Significance

The enzyme methionine synthase utilizes derivatives of vitamins B12 and B9 to play an essential role in biological methylation chemistry. Deficiencies in methionine synthase have been linked to developmental disorders and other health consequences in humans. Decades of biochemical and structural work on methionine synthase have shown that this enzyme must be highly dynamic, moving its cofactor between three different active sites. In this study, we use a combination of advanced structural methods and structure prediction to provide a wholistic view of the full-length methionine synthase and describe how this flexible enzyme initiates catalysis and switches to its reactivation mode when the enzyme becomes oxidatively inactivated.

Keywords: Enzyme dynamics, SAXS, cryo-EM, one-carbon metabolism, structure prediction

Abstract

Cobalamin-dependent methionine synthase (MetH) catalyzes the synthesis of methionine from homocysteine and 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (CH3-H4folate) using the unique chemistry of its cofactor. In doing so, MetH links the cycling of S-adenosylmethionine with the folate cycle in one-carbon metabolism. Extensive biochemical and structural studies on Escherichia coli MetH have shown that this flexible, multidomain enzyme adopts two major conformations to prevent a futile cycle of methionine production and consumption. However, as MetH is highly dynamic as well as both a photosensitive and oxygen-sensitive metalloenzyme, it poses special challenges for structural studies, and existing structures have necessarily come from a “divide and conquer” approach. In this study, we investigate E. coli MetH and a thermophilic homolog from Thermus filiformis using small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS), single-particle cryoelectron microscopy (cryo-EM), and extensive analysis of the AlphaFold2 database to present a structural description of the full-length MetH in its entirety. Using SAXS, we describe a common resting-state conformation shared by both active and inactive oxidation states of MetH and the roles of CH3-H4folate and flavodoxin in initiating turnover and reactivation. By combining SAXS with a 3.6-Å cryo-EM structure of the T. filiformis MetH, we show that the resting-state conformation consists of a stable arrangement of the catalytic domains that is linked to a highly mobile reactivation domain. Finally, by combining AlphaFold2-guided sequence analysis and our experimental findings, we propose a general model for functional switching in MetH.

Modular, multidomain enzymes catalyze remarkable chemical transformations by moving either their cofactor or substrate over large distances from active site to active site. A classic example is the cobalamin-dependent methionine synthase (MetH) (Fig. 1A), which is responsible for catalyzing methyl transfer from 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (CH3-H4folate) to L-homocysteine (Hcy) to produce H4folate and L-methionine (Fig. 1B, black arrows). In humans, MetH activity is important for preventing elevated homocysteine levels, which are linked to increased risk of cardiovascular diseases and neural tube defects during embryonic development (1–6). Additionally, MetH activity is essential for regenerating H4folate for one-carbon metabolism (1, 7–11), which supports a number of critical processes such as nucleotide biosynthesis in dividing cells (11), as well as for regeneration of S-adenosylmethionine (AdoMet), which is used in a variety of epigenetic methylation processes (12).

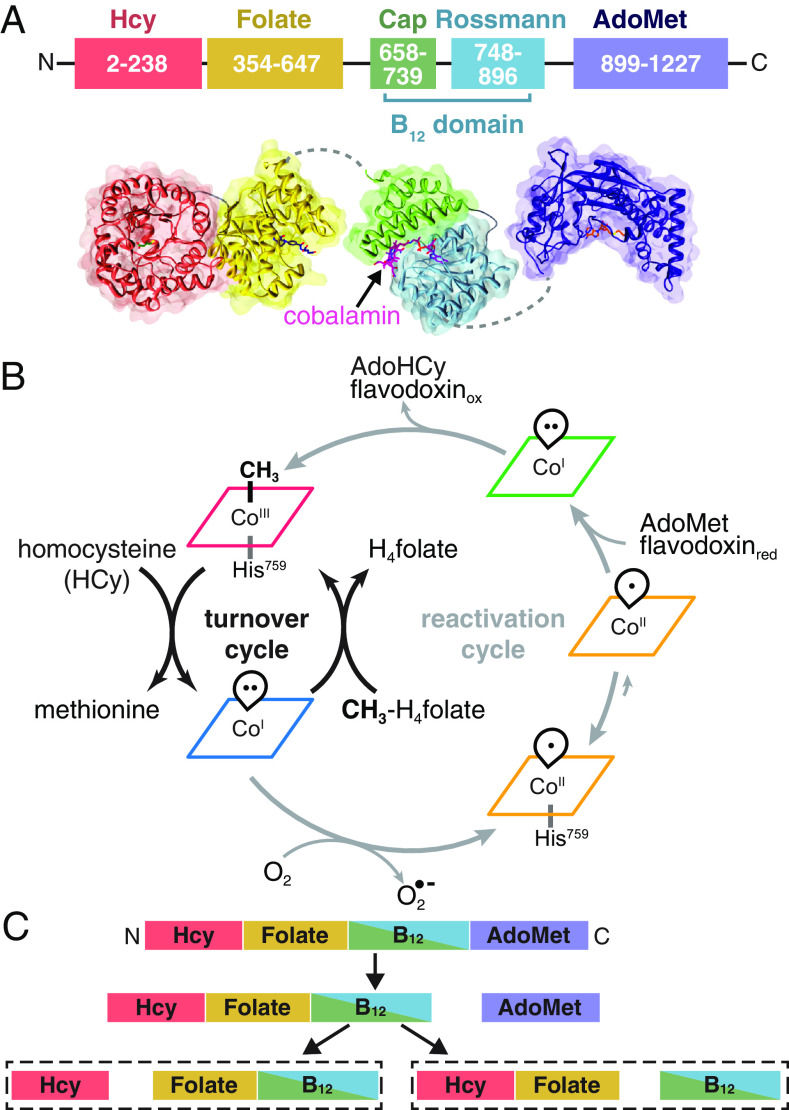

Fig. 1.

Overview of MetH. (A) MetH has a multidomain architecture (shown in E. coli numbering), consisting of four domains, which bind homocysteine (Hcy), 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (CH3-H4folate) (13), cobalamin (B12) (14), and S-adenosylmethionine (AdoMet) (15). The B12 domain additionally consists of the cap and Rossmann subdomains. There is flexibility expected between all the domains except the two N-terminal domains. (B) During normal turnover (black arrows), CH3-Cob(III) enzyme will bind Hcy and CH3-H4folate sequentially, with the latter preferentially binding first (16). Both reactions then proceed in the ternary complex, with the first reaction being methylation of Hcy by CH3-Cob(III) to yield methionine and a reduced Cob(I) intermediate. Methyl transfer from CH3-H4folate to the cofactor then yields H4folate and regenerates CH3-Cob(III). When the Cob(I) cofactor is occasionally oxidized to inactive Cob(II), MetH is able to reactivate via reductive methylation using AdoMet as a methyl donor and an electron from hydroquinone or semiquinone flavodoxin (gray arrows). Cob(II) is predominantly His-on at physiological pH but can interconvert with the His-off state, which is likely to be recognized by flavodoxin. The reactivation cycle proceeds through a distinct, 4-coordinate Cob(I), which is thought to be conformationally gated from normal turnover. (C) Limited trypsin proteolysis produces two different pathways. Cob(II) enzyme in the His-off state or in the presence of flavodoxin proceeds through the right pathway, while all other states proceed through the left (17).

An extensive body of biochemical and structural work by Matthews, Ludwig, and coworkers has provided significant insight into the MetH mechanism, especially for the E. coli enzyme (13–25). The free form of MetH is thought to be in the His-on CH3-Cob(III) (methylcobalamin) oxidation state (16) (Fig. 1B, red), with a conserved histidine (His759 in E. coli numbering) acting as a lower ligand to the central cobalt of the cofactor. In this state, the enzyme is able to transfer the methyl group from its cofactor to Hcy, generating methionine and reducing the cofactor to the Cob(I) oxidation state (Fig. 1B, blue), which is preferentially His-off. The CH3-Cob(III) form of the enzyme is then regenerated by methyl transfer from CH3-H4folate, producing H4folate. Under physiological conditions, MetH is inactivated by oxidation to a predominantly His-on Cob(II) state (Fig. 1B, orange) approximately once every 2,000 turnovers (17). During the reactivation cycle (Fig. 1B, gray arrows), the enzyme is able to reactivate through reductive methylation of the cofactor through electron transfer from reduced flavodoxin and methyl transfer from AdoMet. Binding of flavodoxin favors the dissociation of the His759 ligand in the Cob(II) state (Fig. 1B, orange/His-off), and the enzyme is able to reenter the turnover cycle via a distinct Cob(I) intermediate (19, 22) that is reactive with AdoMet but not with CH3-H4folate (Fig. 1B, green).

Remarkably, the three reactions catalyzed by E. coli MetH imply significant conformational rearrangements of four distinct domains. From the N to C terminus, these domains are known as the Hcy domain, folate domain, B12 domain, and AdoMet or reactivation domain (25) (Fig. 1A). Crystal structures of MetH fragments from various organisms have yielded important mechanistic insight (13–15, 19, 20, 26). The structure of the E. coli B12 domain captured two subdomains in a so-called “cap-on” conformation, with the cobalamin (Fig. 1A, magenta) bound in the Rossmann-fold subdomain (Fig. 1A, cyan) and the upper face covered by a four-helix bundle cap subdomain (14) (Fig. 1A, green). Structures of the two N-terminal domains from Thermotoga maritima (13, 20) MetH revealed a back-to-back double triose-phosphate isomerase (TIM)-barrel architecture (Fig. 1A, salmon/yellow), which suggested that considerable domain motions in the rest of the enzyme are required to shuttle the cobalamin back and forth between the two active sites during turnover. A third active site was visualized in the C-shaped structure of the E. coli AdoMet domain (Fig. 1A, navy). However, despite decades of extensive research, the full-length MetH remained elusive to structure determination because of its flexible “beads on a string” arrangement.

