Abstract

Introduction:

Research shows that participation in political activism on social media is linked to psychological stress. Additionally, race-based stress disproportionately affects minorities and is linked to greater psychological symptoms. Yet, the impact of the social media presence of Black Lives Matter (BLM) on mental health has yet to be meaningfully assessed.

Methods:

This study assessed whether engagement with BLM-related social media vignettes was related to mental health symptoms in two non-clinical samples (total N = 389), using a mixed-methods design. Participants completed an online survey with social media vignettes, self-report inventories of mental health symptoms, and open-ended questions about experiences with and the impact of BLM.

Results:

Correlations revealed that greater engagement with BLM-related social media posts was related to more severe mental health symptoms. Further, moderation analyses revealed that race significantly moderated the relationship between engagement and anxiety and trauma-related symptoms, such that these relationships were stronger for participants who identified as racial minorities. Qualitative analyses revealed that most participants who were engaged in mental health treatment had not discussed BLM-related topics with their providers, despite many participants reporting disrupted relationships and negative emotions due to exposure to BLM-related social media content.

Discussion:

Taken together, results suggest that engagement with BLM-related content online is linked to increased mental health symptoms, but these issues are infrequently addressed in treatment. Future research should extend these findings with clinical samples, assess the comfort of therapists in addressing these topics in therapy, and develop interventions to improve mental health in digital activists.

Keywords: Black lives matter, racial minority health, activism, social media, race-based stress

Introduction

Social activism, defined as participatory actions that intend to bring about societal change (Brenman & Sanchez, 2014), is a permanent fixture in national and global communities. Social activism often manifests as a collective action that follows a culmination of strife, grief, or exhaustion in the face of adversity. Through collective action, people work together to appraise social systems, address social issues within them, and rectify the impact of social injustices. These are issues that are often relevant to the everyday lives of specific groups of people, and understandably, many people active in social movements (i.e., activists) are members of directly affected communities. It is important to understand the effect of social activism on participating activists, especially when the social issues targeted may be integral to their personal interests have crucial implications for their well-being (Brenman & Sanchez, 2014). This is further complicated when one considers how the pandemic has pushed a significant portion of social activism online into virtual spaces, including social media. This shift in social activism to online spaces is one example of digital activism, or socially relevant activism that takes place significantly online, through websites, social media, or even hackers shutting down websites (George & Leidner, 2019). A relevant example of this shift is the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement in the summer of 2020 (Ruffin, 2021).

BLM can be described as a collective resistance movement centered around rectifying the dehumanizing aspects of the Black experience. The mission of BLM involves challenging institutional forms of racism and state-sanctioned violence (Clayton, 2018). In practice, the ubiquitous presence of BLM on social media has been highly instrumental in its impact (Clayton, 2018). Grassroots mobilization tied to the lynching of Black people and subsequent unpunished murders runs deep in American history, yet violence against racial minorities remains a major issue today. One of the most well-known historical examples of this reoccurring pattern of mobilization in response to racial violence is the actions that followed the lynching of Emmett Till. His mother’s brave efforts to unveil the cruelty that faced Black Americans elicited a powerful national response of mass mobilization, serving as the spark that ignited the Civil Rights Movement (Harold & DeLuca, 2005). The publication of images from his open-casket funeral in Jet magazine were, in many ways, a predecessor to future viral depictions of modern-day lynching at the hands of police. Much like the publicized footage of the murder of George Floyd in 2020, the images from his funeral were evidence of heinous injustices and testaments to the power that images can have once they reach a wide enough audience. The Black Lives Matter movement and the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950’s and 1960’s share the common thread of undeniable visibility spurring massive organized social action (Harold & DeLuca, 2005; Ruffin, 2021). Yet, the BLM movement has been more widely supported than the Civil Rights Movement was in its time (Clayton, 2018), which may be due, in part, to greater engagement by non-Black citizens and accessibility of content due to social media, though this area is relatively under-studied.

Despite the historical and cultural importance of these events, research has yet to comprehensively assess what effect these publicized acts of violence have on those who bear witness to them as activists. To our knowledge, only one study has directly assessed this question. First and colleagues (2020) found that greater protest engagement following the murder of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri was directly related to higher post-traumatic stress symptoms. The results also revealed that greater exposure to media covering the event was related to post-traumatic stress symptoms, and this effect was more pronounced for Black participants (First et al., 2020). This was because Black participants, relative to White participants, were more likely to engage in protests and consume relevant media (First et al., 2020). This study highlights the potential implications that exposure to racial injustice and corresponding social activism may have for mental health. However, more work is needed, specifically with respect to possible impacts of BLM’s expansive social media presence.

The social media hashtag #BlackLivesMatter began after the death of Trayvon Martin in 2012, whose killer, George Zimmerman, was acquitted in a court of law. BLM grew in subsequent years following the highly publicized deaths of Michael Brown in 2014 and George Floyd in 2020 (Ransby, 2018). Indeed, protesters flooded the streets following the murder of George Floyd to express their outrage (Van Dijcke & Wright, 2020), despite the personal harm they risked due to the ongoing coronavirus pandemic. In addition to more traditional protests, though, these highly publicized deaths led to individuals engaging in online conversations about the institution of racism and the issue of police brutality on an unprecedented scale. Between the first mention of #BlackLivesMatter in July of 2013 to 5 years later in July of 2018, the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag was used approximately 30 million times on Twitter (Anderson et al., 2018). In comparison, between May 26 and June 7 of 2020, a period of just 12 days during the height of the unrest resulting from the murder of George Floyd (Ruffin, 2021), the same hashtag was used nearly 48 million times on Twitter. The daily usage of the hashtag averaged at nearly 3.7 million and peaked on May 28, 3 days after George Floyd’s death in police custody (Anderson et al., 2020).

This illustrates the sheer volume of BLM-related content on social media platforms in the summer of 2020. This massive flow of online engagement hosted a plethora of discussions about violations of the human rights of Black Americans, as well as critical conversations about the uprisings and social mobilization that followed in response (Ruffin, 2021). Across social media platforms, posts related to BLM, including videos and images of violence against Black Americans, were virtually inescapable for social media users. Yet, the impacts of this high level of exposure are currently unknown.

Many BLM-relevant posts fall within the sphere of digital activism. Digital activism can vary in terms of its effort required by the activist, from being the organizer of an in-person protest through the creation of a Facebook event, to commenting your disagreement about a law or social outcome on Twitter. A widespread method of digital activism is engagement with social media posts, such as liking, sharing, or commenting on a post, which are particularly visible to others (Vromen et al., 2015). To our knowledge, there have been no studies assessing how engagement with social media posts related to instances of racial violence may impact the health or functioning of individuals in the general population. This exposure and engagement may be especially critical for the mental health of people identifying as racial minorities, who may be exposed to frequent reminders of racial violence (Scott et al., 2017).

