Abstract

Background

Leishmaniasis is a tropical disease caused by protozoan parasites of the genus Leishmania. Mucosal leishmaniasis has been described as secondary to the cutaneous form; however, isolated mucosal involvement can also occur. Specifically, mucosal leishmaniasis of the lip is poorly described and its diagnosis challenges clinicians.

Methods

We herein report a case of mucosal leishmaniasis affecting the lower lip without cutaneous involvement in a 20-year-old Venezuelan man. The patient had no relevant past medical history. Clinically, a mass-like lesion with ulcerations and crusts was observed.

Results

Microscopically, the lesion was composed of granulomatous inflammation along with macrophages containing intracytoplasmic inclusions similar to round-shaped Leishmania. The species Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis was confirmed. Treatment with meglumine antimonate was effective. The lesion healed satisfactorily, and no side effects or recurrences were observed.

Conclusion

Clinicians should be aware of isolated forms of mucosal leishmaniasis of the lip, even in cases where the cutaneous lesion is undetected or clinically manifests as self-limiting. Knowing the endemic areas in the scenario of the dynamics of the ecoepidemiology of leishmaniasis is also essential for surveillance and counselling of the population.

Keywords: infectious diseases, leishmania, leishmaniasis, lip, meglumine antimonate, neglected diseases

Introduction

Leishmaniasis encompasses a group of infectious diseases that can occur mainly with visceral, cutaneous, mucosal, and mucocutaneous involvement [1]. It is caused by protozoa of the genus Leishmania transmitted to humans by infected female sandflies. Approximately 20 species of Leishmania spp. and over 90 species of sandflies are currently recognized for transmitting Leishmania parasites [2]. Leishmaniasis has been linked with poverty and poor living conditions. In the Americas, leishmaniases are a public health concern due to their prevalence, wide geographical distribution, and morbidity and mortality. In this scenario, the condition was listed among the neglected tropical diseases by the World Health Organization [3].

About 700,000 to 1 million new leishmaniasis cases per year are documented in nearly 100 endemic countries, including Venezuela [1, 2]. In particular, the distribution of American tegumentary leishmaniasis has been found from the South of the United States to the South of Argentina [4]. Although the most common clinical manifestation of American tegumentary leishmaniasis is the cutaneous form, Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis is one of the most prevalent species causing mucocutaneous leishmaniasis [5]. In endemic regions for the transmission of L. braziliensis, mucosal lesions usually involve the upper respiratory tract, with a predilection for the nose in 98% of cases [6]. The mucosal lesion usually appears weeks or years after the initial cutaneous lesion has healed due to the possible hematogenous spread from the primary focus [7, 8]. Nonetheless, a mucosal lesion can appear when a cutaneous lesion is active [9].

Manifestations of leishmaniasis in the oral cavity, mainly in the palate, are usually associated with the nasal region [7, 10]. About 91% of individuals have oral lesions concomitant with manifestations at other mucosal locations, while 9% have no associated lesions [7]. Few studies have documented mucosal leishmaniasis in the lip region in young adults with no associated previous medical history; in turn, its diagnosis challenges clinicians [11, 12]. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to report an exuberant case of primary mucosal leishmaniasis on the lower lip with no previous or concomitant cutaneous lesions in a young Venezuelan man.

Case Report

A 20-year-old male patient from Guatire, Venezuela, was referred to the dermatology clinic of Universidad Central de Venezuela, Caracas, for evaluation of a large and firm mass in the right lower lip of three months duration. A noncontributory family, medical, or socioeconomic history was reported, with the absence of psychiatric disorders, smoking, or alcohol use. The patient was not taking any medications, had no known drug allergies, and no history of trauma involving the oral and maxillofacial region.

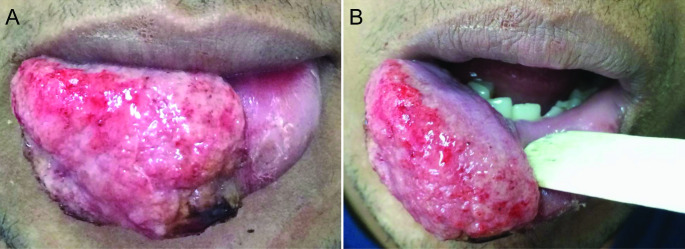

Extraoral examination revealed the absence of submandibular or cervical lymphadenopathy or changes in other body regions. An ulcerated tumor lesion was observed, with base infiltration and irregular borders, and a granular base covered by crusts and exudates involving 2/3 of the lower lip. The lesion measured 2.5 × 1.5 cm in size and painful on palpation (Fig. 1 A). No changes were observed in the oral mucosa and adjacent structures (Fig. 1B). Due to the clinical appearance of the lesion, the differential diagnoses included mainly chronic macrocheilia lesions. Thus, the main conditions considered were allergies/immunological diseases, bacterial infections (e.g., acquired oral syphilis [AOS] and tuberculosis), fungal and protozoal diseases (e.g., paracoccidioidomycosis [PCM], histoplasmosis, sporotrichosis, and leishmaniasis), lip squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC), and soft tissue sarcomas.

