Abstract

Introduction

In 2017, NHS England introduced proactive identification of frailty into the General Practitioners (GP) contract. There is currently little information as to how this policy has been operationalised by front-line clinicians, their working understanding of frailty and impact of recognition on patient care. We aimed to explore the conceptualisation and identification of frailty by multidisciplinary primary care clinicians in England.

Methods

Qualitative semi-structured interviews were conducted with primary care staff across England including GPs, physician associates, nurse practitioners, paramedics and pharmacists. Thematic analysis was facilitated through NVivo (Version 12).

Results

Totally, 31 clinicians participated. Frailty was seen as difficult to define, with uncertainty about its value as a medical diagnosis. Clinicians conceptualised frailty differently, dependant on job-role, experience and training. Identification of frailty was most commonly informal and opportunistic, through pattern recognition of a frailty phenotype. Some practices had embedded population screening and structured reviews. Visual assessment and continuity of care were important factors in recognition. Most clinicians were familiar with the electronic frailty index, but described poor accuracy and uncertainty as to how to interpret and use this tool. There were different perspectives amongst professional groups as to whether frailty should be more routinely identified, with concerns of capacity and feasibility in the current climate of primary care workload.

Conclusions

Concepts of frailty in primary care differ. Identification is predominantly ad hoc and opportunistic. A more cohesive approach to frailty, relevant to primary care, together with better diagnostic tools and resource allocation, may encourage wider recognition.

Keywords: frailty, primary care, general practice, qualitative research, older people

Key Points

Concepts of frailty in primary care differ. Primary care clinicians lack formal training on frailty.

Despite uniform NHS policy frailty identification in primary care is heterogeneous. Usually, it is ad hoc and informal.

Recent and ongoing changes to primary care are impeding frailty recognition.

A more cohesive approach requires a better evidence-base, education of front-line staff and resource allocation.

Introduction

By 2032, 22% of the UK population will be aged over 65 [1]. Faced with this increasingly aged and multimorbid population, there has been an increasing interest in frailty as a descriptor to differentiate population needs. Frailty is ‘multidimensional syndrome characterized by decreased reserve and diminished resistance to stressors’ [2]. Individuals living with frailty are more at risk of falls [3], delirium [4], fluctuating disability [5] and adverse effects of polypharmacy. Increasing frailty is associated with an increasing risk of hospitalisation, dependency and death [6, 7]. Often there is a spiral of decline, which is distressing for patients and carers [8, 9]. Unsurprisingly, General Practitioners (GPs) spend more time caring for older adults living with frailty compared with those without. [10].

Despite its potential significance in the care of older populations, there remains no consensus on operational definition or unified approach to measurement [11, 12]. Contemporary research and policy perspectives align in conceptualising frailty as a quantifiable variable, which is amenable to goal-orientated patient-centred care [8, 11]. However, lay and non-specialist medical views often differ. Frailty is, instead, a label, encountered with end-of-life syndromes or a high degree of functional dependence [13, 14], or not even an illness at all [15]. There is little published evidence on definitions of frailty amongst UK primary care clinicians [16]. Research from other countries has demonstrated that GPs tend to recognise frailty in the most severe end-state, without use of specific tools or assessments [17, 18].

Recent policy has changed the landscape of frailty identification in UK primary care. As part of the NHS Long Term Plan [19], routine identification was incorporated into the 2017/18 General Medical Services (GMS) contract. Underpinning this policy is the electronic frailty index (eFI), which uses electronic health records to bracket groups of patients into grades of frailty [20]. The eFI has good external validity for identifying risk of hospitalisation and death within populations [21] but has not been tested at an individual level. Early signals of the eFI in practice suggest it may be insensitive, with over-identification of the severely frail [22, 23]. Within this timeframe, there has also been organisational change with the introduction of Primary Care Networks (PCNs). This has increased the number of non-physician clinicians, whereas total GP numbers are decreasing [24]. The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated a shift towards remote consultations and a reduction in home visits [25, 26]. This has the potential to fragment care, but also may provide new opportunities for developing frailty pathways and expertise [27].

Four years on from policy announcement, through COVID-19 pandemic, there is a need to understand how frailty is identified from the range of professionals currently working in general practice.

The aims of this study are to:

Explore how different clinicians providing primary care to older adults conceptualise frailty.

Understand how frailty is identified in primary care and explore factors that might account for variation in practice.