The importance of understanding the impacts of social media exposure to racial violence cannot be overstated. Most Americans regularly use social media, with research suggesting that 7 out of 10 American adults under 30 use Facebook (just one of several large social media sites; Auxier & Anderson, 2021). Past research has found that a multitude of psychological harms, including negative impacts on self-esteem and increased rates of mood symptoms, are associated with general engagement with social media (Aalbers et al., 2019; Alfasi, 2019; Pagoto et al., 2019). These harms can be further contextualized by how individuals utilize social media (i.e., social activism versus entertainment). For example, 36% of adult social media users in the U.S. report using sites like Facebook and Twitter to post social activism-related content and to gain information about social movements (Auxier, 2020), which may be linked to higher psychological distress (Hisam et al., 2017). Further, research suggests robust racial minority engagement with digital activism; 45% of Black social media users reported using social media to connect with social activism groups, while only 29% of White social media users reported doing the same (Auxier, 2020). Given the nature of movements such as BLM, whose online conversations frequently center on cycles of racial trauma and the imminent threat of racial violence, stressors may emerge in online discourse that disproportionately impact racial minorities (Clayton, 2018). Therefore, considering the disparity between Black and White social media users coupled with the more personally relevant nature of BLM for people identifying as racial minorities, the impacts of BLM discourse on social media could be disproportionately affecting Black social media users.

Previous research has shown that exposure to race-based stressors is linked to greater psychological symptoms, including anger, depression, and hypervigilance (Carter & Kirkinis, 2021; Torres Rivera & Comas-Díaz, 2020). These harms are primarily linked to engagement with race-based stressors but can also be linked to engagement with micro-aggressive content (Eschmann et al., 2020). Microaggressions are defined as situational slights that can be verbal, environmental, or behavioral, and that can occur both with or without intention and have negative consequences for marginalized and stigmatized groups (Sue, 2010). Racial microaggressions specifically reinforce harmful, racially discriminatory narratives and encourage ‘othering’ and hostility (Williams, 2020).

Racial microaggressions are particularly relevant for BLM. Social media discussions about BLM and police brutality are public forums rife with displays of, and engagement with, micro-aggressive content. By its very nature, BLM presents itself as a challenge to the status quo (Ruffin, 2021), and those not aligned with the principles espoused by BLM may view themselves as needing to organize and espouse their own, conflicting opinions. This is most evident in the reactive countermovement “All Lives Matter” that pervaded social media spaces and BLM conversations at the height of the movement. Outsiders introduced this slogan to BLM discourse with hostility and subversive intent, which is inherently racially motivated in this context (Keiser, 2021). Use of the term “All Lives Matter” in this context, as well as subsequent rhetoric surrounding it, can be considered a racial microaggression, and may contribute to greater frequency of mental health symptoms related to racial trauma (Moody & Lewis, 2019), as well as anxiety and stress in racial minority groups (Santos & VanDaalen, 2018). This and other racial microaggressions within BLM-related social media discussions adds to the potential for psychological harm for social media users engaging in conversations about BLM and participating in online forms of activism.

Even with the risk for negative outcomes, engagement with social activism is grounded in personal values, and is therefore relevant for discussion in psychotherapeutic settings (Crethar & Ratts, 2008). This professional issue is becoming more pressing, as increased awareness of racial violence and sociopolitical unrest (linked to increased media coverage) has been noted in the therapy context. For example, counseling professionals reported an influx of clients bringing distress and fear directly related to current political events and issues into session during the weeks before and after the 2016 presidential election (McCarthy & Saks, 2019). This study found notable increases in presentations of anxiety, stress, and resentment, as well as the use of negative coping strategies in response to emotions induced by the election (McCarthy & Saks, 2019). Another study found that the majority of Americans (59%) engaged in increased negative coping behaviors like drinking, smoking, arguing, and poor diet following distress related to major sociopolitical events (Stosny, 2017). Thus, the emotional, behavioral, and psychological impacts of sociopolitical events have already shown to be relevant in counseling sessions. Yet, no work to date has investigated how reactions to BLM and its ubiquitous presence on social media has emerged in therapeutic settings.

Despite the possible link between social media activism and mental health symptoms, no studies to our knowledge have examined the link between engagement with social media content relevant to BLM and mental health outcomes in a general sample. Furthermore, we have yet to gain an understanding of how BLM posts, a unique race-based stressor, might have differential impacts for those who identify as racial minorities. Lastly, no work to our knowledge has been conducted to understand how discussions of BLM may be incorporated in therapeutic treatment. As such, this study aimed to assess the relationship between engagement with BLM-related content and mental health symptoms and whether these relationships differ depending on participants’ race. We hypothesized that greater engagement with social media posts related to BLM would be correlated with greater mental health symptoms, and that this effect would be stronger for participants identifying as racial minorities. Further, this study aimed to explore participants’ self-reported discussions regarding BLM in mental health treatment settings. To address this, we conducted qualitative analyses to assess whether BLM-related topics were discussed in therapeutic settings as well as participants’ perceptions of those discussions. Qualitative analyses were considered exploratory.

Methodology

Participants & Procedures

Participants for this study were recruited from two sources. An undergraduate sample from the University of Southern Mississippi was recruited through the institution’s SONA system (n = 141). SONA listings are publicly available to all undergraduate students enrolled in psychology courses, with participation in research studies serving as an extra credit incentive in some courses. Additional participants were recruited through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (n = 248). To be eligible to participate, MTurk workers were required to reside in the United States and to have at least a 95% approval rate for Human Intelligence Tasks (HITs) through MTurk. All participants had to speak English and be 18 years of age or older. All participants provided informed consent to participate.

After providing informed consent, participants completed an online survey designed to be completed in 30 minutes or less. Participants responded to a set of measures designed to assess mental health symptoms. Participants also viewed a series of vignettes and answered questions aimed to assess engagement with social media. Participants were also asked to write at least 100 words in response to two qualitative prompts at the end of the survey. Participants were informed about the presence of attention check items during the consent process and were encouraged to answer each question to the best of their ability. Additionally, to promote high quality data, MTurk participants were offered a bonus payment if they provided high quality data (i.e., answered all attention check items correctly). All procedures were approved by the local institutional review board.

Measures

The Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ) is a brief self-report measure assessing duration and frequency of depression-related symptoms within the last 2 weeks. The PHQ-8 is a shortened version of the PHQ-9, excluding the item on suicidality. The questionnaire is on a 4-point scale, and higher scores indicate greater depression (Kroenke et al., 2001, 2009). In this sample, internal consistency was acceptable (Cronbach’s alpha = .90).

The General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD) questionnaire is a brief validated self-report measure to assess severity of anxiety symptoms on a 4-point rating scale (i.e., minimal, mild, moderate, and severe). The questions focus on the frequency and duration of anxiety symptoms within the last 2 weeks, and higher scores indicate greater anxiety severity (Spitzer et al., 2006). In this sample, internal consistency was acceptable (Cronbach’s alpha = .93).

The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-5 (PCL) is a 20-item self-report measure on a 5-point scale to assess duration and frequency of trauma-related symptoms within the past month. Higher scores indicate more trauma-related symptoms (Blevins et al., 2015). In this sample, internal consistency was acceptable (Cronbach’s alpha = .97).

The Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire-Brief Revised (SPQ-BR) is an abbreviated assessment for schizotypal traits which includes 32 Likert-type items. The assessment is scored on a 5-point scale, with higher scores indicating greater schizotypy (Cohen et al., 2010). In this sample, internal consistency was acceptable (Cronbach’s alpha = .87).