Seminal work by Jarrett et al. has shown that there must be two major conformations of E. coli MetH that enable the enzyme to distinguish its two methyl donors, CH3-H4folate and AdoMet, and electron transfer partner, flavodoxin (17). In this study, it was shown that tryptic proteolysis of E. coli MetH proceeds through two distinct pathways, depending on the cofactor oxidation state and the presence of flavodoxin. In both pathways, the 38-kDa AdoMet domain is the first to be cleaved (Fig. 1C). Intriguingly, subsequent cleavage patterns for the two Cob(I) states, His-on Cob(II) state, and CH3-Cob(III) state were highly similar, with the Hcy domain separating from a fragment that contains both the folate and B12 domains (Fig. 1 C, Left). In contrast, when Cob(II) enzyme was in the presence of flavodoxin or made to be constitutively His-off (via an H759G mutation), the B12 domain was removed from the two N-terminal domains (Fig. 1 C, Right). Spectroscopic studies (27, 28) have shown that although free Cob(II) MetH is predominantly His-on at physiological pH, flavodoxin favors the formation of the His-off state and binds strongly to the H759G mutant. These observations indicated that the second proteolytic pathway must represent a conformation of MetH that is recognized and/or stabilized by flavodoxin and therefore important for reactivation of the cofactor. This so-called “reactivation conformation” was later established by crystal structures of the two C-terminal domains of E. coli MetH, in which a cap-off B12 domain is captured interacting with the active site of the AdoMet domain (18, 19, 21). Because the two N-terminal domains are presumably uninvolved in this conformation, it would make sense that they are cleaved as a single unit when subjected to proteolysis (Fig. 1 C, Right). Together, these findings implied that conformational switching in MetH is governed by the oxidation state of the cobalamin cofactor in some way. Since AdoMet is derived from methionine, such a conformationally gated mechanism would prevent a futile cycle of methionine production and consumption.

In this study, we used a combination of advanced small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS), cryoelectron microscopy (cryo-EM), and extensive exploration of the AlphaFold2 database to report a structural description of full-length MetH and the mechanism by which the enzyme switches functional modes. We show with SAXS that E. coli MetH shares a conformational state in both active and inactive oxidation states and that CH3-H4folate is uniquely able to drive a conformational change even when it is not a reactant. We further show with cryo-EM and SAXS that this shared conformational state is one in which a cap-on B12 domain is nested behind the two N-terminal domains in a “resting state” and the C-terminal AdoMet domain undergoes continuous motion. The cryo-EM model, derived from a thermostable MetH from T. filiformis, provides an explanation for why CH3-H4folate binding undocks the B12 domain, leading to a conformation predicted by SAXS and AlphaFold2, where a cap-off B12 domain interacts with the folate domain. In parallel, we show by SAXS that although the different oxidation states are conformationally indistinguishable, flavodoxin preferentially binds the Cob(II) state. With these results, we propose a model for MetH structural dynamics that is consistent with key biochemical findings. In this model, a stable resting-state conformation is shared between the turnover and reactivation cycles, and the presence of CH3-H4folate triggers a conformational change that initiates turnover, while recognition by flavodoxin recruits Cob(II) MetH into the reactivation cycle.

Results

MetH Oxidation States Share a Conformation in the Absence of Substrates.

Based on prior studies, the full-length E. coli MetH was expected to be highly flexible. We therefore began by comprehensively characterizing this enzyme using SAXS. SAXS is unique in its ability to yield direct structural information on an entire solution conformational ensemble and, when applied carefully, can detect subtle conformational changes in flexible, multidomain proteins (29, 30). To determine how the cobalamin oxidation state correlates with conformation, we compared three representative states of MetH: the CH3-Cob(III) and Cob(I) states from the turnover cycle and the inactive, His-on Cob(II) state from the reactivation cycle (Fig. 1B). In wild-type MetH, the CH3-Cob(III) cofactor is known to be almost entirely His-on over a wide range of solution conditions, while the His-on/off equilibrium in the Cob(II) cofactor is dependent on pH, with the His-on state being predominant at physiological pH (27, 31).

We first performed size-exclusion chromatography-coupled SAXS (SEC-SAXS) to determine the number of distinguishable species in the absence of substrates. E. coli MetH is known to purify as a mixture of physiological and nonphysiological cobalamin oxidation states, including CH3-Cob(III), Cob(II), and OH-Cob(III), from which each physiologically relevant state shown in Fig. 1B can be prepared enzymatically, chemically, or via photolysis (32, 33). SEC-SAXS of as-isolated MetH produces a single elution peak (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). However, singular value decomposition (SVD) of the SEC-SAXS dataset reveals that the peak contains at least three components (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A), two of which are highly overlapped near the center of the peak (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). In contrast, MetH prepared in a single oxidation state predominantly elutes as a single species (SI Appendix, Figs. S1 C and D and S2 A–D). Together, these results indicate that isolating a single oxidation state of MetH also removes the heterogeneity in conformational state that is seen in the as-isolated enzyme.

Having established by SEC-SAXS that MetH prepared in an individual oxidation state cannot be further separated by chromatography (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 C and D), we switched to batch-mode SAXS experiments, which yielded highly similar profiles (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 E and F). Batch mode was ultimately necessary because certain substrates of MetH are not readily available in large enough quantities for use in the running buffer in SEC-SAXS experiments. Additionally, these experiments offered greater control over verifying the integrity of the sample oxidation state. To gain insight into structural differences between oxidation states, we examined the representative states of the full-length E. coli MetH in the absence of substrates in reducing buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, and 2.5 mM DTT). UV-Vis absorption spectra were collected on each sample before and after X-ray exposure to monitor any changes in the cobalamin oxidation state. In reducing buffer, His-on Cob(II) MetH is stable and amenable to standard experimental setups. The integrity of the 5-coordinate, His-on Cob(II) state was verified by the presence of a peak at ~477 nm (28, 32) both before (Fig. 2A, orange) and after (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 B, Inset) X-ray exposure. CH3-Cob(III) MetH, on the other hand, is photosensitive (24) and necessitated a fully darkened experimental hutch, with illumination sources limited to red light. The observation of a broad peak at ~528 nm (28, 32) both before (Fig. 2A, red) and after (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 C, Inset) exposure was an indication that the 6-coordinate, His-on CH3-Cob(III) state did not undergo photolysis or photoreduction. Finally, a fully anoxic setup (34) was required for the highly oxygen-sensitive Cob(I) MetH (16, 32), where the sample loading, pumps, and waste lines were contained in an in-line anoxic chamber at the beamline (SI Appendix, SI Methods). The oxidation state was verified by the characteristic, sharp peak at ~390 nm (28, 32) observed both before (Fig. 2A, blue) and after (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 A, Inset) X-ray exposure.

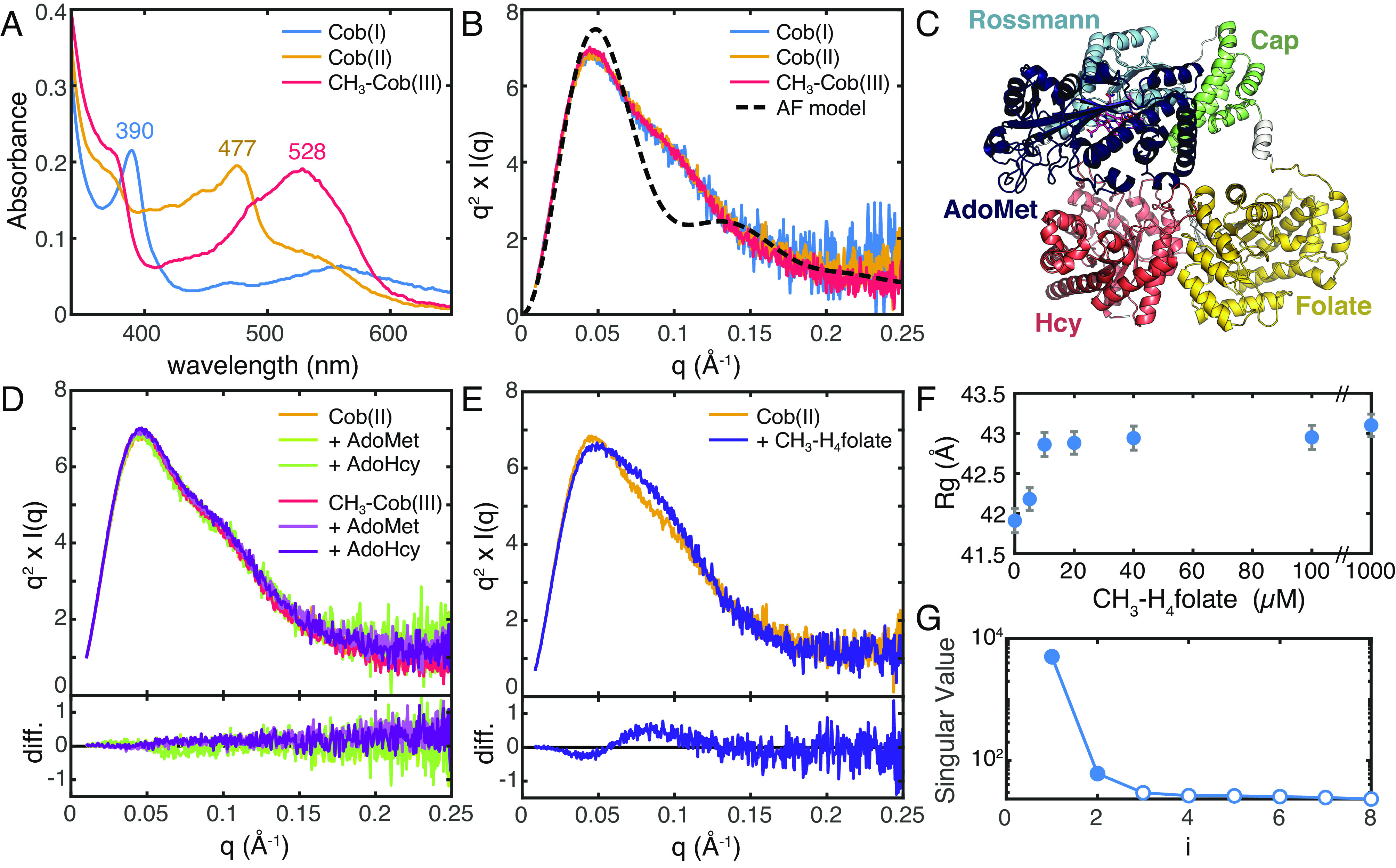

Fig. 2.

SAXS shows that there is a shared conformation of E. coli MetH and that conformational change is driven by CH3-H4folate. (A) UV-Vis absorption spectra of E. coli MetH in the Cob(I) and CH3-Cob(III) states from the turnover cycle (blue and red) and the inactive Cob(II) state (orange) are distinct. (B) SAXS profiles, shown in Kratky representation (q2 × I vs. q), of 20 µM E. coli MetH in the three oxidation states (same colors as in panel A) are indistinguishable. The theoretical scattering from the AlphaFold2 model in panel C (black dashed) displays a much sharper Kratky peak compared to the experimental curves, indicating that in solution, MetH is much more extended and flexible. (C) The AlphaFold2 prediction for full-length E. coli MetH predicts the two C-terminal domains in the reactivation conformation. (D) Addition of reactivation-cycle substrates and products produces no discernable change to the MetH conformation. The top plot shows the Kratky curves, while the bottom shows difference curves. (E) Addition of 1 mM CH3-H4folate [specifically, (6S)-CH3-H4PteGlu3] to Cob(II) MetH results in a widened Kratky peak, indicative of a conformational change to a more elongated structure. The top plot shows the Kratky curves, while the bottom shows difference curves. (F) The conformational change corresponds to a modest increase in the radius of gyration (Rg) with increasing CH3-H4folate concentration. The error bars represent the SD from Guinier analysis. (G) SVD of the titration series shown in panel F suggests a minimally two-state transition.

