Abstract

Objective

Communication around a palliative approach to dementia care often is problematic or occurs infrequently in nursing homes (NH). Question prompt lists (QPLs), are evidence-based lists designed to improve communication by facilitating discussions within a specific population. This study aimed to develop a QPL concerning the progression and palliative care needs of residents living with dementia.

Methods

A mixed-methods design in 2 phases. In phase 1, potential questions for inclusion in the QPL were identified using interviews with NH care providers, palliative care clinicians and family caregivers. An international group of experts reviewed the QPL. In phase 2, NH care providers and family caregivers reviewed the QPL assessing the clarity, sensitivity, importance, and relevance of each item.

Results

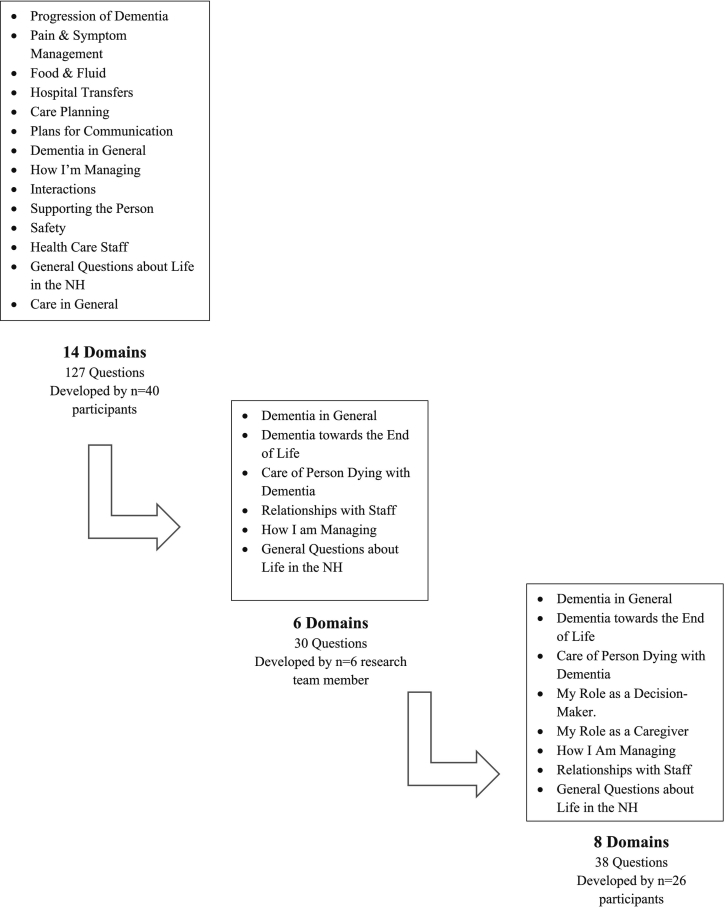

From 127 initial questions, 30 questions were included in the first draft of the QPL. After review by experts, including family caregivers, the QPL was finalized with 38 questions covering eight content areas.

Conclusion

Our study has developed a QPL for persons living with dementia in NHs and their caregivers to initiate conversations to clarify questions they may have regarding the progression of dementia, end of life care, and the NH environment. Further work is needed to evaluate its effectiveness and determine optimal use in clinical practice.

Innovation

This unique QPL is anticipated to facilitate discussions around dementia care, including self-care for family caregivers.

Keywords: Question prompt list, dementia care, nursing homes, palliative care

Highlights

-

•

A QPL has been developed using experts, including family caregivers.

-

•

The QPL is tailored to the needs of residents with dementia and their caregivers.

-

•

The conversational tone of the QPL builds on a relationship approach to care.

1. Introduction

As Western countries continue to experience a rise in the numbers of individuals diagnosed, living with, and dying from dementia, nursing homes (NH) have become an increasingly important site of care to those for whom living independently in the community is no longer viable. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, 20–48% of all deaths occurred in NH [1,2]. In NH, 80–90% of all residents have some form of cognitive impairment; therefore, being attuned to the needs of persons dying with dementia is essential [[3], [4], [5]]. One of the hallmarks identified as critical to ensuring excellent care near the end of life is communication [6]. However, one of the challenges identified in the literature is that communication between health care providers (HCPs), residents, and family caregivers is often problematic or occurs infrequently [7]. This communication gap may arise due to two main issues. First, family caregivers, who assume a significant decisional role in caring for persons with dementia, often perceive that HCPs do not have the time to spend with them, feel their concerns and suggestions are often ignored, and that they are passive or have difficulty obtaining information regarding the care of their family member [[8], [9], [10], [11], [12]]. Though they often have questions about death and dying as their relative's illness progresses, research suggests that not knowing what questions to ask about the illness trajectory and the changes that happen near the end of life, worries about being perceived as ignorant, and not wanting to interrupt staff pose significant barriers to families talking with HCPs [13,14]. Moreover, when they do engage HCPs in conversation about these issues, family caregivers feel they lack knowledge and confidence for in-depth discussions of concerns [15]. It may also be that HCPs feel they lack the knowledge and skill to adequately address end of life concerns, leading to feelings of hesitancy in broaching these subjects proactively [16,17]