Fig. 1.

Clinical aspects of mucosal leishmaniasis of the lower lip.(A) Exuberant ulcerated mass on the lower lip with a granulomatous surface and crusts. (B) Intraoral view revealing intact labial mucosa and normal-appearing contiguous areas

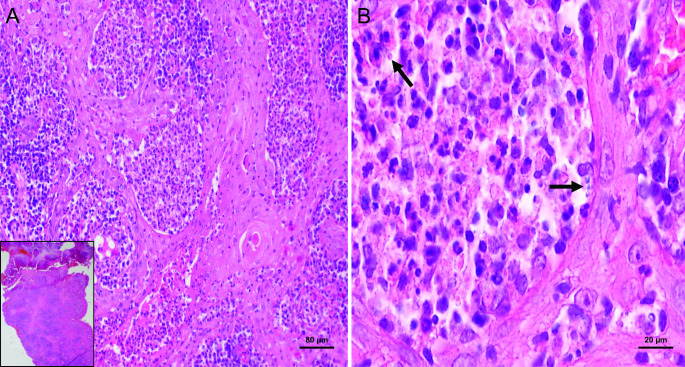

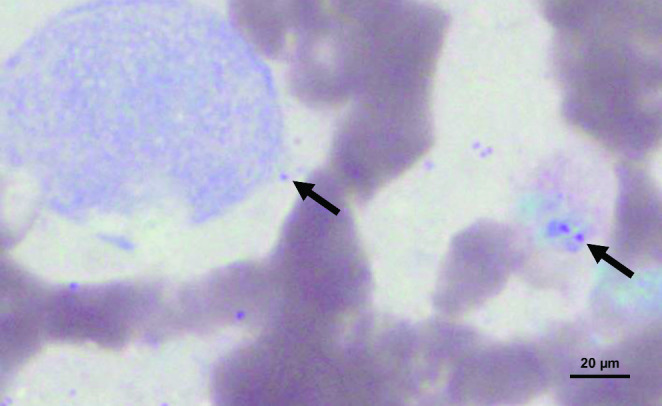

The blood profile (blood count, biochemistry, and complement) revealed no abnormality. Serological tests were negative for syphilis (Veneral Disease Research Laboratory, VDRL) and HIV-1 and HIV-2 antibodies. Direct mycological tests, fungal culture, and serology for fungal diseases were all nonreactive. In parallel, the patient was tested for tuberculosis, sporotrichosis, and leishmaniasis. The tuberculosis test was nonreactive and the skin test for sporotrichosis was within the normal range. However, in the leishmanin skin test (Montenegro test), an induration at the injection site revealed a diameter of 13 mm (reference value: a diameter ≥ 5 mm is considered to be a positive reaction). A smear of the lesion was performed and Giemsa staining revealed amastigote-like forms of Leishmania within the macrophages (Fig. 2). An incisional biopsy was carried out under local anesthesia. Microscopically, the tissue fragment revealed serohematic crusts with pseudoepitheliomatous epithelial hyperplasia. The lamina propria was composed of granulomatous inflammation with macrophages and plasma cells, along with macrophages containing intracytoplasmic inclusions similar to round-shaped Leishmania (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Cytopathological aspects of Leishmania spp. Scarification of the lesion on the labial mucosa reveals amastigote forms (arrows) parasitized within macrophages (Giemsa stain, ×100, oil immersion lens)

Fig. 3.

