Abstract

During the COVID-19 pandemic, U.S. youth faced various stressors that affected their schooling experiences, social relationships, family dynamics, and communities. These stressors negatively impacted youths' mental health. Compared to White youths, ethnic-racial minority youths were disproportionately affected by COVID-19-related health disparities and experienced elevated worry and stress. In particular, Black and Asian American youths faced the compounded effects of a dual pandemic due to their navigation of both COVID-19-related stressors and increased exposure to racial discrimination and racial injustice, which worsened their mental health outcomes. However, protective processes such as social support, ethnic-racial identity, and ethnic-racial socialization emerged as mechanisms that attenuated the effects of COVID-related stressors on ethnic-racial youths’ mental health and promoted their positive adaptation and psychosocial well-being.

Keywords: Dual pandemic, Mental health, Ethnic-racial minority, Adolescents, Racial discrimination

Background

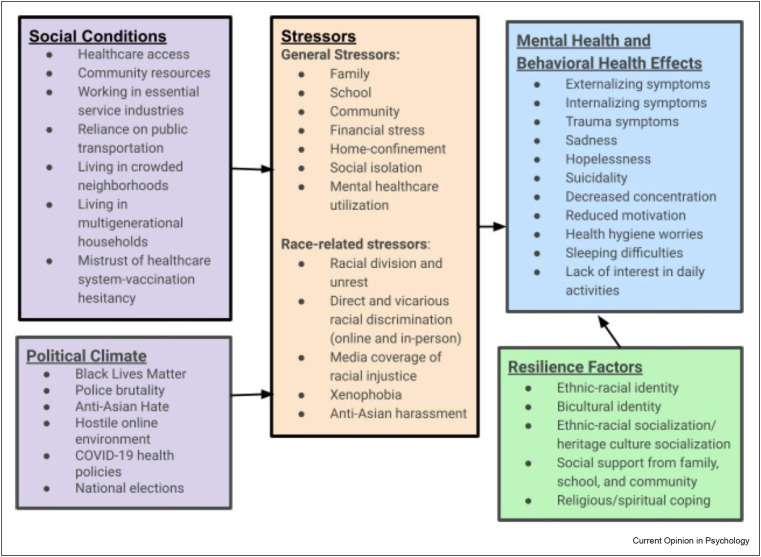

The COVID-19 pandemic had devastating effects on children and families, particularly those from ethnic-racial minority backgrounds. Non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic communities experienced disproportionately higher rates of COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and mortality compared to non-Hispanic White communities in the United States [1]. These disparities were evident in pediatric populations, with non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic children experiencing higher rates of COVID-19 infections and exposure compared to White children [2]. Several factors contributed to these disparities, including poorer access to health care, limited community resources, overrepresentation of ethnic-racial minorities in essential service industries, higher reliance on public transportation, higher likelihood of living in crowded neighborhoods, and higher rates of living in multigenerational households [2]. Other historical factors such as the long-term mistrust of the healthcare system by ethnic-racial minority children and families exacerbate these health disparities, and illuminate how systemic racism and structural inequities continue to affect their lives, health, and well-being. Despite exposure to multiple health and race-related stressors, ethnic-racial minority youths relied on family resources and cultural strengths to successfully navigate the pandemic. This article highlights the stressors that ethnic-racial minority youths faced during the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the protective processes that promoted these youths’ resilience in the U.S (see Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Model of the dual pandemic and its effects on ethnic-racial minority youths.

Stressors associated with the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic and shelter-in-place policies caused significant disruption to youths' academic progress and milestones, mental health, physical health, and social relationships [3, 4, 5]. Family dynamics were affected by financial stress, loss of loved ones, and caregiver job loss [7]. Ethnic-racial minority families experienced more health and financial hardships compared to White families [6]. These hardships were associated with higher levels of parental psychological distress, parenting stress, and adolescent loneliness [7]. In fact, youths reported declines of open family communication, parental support, and family satisfaction that coincided with caregivers' perceptions of pandemic-related stress [8]. Consequently, strained family functioning negatively affected youths’ mental health [9].

COVID-19 stressors related to school, financial stress, and home-confinement influenced youths’ mental health [10,11]. For example, in a longitudinal study assessing the impact of family behaviors on psychopathology in a sample of children and adolescents living in the U.S., Rosen et al. [11] found that youths reported a substantial increase in internalizing and externalizing problems over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. Relative to youths who were exposed to fewer pandemic-related stressors, youths who were exposed to more pandemic-related stressors reported higher rates of internalizing and externalizing symptoms during the period of the stay-at-home orders and six months later [11]. Many youths reported experiencing persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness [12]. Empirical evidence suggests that some youths considered attempting suicide and a minority of youths attempted suicide during the pandemic [12]. Female and gender non-binary youths were especially vulnerable to experiencing negative mental health outcomes [13, 14, 15, 16].