SAXS profiles were obtained on 20 µM E. coli MetH in the three oxidation states. To facilitate detection of any subtle differences in the enzyme domain arrangement, the scattering is shown in Fig. 2B in Kratky representation: Iq2 vs. q, where I is the scattering intensity, q = 4π/λ sinθ is the momentum transfer variable, 2θ is the scattering angle, and λ is the X-ray wavelength. The Kratky plots for all three states are essentially indistinguishable (Fig. 2B, solid), exhibiting a skewed peak with a maximum at q ~ 0.045 Å−1 and a characteristic subtle shoulder at q ~ 0.11 Å−1 that slowly decays at higher q. In comparison, the theoretical Kratky plot of an AlphaFold2 (35) model of the full-length E. coli MetH (Fig. 2C) displays a much sharper peak at q ~ 0.05 Å−1 (Fig. 2B, dashed). The slow decay at high q seen in the experimental Kratky plots indicates that in solution, MetH samples conformations that are more extended and flexible than that captured by the AlphaFold2 model. Consistent with this, the experimental Rg values obtained by Guinier analysis range between ~40 and 42 Å (SI Appendix, Table S2), which is significantly larger than the theoretical Rg value of 35.2 Å for the AlphaFold2 model. These larger Rg values are not due to oligomerization. Based on Porod volumes (VP) calculated from the SAXS profiles, the molecular weights of the CH3-Cob(III), Cob(II), and Cob(I) states are estimated to be 138.4, 138.9, and 142.1 kDa, respectively, consistent with monomeric MetH (actual molecular weight of holoenzyme = 137.2 kDa). We note that Cob(II) and Cob(I) MetH have slightly higher apparent Rg values and maximum dimensions (Dmax) than CH3-Cob(III) MetH (SI Appendix, Table S2 and Fig. S3). These small differences are not particularly meaningful as the SAXS profiles overlay almost exactly and are instead attributed to small amounts of additional aggregate resulting from the chemical preparation of those states from the CH3-Cob(III) enzyme. Most importantly, these results suggest that MetH is flexible in solution and that in the absence of substrates, the different oxidation states are likely to share a conformation or set of conformations. This observation provides a long-sought explanation for why these oxidation states share a proteolytic pathway (Fig. 1 C, Left) (17).

Conformational Changes Are Driven by CH3-H4folate.

It was previously shown by UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy that the interconversion of His-on and His-off states of the cobalamin cofactor can be modulated by substrates and products in a mutant of E. coli MetH where the His-on state is destabilized (31). To test whether these substrates and products can shift the conformational distribution of wild-type E. coli MetH, we examined two representative states of the turnover and reactivation cycles, namely the His-on Cob(II) and CH3-Cob(III) states, in reducing buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, and 2.5 mM DTT) using batch-mode SAXS. A maximum substrate concentration of 1 mM was chosen to match previously reported experiments and to saturate binding based on known dissociation constants (16, 17, 31) (SI Appendix, SI Methods).

We first examined the effects of the substrate and product pair, S-adenosyl-L-methionine (AdoMet) and S-adenosylhomocysteine (AdoHcy), from the reactivation cycle. Incubation of 20 µM CH3-Cob(III) or Cob(II) E. coli MetH with either 1 mM AdoMet or AdoHcy produced no appreciable change in the SAXS profiles relative to the substrate-free enzyme (Fig. 2D and SI Appendix, Fig. S4 A and B). Likewise, we examined the substrate and product pair, homocysteine (Hcy) and methionine (Met), from the turnover cycle. Incubation of Cob(II) enzyme with either 1 mM Met or Hcy again led to identical profiles as the substrate-free enzyme (SI Appendix, Fig. S4C). The CH3-Cob(III) enzyme was tested only in the presence of 1 mM Met as Hcy would rapidly react with the enzyme, but again, no change in scattering was observed (SI Appendix, Fig. S4D).

To examine the effects of CH3-H4folate, we used the triglutamate form (6S)-CH3-H4PteGlu3, which was used in the original study by Jarrett et al. for its high binding affinity to E. coli MetH (KD = 0.4 µM) (17). Interestingly, when Cob(II) enzyme was incubated with CH3-H4PteGlu3, a clear change in scattering was observed (Fig. 2E). Titration of 0 to 1 mM CH3-H4PteGlu3 into 20 µM Cob(II) MetH led to the appearance of a shoulder on the Kratky peak at q ~ 0.09 Å−1 (Fig. 2E and SI Appendix, Fig. S5A), indicative of a conformational rearrangement that is more elongated than the substrate-free enzyme. Consistent with this interpretation, there is a shift in the pair distance distribution, P(r), toward a shape that is more consistent with an elongated species (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B). This change was accompanied by a modest increase in the Guinier Rg, from 41.9 ± 0.2 Å in the absence of substrates to 43.1 ± 0.1 Å after incubation with 1 mM CH3-H4PteGlu3 (Fig. 2F and SI Appendix, Fig. S5D and Table S3). SVD of the titration series suggested a minimally two-state transition (Fig. 2G). Addition of CH3-H4PteGlu3 to CH3-Cob(III) MetH resulted in an identical change (SI Appendix, Fig. S5C), although the enzyme was unavoidably reduced to Cob(II) enzyme during the experiment (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 C, Inset), either by photolysis from an unknown remaining light source or by photoreduction by the X-ray beam itself (21, 24), and thus, the resulting scattering likely represents that of a mixture of oxidation states, if not of pure Cob(II) enzyme. Nonetheless, these results are significant for several reasons. Of the many conditions we tested, CH3-H4PteGlu3 was the only ligand that induced a detectable conformational change, despite the fact that it is not a substrate for either the Cob(II) or CH3-Cob(III) enzymes. This suggests that CH3-H4PteGlu3 is generally responsible for driving conformational change in MetH. Such an interpretation is in line with previous steady-state kinetics results that show that the primary turnover reaction involves an ordered sequential mechanism, which is driven by CH3-H4folate preferentially binding first in the ternary complex (16). Furthermore, we found that CH3-Cob(III) MetH reduces to Cob(II) in the X-ray beam when CH3-H4PteGlu3 is bound but not in the absence of substrates or in the presence of AdoMet, AdoHcy, or Met. This result is consistent with previous studies that observed enhanced photolysis rates of the CH3-Cob(III) cofactor upon addition of CH3-H4folate (24) and suggests that the conformational change induced by this substrate involves the uncapping of the B12 cap domain, which normally acts to sequester the methyl radical produced by the homolysis of the methylcobalamin Co–C bond. This, in turn, indicates that there exists a resting state of MetH, in which the B12 domain is capped.

Flavodoxin Binding Is Specific to the Cobalamin Oxidation State.

Our SAXS data thus far suggest that both turnover and reactivation states of MetH share a so-called cap-on resting-state conformation that undergoes a similar response to CH3-H4folate. To gain insight into what initiates the reactivation cycle, we examined complex formation between MetH and flavodoxin using SAXS. Although flavodoxin binding to the Cob(II) enzyme is relatively weak at near physiological pH (KD ~ 46.5 µM at pH 7.0), extrapolation of pH-dependent data (27) suggests that complex formation should be readily discernable by SAXS around pH 6 at MetH concentrations consistent with our other experiments.

Exchanging CH3-Cob(III) and Cob(II) MetH into reducing buffer at pH 6 (44 mM Na/K phosphate, pH 6.0, and 1 mM DTT with the ionic strength adjusted to 0.15) leads to SAXS profiles that are highly similar to those obtained at pH 7.6 (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 A and B). The subtle pH-dependent change in Cob(II) scattering at q ~ 0.045 Å−1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S6B, arrow) may reflect a slight increase in His-off population (which has an absorbance peak at 465 nm) (27) at pH 6, as indicated by the slight shift in the absorbance peak from 477 to 472 nm (SI Appendix, Fig. S6C). Despite minor differences in the scattering of free CH3-Cob(III) and Cob(II) MetH, markedly different behavior is observed when the enzyme is mixed with flavodoxin (Fig. 3 A and D). Addition of 0 to 60 µM E. coli flavodoxin to 20 µM Cob(II) MetH in reducing buffer leads to an increase in the apparent Guinier Rg value until approximately the equimolar point, followed by a decrease in Rg (Fig. 3B and SI Appendix, Table S4). The initial increase in Rg is consistent with complex formation, while the subsequent reduction in apparent Rg can be explained by excess amounts of the titrated protein. In agreement with this interpretation, SVD of the titration series (Fig. 3C) indicates a minimally three-component mixture, likely corresponding to free MetH, MetH:flavodoxin complex, and free flavodoxin. By contrast, when flavodoxin is titrated into 20 µM CH3-Cob(III) MetH, the observed behavior is a steady decrease in the Guinier Rg value (Fig. 3E and SI Appendix, Table S5). SVD of the titration series suggests a minimally two-component system (Fig. 3F), which when taken with the steady decrease in Rg, indicates a lack of complex formation.

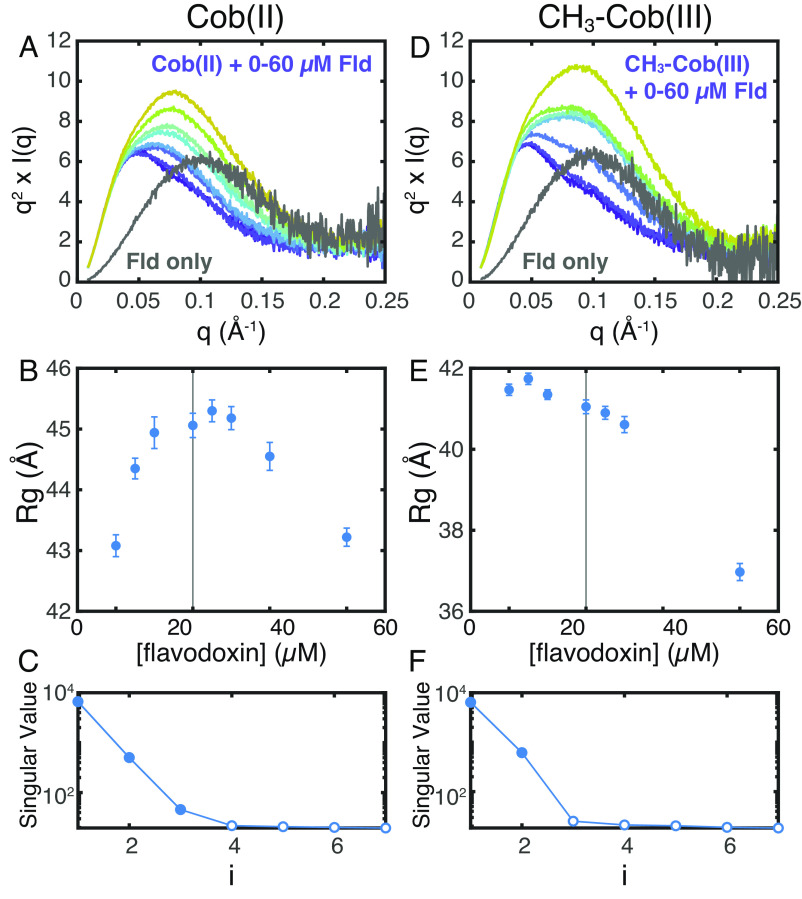

Fig. 3.