Second, research points to overall inadequacies in the quality and quantity of dementia related information provided to residents and family caregivers [[18], [19], [20]], which can contribute to erroneous expectations and understanding regarding care. When family caregivers of persons with dementia have not previously engaged in conversations with HCPs about the clinical course of dementia, they may have difficulty anticipating the future care needs of their family member/friend and may not feel adequately prepared for the end of life [[21], [22], [23], [24]]. This lack of ensuing dialogue between HCPs and family caregivers is problematic for both the resident and family member. As regards the resident, family caregivers have reported that persons with dementia have undergone aggressive medical interventions, including hospitalizations in their last 90 days of life, without discussion with HCPs about the burdens or benefits of such interventions [[25], [26], [27]]. When family caregivers understand the expected clinical course of dementia and its poor prognosis, they are less likely to insist on such interventions [28,29]. The effects of poor communication on family caregivers are also considerable. In particular, when caregivers feel unprepared for the death of their friend or relative, caregivers report experiencing higher levels of complicated grief, depressive and anxiety symptoms before the death and into bereavement [30,31].

It is imperative, therefore, that communication between HCPs and family caregivers of persons living with dementia, provides an opportunity to discuss dementia prognosis, important decision-making opportunities, the possibility of dying, and the optimal care of residents with dementia. Preparing for difficult decisions before the occurrence of a health crisis is an important part of resident-centred care and supporting shared decision-making [32]. Bern-Klug (2006) describes such interventions as ‘planting seeds’ through discussions with residents, staff, and family regarding the future and its anticipated outcomes in order to sensitize those involved in care planning [33]. One potentially useful tool that has been identified to initiate this dialogue is the question prompt list. To date, question prompt lists (QPL) have been developed for use in a variety of health care contexts and a range of health conditions including end of life care in nursing homes [[34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39]]. Question prompt lists serve as an inexpensive means of facilitating communication between patients and HCPs, providing a structured list of questions to patients or families early on in their interactions with HCPs, that they may wish to ask HCPs about their illness and treatment. Predominately evaluated in oncology care, QPLs have shown consistent positive effects on patient-physician communication [40,41]. In the randomized controlled trial by Clayton et al. (2007), significant differences between family caregivers using the QPL and controls were also noted, including increases in question asking, expression of concern about end-of-life issues, and mentioning of caregiving issues [36].

Family caregivers feeling inadequately informed and prepared to enact a decisional role in the context of end of life dementia care, has been well documented in the research literature [[42], [43], [44]]. While research has been emerging in the area of decisional support tools in dementia care, we have pursued a different line of inquiry; namely one that fosters communication around questions that are frequently thought about but may be difficult to ask [39,45,46]. Based on the positive results of previous work examining use of a QPL in those with chronic and life-limiting illnesses and their family caregivers, the objective of this study was to develop an empirically derived communication tool, in the form of a QPL, aimed at facilitating communication between family caregivers and HCPs concerning the progression and palliative care needs of NH residents living with dementia.

2. Methods

We used a two-phase, mixed methods approach to create a QPL. Modelling our approach on QPL intervention development in other chronically ill populations, we drew on the expertise of dementia family caregivers, HCPs and experts in the field [47,48]. Although some of the data originates from a study examining information and support needs of dementia family caregivers conducted by the first author, pre-COVID-19 pandemic, the findings reported in this manuscript are distinct and independent [20]. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the institutional review board of the University of Manitoba, and approval for access was obtained from each study site.

2.1. Participants and setting

A purposeful sampling strategy was used to recruit NH care providers from four urban NHs in the Prairie region of Canada. Inclusion criteria required participants be involved in the delivery of direct care to residents, able to communicate comfortably in English, and willing to participate in an interview. After a presentation at each study site by the PI (GT) and a research assistant, recruitment posters and flyers were distributed indicating how interested participants could contact the researchers. Palliative care experts (physicians and clinical nurse specialists who provide consultation services to NH in this urban area) were invited to participate through an email letter sent by their employer. Bereaved family caregivers of persons who had died with a diagnosis of dementia in the past 12 months were identified by an administrator with the NHs who mailed a letter of invitation to participate in the research study on behalf of the researchers. Inclusion criteria were: being at least 18 years of age or older, identified as being actively involved in the resident's last month of life, and able to understand and speak English. When a participant contacted the research team to indicate interest, eligibility criteria were reviewed, and a date, time and location were determined to conduct the interview. Finally, an international group of experts in dementia care were recruited via an email letter of invitation to participate in a telephone interview to review the content of the QPL. These experts were solicited based on their record of publishing in the area of intervention development in dementia care.