Methods

Recruitment

We recruited healthcare professionals who had been working in primary care in England for at least 1 year and had regular contact with adults over the age of 65. Alongside GPs, we recruited other multidisciplinary professionals, including advanced nurse practitioners (ANPs), paramedic practitioners, clinical pharmacists and physician associates (PAs), who we will refer to as clinical practitioners (CPs). CPs all worked within GP practices, and autonomously consulted with a wide range of patients, including those living with frailty. Some held prescribing qualifications. The mix of healthcare professionals recruited to the study reflects those most commonly delivering front-line primary care services since the introduction of the additional roles reimbursement scheme in 2019 PCN contract [28]. Clinicians were recruited through emails from the RCGP Research Surveillance Centre, advertisements on social media groups and snowballing from other participants. They were offered a small reimbursement for their time. Sampling was purposive, aiming to maximise variation in clinician experience, practice size and location and job role, including specialist interest in older people or frailty. Recruitment was ongoing until there was sufficient explanatory power for generated themes, and there had been no amendments to topic guide or novel information for several interviews.

Data collection

One researcher (A.S., an academic clinical fellow/GP trainee) who has been trained in qualitative methods, conducted all interviews, between April and September 2021. Initial interviews were discussed and transcripts reviewed by another researcher (M.G., senior qualitative researcher). Three participants were known to the interviewee in a professional capacity, prior to the study. Verbal and written consent was obtained prior to the interview. Interviews were either conducted over Microsoft Teams or telephone, were audio-recorded and lasted between 30 and 70 min. A flexible topic guide was used (see Supplementary Table 1), developed and piloted by the researchers. Data collection and analysis were concurrent, with regular discussion of findings between three authors (AES, MG and G.H.) so the topic guide evolved as interviews suggested new themes, or topics for further exploration. Interviews were transcribed verbatim by a university-approved transcribing service, and field notes were made during and after the interview, by the researcher.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis was used [29], supported by NVivo (version 12) software. One researcher (A.S.) coded all interviews. Analysis was guided by the constant comparative method [30], which involves reading and familiarisation with field notes and transcripts, with identification of initial themes, then open and systematic coding. Coding of initial interviews generated an initial framework, which was discussed between the team (A.S., M.G. and G.H.). Earlier interviews were re-coded in the light of new information. Identified categories and themes were discussed critically amongst the research group to ensure credibility. Four patient and public involvement (PPI) contributors were recruited either because they had experience of frailty themselves, or caring for a relative with frailty. Results were discussed across three meetings with PPI contributors to explore how these resonated with their own experiences.

Results

Seventy primary care clinicians expressed interest in participating in the study. In all, 31, from 27 different practices, were interviewed. Participant characteristics are displayed in Table 1. The percentage of non-white patients in the primary care settings where our participants worked varied from 1.5 to 82.9% and measures of social deprivation varied from least to most deprived deciles.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants

| Job role | N = 31 |

|---|---|

| GP partner | 8 |

| Salaried GP | 4 |

| ANP | 4 |

| Clinical pharmacist | 7 |

| Paramedic practitioner | 2 |

| PA | 6 |

| Years of experience a | N = 31 |

| 1–2 | 15 |

| 3–5 | 2 |

| 6–10 | 7 |

| 11–15 | 3 |

| 16–20 | 3 |

| ≥20 | 1 |

| Prescriber | N = 30 |

| Yes | 21 |

| No | 9 |

| Location | N = 27 |

| Rural | 1 |

| Suburban | 12 |

| Urban | 8 |

| Mixed | 6 |

| Practice size | N = 27 |

| Small | 2 |

| Medium | 5 |

| Large | 5 |

| Very large | 8 |

| PCN | 7 |

| Percentage of practice population over 65 | N = 27 |

| ≤10% | 5 |

| 11–15% | 6 |

| 16–20% | 7 |

| 21–25% | 7 |

| ≥26% | 2 |

| Specialist interest | |

| Frailty specialist | 8 |

| Care home responsibilities | 7 |

| Home visits (not including GPs) | 3 |

aYears of experience as an autonomous primary care practitioner. The shift in distribution to fewer years of experience reflects that many CP roles were not available prior to the introduction of Primary Care Networks in July 2019. Many of the CPs had many years of prior experience within other community settings from which they could draw on experiences of frailty.

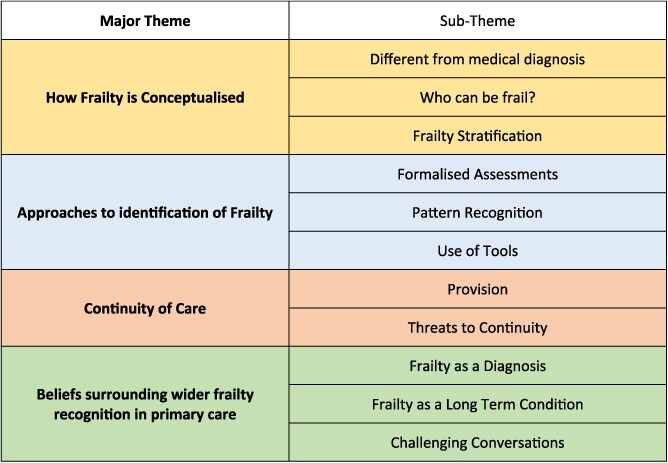

Main themes identified are displayed in Box 1 and discussed in further detail below.

