Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to understand the limited English proficiency patient experience with health care services in an urban setting in the United States.

Methods

Through a narrative analysis approach, 71 individuals who spoke either Spanish, Russian, Cantonese, Mandarin, or Korean shared their experiences through semi-structured interviews between 2016 and 2018. Analyses used monolingual and multilingual open coding approaches to generate themes.

Results

Six themes illustrated patient experiences and identified sources of structural inequities perpetuating language barriers at the point of care. An important thread throughout all interviews was the sense that the language barrier with clinicians posed a threat to their safety when receiving healthcare, citing an acute awareness of additional risk for harm they might experience. Participants also consistently identified factors they felt would improve their sense of security that were specific to clinician interactions. Differences in experiences were specific to culture and heritage.

Conclusions

The findings highlight the ongoing challenges spoken language barriers pose across multiple points of care in the United States' health care system.

Innovation

The multi-language nature of this study and its methodological insights are innovative as most studies have focused on clinicians or patient experiences in a single language.

Keywords: Limited English proficiency, Immigrant, Health equity, Hospital, Primary care, Home health services

Highlights

-

•

In contrast to previous studies, this study shows how people with language barriers who access health care services have a common experience with receiving services.

-

•

The data facilitated the generation of a patient-centered decision tree to facilitate meeting patient preferences for the implementation of language services.

-

•

This study tested a multilanguage analytic method to mitigate the risks posed by translation to the rigor of the results.

1. Introduction

In the United States (US), a person is described as having “limited English proficiency” (LEP) when they cannot safely communicate their needs in English or must rely on an interpreter to communicate (LEP.Gov - Limited English Proficiency (LEP): A Federal Interagency Website, 2019). When an LEP person engages with the healthcare system, a language barrier between themselves and their clinician may result when both do not speak the same language. Thus, by law, it is required that a person's language preference—meaning the language in which they prefer to communicate—be documented in the medical record so that interpreter services can be arranged to facilitate communication during a healthcare encounter [30].

A person's language preference is a social determinant of health, especially when it differs from the dominant language spoken in a country [1]. Research consistently demonstrates that in the United States (US) and countries serving multilingual populations, a language preference other than English reduces access to primary care and preventive screening services; increases the risk for hospital readmissions broadly and within 30-days; and leads to higher overall risk for adverse events among hospitalized individuals who do not speak English [2,[7], [8], [9],14,15,22,[31], [32], [33], [34]]. In the US, studies from the primary care setting dominate the literature and few have studied non-physician personnel [9]. A limited number of studies have examined the patient experience across multiple points of care or involved more than one language.

The necessity and importance for an enhanced understanding of the impact of language barriers on the patient attempting to access and use health services in the US is driven by the significant growth of the immigrant population in the country. Since 1990, the immigrant population in the US grew from approximately 8% of the population to nearly 14% before the pandemic in 2019 [29]. Healthcare organizations that previously had minimal to no experience serving immigrant populations, including those with language barriers, now often find themselves working with a rapidly growing community which has a diverse range of health care needs and may lack the resources or understanding of the extent to which language barriers affect the patient experience and health outcomes.

The purpose of this study was to explore five limited-English-proficient immigrant populations' experiences with US healthcare services through their stories of healthcare encounters to identify if there are common and distinct experiences based on language group. The findings will advance our knowledge of the nuances of the experiences that lead to different kinds of outcomes and how they contribute to health inequities in non-English speaking immigrant populations.

2. Methods

A narrative approach structured this qualitative study of LEP persons who live and access healthcare in an urban setting on the Northeast Coast of the United States (US). Narrative approaches seek to capture participant experiences through the stories they tell about them [16,24]. The method posits that people are natural storytellers, with the character and experiences of an individual in relation to their social world emerging through how they tell stories about their experiences [17]. Active reflexivity is built into the approach to ensure representation of the participants' experiences are as accurate as possible [4]. It is an ideal method or conducting cross-cultural research with a decolonizing approach, particularly when a language barrier is present between the researcher and the participant [13].

2.1. Study team

The team implementing the study was comprised of a principal investigator (PI) who is a bilingual nurse (Spanish) and health services researcher (AS); a project manager (PM) who was also bilingual (Spanish) and a home health care nurse (SM); a co-investigator who was also a health services researcher and bilingual (Mandarin) (CM); and a team of research assistants who spoke English and one of the study's target language. With an experienced, trilingual (Mandarin and Cantonese) research assistant managing the overall group (EL), research assistants were at a minimum bachelor's degree prepared, had demonstrated language fluency (e.g. reading, writing, speaking, and comprehension), and previous experience conducting translations. None of the research assistants had previous experience in healthcare, which meant they did not have the potential bias of a healthcare provider identity when conducting interviews. The partner agency—a large urban home health care agency with a research unit–provided an experienced research coordinator to facilitate training research assistants (MT).

2.2. Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of New York University [IRB-FY2018–1562] and the Visiting Nurse Service of New York [#796572–15], the study's partner agency. Informed consent was obtained from participants based on mode of data collection (e.g. telephone, in-person), occurred prior to the interview starting, and was either verbal or written. The informed consent process included a statement that participants consented to their de-identified quotes being used in publications and presentations.

2.3. Setting

Participants were recruited from an urban home health care agency whose clientele is linguistically diverse. Home health care services in the US occur through either a referral from a primary care physician or after a hospitalization or rehabilitation stay [18]. Selecting participants who had received home health care services would ensure that they had a high probability of having experienced multiple aspects of the health care system as part of their overall experiences.