Vignettes.

Eight vignettes were developed by the research team to emulate social media posts reflecting varied levels of support of BLM. Four descriptive levels of support for BLM were defined: highly supportive, moderately supportive, moderately unsupportive, and highly unsupportive. Two vignettes were created per level of support. The vignettes were designed to appear as though they might be posted on a social media site. Vignettes can be found in the appendix 1.

Engagement.

Immediately following each vignette, participants were presented with a series of Likert-type questions intended to assess their emulated engagement with the vignette “posts.” Questions assessed the likelihood that the participant would like the post, share the post, or comment on the post, as well as their level of agreement with the post’s content. Overall “engagement” was calculated by taking the average of participants’ self-reported likelihood to like, share, or comment on each vignette if they saw it on social media, taking into consideration participants’ agreement with the varied BLM content. Average engagement scores only included like and share ratings for vignettes with which participants expressed some level of content agreement, given that participants would be unlikely to express agreement with a post by liking it or disseminating it through sharing if they disagreed with the content of the post. Comment ratings were included for all vignettes. Note that for the like rating, participants were instructed to report on their likelihood to like posts only, not to use other reactions available on various social media platforms (e.g., emoji reactions expressing anger or laughing, etc.). For the final engagement score, values ranged from 1–5, with lower scores indicating greater likelihood to engage. After each vignette, participants were asked two Likert-type self-report items assessing the impact of social media posts about BLM on their functioning and mood during the summer of 2020, when BLM social media posts were at their peak.

Qualitative Questions.

Included in the survey were two qualitative questions intended to explore other dimensions of how participants may have been impacted by BLM-related social media content (See appendix 2 for full questions). For participants who reported receiving mental health treatment since March 2020, the first question asked them to describe whether they spoke with their mental healthcare provider about any BLM-related topics. This question also inquired about the overall experience of the discussion (e.g., Was this discussion welcome?; Did it have any impact on your relationship with your provider?). For those who did not discuss these topics, we inquired regarding the reasoning for that choice. All participants responded to the second question, which was intended to assess how posts similar to the vignettes may have impacted their relationships, functioning, and mental health. This question also served to gain insight into coping strategies that were adopted by participants. For each item, participants were asked to write at least 100 words.

Analyses

To ensure high-quality data, participants who failed to correctly answer 50% of attention check items or whose survey response time was in the fastest 10% of participants were removed from the final sample. Descriptive statistics were calculated, and MTurk and SONA samples were compared on demographic, engagement, and symptom variables, using t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square statistics for categorical variables. Pearson’s R correlations assessed the relationships between the engagement variable and mental health symptoms on the PHQ-8, GAD-7, PCL-5, and SPQ-BR. Hayes’ PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2017) was used to conduct moderation analyses examining whether the relationships between engagement and various mental health symptoms differed between racial minority and non-minority groups. If a significant interaction was found (p < .05), we probed the interaction using the pick-a-point approach (Rogosa, 1980) to examine whether the relationship between engagement and mental health symptoms was stronger for participants identifying as racial minorities.

To analyze qualitative responses, a conventional content analysis approach was applied (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). The coding team read the qualitative responses and generated potential codes for each of the two questions. They then came to a consensus on the final codebook, which included five codes for the first question, and four relevant codes for the second question. All codes emerged solely from the data; no preconceived codes were used (Kondracki et al., 2002). Four coders were then trained with this codebook and all responses were coded independently by two coders. Negative cases and disconfirming evidence were discussed and processed with the team as needed (Mays & Pope, 2000). When discrepancies were found between the coders, they discussed and came to a consensus on the most appropriate codes. More than one code could be assigned to any given response, and coders came to a consensus for each response.

Results

Participants

After excluding participants who did not provide high-quality data, the final sample size was 281 participants (SONA n = 123; MTurk n = 158). Participants identified primarily as White (74.4%), with smaller portions of participants identifying as Black (15.7%), Asian (4.6%), Alaskan Indian or Native American (1.1%), Other Race (1.1%), or those who identified with more than one race (3.2%). Racial minority groups were collapsed into one group to ensure adequate sample sizes for analyses (MTurk n = 28; SONA n = 44). The samples were significantly different in several ways. The MTurk sample (17.8% racial minority participants) was significantly more likely to be White than the SONA sample (35.2% racial minority participants; X2 (1) = 10.97, p < .001). The MTurk sample was also significantly older (M = 37.82, SD = 11.68) than the SONA sample (M = 20.35, SD = 4.59; t (278) = 15.61, p < .001). Further, there were significant differences in overall engagement with the vignettes between the groups; SONA participants were less likely to engage (M = 3.57, SD = 0.93) with the vignettes than MTurk participants (M = 3.03, SD = 1.08; t (279) = −4.39, p < .001). Additionally, SONA participants reported higher levels of both depression (t (277) = −2.26, p = .012) and anxiety symptoms (t (277 = 9) = −2.52, p = .006) than MTurk participants. Significant differences across multiple demographic and symptom variables informed the decision to conduct subsequent analyses separately for the SONA and MTurk samples.

Vignette Engagement

Pearson’s correlation analyses were conducted to assess the relationship between level of engagement with posts and mental health symptoms. See Table 1 for correlations, conducted separately in each sample. Higher engagement with the BLM vignettes was significantly correlated with higher levels of anxiety, depression, schizotypy, and trauma-related symptoms in the MTurk sample. Further, higher engagement was associated with self-reported lower mood and poorer functioning. Similarly, in the SONA sample, higher engagement was related to higher levels of anxiety, schizotypy, and trauma-related symptoms, as well as with self-reported lower mood and poorer functioning. However, engagement was not significantly correlated with depression symptoms in the SONA sample.

Table 1.

Correlations.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Engagementa | — | −.25** | −.14 | −.20* | −.31** | −.29** | −.37** |

| 2. | GAD | −.41** | — | −.71** | .79** | .65** | .16 | .13 |

| 3. | PHQ | −.40** | .86** | — | .76** | .65** | −.01 | −.08 |

| 4. | PCL | −.57** | .84** | .81** | — | .67** | −.02 | .02 |

| 5. | SPQ-BR | −.53** | .68** | .66** | .77** | — | .17 | .15 |

| 6. | Daily functioning | −.45** | .44** | .47** | .50** | .42** | — | .53** |

| 7. | Mood | −.36** | .34** | .33** | .45** | .40** | .63** | — |

Note. Correlations for the MTurk sample are displayed on the bottom left quadrant of the matrix. Correlations for the SONA sample are displayed on the top right quadrant of the matrix (shaded).

Lower engagement scores indicate greater engagement with the BLM-related vignettes.

Correlation is significant at the .05 level.

Correlation is significant at the .01 level. GAD = General Anxiety Disorder-7 questionnaire. PHQ = Patient Health Questionnaire-8. PCL = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-5. SPQ-BR = Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire- Brief Revised.