Histopathological aspects of mucosal leishmaniasis of the lower lip. (A) Microscopically, a tissue fragment with a serohematic crust and pseudoepitheliomatous epithelial hyperplasia (inset) is observed. The labial mucosa exhibits a granulomatous inflammation of macrophages and plasma cells with (B) the presence of macrophages containing intracytoplasmic inclusions similar to round-shaped Leishmania (hematoxylin and eosin staining: inset, ×4, a, ×10 magnification, and b, ×100 magnification with oil immersion lens)

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed according to a previously published method using primers LB1 and LB2 (5 ´ GGG GTT GGT GTA ATA TAG TGG 3 ´ and 5 ´ CTA ATT GTG CAG GGG GAG G 3 ´, respectively) [13]. Infection by L. (V.) braziliensis was confirmed. The patient was treated with meglumine antimonate (Glucantime®; 20 mg/kg, I.M. for 30 days). His liver profile and cardiovascular system were examined at the end of treatment and no side effects were detected. At one-month follow-up, healing of the lesion was observed, with no recurrence (Fig. 4). The case was notified because of the control and surveillance measures adopted within the country.

Fig. 4.

Follow-up period. Clinical healing and absence of signs of recurrence in the lower lip after 1 month of follow-up

Discussion

Data from previous reports of mucosal leishmaniasis reveal that manifestations in the oral cavity are uncommon, and the anatomical topography varies between studies [6, 9, 14]. While one study demonstrated that the soft palate, uvula and tonsils were responsible for 25.4% of cases [10], a multicenter study revealed that the most affected site was the tongue, followed by the palatal mucosa [14]. Motta et al. [9] documented that the palate followed by the oropharynx were the most common anatomical locations. Of relevance, the lips were reported in 4.9% of cases in a large Brazilian study [10], whereas one series showed that the upper lip was affected in three out of 11 patients (27.3%) [9]. Furthermore, two former series, one from Tunisia [11] and the other from Iran [12], analyzed individuals with labial leishmaniasis. The first study reported that the lower lip was affected in a quarter of the patients [11], while the latter reported that the lower lip was involved in three of the seven cases [12].

Oral leishmaniasis usually presents as an erythematous swelling associated with a granulomatous ulceration [9]. Specifically on the lips, a central crusted ulceration and partial lip swelling can be seen in most affected individuals [11, 12, 15]. In a recent study that comprised 47 cases of chronic macrocheilia, an inflammatory condition responsible for swelling of one or both lips, with evolution of at least eight weeks, almost half of patients with a mean age of 32.3 years were diagnosed with leishmaniasis [15]. The characteristics of our case are similar to those of the cited study [15], considering that the present patient had a lesion with granulomatous ulcers and crusts on the lower lip of 12 weeks duration. We initially ruled out the hypothesis of syndromes related to the digestive or respiratory system since the patient had no apparent signs or symptoms [15].

The exact mechanisms underlying the development of mucosal lesions remain to be fully understood. An infiltrated and ulcerated plaque of the mucous layer of the lip implies direct inoculations of Leishmania parasites into the lip after bites from infected sandflies [11]. Some studies have estimated that up to 5% of individuals with cutaneous forms of leishmaniasis may have a natural progression of the disease to mucosal leishmaniasis; therefore, the idea of the mucosal lesion being secondary to the cutaneous form cannot be ruled out [6, 8]. It has also been suggested that it is easier for sandflies to bite the lips of individuals with nasal polyps, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, due to their need to breathe through the mouth rather than through the nose [16]. In line with a previous series, in which all patients were immunocompetent, except for one HIV-positive individual [17], the patient reported here had no relevant past medical history and no sexually transmitted diseases but lived in an endemic area of low socioeconomic status. These last aspects, however, are more plausible as risk factors predisposing to the disease. It is noteworthy that estimated rates of asymptomatic leishmaniasis are about 12% among HIV-infected patients [18].

In Venezuela, 47,762 cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis were diagnosed between 1988 and 2007, revealing 2,388 cases per year and an average annual rate of 10.5 per 100,000 inhabitants [19]. Low educational levels, overcrowding and unhealthy living conditions, limited access to health services, malnutrition, and high unemployment rates are highly prevalent in some regions of South America [20]. Moreover, due to the relationship between people and animals as well as the rural exodus, some urban areas may pose a risk to new immigrants. For instance, in northeast Brazil, cutaneous leishmaniasis has taken place at the interface of peri-urban and rural areas among individuals of all ages and sexes [21].

A distinct male predilection has been described for mucosal leishmaniasis, including the oral cavity and lips [6, 7, 11, 14]. In addition to the different exposure risks, including occupational/professional factors, this dissimilarity can be attributed to sexual variations that influence immunomodulatory mechanisms since the prevalence of cases comprises the post-puberty and adulthood period [22]. Androgen-associated immunosuppressive effects were observed for most infections, whereas steroids revealed immunomodulatory characteristics [22]. Conversely, a high prevalence/incidence of cutaneous leishmaniasis has been observed in women worldwide [23]. A particular example is among certain cultures of Yemeni women who wear face veils, where the disease can contribute to cosmetic disfigurement, leading to social stigmatization, late presentation, and more advanced disease [24].