Box 1.

Main themes identified

|

Theme 1: conceptualisation of frailty

There was widespread uncertainty as to how to define frailty. Many clinicians described a lack of common definition both in primary care and amongst the public: ‘Although I know there are definitions out there. And so, everyone’s opinion and view and idea of what it means might be different and actually, some people could take it as a very negative connotation’ (024-PA, 1–2 years of experience). Frailty was perceived as different from medical conditions such as asthma or heart failure and more subjective in detection: ‘frailty was always an adjective rather than a diagnosis’ (001-GP Partner, 16–20 years of experience).

What is frailty?

Concepts of frailty differed between clinicians. Some clinicians used a broad application: ‘anybody who was finding getting older difficult’ (025-GP Partner, 16–20 years of experience) versus those who felt it described deteriorating health in oldest old or actively dying patients. Equally, some clinicians used it to describe vulnerability to ill health in those aged under 65, or within different aspects of a biopsychosocial health model.

‘I feel frailty exists in several domains, not just the physical domain, but mental, functional, cognitive, emotional. So, somebody can be really emotionally frail and, you know, cognitively frail and yet have quite a strong body’ (010-ANP, 1–2 years of experience).

Most clinicians, aside from those who had specialist frailty interests or job roles, described little or no formalised training in frailty. Pharmacists and PAs, in particular, reported a lack of education, even during primary clinical qualifications. Thus, conceptualisation of frailty was predominantly based on experiential knowledge ‘you just learn on the job really’ (023-GP Partner, 6–10 years of experience). Some less experienced clinicians conceptualised frailty in reference to the eFI, as they had developed familiarity with this screening tool whilst viewing electronic health records: ‘So, whenever we kind of go in to a patient that potentially is frail, it’ll just come up with … eFI index on the side. So, that’s probably the kind of definition that I would mainly use’ (015-Pharmacist, 1–2 years of experience).

Frailty stratification

There was uncertainty as to how and if frailty could be stratified: ‘I would just say generally frail but I wouldn’t know how to classify it’ (011-Pharmacist, 1–2 years of experience). Many clinicians did acknowledge a continuum of frailty, and there was some familiarity with eFI grades of mild, moderate and severe frailty. However, clinicians were unfamiliar as to the process and utility of differentiation between grades, especially for mild frailty:

‘If they’ve walked into the surgery…, they’re fit and able and you can talk to them and there’s no signs of dementia, and you do sort of think, “Well, why have you got this mild frailty score?” So, sometimes I think it [the eFI] is just a calculation… it’s not really about the person themselves’ (029-PA, 3–5 years of experience).

One ANP, who was the frailty lead for a PCN, described how stratifying frailty did help map trajectories of decline and direct interventions.

‘I remember meeting her; a really cute old lady… in her stilettos that danced… and then she broke her ankle… that changed her from mild frail up to moderate. And then I went in and, you know, watched her for a while after a broken ankle thinking, ‘Is she going to get back; isn’t she?’ And then she’s tipped to severe and then actually, she’s come back down now because she’s not in the stilettos but she is back out. (022-ANP, 6–10 years of experience)

Theme 2: different approaches to identification

Formalised assessments

Six clinicians worked within practices where frailty was systematically identified amongst older patients. At risk patients were offered frailty assessments through extended consultations or home visits. Assessments were recorded on specific templates and frailty typically problem coded on the notes. These clinicians were generally working in localities with higher numbers of patients aged over 65. Practices were also more rural, affluent and less ethnically diverse.

Clinicians broadly spoke positively of this model with benefits that a holistic assessment could bring to both patient and for future clinical consultations: ‘Business case amongst ourselves was it was clear; people said, “I want to stay at home. I want to be supported”. …So, we manage a lot of complex care in people’s houses who can’t get out’ (021-GP Partner, 11–15 years of experience). Formal diagnosis also facilitated open conversations about advance care planning. This model was ‘heavy…hardwork’ (007-Salaried GP, 6–10 years of experience), which required specific funding streams, outside of usual GMS contractual income.

There was challenge, however, in how to identify patients who would most benefit from these assessments. Two participants worked in practices which used eFI for older adult population screening. Both had found the eFI ‘pretty useless’ (007-Salaried GP, 6–10 years of experience) as ‘identifies probably fifty percent but actually, there were a lot of patients that came to the clinic that didn’t need to be in the clinic and there were a lot of patients that weren’t identified that needed support’ (012-Paramedic Practitioner). Several other practices, which had access to frailty assessments, opted instead to refer ‘when somebody is wobbling’ (023-GP Partner, 6–10 years of experience). Referrals were not limited to clinicians, and often generated by healthcare assistants, receptionists and patient’s relatives.

