Abstract

During school closures prompted by the Covid-19 pandemic, educational technology (EdTech) was often used to continue educational provision. In this article, we consider EdTech effectiveness using a holistic framework, and synthesise findings from 10 primary research studies of EdTech interventions conducted in low- and middle-income countries during the pandemic. The framework includes five main lenses: learning outcomes, enhancing equity, implementation context, cost and affordability, and alignment and scale. While in-person schooling has largely resumed, there continues to be further integration of EdTech into education systems globally. This analysis provides evidence-based insights and highlights knowledge gaps to shape holistic analysis of both EdTech mainstreaming and future research into the effective use of EdTech to strengthen learning.

Keywords: International education, Development, Educational technology, Covid-19 pandemic, Research synthesis

1. Introduction

School closures were one of the most widespread policy responses as the Covid-19 pandemic unfolded across the globe (Hale et al., 2021). During this period, technology for education (EdTech) took on new prominence as a lifeline for learners, teachers, parents, and caregivers (Bozkurt et al., 2020, Dreesen et al., 2020, Haßler et al., 2020). With in-person schooling having now largely resumed, there is an opportunity to take stock of lessons from this ‘great EdTech experiment’ and contribute to a growing body of literature exploring how EdTech can be more effective in supporting learning going forward (Barron Rodriguez et al., 2021, Munoz-Najar et al., 2021, Williamson et al., 2021).

1.1. Covid-19 and questions on EdTech effectiveness

The question of EdTech effectiveness is critical, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where evidence shows that the pandemic has only worsened the pre-existing learning crisis. In countries with available data, four out of five have reported learning losses (UNESCO et al., 2022). According to the Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel (GEEAP, 2022), on average, school closures in LMICs were longer than in high-income countries, students had less technology access for continuing education, and there was less adaptation in provision. This has meant that learning loss during the pandemic was often larger in LMICs compared to Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries (ibid.), with the World Bank (2021) estimating that learning poverty has risen to 70% in the former.

Yet, during the pandemic, the quality and reach of different remote learning policies and approaches varied greatly (World Bank et al., 2021), with “evidence … mounting of the low effectiveness of remote learning efforts” (GEEAP, 2022, p.6). EdTech is now increasingly included in government education sector plans (Chuang et al., 2022, UNICEF, 2022), and while 2020 alone saw over USD 16 billion in venture capital in EdTech, there are predictions of a global market worth USD 404 billion by 2025 (HolonIQ, 2021, HolonIQ, 2022). Ensuring these investments are spent wisely is important, with critical reflection needed on the potential of EdTech interventions and under what conditions they appear to be effective.

1.2. EdTech Hub and Covid-19 primary research

In 2020, as countries grappled with EdTech’s role in supporting remote learning, many actors pivoted to respond to their needs and challenges. As part of this, the EdTech Hub - a global research partnership focused on evidence and decision-making on technology in education - issued a call for primary research on EdTech use during the Covid-19 pandemic. Selected from a pool of more than 175 proposals, a group of 10 studies were commissioned. These were conducted over the course of 2021 in Bangladesh, Ghana, Kenya, Pakistan, and Sierra Leone, countries that were prioritised because of a perceived high level of interest in EdTech and the potential to share applicable lessons across contexts (EdTech Hub, 2022).

The studies entailed research on remote learning using low-tech interventions aimed at providing education for students of different ages, training for teachers, and engaging parents and caregivers in their children’s learning, with one study unique in its focus on data architecture. Three main types of devices were used across the studies: radio, television, and mobiles/smartphones. The projects have now all concluded and published findings in their own right, offering an opportunity to reflect on the portfolio as a whole and identify broader messages for the field.

1.3. 1.3 Research questions

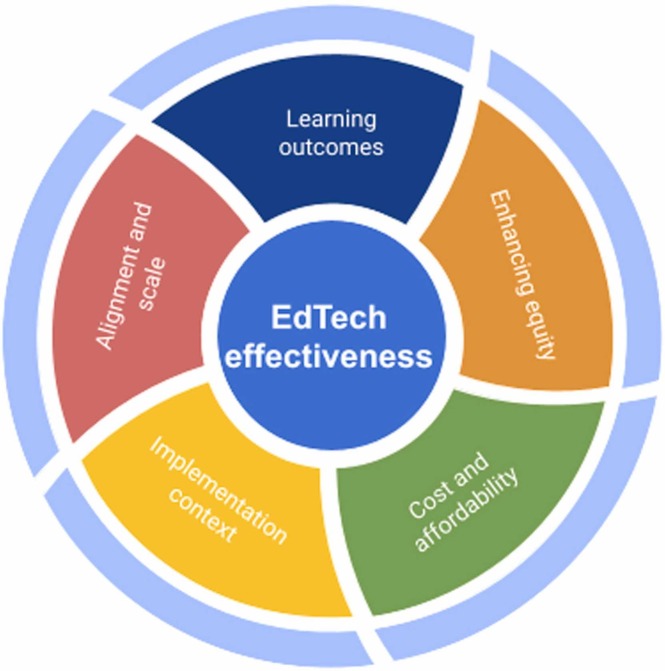

In this paper, we take a synoptic view across our portfolio of 10 studies and analyse findings through a lens of EdTech effectiveness. Our conceptualisation of effectiveness is based on a framework by Hollow and Jefferies (2022), which poses five critical questions for considering EdTech effectiveness ( Fig. 1). The framework acknowledges that there is a need for robust research evidence to be available to policymakers but also that evidence needs to be contextualised and nuanced. Applying this framework leads to an analysis of the impact of EdTech interventions in terms of learning outcomes; enhancing equity; cost and affordability; implementation issues and context; and alignment and scale. We examine what existing literature says in relation to EdTech effectiveness in each of these realms and situate related findings from our studies within this framework. This allows us to present a holistic understanding of the effectiveness of EdTech in relation to the experiences of the research portfolio, identifying evidence-based insights and knowledge gaps for future research.

Fig. 1.

Framework for EdTech effectiveness used in the analysis of 10 primary research studies conducted during the Covid-19 pandemic, after Hollow and Jefferies (2022).

As such, this study is guided by the following main research questions:

-

1.

What are the characteristics of the research designs used in the portfolio of EdTech and Covid-19 projects?

-

2.

What are the emergent findings from across the portfolio in relation to EdTech effectiveness and implications for education as the pandemic subsides?

2. Methods

The research questions are addressed using content and thematic analysis (Cohen, et al., 2007). The sample is defined as the final research reports produced by each of the 10 projects in the portfolio. Each research report is a comprehensive account of the research project, its rationale, design, and findings. Reports range from 59 to 100 pages in length, with an average length of 77 pages. The reports were published between mid-2021 and early 2022. As the sample consists of research reports which are publicly available documents published through the EdTech Hub website, there are no ethical concerns associated with this study. An overview of the 10 projects used in our sample is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of the 10 projects which formed the EdTech Hub Covid-19 research projects portfolio.

| Study | Location | Research partner | Project title | Research design | Data collected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adil et al. (2021) | Pakistan | Sustainable Development Policy Institute | Investigating the Impact on Learning Outcomes Through the Use of EdTech During Covid-19: Evidence from an RCT in the Punjab province of Pakistan | RCT | Interviews; focus groups; survey; learning assessments |

| Afoakwah et al. (2021) | Ghana | Rising Academy Network | Dialling up Learning: Testing the Impact of Delivering Educational Content via Interactive Voice Response to Students and Teachers in Ghana | RCT | Survey; learning assessments |

| Amenya et al. (2021) | Kenya | Education Development Trust | The Power of Girls' Reading Camps: Exploring the impact of radio lessons, peer learning and targeted paper-based resources on girls' remote learning in Kenya | Mixed methods | Interviews; focus groups; learning asssessments |

| Ananga et al. (2021) | Ghana | Transforming Teacher Education and Learning (T-TEL) | T-TEL COVID-19 Impact Assessment Study | Mixed methods | Interviews; survey; virtual lesson observations |

| Aurino et al. (2022) | Ghana | Innovations for Poverty Action | Nudges to Improve Learning and Gender Parity: Preliminary findings on supporting parent–child educational engagement during Covid-19 using mobile phones | RCT | Survey; learning assessment |

| Fab Inc. (2021) | Sierra Leone | Fab Inc. | Learning from experience: A post-Covid-19 data architecture for a resilient education data ecosystem in Sierra Leone | Data dashboard development | Secondary data analysis |

| Hodor et al. (2021) | Ghana | Participatory Development Associates | Voices and Evidence from End-Users of the GLTV and GLRRP Remote Learning Programme in Ghana: Insights for inclusive policy and programming | Qualitative and participatory approach | Interviews; focus groups; secondary data analysis |

| Islam et al. (2021) | Bangladesh | Beyond Peace | Integration of Technology in Education for Marginalised Children in an Urban Slum of Dhaka City During the Covid-19 Pandemic | Quantitative survey | Survey |

| Islam et al. (2022) | Bangladesh | Monash University | Delivering Remote Learning Using a Low-Tech Solution: Evidence from an RCT during the Covid-19 Pandemic | RCT | Survey; learning assessment; secondary data analysis |

| Tembey et al. (2021) | Kenya | Busara | Understanding Barriers to Girls’ Access and Use of EdTech in Kenya During Covid-19 | Mixed methods | Interviews; survey |

Once collated, the reports were closely read and categorised according to a range of aspects of the project and research design, in order to address the first research question. Categories included the educational context, types of EdTech used, types of research questions addressed, research methods used, and outcomes measured.