All youths reported similar mental health concerns and challenges during the pandemic, but ethnic-racial minority youths experienced elevated COVID-19–related worry and stress that impacted their well-being [17,18]. Black youths reported that school was a major stressor and source of emotional toll, with many experiencing decreased concentration, reduced motivation, and a lack of focus relative to their academic tasks [19]. Disparities in access to virtual learning resources (e.g., limited internet access, lack of technological resources, lack of quiet spaces to do homework, less adult supervision due to caregivers being essential workers, and attending poorly resourced schools) among Black youths made it difficult for them to adjust academically [19,20]. A qualitative study assessing Black adolescents' experiences with COVID-19 challenges found that these youths also experienced behavioral challenges, such as difficulties with sleep and a lack of interest engaging in daily activities [19]. Youths reported worries with health hygiene (e.g., interacting with large crowds, being around sick people, worries about schools being unsanitary), which were more pronounced among youths who experienced personal losses in their family units [19]. In addition, youths were deeply affected by the lack of interaction with their teachers, friends at school, family members who lived outside of their homes, and their religious/spiritual community [19]. These challenges were further exacerbated by barriers to mental healthcare utilization, which decreased Black youths’ likelihood of receiving treatment for stressors and trauma related to the COVID-19 pandemic [21].

Racial injustice, discrimination, and media during COVID-19

Although ethnic-racial minority youths face higher levels of COVID-19 related stress, racism against Asian communities and the national spike in Black Lives Matter protests in the summer of 2020 against police brutality prompted youths’ awareness toward racism and discrimination, which compounded together to influence their mental health [22]. Adolescents who perceived higher levels of racism and discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially Asian, Black, and multiracial youths, reported poorer mental health outcomes and more difficulty concentrating, remembering, or making decisions [22]. Anti-Asian sentiments surrounding the origins of the virus and the highly publicized recordings of police brutality against Black individuals heightened youths’ anxiety, promoted feelings of othering, and fostered a reduced sense of belonging in these communities [19,23∗, 24∗∗, 25∗, 26∗]. Ethnic-racial minority youths reported anger, frustration, and hopelessness because they lacked resources to enact change against the cyclical nature of racial violence [27].

While adolescents used digital communication to maintain connection among family, friends, and school-related responsibilities, higher screen time increased exposure to racism- and discrimination-related messaging on social media platforms, both personally and vicariously [28]. The murder of George Floyd by police officers was a critical point during the COVID-19 pandemic that led to racial unrest and prompted action to hold police and other perpetrators accountable. Recordings of racial mistreatment, killings, and racial violence inflicted on Black people were shared rapidly across social media platforms. As a result, many adolescents engaged in social media activism to spread solidarity and share resources [27,28]. Although civic engagement has been linked to positive well-being, online racial justice activism also exposes youths to vicarious racial trauma and to an onslaught of racial discrimination via social media. In a study conducted by Tao and Fisher [29], the researchers highlighted how social media operated as both a harmful space for racism to occur and a safe space where youths could seek stress relief against racism and mental health distress. Tao and Fisher also found that adolescents who posted information about racial issues were more likely to report depressive symptoms and alcohol use disorder due to instances of racial discrimination experienced on social media platforms.

COVID-19 discrimination towards Black youths

The COVID-19 pandemic was viewed as a time of racial reckoning, especially surrounding anti-Blackness, police brutality, and COVID-19 disparities [30]. Although research on Black youths' experiences is limited, existing literature suggests that Black youths showed a strong awareness of this racial division and experienced high levels of racism-based stress [19]. A qualitative study by Crooks et al. [24] found that Black youths reported increased media coverage surrounding these injustices, which caused racial tension, anxiety, and distress. Experiencing online racial discrimination affected Black youths’ mental health [31]. Black youths who reported higher exposure to online racial discrimination and online traumatic events reported higher trauma symptoms of discrimination, such as, difficulty relaxing, feeling numb, worrying, discomfort, physiological symptoms, and worries about safety and the future [28]. The link between online racial discrimination and mental health was not fully explained by time spent online or by general cyber victimization experiences [31], suggesting other mechanistic pathways from exposure to online racial discrimination to mental health outcomes.

