Abstract

Background

Notwithstanding recent advances in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) management, its mortality rate is still high. It is imperative to investigate new parameters that are complementary to clinical staging for OSCC to provide better prognostic insight. The presence of isolated neoplastic cells or small clusters of up to four cells at the tumor’s invasive front, called tumor budding, is a morphological marker of OSCC with prognostic value. Increased lymphatic vascular density (LVD) and a high expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells have also been associated with worse prognosis in OSCC. To investigate these markers in OSCC, we evaluated differences in LVD and the expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells between tumors with high-intensity tumor budding versus low-intensity or no tumor budding. In the samples of high-intensity budding, differences in those parameters between the budding area and the area outside the budding were also evaluated. Furthermore, the study assessed differences in LVD and in the expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells concerning OSCC clinicopathological characteristics.

Methods

To those ends, we subjected 150 samples of OSCC to immunohistochemistry to evaluate the intensity of tumor budding (via multi-cytokeratin immunostaining). Moreover, the 150 samples of OSCC and 15 specimens of normal oral mucosa (used as a control) were employed to assess LVD and the expression of podoplanin (in neoplastic cells of OSCC and in the lining epithelium of normal oral mucosa), both via podoplanin immunostaining. Data were processed into descriptive and analytical statistics.

Results

No differences were observed neither in the LVD nor in the expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells concerning sex, age, tobacco smoking, tumor location and tumor size. The LVD was greater in OSCC and in tumors with high-intensity budding than in normal mucosa but did not differ between normal mucosa and tumors with low-intensity or no tumor budding. The data analyses also revealed that LVD was greater in tumors with high-intensity tumor budding than in tumors with low-intensity or no budding and showed no difference in LVD between the budding area and the area outside the budding. When compared to the lining epithelium of the normal mucosa, the expression of podoplanin was greater in neoplastic cells of OSCC, tumors with high-intensity budding and tumors with low-intensity or no tumor budding. The expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells was also greater in tumors with high-intensity budding and, within those tumors, greater in the budding area than in the area outside de budding.

Conclusion

Those findings support the hypothesis that tumor budding is a biological phenomenon associated with the progression and biological behavior of OSCC.

Keywords: Tumor budding, Oral squamous cell carcinoma, Lymphatic vascular density, Lymphangiogenesis, Podoplanin

Introduction

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is the most common malignant tumor of the head and neck (not considering nonmelanoma skin cancer) and its prognosis is conventionally associated to tumor stage by TNM Classification [1]. Notwithstanding recent advances in OSCC management, its mortality rate is still high, showing a survival rate of aproximately 65% in 5 years [2].

It is imperative to investigate new parameters that are complementary to clinical staging for OSCC to provide better prognostic insight in more reliable, consistent ways. Tumor budding has been identified as an independent prognostic factor in malignant epithelial neoplasms from different locations, especially in OSCC and in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Tumor budding is characterized by the presence of isolated neoplastic cells or small clusters of up to four cells at the tumor’s invasive front. This morphological phenomenon represents multiple properties of malignancy, especially loss of cell adhesion and active invasive movement, in addition to being related to the epithelial–mesenchymal transition, an important phenomenon for the local invasion and metastasis of malignant tumors [2–7].

Lymphangiogenesis is the formation of new lymphatic vessels via the proliferation and migration of endothelial cells from pre-existing lymphatic vessels by way of several mechanisms of induction [8, 9]. The process can be evaluated by measuring lymphatic vascular density (LVD) using immunohistochemistry with the antibody D2-40 (i.e., anti-podoplanin), which is widely used as a specific marker of lymphatic vessels in research on tumor lymphangiogenesis [10–17]. To date, studies have shown that higher LVD in OSCC is associated with a greater occurrence of regional metastases and a lower survival rate [10, 16, 17].

Although often found on the surface of certain normal cells and in the endothelium of lymph vessels, the protein podoplanin can also be expressed by cancer cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) [18]. Elevated levels of podoplanin have been observed in several types of human carcinomas, especially in squamous cell carcinoma. Studies have revealed that the high expression of podoplanin in tumors, including OSCC, may relate to tumor progression, local invasion, and metastasis and, in turn, be associated with a lower survival time for patients [18–22].

Against that background, we aimed to evaluate differences in LVD and the expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells between tumors with high-intensity tumor budding versus low-intensity or no tumor budding in cases of OSCC. In samples of high-intensity budding, differences in those parameters between the budding area and the area outside the budding were evaluated as well. Furthermore, we assessed differences in LVD and in the expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells concerning OSCC clinicopathological characteristics.

Materials and Methods

Sample Selection

Once the study was approved by by the Institutional Review Board at Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Minas Gerais—PUC Minas (CAAE 74605417.0.0000.5137), 260 samples of OSCC in the Oral Pathology Laboratory at the PUC Minas School of Dentistry were initially evaluated. Those samples were previously obtained by incisional diagnostic biopsies, fixed in formalin, and embedded in paraffin. After that preliminary evaluation, 110 samples were excluded due to a scarcity of tumor parenchyma, because tumor stroma were too scarce to adequately assess LVD, or because material could not provide new histological sections. Consequently, the final sample contained 150 specimens.

Moreover, 15 samples of normal oral mucosa were used as a control, representing the regions of origin for the evaluated tumors. These 15 specimens of normal oral mucosa were present in the material collected in 15 of the 150 OSCC samples evaluated in the study. All the 15 selected normal oral mucosa specimens showed: (1) microscopic morphological features of normality both in the lining epithelium and in the lamina propria; (2) no presence of epithelial dysplasia or malignant tumor infiltration.