The second research question was addressed by coding findings in relation to different ways in which ‘effectiveness’ can be conceptualised. We used deductive thematic analysis (Xu & Zammit, 2020), adapting a framework drawn from Hollow and Jefferies (2022, p.4), which sets out five main questions for EdTech decision-makers:

-

1.

Will this use of technology lead to a sustained impact on learning outcomes?

-

2.

Will this use of technology work for the most marginalised children and enhance equity?

-

3.

Will this use of technology be feasible to scale in a cost-effective manner that is affordable for the context?

-

4.

Will this use of technology be effective in the specific implementation context?

-

5.

Will this use of technology align with government priorities and lead to the strengthening of national education systems?

While the collection of studies funded under the EdTech Hub Covid-19 grants scheme provides a robust and diverse snapshot of studies undertaken in response to the pandemic, there are, of course, limitations. Focusing the sample on our portfolio means that other studies undertaken during the pandemic are not included, so the analysis is not exhaustive nor representative. Moreover, the sample reflects the priorities of EdTech Hub in terms of subject matter and geography; however, this collection can be viewed as a reliable source as it includes studies across a consistent and focused period, which have all been through EdTech Hub’s quality assurance process. In due course a wider range of peer-reviewed outputs will become available from other studies undertaken during the pandemic, however at the time of undertaking this analysis, few studies had been publicly reported as comprehensively as the portfolio of reports. While the synthesis is subjective to an extent, it builds on the work across the projects and consolidates what we have learned, what has been echoed between studies, and potential points of departure for further research.

3. Characteristics of the studies

To illustrate the range of topics and approaches covered by the Covid-19 response, the studies were categorised according to several aspects of the inquiry and research design. An overview of the nature of the inquiry of the studies, including the types of EdTech used, the purpose of the studies, and the user groups involved, is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Types of EdTech used, for what purpose and with which user groups, by studies within the Covid-19 research projects portfolio.

| Study | EdTech used | Purpose and learning outcomes | Location | Participants and sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adil et al. (2021) | Online learning using Teaching at the Right Level (TaRL), computers | Promotion of maths, Urdu, and English; professional development in tech- assisted instruction | Pakistan: Bahawalnagar district in the province of Punjab | 258 students in Grade 8 and 15 teachers from 12 schools in a remote area |

| Afoakwah et al. (2021) | Interactive Voice Response (IVR) audio lessons | Promotion of foundational numeracy & literacy skills; professional development on instruction | Ghana: network of low-cost private primary schools | 1,359 students in Grades 4, 5, 6 and 333 teachers from 30 schools |

| Amenya et al. (2021) | Radio and reading camps | Promotion of reading and maths | Kenya: ASAL (Arid and Semi-Arid Lands) areas (Kilifi, Turkana, Samburu, and Tana River) | 1,230 girl students in Grades 6 and 7 |

| Ananga et al. (2021) | Online learning | Assessment of teaching and learning improvement | Ghana: colleges of education | 356 pre-service student teachers from marginalised backgrounds from 30 public colleges of education |

| Aurino et al. (2022) | Text message “nudges” | Behaviour change in children’s learning to promote gender parity | Ghana: rural regions in Northern Ghana | Parents and carers from 2,628 households with school-aged children with low levels of literacy/education, girl students |

| Fab Inc. (2021) | Data systems | Development of data architecture and dashboard tool | Sierra Leone: national data | Secondary analysis of Annual School Census data and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys |

| Hodor et al. (2021) | Television and radio lessons | Assessment of effective continuous learning in English, mathematics, science, and social studies | Ghana: urban and rural districts across three regions, the northern zone (Northern Region), middle zone (Ashanti Region) and southern zone (Greater Accra Region) | 285 participants across a range of stakeholders, including in-school and out-of-school learners; learners with disabilities, parents, teachers, headteachers and radio stations |

| Islam et al. (2021) | Television, radio, smartphone, computer | Assessment of device access and usage | Bangladesh: Korail urban slum in Dhaka | 476 households with students in Grades 6 to 10, low-income backgrounds |

| Islam et al. (2022) | IVR audio lessons | Promotion of English and Bangla language literacy, numeracy, non-cognitive skills | Bangladesh: Khulna and Satkhira districts | 1,763 children from 90 villages: students aged 5 to 10; low-income backgrounds; parents and caregivers |

| Tembey et al. (2021) | Television, radio, video (e.g. YouTube) | Assessment of girls’ barriers, participatory product development | Kenya: Nairobi and rural counties | 494 caregivers of girl students aged 7–14, low-income backgrounds |

The study topics covered a range of different participants and perspectives within educational systems. Studies most frequently focused on students as participants (seven studies), spanning a range of ages and grades across primary and secondary education. Teachers were included in three studies, while parents and caregivers were a focus in two instances. One study was distinct in that it focused on how data is used to support decision-making at the level of the education ministry, with teachers as potential beneficiaries of the data use.

In relation to the role of EdTech, the research studies focused on low-tech and low-connectivity technology in their interventions and used a range of technology-based approaches to reach their target groups. Three main types of devices were used: radio (six studies, often IVR applications), TV (three studies), and mobile devices and smartphones (two studies). Two studies focused on online learning, which could be accessed via computers or mobile devices with good connectivity. The form of content delivered through the devices included audio lessons, audio-visual lessons (e.g., YouTube), text messages, social media/digital applications (e.g., Zoom, WhatsApp), and digital platforms (for online learning). Multiple modalities were used in three cases– typically involving both television and radio – which may have reflected the broader practice of using a range of media to reach as wide a range of learners as possible (Dreesen et al., 2020).

Most studies addressed research questions focused on evaluating the impacts of the various EdTech interventions, particularly in terms of learning outcomes and participation in education. Furthermore, the studies also sought to identify factors that could foster supportive conditions but also barriers to uptake. Most studies looked at factors of vulnerability and marginalisation, such as income level, location, and disability, to varying extents. More than half examined ways that EdTech could advance gender equality by promoting girls and women (i.e., through teacher professional development) in remote education.

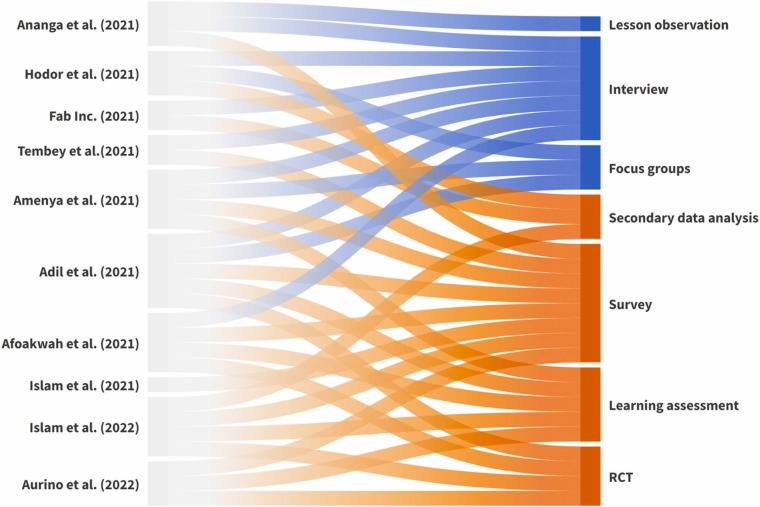

A variety of research methods were employed, with all studies collecting primary data ( Fig. 2) and undertaking literature reviews. Most studies were ‘mixed methods’ in the sense that a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods was used. Qualitative methods involved interviews, focus groups, and lesson observations. Quantitative methods included surveys, learning assessments, randomised control trials (RCT), and secondary data analysis.