In other practices, only patients with diabetes and hypertension were routinely screened for frailty. Calculation of the eFI is now part of annual review protocols, linked to Quality Outcomes Framework (QOF) indicators for these conditions. In contrast to the assessments above clinicians described using the eFI at face value and this having little impact on subsequent decision-making—‘I don’t do anything about it apart from click it when I’m supposed to do; click the little box that gives you the calculation’ (020-ANP, ≥20 years of experience).

Pattern recognition

Whilst clinicians found it difficult to define frailty, they described similar clinical characteristics they used to recognise it in practice. Poor mobility, weight loss and generalised weakness were attributes most often mentioned.

‘It would be the patient who sort of takes a very long time to get from their waiting room chair into the room…difficult to stand up, maybe they’re walking slowly and maybe their relative is sort of supporting their arm, then I’m thinking, ‘Actually, this looks like a frail sort of elder person’. (002-GP Partner, 6–10 years of experience)

Other signs clinicians used were often specific to their roles. For example, a paramedic described assessing living environment during home visits—‘the quality of the house - is it clean? I like looking in the fridge because if there’s out of date milk, you know, you go into somebody’s house and you see all they eat is Mueller corner yoghurts. That tells me so much’ (030-Paramedic Practitioner, 3–5 years of experience).

Clinicians described how this pattern recognition relied heavily on an opportunistic visual assessment of the patient, whereas they were consulting for other reasons. Consequentially frailty identification was much harder with the shift to remote consultation during COVID-19 pandemic—‘We slightly sort of lose the opportunistic stuff like, “Oh, you looked a bit wobbly when you walked in, Mr Jones. Shall I just check your blood pressure?”’ (002-GP Partner, 6–10 years of experience).

Informal methods of identifying frailty also rarely led to coding on the patient’s notes. CPs more often described a lack of confidence without a diagnostic tool or framework. More experienced GPs reflected they did not code frailty as they did not conceptualise it as ‘an actual condition’ (009-Salaried GP, 6–10 years of experience). In contrast, clinicians often coded a patient as ‘Housebound’ as this was more easily definable. For some clinicians this was synonymous with frailty: ‘I find all my housebound are frail; nearly all of them are; that’s why they’re housebound…’ (003-GP Partner, 16–20 years of experience).

Use of tools

Electronic frailty index

The majority of clinicians had some familiarity with the eFI, but there was a wide degree of variability as to how and why it was being used. It had high visibility within electronic health records, and clinicians described positive experiences where prompts offered additional information—‘it will give you a little bit of a guide, so you can think, “Well actually, you know, you are at risk of severe frailty. Maybe I need to think about how I present your options to you”’ (005-Salaried GP, 1–2 years of experience).

However, many clinicians, especially GPs, described poor accuracy of the eFI: ‘Just wildly plucks the title when... so, it misses severely frail people, but it makes very well, capable, still working aged people, severely frail, and I don’t know how they draw their data’ (007-Salaried GP, 1–2 years of experience). As such, there was ambiguity as to how to interpret the score, and many clinicians were unaware that this should be correlated with a patient assessment. Lack of confidence in the eFI arose in some cases from a mismatch with conceptualisation of frailty: ‘the frailty that’s being caught in the computer system is based more on underlying morbidity that’s listed in their problems, which I don’t find is the same concept of frailty that I have’ (001-GP Partner, 16–20 years of experience).

Rockwood clinical frailty scale

There was less awareness of the clinical frailty scale, which has not been integrated into all primary care computer systems. Clinicians using it regularly had more experience or specialist interest in frailty. It was considered easy to use, accurate, with good clinical utility—‘It really helps you think about, “Well what can this person manage?” And I like the sort of seven/eight/nine bit of Rockwood; I like the idea that on an eight you’re unlikely to survive the next infection. I think that’s a sort of quite a useful thought to have’ (025-GP Partner, 16–20 years of experience).

Theme 3: continuity of care

GPs working in small practices with good continuity of care described frailty identification as part of the implicit process of knowing patients well and recognising step-changes in patient functioning. These clinicians were less likely to use the eFI or code frailty on patients notes: ‘I know that’s [the eFI] in the notes but if I’m completely honest with you, I’ll glance at it but I’ll think, “I already know you’re frail”, because I’m doing that all the time’ (006-GP Partner, 6–10 years of experience).

CPs were often not afforded continuity of care, and predominantly interacted with older patients during one-off episodic contacts, e.g. acute illness. Often frailty was simply ‘not always the main priority in consultations’ (013-Pharmacist, 1–2 years of experience) and thus was overlooked. Documentation often focused on the acute problem even if frailty was apparent. Clinicians reflected these working patterns reduced their exposure and experiential knowledge to ‘develop and recognise these signs of frailty and declining frailty’ (027-PA, 1–2 years of experience). In contrast, where CPs were employed in specific roles that increased contact with those living with frailty, e.g. for home visits, they described ability to provide good continuity of care, above that of GP colleagues.