Some Black youths watched and participated in protests to address systemic and interpersonal injustices, citing their experience of both fear and empowerment [24]. Additionally, Black youths reported having conversations about the racial divide with their family members, which were often emotionally draining, especially for youths from mixed race families [24]. Given that Black youths experienced separations from their social networks, they lost opportunities to utilize their communities to increase understanding about racial tensions [24]. Some youths received opposing messages about Black culture, which increased internalized stigma, negative public regard and private regard and led them to reject parts of their ethnic-racial identities [24]. For other youths, this moment created learning opportunities about culture and history, which increased their confidence and promoted empowerment [24]. This is consistent with a study by Rogers et al. [32], which found that the sociopolitical influence of Black Lives Matter changed youths’ ecological contexts and affected their ethnic-racial identity narratives.

COVID-19 discrimination towards Asian American youths

The COVID-19 pandemic was laced with misinformation and xenophobic sentiments that targeted Asian community members and led to discrimination, which negatively affected Asian American (AA) youths’ mental health. Survey data from a national representative sample of middle and high school students in the U.S. suggest that 82% of AA adolescents experienced COVID-19 related discrimination [33]. Another study found that 25% of AA youths reported higher frequency in the direct experiences of anti-Asian harassment since the beginning of the pandemic [26]. In a study examining cyberbullying before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, AA youths were most likely to report increased victimization during the pandemic. Specifically, 23.5% of AA youths reported being cyberbullied for their race in 2021 compared to 7.4% in 2019 [34]. Furthermore, AA adolescents and young adults who indicated feeling less safe after the pandemic started (76%) were more likely to report increased depression severity and experiences of discrimination since the start of the pandemic [26].

Among Eastern and Southeast Asian American (ESEAA) adolescents, experiences of online and in-person COVID-19 related discrimination predicted higher levels of anxiety, depression, and PTSD symptoms above and beyond lifetime discrimination and previous traumatic events [25,33]. A few studies with Chinese American youths revealed that about half of these youth were directly targeted by COVID-19 racial discrimination online (45.7%) and/or in-person (50.2%); [23,35]. Additionally, youths reported at least 1 incident of COVID-19 vicarious racial discrimination online (76.5%) and/or in-person (91.9%). Experiences of online direct discrimination, online vicarious discrimination, in-person direct discrimination, and sinophobia were negatively associated with youths' psychological well-being and positively associated with anxiety symptoms. Finally, adolescent's experiences of COVID-19 related racial discrimination were associated with more internalizing problems [23].

Resilience and protective processes for ethnic-racial minority youth during the COVID-19 pandemic

Despite experiencing significant challenges and stressors during the COVID-19 pandemic, Black, AA, and other ethnic-racial minority youths received familial and communal support that buffered against the harmful effects of racism, discrimination, and xenophobia. A large body of research points to protective processes such as the promotion of a strong ethnic/racial identity [23,36], parental sharing of ethnic-racial socialization messages [37] and social support from trusted adults, parents, and peers [12,15,38, 39, 40] as buffers against the aversive effects of discrimination on youths’ mental health.

For Black youths, research suggests that social support from family, school personnel, and their religious community and reliance on religious/spiritual coping (i.e., prayer and reading scripture) were pivotal in adjusting to COVID-19 pandemic challenges [19]. Helpful support included one-on-one time with parents, receiving lunch and computers to help students adjust to remote learning, and receiving emotional check-ins from religious youth leaders [19]. Social support and religious/spiritual coping are known adaptive coping mechanisms for the Black American community [41] and played a crucial role in helping adolescents process racial tensions and the widespread protests of the Black Lives Matter movement across the world [19,42]. However, future research should investigate contextual and cultural factors that protect Black youths from racial tension and discrimination during the COVID-19 era.

Empirical evidence found that AA youths relied on their bicultural identity and heritage culture socialization from parents to protect them from internalizing problems and racial discrimination experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic [23,37]. Heritage culture socialization refers to the transmission of messages from AA parents to their children about being proud of their heritage culture, whereas bicultural identity is a phenomenon that speaks to the complex task of integrating values from two different cultures (e.g., Chinese heritage culture and American culture) [23,26]. These cultural assets were central to AA youths’ identities, resilience, and their ability to deal with COVID-19 race-related stress. Overall, cultural factors such as ethnic-racial socialization, ethnic-racial identity, and social support were effective at protecting both Black and AA youths from the harmful effects of discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusion

During the COVID-19 pandemic, ethnic-racial minority youths, families, and communities experienced health disparities and psychosocial stressors at a disproportionate rate. Black and AA youths were uniquely vulnerable due to their experience of COVID-related stressors, vicarious trauma, and racial discrimination. Although COVID-19 challenges were associated with worsened mental health, ethnic-racial minority youths leaned on social support and cultural assets to navigate their circumstances. However, additional research is needed to investigate the structural and social level factors that promote positive health and adaptation among these youths. Health policies should be implemented to provide the institutional support and resources that are needed to combat persistent health disparities and mitigate the impact of structural racism and discrimination on ethnic-racial minority youths’ mental health. Additionally, public policies should provide regulations and protections to shield youths from experiencing online racism and to increase their sense of safety. It is also vital that healthcare providers, community-based organizations, and families help youths process the compounded effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and provide them with culturally relevant coping resources to successfully adapt to their environments.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

We want to give special thanks to one of our excellent undergraduate research assistants, Min Yeung, who wrote the annotated references for the articles we highlighted as of special and outstanding interest.

This review comes from a themed issue on Coming of Age Amid the Pandemic (2024)

Edited by Gabriel Velez and Camelia Hostinar

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- 1.Mackey K., Ayers C.K., Kondo K.K., Saha S., Advani S.M., Young S., Spencer H., Rusek M., Anderson J., Veazie S., Smith M., Kansagara D. Racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19–related infections, hospitalizations, and deaths. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:362–373. doi: 10.7326/M20-6306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goyal M.K., Simpson J.N., Boyle M.D., Badolato G.M., Delaney M., McCarter R., Cora-Bramble D. Racial and/or ethnic and socioeconomic disparities of SARS-CoV-2 infection among children. Pediatrics. 2020;146 doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-009951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maiya S., Dotterer A.M., Whiteman S.D. Longitudinal Changes in adolescents' school bonding during the COVID-19 pandemic: individual, parenting, and family correlates. J Res Adolesc. 2021;31:808–819. doi: 10.1111/jora.12653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rogers A.A., Ha T., Ockey S. Adolescents' perceived socio-emotional impact of COVID-19 and implications for mental health: results from a U.S.-Based Mixed-Methods Study. J Adolesc Health. 2021;68:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scott S.R., Rivera K.M., Rushing E., Manczak E.M., Rozek C.S., Doom J.R. “I Hate This”: a Qualitative analysis of adolescents' self-reported challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Adolesc Health. 2021;68:262–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen C.Y.-C., Byrne E., Vélez T. Impact of the 2020 pandemic of COVID-19 on families with school-aged children in the United States: roles of income level and race. J Fam Issues. 2022;43:719–740. doi: 10.1177/0192513X21994153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Low N., Mounts N.S. Economic stress, parenting, and adolescents' adjustment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Fam Relat. 2022;71:90–107. doi: 10.1111/fare.12623. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hussong A.M., Midgette A.J., Richards A.N., Petrie R.C., Coffman J.L., Thomas T.E. COVID-19 life events spill-over on family functioning and adolescent adjustment. J Early Adolesc. 2022;42:359–388. doi: 10.1177/02724316211036744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Penner F., Hernandez Ortiz J., Sharp C. Change in youth mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in a majority Hispanic/Latinx US Sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;60:513–523. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De France K., Hancock G.R., Stack D.M., Serbin L.A., Hollenstein T. The mental health implications of COVID-19 for adolescents: follow-up of a four-wave longitudinal study during the pandemic. Am Psychol. 2022;77:85–99. doi: 10.1037/amp0000838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosen M.L., Rodman A.M., Kasparek S.W., Mayes M., Freeman M.M., Lengua L.J., Meltzoff A.N., McLaughlin K.A. Promoting youth mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal study. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones S.E., Ethier K.A., Hertz M., DeGue S., Le V.D., Thornton J., Lim C., Dittus P.J., Geda S. Mental health, suicidality, and connectedness among high school students during the COVID-19 pandemic — adolescent behaviors and experiences survey, United States, January–June 2021. MMWR Supplements. 2022;71(3):16–21. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.su7103a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demaray M.K., Ogg J.A., Malecki C.K., Styck K.M. COVID-19 stress and coping and associations with internalizing problems in 4th through 12th grade students. Sch Psychol Rev. 2022;51:150–169. doi: 10.1080/2372966X.2020.1869498. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hawes M.T., Szenczy A.K., Klein D.N., Hajcak G., Nelson B.D. Increases in depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Med. 2022;52:3222–3230. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720005358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luthar S.S., Pao L.S., Kumar N.L. COVID-19 and resilience in schools: implications for practice and policy. Soc Pol Rep. 2021;34:1–65. doi: 10.1002/sop2.16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayne S.L., Hannan C., Davis M., Young J.F., Kelly M.K., Powell M., Dalembert G., McPeak K.E., Jenssen B.P., Fiks A.G. COVID-19 and adolescent depression and suicide risk screening outcomes. Pediatrics. 2021;148 doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-051507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perrigo J.L., Samek A., Hurlburt M. Minority and low-SES families' experiences during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis: a qualitative study. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2022;140 doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2022.106594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stinson E.A., Sullivan R.M., Peteet B.J., Tapert S.F., Baker F.C., Breslin F.J., Dick A.S., Gonzalez M.R., Guillaume M., Marshall A.T., McCabe C.J., Pelham W.E., Van Rinsveld A., Sheth C.S., Sowell E.R., Wade N.E., Wallace A.L., Lisdahl K.M. Longitudinal impact of childhood adversity on early adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in the ABCD study cohort: does race or ethnicity moderate findings? Biological Psychiatry Global Open Sci. 2021;1:324–335. doi: 10.1016/j.bpsgos.2021.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker J.S., Haskins N., Lee A., Hailemeskel R., Adepoju O.A. Black adolescents' perceptions of COVID-19: challenges, coping, and connection to family, religious, and school support. Sch Psychol. 2021;36:303–312. doi: 10.1037/spq0000462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; a. Outstanding interest This article examines the experiences of twelve Black youths between the ages of 12 and 18 years and their perceptions of COVID-19, along with the challenges they faced, coping strategies, and connections to family, religious, and school support, and highlights the importance of cultural and community-based resources in promoting resilience.