Fig. 2.

Range of methods used to collect data across studies. Primarily qualitative methods are shown in blue, while quantitative methods are in orange.

Across the studies, five main types of measures were used to gauge the projects’ impact and outcomes. An aggregated categorisation of these measures includes changes to learning outcomes; engagement with content; levers to access and use; group-based variations; and perceptions and awareness. Additionally, while studies were asked to consider cost-effectiveness, the extent to which this was possible in practice was limited. More detail on specific measuresis provided in the discussion in Section 4.

4. Analysis related to effectiveness

The question of how effective the use of EdTech is – and how this varies according to different forms of EdTech, or in comparison to non-EdTech educational initiatives – is a core concern for the field (Evans and Popova, 2015, McEwan, 2015, Rodriguez-Segura, 2020). The focus of our analysis here is on the different ways in which the studies conceptualised and evaluated the ‘effectiveness’ of the interventions at hand. As outlined above, five main areas are used, which together can provide a more holistic picture of effectiveness. In this section, each will be introduced and discussed in turn, drawing on examples from the projects for further insight.

4.1. Impact on learning outcomes

That learning levels are low in many countries around the world, particularly LMICs, is well established (World Bank, 2022, World Bank, 2018, World Bank, 2019, UNESCO, 2017). In light of what has often been called a ‘learning crisis’, the measurement of learning outcomes has taken on a new importance, both at the macro level through large-scale learning assessments (Addey et al., 2017, Angrist et al., 2021, Appels et al., 2022;), as well as at the more micro level, focusing on schools and students (Andrade et al., 2021, Barrett, 2016). Evidence of learning gains has become a kind of ‘gold standard’ to which education systems and programmes are held in terms of showing their ‘effectiveness’. This is equally true in EdTech, where questions of effectiveness are often closely tied to whether or not learning gains have been achieved (Rodriguez-Segura, 2020, See et al., 2022). This became even more critical during the pandemic when remote learning became prominent. The issue of ‘learning losses’ as a result of school closures – conceptualised as a combination of lost educational opportunities and/or diminished attainment (Pier et al., 2021) – was an immediate concern. Measurement of learning outcomes has therefore been key in examining gains or losses in close to real-time (e.g. Angrist et al., 2020a).

The issue of how to measure the impact on learning outcomes was a primary concern for nearly all of our studies, with most of them measuring learning gains directly (Adil et al., 2021, Afoakwah et al., 2021, Amenya et al., 2021, Aurino et al., 2022, Islam et al., 2022), with others also collecting data in relation to perceived impacts on learning outcomes reported by participants (e.g., Hodor et al., 2021). Assessment tools used were mainly focused on foundational learning outcomes, often using instruments which have been developed and validated independently and composed of test items for both literacy and numeracy. It is notable that the availability of existing validated tools, which could be rapidly deployed, allowed the collection of data on learning gains despite the relatively short timescale and crisis context. Student learning assessment tools used by the studies included:

-

•

Adil et al. (2021): Language and mathematics tests administered for the ASER (Annual Status of Education Report) Survey, and grade-appropriate tests based on the Punjab textbook board syllabus for maths, English, and Urdu for older children.

-

•

Afoakwah et al. (2021): Grade 4 TIMSS (Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study) items (TIMSS, 2013);

-

•

Amenya et al. (2021): SeGRA (Senior Grade Reading Assessment) and SeGMA (Senior Grade Mathematics Assessment) covering literacy and mathematics for older pupils;

-

•

Aurino et al. (2022): Literacy and numeracy were both assessed, using items from the IDELA (International Development and Early Learning Assessment; Pisani et al., 2018), EGRA (Early Grade Reading Assessment; RTI International, 2016), EGMA (Early Grade Math Assessment; Platas et al., 2014) and the Young Lives surveys (Barnett et al., 2013);

-

•

Islam et al., 2022: Assessment taken from the national curriculum of Bangladesh covering English literacy, Bangla literacy, numeracy, and general knowledge (Islam et al., 2022, p.60); plus, Renzulli scales to measure noncognitive outcomes (with mothers as respondents) (Renzulli et al., 2002).

Assessment data collected across the studies showed mixed results in terms of learning outcomes, where perceptions of effectiveness also varied. Although not directly comparable, the findings do, in some instances, illustrate positive effects on learning outcomes and highlight the need for additional data to understand variation. For instance, in a Bangladesh study, IVR showed positive effects on learning outcomes – mainly English literacy and numeracy – for primary school children along with other areas, with evidence also demonstrating increases in students’ interest, attention span and time investment in education (Islam et al., 2022). However, positive effects were less pronounced in another IVR study in Ghana, only impacting one aspect of numeracy: place value knowledge (Afoakwah et al., 2021). Online TaRL (in Pakistan) had variable effects for Grade 8 students, causing language scores to go up but not affecting maths scores (Adil et al., 2021).

As noted above, the availability of validated tools to measure learning outcomes allowed the studies to generate data rapidly, which will continue to be an important focus for research projects seeking to understand learners’ progress in the wake of the closures and identify the gaps in returning to standard educational provision. Furthermore, beyond the domains of literacy and numeracy, the range of types of learning outcomes for which robust tools are available is limited (Anderson, 2019). An observation which emerged from the analysis was that when used, assessment was found to contribute to improved learning, but there was also concern about a lack of transparency about what would be assessed and how it would be used (Adil et al., 2021), which is a key practical consideration for future research designs.

While the measurement of learning outcomes is fundamental to evaluating educational efficacy, this alone does not shed light on the pedagogies that support these gains. Learners across our studies indicate a desire for increased opportunities for interactivity and tailoring interventions to the right level for the individual. For example, in a Ghana study, learners felt radio and television programmes should be taught at a slower pace, be more interactive and repeated (Hodor et al., 2021). In one study using IVR on phones, students reported that the quiz was the best part of the lesson and that they would like to see more interactive elements, such as choice in lesson content (Afoakwah et al., 2021). Similarly, students indicated a preference for using social media platforms for learning (such as Facebook and YouTube, also Zoom and Google Meet), mostly through smartphones, because of the heightened interaction compared to one-way modalities (Islam et al., 2021). In contrast, only a fifth of respondents reported watching the government’s televised educational programming (Islam et al., 2021).

4.2. Enhancing equity

Equity has been a long-standing concern in the field of EdTech. In ‘Rethinking the Digital Divide’, Warschauer (2003) argues that equitable access to digital technology needs to go beyond merely providing devices and internet connections; it needs to factor in language and literacy variances, human and social relationships, communities, and institutional structures. Citing further factors of representation, contribution, and non-neutral networks/technologies, Graham et al. (2015) conclude that striving for equality is not just a technological challenge but a socio-technological one. Writing in the context of the pandemic, Unwin et al. (2020) argue that for EdTech to be equitable, it needs to intentionally focus on reaching the poorest and most marginalised and not just be a by-product of scale. Research on justice-oriented digitised education further argues that for EdTech to support marginalised groups effectively, teachers and learners need to be equipped in terms of accessing, utilising, and benefitting equitably from EdTech provisions (Adam, 2022).

The equity lenses used in the research studies reviewed correlated with reflections which highlight that equity policies and research, including in EdTech, tend to focus more on girls and rural populations in comparison to other marginalised groups such as ethnic and religious minorities (Zubairi et al., 2021, Sarwar et al., 2021). In terms of equity, some studies explicitly focused on certain marginalised groups: girls and young women (Amenya et al., 2021, Aurino et al., 2022, Tembey et al., 2021), low-income groups (Afoakwah et al., 2021, Ananga et al., 2021, Islam et al., 2021, Islam et al., 2022), learners from urban slums (Islam et al., 2021), and remote or rural regions (Adil et al., 2021, Amenya et al., 2021, Aurino et al., 2022, Hodor et al., 2021, Islam et al., 2022). In other studies, unique findings on equitable effectiveness arose, such as for learners with visual or hearing impairments (Ananga et al., 2021, Hodor et al., 2021) and learners from tribal or religious minorities (Hodor et al., 2021).