2.2. Phase 1 data collection

Semi-structured, face-to-face interviews were conducted with NH care providers, palliative care clinicians and bereaved family caregivers. Prior to conducting the interview, the purpose of the study was reviewed and written informed consent obtained. Each participant group was asked a similar set of questions. During the interview, NH care providers and palliative care clinicians were asked to reflect on: (i) common questions asked by dementia family caregivers about the end of life; and (ii) questions they felt would elicit useful information but that dementia family caregivers had difficulty asking. For bereaved family caregivers, the interviews focused on exploring: (i) questions caregivers believed were important to discuss with HCPs in order to prepare for the death of their relative; and (ii) questions bereaved caregivers wished they had asked HCPs in order to prepare for the death of their relative. Demographic information was collected during the interview. Each interview was audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim to preserve its authenticity; transcripts were reviewed and compared to the recording to ensure accuracy. Mean interview time was 48 min (range: 33 to 120 min).

2.3. Phase 1 data analysis

Qualitative data were analyzed using directed content analysis [49]. Based on the broad thematic areas identified in our previous study [20], these eight themes provided a coding structure to the analysis. Data were analyzed independently by members of the research team (GT, SM, TH, KR), who examined the transcripts and identified text segments that contained content relevant to the broad thematic areas. These areas ranged from the specific such as addressing eating and drinking challenges to the broader, such as life in a NH in general. Once a list of content was generated, through a series of coding meetings, specific questions HCP and bereaved family caregivers deemed important in those thematic areas were written [18]. We examined the transcripts for repetition and patterns of key concepts and terms. Once complete, all transcripts were grouped by participant type to ensure no identified questions or thematic content areas had been missed. This process generated 127 questions organized into 14 content areas within the eight thematic areas.

The 6-person multidisciplinary research team, composed of two nurses, a psychologist, a family social scientist, and two physicians, reviewed the draft QPL to improve organization, clarify question wording, and remove repetitive and redundant questions, resulting in 37 questions in 12 content areas within 6 thematic areas. This team prepared the introductory paragraphs explaining the QPL purpose and instructions on its use.

The 37 draft questions of the QPL were then vetted by the international group of experts. These experts were emailed the draft QPL and asked to provide comments either by telephone (n = 3) or email (n = 2) on the content, clarity, wording, and relevance of the questions. They were also asked to reflect on whether any relevant questions were missing. Based on their feedback, 7 questions were deleted and new titles for the 6 domains suggested to cover the 12 content areas.

2.4. Phase 2 data collection

Once the initial QPL was developed, a second interview with a subset of NH care providers and bereaved family caregivers who indicated they would be willing to review a draft of the tool, was conducted to assess the clarity, sensitivity, importance, and relevance of each item on the QPL. During the interview, participants were asked to evaluate the items as “clear (yes/no); if the items were sensitively worded (yes/no); the importance of each item on a 5-point Likert scale (“is this question important to include on a question prompt sheet for family members?)”, anchored by ‘very important’ and ‘very unimportant; and the relevance of each item on a 4-point scale (“is this question relevant?”), where 1 = ‘very relevant and succinct’; 2 = ‘relevant but needs minor revisions'; 3 = ‘unable to assess or in need of so much revision that it would no longer be relevant’; 4 = ‘not relevant’. Relevance was defined based on the Content Validity Index developed by Lynn [50] where she defines relevance as “relevant to the underlying construct”. We interpreted that to indicate that respondents felt the question was relevant to them and reflected an important question to address in the context of dementia and end-of-life care. Open-ended feedback was obtained including comments and suggestions for improving each question. Feedback was also solicited on the introductory paragraph and general layout of the QPL. Participants' question ratings were recorded on data collection sheets; open-ended responses were captured with verbatim handwritten notes by the research assistant.

The readability of the overall QPL and specific items were assessed using two online tools (Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level Score, Gunning Fog Index) which estimate the amount of formal education required to comprehend the material [51].

2.5. Phase 2 data analysis

Descriptive statistics such as frequencies and means were calculated for dichotomous responses and the Likert scores respectively. Open-ended responses were analyzed in an iterative manner using the same content approach described above. Regardless of participant type (e.g., bereaved family member or HCP), all questions were rated very highly (e.g., very important, very relevant), limiting the usefulness of mean ratings and rather were used for descriptive purposes. In these instances, the open-ended responses were valuable in determining whether changes to the question were required.

3. Results

A total of 40 individuals (n = 17 bereaved family caregivers; n = 7 palliative care experts; n = 26 NH care providers) participated in an interview that led to the generation of the questions on the QPL. The five international experts practiced in Canada (n = 2), the United States (n = 1), Europe (n = 1) and Japan (n = 1). Twenty-one individuals (n = 10 bereaved family caregivers; n = 11 NH care providers) participated in a second interview to provide feedback in Phase 2. Demographic characteristics of the Phase 1 and Phase 2 participants are found in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Participants Phase 1.