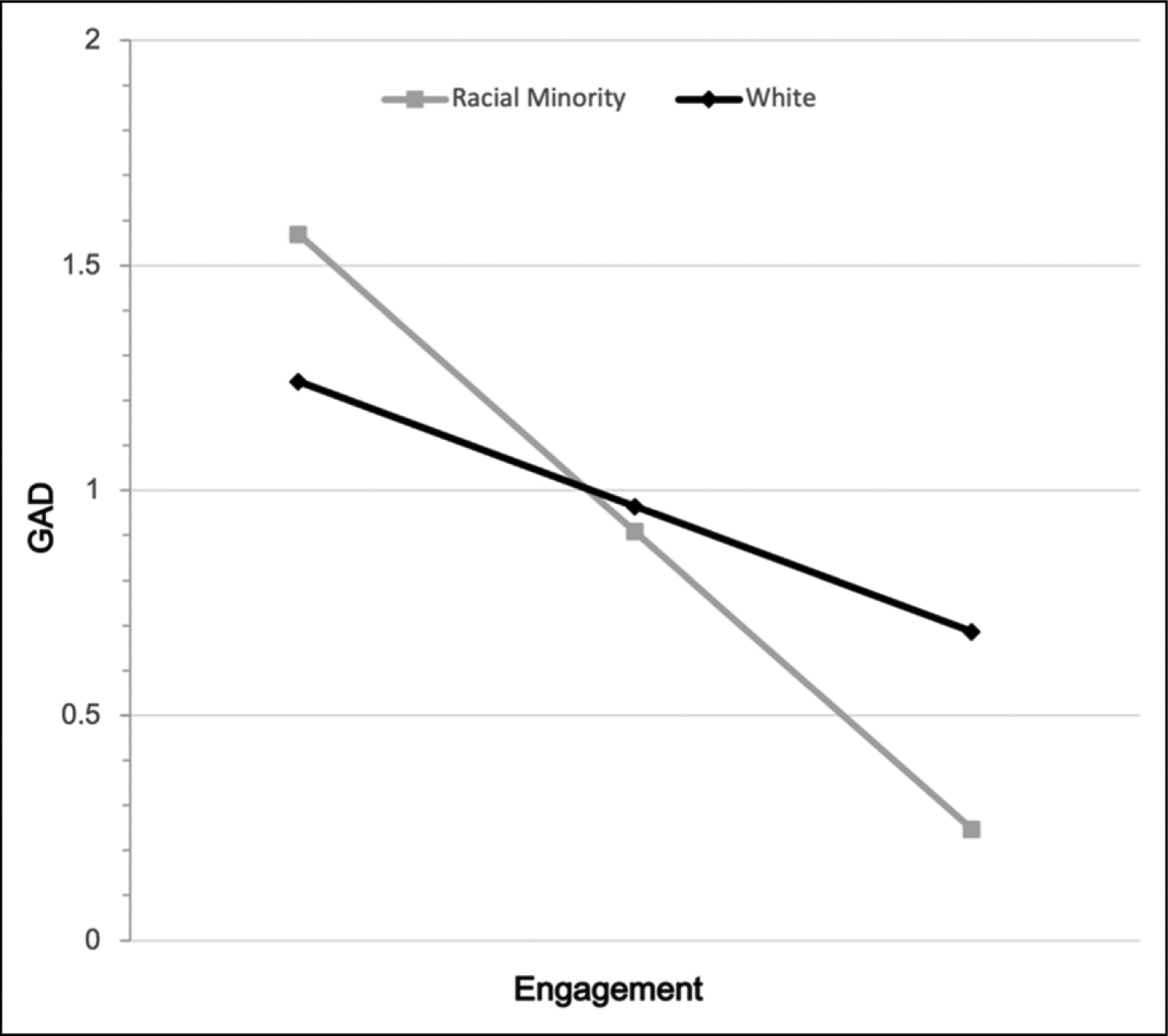

Moderation analyses were conducted to determine if the relationships between engagement and mental health symptoms differed between participants who identified as racial minorities and those who identified as White. In the SONA sample, there was no significant interaction between engagement with the vignettes and racial minority status for depression (R2 = .05, F (3, 118) = 2.17, p = .42), anxiety (R2 = .07, F (3, 117) = 3.06, p = .80), trauma-related symptoms (R2 = .05, F (3, 118) = 1.95, p = .65), or schizotypy (R2 = .09, F (3, 118) = 4.07, p = .90). In the MTurk sample, there was a significant interaction between engagement and racial minority status for trauma-related symptoms (See Figure 1; R2 = .36, F (3, 153) = 29.14, p < .01), as well as for anxiety symptoms (See Figure 2; R2 = .19, F (3, 152) = 12.07, p < .05). This interaction was such that higher engagement was more strongly related to trauma-related and anxiety symptoms for racial minority participants than for White participants. There was no significant interaction between engagement with the vignettes and racial minority status for depression (R2 = .17, F (3, 153) = 10.67, p = .21) or schizotypy (R2 = .29, F (3, 153) = 20.96, p = .08) in the MTurk sample.

Figure 1.

Visualization of the relationship between vignette engagement and trauma-related symptoms, moderated by racial minority status. Lower engagement scores indicate a higher likelihood to engage with the social media vignettes. PCL-5 = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-5.

Figure 2.

Visualization of the relationship between vignette engagement and anxiety symptoms, moderated by racial minority status. Lower engagement scores indicate a higher likelihood to engage with the social media vignettes. GAD = General Anxiety Disorder-7 questionnaire.

Qualitative Findings

The qualitative portion of the analysis included only the SONA sample. This decision was based on inconsistent quality of responses from MTurk participants, as they frequently skipped the qualitative questions or plagiarized responses from easily accessible internet sources. These same issues were not identified in the SONA sample and thus the SONA sample was deemed adequate for qualitative analyses.

The first open-ended question was only presented to participants who reported that they received mental health services since March 2020. The question assessed if BLM-related topics were discussed with their mental healthcare providers, the impact the conversation may have had on the therapeutic relationship, and the decisions behind not discussing those topics with their mental healthcare providers, if relevant. There were 28 respondents for this question, though only two participants identified as Black (n = 2).

Five codes emerged from this data. The first was Wasn’t Discussed, which was used when participants endorsed not discussing these topics with their mental health provider. The second code was Not Relevant, which was characterized by participants expressing that they spoke with their mental healthcare provider about BLM-related topics, but that they perceived the conversation to be irrelevant to their mental health or treatment goals. The third code to emerge for this question was No Impact. Responses with this code involved participants expressing that they spoke to their mental healthcare provider about BLM-related topics, and the discussion did not negatively or positively impact their therapeutic relationship. The fourth code to emerge was Positive Impact, which was assigned to responses in which participants expressed that they spoke to their mental healthcare provider about BLM-related topics and the discussion had a positive or meaningful impact on their therapeutic relationship. Finally, the fifth code was Personally Negative, which was characterized by participants expressing that while they did not discuss BLM-related topics with their mental health care provider, they did acknowledge that BLM-related content negatively affected their mental health.