Former studies have documented cases of oral leishmaniasis in both pediatric and adult populations [11, 12, 14]. A study revealed that when the oral lesion is isolated (mean 31.7 years), it is associated with an age 20 years younger than when it is related to other mucosal sites (mean 51.9 years) [7]. In contrast, a study found that the number of patients with mucosal leishmaniasis was higher in the second decade of life [6]. Nevertheless, considering that most individuals with the mucosal disease have or had cutaneous leishmaniasis concomitantly with or before mucosal involvement, fluctuations in the number of cutaneous leishmaniasis cases are expected to influence the prevalence of the number of reported cases of the disease [6]. Our patient’s age is also in line with cases of primary labial leishmaniasis published elsewhere [11]. This is interesting from the point of view of differential diagnosis with other conditions. As such, the most represented age group of individuals with AOS was between 20 and 29 years in South America [25], in agreement with our patient’s age. However, in contrast to our case, oral PCM and oral tuberculosis differ in terms of age of occurrence since they usually manifest in the sixth decade of life, even though there are rare exceptions of both diseases occurring in the age group of 20 to 29 years [26, 27]. Although LSCC affects nearly 80% of middle-aged/older men, only 1.6% of affected patients were in their third decade of life [28]. Some other examples are Miescher’s granulomatous cheilitis, Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome, Crohn’s disease, sarcoidosis, and leprosy, which encompass the diagnosis of chronic macrocheilia and can be included in the differential diagnostic algorithm for mucosal leishmaniasis, especially on the lips [15]. Notably, the main conditions found at oral diagnostic services in the context of lower lip lesions are those for the group of reactive/inflammatory lesions (mucocele) and potentially malignant oral disorders (actinic cheilitis), ranging from 33.1 to 43.4%, respectively [29]. Nonetheless, leishmaniasis was not reported in the study by Barros et al. [29], or among lesions of the lips diagnosed in a tertiary hospital-based survey in India [30].

Difficulty in diagnosing mucosal lesions has been described since amastigotes can be sparse or, in some cases, not detected by Giemsa staining [17]. The Giemsa method reveals amastigotes identified as round or oval bodies 2–4 μm in diameter with typical nuclei and kinetoplasts [31]. Microscopically, it is possible to observe macrophagic cytoplasmic inclusions that may suggest Leishmania amastigotes. Silveira et al. [32] highlighted the detection of kinetoplasts in intracytoplasmic round-shaped inclusions within macrophages. Furthermore, it has been argued that lesions in the oral cavity may exhibit more significant parasitism due to nonspecific local inflammatory and infectious processes that favor an influx of parasites by dissemination through the blood system and a greater number of potential host cells for the parasite [33]. When the parasite load of mucosal leishmaniasis is low, it can be challenging to differentiate amastigotes from other parasites such as Toxoplasma gondii and Histoplasma capsulatum [17]. However, histoplasmosis is microscopically characterized by a diffuse infiltrate of macrophages or, more commonly, a collection of macrophages organized in granulomas. Multinucleated giant cells are usually observed in association with granulomatous infiltration [34]. The fungal parasitic phase can be seen with the Giemsa stain as oval forms of 3–4 μm in diameter, with a typical cap stain and a small light halo around it, which are located in phagocytic cells [35]. Also, H. capsulatum yeasts are usually stained red-violet and surrounded by a light halo by periodic-acid-Schiff and brown-black by the silver methenamine Gomori-Grocott stain [34].

Immunohistochemistry and/or PCR may be essential to confirm the diagnosis of leishmaniasis. Although this last tool is more sensitive than immunohistochemistry, it is not available in some endemic regions [17]. A recent panorama has drawn attention to possible negligence regarding the use of the leishmanin skin test in epidemiological studies, which has been reduced in favor of serological and molecular tests [36]. It is worth mentioning that the leishmanin skin test was important to guide us in the diagnosis, mainly because the patient had no cutaneous manifestations. Not least, the diagnosis of our case was also based on the microscopical findings and PCR assay.