- 20.Bogan E., Adams-Bass V.N., Francis L.A., Gaylord-Harden N.K., Seaton E.K., Scott J.C., Williams J.L. “Wearing a mask won't protect us from our history”: the impact of COVID-19 on Black children and families. Soc Pol Rep. 2022;35:1–33. doi: 10.1002/sop2.23. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banks A. Black adolescent experiences with COVID-19 and mental health services utilization. J of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2022;9:1097–1105. doi: 10.1007/s40615-021-01049-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mpofu J.J., Cooper A.C., Ashley C., Geda S., Harding R.L., Johns M.M., Spinks-Franklin A., Njai R., Moyse D., Underwood J.M. Perceived racism and demographic, mental health, and behavioral characteristics among high school students during the COVID-19 pandemic — adolescent Behaviors and Experiences Survey, United States, January–June 2021. MMWR Supplements. 2022;71(3):22–27. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.su7103a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; a. Outstanding interest: This work examines the association between perceived racism and demographics, mental health, and other characteristics among high school students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Researchers found that 69.3% of Asian American students, 55.2% of Black students, and 54.5% of multiracial students who participated in the study reported incidences of racism among US high school students. This work highlights the need for interventions and support to address the negative impact of racism on adolescents' health and well-being.

- Cheah C.S.L., Zong X., Cho H.S., Ren H., Wang S., Xue X., Wang C. Chinese American adolescents' experiences of COVID-19 racial discrimination: risk and protective factors for internalizing difficulties. Cult Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2021;27:559–568. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; a. Special interest: This manuscript highlights the experiences of racial discrimination among 211 Chinese American adolescents, between the ages of 10 and 18 years old, during the COVID-19 pandemic and identifies risk and protective factors for internalizing difficulties.

- Crooks N., Sosina W., Debra A., Donenberg G. The Impact of COVID-19 Among Black girls: a social-ecological perspective. J Pediatr Psychol. 2022;47:270–278. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsab139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; a. Outstanding interest: This qualitative research study provides a social-ecological perspective on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on 25 Black girls (ages 9–18 years old), highlighting themes related to changes they experienced on an individual, interpersonal, institutional, and community level and the resilience and strength used in navigating these challenges.

- Ermis-Demirtas H., Luo Y., Huang Y.J. The impact of COVID-19-associated discrimination on anxiety and depression symptoms in Asian American Adolescents. International Perspectives in Psychol. 2022;11:153–160. doi: 10.1027/2157-3891/a000049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; a. Special interest: This article examines the relationship between COVID-19-associated discrimination (in online and offline settings) and mental health symptoms, and addresses how coping strategies can mitigate the negative effects of discrimination on mental health.