Access to, and effective use of, EdTech was found to be differentiated based on gender in eight studies. Studies evidenced varied gendered findings, and teachers and caregivers were often the ones exhibiting gender biases. In Pakistan, gender inequity was high, and 29% of caregivers did not allow girls to have access to EdTech for cultural, religious, and financial regions (Adil et al., 2021). In Bangladesh, gender differences were noted where 77% of male respondents had internet access (in comparison to 59% of female respondents) and 56% of male respondents used devices for education (in comparison to 44% of female respondents). By contrast, a study in Kenya found that no major differences were reported in their household surveys, although, at a community level, the education of males took precedence over that of females, implying that if a choice had to be made when resources are limited, boys would be prioritised. (Tembey et al., 2021). Building on existing literature that argues that girls engage and benefit more than boys when provided with the same level of access to technology (Webb et al., 2020, as cited in Tembey et al., 2021), Islam et al. (2021) noted similar evidence. A particularly thought-provoking, gender-specific finding in Ghana was that female tutors were harder on themselves in assessing their performance, yet they outperformed their male counterparts on more difficult teaching components such as student–teacher participation and critical thinking (Ananga et al., 2021).

To provide access to educational offerings in rural and remote settings during the pandemic, radio, TV and IVR were used. Rural settings are often characterised by low connectivity, lower literacy and education levels, lower income or dependence on farming, longer distances to walk to school, and learners having less time due to supporting their parents’ work (e.g., farming or caregiving). In Ghana, the national TV programme had more coverage in comparison to the radio programme due to the unavailability or poor quality of radio stations (Hodor et al., 2021). In both programmes, learners felt they needed a slower pace, more interactivity and repeated programming (ibid.).

To increase interactivity in hard-to-reach areas, IVR was used in studies in Ghana and Bangladesh (Afoakwah et al., 2021, Islam et al., 2022). The Ghana IVR intervention in rural areas had the highest completion rates, and this was attributed to highly invested School Leaders who embraced the intervention; this emphasises again that EdTech needs to be coupled with human support and motivation (Afoakwah et al., 2021). The same was found in the IVR study in Bangladesh, where improvements were attributed to motivated caregivers who were nudged to engage in the children’s learning (Islam et al., 2022). While the treatment effects of the low-tech IVR in lower-income quartiles were the largest in the Bangladesh study, it was noted that these solutions were less attractive to relatively well-off families who have more accessibility, illustrating the need for tailoring EdTech offerings to contextual factors and target-group preferences (ibid.). The need to tailor to contextual factors is also underscored by contrasting findings which emerged from a similar study also undertaken in Bangladesh. Beam et al. (2022) tested the impacts of SMS nudges to engage with online learning and educational TV, in addition to teacher outreach and reduction of internet costs. The SMS nudges were found to have positive effects on learning outcomes, higher socioeconomic tatus households benefitted to a greater extent (ibid.)

In terms of accessibility for learners with special educational needs and disabilities, some studies showed that when executed well, EdTech can support such learners in ways that cannot be possible in traditional face-to-face settings. In a Ghana study on pre-service teacher training, the online learning offering improved participation through easier access to digital resources (e.g., through voice initialising), ability to study independently, less travel time, recorded lessons for replay, and less dependence on friends and family (Ananga et al., 2021). Similarly, the television and radio programmes in Ghana also supported younger students with disabilities, such as through sign language in telecasting, provided these learners had adequate support based on their disability (Hodor et al., 2021).

While most of the studies reviewed the equitable nature of EdTech in the teaching and learning space, Fab Inc (2021) analysed this from a management and administration perspective in Sierra Leone. Through the analysis of Annual School Census datasets, national-level data on classroom sizes, enrolment, infrastructure, gender parity, and children with disabilities were able to be used to inform decision-making. The study concluded that the use of data to provide local analytics helps governments to develop tailored and localised solutions such that vulnerable and marginalised groups can be prioritised.

Moving beyond access to equitable benefits, some studies explicitly focused on information sharing as a strategy to increase use. The use of information and behavioural nudges was also a notable focus for research in the wider field, such as the World Bank Strategic Innovation Evaluation Fund, as part of Covid-19 responses (Beam et al., 2022, Crawfurd et al., 2021; Geven et al., 2021). Volunteers from Amenya et al.’s (2021) study in Kenya worked with communities and parents to sensitise them on the benefits of attending the reading camps, and this was seen as one of the main factors that made the reading camps work. However, the findings from Aurino et al.’s (2022) study had mixed results: behavioural nudges that were given through text messages on average “decreased caregiver engagement, decreased self-reported school enrollment and attendance, decreased caregiver mental health, and decreased children’s academic skills” (Aurino et al., 2022, p. 9). Upon disaggregation of data, the negative findings correlated with lower-income families, while more positive findings were correlated with caregivers who have some level of education. Reporting on a related part of the same intervention, Wolf and Aurino (2021) note that while boys’ education tended to be prioritised over girls’ in terms of engaging with remote learning, boys were less likely to be as encouraged to return to formal schooling. This example highlights the importance of being attentive to gender and intersectionality.

4.3. Cost and affordability

Cost is a critical issue not just in EdTech, but across all of education where prioritisation and investment choices need to be made (Beeharry, 2021). By collecting consistent information about the costs of interventions, and standardised measures of educational outcomes, comparable cost-effectiveness metrics can be produced (Bhula et al., 2020), such as Learning-Adjusted Years of Schooling (LAYS) (Angrist et al., 2020b). This may be of critical importance to educational decision-making in low-resource contexts, and initiatives such as the ‘Smart Buys’ seek to provide actionable advice based on cost-effectiveness metrics (GEEAP, 2020). However, there are also important debates about the extent to which cost-effectiveness can be transferable and practical challenges in relation to measuring the full costs associated with initiatives (Evans & Popova, 2016). Furthermore, in order to ensure educational progress is equitable and also reaches marginalised learners, additional costs may be necessary (Sabates et al., 2018, Zubairi et al., 2021). For EdTech, both capital and operational expenditure need to be considered to understand costs, affordability, and feasibility to scale (Mitchell and D’Rozario, 2022).

Amongst our Covid-19 studies, only Islam et al. (2022) provided formal calculations of cost-effectiveness for the intervention being studied. However, other studies discussed practical issues and experiences which have implications for the cost and affordability of interventions (e.g. Adil et al., 2021; Afoakwah et al., 2021; Amenya et al., 2021; Ananga et al., 2021; Aurino et al., 2022; Fab Inc., 2021; Hodor et al., 2021; Islam et al., 2021; Tembey et al., 2021). For example, several highlighted significant capital costs in investments of time and resources in set-up, stating that operational recurring costs could be reduced (e.g. Afoakwah et al., 2021). The studies also provided insight into the less visible costs associated with interventions (e.g. Amenya et al., 2021; Hodor et al., 2021).

Islam et al. (2022) provided a full cost-effectiveness analysis and made their data available. While the fixed cost of the IVR intervention per student was very high relative to the variable cost (total USD 27.5 per student over 15 weeks for 1,182 students in two districts). In terms of costs, fixed and variable costs associated with the programme were recorded, so an average cost per student could be estimated; "Variable costs were voice and SMS charges, household reach-out expenditure, etc., and fixed costs were IVR platform development, content development, programme management expenditure, etc." (Islam et al., 2022, p.44). The impact on learning outcomes followed the framework set out by Angrist et al. (2020b) to express learning gains in terms of LAYS. Hence, cost-effectiveness could then be calculated in terms of the number of LAYS gained per USD 100 spent. As part of this more detailed cost-effectiveness analysis, Islam et al. (2022) emphasised that scaling further could drive cost down.

The use of LAYS as a cost-effectiveness metric allows comparisons to be drawn alongside a wide range of other EdTech and non-EdTech interventions. Islam et al. (2022) reported that both interventions tested resulted in learning gains equivalent to “2.21 SD (or 2.16 LAYS) per USD 100 of spending for the Standard group and 2.37 SD (or 2.31 LAYS) for the Extended group” (Islam et al., 2022, p.3). Note that the Standard group received literacy and numeracy modules, while the Extended group received a transferable skills module in addition to literacy and numeracy content. In comparison with the range of initiatives with impacts expressed as LAYS gained per USD 100 as reported by Angrist et al. (2020b; Figure B1, p.40), these figures would place the intervention approximately within the top third of interventions plotted.