2.4. Sample

Recruitment criteria for inclusion in the study included participants who received care from the partner agency at some point between 2016 and 2018. They also had to be adults over the age of 18 who spoke either Spanish, Russian, Mandarin, Cantonese, or Korean and confirmed they had immigrated to the US during the recruitment call. The targeted languages for study participation represented the largest language groups served by the agency, thus ensuring we had an adequate pool for recruitment. We limited our participants to those who had experienced a hospitalization and the need for home health care services in the last year because we wanted to make sure a recent hospitalization experience was part of the study.

Based on recommendations generated by coding and thematic saturation pattern analyses by Hennink et al. [10], the team theorized that recruiting a minimum of ten participants per language would generate sufficient coding saturation specific to each language's culture yet not allow for one language to dominate the code generation process. Collectively, the entire sample would then generate meaning and thematic saturation that would reflect both their common and distinct experiences [10].

2.5. Recruitment

Drawing from the client service records of the partner home health agency, the agency study coordinator (MT) selected participants through convenience sampling approaches who had indicated that their preferred language was one of the targeted languages of the study. Language concordant research assistants then called prospective participants via the listed telephone number to recruit them into the study. The study was explained to them and a cognitive screening was conducted to ensure the participants were eligible for the study. For participants who expressed interest in participating in the study, an appointment was made for interview based upon the availability of the participants. The research assistants made a total of 909 recruitment calls that were roughly evenly divided across all five targeted language groups. Table 1 provides the breakdown of the recruitment calls.

Table 1.

Recruitment call record.

| Call Result | # |

|---|---|

| Left message, no return call | 336 |

| Left message, returned call, declined participation | 95 |

| No answer | 254 |

| Call answered, declined participation | 153 |

| Call answered, agreed to participate | 71 |

| TOTAL | 909 |

2.6. Data collection

Prior to data collection, the interview guide was initially developed in English with questions derived based on the literature. Translations in each target language were completed by the research assistants. An independent, bilingual researcher verified the translations as a quality check. The English version of the interview guide is provided in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Interview guide (English).

Once participation was confirmed and scheduled, on the interview day the research assistant obtained informed consent and conducted the interview in the participant's preferred language in their home or via telephone. If family members or caregivers were present and wished to participate, RAs were instructed to include them. All interviews were digitally recorded by the research assistants and then uploaded to a secure storage system after the interview. Research assistants also recorded reflective notes immediately following the completion of each interview. The latter were also included in data analysis processes and useful for understanding the context of the interview.

2.7. Data analysis

While no theoretical framework structured this study, two theoretical assumptions were made during data analysis. First, drawing from the PI and PM's experiences working with LEP patients, the team posited that the common identifier of preferring a language other than English during healthcare encounters would lead to commonalities when shaping the experience with health care as immigrant patients, regardless of language spoken. The second, building Lincoln and González y González's [13] decolonizing approaches to qualitative research, was that the design of the study had to ensure that each participant's language had a sub-sample size that would be large enough to simultaneously generate both a common experience yet capture differences associated with culture and migration experience; thereby avoiding one language associated experience from dominating the other. Since most studies of immigrants are monolingual, designing and implementing a multilanguage qualitative study represented a novel methodological advance.

After interviews were transcribed and translated, the PI and PM analyzed the interviews using narrative analysis techniques. A common codebook was developed via consensus after initial analyses. Once the codebook was harmonized, the PI analyzed interviews by language group (e.g. coding all Cantonese, all Spanish, etc.). Simultaneously, the PM analyzed translated interviews by selecting interviews in random order (e.g. 1 Cantonese, 1 Spanish, 1 Russian, 1 Korean, etc.). For all phases of the analysis, we tracked when both coding and thematic saturation occurred, as recommended by Hennink et al. [10].

Finally, we also tested a bilingual coding approach (previously used by the PI in two Spanish language focused studies [27,28]) with the Spanish and Mandarin language interviews (n = 33). We sought to determine if, when working with a multilingual team, could produce rigorous analyses and reduce translation burden. Spanish language interviews were coded in English by the PI and PM independently and the Mandarin language interviews were also coded in English by CM and EL following the same approach. Each person verified the other's coding and interpretations as a confirmability and dependability check to ensure the process did not lose rigor and the overall analysis would produce trustworthy results. Final theme generation occurred through consensus-based approaches with all persons involved with coding [6].

3. Results

A total of 71 individuals participated in the study with 18 Spanish speakers from four countries, 14 Russian speakers from three countries, 15 Mandarin speakers (all from China), 12 Cantonese speakers (all from China), and 12 Korean speakers. All languages had roughly an even split between male and female participants except Korean where we were only able to recruit female participants. Eight interviews had family members participate in some way, which added additional insights into the limited English proficiency patient experience. All participants had immigrated to the US but were now citizens, with the majority of them insured by Medicare. Participant ages ranged from 55 to 87.

Interviews lasted anywhere from 20 to 100 minutes. Upon review of the transcripts, we found that telephone vs. in-person interviews had no substantial differences in interview quality nor time length. There were notable trends, however, by language group in terms of interview length. Spanish speakers had the longest interviews whilst Russian speakers had the shortest. There were no specific trends among the Asian language speakers in terms of interview length.