Clinicopathological Characteristics

Clinicopathological data of the 150 OSCC cases concerning sex, age, tobacco smoking, tumor location and tumor size were acquired from the Anatomic Pathology Requisition Form. Sex data were accessible in 150 cases, age data in 143 cases, tobacco smoking data in 106 cases, tumor location data in 150 cases and tumor size data in 120 cases.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry techniques were used to detect multi-cytokeratin, namely to evaluate tumor budding by detecting neoplastic epithelial cells, and podoplanin, namely to evaluate either LVD or the expression of podoplanin (in the lining epithelium of normal oral mucosa samples and in neoplastic cells of OSCC samples). Antigen retrieval was performed with Trilogy (Cell Marque, Rocklin, CA, USA), and the primary antibodies employed were anti-multi-cytokeratin (cocktail of clones AE1 and AE3, diluted 1:50; Leica Biosystems, Newcastle, UK) and anti-podoplanin (clone D2-40, diluted 1: 150; Medaysis, Livermore, CA, USA). The amplification system used was the Reveal Biotin-Free system (Spring Bioscience, Pleasanton, CA, USA). Samples of fibrous hyperplasia of the oral mucosa were chosen as positive controls (for either multi-cytokeratin or podoplanin). Omission of the primary antibodies and the use of monoclonal antibodies with the identical isotype but showing different specificities of the primary antibodies were adopted as negative controls.

Evaluation of Tumor Budding Intensity

An experienced examiner (MCRH) evaluated tumor budding intensity, using an Olympus BX51 optical microscope with 10× ocular lens and field number 22 (Olympus Optical Co., Tokyo, Japan), in samples submitted for multi-cytokeratin immunostaining, which was used to identify OSCC cells, as recommended by Leão et al. [23] and following the criteria of Wang et al. [5].

Tumor budding, defined as the presence of isolated neoplastic cells or small clusters of up to four cells at the tumor’s invasive front, was assessed in a single 200× power field. The specimens were first assessed using the objective lens with the lowest power of magnification to detect areas with the highest-intensity tumor budding. Afterward, using a 20× objective lens, the number of isolated neoplastic cells or small clusters of up to four cells (i.e., tumor buds) was calculated in only one 200× power field (i.e., the field with the most tumor buds). Specimens of OSCC were subsequently categorized as having either high-intensity tumor budding (i.e., samples showing five or more tumor buds in the evaluated 200× power field, Fig. 1) or low-intensity or no tumor budding (i.e., samples showing fewer than five or no tumor buds in the evaluated 200× power field).

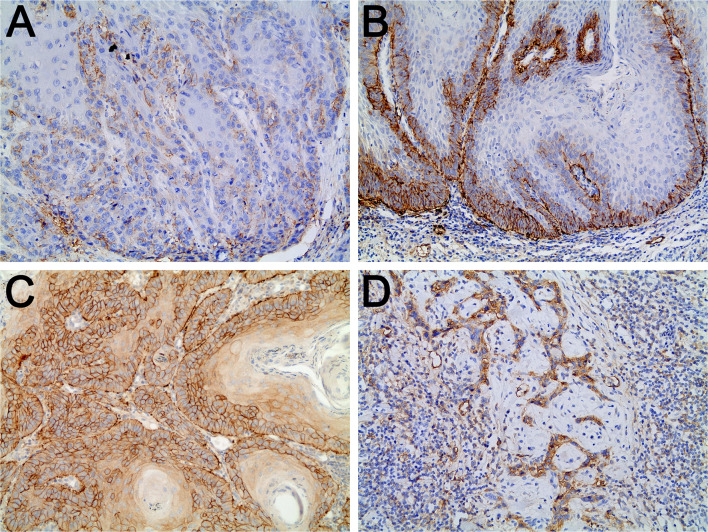

Fig. 1.

A High-intensity tumor budding in in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) (multi-cytokeratin immunostaining, 200×). B Lymphatic microvessels immunostained for podoplanin in OSCC with low-intensity or no tumor budding (podoplanin immunostaining, 200×). C Lymphatic microvessels immunostained for podoplanin in the budding area of an OSCC with high-intensity tumor budding (podoplanin immunostaining, 200×). D Lymphatic microvessels immunostained for podoplanin in the area outside the tumor budding in OSCC showing high-intensity tumor budding (podoplanin immunostaining, 200×). Note: The expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells was also observed in B, C, and D

Cohen’s kappa was employed to calculate intraexaminer agreement. First, the examiner estimated the intensity of tumor budding in 40 samples at two times: T1 (i.e., initial evaluation) and T2 (i.e., 30 days after T1). The kappa value obtained, 0.95 (95% CI 0.85–1.04), indicated excellent agreement according to Cicchetti and Sparrow’s criteria [24]. Concordance analysis was performed in the StatsToDo statistical program available at www.statstodo.com (StatsToDo Trading Pty Ltd, Brisbane, QLD, Australia).

Evaluation of LVD

The evaluation of LVD was performed by an experienced examiner (EMA) in specimens submitted to podoplanin immunostaining. ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) was used to analyze images captured by a digital camera attached to an Olympus BX51 optical microscope (Olympus Optical Co., Tokyo, Japan).

