–213. doi: 10.1038/nature12221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mausz MA, Segovia M, Larsen A, Berger SA, Egge JK, Pohnert G. High CO2 concentration and iron availability determine the metabolic inventory in an Emiliania huxleyi-dominated phytoplankton community. Environ Microbiol. 2020;22:3863–3882. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.15160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moore TS, Dowell MD, Franz BA. Detection of coccolithophore blooms in ocean color satellite imagery: a generalized approach for use with multiple sensors. Remote Sens Environ. 2012;117:249–263. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2011.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engel A, Zondervan I, Aerts K, Beaufort L, Benthien A, Chou L, et al. Testing the direct effect of CO2 concentration on a bloom of the coccolithophorid Emiliania huxleyi in mesocosm experiments. Limnol Oceanogr. 2005;50:493–507. doi: 10.4319/lo.2005.50.2.0493. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barcelos e Ramos J, Müller MN, Riebesell U, Short-term response of the coccolithophore Emiliania huxleyi to an abrupt change in seawater carbon dioxide concentrations. Biogeosciences. 2010;7:177–186. doi: 10.5194/bg-7-177-2010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iglesias-Rodríguez MD, Halloran PR, Rickaby REM, Hall IR, Colmenero-Hidalgo E, et al. Phytoplankton calcification in a high-CO2 world. Science. 2008;320:336–340. doi: 10.1126/science.1154122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Segovia M, Lorenzo MR, Maldonado MT, Aud L, Berger SA, Tsagaraki TM, et al. Iron availability modulates the effects of future CO2 levels within the marine planktonic food web. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2017;565:17–33. doi: 10.3354/meps12025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lorenzo MR, Neale PJ, Sobrino C, León P, Vázquez V, Bresnan E, et al. Effects of elevated CO2 on growth, calcification, and spectral dependence of photoinhibition in the coccolithophore Emiliania huxleyi (Prymnesiophyceae)1. J Phycol. 2019;55:775–788. doi: 10.1111/jpy.12885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mackey KRM, Morris JJ, Morel FMM. Response of photosynthesis to ocean acidification. Oceanography. 2015;28:74–91. doi: 10.5670/oceanog.2015.33. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Segovia S, Lorenzo MR, Iñiguez C, García-Gómez C. Physiological stress response associated with elevated CO2 and dissolved iron in a phytoplankton community dominated by the coccolithophore Emiliania huxleyi. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2018;586:73–89. doi: 10.3354/meps12389. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riebesell U, Bellerby R, Engel A, Fabry VJ, Hutchins DA, Reusch TBH, et al. Comment on “Phytoplankton calcification in a high-CO2 world”. Science. 2008;322:1466. doi: 10.1126/science.1161096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beaufort L, Probert I, Garidel-Thoron T, Bendif EM, Ruiz-Pino D, Metzl N, Goyet C, Buchet N, Couple P, Grelaud M, Rost B, Rickaby RE, de Vargas C. Sensitivity of coccolithophores to carbonate chemistry and ocean acidification. Nature. 2011;476:80–83. doi: 10.1038/nature10295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith HEK, Tyrrell T, Charalampopoulou A, Dumousseaud C, Legge OJ, Birchenough S, et al. Predominance of heavily calcified coccolithophores at low CaCO3 saturation during winter in the Bay of Biscay. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:8845–8849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117508109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu Y-W, Eagle RA, Aciego SM, Gilmore RE, Ries JBA. A coastal coccolithophore maintains pH homeostasis and switches carbon sources in response to ocean acidification. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2857. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04463-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Riebesell U, Zondervan I, Rost B, Tortell PD, Zeebe RE, Morel FM. Reduced calcification of marine plankton in response to increased atmospheric CO2. Nature. 2000;407:364–367. doi: 10.1038/35030078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoppe CJM, Langer G, Rost B. Emiliania huxleyi shows identical responses to elevated pCO2 in TA and DIC manipulations. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 2011;406:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2011.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bach LT, Riebesell U, Schulz KG. Distinguishing between the effects of ocean acidification and ocean carbonation in the coccolithophore Emiliania huxleyi. Limnol Oceanogr. 2011;56:2040–2050. doi: 10.4319/lo.2011.56.6.2040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rokitta SD, John U, Rost B. Ocean acidification affects redox-balance and ion-homeostasis in the life-cycle stages of Emiliania huxleyi. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e52212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor AR, Chrachi A, Wheeler G, Goddard H, Brownlee C. A voltage-gated H+ channel underlying pH homeostasis in calcifying coccolithophores. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1001085. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kottmeier DM, Rokitta SD, Tortell PD, Rost B. Strong shift from HCO3- to CO2 uptake in Emiliania huxleyi with acidification: new approach unravels acclimation versus short-term pH effects. Photosynth Res. 2014;121:265–275. doi: 10.1007/s11120-014-9984-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldman JC, McCarthy JJ. Steady state growth and ammonium uptake of a fast-growing marine diatom. Limnol Oceanogr. 1978;23:695–703. doi: 10.4319/lo.1978.23.4.0695. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guillard RRL, Ryther JH. Studies of marine planktonic diatoms. I. Cyclotella nana Hustedt and Detonula confervacea (Cleve) Gran. Can J Microbiol. 1962;8:229–239. doi: 10.1139/m62-029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gordillo FJL, Jiménez C, Figueroa FL, Niell FX. Effects of increased atmospheric CO2 and N supply on photosynthesis, growth and cell composition of the cyanobacterium Spirulina platensis (Arthrospira) J Appl Phycol. 1998;10:461–469. doi: 10.1023/A:1008090402847. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robbins LL, Hansen ME, Kleypas JA, Meylan SC (2010) CO2calc: a user-friendly seawater carbon calculator for Windows, Mac OS X and iOS (iPhone). U. S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2010–1280.