Confirming our theoretical assumption, recruiting ten participants per language did ensure that we had sufficient data that was specific to the participant's culture so that we could discern culturally distinct experiences. We found that coding saturation was achieved at two distinct points in the analysis. For single language analysis, coding saturation occurred after 8 interviews with the first language with each subsequent language group adding between four and ten codes to the book. For the multilanguage coding approach, overall coding saturation occurred after 14 interviews. Themes began to emerge after five interviews in both approaches and thematic saturation occurred after coding 29 out of 71 interviews in the single language approach and 26 out of 71 interviews with the multi-language approach.

Six themes emerged from the analysis that threaded across all languages. They are named and defined as follows:

-

•

“It's OK, but not really.” – Describes how everything in the person's experience dealing with the health system becomes about managing the language barrier. It also increased feelings of loneliness resulting from the patient experience.

-

•

“Knowing there is risk for harm” – Participants lived with the assumption that they were at greater risk for harm as the result of being with language barriers during a healthcare encounter.

-

•

“The Essentialness of Family” – Family became a necessity for bridging the language barrier, even when interpreters were present.

-

•

“A language concordant environment changes the experience, reduces inequities.” – Participants uniformly agreed that when clinicians spoke their language, they perceived the patient experience as no different from English speakers.

-

•

“Respectful interactions” – Participants defined what they perceived as respectful and disrespectful interactions with healthcare team members during healthcare encounters.

-

•

“Patient-Clinician relationship quality” – Beyond respectful interactions, clearly defined patient views of quality healthcare encounters emerged from the analysis.

Themes and their associated categories are discussed in the succeeding paragraphs.

3.1. Theme 1: “It's OK, but not really.”

Participants described language barriers as ever-present in their experiences with hospitalization, home health care services, and other forms of health care services. Participants described an acquiescence to the system's inconsistent ability to provide language-concordant care, but at the same time a desire to plan ahead and attempt to optimize an encounter. Across the languages, participants also described a sense of loneliness that directly related to the language barrier. Data further coalesced into other categories related to this theme.

3.1.1. The patient needing to go above and beyond to communicate

Noting the acceptance of suboptimal care, participants often shared strategies they employed to try to improve communication. Commonly, participants described the use of non-verbal communication such as gestures to communicate in moments where waiting for an interpreter would be frustrating. While most participants described body language gesturing or writing down communications to be helpful, others described more difficulty.

Planning ahead and using creativity in situations patients considered to be important were strategies commonly used. One Russian-speaking patient described a desire to understand health encounters entirely and using internet searches at home to “find out about [his doctor's] point of view and everything that was about that subject in general.” A Cantonese speaking patient described using a different strategy when interacting with staff around learning about a serious health condition: “I really had to cooperate with them, have to think of different ways, think about who I should contact to help me.”

In addition, participants often described needing to apply whatever limited English skills they had when other strategies were unsuccessful and interpretation was unavailable. Participants who could understand English often felt like their ability to understand it was beneficial, but to not speak it still left them vulnerable. When describing the desire to understand specific aspects of a conversation with providers, a Korean speaker said, “I don't understand, I understand English, Korean both, but they didn't give me explanation…I'm just guessing, figuring out.”

Another Korean speaking participant described low English proficiency around healthcare as a very different circumstance than in routine life stating, “so in our everyday life, even if I understand 50% of the conversation, I can express myself, but this is something that I really have to know about, my disease process... when there are Koreans who can help me out when there is a language barrier, I am really thankful.” There was a consistent worry that miscommunication could lead to improper diagnosis or treatment, with many participants citing past medical errors they or loved ones experienced personally.

3.1.2. Isolation in the patient experience

Cultural and linguistic isolation was a common theme across the narratives. Participants described loneliness due to lack of interpreters and culturally-congruent staff. Some participants expressed frustration, while others, like this Cantonese-speaker, expressed it as an acceptance of life as an immigrant:

“Like that's how I feel. Like if we are both Chinese isn't that more cordial? Like just saying. But if they really don't have it then you can't really do anything about it. You don't have a choice for this because you are in other people's country, right? You cannot expect everyone to be Chinese, right?”

Similar to this participant, several other participants expressed a sense of shame for having low English proficiency, despite the length of time they had lived in the country. One Russian-speaking participant shared his goal to be understood and to understand: “I am trying to go where can express myself on my own and where I can be understood on my own, but it takes time.” That sense contributed to feelings of isolation and a lack of connection with clinicians.

3.2. Theme 2: Knowing there is risk for harm

Similar to participants' awareness and acceptance of care which felt suboptimal, participants were similarly conscious of the additional risks they encountered due to language barriers. The discussions around these risks varied, but a similar expression of worry was found across the languages.

3.2.1. Accepting care that feels suboptimal

Participants described multiple aspects of encounters with hospital or home health care staff which they knew to be suboptimal. There was an overall awareness in participant narratives that acknowledged that the care they received when a language barrier was present was not the same as care a patient with English proficiency receives. One Cantonese-speaking participant remarked that even with interpreters present at hospitals, “[they] don't follow you around all day,” and that many important moments with staff, such as identifying specific details about pain, lack clear communication.

