Abstract

This cohort study evaluates characteristics associated with early-onset cannabis use.

Early-onset cannabis use is common (eg, 12% of 14- to 15-year-olds in the US report lifetime use) and is associated with increased risk for cannabis use disorder, other psychiatric disorders, and other problems (eg, early school dropout) during childhood and adulthood.1,2 Prospective risk factors of early-onset cannabis use remain poorly understood. Here, using data from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study,3 we identified characteristics associated with cannabis use initiation by early adolescence (mean [SD] age, 13.43 [0.62] years).

Methods

Participants provided assent and caregivers provided written informed consent to protocols approved by institutional review boards at each data collection site. We followed the (STROBE) reporting guideline for cohort studies. Associations between early-onset cannabis use (n = 170 [1.56%]), defined as endorsement of cannabis use beyond a puff in any form (ie, smoking cannabis, consuming edibles, and using concentrates, oils, or tinctures) reported at any assessment (baseline [June 1, 2016, to October 15, 2018] to 3.5-year follow-up sessions) and psychopathology, personality, and cognition as well as cannabis-related familial, environmental, and peer variables (n = 46; eMethods in Supplement 1) were estimated using mixed-effect logistic regression models, nesting data by collection site (lme4 package in R version 4.2.1 [R Foundation]). The no cannabis use group was defined as those who had heard of cannabis by 2-year follow-up (mean [SD] age, 12.00 [0.66] years), but not used by 3.5-year follow-up (n = 10 711). Fixed-effect covariates included family and twin status as well as sociodemographic and parental variables significantly associated with cannabis use (Table and Figure caption).

Table. Baseline Sociodemographic and Parental Variable Comparisons for Cannabis Use Initiation Groups.

| Variable | No./total No. (%) | Nonparametric comparison, P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Used cannabis (n = 170) | Heard of but have not used cannabis (n = 10 711) | ||

| Sex | |||

| Female | 61/170 (35.9) | 5048/10 711 (47.1) | .004 |

| Male | 109/170 (64.1) | 5663/10 711 (52.9) | |

| Race and ethnicitya,b | |||

| Asian | 2/169 (1.2) | 232/10 684 (2.2) | <.001 |

| Black/African American | 31/169 (18.3) | 1715/10 684 (16.1) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 25/169 (14.8) | 531/10 684 (5.0) | |

| Native American/Alaska Native | NA | 36/10 684 (0.3) | |

| Pacific Islander | NA | 12/10 684 (0.1) | |

| White | 109/169 (64.5) | 8073/10 684 (75.6) | |

| Otherc | 2/169 (1.2) | 85/10 684 (0.8) | |

| Religious affiliationa,d | 117/161 (72.7) | 7447/10 235 (72.8) | >.99 |

| Parent marital statusa | |||

| Married/cohabiting | 104/169 (61.5) | 7909/10 628 (74.4) | .002 |

| Widowed | 2/169 (1.2) | 86/10 628 (0.8) | |

| Divorced/separated | 32/169 (18.9) | 1403/10 628 (13.2) | |

| Never married | 31/169 (18.3) | 1230/10 628 (11.6) | |

| Parent educationa | |||

| Less than high school | 16/170 (9.4) | 654/10 694 (6.1) | <.001 |

| High school/GED/some college | 64/170 (37.6) | 2814/10 694 (26.3) | |

| Undergraduate degree | 67/170 (39.4) | 4446/10 694 (41.6) | |

| Graduate degree | 23/170 (13.5) | 2780/10 694 (26.0) | |

| Household income, $a,e | |||

| <25 000 | 31/153 (20.3) | 1379/9823 (14.0) | <.001 |

| 25 000-49 999 | 39/153 (25.5) | 1419/9823 (14.4) | |

| 50 000-74 999 | 23/153 (15.0) | 1354/9823 (13.8) | |

| 75 000-99 999 | 19/153 (12.4) | 1431/9823 (14.6) | |

| 100 000-199 999 | 30/153 (19.6) | 3070/9823 (31.3) | |

| ≥200 000 | 11/153 (7.2) | 1170/9823 (11.9) | |

| Participant age at baseline, mean (SD), y | 10.2 (0.6) | 9.9 (0.6) | NAg |

| Parent age at baseline, mean (SD), yf | 39.6 (7.9) | 40.2 (6.8) | .045 |

Abbreviations: GED, general educational development test; NA, not applicable.