- 38.Grand G. Determination of the equivalence point in potentiometric titrations of seawater with hydrochloric acid. Oceanol Acta. 1952;5:209–218. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marie D, Partensky F, Vaulot D, Brussaard CPD (1999) Enumeration of phytoplankton, bacteria, and viruses in marine samples. Curr Protoc Cytom 11: 11.11. 1002/0471142956.cy1111s10 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Larsen A, Castberg T, Sandaa RA, Brussaard CPD, Egge J, et al. Population dynamics and diversity of phytoplankton, bacteria and viruses in a seawater enclosure. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2001;221:47–57. doi: 10.3354/meps221047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wellburn AR. The spectral determination of chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b, as well as total carotenoids, using various solvents with spectrophotometers of different resolution. J Plant Physiol. 1994;144:307–313. doi: 10.1016/S0176-1617(11)81192-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schreiber U, Schliwa U, Bilger W. Continuous recording of photochemical and non-photochemical chlorophyll fluorescence quenching with a new type of modulation fluorometer. Photosynth Res. 1986;10:51–62. doi: 10.1007/BF00024185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eilers PHC, Peters JCH. A model for the relationship between light intensity and the rate of photosynthesis in phytoplankton. Ecol Model. 1988;42:199–215. doi: 10.1016/0304-3800(88)90057-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Segovia M, Berges JA (2009) Inhibition of caspase-like activities prevents the appearance of reactive oxygen species and dark-induced apoptosis in the unicellular chlorophyte Dunaliella tertiolecta. J Phycol 45: 1116–1126. 1111/j.1529–8817.2009.00733.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Tortell PD, Trimborn S, Li Y, Rost B, Payne CD. Inorganic carbon utilization by Ross Sea phytoplankton across natural and experimental CO2 gradients. J Phycol. 2010;46:433–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2010.00839.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mercado JM, Gordillo FJL, Figueroa FL, Niell FX. External carbonic anhydrase and affinity for inorganic carbon in intertidal macroalgae. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 1998;221:209–2020. doi: 10.1016/S0022-0981(97)00127-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iñiguez C, Galmés J, Gordillo FJL. Rubisco carboxylation kinetics and inorganic carbon utilization in polar versus cold-temperate seaweeds. J Exp Bot. 2019;70:1283–1297. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ery443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Young JR, Westbroek P. Genotypic variation in the coccolithophorid species Emiliania huxleyi. Mar Micropaleontol. 1991;18:5–23. doi: 10.1016/0377-8398(91)90004-P. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.De Bodt C, Van Oostende N, Harlay J, Sabbe K, Chou L. Individual and interacting effects of pCO2 and temperature on Emiliania huxleyi calcification: study of the calcite production, the coccolith morphology and the coccosphere size. Biogeosciences. 2010;7:1401–1412. doi: 10.5194/bg-7-1401-2010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Triantaphyllou M, Dimiza M, Krasakopoulou E, Malinverno E, Lianou V, Souvermezoglou E. Seasonal variation in Emiliania huxleyi coccolith morphology and calcification in the Aegean Sea (Eastern Mediterranean) Geobios. 2010;43:99–110. doi: 10.1016/j.geobios.2009.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bach LT, Bauke C, Meier KJS, Riebesell U, Schulz KG. Influence of changing carbonate chemistry on morphology and weight of coccoliths formed by Emiliania huxleyi. Biogeosciences. 2012;9:3449–3463. doi: 10.5194/bg-9-3449-2012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Young JR, Ziveri P. Calculation of coccolith volume and its use in calibration of carbonate flux estimates. Deep Sea Res Part II: Top Stud in Oceanogr. 2000;47:1679–1700. doi: 10.1016/S0967-0645(00)00003-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Young JR, Poulton AJ, Tyrrell T. Morphology of Emiliania huxleyi coccoliths on the northwestern European shelf—is there an influence of carbonate chemistry? Biogeosciences. 2014;11:4771–4782. doi: 10.5194/bg-11-4771-2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bollmann J, Herrle JO. Morphological variation of Emiliania huxleyi and sea surface salinity. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2007;255:273–288. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2006.12.