Threats to continuity of care

Many clinicians reflected that they had lost touch with older patients during the pandemic, as access to care was reduced and older patients had sought less help, ‘either through fear or through stoicism’ (001-GP Partner, 16–20 years of experience). Concurrently patients had also become frailer because of social isolation and reduced physical activity. Many clinicians were struggling to return to a normal service because of overwhelming demand: ‘There isn’t much chance for me to say, “I’m going to go and look at my frail list”, as I’m obviously on my knees with everybody that thinks they need to see me let alone the ones I think I need to see’ (004-GP Partner, 6–10 years of experience). These pressures meant clinicians had ‘lost the ability to notice and spot and put in things along the way’ (005-Salaried GP, 6–10 years of experience).

Diversification of the workforce and fragmentation of care was also seen as a threat to continuity of care offered by traditional models of general practice. For instance, commissioning of external home visiting services reduced recognition of frailty, as information about a patient’s everyday functioning and living arrangements was lost in communication between teams. One clinician argued that in order for GPs to retain oversight over patient care a different model was needed: ‘we’re going to have to stop seeing other patients and devote time to catching up with the team and discussing MDTs about it all and saying, “OK, who’s on our radar; what are they doing; do I need to go?”’ (021-GP Partner, 11–15 years of experience).

Theme 4: beliefs surrounding wider frailty recognition in primary care

Risks and benefits of frailty as a diagnosis

Differing concepts of frailty influenced how clinicians felt about the value of labelling it. For some clinicians who felt frailty was more of a descriptor than a diagnosis there were concerns about overreach: ‘So, are we just coding old age? We know as people get older the wheel’s going to start falling off in certain ways’ (005-Salaried GP, 1–2 years of experience). The lack of a common standard or definition could also lead to patient harm: ‘as soon as someone had the label…it might make someone think, “Oh well, they’re very frail, so maybe we shouldn’t treat this”, …and actually that might not be the best interest of the patients’ (024-PA, 1–2 years of experience).

Others were firm advocates of recognising frailty. This, they believed, led to better care for patients, by opening conversations about their preferences during future ill health or illness and improving communication between clinicians. In particular, diagnosing frailty helped prevent harm from inappropriate hospital admissions: ‘it’s almost like there’s a tipping point where hospital will actually be worse for you, and all your rights will be taken away; you’ll never be able to make a decision for yourself again... our system is appalling for that, isn’t it?’ (025-GP Partner, 16–20 years of experience).

Some clinicians also believed that early identification and proactive management could attenuate future disability: ‘if you can manage to get some kind of message to them that matters - that you can maintain your physical mobility and reduce frailty by, you know, keeping yourself well for longer; it definitely staves it [frailty] off’ (023-GP Partner, 6–10 years of experience).

Frailty as a long-term condition

The majority of clinicians were broadly supportive of more formalised assessments and regular reviews for older adults living with frailty, similar to chronic disease management of hypertension or diabetes in primary care. There was particular enthusiasm amongst less experienced clinicians and those familiar with delivering structured medical reviews: ‘I think that’s a brilliant idea. A hundred percent’ (019-Clinical Pharmacist, 1–2 years of experience). Perceived benefits included better holistic care for patients living with frailty, as well as identifying decline quicker and avoiding hospital admissions. Clinicians also felt this model was justified given ‘there’s long term condition reviews for every other condition, you know, so why shouldn’t it be for this as well?’ (024-PA, 1–2 years of experience). They acknowledged, though, it would need financial incentives, e.g. ‘a QOF drive for it’ (015-Pharmacist, 1–2 years of experience) and training of staff. Many clinicians felt that there was the skill mix within PCNs to deliver such reviews.

However, there were concerns that routine screening would open ‘Pandora’s Box... [on an] already a strained NHS service’ (027-PA, 1–2 years of experience). Senior GPs also expressed wider concerns that routine frailty identification linked to QOF would become a ‘tick box exercise’ (001-GP Partner, 16–20 years of experience), which was ‘formulaic and forces a contact when it’s out of synch with your working pattern with the patient’s life’ (023-GP Partner, 6–10 years of experience).

Challenging conversations

A final consideration was how increased recognition would change conversations with patients about frailty. At present, many clinicians found these challenging and time consuming. Frailty, as a term, was often avoided in consultations because of perceived differences in patient understanding. ‘So, sometimes if you use the term frailty there’s almost the idea that it’s a downward decline; they can’t do anything. And I wonder how much of that is a natural decline over a mentality thing, and I think it sometimes prevents them from being able to do more for themselves’ (026-PA, 1–2 years of experience).