| Bereaved Family Caregivers (N = 17) |

Palliative Care Experts (N = 7) |

Nursing Home Care Providers (N = 26) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Female | 12 (70.6) | 5 (71.4) | 24 (92.3) |

| Male | 5 (29.4) | 2 (28.6) | 2 (7.7) |

| Age range (years) | 52–88 (mean = 67.88 years) |

40–62 (mean = 50.86 years) |

23–69 (mean = 46.24 years) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White/Caucasian | 17 (100) | 7 (100) | 16 (61.5) |

| South Asian | – | – | 7 (26.9) |

| Other | – | – | 3 (11.6) |

| Relationship to resident, n (%) | |||

| Spouse/significant other/partner | 8 (47.1) | ||

| Adult child (daughter/son) | 8 (47.1) | ||

| Parent | 1 (5.8) | ||

| Education, n (%) | |||

| Some high school/high school graduate | 7 (41.2) | ||

| College/University graduate | 10 (58.8) | ||

| Length of relative's dementia diagnosis | 6 months – 13 years (mean = 49.18 months) | ||

| Resident length of NH stay before death | 2 months – 5 years (mean = 25.47 months) |

||

| Frequency of visits, n (%) | |||

| Daily | 4 (23.5) | ||

| 3 to 5 times a week | 3 (17.6) | ||

| 2 to 3 times a week | 9 (52.9) | ||

| Once a week | 1 (5.8) | ||

| Professional Affiliation, n (%) | |||

| Registered nurse | – | 10 (38.5) | |

| Licensed practical nurse | – | 4 (15.4) | |

| Clinical Nurse Specialist | 4 (57.1) | – | |

| Physician | 3 (42.9) | – | |

| Health care aide | – | 8 (30.8) | |

| Social worker | – | 1 (3.8) | |

| Speech language therapist | – | 2 (7.7) | |

| Recreation therapist | – | 1 (3.8) | |

| Years in practice | 14–33 (mean = 25.0) |

2–40 (mean = 19.15) |

|

| Years in current role or working in long-term care | 2.5–22 (mean = 9.77) |

2–38 (mean = 15.27) |

|

| Employment status, n (%) | |||

| Full-time | 2 (28.6) | 14 (53.9) | |

| Part-time | 5 (71.4) | 11 (42.3) | |

| Casual | – | 1 (3.8) |

Table 2.

Characteristics of Study Participants – Phase 2.

| Bereaved Family Caregivers (N = 10) |

Nursing Home Care Providers (N = 11) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Female | 7 (70) | 10 (90.9) |

| Male | 3 (30) | 1 (9.1) |

| Age range (years) | 52–86 years (mean = 68.8 years) |

30–69 years (mean = 51.55 years) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| White/Caucasian | 10 (100) | 6 (54.5) |

| South Asian | – | 2 (18.2) |

| Other | – | 3 (27.3) |

| Relationship to resident, n (%) | ||

| Spouse/significant other/partner | 5 (50) | |

| Adult child (daughter/son) | 5 (50) | |

| Education, n (%) | ||

| High school graduate | 3 (30) | |

| College/University graduate | 7 (70) | |

| Length of relative's dementia diagnosis | 4 months – 13 years (mean = 53.6 months) | |

| Resident length of NH stay before death | 2 months – 5 years (mean = 25.3 months) |

|

| Frequency of visitation, n (%) | ||

| Daily | 1 (10) | |

| 4 to 5 times a week | 1 (10) | |

| 2 to 3 times a week | 7 (70) | |

| Once a week | 1 (10) | |

| Professional affiliation, n (%) | ||

| Registered nurse | 5 (45.5) | |

| Licensed practical nurse | 2 (18.2) | |

| Health care aide | 4 (36.4) | |

| Years in practice | 3–40 (mean = 22.64) |

|

| Years in current role or working in long-term care | 3–38 (mean = 17.91) |

|

| Employment status, n (%) | ||

| Full-time | 5 (45.5) | |

| Part-time | 5 (45.5) | |

| Casual | 1 (9.1) |

3.1. Evaluation of the QPL

Both phase 2 participants and the expert panel highly endorsed the questions contained on the QPL. Questions were deleted if the open-ended comments reflected that participants found the wording too vague or content unimportant (e.g., can you tell me about the culture and routines of this place?) or that they assumed a particular behaviour automatically occurred in practice and therefore never thought to ask about it (e.g., how confidential is information about my family member?). Several statements were worded more strongly based on the participant feedback; for example, questions were changed from ‘can we talk about’ to ‘I would like to talk about’. Finally, some questions were simplified based on open-ended responses; rather than stating “what is my family member's care plan and how can I contribute to it?” participants suggested “what can I do to help in caring for my family member who is dying?”. Based on this feedback, an additional 2 content areas were added, along with 8 corresponding questions. Fig. 1 depicts the process.

Fig. 1.

Question Prompt List Development Process of Domains and Questions.

3.2. Final QPL

The final, 38-item QPL is presented in Table 3. The QPL covers 8 content areas that were collapsed into 6 categories addressing: 1) dementia in general; 2) dementia towards the end of life; 3) care of the person dying with dementia; 4) relationships with staff (captures my role as a decision-maker and my role as a caregiver); 5) how I am managing; and 6) general questions about life in a NH facility. Based on the readability assessments, the final overall AD-QPL scored at an 8th grade reading level.