The most frequent theme identified was Wasn’t Discussed, revealing that most respondents did not discuss BLM with their mental healthcare providers (75%). Three responses in our sample (10.7%) were coded as Personally Negative, wherein participants reported that they experienced significant distress related to posts and coverage of BLM but did not discuss it with their mental healthcare providers. Participants’ reasons for not discussing BLM with their mental healthcare provider ranged from irrelevance for primary treatment-seeking goals to not wanting to make therapy a political space. Participant #120 said, “I feel like the situation was political and I did not want to bring politics into my healthcare.” While some felt like BLM was not an appropriate topic for therapeutic settings, participants whose responses were coded as Positive Impact expressed that it was helpful to talk about BLM with their provider. This was illustrated by Participant #23, who wrote, “It did not negatively affect my relationship with the provider, it actually open up more conversation on the topic. The discussion was very welcomed…It helped me get my thoughts out there with someone other than my parents or social media.” In contrast, there were also those who experienced negative impacts from these conversations. Notably, one participant reported leaving therapy entirely after hearing their therapist share a political comment, unrelated to BLM, that made them uncomfortable. Participant #123 said, “My therapist made an unrelated comment about something positive Trump had done during his presidency- it had nothing to do with the topic. It was definitely off-putting, and I never saw that therapist again.” Overall, most participants did not discuss BLM with their mental healthcare provider, but of those who did, almost all reported that they benefitted from relevant, targeted discussions, or that it did not affect their relationship with their treatment provider. We were unable to examine differences in participants’ responses based on their racial identity due to only 2 of the 28 respondents to this question identifying as Black.

Participants who responded to the second question were more diverse than those who responded to the first. While still predominantly White (n = 79), there was greater representation of participants who identified as Black (n = 27), Asian (n = 3), Multiple Races (n = 4), or another race (n = 2). There were four relevant codes that emerged from the second qualitative question concerning the ways BLM-related content on social media may have impacted participants’ mood, functioning, and relationships. The first was Disrupted Relationships, which was defined as damage, increased caution, social isolation, or loss of social relationships (including secondhand observation, e.g., seeing the effect that BLM had on others’ relationships) in response to BLM-related social media content. The second code to emerge was Withdrew Electronically, which was distinguished by participants expressing withdrawal from social media for various reasons, including avoidance of potential conflict and a sense that social media had lost its “escapist” qualities with the influx of negative content. The third code was Decreased Functioning, which was defined by participants describing negative impacts in daily functioning and/or reduced interaction with the outside world related to BLM-related social media posts and events. The fourth code to emerge was Negative Emotions, which was distinguished by participants describing a variety of direct or indirect negative impacts on emotions or mental health. Importantly, no participants endorsed positive outcomes (i.e. increased functioning or positive emotions) related to BLM social media posts or events.

The second qualitative question was not conditional and was presented to all participants, resulting in 116 responses. Most notably, 40.5% of responses were categorized in the Negative Emotions theme. These included, but were not limited to, direct negative impacts on participants’ mental health, emotional distress related to relationship disruptions or losses, anxiety and fear, including increased fear for the safety of loved ones and fear of experiencing police brutality themselves. Participant #136 wrote: “Being in an [sic] society where social media plays a huge role in your life it could cause you to look at yourself differently or think that others see you as a threat. Being seen in public was very hard being an African American, people could stereotype you easily or look at you with hatred because of what’s happening on social media worldwide.” Additionally, 25% of respondents reported experiencing or witnessing Disrupted Relationships. These responses detailed a range of social difficulties, from feeling isolated due to differing views, to relationships being damaged, or completely severing social ties due to disagreements over BLM social media posts. Further, in the Withdrew Electronically theme, 22% of participants reported avoiding or reducing time spent on social media as a coping mechanism for distress and a protective measure to avoid conflict or BLM coverage. Participant #24 wrote, “The only thing I did to ‘cope’ was to stay off of social media, not because I didn’t want to be informed or because I didn’t care, but because it was so extremely overwhelming and concerning for me.” Several participant responses in this theme also expressed that social media was once a source of distraction and positive emotions prior to the flood of BLM-related posts. In addition, 5% of respondents described significant Decreased Functioning due to BLM coverage and social media posts. These participants described negative impacts to daily functioning which included staying inside out of fear of death or police brutality, appetite loss, and social isolation. Participants’ overall reports revealed that regardless of access to mental healthcare, a significant portion of people exposed to BLM posts were experiencing notable negative consequences related to mental health, social relationships, and daily functioning. When these codes were considered in the context of participants’ racial identity, a trend in responding emerged. Respondents who identified as Black endorsed decreases in functioning and increases in negative emotions more often than White participants (11.1% compared to 3.8%, and 51.9% versus 34.2% respectively). Further, there were slightly lower rates of self-reported disrupted relationships and withdrawing electronically in Black participants than White participants (18.5% versus 25.3%, and 18.5%–27.8% respectively).

Discussion

This study assessed how engagement with Black Lives Matter-related social media content was related to various mental health symptoms and how those relationships differed for participants identifying as racial minorities. The findings in large part support our hypothesis that greater engagement with social media posts related to BLM would be linked to worse mental health symptoms. The results reflected that greater engagement was related to more mental health symptoms --including anxiety, trauma-related, and schizotypy symptoms—across our two samples. Engagement was also related to depressive symptoms in the MTurk sample only. Against expectations, we found that the MTurk sample was more likely to engage with our vignettes than our SONA sample. Moderation results varied between our two samples, partially supporting our second hypothesis. For the SONA sample, racial minority status did not moderate the relationship between engagement and any mental health symptoms. However, in the MTurk sample, we found that racial minority status significantly moderated the relationships between engagement and both anxiety and trauma-related symptoms. Findings indicated that greater engagement was more strongly associated with worse mental health symptoms for participants who identified as racial minorities as compared to White participants. Additionally, the qualitative findings revealed that while a significant portion of participants reported negative psychological, behavioral, and social impacts linked to exposure to BLM-related social media content, most participants did not discuss BLM content or its impacts during their mental health treatment.

Moderation results revealed that MTurk participants identifying as racial minorities showed a stronger relationship between engagement with BLM-related social media posts and both anxiety and trauma-related symptoms. This finding is consistent with research that asserts racial minorities may be particularly affected by online engagement with race-based stressors (Carter & Kirkinis, 2021). BLM centers around conversations regarding the cycles of racial violence and the imminent threat of police brutality (Clayton, 2018; Ruffin, 2021). BLM-related discussions are, therefore, rife with instances of adversity and micro-aggressive rhetoric (Keiser, 2021); thus, they may facilitate stressors that are specifically race-based and particularly troubling for people identifying as racial minorities. As both anxiety and trauma-related symptoms are related to fear-based emotions, these comparatively stronger relationships may be linked to the personal relevance that BLM had for participants identifying as racial minorities. BLM is grounded in resisting the existential threat of brutality against Black bodies (Clayton, 2018; Ruffin, 2021), and confronting that threat, including through engagement with BLM-related social media posts, can be an emotionally taxing and fear-provoking experience. This idea is affirmed by a small number of qualitative responses wherein participants reported that they feared leaving their homes or interacting with police. While White participants still exhibited relationships between engagement with BLM content and mental health symptoms, there may not have been the same applicability to one’s life as there was for racial minority participants. This finding is particularly relevant to the growth of digital activism. With nearly half of Black social media users reporting using social media to engage with activism groups (Auxier, 2020), attention is needed to extend these findings and provide preventive services and resources to those who might be experiencing heightened symptoms.