Regarding the treatment of mucosal leishmaniasis, the medication regimens used in South American countries and for the patient of this study are in accordance with the guidelines of the Pan American Health Organization, which state that the use of pentavalent antimonials with or without oral pentoxifylline continues to be the treatment of choice [37]. Compared to placebo, at one-year follow-up, intramuscular meglumine antimoniate administered for 20 days to treat L. braziliensis and L. panamensis infections in immunocompetent people with both the cutaneous and mucocutaneous forms may increase the likelihood of a complete cure [38]. In our case, we did not observe the presence of concomitant infections, nausea and vomiting or the occurrence of toxicity by pentavalent antimonials.

In summary, this study contributed by reporting an exuberant case of mucosal leishmaniasis in the lower lip presenting as a mass associated with granulomatous ulceration and crusts. Carefully reviewing the differential diagnoses of mucosal leishmaniasis of the lip is important since in some cases where the cutaneous lesion is not detected or clinically manifests as self-limiting the diagnosis can be challenging. Clinicians should be aware of endemic areas regarding the dynamics of leishmaniasis ecoepidemiology for adequate diagnosis, surveillance, and counseling of the population.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES, Finance Code 001), Brazil. J.A.A.A. is the recipient of a fellowship. Mrs. E. Greene provided English editing of the manuscript.

Funding

Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (Finance Code 001).

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Approval

Data was collected in accordance with guidelines from the institutional Research Ethics Board.

Consent to Participate

No identifier information is included in the case report, and the study meets the waiver criteria for the institutional review board of Universidad Central de Venezuela.

Consent for Publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for data collection and publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Bruno Augusto Benevenuto de Andrade, Email: brunoabandrade@ufrj.br, Email: augustodelima33@hotmail.com.

Mariana Villarroel-Dorrego, Email: mvillarroeldorrego@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Burza S, Croft SL, Boelaert M, Leishmaniasis Lancet. 2018;392:951–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31204-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Leishmaniasis. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis. Assessed on July 23, 2022.