In samples of normal oral mucosa, LVD was assessed in a single 200× power field with the highest LVD in the lamina propria. In samples of OSCC showing high-intensity tumor budding, LVD was evaluated in two independent areas: the tumor budding area (i.e., in a single 200× power field with the highest–intensity tumor budding) and the area outside the tumor budding (i.e., in a single 200× power field, outside the tumor budding area, showing the highest LVD). In samples showing low-intensity or no tumor budding, LVD was assessed in a single 200× power field with the highest LVD.

We considered the following to constitute one countable lymphatic microvessel: a vessel lumen lined by an immunostained endothelium, an immunostained endothelial cell, or a cluster of immunostained endothelial cells entirely separated from adjacent clusters. Visible lumen was not a criterion for defining a countable microvessel [25, 26]. Subsequently, LVD was calculated as number of lymphatic microvessels in a 200× power field.

The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was used to calculate intraexaminer agreement in the evaluation of LVD. First, the examiner estimated the LVD in 50 samples at two times: T1 (i.e., initial evaluation) and T2 (i.e., 30 days after T1). The value obtained, 0.93, indicated excellent agreement according to Cicchetti and Sparrow’s criteria [24]. Concordance analysis was performed in the StatsToDo statistical program available at www.statstodo.com (StatsToDo Trading Pty Ltd, Brisbane, QLD, Australia).

Evaluation of the Expression of Podoplanin

The evaluation of the expression of podoplanin (in the lining epithelium of normal oral mucosa samples and in neoplastic cells of OSCC samples) was performed by an experienced examiner (EMA), in specimens submitted to podoplanin immunostaining. The ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA) was used to analyze images captured by a digital camera attached to an Olympus BX51 optical microscope (Olympus Optical Co., Tokyo, Japan).

In samples of normal oral mucosa, the expression of podoplanin in the lining epithelium was assessed in a single 200× power field with the highest expression of podoplanin. In samples of OSCC showing high-intensity tumor budding, the expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells was evaluated in two independent areas: the tumor budding area (i.e., in a single 200× power field with the highest-intensity tumor budding) and the area outside the tumor budding (i.e., in a single 200× power field, outside the tumor budding area, showing the highest expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells). In samples showing low-intensity or no tumor budding, the expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells was assessed in a single 200× power field with the highest expression of podoplanin.

In evaluating the expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells of OSCC, we considered the percentage of neoplastic cells immunostained for podoplanin regardless of immunostaining intensity, for scores following the criteria established by De Sousa et al. [27], in which scores of 0 indicate no positive cells, scores of 1 indicate less than 50% of positive cells, scores of 2 indicate 50–75% of positive cells, and scores of 3 indicate more than 75% of positive cells (Fig. 2). Afterward, for statistical analysis, the samples were categorized as either negative (i.e., with scores of 0 and 1) or positive (i.e., with scores of 2 and 3). The same criteria were used in evaluating the expression of podoplanin in the lining epithelium of normal oral mucosa samples.

Fig. 2.

A and B Expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC); score 1: less than 50% positive cells (podoplanin immunostaining; A 200×; B 200×). C and D Expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells of OSCC; score 3: more than 75% positive cells (podoplanin immunostaining; C 200×; D 200×). Note: For statistical analysis, the samples were categorized as negative (i.e., scores of 0 and 1) and positive (i.e., scores of 2 and 3)

Cohen’s kappa was employed to calculate intraexaminer agreement in the evaluation of podoplanin’s expression in neoplastic cells. First, the examiner estimated the expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells in 50 samples at two times: T1 (i.e., initial evaluation) and T2 (i.e., 30 days after T1). The kappa value obtained, 0.84 (95% CI 0.73–0.95), indicated excellent agreement according to Cicchetti and Sparrow’s criteria [24]. Concordance analysis was performed in the StatsToDo statistical program available at www.statstodo.com (StatsToDo Trading Pty Ltd, Brisbane, QLD, Australia).

Statistical Analysis

The D’Agostino–Pearson normality test confirmed a non-normal distribution in the LVD data.

The Mann–Whitney test was used to evaluate differences in the LVD concerning the clinicopathological characteristics sex and age. The Kruskal–Wallis test followed by the Dunn’s multiple comparisons test was used to evaluate differences in the LVD concerning the clinicopathological characteristics tobacco smoking, tumor location and tumor size. The Fisher’s exact test was used to evaluate differences in the expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells concerning the clinicopathological characteristics sex and age. The Chi-square test was used to evaluate differences in the expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells concerning the clinicopathological characteristics tobacco smoking, tumor location and tumor size.

The Mann–Whitney test and Fisher’s exact test were used to assess differences in LVD and differences in the expression of podoplanin, respectively, between: normal oral mucosa versus OSCC; normal oral mucosa versus OSCC with low-intensity or no tumor budding; normal oral mucosa versus OSCC with high-intensity tumor budding; OSCC with high-intensity tumor budding versus OSCC with low-intensity or no tumor budding. In OSCC with high-intensity budding, the Wilcoxon test and McNemar’s test were also performed to assess differences in LVD and differences in the expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells, also respectively, between the budding area and the area outside the budding.