Across the languages, participants accepted that in language-discordant conversations, things were lost in translation. Participants expressed frustration that, even with an interpreter, care encounters felt slower and inflexible, and subtleties in the conversation were lost. Despite this frustration, participants described an overall sentiment of acceptance of their circumstances, to the point that poor translations noted by participants or their family members were perceived as a normal part of the experience. A Spanish-speaking participant summarized her experiences working with an English-speaking home health care provider stating, “it didn't affect me too much, since I am used to working with this type of person.” Importantly, this phenomenon was present in narratives about care in all settings, including home health care.

Concerns about safety and risk were similarly described in narratives around surgery, discharge instructions, or emergency situations. Multiple narratives portrayed participants as fearful of "pivotal moments: in a healthcare encounter where the language barrier would leave them vulnerable and gesturing or pointing would not keep them safe. A Cantonese-speaker summarized the possibility of a “detrimental moment…quite dangerous” while a Spanish speaker recognized that “many have died more from medical errors than from those same diseases.” Even when providers shared good news, participants felt that interpretation was significant to truly understand their health in detail.

3.2.2. What am I consenting to?

Participants frequently mentioned the processes of signing consent forms and giving informed consent as points where the language barrier was apparent and distressing. In some instances, participants described processes where hospitals or providers took extra time to explain a procedure in detail, even speaking with participants days before a procedure. In other narratives, however, participants shared stories of rushed, uninterpreted consenting processes, where they acquiesced to the needs of the staff in order to move quickly and “sign everything fast-fast before the surgery while they processed the papers.” When asked about how it feels to not completely understand what you are signing and agreeing to, one Russian speaker laughed and said, “well, with my eyes closed, and what can I feel? Discomfort, of course.”

3.2.3. Fear and anxiety

Across the languages, participants expressed fears and anxieties about medical errors and risks for harm, both recounting past experiences and worrying about future risks. Unfamiliarity with medical terminology was frequently listed as a primary cause of anxiety, even for those with some English proficiency or assistance with interpretation.

Then I stayed at [X Hospital] Everyone [working] there were foreigners, I was nervous. Sigh, I was thinking my daughters know English, but they weren't there at the time. I didn't know what to do, I was nervous, quite nervous, I don't know what they will be asking me, or what I need, right? So I was very scared. (Mandarin)

One Spanish-speaking participant described being the victim of a medical error, and while not placing blame on the healthcare providers or hospital, expressed concern over a future error. Another Spanish-speaking participant described an experience where urgent decision-making was slowed while staff looked for interpreters. Despite participants' awareness of their increased risks, many felt powerless as patients with LEP, and accepted the need to be flexible and creative to minimize whatever risks possible.

3.3. Theme 3: The essentialness of family

English proficient family members were seen as a vital component to bridging the language barrier, not just in interactions with the healthcare system, but in fostering a sense of safety and understanding with regards to one's health. Participants presented a different story when their family members also had LEP but were the only support persons available. Finally, participants described the financial and physical sacrifice family members made to be available to assist ill or aging relatives with health or language barrier issues.

3.3.1. Experiences based on English Proficiency

Adult children with English proficiency were described as essential in their roles as interpreters, especially those who had experience working in the healthcare sector. In the many events where professional interpreters are unavailable, participants felt that family members were able to fill the gaps and increase their sense of safety. At the same time, family members were not just translators and interpreters, but also intimately involved in their loved one's care.

Participants' descriptions of the helpfulness of family shifted when discussing family members who also had low English proficiency and who were “newer” immigrants. While family support was welcomed, those family members with limited English proficiency were unable to serve as interpreters and were often just as isolated as the patient. Participants described the experience of being a newer immigrant in the US as very different in terms of family helping to bridge language barriers. One Spanish-speaking participant described his family's need to “defend ourselves with the little English we know.”

3.3.2. Consequences of family being there

While participants expressed gratitude for family members who are able to be present throughout a hospitalization or rehabilitation, they also noted the toll this commitment takes. For many of these older adults, children often provide care and assist with case management. The added role of interpreter further complicates family member involvement. One Cantonese-speaking participant described his/her son's commitment as “toilsome for him…taking care of me day and night” when he works night shifts. Similarly, a Spanish-speaking participant described needing his daughters at every visit due to his uncertainty in his ability to be understood, even in Spanish. This commitment forced either flexibility in his daughters' work schedules or in the participant's appointment schedule, and while the participant knew this toll, he chose to always include his daughters.

3.4. Theme 4: a language concordant environment changes the experience, reduces inequities

Participants perceived some language-concordant interactions with healthcare providers as equivalent to the care that English-proficient patients receive. The details of their perceived high-quality language-concordant interactions varied and included interpreters on staff, telephone interpretation, and family members serving as ad hoc interpreters. Regardless of these differences, participants desired consistent, high-quality, language-concordant environments for their care. They also uniformly expressed a primary preference for a clinician who spoke their language.

3.4.1. Patient-clinician language concordance

Participants consistently described language-concordance with a clinician as their most preferred method of communicating and use of a competent, in-person interpreter or a family member as their next preferred methods. Speaking directly to a clinician allowed for a consistent conversational flow which participants preferred to the disjointed conversation style with interpreters. Similarly, a Korean-speaker shared the strategy of finding a language-concordant primary care provider to help address confusion that arises with specialists: “S/he leads me…tells me where to go, where to go.”