SAXS shows that flavodoxin discriminates between E. coli MetH oxidation states. (A–C) Titration of 0 to 60 µM E. coli flavodoxin (Fld) into 20 µM Cob(II) E. coli MetH at pH 6.0 produces behavior consistent with complex formation and saturation. (A) Kratky curves for the titration series are shown in color (navy, 0 µM Fld, to yellow, 60 µM Fld), while that of pure Fld is shown in gray. (B) The apparent Guinier Rg of the mixture increases to near the equimolar point (vertical line), indicative of complex formation, followed by a decrease due to excess Fld (the Rg of free Fld is ~18 Å). (C) SVD of the titration series shown in panel Fld suggests a minimally three-component system, consistent with the two proteins as well as a complex of the two. (D–F) By contrast, titration of 0 to 60 μM Fld into 20 μM CH3-Cob(III) MetH indicates a lack of complex formation. (D) Kratky curves for the titration series are shown in color (navy to yellow), while that of pure Fld is shown in gray. (E) The apparent Guinier Rg of the mixture decreases with increasing Fld, indicating that the two proteins do not interact. (F) SVD of the titration series shown in panel D suggests a minimally two-component system, consistent a mixture of two noninteracting proteins.

These SAXS results clearly demonstrate that flavodoxin binds specifically to Cob(II) MetH but not CH3-Cob(III) MetH. In our experiment, both enzyme states were predominantly His-on before addition of flavodoxin. It is known, however, from spectroscopy and crystallography that binding of flavodoxin to Cob(II) MetH promotes the lower His759 ligand of the cofactor to dissociate (17, 27) and that in the reactivation conformation, His759 instead interacts with Glu1069 and Asp1093 in the AdoMet domain, stabilizing the interaction of the two C-terminal domains (21). Combined with these previous observations, our results indicate that flavodoxin recognizes the oxidation state of MetH in which His759 readily dissociates from the cobalamin cofactor, which is the case for Cob(II) but not CH3-Cob(III). This in turn suggests that although the turnover and reactivation cycles share a resting-state conformation, the Cob(II) enzyme can enter the reactivation cycle through recognition by flavodoxin, which is always present in vivo.

Cryo-EM Structure of Methionine Synthase Represents a Resting State.

To gain higher-resolution insight, cryo-EM experiments with His-on Cob(II) and CH3-Cob(III) E. coli MetH were performed extensively both in the absence and presence of CH3-H4folate. However, these experiments were continually hampered by the destabilizing environment of the air–water interface (36), likely due to the well-known instability of the B12 domain in the E. coli enzyme (32). To overcome these issues, we calculated a sequence similarity network (SSN) of 8,047 MetH sequences and identified several homologous sequences from thermophiles both within the same SSN cluster as the E. coli enzyme and elsewhere (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Of the three sequences that we tested, we found that Thermus filiformis MetH (33% sequence identity and 53% sequence similarity to E. coli) was stable enough that it could be purified in the apo form and later be reconstituted with the cobalamin cofactor (SI Appendix, SI Methods), suggestive of a more stable B12 domain fold than the E. coli enzyme. SAXS profiles of 20 µM Cob(II) T. filiformis MetH in the absence and presence of 1 mM (6S)-CH3-H4PteGlu3 are superimposable with the E. coli counterparts (SI Appendix, Fig. S8), indicating that the two enzymes behave similarly. Single-particle cryo-EM was then performed (SI Appendix, Figs. S9 and S10 and Tables S7 and S8). To address severe orientation bias seen in screening datasets and to stabilize very thin ice at the hole centers, T. filiformis MetH was vitrified concurrently with equimolar horse spleen apoferritin, which ameliorated both issues. As apoferritin is comparable in size to MetH (as suggested by SAXS Dmax) and is known to rapidly denature at the air–water interface (37), we attribute this improvement to apoferritin creating sacrificial denatured layers at the interfaces and potentially also acting as a physical support. We note however that addition of apoferritin did not help with cryo-EM attempts of E. coli MetH, and thus, the intrinsic stability of the T. filiformis enzyme appears to be the most important factor.

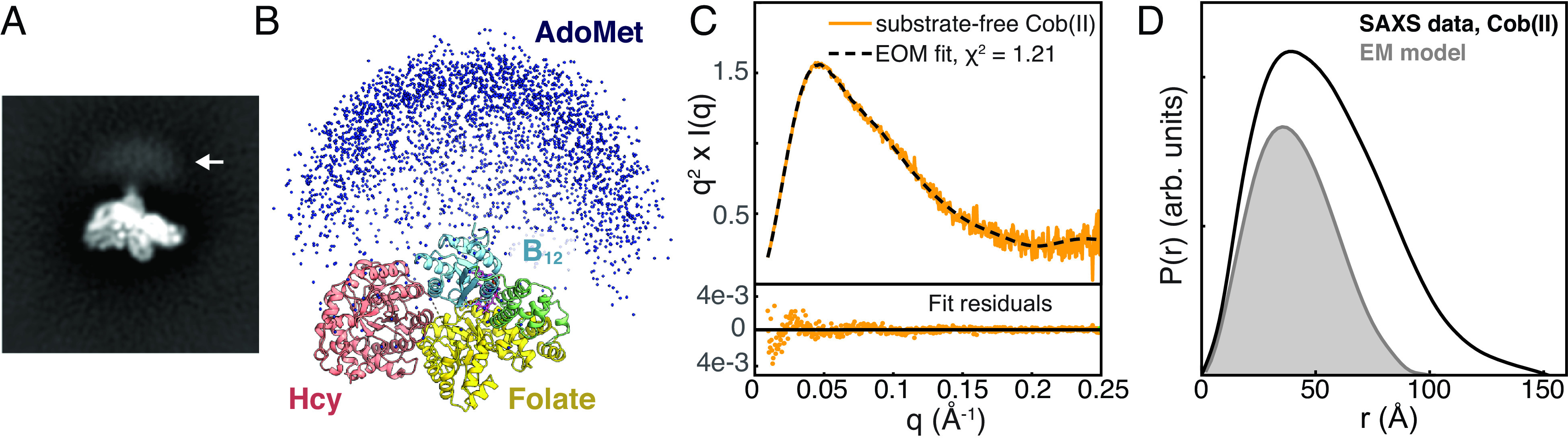

With this strategy, we ultimately obtained an accurate view of the intact, full-length T. filiformis MetH in the substrate-free Cob(II) state. 2D classes revealed clear secondary structure elements for the three N-terminal domains and blurry contrast for the C-terminal AdoMet domain (Fig. 4A). These data gave rise to a 3.6-Å resolution consensus map of the three N-terminal domains (Fig. 4 B and C, PDB 8G3H), while additional analyses (discussed in detail in the next section) demonstrated that the C-terminal AdoMet domain is highly dynamic in this state (Fig. 5). The consensus map reconstruction represents the first structure of more than two domains of MetH in any state—a description that has remained elusive despite almost three decades of structural studies. Although the map exhibits some resolution anisotropy (SI Appendix, Fig. S10D), the overall resolution and detail of the map allowed for unambiguous placement of the individual protein domains as well as the cobalamin cofactor and the catalytic zinc ion in the Hcy-binding domain (SI Appendix, Table S8). Overall, the subconformation of the two N-terminal domains is similar to previous fragment structures of Thermotoga maritima (13, 20) and human MetH (unpublished, PDB 4CCZ) (SI Appendix, Fig. S11 A, Bottom), where the N-terminal domains appear to adopt a rigid platform with the two active sites pointing away from each other. Additionally, the B12 domain adopts a highly similar overall conformation to the published fragment structure of the E. coli B12 domain [PDB 1BMT (14), SI Appendix, Fig. S11 A, Top]. In this conformation, the four-helix bundle cap subdomain sits atop the cobalamin cofactor, likely serving to protect it from solvent and against unwanted reactivity. Moreover, our cryo-EM map supports a conformation in which His759 is stabilized by Asp757 to axially coordinate to the cobalt of the cobalamin cofactor, much like that observed in the previous fragment structure (14) (SI Appendix, Fig. S12). It is notable that a Cob(II) MetH gave an identical B12 domain conformation to the crystal structure of the E. coli fragment (14), which contained the CH3-Cob(III) form of the cofactor. This observation is consistent with our SAXS studies which suggest that the different oxidation states of MetH share a conformational state.

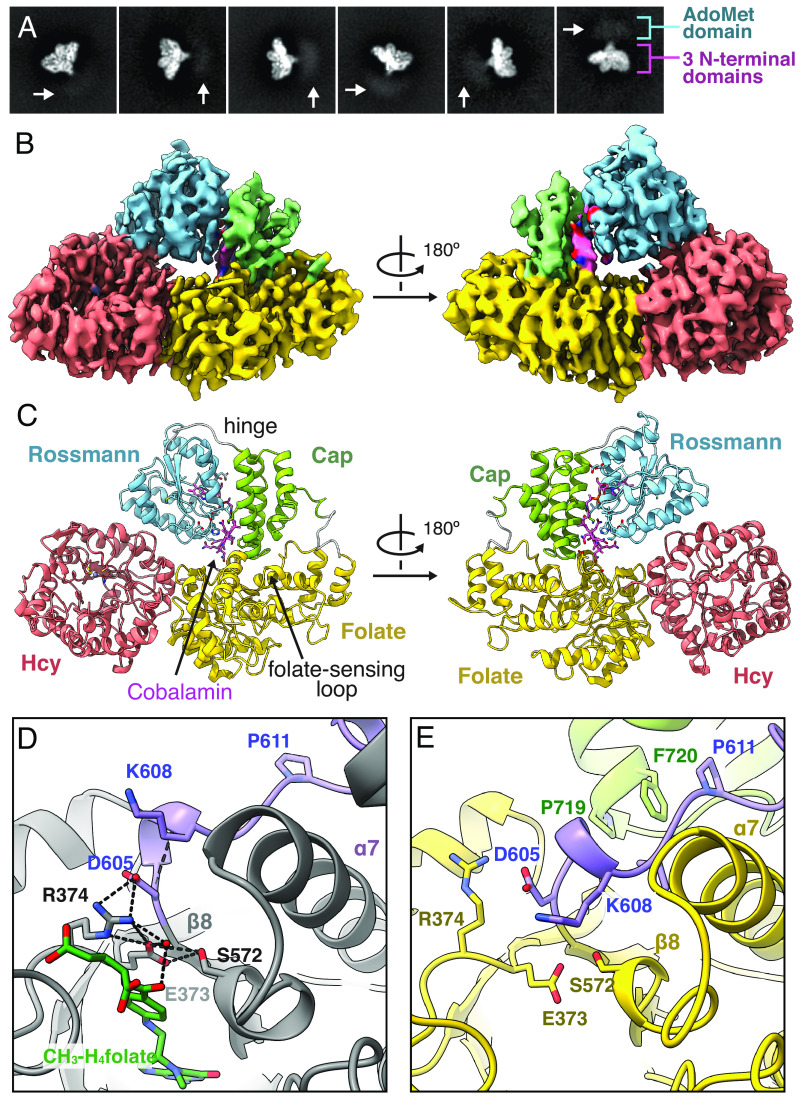

Fig. 4.