Group comparison conducted using Fisher exact test.

Child race and ethnicity were reported by parents at baseline. See eMethods in Supplement 1 for the reason race and ethnicity were reported as variables in this study.

Other race and ethnicity includes other single or multiple races reported, or declined to respond, no response, or unknown.

Religious affiliation was defined as endorsing any religious preference vs agnostic, atheist, or none.

Median household income level: used cannabis ($50 000 to $74 999), heard of but have not used cannabis ($75 000 to $99 999).

Group comparison conducted using Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Descriptive only, not assessed as a covariate in models.

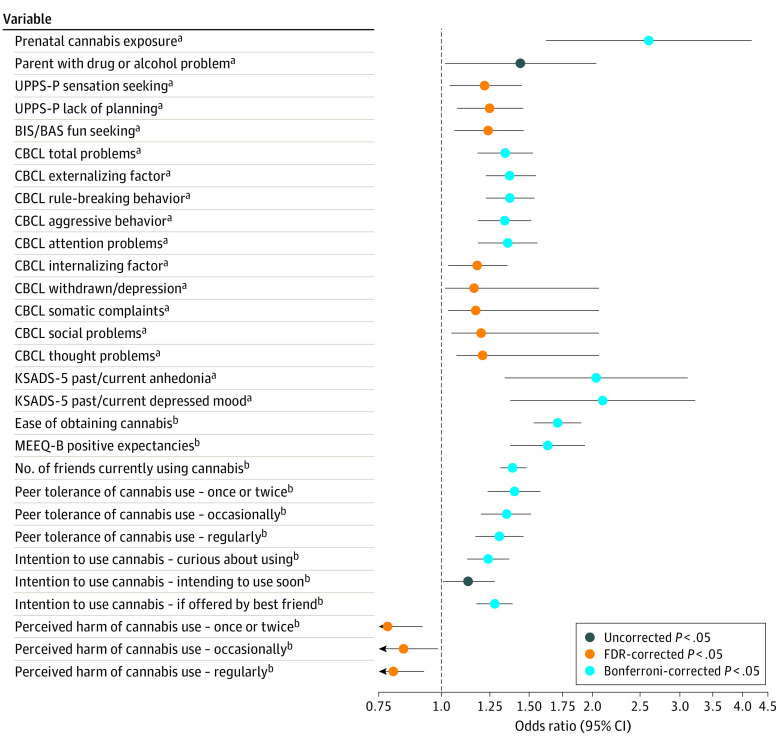

Figure. Variables Associated With Cannabis Initiation as Children Enter Early Adolescence.

Odds ratios and 95% CIs, presented on a log scale, are from mixed-effects logistic models with binary cannabis use initiation outcome variable (0 = have not used, 1 = have used). Random intercepts were specified based on data collection site. Fixed-effect covariates included baseline (1) child sex (0 = female, 1 = male), (2-5) self-reported child race and ethnicity (Asian, Black or African American, Hispanic or Latino, White), (6-8) parent marital status (married or cohabiting, widowed, divorced), (9-11) parent education level (less than high school, high school diploma or equivalent, undergraduate degree), (12-15) household income (<$25 000; $25 000 to $49 999; $50 000 to $74 999; $75 000 to $99 999), (16) parent age at baseline, (17) family membership (0 = not related to any other child in sample, 1 = shared family membership), and (18) twin status (0 = not a member of twin pair, 1 = member of twin pair). All variables plotted are significant at uncorrected P < .05 with additional significance thresholds presented for 5% false discovery rate (FDR) and Bonferroni multiple testing corrections. Nonsignificant variables are not shown. Supplement 1 has additional details regarding variables and analytic approach. BIS/BAS indicates Child Behavioral Inhibition & Behavioral Activation Scales; CBCL, Child Behavior Checklist; KSADS-5, Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia; MEEQ-B, Marijuana Effect Expectancy Questionnaire–Brief; UPPS-P, modified UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior Scale for Children.

aAssessed at baseline.

bAssessed at 1-year follow-up.