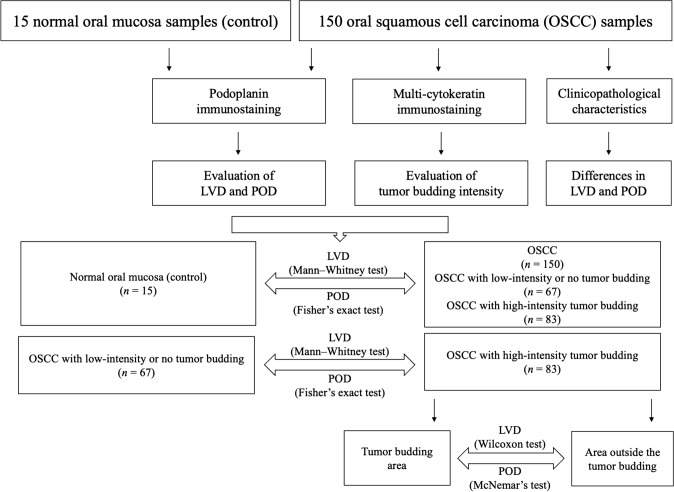

The level of significance was set at 5%. Analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism software (San Diego, CA, USA). Figure 3 illustrates the study design and the statistical analyses.

Fig. 3.

Study design and statistical analyses. OSCC oral squamous cell carcinoma, LVD lymphatic vascular density, POD podoplanin expression in the lining epithelium of normal oral mucosa or in neoplastic cells of OSCC

Results

The clinicopathological characteristics of the 150 evaluated OSCC cases, such as sex, age, tobacco smoking, tumor location and tumor size are shown in Table 1. Sex data were accessible in 150 cases, showing 116 men (77.3%) and 34 women (22.7%). Regarding age, data accessible in 143 cases, the mean and standart deviation were 58.90 ± 13.14 years (ranging from 30 to 94 years). Concerning tobacco smoking (data accessible in 106 cases), 61 (57.5%) patients were current smokers, 23 (21.7%) former smokers and 22 (20.8%) never smokers. As regards to anatomical location (data accessible in 150 cases), the following features were observed: tongue (n = 64; 42.7%); floor of the mouth (n = 24; 16.0%); alveolar ridge (n = 19; 12.7%); lip (n = 17; 11.3%); other locations (n = 26; 17.3%). Lastly, data concerning the tumor size was available in 120 cases, as follows: ≤ 2 cm (n = 54; 45%); > 2 and ≤ 4 cm (n = 43; 35.8%); > 4 cm (n = 23; 19.2%).

Table 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics of the oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) cases and evaluation of differences in the lymphatic vascular density (LVD) and in the expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells (both assessed via podoplanin immunostaining), concerning sex, age, tobacco smoking, tumor location and tumor size

| Parameter | n | % | LVD median (min.–max.) |

Podoplanin in neoplastic cells | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative (n) | Positive (n) | ||||

|

Sex (n = 150) |

|||||

| Male | 116 | 77.3% | 8.00 (1.00–26.00) | 20 | 96 |

| Female | 34 | 22.7% | 9.00 (3.00–26.00) | 2 | 32 |

| p value | 0.15a | 0.16b | |||

|

Age (years) (n = 143) |

|||||

| < 60 | 80 | 55.9% | 9.00 (3.00–24.00) | 13 | 67 |

| ≥ 60 | 63 | 44.1% | 8.00 (1.00–26.00) | 9 | 54 |

| p value | 0.11a | 0.81b | |||

|

Tobacco smoking (n = 106) |

|||||

| Current | 61 | 57.5% | 9.00 (3.00–21.00) | 8 | 53 |

| Former | 23 | 21.7% | 8.00 (1.00–25.00) | 2 | 21 |

| Never | 22 | 20.8% | 9.00 (4.00–26.00) | 0 | 22 |

| p value | 0.18c | 0.19d | |||

|

Tumor locatione (n = 150) |

|||||

| Tongue | 64 | 42.7% | 9.00 (2.00–26.00) | 8 | 56 |

| Floor of the mouth | 24 | 16.0% | 8.50 (4.00–19.00) | 8 | 16 |

| Alveolar ridge | 19 | 12.7% | 8.00 (3.00–16.00) | 1 | 18 |

| Lip | 17 | 11.3% | 9.00 (1.00–24.00) | 2 | 15 |

| Other locations | 26 | 17.3% | 8.50 (3.00–25.00) | 3 | 23 |

| p value | 0.87c | 0.07d | |||

|

Tumor size (cm) (n = 120) |

|||||

| ≤ 2 | 54 | 45% | 43.50 (18.00–99.00) | 4 | 50 |

| > 2 and ≤ 4 | 43 | 35.8% | 48.00 (16.00–127.0) | 6 | 37 |

| > 4 | 23 | 19.2% | 48.00 (17.00–119.0) | 4 | 19 |

| p value | 0.39c | 0.38d | |||

The LVD data was showed using median (minimum value–maximum value). The expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells data were described using absolute number (n). Sex data were accessible in 150 cases, age data in 143 cases, tobacco smoking data in 106 cases, tumor location data in 150 cases and tumor size data in 120 cases. Negative expression of podoplanin: immunostaining in less than 50% of neoplastic cells (i.e., scores of 0 and 1). Positive expression of podoplanin: immunostaining in 50% or more of neoplastic cells (i.e., scores of 2 and 3)

Min. minimum value, Max. maximum value

aThe p value was obtained with the Mann–Whitney test to evaluate differences in the LVD in the following comparisons: Sex (Male versus Female); Age (years) (< 60 versus ≥ 60)

bThe p value was obtained with the Fisher's exact test to evaluate differences in the expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells in the following comparisons: Sex (Male versus Female); Age (years) (< 60 versus ≥ 60)

cThe p value was obtained with the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by the Dunn’s multiple comparisons test to evaluate differences in the LVD in the following comparisons: Tobacco smoking (Current versus Former versus Never); Tumor location (Tongue versus Floor of the mouth versus Alveolar ridge versus Lip versus Other locations); Tumor size (cm) (≤ 2 versus > 2 and ≤ 4 versus > 4)

dThe p value was obtained with the Chi-square test to evaluate differences in the expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells in the following comparisons: Tobacco smoking (Current versus Former versus Never); Tumor location (Tongue versus Floor of the mouth versus Alveolar ridge versus Lip versus Other locations); Tumor size (cm) (≤ 2 versus > 2 and ≤ 4 versus > 4)

eSome tumors affected multiple locations. In these cases, only the main location was considered for this evaluation

No statistically significant differences were observed neither in the LVD nor in the expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells concerning sex, age, tobacco smoking, tumor location and tumor size (Table 1).