Cryo-EM of T. Filiformis MetH reveals a resting-state conformation poised for folate sensing. (A) 2D classes of Cob(II) T. filiformis MetH depicts the full-length enzyme. (B) The 3.6-Å consensus reconstruction contains the three N-terminal domains: the Hcy, folate, and B12 domains (PDB 8G3H, EMD-29699). The map is colored by domain assignment and shown at a threshold level of 0.3. (C) Residues 23–877 along with the cobalamin and zinc cofactors were built into the consensus map. The model suggests that this conformation represents a resting state of the enzyme, where the B12 domain is in the cap-on conformation and nested between the Hcy and folate domains. (D) In a fragment structure of the folate domain from T. thermophilus MetH (PDB 5VOO) (26), residues on the loop (purple) that extends past the C terminus of the folate-domain β8-strand (specifically, D605 and K608, shown in T. filiformis numbering for clarity) are oriented to help stabilize binding of CH3-H4folate through water-mediated interactions with the p-aminobenzoate moiety. The methyl group makes no interactions with MetH. (E) In our cryo-EM structure, this folate-sensing loop (purple) is pushed toward the folate-binding site by interactions with the cap subdomain (green). The competition between the cap subdomain and CH3-H4folate for the folate-sensing loop provides a structural basis for folate-driven disruption of the resting-state conformation and resulting conformational changes. Both hydrophobic and polar interactions are involved in stabilizing this closed conformation of the folate-binding loop (SI Appendix, Figs. S13 and S14), and although the loop is colored in purple for contrast, it is part of the folate domain (SI Appendix, Fig. S15).

Fig. 5.

Combining cryo-EM with ensemble modeling of SAXS data shows that the AdoMet domain is highly flexible in the resting state of full-length MetH. (A) Blurry density is visible past the C terminus of the B12 domain in reference-free 2D classes of T. filiformis MetH shown in Fig. 4A (arrow). (B) A large ensemble of E. coli MetH structures was generated in EOM (38, 39) by treating the three N-terminal domains in the conformation observed by cryo-EM and the C-terminal AdoMet domain as two independent, flexibly-linked rigid bodies. Plotting the position of the AdoMet domain in each of the 10,000 models (blue spheres) produces a qualitatively similar distribution to the blurry density seen in the 2D classes in panel A. (C) The substrate-free Cob(II) E. coli MetH SAXS data from Fig. 2B (orange) can be described very well by a minimal ensemble selected by EOM (38, 39) (dashed). (D) Comparison of the pair distance distribution, P(r), calculated from the SAXS data shown in panel C (black) to the theoretical P(r) generated from an E. coli model of the three N-terminal domains derived from the cryo-EM structure (gray) indicates that many of the large interparticle distances are not fully described by the EM model alone, indicating that the AdoMet domain samples many extended conformations. The P(r) functions were normalized by dividing by I(0)/MW2, where I(0) is the forward scattering intensity, and MW is the molecular weight.

Interestingly, the state captured by cryo-EM appears to represent a stable resting state of MetH. We observe the B12 domain tucked at the interface of the Hcy and folate domains (Fig. 4C) such that the cofactor is sequestered from the active sites of both N-terminal domains. The cap subdomain of the B12 domain interacts with the folate domain through a combination of hydrophobic and polar contacts (SI Appendix, Figs. S13 A and B and S14 A), while the Rossmann subdomain binds the Hcy domain primarily through polar interactions (SI Appendix, Fig. S13 C and D). The positioning of the two subdomains places N24 of the cobalamin cofactor within the hydrogen-bonding distance of Thr366 on the folate domain. The interaction between the cap subdomain and folate domain is of particular interest because it involves a structural element that is not typically seen in a canonical β8ɑ8 TIM barrel. In a canonical TIM barrel, the β8-strand connects via a loop to the ɑ8-helix, which completes the barrel structure (SI Appendix, Fig. S15A). However, the MetH folate domain has been shown to adopt a β8ɑ7 barrel topology, in which the loop from the β8-strand extends past the barrel wall and is terminated by a set of ɑ8′-helices outside of the barrel (SI Appendix, Fig. S15B). Comparison of our cryo-EM structure with fragment structures of the folate domain (26) reveals that this loop (residues 603–612 in T. filiformis MetH) is in fact part of the active site (Fig. 4D, blue loop) and that CH3-H4folate and the B12 cap subdomain must compete for interactions with this loop (Fig. 4 D and E, blue loop). Thus, the loop acts to sense the presence of CH3-H4folate, and binding of this substrate necessarily causes the B12 cap subdomain to undock from its resting-state position. In our structure, we observe hydrophobic interactions, including a favorable aromatic–proline stacking interaction between Phe720 on the cap domain and Pro611 in the folate-sensing loop, as well as polar interactions between Gln717 at the tip of the cap domain and Asp592 in the ɑ7-helix of the folate domain (SI Appendix, Fig. S14A). In E. coli MetH, the positions of the Phe and Gln residues are flipped. Interestingly, analysis of the 4-domain MetH sequences in our SSN shows that the majority can be classified into either T. filiformis-like or E. coli–like Q/F positioning in the cap domain. In T. filiformis–like sequences, Pro611 is highly conserved, while the residue at 592 is almost always one that can form a polar interaction with Gln (SI Appendix, Fig. S14B). Further sequence analysis and examination of other AlphaFold2 models in the resting-state conformation show that in E. coli–like sequences, Gln is positioned to form polar interactions with the backbone of the folate-sensing loop, while the ɑ7-helix of the folate domain contains highly conserved hydrophobic residues that can serve to conserve the overall interactions seen in the T. filiformis structure (SI Appendix, Fig. S14 C and D). The conservation of overall interactions would explain why T. filiformis and E. coli MetH behave similarly in the absence and presence of CH3-H4folate. Together, these interactions serve to “lock” the B12 domain in the cap-on conformation and sequester the cofactor from any reactivity.

The discovery of the resting-state conformation was unexpected, as interactions between the B12 domain and other MetH domains had not been predicted except during turnover or reactivation, when the cofactor must interact with the substrate-binding sites to facilitate methyl transfers. However, this resting-state conformation explains why limited proteolysis of MetH in any oxidation state first leads to a 98-kDa fragment containing the first three N-terminal domains (17). Moreover, the interactions we observed between the cap subdomain and the folate domain explain why they remain associated in one of the proteolysis pathways (17) (Fig. 1 C, Left). Finally, our cryo-EM model explains how binding of CH3-H4folate can drive a conformational change from the resting-state conformation.

Combining Cryo-EM and SAXS Yields a Dynamic View of the Resting State.

Although the consensus map of the resting state lacks the AdoMet domain, blurry contrast is visible past the C terminus of the B12 domain in the cryo-EM 2D classes (Fig. 5A) that is suggestive of this domain undergoing significant motions. Consistent with this interpretation, swinging motion of the linker region is observed by 3D variability analysis in CryoSPARC (40) (Movie S1). However, because the AdoMet domain is very small (~38 kDa) and mobile, it cannot be reconstructed by conventional methods.

To probe the flexibility of the AdoMet domain, we combined the cryo-EM consensus model with SAXS data using a coarse-grained ensemble modeling approach known as ensemble optimization method (EOM) (38, 39). As much more is known biochemically about E. coli MetH than T. filiformis MetH, we chose to fit our models to the E. coli SAXS datasets. A resting-state model for E. coli MetH was built by aligning AlphaFold2 models for the three N-terminal domains to the cryo-EM consensus model of T. filiformis MetH. This model (consisting of residues 3–896) and a crystal structure of the E. coli AdoMet domain [residues 901–1,227, from PDB 1MSK (15)] were treated as two independent rigid bodies connected by a 4-residue flexible linker. A coarse-grained ensemble of 10,000 structures sampling a wide range of conformational space was generated using the program RANCH (38, 39) (Fig. 5B). A subset (i.e., a minimal ensemble) that provides the best fit to our experimental SAXS data was determined using a genetic algorithm implemented in the program GAJOE (38, 39). With this approach, we find that a minimal ensemble derived from the cryo-EM resting-state conformation and a flexibly linked AdoMet domain is able to describe our substrate-free Cob(II) SAXS data very well (Fig. 5C).

The qualitative similarity of the 10,000 AdoMet domain positions in the starting EOM pool (Fig. 5B) and the blurry contrast in the 2D classes (Fig. 5A) suggests that the ensemble captured by cryo-EM samples an extremely wide range of conformational space. In EOM, the flexibility of the selected ensemble is assessed by Rflex, which is 100% for a fully flexible system and 0% for a fully rigid system. By convention, the flexibility of the starting (i.e., random) ensemble is given in parentheses. For the EOM fit to the substrate-free Cob(II) SAXS data, Rflex (random) is 84.80% (~89.73%), indicating that the selected ensemble represents a highly flexible system, having almost the same degree of the flexibility seen in the original structural pool. Additionally, comparing the experimental real-space SAXS distance distribution function, P(r), to one generated from the EM-based model (E. coli sequence) of the three N-terminal domains (Fig. 5D) shows that a large fraction of the interparticle distances is not well described without the AdoMet domain. Taken together, these results are consistent with a resting-state model for the full-length MetH, in which the linker to the AdoMet domain is highly flexible, as suggested by CryoSPARC 3D variability analysis (40) (Movie S1). That this domain could act almost as an independent protein is not surprising. In fact, in some species of bacteria including T. maritima, the AdoMet domain is a separate polypeptide chain entirely (41), suggesting a minimal penalty for largely independent functions of the catalytic domains and the reactivation domain.