Consequentially, clinicians discussed choosing the right moment for conversations about frailty, often in the context of acute illness or terminal decline. Alternatively, language used focused on specific problems or future risks, but circumvented the frailty diagnosis. Widening the scope of frailty recognition would necessitate more communication with patients which could increase workload.

‘If they can see on the NHS app that they’ve been coded as having frailty would that offend them if that’s not been discussed with them directly? Are we then creating workload to have conversations with people to say we’ve identified them as frail before then coding them as frail?’ (031-PA, 6–10 years of experience).

Discussion

Summary

Conceptions of frailty in primary care differed. These varied with world-view, experience and job role of the clinician. Many experienced clinicians did not view frailty as a formal diagnosis, so were subsequently reluctant to problem code in medical notes. In contrast, less experienced clinicians had a more flexible construct of frailty and were open to different interpretations such as a recognising it as a long-term condition. There was good appetite for more training, especially as many clinicians had received no formal frailty education.

Frailty identification was most often by opportunistic pattern recognition of phenotypic characteristics such as weight loss. Visual assessment and continuity of care were both integral to this. Thus, clinicians felt strongly that the current workloads, fracturing of care and shift to remote consulting within general practice was threatening the traditional mechanisms of frailty recognition. Formalised frailty assessments were used by a minority of clinicians and appeared to overcome some of these challenges. However, these were time intensive and identifying patients who would benefit most was problematic. Whilst there was general support for wider recognition of frailty, there were concerns that, without specific funding allocation, this would have unmanageable resource implications.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study to explore perspectives on identifying frailty from a wide range of clinicians working in modern day general practice. It also accounts for changes in frailty recognition because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Qualitative methods have allowed in-depth exploration of this topic.

Participation was limited to English primary care, and results may be less transferable to other regions. However, participants worked within a broad range of primary care models. Participants may have had a greater interest in frailty, in responding to the advertisement, although only a minority declared a specialist interest or expertise. Fourteen of our participants only had 1–2 years as a primary care practitioner; however, this reflects the recent workforce expansion. Most of these roles did not exist before creation of PCNs in July 2019. Many of these clinicians had worked in other community healthcare settings prior to joining general practice, and so could draw on wider experiences of frailty.

We limited this study to those autonomously consulting in general practice who recognise, diagnose and code conditions in patient notes. However, other professionals in primary care may have different methods of identification or have non-medical perspectives, e.g. care-coordinators and social prescribers. It was outside the scope of the study to interview other clinicians working in the community, e.g. district nurses and allied health professionals. These individuals play an important role in frailty recognition given they frequently deliver care to patients at home.

Comparison to existing literature

Two qualitative studies, conducted in different regions of England, soon after NHS policy change, found that whilst GPs were broadly accepting of frailty recognition, there were concerns as to feasibility without specific funding [23, 31]. Our results, 4 years on and within the context of COVID-19 pandemic demonstrate that nationally there is significant variation in implementation of routine frailty identification. This is primarily influenced by local demographics and funding availability.

There is considerable ambiguity as to the best method of identifying frailty in primary care. The most common patient attributes described by clinicians in our study map closely onto domains of the Frailty Phenotype Model, where three or more of weight loss, self-reported exhaustion, low energy expenditure, slow gait speed and weak grip strength constitute frailty [32]. Intuitive pattern recognition of a frailty phenotype by primary care physicians has been demonstrated in other studies [17], and yet a phenotype model fails to either quantify risk or provide a framework to address patient-centred problems [33]. There is growing evidence of uncertainty of the application and accuracy of the eFI amongst primary care clinicians [23, 31]. Our research captures how it has been integrated into routine care, with some important differences in use and interpretation between more and less experienced clinicians [34, 35].

Continuity of care is one of the strongest traditional pillars of general practice, associated with increased life expectancy [34] and quality of care [35]. Recent research suggests that there has been a steady decline in continuity of care over the last decade [36]. Reduced continuity of care in older adults is associated with increased emergency department utilisation and inappropriate hospital admissions [37, 38]. Our findings highlight the importance of continuity of care in identifying those living with frailty, which may in part explain these relationships.

Implications for research and practice

In this study, we found limited evidence of buy-in to current NHS policy. For most primary care clinicians, ‘frail’ remains an adjective, loosely applied, most often to those matching a stereotypical phenotype. To advance concept and practice, clinicians need resources and an evidence base that wider recognition will benefit patients.