Results

Following false discovery rate correction, 29 of 46 variables were significantly associated with cannabis use initiation (Figure), 18 of which survived Bonferroni correction. As expected, initiation of alcohol and tobacco use by 3.5-year follow-up exhibited the greatest effect sizes (odds ratio [OR], 17.46; 95% CI, 11.10-27.47 and OR, 35.85; 95% CI, 23.21-55.37, respectively). Outside of these associations, prenatal cannabis exposure was associated with the largest risk for cannabis use initiation (OR, 2.60; 95% CI, 1.62-4.17); this association remained when additionally controlling for alcohol and tobacco use initiation, family or parent alcohol or drug problems, and prenatal alcohol and tobacco exposure (OR, 2.16; 95% CI, 1.17-3.97). Several cannabis-specific factors at 1-year follow-up (mean [SD] age, 10.92 [0.64] years), including ease of obtaining, positive expectancies, number of friends using, and greater peer tolerance, were associated with greater odds of early initiation of cannabis use. Greater externalizing symptomatology, depressed mood, and anhedonia at baseline were also significantly prospectively associated with cannabis use initiation (Figure).

Discussion

Prevalence of cannabis use initiation by early adolescence in the ABCD study (1.56%) closely parallels rates of cannabis initiation observed in nationally representative samples (eg, 1.87%1). Prenatal cannabis exposure was associated with a more than 2-fold increase in early onset of cannabis use, independent of prenatal exposure to or use of other substances or family history of drug or alcohol problems. Similar associations have been noted in later adolescence or adulthood,4 but our study suggests an association with early-onset use. In addition to replicating associations between externalizing behavior and early cannabis use,5 anhedonia and depressed mood at age 9 to 11 years were associated with future early-onset cannabis use, highlighting internalizing symptomatology as a risk factor for early initiation. Moreover, cannabis-related individual (eg, positive expectancies), social (eg, peer use/attitudes), and environmental (eg, ease of access) factors were associated with early onset use. Permissive social milieu in childhood and adolescence may represent a tractable target for prevention and intervention efforts.6 Notwithstanding limitations of the small sample of participants having used cannabis, our findings suggest greater caution in cannabis-related attitudes, access, and use during periods of vulnerability (eg, pregnancy), particularly for youth with other mental health liabilities.

eMethods

Data sharing statement.

References

- 1.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. HHS Publ No PEP19-5068 NSDUH Ser H-54. Published May 2019:51-58. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHNationalFindingsReport2018/NSDUHNationalFindingsReport2018.pdf

- 2.Connor JP, Stjepanović D, Le Foll B, Hoch E, Budney AJ, Hall WD. Cannabis use and cannabis use disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):16. doi: 10.1038/s41572-021-00247-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lisdahl KM, Sher KJ, Conway KP, et al. Adolescent brain cognitive development (ABCD) study: overview of substance use assessment methods. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2018;32:80-96. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2018.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sonon KE, Richardson GA, Cornelius JR, Kim KH, Day NL. Prenatal marijuana exposure predicts marijuana use in young adulthood. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2015;47:10-15. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2014.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.King SM, Iacono WG, McGue M. Childhood externalizing and internalizing psychopathology in the prediction of early substance use. Addiction. 2004;99(12):1548-1559. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00893.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turel O. Perceived ease of access and age attenuate the association between marijuana ad exposure and marijuana use in adolescents. Health Educ Behav. 2020;47(2):311-320. doi: 10.1177/1090198119894707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

Data sharing statement.