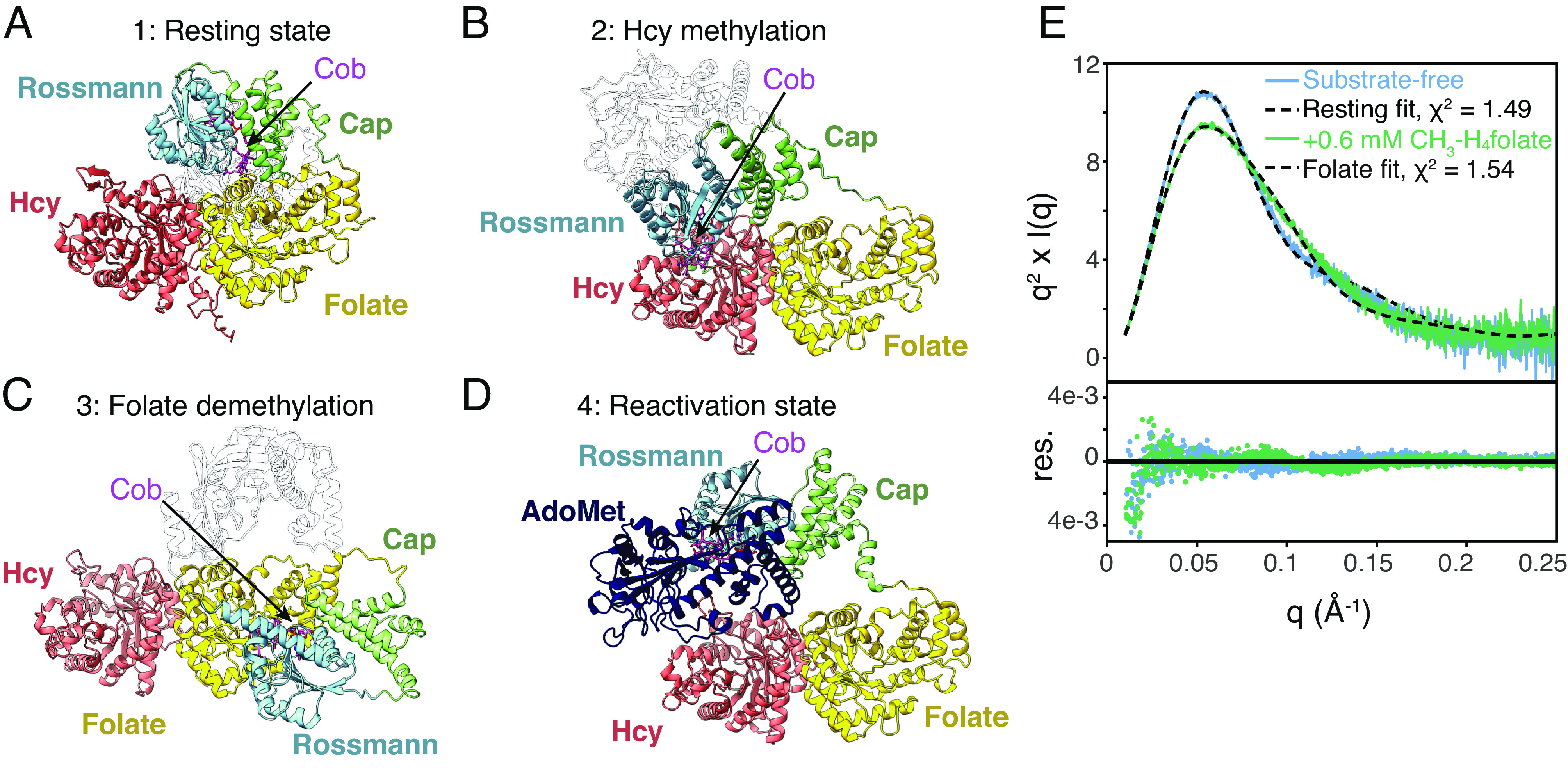

A Model for Conformational Change in MetH.

As structure prediction continues to improve with the advent of AlphaFold2 (35) and RoseTTAFold (42), our avenues for structural interpretation and validation continue to expand. In the case of MetH, the vast majority of public AlphaFold2 database models (2,992 out of 4,915 4-domain sequences) represent the reactivation conformation (Figs. 2C and 6D), in which the B12 domain is uncapped and interacting closely with the AdoMet domain. This is not unexpected, as all available crystal structures of the two C-terminal domains of the enzyme adopt this conformation (18, 19, 21), and machine learning enforces agreement with existing structures in the training dataset. Interestingly, however, the most recent public rank-0 model of the T. filiformis enzyme is strikingly similar to our observed cryo-EM resting-state model (Cα RMSD = 2.5 Å for the three N-terminal domains, Fig. 6A and SI Appendix, Fig. S11B), although older versions of the database provided models in the reactivation conformation. In fact, running AlphaFold2 locally on the T. filiformis sequence without the AdoMet domain results in all 5 ranked models adopting a domain arrangement similar to the experimentally observed resting state. Moreover, of the 4,915 MetH sequences in the public AlphaFold2 database with AdoMet domains, 212 are predicted to be in a resting-state conformation with the Rossmann domain within 2.5 Å Cα RMSD of the cap-on fragment structure (1BMT) (14) (SI Appendix, Fig. S16A). This is an astonishing result, especially given that the prediction lacks the cobalamin cofactor.

Fig. 6.

Structure prediction and removal of the AdoMet domain disambiguates the conformational change caused by CH3-H4folate. (A) The most recent AlphaFold2 model for T. filiformis MetH predicts a conformation highly similar to the resting state observed in cryo-EM. (B) The AlphaFold2 model for Mus musculus MetH predicts a conformation similar to what would be expected to be competent for homocysteine methylation. (C) The AlphaFold2 model for a Sphaerochaeta sp. (Uniprot A0A521IQ66) predicts a conformation similar to what would be expected to be competent for folate demethylation. (D) The AlphaFold2 model for E. coli MetH predicts the C-terminal half of the enzyme in the reactivation conformation. This conformation is the most common conformation predicted among AlphaFold2 models, likely due to the prevalence of reactivation-state structures in the PDB. Models from across multiple species suggest that the N- and C-terminal halves do not interact. (E) A fragment containing only the three N-terminal domains of Cob(II) E. coli MetH was produced by tryptic proteolysis. The Kratky plot for this fragment (at 23 µM) displays a sharp peak (blue), indicating that removal of the AdoMet domain leads to a compact structure. Incubating the fragment with 0.6 mM CH3-H4folate leads to a change in scattering (green), indicating that folate-driven conformational change occurs within the three N-terminal domains. The model based on the cryo-EM resting state describes the substrate-free data well (blue/dashed), while a model based on that shown in panel C describes the folate-incubated Cob(II) data well (green/dashed). For panels A–C, the AdoMet domain has been rendered transparent for clarity, and for all models, the cobalamin ligand (magenta) has been docked into the structure by aligning the 1BMT (14) structure to the cobalamin-binding loop of each model.

Based on the success of AlphaFold2 to predict a conformation that was observed experimentally for the first time in this study, we analyzed all 4,915 publicly available models (SI Appendix, SI Methods). Notably, a number of models appear to adopt a conformation similar to what would be expected during homocysteine methylation, i.e., with the binding face of the Rossmann subdomain situated above the barrel opening in the Hcy domain. These include models of the 3-domain T. maritima and 4-domain Mus musculus enzymes (Fig. 6B). In the case of the M. musculus MetH model, cobalamin can be docked in without introducing serious steric clashes, placing the cofactor in a position that would put the cobalt in reasonable proximity to the homocysteine thiol. Of the 4,915 publicly available AlphaFold2 models, 187 adopt a conformation in which the three N-terminal domains are within Cα RMSD of 2.5 Å of the M. musculus model (SI Appendix, Fig. S16B). Additionally, a handful of publicly available predicted models adopt a conformation similar to what would be expected during folate demethylation, i.e., with the binding face of the Rossmann subdomain situated above the barrel opening in the folate domain. These include the 4-domain MetH from a Sphaerochaeta sp. (Uniprot A0A521IQ66, Fig. 6C) and five other models that are within 2.5 Å Cα RMSD (SI Appendix, Fig. S16C). The 1,512 remaining models largely predict conformations in which the B12 domain is somewhere along a trajectory between the resting-state and the homocysteine-methylation positions (SI Appendix, Fig. S16 A and B), possibly suggesting a path between these two states. Interestingly, these intermediate models do not align well with the cap-on B12 domain structure (14) and therefore represent partially or fully uncapped conformations. In all predicted models not in the reactivation conformation, the AdoMet domain is randomly placed, consistent with the notion that it is flexibly linked.

To develop a model for conformational change in MetH without the ambiguity created by the flexible AdoMet domain, we performed limited proteolysis of the full-length Cob(II) E. coli MetH following established protocols (17). A 98-kDa fragment containing only the three N-terminal domains of E. coli MetH (residues 2–896) was prepared to high purity and verified to be in the His-on Cob(II) state (SI Appendix, Fig. S17). SAXS was first performed on this fragment at 23 µM concentration in the absence of substrates. Remarkably, the Kratky plot displays a sharp peak at q ~ 0.055 Å−1 that decays quickly at high q (Fig. 6E and SI Appendix, Fig. S18, blue), indicating that the flexibility seen in the full-length enzyme is lost and that the three N-terminal domains must adopt a compact conformation in solution. In fact, the resting-state model of the three N-terminal domains from cryo-EM provides an excellent fit to the substrate-free SAXS data (Fig. 6E, blue/dashed). Incubation of the 98-kDa fragment at 23 μM with 0.6 mM (6S)-CH3-H4PteGlu3 leads to a Kratky plot with a slightly broader peak (Fig. 6E and SI Appendix, Fig. S18, green), clearly indicating a substrate-induced conformational transition within the three N-terminal domains of MetH, from the resting state to one that is more extended in shape. Unexpectedly, we find that the elusive folate-demethylation conformation predicted by AlphaFold2 provides a good fit to the data (Fig. 6E, green/dashed). We note that the AlphaFold2-predicted homocysteine-methylation conformation provides an equally good fit to the substrate-free data as the resting state (SI Appendix, Fig. S19). This is not too surprising as these conformations are highly similar at low resolution. However, based on our X-ray experiments of the full-length enzyme, which showed that CH3-Cob(III) is stable to photoreduction in the absence of substrates, we can gain confidence that the B12 domain is primarily cap-on in the free enzyme, which is the case for the resting-state conformation but not the homocysteine-methylation conformation.