While in the hospital, participants expressed they experienced isolation and anxiety. Language concordant interactions with clinicians decreased these feelings. While major encounters with an attending physician were often translated, routine conversations with other staff (e.g. nurses, nursing assistants) were often uninterpreted, leaving participants alone to communicate by whatever means possible. For example:

She asked me if I need any help. I said I need to ‘pee pee.’ I don't speak English. I don't know how to tell them (the doctors, nurse…). Really, I was very nervous at that moment, because I don't know English, right? But then I found this person, she told me, don't worry, I work for this hospital, I service people like you. I said, oh, I didn't see any Chinese people here. (Female Mandarin speaker)

In-person interpreters, though not always the first preference of participants, were also a source of safety and protection for participants when they perceived the interpretation quality to be high. High quality interpretation was defined as timely, accurate, available in a participant's dialect, available for oral communication, and included written documents in their language.

3.4.2. Desired workforce attributes

While participants had positive language concordant experiences in some instances, others expressed frustration with the lack of linguistic and cultural diversity in the healthcare workforce, including both hospital and home health care staff. Spanish-speaking participants encouraged healthcare workers to study and learn Spanish while Chinese and Korean speakers wished that health systems would hire bilingual workers with proficiency in both languages. Russian-speakers expressed the least difficulty in finding a bilingual workforce, but noted that in order to seek out language concordance, they chose to utilize specific hospitals or clinicians where they knew they could consistently find people with Russian language proficiency or, in some cases, their first languages (e.g. Ukrainian, Tajik, Georgian) as Russian was often their second one.

In the home health care context, participants felt most vulnerable and aggravated by language barriers with home health care staff, where interpretation was not offered or available in many cases. One Cantonese-speaking participant described needing to pick up and show objects to the home health attendant (HHA) when asking for help as a “big problem” when recuperating from a hospitalization. A Korean-speaking participant desired a live interpreter for home-care encounters and was told, “there is no such home health care,” while a Spanish-speaker said of home health care service agencies, “if we are Hispanic, send us Hispanics.”

Desired cultural diversity included an acknowledgement of the within-group differences of a culture. For example, Spanish-speaking participants desired providers who understood their country of origin's specific culture. Taishanese participants often found they could not find an interpreter or staff member who spoke the Taishanese dialect. One Mandarin-speaking participant had a positive experience with language discordant staff who were able to anticipate the need for an interpreter and noted the participant's difficulty understanding somewhere in the chart. That resulted in succeeding clinicians being more sensitive to their communication barrier.

3.5. Theme 5: Rrespectful interactions

Participants described encounters with providers which they considered to be respectful in some cases and disrespectful in others. Respectful encounters were described as authentic, kind, and attentive. By contrast, disrespectful encounters were portrayed as dehumanizing and isolating. Most of these exemplars came from hospital-based experiences, but could apply to any care delivery setting.

3.5.1. Respectful

Kindness was considered a universally understood and communicated sentiment across a language barrier. Even when sharing narratives around issues where language discordance threatened patient safety or health-specific knowledge, providers who practiced with kindness were did not go unnoticed. This sentiment is best summarized in one Korean-speaking participants words describing her experience with home health care staff: “they were always smiling and kind to me that I could feel their heart. So even though I cannot understand them 100%, we have a heart-to-heart communication.”

In addition to kindness, participants felt that interactions where providers and even entire hospitals or health agencies showed commitment and effort were respectful. Respect was defined as promptly answering call lights, encouraging and supporting participants to use interpreters, and in spite of a busy workload, showing kindness. One Spanish-speaking participant expressed appreciation at the respect shown by the nursing staff who, though always busy, answered the call light quickly and cheerfully and always had the interpreter phone ready.

3.5.2. Disrespectful

In many narratives of disrespectful encounters, participants described feeling isolated, invisible, or dehumanized by providers' actions, inactions, or words. One Cantonese-speaking participant described a change in provider behavior from respectful to disrespectful when family members were no longer present. A Mandarin-speaking person wondered if, “Chinese people are easier to bully” based on their experiences with staff. A Russian-speaking participant described an “emotional explosion” when basic communication needs were ignored, and felt that providing respectful services in a person's preferred language “will help solve the most elementary problem.”

Participants expressed further frustration at being ignored or isolated by staff in any healthcare context. One Cantonese-speaking participant described multiple failed attempts to ask staff to use the bathroom in a clinic waiting room, only to urinate themself and subsequently, felt “ignored and humiliated.” Another Cantonese speaker remarked about clinic staff who assumed he did not understand English and pretended they could not hear or understand him. A Spanish-speaking participant wanted healthcare staff to provide care to older adults with the same care, attentiveness and respect that they would treat a young child—because they had yet to have that experience, Finally, a Cantonese-speaker shared a story of being left alone in the bathroom by a home-care attendant for an extended period of time and felt “duped” by the lack of attention as that was not what they had understood would happen when receiving home health care services.

3.6. Theme 6: Patient-provider relationship quality

Beyond respectful interactions, participants described what aspects of their relationships with providers they considered to be most important and of high quality. High- and low-quality relationships and encounters were described for all levels of care, including home health attendants and home health care licensed professionals, nursing staff, allied health professionals, and physicians.

3.6.1. Competence over everything else

While participants preferred language concordant, respectful encounters, many described “competence” as their clinician's most important quality. This was especially true when participants spoke of receiving care from a specialist. A Russian-speaking participant shared: “When it comes to my major problem, I prefer the professionals who are qualified in this problem” while a Korean speaker explained the need for “a doctor or nurse with excellent clinical skills even if there is a communication barrier.”