Of all 150 specimens, 83 (55.4%) showed high-intensity tumor budding (Fig. 1) and 67 (44.6%) showed low-intensity or no tumor budding.

LVD was greater in OSCC than in normal oral mucosa and in OSCC with high-intensity budding than in normal oral mucosa. Moreover, LVD did not differ between normal oral mucosa and OSCC with low-intensity or no tumor budding (Table 2). LVD was greater in tumors with high-intensity tumor budding than in tumors with low-intensity or no tumor budding (Table 2; Fig. 1). In tumors with high-intensity budding, LVD did not differ between the budding area and the area outside the budding (Table 2; Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Data and comparisons of lymphatic vascular density (LVD) (assessed by podoplanin immunostaining) in normal oral mucosa and in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC)

| Normal oral mucosa (n = 15) |

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) (n = 150) |

p valueb | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | p25 | p50 | p75 | Max | Min | p25 | p50 | p75 | Max | 0.01* |

| 4.00 | 6.00 | 7.00 | 7.00 | 11.00 | 1.00 | 6.00 | 9.00 | 12.00 | 26.00 | |

| Normal oral mucosa (n = 15) |

OSCC with low-intensity or no tumor budding (n = 67) | p valuec | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | p25 | p50 | p75 | Max | Min | p25 | p50 | p75 | Max | 0.06 |

| 4.00 | 6.00 | 7.00 | 7.00 | 11.00 | 1.00 | 6.00 | 8.00 | 10.00 | 24.00 | |

| Normal oral mucosa (n = 15) |

OSCC with high-intensity tumor buddinga (n = 83) |

p valued | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | p25 | p50 | p75 | Max | Min | p25 | p50 | p75 | Max | 0.00* |

| 4.00 | 6.00 | 7.00 | 7.00 | 11.00 | 2.00 | 6.00 | 9.00 | 14.00 | 26.00 | |

| OSCC with low-intensity or no tumor budding (n = 67) |

OSCC with high-intensity tumor buddinga (n = 83) |

p valuee | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | p25 | p50 | p75 | Max | Min | p25 | p50 | p75 | Max | 0.04* |

| 1.00 | 6.00 | 8.00 | 10.00 | 24.00 | 2.00 | 6.00 | 9.00 | 14.00 | 26.00 | |

| Tumor budding area in OSCC with high-intensity tumor budding (n = 83) |

Area outside the tumor budding in OSCC with high-intensity tumor budding (n = 83) |

p valuef | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | p25 | p50 | p75 | Max | Min | p25 | p50 | p75 | Max | 0.13 |

| 1.00 | 4.00 | 7.00 | 10.00 | 26.00 | 2.00 | 5.00 | 8.00 | 12.00 | 26.00 | |

Min. minimum value, p25 25th percentile, p50 50th percentile (median), p75 75th percentile, Max. maximum value

*Statistically significant p value (p < 0.05)

aThe highest value of LVD of each sample was used in this evaluation (accessed in the tumor budding area or in the area outside the tumor budding)

bThe p value was obtained with the Mann–Whitney test for normal oral mucosa versus oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC)

cThe p value was obtained with the Mann–Whitney test for normal oral mucosa versus OSCC with low-intensity or no tumor budding

dThe p value was obtained with the Mann–Whitney test for normal oral mucosa versus OSCC with high-intensity tumor budding

eThe p value was obtained with the Mann–Whitney test for OSCC with low-intensity or no tumor budding versus OSCC with high-intensity tumor budding

fThe p value was obtained with the Wilcoxon test for the tumor budding area in OSCC with high-intensity tumor budding versus the area outside the tumor budding in OSCC with high-intensity tumor budding

When compared to the lining epithelium of the normal oral mucosa, the expression of podoplanin was greater in neoplastic cells of OSCC, OSCC with high-intensity budding and OSCC with low-intensity or no tumor budding (Fig. 4). The expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells was also greater in tumors with high-intensity tumor budding than in tumors with low-intensity or no tumor budding (Figs. 2 and 4). Moreover, in tumors with high-intensity budding, the expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells was greater in the budding area than in the area outside the budding (Figs. 2 and 4).

Fig. 4.