Although Islam et al. (2022) is the only example which provided cost-effectiveness calculations, cost more generally was discussed across the range of studies. A common issue was how to cover access to EdTech devices and data costs. Even where household ownership of mobile phones was high, including low-income households, internet and data costs remained a challenge (Adil et al., 2021, Islam et al., 2021, Islam et al., 2022). In low-resource settings, policymakers must consider costs relating to hardware alongside smaller costs that end-users face. This was also an issue for student teachers, who Ananga et al. (2021) recommend should be provided with a monetary amount to cover the high cost of data to access virtual learning, and those affected by the device gap should also be provided smartphones. With the return to schooling, it is also important to consider what cost effectiveness is being consider relative to, and whether there are any trade-offs in provision. For example, Schueler and Rodriguez-Segura (2021) report on the use of a telementoring intervention in Kenya, following a similar model to Angrist et al. (2020a), but undertaken as schools reopened. For students who returned to in-person education, telementoring was not beneficial, as “tutoring substituted away from more productive uses of time, at least among returning students” (Schueler & Rodriguez-Segura, 2021, p.1).

Changes in household costs from EdTech participation varied, underscoring the need to consider context carefully and the risks of over-generalising. In one study, the intervention reduced household costs; having learners engaging with educational television and radio programmes helped to reduce the cost burden of hiring a private teacher, however, in rural areas, there were limited radio stations, making accessing a radio signal more challenging (Hodor et al., 2021). While diversifying language in the interventions was a suggestion to improve learning comprehension, there are many languages in Ghana, which would make this adaptation costly (ibid.) Conversely, the need to access devices incurred further costs to households in another study. Neighbours allowed girls to use their radios and other devices but charged a fee for it, limiting girls’ access (Amenya et al., 2021). The studies also noted the importance of carefully considering the validity of cost comparisons, and that the appropriate benchmarks need to be considered in context. Aurino et al. (2022) recommend further research on how one-directional text-based interventions compare with other interventions, such as in-person community dialogue with parents, for example. Tembey et al. (2021) note that EdTech can be more cost-effective for the user than buying textbooks but requires changing entrenched perceptions about what constitutes appropriate learning materials (Tembey et al., 2021). The example of developing an educational data dashboard in Sierra Leone provides unique reflections on technical development and ongoing costs, with a main choice at the outset being between coding a bespoke dashboard and utilising providers of business analytics software and the licences involved (Fab Inc., 2021).

4.4. Implementation context

While school-effectiveness literature has over the years tended to emphasise context in explaining performance (Hopkins et al., 1997, Reynolds, 2010), more recently, there is a sense that this focus has largely disappeared. Accounts of high-performing education systems have advanced the idea that replication can lead to better educational outcomes and performance (Barber et al., 2010, Mourshed et al., 2010). This logic discounts the complexity of education systems as well as the contextual and cultural boundaries in which they operate (Harris, et al., 2015). Despite the powerful influence of contextual factors on learning, understanding which factors are more effective is scarce and inconclusive, partly because it is difficult to generalise ‘what works’ (Bates and Glennerster, 2017, Glewwe et al., 2020). For EdTech, this challenge of attribution, as well as the uptake of evidence and integration into practice equally, is mediated by a contextual and complex ecosystem of issues (Pellini et al., 2021). Ultimately, greater use of technology is only one approach to improving teaching and learning, and as such needs to be tackled from a systems perspective (Bapna, et al., 2021).

While none of our studies were focused on the systems level or explicitly sought to address issues of political economy, the variation in learning outcomes noted in Section 4.1 underscores the importance of considering interventions holistically and being attentive to contextual factors. All our studies provide valuable insights into contextual factors which played a role; while acknowledging that examples are specific, they also help to shed light on the types of additional factors to be considered within the design of EdTech programmes in a different context.

The difficulties in EdTech access were emphasised in all studies, with issues of devices, data, and connectivity – including hardware, end-user costs and electricity - seen as base determinants in relation to effectiveness. For example, in Ghana, Ananga et al. (2021) found that nine out of ten teachers had poor internet access, which limited their ability to attend teacher training synchronously. In Kenya, participant access to stable electricity and connectivity facilitated their engagement with digital content (Tembey et al., 2021). Some studies show that attempting to deliver EdTech programmes in areas lacking essential services may have a negative impact; Aurino et al. (2022) noted that receiving behavioural nudges to engage in interventions without having the relevant resources increased caregiver stress. Access challenges were identified for girls, linked to social norms and balancing other obligations (see Section 4.2).

One of the key findings from Amenya et al. (2021) highlights the importance of considering how EdTech is being used alongside other educational activities and how that impacts learning outcomes. The intervention in Kenya examined the use of television and radio lessons for girls, either in conjunction with or without reading camps. Participation in reading camps was associated with significant gains in both numeracy and literacy; however, “The use of radio and television lessons was not significantly associated with higher learning outcomes, except where girls accessed media as a group outside of camps” (Amenya et al., 2021, p.8). The combination of the added radio component to the reading camp and the peer learning group was the only time that the radio lessons were found to improve performance (ibid.).

Afoakwah et al. (2021), Hodor et al. (2021) and Islam et al. (2021) all noted the important role that parents play in facilitating students’ access to content. Given the central role of parents, an important aspect of content tailoring was to ensure messages and supporting materials were appropriate for the educational background of the caregivers (Aurino et al., 2022). Moreover, studies identified that parental traits – digital skills, language literacy, confidence, and motivation – all impact their intention and ability to support their children to engage with EdTech tools (Adil et al., 2021, Amenya et al., 2021, Aurino et al., 2022, Hodor et al., 2021, Islam et al., 2021, Tembey et al., 2021). This means that EdTech interventions will likely be more effective when they help build parental confidence and self-efficacy in supporting technology-enabled learning.

Perceptions of the quality of educational materials and content delivered through EdTech were also found to be important contextual elements. The studies often revealed that non-academic design decisions – such as the language of instruction, speaking style and speed of delivery – were key perceived indicators of quality (Afoakwah et al., 2021). Tembey et al. (2021) found that making the links between EdTech tools and national curricula increased parental confidence in the quality and appropriateness of the resources provided. Once teachers and parents have access to high-quality content, they are able to ensure that it is accessible to students in a variety of innovative ways. In Ghana and Pakistan, teachers used WhatsApp to share content during school closures (Adil et al., 2021, Hodor et al., 2021). One study in Bangladesh used IVR to provide lessons by feature phone; in another study, students expressed a preference to receive content via online platforms including Facebook, YouTube, Zoom and Google Meet (Islam et al., 2022, Islam et al., 2021). Finally, in Kenya, educational experiences were provided via television (Tembey et al., 2021).

The studies also demonstrate that EdTech tools can be used to establish and strengthen communication channels and chains of connections between teachers, parents and caregivers, and communities. Tembey et al. (2021) highlighted the importance of teacher-to-caregiver connections through easily accessible touch points – such as from teachers, resource packs, and lists of digital tools – to gain technical advice and answers to content questions for their children. Similarly, Aurino et al., 2022 suggest this could be achieved at low cost by targeting caregivers with informal check-ins, messaging and learning content (i.e., by phone, text message, IVR audio lessons) that are timed and tailored to their backgrounds and social contexts (e.g., language, education level). Nudges and incentives for parent and caregiver engagement, particularly female caregivers, were found to have an impact to an extent (e.g., Tembey et al., 2021). Examples within the studies also show that community involvement can be crucial in addition to links between teachers and caregivers (Amenya et al., 2021, Hodor et al., 2021).

Co-design processes can help foster social factors, including awareness of technology as an educational tool and cultural openness to using EdTech to support learning (Adil et al., 2021, Islam et al., 2021, Tembey et al., 2021). The studies demonstrated that not only is co-design helpful to increase social alignment and support eventual uptake, but it also generates important feedback about how interventions can be made more effective. Listening to user needs to understand design features such as flexibility in the time of day and tailoring interventions to educational background, language, and reading level were emphasised. The importance of localisation of EdTech interventions was also highlighted, for instance, in terms of speaking style, speed, and repetition of lessons. Ananga et al. (2021) highlighted how a better understanding of gender dimensions helps tailor support to enable female pre-service teachers to engage more effectively. Similarly, Tembey et al. (2021) found that co-designing interventions helped to address parents’ concerns about online safety and inappropriate use of technology in parallel to learning.