3.6.2. Trust and caring

In addition to competence, having trust in a clinician was an important aspect of a relationship. Trust went beyond clinical skills and was an intangible, but easily understood (despite the language barrier) aspect of a relationship.

But for me, what is more important for me is that doctors absolutely need to provide trust to patients, and that I think I need to trust them. If you do that, more than the clinical skills and [language barriers], if the doctors treat their patients whole-heartedly, then there are cases when the “sickness of the heart” is healed more. Better than any practices or medications. So for me, my main focus is on the relationship between the doctor and patient, and how much the doctor puts his heart for the patients, rather than the clinical skills. (Korean)

One Cantonese-speaking participant described the safety s/he felt when visited daily by a psychiatrist while in the hospital, and another felt “very lucky to find [his/her] doctor” who was “…a very good doctor [and] conscientious.”

Home health aides, in particular, were expected to be trustworthy and to show sincere effort and care in their work. Participants expressed frustration in home health aides who appeared to be insincere, lazy, or inattentive, or those who “don't move, just sit and get paid (Korean).” At the same time, some participants enjoyed socializing with HHAs, even with a language or cultural barrier present. One Cantonese-speaking participant described his/her positives experiences with her home health aides, “Communication problem yes. Yes, there is little problem, but she's doing her best and she has warm heart. It's good enough.”

4. Discussion & conclusion

4.1. Discussion

The findings from this study illustrate how patients who have language barriers experience US healthcare across multiple access points. It reflects a common experience associated with having limited communication ability in English when interacting with healthcare providers and systems, regardless of diagnosis. The participants' reflections reinforce the findings of multiple studies about the sources of inequitable health outcomes for persons with language barriers seeking healthcare services in the US as well as other countries [3,5,7,8,14,19,21,23,31,33]. Importantly, it also captures how these individuals are aware of the risks associated with having a language barrier and the added layer of stress it contributes to the experience of acute illness and chronic illness management. The common findings around patient experience further underscore its importance to increase the production of research that addresses immigrant health disparities across multiple language groups.

As we consider the implications of the findings, several opportunities emerge. Since the present patient satisfaction measures in the US largely fail to account for heritage, culture, and language [5], this study helps to illustrate why common patient experience measures are needed for this population. The consistency of the descriptions about both provider and system performance expectations, regardless of the point of care, suggests that common measures are possible, yet would require standardized data capture practices would help reduce inequities in patient experiences.

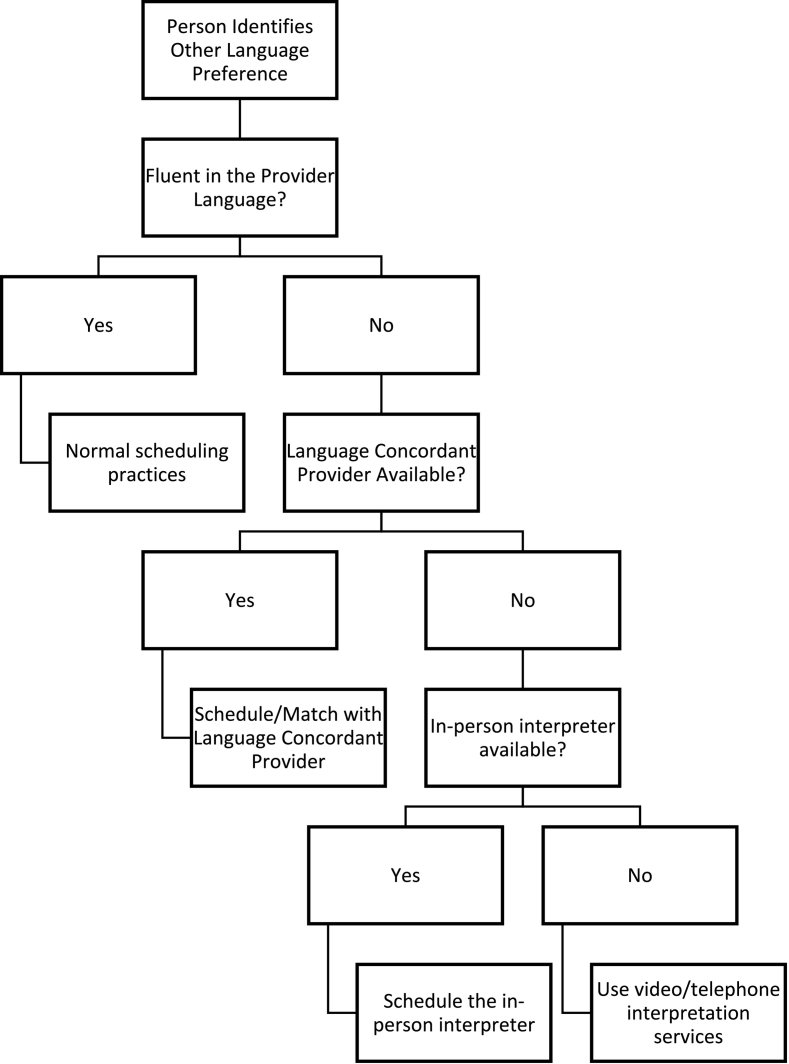

In Fig. 2 the findings are synthesized into a decision tree of how participants expressed their preferences for interpretation modality in the results which may lead to improved patient experience and could be further tested through research. Family members as an interpreting option are not included since many countries are moving toward legal regulations that discourage family members serving as interpreters unless it is an emergency situation. The participants' universal preference for having a provider who can communicate in their language underscores the importance of this aspect of the limited English proficiency patient experience and is also supported by a recent systematic review by Hsueh et al. [11]. This finding emphasizes the importance of health workforce investment strategies that encourage recruitment of people who speak other languages into all healthcare roles—including healthcare interpreters.