Expression of podoplanin in the lining epithelium of normal oral mucosa (used as a control) and in neoplastic cells of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC). Note: Negative expression of podoplanin: immunostaining in less than 50% of the cells (i.e., scores of 0 and 1); Positive expression of podoplanin: immunostaining in 50% or more of the cells (i.e., scores of 2 and 3); 1The p value was obtained with Fisher’s exact test for normal oral mucosa versus OSCC; 2The p value was obtained with Fisher’s exact test for normal oral mucosa versus OSCC with low-intensity or no tumor budding; 3The p value was obtained with Fisher’s exact test for normal oral mucosa versus OSCC with high-intensity tumor budding; 4The p value was obtained with Fisher’s exact test for OSCC with low-intensity or no tumor budding versus OSCC with high-intensity tumor budding; 5The p value was obtained with McNemar’s test for the budding area versus the area outside the budding, in OSCC with high-intensity tumor budding; *Statistically significant p value (p < 0.05)

Discussion

Demonstrating an exceptional capacity for local invasion and distant dissemination, malignant neoplasms induce metastases that are an important cause of morbidity and mortality [28–30]. Several studies have suggested that lymphangiogenesis facilitates the lymphatic spread of malignant tumor cells and, in turn, regional metastasis to the lymph nodes [8, 9]. Increased LVD is associated with a greater occurrence of regional metastases and a lower survival rate in patients with OSCC [10, 14, 17]. The D2-40 antibody (i.e., anti-podoplanin), considered to be a specific marker of lymphatic vessels [10–17], has been widely used in studies evaluating tumor lymphangiogenesis.

Malignant neoplastic cells primarily use two pathways for dissemination: a lymphatic pathway, which allows the initial invasion into the lymph nodes that drain the sites of primary tumors, and blood vessel pathways, which promote direct dissemination to distant organs [28–30]. The microscopic observation of the invasion of neoplastic cells into the blood or lymphatic vessels has long been recognized as an indicator for poor prognosis. However, early studies addressing tumor angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis failed to distinguish lymphatic vessels from blood vessels due to the absence of specific lymphatic markers. In that context, the emergence of specific lymphatic vessels markers, including the antibody D2-40, has made it possible to advance research on the topic [9].

Our results revealed that LVD, assessed by podoplanin immunostaining, was greater in tumors with high-intensity tumor budding than in tumors with low-intensity or no tumor budding, which supports the idea that tumor budding is a morphological marker of the biological behavior of OSCC. The LVD was also greater in OSCC and in tumors with high-intensity budding than in normal mucosa but did not differ between normal mucosa and tumors with low-intensity or no tumor budding. Despite the absence of studies correlating tumor budding and lymphangiogenesis, several researchers have assessed LVD by podoplanin immunostaining along with clinical–pathological parameters of tumors’ aggressiveness. Sugiura et al. [14] observed greater LVD in OSCC showing regional metastases, while Miyahara et al. [10] observed a positive association between LVD in OSCC and tumor size, regional metastases, and an infiltrative histological pattern of invasion. However, those authors observed no differences in LVD between poorly, moderately, and well-differentiated tumors. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis by Tandon et al. [17] showed that the pooled Odd’s and Risk ratio of greater LVD for patient survival (derived from five studies) was statistically significant, generating evidence that the lymphangiogenesis evaluation by LVD in OSCC is noteworthy in suggesting prognosis.

Despite the relationship between tumor budding intensity and LVD, we found no differences in LVD between the budding area and the area outside the budding in tumors with high-intensity tumor budding. Those results demonstrate that the LVD is greater and homogeneously distributed in samples with high-intensity tumor budding regardless of the area evaluated.

Our results also suggest that tumors with high-intensity tumor budding show a greater expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells than tumors with low-intensity or no budding. Furthermore, in samples with high-intensity budding, the expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells was greater in the budding area than in the area outside the budding. Moreover, when compared to the lining epithelium of the normal mucosa, the expression of podoplanin was greater in neoplastic cells of OSCC, tumors with high-intensity budding and in tumors with low-intensity or no tumor budding. Although the English-language literature contains no research evaluating tumor budding and the expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells of OSCC, several studies have involved evaluating the association between podoplanin’s expression and the clinical–pathological parameters of tumor’s aggressiveness. Cueni et al. [20] found that the greater expression of podoplanin in the cytoplasm of neoplastic cells was associated with regional metastasis and a lower survival rate in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx. Bartuli et al. [31] observed that, in OSCC, the greater expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells was associated with regional metastasis and lower survival rates. Beyond that, De Sousa et al. [27] detected an association between the greater expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells and lower tumor differentiation at the invasive front of OSCC, which could relate to the fact that undifferentiated cells, in acquiring more mobility, allow migration and tumor invasion. Other studies on OSCC have also revealed a correlation between podoplanin’s expression in neoplastic cells and the presence of lymph node metastases, as well as worse survival rates, thereby confirming the protein’s role in tumor progression [19, 21]. In fact, in a recent systematic review, Mello et al. [22] showed that the immunoexpression of podoplanin may be correlated with regional metastasis, histological grading and clinical stage of OSCC, generating evidence that this protein could be a valuable prognostic marker that demands additional investigation.

Podoplanin, also known as PA2.26, OTS-8, Aggrus, D2-40, and T1α antigen, is a mucin-type transmembrane glycoprotein found on the surface of many types of normal cells, especially in the endothelium of lymphatic vessels. It is also seen on the surface of CAFs. Although podoplanin’s biological role is not yet fully understood, in vitro studies have shown that the protein determines the normal development of the lymphatic vascular system and induces platelet aggregation [18]. Added to that, several other studies have demonstrated podoplanin’s likely role in the pathogenesis of cancer, although its exact molecular function in neoplastic cells remains uncertain. Podoplanin is believed to interact with membrane and cytoskeleton proteins and thus induce the formation of extensions on the plasma membrane similar to phyllopodia, in addition to increasing cellular motility by facilitating tumor local invasion [20, 21, 32, 33]. In turn, the induction of platelet aggregation can facilitate the transport of tumor cells through blood vessels during metastasis [18, 20]. On top of that, podoplanin’s expression in keratinocytes prompts the destabilization of cell–cell adhesion structures mediated by the cadherin-E protein and the induction of vimentin’s expression, both of which are processes associated with the epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Those data indicate that podoplanin’s expression may be associated with the detachment of tumor cells and the invasion of the adjacent stroma, which are crucial steps in the formation of metastases and strongly related to the morphological phenomenon of tumor budding [20, 32, 34]. Our results, aligning with that hypothesis, reinforce the significance of tumor budding in the biological behavior of OSCC.