The recent diversification of workforce could enable delivery of multidisciplinary holistic assessments within primary care, akin to a Complete Geriatric Assessment [39]. The feasibility of such an approach would not only require dedicated resources but also tackle the training gap within primary care. At present, most professionals receive little or no formal education on frailty. Addressing this requires multi-stakeholder engagement with an emphasis on building capacity across the range of professionals now providing front-line care. Within new models of primary care delivery, relational care is essential to spot opportunities for intervention and markers of further decline. This does not need to be limited to GPs, other healthcare professionals, within the PCN could also provide this role [40].

Arguably, it will be difficult to unify conceptualisation of frailty, without a singular operational definition [41]. Ideally, there should be a simplified process from screening to diagnosis, integrated with electronic health records. Research is currently ongoing to improve accuracy of eFI and understand trajectories and risk profiles better in primary care [42]. Wider education for clinicians as to how the eFI is generated and when to use it could also improve its practical application. Ultimately instruments must be studied at an individual, not population, level to provide good construct validity. At present, there are a large number of studies of primary health care records, which equate the presence of frailty to eFI calculations [43–45]. Researchers should note that this rarely reflects primary care clinicians’ definition of frailty and true prevalence may differ.

Future research priorities should address how proactive frailty identification in primary care benefits patients. Greater understanding of risk stratification could help guide interventions from physical activity through to optimisation of medications. However, research must also focus on patient values and experiences, particularly surrounding conversations with primary care clinicians about living with frailty.

Conclusion

This in-depth exploration of frailty with broad range of primary care clinicians across England has highlighted heterogeneity in conceptualisation and inconsistency of identification. Improvements in education, evidence base and resource allocation may encourage wider recognition.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Anna Seeley, Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Margaret Glogowska, Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Gail Hayward, Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Declaration of Conflicts of Interest

None.

Declaration of Sources of Funding

This research was funded by Royal College of General Practitioners Scientific Foundation Board and Oxfordshire Health Services Research Committee. A.S. is funded by the NIHR Academic Clinical Fellowship, Award number ACF-2019-13-009. G.H. is funded by the NIHR Community Healthcare MedTech and In Vitro Diagnostics Co-operative at Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust.

Role of the Funder(s)

The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Data Availability Statement

Participants optionally consented to granting access to other researchers to anonymised interview data. For access to this data please contact the lead author.

References

- 1. Office for National Statistics . Population and Household Estimates. vol. 2021. England and Wales: Census, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rodríguez-Mañas L, Féart C, Mann G et al. Searching for an operational definition of frailty: a Delphi method based consensus statement. The frailty operative definition-consensus conference project. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci 2013; 68: 62–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cheng M-H, Chang S-F. Frailty as a risk factor for falls among community dwelling people: evidence from a meta-analysis. J Nurs Scholarsh 2017; 49: 529–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eeles EMP, White SV, O’mahony SM et al. The impact of frailty and delirium on mortality in older inpatients. Age Ageing 2012; 41: 412–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Campbell AJ, Buchner DM. Unstable Disability and the Fluctuations of Frailty. Age and Ageing 1997; 315–318. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6. Rockwood K, Howlett SE, Macknight C et al. Prevalence, attributes, and outcomes of fitness and frailty in community-dwelling older adults: report from the Canadian study of health and aging. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci 2004; 59: 1310–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ensrud KE, Ewing SK, Taylor BC et al. Comparison of 2 frailty indexes for prediction of falls, disability, fractures, and death in older women. Arch Intern Med 2008; 168: 382–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S et al. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 2013; 381: 752–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lloyd A, Kendall M, Starr JM, Murray SA. Physical, social, psychological and existential trajectories of loss and adaptation towards the end of life for older people living with frailty: a serial interview study. BMC Geriatr 2016; 16: 176. 10.1186/s12877-016-0350-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Age UK. Briefing: Health and Care of Older People in England 2019. London: Age UK. 2019.

- 11. Gordon EH, Hubbard RE. Frailty: understanding the difference between age and ageing. Age Ageing 2022; 51: 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mudge AM, Hubbard RE. Frailty: mind the gap. Age Ageing 2018; 47: 508–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nicholson C, Gordon AL, Tinker A. Changing the way “we” view and talk about frailty. Age Ageing 2017; 46: 349–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. BritainThinks . Frailty: language and perceptions. Age UK Br Geriatric Soc. 2015; 1–28. London: Age UK. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mackintosh W. Life & times: frailty as illness and the cultural landscape. Br J Gen Pract 2017; 67: 216–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lacas A, Rockwood K. Frailty in primary care: a review of its conceptualization and implications for practice. BMC Med 2012; 10: 4. 10.1186/1741-7015-10-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ambagtsheer RC, Archibald M, Lawless M, Mills D, Yu S, Bielby J. General practitioners’ perceptions, attitudes and experiences of frailty and frailty screening. Aust J Gen Pract 2019; 48: 426–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Korenvain C, Famiyeh IM, Dunn S, Whitehead CR, Rochon PA, McCarthy LM. Identifying frailty in primary care: a qualitative description of family physicians’ gestalt impressions of their older adult patients. BMC Fam Pract 2018; 19: 61. 10.1186/s12875-018-0743-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. NHS . NHS Long Term Plan. NHS England: NHS England, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Clegg A, Bates C, Young J et al. Development and validation of an electronic frailty index using routine primary care electronic health record data. Age Ageing 2016; 45: 353–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hollinghurst J, Fry R, Akbari A et al. External validation of the electronic frailty index using the population of Wales within the secure anonymised information linkage databank. Age Ageing 2019; 48: 922–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lansbury LN, Roberts HC, Clift E, Herklots A, Robinson N, Sayer AA. Use of the electronic frailty index to identify vulnerable patients: a pilot study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2017; 67: e751–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mulla E, Orton E, Kendrick D. Is proactive frailty identification a good idea? A qualitative interview study. Br J Gen Pract 2021; 71: e604–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. The Health Foundation . REAL Centre Projections: General Practice Workforce in England. London: The Health Foundation. 2022.