4.5. Alignment and scale

EdTech effectiveness at scale is likely to depend to some extent on alignment with education systems and sector plans (Hollow and Jefferies, 2022). However, even when aligned, a key challenge that the EdTech sector has faced is so-called ‘pilotitis’, where many pilot projects do not lead to scale (Principles for Digital Development, 2022). Other reasons why EdTech often does not scale include a lack of evidence-based designs, limited end-user involvement, limited funding, a focus on the product or tech as opposed to the problem, and a lack of a strategic approach from governments (Gove et al., 2017, Simpson et al., 2021). Drawing on EdTech scaling initiatives in Chile, China, Indonesia, and the United States of America, Omidyar Network (2019) developed a model for equitable EdTech scaling that outlines four categories: 1) demand-led EdTech supply and sustainable models; 2) enabling infrastructure; 3) education policy, strategy, action-planning, and financing, and 4) human capacity and multi-stakeholder collaboration to bring the vision to fruition. From an education system perspective, the Tusome project was a technology-enabled education intervention in Kenya successfully scaled using Crouch and DeStefano’s (2017) framework that outlines three core functions to enable large-scale education change (1) setting and communicating expectations, (2) monitoring and guaranteeing accountability for meeting those expectations, and (3) intervening to ensure the support needed to assist students and schools that are struggling (Piper et al., 2018).

While the studies selected in our portfolio showed signs of alignment with national systems and potential to reach scale due to low-tech and/or cost-effective EdTech offerings, the short study period meant that interventions didn’t move to scale during these timeframes, with the exception of Hodor et al. (2021), which evaluated the national Ghanaian remote learning programmes, and Adil et al. (2021), which evaluated the impact of low-tech solutions in Bahawalnagar district in Pakistan. Still, the studies highlighted a variety of insights that speak to these issues.

Several studies found that when the EdTech offering is embedded into existing systems and processes (as opposed to an add-on), it increases uptake (Adil et al., 2021, Hodor et al., 2021, Islam et al., 2022, Tembey et al., 2021). The systems could be education-related, for example, working with educational activities already used, or technological systems, for example, using instant messaging like WhatsApp that has already penetrated into a community (Hodor et al., 2021). When linked to school curricula, sustainable benefits observed included increased student engagement, increased use of EdTech offerings and more motivation (Adil et al., 2021, Afoakwah et al., 2021). To ensure sustainability at a national scale, interventions need to be aligned with national curricula, scheduling, strategies, and action plans (Ananga et al., 2021). This was illustrated in Kenya, where mapping resources to the national curricula was a key step toward parental acceptance and potential sustainability. In some cases, when well aligned, the intervention or research is then able to feed back into strategic policies to improve them (Fab Inc, 2021, Hodor et al., 2021).

Building on guidelines from Omidyar Network (2019) that emphasise the importance of having a national information and communications technology (ICT) backbone (i.e., electricity, telecommunication infrastructure and internet access) in place to support scaling of EdTech use for all, studies identified similar leverage points. For example, in Ghana’s pre-service teaching colleges, the internet was provided by Ghana Tertiary Education Commission (GTEC) and Transforming Teacher Education and Learning (T-TEL) on campuses, enabling the intervention to reach more students, with ongoing work to tackle the issue of internet connectivity more broadly (Ananga et al., 2021).

In unpacking barriers to scaling, some studies sought to uncover why EdTech use is limited, even when there is accessibility. Islam et al. (2021) outlined reasons such as lack of trust, lack of permission to use devices, limited technical knowledge and digital literacy, lack of interest and lack of a formal offering by an educational institution. Relatedly, parents’ literacy and digital literacy impacted use, either due to their reluctance to allow their children to use devices or their limited ability to support their children (Adil et al., 2021, Tembey et al., 2021). Hodor et al. (2021) and Tembey et al. (2021) similarly outlined a lack of awareness and advertising of educational offerings. In some cases, the educational benefits of technology are not apparent to users who associate devices with entertainment or socialising (Adil et al., 2021).

As shifts back to in-person learning began, a common theme from our studies was that learners and teachers who had used EdTech had hopes that remote learning could shift to blended learning, combining in-person teaching and learning with technology. Some learners emphasised that EdTech-enabled distance learning was no replacement for in-person learning (Adil et al., 2021, Islam et al., 2021); others said they would like a hybrid approach with in-person learning supplemented by EdTech (Islam et al., 2021). In Ghana, as schools opened, 15% of teachers interviewed had transitioned to blended learning (Hodor et al., 2021). Some teachers encouraged learners to participate in the national TV and radio remote learning programmes, and others incorporated radio broadcasting into the school timetable, following it with support and activities (ibid). While most stakeholders in Ananga et al.’s (2021) study are confident to move forward with blended learning, they cautioned that demonstrations and exams are better done in person. This stresses the need for interventions to investigate the most effective mix of digital, remote, and face-to-face learning that suits the context and purpose, noting macroscopic factors such as political will and institutional capacity that also come into play (Poirier et al., 2019)

5. Conclusions

While the issue of school closure — one of the most acute aspects of the educational crisis during the pandemic – has passed, EdTech has also played a role as part of the return to schooling. With the use of EdTech increasingly used to support teaching and learning, there is an ever-mounting need to consider the determinants of effectiveness in technology-based education interventions. This paper illustrates the use of a holistic framework to understand EdTech effectiveness, drawing on ten primary research studies conducted during Covid-19 in low-resource settings. The framework considers multiple perspectives, including impact on learning outcomes, enhancing equity, cost and affordability, implementation context, and alignment and scale. By applying this framework, our findings highlight the valuable insights that can be gained and uncovered through a holistic approach to effectiveness.

Understanding EdTech effectiveness through the lens of learning outcomes is a starting point, but neither straightforward nor sufficient. Overall, mixed results from our studies underline a need for additional and more nuanced data to understand variations, underscoring the importance of mixed-methods studies. While studies largely used existing assessment tools focused on foundational literacy and numeracy, their experience demonstrates that standardised tools should be used alongside context-specific educational measures. A need for comparative work on the specific affordances of different forms of EdTech also emerged, for example, in relation to learning outcomes in different subject areas. Learner preference for interactive pedagogy of social media and group learning was a further insight important in supporting learning gains.

The Covid-19 pandemic has shown how educational inequalities can be exacerbated for teachers and learners who do not have the ability to access and utilise online and digital modes of learning. Analysis of our studies in making EdTech more effective from an equity lens reveals lessons in relation to specific groups; this includes gender biases against girls and young women, the role of facilitators and caregivers in rural and hard-to-reach settings, and adaptive approaches and tech important for learners with disabilities. The role that data plays in advancing equity and the importance of moving from EdTech access to equitable benefit also emerged. Given that studies using seemingly similar EdTech approaches observed different impacts in different contexts, it is clear that there is no silver bullet approach to designing for equity. While much research has focused on equity in terms of access, more is needed on how to support the equitable benefit of EdTech.

A better understanding of cost and affordability are similarly critical to the effectiveness of EdTech. With only one study in our sample fully calculating measures of cost-effectiveness, this is surely an area where more effort and research are needed, given the potential for comparison it offers. In addition, our studies highlight the need to view cost over time, as an early intervention at a smaller scale will have much higher costs, and to consider the stage at which cost was calculated, to ensure comparisons are like-for-like. With the potential to scale often being cited as a rationale for EdTech cost-effectiveness, it is important to consider other issues such as upfront investment alongside ongoing costs and develop a fuller picture of metrics, financing, household costs and alternative comparisons. Research gaps in this area include the need for guidance for comparable costing, as well as conducting and greater sharing of cost-effectiveness analyses and how these can be consistently applied.

Additional insight on the effectiveness of EdTech can be found in considering the context. In the low-resource settings of our studies, barriers to EdTech access are prevalent and overcoming these remains central, but not sufficient, to effectiveness. Several of our studies showed that the use of EdTech alongside other group-based interventions can positively impact learning outcomes, whereas a technology-based intervention on its own is less effective. Moreover, with Covid-19-related school closures having forced a shift in parents’ and caregivers’ roles in their children’s learning, their perceptions of the quality of an EdTech offering and the importance of regular communication channels is critical. Many of the studies also emphasised that for EdTech offerings to be effective in context, co-design with relevant stakeholders is important. Thus, a critical research gap in relation to context centres around the rigour and pacing of co-design, ensuring this is better based on evidence rather than anecdote.

An indication of effectiveness is also found in the degree to which EdTech aligns and scales. The presence of a national ICT backbone is an important piece, but it alone is not enough. Alignment with national curricula was highlighted in several of our studies as an important aspect of EdTech acceptance that could facilitate acceptance and scaling. Further practices that can support scaling in equitable ways were identified, such as improving the digital literacy of learners and teachers, involving parents and caregivers, and explicitly explaining the educational purposes of EdTech. Moving forward, increased adoption of blended learning is seen both as desirable and as a way toward further scale. With EdTech increasingly included in national education plans, further research is needed on how governments and other actors can foster an EdTech ecosystem that aligns and scales to their priorities.