Discussion

Seminal work by Jarrett et al. predicted the existence of two major MetH conformations that would enable the enzyme to distinguish its two methyl donors, CH3-H4folate and AdoMet (17). Crystal structures of C-terminal fragments of E. coli MetH (18, 19, 21) have shown that one of these major conformations must be that of the reactivation state, in which a cap-off B12 domain interacts with the AdoMet domain. In our study, we reported the existence of a resting-state conformation, in which the three N-terminal domains adopt a compact configuration that secures the B12 domain in a cap-on state, while the C-terminal AdoMet domain is highly mobile. Because this conformation appears to be shared by oxidation states in both the turnover and reactivation cycles, we propose that the resting state represents the second major conformation of MetH that was initially proposed 25 years ago (17). Based on the fact that the cobalamin cofactor must interact with three distantly located active sites, it has been known that MetH must be a flexible enzyme (13, 16, 17, 28, 31). Our work reveals that in the resting state, the majority of the enzyme’s flexibility is localized to the AdoMet domain. This model explains the tryptic proteolysis pathway that was shared by all oxidation states in the absence of flavoxin (17), and why MetH can function as a three-domain enzyme (25, 41).

Interestingly, we found that CH3-H4folate [specifically, (6S)-CH3-H4PteGlu3] is the only substrate that can induce a measurable conformational change from the resting state in both the Cob(II) and CH3-Cob(III) enzymes. Although in the case of the CH3-Cob(III) enzyme, X-ray exposure unavoidably led to reduction of the cofactor, this does not necessarily mean that the conformational change occurred in the Cob(II) state. Rather, it suggests that CH3-H4folate must have at least initiated a conformational change in the CH3-Cob(III) state to make homolysis of the Co–C bond irreversible. As was proposed in previous photolysis studies (24), such a conformational change is likely to involve the uncapping of the B12 domain, which makes the methyl radical more susceptible to escaping the enzyme. By studying the 98-kDa fragment of E. coli MetH, we confirmed that the CH3-H4folate-induced conformation is indeed consistent with a cap-off B12 domain interacting with the folate domain. We note that although experiments in this study were performed with the triglutamate derivative of CH3-H4folate, both mono- and polyglutamate forms are substrates for MetH (17), which bind similarly to the folate domain (26) and therefore would presumably promote the same conformational change. Furthermore, our cryo-EM model shows that in the resting state, the only active site that directly interacts with the B12 domain is that of the folate domain. Specifically, the cap subdomain and CH3-H4folate bind the same structural element in a mutually exclusive manner. CH3-H4folate is therefore the only substrate that can be rationalized to cause a conformational change from the observed resting state. Likewise, the existence of the resting-state conformation explains why MetH is able to sense CH3-H4folate. This provides a structural explanation for seminal findings from Banerjee et al. that demonstrated that MetH prefers to carry out its two primary turnover reactions in a sequential order, with CH3-H4folate binding first and H4folate dissociating last (16). Furthermore, sensitivity to CH3-H4folate provides MetH with an essential function in one-carbon metabolism. Although MetH serves as the link between the methionine and folate cycles, the enzyme is likely to be saturated with homocysteine in the cell (16), and production of methionine is not an essential function as it can be obtained from diet (43). In contrast, MetH is essential for assimilating CH3-H4folate into other folate species (11), and thus, it would make sense for this substrate to have a role in conformationally gating enzyme turnover.

Given that oxidation states in both the turnover and reactivation cycles appear to share a common resting-state conformation, a key question is how the enzyme is able to switch between the two cycles. Previous spectroscopic studies (27) indicated that flavodoxin must be able to bind Cob(II) MetH as it causes a change in the coordination geometry of the cobalamin cofactor from 5-coordinate (His-on) to 4-coordinate (His-off), while it is not able to bind the CH3-Cob(III) enzyme or reorganize its cofactor environment. NMR, electron transfer, and cross-linking studies (17, 23, 27, 44) have further shown that the C-terminal AdoMet domain is required for the two proteins to interact and that a large conformational change must occur in the Cob(II) state to enable rapid reduction by flavodoxin. Later, crystallographic studies established that a reactivation-state conformation of MetH exists (18, 19, 21) and that this conformation is stabilized by the change in the coordination geometry of Cob(II) cofactor, which frees His759 to interact instead with residues in the AdoMet domain (21). In this study, we have provided structural evidence that flavodoxin binding indeed favors the Cob(II) state over CH3-Cob(III). Under the condition of our study, which was near the pKa of free histidine, we found that both Cob(II) and CH3-Cob(III) MetH remain in a conformation that is largely consistent with the resting state at pH 7.6. However, a subtle change was observed in the Cob(II) scattering in lowering the pH from 7.6 to 6 that was accompanied by a shift in the UV-Vis absorption that was indicative of an increase in the His-off population. Based on these results, we hypothesize that although free MetH is predominantly in the resting-state conformation in both the Cob(II) and CH3-Cob(III) states, it more readily interconverts with the reactivation-state conformation in the Cob(II) state because the lower His759 ligand is able to interact with either the cofactor or the AdoMet domain. We further propose that flavodoxin is excluded in the resting-state conformation and favors interactions with the two C-terminal domains in the reactivation-state conformation. In this way, flavodoxin binding would be able to push the Cob(II) MetH population toward the His-off state.

Based on the findings from this study, we propose the following model for the mechanism by which MetH is able to switch between different functional modes. In this model, the resting-state conformation serves as the favored state in the absence of perturbations. During turnover, the enzyme will need to sample at least two additional conformations. In the resting state, the B12 Rossmann subdomain is already in contact with the back of the Hcy domain. It is plausible that the resting state of the enzyme is able to interconvert with a conformational state competent for homocysteine methylation without a major domain rearrangement. A possible trajectory for such a transition is populated by the collection of AlphaFold2 models in SI Appendix, Fig. S16 A and B. In contrast, our results indicate that the resting state cannot easily transition to the folate-demethylation state without CH3-H4folate binding. However, when CH3-H4folate binds to the folate domain, it engages the folate-sensing loop in a way that undocks the bound cap subdomain and prevents the resting state from reforming. Such a mechanism may serve to rebalance the conformational distribution of the enzyme such that both turnover states are sampled. Interestingly, the linker between the B12 domain and the folate domain is long enough that the B12 domain can travel to its predicted destinations in the folate-demethylation and homocysteine-methylation states while remaining cap-on (SI Appendix, Fig. S20, Left). Thus, we propose that during turnover, it is the capped B12 domain that travels and that positioning of the cap subdomain at the active-site opening enables the movement of the Rossmann domain to bring the cofactor in close contact with the substrate (SI Appendix, Fig. S20). Finally, as described above, we propose that the resting state can interconvert with the reactivation state and that this forward conversion is more favored when His759 can participate in interdomain interactions. Thus, although Cob(II) MetH favors the resting state conformation, it can be recognized by flavodoxin when it occasionally samples the His-off, reactivation conformation. In this way, flavodoxin can siphon the inactive enzyme from the turnover cycle ensemble to initiate reactivation, as shown in Fig. 1B. Once CH3-Cob(III) is regenerated by reductive methylation, the enzyme would again favor the resting-state conformation. By having a common resting-state conformation, the enzyme would be able to “reset” and return to the turnover cycle.

Over the course of this study, several technical advances emerged that enabled key aspects of our investigation. These included the rapid evolution of single-particle cryo-EM (45) as well as the development of anoxic SAXS. On the computational front, the advent of AlphaFold2 (35) had a surprising impact. We showed that AlphaFold2 succeeded in predicting the resting state, a conformation that does not yet exist in the training dataset. Although structure prediction cannot replace experimental structural biology, this was an extraordinary feat. We further demonstrated two unique uses of the AlphaFold2 database that greatly expand upon conventional analyses of multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) in structural biology. First, by analyzing the collection of predicted models in the public AlphaFold2 database, we were able to visualize conformations that differ significantly from those represented in the PDB (SI Appendix, Fig. S16). In the case of MetH, sequences with high similarity to the E. coli enzyme are more likely to be predicted in the reactivation state, which is highly represented in the PDB (SI Appendix, Fig. S21A). Thus, the availability of structure predictions for a diverse sequence dataset is likely to reveal conformations that have never been considered before (SI Appendix, Fig. S21 B–E), especially for flexible, mutidomain enzymes. Second, analysis of the AlphaFold2 database also provided insight into how sequence variability can still lead to conserved functions (SI Appendix, Fig. S14). Based on conventional MSA analysis, we found that residues involved in the interface between the cap subdomain and the folate domain are not fully conserved. Analysis of alternate sequence motifs in the AlphaFold2 database, however, suggested that the nonconserved residues have coevolved in a way that conserves the overall set of interactions. Such an insight cannot be easily obtained from sequence analyses alone. It is worth repeating that structural biology should not be replaced by structure prediction, which does not yet have angstrom to subangstrom level accuracy. However, we anticipate that structure prediction will continue to enhance experimental efforts, possibly in ways that we cannot yet imagine.

Materials and Methods

Untagged, full-length E. coli MetH (residues 2–1,227) and its fragment containing the three N-terminal domains (residues 2–896) were prepared following previously described methods (17, 32, 46). His6-tagged E. coli flavodoxin was purified by a cobalt-affinity column followed by size exclusion. Tagless T. filiformis MetH was prepared using a cleavable His6-SUMO tag and reconstituted as described in detail in SI Appendix. Detailed descriptions of protein expression and purification, preparation of pure oxidation states, cofactor reconstitution, limited proteolysis, SAXS, cryo-EM, bioinformatics, and AlphaFold2 analyses are available in SI Appendix. The oxidation state and coordination geometry of the cobalamin cofactor was verified by UV-Vis spectroscopy for every sample in every experiment. Unless otherwise specified (e.g., for experiments performed at pH 6), CH3-Cob(III) and Cob(II) states were verified to be almost entirely His-on for both the E. coli and T. filiformis enzymes.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Mode capturing the movement of the linker connecting the C-terminus of the B12 domain and the AdoMet domain obtained by cryoSPARC48 3D variability analysis.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Prof. Rebecca Taurog (Williams College) for providing us with plasmids, reagents, and helpful tips; to Gabrielle Illava for setting up the anoxic SAXS system; and to Dr. Amanda Byer for assistance with SAXS data collection and critical reading of this manuscript. We are also grateful to Drs. Richard Gillilan, Qingqiu Huang, and Jesse Hopkins for assistance with SAXS setup at CHESS and Drs. Katie Spoth and Mariena Ramos (CCMR) as well as Drs. Edward Eng and Eugene Chua (NCCAT) for assistance with cryo-EM data collection. Finally, we thank Prof. Yan Kung (Bryn Mawr) for sharing a protocol for titanium(III) citrate, Prof. Dominica Borek (UT Southwestern) for suggesting the use of apoferritin, and Prof. Markos Koutmos (U Mich) for suggesting the use of thermophilic enzymes. SAXS was conducted at the Center for High-Energy X-ray Sciences (CHEXS), which is supported by the at NSF (BIO, ENG and MPS Directorates) under award DMR-1829070, and the Macromolecular Diffraction at CHESS (MacCHESS) facility, which is supported by award P30 GM124166 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, NIH, and by New York State’s Empire State Development Corporation (NYSTAR). Additional SAXS was performed with a Xenocs BioXolver funded by NIH grant S10OD028617. Cryo-EM data collection was performed at the Cornell Center for Materials Research (CCMR), which is supported by the NSF under award DMR-1719875, as well as at the National Center for Cryo-EM Access and Training (NCCAT) in New York City, which is supported by the NIH Common Fund Transformative High Resolution Cryo-Electron Microscopy program grant number U24 GM129539. This work was supported by NIH grants GM100008 and GM124847 and startup funds from Princeton University and Cornell University to N.A.