- 25. Joy M, McGagh D, Jones N et al. Reorganisation of primary care for older adults during COVID-19: a cross-sectional database study in the UK. Br J Gen Pract 2020; 70: e540–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Greenhalgh T, Rosen R. Remote by default general practice: must we, should we, dare we? Br J Gen Pract 2021; 71: 149–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. https://www.england.nhs.uk/gp/case-studies/wokingham-primary-care-networks-the-5-is/ (19 August 2022, date last accessed).

- 28. Laura BB, Ree’ L, Bhatt T et al. Integrating Additional Roles into Primary Care Networks. London: The Kings Fund. 2022.

- 29. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006; 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Silverman D. Doing Qualitative Research: A Practical Handbook. SAGE Publications Ltd., 5th edition, 592 pages, 2017.

- 31. Alharbi K, van Marwijk H, Reeves D, Blakeman T. Identification and management of frailty in English primary care: a qualitative study of national policy. BJGP Open 2020; 62: e233–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol Ser A: Biol Sci Med Sci 2001; 56: 146–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cesari M, Gambassi G, van Kan GA et al. The frailty phenotype and the frailty index: different instruments for different purposes. Age Ageing 2014; 43: 10–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sandvik H, Hetlevik Ø, Blinkenberg J, Hunskaar S. Continuity in general practice as a predictor of mortality, acute hospitalization, and use of out-of-hours services: registry-based observational study in Norway. Br J Gen Pract 2022; 72: e84–90. 10.3399/BJGP.2021.0340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Saultz JW, Albedaiwi W. Interpersonal continuity of care and patient satisfaction: a critical review. Ann Fam Med 2004; 2: 445–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tammes P, Morris RW, Murphy M, Salisbury C. Is continuity of primary care declining in England? Br J Gen Pract 2021; 71: e432–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Godard-Sebillotte C, Strumpf E, Sourial N, Rochette L, Pelletier E, Vedel I. Primary care continuity and potentially avoidable hospitalization in persons with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2021; 69: 1208–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tammes P, Purdy S, Salisbury C, MacKichan F, Lasserson D, Morris RW. Continuity of primary care and emergency hospital admissions among older patients in England. The Annals of Family Medicine 2017; 15: 515–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. British Geriatric Society . Fit for Frailty - Consensus Best Practice Guidance for the Care of Older People Living in Community and Outpatient Settings. London: British Geriatrics Society. 2014.

- 40. MacInnes J, Baldwin J, Billings J. The Over 75 Service: continuity of integrated care for older people in a United Kingdom primary care setting. International Journal of Integrated Care 2020; 20: 2, 1–9. 10.5334/ijic.5457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rodriguez-Mañas L, Fried LP. Frailty in the clinical scenario. Lancet 2015; 385: e7–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fogg C, Fraser SDS, Roderick P et al. Determinants of acquired disability and recovery from disability in Indian older adults: longitudinal influence of socio-economic and health-related factors. BMC Geriatr 2021; 22: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wilkinson C, Clegg A, Todd O et al. Atrial fibrillation and oral anticoagulation in older people with frailty: a nationwide primary care electronic health records cohort study. Age Ageing 2021; 50: 772–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pradhananga S, Regmi K, Razzaq N, Ettefaghian A, Dey AB, Hewson D. Ethnic differences in the prevalence of frailty in the United Kingdom assessed using the electronic frailty index. Aging Med 2019; 2: 168–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Boyd PJ, Nevard M, Ford JA, Khondoker M, Cross JL, Fox C. The electronic frailty index as an indicator of community healthcare service utilisation in the older population. Age Ageing 2019; 48: 273–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Participants optionally consented to granting access to other researchers to anonymised interview data. For access to this data please contact the lead author.