- Huynh J., Chien J., Nguyen A.T., Honda D., Cho E.E., Xiong M., Doan T.T., Ngo T.D. The mental health of Asian American adolescents and young adults amid the rise of anti-Asian racism. Front Public Health. 2023;10 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.958517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; a. Special interest: This empirical article examines the impact of anti-Asian racism due to the COVID-19 pandemic on the health and social issues of 176 Asian American adolescents and young adults (ages 13–17 and 18–29).

- 27.Yeh C.J., Stanley S., Ramirez C.A., Borrero N.E. Urban Education; 2022. Navigating the “Dual pandemics”: the cumulative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and rise in awareness of racial injustices among high school students of color in urban schools. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maxie-Moreman A.D., Tynes B.M. Exposure to online racial discrimination and traumatic events online in Black adolescents and emerging adults. J Res Adolesc. 2022;32:254–269. doi: 10.1111/jora.12732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao X., Fisher C.B. Exposure to social media racial discrimination and mental health among adolescents of color. J Youth Adolesc. 2022;51:30–44. doi: 10.1007/s10964-021-01514-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; a. Special interest: This work investigates the association between exposure to racial discrimination on social media and mental health among adolescents of color (ages 15–18), and suggests that the negative impact of social media racial discrimination on mental health can be mitigated by social support and coping strategies.

- 30.Kishi, Jones September 3). Demonstrations and political violence in America: new data for summer 2020. Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project. 2020 https://acleddata.com/2020/09/03/demonstrations-political-violence-in-america-new-data-for-summer-2020/ [Google Scholar]

- 31.Del Toro J., Wang M.-T. Online racism and mental health among Black American adolescents in 2020. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023;62:25–36.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2022.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rogers L.O., Rosario R.J., Padilla D., Foo C. “[I]t's hard because it's the cops that are killing us for stupid stuff”: racial identity in the sociopolitical context of Black Lives Matter. Dev Psychol. 2021;57:87–101. doi: 10.1037/dev0001130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ermis-Demirtas H., Luo Y., Huang Y.J. The trauma of COVID-19–fueled discrimination: posttraumatic stress in Asian American adolescents. Prof Sch Counsel. 2022;26 doi: 10.1177/2156759X221106814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patchin J.W., Hinduja S. Cyberbullying among Asian American youth before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Sch Health. 2023;93:82–87. doi: 10.1111/josh.13249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheah C.S.L., Wang C., Ren H., Zong X., Cho H.S., Xue X. COVID-19 racism and mental health in Chinese American families. Pediatrics. 2020;146 doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-021816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zong X., Cheah C.S.L., Ren H. Chinese American adolescents' experiences of COVID-19-related racial discrimination and anxiety: person-centered and intersectional approaches. J Res Adolesc. 2022;32:451–469. doi: 10.1111/jora.12696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren H., Cheah C.S.L., Zong X., Wang S., Cho H.S., Wang C., Xue X. Age-varying associations between Chinese American parents' racial–ethnic socialization and children's difficulties during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asian American J of Psychol. 2022;13:351–363. doi: 10.1037/aap0000278. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; a. Outstanding interest: This article examines the age-varying associations between Chinese American parents' racial-ethnic socialization and their children's (ages 4–18) difficulties during the COVID-19 pandemic. The authors highlight the importance of cultural socialization in promoting children's resilience.

- 38.Cohodes E.M., McCauley S., Gee D.G. Parental buffering of stress in the time of COVID-19: family-level factors may moderate the association between pandemic-related stress and youth symptomatology. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology. 2021;49:935–948. doi: 10.1007/s10802-020-00732-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodman A.M., Rosen M.L., Kasparek S.W., Mayes M., Lengua L., Meltzoff A.N., McLaughlin K.A. Social experiences and youth psychopathology during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal study. Dev Psychopathol. 2022:1–13. doi: 10.1017/S0954579422001250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang M.-T., Toro J., Del Scanlon, C L., Schall J.D., Zhang A.L., Belmont A.M., Voltin S.E., Plevniak K.A. The roles of stress, coping, and parental support in adolescent psychological well-being in the context of COVID-19: a daily-diary study. J Affect Disord. 2021;294:245–253. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.06.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim D.H., Harty J., Takahashi L., Voisin D.R. The protective effects of religious beliefs on behavioral health factors among low income African American adolescents in Chicago. J Child Fam Stud. 2018;27:355–364. doi: 10.1007/s10826-017-0891-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Butler-Barnes S.T. “What's going on?” Racism, COVID-19, and centering the voices of Black youth. Am J Community Psychol. 2023;71:101–113. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.