In our previous discussion, Part 1- Sensitivity and Specificity, we reviewed how to interpret sensitivity and specificity as a measure of the reliability of screening and diagnostic tests relative to a gold standard test [1]. The second part of this discussion will examine how to use positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) as the next step in interpreting the quality of screening/diagnostic tests (i.e., how to apply these concepts in clinical scenarios where specificity and sensitivity alone are insufficient). It is important to note that while sensitivity and specificity assess the adequacy of the test itself, in contrast, PPV and NPV measure the test’s ability to properly categorize patients as having, or not having, a specific disease [2]. In other words, PPV and NPV determine the probability that a patient (i.e., assess the person) has or does not have a specific disease [2]. Consequently, PPV and NPV usually have greater clinical implications compared to sensitivity and specificity.

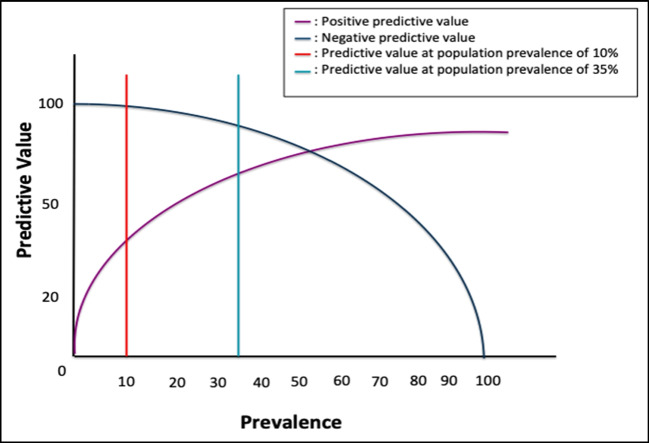

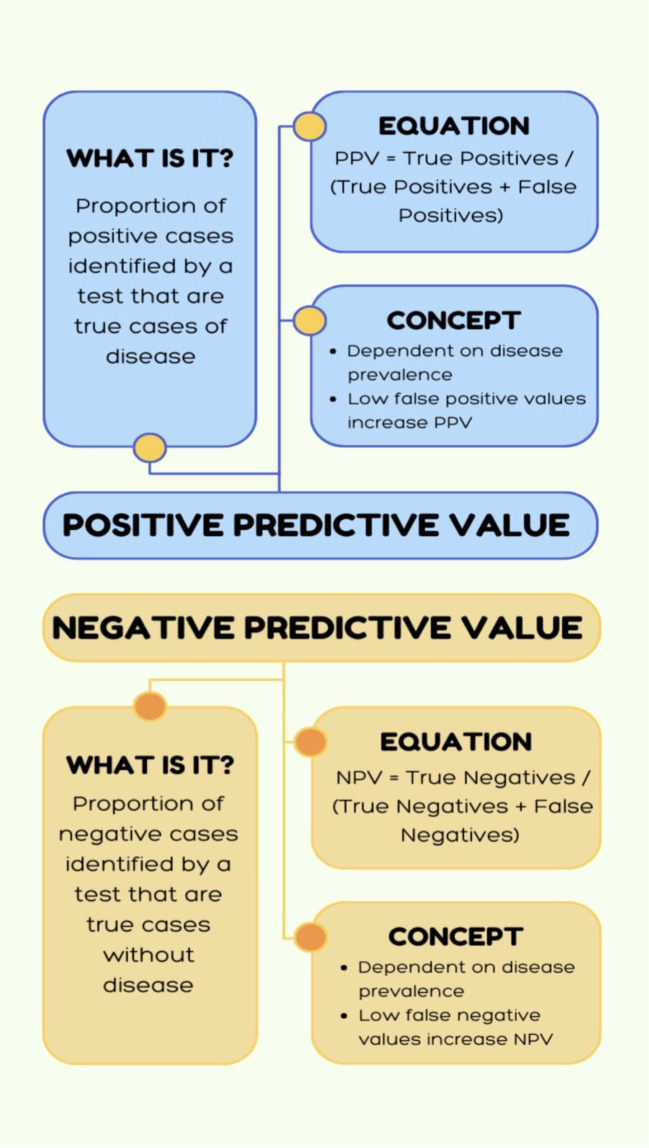

The positive predictive value (PPV) is defined as the proportion of positive cases identified by a test that are true cases with disease. For a test to have a high PPV, the true positives in the numerator must be high and the false positives in the denominator must be low. Similarly, the negative predictive value (NPV) is defined as the proportion of negative cases identified by a test that are true cases without disease. For a test to have a high NPV, the true negatives in the numerator must be high and the the false negatives in the denominator must be low (See Table 1). Another important factor in understanding these two concepts is that PPV and NPV vary depending on disease prevalence, whereas sensitivity and specificity are independent of disease prevalence. Disease prevalence (i.e., True Prevalence) is defined as the number of diseased cases divided by the total number of cases (See Table 1). As the disease prevalence increases, a test is more useful for ruling in the disease because there are going to be fewer false positives in the denominator; vice versa, when the disease prevalence is low, there are going to be more false positives in the denominator decreasing the diagnostic performance of the test (See Fig. 1). Furthermore, one should understand that disease prevalence can also be referred to as the pre-test probability; PPV and NPV vary with changes in pre-test probability. Consequently, if additional risk factors for a specific disease are also taken into consideration for a specific disease (e.g., sex, age, etc.), this additional information can increase the pre-test probability of disease and therefore improve the test’s ability to predict the presence of disease (i.e., increase the PPV). Ultimately, the goal is to select the “right” population to study in order to obtain the best performance for a specific diagnostic test.