Another significant finding from this study was that greater engagement with BLM-relevant social media posts was associated with higher levels of anxiety, schizotypy, and trauma-related symptoms across all participants regardless of race or sample. Further, greater engagement with BLM-related social media posts was related to greater depression in our SONA sample, but not our MTurk sample. Notably, we did not exclude participants who were unsupportive of BLM from our sample, thus results suggest that exposure to BLM-related content on social media, regardless of support for the movement or agreement with content in social media posts, may have negative impacts on mental health. There are several reasons why those who are against BLM may experience negative mental health outcomes after engaging with BLM-related content. Qualitative results provide one possible reason – that there has been much disagreement regarding BLM, in some cases leading to significant disruption of relationships, or even the loss of social supports. This issue is most certainly not particular to those on one side of the argument. Additionally, it is possible that negative mental health outcomes are linked more broadly to a sense of disillusionment or dissatisfaction with the state of the country, as has been found after other recent large-scale sociopolitical events (Campbell & Wolbrecht, 2020), which may equally affect participants with varying opinions about BLM. Future work is needed to investigate these possibilities.

Interestingly, qualitative findings revealed that participants were unlikely to discuss BLM with their mental health providers due, in part, to a belief that therapy was not an appropriate setting for these discussions. This was particularly concerning as some participants mentioned that BLM-related content on social media was distressing to them, and many reported increased negative emotions, disrupted relationships, and decreased functioning as a result of exposure to or engagement with BLM-related social media. The aversion to discussing BLM in therapy may reflect a broader hesitancy towards initiating discussions of sociopolitical relevance in certain contexts. This may be particularly hard to navigate in a therapeutic setting. However, of those participants who did discuss BLM with their therapist, no participant reported that the BLM-based discussions had a direct negative effect on the therapeutic relationship, though further qualitative work is needed to more extensively assess these relationships in Black clients, as only two of our participants who reported receiving mental health services during our timeframe identified as Black. Racial disparities in the mental healthcare system are notable and extend to college campuses (Cook et al., 2017; Lipson et al., 2018). As this question was only presented to participants who identified having received mental healthcare recently, the low proportion of Black respondents may be a manifestation of these disparities, in that Black respondents overall may have had less access to or ability to engage with mental healthcare services during the study timeframe. Future work is needed to assess whether clients who identify as racial minorities discuss BLM-related content in the therapeutic context and whether those conversations are beneficial to the client. Further, work must be done to ensure that both mental health providers and clients are aware of the importance of these conversations in a therapeutic setting, and that providers are trained in how to discuss activism and social justice content with their clients appropriately – and importantly, that these conversations are not couched within a particular point of view or political side. As one participant mentioned, an inappropriate political comment can be destructive to the therapeutic relationship.

Qualitative findings from the second question with a larger sample were better able to be contextualized with participants’ racial identities. Results indicated that Black participants more often endorsed decreased functioning and negative emotions related to BLM-related content than White participants. This is unsurprising, especially when considered alongside quantitative results suggesting that MTurk participants who identified as a racial minority had a stronger relationship between social media engagement and some mental health symptoms. Qualitative results also suggested that Black participants less often reported disrupted relationships and attempts to withdraw from electronic devices due to BLM-related content. White participants may have been more likely than Black participants to withdraw from social media to avoid content that may have led them to feel guilty or uncomfortable with privilege that they had not confronted previously. Further, for White participants, to engage or not engage with BLM-related content is likely seen as less personally relevant, and therefore it may be easier to withdraw or disconnect. This idea is supported by research which found that in order for supportive attitudes to arise, participants must not only use social media, but also be aware of privilege and social inequality (Lake et al., 2021). Additionally, past qualitative research has shown that White activism in a BLM context is largely centered around themes of public perceptions of their actions, such as fear of being perceived as racist or wanting to be involved in a public movement (Hughey, 2021). Future work should be done to assess the behaviors and emotions that happen in-the-moment while viewing such social media posts.

In addition to our main findings, differences between our MTurk and SONA samples warrant some discussion. The MTurk sample was significantly older and had a higher proportion of White participants. The MTurk sample was also the only sample in which moderation results were significant. Due to the 17-year age difference between our samples, our results may be highlighting a difference in how participants of different ages interact with social media. Our SONA sample was relatively young (M = 20.35, SD = 4.59), and the majority of this sample likely grew up with internet use and had exposure to social media from a young age. It may be that lifetime exposure to this sort of content online desensitized SONA participants to potentially upsetting posts, or, alternatively, that the volume of daily social media consumption makes each individual post less impactful. Future research should be done to assess if daily social media use or age have an impact on the relationship between engagement and symptom measures. Additionally, our MTurk sample was significantly more likely to engage with the vignettes than the SONA sample. This may be due, in part, to the nature of these samples’ participation. MTurk participants were being paid for their participation, indicating that their income at least partially relies upon their engagement online. Relatedly, previous research has shown that Mturk samples have higher internet fluency than the general population (Behrend et al., 2011). Taken together, these results suggest that Mturk samples may be more likely to engage with content that they see online, as well as being more likely to be affected by said content. By contrast, SONA system participants, who grew up with this technology, may view social media content more passively (seeing the post without engaging) due to a desensitization to online content. Yet, further research is needed to clarify these ideas.

It is important to note that while findings from the current study suggest that engagement with BLM-related social media content is linked to greater mental health symptoms; the literature also suggests that engagement in activism has been linked to positive outcomes. A recent study found that young adult activists engaged in social activism regardless of detriments to their mental well-being (Conner et al., 2021). Qualitative analyses from this study suggested that activists valued the importance of social connectedness, the feeling of having purpose, and shared care for others (Conner et al., 2021). This study explored the balance of positive and negative outcomes related to engagement in social activist movements and found that this engagement was of particular significance for those who experienced oppression such as racism (Conner et al., 2021). This showed that many individuals engaging in social activism, especially those belonging to groups directly affected by social issues, valued participation and continued engagement over the avoidance of possible negative impacts. This speaks to the idea that regardless of risk, people take benefits from and are likely to continue to be involved in social justice movements, so research on how to minimize the risks associated with engagement must be extended.

Our study has limitations. Notably, we had unequal representation of racial minority and non-minority participants in both samples; results should be replicated in samples with more equal distribution and from varying settings. Participants were not recruited from clinical settings, so our results may not generalize to individuals with clinical diagnoses. Further, data from the MTurk sample was lower quality than from the SONA sample. We aimed to improve data quality by excluding participants who did not meet our attention check criteria (answering less than 50% of attention check questions correctly or in the fastest 10% of response times). Nevertheless, future research should aim to replicate our findings. Relatedly, the MTurk qualitative responses were not able to be coded as there were consistent quality issues, so qualitative results are limited to undergraduate participants and thus have reduced generalizability. Importantly, we did not assess overall social media engagement, and thus were unable to parse apart whether engagement with social media posts might be related to mental health symptoms more broadly, as opposed to engagement specifically with BLM-related content. Additionally, lack of familiarity with social media or low social media use were not exclusion criteria. Lastly, it should be noted that SONA data was conducted in a small college town in southern Mississippi, so the geopolitical climate of the region may have influenced qualitative responses. More work is needed to investigate these relationships amongst participants from other backgrounds and settings. Further work should also be done to assess whether there are differences in mental health outcomes between those who merely consume social media content relevant to BLM and those who create social media content related to BLM.