Fig. 2.

A patient centered decision tree for language services use.

At the same time, capturing provider language proficiency in other languages is another important step for improving the patient experience. There is no state or national level data in the US about how many healthcare workers speak other languages safely enough to communicate with patients [20]. Without that data, how to prioritize investments in language concordant personnel according to the local market demand will be nearly impossible. Healthcare organizations have only recently begun to track language skills of clinicians due to the new requirements of Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act that were set into policy in July of 2016 [30], so research may be limited to the organizational level in many cases.

With language translation as part of this study, that is the first limitation as there is always a risk for some conceptual drift in cross-language qualitative research [12,25,26]. The novelty of the multi-language approach may also pose some methodological threats, but the integration of reflexive processes into the analytic approach should have mitigated these risks. Other limitations are those commonly associated with qualitative studies more generally. The team was also unable to perform member-checking with participants as many individuals were home-bound and without access to high-speed internet service.

4.2. Innovations

The innovations in this study center on the methods. First, the multilanguage design of this study is innovative as most studies of limited English proficiency patient experiences focus only on a single language group. It illustrates the importance of capturing common experiences associated with language and distinct experiences associated with culture, as well as research studies involving more than one language. This study highlights how it is possible to do so both logistically and methodologically.

Our sampling approach of recruiting a minimum of 10 persons per language group was also an important methodological innovation to ensure we could capture common and distinct experiences associated with language and culture. Similar to Hennink et al. [10] observations of coding saturation being achieved after nine interviews, we found similar patterns when analyzing our data. Further, the approach of comparing coding by all languages vs. randomized languages was another methodological innovation to minimize a cultural bias in code development during the analysis process. The randomized coding process proved better at generating codes reflective of all patient experiences. The use of software, nonetheless, still enabled the team to look for language specific trends in coding and discern for differences between the patient groups. For future multilanguage qualitative research studies, we would recommend a randomized coding approach. Replication of the approach will help to further refine the method as well.

Finally, we observed no differences in single language coding results vs. multi-language coding results. The codebook harmonization process helped to ensure that regardless of the language of coding, there was a common conceptual definition using language that produced an accurate semantic, technical, and content representation in the translation. Researchers seeking to conduct multilanguage studies in the future should consider integrating this step in their analysis process if their team has members who are fluent in the study's languages. Otherwise, standard coding practices of translated interviews in the language of the researcher is the best practice.

5. Conclusions

This study helped identify the common and distinct aspects of the LEP patient experience in an urban US healthcare system. Findings revealed the sources of inequities from the patient perspective and identify opportunities where all points of health care access can improve the quality of the patient experience.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests.

Allison Squires reports financial support was provided by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R01#HS023593), United States of America. Dr. Squires is also an Associate Editor for the Elsevier Journal International Journal of Nursing Studies.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of study team members to this work: Gavin Arneson (NYU), Alena Golodets (NYU), Yunji Kim (NYU), Nicole Onorato (VNSNY), Melissa Uloa (NYU), and Yiqing Yuan (NYU).

Contributor Information

Allison Squires, Email: aps6@nyu.edu.

Lauren Gerchow, Email: lmg490@nyu.edu.

Chenjuan Ma, Email: cm4215@nyu.edu.

Eva Liang, Email: eva.liang@nyu.edu.

Melissa Trachtenberg, Email: trachm01@nyu.edu.

Sarah Miner, Email: sminer@sjfc.edu.