Table 3.

Final QPL.

|

Preparing for the Future: Learning about Dementia and Care near the End of Life Asking questions of health care providers can sometimes be hard. Many of us simply do not know the questions we could be asking to help us better understand and plan for the future. This question prompt list has been designed to open up conversations between you, your family, and members of the health care staff in this facility. The answers to these questions may not be simple or straightforward; dementia affects each person in different ways. By asking these important questions, we hope to provide you with the information you need regarding how things might progress towards the final stages of life and help prepare you for the future. Let’s Talk About…

|

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1. Discussion

Building on the success of QPLs in other areas of health care, this study developed a QPL for family caregivers of those living and dying with dementia to facilitate communication between HCPs and family caregivers around the transitions experienced as the end of life approaches, and associated care provided in NHs. Modeled after the robust approach of Clayton et al., (2003) who developed a 20-page, 112-item QPL for palliative care patients by conducting focus groups and individual interviews of patients, caregivers and palliative care physicians, we similarly approached the development of our QPL seeking the input of a wide variety of participants [47]. The perspectives of HCPs whom are expert in providing palliative care, those who work in NHs, along with past and current family caregivers of people living with dementia, provide a grounded context for the questions that are most frequently encountered as well as those that may have gone unasked or unanswered. When participants have an in-depth knowledge of the topic under investigation, content validity is enhanced [52].

Previous research has noted some hesitancy from HCPs and past researchers towards having explicit questions aimed at the end of life on QPLs [39]. We noted that both our expert panel members and bereaved family caregivers in phase two had no reservations about the inclusion of such questions. In fact, all the items we initially proposed were highly endorsed and stronger wording was suggested in some instances. By including questions that directly address the dementia trajectory and dying, discussing death may become less taboo and family caregivers may feel more empowered in their knowledge of dementia care. Including questions that focus on the caregiver themselves and their coping helps to bring to the fore the importance of caregiver well-being and self-care; an often neglected area of discussion with HCPs [7].

In the development of the QPL, we intentionally adopted a conversational style to the questions. The intent of our QPL is to prompt a more meaningful and in-depth conversation between HCPs and family caregivers, and not to provide all the answers or information in writing as some of the previously developed tools have done for similar populations [46,53,54]. By prompting conversations, this QPL builds on a relational approach to care, and strives to improve partnerships between HCPs and family caregivers; a relationship that at times can be strained in NHs [18]. Future research should explore if the QPL improves HCP and family caregiver self-efficacy around their knowledge of dementia and end-of-life care, and also the impact on relationships between HCP and family caregivers. Cultural variations in communication preferences would also address a limitation of this study.

4.2. Innovation

The culture in many NHs has historically been one that has not always fostered family involvement and that tensions between family caregivers and NH staff can exist. Often these tensions arise due to the conflicting views staff and administrators have about the kinds of roles families should enact [55]. These tensions may manifest in the lack of meaningful engagement of families by staff during care conferences or the active solicitation of their questions or concerns. Research has illustrated that during care conferences, families are systematically excluded from contributing their perspectives by the highly scripted process which precludes families from knowing what to expect or knowing if they are allowed to contribute or even ask questions [56]. Further, family members have expressed concerns with raising issues for fear that their relative may be the target of reprisals by staff [55]. When expectations are unclear and communication is poor, the ability to foster inclusive spaces and building trust is hampered [56,57]. The QPL developed by our team can provide a meaningful tool to redress this gap and empowers families to ask questions about their role on the care team and the care being provided to their family member. Further, it may foster and strengthen family-healthcare provider relationships using open dialogue during care conferences and the promotion of partnerships [58].

The QPL has also the potential to improve advance care planning (ACP) and fostering health care provider confidence in the initiation of these conversations. Rainsford and colleagues [59] noted that NH staff often feel they do not have the skills nor the comfort in opening end-of-life conversations with families, and often wait for families to broach this subject [60]. The systematic review by Gonella et al.[61] reports that families are dissatisfied with the quality of end-of-life conversations and the information they receive; both of which significantly impact the ability of families to make decisions and engage in ACP [62]. This is problematic in that ACP has been shown to have positive benefits for both residents and their families [59]. Having the QPL available to provide prompts that can guide both families and health care providers with these conversations will foster confidence in decision making; a finding reported in the integrative review by Gonella et al. [9] on the value of structured conversations supplemented with written information. In our development of a QPL developed specifically with and for family caregivers of persons living with dementia in the NH setting, we have ensured that topical areas considered critical to address in conversations have been included. By using the QPL to guide ACP discussion, mutual benefits for residents, families and NH staff may be achieved.

5. Conclusion

This study has developed a 38-item QPL that can be used by HCPs and researchers to facilitate question asking and encourage engagement with family caregivers of NH residents with dementia. Further studies are needed to determine the effectiveness of the QPL in assisting HCP and family caregiver communication.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Genevieve N. Thompson: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Data curation, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Thomas F. Hack: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. Harvey Max Chochinov: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Kerstin Roger: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. Philip D. St John: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. Susan E. McClement: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research/ Research Manitoba Regional Partnership Program grant [grant number 201103RPA-254286].