Overall, findings suggest that engagement with BLM-related social media posts, one major avenue for social activism, may be relevant to mental health, especially for racial minorities, and that discussions of BLM were not common in appointments with mental healthcare providers. Future investigations into the intersection of these topics should replicate and extend these results to other groups and settings, including individuals with mental illnesses. Importantly, we did not assess in-person activism. Future work should assess whether those who engage more with in-person activism are less likely to be digital activists, or if the two forms are more likely to appear concurrently. It is also vital to assess the extent to which activism, both in-person and digitally, may have positive effects on an individual level, as well as how these potential positive effects may counteract the negative effects found in this study. Additionally, mixed methods studies should be done to assess the perspective of mental health providers, including their comfort level with addressing social media use and sociopolitical movements in therapy sessions. Lastly, research must be done to assess how we might be able to intervene to improve mental health outcomes for those engaging in digital activism, especially for those identifying as racial minorities, given heightened exposure to race-based stressors and moderation results presented here. More work is needed to better understand how these impacts can be prevented or treated, including by mental health providers.

Acknowledgement

Research reported in this article was funded by an Eagle Scholars Program for Undergraduate Research (SPUR) Award from the Drapeau Center for Undergraduate Research to Iyanna Marshall. Additional support was provided by the School of Psychology at the University of Southern Mississippi and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U54GM115428. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the National Institutes of Health or the United States Government.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project was funded by an Eagle Scholars Program for Undergraduate Research (SPUR) Award through the Drapeau Center for Undergraduate Research at the University of Southern Mississippi (USM). Additional support was provided by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U54GM115428 and by the School of Psychology at USM. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Biographies

Iyanna C. Marshall, BS earned her undergraduate degree in psychology from the University of Southern Mississippi in 2022. Her research interests are focused on community health disparities, racial stress, social behavior, and public health.

Kelsey A. Bonfils, PhD is an Assistant Professor in the Clinical Psychology PhD Program at the University of Southern Mississippi. She earned her PhD in clinical psychology from Indiana University-Purdue University, Indianapolis in 2018. Her research focuses on determinants of social cognition in people diagnosed with severe mental illnesses, particularly schizophrenia-spectrum disorders.

Cassi R. Springfield, MS is a doctoral student in the Clinical Psychology program at The University of Southern Mississippi. She earned her MS in psychological sciences at The University of Texas at Dallas. Her research interests include social cognitive impairment across the psychosis spectrum, the mechanisms underlying these deficits, and the associated functional outcomes.

Lillian A. Hammer, MPS is a doctoral student in the Clinical Psychology program at The University of Southern Mississippi. She earned her MPS in clinical psychological science at The University of Maryland, College Park. Her research interests include sleep and negative symptoms in people diagnosed with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders.

Appendix 1: Social Media Post Vignettes

Moderately Unsupportive (MU)

Why do we have to make everything about race? The police are here to serve and protect at the end of the day. There may be a few bad apples, but we shouldn’t abolish police as a whole. I think BLM is making this to be something it’s not, and the rioting and looting has to stop. There’s no proof that what happened in Minneapolis was racist.

I say that #AllLivesMatter. I don’t think we should single out black lives because there is not valid reason to believe that the police are killing based on race. People burning cities in the name of #Blacklives doesn’t seem right to me. Law enforcement is doing the best that they can, and BLM and Antifa damaging the property of local business owners has lost my respect. I have family in the force that I fear for with all of the chaos going on in our country.

Highly Unsupportive (HU)

Blue Lives Matter. I don’t care who this post upsets because I am sick of seeing people insult our heroes. People are saying to defund the police, but if they were getting robbed who are they gonna call? I think they are just taking our men and women in blue for granted, and I will not stand for the false narrative made by #BurnLootMurder and #Antifa. If you’re innocent, don’t resist. I have no sympathy for anyone dumb enough to make themselves look guiltier.

There is no racism in our honorable police force. That is a lie told by #BLM to tear apart our country. I think the police have done everything right and are trying to go home to their families at the end of the day. #BLM wants justice for criminals resisting arrest and endangering officers, but they won’t condemn looting and rioting and the destruction of American cities. So as a patriot, I say #BlueLivesMatter because what those rioters are doing is anything but good for our nation. Share if you agree #BlueLives #ThinBlueLine.

Moderately Supportive (MS)

It’s sad seeing so much division over the situation in Minneapolis. A man lost his life, and the first thing people are doing is making excuses for the officers rather than trying to understand why this is so upsetting for Black Americans. I won’t say that looting stores is okay, but I can’t see how anyone expects anything other than unrest in the face of yet another police killing of an unarmed Black man. I hope justice is served.

At first, I didn’t understand the necessity of #BlackLivesMatter, but after seeing the video of George Floyd, I get it. Something needs to change before more lives are lost. I don’t know if defunding or abolition are the right solutions, but I do know that these families and victims deserve better than the status quo. There are more than a few bad apples, it seems like this may actually be a bad system.

Highly Supportive (HS)

Black Lives Matter. I will keep saying it until this country proves it to be true. George Floyd like many before and after him have been reduced to a convenient narrative. He had a record or had drugs in his system or whatever they can come up with the make sure his life didn’t matter. Imagine tarnishing a victim’s name to justify their murder. Imagine being more upset about property damage than the loss of a human life.

Some people may not like this, but it has to be said. There needs to be some major unprecedented changes in law enforcement. I don’t want my tax dollars to go towards brutality and discrimination. I support defunding because this “justice” system has been lacking in justice. Black Lives Matter. I don’t want to see any “all lives matter” under this post because the deaths of George Floyd and many others have exposed that lie. These families deserve justice, and this violence justifies civil unrest. I don’t care if people riot. We have a right to fight for change.

Appendix 2: Qualitative Questions

Question 1: You reported that you have received mental health treatment at some point since March, 2020. In the space below, please indicate whether you spoke about the Black Lives Matter protests or the murder of George Floyd (or other related issues) with any mental health provider, and, if so, describe your experiences (e.g., was this discussion welcome? did it help you to process these events? did it have any impact on your relationship with your provider?). If you did not speak about these issues with your mental health provider(s), why not? Please aim to write at least 100 words.