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaying V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schneider CA, Rasband W, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boller AJ, Thomas PJ, Cavanaugh CM, Scott KM. Low stable carbon isotope fractionation by coccolithophore RuBisCO. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2011;75:7200–7207. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2011.08.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilkes EB, Pearson A. A general model for carbon isotopes in red-lineage phytoplankton: interplay between unidirectional processes and fractionation by RubisCO. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2019;265:163–181. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2019.08.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Young JR, Geisen M, Cros L, Kleijne A, Sprengel C, Probert I, et al. A guide to extant calcareous nannoplankton taxonomy. J Nannoplankt Res. 2003;1:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kegel JU, John U, Valentin K, Frickenhaus S. Genome variations associated with viral susceptibility and calcification in Emiliania huxleyi. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e80684. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shi D, Xu Y, Morel FMM. Effects of the pH/pCO2 control method on medium chemistry and phytoplankton growth. Biogeosciences. 2009;6:1199–1207. doi: 10.5194/bg-6-1199-2009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Egge JK, Thingstad TF, Larsen A, Engel A, Wohlers J, Bellerby RGJ, et al. Primary production during nutrient-induced blooms at elevated CO2 concentrations. Biogeosciences. 2009;6:877–885. doi: 10.5194/bg-6-877-2009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hopkinson BM, Xu Y, Shi D, McGinn PJ, Morel FMM. The effect of CO2 on the photosynthetic physiology of phytoplankton in the Gulf of Alaska. Limnol Oceanogr. 2010;55:2011–2024. doi: 10.4319/lo.2010.55.5.2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sobrino C, Ward ML, Neale PJ. Acclimation to elevated carbon dioxide and ultraviolet radiation in the diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana: effects on growth, photosynthesis, and spectral sensitivity of photoinhibition. Limnol Oceanogr. 2008;53:494–505. doi: 10.2307/40006434. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Langer G, Bode M. CO2 mediation of adverse effects of seawater acidification in Calcidiscus leptoporus. Geochem Geophys Geosyst. 2011;12:1–8. doi: 10.1029/2010GC003393. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fukuda SY, Suzuki Y, Shiraiwa Y. Difference in physiological responses of growth, photosynthesis and calcification of the coccolithophore Emiliania huxleyi to acidification by acid and CO2 enrichment. Photosynth Res. 2014;121:299–309. doi: 10.1007/s11120-014-9976-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Blanco-Almeijeiras S, Heather MS, Hongrui Z, Brian MH. Influence of temperature and CO2 on plasma-membrane permeability to CO2 and HCO3− in the marine haptophytes Emiliania huxleyi and Calcidiscus leptoporus (Prymnesiophyceae) J Phycol. 2020;56:1283–1294. doi: 10.1111/jpy.13017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Suffrian K, Schulz KG, Gutowska MA, Riebesell U, Bleich M. Cellular pH measurements in Emiliania huxleyi reveal pronounced membrane proton permeability. New Phytol. 2011;190:595–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.García-Gómez C, Gordillo FJL, Palma A, Lorenzo C, Segovia M. Elevated CO2 alleviates high PAR and UV stress in the unicellular chlorophyte Dunaliella tertiolecta. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2014;13:1347–1358. doi: 10.1039/c4pp00044g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tortell PD, Payne C, Gueguen C, Strzepek RF, Boyd PW, Rost B. Inorganic carbon uptake by Southern Ocean phytoplankton. Limnol Oceanogr. 2008;53:1266–1278. doi: 10.4319/lo.2008.53.4.1266. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lorenzo MR, Iñiguez C, Egge JK, Larsen A, Berger SA, García-Gómez C, et al. Increased CO2 and iron availability effects on carbon assimilation and calcification on the formation of Emiliania huxleyi blooms in a coastal phytoplankton community. Environ Exp Bot. 2018;148:47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2017.12.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sharkey TD, Berry JA (1985) Carbon isotope fractionation of algae as influenced by an inducible CO2 concentrating mechanism, p. 389–401. In W. J. Lucas and J. A. Berry [eds.], Inorganic carbon isotope uptake by aquatic photosynthetic organisms. American Society of Plant Physiologists.

- 73.Rost B, Richter KU, Riebesell U, Hansen PJ. Inorganic carbon acquisition in red tide dinoflagellates. Plant Cell Environ. 2006;29:810–822. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]