Author contributions

M.B.W. designed research and performed the majority of experiments and data analysis; M.B.W., H.W., A.B., and N.A. performed research; H.W. prepared the 98 kDa fragment, performed SAXS on the fragment, measured UV-Vis spectra, performed AlphaFold2 analysis and contributed to editing and writing of the paper; A.B. performed bioinformatics and contributed to editing and writing of the paper; N.A. conceived of the project, oversaw and supervised the research, analyzed data, and acquired funding; and M.B.W. and N.A. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. V.B. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

The cryo-EM map has been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank under accession code EMD-29699 (47), and the model has been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession code PDB 8G3H (48). The python scripts for conformational alignment of AlphaFold2 database structures are available on the Ando Lab GitHub page, https://github.com/ando-lab/2023-watkins-scripts.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Banerjee R. V., Matthews R. G., Cobalamin-dependent methionine synthase. FASEB J. 4, 1450–1459 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watkins D., et al. , Hyperhomocysteinemia due to methionine synthase deficiency, cblG: Structure of the MTR gene, genotype diversity, and recognition of a common mutation, P1173L. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 71, 143–153 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gulati S., Defects in human methionine synthase in cblG patients. Hum. Mol. Genet. 5, 1859–1865 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doolin M.-T., et al. , Maternal genetic effects, exerted by genes involved in homocysteine remethylation, influence the risk of spina bifida. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 71, 1222–1226 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guéant J.-L., Guéant-Rodriguez R.-M., Kosgei V. J., Coelho D., Causes and consequences of impaired methionine synthase activity in acquired and inherited disorders of vitamin B12 metabolism. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 57, 133–155 (2022), 10.1080/10409238.2021.1979459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim J., Kim H., Roh H., Kwon Y., Causes of hyperhomocysteinemia and its pathological significance. Arch. Pharm. Res. 41, 372–383 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolthers K. R., Scrutton N. S., Protein interactions in the human methionine synthase−Methionine synthase reductase complex and implications for the mechanism of enzyme reactivation. Biochemistry 46, 6696–6709 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen L. H., et al. , Human methionine synthase. cDNA cloning, gene localization, and expression. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 3628–3634 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Z., Crippen K., Gulati S., Banerjee R., Purification and kinetic mechanism of a mammalian methionine synthase from pig liver. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 27193–27197 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim S.-E., Enzymes involved in folate metabolism and its implication for cancer treatment. Nutr. Res. Pract. 14, 95 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghergurovich J. M., et al. , Methionine synthase supports tumour tetrahydrofolate pools. Nat. Metab. 3, 1512–1520 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao J., et al. , S-Adenosyl methionine and transmethylation pathways in neuropsychiatric diseases throughout life. Neurotherapeutics 15, 156–175 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans J. C., et al. , Structures of the N-terminal modules imply large domain motions during catalysis by methionine synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 3729–3736 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drennan C. L., Huang S., Drummond J. T., Matthews R. G., Ludwig M. L., How a protein binds B12: A 3.0 Å X-ray structure of B12-binding domains of methionine synthase. Science 266, 1669–1674 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dixon M. M., Huang S., Matthews R. G., Ludwig M., The structure of the C-terminal domain of methionine synthase: Presenting S-adenosylmethionine for reductive methylation of B12. Structure 4, 1263–1275 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banerjee R. V., Frasca V., Ballou D. P., Matthews R. G., Participation of Cob(I)alamin in the reaction catalyzed by methionine synthase from Escherichia coli: A steady-state and rapid reaction kinetic analysis. Biochemistry 29, 11101–11109 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jarrett J. T., Huang S., Matthews R. G., Methionine synthase exists in two distinct conformations that differ in reactivity toward methyltetrahydrofolate, adenosylmethionine, and flavodoxin†. Biochemistry 37, 5372–5382 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barian V., et al. , Domain alternation switches B12-dependent methionine synthase to the activation conformation. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9, 53–56 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koutmos M., Datta S., Pattridge K. A., Smith J. L., Matthews R. G., Insights into the reactivation of cobalamin-dependent methionine synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 18527–18532 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koutmos M., et al. , Metal active site elasticity linked to activation of homocysteine in methionine synthases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 3286–3291 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Datta S., Koutmos M., Pattridge K. A., Ludwig M. L., Matthews R. G., A disulfide-stabilized conformer of methionine synthase reveals an unexpected role for the histidine ligand of the cobalamin cofactor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 4115–4120 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jarrett J. T., Hoover D. M., Ludwig M. L., Matthews R. G., The mechanism of adenosylmethionine-dependent activation of methionine synthase: A rapid kinetic analysis of intermediates in reductive methylation of Cob(II)alamin enzyme. Biochemistry 37, 12649–12658 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall D. A., Jordan-Starck T. C., Loo R. O., Ludwig M. L., Matthews R. G., Interaction of flavodoxin with cobalamin-dependent methionine synthase. Biochemistry 39, 10711–10719 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jarrett J. T., et al. , A protein radical cage slows photolysis of methylcobalamin in methionine synthase from Escherichia coli. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 4, 1237–1246 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drummond J. T., Huang S., Blumenthal R. M., Matthews R. G., Assignment of enzymic function to specific protein regions of cobalamin-dependent methionine synthase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 32, 9290–9295 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamada K., Koutmos M., The folate-binding module of Thermus thermophilus cobalamin-dependent methionine synthase displays a distinct variation of the classical TIM barrel: A TIM barrel with a ‘twist’. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol. 74, 41–51 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoover D. M., et al. , Interaction of Escherichia coli cobalamin-dependent methionine synthase and its physiological partner flavodoxin: Binding of flavodoxin leads to axial ligand dissociation from the cobalamin cofactor. Biochemistry 36, 127–138 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bandarian V., Matthews R. G., “Measurement of energetics of conformational change in cobalamin-dependent methionine synthase” in Methods in Enzymology (Elsevier, 2004), vol. 380, pp. 152–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meisburger S. P., Thomas W. C., Watkins M. B., Ando N., X-ray scattering studies of protein structural dynamics. Chem. Rev. 117, 7615–7672 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Byer A. S., Pei X., Patterson M. G., Ando N., Small-angle X-ray scattering studies of enzymes. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 72, 102232 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bandarian V., Ludwig M. L., Matthews R. G., Factors modulating conformational equilibria in large modular proteins: A case study with cobalamin-dependent methionine synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 8156–8163 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jarrett J. T., Goulding C. W., Fluhr K., Huang S., Matthews R. G., “Purification and assay of cobalamin-dependent methionine synthase from Escherichia coli” in Methods in Enzymology (Elsevier, 1997), vol. 281, pp. 196–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor R. T., Weissbach H., Escherichia coli B N5-methyltetrahydrofolate-homocysteine vitamin-B12 transmethylase: Formation and photolability of a methylcobalamin enzyme. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 123, 109–126 (1968). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Illava G., Gillilan R. E., Ando N., Development of in-line anoxic small-angle X-ray scattering and structural characterization of an oxygen-sensing transcriptional regulator. bioRXiv [Preprint] (2023). 10.1101/2023.05.18.541370 (Accessed 6 April 2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Jumper J., et al. , Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Glaeser R. M., Preparing better samples for cryo-electron microscopy: Biochemical challenges do not end with isolation and purification. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 90, 451–474 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoshimura H., Scheybani T., Baumeister W., Nagayama K., Two-dimensional protein array growth in thin layers of protein solution on aqueous subphases. Langmuir 10, 3290–3295 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bernadó P., Mylonas E., Petoukhov M. V., Blackledge M., Svergun D. I., Structural characterization of flexible proteins using small-angle X-ray scattering. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 5656–5664 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tria G., Mertens H. D. T., Kachala M., Svergun D. I., Advanced ensemble modelling of flexible macromolecules using X-ray solution scattering. IUCrJ 2, 207–217 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Punjani A., Fleet D. J., 3D variability analysis: Resolving continuous flexibility and discrete heterogeneity from single particle cryo-EM. J. Struct. Biol. 213, 107702 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang S., et al. , Reactivation of methionine synthase from Thermotoga maritima (TM0268) requires the downstream gene product TM0269. Protein Sci. 16, 1588–1595 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baek M., et al. , Accurate prediction of protein structures and interactions using a three-track neural network. Science 373, 871–876 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krupenko N. I., “Chapter 39. Folate and vitamins B6 and B12” in Principles of Nutrigenetics and Nutrigenomics: Fundamentals of Individualized Nutrition 566 (Elsevier, Academic Press, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hall D. A., et al. , Mapping the interactions between flavodoxin and its physiological partners flavodoxin reductase and cobalamin-dependent methionine synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 9521–9526 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rivera-Calzada A., Carroni M., Editorial: Technical advances in cryo-electron microscopy. Front. Mol. Biosci. 6, 72 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bandarian V., Matthews R. G., Quantitation of rate enhancements attained by the binding of cobalamin to methionine synthase. Biochemistry 40, 5056–5064 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Watkins M.B., Ando N., Structure of cobalamin-dependent methionine synthase (MetH) in a resting state. Electron Microscopy Data Bank and Protein Data Bank. https://www.ebi.ac.uk/emdb/EMD-29699. Deposited 6 February 2023.

- 48.Watkins M.B., Ando N., Structure of cobalamin-dependent methionine synthase (MetH) in a resting state. Electron Microscopy Data Bank and Protein Data Bank. https://www.rcsb.org/structure/8G3H. Deposited 6 February 2023.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Mode capturing the movement of the linker connecting the C-terminus of the B12 domain and the AdoMet domain obtained by cryoSPARC48 3D variability analysis.

Data Availability Statement

The cryo-EM map has been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank under accession code EMD-29699 (47), and the model has been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession code PDB 8G3H (48). The python scripts for conformational alignment of AlphaFold2 database structures are available on the Ando Lab GitHub page, https://github.com/ando-lab/2023-watkins-scripts.