Contributor Information

Genevieve N. Thompson, Email: Genevieve.thompson@umanitoba.ca.

Thomas F. Hack, Email: thack@sbrc.ca.

Harvey Max Chochinov, Email: Harvey.chochinov@cancercare.mb.ca.

Kerstin Roger, Email: Kerstin.Roger@umanitoba.ca.

Philip D. St John, Email: pstjohn@hsc.mb.ca.

Susan E. McClement, Email: Susan.McClement@umanitoba.ca.

References

- 1.Bollig G., Gjengedal E., Henrik Rosland J. They know!- Do they? A qualitative study of residents and relatives views on advance care planning, end-of-life care, and decision-making in nursing homes. Palliat Med. 2016;30:456–470. doi: 10.1177/0269216315605753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldberg T.H., Botero A. Causes of death in elderly nursing home residents. J Amer Med Direct Assoc. 2008;9:565–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hung L., Yang S.C., Guo E., Sakamoto M., Mann J., Dunn S., et al. Staff experience of a Canadian long-term care home during a COVID-19 outbreak: A qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 2022;21 doi: 10.1186/s12912-022-00823-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Estabrooks C.A., Straus S.E., Flood C.M., Keefe J., Armstrong P., Donner G.J., et al. Restoring trust: COVID-19 and the future of long-term care in Canada. Facets. 2020;5:651–691. doi: 10.1139/FACETS-2020-0056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith-MacDonald L., Venturato L., Hunter P., Kaasalainen S., Sussman T., McCleary L., et al. Perspectives and experiences of compassion in long-term care facilities within Canada: A qualitative study of patients, family members and health care providers. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12877-019-1135-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanson L.C. Notes from the editor: Communication is our procedure. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:1084–1085. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.9647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gabbard J., Johnson D., Russell G., Shenita S., Williamson J.D., McLouth L.E., et al. Prognostic awareness, disease and palliative understanding among caregivers of patients with dementia. J Hospice Palliat Med. 2020;37:683–691. doi: 10.1177/1049909119895497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caron C.D., Griffith J., Arcand M. Decision making at the end of life in dementia: How family caregivers perceive their interactions with health care providers in long-term-care settings. J Appl Gerontol. 2005;24:231–247. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonella S., Mitchell G., Bavelaar L., Conti A., Vanalli M., Basso I., et al. Interventions to support family caregivers of people with advanced dementia at the end of life in nursing homes: A mixed-methods systematic review. Palliat Med. 2021;00:1–24. doi: 10.1177/02692163211066733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hertzberg A., Ekman S.L., Axelsson K. Staff activities and behaviour are the source of many feelings: relatives’ interactions and relationships with staff in nursing homes. J Clin Nurs. 2001;10:380–388. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2001.00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jang H.-Y., Song E.-O., Ahn J.-W. Development and validation of the Scale for Staff-Family Partnership in Long-term Care (SSFPLC) Int J Older People Nurs. 2001;00 doi: 10.1111/opn.12426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marziali E., Shulman K., Damianakis T. Persistent family concerns in long-term care settings: meaning and management. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2006;7:154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hebert R.S., Schulz R., Copeland V., Arnold R.M. What questions do family caregivers want to discuss with health care providers in order to prepare for the death of a loved one? An ethnographic study of caregivers of patients at end of life. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:476–483. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoek L.J., Cm Van Haastregt J., de Vries E., Backhaus R., Hamers J.P., Verbeek H., et al. Partnerships in nursing homes: How do family caregivers of residents with dementia perceive collaboration with staff? Article Dementia. 2019;20:1631–1648. doi: 10.1177/1471301220962235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wittenberg-Lyles E., Oliver D.P., Demiris G., Washington K.T., Regehr K., Wilder H.M. Question asking by family caregivers in hospice interdisciplinary team meetings. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2010;3:82–88. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20090731-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moir C., Roberts R., Martz K., Perry J., Tivis L. Communicating with patients and their families about palliative and end-of-life care: Comfort and educational needs of nurses. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2015;21(3):109–112. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2015.21.3.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Unroe K.T., Cagle J.G., Lane K.A., Callahan C.M., Miller S.C. Nursing home staff palliative care knowledge and practices: Results of a large survey of frontline workers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;50(5):622–629. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harper A.E., Terhorst L., Moscirella M., Turner R.L., Piersol C.V., Leland N.E., et al. The experiences, priorities, and perceptions of informal caregivers of people with dementia in nursing homes: A scoping review, Article. Dementia. 2019;20:2746–2765. doi: 10.1177/14713012211012606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCleary L., Venturato L., Thompson G., Kaasalainen S. In Canadian Association on Gerontology Annual Scientific and Educational Meeting. October 21, 2017. Family, staff, and resident perspectives on end of life care for persons with dementia in LTC home. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson G., Hack T., Rodger K., St. John P., Chochinov H., McClement S. Clarifying the information and support needs of family caregivers of nursing home residents with advancing dementia. Dementia. 