Question 2: Social media posts about Black Lives Matter and the murder of George Floyd were frequently posted in the summer of 2020. Please describe the impact of these posts on your functioning (i.e., ability to do your job, go to school, maintain relationships, etc.) and/or your mental health. If you were negatively impacted, please describe what strategies you used to cope with those impacts. Please aim to write at least 100 words.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Aalbers G, McNally RJ, Heeren A, De Wit S, & Fried EI (2019). Social media and depression symptoms: A network perspective. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 148(8), 1454–1462. 10.1037/xge0000528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfasi Y (2019). The grass is always greener on my Friends’ profiles: The effect of Facebook social comparison on state self-esteem and depression. Personality and Individual Differences, 147, 111–117. 10.1016/j.paid.2019.04.032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M, Barthel M, Perrin A, & Vogels E (2020). #Black lives matter surges on twitter after George Floyd’s death. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/06/10/blacklivesmatter-surges-on-twitter-after-george-floyds-death/ [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M, Toor S, Rainie L, & Smith A (2018). Activism in the social media age. Science & Tech. Pew Research Center: Internet. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2018/07/11/activism-in-the-social-media-age/ [Google Scholar]

- Auxier B (2020). Activism on social media varies by race and ethnicity, age, political party. Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Auxier B, & Anderson M (2021). Social media use in 2021. Pew Research Center, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Behrend TS, Sharek DJ, Meade AW, & Wiebe EN (2011). The viability of crowd-sourcing for survey research. Behavior Research Methods, 43(3), 800–813. 10.3758/s13428-011-0081-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, & Domino JL (2015). The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(6), 489–498. 10.1002/jts.22059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenman M, & Sanchez TW (2014). Social activism. In Michalos AC (Ed.), Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research (pp. 6012–6017). Springer; Netherlands. 10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_2729 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DE, & Wolbrecht C (2020). The resistance as role model: Disillusionment and protest among american adolescents after 2016. Political Behavior, 42(4), 1143–1168. 10.1007/s11109-019-09537-w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter RT, & Kirkinis K (2021). Differences in emotional responses to race-based trauma among black and white americans. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment and Trauma, 30(7), 889–906. 10.1080/10926771.2020.1759745 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton DM (2018). Black lives matter and the civil rights movement: A comparative analysis of two social movements in the United States. Journal of Black Studies, 49(5), 448–480. 10.1177/0021934718764099 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AS, Matthews RA, Najolia GM, & Brown LA (2010). Toward a more psychometrically sound brief measure of schizotypal traits: Introducing the SPQ-Brief Revised. Journal of Personality Disorders, 24(4), 516–537. 10.1521/pedi.2010.24.4.516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner JO, Crawford E, & Galioto M (2021). The mental health effects of student activism: Persisting despite psychological costs. Journal of Adolescent Research, 38, 1–30. 10.1177/07435584211006789 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cook BL, Trinh NH, Li Z, Hou SSY, & Progovac AM (2017). Trends in racial-ethnic disparities in access to mental health care, 2004–2012. Psychiatric Services, 68(1), 9–16. 10.1176/appi.ps.201500453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crethar HC, & Ratts MJ (2008). Why social justice is a counseling concern. Counseling Today, 50(12), 24–25. [Google Scholar]

- Eschmann R, Groshek J, Chanderdatt R, Chang K, & Whyte M (2020). Making a microaggression: Using big data and qualitative analysis to map the reproduction and disruption of microaggressions through social media. Social Media+ Society, 6(4), 2056305120975716. 10.1177/2056305120975716 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- First JM, Danforth L, Frisby CM, Warner BR, Ferguson MW Jr., & Houston JB (2020). Posttraumatic stress related to the killing of Michael brown and resulting civil unrest in Ferguson, Missouri: Roles of protest engagement, media use, race, and resilience. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 11(3), 369–391. 10.1086/711162 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- George JJ, & Leidner DE (2019). From clicktivism to hacktivism: Understanding digital activism. Information and Organization, 29(3), 100249. 10.1016/j.infoandorg.2019.04.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harold C, & DeLuca KM (2005). Behold the corpse: Violent images and the case of Emmett till. Rhetoric & Public Affairs, 8(2), 263–286. 10.1353/rap.2005.0075 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hisam A, Safoor I, Khurshid N, Aslam A, Zaid F, & Muzaffar A (2017). Is political activism on social media an initiator of psychological stress? Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 33(6), 1463–1467. 10.12669/pjms.336.12863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF, & Shannon SE (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughey MW (2021). How blackness matters in White lives. Symbolic Interaction, 44(2), 412–448. 10.1002/symb.552 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keiser J (2021). The “all lives matter” response: QUD-shifting as epistemic injustice. Synthese,199(3), 8465–8483. 10.1007/s11229-021-03171-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kondracki NL, Wellman NS, & Amundson DR (2002). Content analysis: Review of methods and their applications in nutrition education. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 34(4), 224–230. 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60097-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, & Williams JB (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Berry JT, & Mokdad AH (2009). The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. Journal of Affective Disorders, 114(1–3), 163–173. 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lake JS, Alston AT, & Kahn KB (2021). How social networking use and beliefs about inequality affect engagement with racial justice movements. Race and Justice, 11(4), 500–519. 10.1177/2153368718809833 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lipson SK, Kern A, Eisenberg D, & Breland-Noble AM (2018). Mental health disparities among college students of color. Journal of Adolescent Health, 63(3), 348–356. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays N, & Pope C (2000). Assessing quality in qualitative research. Bmj, 320(7226), 50–52. 10.1136/bmj.320.7226.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy KS, & Saks JV (2019). Postelection stress: Symptoms, relationships, and counseling service utilization in clients before and after the 2016 US national election. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 66(6), 726–735. 10.1037/cou0000378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody AT, & Lewis JA (2019). Gendered racial microaggressions and traumatic stress symptoms among Black women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 43(2), 201–214. 10.1177/0361684319828288 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pagoto S, Waring ME, & Xu R (2019). A call for a public health agenda for social media research. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(12), e16661. 10.2196/16661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransby B (2018). Making all black lives matter: Reimagining freedom in the twenty-first century (1st ed.). University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ruffin HG (2021). Working together to survive and thrive: The struggle for Black lives past and present. Leadership, 17(1), 32–46. 10.1177/1742715020976200 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santos CE, & VanDaalen RA (2018). Associations among psychological distress, high-risk activism, and conflict between ethnic-racial and sexual minority identities in lesbian, gay, bisexual racial/ethnic minority adults. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 65(2), 194–203. 10.1037/cou0000241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott K, Ma DS, Sadler MS, & Correll J (2017). A social scientific approach toward understanding racial disparities in police shooting: Data from the Department of Justice (1980–2000). Journal of Social Issues, 73(4), 701–722. 10.1111/josi.12243 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, & Löwe B (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stosny S (2017). How to cope with Trump anxiety | psychology today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/anger-in-the-age-entitlement/201704/how-cope-trump-anxiety

- Sue DW (2010). Microaggressions, marginality, and oppression: An introduction.

- Torres Rivera E, & Comas-Díaz L (2020). Introduction Liberation psychology: Theory, method, practice, and social justice (3–13). 10.1037/0000198-001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijcke D, & Wright AL (2020). Using mobile device traces to improve near-real time data collection during the George Floyd protests. Available at SSRN; 3621731. [Google Scholar]

- Vromen A, Xenos MA, & Loader B (2015). Young people, social media and connective action: From organisational maintenance to everyday political talk. Journal of Youth Studies, 18(1), 80–100. 10.1080/13676261.2014.933198 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams MT (2020). Psychology cannot afford to ignore the many harms caused by microaggressions. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(1), 38–43. 10.1177/1745691619893362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]