Finally, no differences were observed neither in the LVD nor in the expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells regarding clinicopathological data (sex, age, tobacco smoking, tumor location and tumor size). These findings suggests that, in OSCC, these clinicopathological parameters do not influence lymphangiogenesis and the expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells. Nevertheless, De Sousa et al. [27] found an association of LVD with tumor size and tumor location, as well as among podoplanin expression and age over 45 years in OSCC.

The main limitations of our study were the absence of data related to prognosis (e.g., clinical stage and patient survival). Additional morphological markers with a potential impact on prognosis could have been evaluated as well, along with the use of OSCC samples from the same anatomical site. Another limitation that should be considered is the fact that we used, as a control, specimens of normal oral mucosa collected in biopsies of the OSCC cases employed in the study. Although all these normal oral mucosa samples showed microscopic morphological features of normality and no presence of epithelial dysplasia or malignant tumor infiltration, its proximity to OSCC sites should generate possible molecular alterations not yet morphologically observed. Nevertheless, the results of the evaluation of LVD and expression of podoplanin in the lining epithelium of these normal oral mucosa samples were consistent with those observed in the literature [19, 35, 36].

In sum, our study demonstrated that LVD was greater in OSCC with high-intensity tumor budding than in tumors with low-intensity or no tumor budding. In tumors with high-intensity budding, LVD did not differ between the budding area and the area outside the budding. The expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells was also greater in tumors with high-intensity tumor budding than in ones with low-intensity or no tumor budding. Last, in tumors with high-intensity budding, the expression of podoplanin in neoplastic cells was greater in the budding area than in the area outside the budding. Those findings reinforce the hypothesis that tumor budding is a biological phenomenon associated with the progression and biological behavior of OSCC.

Author Contributions

EMA: conceptualization; data curation; investigation; supervision; visualization; writing—original draft. MR: conceptualization; investigation. JCV: conceptualization; investigation. MIMP: data curation; investigation. HMJ: conceptualization; writing—review and editing. GRS: conceptualization; writing—review and editing. PEAS: conceptualization; writing—review and editing. MCRH: conceptualization; formal analysis; funding acquisition; project administration; supervision; writing—review and editing.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico—Brasil (CNPq 437861/2018-0), Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais—Brasil (FAPEMIG APQ-01055-18), and Fundo de Incentivo à Pesquisa da PUC Minas—Brasil (FIP-2018/1179). The study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001. MCRH was a research fellow of FAPEMIG (CDS-PPM-00653-16), and MR had a CNPq scholarship (PIBIC / CNPq 22187 − 2018).

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Minas Gerais—PUC Minas (CAAE 74605417.0.0000.5137).

Consent to Participate

This study has obtained IRB approval from Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Minas Gerais—PUC Minas (CAAE 74605417.0.0000.5137) and the need for informed consent was waived.