2021;20:1250–1269. doi: 10.1177/1471301220927617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Durepos P., Akhtar-Danesh N., Ploeg J., Sussman T., Kaasalainen S. Caring ahead: Mixed methods development of a questionnaire to measure caregiver preparedness for end-of-life with dementia. Palliat Med. 2021;35:768–784. doi: 10.1177/0269216321994732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Givens J.L., Kiely D.K., Carey K., Mitchell S.L. Healthcare proxies of nursing home residents with advanced dementia: Decisions they confront and their satisfaction with decision-making. J Am Geriat Soc. 2009;57:1149–1155. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parker S.M., Clayton J.M., Hancock K., Walder S., Butow P.N., Carrick S., et al. A systematic review of prognostic/end-of-life communication with adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness: patient/caregiver preferences for the content, style, and timing of information. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:81–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pashby P., Hann J., Sunico M.E. Dementia care planning: shared experience and collaboration. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2009;52:837–848. doi: 10.1080/01634370903088051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Honinx E., Piers R.D., Onwuteaka-Philipsen B.D., Payne S., Szczerbińska K., Gambassi G., et al. Hospitalisation in the last month of life and in-hospital death of nursing home residents: a cross-sectional analysis of six European countries. Brit Med J Open. 2021;11:47–86. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lamberg J.L., Person C.J., Kiely D.K., Mitchell S.L. Decisions to hospitalize nursing home residents dying with advanced dementia. J Am Geriat Soc. 2005;53:1396–1401. doi: 10.1111/J.1532-5415.2005.53426.X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Volicer L., Hurley A.C., Blasi Z.V. Characteristics of dementia end-of-life care across care settings. Am J Hospice Palliat Med. 2003;20:191–200. doi: 10.1177/104990910302000307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mitchell S.L., Teno J.M., Kiely D.K., Shaffer M.L., Jones R.N.D., Prigerson H.G., et al. The clinical course of advanced dementia. New Eng J Med. 2009;361:1529–1538. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902234. https://www-nejm-org.uml.idm.oclc.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMoa0902234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Steen J.T., Onwuteaka-Philipsen B.D., Knol D.L., Ribbe M.W., Deliens L. Caregivers’ understanding of dementia predicts patients’ comfort at death: a prospective observational study. BMC Med. 2013;11:105. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-105. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/11/105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hebert R.S., Prigerson H.G., Schulz R., Arnold R.M. Preparing caregivers for the death of a loved one: a theoretical framework and suggestions for future research. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:1164–1171. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lobb E.A., Kristjanson L.J., Aoun S.M., Monterosso L., Halkett G.K.B., Davies A. Predictors of complicated grief: A Systematic review of empirical studies. Death Stud. 2010;34:673–698. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2010.496686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van der Steen J.T. Dying with dementia: What we know after more than a decade of research. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2010;22:37–55. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bern-Klug M. Calling the question of “possible dying” among nursing home residents: triggers, barriers, and facilitators. J Social Work in End-of-Life Palliat Care. 2010;2:61–85. doi: 10.1300/J457v02n03_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arthur J., Yennurajalingam S., Williams J., Tanco K., Liu D., Stephen S., et al. Development of a question prompt sheet for cancer patients receiving outpatient palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2016;19:883–887. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2015.0545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bavelaar L., Nicula M., Morris S., Kaasalainen S., Achterberg W.P., Loucka M., et al. Developing country-specific questions about end-of-life care for nursing home residents with advanced dementia using the nominal group technique with family caregivers. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;105:965–973. doi: 10.1016/J.PEC.2021.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clayton J., Butow P.N., Tattersall M.H.N., Devine R.J., Simpson J.M., Aggarwal G., et al. Randomized controlled trial of a prompt list to help advanced cancer patients and their caregivers to ask questions about prognosis and end-of-life care. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:715–723. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.7827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lambert K., Lau T.K., Davison S., Mitchell H., Harman A., Carrie M. Does a renal diet question prompt sheet increase the patient centeredness of renal dietitian outpatient consultations? Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103:1645–1649. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martinali J., Bolman C., Brug J., van den Borne B., Bar F. A checklist to improve patient education in a cardiology outpatient setting. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;42:231–238. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(00)00126-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van der Steen J.T., Heck S., Juffermans C.C.M., Garvelink M.M., Achterberg W.P., Clayton J., et al. Practitioners’ perceptions of acceptability of a question prompt list about palliative care for advance care planning with people living with dementia and their family caregivers: a mixed-methods evaluation study. Brit Med J Open. 2021;11 doi: 10.1136/BMJOPEN-2020-044591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brandes K., Linn A.J., Butow P.N., van Weert J.C. The characteristics and effectiveness of question prompt list interventions in oncology: A systematic review of the literature. Psycho-Oncology. 