Together, greater insight into each of these five elements can paint a fuller picture of the effectiveness of EdTech. While the studies focused upon the continuation of learning during the pandemic, the findings also have practical implications for the return to schooling. In terms of learning outcomes, the use of assessment tools and demonstrated efficacy of short-term EdTech interventions are affordances which could be utilised to assist with identifying learning losses and providing targeted additional support for learners who have experienced losses to a greater extent. However, the discussions in relation to equity are a reminder that any EdTech intervention alongside a return to schooling needs to be carefully considered within its context. Cost-effectiveness raises questions about what EdTech interventions should be considered relative to, in the return to schooling (e.g. Schueler & Rodriguez-Segura, 2021). In relation to both implementation and scale, the discussion points to the role of teachers, as co-designers and facilitators of a more blended approach to education.

Overall, our analysis underscores that having access to technology is only a very small part of effectiveness, with wider elements deserving as much, if not more, attention. It also suggests that EdTech works best with designs that explicitly incorporate co-creation (with users) and contextualisation and that address equity issues from the onset. Insights from further applications of this framework will be relevant for policymakers continuing to integrate technology into education systems during any ongoing closures and beyond.

Uncited references

(GEEAP. Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel, 2020, GEEAP. Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel, 2022, UNESCO, 2022, World Bank, 2021)

CRediT authorship contribution statement

SN: Conceptualization; Writing - Original Draft; Writing - Review & Editing; Visualization; Supervision. KJ: Conceptualization; Writing - Original Draft; Writing - Review & Editing; Visualization. CM: Conceptualization; Writing - Original Draft;TA: Writing - Original Draft; Writing - Review & Editing. TK: Writing - Original Draft.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded through the work of The EdTech Hub (http://www.edtechhub.org). Many thanks to all the authors of the Covid-19 grant reports and participants in the studies, as well as Kate Jefferies, Chris McBurnie and Asma Zubairi, who played a role along with this paper’s authors in supporting the research. Further thanks go to Kate Jefferies and Ashley Stepanek Lockart for their work on a linked paper and Mike Trucano for his feedback on an earlier version of our analysis.

References

- Adam T. Digital literacy needs for online learning among peri-urban, marginalised youth in South Africa. International Journal of Mobile and Blended Learning. 2022;14(3):1–19. doi: 10.4018/IJMBL.310940. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Addey C., Sellar S., Steiner-Khamsi G., Lingard B., Verger A. The rise of international large-scale assessments and rationales for participation. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education. 2017;47(3):434–452. [Google Scholar]

- Adil F., Nazir R., Akhtar M. Investigating the impact on learning outcomes through the use of EdTech during Covid-19: Evidence from an RCT in the Punjab province of Pakistan. EdTech Hub. 2021 doi: 10.53832/edtechhub.0067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Afoakwah E., Carballo F., Caro A., D’Cunha S., Dobrowolski S., Fallon A. Dialling up learning: Testing the impact of delivering educational content via interactive voice response to students and teachers in Ghana. EdTech Hub. 2021 doi: 10.53832/edtechhub.0051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amenya D., Fitzpatrick R., Njeri M., E., Naylor R., Page E., Riggall A. The power of girls’ reading camps: Exploring the impact of radio lessons, peer learning and targeted paper-based resources on girls’ remote learning in Kenya. EdTech Hub. 2021 doi: 10.5281/zenodo.5651935. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ananga E., Kadiri A.-K., Kporwodu M., Nkrumah Y., Whajah F., Tackie M. T-TEL COVID-19 impact assessment study. EdTech Hub. 2021 doi: 10.5281/zenodo.4895400. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade H.L., Brookhart S.M., Yu E.C. Classroom assessment as co-regulated learning: A systematic review. Frontiers in Education. 2021;6 doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.751168. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, K. (2019). Strengthening learning assessment systems. A knowledge and innovation exchange (KIX) discussion paper. Global Partnership for Education. https://www.globalpartnership.org/content/strengthening-learning-assessment-systems-knowledge-and-innovation-exchange-kix-discussion-paper

- Angrist N., Bergman P., Brewster C., Matsheng M. Stemming learning loss during the pandemic: A rapid randomized trial of a low-tech intervention in Botswana. SSRN. 2020 〈https://www.ssrn.com/abstract=3663098〉 [Google Scholar]

- Angrist N., Evans D.K., Filmer D., Glennerster R., Rogers F.H., Sabarwal S. A comparison of 150 interventions using the new learning-adjusted years of schooling metric. World Bank; 2020. How to improve education outcomes most efficiently? [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Angrist N., Djankov S., Goldberg P.K., Patrinos H.A. Measuring human capital using global learning data. Nature. 2021;592:403–408. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03323-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appels L., De Maeyer S., Faddar J., Van Petegem P. Capturing quality. Educational quality in secondary analyses of international large-scale assessments: a systematic review. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 2022;33(4):629–668. [Google Scholar]

- Aurino E., Tsinigo E., Wolf S. Nudges to improve learning and gender parity: Preliminary findings on supporting parent-child educational engagement during Covid-19 using mobile phones. EdTech Hub. 2022 doi: 10.53832/edtechhub.0083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bapna A., Nicolai S., Myers C., Pellini A., Sharma N., Wilson S. A case for a systems approach to EdTech. EdTech Hub. 2021 doi: 10.5281/zenodo.5651995. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barber M., Moffit A., Kihn P. Corwin Press; 2010. Deliverology 101: A field guide for educational leaders. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett I., Ariana P., Petrou S., Penny M.E., Duc L.T., Galab S., Woldehanna T., Escobal J.A., Plugge E., Boyden J. Cohort profile: The Young Lives study. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2013;42(3):701–708. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, A.M. (2016). Measuring learning outcomes and education for sustainable development: The new Education Development Goal. In W.C. Smith (Ed.), The Global Testing Culture: Shaping Education Policy, Perceptions, and Practice. Symposium Books, pp. 101-114.

- Barron Rodriguez M., Cobo C., Munoz-Najar A., Sanchez Ciarrusta I. World Bank; 2021. Remote learning during the global school lockdown: Multi-country lessons.〈https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/36141〉 [Google Scholar]

- Bates, M.A., & Glennerster, R. (2017). The Generalizability Puzzle (SSIR). Stanford Social Innovation Review, Summer. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/the_generalizability_puzzle

- Beam, E., Mukherjee, P., & Navarro-Sola, L. (2022). Lowering barriers to remote education: Experimental impacts on parental responses and learning (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. 4234910). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4234910

- Beeharry G. The pathway to progress on SDG 4 requires the global education architecture to focus on foundational learning and to hold ourselves accountable for achieving it. International Journal of Educational Development. 2021;82 doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2021.102375. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhula, R., Mahoney, M. & Murphy, K. (2020). Conducting cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA). J-PAL. 〈https://www.povertyactionlab.org/resource/conducting-cost-effectiveness-analysis-cea〉

- Bozkurt, A., Jung, I., Xiao, J., Vladimirschi, V., Schuwer, R., Egorov, G., Lambert, S., Al-Freih, M., Pete, J., Don Olcott, J., Rodes, V., Aranciaga, I., Bali, M., Alvarez, A.J., Roberts, J., Pazurek, A., Raffaghelli, J.E., Panagiotou, N., Coëtlogon, P. de, … Paskevicius, M.. (2020). A global outlook to the interruption of education due to COVID-19 pandemic: Navigating in a time of uncertainty and crisis. Asian Journal of Distance Education, 15(1), Article 1. https://www.asianjde.com/ojs/index.php/AsianJDE/article/view/462

- Chuang, R., Coflan, C., Giraldo, J.-P., Attfield, I. & Tungatarova, A. (2022). National EdTech strategies: what, why, and who. EdTech Hub. 〈https://edtechhub.org/2022/02/18/national-edtech-strategies/〉

- Cohen L., Manion L., Morrison K. In: Research Methods in Education. Cohen L., Manion L., Morrison K., editors. Routledge; 2007. Content analysis and grounded theory. [Google Scholar]

- Crawfurd, L., Evans, D.K., Hares, S., & Sandefur, J. (2021). Teaching and testing by phone in a pandemic (Working Paper No. 591). Center for Global Development. https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/teaching-and-testing-phone-pandemic.pdf