Consent for Publication

For this type of study consent for publication is not required.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Chi AC, Day TA, Neville BW. Oral cavity and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma—an update. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(5):401–21. doi: 10.3322/caac.21293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Togni L, Caponio VCA, Zerman N, et al. The emerging impact of tumor budding in oral squamous cell carcinoma: main issues and clinical relevance of a new prognostic marker. Cancers (Basel) 2022;14:3571. doi: 10.3390/cancers14153571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Almangush A, Salo T, Hagström J, Leivo I. Tumour budding in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma—a systematic review. Histopathology. 2014;65:587–94. doi: 10.1111/his.12471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kale AD, Angadi PV. Tumor budding is a potential histopathological marker in the prognosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma: current status and future prospects. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2019;23:318–23. doi: 10.4103/jomfp.JOMFP_331_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang C, Huang H, Huang Z, et al. Tumor budding correlates with poor prognosis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in tongue squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2011;40:545–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2011.01041.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hong KO, Oh KY, Shin WJ, Yoon HJ, Lee JI, Hong SD. Tumor budding is associated with poor prognosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma and histologically represents an epithelial-mesenchymal transition process. Hum Pathol. 2018;80:123–9. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2018.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ho YY, Wu TY, Cheng HC, Yang CC, Wu CH. The significance of tumor budding in oral cancer survival and its relevance to the eighth edition of the american Joint Committee on Cancer staging system. Head Neck. 2019;41:2991–3001. doi: 10.1002/hed.25780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tammela T, Petrova TV, Alitalo K. Molecular lymphangiogenesis: new players. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:434–41. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ran S, Volk L, Hall K, Flister MJ. Lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic metastasis in breast cancer. Pathophysiology. 2010;17:229–51. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyahara M, Tanuma J, Sugihara K, Semba I. Tumor lymphangiogenesis correlates with lymph node metastasis and clinicopathologic parameters in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2007;110:1287–94. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Longatto Filho A, Oliveira TG, Pinheiro C, et al. How useful is the assessment of lymphatic vascular density in oral carcinoma prognosis? World J Surg Oncol. 2007;5:140. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-5-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marinho VFZ, Sanches FSF, Rocha GFS, Metze K, Gobbi H. D2-40, a novel lymphatic endothelial marker: identification of lymphovascular invasion and relationship with axillary metastases in breast cancer. J Bras Patol Med Lab. 2008;44:45–50. doi: 10.1590/S1676-24442008000100009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao D, Pan J, Li XQ, Wang XY, Tang C, Xuan M. Intratumoral lymphangiogenesis in oral squamous cell carcinoma and its clinicopathological significance. J Oral Pathol Med. 2008;37:616–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2008.00707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sugiura T, Inoue Y, Matsuki R, et al. VEGF-C and VEGF-D expression is correlated with lymphatic vessel density and lymph node metastasis in oral squamous cell carcinoma: implications for use as a prognostic marker. Int J Oncol. 2009;34:673–80. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alaeddini M, Etemad-Moghadam S. Lymphangiogenesis and angiogenesis in oral cavity and lower lip squamouscell carcinoma. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;82:385–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bjorl.2015.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan J, Jiang Y, Ye M, Liu W, Feng L. The clinical value of lymphatic vessel density, intercellular adhesion molecule 1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 expression in patients with oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma. J Cancer Res Ther. 2014;10:C125-30. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.145827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tandon A, Sandhya K, Singh NN, Kumar A. Prognostic relevance of lymphatic vessel density in squamous cell carcinomas of the oral cavity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck Pathol. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s12105-022-01474-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ugorski M, Dziegiel P, Suchanski J. Podoplanin—a small glycoprotein with many faces. Am J Cancer Res. 2016;6:370–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuan P, Temam S, El-Naggar A, et al. Overexpression of podoplanin in oral cancer and its association with poor clinical outcome. Cancer. 2006;107:563–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cueni LN, Hegyi I, Shin JW, et al. Tumor lymphangiogenesis and metastasis to lymph nodes induced by cancer cell expression of podoplanin. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:1004–16. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kreppel M, Scheer M, Drebber U, Ritter L, Zöller JE. Impact of podoplanin expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma: clinical and histopathologic correlations. Virchows Arch. 2010;456:473–82. doi: 10.1007/s00428-010-0915-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mello FW, Kammer PV, Silva CAB, et al. Prognostic and clinicopathological significance of podoplanin immunoexpression in oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review. J Oral Pathol Med. 2021;50:1–9. doi: 10.1111/jop.13041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leão PLR, Marangon Junior H, Melo VVM, et al. Reproducibility, repeatability, and level of difficulty of two methods for tumor budding evaluation in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2017;46:949–55. doi: 10.1111/jop.12578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cicchetti DV, Sparrow SA. Developing criteria for establishing interrater reliability of specific items: applications to assessment of adaptive behavior. Am J Ment Defic. 1981;86:127–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weidner N, Semple JP, Welch WR, Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis and metastasis—correlation in invasive breast carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199101033240101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin NN, Wang P, Zhao D, Zhang FJ, Yang K, Chen R. Significance of oral cancer-associated fibroblasts in angiogenesis, lymphangiogenesis, and tumor invasion in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2017;46:21–30. doi: 10.1111/jop.12452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Sousa SF, Gleber-Netto FO, de Oliveira-Neto HH, Batista AC, Nogueira Guimarães Abreu MH, de Aguiar MC. Lymphangiogenesis and podoplanin expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma and the associated lymph nodes. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2012;20:588–94. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e31824bb3ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fidler IJ. The pathogenesis of cancer metastasis: the seed and soil hypothesis revisited. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:453–8. doi: 10.1038/nrc1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Faraji F, Eissenberg JC. Seed and soil: a conceptual framework of metastasis for clinicians. Mo Med. 2013;110:302–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Q, Zhang H, Jiang X, Qian C, Liu Z, Luo D. Factors involved in cancer metastasis: a better understanding to “seed and soil” hypothesis. Mol Cancer. 2017;16:176. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0742-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bartuli FN, Luciani F, Caddeo F, et al. Podoplanin in the development and progression of oral cavity cancer: a preliminary study. Oral Implantol (Rome) 2012;5:33–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martín-Villar E, Scholl FG, Gamallo C, Yurrita MM, Muñoz-Guerra M, Cruces J, Quintanilla M. Characterization of human PA2.26 antigen (T1alpha-2, podoplanin), a small membrane mucin induced in oral squamous cell carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 2005;113:899–910. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wicki A, Lehembre F, Wick N, Hantusch B, Kerjaschki D, Christofori G. Tumor invasion in the absence of epithelial-mesenchymal transition: podoplanin-mediated remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:261–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scholl FG, Gamallo C, Quintanilla M. Ectopic expression of PA2.26 antigen in epidermal keratinocytes leads to destabilization of adherens junctions and malignant progression. Lab Investig. 2000;80:1749–59. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Janardanan-Nair AGD, B R B. V. podoplanin expression in oral potentially malignant disorders and oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Exp Dent. 2017;9:e1418–24. doi: 10.4317/jced.54213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aiswarya A, Suresh R, Janardhanan M, Savithri V, Aravind T, Mathew L. An immunohistochemical evaluation of podoplanin expression in oral leukoplakia and oral squamous cell carcinoma to explore its potential to be used as a predictor for malignant transformation. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2019;23:159. doi: 10.4103/jomfp.JOMFP_272_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Not applicable.