2015;24:245–252. doi: 10.1002/pon.3637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keinki C., Momberg A., Clauß K., Bozkurt G., Hertel E., Freuding M., et al. Effect of question prompt lists for cancer patients on communication and mental health outcomes-A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104:1335–1346. doi: 10.1016/J.PEC.2021.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arruda E.H., Paun O. Dementia caregiver grief and bereavement: An integrative review. West J Nurs Res. 2017;39:825–851. doi: 10.1177/0193945916658881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carter G., McLaughlin D., Kernohan W.G., Hudson P., Clarke M., Froggatt K., et al. The experiences and preparedness of family carers for best interest decision-making of a relative living with advanced dementia: A qualitative study. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74:1595–1604. doi: 10.1111/jan.13576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hovland-Scafe C.A., Kramer B.J., Bowers B.J. Preparedness for death: How caregivers of elders with dementia define and perceive its value. Gerontologist. 2017;57:1093–1102. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arcand M., Brazil K., Nakanishi M., Nakashima T., Alix M., Desson J.F., et al. Educating families about end-of-life care in advanced dementia: Acceptability of a Canadian family booklet to nurses from Canada, France, and Japan. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2013;19:67–74. doi: 10.12968/IJPN.2013.19.2.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sussman T., Kaasalainen S., Lee E., Akhtar-Danesh N., Strachan P.H., Brazil K., et al. Condition-specific pamphlets to improve end-of-life communication in long-term care: Staff perceptions on usability and use. J Amer Med Direct Assoc. 2019;20:262–267. doi: 10.1016/J.JAMDA.2018.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clayton J., Butow P., Tattersall M., Chye R., Noel M., Davis J., et al. Asking questions can help: Development and preliminary evaluation of a question prompt list for palliative care patients. Brit J Cancer. 2003;89:2069–2077. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hebert R.S., Schulz R., Copeland V.C., Arnold R.M. Pilot testing of a question prompt sheet to encourage family caregivers of cancer patients and physicians to discuss end-of-life issues. Am J Hospice Palliat Care. 2009;26:24–32. doi: 10.1177/1049909108324360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hsieh H., Shannon S. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lynn M.R. Determination and quantification of content validity. Nurs Res. 1986;35:382–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McInnes N., Haglund B.J.A. Readability of online health information: Implications for health literacy. Inform Health Soc Care. 2011;36:173–189. doi: 10.3109/17538157.2010.542529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schulte-Vieting T., Siegle A., Jung C., Villalobos M., Thomas M. Developing a question prompt list for the oncology setting: A scoping review. Patient Educ Couns. 2021 doi: 10.1016/J.PEC.2021.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arcand M., Monette J., Monette M., Sourial N., Fournier L., Msc N., et al. Educating nursing home staff about the progression of dementia and the comfort care option: Impact on family satisfaction with end-of-life care. J Amer Med Direct Assoc. 2009;10:50–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nakanishi M., Miyamoto Y., Long C.O., Arcand M. A Japanese booklet about palliative care for advanced dementia in nursing homes. I J Palliat Nurs. 2015;21:385–391. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2015.21.8.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Puurveen G., Baumbusch J., Gandhi P. From family involvement to family inclusion in nursing home settings: A critical interpretive synthesis. J Fam Nurs. 2018;24:60–85. doi: 10.1177/1074840718754314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Puurveen G., Cooke H., Gill R., Baumbusch J. A seat at the table: The positioning of families during care conferences in nursing homes. Gerontologist. 2019;59:835–844. doi: 10.1093/geront/gny098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gonella S., Campagna S., Basso I., De Marinis M., Giulio P. Mechanisms by which end-of-life communication influences palliative-oriented care in nursing homes: A scoping review. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102:2134–2144. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2019.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gonella S., Campagna S., Dimonte V. A situation-specific theory of end-of-life communication in nursing homes. Int J Enviorn Res Public Health. 2023;20:869. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20010869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rainsford S., Dykgraaf S., Kasim R., Phillips C., Glasgow N. Traversing difficult terrain’. Advacne care planning in residential aged care through multidisciplinary case conferences: A qualitative interview study exploring the experiences of families, staff and health professionals. Palliat Med. 2021;35:1148–1157. doi: 10.1177/02692163211013250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Anderson R., Bloch S., Armstrong M., Stone P., Low J. Communication between healthcare professionals and relatives of patients approaching the end-of-life: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. Palliat Med. 2019;33:926–941. doi: 10.1177/0269216319852007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gonella S., Basso I., Dimonte V., Martin B., Berchialla P., Campagna S., et al. Association between end-of-life conversations in nursing homes and end-of-life care outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Amer Med Direct Assoc. 2019;20:249–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2018.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mota-Romero E., Rodríguez-Landero O., Dieguez-Moya R., Cano-Garzón G., Montoya-Juárez R., Puente-Fernández D. Information and advance care directives for end-of-life residents with and without dementia in nursing homes. Healthcare. 2023;11:353. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11030353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]