- Crouch, L., & DeStefano, J. (2017). Doing reform differently: Combining rigor and practicality in implementation and evaluation of system reforms. RTI International. 〈https://www.rti.org/publication/doing-reform-differently〉

- Dreesen, T., Akseer, S., Brossard, M., Dewan, P., Giraldo, J., Kamei, A., Mizunoya, S., & Ortiz, J. (2020). Promising practices for equitable remote learning: Emerging lessons from COVID-19 education responses in 127 countries. UNICEF. 〈https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/IRB%202020-10%20CL.pdf〉

- EdTech Hub. (2022). Our strategy, part 2: Deep dive into our approach, focus countries, and theory of change. EdTech Hub. https://edtechhub.org/2022/02/28/our-strategy-part-2-deep-dive-into-our-approach-focus-countries-and-theory-of-change/

- Evans D.K., Popova A. Technical Report 7203. The World Bank; 2015. What really works to improve learning in developing countries? An analysis of divergent findings in systematic reviews.〈https://ideas.repec.org/p/wbk/wbrwps/7203.html〉 [Google Scholar]

- Evans D.K., Popova A. Cost-effectiveness analysis in development: Accounting for local costs and noisy impacts. World Development. 2016;77:262–276. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.08.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fab Inc Learning from experience: A post-Covid-19 data architecture for a resilient education data ecosystem in Sierra Leone. EdTech Hub. 2021 doi: 10.5281/zenodo.5498054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glewwe, P., Lambert, S. & Chen, Q. (2020). Chapter 15 - Education production functions: updated evidence from developing countries. The Economics of Education (2nd Ed.). Academic Press, pp. 183-215. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-815391-8.00015-X

- GEEAP. Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel . FCDO. World Bank; 2020. Cost effective approaches to improve global learning: What does recent evidence tell us are “Smart Buys” for improving learning in low- and middle-income countries? Recommendations of the Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel; p. BE2.〈https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/719211603835247448/pdf/Cost-Effective-Approaches-to-Improve-Global-Learning-What-Does-Recent-Evidence-Tell-Us-Are-Smart-Buys-for-Improving-Learning-in-Low-and-Middle-Income-Countries.pdf〉 [Google Scholar]

- GEEAP. Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel . FCDO, and UNICEF Office of Research - Innocenti. World Bank; 2022. Prioritizing learning during COVID-19: The most effective ways to keep children learning during and postpandemic.〈https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/114361643124941686/pdf/Recommendations-of-the-Global-Education-Evidence-Advisory-Panel.pdf〉 [Google Scholar]

- Gove A., Korda Poole M., Piper B. Designing for scale: Reflections on rolling out reading improvement in Kenya and Liberia. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2017;2017(155):77–95. doi: 10.1002/cad.20195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham M., De Sabbata S., Zook M.A. Towards a study of information geographies: (Im)mutable augmentations and a mapping of the geographies of information. Geo: Geography and Environment. 2015;2(1):88–105. doi: 10.1002/geo2.8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hale T., Angrist N., Goldszmidt R., Kira B., Petherick A., Phillips T., Webster S., Cameron-Blake E., Hallas L., Majumdar S., Tatlow H. A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(4), Article. 2021:4. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haßler, B., Nicolai, S., McBurnie, C., Jordan, K., Wilson, S., & Kreimeia, A. (2020). EdTech and COVID-19 response [Save Our Future] (Background Paper No. 3; #SaveOurFuture). Education Commission. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3983877

- Harris A., Adams D., Jones M.S., Muniandy V. System effectiveness and improvement: the importance of theory and context. School Effectiveness and School Improvement. 2015;26(1):1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Hodor R., Owusu E.A., Ofori-Davis L., Afram A., Sefa-Nyarko C. Voices and evidence from end-users of the GLTV and GLRRP remote learning programme in Ghana: Insights for inclusive policy and programming. EdTech Hub. 2021 doi: 10.53832/edtechhub.0064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hollow D., Jefferies K. How EdTech can be used to help address the global learning crisis: A challenge to the sector for an evidence-driven future. EdTech Hub. 2022 doi: 10.53832/edtechhub.0115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- HolonIQ. (2021). $16.1B of global EdTech venture capital in 2020. HolonIQ. 〈https://www.holoniq.com/notes/16-1b-of-global-edtech-venture-capital-in-2020〉

- HolonIQ. (2022). Global EdTech VC funding - Q1 2022 update. HolonIQ. 〈https://www.holoniq.com/notes/global-edtech-vc-funding-2022-q1-update〉

- Hopkins D., Harris A., Jackson D. Understanding the school’s capacity for development: Growth states and strategies. School Leadership & Management. 1997;17:401–412. [Google Scholar]

- Islam A., Wang L.C., Hassan H. Delivering remote learning using a low-tech solution: Evidence from an RCT during the Covid-19 Pandemic. EdTech Hub. 2022 doi: 10.53832/edtechhub.0070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Islam T., Hussain M., Shimul S.N., Rupok R.I., Orthy S.R.K. Integration of technology in education for marginalised children in an urban slum of Dhaka City during the Covid-19 Pandemic. EdTech Hub. 2021 doi: 10.53832/edtechhub.0063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McEwan P.J. Improving learning in primary schools of developing Countries: A meta-analysis of randomized experiments. Review of Educational Research. 2015;85(3):353–394. doi: 10.3102/0034654314553127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mourshed, M., Chijioke, C., & Barber, M. (2010). How the world’s most improved school systems keep getting better. McKinsey and Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/industries/public%20and%20social%20sector/our%20insights/how%20the%20worlds%20most%20improved%20school%20systems%20keep%20getting%20better/how_the_worlds_most_improved_school_systems_keep_getting_better.pdf

- Munoz-Najar A., Gilberto A., Hasan A., Cobo C., Azevedo J.P., Akmal M. International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; 2021. Remote learning during Covid-19: Lessons from today, principles for tomorrow.〈https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/160271637074230077/pdf/Remote-Learning-During-COVID-19-Lessons-from-Today-Principles-for-Tomorrow.pdf〉 [Google Scholar]

- Omidyar Network. (2019). Scaling access & impact: Realizing the power of EdTech. Omidyar Network. https://assets.imaginablefutures.com/media/documents/ON_Scaling_Access__Impact_2019_85x11_Online.pdf

- Pellini A., Nicolai S., Magee A., Sharp S., Wilson S. A political economy analysis framework for EdTech evidence uptake. EdTech Hub. 2021 doi: 10.5281/zenodo.4540204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pier, L., Hough, H.J., Christian, M., Bookman, N., Wilkenfeld, B., & Miller, R. (2021). Covid-19 and the educational equity crisis: Evidence on learning loss from the CORE data collaborative. Policy Analysis for California Education. 〈https://edpolicyinca.org/newsroom/covid-19-and-educational-equity-crisis〉

- Piper B., Destefano J., Kinyanjui E.M., Ong’ele S. Scaling up successfully: Lessons from Kenya’s Tusome national literacy program. Journal of Educational Change. 2018;19(3):293–321. doi: 10.1007/s10833-018-9325-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pisani L., Borisova I., Dowd A.J. Developing and validating the International Development and Early Learning Assessment (IDELA. International Journal of Educational Research. 2018;91:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2018.06.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Platas, L.M., Ketterlin-Gellar, L., Brombacher, A., & Sitabkhan, Y. (2014). Early Grade MathematicsAssessment (EGMA) toolkit. RTI International. 〈https://shared.rti.org/content/early-grade-mathematics-assessment-egma-toolkit〉

- Poirier M., Law J.M., Veispak A. A spotlight on lack of evidence supporting the integration of blended learning in K-12 education: A systematic review. International Journal of Mobile and Blended Learning. 2019;11(4):1–14. doi: 10.4018/IJMBL.2019100101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Principles for Digital Development. (2022). Principles for digital development. Principles for Digital Development. https://digitalprinciples.org/

- Renzulli J.S., Smith L.H., White A.J., Callahan C.M., Hartman R.K., Westberg K.L. Technical and administration manual. Routledge; 2002. Scales for rating the behavioral characteristics of superior students. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, D. (2010). Failure-free education? The past, present and future of school effectiveness and school improvement. Routledge.

- Rodriguez-Segura, D. (2020). Educational technology in developing countries: A systematic review (No. 72; EdPolicyWorks Working Paper). University of Virginia. https://education.virginia.edu/documents/epwworkingpaper-72edtechindevelopingcountries1202-08pdf