- 3.Lin Y, Fang K, Zheng Y, Wang HL, Wu J. Global burden and trends of neglected tropical diseases from 1990 to 2019. J Travel Med. 2022;29:taac031. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taac031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alvar J, Vélez ID, Bern C, et al. Leishmaniasis worldwide and global estimates of its incidence. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e35671. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strazzulla A, Cocuzza S, Pinzone MR, et al. Mucosal leishmaniasis: an underestimated presentation of a neglected disease. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:805108. doi: 10.1155/2013/805108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cincurá C, de Lima CMF, Machado PRL, et al. Mucosal leishmaniasis: a retrospective study of 327 cases from an endemic area of Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;97:761–6. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.da Costa DC, Palmeiro MR, Moreira JS, et al. Oral manifestations in the American tegumentary leishmaniasis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e109790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bedoya-Pacheco SJ, Araujo-Melo MH, Valete-Rosalino CM, et al. Endemic tegumentary leishmaniasis in Brazil: correlation between level of endemicity and number of cases of mucosal disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;84:901–5. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Motta AC, Lopes MA, Ito FA, Carlos-Bregni R, de Almeida OP, Roselino AM. Oral leishmaniasis: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases. Oral Dis. 2007;13:335–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2006.01296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vicente CR, Falqueto A. Differentiation of mucosal lesions in mucocutaneous leishmaniasis and paracoccidioidomycosis. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0208208. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammami-Ghorbel H, Ben Abda I, Badri T, et al. Mucosal leishmaniasis of the lip: an emerging clinical form in Tunisia. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1212–5. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohammadpour I, Motazedian MH, Handjani F, Hatam GR. Lip leishmaniasis: a case series with molecular identification and literature review. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17:96. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-2178-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ortega Díaz JE, Zerpa O, Sosa A, Rodríguez N, Aranzazu N. Estudio clínico, epidemiológico y caracterización taxonômica de leishmaniasis cutânea en el estado Vargas, Venezuela. Vargas, Venezuela. Dermatología Venez. 2004;42:10–6. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mignogna MD, Celentano A, Leuci S, et al. Mucosal leishmaniasis with primary oral involvement: a case series and a review of the literature. Oral Dis. 2015;21:e70–e8. doi: 10.1111/odi.12268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toumi A, Litaiem N, Gara S, et al. Chronic macrocheilia: a clinico-etiological series of 47 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2021;60:1497–503. doi: 10.1111/ijd.15685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Veraldi S, D’Agostino A, Pontini P, Guanziroli E, Gatt P. Nasal polyps: a predisposing factor for cutaneous leishmaniasis of the lips? Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:443–5. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sánchez-Romero C, Júnior HM, Matta VLRD, et al. Immunohistochemical and molecular diagnosis of mucocutaneous and mucosal leishmaniasis. Int J Surg Pathol. 2020;28:138–45. doi: 10.1177/1066896919876706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mannan SB, Elhadad H, Loc TTH, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of asymptomatic leishmaniasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Parasitol Int. 2021;81:102229. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2020.102229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Lima H, Borges R, Escobar J, Convit J. Leishmaniasis cutánea americana en Venezuela: un análisis clínico epidemiológico a nivel nacional y por entidad federal, 1988–2007. Bol Mal Salud Amb. 2010;5:283–99. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bilal U, Hessel P, Perez-Ferrer C, et al. Life expectancy and mortality in 363 cities of Latin America. Nat Med. 2021;27:463–70. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-01214-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oliveira CC, Lacerda HG, Martins DR, et al. Changing epidemiology of American cutaneous leishmaniasis (ACL) in Brazil: a disease of the urban-rural interface. Acta Trop. 2004;90:155–62. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Araújo Albuquerque LP, da Silva AM, de Araújo Batista FM, de Souza Sene I, Costa DL, Costa CHN. Influence of sex hormones on the immune response to leishmaniasis. Parasite Immunol. 2021;43:e12874. doi: 10.1111/pim.12874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scheufele CJ, Giesey RL, Delost GR. The global, regional, and national burden of leishmaniasis: An ecologic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2017. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1203–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al-Kamel MA. Impact of leishmaniasis in women: a practical review with an update on my ISD-supported initiative to combat leishmaniasis in Yemen (ELYP) Int J Womens Dermatol. 2016;2:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Andrade BAB, de Arruda JAA, Gilligan G, et al. Acquired oral syphilis: A multicenter study of 339 patients from South America. Oral Dis. 2022;28:1561–72. doi: 10.1111/odi.13963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Arruda JAA, Schuch LF, Abreu LG, et al. A multicentre study of oral paracoccidioidomycosis: Analysis of 320 cases and literature review. Oral Dis. 2018;24:1492–502. doi: 10.1111/odi.12925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Farias Gabriel A, Kirschnick LB, Só BB, et al. Oral and maxillofacial tuberculosis: A systematic review. Oral Dis. 2022 doi: 10.1111/odi.14290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silva LVO, de Arruda JAA, Abreu LG, et al. Demographic and clinicopathologic features of actinic cheilitis and lip squamous cell carcinoma: a Brazilian multicentre study. Head Neck Pathol. 2020;14:899–908. doi: 10.1007/s12105-020-01142-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barros CC, Medeiros CK, Rolim LS, et al. A retrospective 11-year study on lip lesions attended at an oral diagnostic service. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2020;25:e370–e4. doi: 10.4317/medoral.23390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bansal S, Shaikh S, Desai RS, et al. Spectrum of lip lesions in a tertiary care hospital: an epidemiological study of 3009 Indian patients. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:115–9. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.202280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Vries HJC, Schallig HD, Cutaneous leishmaniasis A 2022 updated narrative review into diagnosis and management developments. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s40257-022-00726-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silveira HA, Panucci BZM, Silva EV, Mesquita ATM, León JE. Microscopical diagnosis of oral leishmaniasis: kinetoplast. Head Neck Pathol. 2021;15:1085–6. doi: 10.1007/s12105-021-01304-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palmeiro MR, Morgado FN, Valete-Rosalino CM, et al. Comparative study of the in situ immune response in oral and nasal mucosal leishmaniasis. Parasite Immunol. 2012;34:23–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2011.01343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Drak Alsibai K, Couppié P, Blanchet D, et al. Cytological and histopathological spectrum of histoplasmosis: 15 years of experience in French Guiana. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:591974. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.591974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bava J, Troncoso A. Giemsa and Grocott in the recognition of Histoplasma capsulatum in blood smears. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2013;3:418–20. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(13)60088-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carstens-Kass J, Paulini K, Lypaczewski P, Matlashewski G. A review of the leishmanin skin test: A neglected test for a neglected disease. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15:e0009531. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pan American Health Organization. Guideline for the treatment of leishmaniasis in the Americas. Second edition. Washington, DC: PAHO; 2022. Available from: 10.37774/9789275125038.

- 38.Pinart M, Rueda JR, Romero GA, et al. Interventions for American cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;8:CD004834. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004834.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Not applicable.