Table 1.

Mathematical formulas to calculate sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, accuracy, and true prevalence.

| Diseased | Not Diseased | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Test |

True Positive (TP) |

False Positive (FP) |

PPV (TP/TP + FP) |

| Negative Test |

False Negative (FN) |

True Negative (TN) |

NPV (TN/TN + FN) |

|

Sensitivity (TP/TP + FN) |

Specificity (TN/TN + FP) |

Accuracy (TP + TN) / (TP + FN + FP + TN) |

|

| True Prevalence | (TP + FN) / (TP + FN + FP + TN) | ||

Fig. 1.

Relationship between prevalence and predictive values. As the prevalence of a disease increases, the positive predictive value (PPV) increases and the negative predictive value (NPV) decreases.

One other all-encompassing term that is relevant to this discussion, but less commonly mentioned, is the accuracy of a diagnostic test. Accuracy is calculated by summing the true positives and true negatives, then dividing by the number of total positives (true and false) and total negatives (true and false). Put another way, accuracy is the mathematical formula for identifying the proportion of correctly classified cases among all the cases [1]. Please see Table 1 for a summary of these calculations.

In Part 1- Sensitivity and Specificity, we use the following illustrative example of an acute acetaminophen (APAP) overdose: If a patient takes an acute APAP overdose and has a blood APAP concentration > 150 μg/mL at 4 h, we consider this to be a positive diagnostic test for acetaminophen toxicity; if a patient takes an acute APAP overdose but has a blood APAP concentration < 150 μg/mL at 4 h, we consider this to be a negative diagnostic test for APAP toxicity. We then create a hypothetical study examining the role of a fictional point of care test (“POCT”) that measures APAP concentrations based on capillary specimens. The POCT uses a drop of blood to provide a colorimetric result that determines whether the APAP concentration is “high” (i.e., > 150 μg/mL). Researchers then do a prospective cohort study of 1000 acute overdose patients presenting to the hospital with suspected APAP toxicity to determine the test characteristics of the POCT. Based on the definition of a blood APAP concentration of > 150 μg/mL at 4 h following ingestion, they determine that the prevalence of APAP toxicity is 6%. The prevalence is therefore 60 true cases of APAP toxicity. They then assess the test characteristics of the POCT to diagnose acute APAP toxicity and find the following results (See Table 2a).

Table 2a.