References

- 1.Acevedo-Garcia D., Sanchez-Vaznaugh E.V., Viruell-Fuentes E.A., Almeida J. Integrating social epidemiology into immigrant health research: a cross-national framework. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(12):2060–2068. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson L.M., Scrimshaw S.C., Fullilove M.T., Fielding J.E., Normand J. Culturally competent healthcare systems: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24:68–79. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00657-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauer A.M., Alegría M. Impact of patient language proficiency and interpreter service use on the quality of psychiatric care: a systematic review. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(8):765–773. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.8.765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bishop E.C., Shepherd M.L. Ethical reflections: examining reflexivity through an ethical paradigm. Qual Health Res. 2011;21(9):1283–1294. doi: 10.1177/1049732311405800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boylen S., Cherian S., Gill F.J., Leslie G.D., Wilson S. Impact of professional interpreters on outcomes for hospitalized children from migrant and refugee families with limited English proficiency: a systematic review. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18(7):1360–1388. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cascio M.A., Lee E., Vaudrin N., Freedman D.A. A team-based approach to open coding: considerations for creating Intercoder consensus. Field Methods. 2019;31:116–130. doi: 10.1177/1525822X19838237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark J.R., Shlobin N.A., Batra A., Liotta E.M. The relationship between limited English proficiency and outcomes in stroke prevention, management, and rehabilitation: a systematic review. Front Neurol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.790553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eneriz-Wiemer M., Sanders L.M., Barr D.A., Mendoza F.S. Academic Pediatrics. vol. 14. Elsevier Inc.; 2014. Parental limited english proficiency and health outcomes for children with special health care needs: A systematic review; pp. 128–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerchow L., Burka L.R., Miner S., Squires A. Language barriers between nurses and patients: a scoping review. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104(3):534–553. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hennink M.M., Kaiser B.N., Marconi V.C. Code saturation versus meaning saturation: how many interviews are enough? Qual Health Res. 2017;27:591–608. doi: 10.1177/1049732316665344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsueh L., Hirsh A.T., Maupomé G., Stewart J.C. Patient-provider language concordance and health outcomes: a systematic review, evidence map, and research agenda. Med Care Res Rev: MCRR. 2021;78:3–23. doi: 10.1177/1077558719860708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Im E.-O., Lee S.J., Hu Y., Cheng C.-Y., Iikura A., Inohara A., et al. The use of multiple languages in a technology-based intervention study: a discussion paper. Appl Nurs Res: ANR. 2017;38:147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2017.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lincoln Y.S., González y González E.M. The search for emerging decolonizing methodologies in qualitative research. Qualitat Inquir: QI. 2008;14(5):784–805. doi: 10.1177/1077800408318304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lommel L.L., Chen J.L. The relationship between self-rated health and acculturation in Hispanic and Asian adult immigrants: a systematic review. J Immig Minorit Health / Cent Minorit Pub Health. 2016;18:468–478. doi: 10.1007/s10903-015-0208-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luan-Erfe B.M., Erfe J.M., DeCaria B., Okocha O. Limited English proficiency and perioperative patient-centered outcomes: a systematic review. Anesth Analg. 2022 doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000006159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mishler E.G. Models of narrative analysis: a typology. J Narrat Life History. 1995;5:87–123. doi: 10.1075/JNLH.5.2.01MOD. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray M. Connecting narrative and social representation theory in health research. Soc Sci Inform Sur Les Sci Soc. 2002;41:653–673. doi: 10.1177/0539018402041004008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Narayan M.C., Scafide K.N. Systematic review of racial/ethnic outcome disparities in home health care. J Transcult Nurs: Off J Transcult Nurs Soc / Transcult Nurs Soc. 2017;28(6):598–607. doi: 10.1177/1043659617700710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Njeru J.W., Wieland M.L., Kwete G., Tan E.M., Breitkopf C.R., Agunwamba A.A., et al. Diabetes mellitus management among patients with limited English proficiency: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(4):524–532. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4237-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nkimbeng M., Fashaw-Walters S. Health Affairs Forefront; 2022. To advance health equity for dual-eligible beneficiaries, we need culturally appropriate services. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shamsi H.A., Almutairi A.G., Mashrafi S.A., Kalbani T.A. Implications of language barriers for healthcare: a systematic review. Oman Med J. 2020;35(2) doi: 10.5001/omj.2020.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siddique S.M., Tipton K., Leas B., Greysen S.R., Mull N.K., Lane-Fall M., et al. Interventions to reduce hospital length of stay in high-risk populations: a systematic review. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.25846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silva M.D., Adelman R.D., Singh V., Gupta R., Moxley J., Sobota R.M., et al. Healthcare provider perspectives regarding use of medical interpreters during end-of-life conversations with limited English proficient patients. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2021;39(2):220–227. doi: 10.1177/10499091211015916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sools A. Narrative health research: exploring big and small stories as analytical tools. Health. 2013;17(1):93–110. doi: 10.1177/1363459312447259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Squires A. Language barriers and qualitative nursing research: methodological considerations. Int Nurs Rev. 2008;55(3):265–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2008.00652.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Squires A. Methodological challenges in cross-language qualitative research: a research review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(2):277–287. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Squires A., Juárez A. A qualitative study of the work environments of Mexican nurses. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(7):793–802. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Squires A., O’Brien M.J. Becoming a Promotora. Hispan J Behav Sci. 2012;34(3):457–473. doi: 10.1177/0739986312445567. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Squires A., Thompson R., Sadarangani T., Amburg P., Sliwinski K., Curtis C., et al. International migration and its influence on health. Res Nurs Health. 2022;45(5):503–511. doi: 10.1002/nur.22262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Squires A., Youdelman M. Section 1557 of the affordable care act: strengthening language access rights for patients with limited English proficiency. J Nurs Regul. 2019;10(1):65–67. doi: 10.1016/S2155-8256(19)30085-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taira B.R., Kim K., Mody N. Hospital and health system–level interventions to improve care for limited english proficiency patients: A systematic review. Joint Commiss J Qualit Patient Safety / Joint Commiss Res. 2019;45:446–458. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2019.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vakil K., Desse T.A., Manias E., Alzubaidi H., Rasmussen B., Holton S., et al. Patient-centered care experiences of first-generation, south Asian migrants with chronic diseases living in high-income, Western countries: systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2023;17:281–298. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S391340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woods A.P., Alonso A., Duraiswamy S., Ceraolo C., Feeney T., Gunn C.M., et al. Limited English proficiency and clinical outcomes after hospital-based Care in English-Speaking Countries: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37:2050–2061. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-07348-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zeidan A.J., Smith M., Leff R., Cordone A., Moran T.P., Brackett A., et al. Limited English proficiency as a barrier to inclusion in emergency medicine-based clinical stroke research. J Immig Minorit Health / Cent Minorit Pub Health. 2022;25(1):181–189. doi: 10.1007/s10903-022-01368-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]