Test results in population with prevalence of 6%

| Diseased (APAP +) | Not Diseased (APAP-) | Totals | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POCT ( +) | 30 (TP) | 300 (FP) | 330 | PPV: 9% |

| POCT (-) | 30 (FN) | 640 (TN) | 670 | NPV: 96% |

| 60 | 940 | 1000 | ||

| Sensitivity: 50% | Specificity: 68% | Accuracy 67% |

The test characteristics of the POCT in diagnosing acute APAP toxicity when the disease prevalence is 6%. TP true positive, TN true negative, FP false positive, FN false negative, PPV positive predictive value, NPV negative predictive value

Utilizing the table above,

To calculate Sensitivity:

To calculate Specificity:

To calculate PPV:

To calculate NPV:

Based on these results, the positive predictive value and negative predictive values are calculated to be 9% and 96%, respectively. This means that in a population with an APAP toxicity prevalence of 6% the probability of APAP toxicity with a positive POCT APAP concentration (> 150 μg/mL) is 9%. Conversely, in a population with this same prevalence, we expect 96% of cases with a negative POCT APAP concentration (< 150 μg/mL) to not have APAP toxicity.

Now when the researchers repeat the study in a different population of patients that has a lower prevalence (1%) of APAP toxicity, the test characteristics of the POCT to diagnose acute APAP with respect to sensitivity and specificity do not change but the PPV and NPV do (See Table 2b).

Table 2b.

Test results in population with prevalence of 1%

| Diseased (APAP +) | Not Diseased (APAP-) | Totals | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POCT ( +) | 5 (TP) | 317 (FP) | 322 | PPV: 2% |

| POCT (-) | 5 (FN) | 673 (TN) | 678 | NPV: 99% |

| 10 | 990 | 1000 | ||

| Sensitivity: 50% | Specificity: 68% | Accuracy: 68% |

The test characteristics of the POCT in diagnosing acute APAP toxicity when the disease prevalence is 1%. TP true positive, TN true negative, FP false positive, FN false negative, PPV positive predictive value, NPV negative predictive value

Utilizing the table above,

To calculate Sensitivity:

To calculate Specificity:

To calculate PPV:

To calculate NPV:

Based on these results, the positive predictive value and negative predictive values are calculated to be 2% and 99%, respectively. So, in a population with an APAP toxicity prevalence of 1% the probability of APAP toxicity with a positive POCT APAP concentration (> 150 μg/mL) is 2%. In a population with this same prevalence, we expect 99% of cases with a negative POCT APAP concentration (< 150 μg/mL) to not have APAP toxicity.

As can be seen here, although the disease prevalence changes, the sensitivity and specificity remain the same. These examples also further demonstrate that when the disease prevalence decreases, the PPV also decreases but, in contrast, the NPV increases (and the directionality for both PPV and NPV will change in the other direction if the disease prevalence increases). The explanation for the changes in PPV and NPV based on disease prevalence are that, mathematically, as the prevalence decreases, there will be more true negatives for every false negative; this leads to an increase numerator relative to denominator (i.e., an increase in NPV). Furthermore, it should be evident that, conversely, PPV and NPV will increase and decrease, respectively, if the disease prevalence increases. As mentioned already, for most diagnostic tests, sensitivity and specificity of the diagnostic test remain the same regardless of disease prevalence. We can see from the APAP toxicity example demonstrated above that when the prevalence of APAP toxicity in the population decreased, there were no changes to the sensitivity and specificity. However, the PPV decreased and the NPV subsequently increased.

In summary, the test characteristics of a test are defined by the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV. Understanding the test characteristics of a test is critical to determine whether a test is useful and, if the test characteristics are favorable, can significantly impact patient care diagnostically and therapeutically.

Key Learning Points

Positive predictive value (PPV) is defined as the proportion of positive cases identified by a test that are true cases of disease.

Negative predictive value (NPV) is defined as the proportion of negative cases identified by a test that are true cases without disease.

Sensitivity and specificity do not vary with disease prevalence; however, positive and negative predictive value are affected by disease prevalence.

Sources of Funding

None.

Declarations

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sahagún BE, Williams C, Su MK. Biostatistics and Epidemiology Principles for the Toxicologist: The "Testy" Test Characteristics Part I-Sensitivity and Specificity. J Med Toxicol. 2023;19(1):40–44. 10.1007/s13181-022-00916-0. Erratum in: J Med Toxicol. 2022 Dec 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Trevethan R. Sensitivity, Specificity, and Predictive Values: Foundations, Pliabilities, and Pitfalls in Research and Practice. Front Public Health. 2017;20(5):307. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]